Abstract

Lysophosphatidic acids (LPA) exert growth factor-like effects through specific G protein-coupled receptors. The presence of different LPA receptors often determines the specific signaling mechanisms and the physiological consequences of LPA in different environments. Among the four members of the LPA receptor family, LPA2 has been shown to be overexpressed in colon cancer suggesting that the signaling by LPA2 may potentiate growth and survival of tumor cells. In this study, we examined the effect of LPA on survival of colon cancer cells using Caco-2 cells as a cell model system. LPA rescued Caco-2 cells from apoptosis elicited by the chemotherapeutic drug, etoposide. This protection was accompanied by abrogation of etoposide-induced stimulation of caspase activity via a mechanism dependent on Erk and PI3K. In contrast, perturbation of cellular signaling mediated by the LPA2 receptor by knockdown of a scaffold protein NHERF2 abrogated the protective effect of LPA. Etoposide decreased the expression of Bcl-2, which was reversed by LPA. Etoposide decreased the phosphorylation level of the proapoptotic protein Bad in an Erk-dependent manner, without changing Bad expression. We further show that LPA treatment resulted in delayed activation of Erk. These results indicate that LPA protects Caco-2 cells from apoptotic insult by a mechanism involving Erk, Bad, and Bcl-2.

Keywords: lysophosphatidic acids, MAPK, receptor, apoptosis

1. INTRODUCTION

In normal adult colon, enterocytes generated from stem cells located at the base of the crypt migrate towards the luminal surface. During this process, enterocytes located at the tip of small intestine villi or at the luminal surface of the colon are thought to undergo apoptosis. Apoptosis is counterbalanced by the proliferation and differentiation of progenitor cells derived from stem cells. Deregulation of apoptosis and cell division can result in hyperplasia and tumorigenesis of the intestine and colon. For example, expression of Bcl-2, an anti-apoptotic protein, is elevated the majority of dysplastic, adenomatous lesions [1]. Overexpression of Bcl-2 in human melanoma cells promotes a migratory and invasive phenotype, contributing to tumor progression [2].

Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) is a bioactive glycerophospholipid that is generated and released by platelets, macrophages, epithelial cells, and some tumor cells [3-5]. LPA binds to specific G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) on the cell surface to exert diverse growth factor-like effects, such as proliferation, apoptosis, contraction, and migration [6-8]. Thus far, four distinct membrane receptors that bind LPA have been identified, LPA1, LPA2, LPA3, and LPA4/GPR23 [9-12]. All the LPA receptors can couple to three families of heterotrimeric GTP binding proteins, including Gq/11, Gi/o, and G12/13 [6-8]. G proteins, in turn, activate a number of signaling cascades, including the activation of phospholipase C (PLC) with subsequent phosphatidylinositol-(4,5)-biphosphate hydrolysis, the activation of the phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K)-Akt and the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways, and the small GTPase RhoA that mediates the remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton [6-8].

The effect of LPA in cellular proliferation and survival has been studied extensively, and is partly attributed to the capacity of LPA to regulate apoptosis. However, the effect of LPA on cell survival and apoptosis varies among different cell types. LPA mediates survival of ovarian cancer cells, macrophages, fibroblasts, and neonatal cardiac myocytes, while promoting apoptosis in hippocampal neurons and PC12 cells [7, 13]. The varied effects of LPA on apoptosis are dependent on the presence of specific LPA receptors, but also on the cellular context. For example, activation of LPA1 prevented apoptosis in primary lymphocytic leukemia cells, whereas the same LPA1 induced apoptosis and anoikis in ovarian cancer cells [14, 15]. In untransformed rat intestinal epithelial IEC-6 cells, both LPA1 and LPA2 are thought to be responsible for the anti-apoptotic effect of LPA [16], but the effect in colon cancer cells is not known.

Studies have shown the presence of high levels of LPA in the ascitic fluid of patients with ovarian cancer as well as increased expression of LPA2 in several types of cancers, including ovarian, colorectal, and thyroid cancer. [17-21]. These studies, in conjunction with multiple effects mediated by LPA, suggest that over-expression of LPA2 may enhance the development of cancer. Recent studies have identified scaffold proteins that play pivotal roles in signaling elicited by LPA2 through their interaction with the carboxyl terminus of LPA2. These scaffold proteins include TRIP6 and at least three PDZ (PSD-95/DlgA/ZO-1) -containing proteins, Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor 2 (NHERF2), PDZ-RhoGEF, and leukemia-associated RhoGEF [21-25]. We have shown previously that knockdown of NHERF2 in Caco-2 human colon cancer cells significantly attenuated the ability of LPA2 to induce activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase-1/2 (Erk), Akt, and interleukin-8 (IL-8) [21]. The consequence of the NHERF2 knockdown was similar to knockdown of LPA2 as LPA2 is the major LPA receptor expressed in human colon cancer cells such as Caco-2 cells.

In the present study, we show that LPA protects the human colon cancer Caco-2 cells from apoptosis induced by the chemotherapeutic drug etoposide. LPA promotes survival of Caco-2 cells via a NHERF2-dependent mechanism that results in activation of Erk and inactivation of pro-apoptotic Bad and caspase 3.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Cell culture and treatment

Caco-2 cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 100 U/ml penicillin at 37°C in 95% air/ 5% CO2 atmosphere. Stable knockdown of NHERF2 in Caco-2 cells using small hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeted against NHERF2 has previously been described [21]. Caco-2 cells with stable knockdown of NHERF2 (Caco-2/CL4) and control transfected cells (Caco-2/pSiL) were grown in the above media supplemented with 300 unit/ml hygromycin. 1-Oleoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidic acid was obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids and prepared in PBS containing 0.1% fatty acid-free BSA. Cells were serum-starved for 24 h prior to treatment with LPA. In some cases, cells were pretreated for 15-30 min with 20 μM U0126, 50 μM LY294002, 5 μM U73122, 25 μM Zvad.fmk before exposure to LPA. As controls, cells were treated with the same volume of vehicle (DMSO) or PBS with 0.1% BSA. Etoposide (Sigma) was prepared in Me2SO. All the inhibitors were obtained from Calbiochem.

2.2. Annexin V staining

Cells seeded at a density of 1 × 105 per 60 mm culture plate were serum-starved for 24 h and treated with 200 μM etoposide, etoposide together with LPA, or carrier for 24 h. Cells resuspended in binding buffer (10mM HEPES/NaOH, ph.7.4, 140 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2) were stained with 5 μl of annexin-FITC and 5 μg/ml propidium iodide (PI). Viable, unstained cells in untreated samples were used as negative controls. Cells were then analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACSCalibur cytometer (BD Biosciences), and CellQuest (BD Biosciences) was used to calculate the amount of apoptotic cells.

2.3. Caspase-3/7 activity

Caspase-3 and caspase-7 activities were determined using Caspase-Glo 3/7 Assay kit (Promega). Briefly, cells in 96-well plates (5,000 cells/well) were serum-starved for 24 h and treated with etoposide with or without LPA for another 24 h. Caspase-Glo reagent (100 μl) was added to an equal amount of media in each well and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The luminescence of each sample was measured using a Luminoskan Ascent (Thermo Labsystems).

2.4. Western blot

Cells were lysed in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 0.1 mM PMSF, 10% glycerol, 2 mM Na orthovanadate, 10 mM Na fluoride, 20 mM Na pyrophosphate, 25 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1% Triton X-100, and protease inhibitors). The cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 14,000 g at 4°C for 10 min and protein concentration was determined by the Bicinchoninic Acid assay (Sigma). Equal amounts of lysate were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and Western blot was performed as previously described [21]. Anti-Bad, anti-phospho-Bad, anti-Erk, and anti-phospho-Erk antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Densitometric analysis was performed on the Typhoon phosphoimager (Amersham) using the Image Quant program. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA using Origin software. Data are presented as the means ± standard error (SE).

3. RESULTS

3.1. LPA protects Caco-2 cells from etoposide-induced apoptosis

Etoposide is a widely used clinical agent for cancer chemotherapy that targets topoisomerase II [26]. We initially tested different concentrations of etoposide in Caco-2 cells to determine an optimum concentration to induce apoptosis. Although a range of 75 to 500 μM etoposide resulted in an increase in the apoptotic population, 150-200 μM etoposide was needed for a consistent increase in apoptotic population within 24 h (data not shown) and all the studies reported in this work used 200 μM etoposide. Because previous studies have shown that cell survival and anoikis of intestinal enterocytes vary depending on the state of differentiation [27, 28], all our studies were performed with differentiated Caco-2 cells.

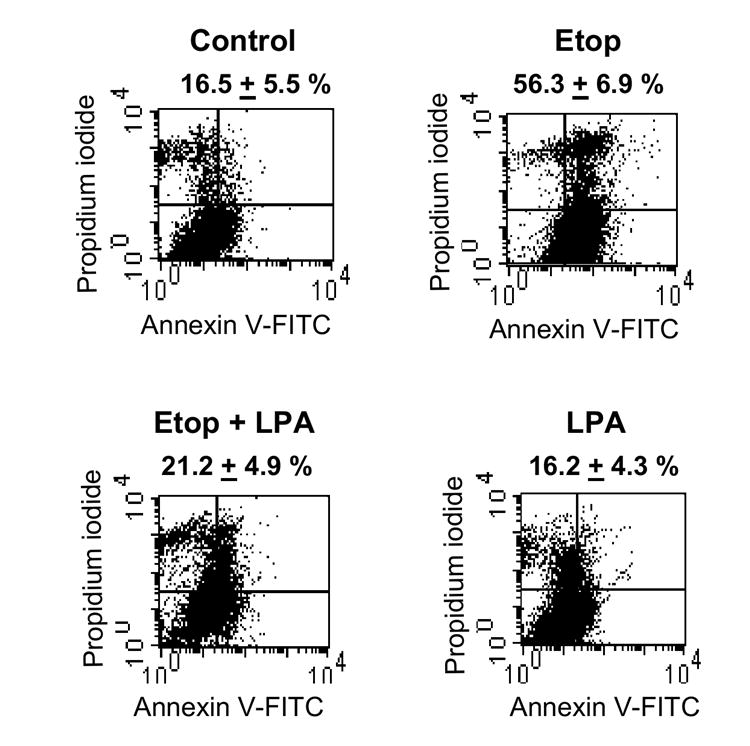

To determine whether LPA can protect colon cancer cells from apoptosis, serum-starved Caco-2 cells were treated with etoposide (200 μM) for 24 h in the presence or absence of LPA (20 μM). As controls, cells were treated with either an equal amount of Me2SO, solvent used prepare etoposide, or LPA alone. Apoptosis was determined by Annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) staining, and apoptotic cells were defined as Annexin-positive but PI-negative (Figure 1). Following 24 h serum-starvation, 16.5 ± 5.5 % of cells were apoptotic. LPA alone did not have a significant effect (16.2 ± 4.2 %). Exposure to etoposide increased the apoptotic population to 56.3 ± 6.9 %, more than a three-fold increase compared to the control. Etoposide-induced apoptosis was blocked by addition of LPA (etoposide/LPA) in which the apoptotic cell level was decreased to 21.2 ± 4.9 %. These results suggested that LPA effectively protected Caco-2 cells from etoposide-induced apoptotic death.

Figure 1. LPA inhibits etoposide-induced apoptosis in Caco-2 cells.

Caco-2 cells were serum-starved overnight and treated for 24 h with vehicle (Control), 200 μM etoposide (Etop), 200 μM etoposide + 20 μM LPA, or 20 μM LPA. Cells were harvested, stained with Annexin V and PI, and analyzed by FACS analysis. The Annexin V-positive and PI-negative population was defined as cells undergoing apoptosis. Representative results from three separate sets of experiments are shown.

3.2. Protection of Caco-2 from etoposide-induced apoptosis is dependent on the presence of NHERF2

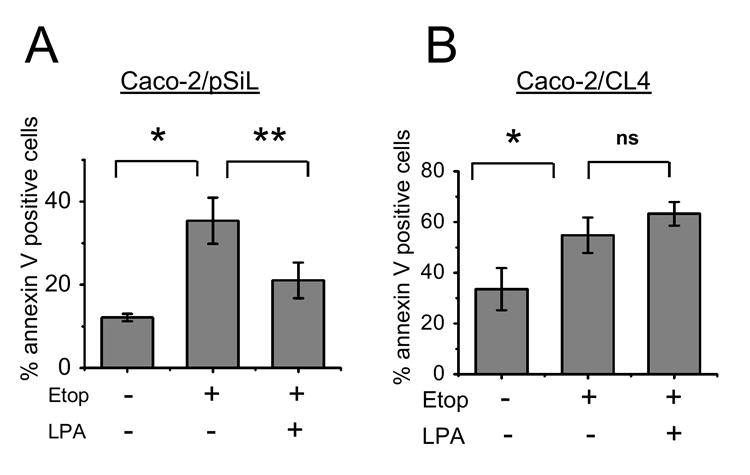

We have shown previously that Caco-2 cells predominantly express LPA2 with the expression level of LPA1 at a significantly lower level and no expression of LPA3, making LPA2 only a significant LPA receptor in these cells [21]. LPA2 has carboxyl-terminal motifs that allow interaction with a PDZ (PSD-95/DlgA/ZO-1) domain of the Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor 2 (NHERF2), which functions as a scaffold to link signaling proteins, such as PKA and PKCα, to GPCRs and transporters at the cell surface [21, 23, 29-31]. NHERF2 links LPA2 to PLC-β3 and hence affects the activation of downstream targets, such as Erk and cyclooxygenase-2 [23]. We have previously shown that knockdown of NHERF2 expression in Caco-2 cells by RNA interference drastically down-regulates the LPA2-Gαi-Akt pathway and induction of IL-8 [21]. Moreover, over-expression of NHERF2 reconstitutes the signaling mediated by LPA2 [23]. Collectively these data demonstrate that displacement of the LPA2-NHERF2 interaction severely perturbs the cellular signaling mediated by LPA2. Therefore, to determine whether the perturbation of LPA2-mediated signaling compromises the LPA-induced anti-apoptotic responses, we examined the effects of etoposide and LPA in Caco-2 cells with stable knockdown of NHERF2 (Caco-2/CL4) and control transfected Caco-2 cells (Caco-2/pSiL) [21]. These cells were treated with etoposide, carrier, or LPA for 24 h and apoptosis was determined by Annexin V labeling. In both Caco-2/pSiL and Caco-2/CL4 cells, etoposide doubled the number of cells undergoing apoptosis compared with untreated serum-starved control cells (Figure 2). However, in contrast to Caco-2/pSiL (Figure 2A), LPA did not protect Caco-2/CL4 from etoposide-induced apoptotic death (Figure 2B). These results demonstrated that the LPA-induced survival effect on Caco-2 cells was dependent on the presence of NHERF2 and intact LPA2 signaling.

Figure 2. LPA does not suppress apoptosis in Caco-2/CL4 cells.

(A) Caco-2/pSiL and (B) Caco-2/CL4 cells were treated for 24 h with etoposide or etoposide + LPA. Cells were stained with Annexin V only and analyzed by FACS. n=3. *, P<0.01 compared with control treated cells, ** P<0.01 compared with etoposide treated cells. ns, not significant.

3.3. LPA inactivates caspase-3/7

We estimated that a minimum of 12 h is needed to induce apoptotic death of Caco-2 cells by etoposide. This is based on histogram analysis to determine the subG1 cell population (apoptotic) following exposure to etoposide for varying times [32]. An increase in the subG1 population was observed after 12 h of treatment (data not shown).

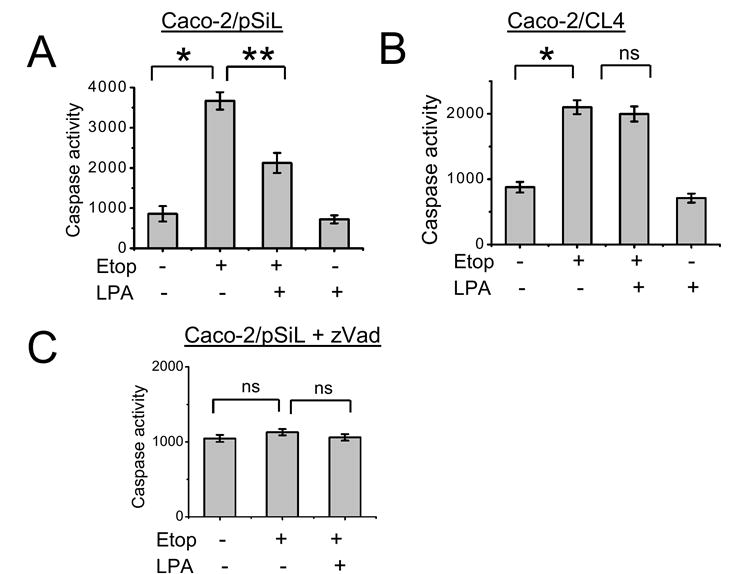

Caspases are downstream effectors common to many paradigms of apoptosis [33]. To determine the effect of LPA on caspase activation, Caco-2/pSiL cells were treated with etoposide for 24 h in the presence or absence of 20 μM LPA. Etoposide induced a three-fold increase in caspase-3/7 activity (Figure 3A). Co-incubation with LPA reduced etoposide-induced caspase-3/7 activation by approximately 50%, demonstrating a direct effect on caspases by LPA treatment. In contrast, LPA alone did not significantly alter caspase activity. As shown in Figure 3B, etoposide induced apoptosis of Caco-2/CL4 cells, but co-treatment with LPA did not attenuate caspase activity in these cells, affirming the importance of LPA2 and NHERF2 in protection of the cells from the apoptotic insult. In Figure 3C, Caco-2 cells were treated with the general caspase inhibitor, Zvad.fmk [34]. As expected, there was no change in the caspase activity was incurred by etoposide or LPA under this condition. These data collectively confirm that the induction of caspase-3/7 activity is an essential step in etoposide-induced apoptosis and that LPA rescues cells by inhibition of caspases.

Figure 3. LPA inhibits etoposide-induced caspase activity.

(A) Caco-2/pSiL and (B) Caco-2/CL4 were treated with etoposide or etoposide + LPA. Caspase-3/7 activity was determined by using the Caspase Glo 3/7 assay as described in Materials and Methods. n=3. *, P<0.01 compared with control cells, **, P<0.01 compared with etoposide treated cells. ns, not significant. (C) Caco-2 cells were preincubated with Zvad.fmk before being treated as above. Caspase-3/7 activity was determined as described above. n=3.

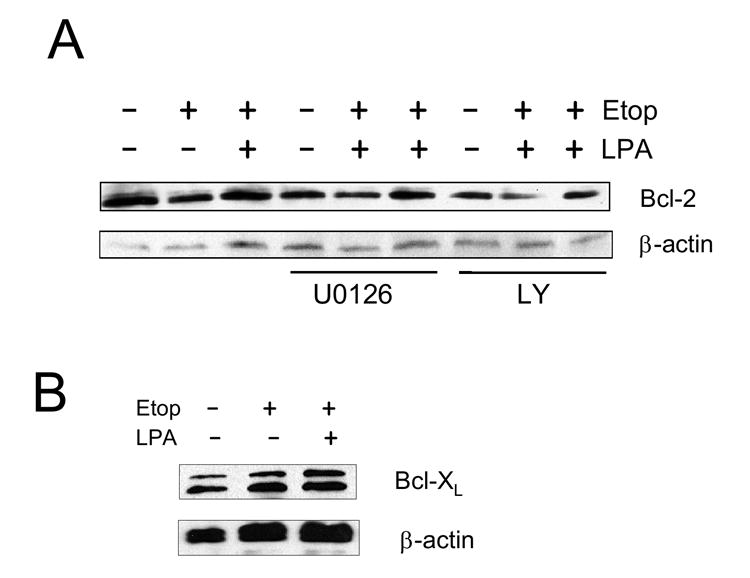

3.4. LPA-induced signaling leads to Bad phosphorylation

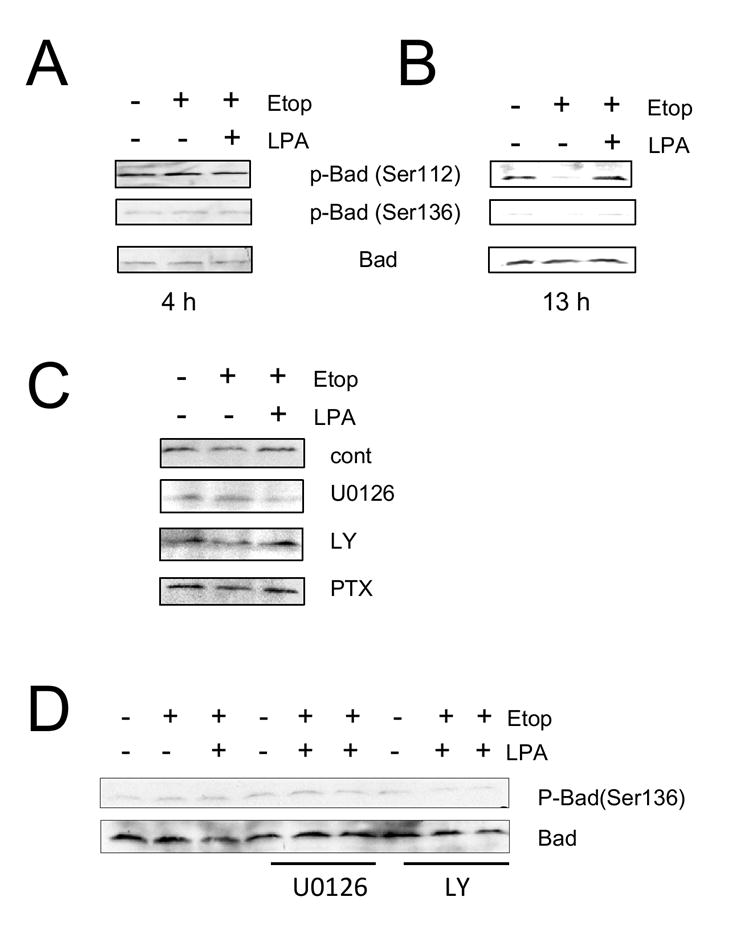

Caspase-3 and -7 can be activated by either activation of cell surface receptors or changes in mitochondrial integrity [33]. The mitochondrial-mediated caspase activation is highly regulated by members of the Bcl-2 family. The Bcl-2 family consists of pro-survival proteins (Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and Bcl-w) and pro-apoptotic proteins (Bax, Bad, and Bim) [35]. To determine whether etoposide and LPA affect the Bcl-2 family of proteins, we examined expression levels of Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL. Etoposide treatment for 13 h resulted in a small decrease in the expression level of Bcl-2 (Figure 4A), whereas no change in Bcl-XL was observed (Figure 4B). Similarly, we observed no change in Bax expression (data not shown). The change in Bcl-2 protein expression by etoposide was partially blocked in the presence of the MEK inhibitor, U0126, but not in the presence of the PI3K inhibitor, LY294002 (Figure 4A). However, the basal expression levels of Bcl-2 in the presence of either inhibitor was slightly lower compared with in the absence of the inhibitors. Bad, a very distant Bcl-2 family member, promotes apoptosis by binding to either Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL and displacing them from apoptotic Bax [36]. Phosphorylation of Bad on either Ser-112 or Ser-136 is thought to promote cell survival [37-40]. Phosphorylation at either of these residues promotes interaction with the 14-3-3 protein instead of Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL, resulting in the liberation of the anti-apoptotic protein and consequent promotion of cell survival [37, 40]. Akt phosphorylates Bad at Ser-112, whereas Ser-136 is reported to be phosphorylated by MAPKs [38, 39, 41]. To determine whether phosphorylation of Bad is involved in LPA-mediated cell survival, we treated cells with etoposide, etoposide/LPA or carrier for 4h, but there was no significant changes in either phosphorylation or expression levels of Bad (Figure 5A). However, as shown in Figure 5B, a change in Bad phosphorylation was observed at 13 h in the presence of etoposide, at which time there was a significant increase in the subG1 population. Etoposide decreased phospho-Bad at Ser-112, as determined by Western blot using an antibody specific for detecting phosphorylation at Ser-112 of Bad. Co-incubation with LPA restored phosphorylation at Ser-112 to a level similar to the control. In comparison, the effect of etoposide or etoposide/LPA on phosphorylation at Ser-136 of Bad was not significant. To confirm the role of MAPK pathway in phosphorylation of Bad, phosphorylation on Ser-112 of Bad was determined in the presence of the mitogen-activated kinase kinase 1 (MEK1) inhibitor U0126 (20 μM), the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 (50 μM), or pertussis toxin (50 ng/ml), which uncouples Gαi. As shown in Figure 5C, U0126 abrogated the increase in phosphorylation at Ser-112 by etoposide + LPA compared with etoposide alone. On the other hand, LY290042 or PTX showed no effect on phosphorylation at Ser-112. The lack of an effect on phosphorylation at Ser-112 by PTX is consistent with a previous report that LPA-mediated activation of Erk in Caco-2 cells is not PTX-sensitive [21]. In contrast to the changes in the phosphorylation at Ser-112, the phosphorylation level at Ser-136 was not changed even after 24h treatment in the absence or presence of inhibitors (Figure 5D).

Figure 4. LPA modulates the expression level of Bcl-2.

(A) Caco-2 cells were etoposide or etoposide + LPA for 13h in the absence or presence of U0126 or LY294002. The expression level of Bcl-2 was determined using an anti-Bcl-2 antibody. n=3. (B) The expression levels of Bcl-XL are shown. n=3.

Figure 5. LPA inactivates pro-apoptotic Bad.

Caco-2 cells were treated with etoposide or etoposide + LPA for 4 h (A) or 13 h (B). Phosphorylation of Bad was determined using anti-phospho-Bad antibodies that specifically recognize Bad phosphorylation at either Ser-112 or Ser-136. The amounts of total Bad were determined using an anti-Bad antibody. n=3. (C) Phosphrylation of Bad at Ser-112 was determined in the presence of U0126, LY294002, and PTX. Phosphorylation at Ser-112 of Bad was determined. n=3. (D) Phosphorylation of Bad at Ser-136 were determined in Caco-2 cells treated with etoposide or etoposide + LPA for 24 h. n=3.

3.5. The MAPK pathway mediates LPA protection against apoptosis

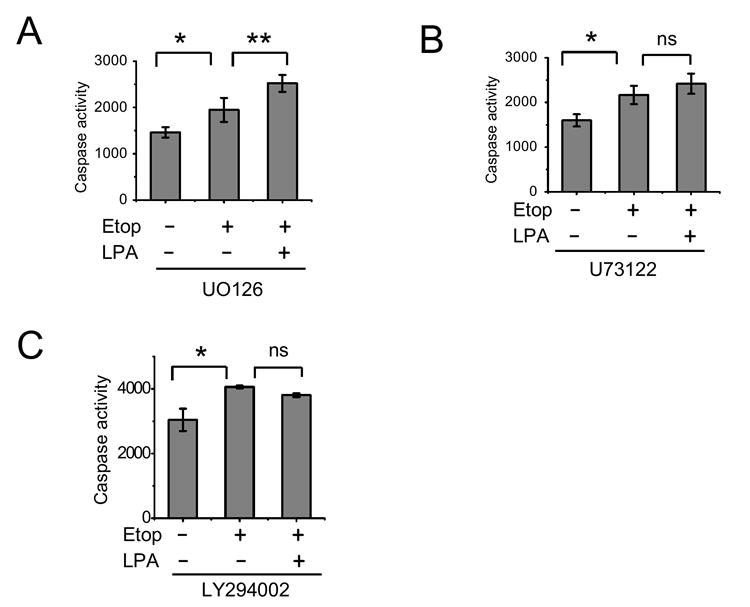

LPA stimulates both Erk and Akt in Caco-2 cells [21] and as shown above the phosphorylation of Bad indicates that the MAPK pathway plays a dominant role in the protection of Caco-2 cells. To confirm that activation of Erk is involved in the prosurvival signaling elicited by LPA, we determined the caspase activity in Caco-2/pSiL cells incubated with carrier, etoposide, or etoposide/LPA for 24 h in the presence of U0126 or LY294002 (Figure 6). The basal caspase activity was elevated following the pretreatment with either inhibitor compared to carrier-treated cells (Figure 3A), suggesting that the basal activities of these kinases are important for the viability of the cells. Because of the elevated basal caspase activity, the inclusion of the inhibitors diminished the magnitude of changes in caspase activity elicited by etoposide exposure. Despite the smaller effect on the caspase activity, LPA failed to prevent an increase in caspase activity in the presence of U0126 (Figure 5A). Our previous study has shown that LPA-induced Erk activation is dependent on phospholipase Cβ (PLCβ) since inhibition of PLCβ decreased activation of Erk [21]. Similarly to U0126, the PLCβ blocker, U73122, also abolished the effect of LPA (Figure 5B). Although we could not detect phosphorylation at Ser-136 of Bad, LY294002 almost completely abrogated the protective effect of LPA (Figure 5C). Interestingly, in cells treated with U0126 etoposide/LPA exposure resulted in an increase in the caspase activity compared with etoposide alone. U73122 also resulted in a small, although statistically insignificant, increase in the caspase activity with LPA/etoposide compared with etoposide alone. Figure 5D and E show that UO126 and LY294002, respectively, had no effect on the caspase activity in Caco-2/CL4 cells when compared with those in the absence of the inhibitors (Figure 3B).

Figure 6. LPA-mediated caspase 3/7 inactivation is dependent on Erk and Akt signaling in Caco-2/pSiL cells.

Caco-2/pSiL cells (A-C) and Caco-2/CL4 (D, E) were treated with etoposide or etoposide + LPA in the presence of 20 μM UO126 (A, D), 5 μM U73122 (B), or 50 μM LY294002 (C, E). Caspase-3/7 activity was determined as described earlier. n=3. *, P<0.05 compared with control cells. **, P<0.05 compared with etoposide treated cells. ns, not significant.

3.6. LPA dependent pro-survival signals are mediated through delayed activation of Erk in Caco-2 cells

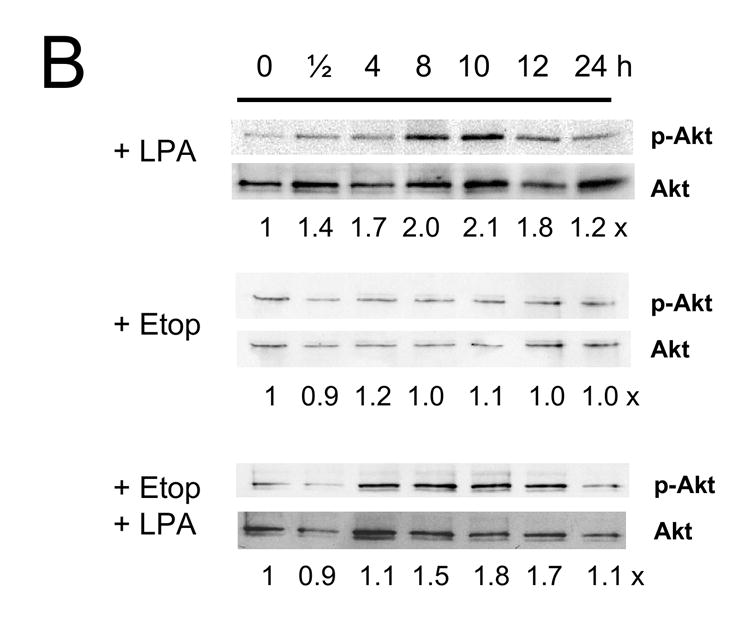

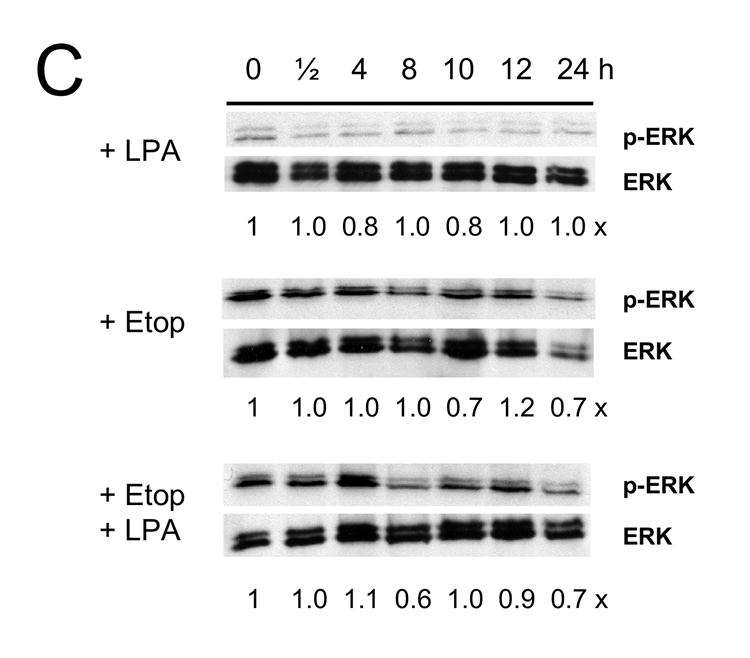

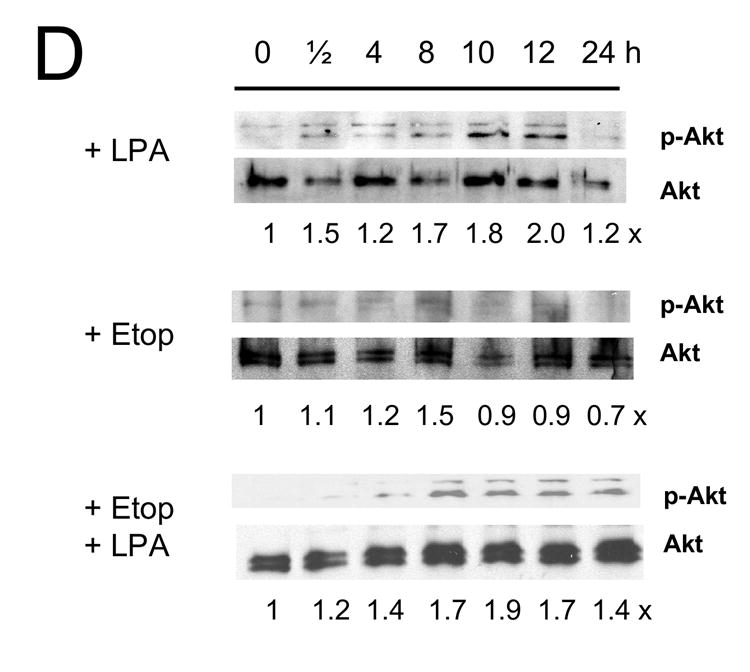

The phosphorylation of Bad induced by LPA suggests that the anti-apoptotic effect of LPA in Caco-2 cells is mediated by the activation of Erk and to a lesser extent Akt. To further examine the involvement of the MAPK and PI3K-Akt pathways, we next examined Erk and Akt activation in response to LPA by determining the phosphorylation levels by Western blot analysis.

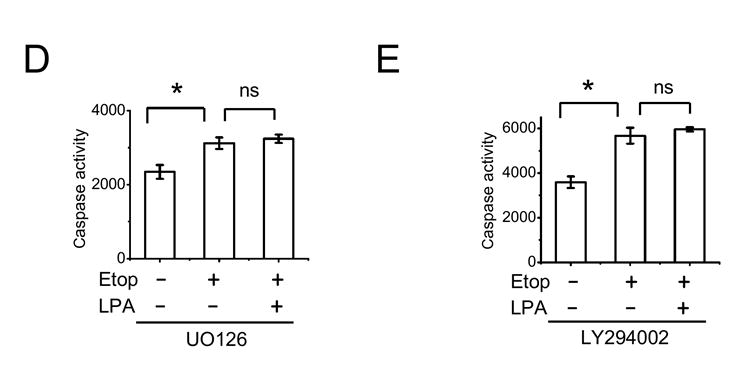

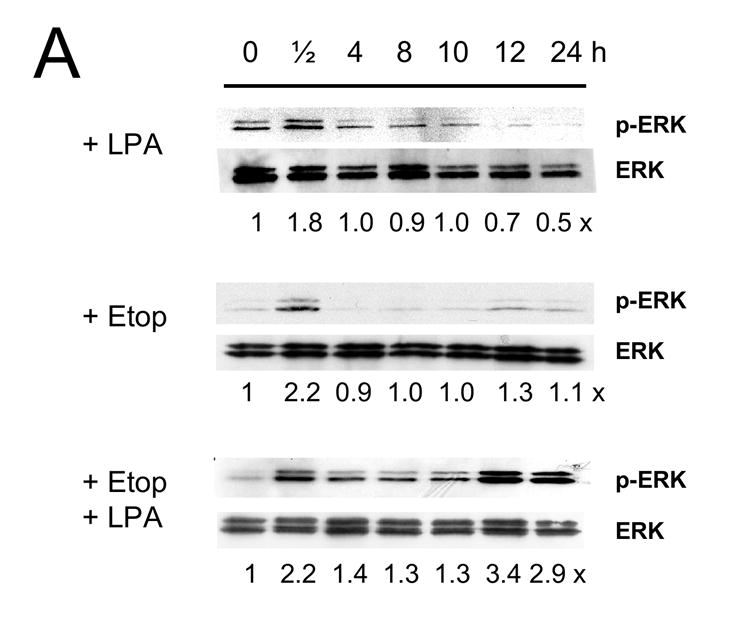

Figure 6A shows that LPA increased phosphorylation level of Erk in Caco-2 cells at 30 min, which decreased to the basal level at 4 h. Etoposide alone resulted in an increase in Erk phosphorylation level at 30 min. In addition, we occasionally observed a small increase in Erk phosphorylation at 12 h. In contrast, co-treatment of the cells with etoposide and LPA restored the acute phosphorylation of Erk. In addition, there was sustained phosphorylation of Erk, which reached the maximum level at 12 h. In contrast to the control cells, LPA treatment did not elicit phosphorylation of Erk in Caco-2/CL4 cells. Moreover, etoposide/LPA treatment of Caco-2/CL4 failed to induce delayed activation of Erk.

The kinetic of phosphorylation of Akt by LPA was relatively slower, exhibiting a small increase at 30 min that was sustained for the next 12 h (Figure 6B). Etoposide alone showed no effect on Akt and co-incubation with LPA restored the levels of Akt phosphorylation almost to the levels observed by LPA alone. LPA treatment also stimulated the phosphorylation levels of Akt in Caco-2/CL4 cells and the levels of phosphorylation were lower compared to control cells as previously shown [21]. The effects of LPA/etoposide in Caco-2/CL4 cells were again similar to those in the control cells.

4. DISCUSSION

Apoptosis is a normal physiological process critical for the development and function of multicellular organisms. Apoptosis seems to be one of the major safeguards against uncontrolled proliferation. Proliferation and apoptosis are intimately related. Many cancer cells are often hypersensitive to apoptosis induction, but can avoid apoptosis because they have lost or can bypass check points that control cell cycle progression [33, 42]. Over-expression of LPA2 has been associated with different types of cancers, including ovarian and colon cancers, suggesting that LPA may act to promote survival of cancerous cells even in the presence of chemotherapy [18-21, 43]. Herein, we show that LPA provides survival signals to Caco-2 cells, protecting cells from etoposide-induced apoptosis via a NHERF2-dependent mechanism. It has previously been shown that NHERF2 interacts with LPA2, but not other LPA receptors, and plays a pivotal role in regulation of cellular signaling elicited by LPA2 [21, 23]. Knockdown of NHERF2 in Caco-2 and HeLa cells drastically compromised LPA2-mediated signaling, such as activation of Akt, Erk, and PLCβ. Consistent with the earlier reports, we found that Caco-2/CL4 cells, with NHERF2 knocked down, were not protected by LPA from etoposide-induced apoptosis. Although we did not show that LPA2 is directly responsible for the anti-apoptotic effect, there is compelling evidence indicating that this effect is mediated by LPA2 [21, 23]. First, other known LPA receptors are expressed at much lower levels or absent in Caco-2 and other colon cancer cells including Caco-2, making LPA2 the only LPA receptor with a significant cellular function. Second, knockdown of NHERF2 or LPA2 similarly attenuated LPA-mediated induction of IL-8 in colon cancer cells. Third, LPA2 is the only LPA receptor that interacts with NHERF2.

The MAPK (JNK, p38 and Erk) pathways have been previously associated with apoptosis. The JNK and p38 kinase pathways are the classical pathways involved in apoptosis, whereas Erk is considered a pro-survival kinase in most cases [27, 28, 44-46]. However, recent studies have challenged this unilateral role of Erk in cell survival that activation of Erk can play an active role in inducing apoptosis and functions upstream of mitochondria signaling [44, 47, 48]. In addition, it has been shown recently that conversion of sustained Erk activation to transient abrogates the pro-apoptotic effect of estrogen [49]. On the other hand, the sustained and delayed Erk activation provides survival signals to human keratinocytes, suggesting a dual role of Erk on cell survival [50]. Treatment of Caco-2 cells with etoposide elevated caspase activity resulting in cell death, which was prevented by co-incubation with LPA (Figure 3A). As expected, the survival of Caco-2 cells was dependent on activation of Erk as the pharmacological inhibition of MEK1 completely abrogated the protective effect of LPA against etoposide-induced apoptosis (Figure 6A). On the other hand, etoposide alone resulted in acute phosphorylation of Erk at 30 min and occasionally weak and delayed Erk phosphorylation at 12-24 h (Figure 7A). Previous studies have shown that etoposide-induced apoptosis of fibroblasts and keratinocytes is associated with an increase in Erk phosphorylation [51, 52]. In fibroblasts, etoposide induced caspase activity, which was completely abrogated by inhibition of Erk activity [51, 52]. In keeping with these reports, apoptosis of hepatocytes by Clostridium difficile toxin is accompanied by acute stimulation of Erk [53]. We found that U0126 attenuated etoposide-induced caspase activity (Figure 6A) but still resulted in a significant increase compared with control-treated cells (Figure 3A). Taken together, activation of Erk by etoposide has a limited role in apoptosis of Caco-2 cells and does not appear to be the main mechanism underlying etoposide-induced apoptosis of Caco-2 cells. Subsequently, we show that co-incubation of Caco-2 cells with LPA restored acute phosphorylation of Erk and potentiated delayed phosphorylation of Erk. The specificity of these responses to LPA is supported by the lack of similar changes in Caco-2/CL4 cells in which LPA-induced signaling is perturbed by knockdown of NHERF2 [21]. Although the delayed phosphorylation of Erk by etoposide/LPA appears to mimic the effect by etoposide alone, the levels of Erk phosphorylation were substantially greater than those in the presence of etoposide alone. A previous study has shown that a gradual and sustained increase in phosphorylation of Erk by LPA rescued hepatocytes from C. difficile toxin-induced apoptosis [53]. In this report, in addition to the sustained phosphorylation of Erk, LPA resulted in phosphorylation of p90RSK, which lies upstream of Bad [53]. Erk represents an important converging point of diverse cellular processes that are regulated by precise spatio-temporal control mechanisms [27, 28, 44, 54]. Since there are a large number of Erk substrates and diverse biological processes that Erk regulates, the eventual outcome of Erk activation is determined by the dynamic compartmentalization and the spatial arrangement of Erk [54]. Hence, it is conceivable that despite the resemblance of Erk phosphorylation by etoposide and etoposide/LPA, the different levels of Erk phosphorylation may result in activation of different sets of target genes leading to cell death by etoposide, whereas etoposide/LPA promotes cell survival.

Figure 7. LPA mediated pro-survival effects are associated with prolonged Erk activation.

Caco-2/pSiL (A, B) and Caco-2/CL4 (C, D) cells were treated with LPA, etoposide, or both for different times. Treated cells were lysed and equal amounts of lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE. The amounts of phosphorylated-Erk (A, C) or phosphrylated-Akt (B, D) were determined using anti-phospho-Erk or Akt antibodies, respectively. Membranes were stripped and reprobed with anti-Erk or anti-Akt antibodies to determine total Erk or Akt protein expression. Relative changes in phosphorylation normalized to the total protein are indicated. Representative results of three experiments are shown.

The fate of cell’s death and survival is often determined by the Bcl-2 family proteins of anti- and proapoptotic regulators [35]. Bcl-2 and it close relatives, Bcl-XL and Bcl-w, protect cells from a wide range of cytotoxic agents. Other Bcl-2 relatives, such as Bax, Bak, and Bad, bind to Bcl-2 to promote rather than antagonize apoptosis. LPA rescued normal rat intestinal IEC-6 cells from camptothecin-induced apoptosis by inactivation of caspase 9 and 3 and upregulation of Bcl-2 expression [55]. In confluent Caco-2 cell cultures, inhibition of the MEK/Erk pathway induced apoptosis with a significant decrease in the expression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL, whereas a decrease in Bcl-2 but not Bcl-XL was observed in subconfluent Caco-2 or human intestinal crypt cells [28, 56]. In human T lymphoblastoma cells, Bax expression was suppressed in response to LPA with no effect on Bcl-2 or Bad [57]. We observed a decrease in Bcl-2 in etoposide-treated Caco-2 cells, consistent with earlier studies [28, 55, 56]. This decrease in the expression of Bcl-2 was blocked by inhibition of the MEK/Erk pathway. However, we did not observed a significant change in the expression level of Bcl-XL or Bax, although the Caco-2 cultures were about 5-7 days post-confluence. On the other hand, LPA treatment resulted in Bad phosphrylation. Phosphorylation of Bad as a pro-survival mechanism has been shown in a number of studies. Estradiol inactivates Bad in breast cancer cells via pathways dependent on both Erk and Akt [58]. Studies have identified Ser-112 and Ser-136 as the predominant phosphorylation sites of Bad [38, 39, 59]. Akt phosphorylates Bad at Ser-136 both in vitro and in vivo [38, 39], whereas p90 ribosomal S6 kinase (p90RSK), which is activated by Erk, phosphorylates Bad at Ser-112 [41, 60]. LPA induces Bad phosphorylation in HeLa cells via an Akt-dependent pathway [61]. In Caco-2 cells, we found that LPA increased Bad phosphorylation at Ser-112, but no change at Ser-136 was incurred. In fact, the phosphorylation level of Ser-136 was not changed by the inhibition of the PI3K or MEK/Erk pathways. The phosphorylation at Ser-112 correlates with the on-set of delayed activation of Erk at 13 h post-LPA treatment (Figure 5 and 7A). In addition, LPA-induced phosphorylation at Ser112 of Bad was prevented by U0126, but not by LY294002 or PTX. These data collectively suggest that the MAPK pathway is the major component responsible for the cell survival effect of LPA in Caco-2 cells. In addition to Ser-112 and Ser-136, Bad is phosphorylated at Ser-155 by protein kinase A (PKA) [62]. LPA2, which is the major LPA receptor in Caco-2 cells and only LPA receptor interacting with NHERF2, is known to inhibit forskolin –induced cAMP production and hence phosphorylation at Ser-155 was not studied in the current work [63].

The importance of Akt in LPA-mediated survival has been previously suggested. Activation of Akt protects primary lymphocytic leukemia cells and ovarian cancer cells from apoptosis, whereas Gi-mediated activation of MAPK is necessary for the survival of fibroblasts [13, 14, 64]. In these fibroblasts, the PI3K-Akt pathway showed a limited contribution to the survival activity of LPA [13]. In addition, studies have shown that the PI3K-Akt pathway play a critical role in the survival of intestinal epithelial cells [27, 28, 56]. In the present study, the inhibition of PI3K enhanced apoptotic cell death and completely abrogated the protective effect of LPA (Figure 6D). This effect is not caused by non-specific inhibition of Erk by LY294002 since the inhibition of PI3K by LY290042 does not affect LPA-induced activation of Erk in these cells as we have previously demonstrated [21]. Despite the significant effect by LY290042 on the caspase activity (Figure 6), we could not see a significant difference in the time-course of phosphorylation of Akt between control and NHERF2-knockdown cells treated with LPA alone or etoposide/LPA (Figure 7). However, the expression level of Bcl-2 was down-regulated in the presence of LY2940042, which is in consistent with the increase in the basal caspase activity in the presence of the inhibitor (Figure 6). Although the change in Bcl-2 expression level by the inhibition of PI3K is a plausible mechanism, alternative mechanisms are noteworthy. There is a close relationship between caspase activity and viability, and the role of Akt has been often attributed to the viability and growth of cells [65, 66]. Our data showed that the activation of Erk was almost completely abrogated in Caco-2/CL4 cells despite the robust activation of Akt. Therefore, these data suggest that the activation alone is not sufficient to protect cells but is necessary for the protection. Taken together, it seem plausible that that the PI3K-Akt pathway may sensitize the cells to etoposide-induced apoptosis by compromising the viability of Caco-2 cells. In support of this speculation, the basal caspase activity was elevated three-fold in the presence of LY294002 in contrast to a relatively smaller effect by U0126 or U73122 that blocked the MAPK pathway. Alternatively, LPA may protect cells from apoptosis in a PI3K-dependent but Akt-independent pathway. For example, microinjection of either wild-type or constitutively active Akt constructs in neurons does not protect against the neurons from extracellular amyloid βpeptide-induced toxicity [67]. In addition, other downstream effectors of PI3K, such as serum and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase 1, SGK1, which is activated by the phosphoinositide-dependent kinase has been involved in protecting cells from cell death [68, 69].

In summary, our results demonstrate that LPA protects Caco-2 cells from apoptosis and this protection involves activation of both MAPK and PI3K. LPA treatment is accompanied by upregulation of Bcl-2 expression, an increase in the phosphorylation level of Bad, and delayed and prolonged activation of Erk. The perturbation of LPA2-elicited signaling by knock down of NHERF2 significantly abrogates the ability of LPA to protect cells from apoptotic death. The pharmacological inhibition of PI3K significant compromised the survival of Caco-2 cells. Although the precise role of PI3K needs further studies, there was a decrease in the expression level of Bcl-2.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants (DK071597 and DK64399) and by the Emory University Research Committee. R.R. is supported a Research Fellowship Award from the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of America. H.S. and V.W.Y. are recipients of Georgia Cancer Coalition Distinguished Cancer Scientist Awards.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bronner MP, Culin C, Reed JC, Furth EE. The bcl-2 proto-oncogene and the gastrointestinal epithelial tumor progression model. Am J Pathol. 1995;146:20–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trisciuoglio D, Desideri M, Ciuffreda L, Mottolese M, Ribatti D, Vacca A, Del Rosso M, Marcocci L, Zupi G, Del Bufalo D. Bcl-2 overexpression in melanoma cells increases tumor progression-associated properties and in vivo tumor growth. J Cell Physiol. 2005;205:414–421. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamada T, Sato K, Komachi M, Malchinkhuu E, Tobo M, Kimura T, Kuwabara A, Yanagita Y, Ikeya T, Tanahashi Y, Ogawa T, Ohwada S, Morishita Y, Ohta H, Im D-S, Tamoto K, Tomura H, Okajima F. Lysophosphatidic Acid (LPA) in Malignant Ascites Stimulates Motility of Human Pancreatic Cancer Cells through LPA1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:6595–6605. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308133200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sano T, Baker D, Virag T, Wada A, Yatomi Y, Kobayashi T, Igarashi Y, Tigyi G. Multiple mechanisms linked to platelet activation result in lysophosphatidic acid and sphingosine 1-phosphate generation in blood. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21197–21206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201289200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mills GB, May C, Hill M, Campbell S, Shaw P, Marks A. Ascitic fluid from human ovarian cancer patients contains growth factors necessary for intraperitoneal growth of human ovarian adenocarcinoma cells. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:851–855. doi: 10.1172/JCI114784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tigyi G, Parrill AL. Molecular mechanisms of lysophosphatidic acid action. Prog Lipid Res. 2003;42:498–526. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(03)00035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ye X, Ishii I, Kingsbury MA, Chun J. Lysophosphatidic acid as a novel cell survival/apoptotic factor. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1585:108–113. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00330-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goetzl EJ, An S. Diversity of cellular receptors and functions for the lysophospholipid growth factors lysophosphatidic acid and sphingosine 1-phosphate. FASEB J. 1998;12:1589–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.An S, Dickens MA, Bleu T, Hallmark OG, Goetzl EJ. Molecular Cloning of the Human Edg2 Protein and Its Identification as a Functional Cellular Receptor for Lysophosphatidic Acid. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1997;231:619–622. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.An S, Bleu T, Hallmark OG, Goetzl EJ. Characterization of a Novel Subtype of Human G Protein-coupled Receptor for Lysophosphatidic Acid. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7906–7910. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.7906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aoki J, Bandoh K, Inoue K. A novel human G-protein-coupled receptor, EDG7, for lysophosphatidic acid with unsaturated fatty-acid moiety. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;905:263–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noguchi K, Ishii S, Shimizu T. Identification of p2y9/GPR23 as a Novel G Protein-coupled Receptor for Lysophosphatidic Acid, Structurally Distant from the Edg Family. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:25600–25606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302648200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang X, Yu S, LaPushin R, Lu Y, Furui T, Penn LZ, Stokoe D, Erickson JR, Bast RC, Jr, Mills GB. Lysophosphatidic acid prevents apoptosis in fibroblasts via G(i)-protein-mediated activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase. Biochem J. 2000;352:135–143. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu X, Haney N, Kropp D, Kabore AF, Johnston JB, Gibson SB. Lysophosphatidic Acid (LPA) Protects Primary Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Cells from Apoptosis through LPA Receptor Activation of the Anti-apoptotic Protein AKT/PKB. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:9498–9508. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410455200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furui T, LaPushin R, Mao M, Khan H, Watt SR, Watt MA, Lu Y, Fang X, Tsutsui S, Siddik ZH, Bast RC, Mills GB. Overexpression of edg-2/vzg-1 induces apoptosis and anoikis in ovarian cancer cells in a lysophosphatidic acid-independent manner. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:4308–4318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deng W, Balazs L, Wang DA, Van Middlesworth L, Tigyi G, Johnson LR. Lysophosphatidic acid protects and rescues intestinal epithelial cells from radiation- and chemotherapy-induced apoptosis. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:206–216. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu Y, Shen Z, Wiper DW, Wu M, Morton RE, Elson P, Kennedy AW, Belinson J, Markman M, Casey G. Lysophosphatidic acid as a potential biomarker for ovarian and other gynecologic cancers. JAMA. 1998;280:719–723. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.8.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fang X, Schummer M, Mao M, Yu S, Tabassam FH, Swaby R, Hasegawa Y, Tanyi JL, LaPushin R, Eder A, Jaffe R, Erickson J, Mills GB. Lysophosphatidic acid is a bioactive mediator in ovarian cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1582:257–264. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00179-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schulte KM, Beyer A, Kohrer K, Oberhauser S, Roher HD. Lysophosphatidic acid, a novel lipid growth factor for human thyroid cells: over-expression of the high-affinity receptor edg4 in differentiated thyroid cancer. Int J Cancer. 2001;92:249–256. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(200102)9999:9999<::aid-ijc1166>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shida D, Watanabe T, Aoki J, Hama K, Kitayama J, Sonoda H, Kishi Y, Yamaguchi H, Sasaki S, Sako A, Konishi T, Arai H, Nagawa H. Aberrant expression of lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) receptors in human colorectal cancer. Lab Invest. 2004;84:1352–1362. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yun CC, Sun H, Wang D, Rusovici R, Castleberry A, Hall RA, Shim H. LPA2 receptor mediates mitogenic signals in human colon cancer cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;289:C2–11. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00610.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu J, Lai Y-J, Lin W-C, Lin F-T. TRIP6 Enhances Lysophosphatidic Acid-induced Cell Migration by Interacting with the Lysophosphatidic Acid 2 Receptor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10459–10468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311891200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oh YS, Jo NW, Choi JW, Kim HS, Seo SW, Kang KO, Hwang JI, Heo K, Kim SH, Kim YH, Kim IH, Kim JH, Banno Y, Ryu SH, Suh PG. NHERF2 Specifically Interacts with LPA2 Receptor and Defines the Specificity and Efficiency of Receptor-Mediated Phospholipase C-β3 Activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5069–5079. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.11.5069-5079.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamada T, Ohoka Y, Kogo M, Inagaki S. Physical and Functional Interactions of the Lysophosphatidic Acid Receptors with PDZ Domain-containing Rho Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Factors (RhoGEFs) J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19358–19363. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414561200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Q, Liu M, Kozasa T, Rothstein JD, Sternweis PC, Neubig RR. Thrombin and lysophosphatidic acid receptors utilize distinct rhoGEFs in prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:28831–28834. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400105200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hande KR. Clinical applications of anticancer drugs targeted to topoisomerase II. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1400:173–184. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dufour G, Demers M-J, Gagne D, Dydensborg AB, Teller IC, Bouchard V, Degongre I, Beaulieu J-F, Cheng JQ, Fujita N, Tsuruo T, Vallee K, Vachon PH. Human Intestinal Epithelial Cell Survival and Anoikis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:44113–44122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405323200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gauthier R, Harnois C, Drolet J-F, Reed JC, Vezina A, Vachon PH. Human intestinal epithelial cell survival: differentiation state-specific control mechanisms. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C1540–1554. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.6.C1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yun CC, Oh S, Zizak M, Steplock D, Tsao S, Tse CM, Weinman EJ, Donowitz M. cAMP-mediated inhibition of the epithelial brush border Na/H exchanger, NHE3, requires an associated regulatory protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3010–3015. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee-Kwon W, Kim JH, Choi JW, Kawano K, Cha B, Dartt DA, Zoukhri D, Donowitz M. Ca2+-dependent inhibition of NHE3 requires PKC alpha which binds to E3KARP to decrease surface NHE3 containing plasma membrane complexes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;285:C1527–1536. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00017.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fam SR, Paquet M, Castleberry AM, Oller H, Lee CJ, Traynelis SF, Smith Y, Yun CC, Hall RA. P2Y1 receptor signaling is controlled by interaction with the PDZ scaffold NHERF-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8042–8047. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408818102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hirose Y, Berger MS, Pieper RO. p53 effects both the duration of G2/M arrest and the fate of temozolomide-treated human glioblastoma cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1957–1963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strasser A, O’Connor L, Dixit VM. Apoptotic signaling. Ann Rev Biochem. 2000;69:217–245. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Villa P, Kaufmann SH, Earnshaw WC. Caspases and caspase inhibitors. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:388–393. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01107-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cory S, Huang DC, Adams JM. The Bcl-2 family: roles in cell survival and oncogenesis. Oncogene. 2003;22:8590–8607. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang E, Zha J, Jockel J, Boise LH, Thompson CB, Korsmeyer SJ. Bad, a heterodimeric partner for Bcl-XL and Bcl-2, displaces Bax and promotes cell death. Cell. 1995;80:285–291. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90411-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zha J, Harada H, Yang E, Jockel J, Korsmeyer SJ. Serine phosphorylation of death agonist BAD in response to survival factor results in binding to 114-3-3 not BCL-XL. Cell. 1996;87:619–628. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.del Peso L, Gonzalez-Garcia M, Page C, Herrera R, Nunez G. Interleukin-3-induced phosphorylation of BAD through the protein kinase Akt. Science. 1997;278:687–689. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Datta SR, Dudek H, Tao X, Masters S, Fu H, Gotoh Y, Greenberg ME. Akt Phosphorylation of BAD Couples Survival Signals to the Cell-Intrinsic Death Machinery. Cell. 1997;91:231–241. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Downward J. How BAD phosphorylation is good for survival. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:E33–35. doi: 10.1038/10026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Valks DM, Cook SA, Pham FH, Morrison PR, Clerk A, Sugden PH. Phenylephrine Promotes Phosphorylation of Bad in Cardiac Myocytes Through the Extracellular Signal-regulated Kinases 1/2 and Protein Kinase A. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2002;34:749–763. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2002.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaufmann SH, Hengartner MO. Programmed cell death: alive and well in the new millennium. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:526–534. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02173-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu Y, Fang XJ, Casey G, Mills GB. Lysophospholipids activate ovarian and breast cancer cells. Biochem J. 1995;309:933–940. doi: 10.1042/bj3090933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ding Q, Wang Q, Evers BM. Alterations of MAPK Activities Associated with Intestinal Cell Differentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 2001;284:282–288. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cross TG, Scheel-Toellner D, Henriquez NV, Deacon E, Salmon M, Lord JM. Serine/Threonine Protein Kinases and Apoptosis. Exp Cell Res. 2000;256:34–41. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xia Z, Dickens M, Raingeaud J, Davis RJ, Greenberg ME. Opposing effects of ERK and JNK-p38 MAP kinases on apoptosis. Science. 1995;270:1326–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5240.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ishikawa Y, Kusaka E, Enokido Y, Ikeuchi T, Hatanaka H. Regulation of Bax translocation through phosphorylation at Ser-70 of Bcl-2 by MAP kinase in NO-induced neuronal apoptosis. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;24:451–459. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(03)00203-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luschen S, Falk M, Scherer G, Ussat S, Paulsen M, Adam-Klages S. The Fas-associated death domain protein/caspase-8/c-FLIP signaling pathway is involved in TNF-induced activation of ERK. Exp Cell Res. 2005;310:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen J-R, Plotkin LI, Aguirre JI, Han L, Jilka RL, Kousteni S, Bellido T, Manolagas SC. Transient Versus Sustained Phosphorylation and Nuclear Accumulation of ERKs Underlie Anti-Versus Pro-apoptotic Effects of Estrogens. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:4632–4638. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411530200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.He Y-Y, Huang J-L, Chignell CF. Delayed and Sustained Activation of Extracellular Signal-regulated Kinase in Human Keratinocytes by UVA: IMPLICATIONS IN CARCINOGENESIS. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53867–53874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405781200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee E-R, Kang Y-J, Kim J-H, Lee HT, Cho S-G. Modulation of Apoptosis in HaCaT Keratinocytes via Differential Regulation of ERK Signaling Pathway by Flavonoids. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31498–31507. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505537200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stefanelli C, Tantini B, Fattori M, Ivana Stanic, Pignatti C, Clo C, Guarnieri C, Caldarera CM, Mackintosh CA, Pegg AE, Flamigni F. Caspase activation in etoposide-treated fibroblasts is correlated to ERK phosphorylation and both events are blocked by polyamine depletion. FEBS Letters. 2002;527:223–228. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sautin YY, Crawford JM, Svetlov SI. Enhancement of survival by LPA via Erk1/Erk2 and PI 3-kinase/Akt pathways in a murine hepatocyte cell line. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C2010–2019. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00077.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kolch W. Coordinating ERK/MAPK signalling through scaffolds and inhibitors. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:827–837. doi: 10.1038/nrm1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Deng W, Wang DA, Gosmanova E, Johnson LR, Tigyi G. LPA protects intestinal epithelial cells from apoptosis by inhibiting the mitochondrial pathway. Am J Physiol Gastro Liver Physiol. 2003;284:G821–829. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00406.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harnois C, Demers M, Bouchard V, Vallée K, Gagné D, Fujita N, Tsuruo T, Vézina A, Beaulieu J, Côté A, Vachon PH. Human intestinal epithelial crypt cell survival and death: Complex modulations of Bcl-2 homologs by Fak, PI3-K/Akt-1, MEK/Erk, and p38 signaling pathways. J Cell Physiol. 2004;198:209–222. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goetzl EJ, Kong Y, Mei B. Lysophosphatidic acid and sphingosine 1-phosphate protection of T cells from apoptosis in association with suppression of Bax. J Immunol. 1999;162:2049–2056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fernando RI, Wimalasena J. Estradiol Abrogates Apoptosis in Breast Cancer Cells through Inactivation of BAD: Ras-dependent Nongenomic Pathways Requiring Signaling through ERK and Akt. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:3266–3284. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-11-0823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bonni A, Brunet A, West AE, Datta SR, Takasu MA, Greenberg ME. Cell survival promoted by the Ras-MAPK signaling pathway by transcription-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Science. 1999;286:1358–1362. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5443.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Frodin M, Gammeltoft S. Role and regulation of 90 kDa ribosomal S6 kinase (RSK) in signal transduction. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1999;151:65–77. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(99)00061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kang YC, Kim KM, Lee KS, Namkoong S, Lee SJ, Han JA, Jeoung D, Ha KS, Kwon YG, Kim YM. Serum bioactive lysophospholipids prevent TRAIL-induced apoptosis via PI3K/Akt-dependent cFLIP expression and Bad phosphorylation. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:1287–1298. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lizcano JM, Morrice N, Cohen P. Regulation of BAD by cAMP-dependent protein kinase is mediated via phosphorylation of a novel site, Ser155. Biochem J. 2000;349:547–557. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3490547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 63.Ishii I, Contos JJ, Fukushima N, Chun J. Functional comparisons of the lysophosphatidic acid receptors, LP(A1)/VZG-1/EDG-2, LP(A2)/EDG-4, and LP(A3)/EDG-7 in neuronal cell lines using a retrovirus expression system. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:895–902. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.5.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Baudhuin LM, Cristina KL, Lu J, Xu Y. Akt Activation Induced by Lysophosphatidic Acid and Sphingosine-1-phosphate Requires Both Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase and p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase and Is Cell-Line Specific. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:660–671. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.3.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miller RR, Leanza CM, Phillips EE, Blacquire KD. Homocysteine-induced changes in brain membrane composition correlate with increased brain caspase-3 activities and reduced chick embryo viability. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2003;136:521–532. doi: 10.1016/s1096-4959(03)00277-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Skurk C, Maatz H, Kim HS, Yang J, Abid MR, Aird WC, Walsh K. The Akt-regulated forkhead transcription factor FOXO3a controls endothelial cell viability through modulation of the caspase-8 inhibitor FLIP. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1513–1525. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304736200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang Y, Hong Y, Bounhar Y, Blacker M, Roucou X, Tounekti O, Vereker E, Bowers WJ, Federoff HJ, Goodyer CG, LeBlanc A. p75 Neurotrophin Receptor Protects Primary Cultures of Human Neurons against Extracellular Amyloid β Peptide Cytotoxicity. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7385–7394. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-19-07385.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Aoyama T, Matsui T, Novikov M, Park J, Hemmings B, Rosenzweig A. Serum and Glucocorticoid-Responsive Kinase-1 Regulates Cardiomyocyte Survival and Hypertrophic Response. Circulation. 2005;111:1652–1659. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000160352.58142.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Leong ML, Maiyar AC, Kim B, O’Keeffe BA, Firestone GL. Expression of the Serum- and Glucocorticoid-inducible Protein Kinase, Sgk, Is a Cell Survival Response to Multiple Types of Environmental Stress Stimuli in Mammary Epithelial Cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:5871–5882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211649200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]