Abstract

Early studies demonstrated roles for ribosomal protein L3 in peptidyltransferase center formation and the ability of cells to propagate viruses. More recent studies have linked these two processes via the effects of mutants and drugs on programmed -1 ribosomal frameshifting. Here, we show that mutant forms of L3 result in ribosomes having increased affinities for both aminoacyl- and peptidyl-tRNAs. These defects potentiate the effects of sparsomycin, which promotes increased aminoalcyl-tRNA binding at the P-site, while antagonizing the effects anisomycin, a drug that promotes decreased peptidyl-tRNA binding at the A-site. The changes in ribosome affinities for tRNAs also correlate with decreased peptidyltransferase activities of mutant ribosomes, and with decreased rates of cell growth and protein synthesis. In vivo dimethylsulfate (DMS) protection studies reveal that small changes in L3 primary sequence also have significant effects on rRNA structure as far away as 100Å, supporting an allosteric model of ribosome function.

Keywords: Ribosome, tRNA, drugs, structure

Introduction

Though it is now accepted that peptidyltransfer is a function of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) (reviewed in 1), the ribosomal proteins are thought to be required for optimal ribosomal peptidyltransferase activity (reviewed in 2). Ribosome reconstitution experiments in E. coli demonstrated that L3 is one of the first ribosomal proteins to be assembled into the ribosome (3), and single protein exclusion experiments showed that it is one of only three proteins required for peptidyltransferase activity (4-6). In yeast, L3 is encoded by a single copy gene called RPL3 (7). A mutant allele of RPL3 called tcm1-1 promoted simultaneous resistance to the peptidyltransferase inhibitors trichodermin and anisomycin (5;8-10), and the mak8-1 allele of RPL3 prevented cells from propagating the yeast ‘killer’ virus (11). In a previous publication, we demonstrated that a defect in programmed -1 ribosomal frameshifting (PRF) was responsible for the inability of mak8-1 cells to maintain the killer virus (12), and more recently we demonstrated that peptidyltransferase defects were the underlying cause of the altered frameshifting and virus maintenance phenotypes (13). In that study, a saturation mutagenesis approach identified four rpl3 alleles having these properties. These consisted of missense mutations at three positions (W255C, P257T, W255C+P257T, and I282T). Here we present a detailed combination of genetic, pharmacogenetic, biochemical, and molecular analyses to address the underlying causes of the drug resistance and peptidyltransferase defects promoted by these mutations. in vivo dimethylsulfate (DMS) protection studies revealed alterations in 25S rRNA structures approximately 100Å away from L3. These changes in structure correspond with mutant ribosomes having higher affinities for both aminoacyl-tRNA (aa-tRNA) and peptidyl-tRNAs. We propose that these effects are functionally propagated downstream, manifesting themselves as defects in peptidyltransferase function, which in turn affect the rate and precision of protein synthesis, and ultimately impact cell growth. Thus, even minor changes in the intermolecular interactions within the ribosome can have significant biological impacts, supporting an allosteric model of intraribosomal communication.

Materials and Methods

Strains, plasmids, genetic manipulation, preparation of tRNAs and of ribosomes

Construction of an RPL3::HIS3 gene deletion strain and of TRP1-CEN6 based rpl3 alleles were previously described (13). Methods to monitor cell growth, rates of protein synthesis, and drug sensitivity phenotypes were previously described (13;33). Cell doubling times (T) were calculated by fitting the exponential range of the growth curves to the following equation:

where at y is a ODλ=595 and x is a time.

Isolation and preparation of ribosomes, and aminoacylation of tRNAs and their subsequent acetylation followed previously described protocols (18). Aminoacylated tRNAs ([14C]Phe -aa-tRNAPhe and [14C]AcPhe-aa-tRNAPhe) were purified by HPLC as follows: tRNA aminoacylation reactions mixes were loaded onto a C4 column (J.T. Baker) in Buffer A (20 mM NH4Ac, 10 mM MgAc2, 400 mM NaCl, pH 5.0). Non-aminoacylated tRNAs and free phenylalanine were step eluted by addition of Buffer B to 35% v/v (Buffer B = Buffer A + 60% MeOH). Aminoacylated tRNAs were eluted using a linear gradient from 35% to 65% v/v of Buffer B. Peak radioactive fractions were pooled and dialyzed twice against 1 L of 5 mM KAc, pH 5.0. tRNAs were dried by lyophilization and resuspended in water to concentrations of 16 or 32 pmol/μl.

Binding of whole tRNAs with ribosomes and calculation of association constants

Binding of tRNAs with ribosomes was performed as described previously with minor modifications (13;18;33). Non-salt washed ribosomes (8 - 40 pmols per reaction) were incubated with indicated amounts of [14C]Phe -aa-tRNAPhe or [14C]AcPhe-aa-tRNAPhe (2-132 pmoles, 1091d.p.m./pmol) in 20 μl of RB buffer [38.5 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.2 at 25°C, 220 mM KAc, 22 mM MgAc2, 18% (v/v) EtOH] at 25°C for 30 min. Reactions were stopped by diluting reaction mixes with 1 ml of ice cold RB buffer without ethanol, immediately precipitated on 0.45μm nitrocellulose filters, and washed with 1ml of the dilution buffer. The reactions were performed in triplicate. tRNAs were in excess and the amount of ribosome-bound tRNAs were less then 10% in all reactions. Filters were dried and radioactivity quantitated using a scintillation counter. Background controls were performed using all components except ribosomes to determine the nonspecific adsorption of tRNAs to the filters. The background radioactivity was subtracted from the values obtained in the presence of ribosomes to identify the amount of tRNAs bound to ribosomes. To calculate Ka and to obtain the concentration of active ribosomes in each reaction (i.e. those able to bind tRNAs) the data were linearized using the following equation:

(where tRNA•RS signifies a tRNA- ribosome complex, and RS0 means total ribosomes) (19). The apparent is equal to ν multiplied by the fraction of active ribosomes. Ka was determined as (20). In the resulting Scatchard plot analysis of the tRNA binding data Ka was calculated as the slope of the regression trendline, and the X-axis intercept was equal to the fraction of active ribosomes (calculated to range from 40 - 90%).

The slopes of linear regression trendlines were calculated as:

The standard errors were calculated as:

(34).

In vivo methylation of yeast rRNA adenosines

Unprotected adenosine bases in yeast rRNAs were methylated with dimethylsulfate (DMS) using a modification of a previously described method (35). Logarithmically growing yeast cells (10 ml, O.D.595 approximately 0.5 -1.0/ml) were pelleted by centrifugation, resuspended in 0.5 ml of growth medium, DMS was added to concentrations of either 80 mM or 160 mM (3.8 μl and 7.6 μl of DMS stock solution), and incubated at room temperature for 2 min. Reactions were arrested by addition of ice cold μ-mercaptoethanol to a final concentration of 0.7 M (25 μl of stock solution), and 0.25 ml of ice cold water saturated isoamyl alcohol. Control cells were not treated with DMS. Total nucleic acids enriched for rRNAs were extracted as previously described (36). Reverse transcription reactions were performed at 45ºC using 10μg of rRNA, [32P]-labeled oligonucleotides 25-4 (5’ AGGCCACACTTTCATGG 3’), 25-6 (5’ AACTCGTCTCACGACGG 3’), or 25-7 (5’ CCTGATCAGACAGCCGC 3’), and AMV reverse transcriptase (Roche), which poorly utilizes modified bases as templates. Strong stops one nucleotide 5’ of modified bases were visualized by separating the reaction mixes through 6% polyacrylamide-urea denaturing gels and subsequent exposure to autoradiography. All experiments were performed in triplicate and band intensities were normalized to internal controls.

Computational analysis of ribosome structure

The crystal structure of the Haloarcula marismortui ribosome (37) was visualized using the Swiss PDB viewer.

Results

The mak8-1 form of L3 has an effect on the structure of the large subunit rRNA

The observation that ribosomes containing mutant forms of L3 had decreased peptidyltransferase activities was suggestive of an underlying structural defect. To test this hypothesis, we probed the effects of the mak8-1 form of the protein on the structure of 25S rRNA in vivo by treating cells with the RNA methylating agent DMS. In this method, unpaired adenine bases are the most reactive and are typically most sensitive to structural changes (although DMS is capable of methylating other bases) (14;15). Modification by DMS is detected as strong stops in reverse transcriptase primer extension assays one nucleotide 5’ of the site of methylation.

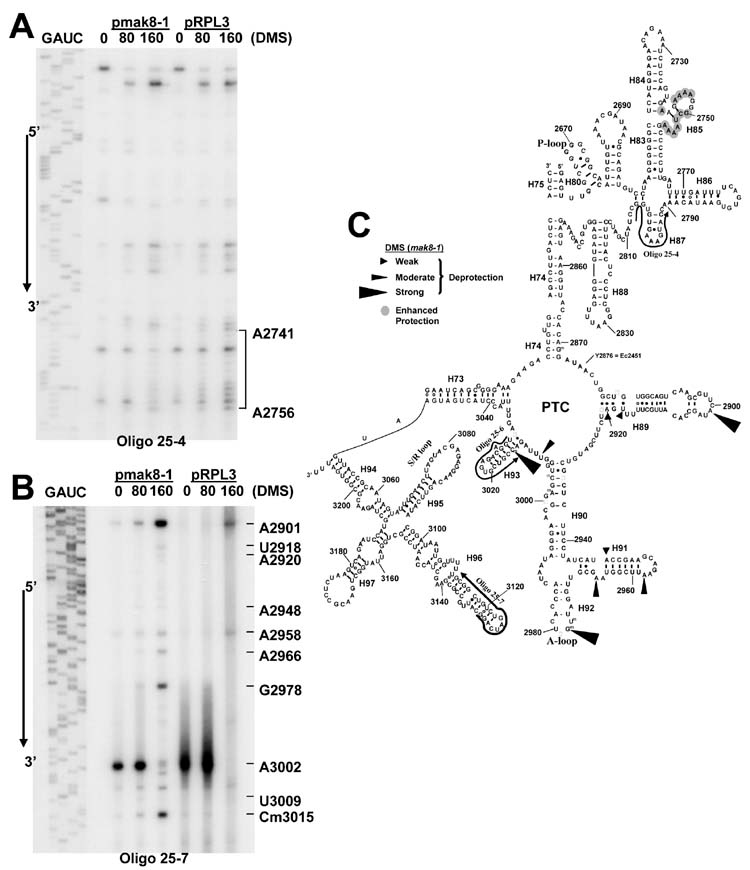

Primers 25-4, 25-6, and 25-7 (see Materials and Methods, also Fig. 1C) were used to determine the methylation patterns of 25S rRNAs from isogenic strains expressing wild-type L3 or mak8-1 through an approximately 400 nucleotide stretch of domain V, comprising the 25S rRNA nucleotides from approximately 2650 to 3040 (see Figure 5). The results show that expression of the mak8-1 form of L3 affects the structure of the 25S rRNA in a number of discrete regions. In particular, nucleotides in the loop region of helix 85 (A2741 - A2756) were better protected from DMS attack in mak8-1 ribosomes relative to wild-type (Figures 1A, 1C). Though the enhanced protection of these residues in mak8-1 ribosomes was modest, this pattern was observed in every repetition of this experiment. We suggest that the reason for the weak pattern of enhanced protection originates from the in vivo nature of the assay which probes all of the ribosomes in the cell in every different stage of elongation, each of these has a different status with regard to interactions with elongation factors and tRNAs. The observed pattern of enhanced protection in helix 85 suggests that the difference is due to altered interaction of mak8-1 ribosomes with another factor, most likely the T-loop of the peptidyl-tRNA, which has been shown to interact with the loop region of helix 85 in the T. thermophilis large subunit (16). The importance of this finding is explored below.

Figure 1. The mak8-1 form of L3 affects the structure of the 25S rRNA.

Isogenic wild-type and mak8-1 cells were treated with DMS in vivo, reverse transcriptase extension of [32P]-labeled primers were performed using the extracted rRNAs as templates, the reactions were separated through 6% urea-polyacrylamide denaturing gels, and visualized by autoradiography. A and B. Autoradiograms of the primer extension reactions using Oligo 25-4 (panel A) and Oligo 25-7 (panel B). Sequencing ladders are reverse labeled so as to reflect the sense strand of 25S rRNA in the indicated 5’ → 3’ directions. DMS concentrations are shown in mM. Specific protected or deprotected bases are indicated. C. Results from panels A and B mapped onto the 2-dimensional structure of yeast 25S rRNA. Shown is a selected portion of the domain V and domain VI region of yeast 25S rRNA. Numbering system employed here begins from the 5’ end of the S. cerevisiae 25S rRNA sequence.

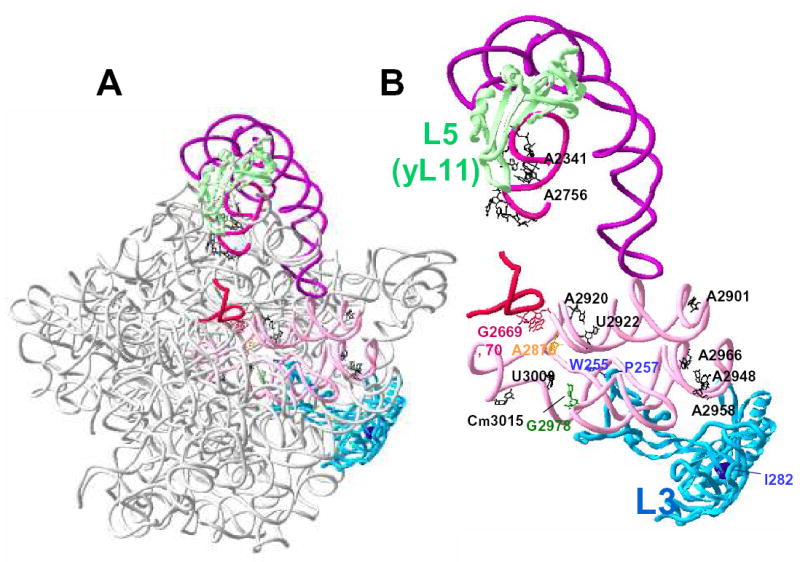

Figure 5. Mapping of the L3 mutants within the context of the H. marismortui 50S crystal structure at 2.4 Å.

A. Global view orienting L3 (blue) with regard to the large subunit rRNA. Specific regions of 25S rRNA are highlighted in color while the remainder of the molecule is rendered in grey. The highlighted regions are as follows: helix 80 (red), helices 89 - 93 (pink), helix 85 (lavender), and 5S rRNA (purple). Ribosomal protein L5 (yeast L11) is rendered in green. B. Close-up view focusing on the relationships between the particular L3 amino acids and rRNAs of interest. L3 is shown in blue, and the positions analogous to yeast W255, P257, and I282 are indicated. The peptidyltransferase center active site is shown in yellow (yeast A2876; E. coli A2451; H. marismortui 2486). The bases of the 23S rRNA that interact with the 3’ end of the aa-tRNA (yeast G2978; E. coli G2553; H. marismoutui U2588) are shown in green, and those that interact with the 3’ end of the peptidyl-tRNA and P-site (Yeast G2669, G2679; E. coli G2252 and G2253; H. marismortui G2284, G2285) are in red. Specific bases whose reactivity to DMS was altered in mak8-1 cells in vivo are outlined in black with the exception of G2978.

In contrast, expression of the mak8-1 form of L3 resulted in strong enhanced deprotection patterns of specific bases in helices 89, 91, 92 and 93, suggesting intrinsic differences in ribosome structure (Figures 1B, 1C). For example, in the proximal arm of helix 89 the non-Watson/Crick base pairs appear to be disrupted exposing U2918 and A2920 to the DMS modification. The reactivity of the A2901 in the distal loop of this helix is also changed. A similar pattern in the proximal arm and distal loop in helix 91 appears to render A2948, A2958, and A2966 hypersensitive to methylation by DMS. Hypermethylation was observed at position G2978 in the A-loop, the E. coli counterpart of which (G2554) is a cross-link site to a puromycin derivative (reviewed in 17). Moderate levels of deprotection are also observed at positions U3009 (the analogous E. coli U2584 is a footprint site for P-site tRNA, see ref. 17), and the naturally methylated C3015. For unknown reasons, the strong stop at A3002 disappeared at higher DMS concentrations: however, since this occurred in both wild-type and mak8-1 samples, we do not think this observation is informative in terms of a comparison of the two alleles. In sum, these studies demonstrate how small changes in the primary sequence of ribosomal protein L3 can have global impacts ribosome structure and function.

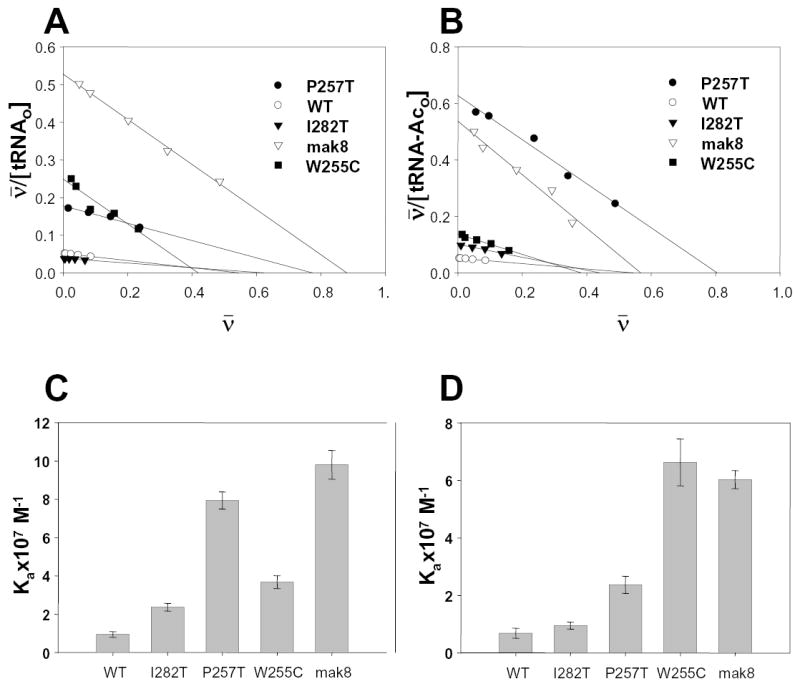

Mutant forms of L3 promote increased ribosome affinities for tRNAs

The observation that a region of the LSU rRNA that interacts with peptidyl-tRNA suggested that the structural changes conferred by the L3 mutants may affect how ribosomes functionally interact with tRNAs. To test this hypothesis, filter binding assays were used to monitor the affinities of wild-type and mutant ribosomes for tRNAs using [14C]Phe-aa-tRNAPhe and [14C]AcPhe-aa-tRNAPhe, which have previously demonstrated to bind exclusively to the A- and P-sites respectively (18). An inherent complication in the biochemical comparison of different samples is that specific activities will vary between samples depending on the inherent stability of a molecule and as a consequence of differences from preparation to preparation. Thus, the absolute amounts of bound tRNA were not directly comparable between samples, and did not reflect true Ka values. To overcome this problem, the data were linearized using the following equation:

| (equation 1) |

Given that yeast ribosomes have single binding sites for each of the tRNAs used in this study, i.e. that aa-tRNA binds to the A-site, and acyl-aa-tRNA binds to the P-site (18), the following equation:

| (equation 2) |

can be derived from equation 1 by dividing both sides by the concentration of ribosomes in the reaction mix (19). It is common to calculate a value for ν by using the concentration of ribosomes as determined by ODλ=260. As discussed above, in light of the problems associated with different specific activities resulting from diverse ribosome preparations, calculation of ν based upon total amounts of ribosomes would not reflect the true yield of the activity of a sample. In this case, the apparent ν (designated as ) is equal to ν multiplied by the fraction of active ribosomes. From equation 2, Ka can be determined as follows: (20). The resulting Scatchard plot analysis of the tRNA binding data are shown in Figures 2A and 2B. In these plots, Ka is calculated as the slope of the regression trendline, and the X-axis intercept is equal to the fraction of active ribosomes. The calculated Ka values are shown in Figures 2C and 2D, and in Table I. It is also important to note that we were unable to reach saturation for wild-type ribosomes at both the A- and P-sites, and for the I282T mutant at the P-site. This decreases the precision for determination of Ka values for these samples, increasing both the apparent Ka values and the numerical values for the errors. Despite this, it is readily apparent that ribosomes harvested from these cells have the lowest affinities for tRNAs. In order to be more precise, the corresponding Ka values for these samples are described as ≤ in Table I.

Figure 2. Ribosomes containing mutant forms of L3 have higher affinities for aa- and peptidyl-tRNAs.

Ribosomes harvested from cells expressing wild-type or mutant forms of L3 were incubated with excess amounts of either [14C]Phe -aa-tRNAPhe (A-site, panels A and C), or [14C]AcPhe-aa-tRNAPhe (P-site, panels B and D). A and B: Scatchard plot analyses of tRNA binding with wild-type and mutant ribosomes. Ka is equal to the slope of regression trendline and the X-axis intercept corresponds to the fraction of active ribosomes. C and D: Association constants of ribosomes containing the different mutants of ribosomal protein L3 for aa-tRNA at the A-site ([14C]Phe -aa-tRNAPhe, panel C), and for acylated-aatRNA at the P-site ([14C]AcPhe- aa-tRNAPhe, panel D).

Table I.

Summary of properties of rpl3 mutants

|

L3 varianta |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | I282T | P257T | W255C | mak8 | ||

| Dbl. Timeb | ~92 min | ~110 min | ~130 min | ~150 min | ~155 min | |

| Prot. Syn.c | 10331 | 8196 | 7233 | 6118 | 5762 | |

| A- sited | Anisomycine | WT | WT | r | R | R |

| aa-tRNA Kax107 M−1 f | ≤ 0.7 | 0.9 | 2.3 | 6.6 | 6.0 | |

| P- siteg | Sparsomycinh | WT | WT | S | S | S |

| p-tRNA Kax107 M−1 i | ≤ 0.9 | ≤ 2.4 | 7.9 | 3.7 | 9.8 | |

| Pep-Xferj | WT | ↓ | ↓ ↓ | ↓ ↓ ↓ | ↓ ↓ ↓ | |

| −1 PRFk | 1.9% | 3.8% | 4.5% | 4.6% | 4.8% | |

Plasmid-borne alleles of RPL3 were expressed in isogenic RPL3::HIS3 gene disruption backgrounds. These are arranged (from left to right) in increasing order of severity of their defects.

Approximate doubling time of cells.

Rates of incorporation of [35S]Methionine (cpm/min) in log-phase growth.

Monitors of A-site specific functions.

Anisomycin resistance of cells harboring the different RPL3 alleles. WT = wild-type; r = semi-resistant; R = strongly resistant.

Association constants of [14C]Phe -aa-tRNAPhe binding to the A-site. Ka values were calculated as described in Materials and Methods.

Monitors of P-site specific functions.

Sparsomycin resistance of cells harboring the different RPL3 alleles. WT = wild-type; S= hypersensitive.

Association constants of [14C]AcPhe -aa-tRNAPhe binding to the P-site. Ka values were calculated as described in Materials and Methods.

The number and direction of arrows provides a qualitative description of changes in peptidyltransferase activities (from ref. 13).

Programmed -1 ribosomal frameshifting efficiencies (from ref. 13).

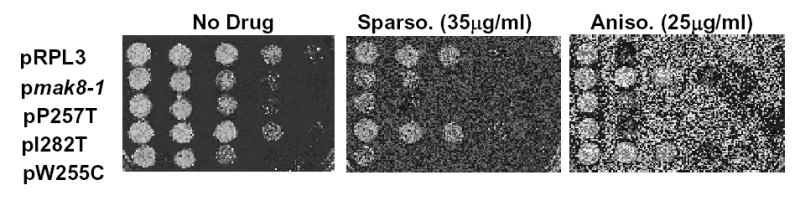

Altered drug sensitivities support the biochemical findings

Although the filter binding assays supported the hypothesis generated by the DMS protection analyses, they are not without their own problems. Although Scatchard plot analyses should control for differences in activities between ribosome preparations, the magnitudes of the errors in the quantitative estimations could be large enough to result the apparent differences in tRNA affinities for the ribosomes. Additionally, although as noted above that it has been definitively demonstrated that aa-tRNA binds to the A-site, and acyl-aa-tRNA binds to the P-site of yeast ribosomes (18), the mutant forms of L3 themselves could potentially reduce these specificities, resulting in apparent increases in ribosome affinities for these tRNA species.

In order to independently test whether the mutant forms of L3 affected the affinities of ribosomes for aa- and peptidyl-tRNAs, a pharmacogenetic approach was employed. Sparsomycin specifically increases the affinity of ribosomes for peptidyl-tRNA, making it useful as a probe for ribosomal P-site specific changes (reviewed in 21). Similarly, anisomycin decreases the affinity of ribosomes for aa-tRNA, and thus serves as a probe for changes specific to the ribosomal A-site (reviewed in 21). When assayed for growth in the presence of these agents, we found that the drug sensitivity/resistance profiles generally corresponded with the observed effects on tRNA binding tRNAs at both the ribosomal A-and P-sites (Figure 3, Table I). Specifically, intrinsically higher affinities of mutant ribosomes for peptidyl-tRNAs are predicted to potentiate the effects of sparsomycin: the observation that cells expressing the W255C, P257T, and mak8-1 forms of the protein were hypersensitive to this drug support this hypothesis. Similarly, mutant ribosomes with higher affinities for aa-tRNAs might antagonize the effects of anisomycin: this model is supported by the observation that cells expressing W255C and mak8-1 were very resistant to anisomycin, while those expressing the P257T mutant were slightly resistant. In sum, the convergence of the drug hypersensitivity/resistance phenotypes with the results of the filter binding assays support the model that the mutant forms of L3 result in ribosomes having higher affinities for both aa- and peptidyl-tRNAs.

Figure 3. Ribosomes containing mutant forms of L3 have altered drug sensitivity phenotypes.

Mid-log phase cultures of isogenic strains harboring the various plasmid-borne RPL3 alleles were spotted in 10-fold dilutions onto SD-trp alone (No Drug), SD-trp containing sparsomycin (35μg/ml), or SD-trp plus anisomycin (25μg/ml). Cells were grown at 30°C for three days.

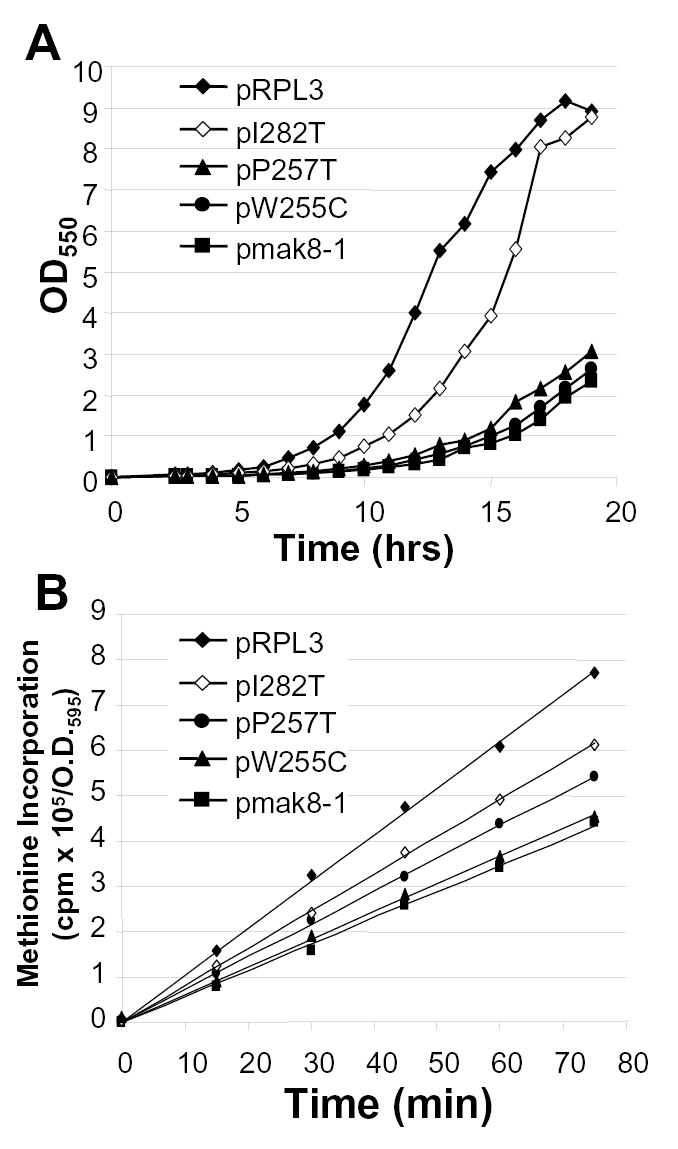

Expression of mutant forms of L3 affects rates of cell growth and protein synthesis

In an effort to further understand the consequences of expressing mutant forms of L3 on cell growth and division, RPL3::HIS3 gene knockout strains harboring plasmid-borne wild-type or mutant alleles of rpl3 were inoculated into standard defined medium lacking tryptophan (SD - trp) to O.D.550 ≈ 0.01, and growth rates were determined by monitoring optical densities of aliquots taken at 1 h intervals. The growth curves are shown in Fig. 4A. The results show that the I282T mutant had the least dramatic effect on cell growth rates (doubling time ~110 min, compared to ~92 min for cells expressing the wild type gene, see Table I). More significantly, expression of the peptidyltransferase center-proximal mutants, i.e. W255C, P257T, and mak8-1 (W255C + P257T) had dramatic effects on cell growth rates (doubling times of 150 min, 130 min and 155 min respectively, see Table I). As the gene in question encodes a ribosomal protein, we assayed the effects of the mutations on protein synthesis by examining the rates of [35S]methionine incorporation into the TCA-precipitable fraction of cell lysates. The results of this experiment are shown in Figure 4B and Table I. The results indicate that, with respect to protein synthesis, the mutants exhibited a pattern similar to those observed with regard to growth rates, i.e. WT > I282T > P257T > W255C > mak8-1.

Figure 4. Global effects of rpl3 mutants on cell growth and protein synthesis.

A. Isogenic RPL3::HIS3 gene knockout strains expressing plasmid-borne wild type RPL3 or mutant rpl3 alleles were diluted in selective medium (SD - trp) to O.D.550 = 0.01, and growth rates were determined by monitoring optical densities of aliquots taken at 1 h intervals. B. [35S]methionine was added to mid-logarithmically growing isogenic RPL3::HIS3 strains expressing plasmid borne wild type RPL3 or the indicated rpl3 alleles and samples were harvested at 0 min and at 15 min intervals for 75 min. Incorporation of the [35S]-methionine was monitored by cold trichloroacetic acid precipitation as previously described (33). All time points were taken in triplicate.

Discussion

In yeast, the first genetic phenotypes associated with L3 were the simultaneous resistance to trichodermin and anisomycin and the inability to maintain the killer virus (8-11;22-24). The data presented in this study suggest that increased affinities of these mutant ribosomes for aa-tRNA acts to antagonize the effects of drugs such as anisomycin, which inhibits binding of the 3’ end of the aa-tRNA to the ribosomal A-site. In contrast, the hypersensitivities of yeast cells expressing the L3 mutants to sparsomycin are due to the additive effect of both the mutations and the drug, combining to further increase binding of peptidyl-tRNAs to the ribosome. In particular, the extent of anisomycin resistance and sparsomycin hypersensitivity correspond with the severity of A- and P-site specific tRNA binding defects respectively.

Table I demonstrates strong correspondences between the tRNA binding defects and effects downstream, i.e. peptidyltransferase activities, programmed -1 ribosomal frameshift efficiencies, and rates of protein synthesis and cell growth. We propose that altered affinities for both peptidyl- and aa-tRNAs directly affect peptidyltransferase activity. With regard to programmed ribosomal frameshifting and virus propagation, decreased peptidyltransfer rates increase the amount of time that ribosomes are paused at -1 PRF signals after accommodation but prior to peptidyltransfer (reviewed in 25). This is consistent with the “9Å Solution” of programmed -1 ribosomal frameshifting, which posits that the mRNA within the ribosome slips one base in the 3’ direction rather than the tRNAs having to move 5’ by one nucleotide (26). Further, the observation made here, i.e. that increased ribosomal affinity for both peptidyl- and aa-tRNAs can account for increased -1 PRF, argues against a recently proposed model that all translational recoding is primarily dependent on P-site tRNA slippage (27). This view is further supported by the finding that decreased ribosome affinity for aa-tRNA alone can also result in decreased peptidyltransferase activity, in turn promoting increased efficiencies in -1 PRF (13). These biochemical alterations have important implications for the development of antiviral agents: the resulting increased efficiencies in programmed -1 ribosomal frameshifting leads to an imbalance in the ratio of viral Gag to Gag-pol proteins, which negatively impact on viral particle assembly. The findings presented here also support our previously described model in which W255 plays an important role in L3 function, the nearby proline forms an important turn in the protein so as to properly position the tryptophan, and the isoleucine is only important insofar as it is part of the platform upon which the “finger” of L3 is positioned (13).

Figure 5 depicts the large subunit rRNA nucleotides and L3 amino acid residues identified in this study within the context of the 2.5Å H. marismortui ribosome structure. Figure 5A presents a global view, while Figure 5B focuses on the relationships between the specific L3 amino acids and bases of 25S rRNA with emphasis on the tRNA binding regions and catalytic center of the large subunit. Ribosomal proteins L3 and L5 (the yeast homolog is called L11) are highlighted, as are important regions of the large subunit rRNA that interact with these proteins (helices 80, 85, 89 - 93, and 5S rRNA). Localization of the bases identified by the DMS protection experiments (Figure 5, black) shows that changing two amino acids in L3 had dramatic, long distance effects on 25S rRNA structure. For example, the distance between W255 and helix 85 is approximately 94Å, that between helix 85 and A2958 is roughly110Å, and the spacing between A2901 and C3015 is about 77Å. When the molecular surfaces of the atoms within the ribosome are filled in, the long distance effects of these mutations are less surprising: the ribosome is a highly structured macromolecule containing very little unordered internal space. Small local changes would impinge upon and distort the immediate neighboring space, in turn promoting the outward radiation of spatial displacement. Given the high degree of limitation on the primary amino acid structure of L3, it is not surprising that so few mutants were discovered in the original screen (13). We suggest that the reason why so few lethal mutants were identified was because most of them were probably dominant, and thus either killed or severely inhibited cell growth even in the presence of the wild-type gene. Currently we are screening our library of rpl3 alleles for drug dependent mutants in an effort to further our understanding of the relationships between L3 structure and function.

As for the function of ribosomal protein L3, our findings lead us to the following non-mutually exclusive hypotheses: 1) that the L3 finger may play an important role in the proper assembly of the peptidyltransfer center; 2) that it may be required for the correct positioning of the A- and P-site tRNA 3’ ends; and 3) that it may be important for the correct positioning of the catalytic rRNA residues. The close proximity of L3 residue W255 to the aa-tRNA suggests that the effects of the mutant on methylation of G2978 and on aa-tRNA binding are direct. In contrast, the moderate deprotection of U3009, and the relatively large distance (approximately 25Å) between L3 and the donor stem contact (G2669, 2670 in Fig. 5B) might suggest a lesser, perhaps indirect effect on peptidyl-tRNA-rRNA interactions. However, the observed rough equivalence between the relative degrees of the changes in the association constants of mutant ribosomes for peptidyl-tRNAs and aa-tRNAs argues against this. The enhanced protection of bases in helix 85 from DMS attack in the mak8-1 mutants further supports the notion that the mutant affects peptidyl-tRNA binding, as this is the site of contact between the peptidyl-tRNA T-loop and the large subunit rRNA (16).

In addition, the observation that the binding affinities of both aa- and peptidyl-tRNAs were enhanced in all of the mutants supports the hypothesis that there are more than one possible binding state for A- and P-site bound tRNAs, only one of which is maximally catalytic (28-31). An intriguing question raised by this study is whether the L3 finger merely serves a static scaffolding function, or does it actively partake in the dynamic functions of the ribosome? With regard to this latter possibility, the mak8-1 form of L3 resulted in changes in 25S rRNA structure along a line from helix 89 to 93. The chain formed by these helices of the large subunit rRNA makes a connection between the peptidyltransferase center, the GTPase-associated center of the large subunit, and 5S rRNA. These interconnections support an allosteric model in which the various ribosomal functions are coordinated by the intramolecular crosstalk between all of the different functional centers of this complex macromolecule (32).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Reed Wickner for the gift of the original mak8-1 strain, Rick Stewart, Ewan Plant, Jason Harger, Jennifer Baxter, and Kecia Rigsby for both technical and editorial assistance, and Petr V. Sergiev, M.J. Fournier, Phil Farabaugh, Kristi Muldoon and Jonathan Jacobs for insightful discussions regarding ribosome structure and function. This work was supported by grants to JDD from the NIH (R01 GM58859, GM62143), and the NSF (MCB-9807890).

References

- 1.Steitz TA, Moore PB. RNA, the first macromolecular catalyst: the ribosome is a ribozyme) Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:411–8. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00169-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noller HF. Ribosomes and translation) Annu Rev Biochem. 1997;66:679–716. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roth HE, Nierhaus KH. Assembly map of the 50-S subunit from Escherichia coli ribosomes, covering the proteins present in the first reconstitution intermediate particle) Eur J Biochem. 1980;103:95–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb04292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Franceschi FJ, Nierhaus KH. Ribosomal proteins L15 and L16 are mere late assembly proteins of the large ribosomal subunit). Analysis of an Escherichia coli mutant lacking L15. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:16676–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schulze H, Nierhaus KH. Minimal set of ribosomal components for reconstitution of the peptidyltransferase activity. EMBO J. 1982;1:609–13. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01216.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hampl H, Schulze H, Nierhaus KH. Ribosomal components from Escherichia coli 50 S subunits involved in the reconstitution of peptidyltransferase activity) J Biol Chem. 1981;256:2284–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mager WH, Planta RJ, Ballesta JG, et al. A new nomenclature for the cytoplasmic ribosomal proteins of Saccharomyces cerevisiae) Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4872–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grant PG, Schindler D, Davies JE. Mapping of trichodermin resistence in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a genetic locus for a component of the 60S ribosomal subunit. Genetics. 1976;83:667–73. doi: 10.1093/genetics/83.4.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jimenez A, Sanchez L, Vazquez D. Simultaneous ribosomal resistance to trichodermin and anisomycin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutants) Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975;383:427–34. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(75)90312-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schindler D, Grant P, Davies J. Trichodermin resistance--mutation affecting eukaryotic ribosomes. Nature. 1974;248:535–6. doi: 10.1038/248535a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wickner RB, Leibowitz MJ. Chromosomal and non-chromosomal mutations affecting the “killer character” of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1974;76:423–32. doi: 10.1093/genetics/76.3.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peltz SW, Hammell AB, Cui Y, Yasenchak J, Puljanowski L, Dinman JD. Ribosomal Protein L3 Mutants Alter Translational Fidelity and Promote Rapid Loss of the Yeast Killer Virus) Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:384–91. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meskauskas A, Harger JW, Jacobs KLM, Dinman JD. Decreased peptidyltransferase activity correlates with increased programmed -1 ribosomal frameshifting and viral maintenance defects in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. RNA. 2003;9:982–92. doi: 10.1261/rna.2165803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green R, Noller HF. Ribosomes and translation) Annu Rev Biochem. 1997;66:679–716. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lempereur L, Nicoloso M, Riehl N, Ehresmann C, Ehresmann B, Bachellerie JP. Conformation of yeast 18S rRNA. Direct chemical probing of the 5′ domain in ribosomal subunits and in deproteinized RNA by reverse transcriptase mapping of dimethyl sulfate-accessible. Nucleic Acids Res. 1985;13:8339–57. doi: 10.1093/nar/13.23.8339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yusupov MM, Yusupova GZ, Baucom A, et al. Crystal Structure of the Ribosome at 5.5 Å Resolution. Science. 2001;292:883–96. doi: 10.1126/science.1060089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mueller F, Sommer I, Baranov P, et al. The 3D arrangement of the 23 S and 5 S rRNA in the Escherichia coli 50 S ribosomal subunit based on a cryo-electron microscopic reconstruction at 7.5 Å resolution) J Mol Biol. 2000;298:35–59. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Triana F, Nierhaus KH, Chakraburtty K. Transfer RNA binding to 80S ribosomes from yeast: evidence for three sites) Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1994;33:909–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fersht A, Structure and mechanism in protein science. New York: W.H. Freeman and Co., 1998.

- 20.Harris R, Pestka S. Studies on the formation of transfer ribonucleic acid-ribosome complexes. XXIV. Effects of antibiotics on binding of aminoacyloligonucleotides to ribosomes. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:1168–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pestka S. Inhibitors of protein synthesis. In: Weissbach H, Pestka S, editors. Molecular mechanismns of protein biosynthesis. New York: Academic Press, 1977.

- 22.Fried HM, Warner JR. Cloning of yeast gene for trichodermin resistance and ribosomal protein L3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:238–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.1.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schultz LD, Friesen JD. Nucleotide sequence of the tcm1 gene (ribosomal protein L3) of Saccharomyces cerevisiae) J Bacteriol. 1983;155:8–14. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.1.8-14.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wickner RB, Porter-Ridley S, Fried HM, Ball SG. Ribosomal protein L3 is involved in replication or maintenance of the killer double-stranded RNA genome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:4706–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.15.4706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harger JW, Meskauskas A, Dinman JD. An 'integrated model' of programmed ribosomal frameshifting and post-transcriptional surveillance. TIBS. 2002;27:448–54. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02149-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Plant EP, Jacobs KLM, Harger JW, et al. The 9-angstrom solution: How mRNA pseudoknots promote efficient programmed -1 ribosomal frameshifting. RNA. 2003;9:168–74. doi: 10.1261/rna.2132503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baranov PV, Gesteland RF, Atkins JF. P-site tRNA is a crucial initiator of ribosomal frameshifting. RNA. 2004;10:221–30. doi: 10.1261/rna.5122604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herner AE, Goldberg IH, Cohen LB. Stabilization of N-acetylphenylalanyl transfer ribonucleic acid binding to ribosomes by sparsomycin. Biochemistry. 1969;8:1335–44. doi: 10.1021/bi00832a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wower J, Kirillov SV, Wower IK, Guven S, Hixson SS, Zimmermann RA. Transit of tRNA through the Escherichia coli ribosome. Cross-linking of the 3′ end of tRNA to specific nucleotides of the 23 S ribosomal RNA at the A, P, and E sites. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37887–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005031200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirillov SV, Porse BT, Garrett RA. Peptidyl transferase antibiotics perturb the relative positioning of the 3′-terminal adenosine of P/P′-site-bound tRNA and 23S rRNA in the ribosome. RNA. 1999;5:1003–13. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299990568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Porse BT, Kirillov SV, Awayez MJ, Ottenheijm HC, Garrett RA. Direct crosslinking of the antitumor antibiotic sparsomycin, and its derivatives, to A2602 in the peptidyl transferase center of 23S-like rRNA within ribosome-tRNA complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9003–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith MW, Meskauskas A, Wang P, Sergiev PV, Dinman JD. Saturation mutagenesis of 5S rRNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Molecular & Cellular Biology. 2001;21:8264–75. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.24.8264-8275.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meskauskas A, Baxter JL, Carr EA, et al. Delayed rRNA processing results in significant ribosome biogenesis and functional defects) Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:1602–13. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.5.1602-1613.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Acton FS, Analysis of Straight-Line Data. New York: Dover Press, 1966.

- 35.Mereau A, Fournier R, Gregoire A, et al. An in vivo and in vitro structure-function analysis of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae U3A snoRNP: protein-RNA contacts and base-pair interaction with the pre-ribosomal RNA. J Mol Biol. 1997;273:552–71. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fried HM, Fink GR. Electron microscopic heteroduplex analysis of “killer” double-stranded RNA species from yeast) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:4224–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.9.4224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ban N, Nissen P, Hansen J, Moore PB, Steitz TA. The complete atomic structure of the large ribosomal subunit at 2.4 A resolution. Science. 2000;289:905–20. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5481.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]