Abstract

Spontaneous autoxidation of tetrameric Hbs leads to the formation of Fe (III) forms, whose physiological role is not fully understood. Here we report structural characterization by EPR of the oxidized states of tetrameric Hbs isolated from the Antarctic fish species Trematomus bernacchii, Trematomus newnesi, and Gymnodraco acuticeps, as well as the x-ray crystal structure of oxidized Trematomus bernacchii Hb, redetermined at high resolution. The oxidation of these Hbs leads to formation of states that were not usually detected in previous analyses of tetrameric Hbs. In addition to the commonly found aquo-met and hydroxy-met species, EPR analyses show that two distinct hemichromes coexist at physiological pH, referred to as hemichromes I and II, respectively. Together with the high-resolution crystal structure (1.5 Å) of T. bernacchii and a survey of data available for other heme proteins, hemichrome I was assigned by x-ray crystallography and by EPR as a bis-His complex with a distorted geometry, whereas hemichrome II is a less constrained (cytochrome b5-like) bis-His complex. In four of the five Antartic fish Hbs examined, hemichrome I is the major form. EPR shows that for HbCTn, the amount of hemichrome I is substantially reduced. In addition, the concomitant presence of a penta-coordinated high-spin Fe (III) species, to our knowledge never reported before for a wild-type tetrameric Hb, was detected. A molecular modeling investigation demonstrates that the presence of the bulkier Ile in position 67β in HbCTn in place of Val as in the other four Hbs impairs the formation of hemichrome I, thus favoring the formation of the ferric penta-coordinated species. Altogether the data show that ferric states commonly associated with monomeric and dimeric Hbs are also found in tetrameric Hbs.

INTRODUCTION

The oxygenated forms of myoglobin and Hb are easily oxidized to their ferric (met) forms. Although autoxidation is inevitable in nature for all oxygen-binding heme proteins, the met-Hb content of freshly drawn blood is usually maintained within 1%–2% by virtue of a strong reducing environment (1). Indeed, autoxidation is of clinical and of chemical interest, as it influences the life span of the erythrocyte, or the usefulness of Hb-based blood substitutes (2).

Autoxidation rate and products depend on several factors, including the dioxygen pressure, pH, and the nature of the globin moiety. Recent spectroscopic and crystallographic studies revealed that the oxidation of tetrameric Hbs from several species can lead to the formation of different products (3–5). Under physiological conditions, the oxidation of mammalian and temperate fish Hbs leads to the formation of the aquo-met hexa-coordinated form both in α- and β-subunits, whereas the oxidation of AF-Hbs leads to the formation of an aquo-met form at the α-chains and of an endogenous bis-His complex at the β-chains (β-hemichrome). EPR (6), molecular dynamics (7), and crystallographic (8) studies showed that mammalian Hbs can form hemichromes under denaturing conditions, but preferentially at the α-chains (α-hemichrome).

Ferric forms of Hb are physiologically inert to further oxygenation, but several subsequent side reactions in the Hb autoxidation reaction may interfere or merge into other biochemical pathways, including the formation of a hemichrome whose physiological role is controversial. The bis-His complex can be involved in ligand binding (9–10) in the in vivo reduction of met-Hb, in Heinz body formation, and in NO scavenging (3). Recently, it has been suggested that hemichrome can be involved in Hb protection from peroxidation attack (11). Indeed, the α-hemichrome species of isolated human α-subunits complexed with the AHSP does not exhibit peroxidase activity (11).

The crystal structure of oxidized forms of HbTb (5) and of Hb1Tn (4), hitherto reported at room temperature and moderate resolution, provided clues on the structure of hemichromes in AF-Hbs. The oxidized, i.e., α-aquo-met, β-hemichrome, forms of these proteins have similar quaternary structure, intermediate between the canonical R and T states of Hb (4,5). The formation of the β-hemichrome is associated with a scissors-like movement of the EF helices in the β-units, which makes the distance between distal and proximal His close enough to form the endogenous bis-His complex. This endogenous hexa-coordination is also favored by sliding of the β-heme plane, which moves toward the exterior of the heme pocket.

Here we report an EPR study on oxidized forms of HbTb, Hb1Tn, Hb2Tn, HbCTn, and HbGa at physiological pH. This study reveals that a wide variety of ferric forms are present in frozen solution, including aquo-met and hydroxy-met, two endogenous hemichromes, and one unligated high-spin ferric form observed for HbCTn. The high-resolution crystal structure (1.5 Å) of the α-aquo-met β-hemichrome form of HbTb suggests that the more abundant hemichrome has a distorted iron bis-His geometry, which is consistent with EPR properties. HbCTn exhibits EPR properties different from the other four AF-Hbs. Molecular modeling is used to obtain a structural explanation for the distinct EPR properties exhibited by HbCTn as compared to the other four AF-Hbs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Hemoglobin purification

The purification and the storage of the five Antarctic fish Hbs (HbTb from T. bernacchi (12), Hb1Tn, Hb2Tn, and HbCTn from T. newnesi (13), and HbGa from G. acuticeps (14)) were performed as previously reported. The five AF-Hbs were oxidized with K3Fe(CN)6; excess was removed by gel filtration with a Sephadex G-25 column.

Electron paramagnetic resonance

Continuous wave EPR spectra were obtained at 12 K using a Varian (Palo Alto, CA) E112 spectrometer equipped with a Systron-Donner frequency counter and a PC-based data acquisition program. The samples of ferric HbTb, Hb1Tn, Hb2Tn, and HbGa were at 0.5 mM tetramer concentration in 50 mM Hepes pH 7.6. Spectra were recorded at a microwave frequency of 9.29 GHz, a microwave power of 10 mW, a modulation frequency of 100 kHz, and a modulation amplitude of 5 G.

X-ray crystallography

Crystallization of ox-HbTb was carried out at pH 7.6 and room temperature via liquid-diffusion technique, using a capillary (5). Diffraction data on HbTb crystals were collected at high resolution (1.48 Å) at the XRD1 beam-line of Elettra synchrotron. A data set was collected at 100 K using glycerol as cryoprotectant and processed with the program suite HKL (15). A summary of the data-processing statistics is given in Table 1. The coordinates of the low-resolution (2.5 Å) α-aquo-met, β-hemichrome structure of HbTb (PDB code 1S5Y) were used as a starting model to refine the structure of oxy-HbTb. The refinement was performed using the program CNS (16). The refinement runs were followed by manual intervention using the molecular graphic program O (17) to correct minor errors in the position of the side chains. The molecular graphic program O (17) was used also to perform molecular modeling. Seven side chains are modeled in alternative conformations. Water molecules were identified by evaluating the shape of the electron density and the distance of potential hydrogen bond donors and/or acceptors. At convergence, the R-factor value was 0.199 (R-free 0.234). A summary of the refinement statistics is also reported in Table 1. The coordinates of the structure have been deposited in the PDB (18), with entry code 2PEG.

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| Diffraction data | |

| Space group | C2 |

| Cell parameters | |

| a (Å) | 87.16 |

| b (Å) | 87.74 |

| c (Å) | 55.38 |

| β (°) | 97.66 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 30.00–1.48 (1.53–1.48)* |

| No. of unique reflections | 74461 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.4 (99.6)* |

| Rmerge (%) | 3.5 (22.7)* |

| I/σ(I) | 28.9 (4.0) |

| Redundancy | 5 |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 30.00–1.48 |

| R (%) | 19.9 |

| Rfree (%) | 23.4 |

| No. of protein atoms | 2239 |

| No. of water molecules | 215 |

| rms deviation | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.009 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.90 |

| Average atomic displacement | |

| Protein (Å2) | 16.4 |

| Heme (Å2) | 18.4 |

| Water molecules (Å2) | 27.2 |

The numbers in parentheses refer to the outermost shell.

Comparison of bis-His heme structures and EPR parameters

The orientations of His axially ligated to the iron heme were derived for 11 hemichromes found in the Hb superfamily using structures from the PDB and this work (4,5,8,11,19–25). In particular, the tilt angles between the heme plane and the distal His-imidazole plane (θd), the tilt angle between the heme plane and the proximal His-imidazole plane (θp), the dihedral angle between the proximal- and the distal-His imidazole planes (ω), together with the bond angle formed by the Nɛ2 atom of proximal His, the Fe, and the Nɛ2 atom of distal His (NFeN) have been calculated using CCP4 (26). These data have been compared to those obtained for bis-His adducts of heme proteins reviewed in Zaric et al. (27) and have been correlated here with the EPR signals collected for these systems.

RESULTS

Electron paramagnetic resonance spectra

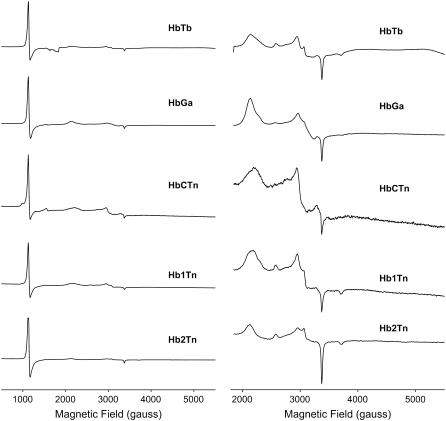

The EPR spectra of the five ferric Hbs from T. bernacchi (HbTb), T. newnesi (three components Hb1Tn, Hb2Tn, and HbCTn), and G. acuticeps (HbGa) at pH 7.6, measured at 12 K, show the presence of both an axial high-spin ferric signal and three rhombic low-spin ferric signals (Fig. 1). High-spin signals with identical g values (5.88 and 2.01) were found for HbTb, Hb1Tn, Hb2Tn, and HbGa, whereas the g = 5.88 signal of HbCTn (Fig. 1, left panel, middle spectrum) exhibits an increase in rhombicity (28) as compared to the other four AF-Hbs. Three sets of low-spin signals with gmax and gmid values of 3.2 and 2.3/2.2, 2.9 and 2.3/2.2, 2.6 and 2.2, respectively, were resolved for the five AF-Hbs (Fig. 1, right panel). In addition, one low-spin gmin value of 1.8 was resolved. The EPR spectra shown in Fig. 1 are first derivatives of the EPR absorption envelopes, which differ in shape for high-spin and low-spin ferric signals, and span ∼2300 G for the high-spin ferric signals and over 3500 G for some low-spin ferric signals at X band, the microwave frequency region used (29,38). For these reasons, the intensities of spectral components in Fig. 1, left panel, due to high-spin and low-spin hemes vary substantially in intensity, even though the AF-Hbs contain comparable amount of high-spin and low-spin hemes. One of the three low-spin forms (g = 2.6, 2.2), to which the gmin = 1.8 signal is assigned, clearly arises from a hydroxy-met form (class O of the Truth Table originally published by Blumberg and Peisach (29)). It is of note that unlike the other four AF-Hbs, the hydroxide form is not resolved in HbCTn (Fig. 1, right panel), suggesting that the pKa of the bound water of the aquo-met center is higher than that for the other four AF-Hbs.

FIGURE 1.

CW-EPR spectra of five ferric AF-Hbs: HbTb, HbGa, HbCTn, Hb1Tn, and Hb2Tn. The protein concentration was 0.5 mM tetramer, buffer was 50 mM HEPES pH = 7.6. Spectra were recorded at 12 K, a microwave frequency of 9.29 GHz, a microwave power of 10 mW, a modulation frequency of 100 kHz, and a modulation amplitude of 5 G. Spectra in the left panel are replotted on a ×10 intensity scale on the right, showing the low-spin signal region.

The g values for the remaining two low-spin signals fall into class B of the Truth Table (29), which comprises bis-His and bis-imidazole complexes. These data indicate that in solutions of ferric AF-Hbs two distinct hemichromes (referred to as I and II) exist. Hemichrome II (g = 2.9, 2.3/2.2), with a less anisotropic EPR signal and g values close to those of cytochrome b5, is less abundant than hemichrome I (g = 3.2, 2.3/2.2) of HbTb, Hb1Tn, Hb2Tn, and HbGa. A different trend was observed for HbCTn (see below).

The high-spin signal in HbTb, Hb1Tn, Hb2Tn, and HbGa corresponds to that of an aquo-met form. The rhombic distortion of the high-spin signal in HbCTn suggests the formation of unligated, penta-coordinated Fe (III). Such forms have been previously observed in distal histidine mutants of myoglobin (30–31), in peroxidases (32), in a flavo Hb (33), in a giant Hb at acidic pH (34), and in Scapharca inequivalvis Hb (35). While noting that buffer-dependent rhombic distortion of the high-spin signal of the aquo-met form has been observed (30), the current results provide the first spectroscopic indication for an unligated ferric form in a tetrameric Hb. From the comparison of the EPR spectrum of HbCTn with those of the other four AF-Hbs investigated here, it appears that the formation of the unligated penta-coordinated Fe (III) species in HbCTn is associated with a decrease in the population of hemichrome I, with an invariant population of the aquo-met form. In fact, in HbCTn the cytochrome b5-like hemichrome II is more abundant than hemichrome I.

Overall structure of oxidized HbTb

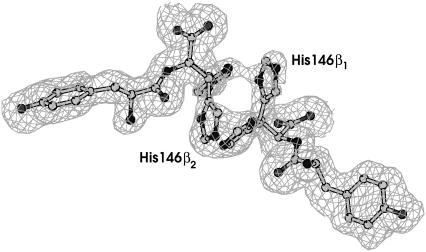

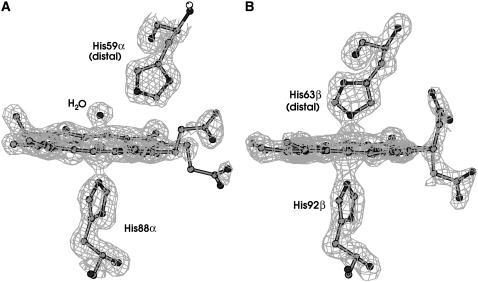

To obtain a detailed characterization of the iron-coordination stereochemistry in hemichromes of AF-Hbs, the structure of the oxidized HbTb (ox-HbTb), previously determined at low resolution (2.5 Å) (5) and shown to contain an α-aquo-met, β-hemichrome structure, was refined using synchrotron data at 1.48 Å (Table 1). The final model, which contains 215 water molecules and seven residues modeled in alternative conformations (Arg-11α, Glu-121α, Ser-29β, Asn-77β, Ser-107β, Ser-139β, His-146β), shows an R-factor value of 0.199 (R-free 0.234) and good quality electron density maps (Figs. 2 and 3).

FIGURE 2.

Electron density map of the β1β2 interface of oxy-HbTb. The alternative conformation of His-146 is apparent in proximity of a special position (twofold axis).

FIGURE 3.

Electron density maps of ox-HbTb: (A) α-heme; (B) β-heme.

The overall structure of ox-HbTb is similar to that previously determined at room temperature and low resolution (5). The root mean-square deviations between the Cα atoms of ox-HbTb and the previously determined structure are as low as 0.63 Å. The quaternary structure is intermediate (H state) between the R and T states. After superimposition of the α1β1 dimer of ox-HbTb to that of the deoxy (T) structure (36), a rotation of 6.7° is required to superimpose the α2β2 dimers. A similar analysis performed between ox-HbTb and the carbomonoxy (R) structure (12) provides an angle of 4.7° in the opposite direction. The other structural features considered diagnostic of an intermediate structure between the T and R states are also conserved. In particular, at the α1β2 interface a water molecule bridges Asp-95α1 and Asp-101β2, with a distance between the Oδ equal to 5.0 Å. In the T state, there is a tight direct Asp-95α1-Asp-101β2 hydrogen bond (2.5 Å) (36), whereas in the R state the two Asp side chains are far apart (6.4 Å) (12). Furthermore, in ox-HbTb the position of Tyr-145β side chain is different from those reported in both the R- and T-states (12,36). In ox-HbTb, Tyr-141α protrudes toward the protein interior and interacts via a water-mediated interaction with the backbone oxygen of Val-35α2.

High resolution of the structure also highlights novel structural details. In particular, the β1β2 interface and some of the residues in the CDβ loop, which are poorly defined in the previously reported structure (5), are well ordered in the current low-temperature high-resolution structure. The β1β2 interface is stabilized by the insertion of Tyr-145β and by a π stacking interaction between the two terminal His-146β1 and His-146β2 (Fig. 2). The inspection of the electron density map of this region reveals that His-146β1 and His-146β2 adopt two alternative conformations (A and B) in proximity to the crystallographic twofold axis. The change in conformation of His-146β is related to the change in the conformation of Ser-139β.

The two symmetry-related side chains of His-146β adopt two different conformations, in such a way that His in the A conformation stacks onto the side chain of His in the B conformation. Interestingly, a similar structural motif has been previously observed in the R2 form of human HbA (37).

Heme regions

The current high-resolution crystal structure allows a more reliable characterization of the heme stereochemistry. The α-heme is in an aquo-met/hydroxy-met state, with the center of the electron density peak 2.0 Å distant from the iron and 4.1 Å from the Nɛ2 atom of His-59α, the distal His (Fig. 3 a). In the β-chains, a bis-His coordination of the irons is observed (Fig. 3 b). The tilt angles between the heme plane and the distal His imidazole plane (θd), the tilt angle between the heme plane and the proximal His imidazole plane (θp), the dihedral angle between the proximal and distal His imidazole planes (ω), and the bond angle between the Fe and the His Nɛ2 atoms (NFeN) were calculated for the β-hemes of ox-HbTb compared with other class B hemichromes of known structure (Table 2). Distortion of the bis-His coordination clearly appears from the analysis of the several stereochemical parameters (see Discussion).

TABLE 2.

Heme stereochemistry (see text) and g values for the bis-His coordinations of Hbs

| Hemoprotein | PDB code | θp (°) | θd (°) | ω(°) | NFeN(°) | g1 | g2 | EPR reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. bernacchii (β subunit)* | 2PEG | 88.5 | 68.8 | 57.7 | 173 | 3.15 | 2.26 | this work |

| T. newnesi (Hb1Tn, β subunit)* | 1LA6 | 76.8 | 73.0 | 62.7 | 165 | 3.13 | 2.24 | this work |

| E. caballus (α subunit)* | 1NS6 | 83.1 | 67.6 | 22.7 | 173 | – | – | – |

| O. sativa† | 1D8U | 87.1 | 88.4 | 64.4 | 178 | – | – | – |

| 87.9 | 87.2 | 63.8 | 177 | |||||

| H. sapiens (cytoglobin)† | 1URV | 83.4 | 82.4 | 67.4 | 171 | 3.20 | 2.08 | (42) |

| 84.3 | 81.3 | 67.4 | 173 | |||||

| H. sapiens (AHSP-α subunit)‡ | 1Z8U | 83.2 | 85.1 | 89.1 | 174 | – | – | – |

| 89.8 | 85.7 | 68.6 | 175 | |||||

| H. sapiens (neuroglobin)‡ | 1OJ6 | 88.4 | 81.8 | 65.5 | 175 | – | – | – |

| 89.3 | 78.1 | 67.3 | 175 | |||||

| 88.5 | 79.1 | 66.1 | 175 | |||||

| 88.8 | 79.4 | 60.9 | 176 | |||||

| Synechocystis s.‡ | 1RTX | 79.0 | 72.7 | 77.0 | 175 | 3.39 | – | (H. C. Lee and J. Peisach, unpublished data) |

| C. arenicola‡ | 1HLB | 89.3 | 77.0 | 65.0 | 177 | – | – | – |

| M. musculus (neuroglobin)‡ | 1Q1F | 89.5 | 79.6 | 61.1 | 177 | 3.12 | 2.15 | (42) |

| D. melanogaster‡ | 2BK9 | 86.9 | 88.5 | 89.0 | 179 | – | – | – |

| Cytochrome b5 | ||||||||

| B. Taurus | 1CYO | 85.9 | 86.3 | 21.2 | 178 | 3.03 | 2.23 | (39) |

| R. norvegicus | 1B5M | 89.1 | 81.3 | 11.8 | 166 | – | – | – |

| H. sapiens (domain of sulfite oxidase) | 1MJ4 | 87.0 | 86.3 | 0.7 | 178 | – | – | – |

Sources of cytochrome b5 are reported for comparative analysis.

tetrameric Hb.

dimeric Hb.

monomeric Hb.

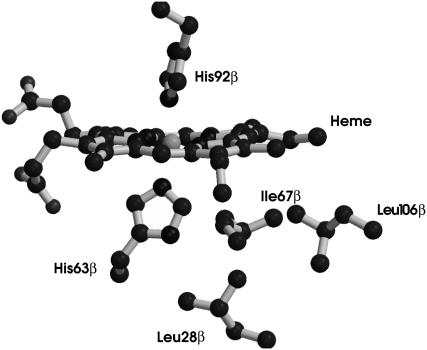

Molecular modeling

To understand the structural basis of the peculiar EPR behavior of HbCTn as compared to the other AF-Hbs, and in particular to the highly sequence-related Hb1Tn, a model of the hemichrome for HbCTn has been built starting from the hemichrome structure of the Hb1Tn previously published (PDB code 1LA6), corresponding to that of the hemichrome I (see below). The main sequence change in the heme pocket region between HbCTn and Hb1Tn is the substitution Val-67β→Ile. In the model of the HbCTn hemichrome, the bulky side chain of Ile-67β makes an unfavorable contact with distal His-63β (Fig. 4) and negatively affects the pathway to hemichrome formation. These considerations might explain the low abundance of hemichrome I in HbCTn.

FIGURE 4.

Modeling of the HbCTn β-heme. The Ile-67β→Val substitution hampers the formation of distorted hemichrome.

Molecular modeling of a cytochrome b5-like (unconstrained) hemichrome, hemichrome II (see below), has been performed, starting from the current structure of the ox-HbTb. The model suggests that formation of hemichrome II in HbTb should require an extensive rearrangement of the β-heme region.

DISCUSSION

The EPR study on five oxidized AF-Hbs reveals that at physiological pH all of them display a variety of ferric forms. The g values for the high-spin signal in HbTb, Hb1Tn, Hb2Tn, and HbGa corresponds to an aquo-met form. One of the three low-spin signals is due to a hydroxy-met form. High-resolution crystallographic data collected on HbTb (this study) and data collected on Hb1Tn (4) clearly indicate that these two signals come from the α-heme, where the aquo-met is in equilibrium with a hydroxy-met form.

The other two distinct low-spin signals suggest the presence of two hemichrome states in the β-subunit characterized by different stereochemical parameters of bis-His coordination (38). In HbTb, Hb1Tn, Hb2Tn, and HbGa, the more abundant form displays gmax and gmid values of 3.2 and 2.3/2.2, respectively, whereas the less abundant hemichrome component exhibits gmax and gmid values of 2.9 and 2.3/2.2, respectively. In HbCTn, which exhibits a distinctive behavior, the relative abundance of the two hemichrome forms is reversed.

In class B hemichromes, g tensor anisotropy is related to state of charge of the imidazole rings and with the geometric parameters of the bis-His coordination (29,38). In this respect it should be noted that the g tensor anisotropy of the two signals observed here (Table 2) does not resemble that of the alkaline form of cytochrome b5 or that of a heme that contains axial imidazolate ligands (39). The geometric parameters that can influence the g tensor anisotropy are the tilt angles of the distal and the proximal imidazole with the heme plane, θd and θp, and the dihedral angle formed between the distal and proximal imidazole groups, ω. Cytochrome b5-like hemichromes and model compounds with unhindered imidazoles display an ideal (least constrained) geometry of coordination—θd and θp close to 90°, and maximal π overlap between the axial imidazole planes and the low-spin Fe (III) dπ orbitals, i.e., ω close to 0° or 90°—deviation from this geometry leads to an increase in the g anisotropy (38). In this framework, the more abundant hemichrome (hemichrome I) in HbTb, Hb1Tn, Hb2Tn, and HbGa can be classified as a distorted bis-His complex, whereas the less abundant one (hemichrome II) is cytochrome b5-like (unconstrained). The high-resolution crystal structure of HbTb herein reported allows an accurate analysis of the heme stereochemistry (Table 2). Our data clearly indicate that the bis-His coordination in the ox-HbTb crystal structure is significantly distorted. Consequently, this x-ray crystal structure can be confidently assigned to hemichrome I detected in solution.

An analysis of heme stereochemistry among Hbs forming a bis-His complex indicates that distorted coordinations are frequent (Table 2). In contrast, the ideal unconstrained geometries are observed only for bis-His complexes of Hbs isolated from Drosophila melanogaster (25) and H. sapiens (α-chain of HbA complexed with AHSP) (11). EPR parameters for several of these bis-His complexes are available and are compared to the geometries obtained from x-ray crystal structures (Table 2). In general, g anisotropy increases with deviation of θd from 90°, i.e., with the increase in the tilt angle of the distal histidyl imidazole (with the exception of human cytoglobin). g anisotropy also increases with increase in deviation from ω = 0° or 90°, the dihedral angle between the proximal and distal histidyl imidazole planes. Thus our results demonstrate that in Hbs, as in model compounds (38), distorted, constrained geometries of bis-His complexes result in an increase in the g tensor anisotropy.

The findings from the molecular modeling of hemichrome II in HbTb suggest that its formation is probably associated to a partial/global unfolding of the protein. To date, it cannot be ruled out that hemichrome II EPR signals come from dissociated monomeric subunits. However, it should be noted that the association constant of the tetramer for AF-Hbs is even higher than for HbA (40). The formation of α-hemichrome in AF-Hbs (as observed in horse Hb (8)) seems unlikely since the key residues responsible for the bis-His coordination in horse Hb are absent in AF-Hbs.

Unlike the other four AF-Hbs, in HbCTn hemichrome II is more abundant than hemichrome I. In addition, a penta-coordinated ferric form can be detected. It is likely that this form almost quantitatively replaces the distorted hemichrome I in the β-chains. A straightforward structural explanation for the peculiar behavior of HbCTn has been hypothesized by molecular modeling. The main difference in the β-heme pocket between HbCTn and the other AF-Hbs is the substitution Val-67β→Ile in HbCTn (41). The replacement of Val-67β with a bulkier side chain generates unfavorable interactions in the heme pocket (Fig. 4). Furthermore, the tight packing of the heme region upon Val-67β→Ile substitution suggests that the mutation may negatively affect the process of hemichrome I.

It is worth mentioning that the main difference between the current structure (ox-HbTb) and the previously low resolution/room temperature structure of HbTb hemichrome (5) is at the β1β2 interface. The β1β2 interface reported herewith is novel in the Hb realm, in that it exhibits π-stacking of the His-146β side chains along a well-ordered Cβ terminal region. Interestingly, this His is involved in the Bohr effect of mammalian Hbs and is also considered relevant for the root effect in HbTb (36).

As a final remark, it is interesting to note that, to our knowledge, up to now no tetrameric Hb in a complete (α and β) hemichrome state has been found. Horse Hb hosts the bis-His adduct at the α subunit within a R quaternary structure (8), whereas HbTb and Hb1Tn (4) host the bis-His adduct at the β subunit within an R/T intermediate quaternary structure. Despite this difference, in horse Hb, HbTb, and Hb1Tn the hemichrome formation requires a similar sliding of the heme toward the exterior of the heme pocket (4,8). The finding that only partial (α or β) hemichrome states have been observed suggests that a complete (α and β) hemichrome state might not be reached within a folded tetramer.

CONCLUSIONS

A number of ferric forms is present in AF-Hbs at physiological pH. In particular, two EPR-distinct hemichromes are observed. It is likely that the two hemichromes represent different stereochemistry of heme coordination. The crystal structure at high resolution of ferric HbTb suggests that the most abundant hemichrome has a distorted geometry, consistent with EPR parameters. Moreover, the crystal structure reveals a low temperature effect, which induces an ordering of the Cβ-terminal regions in a novel β1β2 interface.

EPR spectra of HbCTn reveal that in this protein the distorted hemichrome is less abundant than a cytochrome b5-like unconstrained form and that an unligated penta-coordinated ferric species is present. The different behavior of HbCTn compared to that of the other AF-Hbs is rationalized, taking into account the structural alterations caused by the Val-67β→Ile substitution at the β-heme pocket.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the ELETTRA Synchrotron for providing the synchrotron radiation facilities, and we thank the beamline staff for their assistance during data collection. Giosuè Sorrentino and Maurizio Amendola are acknowledged for their technical assistance.

This work was financially supported by PNRA (Italian National Program for Antarctic Research). It is in the framework of the program Evolution and Biodiversity in the Antarctic (EBA), sponsored by the Scientific Committee for Antarctic Research (SCAR). A.V. acknowledges the University of Naples and the Albert Einstein College of Medicine (AECOM) for travel grants. Work carried out at AECOM was supported by National Institutes of Health grants GM040168 and HL071064-03004 (awarded to J.P.).

Abbreviations used: AF-Hb, Antarctic fish hemoglobin; AHSP, α-helix stabilizing protein; CW, continuous wave; EF helices, residues 57–77 and 85–95; EPR, electron paramagnetic resonance; bis-His, bis-histidyl; Hb, hemoglobin; HbA, adult human hemoglobin; HbGa, Hb of Gymnodraco acuticeps; Hb1Tn, major Hb of Trematomus newnesi; Hb2Tn, minor Hb of Trematomus newnesi; HbCTn, cathodic Hb of Trematomus newnesi; HbTb, Hb of Trematomus bernacchii; NO, nitric oxide; ox-HbTb, the ferric form of HbTb at pH 7.6; PDB, Protein Data Bank.

Editor: Marcia Newcomer.

References

- 1.Shikama, K. 1998. The molecular mechanism of autoxidation for myoglobin and hemoglobin: a venerable puzzle. Chem. Rev. 98:1357–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Riess, J. 2001. Oxygen carriers (“blood substitutes”) raison d'être, chemistry, and some physiology. Chem. Rev. 101:2797–2919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rifkind, J. M., O. Abugo, A. Levy, and J. M. Heim. 1994. Detection, formation, and relevance of hemichrome and hemochrome. Meth. Enzymol. 231:449–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Riccio, A., L. Vitagliano, G. di Prisco, A. Zagari, and L. Mazzarella. 2002. The crystal structure of a tetrameric hemoglobin in a partial hemichrome state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:9801–9806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vitagliano, L., G. Bonomi, A. Riccio, G. di Prisco, G. Smulevich, and L. Mazzarella. 2004. The oxidation process of Antarctic fish hemoglobins. Eur. J. Biochem. 271:1651–1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rachmilewitz, E. A., J. Peisach, and W. E. Blumberg. 1971. Stability of oxyhemoglobin A and its constituent chains and their derivatives. J. Biol. Chem. 246:3356–3366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramadas, N., and J. M. Rifkind. 1999. Molecular dynamics of human methemoglobin: the transmission of conformational information between subunits in an αβ dimer. Biophys. J. 76:1796–1811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robinson, V. L., B. B. Smith, and A. Arnone. 2003. A pH-dependent aquo-met-to-hemichrome transition in crystalline horse methemoglobin. Biochemistry. 42:10113–10125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Sanctis, D., A. Pesce, M. Nardini, M. Bolognesi, A. Bocedi, and P. Ascenzi. 2004. Structure-function relationships in the growing hexa-coordinate hemoglobin sub-family. IUBMB Life. 56:643–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pesce, A., D. De Sanctis, M. Nardini, S. Dewilde, L. Moens, T. Hankeln, T. Burmester, P. Ascenzi, and M. Bolognesi. 2004. Reversible hexa- to penta-coordination of the heme Fe atom modulates ligand binding properties of neuroglobin and cytoglobin. IUBMB Life. 56:657–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feng, L., S. Zhou, L. Gu, D. Gell, J. Mackay, M. Weiss, A. Gow, and Y. Shi. 2005. Structure of oxidized α-haemoglobin bound to AHSP reveals a protective mechanism for haem. Nature. 435:697–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Camardella, L., C. Caruso, R. D'Avino, G. di Prisco, B. Rutigliano, M. Tamburrini, G. Fermi, and M. F. Perutz. 1992. Hemoglobin of the Antarctic fish Pagothenia bernacchii. Amino acid sequence, oxygen equilibria and crystal structure of its carbonmonoxy derivative. J. Mol. Biol. 224:449–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D'Avino, R., C. Caruso, M. Tamburrini, M. Romano, B. Rutigliano, P. Polverino de Laureto, L. Camardella, V. Carratore, and G. di Prisco. 1994. Molecular characterization of the functionally distinct hemoglobins of the Antarctic fish Trematomus newnesi. J. Biol. Chem. 269:9675–9681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tamburini, M., A. Brancaccio, R. Ippoliti, and G. di Prisco. 1992. The amino acid sequence and oxygen-binding properties of the single hemoglobin of the cold-adapted Antarctic teleost Gymnodraco acuticeps. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 292:295–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Otwinowski, Z., and W. Minor. 1997. Processing of x-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Meth. Enzymol. 276:307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brunger, A. T., P. D. Adams, G. M. Clore, W. L. DeLano, P. Gros, R. W. Grosse-Kunstleve, J. S. Jiang, J. Kuszewski, M. Nilges, N. S. Pannu, R. J. Read, L. M. Rice, T. Simonson, and G. L. Warren. 1998. Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 54:905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones, T. A., J. Y. Zou, S. W. Cowan, and M. Kjedgaard. 1991. Improved methods for binding protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. D. 56:714–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berman, H. M., J. Westbrook, Z. Feng, G. Gilliland, T. N. Bhat, H. Weissig, I. N. Shindyalov, and P. E. Bourne. 2000. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 28:235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell, D. T., G. B. Kitto, and M. L. Hackert. 1995. Structural analysis of monomeric hemichrome and dimeric cyanomet hemoglobins from Caudina arenicola. J. Mol. Biol. 251:421–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hargrove, M. S., E. A. Brucker, B. Stec, G. Sarath, R. Arredondo-Peter, R. V. Klucas, J. S. Olson, and G. N. Phillips. 2000. Crystal structure of a nonsymbiotic plant hemoglobin. Structure. 8:1005–1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pesce, A., S. Dewilde, M. Nardini, L. Moens, P. Ascenzi, T. Hankeln, T. Burmester, and M. Bolognesi. 2003. Human brain neuroglobin structure reveals a distinct mode of controlling oxygen affinity. Structure. 11:1087–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoy, J. A., S. Kundu, J. T. Trent, S. Ramaswamy, and M. S. Hargrove. 2004. The crystal structure of Synechocystis hemoglobin with a covalent heme linkage. J. Biol. Chem. 279:16535–16542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vallone, B., K. Nienhaus, K. Matthes, M. Brunori, and G. Nienhaus. 2004. The structure of murine neuroglobin: novel pathways for ligand migration and binding. Proteins: Struct. Func. Bioinf. 56:85–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Sanctis, D., S. Dewilde, A. Pesce, L. Moens, P. Ascenzi, T. Hankeln, T. Burmester, and M. Bolognesi. 2004. Crystal structure of cytoglobin: the fourth globin type discovered in man displays heme hexa-coordination. J. Mol. Biol. 336:917–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Sanctis, D., S. Dewilde, C. Vonrhein, A. Pesce, L. Moens, P. Ascenzi, T. Hankeln, T. Burmester, M. Ponassi, M. Nardini, and M. Bolognesi. 2005. Bishistidyl heme hexacoordination, a key structural property in Drosophila melanogaster hemoglobin. J. Biol. Chem. 280:27222–27229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4. 1994. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 1:760–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaric, S., D. Popovic, and E. Knapp. 2001. Factors determining the orientation of axially coordinated imidazoles in heme proteins. Biochemistry. 40:7914–7928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peisach, J., W. E. Blumberg, S. Ogawa, E. A. Rachmilewitz, and R. Oltzik. 1971. The effects of protein conformation on the heme symmetry in high spin ferric heme proteins as studied by electron paramagnetic resonance. J. Biol. Chem. 246:3342–3355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blumberg, W. E., and J. Peisach. 1972. Low-spin ferric forms of hemoglobin and other heme proteins. Wenner-Gren Center International Symposium Series 18:219–225. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ikeda-Saito, M., H. Hori, L. A. Andersson, R. C. Prince, I. J. Pickering, G. N. George, C. R. Sanders, R. S. Lutz, E. J. McKelvey, and R. Mattera. 1992. Coordination structure of the ferric heme iron in engineered distal histidine myoglobin mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 267:22843–22852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Quillin, M., R. Arduini, J. Olson, and G. J. Phillips. 1993. High-resolution crystal structures of distal histidine mutants of sperm whale myoglobin. J. Mol. Biol. 234:140–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smulevich, G., A. Feis, and B. D. Howes. 2005. Fifteen years of Raman spectroscopy of engineered heme containing peroxidases: what have we learned? Acc. Chem. Res. 38:433–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ilari, A., A. Bonamore, A. Farina, K. Johnson, and A. Boffi. 2002. The x-ray structure of ferric Escherichia coli flavohemoglobin reveals an unexpected geometry of the distal heme pocket. J. Biol. Chem. 26:23725–23732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marmo Moreira, L., A. Lima Poli, A. J. Costa-Filho, and H. Imasato. 2006. Pentacoordinate and hexacoordinate ferric hemes in acid medium: EPR, UV-Vis and CD studies of the giant extracellular hemoglobin of Glossoscolex paulistus. Biophys. Chem. 124:62–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boffi, A., S. Takahashi, C. Spagnuolo, D. L. Rousseau, and E. Chiancone. 1994. Structural characterization of oxidized dimeric Scapharca inaequivalvis hemoglobin by resonance Raman spectroscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 269:20437–20440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mazzarella, L., A. Vergara, L. Vitagliano, A. Merlino, G. Bonomi, S. Scala, C. Verde, and G. di Prisco. 2006. High resolution crystal structure of deoxy hemoglobin from Trematomus bernacchii at different pH values: the role of histidine residues in modulating the strength of the root effect. Proteins. 65:490–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silva, M. M., P. H. Rogers, and A. Arnone. 1992. A third quaternary structure of human hemoglobin A at 1.7-Å resolution. J. Biol. Chem. 267:17248–17256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Walker, F. A., D. Reis, and V. L. Balke. 1984. Models of the cytochromes b. 5. EPR studies of low-spin iron(III) tetraphenylporphyrins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 106:6888–6898. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bois-Poltoratsky, R., and A. Ehrenberg. 1967. Magnetic and spectrophotometric investigations of cytochrome b5. Eur. J. Biochem. 2:361–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Giangiacomo, L., R. D'Avino, G. di Prisco, and E. Chiancone. 2001. Hemoglobin of the Antarctic fishes Trematomus bernacchii and Trematomus newnesi: structural basis for the increased stability of the liganded tetramer relative to human hemoglobin. Biochemistry. 40:3062–3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mazzarella, L., G. Bonomi, M. C. Lubrano, A. Merlino, A. Vergara, L. Vitagliano, C. Verde, and G. di Prisco. 2006. Minimal structural requirement of root effect: crystal structure of the cathodic hemoglobin isolated from Trematomus newnesi. Proteins. 62:316–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vinck, E., S. Van Doorslaer, S. Dewilde, and L. Moens. 2004. Structural change of the heme pocket due to disulfide bridge formation is significantly larger for neuroglobin than for cytoglobin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126:4516–4517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]