Abstract

Based on the identification of actin as a target protein for the flavonol quercetin, the binding affinities of quercetin and structurally related flavonoids were determined by flavonoid-dependent quenching of tryptophan fluorescence from actin. Irrespective of differences in the hydroxyl pattern, similar Kd values in the 20 μM range were observed for six flavonoids encompassing members of the flavonol, isoflavone, flavanone, and flavane group. The potential biological relevance of the flavonoid/actin interaction in the cytoplasm and the nucleus was addressed using an actin polymerization and a transcription assay, respectively. In contrast to the similar binding affinities, the flavonoids exert distinct and partially opposing biological effects: although flavonols inhibit actin functions, the structurally related flavane epigallocatechin promotes actin activity in both test systems. Infrared spectroscopic evidence reveals flavonoid-specific conformational changes in actin which may mediate the different biological effects. Docking studies provide models of flavonoid binding to the known small molecule-binding sites in actin. Among these, the mostly hydrophobic tetramethylrhodamine-binding site is a prime candidate for flavonoid binding and rationalizes the high efficiency of quenching of the two closely located fluorescent tryptophans. The experimental and theoretical data consistently indicate the importance of hydrophobic, rather than H-bond-mediated, actin-flavonoid interactions. Depending on the rigidity of the flavonoid structures, different functionally relevant conformational changes are evoked through an induced fit.

INTRODUCTION

Flavonoids are secondary plant metabolites that have been widely studied because of their potential health benefits and their ubiquitous appearance in the human diet (1–4). Antiinflammatory properties or cytostatic effects have been reported by several authors, but the molecular mechanisms by which flavonoids interfere with the relevant signal chains have remained elusive (5,6). Several beneficial but also adverse biological effects have been reported: the (anti)estrogenic properties of some flavonoids and the goitrogenic activity of genistein may serve as examples (7). On the molecular level the effects of flavonoids on enzymes, transport, and structural proteins have been studied intensively, and numerous reports give evidence that flavonoids may profoundly affect the cellular physiology (1). However, the obtained effects in vitro have rarely been verified in vivo. As a result, the molecular mechanisms through which flavonoids act in vivo are generally unknown. Apparently, numerous target proteins produce a complex reaction pattern that is difficult to predict. Therefore, a systematic approach is required to identify and analyze the spectrum of relevant target proteins in a given cell type to unravel the intricate interactions between different target proteins and to finally come to a realistic risk assessment concerning the biological activities of flavonoids in the human diet (8).

In a previous study, we exploited flavonoid-induced spectroscopic changes upon protein binding. To our surprise, one of the major identified target proteins in the nuclei of human leukemia cells turned out to be actin (9). Actin is one of the most abundant proteins in human tissues and serves essential functions as cytoskeletal component in muscle and nonmuscle cells. Actin may exist as a monomer (globular actin (G-actin)) in the cell but readily polymerizes to form microfilaments (filamentous actin), rendering actin the major molecular player in the control of cell shape, cell adhesion, and cell motility (10). The complex molecular control mechanism for these and other actin functions requires the interaction with numerous cellular proteins (11,12). The recent discovery that actin also plays an important role in the nucleus and is an essential component of the transcription machinery illustrates the pivotal importance of this protein for major cellular functions (13–16).

With respect to the potential effects of flavonoids on cell physiology, the crucial question raised by these recent findings is whether flavonoids, when bound to actin, interfere with actin functions in the cytoplasm and the nucleus. Such biological effects would necessarily have implications for a risk assessment of flavonoids in food, but they may also open up new therapeutic strategies in pathological processes, for example, the cytoskeleton-dependent invasion of tumor cells into nontumor tissues and the resulting formation of metastasis (17,18). Quantitative analyses of flavonoid binding to soluble proteins have been performed in the past by evaluation of flavonoid-dependent quenching of tryptophan fluorescence (19–24). In this study, we extend this biophysical in vitro approach by correlating fluorescence-based estimates of flavonoid binding affinities to actin with flavonoid structure, actin polymerization rate, transcription efficiency, and the actin conformation as monitored by infrared spectroscopy. Using structurally related flavonols, an isoflavone, flavanone, and flavane, we addressed the question of hydroxylation patterns or ring structures being essential determinants of binding specificity and biological efficiency. In combination with molecular docking, the data strongly indicate the prevalence of hydrophobic interactions between the flavonoids and, most likely, the tetramethylrhodamine-binding site of actin. We propose that the rigidity of the flavonoid ring structures is one of the factors that affect conformational transitions in actin by an induced fit mechanism, thereby leading to inhibitory or stimulatory effects on actin functions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Actin preparation for spectroscopy

G-Actin was prepared from rabbit skeletal muscle acetone powder as described elsewhere (25,26) and was stored in the presence of calcium and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) as stabilizing agents in its monomer form in a modified G-buffer system (0.2 mM CaCl2, 0.2 mM ATP, 0.2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.01% NaN3, 2 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.0).

Fluorescence and absorption spectroscopy

Fluorescence spectroscopy was carried out at 1 μM actin concentration in modified G-buffer (0.2 mM CaCl2, 0.2 mM ATP, 0.2 mM DTT, 2 mM Tris-HCl at pH 8.0) using a Jasco FP 6300 spectrofluorometer (Jasco, Gross-Umstadt, Germany) at Ex 295/Em 345 nm with 5 nm bandwidth each. A total of 1 mM flavonoid stock solutions in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to the protein solution to obtain the respective flavonoid concentration. All measurements were performed at 25°C with continuous agitation within the cuvette if not indicated otherwise.

Affinities of flavonoids to actin where assessed by quenching of intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence of actin by bound flavonoids. Stern-Volmer (SV) plots of F0/F versus total concentration of flavonoids [Q] deviated from the ideal linear behavior according to the SV equation:

|

(1) |

which assumes complete quenching, where F0 and F is the actin fluorescence in the absence and presence of quencher, respectively. The observed upward curvature is mainly due to partial absorption of the excitation and emission light by the flavonoids. Therefore, the plots were evaluated according to the equation

|

(2) |

Kd is the dissociation constant of flavonoid actin binding, [Q] is the concentration of the unbound flavonoid (calculated from [Q0] and Kd according to the law of mass action). Attenuation of the excitation and emission light due to absorption by flavonoids within the cuvette is accounted for by the absorption coefficients ax and ae of the flavonoids at the excitation and emission wavelengths, respectively. An effective path length de < 1 cm, determined by the cuvette geometry, accounts for the fact that the emitted light does not traverse the entire cuvette but can originate at any point in the excited volume. Kd, de, and q (the residual tryptophan emission q in the actin-flavonoid complex relative to free actin) were fitted to the experimentally obtained SV plot using ORIGIN software with a single de value of 0.57 cm for all experiments.

Residual tryptophan emission q of the actin-flavonoid complexes was <0.15, i.e., all flavonoids (except epigallocatechin, which did not show strong quenching) abolished >85% of the tryptophan fluorescence when bound to actin. Expanding the nominator and denominator by the addition of quadratic or cubic dependencies on [Q] allows us to further take into account multiple “nonspecific” flavonoid binding to actin at high (>10 mM) concentrations. This does improve the fits of the SV plots but has little influence on the relative Kd values among the flavonoids which are of interest here, rather than absolute Kd values. Absorption spectra of flavonoids were determined at 10 μM concentration with a Jasco V-550 spectrophotometer at 2 nm bandwidth. The molar absorption coefficients (M−1cm−1) of the flavonoids at the excitation and emission wavelength, ax and ae, respectively, as used in Eq. 2 are 14,900, 12,200 (quercetin); 17,700, 10,100 (kaempferol); 11,900, 13,500 (fisetin); 11,900, 11,100 (genistein); 17,800, 16,400 (taxifolin); and 7600, 6200 (epigallocatechin). All flavonoids, buffer constituents, and solvents were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

FTIR

Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were recorded with a vector 22 FTIR spectrometer (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) equipped with a temperature-controlled attenuated total reflectance (ATR) cell (Bio-ATR-II, Bruker). The actin concentration was 4.5 mg/ml in 5× modified buffer G (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM ATP, 1 mM DTT). For one spectrum, 256 interferograms were recorded with a resolution of 2 cm−1. Effects of flavonols on the conformation of actin were analyzed by fitting the amide I bands of free and flavonol-bound actin by Gaussian/Lorentzian curves. Bandwidths were restricted to <25 cm−1. Band frequencies, shapes, and intensities were free to vary in the final fit using Peakfit software 4.12 (SeaSolve, San Jose, CA) until a stable result was obtained.

Polymerization assay

Skeletal muscle actin was purified from acetone powder prepared from rabbit psoas muscle as described (25) and taken up in G-buffer (5 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 0.1 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM NaN3, 0.2 mM ATP). Pyrene-labeled actin (pyrenyl-actin) was prepared according to Koujama and Mihashi (27). The time-dependent increase in the fluorescence during polymerization of 10 μM G-actin mixed with 5% pyrenylactin initiated by the addition of 2 μM MgCl2 was followed using a Shimadzu (Columbia, MD) RF 5001 PC spectrofluorometer with excitation and emission wavelengths set at 365 nm and 388 nm, respectively. Flavonoids quench actin intrinsic fluorescence, and we also observed quenching of pyrene-fluorescence of pyrene-labeled monomeric actin by flavonoids used in this study. Therefore, we normalized the increase in pyrene fluorescence during polymerization to the initially observed fluorescence to correct for the induced quenching.

To perform the assay, different flavonoids were incubated with 10 μM G-actin mixed with 5% pyrenylactin; the polymerization was initiated by the addition of 2 μM MgCl2 and followed over a period of 30 min. We analyzed the slope in the initial linear part of the pyrene fluorescence increase to compare the effects of flavonoids on actin polymerization.

Transcription assay

Transcription was carried out using the HeLaScribe nuclear extract in vitro transcription system (Promega, Madison, WI) following the manufacturer's instructions and utilizing [α-32P]rGTP (3000Ci/mmol) (Amersham Biosciences, Freiburg, Germany) and supercoiled plasmid pEGFP-C1 (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) as template. The RNA isolation was carried out using TriFast (Peqlab, Erlangen, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. During RNA isolation most of the radioactivity was discarded with the RNA supernatant, indicating that no substrate-limiting conditions were reached during the assay. Isolated RNA was dissolved in 200 μl RNase free water and was transferred in scintillation tubes. To each probe 10 ml Ultima Gold XR liquid scintillation cocktail (Packard, Gronningen, The Netherlands) was added. Radioactivity was determined using a Beckmann Coulter (Fullerton, CA) LS 6000 liquid scintillation counter.

Molecular modeling

Docking was performed in the known actin binding sites for low molecular weight ligands. Visual inspection identified no further binding sites close to the most relevant fluorescing tryptophan residues (W-340 and W-356; see Doyle et al. (28)) and deep enough to lead to specific binding at micromolar affinity: the ATP-binding site, e.g. (Protein Data Bank (PDB) code 1YXQ, (29)), the latrunculin-binding site (2A5X, (30)), and the reidispongiolide-binding site (2ASM, (31)). An additional binding site is observed in the structure 1J6Z, where actin is covalently modified at the C-terminus by coupling of tetramethylrhodamine (32). The last two residues are not resolved, indicating significant flexibility of the linker to tetramethylrhodamine, which lies in a pocket that is usually occupied by Y-133, whereas in this structure, Y-133 closes the lid over tetramethylrhodamine.

For docking, any existing ligands as well as solvent molecules were removed and the magnesium ion in the ATP binding site was retained. The flavonoids were modeled in the protonation states shown in Fig. 1. Protein side-chain protonation corresponded to pH 7 using standard pK values. Nonpolar hydrogens were not modeled explicitly. The actual docking takes place with a new version of our docking software (33), which is now based on a Monte Carlo procedure with local minimization (MCM) as described (34,35). The docking approach has been validated on benchmark sets from the literature (36). The docking protocol consists of 15 single docking runs each consisting of 700 MCM steps, with 100 steps of steepest descent gradient minimization at each MCM step. One run took on average 20 min. The fitness function for the optimization is a continuous-gradient approximation to the docking version of ChemScore (37,38).

FIGURE 1.

Structures of flavonoids used in this study. (A) Flavonoid generic molecular formula. (B) Chemical structures of flavonoids used in this study. The flavonols kaempferol, quercetin, and fisetin show a different hydroxyl group substitution pattern and they share the positions 3, 7, 4′ (boxed). The isoflavone genistein, the flavane epigallocatechin, and the flavanone taxifolin represent common flavonoids from other subclasses.

RESULTS

Intrinsic tryptophan-dependent fluorescence of actin is quenched by flavonoids

Tryptophan can be specifically excited at 295 nm. Therefore, intrinsic protein fluorescence when excited at 295 nm can be considered as tryptophan dependent and the quenching of this fluorescence is an indicator for changes in the environment of the tryptophan residues (39). In the case of actin it has been shown that only two out of four tryptophan residues are fluorescent, whereas the other two are internally quenched by sulfur-containing amino acids (28,40). Doyle et al. (28) reported that the fluorescent tryptophan residues W-340 and W-356 possess nearly the same emission spectrum and contribute nearly 90% of the total tryptophan-dependent fluorescence of actin. The possible preference of a quencher to interact with either W-340 or W-356 will thus not be reflected in spectral changes. Hence, a site-specific assignment of the quencher sensitivity is prevented.

We observed quenching of tryptophan-dependent actin fluorescence for all structurally related flavonoids used in this study (see Fig. 1 A for the flavonoid generic molecular formula and Fig. 1 B for the flavonoids used in this study). However, there were differences in the apparent quenching efficiency (Fig. 2 A). Taxifolin appeared to quench fluorescence most efficiently, whereas the flavonols quercetin, fisetin, and kaempferol showed very similar concentration-dependent attenuation of tryptophan emission. The isoflavone genistein also exhibited quenching but was less efficient than taxifolin and the flavonols, and epigallocatechin showed the weakest effect on actin fluorescence. With the exception of epigallocatechin, the quenching saturated in the 0–100 μM concentration range (Fig. 2 A), indicating complete occupancy of the flavonoid-binding site on actin. In a first approximation, the ligand concentrations at which half of the flavonoid-binding sites were occupied (EC50) will thus correspond to 50% of the maximally observed reduction of tryptophan emission providing a reasonable estimate of the respective dissociation constants Kd as given in Table 1. We found that the addition of DMSO, used as a solvent for the flavonoids, induces a slight increase in the measured emission intensity of actin fluorescence (Fig. 2 A) without changing the emission spectra (data not shown). As we were interested in the relative rather than absolute quenching efficiencies of the flavonoids (all prepared from an identical DMSO stock solution), no further corrections were made to account for this effect.

FIGURE 2.

Effect of spectral properties of flavonoids on the intensity of tryptophan emission. (A) Quenching effect of flavonoids used in this study (Ex295 nm/Em345 nm). (B) Actin emission spectra (Ex295 nm) in the presence of rising quercetin concentration. (C) Actin emission spectra (Ex295 nm) in the presence of rising taxifolin concentration. (D) Flavonoids used in this study show an overlap in their absorption spectrum with the actin emission spectrum (Ex295 nm).

TABLE 1.

Dissociation constants of flavonoids binding to actin and quantitation of the effects on polymerization and transcription

| Flavonoid | Subclass | OH-groups (position) | Actin polymerization ± SD [% control] | Transcription activity ± SD [% control] | Kd [μM] from EC50 ± SE | Kd [μM] from SV norm. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quercetin | Flavonol | (3, 5, 7, 3′, 4′) | 63,5 ± 5,3* | 35,0 ± 5,7* | 13,5 ± 3,5 | 21.7 | 1.0 |

| Kaempferol | Flavonol | (3, 5, 7, 4′) | 54,4 ± 2,6* | 42,0 ± 27,0* | 14,4 ± 2,7 | 26.3 | 1.2 |

| Fisetin | Flavonol | (3, 7, 3′, 4′) | 53,8 ± 3,3* | 32,4 ± 22,2* | 14,9 ± 2,6 | 21.3 | 1.0 |

| Genistein | Isoflavone | (5, 7, 4′) | 81,5 ± 21,1 | 54,0 ± 17,3 | 17,6 ± 2,1 | 28.6 | 1.3 |

| Taxifolin | Flavanone | (3, 5, 7, 4′, 5′) | 78,4 ± 32,7 | n.d. | 11,1 ± 3,5 | 22.7 | 1.0 |

| Epigallocat | Flavane | (3, 5, 7, 3′, 4′, 5′) | 145,9 ± 27,1* | 120,6 ± 2,6* | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. |

Polymerization rates and transcription efficiencies are given as percentage of the control measured at the maximal concentration of 25 μM for each flavonoid, i.e., close to the EC50 (numbers and standard deviation as in the corresponding columns in Fig. 4). However, the significance of an inhibitory or activating action of a flavonoid in either assay (marked by an asterisk) is based on the average of the effects measured in duplicate at all the concentrations listed in Fig. 4 (see also Discussion). Therefore, the distinction between inhibitory or stimulatory effects is “stringent”, as it is based on an average concentration clearly below the EC50 for each flavonoid. The asterisk labels experiments where the deviation from the control exceeded the experimental error in the mean rate obtained from all the six independent measurements. Kd values were determined from EC50 according to Fig. 2 A or from SV plots according to Fig. 3 B and Eq. 2 (Materials and Methods). norm, SV-derived Kd values normalized to the Kd of quercetin.

We analyzed the band shape of the actin emission spectra with increasing quencher concentrations. In all cases, except that of taxifolin, the emission intensity decreased with increasing quencher concentrations without causing spectral changes in the actin emission, as exemplified for quercetin (Fig. 2 B). In contrast, quenching of actin fluorescence by taxifolin was accompanied by a shift of the emission maximum from 328 nm to longer wavelength depending on the quencher concentration (Fig. 2 C). We ascribe the concentration-dependent spectral change of the actin tryptophan fluorescence to reabsorption of the emitted light by the quencher. This will lead to a red shift of the apparent emission from actin when the quencher absorbs at shorter wavelengths than the peak emission and the effect will increase with increasing molar extinction of the quencher. Thus, taxifolin is expected to exhibit this effect most prominently among the flavonoids as obvious from the absorption spectra (Fig. 2 D).

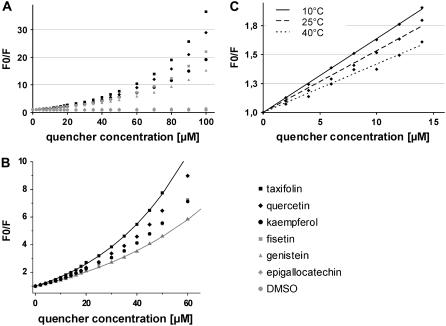

The quenching data were further analyzed according to the SV equation (Eq. 1, Materials and Methods) F0/F = 1 + Ksv×[Q], where F0 is the initially observed fluorescence at (Ex 295 nm/Em 345 nm) in the absence of quencher, F is the fluorescence observed in the presence of the respective quencher concentration [Q], and Ksv is the SV quenching constant. The SV plots are essentially linear for quencher concentrations up to 15 μM and yield Kd values (i.e., the reciprocal slopes of the linear part assuming static quenching, Eq. 1) in good agreement with those derived from the EC50 (Fig. 3 A). However, the plots show an upward curvature which is expected when excitation and emission light become attenuated with increasing quencher concentration, leading to an overestimation of the actual quenching efficiency and, correspondingly, of the affinity of the flavonoids for actin. The degree of the upward curvature depends on the absorption properties of the respective flavonoids. Additionally, “nonspecific” flavonoid binding is likely to occur at higher concentrations, causing nonlinear terms in the concentration dependence of the SV plot which will also cause an upward curvature. We took these effects into account (Eq. 2, Materials and Methods) and find that the deviation from linearity between 0–30 μM strongly depends on the spectral properties of the flavonoids, whereas above 30 μM the quadratic and cubic concentration dependence associated with the possible binding of multiple flavonoids per actin becomes predominant.

FIGURE 3.

Actin tryptophan-dependent fluorescence is quenched by flavonoids. (A) SV analysis of the quenching data according to Eq. 1 (see Materials and Methods). (B) Analysis of the SV plots according to Eq. 2 (see Materials and Methods) can explain the upward curvature of the plots as exemplified here for taxifolin (solid black line) and genistein (solid gray line). The corresponding Kd values are displayed in Table 2. (C) SV analysis on the temperature dependence of quercetin quenching according to Eq. 1.

The solid lines drawn through the SV plot of taxifolin and genistein (Fig. 3 B) exemplify the explicit consideration of these effects which obviously can fully account for the curvatures. The fits deviate from the data within experimental error and the accuracy is mainly due to the incorporation of the flavonoids' absorption properties in the SV equation. As expected, slightly higher Kd values in the 20–30 μM range are obtained for single site occupancy for all flavonoids compared to the estimates based on 50% quenching efficiency. Kd values for multiple binding site occupancy for all flavonoids are predicted in the 10–100 mM range to account for the curvatures above 30 μM. The purpose of these experiments, however, was to rank the different flavonoids according to their relative affinities to actin at μM concentrations, rather than to determine absolute Kd values, including those for low affinity binding sites. We normalized the dissociation constants of the flavonoids relative to that of quercetin (Table 1 columns 7 and 8). The ranking based on the fits deviates from that obtained with the EC50 values mainly in the case of taxifolin. This is fully explained by the large absorption of taxifolin at 295 (ax = 17,800 cm−1M−1) and 345 nm (ae = 16,400 cm−1M−1), thus being the most efficient absorber of excitation and emission light among the studied flavonoids, leading to overestimation of its affinity based on EC50 determination. The fit reveals that taxifolin binds with essentially the same affinity to actin as quercetin. Similarly, the affinity of kaempferol for actin is smaller, when spectral properties are taken into account, mainly because of its larger absorption of the excitation light (ax = 17,700 cm−1M−1), which attenuates the excitation of tryptophan.

Finally, we assessed the nature of the quenching process. In the case of static quenching a non- or weakly fluorescent complex between protein and the quencher is formed and the SV quenching constant Ksv (Eq. 1, Materials and Methods) will decrease with increasing temperature, because the stability of the complex decreases with temperature. This temperature dependence of the SV plot was indeed observed as exemplified for quercetin in the range of 10–40°C (Fig. 3 C), strongly supporting the formation of a flavonoid actin complex rather than the existence of collisional quenching, which would increase with temperature. The data argue for a defined flavonoid binding-site in actin, which allows efficient quenching of tryptophan emission. When fluorophore and quencher are in proximity in the actin-flavonoid complex, Förster-type resonance energy transfer can occur (39). The prerequisite for this type of quenching mechanism is an overlap of the actin emission spectrum with the flavonoids' absorption spectra. This is the case for all studied flavonoids except for epigallocatechin, which shows little absorption in the spectral range of actin emission and is also the least effective quencher (Fig. 2 D).

In summary, the data suggest that the flavonoids form stable complexes with actin, in which tryptophan emission is quenched by a Förster-type mechanism through energy transfer to the bound flavonoid. This is similar to previous reports on flavonoid-dependent quenching of tryptophan emission in human and bovine serum albumin (HSA/BSA, (19–24)) showing that hydrophobic and ionic interactions are involved in protein/flavonoid complex formation with binding constants in the typical range (104–106 M−1) for small molecular weight ligands of HSA/BSA (41). In contrast, actin fluorescence is almost unaffected when the flavonoid does not absorb in the 300–360 nm range, as in the case of epigallocatechin, which nevertheless binds to actin (see below). It is known that the quenching of intrinsic protein fluorescence depends on structural properties of flavonoids (21,41). We have shown here that flavonoids from different subgroups, when corrected for their different absorption properties, show similar quenching efficiencies (<15% residual tryptophan fluorescence in the actin-flavonoid complex) and exhibit Kd values that differ only by 10–30% within and between subclasses and are thus largely independent of the specific hydroxyl group substitution pattern (see Fig. 1 B for flavonoid structures).

Influence of flavonoids on in vitro transcription and actin polymerization

We studied whether the molecular interaction between actin and flavonoid, evidenced by fluorescence spectroscopy, affects important actin functions. The influence of the different flavonoids on actin polymerization was investigated using a pyrenyl-actin-based fluorescence assay that has been developed for actin depolymerization factor (ADF)/cofilin- and gelsolin-dependent actin polymerization studies. Fig. 4 A illustrates the trends in different inhibitory activities of the tested flavonoids on actin polymerization. The flavonols kaempferol and fisetin strongly reduced actin polymerization in a dose-dependent manner and with similar efficiencies corresponding to an EC50 of ∼25 μM, whereas quercetin showed the weakest inhibition among the flavonols but tends to be a stronger inhibitor than the other compounds tested. Genistein and taxifolin also appear to be inhibitory at 25 μM, but there was almost no effect at lower concentrations. Surprisingly, epigallocatechin stimulated actin polymerization.

FIGURE 4.

Evaluation of flavonoid-dependent actin functions. (A) In vitro polymerization of rabbit skeletal muscle actin in the presence of 5, 10, and 25 μM of the respective flavonoid. (B) In vitro transcription activity of HeLa cell nuclear extract in the presence of different flavonoids (5 and 25 μM). Columns represent the mean value of duplicates or triplicates; error bars indicate the standard deviation.

Recently, it was shown that actin is a crucial component of the transcription machinery (13–15). We asked whether the flavonols, which were inhibitory in the polymerization test, would also affect transcription. Indeed, the flavonols kaempferol, quercetin, and fisetin and the isoflavone genistein inhibited transcription in a concentration-dependent manner, with an IC50 in the range of 20–30 μM. In contrast, transcription was stimulated by epigallocatechin (Fig. 4 B). The trends in inhibitory efficiencies of the different flavonoids follow qualitatively and quantitatively the same order that we found for their effects on actin polymerization. Despite the fact that the transcription process is dependent on many other factors, the functional assays are consistent, with actin being a protein target that may confer the observed flavonoid sensitivity to the transcription process. The statistical significance of the results of both in vitro assays is given in Table 1 (see also Discussion).

Influence of flavonol binding on secondary structure of actin

The biological function of actin is coupled to conformational changes that regulate the transition from the G to the F form of actin regulated by ATP and Ca2+. It is thus of prime interest to assess the impact of flavonoids on the conformational equilibrium and structural stability of actin under most native-like conditions. Using FTIR, we addressed this question for the flavonol quercetin and the flavane epigallocatechin bound to actin in the presence of ATP and Ca2+ for the following reasons. First, these to flavonoids exhibit opposite effects in the actin polymerization assay, suggesting that they induce different protein conformations; second, due to the very small changes exerted by epigallocatechin on the fluorescence properties of actin, the corresponding detection of epigallocatechin binding is less accurate. FTIR spectroscopy, however, may detect flavonoid binding with high sensitivity based on its possible effect on protein secondary structure. The well-established dependence of the peptide carbonyl stretching modes (amide I vibrations) on secondary structure (42–45) was used to monitor corresponding structural changes in actin. Fig. 5 A shows the amide I and amide II (peptide C-N stretching coupled to NH bending) absorption of actin as a function of flavonoid binding.

FIGURE 5.

ATR-FTIR spectra in the amide I and II spectral range of free and flavonoid-bound actin. (A) Actin in the absence of flavonoid. (B) Actin in the presence of 50 μM epigallocatechin. (C) Actin in the presence of 50 μM quercetin. The amide I contour was fitted by Gaussian/Lorentzian bands as described (Materials and Methods) and as summarized in Table 2. Experiments were done at 23 °C, in 5× buffer G.

The frequency range extends to the absorption range of the flavonoids, which exhibit distinct bands at 1406 and 1438 cm−1 superimposed with the broad absorption features of the symmetric carboxylate stretches of Asp and Glu side chains of actin around 1400 cm−1. The amide I band of actin shows a maximum at 1647 cm−1 with an asymmetric broadening to the low-frequency side (1620–1630 cm−1) very similar to published infrared (IR) spectra of actin (46). The amide I contour results from the overlapping contributions of the amide modes of the different secondary structure elements present in actin as determined from the crystal structure (47). The main contribution is found at 1652 cm−1, typical of absorption by buried helices, flanked by bands at 1667 and 1640 cm−1, corresponding to turns and random structure, respectively. The low- and high-frequency sides of the contour are reproduced by fitted bands around 1680 and 1630, typically associated with β-strands. Epigallocatechin does not significantly shift the main peak of the total amide I absorption and has a small effect on the bands that contribute to the amide I contour (Fig. 5 B).

The latter becomes more symmetric by a frequency upshift in the β-strand absorption range and an increase of the 1666 cm−1 component relative to the 1640 cm−1 band not seen with quercetin. In contrast, binding of quercetin causes an upshift of the peak of the amide I contour by 5 cm−1 (Fig. 5 C), indicating that quercetin induces a structural transition in actin. The fitted amide I components show that quercetin enhances the predominant helix-indicating peak at 1652, whereas the absorption in the range of β-strand structure between 1620–1630 is strongly reduced. Irrespective of a detailed assignment to individual types of secondary structure, the data show that both flavonoids bind to actin in the ATP- and Ca2+-bound state and induce distinct and flavonoid-specific structural changes. Epigallocatechin stabilizes a relatively native-like structure (modest changes in the relative amplitudes of underlying bands, small frequency shifts), whereas quercetin populates a state with a composition of more diverse secondary structure features, thereby significantly broadening the amide I contour. Table 2 summarizes the flavonoid-induced IR absorption changes of actin.

TABLE 2.

Frequencies and relative integral intensities of fitted Gaussian/Lorentzian bands in the amide I contour of actin

| Amide I peak positions and amplitudes

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary structure | Actin free cm−1% | Actin epigallocatechin cm−1% | Actin quercetin cm−1% |

| β-Strand | 1626 20 | 1629 14 | 1623 8 |

| Random | 1639 21 | 1640 20 | 1638 22 |

| α-Helices | 1652 28 | 1652 29 | 1652 36 |

| Turns | 1667 20 | 1666 23 | 1666 23 |

| β-strand | 1683 11 | 1682 14 | 1681 11 |

Secondary structures are indicated at frequency ranges that correspond to the most common assignments (referenced in the text). Here, the relative integral intensities are used primarily to qualitatively compare the effects of flavonoids on protein conformation, rather than to deduce specific secondary structural transitions.

Docking studies of the known ligand-binding sites of actin

We performed docking studies to assess the potential of flavonoids to interact at known small molecule-binding sites identified by x-ray crystallography of actin-ligand complexes. In Fig. 6, the four different actin structures used for docking are shown. Although three of the structures superpose quite well, the fourth (1J6Z) corresponds to the so-called adenosine diphosphate (ADP)-binding conformation of actin and shows a number of significant differences. The most important features relevant for this study include the stabilization of the helical structure in the DNAase I binding loop and some significant changes in the studied binding sites: The latrunculin-binding site opens up further, the reidispongiolide site shows significant side-chain movement (not shown), and the tetramethylrhodamine-binding site is formed by the movement of the short helix at the lower right of the picture.

FIGURE 6.

Structural flexibility of actin and binding of low molecular weight ligands. Superimposed are the crystallographically determined structures of actin bound to ADP/tetramethylrhodamine (magenta; PDB ID 1J6Z), ATP/swinholide (white; PDB ID 1YXQ), latrunculin (blue; PDB ID: 2A5X), and reidispongiolide (yellow; PDB ID 2ASM). The original ligands for the studied binding sites are depicted in sticks: ATP (color coded) latrunculin (blue), reidispongiolide (yellow), and tetramethylrhodamine (magenta). The tryptophans responsible for 90% of actin fluorescence, i.e., W-340 (center) and W-356 (lower right corner), are shown in space fill mode. Their closeness to the tetramethylrhodamin-binding site, which we propose to also accommodate the flavonoids, agrees with the strong quenching of tryptophan emission in the flavonoid-bound state. This figure was prepared with Chimera.

The results of a detailed docking analysis for the flavonoids at the three known binding sites for low molecular weight ligands are shown in Table 3. A fourth one, the ATP-binding site, would offer a simple explanation for the inhibitory effect of flavonoids on the polymerization of actin, in that ATP binding could be competitively inhibited by flavonoids, whereas the activating effect of epigallocatechin could in principle be explained by a stabilization of the open conformation of actin. However, epigallocatechin would also compete with ADP/ATP for binding, and it appears improbable that its “agonistic” effect is stronger than that of the original ligand.

TABLE 3.

Features of the low molecular weight ligand-binding sites of actin and the corresponding results for molecular docking of flavonoids

| Binding site | PDB entry | Side-chain flexibility | Average interaction energy | Distance TRP-340/TRP-356 | Docking consistency (proteins) | Docking consistency (ligands) | Biological effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATP | 1YXQ | Low | 28.5 | 8/20 | Moderate | High | ATP/ADP competition |

| Latrunculin | 2ASM | Moderate | 20.5 | 13/24 | Low | Low | Nucleotide exchange |

| Reidispongiolide | 2A5X | High | 22.3 | 15/9 | Low | Moderate | Profilin competition |

| Tetramethyl rhodamine | 1J6Z | High | 25.3 | 13/4 | Induced fit | Moderate | Profilin competition |

Side-chain flexibility in the binding site and docking consistency were evaluated visually by comparison of the different protein structures and corresponding predictions for each of the six flavonoids shown in Fig. 1. Docking consistency with respect to protein structure refers to the similarity of the results for the original structure and the open actin conformation (1J6Z). Docking consistency with respect to ligands refers to the similarity of the ligand poses in the same binding pocket.

The latrunculin-binding site leads to the poorest results. The binding site is relatively open, allowing little specific placements for the different ligands. The obtained binding modes for even very similar flavonoids differ significantly, and the interaction energies are quite poor. The results for the reidispongiolide-binding site are shown in the second row in Fig. 7. The interaction energies are low and the binding site is relatively open, also allowing considerable variability in the poses. Y-169 closes on top of the ligands, forming a lid on the binding site and shielding the more hydrophobic parts from the solvent. The binding site itself is open from two sides and allows a number of similar yet distinct poses for the different ligands. Quercetin forms a π-stacking interaction of imperfect geometry with the Y-169 and two H-bonds to two backbone carbonyls (I-136 and A-170). Furthermore, the side chains in the binding site are quite flexible, as evidenced by the conformational differences in different protein structures. This suggests that the binding site may adapt to the binding of flavonoids. However, it leads to low docking consistency between different protein structures, which may indicate a preferential stabilization of the closed conformation.

FIGURE 7.

Docking poses of quercetin in the different low molecular weight ligand-binding sites of actin. (From top to bottom) Latrunculin-, reidispongiolide-, and tetramethylrhodamine-binding sites. On the left, the original ligand from the PDB structure is shown in thin blue sticks and the docked quercetin in thick colored sticks. In the reidispongiolide-binding site, we omitted the original ligand for clarity. On the right, the predicted poses for the six different ligands are shown to visualize the variability in the docking results. Except for a single H-bond to the backbone carbonyl of F-352, the tetramethylrhodamine-binding site (bottom panels) provides hydrophobic interactions with the quercetin rings, and the hydroxyls of the flavonoid are exposed. Clustering of two binding modes in the tetramethylrhodamine-binding site may be relevant to shifting the actin conformation in a flavonoid structure-dependent manner (see text for details).

The tetramethylrhodamine-binding site is particularly interesting, as it exhibits the highest averaged interaction energy among the non-ATP-binding sites. It is also the most hydrophobic site with three of the “walls” of the pockets formed by aromatic residues, two of which (F-352 and Y-133) stack against the aromatic ring systems of the flavonoids when this site opens in an induced fit mechanism. There is only a single and not solvent-exposed H-bond formed with the backbone of F-352. The pocket binds the main hydrophobic parts of the flavonoids, whereas the polar parts are sticking out into the solvent. This is in full agreement with the lack of any clear correlation between the measured binding affinities and the hydroxylation pattern of the flavonoids. There are two main binding modes, as distinguished by the burial of either the A+C ring system or the B ring only. This distinction may potentially explain the different biological effects of the flavonoids. Depending on the flavonoid orientation, interference with protein binding or change of the preferred conformational states of actin may differ. Although all compounds in this study are in principle compatible with both binding modes, our structural model suggests that quercetin, kaempferol, fisetin, and taxifolin prefer the binding mode with only the B ring buried, whereas genistein and especially epigallocatechin preferentially bind with the A and C ring at the bottom of the tetramethylrhodamin-binding site.

DISCUSSION

The influence of flavonoids on cell physiology is intensively studied, but their impact on human health is nevertheless discussed controversially. This is mainly due to a lack of knowledge of the molecular interactions between specific flavonoids and corresponding cellular target proteins. In an attempt to identify unknown nuclear target proteins of the flavonol quercetin, we showed recently by fluorescence spectroscopy followed by mass spectroscopy that actin is one of several nuclear target proteins of this ubiquitous flavonoid (9). In addition to its function as a major component of the cytoskeleton, actin has been shown to also be involved in transcription (13–16). These recent discoveries have prompted us to investigate the potential impact of dietary abundant flavonoids on actin functions in the cytosol and in the nucleus. Therefore, we studied the molecular interaction between actin and a number of structurally related flavonoids to correlate in a systematic manner structural properties with binding affinities and biological effects. Following the experimental strategy of the pioneering work on the interactions of flavonoids with albumin (20–24,41), binding affinities were assessed by tryptophan fluorescence quenching. We extended our studies to the infrared-spectroscopic quantitation of actin secondary structure, assays of actin functions, and molecular docking. The obtained data reveal a consistent picture of an allosteric regulation of actin by specific flavonoids.

In contrast to our expectation, the Kd values for binding to actin as derived from tryptophan fluorescence quenching are essentially independent of the hydroxyl group substitution patterns in the different flavonoids. For example, the Kd of the flavonols appears to be not dependent on the 5 hydroxyl group in ring A: fisetin lacks this group but, nevertheless, binds to actin with the same affinity as quercetin. This is further supported by the unaltered affinity of the flavanone taxifolin, which exhibits an out-of-plane position of the 3 hydroxyl group in ring C as opposed to the in-plane orientation in the flavonols. If removal occurs at all, the removal of one of the two hydroxyls in the B ring may slightly reduce the affinity, as seen with kaempferol. However, the 10–20% shift in the Kd corresponds to <1 kJ difference in the ΔG0, suggesting that H-bonding is of almost negligible importance for the stabilization of the actin-flavonoid complexes.

The planarity of the C and (through conjugation) partial coplanarity with the B ring also do not appear to be a prerequisite for binding the flavonols to actin because the nonplanar but otherwise flavonol-like structure of taxifolin is also compatible with a quercetin-like affinity to actin. Rather than planarity, the location of the B ring seems to affect the affinity to actin, as the flavonol is favored over the isoflavone structure of genistein. The data suggest that hydrophobic interactions are far more relevant to actin binding than strict steric requirements and polar interactions at the flavonoid actin interface. Likewise, the lack of the 4 carbonyl function in epigallocatechin does not appear to abolish actin binding, as is evident from the effect of this flavonoid on actin structure, revealed by FTIR spectroscopy (Fig. 5 and Table 2). The lack of π-electron delocalization in this compound, however, renders a fluorescent-based Kd determination impossible, because the ultraviolet absorption is shifted below 300 nm, where epigallocatechin cannot act as an energy acceptor for the excited state of tryptophan.

Although based on actin from rabbit skeletal muscle, we expect the hydrophobicity-driven binding of flavonoids to hold also for actin from other species, since the amino acid sequences of vertebrate actins are highly conserved. This holds especially for the region of the tryptophan residues responsible for the intrinsic fluorescence (48). It is obvious that the binding affinities for actin fall in the 20 μM range, irrespective of the structural variations among the tested flavonoids. Correspondingly, the observed inhibitory effects on polymerization cannot be related to differences in binding affinities. Instead, they are expected to directly reflect the functional state of the respective actin-flavonoid complex. This fully agrees with the fact that also in the polymerization assays the EC50 values are close to 25 μM for the most potent inhibitors kaempferol, quercetin, and fisetin (Table 1), where experimental errors are small enough to allow measuring the concentration dependence of the inhibitory effect (Fig. 4 A). This result supports the interpretation that binding to the same site that is detected by fluorescence quenching is also responsible for the observed biological effects. For the weaker inhibitors taxifolin, genistein, and the “activator” epigallocatechin, the experimental error at high flavonoid concentration is too large to clearly resolve the dose dependency.

A trend of increasing inhibition and stimulation can, nevertheless, be discerned from the bar graph for genistein and epigallocatechin, respectively. Although binding affinity is little affected by the different flavonoid structures, the data reveal that the effect on actin function is structure dependent. Statistically significant inhibition of polymerization is found for kaempferol (70% ± 6%), quercetin (82% ± 3%), and fisetin (69% ± 3%). Here, the averaged polymerization rate (relative to the control) of the six independent measurements for each compound (two experiments per column in Fig. 4) obtained at the three concentrations is given in brackets. Upon averaging over the different flavonoid concentrations, all information on the concentration dependence, such as the EC50, is lost. Importantly, however, for the thus obtained averaged inhibition the mean error inherent to the individual experiments on kaempferol, quercetin, and fisetin is reduced from ±15%, ±7%, and ±7% to the indicated values, respectively. Although genistein and taxifolin also show a trend to slightly inhibit actin polymerization, the data do not reveal a statistically significant inhibitory action.

The flavonols are clearly more potent inhibitors of polymerization than genistein and taxifolin, underscoring the importance of B-ring position and C-ring planarity, respectively. In contrast, epigallocatechin stimulated polymerization in a dose-dependent manner. The averaged increase of the polymerization rate in the six independent experiments in the presence of epigallocatechin is 32% and thus above the uncertainty of ±13% of this mean value. A similar effect has been observed for β-amyloid fibril formation, which is inhibited by flavonols, yet enhanced by catechins (49). These observations lend further support to our conclusion that structural features, rather than the binding affinities, correlate with the observed biological effects of the flavonoids on actin polymerization.

Recently, it has been shown that actin also plays a pivotal role in the nucleus as a component of the transcription machinery (13–16). Therefore, we asked if the selected flavonoids also affect the biological activity of actin with respect to transcription. Also with respect to transcription, the stimulatory effect of epigallocatechin is clearly above the experimental error. This again contrasts with the inhibitory action of the other flavonoids. Kaempferol, fisetin, and genistein exhibit clear trends of a dose-dependent inhibition of transcription very similar to their effect on polymerization. Due to the indicated experimental errors, a statistically significant inhibition of transcription, however, can be stated only for quercetin. Although transcription clearly depends on the function of many proteins, the results of the functional tests and the data obtained by fluorescence quenching strongly suggest that both effects are not due to different affinities but are the result of specific flavonoid/actin interactions which may lead to shifts in the conformational substates of actin.

The conformation of actin is regulated by a large number of factors such as pH, divalent ions, nucleotides, and actin-binding proteins (50–53). The FTIR spectra reveal the conformational sensitivity of biologically functional actin in the presence of ATP and Ca2+ to flavonoid binding. The IR band analysis of actin in the absence of flavonoids indicates helical content (1652 cm−1 absorption assigned to peptide stretches of at least three turns) that is in general agreement with the crystal structure. Quercetin binding causes an increase of helix-like absorption, which in part may be the result of hydrophobic interactions in the flavonol-binding site, which reduces the number of water-exposed helices absorbing at a lower amide I frequency as compared to the 1650–1653 cm−1 absorption of the “canonical” buried helices. In contrast, epigallocatechin binding stabilizes a much more native-like actin conformation, except for the indication of a slightly increased number of peptide bonds in turns. The different behavior from quercetin is obvious. The nature of the IR spectral changes appears to reflect the counteracting effects exerted by the two flavonoids on actin: the polymerization-promoting epigallocatechin exhibits a much smaller influence on the actin structure than the polymerization-inhibitor quercetin.

The FTIR data clearly demonstrate the structural sensitivity of actin to specific flavonoids. It remains to be elucidated, though, how flavonoids can exert an allosteric effect that interferes with actin function in the cytoplasm and the nucleus. We addressed this question by molecular docking studies to obtain a first estimate of the likelihood of flavonoid binding to known small molecule binding sites on actin. It seems reasonable to relate the effect of quercetin (and other inhibitory flavonoids) to the inhibition of ATP binding and/or ATP hydrolysis. However, it is unlikely that, for example, quercetin is able to replace bound ATP/ADP. We are not aware of a direct measurement of actin-ATP affinity, but arp2/3 proteins with a very similar binding pocket have been reported to bind ATP with nanomolar affinity (54) in contrast to the ∼20 μM affinities of the flavonoids demonstrated here. In addition, under the conditions of our experiments, ATP is still in 10-fold excess over the EC50 of the flavonoids, strongly indicating that the flavonoids do not interfere with the ATP-binding site. In light of the spectroscopic data and the docking results, the tetramethylrhodamine-binding site appears to be a prime candidate for flavonoid binding.

In agreement with the similar Kd values for all flavonoids, this site would accommodate different flavonoids equally well (independent of their hydroxyl pattern) through hydrophobic interactions. It may adapt to their structure and rigidity by switching between the two predicted binding modes probably associated with different actin conformations. Furthermore, the surface exposure of the different hydroxyls of the flavonoids bound at this particular site may additionally affect homo- and heterooligomeric interactions of actin. The separation into largely structure-independent affinity-specifying interactions (hydrophobic packing into the site) and flavonoid structure-dependent biological efficiencies evoked by conformational switching and/or exposure of different hydroxyl patterns could be rationalized. The tetramethylrhodamine-binding site also exhibits the shortest average distance to the tryptophans that become quenched in the flavonoid-bound state (Table 3). The bottom of the pocket is formed by the fluorescent W-356, which is even in direct contact with the flavonoids and thus in a favorable position for Förster resonance energy transfer.

CONCLUSION

We have shown that structurally related flavonoids bind to actin and affect its biological functions in a dose- and structure-dependent manner. The flavonols kaempferol, quercetin, and fisetin were found to be inhibitors of actin polymerization and partly of in vitro transcription, whereas epigallocatechin stimulates both actin-dependent processes. Based on the FTIR data, we propose that flavonoids shift the conformational equilibrium of actin toward either a monomeric or a polymerization-promoting state depending on flavonoid structure. This “induced fit” is based on the intrinsic flexibility of actin, which is required for its functional regulation and may explain why structurally different flavonoids exhibit similar affinities to actin yet evoke different functional effects. Only in the functional assays do the different binding modes become apparent, as they correlate with different conformational substates that become stabilized. In agreement with this notion, the more rigid (planar) flavonols will require a steric adjustment mainly on the side of actin, thus interfering more severely with its function. In contrast, the more flexible flavanone and flavane, exhibiting the same basic scaffold, may more readily adopt themselves to the normal actin conformational equilibrium, thereby showing much less influence on actin function.

The actin flexibility may impose limitations on the static docking approach attempted here. However, the properties of the tetramethylrhodamine-binding site agree very well with the demonstrated strongly hydrophobicity-dependent affinity of the flavonoids. Therefore, we suggest that the different flavonoids bind predominantly through hydrophobic contacts to the tetramethylrhodamine-binding site. We hypothesize that the latter adapts to the specific flavonoid ring structure and, thereby, triggers conformational transitions in actin. These and future studies will allow us a deeper view of the interactions of flavonoids with structural proteins. Since it is known that flavonoids can also affect tubulin and myosin functions (55,56), the question arises to which extent flavonoids may affect cytoskeletal functions through different pathways in vivo. Future experiments addressing this question will give valuable information concerning a realistic risk assessment of flavonoids in food and may allow designing flavonoid derivatives with pharmacologically desirable functions.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant Fa248/4-4 to K.F.).

Editor: Jonathan B. Chaires.

References

- 1.Middleton, E., C. Kandaswami, and T. C. Theoharides. 2000. The effects of plant flavonoids on mammalian cells: implications for inflammation, heart disease, and cancer. Pharmacol. Rev. 52:673–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knekt, P., J. Kumpulainen, R. Jarvinen, H. Rissanen, M. Heliovaara, A. Reunanen, T. Hakulinen, and A. Aromaa. 2002. Flavonoid intake and risk of chronic diseases. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 76:560–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manach, C., A. Scalbert, C. Morand, C. Remesy, and L. Jimenez. 2004. Polyphenols: food sources and bioavailability. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 79:727–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nichenametla, S. N., T. G. Taruscio, D. L. Barney, and J. H. Exon. 2006. A review of the effects and mechanisms of polyphenolics in cancer. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 46:161–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen, D., K. G. Daniel, M. S. Chen, D. J. Kuhn, K. R. Landis-Piwowar, and Q. P. Dou. 2005. Dietary flavonoids as proteasome inhibitors and apoptosis inducers in human leukemia cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 69:1421–1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoon, J. H., and S. J. Baek. 2005. Molecular targets of dietary polyphenols with anti-inflammatory properties. Yonsei Med. J. 46:585–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doerge, D. R., and D. M. Sheehan. 2002. Goitrogenic and estrogenic activity of soy isoflavones. Environ. Health Perspect. 110:349–353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mennen, L. I., R. Walker, C. Bennetau-Pelissero, and A. Scalbert. 2005. Risks and safety of polyphenol consumption. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 81:326S–329S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Böhl, M., C. Czupalla, S. V. Tokalov, B. Hoflack, and H. O. Gutzeit. 2005. Identification of actin as quercetin-binding protein: an approach to identify target molecules for specific ligands. Anal. Biochem. 346:295–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pollard, T. D., L. Blanchoin, and R. D. Mullins. 2000. Molecular mechanisms controlling actin filament dynamics in nonmuscle cells. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 29:545–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.dos Remedios, C. G., D. Chhabra, M. Kekic, I. V. Dedova, M. Tsubakihara, D. A. Berry, and N. J. Nosworthy. 2003. Actin binding proteins: regulation of cytoskeletal microfilaments. Physiol. Rev. 83:433–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pollard, T. D., and J. A. Cooper. 1986. Actin and actin-binding proteins. A critical evaluation of mechanisms and functions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 55:987–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu, X., X. Zeng, B. Huang, and S. Hao. 2004. Actin is closely associated with RNA polymerase II and involved in activation of gene transcription. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 321:623–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hofmann, W. A., L. Stojiljkovic, B. Fuchsova, G. M. Vargas, E. Mavrommatis, V. V. Philimonenko, K. Kysela, J. A. Goodrich, J. L. Lessard, T. J. Hope, P. Hozak, and P. de Lanerolle. 2004. Actin is part of pre-initiation complexes and is necessary for transcription by RNA polymerase II. Nat. Cell Biol. 6:1094–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Philimonenko, V. V., J. Zhao, S. Iben, H. Dingova, K. Kysela, M. Kahle, H. Zentgraf, W. A. Hofmann, P. de Lanerolle, P. Hozak, and I. Grummt. 2004. Nuclear actin and myosin I are required for RNA polymerase I transcription. Nat. Cell Biol. 6:1165–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miralles, F., and N. Visa. 2006. Actin in transcription and transcription regulation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 18:261–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fenteany, G., and S. Zhu. 2003. Small-molecule inhibitors of actin dynamics and cell motility. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 3:593–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giganti, A., and E. Friederich. 2003. The actin cytoskeleton as a therapeutic target: state of the art and future directions. Prog. Cell Cycle Res. 5:511–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zsila, F., Z. Bikadi, and M. Simonyi. 2003. Probing the binding of the flavonoid, quercetin to human serum albumin by circular dichroism, electronic absorption spectroscopy and molecular modelling methods. Biochem. Pharmacol. 65:447–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sengupta, B., and P. K. Sengupta. 2002. The interaction of quercetin with human serum albumin: a fluorescence spectroscopic study. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 299:400–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papadopoulou, A., R. J. Green, and R. A. Frazier. 2005. Interaction of flavonoids with bovine serum albumin: a fluorescence quenching study. J. Agric. Food Chem. 53:158–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sengupta, B., and P. K. Sengupta. 2003. Binding of quercetin with human serum albumin: a critical spectroscopic study. Biopolymers. 72:427–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dufour, C., and O. Dangles. 2005. Flavonoid-serum albumin complexation: determination of binding constants and binding sites by fluorescence spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1721:164–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dangles, O., C. Dufour, and S. Bret. 1999. Flavonol-serum albumin complexation. Two-electron oxidation of flavonols and their complexes with serum albumin. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2:737–744. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spudich, J. A., and S. Watt. 1971. The regulation of rabbit skeletal muscle contraction. J. Biol. Chem. 246:4866–4871. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Isenberg, G. 1995. Cytoskeleton Proteins. Springer, Berlin.

- 27.Koujama, T., and K. Mihashi. 1981. Fluorimetry study of N-1-(pyrenyl)iodoacetamide-labelled F-actin. Local structural change of actin protomer both on polymerisation and on binding of heavy meromyosin. Eur. J. Biochem. 114:33–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doyle, T. C., J. E. Hansen, and E. Reisler. 2001. Tryptophan fluorescence of yeast actin resolved via conserved mutations. Biophys. J. 80:427–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klenchin, V. A., R. King, J. Tanaka, G. Marriott, and I. Rayment. 2005. Structural basis of swinholide A binding to actin. Chem. Biol. 12:287–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kudryashov, D. S., M. R. Sawaya, H. Adisetiyo, T. Norcross, G. Hegyi, E. Reisler, and T. O. Yeates. 2005. The crystal structure of a cross-linked actin dimer suggests a detailed molecular interface in F-actin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:13105–13110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allingham, J. S., A. Zampella, M. V. D'Auria, and I. Rayment. 2005. Structures of microfilament destabilizing toxins bound to actin provide insight into toxin design and activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:14527–14532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Otterbein, L. R., P. Graceffa, and R. Dominguez. 2001. The crystal structure of uncomplexed actin in the ADP state. Science. 293:708–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karasz, M., R. Koerner, M. Marialke, S. Tietze, and A. Apostolakis. 2004. The 15th European Symposium on Quantitative Structure Activity Relationships and Molecular Modelling, 5–10 September 2004, Istanbul, Turkey. E. Aki Sener and I. Yalcin, editors. CADD & Society, Istanbul, Turkey. 493–495.

- 34.Abagyan, R., M. Totrov, and D. Kuznetsov. 1994. ICM—a new method for protein modelling and design. Applications to docking and structure prediction from the distorted native conformation. J. Comput. Chem. 15:488–506. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Apostolakis, J., A. Pluckthun, and A. Caflisch. 1998. Docking small ligands in flexible binding sites. J. Comput. Chem. 19:21–37. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kellenberger, E., J. Rodrigo, P. Muller, and D. Rognan. 2004. Comparative evaluation of eight docking tools for docking and virtual screening accuracy. Proteins. 57:225–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eldridge, M. D., C. W. Murray, T. R. Auton, G. V. Paolini, and R. P. Mee. 1997. Empirical scoring functions. 1. The development of a fast empirical scoring function to estimate the binding affinity of ligands in receptor complexes. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 11:425–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Verdonk, M. L., J. C. Cole, M. J. Hartshorn, C. W. Murray, and R. D. Taylor. 2003. Improved protein-ligand docking using GOLD. Empirical scoring functions: I. The development of a fast empirical scoring function to estimate the binding affinity of ligands in receptor complexes. Proteins. 52:609–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lakowicz, J. R. 1999. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy, 2nd ed. Kluwer Academic, New York.

- 40.Kuznetsova, I. M., T. A. Yakusheva, and K. K. Turoverov. 1999. Contribution of separate tryptophan residues to intrinsic fluorescence of actin. Analysis of 3D structure. FEBS Lett. 452:205–210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mahesha, H. G., S. A. Singh, N. Srinivasan, and A. G. Rao. 2006. A spectroscopic study of the interaction of isoflavones with human serum albumin. FEBS J. 273:451–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arrondo, J. L., J. Castresana, J. M. Valpuesta, and F. M. Goni. 1994. Structure and thermal denaturation of crystalline and noncrystalline cytochrome oxidase as studied by infrared spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 33:11650–11655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Surewicz, W. K., H. H. Mantsch, and D. Chapman. 1993. Determination of protein secondary structure by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy: a critical assessment. Biochemistry. 32:389–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arrondo, J. L., A. Muga, J. Castresana, and F. M. Goni. 1993. Quantitative studies of the structure of proteins in solution by Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 59:23–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dong, A., P. Huang, and W. S. Caughy. 1990. Protein secondary structures in water from second-derivative amide I infrared spectra. Biochemistry. 29:3303–3308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gicquaud, C., and P. Wong. 1994. Mechanism of interaction between actin and membrane lipids: a pressure-tuning infrared spectroscopy study. Biochem. J. 303:769–774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reutzel, R., C. Yoshioka, L. Govindasamy, E. G. Yarmola, M. Agbandje-McKenna, M. R. Bubb, and R. McKenna. 2004. Actin crystal dynamics: structural implications for F-actin nucleation, polymerization, and branching mediated by the anti-parallel dimer. J. Struct. Biol. 146:291–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Erba, H. P., R. Eddy, T. Shows, L. Kedes, and P. Gunning. 1988. Structure, chromosome location, and expression of the human gamma-actin gene: differential evolution, location, and expression of the cytoskeletal beta- and gamma-actin genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8:1775–1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim, H., B. S. Park, K. G. Lee, C. Y. Choi, S. S. Jang, Y. H. Kim, and S. E. Lee. 2005. Effects of naturally occurring compounds on fibril formation and oxidative stress of β-amyloid. J. Agric. Food Chem. 5:8537–8541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moraczewska, J., B. Wawro, K. Seguro, and H. Strzelecka-Golaszewska. 1999. Divalent cation-, nucleotide-, and polymerization-dependent changes in the conformation of subdomain 2 of actin. Biophys. J. 77:373–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Belmont, L. D., A. Orlova, D. G. Drubin, and E. H. Egelman. 1999. A change in actin conformation associated with filament instability after Pi release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:29–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dedova, I. V., V. N. Dedov, N. J. Nosworthy, B. D. Hambly, and C. G. dos Remedios. 2002. Cofilin and DNase I affect the conformation of the small domain of actin. Biophys. J. 82:3134–3143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Valentin-Ranc, C., and M. F. Carlier. 1991. Role of ATP-bound divalent metal ion in the conformation and function of actin. Comparison of Mg-ATP, Ca-ATP, and metal ion-free ATP-actin. J. Biol. Chem. 266:7668–7675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dayel, M. J., E. A. Holleran, and R. D. Mullins. 2001. Arp2/3 complex requires hydrolyzable ATP for nucleation of new actin filaments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 18:14871–14876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gupta, K., and D. Panda. 2002. Perturbation of microtubule polymerization by quercetin through tubulin binding: a novel mechanism of its antiproliferative activity. Biochemistry. 41:13029–13038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zyma, V. L., N. S. Miroshnichenko, V. M. Danilova, and E. En Gin. 1988. Interaction of flavonoid compounds with contractile proteins of skeletal muscle. Gen. Physiol. Biophys. 7:165–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]