Abstract

Pancreatic β-cells are clustered in islets of Langerhans, which are typically a few hundred micrometers in a variety of mammals. In this study, we propose a theoretical model for the growth of pancreatic islets and derive the islet size distribution, based on two recent observations: First, the neogenesis of new islets becomes negligible after some developmental stage. Second, islets grow via a random process, where any cell in an islet proliferates with the same rate regardless of the present size of the islet. Our model predicts either log-normal or Weibull distributions of the islet sizes, depending on whether cells in an islet proliferate coherently or independently. To confirm this, we also measure the islet size by selectively staining islets, which are exposed from exocrine tissues in mice after enzymatic treatment. Indeed revealed are skewed distributions with the peak size of ∼100 cells, which fit well to the theoretically derived ones. Interestingly, most islets turned out to be bigger than the expected minimal size (∼10 or so cells) necessary for stable synchronization of β-cells through electrical gap-junction coupling. The collaborative behavior among cells is known to facilitate synchronized insulin secretion and tends to saturate beyond the critical (saturation) size of ∼100 cells. We further probe how the islets change as normal mice grow from young (6 weeks) to adult (5 months) stages. It is found that islets may not grow too large to maintain appropriate ratios between cells of different types. Our results implicate that growing of mouse islets may be regulated by several physical constraints such as the minimal size required for stable cell-to-cell coupling and the upper limit to keep the ratios between cell types. Within the lower and upper limits the observed size distributions of islets can be faithfully regenerated by assuming random and uncoordinated proliferation of each β-cell at appropriate rates.

INTRODUCTION

Islets of Langerhans are a complex and important tissue, playing a key role in maintaining the appropriate level of glucose in blood; the malfunction of them is closely related to diabetes. They are embedded in the exocrine acinar cells of a pancreas, and composed of several endocrine cells: α-cells (secreting glucagon), β-cells (insulin), δ-cells (somatostatin), and PP-cells (pancreatic polypeptide). There have been extensive studies of these cells of different types, particularly β-cells, which constitute the major cell type (occupying 70–80%) in an islet (1) and secrete the hormone insulin upon increase of the glucose level. In the secretion of insulin, the importance of interactions between β-cells via gap junctions (2,3) has been recognized (4): Coupled β-cells secrete insulin more effectively than single β-cells do, as reflected by the observation that coupled cells can produce bursting action potentials, in contrast with single cells generating spiking action potentials (5). Resulting various oscillatory behaviors of β-cells, together with the insulin secretion and glucose regulation, have been examined (6). In particular, it has been reported that calcium oscillations appear more regular in cell clusters, compared with those in isolated cells (7). Further, beyond the investigation of each cell type, interactions between other cell types have also attracted attention (8–13).

It is known that in mammals the typical size of an islet of Langerhans lies between 100 and 200 μm, regardless of species. On the other hand, the pancreas size depends on species, increasing with the body size. For example, the volume of a human pancreas is several thousand times bigger than the rodent one, to satisfy its role in the bigger scale. It is of interest that the total number of islets increases with the size of the species but the islet size remains more or less in the same range. It was, therefore, proposed that there exists the optimal size of an islet as a functional unit (14). Recently, concentrating on the interactions only between β-cells, we addressed that the physiological property of β-cells depends on the size of the cell cluster (15). Observed are action potential bursts displayed by cell clusters above a minimal size, suggesting that such clusters larger than the minimal size work appropriately. Such bursting behavior is reported to be crucial for efficient insulin secretion. The bursting duration first increases with the size and tends to saturate around some critical size (∼100 cells), beyond which the bursting property appears not to change. Then there arises a question as to how this characteristic behavior with size manifests itself in reality, namely, whether the real size distribution of islets indeed possesses a critical size.

Motivated by these questions, we study the size distribution of Langerhans islets. As for the islet size distribution, there are a number of experimental studies, specifically, in rats (16,17), mice (18–20), pigs (21), and humans (22–25). However, there still lacks theoretical elucidation about the optimal size and morphology of islets as well as their developmental changes. Here we investigate their physiological implications and propose a theoretical model for islet growth, based on the experimental observations. Obtained from this model are log-normal and Weibull distributions, depending on how cells in an islet proliferate. For comparison, we also examine the size distribution and its evolution in mice of 6-weeks and 5-months old, and indeed observe the agreement with the theoretical prediction. In particular, it is suggested that the wide variety of islet size (ranging from 10 to 10,000 cells) for robust bursting action potentials may relate to the random cell proliferation without any preference for a specific islet size, which is one of the two assumptions in the derivation of the distribution function.

THEORETICAL MODEL

Technically, it is very difficult to investigate the size distribution of whole islets in a pancreas and different methods usually lead to different results. On the other hand, the theoretical approach based on recent experimental results about the development of β-cells make it possible to estimate the size distribution of islets. Recently, the development and growth of β-cells have been studied (26). Disclosed, among other findings, are: First, when the body weight is increased due to normal postnatal growth (27,28), pregnancy (29), or obesity (30), the preexisting islets proliferate more to meet the demand for additional β-cell mass, but there is no more neogenesis. Second, β-cells proliferating in islets of all sizes replicate approximately at the same rates; namely, there is no correlation between the islet size and the β-cell replication rate (31–33). Based on these observed facts, we propose a growth model that yields log-normal and Weibull distributions depending on the cell replication procedure in islets.

Log-normal distribution

For simplicity in description, we consider the growth process that in each islet cells replicate coherently with or independently of each other. At first, a newborn islet consists of one cell; it proliferates and has two cells. After proliferating k times, the islet contains 2k cells. Denoting Pk(t) to be the number of islets at the kth proliferation stage, i.e., the number of islets in which cells have proliferated k (= 0, 1, 2, …) times, at time step t, we get the following equation for the growth process of islets:

|

(1) |

where ΔPk(t) ≡ Pk(t + 1) − Pk(t) represents the change of the islet number Pk during the time interval from t to t + 1 and λ is the proliferation rate or probability during the unit replication time. Islets at the (k − 1)th proliferation stage proliferate to become those at the kth stage whereas the islets at the kth stage proliferate to become those at the (k + 1)th stage. As a consequence, Pk(t) increases due to the proliferation of the islets at the (k − 1)th stage, which makes a contribution to Pk(t + 1) out of Pk−1(t). Similarly, it decreases due to the proliferation of the islets at the kth stage, which contributes to Pk+1(t + 1) out of Pk(t). Note that the same proliferation rate λ has been taken at both stages, in accord with the observation that every cell tends to proliferate with the same rate. For k = 0, the above equation describes the change of the number of newborn islets, with the identification of λP−1(t) as the neogenesis rate B(t), i.e., P−1(t) ≡ λ−1B(t).

The actual growth of islets is governed by the dynamic process consisting of gain due to replications and loss due to apoptosis of cells (32,34,35). Therefore, λ corresponds to the average rate of net proliferation of cells, taking into account the rate of loss due to apoptosis. This average rate of net proliferation of cells is also essentially independent of the islet size because the apoptosis rate is relatively lower than the replication rate during islet growth (32). Note further that Eq. 1 describes discrete-time dynamics, where time t is not a continuous but a discrete variable measured in units of the replication time. Accordingly, λ and B(t) in fact denote the proliferation probability and the neogenesis probability, respectively, during the unit time interval, rather than the proliferation and the neogenesis rates. Here the replication time is defined to be the time interval during which the proportion λ among the cells in an islet replicate once. Accordingly, the replication time itself, serving as the unit of time, may not remain constant but vary, since as a mouse grows older, it generally takes more time for a cell to replicate. This definition is useful when we just consider independence of the proliferation rate between islets, lacking in knowledge of the detail proliferation process such as the time dependence of the cell-proliferation rate. As an example, Fig. 1 shows how the islet size configuration changes during two units of (the replication) time for given λ, in the absence of neogenesis (B(t) = 0).

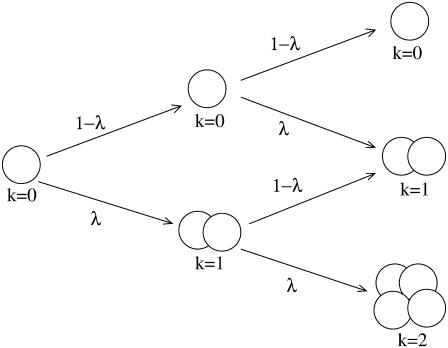

FIGURE 1.

Coherent cell proliferation in an islet. At each replication time, all cells together replicate or not according to the proliferation rate λ. The growth process is illustrated until the second replications and the growth status of each islet is described by the proliferation stage k.

Although there is no exact information on the neogenesis rate B(t) available, the interesting result of the growth dynamics is that any distribution evolves eventually to the normal distribution after sufficient evolution if the neogenesis stops at a certain time. In prenatal development, neogeneses play an important role in the expansion of the β-cell mass, dominant over self-replications. When there are tissue injuries caused by toxic drugs and surgery in postnatal growth, the neogenesis also contributes much to regeneration of β-cells: Whereas self-replication of β-cells leads to only slow expansion under physiological conditions, neogeneses from progenitor or stem cells can lead to vigorous expansion and thus partial regeneration of the β-cell mass in a short time (26). However, no neogenesis is observed during normal physiological renewal in postnatal growth (27).

In this study, we restrict ourselves to the normal physiological condition and assume that the neogenesis stops at time t0. Namely, we take B(t) = 0 for t > t0, which implies that the total number of islets is conserved and equal to the total number at the initial time t0. This allows us to normalize the initial distribution Pk(t0) in a convenient way, such that  Then we can compute the mean

Then we can compute the mean  and the variance

and the variance  of the evolved distribution Pk(t), following the dynamics in Eq. 1:

of the evolved distribution Pk(t), following the dynamics in Eq. 1:

|

(2) |

where τ ≡ t − t0 is the elapsed time (see Appendix I for detail). Further, the distribution Pk(t) is given by a sum of shifted binomial distributions with the weight depending on the initial distribution Pk(t0).

When τ is large, there have been many (net) replications with the rate λ, which makes the final distribution very wide. In comparison with this final width, the initial distribution should be much narrower in width. With the initial width neglected, the evolution reduces to a random-walk problem starting at a fixed position [Pk(t0) = δ(k)], described by a binomial distribution. Here the proliferation stage k corresponds to the distance between the initial and final positions of a random-walker. Accordingly, in the long-time limit  the distribution Pk(t) is expected to approach the normal distribution with the mean

the distribution Pk(t) is expected to approach the normal distribution with the mean  and the variance

and the variance  in Eq. 2.

in Eq. 2.

For large time τ, the mean  as well as the variance

as well as the variance  becomes large, making it appropriate to take the continuum limit. Namely, we regard k as a continuous variable and introduce P(k;t) as the continuum for of

becomes large, making it appropriate to take the continuum limit. Namely, we regard k as a continuous variable and introduce P(k;t) as the continuum for of

We thus have the normal distribution

|

(3) |

which depends on time t through the mean  and the variance

and the variance  given by Eq. 2.

given by Eq. 2.

Remarkably, the normal distribution obtained for the number of islets at given proliferation stage corresponds to a log-normal distribution of the islet size. Here one may define the effective (dimensionless) islet size s to be the cube root of the number n of cells in the kth proliferating islet, i.e., s ≡ n1/3. Then with the relation s = 2k/3 between the islet size s and the proliferation stage k, it is straightforward to obtain the log-normal distribution

|

(4) |

where  and

and  The mean and the variance of the islet size distribution P(s) are thus given by

The mean and the variance of the islet size distribution P(s) are thus given by  and

and  respectively, in comparison with the mean

respectively, in comparison with the mean  and the variance

and the variance  in the distribution P(k) for the proliferation stage k.

in the distribution P(k) for the proliferation stage k.

Weibull distribution

Relaxing the assumption of coherent cell proliferation in an islet, one may consider the growing process that every cell in an islet replicates independently of each other, as illustrated in Fig. 2. Starting from the initial configuration of single cells, this growth dynamics should yield the size distribution of islets (see Appendix II). In this process, as replication proceeds, the possible islet sizes to consider increase geometrically: at replication time t, there are 2t possible islet sizes. Therefore, it is formidable to estimate the size distribution after many replications. To circumvent this difficulty, we resort to Monte Carlo (MC) simulations, which make it possible to estimate the distribution. Namely, we begin with an islet consisting of a progenitor single cell, and allow every cell in the islet to replicate independently, according to the proliferation probability λ at each MC step. Performing such simulations on sufficiently many samples, we can obtain the distribution P(n), where n is the number of cells in an islet, at each replication time. The obtained MC results, shown in Fig. 3, are fully consistent with the analytical results from the matrix calculation described in Appendix II, which can be conducted only in the early replication stage (data not shown).

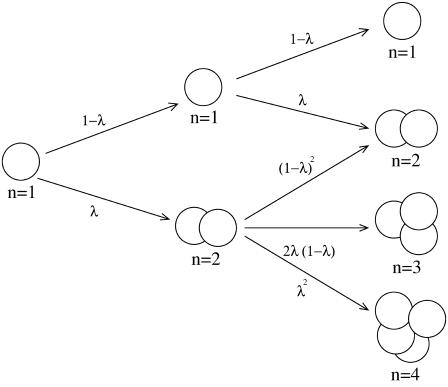

FIGURE 2.

Independent cell proliferation in an islet. At each replication time, every cell replicates with the proliferation rate λ, independently of each other. The growth process is again illustrated until the second replications and the growth status of each islet is described by the total number n of cells in it.

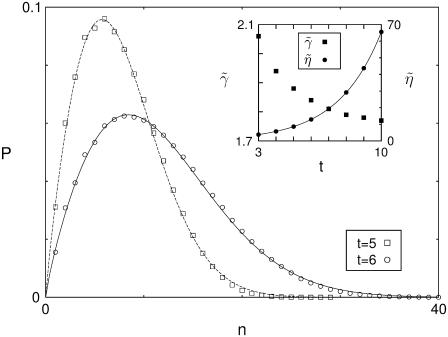

FIGURE 3.

Evolution of the islet size distribution in the case of independent cell proliferation. Starting from the initial configuration of a single cell, the islet evolves with the cell proliferation rate λ = 0.5. Open squares and circles represent the islet size distribution at time t = 5 and 6, respectively, obtained from MC simulations on 106 samples. The data are fitted to the Weibull distribution, plotted with solid and dashed lines. The inset shows the shape parameter  and the scale parameter

and the scale parameter  versus the replication time t, where the solid line corresponds to the function a(1 + λ)t with a = 1.14.

versus the replication time t, where the solid line corresponds to the function a(1 + λ)t with a = 1.14.

It is of interest that the size distribution, resulting from the growth dynamics with independent replication, fits perfectly to the Weibull function with two parameters, the shape parameter  and the scale parameter

and the scale parameter  :

:

|

(5) |

As replication time t increases, the shape parameter  tends to saturate while the scale parameter

tends to saturate while the scale parameter  grows according to

grows according to  the latter reflects that the number of cells in each islet increases by the factor 1 + λ in every replication (see the inset of Fig. 3). Noting the relation n = s3 between the islet size s and the number n of cells, we obtain the size distribution P(s) from Eq. 5:

the latter reflects that the number of cells in each islet increases by the factor 1 + λ in every replication (see the inset of Fig. 3). Noting the relation n = s3 between the islet size s and the number n of cells, we obtain the size distribution P(s) from Eq. 5:

|

(6) |

which is again the Weibull distribution with the shape parameter  and the scale parameter

and the scale parameter

In existing studies a variety of distribution functions have been suggested to fit the experimental data, without any theoretical basis. Included are gamma, Weibull (23), and power-generalized inverse Gaussian distributions (20), as well as log-normal distributions (17). We stress that here, unlike those studies, log-normal and Weibull distributions have been derived theoretically, on the basis of experimental observations.

EXPERIMENTAL METHODS

Chemicals

Modified Hank's buffered saline salt (HBSS) was obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA), collagenase P was from Boehringer (Mannheim, Germany), and all other chemicals from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Isolation of islets and staining

Animal care followed the University of Washington Animal Medicine guidelines. Pancreases were removed from male BALB/c mice (6-weeks and 5-months old) killed with CO2 and sliced regularly at 1-mm intervals through the use of a stack of sharp razor blades. To improve the cutting procedure, a pancreas was placed on a dish coated with a polymer elastomer (Sylgard184, Corning, Midland, MI). Eight pancreatic slices obtained from the whole pancreas were partially digested by incubating them for 25 min in modified Hank's buffered solution, containing 5 mg/ml collagenase P, 1 mg/mL bovine serum albumin, 20 mmol/L HEPES, and 5 mmol/L glucose at 37°C. At the end of the enzymatic treatment, the preparation was gently shaken 20 times to expose islets of Langerhans from acinar cells. Then, islets were incubated to stain for 30 min in the dithizone (DTZ) solution, which consisted of 5 mg DTZ in 25 mL modified Hank's buffered solution. Note that DTZ selectively stains β-cells due to their high zinc content in insulin granules (36).

Measurement of islet size

The partially digested and stained pancreatic pieces were transferred to a narrow chamber (height by width by length = 1 × 5 × 75 mm) made of slide glass. A glass cover minimized the evaporation of HBSS solution during measurement. The size of each islet, stained red, was measured through the use of a reticle of a stereoscope at magnification of 100× (see Fig. 4). Stained islets were back-illuminated with strong white light to improve visibility. This method allowed us to identify islets down to those containing as few as six cells. Here we stress that the size was measured directly from the exposed islets (17,20); this contrasts with the widely used stereological method that estimates the size distribution of islets indirectly from sampling a limited number of sections of a pancreas (16,18,19,21–24,30).

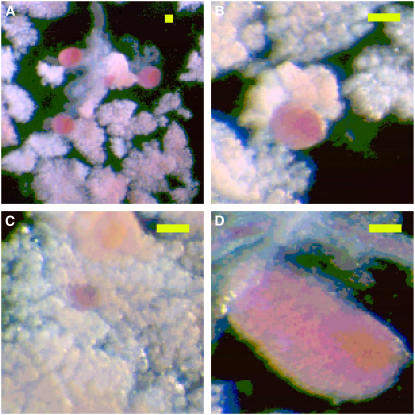

FIGURE 4.

Images of Langerhans islets: (A) Langerhans islets in a low magnification; (B) medium, (C) small, and (D) big islets at the magnification four times higher than panel A. The islets are stained red and attached to the white acinar cells. The size of scale bars is 200 μm.

Estimation of cell number

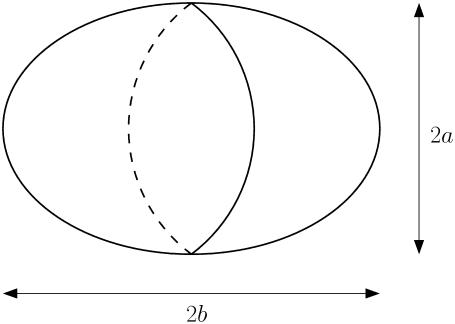

Assuming that each islet has the shape of a prolate spheroid, we measure both the equatorial radius a and the polar radius b of each islet (see Fig. 5). The total cell number n in an islet is then given by

|

(7) |

where V is the islet volume, v is the average volume of a single cell, and r is the average radius of a single cell. The latter has the value r = 5.1 ± 1.5 μm, obtained from 133 cells under a microscope with magnification 200×; the detailed method for cell preparation is described in Chen et al. (37).

FIGURE 5.

Schematic diagram of a prolate spheroid with the equatorial radius a and the polar radius b.

Data analysis

As a fitting routine, we adopt the nonlinear least-squares Marquardt-Levenberg algorithm (provided by a GNUplot package), which accepts a user-defined function. In particular, the weight for fitting is taken to be proportional to the inverse of the variance of each data point, so that the data points with smaller errors have higher weights. Statistical comparison has been made through the use of the nonpaired two-tailed student's t-test and the results are characterized by P-values. Each data set is expressed as the mean value together with the error estimated by the standard deviation.

RESULTS

Size distribution

Fig. 4 shows the typical observed image of DTZ-stained islets, exposed from unstained acinar cells on the upper side of the chamber. We have measured the polar and equatorial radii of a total of 2222 islets from eight mice of 6-weeks old and a total of 2337 islets from eight mice of 5-months old. Note that DTZ in fact stains only β-cells here (see Shiroi et al. (38)). In consequence, to be precise, the effective islet size s ≡ n1/3 = a2/3b1/3r−1 corresponds to the size of the core consisting of β-cells, with the mantle layer of the islet excluded, and thus provides a slight underestimation of the islet size. Note, however, that this is in fact what is described by the theoretical model, which considers the growth of a homogeneous cluster consisting of only β-cells with other cell types such as α- and δ-cells disregarded.

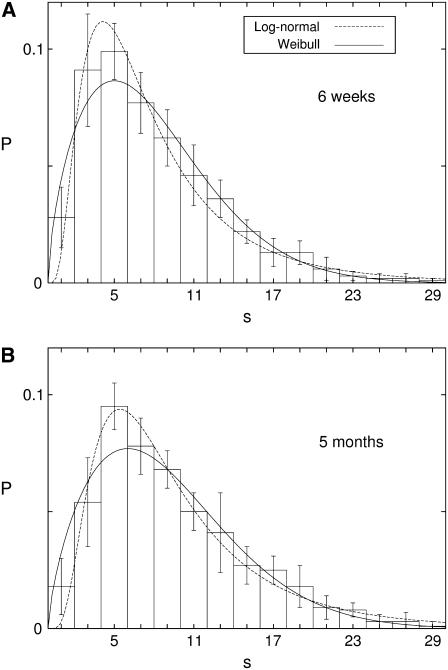

The resulting (normalized) size distributions of islets are plotted in Fig. 6, which shows the evolution as mice grow from 6 weeks to 5 months; the difference in the mean islet size, given by 7.96 ± 0.57 for eight 6-week-old mice (Fig. 6 A) and 9.24 ± 0.78 for eight 5-month-old mice (Fig. 6 B), is significant (P = 0.002). Note that the size s = 1 corresponds roughly to the diameter of a single cell. It is remarkable that in both distributions for the two age groups there arises a peak at s ≈ 5, which appears to give the most optimal size. This is very interesting and indicative, in view of our simulation results that β-cell clusters in general generate longer bursts than single cells but the duration of bursts tend to saturate above the size s ≈ 5 (15).

FIGURE 6.

Islet size distribution obtained from eight mice of (A) 6-weeks old and (B) 5-months old. Dotted lines represent the log-normal distribution with A (μ, σ) = (1.89, 0.68) and (B) (μ, σ) = (2.10, 0.64). Solid lines represent the two-parameter Weibull distribution with (A) (γ, η) = (1.64, 8.89) and (B) (γ, η) = (1.70, 10.15).

It is pleasing that the size distribution, skewed to smaller size, fits well to the log-normal function or the Weibull function derived theoretically. We first consider the log-normal function in Eq. 4. The least-square fit of the experimental data yields the values of the “scale parameter” μ and the “shape parameter” σ in the log-normal function, related with the average and the width: μ = 1.89 ± 0.04 and σ = 0.68 ± 0.05 for 6-week-old mice and μ = 2.10 ± 0.04 and σ = 0.64 ± 0.05 for 5-month-old mice. The resulting distributions are represented by the dotted lines in Fig. 6, A and B. We then fit the experimental data to the Weibull function in Eq. 6, to obtain, from the least-square fit, the shape parameter and the scale parameter (γ, η) = (1.64 ± 0.07, 8.9 ± 0.3) for 6-week-old mice and (1.70 ± 0.08, 10.2 ± 0.4) for 5-month-old mice, and plot the resulting distributions with the solid lines in Fig. 6, A and B. This is to be compared with the human result of the shape parameter γ = 1.2, which was obtained from seven autopsy cases of nondiabetic adults (23). It is thus suggested that the size distribution of mouse islets is narrower than that of human ones.

For comparison of the two fitting functions, we compute their deviations from the experimental data. In the case of 6-week-old mice, the mean-square deviation of the Weibull distribution is found to be 0.037 whereas that of the log-normal distribution turns out to be a little smaller, given by 0.035. For 5-month-old mice, it is given by 0.039 and 0.029 for the Weibull and the log-normal distributions, respectively. From these, it appears that the log-normal distribution provides a better fit than the Weibull distribution. However, it should be noted that in the regime of large islets the experimental data fit much better to the Weibull distribution. Furthermore, such statistical characteristics of the experimental data as the mean islet size

|

(8) |

and the mean cell number in an islet

|

(9) |

are more consistent with the results of the Weibull function (see Table 1), which suggests that the Weibull distribution should give a better description. At this stage, however, the log-normal distribution may not be totally excluded and more sophisticated experiment is necessary to draw a conclusion. In particular, it is also conceivable that cells in an islet proliferate neither fully coherently nor fully independently within the finite interval of unit replication time. If this is the case, the true size distribution is expected to lie in between log-normal and Weibull distributions. This may explain why experimental data exhibit characteristics of both distributions in Fig. 6; as for the mean-square deviations and fitting around the optimal size, the log-normal distribution appears better, whereas the mean values and large-size data are more consistent with the Weibull distribution. In the meantime, the slight difference between the two resulting distributions suggests that the results are not very sensitive to the details of the growth dynamics.

TABLE 1.

Mean islet size  and mean number

and mean number  of cells per islet in 6-week- and 5-month-old mice

of cells per islet in 6-week- and 5-month-old mice

| Experiment

|

Weibull

|

Log-normal

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 6 weeks | 7.96 | 1260 | 7.95 | 1210 | 8.34 | 2320 |

| 5 months | 9.24 | 1800 | 9.06 | 1700 | 10.02 | 3440 |

Results from experimental data are compared with those of the Weibull distribution,  and

and  with the gamma function

with the gamma function  and those of the log-normal distribution,

and those of the log-normal distribution,  and

and

The excellent fit to the theoretically derived function reflects that there are indeed two key characteristics observed in experiment, which are necessary for the derivation of both distributions. First, as we have observed nonselectively all islets exposed on the upper side of the chamber (although the whole islets might not be available), the examined number of islets does not show substantial difference, ranging from 278 ± 52 (for eight mice of 6-weeks old) to 292 ± 70 (for eight mice of 5-months old). It is thus concluded that the total number of islets in a pancreas essentially does not change with time and is conserved. Next, the data, represented by the histogram in Fig. 6, suggest that the difference in the distribution between the two age groups lies mainly in the scale of size. Accordingly, one may obtain the size distribution for older mice from that for younger mice by substituting bs for s with an appropriate scale factor b. Namely, the size distribution for 5-month-old mice is approximately given by b−1P(bs), where P(s) is that for 6-week-old mice. Indeed this is manifested by the Weibull distribution: although the shape parameter γ has not changed appreciably (remaining within the error range) between the two age groups, the scale parameter η has increased significantly from 8.9 to 10.2, indicating that each islet on the average has grown by the factor 10.2/8.9 = 1.15 in size. This corresponds to an increase in the number of cells by the factor (1.15)3 = 1.49, which is comparable with the experimental value 1800/1260 = 1.43 in Table 1.

The asymmetric form of the distribution P(s), skewed to smaller size, shows that large islets account for only a small portion whereas small islets are dominant in number. However, this does not imply that large islets comprise a minor contribution; note that the total number of β-cells in an islet is approximately given by the cube of its size. Accordingly, large islets, albeit small in number, nevertheless contain many cells and contribute substantially to insulin secretion, on the assumption of a similar insulin secretion rate per cell. This may be manifested by considering the total number of β-cells or the amount of secreted insulin corresponding to all islets with given size. Plotting the total number of β-cells versus islet size s, we would thus obtain a distribution less skewed and somewhat symmetric. From this functional point of view, the volume-weighted mean islet volume VV, defined to be the mean volume in the distribution with islets weighted proportional to their volume, was suggested as a more reliable estimator, describing the quantitative appearance of the islet population, than the usual number-weighted mean islet volume VN (39).

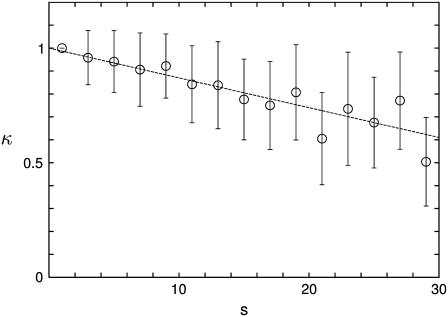

Islet morphometry

The typical images of islets in Fig. 4 demonstrate that whereas small islets are nearly spherical, large islets are usually elongated. To measure the deformation, we consider the ratio κ of the equatorial radius a to the polar radius b, i.e., κ ≡ a/b, which is related with the eccentricity via e = (1 − κ2)1/2. Fig. 7 shows that the ratio κ reduces roughly linearly with the (dimensionless) islet size s.

FIGURE 7.

Radius ratio κ ≡ a/b between the equatorial radius a and the polar radius b versus the islet size s ≡ n1/3. The dotted line represents the linear regression equation given by κ = −0.013 s + 1.00.

DISCUSSION

Direct measurement of islet size

It is very formidable and laborious to measure islets in a pancreas and obtain their size distribution. There are mainly two methods used in existing literature: One is the stereological method, which analyzes dissected islets on the sliced section of a pancreas (16,18,19,21–24,30). The other is direct measurement of exposed islets from exocrine acinar cells (17,28,29). Although the former is powerful to measure even tiny islets scattered in exocrine tissues as single or doublet β-cells, its justification relies largely upon the assumption that islets are embedded randomly within a pancreas. On the other hand, the latter method has the advantage of preserving islet morphology and measuring directly without any assumption as to the relationship between the actual configuration and the observed section surfaces (28). Therefore we have adopted the direct observation method, which is more authentic, taking into consideration the possibility of missing some islets embedded deeply on the exocrine tissues.

The key issue is then how to expose the stained islets. In Bonnevie-Nielsen et al. (28) the dissected pancreas was spread systematically and pressed with a coverglass, while maintaining the height between the slide and the coverglass. There is, however, one drawback that changes of the islet shape are inevitable; although addressed, the pressing effects due to the coverglass were not analyzed fully. To circumvent this, we have instead treated a pancreas mildly with the enzyme collagenase, which loosens the connection between exocrine tissues and islets, and exposed islets better from acinar cells. In the presence of the enzyme islets might be digested, but the effects will be pronounced in the mantles of islets if any (40). Accordingly, the result should not be influenced much because we are actually concerned with the DTZ-stained β-cell clusters, excluding other types of cells on the mantles.

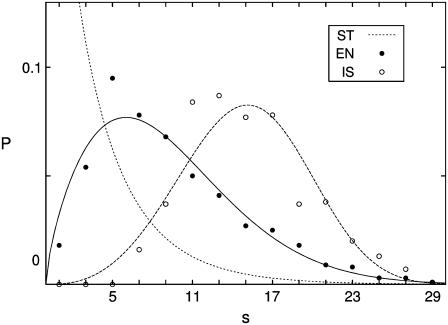

Via this method, we have been able to observe ∼300 islets per pancreas on the average, which is less than the values around 1000 islets in NMRI mice (28) and C57BL/6 ones (29) (see Table 2). There are several possible origins of the number difference: Firstly, we might have missed tiny islets in view of our resolution limiting the detection to 18 μm (corresponding to six cells); this is to be compared with the resolution down to 14 μm (two to three cells) in the conventional isolating method (28,29). Secondly, there might exist the strain difference (41). Lastly, still many islets might not be exposed and embedded in exocrine tissues. However, we stress that the exposed islets have been nonselectively observed and sufficiently numerous (∼2000 islets from eight mice). Therefore the real (normalized) size distribution should not show much difference from our result, except that tiny (proto-) islets consisting of five or fewer cells may be more abundant. For confirmation, we have additionally considered cleared islets, perfectly isolated from four BALB/c mice of 5-months old. Through the use of strong enzymatic treatment followed by the density gradient method, islets have been isolated and separated completely from exocrine tissues. For details of this culture method, the reader is referred to Sweet et al. (42). As a result, 158 ± 39 islets have been obtained from four mice, and the corresponding size distribution is plotted with open circles in Fig. 8. This method thus allows one to prepare clear islets without acinar cells attached but misses a number of small islets.

TABLE 2.

Number Nislet of islets, number nN of cells in the number-weighted mean islet volume, and number nV of cells in the volume-weighted mean islet volume, depending on the strain, age, and body weight

| Strain | Age | Body weight (g) | Nislet | nN | nV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BALB/c | 6 weeks | 20.2 ± 1.2 | §278 ± 52 | 1260 ± 60 | 6900 ± 370 |

| BALB/c | 5 months | 27.0 ± 1.7 | §292 ± 70 | 1800 ± 80 | 7600 ± 510 |

| *C57BL/6JBom-ob/ + | 8 weeks | 27.0 ± 0.9 | 3184 ± 142 | 330 ± 20 | 9400 ± 900 |

| *C57BL/6JBom-ob/ob | 8 weeks | 39.2 ± 0.5 | 3193 ± 160 | 1200 ± 90 | 36,000 ± 4500 |

| †C57BL/6 | 3 months | 21.6 ± 1.6 | 1193 ± 23 | 800 ± 110 | – |

| ‡NMRI | 2 months | 29.9 ± 0.4 | 1125 ± 100 | – | – |

FIGURE 8.

Islet size distribution obtained from three different methods. The dotted line, plotting the result for ob/ + mice, from the stereological method (ST), corresponds to the Weibull distribution with γ = 0.91 and η = 3.36, reconstructed in accord with the number-weighted mean islet volume VN and the volume-weighted mean islet volume VV of the data in Bock et al. (30) (see Table 2). The solid and open circles plot the data for 5-month-old BALB/c mice, obtained from the mild enzymatic treatment (EN) and from the complete isolation of islets (IS), respectively. They are fitted to the solid line and the dashed line, which represent the Weibull distributions with (γ, η) = (1.70, 10.15) and (3.57, 16.60), respectively.

Comparing the three methods, we first point out that the stereological method (ST) allows one to measure tiny islets whereas the isolating method (IS) can expose clearly large islets. However, considering the drawbacks of these methods mentioned previously, we conclude that at this stage our scheme of enzymatic treatment (EN) is advantageous (see Fig. 8). Further, the limitation associated with two-dimensional observation may be overcome in the future by three-dimensional observation, which dissects not physically but optically, e.g., through the use of confocal microscopy, although still many improvements are required (1,43,44).

Abnormal growth of islets to pathogenesis

In a rodent islet, it is well known that the core is occupied only by β-cells whereas all types of cells including α-, β-, δ-, and PP-cells are present in the mantle (1). This structure, with β-cells constituting the core, appears to reflect the fact that even when the endocrine cells are dissociated, β-cells tend to form clusters spontaneously, indicating the existence of adhesion between β-cells (11,45). Note, however, that the structure of human islets is somewhat different: Although the relative volume ratios between different cell types are known and β-cells occupy 70–80% in an islet, cells other than β-cells are also observed inside the islet (1). In addition, it was reported that there is a population of extra-islet β-cells scattered over the exocrine tissue and representing 15% of all β-cells (26).

There exist paracrine interactions between neighboring cells mediated by hormones (46–48) and neurotransmitters (49–52); such paracrine interactions play an important role in the functioning of endocrine cells (53). In view of this, the population ratios between cell types, which control the relative secretion of hormones from each cell type and thus determine the relative strength of paracrine interactions, should not much change as islets grow. Meanwhile, the ratio of the surface area to the volume reduces as the islet size increases whereas non-β-cells exist only in the mantle of the islet, i.e., near the surface. For suppressing the corresponding increase of β-cells and maintaining the relative populations of different cell types, it is advantageous for an islet to grow elongated since the surface area of an elongated islet is larger than that of a spherical one with the same volume. This may provide an explanation of the decrease of κ with the islet size s in Fig. 7.

We point out that islets >300 μm (or s = 30) are not observed in Fig. 6, A and B, which is comparable to the maximal size 380 μm in C57BL/6 mice (29) and 250 μm in a porcine pancreas (21). This size limit may result from the frustration of the relative strength of paracrine interactions or from the insufficient blood supply in bigger islets (17). Another hypothesis focuses on the fact that the surface area of contact between the endocrine and exocrine tissues will enormously increase when many small islets, rather than a few super-islets, exist in a pancreas (14).

In addition to such local paracrine effects in an islet, there also exist global effects that the hormones or neurotransmitters secreted from an islet have influence on the cells in other islets. As a measure of the relative population between different cell types in a pancreas, we consider the ratio ℛ of the total surface area to the total volume of all islets in a pancreas. Recall that the volume of an islet represents the total number of β-cells in the islet whereas the surface area measures the total number of non-β-cells located in the mantle of the islet. It can be expressed in terms of the second and third cumulants of the distribution function:

|

(10) |

for the Weibull distribution function P(s) given by Eq. 6.

As islets grow, the ratio ℛ decreases; this indicates that the relative population of β-cells tends to increase. As the demand for growth increases, e.g., due to pregnancy or obesity, islets continue to grow (18,29). However, large islets, which have grown too much, may not work appropriately because the cellular interactions will be abnormal with the ratio ℛ reduced much and the relative population of β-cells dominant. We speculate that this abnormal situation is related with, among other possibilities, the obese-hyperglycemic syndrome, where most islets indeed become abnormally large (18,19).

CONCLUSION

It has been demonstrated that size distributions of mouse islets are well described with the following assumptions: Neogeneses of new islets are negligible after some development stage, and every cell in a pancreas proliferates with the same rate, regardless of whether the cell belongs to a small islet or to a large islet. Based on these observations, we have proposed a theoretical model for the growth of islets. Depending on whether cells in each islet proliferate coherently or independently, the model results in log-normal or Weibull distributions for the islet size. Of the two, the latter in general represents the statistical characteristics of experimental data better than the former, and fits very well in the regime of large islets. However, the difference between the two is not very big, suggesting that the results are not sensitive to the details of the growth dynamics. Note also that cells in an islet are likely to proliferate neither fully coherently nor fully independently within the unit replication time; this will lead to the size distribution of the form between the two distributions. At first glance, such skewed size distributions of islets appear to be unusual, in view of the normal distribution ubiquitous in nature. Unlike the size distribution P(s), the proliferation stage distribution P(k), evolving spontaneously after cease of the neogenesis, turns out more or less normal.

The evolution of the size distribution of islets is a random process, where every cell in a pancreas can equally proliferate to make each islet grow. As for the resulting increase of the islet size, we examine the lower and upper limits of the islet size. Coupled β-cells secrete insulin more effectively than single β-cells do, which reflects that coupled cells can produce bursting action potentials, in contrast with single cells generating spiking action potentials. In our previous work, the established model for coupled β-cells has been studied under the physiological strength of the gap junction (15). Observed are bursts displayed by clusters above the size s = 3, suggesting that a cluster of size above s = 3 can work appropriately. The bursting duration first increases with the size s and tends to saturate around s = 5, beyond which the bursting property appears not to change. As for the upper limit of the islet size, Fig. 6 shows that there are no islets above s = 30. One possible explanation for the upper limit is that the relative populations of cells of different types determine the paracrine interactions between them. Since non-β-cells exist mostly in the mantle of islets (1), it is very difficult to maintain the relative populations as the area/volume ratio keeps decreasing with the increase of the islet size; the elongate shape of a large islet helps to circumvent this difficulty. Beyond the upper limit of the islet size, the relative population of β-cells should become too high, concerning the local paracrine effects in an islet. This may give constraint on the assumption of random cell proliferation in too large islets.

In summary, our study of how islets grow to satisfy the demand of growing body shows that each islet in general grows proportionally to the number of cells in the islet; i.e., each islet may grow faithfully to the external demand, independently of others. The growth of islets is robust in the sense that it is not very sensitive to the details of the developmental process; an islet works normally when a few β-cells are coupled. Our growth model might thus be rather general, applicable to a variety of growth processes in other tissues with constant proliferation rates.

Acknowledgments

We thank I. Sweet for critical comments on the manuscript and B. Hille and R. Braun for hospitality during our stay at University of Washington, where experimental part of this work was carried out. We also thank M. Gilbert for islet isolation.

We acknowledge the support from the Ministry of Science and Technology and the Korean Science and Engineering Foundation through National Core Research Center for Systems Bio-Dynamics and from the BK21 Program.

APPENDIX I

Equation 1 describing the growth dynamics can be written in the matrix form:

|

(11) |

where the growth matrix G reads

|

Here P(t) and B(t) are column matrices, the transposes of which are given by PT(t) ≡ [P0(t), P1(t), P2(t), …] and BT(t) ≡ [B(t), 0, 0, …], respectively.Following the experimental observation that neogeneses of islets are negligible after some developing time t0, we put B(t) = 0 for t > t0. The evolution dynamics in Eq. 11 then reduces to P(t + 1) = GP(t), and we can generate the distribution P(t) at time t, evolving from the initial distribution P(t0), by iteration:

|

(12) |

with τ = t − t0. The τth order of G obtains the form

|

where gn is the binomial coefficient:

|

Given normalized distribution Pk(t0), the later distribution Pk(t) can be obtained from Eq. 12:

|

(13) |

where Bk(τ, λ) denotes the kth shifted binomial distribution defined by (0, …, 0, g0, g1, …, gτ, 0,…) with g0 being the (k + 1)th element. Therefore, Eq. 13 is simply a weighted sum of the kth shifted binomial distributions, where the weight is determined by the initial distribution Pk(t0). Note that the binomial distribution can be approximated well by the normal distribution, reducing to the latter for large τ. From the characteristics of a binomial distribution, it is straightforward to obtain the first and second cumulants, μ1(k) and μ2(k), of the shifted binomial distribution Bk(τ, λ): μ1(k) = τλ + k and  Equation 13 then leads to the mean and the variance of the distribution P(t):

Equation 13 then leads to the mean and the variance of the distribution P(t):

|

|

which is just Eq. 2.

APPENDIX II

In the case of independent cell proliferation illustrated in Fig. 2, the growth process of islets can also be expressed as a matrix equation similar to Eq. 11, where the kth component of P(t) represents the islets of cells proliferating k times. Here, on the other hand, the kth component designates the islets containing k cells. The growth matrix G then reads

|

where the components are given by

|

Therefore, assuming negligible neogeneses of islets after time t0, one can obtain the distribution P(t) at later time t in a manner similar to Eq. 12: P(t) = GτP(t0) with τ ≡ t − t0. Unfortunately, unlike in Appendix I, it is formidable to write the explicit form of Gτ, limiting analytical treatment to small values of τ, i.e., early replication stages.

Editor: Arthur Sherman.

References

- 1.Brissova, M., M. J. Fowler, W. E. Nicholson, A. Chu, B. Hirshberg, D. M. Harlan, and A. C. Powers. 2005. Assessment of human pancreatic islet architecture and composition by laser scanning confocal microscopy. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 53:1087–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pérez-Armendariz, M., C. Roy, D. C. Spray, and M. V. L. Bennett. 1991. Biophysical properties of gap junctions between freshly dispersed pairs of mouse pancreatic β-cells. Biophys. J. 59:76–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mears, D., N. F. Sheppard, I. Atwater, and E. Rojas. 1995. Magnitude and modulation of pancreatic β-cell gap junction electrical conductance in situ. J. Membr. Biol. 146:163–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sherman, A., and J. Rinzel. 1991. Model for synchronization of pancreatic β-cells by gap junction coupling. Biophys. J. 59:547–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sherman, A., J. Rinzel, and J. Keizer. 1988. Emergence of organized bursting in clusters of pancreatic β-cells by channel sharing. Biophys. J. 54:411–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang, H., J. Jo, H. J. Kim, M. Y. Choi, S. W. Rhee, and D. S. Koh. 2005. Glucose metabolism and oscillatory behavior of pancreatic islets. Phys. Rev. E. 72:051905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jonkers, F. C., J. C. Jonas, P. Gilon, and J. C. Henquin. 1999. Influence of cell number on the characteristics and synchrony of Ca2+ oscillations in clusters of mouse pancreatic islet cells. J. Physiol. 520:839–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hopcroft, D. W., D. R. Mason, and R. S. Scott. 1985. Structure-function relationships in pancreatic islets: support for intraislet modulation of insulin secretion. Endocrinology. 117:2073–2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nadal, A., I. Quesada, and B. Soria. 1999. Homologous and heterologous asynchronicity between identified alpha-, beta- and delta-cells within intact islets of Langerhans in the mouse. J. Physiol. 517:85–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanno, T., S. O. Göpel, P. Rorsman, and M. Wakui. 2002. Cellular function in multicellular system for hormone-secretion: electrophysiological aspect of studies on α-, β- and δ-cells of the pancreatic islet. Neurosci. Res. 42:79–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamaguchi, K., N. Utsunomiya, R. Takaki, H. Yoshimatsu, and T. Sakata. 2003. Cellular interaction between mouse pancreatic α-cell and β-cell lines: possible contact-dependent inhibition of insulin secretion. Exp. Biol. Med. 228:1227–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weir, G. C., and S. Bonner-Weir. 1990. Islets of Langerhans: the puzzle of intraislet interactions and their relevance to diabetes. J. Clin. Invest. 85:983–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soria, B., E. Andreu, G. Berná, E. Fuentes, A. Gil, T. León-Quinto, F. Martín, E. Montanya, A. Nadal, J. A. Reig, C. Ripoll, E. Roche, J. V. Sanchez-Andrés, and J. Segura. 2000. Engineering pancreatic islets. Pflugers Arch. 440:1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henderson, J. R. 1969. Why are the islets of Langerhans? Lancet. 2:469–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jo, J., H. Kang, M. Y. Choi, and D. S. Koh. 2005. How noise and coupling induce bursting action potentials in pancreatic β-cells. Biophys. J. 89:1534–1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hellman, B. 1959. The volumetric distribution of the pancreatic islet tissue in young and old rats. Acta Endocrinol. (Copenh.). 31:91–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lifson, N., C. V. Lassa, and P. K. Dixit. 1985. Relation between blood flow and morphology in islet organ of rat pancreas. Am. J. Physiol. 249:E43–E48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hellman, B., S. Brolin, C. Hellerström, and K. Hellman. 1961. The distribution pattern of the pancreatic islet volume in normal and hyperglycaemic mice. Acta Endocrinol. (Copenh.). 36:609–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gepts, W., J. Christophe, and J. Mayer. 1960. Pancreatic islets in mice with the obese-hyperglycemic syndrome: lack of effect of carbutamide. Diabetes. 9:63–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonnevie-Nielsen, V., and L. T. Skovgaard. 1984. Pancreatic islet volume distribution: direct measurement in preparations stained by perfusion in situ. Acta Endocrinol. (Copenh.). 105:379–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jay, T. R., K. A. Heald, N. J. Carless, D. E. Topham, and R. Downing. 1999. The distribution of porcine pancreatic beta-cells at ages 5, 12, 24 weeks. Xenotransplantation. 6:131–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hellman, B. 1959. b. Actual distribution of the number and volume of the islets of Langerhans in different size classes in non-diabetic humans of varying ages. Nature. 184:1498–1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saito, K., N. Iwama, and T. Takahashi. 1978. Morphometrical analysis on topographical difference in size distribution, number and volume of islets in the human pancreas. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 124:177–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saito, K., T. Takahashi, N. Yaginuma, and N. Iwama. 1978. Islet morphometry in the diabetic pancreas of man. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 125:185–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson, W. R., R. Tennat, and R. Hussey. 1933. Frequency-distribution of volume of islands of Langerhans in the pancreas of man, monkey and dog. Science. 78:2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bouwens, L., and I. Rooman. 2005. Regulation of pancreatic β-cell mass. Physiol. Rev. 85:1255–1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dor, Y., J. Brown, O. I. Martinez, and D. A. Melton. 2004. Adult pancreatic beta-cells are formed by self-duplication rather than stem-cell differentiation. Nature. 429:41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonnevie-Nielsen, V., L. T. Skovgaard, and A. Lernmark. 1983. β-cell function relative to islet volume and hormone content in the isolated perfused mouse pancreas. Endocrinology. 112:1049–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parsons, J. A., A. Bartke, and R. L. Sorenson. 1995. Number and size of islets of Langerhans in pregnant, human growth hormone-expressing transgenic, and pituitary dwarf mice: effect of lactogenic hormones. Endocrinology. 136:2013–2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bock, T., B. Pakkenberg, and K. Buschard. 2003. Increased islet volume but unchanged islet number in ob/ob mice. Diabetes. 52:1716–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brelje, T. C., J. A. Parsons, and R. L. Sorenson. 1994. Regulation of islet β-cell proliferation by prolactin in rat islets. Diabetes. 43:263–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Teta, M., S. Y. Long, L. M. Wartschow, M. M. Rankin, and J. A. Kushner. 2005. Very slow turnover of β-cells in aged adult mice. Diabetes. 54:2557–2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teta, M., M. M. Rankin, S. Y. Long, G. M. Stein, and J. A. Kushner. 2007. Growth and regeneration of adult β cells does not involve specialized progenitors. Dev. Cell. 12:817–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Finegood, D. T., L. Scaglia, and S. Bonner-Weir. 1995. Dynamics of β-cell mass in the growing rat pancreas: estimation with a simple mathematical model. Diabetes. 44:249–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonner-Weir, S. 2001. β-cell turnover: its assessment and implications. Diabetes. 50:S20–S24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Latif, Z. A., J. Noel, and R. Alejandro. 1988. A simple method of staining fresh and cultured islets. Transplantation. 45:827–830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen, L., D. S. Koh, and B. Hille. 2003. Dynamics of calcium clearance in mouse pancreatic β-cells. Diabetes. 52:1723–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shiroi, A., M. Yoshikawa, H. Yokota, H. Fukui, S. Ishizaka, K. Tatsumi, and Y. Takahashi. 2002. Identification of insulin-producing cells derived from embryonic stem cells by zinc-chelating dithizone. Stem Cells. 20:284–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skau, M., B. Pakkenberg, K. Buschard, and T. Bock. 2001. Linear correlation between the total islet mass and the volume-weighted mean islet volume. Diabetes. 50:1763–1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.El-Naggar, M. M., A. A. Elayat, M. S. M. Ardawi, and M. Tahir. 1993. Isolated pancreatic islets of the rat: an immunohistochemical and morphometric study. Anat. Rec. 237:489–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bock, T., B. Pakkenberg, and K. Buschard. 2005. Genetic background determines the size and structure of the endocrine pancreas. Diabetes. 54:133–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sweet, I. R., D. L. Cook, E. DeJulio, A. R. Wallen, and G. Khalil. 2004. Regulation of ATP/ADP in pancreatic islets. Diabetes. 53:401–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brelje, T. C., D. W. Scharp, and R. L. Sorenson. 1989. Three-dimensional imaging of intact isolated islets of Langerhans with confocal microscopy. Diabetes. 38:808–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hara, M., R. F. Dizon, B. S. Glick, C. S. Lee, K. H. Kaestner, D. W. Piston, and V. P. Bindokas. 2006. Imaging pancreatic β-cells in the intact pancreas. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 290:E1040–E1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lumelsky, N., O. Blondel, P. Laeng, I. Velasco, R. Ravin, and R. McKay. 2001. Differentiation of embryonic stem cells to insulin-secreting structures similar to pancreatic islets. Science. 292:1389–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Franklin, I. K., J. Gromada, A. Gjinovci, S. Theander, and C. B. Wollheim. 2005. β-cell secretory products activate α-cell ATP-dependent potassium channels to inhibit glucagon release. Diabetes. 54:1808–1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ravier, M. A., and G. A. Rutter. 2005. Glucose or insulin, but not zinc ions, inhibit glucagon secretion from mouse pancreatic α-cells. Diabetes. 54:1789–1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brunicardi, F. C., R. Kleinman, S. Moldovan, T. L. Nguyen, P. C. Watt, J. Walsh, and R. Gingerich. 2001. Immunoneutralization of somatostatin, insulin, and glucagon causes alterations in islet cell secretion in the islolated perfused human pancreas. Pancreas. 23:302–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moriyama, Y., and M. Hayashi. 2003. Glutamate-mediated signaling in the islets of Langerhans: a thread entangled. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 24:511–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Franklin, I. K., and C. B. Wollheim. 2004. GABA in the endocrine pancreas: its putative role as an islet cell paracrine-signalling molecule. J. Gen. Physiol. 123:185–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wendt, A., B. Birnir, K. Buschard, J. Gromada, A. Salehi, S. Sewing, P. Rorsman, and M. Braun. 2004. Glucose inhibition of glucagon secretion from rat α-cells is mediated by GABA released from neighboring β-cells. Diabetes. 53:1038–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brice, N. L., A. Varadi, S. J. H. Ashcroft, and E. Molnar. 2002. Metabotropic glutamate and GABAb receptors contribute to the modulation of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia. 45:242–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cherrington, A. D., J. L. Chiasson, J. E. Liljenquist, A. S. Jennings, U. Keller, and W. W. Lacy. 1976. The role of insulin and glucagon in the regulation of basal glucose production in the postabsorptive dog. J. Clin. Invest. 58:1407–1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]