Abstract

O6-Methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) is a DNA repair protein that protects cells from the biological consequences of alkylating agents by removing alkyl groups from the O6-position of guanine. Cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide are oxazaphosphorines used clinically to treat a wide variety of cancers; however, the role of MGMT in recognizing DNA damage induced by these agents is unclear. In vitro evidence suggests that MGMT may protect against the urotoxic oxazaphosphorine metabolite, acrolein. Here, we demonstrate that Chinese hamster ovary cells transfected with MGMT are protected against cytotoxicity following treatment with chloroacetaldehyde (CAA), a neuro- and nephrotoxic metabolite of cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide. The mechanism by which MGMT recognizes damage induced by acrolein and CAA is unknown. CHO cells expressing a mutant form of MGMT (MGMTR128A) known to have >1,000-fold less repair activity towards alkylated DNA while maintaining full active site transferase activity towards low molecular weight substrates exhibited equivalent CAA- and acrolein-induced cytotoxicity to that of CHO cells transfected with plasmid control. These results imply that direct reaction of acrolein or CAA with the active site cysteine residue of MGMT, i.e. scavenging, is unlikely a mechanism to explain MGMT protection from CAA and acrolein-induced toxicity. In vivo, no difference was detected between Mgmt −/− and Mgmt +/+ mice in the lethal effects of cyclophosphamide. While MGMT may be important at the cellular level, mice deficient in MGMT are not significantly more susceptible to cyclophosphamide, acrolein or CAA. Thus, our data does not support targeting MGMT to improve oxazaphosphorine therapy.

Overview

Alkylating agents in common clinical use today (e.g., methylating agents, chloroethylating agents and oxazaphosphorines) produce their biological effect by transferring alkyl groups to cellular molecules, such as DNA, RNA and proteins [1–4]. These agents react with nucleophilic sites including the oxygen and nitrogen of nucleic acids, as well as the oxygen of the phosphodiester groups within the backbone of DNA. Methylating agents most commonly react with the N7-position of guanine, although evidence implicates the O6-alkylguanine as the critical biological lesion eventually leading to mutations and cellular death [1]. Chloroethylating agents, such as 1,3-bis(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea (BCNU), and oxazaphosphorines, including cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide, eventually lead to DNA interstrand cross-links and subsequent death [5,6]. Unfortunately, tumor resistance to alkylating agents results in eventual clinical failure. A prominent mechanism of resistance against the biological effects of methylating and chloroethylating agents is the DNA repair protein, O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT). Although there is evidence for some role of MGMT as a mechanism of resistance against the biological effects of cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide, the exact mechanism is not clear.

O6-Methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase

MGMT is a 22-kDa protein that repairs O6-alkylguanine adducts on DNA without the aid of other cofactors or proteins [7,8]. MGMT binds to DNA via a helix-turn-helix motif in the C-terminal domain while a second helix, containing an arginine “finger,” flips out the alkylated base into the active site of the protein [9]. The conserved active site, IPCHRV/I, is involved in the direct transfer of the alkyl group from the alkylated base to the cysteine, Cys145, acceptor residue [7,8]. This transfer results in “suicide” inactivation of MGMT by the irreversible alkylation of the cysteine moiety and by changing the conformation of the DNA-binding domain of MGMT [9,10]. MGMT then becomes detached from DNA and is targeted for degradation by ubiquitination [11]. MGMT activity is restored in the cell after de novo synthesis [7,8].

MGMT is expressed in all normal tissues but varies in expression levels with very low levels observed in bone marrow cells [12–14]. Approximately 20% of human tumor cell lines exhibit low MGMT activity and are sensitive to the cytotoxic and mutagenic effects of O6-alkylating agents [8,15]. Unfortunately, the majority of tumor cells have high levels of MGMT [16,17] resulting in the limited usefulness of O6-alkylating agents as therapeutic agents [8,15,18–20].

In attempts to increase the sensitivity of tumor cells to the cytotoxic effects of O6-alkylating agents, potent, irreversible inactivators of MGMT have been developed. Since MGMT is inactivated upon removal of alkyl groups from the O6-position of guanine, pseudo-substrates (O6-substituted guanines) have been synthesized and tested. O6-Benzylguanine (BG) has been found to rapidly deplete MGMT activity to undetectable levels at micromolar concentrations and to increase the sensitivity of human tumor cells and xenografts to the cytotoxic effects of O6-alkylating agents [21–23]. More recently, McElhinney et al. [24] have developed O6-4-bromothenylguanine (PaTrin-2). Similar to BG, PaTrin-2 increases the sensitivity of human tumor cells and xenografts to the cytotoxic effects of O6-alkylating agents [25-28]. The promising results in xenograft studies combining MGMT inhibitors, either BG or PaTrin-2, plus O6-alkylating agents have lead to numerous clinical trials aimed at increasing the efficacy of temozolomide or BCNU.

Clinical utility of cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide

Cyclophosphamide has been used in the treatment of many primary malignancies, including hematopoietic and a variety of solid tumors (breast, lung, ovarian and prostate cancer), and at high doses in bone marrow transplantations because of its immunosuppressive activity [4,29–32]. Cyclophosphamide is also used as an immunosuppressive agent to treat autoimmune diseases. Ifosfamide has shown antitumor activity in many of the same cancers as those sensitive to cyclophosphamide but is also used to treat bladder and cervical cancer, neuroblastoma, Ewing sarcoma and uterine sarcoma [4]. While both cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide are used alone, most often each is a component of multi-drug regimens used against breast cancer (mainly cyclophosphamide-containing regimens) or lymphoma and lung cancer (ifosfamide).

Role of MGMT in clinical response to cyclophosphamide

While the role of MGMT in protecting against toxicity induced by methylating and chloroethylating agents is well established, the role of MGMT in protecting against the genotoxic effects of cyclophosphamide is less clear. Correlative clinical studies conducted on ovarian cancer [33–35], diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [36–38] and breast cancer patients [39,40] conflict on the relationship between MGMT levels and response to cyclophosphamide. Chen et al. [33] found that, in general, poor responders to chemotherapy (cyclophosphamide plus cisplatin or carboplatin) had tumors with measurable pre-therapy MGMT activity levels (> 10 fmol/mg protein), while another study did not find this association [35]. In line with the latter, Codegoni et al. [34] did not find a correlation with MGMT mRNA expression in tumors from ovarian cancer patients and response to cyclophosphamide with doxorubicin plus or minus cisplatin. Several studies have found tumors negative for MGMT immunohistochemical staining [38] or with MGMT promoter methylation [36–38] to be significantly associated with increased overall survival of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients following cyclophosphamide and other drugs. On the other hand, Cayre et al. [39] did not find MGMT mRNA in tumor biopsies from breast cancer to be predictive of response to cyclophosphamide.

Role of MGMT in resistance to cyclophosphamide in xenograft studies

Equally conflicting are results describing the role of MGMT in resistance to the antitumor effects of cyclophosphamide in mice xenograft experiments [41–43]. Mattern et al. [43] showed lung tumor xenografts with high MGMT activity were less sensitive to the growth-inhibitory effects of cyclophosphamide than those with low MGMT activity (p <0.05). Interestingly, 2 of the 5 tumor xenografts in this study that had the greatest response to cyclophosphamide had considerable MGMT activity levels (> 370 fmol/mg protein) [43]. Additionally, using a BCNU-resistant glioblastoma cell line, Friedman et al. [42] showed that the antitumor activity following cyclophosphamide was slightly increased after MGMT depletion with BG compared to cyclophosphamide alone (p = 0.07). The conclusions of the authors (i.e., cyclophosphamide activity was modulated by MGMT activity) must be re-examined in light of more recent studies showing an MGMT-independent role for BG in enhancing the cytotoxicity of some alkylating agents [44–47]. Specifically, BG was shown to significantly enhance the cytotoxicity and decrease the mutagenicity of nitrogen mustards [i.e., phosphoramide mustard (PM), melphalan, and chlorambucil], a group of alkylating agents not known to produce O6-adducts in DNA. The enhancement is observed in cells irrespective of AGT activity. The data suggests that treatment with BG causes G1 arrest and drives non-cycling cells treated with nitrogen mustards into apoptosis [44] Lastly, a study on 23 different xenografts tumors showed no correlation between the antitumor activity of cyclophosphamide and tumor MGMT activity levels [41]. Although 5/23 of the tumor cell lines used to establish xenografts in this study had low MGMT levels, only one of the 5 was responsive to cyclophosphamide-induced growth inhibition [41]. Taken together, the above studies illustrate the role of MGMT in resistance to cyclophosphamide in vivo has yet to be fully defined.

Metabolism of cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide

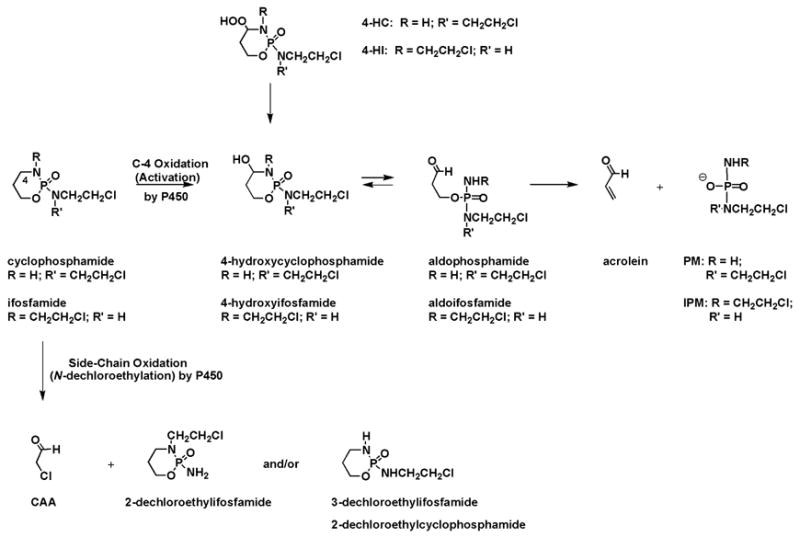

As shown in Scheme 1, cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide are prodrugs that are activated by oxidation at the C-4 position via the hepatic cytochrome P450 enzymes [4,32] resulting in the formation of 4-hydroxycyclophosphamide and 4-hydroxyifosfamide, respectively. Each 4-hydroxy intermediate rapidly interconverts with an acyclic aldehyde, aldophosphamide or aldoifosfamide. These aldehydes spontaneously (non-enzymatically) fragment leading to acrolein and either phosphoramide mustard (PM) or isophosphoramide mustard (IPM). Competing with C-4 oxidation is the P450-mediated, oxidative N-dechloroethylation of a side chain resulting in the production of chloroacetaldehyde (CAA). This pathway accounts for less than 10% of the metabolism of cyclophosphamide [29–31] but can be a significant contributor in the metabolism of ifosfamide (up to 50%) [48].

Scheme 1.

Essential Elements of the Metabolism of Cyclophosphamide and Ifosfamide

The therapeutic effects of cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide are attributed to PM and IPM, respectively, while acrolein and CAA are associated with unwanted side effects [29]. PM and IPM have been shown to produce interstrand cross-links between the N7-positions of guanines on opposite DNA strands in a G-N-C/C-N-G orientation [49,50]; these cross-links are believed to be the major cytotoxic lesion [5]. The interstrand cross-link produced from PM is slightly shorter, five-atoms, than the seven-atom linkage produced from IPM [50]. Acrolein is thought to be responsible for the dose limiting urotoxicity of cyclophosphamide [51], with the contribution of PM being very little [52]. Acrolein concentrations (~ 40 nM) peak 1 – 12 hr following cyclophosphamide or ifosfamide treatment [53]. Mesna (2-mercaptoethane sulfonate), which has a nucleophilic thiol, is used to protect against cyclophosphamide- and ifosfamide-induced bladder toxicity by directly reacting with acrolein (and, possibly, other metabolites) in the bladder [54,55]. Recently, the thiols (or thiol-quivalent) amifostine and glutathione were shown to prevent acrolein induced hemorrhagic cystitis in the bladder of mice [56]; however, the efficacy of these agents in combination with oxazaphosphorines in humans has yet to be determined.

CAA is thought to be responsible for the neuro- and nephrotoxicity associated with ifosfamide [57–61]. Studies have begun to show that the P450 isoenzymes necessary for N-dechloroethylation (primarily CYP 3A4/5 and, to a lesser extent, 2B6) are present and active in kidneys of children and adults [62–64]. Pharmacokinetic modeling, using data from renal tubule cells exposed to 100 μM ifofosfamide, estimated the steady-state concentration of CAA could reach 80 μM [65]. Together, these studies suggest that localized production of CAA from ifosfamide in the kidney could contribute to the nephrotoxicity associated with ifosfamide therapy. The mechanism of CAA-induced neurotoxicity has been primarily attributed to glutathione depletion and therefore impaired detoxification of ifosfamide and its metabolites (reviewed in [66]). Neurotoxicity can last up to several days even following multiple doses of methylene blue [67,68]. Glutathione has been shown to decrease CAA- and acrolein-induced cell death in vitro [69,70] and attempts to increase glutathione levels clinically would most likely decrease the unwanted side effects from both of these metabolites; however, glutathione has been linked to detoxification/inactivation of cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide and their metabolites [71] and may impair antitumor activity.

Biological effects of acrolein and CAA

Several mechanisms by which acrolein and CAA result in cellular toxicities have been described [42,72–75]. In addition to being a metabolite of cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide, acrolein is a by-product of lipid peroxidation [76]. Studied as such, acrolein has been shown to induce expression of heme oxygenase-1, a cytoprotective enzyme, which can be blocked by tyrosine kinase inhibitors [72]. Acrolein has also been shown to result in neuronal cell death following a 100 μM dose for 4 h, with apparent changes to the cytoskeletal structures [73]. Acrolein is also in tobacco smoke and can accumulate in vivo bound to proteins. The etiology and consequence of these acrolein-protein conjugates is under study. Both acrolein and CAA have been described to alter Ca2+ homeostasis [74] and disruption of mitochondria oxidative phosphorylation [75]. At concentrations as little as 10 μM, acrolein increases intracellular Ca2+ resulting in increased nitric oxide levels, which may explain the mechanism of how acrolein exposure results in apoptosis in human endothelial cells [77]. In vitro, it appears cellular death following acrolein and CAA is primarily by necrosis with only a small extent of death via apoptosis [69,73].

Acrolein and CAA have been shown to alkylate DNA [78–81]. Acrolein has been shown to form cyclic adducts between the N1 and exocyclic amino nitrogen of guanine in DNA [78,79]. Fibroblasts from xeroderma pigmentosum patients (nucleotide-excision repair deficient) are more susceptible to acrolein-induced cytotoxicity compared to fibroblasts from normal patients, suggesting that nucleotide-excision repair is important in protecting against toxicity induced by acrolein [82]. CAA is reported to form two exocyclic guanine adducts, N2,3-ethenoguanine and 1,N2-ethenoguanine [80,81,83]. Both base- and nucleotide-excision repair systems have been shown to be involved in repair of these CAA-induced adducts [83] and, in neuronal cells, it appears both base- and nucleotide-excision repair pathways are important in protecting against CAA-induced cell death [84]. A role for MGMT in protecting against acrolein and CAA has been proposed [42,45].

Role of MGMT in protecting against cyclophosphamide in vitro

Most cells grown in culture lack the P450 enzymes necessary for cyclophosphamide or ifosfamide activation; therefore, pre-activated forms of cyclophosphamide or ifosfamide are used including 4-hydroperoxycyclophosphamide (4-HC) and 4-hydroperoxyifosfamide (4-HI), respectively. Synthetic 4-HC and 4-HI provide facile access to the active metabolites of cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide, respectively (Scheme 1). In solution, the hydroperoxides spontaneously (non-enzymatic) produce the corresponding 4-hydroxy metabolites which then provide the aldehydic intermediates and, ultimately, acrolein and PM or IPM. Using CHO cell lines expressing high levels of MGMT and cell lines lacking MGMT, Cai et al. [45] demonstrated that the sensitivity of CHO cells expressing MGMT to the cytotoxic and mutagenic effects of 4-HC was lower than in CHO cells lacking MGMT. These studies further evaluated the metabolites of cyclophosphamide using authentic acrolein, PM and 4-hydroperoxydidechlorocyclophosphamide (4-HDC, a compound that mimics the chemistry of 4-HC but produces acrolein and a non-alkylating, non-toxic analog of PM (−OP(O)(NH2)N(CH 2CH3)2) [85]). MGMT expressing CHO cells were protected against the cytotoxicity and mutagenicity of 4-HDC and acrolein, but not PM. Together, these experiments indicated that MGMT protects from toxicity and mutagenicity induced by acrolein but not PM. Consistent with a role for MGMT in cyclophosphamide resistance, Friedman et al. [42] reported incubation of purified recombinant MGMT with DNA previously reacted with 4-HC or acrolein, but not PM, resulted in decreased residual MGMT activity levels, suggesting that acrolein produces a DNA adduct that MGMT recognizes and repairs. Additionally, Preuss et al. [86] showed that MGMT proficient cells were protected against sister chromatid exchange induction, compared to MGMT deficient cells, following microsomally activated cyclophosphamide; however, this protection was only significant at higher doses of activated cyclophosphamide. Conversely, this same group found cells with high MGMT activity were not protected against cytotoxicity and sister chromatid exchanges induced by mafosfamide, an activated form of cyclophosphamide that produces mesna in addition to PM and acrolein [86]. The discrepancy between the two studies could possibly be that mafosfamide additionally produces mesna and reaction of mesna with acrolein would reduce the amount of acrolein available for reaction with DNA. These studies suggest that some portion of the cytotoxicity and mutagenicity induced by cyclophosphamide is due to acrolein and the presence of MGMT may protect from that metabolite.

Proposed mechanism for role of MGMT in protecting from cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide-induced biological effects

The mechanism by which MGMT protects against acrolein is not understood. As MGMT is a DNA repair protein, MGMT could be recognizing and repairing an acrolein-induced DNA adduct. Acrolein has been shown to result in the cyclic adducts on guanine and MGMT may be involved in their removal; however, as described above, these adducts do not involve the O6-position of guanine and, therefore, are not classic substrates for MGMT. A possibility is that acrolein may react at the O6-position of guanine, producing an O6-propyl aldehyde moiety (O-CH2CH2CHO) or a hemiacetal (O-CH(OH)CH=CH2), as suggested in Friedman et al. [42]. MGMT would most likely recognize and repair these potential adducts.

Acrolein is a highly reactive molecule and has been shown to react directly with nucleophilic sites in glutathione, mesna and other thiols such as cysteine containing proteins [87]; therefore, direct reaction of the acceptor site cysteine residue of MGMT with acrolein, i.e. scavenging, is a reasonable possibility particularly since the Cys145 acceptor site of MGMT has a very low pKa (4–5) and is very reactive [88]. MGMT activity levels are reduced in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients receiving cyclophosphamide treatment [89]. In addition, MGMT activity in cell lysates is reduced 60% following exposure to acrolein (although this was observed at concentrations greater than 3-fold above physiological concentrations of acrolein) [90]. Furthermore, purified recombinant MGMT incubated with increasing concentrations of acrolein for 2 h results in a dose dependent decrease in residual MGMT activity [89]. Approximately 60% and 10% MGMT activity remained following incubation with physiological achievable concentrations of 10 and 100 μM acrolein, respectively [89]. These studies suggest that acrolein can lead to a reduction in MGMT activity likely by direct reaction with MGMT; however, whether direct reaction of acrolein with MGMT is a mechanism by which MGMT protects cells from acrolein toxicity has not been examined. In studies presented below, we determined whether direct reaction of MGMT with acrolein is the likely mechanism.

MGMT protects from acrolein and CAA toxicity in vitro

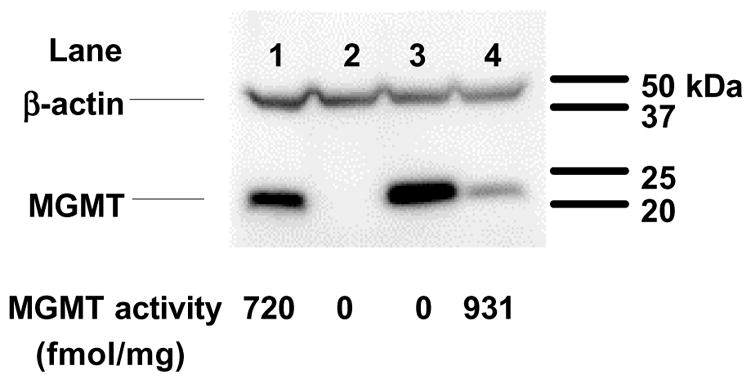

To determine whether CAA and/or acrolein reacted directly with the active site cysteine of MGMT, we treated CHO cells expressing an MGMT mutant containing an alteration at a crucial amino acid required for DNA binding, MGMTR128A [91]. MGMTR128A has > 1,000-fold reduced repair activity, compared to wtMGMT, towards a methylated DNA substrate, while retaining its functional active site and the capacity to react with BG [91,92]. Due to the fact that MGMTR128A lacks the ability to repair O6-alkyguanine DNA lesions, we probed the transfected lines with MGMT monoclonal antibody to verify the presence of MGMT protein (Figure 1). MGMT protein was detected in wtMGMT and MGMTR128A transfected cells, while MGMT could not be detected in 50 μg of whole cell lysate from pcDNA3 (vector). MGMT activity (as measured using a methylated DNAsubstrate) was observed in wtMGMT transfected cells (931 fmol/mg total protein) while activity in CHO cells transfected with vector or MGMTR128A were below detectable levels (Figure 1). Thus, MGMTR128A expressed protein was unable to repair methyl groups from O6-methylguanine within a DNA substrate.

Figure 1. MGMT expression and activity in transfected CHO lines.

MGMT protein expression was determined on 50 μg of whole cell lysates prepared from transfected CHO lines via Western blot analysis. Lane 1, HT29; lane 2, CHO-pcDNA3; lane 3, CHO-MGMTR128A; lane 4, CHO-wtMGMT. MGMT activity (fmol/mg total protein) was also determined on whole cell lysates. Lysates from HT29 cells were used as positive controls.

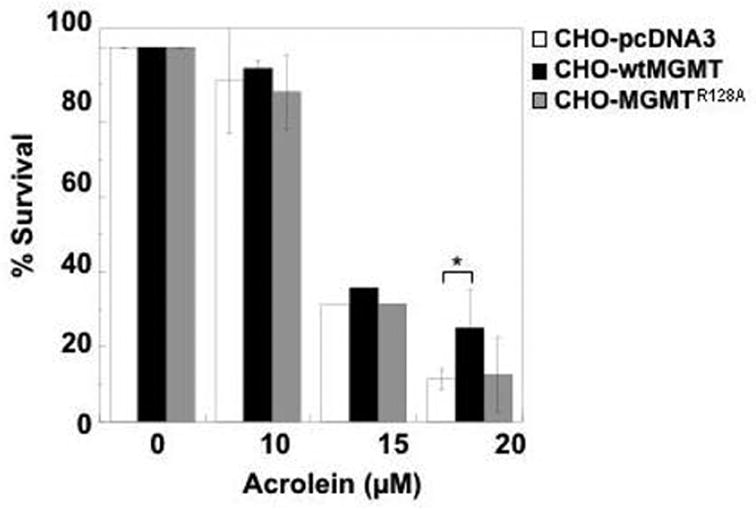

Using a colony-forming assay, we determined the ability of wtMGMT and MGMTR128A to protect from increasing physiological levels of acrolein. As seen in Figure 2, it was confirmed that wtMGMT provides significant protection from acrolein-induced cytotoxicity at 20 μM compared to vector expressing cells (p < 0.05). At this dose, the percentage of cell survival of wtMGMT cells was 25% compared to 11% in pcDNA3 cells. This is consistent with previously published results [45]. To determine whether DNA binding of MGMT is required for this protection, cytotoxicity assays were also conducted on CHO cells expressing MGMTR128A. Percent cell survival in MGMTR128A at 20 μM acrolein (12.5%) was similar to that observed in vector expressing cells (Figure 2). While wtMGMT expressing cells appear slightly protected at 10 and 15 μM acrolein, this increase in percent survival is not statistically significant from CHO cells expressing pcDNA3 or MGMTR128A.

Figure 2. Effect of MGMT and MGMTR128A on cytotoxicity induced by acrolein.

CHO lines transfected with pcDNA3, MGMTR128A, or wtMGMT were treated with acrolein in serum-free media for 4 h. Media was replaced with media containing serum. After 16 h, cytotoxicity was measured as colony-forming ability 9–12 days after treatment. The data represents the mean of three or more separate experiments (except for cytotoxicity determined at 15 μM). Bars are standard deviation. * indicates p < 0.05.

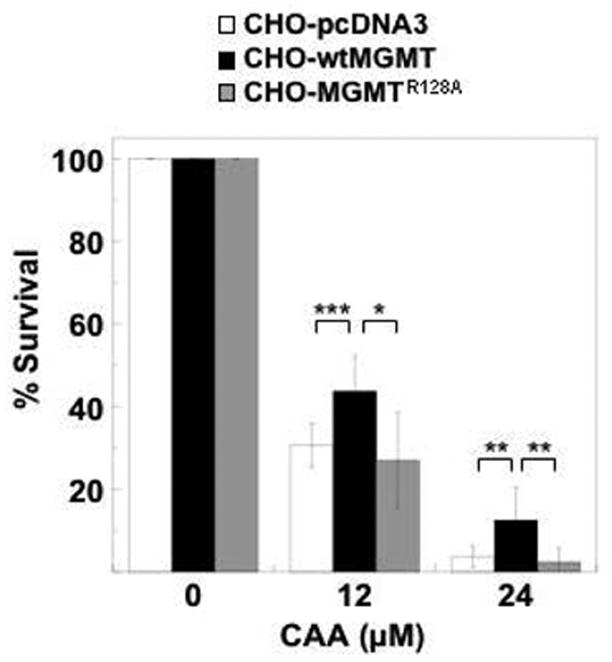

We also determined the ability of wtMGMT and MGMTR128A to protect from cytotoxicity induced by CAA. Doses of CAA used have been observed physiologically [57]. Following exposure of cells to 12 μM CAA, percent survival was significantly greater in wtMGMT expressing cells (44%) compared to MGMTR128A (27%) and pcDNA3 (31%) expressing cells (p < 0.03 and p < 0.003 when wtMGMT was compared to MGMTR128A and pcDNA3, respectively) (Figure 3). Percent survival of CHO cells expressing wtMGMT (13%) following treatment with 24 μM CAA was also significantly higher compared to survival in MGMTR128A (2%) and pcDNA3 (4%) (both p < 0.01). These results are the first to demonstrate that MGMT protects against CAA toxicity in vitro.

Figure 3. Effect of MGMT and MGMTR128A on cytotoxicity induced by CAA.

CHO lines transfected with pcDNA3, MGMTR128A, or wtMGMT were treated with 12 or 24 μM CAA in serum-free media. After 4 h drug incubation, the media was replaced with media containing serum. After 16 h, cytotoxicity was measured as colony -forming ability 9–12 days after treatment. The data represents the mean of three or more separate experiments. Bars are standard deviation. ***, ** and * indicate p < 0.003, p < 0.01 and p < 0.03, respectively.

Our results show survival of CHO-MGMTR128A cells was similar to vector expressing cells following exposure to acrolein or CAA, demonstrating that DNA binding of MGMT is required to protect against both metabolites. This is also suggestive that the mechanism by which MGMT provides cytotoxic protection is not via a scavenging mechanism. Therefore, the most likely explanation is that MGMT is protecting against acrolein/CAA cytotoxicity by recognizing and repairing a DNA adduct(s). Whether this acrolein or CAA adduct recognized by MGMT is an O6-guanine adduct, a previously reported N-alkylguanine adduct or a yet to be identified DNA adduct is not known. Regardless, these data support a role for MGMT in protecting from acrolein- and CAA-induced cytotoxicity.

The ability of MGMT to protect from CAA has clinical implications, as CAA is associated with neuro- and nephrotoxicity observed following exposure to ifosfamide [57–60]. CAA is produced to a much greater extent following treatment with ifosfamide as compared to cyclophosphamide, as up to 50% of ifosfamide undergoes N-dechloroethylation to produce CAA. Our results are the first to suggest that MGMT may protect against neuro- and nephrotoxicity following ifosfamide treatment. There is a report that CAA may contribute to the antitumor effects of ifosfamide in xenograft models [93]; therefore, MGMT may also play a role in resistance against ifosfamide therapy by reducing the contribution of CAA to the antitumor effect of ifosfamide. Whether ifosfamide would result in greater antitumor effect, enhance unwanted side effects, or both, in the absence of MGMT is not yet clear.

Toxicity of cyclophosphamide, acrolein and CAA in Mgmt −/− mice

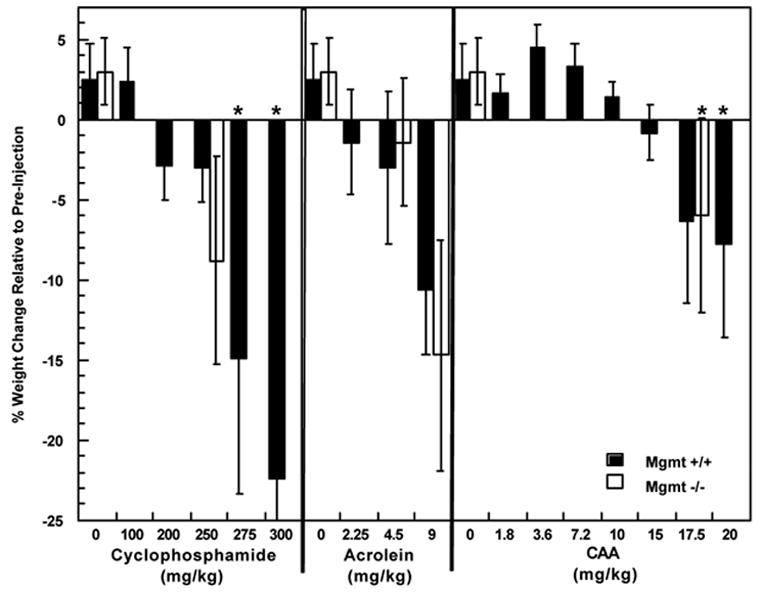

Studies presented previously and here suggest that MGMT protects against toxic lesions introduced by acrolein as well as CAA in cells. We expanded our studies to determine whether MGMT deficiency results in increased toxicities and death following cyclophosphamide, acrolein or CAA in mice. Mgmt −/− mice were not more sensitive to death caused by cyclophosphamide compared to wild type mice [94]. This result was not entirely unexpected as the majority of the toxicity associated with cyclophosphamide has been attributed to PM and we showed previously that the cytotoxicity of PM in vitro was unaffected by MGMT activity [45]. Prior to the work described herein, the role of MGMT in protecting against toxicity induced by acrolein and CAA in Mgmt −/− mice had not been determined. Thus, we determined the toxic effects of the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of acrolein and CAA (determined in Mgmt +/+) in Mgmt −/− mice. The toxic effects of cyclophosphamide, acrolein or CAA, as determined by weight change and animal death, were similar in Mgmt +/+ and Mgmt −/− mice (Figure 4). This is in contrast to the dramatic dose reductions required following methylating agents (streptozocin and temozolomide) and the chloroethylating agent BCNU in Mgmt −/− mice compared to Mgmt +/+ mice [95]. These data suggest that MGMT deficiency does not result in an increase in acute cyclophosphamide related toxicities and possibly indicates that MGMT expression does not greatly impact the toxicities associated with cyclophosphamide.

Figure 4. Weight change and deaths in Mgmt +/+ and −/− mice within 14 days following a single intraperitoneal injection with vehicle (0.9% NaCl), cyclophosphamide, acrolein or CAA.

Each bar repres ents mean weight change relative to pre-injection for at least 3 mice/group. *Represents death(s) in a treatment group, specifically, 1/6 and 4/6 Mgmt +/+ mice died in the 275 and 300 mg/kg cyclophosphamide group, respectively as well as 2/7 and 1/8 mice died in Mgmt +/+ and Mgmt −/− mice, respectively, treated with 20 mg/kg CAA.

Conclusion

The role of MGMT in cyclophosphamide antitumor effect and toxicity has remained elusive. Clinical studies that suggest a role for MGMT have included multiple drug regimens, making it difficult to deduce the role of MGMT in response to cyclophosphamide treatment. In the current studies performed in cell culture, we establish that MGMT significantly protects against CAA-induced cytotoxicity and confirm that MGMT protects from acrolein-induced cytotoxicity. We also present data that shows the importance of DNA binding of MGMT in providing protection against these metabolites. These results suggest that scavenging of acrolein or CAA by MGMT is not a likely mechanism by which MGMT protects cells, a possibility that had not been ruled out until now. Interestingly, MGMT deficiency does not result in a significant increase in toxicities in vivo, as the MTD of cyclophosphamide, acrolein or CAA were essentially equivalent in Mgmt +/+ and Mgmt −/− mice, suggesting that the role of MGMT in vivo may be less important. Other mechanisms of resistance to cyclophosphamide, such as high levels of aldehyde dehydrogenase, glutathione levels and DNA repair mechanisms other than MGMT are current targets of manipulation to reduce tumor resistance to cyclophosphamide and other oxazaphosphorines [4].

Acknowledgments

We thank Leona D. Samson (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) for her generous gift of the Mgmt −/− mice and Shannon Delaney for help on the figures.

This work was supported in part by Public Health Service Grants CA081485 (M.E.D.), CA016783 (S.M.L.) and CA018137 (A.E.P.) and CA071976 (A.E.P.), the University of Chicago’s Environmental Biology Training Grant, NIH NCI 5T32 CA09273 (R.J.H.) and Graduate Training Program in Cancer Biology NIH NCI 5T32 CA09594 (R.J.H).

Abbreviations

- BCNU

1,3-bis(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea

- MGMT

O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase

- PM

phosphoramide mustard

- IPM

isophosphoramide mustard

- CAA

chloroacetaldehyde

- 4-HC

4-hydroperoxycyclophosphamide

- 4-HI

4-hydroperoxyifosfamide

- 4-HDC

4-hydroperoxydidechlorocyclophosphamide

- MTD

maximum tolerated dose

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kaina B. Mechanisms and consequences of methylating agent-induced SCEs and chromosomal aberrations: a long road traveled and still a far way to go. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2004;104:77–86. doi: 10.1159/000077469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies SM. Therapy-related leukemia associated with alkylating agents. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2001;36:536–540. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wiencke JK, Wiemels J. Genotoxicity of 1,3-bis(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea (BCNU) Mutat Res. 1995;339:91–119. doi: 10.1016/0165-1110(95)90005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang J, Tian Q, Chan SY, Duan W, Zhou S. Insights into oxazaphosphorine resistance and possible approaches to its circumvention. Drug Resist Updat. 2005;8:271–297. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hilton J. Deoxyribonucleic acid crosslinking by 4-hydroperoxycyclophosphamide in cyclophosphamide-sensitive and -resistant L1210 cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 1984;33:1867–1872. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(84)90541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kohn KW. Interstrand cross-linking of DNA by 1,3-bis(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea and other 1-(2-haloethyl)-1-nitrosoureas. Cancer Res. 1977;37:1450–1454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pegg AE. Repair of O6-alkylguanine by alkyltransferases. Mutat Res. 2000;462:83–100. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(00)00017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pegg AE, Dolan ME, Moschel RC. Structure, function, and inhibition of O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1995;51:167–223. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60879-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daniels DS, Mol CD, Arvai AS, Kanugula S, Pegg AE, Tainer JA. Active and alkylated human AGT structures: a novel zinc site, inhibitor and extrahelical base binding. Embo J. 2000;19:1719–1730. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.7.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oh HK, Teo AK, Ali RB, Lim A, Ayi TC, Yarosh DB, Li BF. Conformational change in human DNA repair enzyme O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase upon alkylation of its active site by SN1 (indirect-acting) and SN2 (direct-acting) alkylating agents: breaking a “salt-link”. Biochemistry. 1996;35:12259–12266. doi: 10.1021/bi9603635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Srivenugopal KS, Yuan XH, Friedman HS, Ali-Osman F. Ubiquitination-dependent proteolysis of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase in human and murine tumor cells following inactivation with O6-benzylguanine or 1,3-bis(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea. Biochemistry. 1996;35:1328–1334. doi: 10.1021/bi9518205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Citron M, Graver M, Schoenhaus M, Chen S, Decker R, Kleynerman L, Kahn LB, White A, Fornace AJ, Jr, Yarosh D. Detection of messenger RNA from O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase gene MGMT in human normal and tumor tissues. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1992;84:337–340. doi: 10.1093/jnci/84.5.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerson SL, Miller K, Berger NA. O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase activity in human myeloid cells. J Clin Invest. 1985;76:2106–2114. doi: 10.1172/JCI112215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerson SL, Phillips W, Kastan M, Dumenco LL, Donovan C. Human CD34+ hematopoietic progenitors have low, cytokine-unresponsive O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase and are sensitive to O6-benzylguanine plus BCNU. Blood. 1996;88:1649–1655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pegg AE. Mammalian O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase: regulation and importance in response to alkylating carcinogenic and therapeutic agents. Cancer Res. 1990;50:6119–6129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hongeng S, Brent TP, Sanford RA, Li H, Kun LE, Heideman RL. O6-Methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase protein levels in pediatric brain tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3:2459–2463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silber JR, Mueller BA, Ewers TG, Berger MS. Comparison of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase activity in brain tumors and adjacent normal brain. Cancer Res. 1993;53:3416–3420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Belanich M, Pastor M, Randall T, Guerra D, Kibitel J, Alas L, Li B, Citron M, Wasserman P, White A, Eyre H, Jaeckle K, Schulman S, Rector D, Prados M, Coons S, Shapiro W, Yarosh D. Retrospective study of the correlation between the DNA repair protein alkyltransferase and survival of brain tumor patients treated with carmustine. Cancer Res. 1996;56:783–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gerson SL. Clinical relevance of MGMT in the treatment of cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2388–2399. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.06.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hotta T, Saito Y, Fujita H, Mikami T, Kurisu K, Kiya K, Uozumi T, Isowa G, Ishizaki K, Ikenaga M. O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase activity of human malignant glioma and its clinical implications. J Neurooncol. 1994;21:135–140. doi: 10.1007/BF01052897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dolan ME, Mitchell RB, Mummert C, Moschel RC, Pegg AE. Effect of O6-benzylguanine analogues on sensitivity of human tumor cells to the cytotoxic effects of alkylating agents. Cancer Res. 1991;51:3367–3372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dolan ME, Moschel RC, Pegg AE. Depletion of mammalian O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase activity by O6-benzylguanine provides a means to evaluate the role of this protein in protection against carcinogenic and therapeutic alkylating agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:5368–5372. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.14.5368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dolan ME, Pegg AE, Moschel RC, Grindey GB. Effect of O6-benzylguanine on the sensitivity of human colon tumor xenografts to 1,3-bis(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea (BCNU) Biochem Pharmacol. 1993;46:285–290. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90416-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McElhinney RS, Donnelly DJ, McCormick JE, Kelly J, Watson AJ, Rafferty JA, Elder RH, Middleton MR, Willington MA, McMurry TB, Margison GP. Inactivation of O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase. 1. Novel O6-(hetarylmethyl)guanines having basic rings in the side chain. J Med Chem. 1998;41:5265–5271. doi: 10.1021/jm9708644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barvaux VA, Lorigan P, Ranson M, Gillum AM, McElhinney RS, McMurry TB, Margison GP. Sensitization of a human ovarian cancer cell line to temozolomide by simultaneous attenuation of the Bcl-2 antiapoptotic protein and DNA repair by O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:1215–1220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barvaux VA, Ranson M, Brown R, McElhinney RS, McMurry TB, Margison GP. Dual repair modulation reverses Temozolomide resistance in vitro. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:123–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clemons M, Kelly J, Watson AJ, Howell A, McElhinney RS, McMurry TB, Margison GP. O6-(4-bromothenyl)guanine reverses temozolomide resistance in human breast tumour MCF-7 cells and xenografts. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:1152–1156. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turriziani M, Caporaso P, Bonmassar L, Buccisano F, Amadori S, Venditti A, Cantonetti M, D’Atri S, Bonmassar E. O6-(4-bromothenyl)guanine (PaTrin-2), a novel inhibitor of O6-alkylguanine DNA alkyl-transferase, increases the inhibitory activity of temozolomide against human acute leukaemia cells in vitro. Pharmacol Res. 2006;53:317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colvin OM. An overview of cyclophosphamide development and clinical applications. Curr Pharm Des. 1999;5:555–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fraiser LH, Kanekal S, Kehrer JP. Cyclophosphamide toxicity. Characterising and avoiding the problem. Drugs. 1991;42:781–795. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199142050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ludeman SM. The chemistry of the metabolites of cyclophosphamide. Curr Pharm Des. 1999;5:627–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malet-Martino M, Gilard V, Martino R. The analysis of cyclophosphamide and its metabolites. Curr Pharm Des. 1999;5:561–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen SS, Citron M, Spiegel G, Yarosh D. O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase in ovarian malignancy and its correlation with postoperative response to chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 1994;52:172–174. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1994.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Codegoni AM, Broggini M, Pitelli MR, Pantarotto M, Torri V, Mangioni C, D’Incalci M. Expression of genes of potential importance in the response to chemotherapy and DNA repair in patients with ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;65:130–137. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.4609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hengstler JG, Tanner B, Moller L, Meinert R, Kaina B. Activity of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase in relation to p53 status and therapeutic response in ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 1999;84:388–395. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990820)84:4<388::aid-ijc10>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Esteller M, Gaidano G, Goodman SN, Zagonel V, Capello D, Botto B, Rossi D, Gloghini A, Vitolo U, Carbone A, Baylin SB, Herman JG. Hypermethylation of the DNA repair gene O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase and survival of patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:26–32. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al-Kuraya K, Narayanappa R, Siraj AK, Al-Dayel F, Ezzat A, El Solh H, Al-Jommah N, Sauter G, Simon R. High frequency and strong prognostic relevance of O6-methylguanine DNA methyltransferase silencing in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas from the Middle East. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:742–748. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohno T, Hiraga J, Ohashi H, Sugisaki C, Li E, Asano H, Ito T, Nagai H, Yamashita Y, Mori N, Kinoshita T, Naoe T. Loss of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase protein expression is a favorable prognostic marker in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Int J Hematol. 2006;83:341–347. doi: 10.1532/IJH97.05182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cayre A, Penault-Llorca F, De Latour M, Rolhion C, Feillel V, Ferriere JP, Kwiatkowski F, Finat-Duclos F, Verrelle P. O6-methylguanine-DNA methyl transferase gene expression and prognosis in breast carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2002;21:1125–1131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Osanai T, Takagi Y, Toriya Y, Nakagawa T, Aruga T, Iida S, Uetake H, Sugihara K. Inverse correlation between the expression of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyl transferase (MGMT) and p53 in breast cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2005;35:121–125. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyi036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.D’Incalci M, Bonfanti M, Pifferi A, Mascellani E, Tagliabue G, Berger D, Fiebig HH. The antitumour activity of alkylating agents is not correlated with the levels of glutathione, glutathione transferase and O6-alkylguanine-DNA-alkyltransferase of human tumour xenografts. EORTC SPG and PAMM Groups. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:1749–1755. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00191-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Friedman HS, Pegg AE, Johnson SP, Loktionova NA, Dolan ME, Modrich P, Moschel RC, Struck R, Brent TP, Ludeman S, Bullock N, Kilborn C, Keir S, Dong Q, Bigner DD, Colvin OM. Modulation of cyclophosphamide activity by O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1999;43:80–85. doi: 10.1007/s002800050866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mattern J, Eichhorn U, Kaina B, Volm M. O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase activity and sensitivity to cyclophosphamide and cisplatin in human lung tumor xenografts. Int J Cancer. 1998;77:919–922. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980911)77:6<919::aid-ijc20>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cai Y, Ludeman SM, Wilson LR, Chung AB, Dolan ME. Effect of O6-benzylguanine on nitrogen mustard-induced toxicity, apoptosis, and mutagenicity in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2001;1:21–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cai Y, Wu MH, Ludeman SM, Grdina DJ, Dolan ME. Role of O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase in protecting against cyclophosphamide-induced toxicity and mutagenicity. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3059–3063. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cai Y, Wu MH, Xu-Welliver M, Pegg AE, Ludeman SM, Dolan ME. Effect of O6-benzylguanine on alkylating agent-induced toxicity and mutagenicity. In Chinese hamster ovary cells expressing wild-type and mutant O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferases. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5464–5469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith SM, Ludeman SM, Wilson LR, Springer JB, Gandhi MC, Dolan ME. Selective enhancement of ifosfamide-induced toxicity in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2003;52:291–302. doi: 10.1007/s00280-003-0672-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang J, Tian Q, Yung Chan S, Chuen Li S, Zhou S, Duan W, Zhu YZ. Metabolism and transport of oxazaphosphorines and the clinical implications. Drug Metab Rev. 2005;37:611–703. doi: 10.1080/03602530500364023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dong Q, Barsky D, Colvin ME, Melius CF, Ludeman SM, Moravek JF, Colvin OM, Bigner DD, Modrich P, Friedman HS. A structural basis for a phosphoramide mustard-induced DNA interstrand cross-link at 5′-d(GAC) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:12170–12174. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.26.12170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Struck RF, Davis RL, Jr, Berardini MD, Loechler EL. DNA guanine-guanine crosslinking sequence specificity of isophosphoramide mustard, the alkylating metabolite of the clinical antitumor agent ifosfamide. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2000;45:59–62. doi: 10.1007/pl00006744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cox PJ. Cyclophosphamide cystitis--identification of acrolein as the causative agent. Biochem Pharmacol. 1979;28:2045–2049. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(79)90222-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brock N. The development of mesna for the inhibition of urotoxic side effects of cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, and other oxazaphosphorine cytostatics. Recent Results Cancer Res. 1980;74:270–278. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-81488-4_32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takamoto S, Sakura N, Namera A, Yashiki M. Monitoring of urinary acrolein concentration in patients receiving cyclophosphamide and ifosphamide. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2004;806:59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brock N, Pohl J, Stekar J, Scheef W. Studies on the urotoxicity of oxazaphosphorine cytostatics and its prevention--III. Profile of action of sodium 2-mercaptoethane sulfonate (mesna) Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1982;18:1377–1387. doi: 10.1016/0277-5379(82)90143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ormstad K, Orrenius S, Lastbom T, Uehara N, Pohl J, Stekar J, Brock N. Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of sodium 2-mercaptoethanesulfonate in the rat. Cancer Res. 1983;43:333–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Batista CK, Mota JM, Souza ML, Leitao BT, Souza MH, Brito GA, Cunha FQ, Ribeiro RA. Amifostine and glutathione prevent ifosfamide- and acrolein-induced hemorrhagic cystitis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006 doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0248-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bruggemann SK, Kisro J, Wagner T. Ifosfamide cytotoxicity on human tumor and renal cells: role of chloroacetaldehyde in comparison to 4-hydroxyifosfamide. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2676–2680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goren MP, Wright RK, Pratt CB, Pell FE. Dechloroethylation of ifosfamide and neurotoxicity. Lancet. 1986;2:1219–1220. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)92227-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lewis LD, Meanwell CA. Ifosfamide pharmacokinetics and neurotoxicity. Lancet. 1990;335:175–176. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Skinner R, Sharkey IM, Pearson AD, Craft AW. Ifosfamide, mesna, and nephrotoxicity in children. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:173–190. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Williams ML, Wainer IW. Cyclophosphamide versus ifosfamide: to use ifosfamide or not to use, that is the three-dimensional question. Curr Pharm Des. 1999;5:665–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aleksa K, Halachmi N, Ito S, Koren G. A tubule cell model for ifosfamide nephrotoxicity. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2005;83:499–508. doi: 10.1139/y05-036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aleksa K, Matsell D, Krausz K, Gelboin H, Ito S, Koren G. Cytochrome P450 3A and 2B6 in the developing kidney: implications for ifosfamide nephrotoxicity. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20:872–885. doi: 10.1007/s00467-004-1807-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McCune JS, Risler LJ, Phillips BR, Thummel KE, Blough D, Shen DD. Contribution of CYP3A5 to hepatic and renal ifosfamide N-dechloroethylation. Drug Metab Dispos. 2005;33:1074–1081. doi: 10.1124/dmd.104.002279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Aleksa K, Ito S, Koren G. Renal-tubule metabolism of ifosfamide to the nephrotoxic chloroacetaldehyde: pharmacokinetic modeling for estimation of intracellular levels. J Lab Clin Med. 2004;143:159–162. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2003.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nicolao P, Giometto B. Neurological toxicity of ifosfamide. Oncology. 2003;65(Suppl 2):11–16. doi: 10.1159/000073352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aeschlimann C, Kupfer A, Schefer H, Cerny T. Comparative pharmacokinetics of oral and intravenous ifosfamide/mesna/methylene blue therapy. Drug Metab Dispos. 1998;26:883–890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pelgrims J, De Vos F, Van den Brande J, Schrijvers D, Prove A, Vermorken JB. Methylene blue in the treatment and prevention of ifosfamide-induced encephalopathy: report of 12 cases and a review of the literature. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:291–294. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.0917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schwerdt G, Gordjani N, Benesic A, Freudinger R, Wollny B, Kirchhoff A, Gekle M. Chloroacetaldehyde- and acrolein-induced death of human proximal tubule cells. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21:60–67. doi: 10.1007/s00467-005-2006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu XL, Chen K, Ye YP, Peng XY, Qian BC. Glutathione antagonized cyclophosphamide- and acrolein-induced cytotoxicity of PC3 cells and immunosuppressive actions in mice. Zhongguo Yao Li Xue Bao. 1999;20:643–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gamcsik MP, Dolan ME, Andersson BS, Murray D. Mechanisms of resistance to the toxicity of cyclophosphamide. Curr Pharm Des. 1999;5:587–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wu CC, Hsieh CW, Lai PH, Lin JB, Liu YC, Wung BS. Upregulation of endothelial heme oxygenase-1 expression through the activation of the JNK pathway by sublethal concentrations of acrolein. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2006;214:244–252. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu-Snyder P, McNally H, Shi R, Borgens RB. Acrolein-mediated mechanisms of neuronal death. J Neurosci Res. 2006;84:209–218. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Benesic A, Schwerdt G, Mildenberger S, Freudinger R, Gordjani N, Gekle M. Disturbed Ca2+-signaling by chloroacetaldehyde: a possible cause for chronic ifosfamide nephrotoxicity. Kidney Int. 2005;68:2029–2041. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Luo J, Shi R. Acrolein induces oxidative stress in brain mitochondria. Neurochem Int. 2005;46:243–252. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Uchida K. Current status of acrolein as a lipid peroxidation product. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 1999;9:109–113. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(99)00016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Misonou Y, Asahi M, Yokoe S, Miyoshi E, Taniguchi N. Acrolein produces nitric oxide through the elevation of intracellular calcium levels to induce apoptosis in human umbilical vein endothelial cells: implications for smoke angiopathy. Nitric Oxide. 2006;14:180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chung FL, Young R, Hecht SS. Formation of cyclic 1,N2-propanodeoxyguanosine adducts in DNA upon reaction with acrolein or crotonaldehyde. Cancer Res. 1984;44:990–995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Eder E, Hoffman C, Bastian H, Deininger C, Scheckenbach S. Molecular mechanisms of DNA damage initiated by alpha, beta-unsaturated carbonyl compounds as criteria for genotoxicity and mutagenicity. Environ Health Perspect. 1990;88:99–106. doi: 10.1289/ehp.908899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Dosanjh MK, Chenna A, Kim E, Fraenkel-Conrat H, Samson L, Singer B. All four known cyclic adducts formed in DNA by the vinyl chloride metabolite chloroacetaldehyde are released by a human DNA glycosylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:1024–1028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.3.1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Oesch F, Doerjer G. Detection of N2,3-ethanoguanine in DNA after treatment with chloroacetaldehyde in vitro. Carcinogenesis. 1982;3:663–665. doi: 10.1093/carcin/3.6.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dypbukt JM, Atzori L, Edman CC, Grafstrom RC. Thiol status and cytopathological effects of acrolein in normal and xeroderma pigmentosum skin fibroblasts. Carcinogenesis. 1993;14:975–980. doi: 10.1093/carcin/14.5.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gros L, Ishchenko AA, Saparbaev M. Enzymology of repair of etheno-adducts. Mutat Res. 2003;531:219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2003.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kisby GE, Lesselroth H, Olivas A, Samson L, Gold B, Tanaka K, Turker MS. Role of nucleotide- and base-excision repair in genotoxin-induced neuronal cell death. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:617–627. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Flowers JL, Ludeman SM, Gamcsik MP, Colvin OM, Shao KL, Boal JH, Springer JB, Adams DJ. Evidence for a role of chloroethylaziridine in the cytotoxicity of cyclophosphamide. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2000;45:335–344. doi: 10.1007/s002800050049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Preuss I, Thust R, Kaina B. Protective effect of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT) on the cytotoxic and recombinogenic activity of different antineoplastic drugs. Int J Cancer. 1996;65:506–512. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960208)65:4<506::AID-IJC19>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Links M, Lewis C. Chemoprotectants: a review of their clinical pharmacology and therapeutic efficacy. Drugs. 1999;57:293–308. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199957030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Guengerich FP, Fang Q, Liu L, Hachey DL, Pegg AE. O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase: low pKa and high reactivity of cysteine 145. Biochemistry. 2003;42:10965–10970. doi: 10.1021/bi034937z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lee SM, Crowther D, Scarffe JH, Dougal M, Elder RH, Rafferty JA, Margison GP. Cyclophosphamide decreases O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase activity in peripheral lymphocytes of patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation. Br J Cancer. 1992;66:331–336. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1992.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Krokan H, Grafstrom RC, Sundqvist K, Esterbauer H, Harris CC. Cytotoxicity, thiol depletion and inhibition of O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase by various aldehydes in cultured human bronchial fibroblasts. Carcinogenesis. 1985;6:1755–1759. doi: 10.1093/carcin/6.12.1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Loktionova NA, Xu-Welliver M, Crone TM, Kanugula S, Pegg AE. Protection of CHO cells by mutant forms of O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase from killing by 1,3-bis-(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea (BCNU) plus O6-benzylguanine or O6-benzyl-8-oxoguanine. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;58:237–244. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kanugula S, Goodtzova K, Edara S, Pegg AE. Alteration of arginine-128 to alanine abolishes the ability of human O6-alkylguanine-DNA alkyltransferase to repair methylated DNA but has no effect on its reaction with O6-benzylguanine. Biochemistry. 1995;34:7113–7119. doi: 10.1021/bi00021a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Borner K, Kisro J, Bruggemann SK, Hagenah W, Peters SO, Wagner T. Metabolism of ifosfamide to chloroacetaldehyde contributes to antitumor activity in vivo. Drug Metab Dispos. 2000;28:573–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shiraishi A, Sakumi K, Sekiguchi M. Increased susceptibility to chemotherapeutic alkylating agents of mice deficient in DNA repair methyltransferase. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1879–1883. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.10.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Glassner BJ, Weeda G, Allan JM, Broekhof JL, Carls NH, Donker I, Engelward BP, Hampson RJ, Hersmus R, Hickman MJ, Roth RB, Warren HB, Wu MM, Hoeijmakers JH, Samson LD. DNA repair methyltransferase (Mgmt) knockout mice are sensitive to the lethal effects of chemotherapeutic alkylating agents. Mutagenesis. 1999;14:339–347. doi: 10.1093/mutage/14.3.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]