Abstract

Membrane fusion during exocytosis requires that two initially distinct bilayers pass through a hemifused intermediate in which the proximal monolayers are shared. Passage through this intermediate is an essential step in the process of secretion, but is difficult to observe directly in vivo. Here we study membrane fusion in the sea urchin egg, in which thousands of homogenous cortical granules are associated with the plasma membrane prior to fertilization. Using fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP), we find that these granules are stably hemifused to the plasma membrane, sharing a cytoplasmic-facing monolayer. Furthermore, we find that the proteins implicated in the fusion process the vesicle-associated proteinsVAMP (synaptobrevin), synaptotagmin, and Rab3 – are each immobile within the granule membrane. Thus, these secretory granules are tethered to their target plasma membrane by a static, catalytic fusion complex that maintains a hemifused membrane intermediate.

Keywords: hemifusion, membrane, secretory vesicle

Introduction

Membrane fusion merges two phospholipid bilayers into one. This process is essential to eukaryotic cells and is utilized during vesicle trafficking between organelles, for secretion, and in cytokinesis. Membrane fusion requires significant free energy to surmount both the electrostatic repulsion of opposing membranes and the reorganization of phospholipids within the shared monolayer (Chernomordik and Kozlov, 2005; Kozlovsky and Kozlov, 2002). Enveloped viridae and eukaryotic cells alike use protein catalysts to overcome this energy barrier (Basanez, 2002). The most common eukaryotic catalysts are soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptors (SNARE), whose heterologous-assembly into a trans-complex is believed to contribute both the membrane deformation and the free energy necessary for fusion under physiological conditions (Basanez, 2002; Bentz, 2000; Jahn and Scheller, 2006; Sorensen et al., 2006).

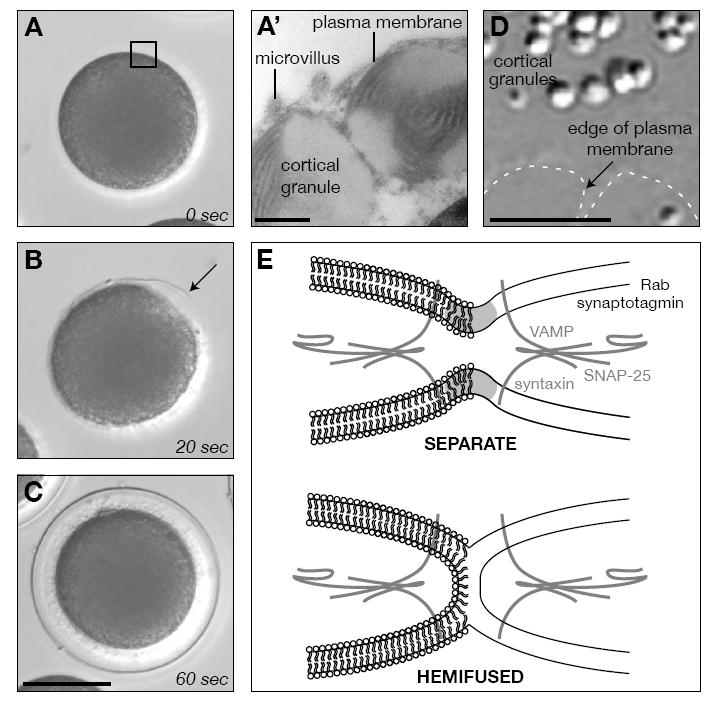

Three major events are required for SNARE-mediated exocytosis. (1) Secretory vesicles translocate to the plasma membrane, where (2) vesicle and target membrane SNARE proteins assemble in a calcium-dependent fashion into a ring of 3-15 ternary complexes at the future site of fusion (Hu et al., 2002; Jahn and Scheller, 2006). The assembly of this trans-SNARE complex destabilizes the membranes sufficiently to drive (3) membrane fusion through a hemifused intermediate – a structure whose proximal monolayers are shared via a low-energy stalk (FIG 1E) (Chernomordik and Kozlov, 2005; Kozlovsky and Kozlov, 2002; Zampighi et al., 2006). Any of these stages can be rate limiting in vivo (Han and Jackson, 2006; Jahn and Scheller, 2006; Kasson et al., 2006; Melia et al., 2006; Pobbati et al., 2006; Sorensen et al., 2006; Sudhof, 2004).

FIGURE 1. The sea urchin egg as a model for studying membrane fusion.

(A-C) Sequential snapshots of cortical granule exocytosis 0 (A), 20 (B), and 60 (C) seconds after fertilization. Note the polarized origin of secretion (arrow), originating at the site of sperm fusion. Scale bar equals 50μm. (A’) Detail of the egg cortical granules and their proximity to the plasma membrane. Scale bar equals 500 nm. (D) Differential interference contrast image of a cortical lawn preparation made from eggs. The edge of the plasma membrane is indicated (dashed line). Scale bar equals 5 μm. (E) Models of the membrane status of cortical granules at their closest proximity to the plasma membrane. Members of the SNARE complex used in this study are included for reference.

Exocytosis of a single vesicle is often completed in sub-milliseconds in vivo (Chernomordik and Kozlov, 2005; Sudhof, 2004), making it difficult to observe the intermediate fusion steps. Electron tomographic reconstruction of synaptic vesicles fixed at the active zone, a privileged region of the presynaptic membrane where fast-response secretory vesicles reside (Sudhof, 2004), show that the vesicles are hemifused to their target membrane (Zampighi et al., 2006). Live analysis of lipid dynamics and fusion processes in vivo and in vitro also supports the existence of a hemifused membrane intermediate, but such observations required alterations to the fusion machinery (Chernomordik and Kozlov, 2005; Xu et al., 2005; Zaitseva et al., 2005). Together, evidence for SNARE-dependent membrane fusion via a hemifused state is strong, but limited to fixed or perturbed systems.

The contents of over 15,000 secretory vesicles in the egg cortex are rapidly and synchronously exocytosed (FIG 1B) when sea urchin eggs are fertilized (Vacquier, 1975). These contents contribute to changes of the egg cell surface that are essential for the block to polyspermy, egg activation, and embryonic development (Wong and Wessel, 2006a). As in most animal oocytes, sea urchin cortical granules are synthesized throughout oogenesis (Laidlaw and Wessel, 1994; Wong and Wessel, 2006a) and are translocated to the cell cortex during the final phases of meiosis (Wessel et al., 2002), where they remain associated with the egg plasma membrane for weeks without premature fusion (Vacquier, 1975; Walker et al., 2005). The attachment of these cortical vesicles is so tight that SNARE-specific neurotoxins (Tahara et al., 1998), mechanical shearing (Crabb and Jackson, 1985), and centrifugal force (Wong and Wessel, 2006b) do not release the granules from the plasma membrane. Yet, in vitro cortical lawns (FIG 1D) – made by shearing eggs bound to glass slides – retain fusion-competent granules attached to the plasma membrane that behave as in the intact egg (Churchward et al., 2005; Crabb and Jackson, 1985; Vacquier, 1975).

Here, we used fluorescence recovery assays to test the mobility of both the vesicle-associated proteins and lipids of sea urchin cortical granules attached to the plasma membrane. We find immobile SNARE-associated vesicle proteins within the membrane, suggesting that recruitment of these catalytic factors to the site of membrane fusion is a slow process. Surprisingly, we also find secretory vesicle attached to the plasma membrane via stable hemifused membranes. We suggest that these two characteristics together contribute to the stability of vesicles tightly associated with their target membranes, in a state that sensitizes the cortical granules for rapid, synchronous exocytosis following calcium release at fertilization.

Results

Immobility of SNARE-associated cortical granule proteins

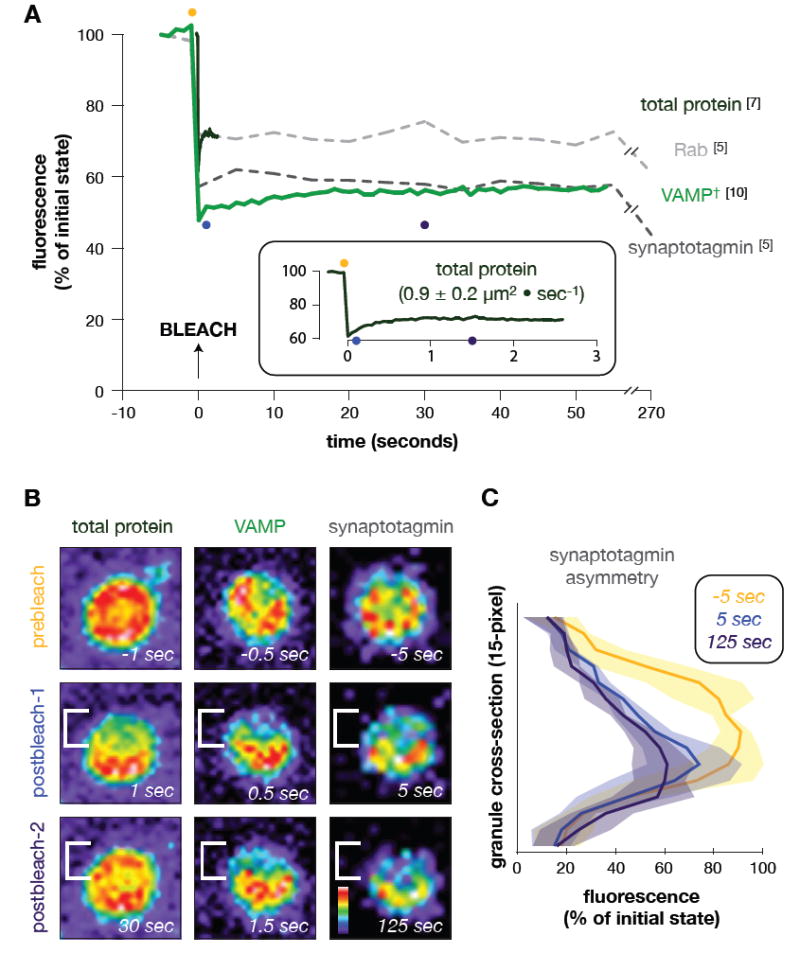

We first analyzed the mobility of proteins involved with exocytosis and associated with secretory vesicles (Conner et al., 1997). Populations ofvesicle-associated membrane protein (VAMP/synaptobrevin), Rab3, and the calcium sensor, synaptotagmin, specifically accumulate in the membrane of the cortical granule (Conner et al., 1997; Leguia et al., 2006; Sudhof, 2004). These proteins were labeled with fluorophore-conjugated Fabs in lawn preparations (Vacquier, 1975), and then a region comprising one-half of an attached granule was photobleached to assess protein mobility (FIG 2). All three Fab-labeled proteins were found to be essentially immobile within the plane of the vesicle membrane, whereas the general protein population was found to be highly mobile (72 ± 16% recovery at 0.9 ± 0.2 μm2 sec-1) (FIG 2). This differential protein mobility suggests that stable vesicle attachment to target membranes requires a limited, local population of interacting SNARE-associated proteins rather than active recruitment of such catalysts to an attachment site.

FIGURE 2. Cytoplasmically exposed, vesicle-associated proteins are immobile in the plane of the vesicle membrane.

(A) Mean fluorescence recovery curves are shown for vesicle protein (AF488; reagent labeled all free amines) and Fab-labeled vesicle-associated proteins (Rab, VAMP/synaptobrevin, synaptotagmin) into one half of a bleached cortical granule attached to cortical lawns (see FIG 1D). Decay in fluorescence during the recovery period (Rab, synaptotagmin fluorescence at 270 sec) is a consequence of sample photobleaching during the time course. †VAMP/synaptobrevin recovery is calculated to be nearly zero, with a diffusion rate of (0.006 ± 0.008)μm2 sec-1. (Inset) Magnification of mean recovery of total protein associated with cortical granules. Diffusion rate of mobile protein population is listed. Note that total protein on unattached granules do not redistribute, and are thus immobile when attached to charged glass (data not shown). The time of bleaching was arbitrarily set as the origin of the time axis. All time-series data per replicate were normalized between the background (0%) and maximum fluorescence (100%) of the first pre-bleach frame. Numbers in brackets equal replicates per Fab. Colored dots correspond with images in ‘B’. (B) Snapshots of representative time-series using total protein labeling (left), anti-VAMP/synaptobrevin (middle), and anti-synaptotagmin Fabs (right). Prebleach and two post-bleach images are shown, with corresponding time during the recovery. The bleach area is bracketed to emphasize any retention of post-bleach asymmetry over time. Images are pseudocolored according to the colorized scale, showing low (black) to high (white)fluorescenceintensity. (C) Fluorescence intensity plots averaged across synaptotagmin-probed granules. Per replicate, intensity totals were calculated for each pixel of a line drawn perpendicular to the bleach boundary (snapshot y-axis; see ‘B’), summing the values for each pixel parallel to the bleach boundary (snapshot x-axis; see ‘B’). Data represent the mean (line) and standard deviation (shading) across all anti-synaptotagmin replicates. Curves correspond to snapshot images in ‘B’. Total width of each granule is 15 pixels (y-axis); fluorescence intensity is normalized to the first prebleach data set, as in ‘A’.

Lipid mobility

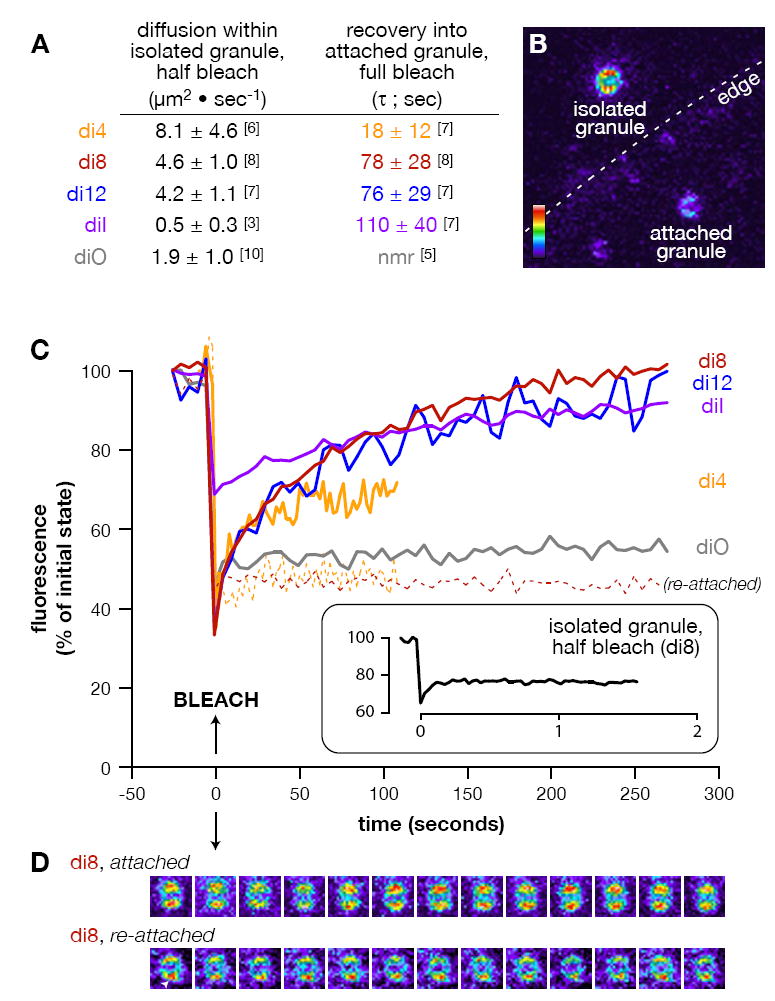

In contrast to the immobility of VAMP/synaptobrevin, Rab3, and synaptotagmin, the lipid component of the cortical granule membrane is fluid. Overall, diffusion of lipid probes is independent of aliphatic chain length or head group, as reflected in probe diffusion rates measured within the membrane of isolated granules (FIG 3A) and the plasma membrane (e.g. di-4-ANEPPS diffuses at 0.68 ± 0.11 μm2sec-1 while di-8-ANEPPS diffuses at 0.84 ± 0.11 μm2sec-1; pT-test=0.02). Unexpectedly, diffusion in the granule membrane is at least 5-fold faster than in the plasma membrane (for di-8-ANEPPS, pT-test=10-9). Following vesicle fusion, however, the probe mobility in the now heterogenous membrane equals the rate in the plasma membrane, as exemplified by di-8-ANEPPS mobility in calcium-treated lawns (calcium-fused rate is 0.80 ± 0.18 μm2sec-1while the untreated rate is 0.84 ± 0.11 μm2 sec-1; pT-test=0.56). Thus, the diffusion rate of lipid probes in these granules could be affected by membrane geometry (see FIG 1) and/or lipid composition (Churchward et al., 2005).

FIGURE 3. Cortical granules are hemifused to the plasma membrane.

(A) List of specific diffusion rates and recovery times calculated for the 5 lipid probes used (see Methods). Numbers in brackets equal replicates per treatment. “nmr” = no measurable recovery. (B) Representative pseudocolor image of the types of vesicles analyzed. Attached and isolated cortical granules are found in the background image, with the edge of the plasma membrane indicated (dashed line). Colorized scale indicates lowest (black) to highest (white) fluorescence intensity. (C) Mean fluorescence recovery curves are shown for diffusion of lipid probes into fully bleached, attached cortical granules (solid lines) and re-associated cortical granules (dashed lines; di-4-ANEPPS n=3, di-8-ANEPPS n=4). (Inset) Mean recovery of di-8-ANEPPS in isolated, half-bleached granules. The time of bleaching was arbitrarily set as the origin of the time axis. All time-series data per replicate were normalized between the background (0%) and maximum fluorescence (100%) of the first pre-bleach frame. (D) Sequential snapshots from a representative fully bleached, attached and re-attached cortical granule stained with di-8-ANEPPS. Images are pseudocolored (as in ‘A’), with each separated from its predecessor by 25 seconds within the time-series. Arrowhead indicates a protrusion from a re-attached granule indicative of a hemifusion stalk (Zampighi et al., 2006). None of the preparations contained free probe in the media that could account for the recovery (see Methods).

Surprisingly, cortical granules attached to the plasma membrane are hemifused. We tested fluorescence recovery of lipid markers after photobleaching an entire vesicle bound to the plasma membrane (attached granule; FIG 3B). If the membranes remain separate, no probe will diffuse into the bleached granule membrane. Conversely, a continuous monolayer indicative of a hemifused intermediate allows probe to recover into the bleached area since the lipids can freely diffuse from the unbleached plasma membrane (FIG 1E). Following complete photobleaching of individual vesicles, we generally observed fluorescence recover into the same granule membrane (FIG 3C-D). In contrast, mechanically detached vesicles allowed to stably re-associate with the plasma membrane did not regain fluorescence following photobleaching, as exhibited by the negligible (20 ± 11%) and immeasurable redistribution observed for di-4-ANEPPS and di-8-ANEPPS, respectively (FIG 3C). Results from these experiments strongly suggest that probe diffusion across an aqueous buffer alone cannot account for the extent of the probe redistribution observed in endogenously attached granules. These results are also consistent with the low aqueous solubility of the lipid probes – particularly those with longer aliphatic chains (e.g. di-8-ANEPPS, di-12-ANEPPS, and the C-18 probes diI and diO). Thus, probe redistribution into attached vesicles following photobleaching is a consequence of hemifused membranes.

Mean lipid probe redistribution into attached, hemifused vesicles ranged from 53±26% (di-4-ANEPPS) to 101±12% (di-8-ANEPPS), and was reproducible on individual granules following successive photobleaches (data not shown). The lower percentage redistribution of di-4-ANEPPS may be a consequence of its tendency to slowly flip into the non-redistributing lumenal monolayer of the vesicle membrane more than the longer acyl chain probes (Loew, 1996). Following photobleaching, then, only half of the initial di-4-ANEPPS vesicle fluorescence may be recovered through the outer, hemifused monolayer since probe diffusion into the continuous monolayer occurs faster than probe flipping. Hence, we observe only 53% average di-4-ANEPPS redistribution into attached granules.

The redistribution times (τ) per probe are dramatically longer than expected based on the diffusion coefficients of the respective probes in either membrane. τ was independent of the probe concentration used to label the samples (data not shown), suggesting that the number of membrane-associated probe molecules does not significantly affect characteristics of the lipid bilayer. With the exception of di-4-ANEPPS, we see no difference between τ and aliphatic chain length for probes with 8- to 18-acyl carbons (pT-test>0.06 for all pairs). Thus, characteristics of the lipid probe alone are unlikely contributing to the slow redistribution times. Rather, differences in the extent of τ into the vesicle (e.g. diI versus diO) may include a probe’s effect on membrane curvature that could alter the size and shape of the hemifusion neck (Razinkov et al., 1998) and/ or different physical or chemical interactions with protein components at the neck region that restrict probe mobility, as observed during hemagglutinin-mediated hemifusion (Leikina and Chernomordik, 2000). Although beyond the scope of the present work, further investigation of these differences may reveal important information about the structure of this stable hemifusion intermediate.

Discussion

Sea urchin egg cortical granules have served as a paradigm for secretory vesicle biology for decades, and here we continue the tradition by showing that they are stably docked in a hemifused state. Several lines of evidence support our conclusion that these vesicles are in a hemifused – versus fully fused – state, including ultrastructural morphology of the interface (FIG 1A’) (Chandler, 1991; Vacquier, 1975) and membrane capacitance traces before versus after fertilization (McCulloh and Chambers, 1992). The stability of this hemifusion is consistent with the 6.3 μsec half-life of a hemifused intermediate calculated in silico (Kasson et al., 2006), as well as the membrane status of liposomes observed in the presence of limiting concentrations of the SNARE components (Xu et al., 2005) or with various permutations of trans-complexes (Lu et al., 2006). We therefore predict that, in general, secretory vesicles dock with their target membrane via stable, hemifused intermediates. Indeed, a special pool of synaptic vesicles appears stably hemifused to their target membrane, as shown by tomographic electon microscopy in fixed neurons (Zampighi et al., 2006).

We also found that SNARE-associated vesicle proteins involved in regulating exocytosis are immobile in the plane of the vesicle membrane. This immobility may be due to anchorage by lumenal domains of the transmembrane proteins VAMP/synaptobrevin and/or synaptotagmin that interact with immobile vesicle contents (Runnstrom, 1966) or due to their self-organization into a scaffold-like shell that itself is immobilized at the point of contact with the plasma membrane (Jahn and Scheller, 2006). SNARE complex immobility also suggests that continuous recruitment of SNARE-associated vesicle proteins does not contribute to stable vesicle association with the plasma membrane; rather, the initial SNARE complexes assembled at the microdomain of membrane contact are sufficient to maintain cortical granule attachment (Jahn and Scheller, 2006). Does the static nature of these surface proteins imply a specialized biological function? A uniform distribution of proteins required for exocytosis on the granules could, for example, enhance the efficiency of a vesicle anchoring with the plasma membrane since any surface can participate in assembling a SNARE complex. This was observed first hand in our vesicle re-attachment experiments, where cortical granules mechanically separated from the plasma membrane were able to stably re-associate with the plasma membrane–but curiously could not establish a hemifused membrane state. Evidently, cytoplasmic factors are required to achieve this state, and the hemifusion assay utilized here can be exploited to identify such regulators. The immobility of SNARE-associated vesicle proteins is also consistent with multipore exocytosis events observed in a single granule during cortical reorganization at fertilization (Chandler, 1991; Chandler and Heuser, 1979; Vacquier, 1975), a process similar to compound exocytosis used by pancreatic acinar and mast cells to rapidly release vesicle contents en masse in response to a single stimulus (Pickett and Edwardson, 2006).

Egg cortical granules are analogous to neurotransmitter vesicles at the active zones of presynaptic boutons. For example, these vesicle populations both undergo rapid fusion in response to calcium (Sudhof, 2004; Vacquier, 1975) and share hemifused membrane geometry (Zampighi et al., 2006). An extension of this analogy would suggest that the latter hemifused intermediate is regulated by complexins (synaphins), which are necessary for the rapid, synchronous exocytosis of neurotransmitter vesicles (Tang et al., 2006) and are expressed in the sea urchin oocyte (J. L. Wong, unpublished). The role of complexin in super-priming of SNARE complexes at the junction between vesicle and target membranes could also indirectly constrain SNARE-associated proteins within the vesicle membrane, perhaps by establishing a network that includes VAMP/synaptobrevin and its regulators synaptotagmin and Rab3. Only the action of calcium on the SNARE complex relieves this hemifused membrane intermediate, driving rapid granule exocytosis to completion (Crabb and Jackson, 1985; Hu et al., 2002; Sudhof, 2004; Tang et al., 2006; Vacquier, 1975).

Experimental Procedures

Animals

Adult Strongylocentrotus purpuratuseggs were obtained from Charles Hollahan (Santa Barbara, CA, USA) and kept in 15°C artificial seawater generated from Instant Ocean premixed salts (Aquarium Systems, Mentor, OH, USA). Eggs were collected by intraceolomic injection of 0.5 M KCl, washed once with pH 5.2 ASW-HCl, and equilibrated to calcium-free seawater.

Reagents

Affinity-purified antibody Fabs against sea urchin VAMP/synaptobrevin (Conner et al., 1997), Rab3 (Conner et al., 1997), and synaptotagmin (Leguia et al., 2006) were labeled with Oregon Green or Alexa Fluor 488® using respective conjugation kits (Invitrogen). Total granule-associated protein was labeled using the free-amine reactive fluorophore in anAlexaFluor 488® Protein Labeling kit (Invitrogen). Fluorescent lipid probes used include di-4-ANEPPS, di-8-ANEPPS, di-12-ANEPPS, Vybrant C-18 probes diI and diO (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Stocks of ANEPS probes were dissolved in ethanol.

Staining and Fluorescence Recovery Assays

Cortical granule lawns were created from eggs on glass coverslips as previously published (Crabb and Jackson, 1985; Vacquier, 1975; Wong and Wessel, 2007). Re-attached cortical granules were identified by a slight protrusion extending from the granule surface, morphology similar to that reported for hemifused vesicles (Zampighi et al., 2006), which we believe represents the hemifusion stalk surrounded by SNARE-associated proteins. All lipid probes and Fabs were diluted into isotonic, calcium-free buffer (CFB; 0.5 M NaCl, 0.01 M KCl, 1.5 mM NaHCO3, 60 mM NaOH, 20 mM EGTA [pH 8.0]) prior to labeling samples. Samples were labeled for 2 hours (Fabs) or 10 minutes (Alexa Fluor 488, lipid probes) on ice, washed extensively with cold CFB, and then mounted on glass slides (Wong and Wessel, 2007).

Fluorescence redistribution assays were conducted as described elsewhere (Cowan et al., 2004; Wong and Wessel, 2007). Samples were imaged on a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope using a 63X, 1.4 NA PlanApochromat objective using a 488 nm argon (Fabs, ANEPS probes, and diO) or 543 nm helium/neon laser (diI). The pinhole was fully opened to ensure that maximal emission signal was collected from the entire vesicle. Five pre-bleach frames were taken, followed by 55 post-bleach frames. Total time for each experiment ranged from 1.7 seconds to 5 minutes, depending on the delay between each acquisition (0, 1 or 5 seconds). The quality of each preparation was tested by demonstrating no fluorescence recovery over a 5-minute period following complete bleaching of individual cortical granules stuck only to the glass (unattached) – recovery would be an artifact of excess fluorophore in the buffer (data not shown).

Redistribution into attached granules after full bleaching was calculated by measuring the average fluorescence intensity on the granule before bleaching (AVG0), and the average fluorescence intensity on the granule as a function of time after bleaching (AVG1(t)). These are transformed into a function F(t):

We used a Marquadt-Levenberg iterative curve-fitting algorithm to calculate:

| and fractional recovery (R): |

Analysis and statistics

All errors are standard deviations. Single-factor ANOVA analysis was used to compare data for groups of fluorophores, assuming α = 0.01. Pair-wise comparisons using two-tailed Student’s t-test were conducted as a follow up to ANOVA results. Multiple pairwise comparisons were deemed significant according to Bonferroni-adjusted criteria.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Leslie Loew for his regular consultation. This work was supported by grants from the N.I.H. and N.S.F. Microscopy facilities at the Center for Cell Analysis and Modeling are supported by the N.I.H.

Abbreviations

- FRAP

fluorescence recovery after photobleaching;

- SNARE

soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptors

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Citations

- Basanez G. Membrane fusion: the process and its energy suppliers. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59:1478–1490. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8523-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentz J. Membrane fusion mediated by coiled coils: a hypothesis. Biophys J. 2000;78:886–900. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76646-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler DE. Multiple intracellular signals coordinate structural dynamics in the sea urchin egg cortex at fertilization. J Electron Microsc Tech. 1991;17:266–293. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1060170304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler DE, Heuser J. Membrane fusion during secretion: cortical granule exocytosis in sea urchin eggs as studied by quick-freezing and freeze-fracture. J Cell Biol. 1979;83:91–108. doi: 10.1083/jcb.83.1.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernomordik LV, Kozlov MM. Membrane hemifusion: crossing a chasm in two leaps. Cell. 2005;123:375–382. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchward MA, Rogasevskaia T, Hofgen J, Bau J, Coorssen JR. Cholesterol facilitates the native mechanism of Ca2+-triggered membrane fusion. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4833–4848. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner S, Leaf D, Wessel G. Members of the SNARE hypothesis are associated with cortical granule exocytosis in the sea urchin egg. Mol Reprod Dev. 1997;48:106–118. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199709)48:1<106::AID-MRD13>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan AE, Olivastro EM, Koppel DE, Loshon CA, Setlow B, Setlow P. Lipids in the inner membrane of dormant spores of Bacillus species are largely immobile. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:7733–7738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306859101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crabb JH, Jackson RC. In vitro reconstitution of exocytosis from plasma membrane and isolated secretory vesicles. J Cell Biol. 1985;101:2263–2273. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.6.2263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X, Jackson MB. Structural transitions in the synaptic SNARE complex during Ca2+-triggered exocytosis. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:281–293. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200510012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu K, Carroll J, Fedorovich S, Rickman C, Sukhodub A, Davletov B. Vesicular restriction of synaptobrevin suggests a role for calcium in membrane fusion. Nature. 2002;415:646–650. doi: 10.1038/415646a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahn R, Scheller RH. SNAREs - engines for membrane fusion. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:631–643. doi: 10.1038/nrm2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasson PM, Kelley NW, Singhal N, Vrljic M, Brunger AT, Pande VS. Ensemble molecular dynamics yields submillisecond kinetics and intermediates of membrane fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11916–11921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601597103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlovsky Y, Kozlov MM. Stalk model of membrane fusion: solution of energy crisis. Biophys J. 2002;82:882–895. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75450-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laidlaw M, Wessel GM. Cortical granule biogenesis is active throughout oogenesis in sea urchins. Development. 1994;120:1325–1333. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.5.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leguia M, Conner S, Berg L, Wessel GM. Synaptotagmin I is involved in the regulation of cortical granule exocytosis in the sea urchin. Mol Reprod Dev. 2006;73:895–905. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leikina E, Chernomordik LV. Reversible merger of membranes at the early stage of influenza hemagglutinin-mediated fusion. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:2359–2371. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.7.2359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loew LM. Potentiometric dyes: Imaging electrical activity of cell membranes. Pure & Appl Chem. 1996;68:1405–1409. [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Xu Y, Zhang F, Shin YK. Synaptotagmin I and Ca(2+) promote half fusion more than full fusion in SNARE-mediated bilayer fusion. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:2238–2246. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCulloh DH, Chambers EL. Fusion of membranes during fertilization.Increases of the sea urchin egg’s membrane capacitance and membrane conductance at the site of contact with the sperm. J Gen Physiol. 1992;99:137–175. doi: 10.1085/jgp.99.2.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melia TJ, You D, Tareste DC, Rothman JE. Lipidic antagonists to SNARE- mediated fusion. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29597–29605. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601778200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickett JA, Edwardson JM. Compound exocytosis: mechanisms and functional significance. Traffic. 2006;7:109–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pobbati AV, Stein A, Fasshauer D. N- to C-terminal SNARE complex assembly promotes rapid membrane fusion. Science. 2006;313:673–676. doi: 10.1126/science.1129486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razinkov VI, Melikyan GB, Epand RM, Epand RF, Cohen FS. Effects of spontaneous bilayer curvature on influenza virus-mediated fusion pores. J Gen Physiol. 1998;112:409–422. doi: 10.1085/jgp.112.4.409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runnstrom J. The vitelline membrane and cortical particles in sea urchin eggs and their function in maturation and fertilization. Adv Morphog. 1966;5:221–325. doi: 10.1016/b978-1-4831-9952-8.50010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen JB, Wiederhold K, Muller EM, Milosevic I, Nagy G, de Groot BL, Grubmuller H, Fasshauer D. Sequential N- to C-terminal SNARE complex assembly drives priming and fusion of secretory vesicles. Embo J. 2006;25:955–966. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudhof TC. The synaptic vesicle cycle. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:509–547. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.26.041002.131412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahara M, Coorssen JR, Timmers K, Blank PS, Whalley T, Scheller R, Zimmerberg J. Calcium can disrupt the SNARE protein complex on sea urchin egg secretory vesicles without irreversibly blocking fusion. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33667–33673. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J, Maximov A, Shin OH, Dai H, Rizo J, Sudhof TC. A complexin/ synaptotagmin 1 switch controls fast synaptic vesicle exocytosis. Cell. 2006;126:1175–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacquier VD. The isolation of intact cortical granules from sea urchin eggs: calcium lons trigger granule discharge. Dev Biol. 1975;43:62–74. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(75)90131-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker CW, Harrington LM, Lesser MP, Fagerberg WR. Nutritive phagocyte incubation chambers provide a structural and nutritive microenvironment for germ cells of Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis, the green sea urchin. Biol Bull. 2005;209:31–48. doi: 10.2307/3593140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessel GM, Conner SD, Berg L. Cortical granule translocation is microfilament mediated and linked to meiotic maturation in the sea urchin oocyte. Development. 2002;129:4315–4325. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.18.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong JL, Wessel GM. FRAP analysis of secretory granule lipids and proteins in the sea urchin egg. In: Ivanov A, editor. Exocytosis and Endocytosis. Totawa NJ: Humana Press Incorporated; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong JL, Wessel GM. Defending the zygote: Search for the ancestral animal block to polyspermy. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2006a;72:1–151. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(05)72001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong JL, Wessel GM. Rendezvin: An essential gene encoding independent, differentially-secreted egg proteins that organize the fertilization envelope proteome following self-association. Mol Biol Cell. 2006b;17:5241–5252. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-07-0634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Zhang F, Su Z, McNew JA, Shin YK. Hemifusion in SNARE-mediated membrane fusion. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:417–422. doi: 10.1038/nsmb921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaitseva E, Mittal A, Griffin DE, Chernomordik LV. Class II fusion protein of alphaviruses drives membrane fusion through the same pathway as class I proteins. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:167–177. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zampighi GA, Zampighi LM, Fain N, Lanzavecchia S, Simon SA, Wright EM. Conical electron tomography of a chemical synapse: vesicles docked to the active zone are hemi-fused. Biophys J. 2006;91:2910–2918. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.084814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]