Abstract

AP endonuclease (AP endo), a key enzyme in repair of abasic sites in DNA, makes a single nick 5′ to the phosphodeoxyribose of an abasic site (AP-site). We recently proposed a novel mechanism, whereby the enzyme uses a key tyrosine (Tyr171) to directly attack the scissile phosphate of the AP-site. We showed that loss of the tyrosyl hydroxyl from Tyr171 resulted in dramatic diminution in enzymatic efficiency. Here we extend the previous work to compare binding/recognition of AP endo to oligomeric DNA with and without an AP-site by wild type enzyme and several tyrosine mutants including Tyr128, Tyr171 and Tyr269. We used single turnover and electrophoretic mobility shift assays. As expected, binding to DNA with an AP-site is more efficient than binding to DNA without one. Unlike catalytic cleavage by AP endo, which requires both hydroxyl and aromatic moieties of Tyr171, the ability to bind DNA efficiently without an AP-site is independent of an aromatic moiety at position 171. However, the ability to discriminate efficiently between DNA with and without an AP-site requires tyrosine at position 171. Thus, AP endo requires a tyrosine at the active site for the properties that enable it to behave as an efficient, processive endonuclease.

Keywords: AP endonuclease, APE1, Apex, base excision repair, kinetics, EMSA, tyrosine, DNA binding

Introduction

Abasic (AP) sites are major lesions in DNA generated either spontaneously or through the action of endogenous or exogenous factors (8, 13, 23, 24). Up to 200,000 abasic sites are created in a cell each day (13, 23, 36). Unrepaired abasic sites can lead to further DNA damage in the form of ds breaks when there are two or more sites within close proximity to each other on opposite strands (6, 32), as well as inhibition of topoisomerases (48), replication and transcription (52). To correct these lesions, living systems have evolved abasic site repair (ASR) (44). One of the key enzymes in ASR is apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease (AP endo, Apex, HAP1, Ref-1, Ape) (9, 10, 17, 25, 40, 42, 43), which nicks the DNA backbone immediately 5′ to the phosphodeoxyribose (dRP) of the AP-site. The resulting dRP is then removed by a lyase activity, usually that of DNA polymerase-β, generating a single nucleotide gap that is filled by a DNA polymerase. Once the correct nucleotide is inserted, the nick is sealed by a ligase (10, 13, 25, 44).

AP endo was first identified as having a role in DNA repair when Escherichia coli mutants deficient in exonuclease III, the prokaryotic equivalent to AP endo, were shown to have an increased sensitivity to alkylating agents but no marked sensitivity to UV or γ-irradiation (51). Mammalian AP endo, initially isolated from human tissue (19, 26, 34) and cell lines (4, 21, 22), was confirmed as the E. coli equivalent because of its enzymatic activity and because the gene complemented E. coli deficient in exonuclease III for resistance to alkylating agents (9, 40, 42). AP endo binds abasic (AP) site-containing DNA in the absence of divalent cation with remarkable affinity as shown using an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) (11, 28, 29, 43, 47) and single turnover (ST) kinetics (43). As a processive enzyme (5), AP endo also binds DNA lacking an AP-site with surprising affinity (2, 43). Indeed, the fact that the enzyme is processive (5) requires that AP endo bind DNA, whether or not it contains an AP-site, discriminate normal DNA from AP-site-containing DNA, and, once an AP-site is cleaved, move on quickly to locate the next AP-site. In this paper we have used two methodologies to generate a more complete picture of how AP endo recognizes DNA with and without an AP-site. EMSA is routinely employed to measure DNA binding with proteins that interact with a particular consensus sequence (15, 18, 39, 46, 49, 50) or with a particular lesion (11, 14, 29, 47), while single turnover and steady state kinetics examine binding from the viewpoint of catalytic activity.

Materials and Methods

Source of WT and mutant AP endo

Human AP endo was obtained by expression of the gene cloned into plasmid pXC53 and purified as described earlier (43). All mutations were made starting with this plasmid. Preparation of Y128A, Y171A and Y269A is described in Mundle et al. (35). Y171F and Y171H were initially the gift of Dr. David Wilson III, although the Y171F mutation was subsequently created in the pXC53 plasmid. To ensure consistency of the two mutants from the Wilson laboratory with others prepared in the Strauss laboratory, data from WT AP endo from the Wilson laboratory were shown to match that generated with WT from the Strauss laboratory (data not shown).

Preparation of substrate

Substrate lacking an AP-site was the 45-mer containing a U at position 21 shown below and used in previous studies (27, 35). Substrate containing an AP-site originated with the same 45-mer oligonucleotide:

5′-AGC TAC CAT GCC TGC ACG AAU TAA GCA ATT CGT AAT CAT GGT CAT - 3′

3′-TCG ATG GTA CGG ACG TGC TTG ATT CGT TAA GCA TTA GTA CCA GTA - 5′

The 5′ end of the U-containing strand was labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase, (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) as described earlier. The AP-site was generated through digestion for 30 min at 37 °C with E. coli uracil-DNA glycosylase (UNG) (1U/100 pmol of U-containing oligonucleotide; Epicenter Technologies, Madison, WI) in the presence of 0.2 M NaBH4. NaBH4 reduces and stabilizes the AP-site so that no βelimination product forms (43). NaBH4 does not interfere with the glycosylase because UNG has no lyase activity (7, 30, 31). Furthermore, the β-elimination product of an AP-site inhibits enzymatic activity (43). After UNG was inactivated at 70 °C – 75 °C for 5 min, the solution was slow cooled to 22 °C.

EMSA binding assays

Substrate (0.25 nM) was incubated in the presence of enzyme (0–250 nM) at 25 °C for 30 min. Incubation medium contained 0.5% polyvinyl alcohol, 10% glycerol, 100 μg/ml bovine serum albumin, 6–8 mM NaCl, and 0.1 mM EDTA in 50 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5. Bound and free oligonucleotide were resolved at 70 V on 8% native polyacrylamide gels in 1X tris/borate/EDTA buffer (41) at 4 °C and quantified by PhosphorImager analysis. Substrate incubated in the absence of enzyme was used as the control in each case. Bound DNA was calculated as the difference between unbound DNA in the absence and presence of protein. The Kd value was calculated at the concentration at which half maximal binding was observed from the following relationship (12):

| Equation 1 |

When the enzyme concentration was much higher than the substrate concentration and the bound enzyme did not lead to appreciable decrease in free enzyme concentration, the equation reduced to:

| Equation 2 |

Single turnover assays

ST assays to determine substrate binding were performed as described previously (43). In brief, substrate was permitted to bind with enzyme at the concentrations indicated in the presence of 4 mM EDTA to prevent cleavage of substrate during binding. At the indicated times cleavage was initiated by addition of 10 mM MgCl2 in the presence of trap (2 mg/ml heparin and 6.1 μM HDP) (see ref.(43)), which prevents additional rounds of catalysis. Reactions were terminated by addition of 0.5 M EDTA to a final concentration of 87 mM. Substrate and product were resolved by denaturing gel electrophoresis and quantitated by PhosphorImager analysis (43). The presence of slope = 0 after binding reached equilibrium indicated that conditions for ST were met. While ST methodology provides parameters that more accurately describe the kinetics of enzyme action (43), single turnover methodology is no longer appropriate for mutants where k−1 exceeds kcat (12). For such mutants, the concentration of ES at equilibrium is underestimated and results in a corresponding overestimate in Kd value.

The Km for enzymes that follow Briggs-Haldane kinetics is described as Km = (k−1 + kcat)/k+1. When kcat ≪ k−1, the equation reduces to Km = k−1/k+1, that is, the Km and Kd values are similar. In fact, for the Tyr171 mutant series, the kcat values for the Tyr171 mutant series are so slow (10−3–10−4 s−1) (35) that the Kd is essentially the same as the Km, measured under steady state conditions. Experiments with Y269A were carried out with 0.2 nM enzyme and 4 nM substrate (final concentration), 0.4 nM enzyme and 4 nM substrate, and 1 nM enzyme and 4 nM substrate. Binding by Y128A was measured at 4 nM enzyme and 4 nM substrate, while binding by Y171A was measured at 7 nM enzyme and 7 nM substrate; binding by Y171F was examined at 4 nM, 10 nM or 20 nM enzyme and 4 nM substrate; and binding by Y171H was examined at 4 nM, 20 nM or 40 nM enzyme and 4 nM substrate. Previously published binding experiments for WT enzyme were performed at 0.1 nM enzyme and 1 nM substrate, 0.4 nM enzyme and 4 nM substrate and 1 nM enzyme and 10 nM substrate (43). For the current series of experiments, binding for WT enzyme was repeated at 0.4 nM enzyme and 4 nM substrate. WT and Y269A enzymes were allowed 20 s to complete a single round of catalysis after addition of Mg2+/trap. For Y128A, 30 s was used and for the Tyr171 mutants, either 20 s or 7200 s was used with no difference in results. During the binding step, the concentration of salt was 68 mM, while during the catalytic step, the concentration of salt was 40 mM NaCl. This salt concentration was sufficient to ensure cleavage of substrate previously bound to enzyme. For each enzyme 3–5 experiments were performed.

Single turnover Kd values were calculated from the relationship:

| Equation 3 |

where Ei and Si are initial concentrations of enzyme and substrate respectively and ESe is the concentration of ES at equilibrium. Substrate association and dissociation constants were calculated explicitly from the relationship (12):

| Equation 4 |

where kobs = 0.693/t1/2 was determined experimentally.

Results

Kd values determined by ST/SS

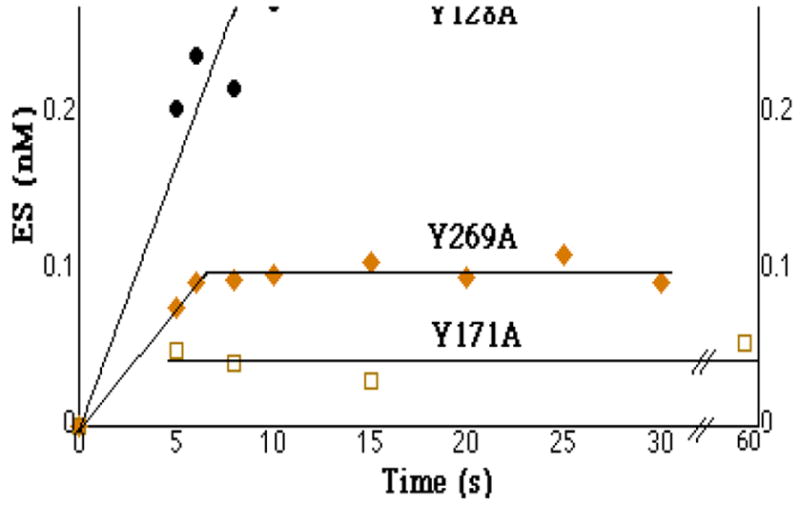

In order to compare binding of AP endo to DNA in a quantitative fashion, we employed single turnover (ST), steady state (SS) and EMSA methodologies. ST methodology allowed substrate containing a single AP-site to bind reversibly to enzyme under conditions where there was no conversion to product (12, 43). Divalent cation was then added to convert all ES to product, while the presence of a trap prevented the enzyme from initiating a second round of catalysis. Therefore, the amount of cleavage product directly reflected the amount of ES at equilibrium. We originally established ST conditions in order to describe the behavior of WT AP endo in recognizing and cleaving an AP-site (43) and showed that the Kd for WT enzyme was 0.8 nM. Using a 45-mer oligonucleotide with an AP-site at position 21, we compared the time course of binding by WT and five tyrosine mutants (Figures 1 and 2 and Table 1).

Figure 1.

Single turnover binding of AP-site containing DNA by AP endonuclease mutants Y128A (●), Y269A (◆) and Y171A (□). For the experiment shown in the figure, substrate and enzyme were each present at 4 nM for Y128A, at 4 nM and 0.4 nM respectively for Y269A and at 7 nM for Y171A. [ES]eq for Y128A was 0.28 nM, when initial concentration of enzyme and substrate were each 4 nM. ([ES]eq for Y269A was 0.1 nM when initial enzyme and substrate were 0.4 nM and 4 nM respectively).

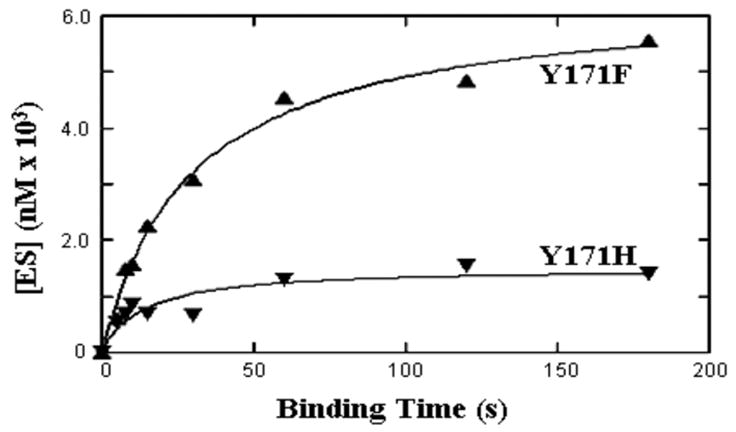

Figure 2.

Single turnover binding of AP-site-containing DNA by AP endo mutants Y171F (▲) and Y171H (▼). For the experiment shown in the figure, substrate and enzyme were each present at 7 nM (Y171F) or 4 nM and 20 nM respectively (Y171H).

Table 1.

Binding constants obtained by steady state and single turnover methodologies. Single turnover data are from experiments presented here; Km and enzymatic efficiency data are from Mundle et al.(35). Km for an enzyme such as AP endo that follows Briggs-Haldane kinetics (2) is described by the equation Km = (kcat + k−1)/k+1. When kcat < k−1, Kd is best approximated by the Km obtained by steady state measurements. In these cases [ES]eq measured by single turnover is an underestimate, which results in an overestimate of Kd. Hence, the Km determined by steady state kinetics is the better estimator of Kd. (See text.)

We considered that two tyrosines, Tyr128 and Tyr269, located outside the active site, were likely to be involved in DNA binding. These residues interact with AP-site containing oligonucleotide just upstream and downstream of the AP-site in the co-crystal structure (33). Mutation of either of these residues to alanine results in loss of one-two orders of magnitude in enzymatic efficiency (35). The Kd value for Y128A(Table 1) was 52+/−22 nM (SE,3). Thus, converting Tyr128 to alanine resulted in a 65-fold increase in Kd in comparison to that of WT. Conversion of Tyr269 to alanine resulted in an increased Kd to 7+/−0.5 nM (SE,3), an increase of 9-fold over that of the WT enzyme. Equation 4 and the time courses presented in Figure 1 allowed us to determine explicit substrate association and dissociation constants (12) for Y128A and Y269A. Values for Y128A were 5 × 106 M−1s−1 and 0.2 s−1 respectively. Similarly, the values for Y269A were 2 × 107 M−1s−1 and 0.2 s−1 respectively. Thus, the rate of substrate association was decreased 10–20-fold from that of wild type, while the rate of substrate dissociation was increased about 5-fold for both mutants. These values indicated that the Briggs-Haldane relationship, where Km= (k−1 + kcat)/k+1, was conserved for Y128A and Y269A. Also, these data confirmed that the two residues were involved in binding and recognition of substrate.

Tyr171 is located in the active site of AP endo (33). Conversion of Tyr171 to phenylalanine or alanine results in major loss (four-five orders of magnitude) in enzymatic efficiency (35) See Table 1. Mutants at Tyr171 bound substrate very poorly, when examined by ST methods: [ES]eq values were extremely low. When Equation 3 was used to calculate Kd values from [ES]eq, the values far exceeded those of the other mutants [2,900 +/−676 (SE,4) for Y171A; 5,900 +/−1927 (SE,4) for Y171F and 61,585 +/− 19,230 (SE,3) for Y171H]. However, these values were not valid indicators of Kd, because the kcat ≪ k−1. Because ES would dissociate before it could be detected by this method, attempts to measure binding based on ST methods could not provide accurate values for these mutants. Nevertheless, we were able to obtain a valid Kd measurement, because the Briggs-Haldane relationship reduced to Km = k−1/k+1 (Table 1, column 6) under these conditions. From these comparisons, loss of the hydroxyl group alone (Y171F) or the entire phenolate (Y171A) increased Kd by 318–450 fold. Adding a positive charge (Y171H) drastically interfered with binding and recognition and increased Kd by 2500-fold.

Although it was inappropriate to use the observed [ES]eq obtained by SS measurements for calculating kinetic constants, the shape of the single turnover binding curves allowed us to obtain valid t1/2 and kobs values, using Equation 4 for Y171F. Since k−1 = Km k+1, one could then calculate theoretical values for k+1 and k−1. These values were 105 M−1s−1 and 0.03 for k+1 and k−1 respectively for Y171F. The k+1 value was three orders of magnitude below that of the WT enzyme, corroborating the supposition that kcat ≪ k−1, while the k−1 value did not change. Thus, the rate of substrate binding was ~3 orders of magnitude lower than that by WT; once bound, substrate dissociated at ~same or somewhat faster rate. This result indicated that the Y171F recognized the AP-site poorly. Similar calculations for Y171H failed, because we were unable to obtain an explicit Km (the enzyme failed to saturate at or below 1.3 μM (35)). Since the inflection point on the binding curve for Y171A occurred too quickly to be detected under the conditions used here (Figure 2), we could not obtain an explicit value for t1/2 so that similar calculations for Y171A also failed.

Kd determined by EMSA

In order to compare binding of the various tyrosine mutants to DNA lacking an AP-site, we turned to a method that did not require enzymatic activity. We examined the ability of the WT enzyme and the tyrosine mutants to discriminate between substrate with or without a single AP-site at position 21 by EMSA. In order to perform the studies in a quantitative fashion so that Kd values could be compared with data derived from ST or steady state studies as appropriate, the concentration of AP endo was varied between 0 and 300 nM, while the concentration of substrate was held constant at 0.25 nM. Kd values were then calculated using either Equation 1 or Equation 2.

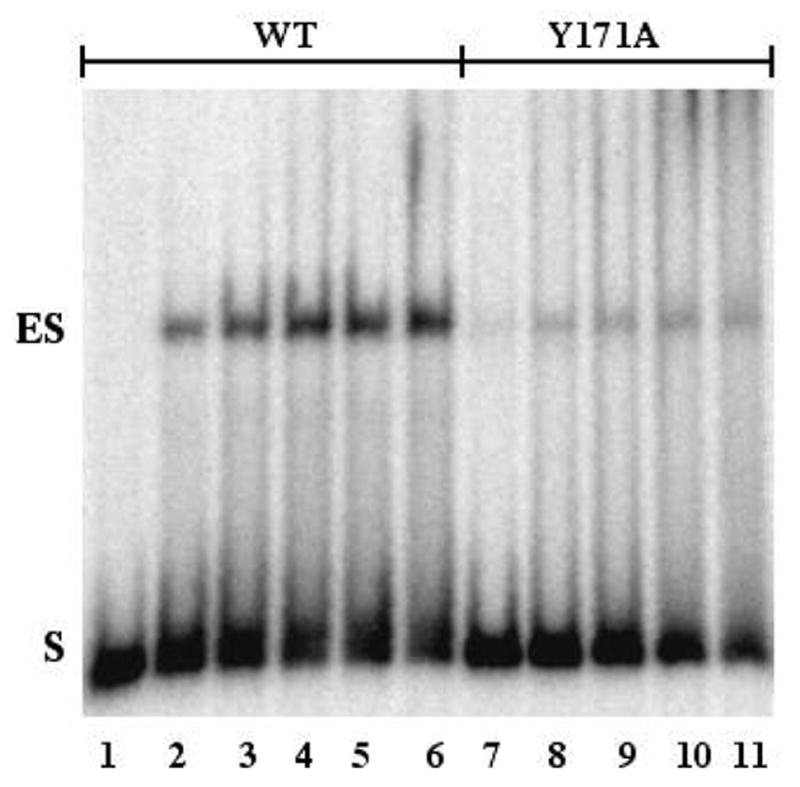

Figure 3 represents an example of an EMSA performed with WT and Y171A proteins. In all cases, enzyme bound to DNA (ES), determined by the degree of band retardation, was dependent on the concentration of protein. In this case, the concentration of protein at which maximum band retardation was reached was ~25 nM for WT and ~250 nM for Y171A. Under these conditions <6% of initial substrate was converted to product when WT enzyme was incubated with substrate under EMSA conditions, ensuring that most gel-shifted oligonucleotide was not converted to product (data not shown). This result was expected, because 4 mM EDTA present in the incubation mix prevents AP-site cleavage by enzyme (43).

Figure 3.

EMSA analysis of binding AP-site containing DNA by wild type and Y171A AP endonuclease, non-denaturing gel. WT or Y171A were incubated with 0.25 nM substrate for 30 min at 25 °C and resolved by non-denaturing gel electrophoresis as described in Methods. Lane 1, no added protein; lane 2, 0.5 nM WT; lane 3, 2.5 nM WT; lane 4, 5.0 nM WT; lane 5, 10 nM WT; lane 6, 25 nM WT; lane 7, 5 nM Y171A; lane 8, 25 nM Y171A; lane 9, 50 nM Y171A; lane 10, 100 nM Y171A; lane 11, 250 nM Y171A.

Even though the molecular weights of WT and individual mutant proteins were essentially the same, the mobility of ES depended on the mutation. For instance, the mobility of the major species of ES of Y171F and Y171A was the same as that of WT. However, the mobility of the major ES complex of DNA with Y128A was greater than that of WT, while the mobility of the major ES complex of DNA with Y171H and Y269A was less than that of WT (data not shown). Although the changes in mobility might tempt one to presume that the ES complex of DNA with one mutant or the other was more or less stable than that of DNA with WT, the quantitative data presented below and above do not support this possibility.

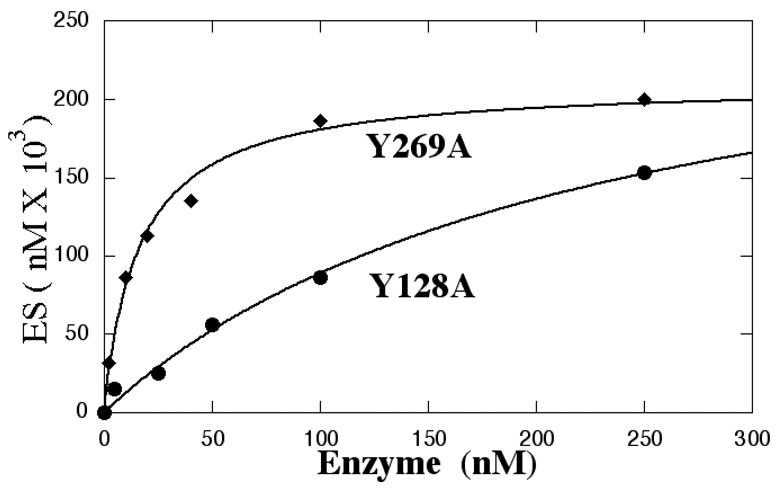

Figure 4 and Table 2 compare the concentration dependence of binding behavior of mutants with that of WT enzyme, using an oligonucleotide with or without an AP-site. As in the case of ST measurements, each mutant provided a unique binding pattern. Table 2 presents the experimental results comparing Kd values determined by EMSA for substrate with and without an AP-site. Binding of a substrate with an AP-site followed the expected hyperbolic pattern with saturation occurring at different concentration of protein for the different mutants. None of the mutants increased the Kd obtained by EMSA analysis more than 18-fold in comparison with that of WT (Table 2) or reflected previously shown changes in enzymatic efficiency (See Table 1). EMSA-derived values also could not be used to obtain substrate association/dissociation constants in the standard equations used for kinetic analysis. Nevertheless, EMSA analysis of binding of substrate with an AP-site provided Kd values for WT, Y269A and Y128A that generally agreed with or were somewhat higher than those from single turnover studies (43). On the other hand, EMSA greatly underestimated the Kd values for all the Tyr171 mutants as shown by comparison with Kd values obtained from SS and ST experiments.

Figure 4.

Comparison of binding AP-site containing DNA with (●, ◆) and without (○) an AP-site by EMSA analysis. WT and mutant proteins at the indicated concentrations were incubated with 0.25 nM substrate and resolved by non-denaturing gel electrophoresis as described in Methods. The distribution of bound and unbound substrate was quantitated by phosphorImager analysis.

A: Binding AP-site-containing DNA by Y128A(●) and Y269A (◆)

B: Binding by WT AP endo or Tyr171 mutants to oligonucleotide with (●) or without(○) an abasic site.

Table 2.

Ability of WT and tyrosine mutants to discriminate DNA with and without an abasic site. Kd values ± SD for the tyrosine mutants were calculated from binding by EMSA analysis as described in the text and shown in Figure 4. The ratio of the Kd value for DNA containing an AP-site to that for DNA without an AP-site is the discrimination index. ND, not done

| Mutant | Kd(1) (EMSA) (nM) | Kd(2) (EMSA) (nM) | Discrimination Index(3) (EMSA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| With abasic site | Without abasic site | ||

| Wild Type | 4 ±0.7 | 67 ±9 | 17 |

| Y269A | 23 ±11 | ND | _ |

| Y128A | 63 ±15 | ND | _ |

| Y171F | 8 ±1 | 43 ±2 | 5 |

| Y171H | 34 ±13 | 64 ±7 | 2 |

| Y171A | 70 ±18 | 65 ±9 | 1 |

These values are the average of 4–8 independent experiments for each mutant or WT enzyme. The values in parenthesis are standard errors of the mean.

These values are the average of 6–9 independent experiments. The values in parenthesis are standard errors of the mean. ND, not done

Ratio of Kd for DNA lacking an AP-site to Kd for DNA with an abasic site

We then compared the ability of WT and Tyr171 mutant enzymes to bind the same ds oligomer in which the AP-site was replaced with a uridine residue (Figure 4B). Since there was no AP-site, it was not possible to obtain Km or kcat values or to perform a ST assay. The Kd values determined by EMSA analysis are presented in Table 2. As expected from previous studies (43), the ability of WT and most mutant enzymes to bind DNA lacking an AP-site was reduced in comparison to DNA binding with an AP-site. Consequently, Kd values were higher for substrate lacking an AP-site. However, the relative ordering of the Kd values was informative: the Kd value for Y171F was lower than that of WT enzyme, which implied that Y171F bound more tightly to DNA lacking an AP-site than did WT enzyme. Indeed, aside from Y171F, all the Tyr171 mutants bound DNA lacking an AP-site equally well. Thus, an aromatic residue at position 171 was not required for AP endo to bind non AP-site containing DNA. The hydroxyl of Tyr171, required for normal cleavage and recognition of an AP-site, actually interfered with binding to DNA without an AP-site. Thus, Tyr171 can be viewed as enabling the enzyme to scan DNA more efficiently.

Finally the ability to discriminate between DNA with and without an AP-site was compared by examining the ratios of the Kd values obtained by EMSA analysis for DNA with and without an AP-site (Table 2, column 4). Here it became clear that WT AP endo is optimally suited to discriminate between the two forms and that all the Tyr171 mutants fail in this requirement.

Discussion

We have examined binding of AP endo to ds DNA with and without an AP-site by two different methods. One involves values generated using kinetic analysis, while the other employs electrophoretic mobility shift assays. Although each method has disadvantages, the two together provide a comprehensive picture of the role of three key tyrosines in recognizing and binding DNA. Tyr128 and Tyr269 contribute to endonuclease activity primarily through recognition and binding of DNA. Both are present outside the active site but make contact with substrate DNA (33). On the other hand, Tyr171 contributes to enzymatic function through direct involvement in catalysis as well as binding and recognition of DNA. Furthermore, Tyr171 is intimately involved in enabling AP endo to discriminate DNA with an AP-site from DNA without one. The WT enzyme is 17-fold more effective in binding AP-site containing DNA than normal DNA, while the tyrosine mutants discriminate normal and AP-site containing DNA poorly.

Kinetic measurements (ST and SS) require production of product, in this case, a cleaved AP-site. Results obtained by kinetic analysis from ST and SS measurements are useful in establishing a kinetic scheme (27, 35, 43). As valuable as ST is in dissecting steps in the kinetic scheme, however, this methodology fails when the substrate dissociation constant exceeds the kcat. Here the ES complex dissociates so quickly than it cannot be detected accurately. In that case we can still use the Km value derived through steady state measurements to approximate the Kd, because the explicit description for Km [Km = (k−1 + k2)/k+1] reduces to k−1/k+1, which is the same as Kd. The current data are consistent with previously reported changes in enzymatic activity of the various mutants that enabled us to propose a novel mechanism of action for the enzyme (35).

Unlike the ST and SS data, the changes in Kd for substrate containing an AP-site obtained by EMSA do not correlate with changes in enzymatic efficiency. Although increases in Kd measured by EMSA are roughly consistent with decreases in enzymatic efficiency for Y128A and Y269A, (Table 2), the changes observed in the Tyr171 series are not at all consistent. In the Tyr171 series, increases in Kd measured by EMSA range from 1.2-fold in the case of Y171F to 9.3-fold in the cases of Y171A and Y171H. These increases fail to reflect the changes in Km or the profound changes in enzymatic efficiency (> four orders of magnitude decrease). Also, the order of change in Kd values as determined by EMSA implies that the loss of the tyrosyl hydroxyl is hardly significant in interacting with AP-site containing DNA, a conclusion that is not supported by the kinetic data. It is easy to see how one might conclude that tyrosines are not essential for catalysis by AP endo based on EMSA studies, where the Kd value for Y128A binding is increased even more than that for Y171A (38). The discrepancy between EMSA and kinetic analyses could be due to differences in assay conditions: the physical conditions employed during EMSA analysis, such as shear force and the presence of a voltage differential, do not come into play when catalysis is measured.

Kinetic methods, which require enzymatic cleavage to detect the ES intermediate, also cannot provide information on how well the WT or various mutants bind DNA lacking an AP-site, because there can be no cleavage product without an AP-site. AP endo is processive (5) as is uracil DNA glycosylase (3) and a number of restriction endonucleases (37, 45). Being processive, the enzyme binds ds DNA randomly and then searches for an AP-site. After cleavage, the enzyme can dissociate or remain associated until it locates another lesion. However, experiments using EMSA allow us to examine binding to DNA lacking an AP-site. In all cases the enzyme binds DNA with an AP-site better than normal DNA. WT and most of the tyrosine mutant enzymes bind undamaged DNA with equal affinity. The exception is Y171F which binds undamaged DNA more strongly than does the WT. Because the enzyme is processive, we expected that Scatchard plot analysis of EMSA data should resolve into two components, one a high affinity binding site related to the presence of an AP-site and the other a lower affinity site related to non-specific binding to ds DNA (16, 20). Unfortunately, when we examined the data by Scatchard analysis, we observed a decreasing convex function, indicating that at high enzyme concentrations there are multiple equilibria that are not independent of each other (16). This observation is consistent with previous reports by Barzilay et al. (1).

The fact that the presence of the hydroxyl group on Tyr171 interferes with binding of AP endo to DNA lacking an AP-site is yet another indicator of fine tuning in distinguishing AP-site-containing DNA from undamaged DNA. In the co-crystal of AP endo with an 11-bp or a 15-bp AP-site containing oligomer (33) Tyr171 does not interact directly with the AP-site. However, the rotation of the phenolate would enable a direct attack on the scissile phosphate without employing a water molecule as intermediate (35). The very same tyrosyl hydroxyl diminishes binding to DNA lacking an AP-site, perhaps because non AP-site DNA is less deformable than AP-site containing DNA. Thus, the tyrosyl group promotes discrimination between normal and AP-site containing DNA.

Not all proteins that interact with DNA can be studied by ST analysis. For proteins with enzymatic activity, there are two requirements: (1) the binding step must be completely dissociated from the enzymatic step and (2) once catalysis is initiated the enzyme must undergo one and only one round of catalysis. On the other hand, for proteins that bind DNA without chemically altering it or that turn over very slowly, such as transcription factors without enzymatic activity per se or glycosylases with a very low turnover number, one must use some sort of physical strategy, of which EMSA is perhaps the simplest. Indeed, EMSA has proved a valuable tool for identifying consensus sequences for a variety of transcription factors (15, 18, 39, 46). Thus, the two methods together provide a more complete picture of how an active site tyrosine enables AP endo to bind and differentiate normal and AP-site containing DNA.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. William Beard for useful discussions during the early phases of this work and to Dr. David Wilson III for initially providing the Y171H and Y171F mutants.

Abbreviations

- AP endo

Apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease

- AP-site

Abasic site

- ASR

Abasic site repair

- dRP

Phosphodeoxyribose

- ds

Double stranded

- EDTA

Ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid

- EMSA

Electromobility shift assay

- ES

Enzyme.substrate complex

- HDP

Heat degradation product

- HEPES

N-[2-Hydroxyethyl]piperazine-N′-[2-ethanesulfonic acid]

- SS

Steady state

- ST

Single turnover

- UNG

Uracil DNA glycosylase (E.coli)

- WT

Wild type

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Barzilay G, Walker LJ, Robson CN, Hickson ID. Site-directed mutagenesis of the human DNA repair enzyme HAP1: identification of residues important for AP endonuclease and RNase H activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:1544. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.9.1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beloglazova NG, Kirpota OO, Starostin KV, Ishchenko AA, Yamkovoy VI, et al. Thermodynamic, kinetic and structural basis for recognition and repair of abasic sites in DNA by apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease from human placenta. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:5134. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett SE, Sanderson RJ, Mosbaugh DW. Processivity of Escherichia coli and rat liver mitochondrial uracil-DNA glycosylase is affected by NaCl concentration. Biochemistry. 1995;34:6109. doi: 10.1021/bi00018a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brent TP. Purification and characterization of human endonucleases specific for damaged DNA. Analysis of lesions induced by ultraviolet or x-radiation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976;454:172. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(76)90363-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carey DC, Strauss PR. Human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease is processive. Biochemistry. 1999;38:16553. doi: 10.1021/bi9907429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaudhry MA, Weinfeld M. Reactivity of human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease and Escherichia coli exonuclease III with bistranded abasic sites in DNA. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.15650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.David SS, Williams SD. Chemistry of Glycosylases and Endonucleases Involved in Base-Excision Repair. Chem Rev. 1998;98:1221. doi: 10.1021/cr980321h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demple B, Harrison L. Repair of oxidative damage to DNA: enzymology and biology. Annu Rev Biochem. 1994;63:915. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.004411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Demple B, Herman T, Chen DS. Cloning and expression of APE, the cDNA encoding the major human apurinic endonuclease: definition of a family of DNA repair enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:11450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doetsch PW, Cunningham RP. The enzymology of apurinic/apyrimidinic endonucleases. Mutat Res. 1990;236:173. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(90)90004-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erzberger JP, Barsky D, Scharer OD, Colvin ME, Wilson DM., 3rd Elements in abasic site recognition by the major human and Escherichia coli apurinic/apyrimidinic endonucleases. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:2771. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.11.2771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fersht A. Structure and Mechanism in Protein Science. New York: WH Freeman; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedberg EC, Walker GC, Siede W, Wood RD, Schultz RA, Ellenberger T. DNA Repair and Mutagenesis. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2006. p. 1118. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gangurde R, Kaushik N, Singh K, Modak MJ. A carboxylate triad is essential for the polymerase activity of Escherichia coli DNA polymerase I (Klenow fragment). Presence of two functional triads at the catalytic center. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:19685. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002307200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garner MM, Revzin A. A gel electrophoresis method for quantifying the binding of proteins to specific DNA regions: application to components of the Escherichia coli lactose operon regulatory system. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;9:3047. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.13.3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henis YI, Levitzki A. An analysis on the slope of Scatchard plots. Eur J Biochem. 1976;71:529. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1976.tb11141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Izumi T, Henner WD, Mitra S. Negative regulation of the major human AP-endonuclease, a multifunctional protein. Biochemistry. 1996;35:14679. doi: 10.1021/bi961995u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kan HY, Pissios P, Chambaz J, Zannis VI. DNA binding specificity and transactivation properties of SREBP-2 bound to multiple sites on the human apoA-II promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:1104. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.4.1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kane CM, Linn S. Purification and characterization of an apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease from HeLa cells. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:3405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klotz IM, Hunston DL. Protein affinities for small molecules: conceptions and misconceptions. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1979;193:314. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(79)90036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuhnlein U, Lee B, Penhoet EE, Linn S. Xeroderma pigmentosum fibroblasts of the D group lack an apurinic DNA endonuclease species with a low apparent Km. Nucleic Acids Res. 1978;5:951. doi: 10.1093/nar/5.3.951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuhnlein U, Penhoet EE, Linn S. An altered apurinic DNA endonuclease activity in group A and group D xeroderma pigmentosum fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976;73:1169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.4.1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lindahl T. Instability and decay of the primary structure of DNA. Nature. 1993;362:709. doi: 10.1038/362709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindahl T. DNA lesions generated in vivo by reactive oxygen species, their accumulation and repair. In: Dizdaroglu M, editor. DNA Damage and Repair: Oxygen Radical Effects, Cellular Protection and Biological Consequences. New York: Plenum Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindahl T, Barnes DE. Repair of endogenous DNA damage. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2000;65:127. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2000.65.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Linsley WS, Penhoet EE, Linn S. Human endonuclease specific for apurinic/apyrimidinic sites in DNA. Partial purification and characterization of multiple forms from placenta. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:1235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lucas JA, Masuda Y, Bennett RA, Strauss NS, Strauss PR. Single-turnover analysis of mutant human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease. Biochemistry. 1999;38:4958. doi: 10.1021/bi982052v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masuda Y, Bennett RA, Demple B. Dynamics of the interaction of human apurinic endonuclease (Ape1) with its substrate and product. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30352. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masuda Y, Bennett RA, Demple B. Rapid dissociation of human apurinic endonuclease (Ape1) from incised DNA induced by magnesium. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCullough AK, Dodson ML, Lloyd RS. Initiation of base excision repair: glycosylase mechanisms and structures. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:255. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCullough AK, Sanchez A, Dodson ML, Marapaka P, Taylor JS, Lloyd RS. The reaction mechanism of DNA glycosylase/AP lyases at abasic sites. Biochemistry. 2001;40:561. doi: 10.1021/bi002404+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKenzie JA, Strauss PR. Oligonucleotides with bistranded abasic sites interfere with substrate binding and catalysis by human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease. Biochemistry. 2001;40:13254. doi: 10.1021/bi015587o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mol CD, Izumi T, Mitra S, Tainer JA. DNA-bound structures and mutants reveal abasic DNA binding by APE1 and DNA repair coordination [corrected] Nature. 2000;403:451. doi: 10.1038/35000249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mosbaugh DW, Linn S. Further characterization of human fibroblast apurinic/apyrimidinic DNA endonucleases. The definition of two mechanistic classes of enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:11743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mundle ST, Fattal M, Melo LM, Strauss PR. A novel mechanism for human AP endonuclease 1. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:1447. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakamura J, Swenberg JA. Endogenous apurinic/apyrimidinic sites in genomic DNA of mammalian tissues. Cancer Res. 1999;59:2522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nardone G, George J, Chirikjian JG. Differences in the kinetic properties of BamHI endonuclease and methylase with linear DNA substrates. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:12128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nguyen LH, Barsky D, Erzberger JP, Wilson DM., 3rd Mapping the protein-DNA interface and the metal-binding site of the major human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease. J Mol Biol. 2000;298:447. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pollock R, Treisman R. A sensitive method for the determination of protein-DNA binding specificities. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6197. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.21.6197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robson CN, Hickson ID. Isolation of cDNA clones encoding a human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease that corrects DNA repair and mutagenesis defects in E. coli xth (exonuclease III) mutants. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:5519. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.20.5519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sambrook JaR, David W. Molecular Cloning. Cold Spring Harbor. New Yok: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Seki S, Hatsushika M, Watanabe S, Akiyama K, Nagao K, Tsutsui K. cDNA cloning, sequencing, expression and possible domain structure of human APEX nuclease homologous to Escherichia coli exonuclease III. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1131:287. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(92)90027-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strauss PR, Beard WA, Patterson TA, Wilson SH. Substrate binding by human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease indicates a Briggs-Haldane mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1302. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Strauss PR, O’Regan NE. Abasic site repair in higher eukaryotes. DNA Damage and Repair. 2001:43. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Terry BJ, Jack WE, Modrich P. Facilitated diffusion during catalysis by EcoRI endonuclease. Nonspecific interactions in EcoRI catalysis. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:13130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weston K. Extension of the DNA binding consensus of the chicken c-Myb and v-Myb proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:3043. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.12.3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilson DM, 3rd, Takeshita M, Demple B. Abasic site binding by the human apurinic endonuclease, Ape, and determination of the DNA contact sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:933. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilstermann AM, Osheroff N. Stabilization of eukaryotic topoisomerase II-DNA cleavage complexes. Curr Top Med Chem. 2003;3:321. doi: 10.2174/1568026033452519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xanthoudakis S, Curran T. Identification and characterization of Ref-1, a nuclear protein that facilitates AP-1 DNA-binding activity. Embo J. 1992;11:653. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05097.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xanthoudakis S, Miao G, Wang F, Pan YC, Curran T. Redox activation of Fos-Jun DNA binding activity is mediated by a DNA repair enzyme. Embo J. 1992;11:3323. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05411.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yajko DM, Weiss B. Mutations simultaneously affecting endonuclease II and exonuclease III in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1975;72:688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.2.688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yu SL, Lee SK, Johnson RE, Prakash L, Prakash S. The stalling of transcription at abasic sites is highly mutagenic. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:382. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.1.382-388.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]