Abstract

Purpose

Accurate modelling of rectal complications based on DVH data is necessary to allow safe dose escalation in radiotherapy of prostate cancer. We applied different EUD- and dose-volume based NTCP models to rectal wall DVHs and follow-up data of 319 prostate cancer patients in order to identify the dosimetric factors most predictive for grade 2 or higher rectal bleeding.

Materials and Methods

Data of 319 patients, treated at the William Beaumont Hospital with 3D-CRT under an adaptive radiotherapy protocol, were used for this study. The following models were considered: (1) Lyman model and (2) logit-formula with DVH reduced to generalized EUD, (3) serial reconstruction unit (RU) model, (4) Poisson-EUD-model, (5) mean dose- and (6) cutoff dose-logistic regression model. The parameters and their confidence intervals were determined using maximum likelihood estimation.

Results

51 patients (16.0%) showed grade 2 or higher bleeding. As assessed qualitatively and quantitatively, the Lyman- and Logit-EUD, serial RU and Poisson-EUD model fitted the data very well. Rectal wall mean dose did not correlate to grade 2 or higher bleeding. For the cutoff dose model, the volume receiving more than 73.7 Gy showed most significant correlation to bleeding. However, this model fitted the data worse than the EUD-based models.

Conclusions

Our study clearly confirms a volume effect for late rectal bleeding. This can be described very well by the EUD-like models, where the serial RU- and Poisson-EUD model can describe the data with only two parameters. Dose-volume based cutoff-dose models performed worse.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, Rectal toxicity, NTCP, Volume effects, Dose-volume histograms, EUD

1 Introduction

The essential dose-limiting organs in prostate radiotherapy are bladder and rectum. Here, one of the most relevant side effects, which can significantly compromise a patient's quality of life, is chronic rectal bleeding.

Conventional external beam radiotherapy (RT) treatment typically does not allow prostate doses beyond 65–70 Gy without unacceptably high risk of rectal toxicity, while higher tumour doses are favourable for improved tumour control. The possibility of dose escalation beyond 70 Gy to the prostate is based on the volume-effect of rectum, i.e. the observation of increased tolerance to high doses if the high dose region is confined to a small volume. Technically, this becomes feasible thanks to conformal techniques like three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT) or intensity modulated RT (IMRT), especially when aided by image-guided adaptive approaches.

Safe dose escalation necessitates accurate quantitative modelling of the volume effect based on the detailed dose-volume information provided by modern treatment planning systems. Numerous studies have established evidence of a significant correlation between parameters derived from rectal dose-volume histograms (DVHs) and toxicity, see e.g. (1–4) and references therein. However, only a few publications have quantified the risk of rectal complications in terms of normal tissue complication probability (NTCP) models (5–9). Such empiric or semi-empiric models parametrize the vast information about inhomogeneous dose distributions and corresponding outcome data from large patient populations into few-parametric models that assign a single probability value to an individual treatment plan. This enables evidence based ranking of alternative plans in the planning process according to their predicted complication risk. Two important types of NTCP-models can be distinguished: Dose-volume based models which use a single DVH-parameter (e.g. the volume VD irradiated to a certain dose-level D) for ranking plans according to their complication probability. In contrast, EUD-like models define an equivalent uniform dose, , as surrogate parameter calculated using all bins (vi,Di) of a DVH, where the form of the (monotonic) function f depends on the model. Besides possible differences in the quality of fit as investigated in this study, it should be mentioned that the choice between dose-volume based vs. EUD-like models when used for treatment planning, esp. IMRT, affects the process of plan optimization (10–12)

In this study we apply one dose-volume based and five EUD-like NTCP models for chronic rectal bleeding of grade ≥ 2 to a population of 319 prostate cancer patients treated with a 3D-CRT adaptive radiotherapy (ART) technique to doses between 70.2 and 79.2 Gy at the William Beaumont Hospital. This is so far the largest published single-institution patient population used for fitting of rectal NTCP-models. Thus this study not only provides valuable information for identification of the superior modelling approach(es), but also statistically, well based estimates of the corresponding model parameters.

2 Methods and Materials

2.1 Patient data

Data of 319 prostate cancer patients treated between 1999-2002 at the William Beaumont Hospital were used for this study. The characteristics of this patient population have been described in previous studies (3, 13). The patients were part of a Phase II dose-escalation study and underwent 3D conformal radiotherapy with image-guided off-line correction under an adaptive radiotherapy (ART) protocol.

All patients had one pre-treatment planning CT scan, daily portal images to determine and correct for setup errors, additional four CT scans during the first week of the treatment used for individual adaptation of the treatment plan and weekly CT scans in the following to preclude undetected drifts. The (solid) rectum was contoured on the initial CT scan from the anal verge or ischial tuberosities (whichever was higher) to the sacroiliac joints or rectosigmoid junction (whichever was lower). Rectal wall was defined based on the solid rectum contours with 3–4 mm wall thickness.

The ART scheme used has been described elsewhere (14, 15). In short, a four-field box technique with 18 MV photons was used both for the initial treatment plan of the first week and the following adapted plan. In the first week the patients were treated for a dose of 9 Gy to the target, where the PTV was generated based on the CTV of the initial CT (prostate or prostate+sem. vesicles) with a population based margin of 1 cm. For the adapted plan, information from daily portal imaging and the five CT scans available after the first week of treatment were used to estimate setup error and individual prostate mobility, which allowed to define a (generally smaller) patient-specific PTV.

The final dose to the PTV was limited by dose-volume constraints of rectal wall and bladder based on the geometry of the initial planning CT image. For rectal wall these were: (1) D30% = 75.6 Gy and (2) D5% = 82 Gy. The possible dose levels (minimal prostate dose) were chosen under the requirement to meet rectum (and bladder) constraints and were as follows: 70.2, 72, 73.8, 75.6, 77.4 and 79.2 Gy.

For each patient the dose distributions of the initial and adapted plan were calculated using Pinnacle 6.2b (ADAC Laboratories, Milpitas, CA). An in-house developed software was used to calculate DVHs of rectal wall. This software used the contours from the initial (planning) CT and calculated the overall dose as sum of initial and adapted (physical) dose distributions. The DVH-dose bin size was 0.1 Gy, with volume defined as relative (percentage) volume irradiated.

The rectal toxicity variable regarded in this analysis is chronic rectal bleeding. The follow-up scheme defined examinations at 3-month intervals during the first 2 years, and every 6 months from the second to the fifth year. As mentioned above, this study is based on the patient population analysed in Vargas et al. (3, 13). However, for the current study, all patient files were reexamined to improve follow-up time. Complications were graded based on the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v3.0 (see Tab. 1). Twelve of the 331 patient datasets used in Vargas et al. could not be used due to technical problems in restoring dose-distributions or lost, incomplete or inconsistent follow-up information. The median clinical follow-up for the remaining 319 patients was 2.8 years (range: 0.1–6.4), with a inter-quartile range of 1.5–4.0 years (25th–75th percentile).

Table 1.

Toxicity score for chronic rectal bleeding based on CTCAE 3.0.

| Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | mild hemorrhage/bleeding; intervention (other than iron supplements) not indicated |

| 2 | symptomatic and medical intervention or minor cauterization indicated |

| 3 | transfusion, interventional radiology, endoscopic or operative intervention indicated |

| 4 | life-threatening consequences; perforation/dysfunction requiring urgent intervention |

2.2 NTCP models

A NTCP model assigns a complication probability for an organ at risk to a generally inhomogeneous dose-distribution. The functional form of such a model can be based on a mechanistic description of biological processes, or might be designed to result in a phenomenological ‘fit of the data’.

The models regarded in this work are of the following general from:

First, a summary measure μ, such as the mean dose, an equivalent uniform dose (EUD) or similar, is calculated from the dose distribution. The quantity μ serves as a ranking function by imposing an order among individual plans according to their complication risk.

Then, a function, NTCP(μ), which assigns complication probabilities to the values of the summary measure is defined. Such a function is required to (1) continuously map μ to the interval [0, 1], while (2) preserving the ranking imposed by the numerical values of the summary measure. This leads to the class of sigmoid-type (S-shaped) functions, where in the following the probit-, logit-, Poissonian- and logistic formulae are used.

We applied six different models to our data, where the endpoint was chosen to be chronic rectal bleeding of grade ≥ 2. These models differ in the summary measure used and/or the functional form of the NTCP function as described in the following.

2.2.1 Lyman-EUD model

The most widely used phenomenological approach is the family of Lyman models (16–20) which uses the probit function

| (1) |

to map the summary measure μ to the interval [0, 1] of complication probabilities. This integral essentially yields the error function, where the parameter s is the slope of the sigmoid response curve at the steepest point μ=μ50, for which the NTCP function predicts 50% complication probability. Usually the slope parameter s is replaced by its inverse m according to s=1/(m·μ50).

Different DVH reduction schemes have been used for defining the summary measure μ, such as an effective volume (LKB model, (18)) or an effective dose (21). In the following the generalized equivalent uniform dose (22) is used, which defines EUD as Lebesque a-norm of the dose, i.e. in terms of the following power-law relationship:

| (2) |

The sum is calculated over all bins (vi,Di) of the differential DVH, and a is a parameter associated with the strength of the volume effect for the organ under consideration (range a∈[1…∞]): For a→∞ the EUD is the maximum dose (i.e. no volume effect), while for a=1 Eq. (2) gives the mean dose (large volume effect).

Summarizing, the Lyman-EUD model as used in our study is described by three parameters: a, m and EUD50 (usually termed D50).

2.2.2 Logit-EUD model

This model also uses the generalized EUD (Eq. 2) as summary measure μ, while it differs from the Lyman-EUD model in the choice of the NTCP function. Here the logit function

| (3) |

is chosen as sigmoid shape function (6, 10). Its two parameters μ50 (i.e. D50) and k are determined by the EUD, which causes a complication rate of 50%, and the slope of the NTCP curve here. Thus, together with the parameter a of the EUD, this model has three parameters.

2.2.3 Serial reconstruction-unit model

In contrast to the two previous phenomenological NTCP models, the serial reconstruction unit model, which has been proposed recently by Alber and Belka (23), arises from certain general assumptions about the biological processes causing normal tissue complications.

The model regards radiation induced complications as the consequence of local failure of dynamic repair processes. As an assumption, the latter is attributed to the finite range of the repair mechanisms, which finds its correlate in the model by the description of finite-sized reconstruction units and their microscopic dose-response. Borrowing analogies from thermodynamics and statistical physics, the authors derive the following expression to describe the macroscopic dose response in terms of the NTCP for homogeneous irradiation of the partial volume V of an organ with the dose D:

| (4) |

where σ is an organ specific sensitivity parameter and D0 is a reference dose.

For inhomogeneous dose distributions an equivalent uniform dose, which would give the same macroscopic dose-response when applied homogeneously to the whole organ (V=1), can be defined as

| (5) |

Consequently, the NTCP function then reads:

| (6) |

Summarizing, the serial reconstruction unit model has the two parameters σ and D0 to be fitted. Note that in contrast to the previously described models, which have the volume effect parameter a of the power-law EUD as a third parameter, here the sensitivity parameter σ is inherently coupled to the same value in the EUD and NTCP function.

2.2.4 Poisson-EUD model

Similarly to the serial reconstruction unit model, this model utilizes mechanistic concepts to describe predominantly serial tissue dose-response. Assuming that complication is a consequence of local dose-response of non-interacting subunits, the following NTCP-function can be derived based on Poissonian statistics (24):

| (7) |

with a reference dose D0 (or a dose D50 causing 50% complication probability) and a volume-effect (steepness) parameter a. The EUD is given by Eq. (2), where according to this model the exponent of EUD and the steepness parameter of the NTCP function have the same value. Thus, unlike the Lyman- and Logit-EUD models, the Poisson-EUD model has only two parameters.

2.2.5 Mean dose logistic regression model

An association of the rectal mean dose with chronic rectal bleeding has been reported by some authors (7, 8). To test for such an association based on our data, we used logistic regression as a standard method from statistics for this purpose. In terms of the general NTCP model scheme presented above, here the NTCP function is given by the two-parametric logistic function

| (8) |

with the mean dose as summary measure μ. Note that Dmean is a special case of the EUD, Eq. (2), for fixed parameter a=1. Thus this model only has the two parameters β0 and β1.

2.2.6 Cutoff dose logistic regression model

In classical, i.e. non-biological treatment planning approaches, dose limitation to organs at risk (OAR) is usually implemented in terms of dose-volume constraints. For a given treatment-technique, the most relevant dose level(s) predictive for toxicity can be determined by retrospectively fitting a sigmoid type NTCP function to outcome data of a patient population. In this phenomenological approach the summary measure μ is given by the proportion VDc of the OAR receiving doses equal to or above a (cutoff) dose level Dc In the present study VDc is regarded as relative volume, formally: where vi is the discretized form of the differential DVH, and only dose bins i with Di ≥ Dc are used in the sum.

For given value Dc we used logistic regression (Eq. 8) to test for correlation of VDc and chronic rectal bleeding, resulting in two fit parameters β0 and β1. This was systematically repeated for all possible Dc up to 85 Gy in increments of 0.1 Gy to assess the significance of such an logistic regression model for different cutoff doses. Thus altogether the model has the three parameters Dc, β0 and β1.

2.3 Fitting procedure

The method of choice for fitting such models to sparse, dichotomous response data (‘0’/‘1’, if patient shows bleeding of grade < 2 or ≥ 2, respectively) is maximum likelihood estimation (Jackson et al. (25) and references therein; see also (6)). In this method the optimal model parameters are determined such as to maximize the probability of occurrence of the observed data, which is given by the so-called likelihood function L. Due to its smallness, numerically this is usually implemented as maximization of the natural logarithm ln(L), the LogLikelihood LL. In our implementation, the software package Mathematica version 5.0 (Wolfram Research Inc., Champaign, IL) was used for this. To reduce calculation time, the DVH discretization was changed to 0.5 Gy when fitting the Lyman-, Logit-, Poisson-EUD and serial reconstruction unit models.

Uncertainties of the model parameters were assessed using the variance-covariance matrix of the parameters calculated around the maximum of LL as described in (25): The 68% confidence intervals for the parameters can be estimated by the square root of the diagonal elements.

The goodness of fit of each individual model has been quantified in two ways. The first method follows Jackson et al. (25): If the actual (maximized) value of the LogLikelihood for the NTCP model fitted to the observed patient population is denoted by LLobs, the probability P of obtaining a value smaller than LLobs (i.e. a worse fitting model) purely by chance can be assessed based on the statistical distribution of LL. This can be obtained from analytical formulae for the mean <LL> and variance SLL (see Eq. (A3) and (A4) in Jackson et al.) under the assumption of a normally distributed LL. If this probability turns out to be too large, the model ‘overfits’ the data; if it is too small, the model does not fit the data well. According to Rancati et al. (6) values between 30% and 70% indicate a satisfactory fit.

Additionally, a chi-square goodness-of-fit test was performed for each model: A histogram of the observed patient data was calculated, and the resulting group complication rates fi(obs) were compared to the corresponding rates fi(fit) predicted by the respective NTCP model by determining , which approximately follows a chi-square distribution with N-1-n degrees of freedom (N: number of histogram bins; n: number of model parameters).

2.4 Inter-model comparison: Akaike information criterion

A widely used measure allowing to compare competing models is the Akaike information criterion (AIC (26, 27); see also (7)). Generally, for fits of different models to a given dataset a larger likelihood value indicates a better fit to the data. The AIC quantifies the tradeoff between the a model's quality of fit (associated with the likelihood value) and its complexity (expressed by the number of model parameters n), and is defined as AIC = −2LL + 2n. Models with smaller AIC values are considered to provide a better (in the sense of more efficient) fit to the data than models with larger AIC.

3 Results

Of the 319 patients, 45/5/1 (14.1/1.6/0.3%) showed chronic rectal bleeding of grade 2/3/4. Thus altogether 51 patients (16.0%) showed chronic rectal bleeding of grade ≥ 2}, which is the endpoint for the following model fits.

3.1 EUD-based models, mean dose model

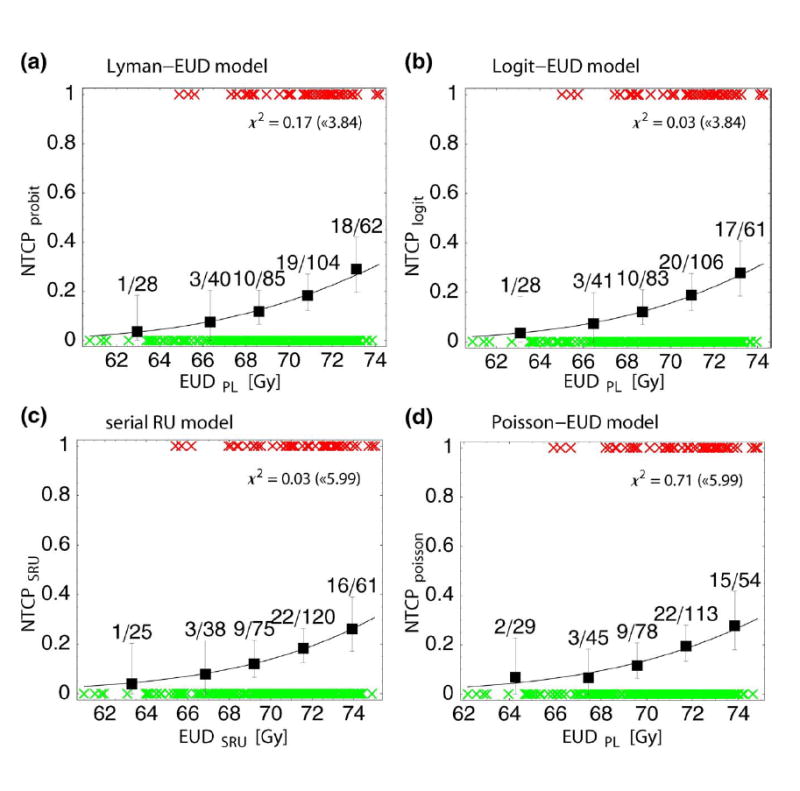

Parameter estimates and their 68% CIs for the Lyman-, Logit-, Poisson-EUD and serial reconstrunction unit model are given in Tab. 2. The plots of the corresponding NTCP-curves are shown in Fig. 1a-d. As obvious in these plots by comparison with the observed complication rates, all four models fit the data very well. Quantitatively, this is manifest by the small values of x2: As example, the fit of the serial reconstruction unit model (Fig. 1c) resulted in a x2 of 0.03, where the upper limit of x2 for an acceptable fit is 5.99 according to chi-square statistics (2 degrees of freedom; α=0.05). As described in section 2.3, the goodness of fit was also determined based on the LogLikelihood LL, <LL> and SLL. These values together with the resulting probability P of obtaining a smaller LL are given in Tab. 2. Again, for all four models P indicates acceptable fits.

Table 2.

Chronic rectal bleeding grade ≥ 2: Estimated parameter values for the six NTCP models, observed LogLikelihood values, estimated LogLikelihood distribution and resulting probability P of obtaining a smaller LL-value than observed.

| Model | parameter estimates (68% CI) | LL | <LL> ±SLL | P [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lyman-EUD model | a=11.9 ±3.8 | -134.5 | -134.6 ±10.5 | 50.4 |

| m=0.108 ±0.027 | ||||

| D50=78.4 ±2.1 | ||||

|

| ||||

| Logit-EUD model | a=12.1 ±3.8 | -134.5 | -134.5 ±10.5 | 50.0 |

| k=15.4 ±4.5 | ||||

| D50=78.1 ±2.1 | ||||

|

| ||||

| serialRU model | σ=0.179 ±0.047 | -134.5 | -135.6 ±10.6 | 54.0 |

| D0=80.6 ±0.9 | ||||

|

| ||||

| Poisson-EUD model | a=13.5 ±3.8 | -134.5 | -135.6 ±10.6 | 54.1 |

| D50=78.5 ±0.6 | ||||

|

| ||||

| mean dose model | — (model not significant) | -138.9 | — | — |

|

| ||||

| cutoff dose model | ||||

| * Dc=73.7 Gy | β0=-2.88 ±0.34 | -136.1 | -136.1 ±10.7 | 50.0 |

| β1=0.050 ±0.013 | ||||

| * Dc=79.6 Gy | β0=-2.10 ±0.16 | -135.3 | -135.3 ±10.7 | 50.0 |

| β1=0.068 ±0.015 | ||||

Figure 1.

Predicted probability of chronic rectal bleeding of grade ≥ 2 according to the different EUD-based NTCP models: (a) Lyman-EUD model (Eq. 1); (b) Logit-EUD model (Eq. 3); (c) serial reconstruction unit model (Eq. 6); (d) Poisson-EUD model (Eq. 7). NTCP is plotted as function of the corresponding equivalent uniform dose, EUD PL (Eq. 2) or EUDSRU (Eq. 5). The symbols (‘×’) represent toxicity (‘1’/‘0’ for patients with/without toxicity, respectively). For each NTCP-model, the observed toxicity rates are shown in centers of equally sized bins (except for two bins in the low incidence region, which were combined). Errors shown are binomial. x2 of the fit and the upper threshold according to chi-square statistics (α=5%) are given for each model.

Concerning the mean dose logistic regression model, it turns out that Dmean does not significantly correlate to chronic rectal bleeding of grade ≥ 2 (p=0.11). The worse fit quality of this model in comparison with the four above mentioned EUD-based models is also expressed by its significantly lower LogLikelihood value (Tab. 2). Thus this model is not considered further in the following.

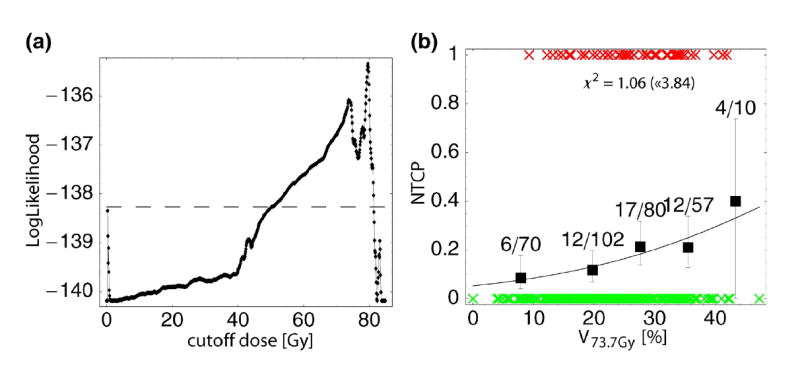

3.2 cutoff dose model

Fig. 2a shows the LogLikelihood values of different logistic regression model fits when varying the cutoff dose Dc. For all dose levels in the range Dc ∼ 50–80 Gy a significant correlation (α<0.05) of the relative volume irradiated with doses ≥ Dc and chronic rectal bleeding of grade ≥ 2 was found for our patient population. The curve has maxima at Dc =73.7 Gy and 79.6 Gy. Fig. 2b depicts the model fit for Dc = 73.7 Gy: As obvious, the fit quality is slightly worse than for the EUD-models. However, both the value of P in Tab. 2 and a x2 of 1.06 (upper limit according to chi-square statistics (1 degree of freedom, α=0.05): 3.84) show that the fit is acceptable. Formally, this is also the case for the model with Dc = 79.6 Gy (plot not shown; x2=2.24 < 3.84). However, as only a part of our patient population receives doses above 79.6 Gy to non-vanishing volumes of rectal wall, the distribution of the summary measure V79.6Gy itself is strongly shifted to small values, thereby compromising the statistical strength of the patient dataset in the region of larger V79.6Gy.

Figure 2.

Cutoff-dose logistic regression model of chronic rectal bleeding grade ≥ 2: (a) Values of LogLikelihood in dependence of the cutoff dose Dc; models with LL above the dashed horizontal line reach a significance level of α<0.05. (b) Predicted probability of bleeding according to the model for Dc = 73.7 Gy (local maximum of LL according to (a)), plotted as a function of the rel. volume receiving at least 73.7 Gy.

3.3 Comparison of the models

Both visually from Fig. 1 and according to the LogLikelihood values in Tab. 3 the four EUD-based NTCP models fit the data of chronic rectal bleeding of grade ≥ 2 equally well. However, as the Akaike information criterion shows, both 2-parametric NTCP models (serial reconstruction unit model and Poisson-EUD model) have the lowest AIC-values ( Tab. 3) and thus can be considered to fit the data most efficiently.

Table 3.

Comparison of the NTCP models using the Akaike information criterion (AIC value). n denotes the number of model parameters. [*model not significant (p>0.05)]

| Model | n | LL | AIC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lyman-EUD model | 3 | -134.54 | 275.1 |

| Logit-EUD model | 3 | -134.51 | 275.0 |

| serialRU model | 2 | -134.53 | 273.1 |

| Poisson-EUD model | 2 | -134.55 | 273.1 |

| mean dose model | 2 | -138.89* | —* |

| cutoff dose model (73.7 Gy) | 3 | -136.08 | 278.2 |

| cutoff dose model (79.6 Gy) | 3 | -135.34 | 276.7 |

Compared to these models, the AIC-values of the two cutoff-dose models (Dc = 73.7 Gy and 79.6 Gy) are considerably larger, which is both due to the smaller LogLikelihood values (indicating worse fit quality itself) and the larger number of model parameters. Thus the EUD-based models provide a quantitatively better and more efficient description of our dataset.

4 Discussion and conclusions

In this study six dose-volume based or EUD-like NTCP models were fitted to late rectal bleeding data of a large, consistently treated patient population (319 patients), thereby aiming to identify the most accurate approach for quantifying the risk of chronic rectal bleeding based on planned dose distributions of rectum and allowing statistically robust estimation of the corresponding model parameters.

Our results clearly confirm the volume effect for chronic rectal bleeding of grade 2 or worse. Quantitatively, this can be described very well with the four EUD-like models, where the serial reconstruction unit and the Poisson-EUD model fitted the data most efficiently according to the Akaike information criterion (smallest AIC values), as they need only two parameters to describe the dataset. Thus according to our data, these two models can be considered to provide the most concise approach to quantifying the risk of chronic rectal bleeding of grade 2 or worse. The cutoff-dose model, a directly dose-volume based model, generally fitted the data worse, but still found significant correlation of rectal wall relative volume above single cutoff-dose levels Dc in the range ∼ 50–80 Gy (most significant for Dc =73.7 and 79.6 Gy) for our patient population. Mean dose did not correlate to late rectal bleeding of grade ≥ 2.

For the three models incorporating the power-law EUD (Eq. 2), i.e. the Lyman-, Logit- and Poisson-EUD model, the parameter describing the volume effect was found to be in the order of a ≈ 12, see Tab. 2. Accounting for uncertainties in parameter estimation this is consistent to Burman et al. (5), who found n ≈ 0.12 (different definition of volume effect parameter: a = 1/n, i.e. a = 8.3). It is also in agreement with the data published by Skwarchuk et al. (28) which yield a = 10.3 (fit based on Fig. 3 of the cited paper). However, it is in contradiction to findings of Rancati et al. (6) (a = 4.3, 68% CI ∼ 3.6–5.6) and Tucker et al. (7) (a = 0.3, with large uncertainty a ∼ 0–32.3 (95% CI)).

Due to the ART-protocol used, which defined different prescription dose levels depending on individual organ geometry and mobility, the patient population shows a wide range of DVH shapes and thus large variability of dose/volume combinations, which is advantageous for robust fitting of NTCP models. However, possible statistical biases are introduced by the treatment technique and specific characteristics of the patient population itself.

This is indeed the case as becomes most evident for the results of the cutoff-dose model, Fig. 2a: The (local) maxima of the LogLikelihood at Dc = 73.7 and 79.6 Gy are strongly influenced by the different prescription dose levels defined by the ART protocol (70.2, 72, 73.8, 75.6, 77.4 and 79.2 Gy), while the finding that all models with Dc in the range ∼ 50–80 Gy are formally significant can be traced back to the 4-field box treatment technique used, which induces correlations of all DVH dose-bins in this range. Quantitatively, such correlations can be assessed by principal component analysis (PCA, (29, 30)); a detailed investigation of the use of DVH-PCA in the context of NTCP-modelling will be presented in a subsequent publication.

In this context a comparison with results from other publications is elucidating: Both Jackson et al. (2) and Tucker et al. (7) found significant correlations of intermediate doses ∼ 40–45 Gy with toxicity in contradiction to our findings. This is likely due to differences in the treatment technique (6-field 3D-CRT versus 4-field box in combination with 6-field 3D-CRT boost), which induces specific correlations between dose-bins. Thus an important conclusion is that results of DVH-based models like the cutoff-dose model are superimposed by characteristics of the treatment technique and patient population, which compromises inferences about radiobiological effects and extrapolability of results gained from a certain treatment technique to others.

Concerning the mean dose model, our results are in contrast to the studies of Zapatero et al. (8), Tucker et al. (7), who found a correlation of mean dose and chronic rectal bleeding of grade ≥ 2. Again, this might be due to differences in the treatment technique or the grading scheme used (to mention, grade ≥ 3 bleeding correlated to mean dose for our population (p=0.045; data not shown))

Concerning the magnitude of the volume effect for rectum, our results can be compared to values published for other organs (5): Lung (a ≈ 1.1) and liver (a ≈ 3.1) are typical organs with a large volume effect, while e.g. spinal cord shows only a small volume effect (a ≈ 20.0). Thus for our data, the EUD-like models suggest a rather small volume effect of rectal bleeding (a ≈ 13.5 for the Poisson-EUD model, see Tab. 2). As illustration of this, a plan should not have more than 2.4% (1.7%) of rectal volume irradiated with 80 Gy (82 Gy) to have the same EUD (and thus same NTCP) as an otherwise identical plan with 72 Gy to 10% of the volume.

If the presented EUD-based models are used for dose optimisation, e.g. for IMRT dose escalation, it is always preferrable to err towards smaller volume effects. In consequence, a EUD-based optimisation of prostate radiotherapy with the parameters derived here will severely penalize high dose regions in the rectum, perhaps for some patients to an extent that prevents satisfying PTV coverage. Hence, the data suggest that safe dose escalation to the prostate can only be achieved by image guided and adaptive strategies to reduce the extent of the PTV.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Deutsche Krebshilfe e.V. grand No. 106280 and NIH grand No. RO1 CA091020.

Footnotes

This work will be presented in part at the 48th Annual ASTRO Meeting, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, November 5–9, 2006.

Conflict of Interest Notification

No conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Boersma LJ, van den Brink M, Bruce AM, et al. Estimation of the incidence of late bladder and rectum complications after high-dose (70–78 Gy) conformal radiotherapy for prostate cancer, using dose-volume histograms. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;41(1):83–92. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00037-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson A, Skwarchuk MW, Zelefsky MJ, et al. Late rectal bleeding after conformal radiotherapy of prostate cancer (II): volume effects and dose-volume histograms. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;49(3):685–698. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)01414-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vargas C, Martinez A, Kestin LL, et al. Dose-volume analysis of predictors for chronic rectal toxicity after treatment of prostate cancer with adaptive image-guided radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62(5):1297–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peeters STH, Lebesque JV, Heemsbergen WD, et al. Localized volume effects for late rectal and anal toxicity after radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64(4):1151–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burman C, Kutcher GJ, Emami B. Fitting of normal tissue tolerance data to an analytic function. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;21(1):123–135. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90172-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rancati T, Fiorino C, Gagliardi G, et al. Fitting late rectal bleeding data using different NTCP models: results from an Italian multi-centric study (AIROPROS0101) Radiother Oncol. 2004;73(1):21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tucker SL, Cheung R, Dong L, et al. Dose-Volume Response analysis of late rectal bleeding after radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59(2):353–365. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2003.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zapatero A, García-Vicente F, Modolell I, et al. Impact of mean rectal dose on late rectal bleeding after conformal radiotherapy for prostate cancer: Dose-volume effect. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59(5):1343–1351. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peeters STH, Hoogeman MS, Heemsbergen WD, et al. Rectal bleeding, fecal incontinence, and high stool frequency after conformal radiotherapy for prostate cancer: Normal tissue complication probability modeling. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66(1):11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu Q, Mohan R, Niemierko A, et al. Optimization of intensity-modulated radiotherapy plans based on the equivalent uniform dose. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52(1):224–235. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)02585-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bär W, Schwarz M, Alber M, et al. A comparison of forward and inverse treatment planning for intensity-modulated radiotherapy of head and neck cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2003;69(3):251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bos LJ, Schwarz M, Bär W, et al. Comparison between manual and automatic segment generation in step-and-shoot IMRT of prostate cancer. Med Phys. 2004;31(1):122–130. doi: 10.1118/1.1634481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vargas C, Yan D, Kestin LL, et al. Phase II dose escalation study of image-guided adaptive radiotherapy for prostate cancer: Use of dose-volume constraints to achieve rectal isotoxicity. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63(1):141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martinez AA, Yan D, Lockman D, et al. Improvement in dose escalation using the process of adaptive radiotherapy combined with three-dimensional conformal or intensity-modulated beams for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;50(5):1226–1234. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)01552-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan D, Lockman D, Brabbins D, et al. An off-line strategy for constructing a patient-specific planning target volume in adaptive treatment process for prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;48(1):289–302. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)00608-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyman JT. Complication probability as assessed from dose-volume histograms. Radiat Res. 1985;104:S13–S19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kutcher GJ, Burman C. Calculation of complication probability factors for non-uniform normal tissue irradiation: the effective volume method. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;16(6):1623–1630. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(89)90972-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kutcher GJ, Burman C, Brewster L, et al. Histogram reduction method for calculating complication probabilities for three-dimensional treatment planning evaluations. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1991;21(1):137–146. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(91)90173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyman JT, Wolbarst AB. Optimization of radiation therapy, III: A method of assessing complication probabilities from dose-volume histograms. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1987;13(1):103–109. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(87)90266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lyman JT, Wolbarst AB. Optimization of radiation therapy, IV: A dose-volume histogram reduction algorithm. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;17(2):433–436. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(89)90462-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niemierko A. A generalized concept of Equivalent Uniform Dose [Abstract] Med Phys. 1999;26(6):1100. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohan R, Mageras GS, Baldwin B, et al. Clinically relevant optimization of 3-D conformal treatments. Med Phys. 1992;19(4):933–944. doi: 10.1118/1.596781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alber M, Belka C. A normal tissue dose response model of dynamic repair processes. Phys Med Biol. 2006;51(1):153–172. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/51/1/012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alber M, Nüsslin F. A representation of an NTCP function for local complication mechanisms. Phys Med Biol. 2001;46(2):439–447. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/46/2/311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jackson A, Haken RKT, Robertson JM, et al. Analysis of clinical complication data for radiation hepatitis using a parallel architecture model. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31(4):883–891. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)00471-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akaike H. Information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. In: Petrov BN, Csaki F, editors. Second international symposium on information theory. Budapest: Academiai Kaido; 1973. pp. 267–281. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akaike H. A new look at statistical model identification. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control. 1974;19(6):716–723. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skwarchuk MW, Jackson A, Zelefsky MJ, et al. Late rectal toxicity after conformal radiotherapy of prostate cancer (I): multivariate analysis and dose-response. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;47(1):103–113. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00560-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dawson LA, Biersack M, Lockwood G, et al. Use of principal component analysis to evaluate the partial organ tolerance of normal tissues to radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62(3):829–837. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Söhn M, Yan D, Liang J, et al. Influence of Dose Volume Histogram (DVH) Pattern on Rectal Toxicity [Abstract] Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63 (Suppl. 1):S58–S59. [Google Scholar]