T cells that respond to self antigens exist in normal tissues but are, of necessity, stringently controlled in healthy individuals. Autoreactive T cells may be specifically deleted as they develop in the thymus; those that survive and reach the peripheral tissues are kept mitotically quiescent and otherwise unresponsive by stimuli from other immune cells. Together, these two mechanisms, termed central and peripheral tolerance, hold autoreactive T cells in check. Autoimmune disease arises when clones of these cells overcome the usual safeguards, expand, and become activated.

The mechanism behind such an escape from tolerance is uncertain, and defects in both central and peripheral tolerance have been proposed to underlie various disorders. Now, two independent sets of reports establish that both of these mechanisms participate in the pathogenesis of an unusual form of immune disregulation observed in humans and mice. The human disorder, X-linked autoimmunity–allergic disregulation syndrome (XLAAD), presents with a collection of symptoms that are also seen in the Scurfy mouse. With the report by Chatila et al. (1) in a recent issue of the JCI and independent analyses by Brunkow et al. (2), it is now clear that the genes affected are orthologues and encode a transcription factor termed Foxp3, JM2, or scurfin. This parallel offers the prospect of insights into the molecular regulation of human autoimmune diseases. The current findings also suggest that certain allergic diseases arise because of intrinsic defects in CD4+ T cells, leading to Th2-skewing and hyperreactivity to antigens.

Characteristics of XLAAD and Scurfy

XLAAD is an X-linked disease that presents early in life with a syndrome of autoimmunity, allergy, and failure to thrive. It was first described as an X-linked immunodeficiency syndrome associated with polyendocrinopathy (type 1 diabetes mellitus and autoimmune thyroiditis), hemolytic anemia, chronic diarrhea (autoimmune), and eczema (3, 4). While the autoimmune manifestations are prominent, children with XLAAD also suffer from allergic manifestations with severe eczema, elevated IgE levels, eosinophilia, and food allergy (3). As Chatila et al. (1) show, activated PBMCs from affected individuals are skewed toward the Th2 phenotype, expressing high levels of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13, but low levels of IFN-γ. Indeed, even the resting cells from affected individuals are activated compared to those from normal individuals, as measured by their expression of Th2 cytokines.

The immunodeficiency associated with this disorder is variable. While most affected boys die within the first year of life due to recurrent infections, it is not clear that the recurrent infections arise because of a true immune deficiency, rather than a constellation of factors such as metabolic activation, diarrhea, and malnutrition. Several studies have shown variable immune function with generally normal leukocyte numbers, lymphocyte subsets, and T-cell proliferation. Many of the affected children have hypogammaglobulinemia with low IgG and IgA levels, but this may be explained by persistent diarrhea with a protein-losing enteropathy. Because of the variability in presentation, this syndrome mapping in each case to the pericentromeric region of the X chromosome (Xp11.23-Xq13.3) has been referred to as X-linked polyendocrinopathy, immune dysfunction, and diarrhea (XPID) and X-linked autoimmunity-immunodeficiency syndrome (XLAID) as well as XLAAD (5, 6).

Scurfy shares many features with XLAAD in that it is an X-linked mouse mutant characterized by early lethality, T-cell hyperactivity, eczema, diarrhea, severe anemia, and cytokine overproduction (7–9). In both XLAAD and Scurfy, the carrier females are unaffected. Unlike XLAAD, Scurfy is associated with hypergammaglobulinemia. Early death in these animals is thought to be due to a wasting syndrome, not immunodeficiency, induced by the overproduction of cytokines including TNF-α, GM-CSF, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, and IL-7 (9–11).

Foxp3/JM2 mutations in XLAAD and Scurfy mice

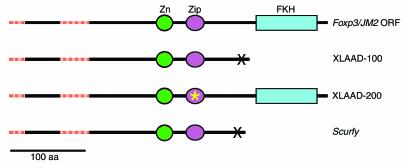

The studies of Chatila et al. (1) show that two XLAAD kindreds have mutations in JM2, a gene identified as a part of the human genome sequencing project that encodes a protein belonging to the fork head family of transcription factors (GenBank accession no. AF235097 and NM_014009). Brunkow et al. (2) have also performed extensive positional cloning studies that define the mutation in Scurfy to be within the mouse homologue of JM2. For reasons related to the bioinformatics methods used, the two groups predict different mRNA structures for human scurfin. The correct sequence, however, is likely a 1296 bp open reading frame encoding a 431 amino acid protein of approximately 47 kDa (Figure 1), but this remains to be proven. The predicted protein contains a winged helix (fork head homology domain [FKH]) motif at the carboxy terminus (1, 2) and a C2H2 zinc finger domain (Zn) (2) and a 3-heptad Zip motif (1) upstream of the FKH. In keeping with the accepted nomenclature for winged helix proteins, the gene encoding scurfin has been named Foxp3 (2).

Figure 1.

Schematic of the normal and mutant products of the Foxp3/JM2 gene, indicating the mutations that lead to XLAAD and Scurfy. Regions of the Foxp3 open reading frame (ORF) found by cDNA sequencing and not predicted by the exon prediction programs of the human genome project (HGP) are shown by hatched red bars. This additional NH2-terminal sequence is encoded in part by an additional 5′ exon, as noted by Brunkow et al. (2). Chatila et al. (1), following the HGP-annotated sequence, predicted a shorter NH2-terminal domain. The mutant protein in the XLAAD-100 family and Scurfy mice are truncated at similar positions, whereas the mutant protein in the XLAAD-200 family carries a single amino acid deletion in the Zip domain. Zn, Zinc-finger domain; Zip, Zip motif; FKH, fork head homology domain.

The mutations identified in the XLAAD-100 kindred and Scurfy mouse carry frameshift mutations at neighboring positions, mapping between the Zip domain and FKH. If the encoded mRNAs survive nonsense-mediated decay, they are predicted to yield similar truncated proteins. In any case, these mutations behave as true null alleles, since overexpression of the mutant scurfin has no effect (2), and female carriers of the mutation are normal (1, 2). The in-frame deletion found in the XLAAD-200 kindred might be expected to interfere with homo- or heterodimerization, and its biochemical effects are harder to predict, but it appears to cause the same loss of function as do the other alleles. Crucially, expression of wild type Foxp3 in a Scurfy background prevents disease (11), establishing that the Scurfy mouse is an appropriate animal model for XLAAD, and that analysis of this mutant strain may provide insights into the mechanisms of autoimmunity and allergy and provide a system to test new methods for treatment.

Central and peripheral defects in Scurfy T-cell maturation

In Scurfy mice, both central (thymic) and peripheral mechanisms of tolerance appear to be defective. Mice that are both Scurfy and nude (athymic) are free of autoimmune and allergic symptoms, consistent with a key role for T cells as effector cells in the disease. Moreover, adoptive transfer of Scurfy CD4+ T cells into H2-compatible athymic nude or SCID mice induces a Scurfy-like phenotype (10, 12). Interestingly, transplantation of Scurfy bone marrow into lethally-irradiated recipients reconstitutes all lymphoid organs with cells of this genotype but does not recreate the disease. On the basis of these and similar experiments using thymic transplantation, Godfrey et al. (12, 13) argued that although Scurfy CD4+ T cells are sufficient to confer the immune defect, these cells must mature in a Scurfy thymus if they are to be autoreactive and cause disease (12). Thus, some defect in the thymic microenvironment of Scurfy animals apparently allows Scurfy T cells to escape central tolerance.

Once autoreactive Scurfy T cells reach the periphery, they are intrinsically hyperresponsive to antigenic stimulation. Circulating Scurfy T cells overproduce cytokines and have an activated phenotype, expressing CD44, CD69, CD25, CD80, and CD86 (10, 11). Zahorsky-Reeves and Wilkinson (14) have shown that Scurfy T cells require antigenic stimulation to confer the Scurfy phenotype. These authors introduced the Scurfy mutation onto a transgenic, Rag1-deficient background in which all of the Scurfy T cells express a T-cell receptor (TCR) for, and respond only to, a specific antigenic determinant in chicken ovalbumin (OVA). Unless exposed to this peptide, these Scurfy/OVA/Rag1 mice are completely disease free, indicating that Scurfy T cells must be triggered by a suitable endogenous or exogenous antigen if they are to cause disease (14). When triggered by anti-TCR stimulation or, presumably, by endogenous antigens, Scurfy CD4+ T cells are hyperresponsive and have a decreased requirement for costimulation through CD28 (11). Thus, stimuli that would normally induce peripheral T-cell tolerance (TCR stimulation in the absence of costimulation) could serve to stimulate the Scurfy T cells. Crucially, the Scurfy phenotype is absent in animals that are mixed chimeras for Scurfy and normal leukocytes (J.E. Wilkinson, personal communication), indicating that Scurfy T cells may be defective in their ability to regulate immune responses, but that their hyperresponsiveness can be suppressed by normal cells. Thus, Scurfy T cells are hyperresponsive to antigenic stimuli, have defective peripheral tolerance, and cannot appropriately downregulate immune responses.

Implications for treatment of XLAAD

Despite the global CD4+ T-cell hyperresponsiveness, Scurfy mice, like children with XLAAD, are afflicted with only specific autoimmune diseases. Based on the requirement for antigenic stimulation, it is likely that the autoimmune diseases that develop in XLAAD do so because of escape in central tolerance to those antigens, exposure to those antigens in the periphery, and ineffective peripheral tolerance to those antigens. It is possible that autoimmune diabetes and thyroiditis develop because the antigens are abundant and accessible, but other mechanisms may also contribute. Antigen expression in the thymus by thymic antigen-presenting cells is one of the mechanisms of central tolerance. For type 1 diabetes mellitus, the IDDM2 susceptibility locus is associated with decreased insulin expression in the thymus (15). An intriguing possibility is that scurfin controls the expression of certain autoantigens in the thymus and that its absence allows cells reactive to those antigens to escape into the periphery, where they expand and cause disease in response to antigen exposure.

The current treatment options for XLAAD are limited to immunosuppressive agents and supportive care, with death usually occurring within the first year of life. Consistent with the decreased sensitivity of Scurfy T cells to cyclosporin A, cyclosporin is often not effective in controlling XLAAD (6, 11). One of the most intriguing observations in the Scurfy mouse is that normal cells can control Scurfy T cells and prevent disease manifestation. Thus, using minimally toxic, nonmyeloablative conditioning regimens followed by transplantation of normal allogeneic stem cells (sometimes termed “mini-transplants”, or “transplant-lite”) (16, 17) to induce mixed chimerism may be an effective treatment strategy for XLAAD. Alternatively, XLAAD may be one of the diseases that respond well to gene therapy, since a small percentage of wild-type T cells may be sufficient to control the disease.

References

- 1.Chatila TA, et al. JM2, encoding a fork head–related protein, is mutated in X-linked autoimmunity–allergic disregulation syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:R75–R81. doi: 10.1172/JCI11679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brunkow, M.E., et al. 2001. Disruption of a novel forkhead/winged helix protein, scurfin, results in the rapidly fatal lymphoproliferative disorder of the scurfy mouse. Nat. Genet. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Powell BR, Buist NR, Stenzel P. An X-linked syndrome of diarrhea, polyendocrinopathy, and fatal infection in infancy. J Pediatr. 1982;100:731–737. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(82)80573-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Satake N, et al. A Japanese family of X-linked auto-immune enteropathy with haemolytic anaemia and polyendocrinopathy. Eur J Pediatr. 1993;152:313–315. doi: 10.1007/BF01956741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett CL, et al. X-Linked syndrome of polyendocrinopathy, immune dysfunction, and diarrhea maps to Xp11.23-Xq13.3. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:461–468. doi: 10.1086/302761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferguson PJ, et al. Manifestations and linkage analysis in X-linked autoimmunity-immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 2000;90:390–397. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(20000228)90:5<390::aid-ajmg9>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lyon MF, Peters J, Glenister PH, Ball S, Wright E. The scurfy mouse mutant has previously unrecognized hematological abnormalities and resembles Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2433–2437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Godfrey VL, Wilkinson JE, Russell LB. X-linked lymphoreticular disease in the scurfy (sf) mutant mouse. Am J Pathol. 1991;138:1379–1387. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kanangat S, et al. Disease in the scurfy (sf) mouse is associated with overexpression of cytokine genes. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:161–165. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blair PJ, et al. CD4+CD8- T cells are the effector cells in disease pathogenesis in the scurfy (sf) mouse. J Immunol. 1994;153:3764–3774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark LB, et al. Cellular and molecular characterization of the scurfy mouse mutant. J Immunol. 1999;162:2546–2554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Godfrey VL, Wilkinson JE, Rinchik EM, Russell LB. Fatal lymphoreticular disease in the scurfy (sf) mouse requires T cells that mature in a sf thymic environment: potential model for thymic education. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5528–5532. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Godfrey VL, Rouse BT, Wilkinson JE. Transplantation of T cell-mediated, lymphoreticular disease from the scurfy (sf) mouse. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:281–286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zahorsky-Reeves, J.L., and Wilkinson, J.E. 2001. The murine mutation scurfy (sf) produces a severe lymphoproliferative disease which is antigen dependent in nature. Eur. J. Immunol. In press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Pugliese A, et al. The insulin gene is transcribed in the human thymus and transcription levels correlated with allelic variation at the INS VNTR-IDDM2 susceptibility locus for type 1 diabetes. Nat Genet. 1997;15:293–297. doi: 10.1038/ng0397-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khouri IF, et al. Transplant-lite: induction of graft-versus-malignancy using fludarabine-based nonablative chemotherapy and allogeneic blood progenitor-cell transplantation as treatment for lymphoid malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2817–2824. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.8.2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slavin S, et al. Nonmyeloablative stem cell transplantation and cell therapy as an alternative to conventional bone marrow transplantation with lethal cytoreduction for the treatment of malignant and nonmalignant hematologic diseases. Blood. 1998;91:756–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]