Abstract

Objective

To investigate parents' perspectives on the desirability, content and conditions of a physician-parent conference after their child's death in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU).

Study design

Audio-recorded telephone interviews were conducted with 56 parents of 48 children. All children died in the PICU of one of six children's hospitals in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network 3-12 months prior to the study.

Results

Only 7 (13%) parents had a scheduled meeting with any physician to discuss their child's death; 33 (59%) wanted to meet with their child's intensive care physician. Of these, 27 (82%) were willing to return to the hospital to meet. Topics that parents wanted to discuss included the chronology of events leading to PICU admission and death, cause of death, treatment, autopsy, genetic risk, medical documents, withdrawal of life support, ways to help others, bereavement support, and what to tell family. Parents sought reassurance and the opportunity to voice complaints and express gratitude.

Conclusions

Many bereaved parents want to meet with the intensive care physician after their child's death. Parents seek to gain information and emotional support, and to give feedback about their PICU experience.

Keywords: bereavement, grief, critical care, communication, interview

In the U.S., 53,000 children die annually.1 Most of these deaths occur in inpatient hospital settings, primarily intensive care units.2,3 Pediatric intensive care physicians are extensively involved in the care of dying children and their families.4 Such care includes communicating poor prognoses, treating pain and other symptoms, advising on decisions regarding life support, requesting permission for autopsy and initiating organ donation. In managing the child's death, intensive care physicians have a unique opportunity to help parents prepare for the death and begin a grief process that enables the family to remain functional and intact.

Previous studies have documented the need for greater parental support following the death of a child and better physician training to provide such support.5-13 Bereaved parents have expressed the need for comprehensive information regarding their child's illness and death, emotional support and consistent follow-up by their child's physicians.5-9 Professional organizations such as the American Academy of Pediatrics, the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, and the Society of Critical Care Medicine suggest that physician-parent meetings to discuss the death and review autopsy results may help meet families' needs during bereavement.14-16 However, evidence regarding parents' desire for such meetings, the most appropriate time and place, the topics to be discussed, and the participants to be involved is lacking. The paucity of evidence and inadequate training may contribute to physicians' reluctance to meet with parents after a child's death.

Family perspectives must be strongly considered when planning supportive interventions during the complex experience of bereavement. The objective of this study was to investigate parents' perspectives regarding the desirability, content and conditions of a physician-parent conference conducted after their child's death in the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU).

Methods

Setting

The Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network (CPCCRN) established by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development consists of six clinical centers and a data coordinating center.17 Pediatric intensive care physicians have primary responsibility for the care of all medical patients and routinely provide consultation on surgical patients in the PICU at each center.

Participants

Parents or legal guardians were eligible to participate if their child died in the PICU at one of the CPCCRN sites between 3 and 12 months prior to the start of the study. The medical records of the deceased children were reviewed to obtain the parents' contact information and primary language.18 Parents who did not speak English or Spanish were excluded. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at each site. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Recruitment

Parents were contacted consecutively beginning with those whose child died 12 months earlier. Initial contact occurred via a mailed letter that originated from the hospital where the child died. The letter asked parents to participate in a research interview. Parents were telephoned two weeks later to explain the details of the study and schedule interviews. If both parents of one child agreed to participate, separate interviews were scheduled.

Interviews

A committee of CPCCRN investigators developed an interview guide to elicit parents' experiences with and perceptions about meeting with their child's intensive care physician after their child's death. The interview guide was based on the bereavement literature19-23 and the clinical experience of the investigators. Spanish versions of the interview guide were developed by forward and back translation. To standardize interview procedures, interviewers participated in training sessions that included didactics, modeling of interview techniques, role-playing and feedback.

Interviews were conducted between January 19, 2006 and May 22, 2006 by research assistants from the clinical centers where the children died. Interviews were conducted in English or Spanish over the telephone and were digitally audio-recorded. Parents responded to questions about their contacts with hospital personnel since their child died; their desire to meet with their child's intensive care physician; and the preferred timing, location, participants and topics for such a meeting. Parents also ranked the importance of predefined topics and provided demographic information. Parents were asked to respond to all questions in the interview guide. If a parent indicated that he or she would not want to have a physician-parent conference, the parent was asked to explain the reason why not, and to respond hypothetically to further questions about the meeting. Parents selected their race and ethnicity from a predefined list in order to assess sample diversity. All interviews were monitored by one of two investigators (KM, SE) who provided feedback to the interviewer to maintain standardization and quality.

Medical record review

Medical records of the deceased children of participating parents were reviewed to obtain the child's age, sex, trajectory of death, mode of death, and length of PICU and hospital stay. Mode of death was categorized as limitation of therapy, withdrawal of therapy, brain death, or death despite cardiopulmonary resuscitation.24

Data analysis

Analysis was ongoing during data collection and interviews were conducted until saturation was reached.25 Two investigators, a pediatric intensive care physician (KM) and a behavioral scientist with expertise in health communication (SE), analyzed the interviews. The behavioral scientist is bilingual; the physician analyzed the Spanish interviews with the assistance of a translator. The two investigators listened to each interview independent of each other and wrote detailed notes on parents' responses to the questions.26 Responses to select questions were transcribed verbatim. Displays of emotion (e.g., crying) were noted. The two investigators compared their notes for accuracy and generated a combined data set. Discrepancies between investigators were resolved by listening to the audio recording together and reaching consensus. A member of the data coordinating center reviewed 20% of the interviews with representation from each site to confirm the accuracy of the data set.

The data set was imported into a qualitative analysis software program (QSR N6, QSR International Pty Ltd, Doncaster, Australia) to facilitate data management. The two investigators used an iterative process to identify themes pertaining to the content and conditions of the physician-parent conference. This process included independent reading of the data set to identify themes; comparison of themes between investigators; re-reading of the data set and discussion to refine themes and reach consensus on their meaning. Exemplars were taken from the transcribed sections of the interviews. To enhance the validity of the thematic analysis, two bereaved parents reviewed the manuscript to provide their opinions as to whether parents' views were appropriately represented. Categorical data were described as absolute counts and percentages; continuous data as medians and ranges.

Results

Parents of 161 deceased children were sent letters explaining the study; 56 parents of 48 children (30% of families) were interviewed, parents of 33 children (20%) refused, and parents of 79 children (49%) could not be contacted by telephone. One mother (1%) agreed to participate and was interviewed but the recording device malfunctioned and the interview was lost (Tables I and II). Parents were interviewed a median of 8 months (range 4–15 months) after their child's death. Five interviews were conducted in Spanish.

Table I.

Characteristics of Study Parents (N=56)

| Relationship to child, No. (%) | |

| Mother | 37 (66) |

| Father | 17 (30) |

| Other female legal guardian | 2 (4) |

| Race, No. (%) | |

| Black | 7 (13) |

| White | 42 (75) |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 1 (2) |

| Asian | 2 (4) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0 |

| Other or unknown | 4 (7) |

| Ethnicity, No. (%) | |

| Hispanic | 9 (16) |

| Non-Hispanic | 47 (84) |

| Age, median (range), y | 36 (22-57) |

| Marital Status, No. (%) | |

| Married | 39 (70) |

| Single | 17 (30) |

| Education, No. (%)* | |

| Elementary school | 2 (4) |

| High School | 16 (28) |

| College | 29 (52) |

| Post-graduate | 4 (7) |

| Other | 5 (9) |

| Employment, No. (%) | |

| Full-time | 30 (54) |

| Part-time | 3 (5) |

| Homemaker | 14 (25) |

| Other | 9 (16) |

Parents were categorized in the education level for which they had fulfilled any part.

Table II.

Characteristics of Deceased Children (N=48)

| Male sex, No. (%) | 26 (54) |

| Age, median (range), y | 1.6 (0.0-20.8) |

| PICU days, median (range) | 10.5 (1-80) |

| Hospital days, median (range) | 19 (1-130) |

| Trajectory of death, No. (%)* | |

| Sudden, unexpected | 16 (33) |

| Lethal congenital anomaly | 4 (8) |

| Chronic potentially curable disease | 8 (17) |

| Chronic progressive condition with intermittent crisis | 20 (42) |

| Mode of death, No. (%) | |

| Limitation of therapy | 7 (15) |

| Withdrawal of therapy | 22 (46) |

| Brain death | 6 (12) |

| Failed resuscitation | 13 (27) |

Trajectory of death is categorized as described by Field and Behrman.2

Contacts with hospital personnel since the child's death

Thirty-five (63%) parents had spoken with one or more hospital workers since their child's death. Sixteen (29%) parents had contact with a physician; however, only 7 (13%) had a scheduled meeting with a physician to discuss their child's death. Other physician contacts included expressions of condolence via telephone or at memorial services, and chance visits in corridors when parents returned to the hospital for other purposes.

Twenty-five (45%) parents had spoken with a nurse or ancillary health provider. Of these, 13 (52%) parents had spontaneous social visits with staff, and 12 (48%) had planned professional contacts for psychosocial support. Eight (14%) parents had spoken with administrative personnel about hospital billing, charitable donations, or voluntary participation on hospital advisory boards.

Desirability of meeting with an intensive care physician

Thirty-three (59%) parents wanted to meet with their child's intensive care physician, 19 (34%) did not want to meet, 2 (4%) were undecided, and 2 (4%) did not answer the question. Of those who did not want to meet with the intensive care physician, 9 (47%) were satisfied with the information and support provided by the physician before the child's death; 7 (37%) were dissatisfied with the physician's availability and communication skills; 2 (11%) gave no explanation; and one planned to meet with another physician to discuss the child's death. For example, a satisfied parent explained, “They were very informative. When I left the hospital when my son died I knew of everything that I needed to know.” In contrast, a dissatisfied parent said, “They should have been there before she died. After the fact, it's just a little late to discuss it and try to talk about it after she's passed away.”

Place, timing and meeting participants

Of the 33 parents who wanted to meet with the intensive care physician, 27 (82%) were willing to return to the hospital to meet. One parent described, “It would have been difficult but nevertheless I would have come.” Similarly, another parent responded, “Yes, although it's not easy. But I would feel that it's important enough because there are so many questions.” Parents' preferred timing for meeting with the intensive care physician ranged from one day after the death to more than one year. Of those who wanted to meet, 15 (45%) wanted to meet within the first 3 months, 5 (15%) between 3 and 6 months, 4 (12%) between 6 and 12 months, 4 (12%) after one year, 1 (3%) anytime and 4 (12%) were undecided. One parent explained, “Early enough to have any benefit that you could have from it yet not just so close to the grieving time that you're not hearing what anybody's saying anyhow.” Twenty-six parents (79%) wanted their spouse/partner to attend the meeting, 12 (36%) wanted their own parents to attend and 18 (55%) wanted a nurse who had cared for their child to attend. One parent responded, “Somebody you could trust. In my case, maybe my mother.” Another parent said, “I think it would be really helpful to have the primary care nurse there too. They may ask questions in that meeting that you maybe didn't think of from a medical standpoint.”

Among the 23 parents who did not want to meet with the intensive care physician, or were undecided about meeting or did not answer that question, 16 (70%) felt that they would be willing to return to the hospital if they had decided to meet. Nine (39%) felt that the best time for such a meeting would be within the first 3 months, 3 (13%) between 3 and 6 months, 5 (22%) between 6 and 12 months, 2 (9%) after one year, 1 (4%) anytime and 3 (13%) were undecided. Nineteen (83%) wanted to bring their spouse/partner, 5 (22%) wanted to bring their parents and 9 (39%) wanted to invite the child's nurse, if they decided to meet.

Content of the meeting

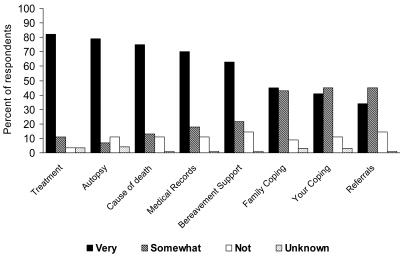

Parents most often mentioned their desire to gain information; next, their desire to provide feedback to the physician regarding their PICU experience; and to a lesser extent their need for emotional support. Informational topics spontaneously mentioned by parents included the chronology of events leading to PICU admission and death, cause of death, treatment, autopsy, genetic risk, medical documents, withdrawal of life support, ways to help others, bereavement support, and what to tell other family members (Table III; available at www.jpeds.com). Parents' ranked responses to questions about the importance of predefined topics showed that information about treatment, autopsy, cause of death, medical records and bereavement support was very important to most parents (Figure).

Table III.

Informational Topics that Parents Want to Discuss with the Intensive Care Physician*

| Topic | Sample Quotation |

|---|---|

| Chronology of events leading to PICU admission and death | “I would just like to clarify what happened. J- was in a regular room and she kind of crashed. By the time I got back to the hospital, she went from being in a regular room to being in ICU and everything was just horrid. At that point, there really wasn't a chance to go, ‘What happened?’” |

| Cause of death | “Nobody ever really told me what was wrong with him. It was some different things that they had said could be but nothing was a fact. I just want to know why he died.” |

| Treatment | “I want to know about her medicines and the different beds they had her in and what role they played and what were they hoping to accomplish by putting her in those beds and with the machines that they used on her.” |

| Autopsy | “We had issues about the autopsy which I would have liked to have explained a little bit more.” |

| Genetic risk | “Is it something genetic? Is it something to look for in my other children?” |

| Medical documents | “The only question that we really had was on his death certificate. It was marked cerebral edema and we're curious as to why that was, rather than marked as actually SIDS. Cause, they said that's exactly what SIDS is, when they quit breathing.” |

| Limitation/withdrawal of life support | “What I'd like to ask is the whole difference between critical care and comfort care. You know we talked about it with the doctor in the conference room, when we made that decision, but that would probably be the topic that I'd want to talk about.” |

| Ways to help others | “My only thing now, is there anything I could do in terms of being there for other parents or helping them in that respect?” |

| Bereavement support | “Maybe talk to them about where you can get help…I think it would be important if they think about telling you what you could do and where you could go.” |

| What to tell other family members | “After the fact, we had a lot of questions asked to us, by our own family. Everybody. We tried answering the best we could but when everything is going on it's really hard to communicate to the rest of the family all the details and everything.” |

Topics are listed in order of decreasing frequency of mention by parents.

Figure 1. Importance of Predefined Discussion Topics.

Parents (N=56) were asked to rank the importance of each discussion topic. Response choices were (1) very important, (2) somewhat important, or (3) not important.

Parents wanted to provide feedback on several aspects of care including physician communication (Table IV; available at www.jpeds.com). Parents frequently perceived that information was withheld during their child's PICU stay, especially regarding prognosis. Other communication issues included callous style, use of medical jargon, and conflicting information from different physicians. Additionally, many parents wanted to express gratitude for the care received, and provide feedback on other health providers, their degree of trust in physicians and the healthcare system, medical errors and administrative issues.

Table IV.

Feedback that Parents Want to Provide to the Intensive Care Physician*

| Topic | Sample Quotation |

|---|---|

| Communication | |

| Withholding prognosis | “It was apparent they knew my baby was dying but none of them quite came out and said ‘your baby's gonna die'…So they knew and that irritated me that they didn't come out and say it.” |

| Callous delivery of “bad news” | “The way the news was delivered to me was horrible. It was very callous. I was not offered a chair. I was not offered a drink of water. I was alone.” |

| Use of medical jargon | “The head of PICU was very helpful in explaining everything in layman's terms.” |

| Conflicting information | “I talked to one doctor and he told me not to have this procedure done this way. And I turned around and the intensive care doctor was doing the procedure that way…I think the doctors need to talk to one another.” |

| Gratitude | “I would really like to thank them and compliment them on how they handled the situation. They were very good about it and they tried to prepare us for everything.” |

| Other providers | “I realize that everywhere you go, there are different personalities, but some of these nurses there, were magnificent. But some of them were just doing it for a paycheck. They are not nurses.” |

| Degree of trust | “Why was they looking guilty when I came in the room, like they done did something to him…? That made me think they killed my baby.” |

| Medical errors | “I would also like to talk about that in the future, when a child is so young and so delicate and also sick, that there should be much more care taken in following medical orders.” |

| Administrative issues | “The complaint process was very weak as well. I submitted 3 written complaints on the forms that are provided by the hospital and I never got any feed back.” |

Topics are listed in order of decreasing frequency of mention by parents.

Emotional support sought by parents included reassurance and the sense that the physician cared about them. One parent explained the need for reassurance, “And like I said, if there was anything else that we could have done. I don't even know if knowing there was something else would be helpful but it's always on your mind. Did we do everything we could have done? Were we good parents? It's more about reassuring.” Another parent described a feeling of abandonment after the death and the need to know that the physician still cared, “It seems like they care so much while it's going on and as soon as it's done they forget about you. You build a pretty good trust with these people for a couple of months of your life and all of a sudden they aren't there. I would have liked my doctor to have at least called me.”

Discussion

Our findings indicate that many parents want to meet with their child's intensive care physician to discuss the death of their child and are willing to return to the hospital to do so. However, our findings also indicate that such meetings rarely occur. Some parents wanted to meet with the physician early after the death, whereas others preferred to wait until the distress of acute grief had begun to subside. Parents envisioned the conference to be a small personal meeting with the intensive care physician and in some cases family members or hospital personnel who had close relationships with their child. Parents sought information about their child's illness and death, the opportunity to provide feedback about their PICU experience, and emotional support. These findings support the published opinions of experienced clinicians and the scant research conducted on physician-family conferences during bereavement in other populations.19,21,22,27-29

The most important component of the physician-parent conference is the provision of information to parents. Parents reported that the emotional turmoil surrounding the child's demise made it difficult for them to comprehend information provided at that time. Information most frequently sought by parents and ranked highest in importance was directly related to the child's treatment and cause of death. Many parents felt that a review of the sequence of events leading to the child's PICU admission and death would help them to make sense of what happened. Medical records and autopsy reports were viewed by parents as additional sources of information that could increase their understanding of their child's treatment and cause of death. Parents also wanted information about the risk of the illness in other children and steps that could be taken towards prevention. Our findings concur with those of Meyer et al which showed that complete and honest information is one of parents' top priorities for quality care of dying children.5-6 Parents continue to seek information after their child's death. Regarding the most appropriate timing for providing such information, social support theory suggests that soon after the death rather than later may be more beneficial. Information provided early on can help parents more accurately appraise the experience of their child's death and their own adaptive capabilities, thereby promoting a healthier response to the loss.30

Feedback that parents wanted to provide to the physician often concerned ineffective communication. Many parents reported that “bad news” was withheld or delivered poorly, leaving them with a sense of betrayal and loss of control. Although some parents believed that information was withheld in order to protect their hope, parents stated that they preferred to hear the truth in order to spare their child and themselves unnecessary suffering. Problems with communication at the end of a child's life have been previously described.5, 7-8,31 In a study by Contro et al,8 families reported the distress they experienced by the uncaring delivery of bad news, callous remarks made by staff, and the receipt of contradictory information about their child's condition and prognosis. In this same study, physicians and staff reported feeling inexperienced in communicating with patients and families about end-of-life issues, and described their own need for greater emotional, psychological and social support when caring for dying patients. In our study, problems with communication during the child's last hospitalization was a common reason given by parents for not wanting to meet with their child's intensive care physician after the death.

Additional feedback that parents wanted to provide included complaints about people or events that they perceived as wrongful. Parents often explained that their negative feedback was intended to prevent other families from experiencing similar problems. Isolated incidents such as callous remarks and preventable oversights in care are long remembered by bereaved parents.7,32 Allowing families to speak and be heard at end-of-life conferences increases family satisfaction and reduces conflict with physicians.33,34 Careful listening may also help families during bereavement. Many parents wanted to provide feedback on positive aspects of care as well. For example, parents wanted to express gratitude to health professionals whom they perceived had gone beyond the call of duty in caring for their child.

The most frequent type of emotional support sought by parents was reassurance that the right decisions had been made and that no other plan of action would have altered the child's outcome. Research conducted after neonatal death has shown that parents welcome reassurance from a source they perceive as authoritative.28 Parents also wanted to know that the physician cared about them after the child's death. Although most parents did not rank physician inquiries about personal and family coping as very important, many parents explained that they would perceive such questions as a sign of caring. Parents did not expect the physician to provide grief counseling directly during the conference. Most parents ranked bereavement support as very important; however, several commented that referrals for such could be made by social workers or chaplains.

The physician-parent conference is not the only forum by which emotional support can be offered to parents. Many of the parents in this study received emotional support through contacts with nurses, chaplains, social workers and other hospital staff in the form of letters, telephone calls and personal visits. MacDonald et al9 described the deep appreciation felt by parents towards staff who attended memorial services, sent sympathy cards or performed other acts of kindness and commemoration after a child's death. Parents' perceptions of a caring emotional attitude from staff during the child's illness and death have been associated with a decreased intensity of parental grief both immediately after the death and in the long term.35

Limitations of this study include the large number of parents who could not be contacted and the predominance of mothers among participants. Differences in parents' views based on demographics, the trajectory of death or mode of death could not be evaluated due to the small sample size. Also, questions remain regarding whether parents would prefer to meet with a physician other than one who cared for their child in the PICU. Strengths of this study include the geographic diversity of the participants and the collection of data directly from bereaved parents.

Parents should be invited to attend a physician-parent conference early after their child's death and this invitation should be kept open for those parents who want to meet with the physician at a later time. Physicians should be prepared to provide information, receive feedback from parents about their PICU experience, and offer emotional support. More research is needed to evaluate the therapeutic effects of a physician-parent conference on parental grief.

Acknowledgments

Children's Hospital of Michigan, Detroit, MI: Sabrina Heidemann, MD, Maureen Frey, PhD, RN; Karmanos Cancer Institute, Detroit, MI: Terrance L. Albrecht, PhD; Children's National Medical Center, Washington DC: Michael Bell, MD, Jean Reardon, BSN, RN, Sandy Romero, CCLS; Arkansas Children's Hospital, Little Rock, AR: Parthak Prodhan, MD, Glenda Hefley, MNSc, RN; Seattle Children's Hospital, Seattle, WA: Thomas Brogan, MD, Ruth Barker, RRT; Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA: Shekhar T. Venkataraman, MD, Alan Abraham, BA; Children's Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA: Jeffrey I. Gold, PhD, Elizabeth Ferguson, RN, J. Francisco Fajardo, CLS (ASCP), RN, MD; Mattel Children's Hospital at University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA: Rick Harrison, MD; University of Utah (Data Coordinating Center), Salt Lake City, UT: Jeri Burr, BS, RNC, CCRC, Amy Donaldson, MS, Richard Holubkov, PhD, Devinder Singh, BS, Rene Enriquez, BS; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, MD: Tammara Jenkins, MSN RN

List of Abbreviations

- PICU

Pediatric Intensive Care Unit

- CPCCRN

Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network

Appendix

The following individuals are members of the Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network:

Kathleen L. Meert, MD, Children's Hospital of Michigan, Detroit, MI; Murray Pollack, MD, Children's National Medical Center, Washington DC; K. J. S. Anand, MBBS, DPhil, Arkansas Children's Hospital, Little Rock, AR; Jerry Zimmerman, MD, PhD, Seattle Children's Hospital, Seattle, WA; Joseph Carcillo, MD, Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA; Christopher J. L. Newth, MB, ChB, Children's Hospital Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA; Rick Harrison, MD, Mattel Children's Hospital at University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA; J. Michael Dean, MD, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT; Douglas F. Willson, MD, University of Virginia Children's Hospital, Charlottesville, VA; Carol Nicholson, MD, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, MD.

Footnotes

The study was funded by cooperative agreements from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the Department of Health and Human Services (U10HD050096, U10HD049981, U10HD500009, U10HD049945, U10HD049983, U10HD050012 and U01HD049934).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Kathleen L. Meert, Children's Hospital of Michigan.

Susan Eggly, Karmanos Cancer Institute.

Murray Pollack, Children's National Medical Center.

K. J. S. Anand, Arkansas Children's Hospital.

Jerry Zimmerman, Seattle Children's Hospital.

Joseph Carcillo, Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh.

Christopher J. L. Newth, Children's Hospital Los Angeles.

J. Michael Dean, University of Utah.

Douglas F. Willson, University of Virginia Children's Hospital.

Carol Nicholson, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

References

- 1.National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 54. Apr 19, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Field MJ, Behrman RE, editors. When children die: improving palliative and end-of-life care for children and their families. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, Weissfeld LA, Watson RS, Rickert T, et al. on behalf of the Robert Wood Foundation ICU End-of-Life Peer Group. Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: an epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med. 2004;320:638–43. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000114816.62331.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robinson WM. Special concerns for infants and children. In: Curtis JR, Rubenfeld GD, editors. Managing death in the intensive care unit The transition from cure to comfort. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 337–47. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meyer EC, Ritholz MD, Burns JP, Truog RD. Improving the quality of end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit: parents' priorities and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2006;117:649–57. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer EC, Burns JP, Griffith JL, Truog RD. Parental perspectives on end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:226–31. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200201000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Contro N, Larson J, Scofield S, Sourkes B, Cohen H. Family perspectives on the quality of pediatric palliative care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:14–19. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Contro N, Larson J, Scofield S, Sourkes B, Cohen H. Hospital staff and family perspectives regarding quality of pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1248–52. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-0857-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mac Donald ME, Liben S, Carnevale FA, Rennick JE, Wolf SL, Meloche D, et al. Parental perspectives on hospital staff members' acts of kindness and commemoration after a child's death. Pediatrics. 2005;116:884–90. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sahler OJZ, Frager G, Levetown M, Cohn FG, Lipson MA. Medical education about end-of-life care in the pediatric setting: principles, challenges, and opportunities. Pediatrics. 2000;105:575–84. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.3.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kolarik RC, Walker G, Arnold RM. Pediatric resident education in palliative care: a needs assessment. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1949–54. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Granger CE, George C, Shelly MP. The management of bereavement on intensive care units. Intensive Care Med. 1995;21:429–36. doi: 10.1007/BF01707412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Block SD, Sullivan AM. Attitudes about end-of-life care: a national cross sectional study. J Palliat Med. 1998;1:347–55. doi: 10.1089/jpm.1998.1.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Bioethics and Committee on Hospice Care. Palliative care for children. Pediatrics. 2000;106:351–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. Witholding or withdrawing life sustaining treatment in children: a framework for practice. 2. London: Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health; 2004. [cited 2006 Aug 25]. Available from: http://www.rcpch.ac.uk/publications/recent_publications/witholding.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Truog RD, Cist AFM, Brackett SE, Burns JP, Curley MAQ, Danis M, et al. Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care init: The Ethics Committee of the Society of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:2332–48. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200112000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Willson DF, Dean JM, Newth C, Pollack M, Anand KJS, Meert K, et al. Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network (CPCCRN) Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2006;7:301–7. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000227106.66902.4F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Institutes of Health. HIPAA privacy rule Information for researchers. [cited 2006 Aug 25]. Available from: http://www.privacyruleandresearch.nih.gov/pr_08.asp#83. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cook P, White DK, Ross-Russell RI. Bereavement support following sudden and unexpected death: guidelines for care. Arch Dis Child. 2002;87:36–9. doi: 10.1136/adc.87.1.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stroebe MS, Stroebe W, Hansson RO. Handbook of bereavement-theory, research and intervention. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jankovik M, Masera G, Uderzo C, Conter V, Adamoli L, Spinetta JJ. Meetings with parents after the death of their child from leukemia. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1989;6:155–60. doi: 10.3109/08880018909034281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newton RW, Bergin B, Knowles D. Parents interviewed after their child's death. Arch Dis Child. 1986;61:711–15. doi: 10.1136/adc.61.7.711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Segal S, Fletcher M, Meekison WG. Survey of bereaved parents. Can Med Assoc J. 1986;134:38–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vernon DD, Dean JM, Timmons OD, Banner W, Jr, Allen-Webb EM. Modes of death in the pediatric intensive care unit: withdrawal and limitation of intensive care. Crit Care Med. 1993;21:1798–1802. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199311000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Charmaz K. Grounded theory. Objectivist and constructivist methods. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of qualitative research. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc; 2000. pp. 509–35. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halcomb EJ, Davidson PM. Is verbatim transcription of interview data always necessary? Appl Nurs Res. 2006;19:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2005.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stack CG. Bereavement in paediatric intensive care [editorial] Paediatr Anaesth. 2003;13:651–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2003.01112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McHaffie HE, Laing IA, Lloyd DJ. Follow up care of bereaved parents after treatment withdrawal from newborns. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2001;84:F125–8. doi: 10.1136/fn.84.2.F125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cuthberetson SJ, Margetts MA, Streat SJ. Bereavement follow-up after critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:1196–201. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200004000-00047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen S, Gottlieb BH, Underwood LG. Social relationships and health. In: Cohen S, Underwood LG, Gottlieb BH, editors. Social support measurement and intervention: A guide for health and social scientists. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Truog RD, Meyer EC, Burns JP. Toward interventions to improve end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:S373–79. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000237043.70264.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meert KL, Thurston CS, Briller SH. The spiritual needs of parents at the time of their child's death in the pediatric intensive care unit and during bereavement: a qualitative study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:420–7. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000163679.87749.CA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McDonagh JR, Elliot TB, Engelberg RA, Treece PD, Shannon SE, Rubenfeld GD, et al. Family satisfaction with family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: Increased proportion of family speech is associated with increased satisfaction. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1484–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000127262.16690.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meyer EC. On speaking less and listening more during end-of-life family conferences. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1609–11. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000130818.22599.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meert KL, Thurston CS, Thomas R. Parental coping and bereavement outcome after the death of a child in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2001;2:324–28. doi: 10.1097/00130478-200110000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]