Abstract

We recently showed that cytoplasmic γ-actin (γcyto-actin) is dramatically elevated in striated muscle of dystrophin-deficient mdx mice. Here we demonstrate that γcyto-actin is markedly increased in golden retriever muscular dystrophy (GRMD), which better recapitulates the dystrophinopathy phenotype in humans. γcyto-Actin was also elevated in muscle from α-sarcoglycan null mice, but not in several other dystrophic animal models, including mice deficient in β-sarcoglycan, α-dystrobrevin, laminin-2, or α7 integrin. Muscle from mice lacking dystrophin and utrophin also expressed elevated γcyto-actin, which was not restored to normal by transgenic overexpression of α7 integrin. However, γcyto-actin was further elevated in skeletal muscle from GRMD animals treated with the glucocorticoid prednisone at doses shown to improve the dystrophic phenotype and muscle function. These data suggest that elevated γcyto-actin is part of a compensatory cytoskeletal remodeling program that may partially stabilize dystrophic muscle in some cases where the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex is compromised.

INTRODUCTION

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a severe, X-linked, progressive muscle disease affecting 1 in every 3,500 male births. Mutations in the 2.5 million base pair DMD gene typically result in loss of the protein dystrophin [1]. Dystrophin functions as part of a larger oligomeric protein complex named the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex (DGC), which includes the dystroglycan subcomplex, the sarcoglycan/sarcospan subcomplex, dystrobrevins and syntrophins [2,3]. The DGC spans the sarcolemma and links the actin cytoskeleton with the extracellular matrix of myofibers [2,3].

We demonstrated that the DGC is required for strong mechanical coupling of costameric actin filaments to the sarcolemma and confirmed that sarcolemmal actin is exclusively comprised of the γcyto-actin isoform [4]. Transgenic expression of the dystrophin homolog utrophin restored the stable association of costameric actin with the sarcolemma [5]. Most recently, we demonstrated that γcyto-actin protein levels were elevated 10-fold in striated muscle from the dystrophin-deficient mdx mouse [6]. We hypothesized that elevated γcyto-actin levels may contribute to a compensatory remodeling of the dystrophin-deficient costameric cytoskeleton [6]. While studies of mdx mice have greatly advanced our understanding of dystrophinopathies in humans, there are a number of important pathological differences between dystrophin-deficient humans and mice. Furthermore, mutations in genes encoding other DGC components or associated proteins have been implicated in clinically distinct forms of muscular dystrophy [2,3]. Finally, the complexity of the costameric protein network supports the hypothesis that additional proteins may form distinct mechanical linkages parallel to the DGC γcyto-actin axis. Therefore, it is of interest to determine whether the increased γcyto-actin measured in mdx muscle [6] manifests in other animal models of dystrophy or is unique to the mdx mouse.

Here, we report that γcyto-actin was also dramatically increased in the GRMD canine model of DMD and in a mouse model of limb girdle muscular dystrophy 2D, but not in six additional mouse lines relevant to DGC function. Moreover, daily treatment of GRMD dogs with 2 mg/kg prednisone was previously shown to improve muscle function and overall phenotype [7] and is reported here to result in a further increase in γcyto-actin protein levels. We suggest that increased levels of γcyto-actin may participate in remodeling the costamere to partially reinforce the mechanically weakened dystrophin-deficient sarcolemma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

C57BL/6J (6 or 16 weeks old), C57BL/10ScSn-DMDmdx/J (16 weeks old), and C57BL/6J-Lama2dy mice (6 weeks old) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice deficient for α-sarcoglycan, β-sarcoglycan, α-dystrobrevin or α7 integrin were described previously [8–11] and were analyzed at 14–16 weeks of age. Transgenic mice overexpressing α7 integrin [12] were bred onto mdx, and mdx/utrophin −/− double knockout (mdx/utrn−/−) backgrounds and analyzed at 6 weeks of age. Muscle biopsies from control and GRMD dogs were described previously [7]. Where indicated, control and GRMD dogs were treated daily with 2 mg/kg from either 1 week to 6 months or 1 week to 2 months of age.

Antibodies

Affinity purified polyclonal antibodies and monoclonal antibodies to γcyto-actin were previously characterized [6]. Antibodies to sarcomeric α-actin were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Peroxidase-labeled secondary antibodies against rabbit and mouse immunoglobulins were from Chemicon International, Inc. (Temecula, Ca) and Roche (Indianapolis, IN), respectively.

Muscle extracts and DNaseI chromatography

Frozen skeletal muscle was pulverized in a liquid nitrogen-cooled mortar and pestle, extracted in Tris-buffered saline and enriched for soluble monomeric actin by DNaseI affinity chromatography as described [6].

SDS-PAGE and western blot analysis

SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transfer to nitrocellulose and western blotting were performed as described [6].

Quantitative western blot analysis

γcyto-Actin immunoreactivity was detected from western blots by autoradiography using 125I -labeled goat anti-mouse IgG as secondary (PerkinElmer, Boston, MA) and quantified densitometrically as previously described [6]. Statistical comparisons between groups were performed by ANOVA followed by a non-paired Tukey post hoc test to determine significance and data are reported as the mean ± SD.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

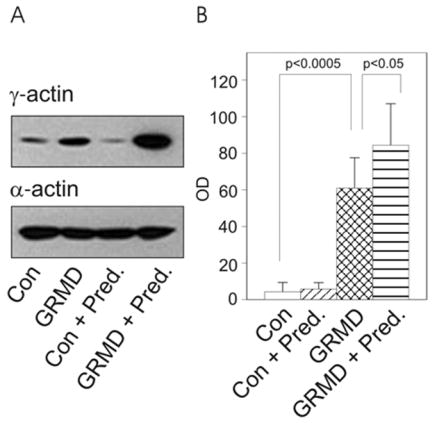

To determine whether γcyto-actin is dramatically elevated in other dystrophin-deficient animals besides the mdx mouse, DNaseI-enriched muscle extracts from control and GRMD dogs were compared for γcyto-actin immunoreactivity by western blot analysis (Fig. 1A). In blind trials, all GRMD specimens were distinguished from controls based on increased γcyto-actin immunoreactivity (Fig. 1A). Quantitative western blot analysis (Fig. 1B) reported a 15-fold elevation in γcyto-actin levels of GRMD muscle, which was significantly different from control canine muscle.

Figure 1. γcyto-Actin levels in dystrophin-deficient GRMD skeletal muscle.

(A) Western blots loaded with DNaseI –enriched muscle extracts from untreated control (Con), GRMD, and prednisone-treated control or GRMD animals were stained for γcyto-actin and α-actin. (B) Quantitation of γ-actin immunoreactivity (OD, arbitrary units) in DNaseI eluates from muscle in control (n = 4), GRMD (n=7), prednisone-treated control (n=4), and prednisone-treated GRMD animals (n=6). γcyto-Actin was significantly elevated in GRMD muscle compared to control (p<0.0005) and in muscle from prednisone-treated GRMD compared to untreated GRMD animals (p<0.05).

Treatment of both human DMD patients and GRMD dogs with the glucocorticoid prednisone has been shown to slow disease progression and produce short-term functional improvements in dystrophic muscle [7,13–15]. To determine if prednisone treatment affected the levels of γcyto-actin in skeletal muscle from dystrophin-deficient dogs, four controls and four GRMD dogs were administered daily treatment with 2 mg/kg prednisone from one week to six months of age. Two additional GRMD dogs were treated with 2 mg/kg prednisone from one week to two months of age. While prednisone did not affect γcyto-actin levels in control skeletal muscle, γcyto-actin levels in prednisone-treated GRMD dogs were significantly increased compared to untreated GRMD dogs (Figs. 1A and B). There was no difference in cytoplasmic γcyto-actin levels between the GRMD dogs treated with prednisone for two or six months. The pooled data indicate that γcyto-actin protein levels in skeletal muscle from prednisone-treated GRMD dogs were increased 20-fold over skeletal muscle from control dogs (Fig. 1B).

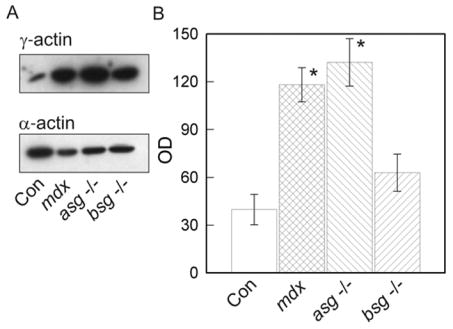

γcyto-Actin levels were also evaluated in seven additional mouse models of dystrophy relevant to DGC function. α- and β-sarcoglycans are integral subunits of the sarcoglycan-sarcospan complex that are thought to stabilize the interactions of β-dystroglycan with dystrophin and α-dystroglycan [16]. Mutations in α- and β-sarcoglycan cause forms of limb-girdle muscular dystrophy in humans and progressive muscular dystrophy when knocked out in mice [16]. Surprisingly, quantitative western blot analysis reported significantly elevated γcyto-actin levels in DNaseI-enriched muscle extracts from α-sarcoglycan null mice but not from β-sarcoglycan null animals (Fig. 2). While the molecular basis for this difference is presently unclear, both human patients and mouse models ablated for different sarcoglycan subunits present with distinct molecular, cellular and/or tissue phenotypes [9,16,17]. Consistent with the improved phenotype and significantly elevated γ-actin in prednisone-treated GRMD muscle compared to untreated GRMD muscle (Fig. 1), the greater elevation of γ-actin levels in α-sarcoglycan null muscle correlated with their less severe phenotype as compared to β-sarcoglycan deficient animals [9].

Figure 2. γcyto-Actin levels in α- and β-sarcoglycan null muscle.

(A) Western blots loaded with DNaseI-enriched muscle extracts from 14–16 week-old control, dystrophin-deficient mdx, α-sarcoglycan deficient (asg−/−) and β-sarcoglycan deficient (bsg−/−) mice stained for γ- and α-actin. (B) Quantitation of γcyto-actin immunoreactivity (OD, arbitrary units) in control (n=3), mdx (n=3), asg −/− (n=4) and bsg −/− (n=4) muscle where the asterisks indicate a significant difference from control (p <0.0005).

α-Dystrobrevin is a cytoplasmic DGC component that binds dystrophin and the sarcoglycan complex. Ablation of α-dystrobrevin in mice results in a progressive myopathy with increased fiber necrosis and regeneration but without the compromised sarcolemmal integrity observed in dystrophin-deficient muscle [10]. Quantitative western blot analysis revealed no difference in γcyto-actin levels of DNaseI-enriched muscle extracts from control and α-dystrobrevin null mice (Fig. 3). Two-hybrid screens have identified synemin [18] and syncoilin [19,20] as α-dystrobrevin binding proteins. Both are structurally related to intermediate filament proteins and interact with the muscle-specific intermediate filament protein desmin [18–20]. Synemin also directly binds to α-actinin [21] and vinculin [22] to provide additional mechanical linkages between the DGC and muscle cytoskeleton. Thus, it appears that mechanical coupling of the DGC to the intermediate filament cytoskeleton is specifically disrupted in α-dystrobrevin null muscle without effect on the dystrophin/γcyto-actin linkage.

Figure 3. γcyto-Actin levels in α-dystrobrevin null muscle.

(A) Western blots loaded with DNaseI-enriched muscle extracts from 14–16 week-old dystrophin-deficient mdx, control, and α-dystrobrevin deficient (adbn−/−) mice stained for γ- and α-actin. (B) Quantitation of γcyto-actin immunoreactivity (OD, arbitrary units) in mdx (n=3), control (n=3), and adbn −/− (n=3) muscle where the asterisk indicates significance between mdx and the other groups (p <0.0000005).

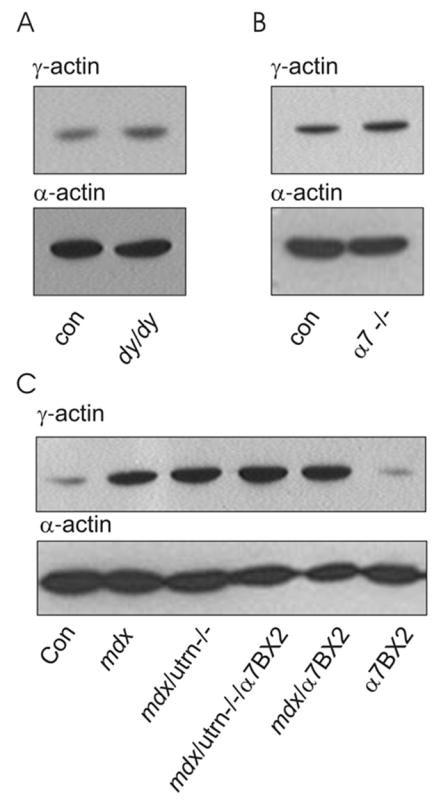

The dystrophic dy/dy mouse is deficient in laminin-2 [23], but shows normal sarcolemmal expression of the DGC [24], retention of costameric actin on peeled sarcolemma [4], and little evidence of sarcolemma disruption prevalent in mdx muscle [25]. While dy/dy mice exhibit substantial muscle cell necrosis and regeneration [26], we observed similar γcyto-actin levels in skeletal muscle from control and dystrophic dy/dy mice (Fig. 4A). Recent studies [27–29] indicate that the DGC and the laminin-binding α7β1 integrin perform overlapping functions in skeletal muscle. However, western blot analysis demonstrated that γcyto-actin was not altered in dystrophic α7 integrin null muscle compared to control (Fig. 4B). Finally, mice deficient in both dystrophin and utrophin (mdx/utrn −/−) present with a more severe DMD-like phenotype [30,31], which is partially rescued by transgenic overexpression of α7 integrin [12]. Therefore, we examined how the combined absence of dystrophin and utrophin as well as α7 integrin overexpression affected γcyto-actin protein levels. γcyto-Actin immunoreactivity was similarly increased in mdx and mdx/utrn −/− muscle compared to control regardless of the level of α7β1 integrin expression (Fig. 4C). Taken together, the results of Figs 2–4 indicate that elevated γcyto-actin is neither unique to dystrophin deficiency, nor is it a feature common to all forms of skeletal myopathy including those directly involving the DGC.

Figure 4. γcyto-Actin levels in other dystrophic animal models.

(A) α- and γcyto-actin in DNaseI-enriched muscle extracts of 6 week-old control (Con) and laminin-2 deficient dy/dy mice. (B) α- and γcyto-actin in DNaseI-enriched muscle extracts of 14–16 week-old control (Con) and α7 integrin deficient (α7 −/−) mice. (C), α- and γcyto-actin in DNaseI-enriched muscle extracts of 6 week-old control, mdx, mdx/utrn −/−, and mice overexpressing α7 integrin (α7BX2) on mdx, mdx/utr−/− and control backgrounds.

The actin binding proteins γ-filamin, talin, vinculin, plectin and utrophin are all upregulated and/or redistributed to costameres in dystrophin-deficient muscle [4,5,32–34]. With the exception of utrophin, all of these proteins interact with integrins in vivo and α7β1 integrin is also upregulated in dystrophin-deficient muscle [35,36]. Therefore, we previously suggested that γcyto-actin levels may be elevated in dystrophin-deficient muscle as part of a compensatory remodeling program to fortify the weakened sarcolemmal cytoskeleton through recruitment of parallel mechanical linkages [6]. Because dystrophy persists, these parallel linkages are either not completely redundant with the DGC, or the compensatory upregulation/recruitment is not maximal. In support of the latter possibility, transgenic overexpression of α7 integrin has been shown to partially compensate for the combined deficiency of dystrophin and utrophin [12]. In support of the former possibility, we have shown that γcyto-actin protein levels were not altered in mice deficient in α7 integrin or in animals overexpressing α7 integrin on wild type, mdx or mdx/utrn −/− double knockout backgrounds. We conclude that endogenous upregulation of γcyto-actin and α7 integrin are two factors that may limit the effectiveness of compensatory cytoskeletal remodeling in the dystrophin-deficient mdx mouse.

As shown for mdx mice [6], γcyto-actin was significantly elevated in skeletal muscle of the GRMD model of dystrophin-deficiency. Utrophin is upregulated in both animals [37–40] suggesting that a similar compensatory remodeling program is activated in dystrophin-deficient mice and dogs. However, GRMD dogs suffer a severe and rapidly progressing muscle disease with premature lethality more closely resembling DMD in humans while mdx mice exhibit a milder phenotype with no dramatic reduction in lifespan [3]. Thus, it appears that compensatory cytoskeletal remodeling is not as effective in dystrophin-deficient dogs compared to mice, which may be due to the greater mechanical stresses imposed on the sarcolemma of larger animals with correspondingly larger myofibers [30,41]. More interestingly, we demonstrated that daily treatment with prednisone correlated with a significant elevation in γcyto-actin levels in GRMD skeletal muscle as compared to muscle from non-treated GRMD dogs. These prednisone dosages were previously shown to improve dystrophic histopathology in GRMD dogs and increased isometric extensor forces towards normal [7]. Prednisone treatment also resulted in decreased fetal myosin heavy chain expression indicating reduced regeneration in treated versus non-treated GRMD dogs [7]. Our current results suggest that pharmacologically-induced upregulation of γcyto-actin correlates with improvement of the dystrophin-deficient phenotype. Furthermore, studies investigating the mechanism by which prednisone increases γcyto-actin in dystrophin-deficient skeletal muscle may have clinical relevance.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Mark Grady for α-dystrobrevin null mice, Kevin P. Campbell for α- and β-sarcoglycan null mice, and Kevin Sonnemann and Michele Jaeger for their critiques. Supported by grants from the MDA (J.M.E. and S.J.K.) and NIH (AR049899 and AR042423 to J.M.E., AG014632 to S.J.K.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.O’Brien KF, Kunkel LM. Dystrophin and muscular dystrophy: past, present, and future. Mol Genet Metab. 2001;74:75–88. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2001.3220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohn RD, Campbell KP. Molecular basis of muscular dystrophies. Muscle Nerve. 2000;23:1456–1471. doi: 10.1002/1097-4598(200010)23:10<1456::aid-mus2>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blake DJ, Weir A, Newey SE, Davies KE. Function and genetics of dystrophin and dystrophin-related proteins in muscle. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:291–329. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rybakova IN, Patel JR, Ervasti JM. The dystrophin complex forms a mechanically strong link between the sarcolemma and costameric actin. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:1209–1214. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.5.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rybakova IN, Patel JR, Davies KE, Yurchenco PD, Ervasti JM. Utrophin binds laterally along actin filaments and can couple costameric actin with the sarcolemma when overexpressed in dystrophin-deficient muscle. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:1512–1521. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-09-0446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanft LM, Rybakova IN, Patel JR, Rafael-Fortney JA, Ervasti JM. Cytoplasmic γ-actin contributes to a compensatory remodeling response in dystrophin-deficient muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5385–5390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600980103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu JM, Okamura CS, Bogan DJ, Bogan JR, Childers MK, Kornegay JN. Effects of prednisone in canine muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve. 2004;30:767–773. doi: 10.1002/mus.20154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duclos F, Straub V, Moore SA, Venzke DP, Hrstka RF, Crosbie RH, Durbeej M, Lebakken CS, Ettinger AJ, Van der Meulen J, Holt KH, Lim LE, Sanes JR, Davidson BL, Faulkner JA, Williamson R, Campbell KP. Progressive muscular dystrophy in α-sarcoglycan-deficient mice. J Cell Biol. 1998;142:1461–1471. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.6.1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Durbeej M, Cohn RD, Hrstka RF, Moore SA, Allamand V, Davidson BL, Williamson RA, Campbell KP. Disruption of the β-sarcoglycan gene reveals pathogenetic complexity of limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 2E. Mol Cell. 2000;5:141–151. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80410-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grady RM, Grange RW, Lau KS, Maimone MM, Nichol MC, Stull JT, Sanes JR. Role for α-dystrobrevin in the pathogenesis of dystrophin-dependent muscular dystrophies. Nature Cell Biol. 1999;1:215–220. doi: 10.1038/12034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayer U, Saher G, Fässler R, Bornemann A, Echtermeyer F, von der Mark H, Miosge N, Pöschl E, von der Mark K. Absence of integrin α7 causes a novel form of muscular dystrophy. Nature Genetics. 1997;17:318–323. doi: 10.1038/ng1197-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burkin DJ, Wallace GQ, Nicol KJ, Kaufman DJ, Kaufman SJ. Enhanced expression of the alpha 7 beta 1 integrin reduces muscular dystrophy and restores viability in dystrophic mice. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:1207–1218. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.6.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonifati MD, Ruzza G, Bonometto P, Berardinelli A, Gorni K, Orcesi S, Lanzi G, Angelini C. A multicenter, double-blind, randomized trial of deflazacort versus prednisone in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve. 2000;23:1344–1347. doi: 10.1002/1097-4598(200009)23:9<1344::aid-mus4>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carter GT, McDonald CM. Preserving function in Duchenne dystrophy with long-term pulse prednisone therapy. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;79:455–458. doi: 10.1097/00002060-200009000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong BL, Christopher C. Corticosteroids in Duchenne muscular dystrophy: a reappraisal. J Child Neurol. 2002;17:183–190. doi: 10.1177/088307380201700306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ozawa E, Mizuno Y, Hagiwara Y, Sasaoka T, Yoshida M. Molecular and cell biology of the sarcoglycan complex. Muscle Nerve. 2005;32:563–576. doi: 10.1002/mus.20349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hack AA, Lam MY, Cordier L, Shoturma DI, Ly CT, Hadhazy MA, Hadhazy MR, Sweeney HL, McNally EM. Differential requirement for individual sarcoglycans and dystrophin in the assembly and function of the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex. J Cell Sci. 2000;113 ( Pt 14):2535–2544. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.14.2535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mizuno Y, Thompson TG, Guyon JR, Lidov HG, Brosius M, Imamura M, Ozawa E, Watkins SC, Kunkel LM. Desmuslin, an intermediate filament protein that interacts with alpha - dystrobrevin and desmin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6156–6161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111153298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newey SE, Howman EV, Ponting CP, Benson MA, Nawrotzki R, Loh NY, Davies KE, Blake DJ. Syncoilin, a novel member of the intermediate filament superfamily that interacts with alpha-dystrobrevin in skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:6645–6655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008305200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poon E, Howman EV, Newey SE, Davies KE. Association of syncoilin and desmin: linking intermediate filament proteins to the dystrophin-associated protein complex. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3433–3439. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105273200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bellin RM, Sernett SW, Becker B, Ip W, Huiatt TW, Robson RM. Molecular characteristics and interactions of the intermediate filament protein synemin. Interactions with alpha-actinin may anchor synemin- containing heterofilaments. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:29493–29499. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.41.29493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bellin RM, Huiatt TW, Critchley DR, Robson RM. Synemin may function to directly link muscle cell intermediate filaments to both myofibrillar Z-lines and costameres. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:32330–32337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sunada Y, Bernier SM, Kozak CA, Yamada Y, Campbell KP. Deficiency of merosin in dystrophic dy mice and genetic linkage of laminin M chain gene to dy locus. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:13729–13732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohlendieck K, Campbell KP. Dystrophin-associated proteins are greatly reduced in skeletal muscle from mdx mice. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:1685–1694. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.6.1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Straub V, Rafael JA, Chamberlain JS, Campbell KP. Animal models for muscular dystrophy show different patterns of sarcolemmal disruption. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:375–385. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.2.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jin Y, Murakami N, Saito Y, Goto Y, Koishi K, Nonaka I. Expression of MyoD and myogenin in dystrophic mice, mdx and dy, during regeneration. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 2000;99:619–627. doi: 10.1007/s004010051172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Allikian MJ, Hack AA, Mewborn S, Mayer U, McNally EM. Genetic compensation for sarcoglycan loss by integrin α7β1 in muscle. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:3821–3830. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo C, Willem M, Werner A, Raivich G, Emerson M, Neyses L, Mayer U. Absence of α7 integrin in dystrophin-deficient mice causes a myopathy similar to Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:989–998. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rooney JE, Welser JV, Dechert MA, Flintoff-Dye NL, Kaufman SJ, Burkin DJ. Severe muscular dystrophy in mice that lack dystrophin and α7 integrin. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:2185–2195. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grady RM, Teng HB, Nichol MC, Cunningham JC, Wilkinson RS, Sanes JR. Skeletal and cardiac myopathies in mice lacking utrophin and dystrophin: A model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell. 1997;90:729–738. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80533-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deconinck AE, Rafael JA, Skinner JA, Brown SC, Potter AC, Metzinger L, Watt DJ, Dickson JG, Tinsley JM, Davies KE. Utrophin-dystrophin-deficient mice as a model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell. 1997;90:717–727. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80532-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson TG, Chan YM, Hack AA, Brosius M, Rajala M, Lidov HG, McNally EM, Watkins S, Kunkel LM. Filamin 2 (FLN2): A muscle-specific sarcoglycan interacting protein. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:115–126. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.1.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schroder R, Mundegar RR, Treusch M, Schlegel U, Blumcke I, Owaribe K, Magin TM. Altered distribution of plectin/HD1 in dystrophinopathies. Eur J Cell Biol. 1997;74:165–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Law DJ, Allen DL, Tidball JG. Talin, vinculin and DRP (utrophin) concentrations are increased at mdx myotendinous junctions following onset of necrosis. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:1477–1483. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.6.1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vachon PH, Xu H, Liu L, Loechel F, Hayashi Y, Arahata K, Reed JC, Wewer UM, Engvall E. Integrins (α7β1) in muscle function and survival - Disrupted expression in merosin-deficient congenital muscular dystrophy. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:1870–1881. doi: 10.1172/JCI119716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hodges BL, Hayashi YK, Nonaka I, Wang W, Arahata K, Kaufman SJ. Altered expression of the α7β1 integrin in human and murine muscular dystrophies. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:2873–2881. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.22.2873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matsumura K, Ervasti JM, Ohlendieck K, Kahl SD, Campbell KP. Association of dystrophin-related protein with dystrophin-associated proteins in mdx mouse muscle. Nature. 1992;360:588–591. doi: 10.1038/360588a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Porter JD, Rafael JA, Ragusa RJ, Brueckner JK, Trickett JI, Davies KE. The sparing of extraocular muscle in dystrophinopathy is lost in mice lacking utrophin and dystrophin. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:1801–1811. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.13.1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilson LA, Cooper BJ, Dux L, Dubowitz V, Sewry CA. Expression of utrophin (dystrophin-related protein) during regeneration and maturation of skeletal muscle in canine X-linked muscular dystrophy. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1994;20:359–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1994.tb00981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schatzberg SJ, Olby NJ, Breen M, Anderson LVB, Langford CF, Dickens HF, Wilton SD, Zeiss CJ, Binns MM, Kornegay JN, Morris GE, Sharp NJH. Molecular analysis of a spontaneous dystrophin ‘knockout’ dog. Neuromusc Disord. 1999;9:289–295. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(99)00011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petrof BJ, Shrager JB, Stedman HH, Kelly AM, Sweeney HL. Dystrophin protects the sarcolemma from stresses developed during muscle contraction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3710–3714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]