Abstract

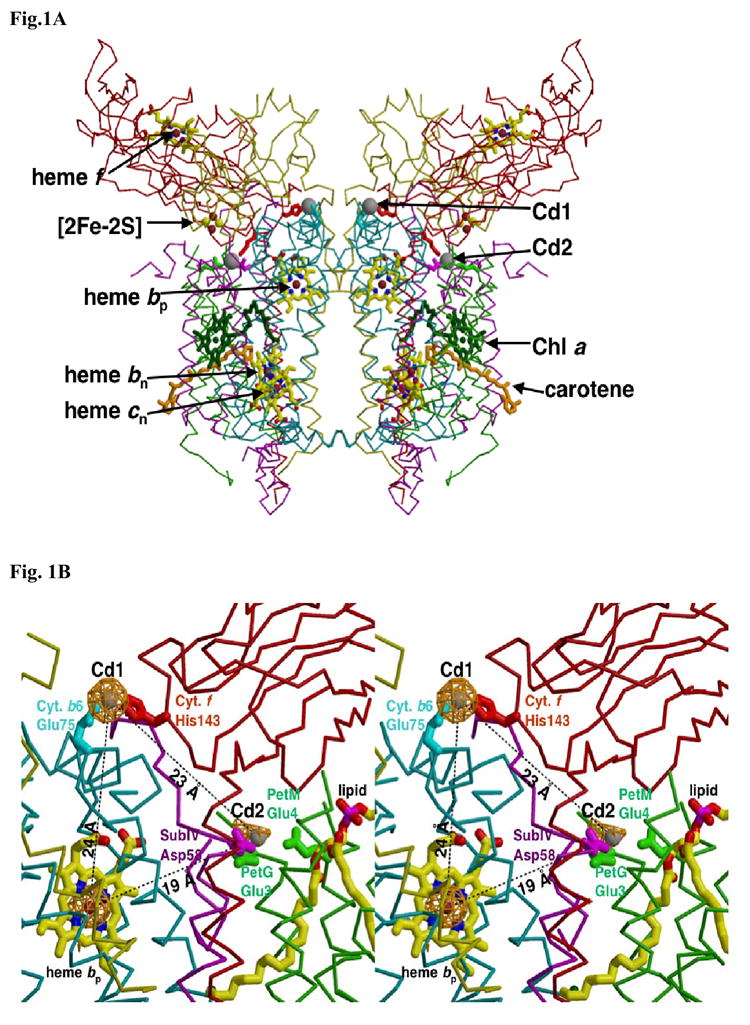

A native structure of the cytochrome b6f complex with improved resolution was obtained from crystals of the complex grown in the presence of divalent cadmium. Two Cd2+ binding sites with different occupancy were determined: (i) a higher affinity site, Cd1, which bridges His143 of cytochrome f and the acidic residue, Glu75, of cyt b6; in addition, Cd1 is coordinated by 1-2 H2O or 1-2 Cl- ; (ii) a second site, Cd2, of lower affinity for which three identified ligands are Asp58 (subunit IV), Glu3 (PetG subunit) and Glu4 (PetM subunit).

Binding sites of quinone analogue inhibitors were sought in order to map the pathway of transfer of the lipophilic quinone across the b6f complex and to further define the function of the novel heme cn. Two sites were found for the chromone ring of the tridecyl-stigmatellin (TDS) quinone analogue inhibitor, one near the p-side [2Fe-2S] cluster. A second TDS site was unexpectedly found on the n-side of the complex facing the quinone exchange cavity as an axial ligand of heme cn. A similar binding site proximal to heme cn was found for the n-side quinone analogue inhibitor, NQNO. Binding of these inhibitors required their addition to the complex before lipid that is used to facilitate crystallization.

The similar binding of NQNO and TDS as axial ligands to heme cn implies that this heme utilizes plastoquinone as a natural ligand, thus defining an electron transfer complex consisting of hemes bn, cn, and PQ, and the pathway of n-side reduction of the PQ pool. The NQNO binding site provides an explanation for several effects associated with its inhibitory action: the large negative shift in midpoint redox potential of heme cn, the increased amplitude of light-induced reduction of heme bn, and an altered EPR spectrum attributed to interaction between hemes cn and bn. A decreased extent of heme cn reduction by reduced ferredoxin in the presence of NQNO allows observation of the heme cn Soret band in a chemical difference spectrum.

Keywords: crystal structure, cytochrome b6f, cyclic electron transfer, heme cn, plastoquinone, quinone analogue inhibitors

Introduction

The hetero-oligomeric dimeric cytochrome b6f complex mediates electron transfer between the photosystem II and photosystem I reaction center complexes in oxygenic photosynthesis by oxidizing the relatively low potential (Em7 ≈ + 0.1V) lipophilic plastoquinol and reducing soluble plastocyanin or cytochrome c6, as discussed in several reviews with different perspectives 1-7. These electron transfer events are linked to proton translocation across the low dielectric membrane that generates a proton electrochemical potential gradient of approximately 250 mV, positive on the p- or lumen side of the membrane. A detailed understanding of charge transfer and movement of lipophilic quinone across the membrane in the b6f complex requires information derived from structure analysis. Three-dimensional structures of the b6f complex obtained from x-ray diffraction have been obtained at a resolution of 3.0 - 3.1 Å from the thermophilic filamentous cyanobacterium, Mastigocladus laminosus (pdb accession, 1VF5) 8, and the green alga, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (pdb, 1Q90) 9 in the presence of the quinone analogue inhibitor, tri-decyl-stigmatellin. Structures of the native complex, and the complex with the inhibitor DBMIB (pdb, 2D2C) bound tightly at a site very distal to the [2Fe-2S] cluster, have also been obtained from M. laminosus 8; 10. These structures show that the b6f complex contains eight polypeptide subunits with 13 trans-membrane helices in each monomer of a functional dimer5-9; 11; 12. Four of the eight subunits, petA, B, C, D, that contain or confine the redox prosthetic groups are “large” (16 – 31 kDa: cytochrome f, cytochrome b6, the Rieske iron-sulfur protein, and subunit IV; the four small (3.3 - 4.1 kDa) hydrophobic subunits, petG, L, M, and N form a “fence” at the outside periphery of each monomer, with each small subunit containing one trans-membrane helix. The b6f complex isolated from plant (spinach) thylakoid membranes contains one additional subunit, FNR 13; 14 that is bound more weakly to the spinach complex, and is not present in the cyanobacterial b6f complex.

Given the similarity found between the core of the cytochrome bc1 complex from the mitochondrial respiratory chain and photosynthetic bacteria and that of the b6f complex 15, structure information derived from the bc1 complex16-26 is relevant to an understanding of structure-function of the b6f complex.

Unique prosthetic groups; heme cn. The b6f complex from both the cyanobacterial and green algal sources shows the presence of three unusual or unique prosthetic groups, each present at a unit stoichiometry, chlorophyll a 27-29 and β-carotene 29, shown previously by biochemical analysis, whose presence would not have been expected a priori in the b6f complex that functions in the ‘dark’ reactions of oxygenic photosynthesis. In the structure studies, a unique covalently bound heme, heme cn, was found on the electrochemically negative side of the complex. Heme cn has no amino acid side chain serving as an axial ligand, but only an axial H2O that bridges the 4 Å distance between the Fe atom of heme cn and a propionate oxygen of heme bn 8; 9. In retrospect, it was realized that heme cn was previously defined spectrophotometrically and designated as component ‘G.’30; 31. The position of heme cn in close proximity to the previously well-defined heme bn that has been proposed to function in a ‘Q cycle’ 32-40 and alternatively, or as well, in a ferredoxin-linked cyclic pathway 7-9, begs the question of the location of the plastoquinone that should provide the electron acceptor in these pathways.

Together with atomic structures of the PSI 41 and PSII 42-45 reaction center complexes, also obtained from a thermophilic cyanobacterium, a structure framework has been completed of the three integral membrane protein complexes that sustain linear electron transport in oxygenic photosynthesis. These structures have provided deeper insight into the pathways and mechanisms that govern redox energy transduction and, as well, trans-membrane movement of hydrophobic plastoquinone(ol) in the photosynthetic membrane.

The present study focuses on the binding site(s) of the quinone analogue inhibitors, TDS and NQNO, in the M. laminosus b6f complex, which lead to the inference that plastoquinone is an axial ligand of heme cn, and the question of conformational changes transmitted across the complex by NQNO. The question of whether trans-membrane conformational changes are transmitted across the b6f complex is of interest not only for a detailed understanding of the structure-function of cytochrome bc complexes, but also for the mechanism of trans-membrane transmission of signals arising from receptor activation by various stimuli ranging from light to hormones, which must involve conformational changes of trans-membrane α-helices 46.

Results

1. The native b6f complex with cadmium

Crystallization of the native b6f complex in the presence of divalent Cd ions, Cd2+, resulted in an improvement of the native structure from 3.4 Å (Rcryst = 0.256; Rfree = 0.336)9 to 3.00 Å (Rcryst = 0.222 and Rfree = 0.268; Table I). These parameters were obtained from refinement using space group P6122 instead of P61, based on the assumption that the asymmetric unit contains the monomeric unit of the complex, and that the resulting structure of the b6f complex is described by a symmetric dimer.

Table 1.

Intensity data and refinement statistics

| Data set | Native | TDS | NQNO |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||

| X-ray source | APS SBC-19ID | APS SBC-19ID | APS SBC-19ID |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.97934 | 0.97856 | 0.97934 |

| Resolution (Å) | 3.00 (3.11-3.00) | 3.40 (3.52-3.40) | 3.55 (3.68-3.55) |

| Measured reflections | 227,206 (22,810) | 262,461 (26,251) | 304,131 (30,616) |

| Unique reflections | 54,088 (5,305) | 37,057 (3,596) | 33,633 (3,292) |

| Redundancy | 4.2 (4.3) | 7.1 (7.3) | 9.0 (9.3) |

| I/σ(I) | 21.5 (2.7) | 24.5 (5.4) | 24.9 (6.2) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.7 (100.0) | 99.8 (100.0) | 99.5 (100.0) |

| Rmerge (%) | 7.3 (42.9) | 11.7 (37.4) | 8.6 (37.6) |

| Refinement | |||

| Rcryst | 0.222 | 0.201 | 0.224 |

| Rfree | 0.268 | 0.258 | 0.273 |

| rms deviation from ideal | |||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.014 | 0.013 | 0.013 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.89 | 1.91 | 2.00 |

| Average B factors (Å2) | 66.5 | 55.1 | 75.9 |

| Luzzati coordinate error (Å) | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.64 |

Values in parentheses apply to the highest resolution shell.

In the native structure, obtained from crystallization in the presence of the divalent cation, Cd2+, two Cd2+ binding sites are located in each monomer (Figs. 1A, B), a relatively high affinity (Cd1) and low (Cd2) site. Cd1, close to the p-side of the complex and the inter-monomer interface (Fig. 1A), is coordinated by His143 of cytochrome f and Glu75 of cytochrome b6 (Fig. 1B), and is also coordinated by 1-2 H2O or 1-2 Cl- (not shown). The second lower affinity Cd2+ binding site, located at the p-side aqueous interface of the complex near the small subunits of the complex and the external lipid medium, is coordinated by a carboxylate residue of subunit IV (Asp58) and carboxylate residues Glu3 and Glu4 of the small subunits. From effects of Cu2+ and Zn2+ on the EPR spectra of the Rieske [2Fe-2S] cluster in the spinach b6f complex47; 48, His143 was inferred to participate in one of three binding sites for divalent Cu2+ or Zn2+ ions.

Fig. 1. Two cadmium (Cd2+) binding sites on the p-side of the M. laminosus b6f complex.

(A) Position of higher occupancy (Cd1) is close to the inter-monomer interface, and that of lower occupancy (Cd2) site is near the small subunits and the exterior of the complex. View is parallel to the plane of the membrane. Distances: (i) from Cd1 site, and (ii) from Cd2, to the [2Fe-2S] cluster on the same and opposite side monomer, (i) 38.9 Å and 40.1 Å, and (ii) 57.1 and 28.0 Å. Color code: cytochrome b6 (cyan), subunit IV (purple), cytochrome f (red), ISP (yellow), PetG, PetL, PetM, and PetN (green). (B, stereo) Environment of Cd1 and Cd2 sites shown in more detail. Lower occupancy of the Cd2 site is shown by the smaller cage of electron density. A lipid molecule (possibly galactolipid) described in the coordinates of the C. reinhardtii b6f complex (pdb; 1Q90), but not previously discussed, is closer to Cd2. Distances: higher (Cd1) to lower occupancy (Cd2) Cd2+ site, 23.2 Å; higher occupancy Cd1 site to heme bp, 24.0 Å; Cd2 to residues Glu78, Trp79 and Y80 of the ‘PEWY’ loop on the same monomer, 13, 12, and 16 Å. The seven peaks of largest amplitude in the anomalous difference map are: Cd1 site (18.5 σ), heme bp (18.1 σ), heme cn (17.6 σ), heme bn (17.0 σ), heme f (13.3 σ), [2Fe-2S] site (11.1 σ), Cd2 site (6.3 σ). The anomalous scattering factors (f″) for Fe and Cd at 0.98 A are 1.50 and 2.13, respectively. The B factors of the Cd1 and Cd2 sites are 80 Å2 and 178 Å2.

The amplitudes of the anomalous scattering by the Cd sites and those of the other metal centers, in order of peak height relative to the background and scattering from other metal sites, are summarized in the legend of Fig. 1B.

The distances from the Cd1 and Cd2 sites are: Cd1 to Cd2, 23.2 Å; from Cd1 to heme bp, 24.0 Å, and to the [2Fe-2S] cluster on the same and opposite side monomer, 38.9 Å and 40.1 Å (average distances to the 4 atoms of the cluster). From Cd2, the distances to the [2Fe-2S] cluster on the same and opposite side monomer are 57.1 and 28.0 Å. Thus, inhibitory effects of Cd2+ are not related to any direct effect on PQ binding to the [2Fe-2S] cluster. Furthermore, occlusion of a p-side H+ transfer pathway seems unlikely because the shortest distances from a Cd2+ binding site to the PEWY sequence that is implicated in p-side H+ transfer are 13, 12, and 16 Å to Glu78, Trp79, and Tyr80. Conformation changes that are allosteric in nature caused by Cu2+ binding to the b6f complex, which could be responsible for inhibition of electron transport, have been reported 47; 48. The existence of the small changes in conformation, a change in orientation (ca. 5°) of the cytochrome f heme relative to the plane of the membrane, and a 7° rotation of the [2Fe-2S] cluster and the soluble domain of the iron-sulfur protein around the S-S axis of the cluster, calculated from the effects of Cu2+ and Zn2+ on the EPR spectra 48, cannot be determined at the present resolution of the structure of the b6f - Cd2+ complex.

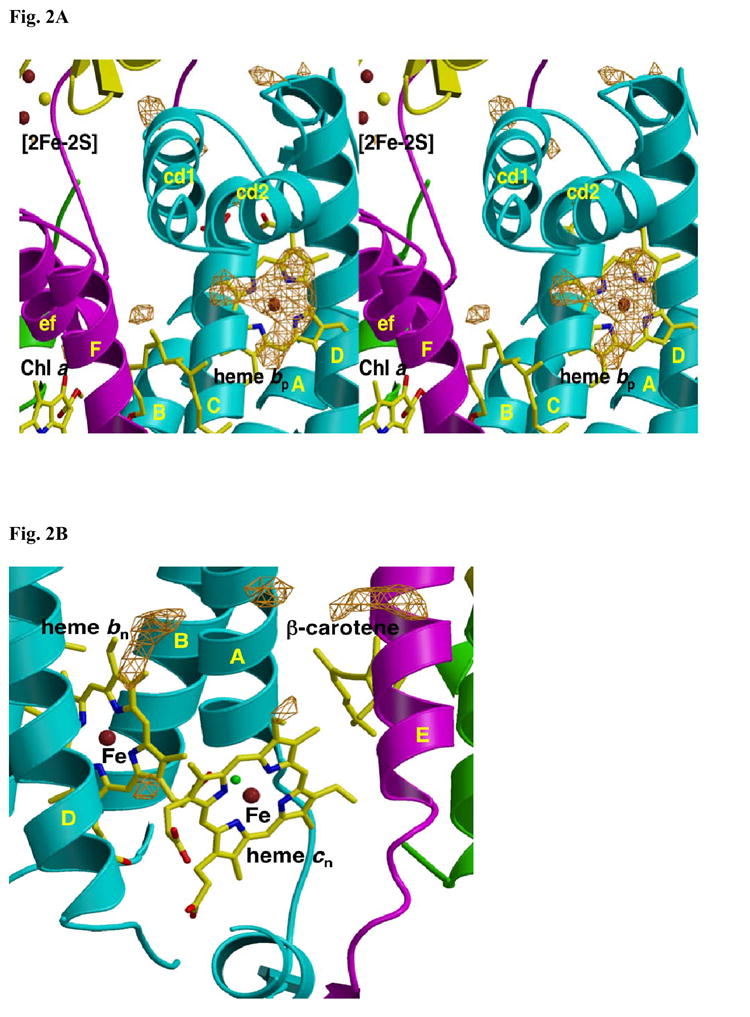

2. p-side (near the Rieske cluster), and n-side (near heme cn) difference maps in the absence of inhibitors

Fo – Fc maps of the native structure (with Cd2+), in the absence of quinone analogue inhibitors, show no significant density immediately adjacent to the p-side 2Fe-2S cluster (Fig. 2A) and the n-side hemes bn or cn (Fig. 2B). On the p-side, additional electron density seen in the Fo –Fc map under the cd2 loop connecting the C and D TM helices (Fig. 2A) presumably arises from lipid head group(s) or bound detergent (see Discussion). The small patches of background electron density seen in the Fo-Fc difference map on the n-side of heme bn (Fig. 2B) and on the n-side of β-carotene near the E helix, have not been identified and are ascribed to bound lipid, detergent, or PEG.

Fig. 2.

Fo-Fc difference map on [A] p- and [B] n-side of the native b6f complex in the absence of added inhibitor (“native” structure). TM helices and surface helices within loops are labeled in upper and lower case, respectively. [A] Fo-Fc difference map, contoured at 4σ, in the native (with Cd2+) b6f complex. Origin of electron density under the cd2 loop, presumably lipid and/or detergent, is not known. [B] Fo-Fc difference map of n-side background electron density in the native (with Cd2+) b6f complex. Fo-Fc map contoured at 4σ.

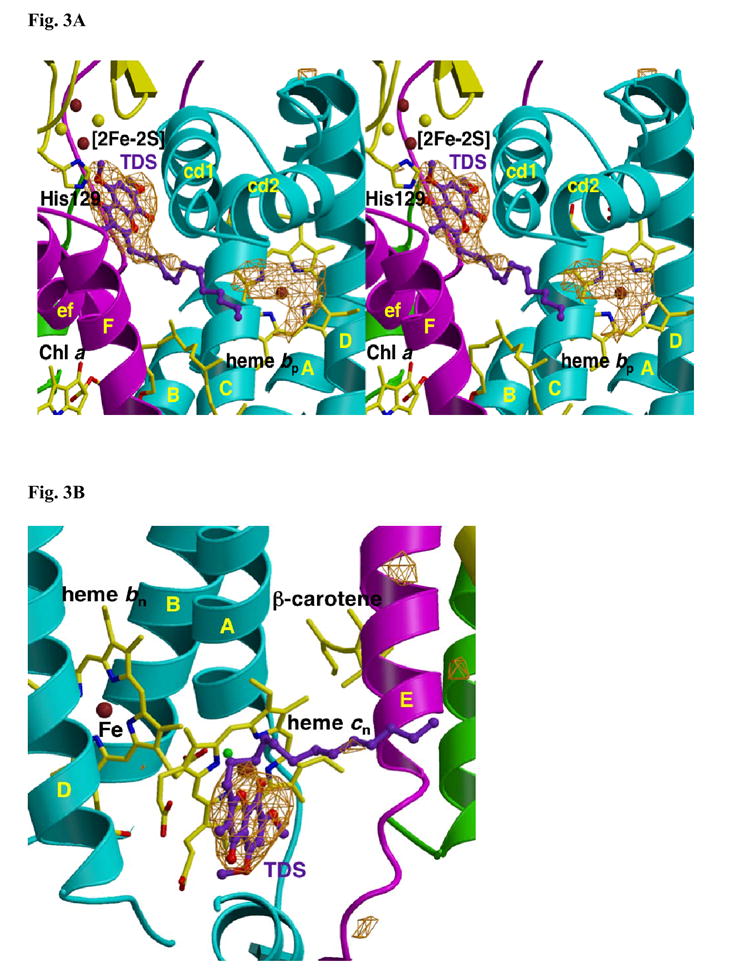

3. p- side binding site of TDS

The site of inhibition by stigmatellin on the p-side of the bc1 complex, and the site of inhibition by tri-decyl stigmatellin in the b6f complex were defined in structure studies of the bc1 17; 20; 23-25 and b6f 9complex. At his site the chromone ring of stigmatellin or TDS is seen to be close enough to the imidazole of a histidine ligand of the [2Fe-2S] cluster to form an H-bond. This bond would provide the pathway for H+ transfer from the bound quinol, PQH2, to the p-side aqueous phase.

In the original study on the structure of the b6f complex in M. laminosus, it was concluded that the TDS was oriented “ring-out” based on electron density seen outside the entrance portal that connects the quinone exchange cavity and the p-side inhibitor binding niche 8. Now that a better native structure is available, it can be seen that this density under the cd2 loop and outside the entrance portal from the inter-monomer cavity to the p-side quinone binding niche is present in both the native (Fig. 2A) and TDS (Fig. 3A) structures. The R-factors of the TDS structure are Rcryst = 0. 201 and Rfree = 0.258 (Table I). The previous inference 8 about the ‘ring-out’ TDS structure was a consequence of the fact that addition of the lipid necessary for crystallization 49 prior to TDS prevented binding of TDS. The presence of electron density at this position in the absence of TDS was not detected because of a native structure of sufficient resolution was not available. When TDS was added before augmentation with lipid, electron density attributable to the double ring of the TDS in a “ring-in” conformation is seen to be sufficiently close to form an H-bond between O4 of the stigmatellin chromone ring and the imidazole of the His129 ligand to the [2Fe-2S] cluster (Fig. 3A). The additional electron density outside the entrance portal (Figs. 2A, 3A) 8 is now attributed to unidentified lipid head-group(s) and/or bound detergent.

Fig. 3. Fo-Fc difference map of (A) p- and (B) n-side binding site of TDS in the b6f complex.

(A) p-side. The extra density within H-bond distance of the His129 ligand of the [2Fe-2S] cluster and between the ‘ef’ and ‘cd1’ loops is attributed to the chromone ring of TDS. As in Fig. 2A, the origin of the electron density under the cd2 loop, presumably lipid and/or detergent, is not known. (B) n-side. The position of TDS is shown relative to heme cn, which is exposed to the quinone-exchange cavity. TDS is on the side of heme cn distal to heme bn. TM helices and surface helices within loops labeled as in Fig. 2. Fo-Fc maps contoured at 4σ.

4. n- side binding site of TDS

TDS is considered to be a well-defined p-side inhibitor in cytochrome bc1 and b6f complexes. The appearance of electron density arising from TDS in the Fo – Fc difference map on the n-side of the complex near heme cn (Fig. 3B) was not expected. No such site of inhibition by stigmatellin in the bc1 complex has been inferred from spectroscopic/electron transfer studies, nor seen in the bc1 crystal structures. Electron density tentatively ascribed to plastoquinone in a figure of the environment around heme cn in C. reinhardtii 9 may arise from TDS, which was present during the crystallization of the complex. An n-side binding site for stigmatellin in bc1 and b6f complexes was suggested by the perturbation by stigmatellin cytochrome b difference spectra for hemes bp and bn and in both complexes50.

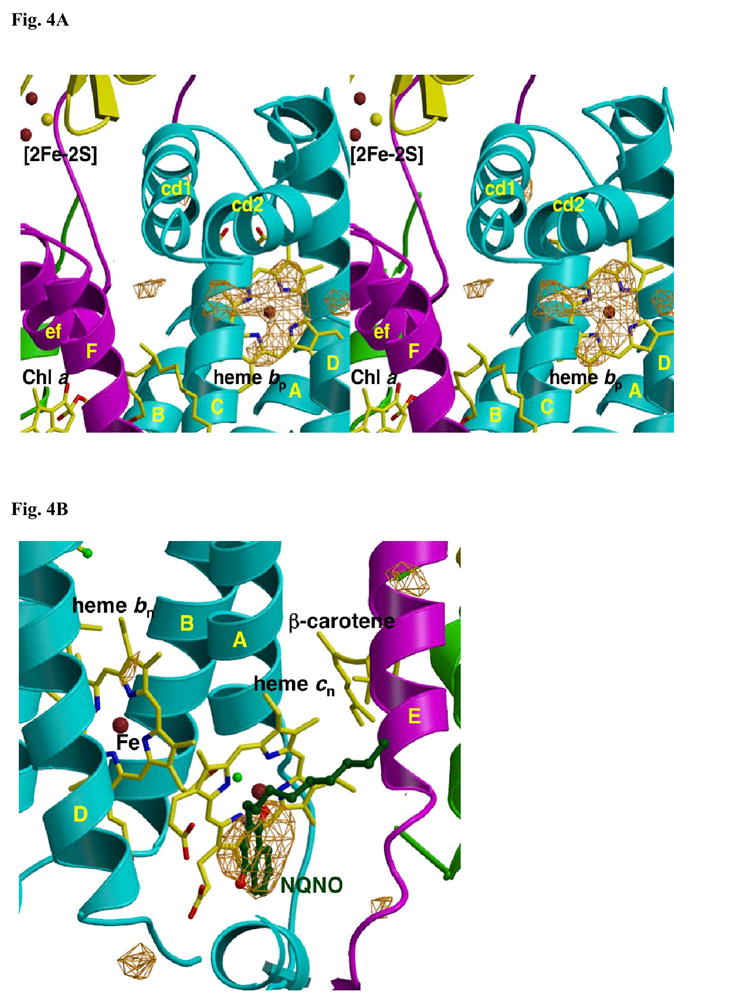

5. An NQNO heme cn ligand binding site

The effect of the quinone analogue NQNO on the light-induced reduction of heme bn in the b6f complex resembles the effect of antimycin A, a potent inhibitor of the cytochrome bc1 complex 25, on heme bn in the bc1 complex. However, antimycin does not affect the light-induced reduction of heme bn in the b6f complex51, either because antimycin binds more weakly to heme cn or that heme cn occludes the projected antimycin binding site in the b6f complex (not shown). The binding site of NQNO was sought through co-crystallization with the complex with R-factors, Rcryst = 0.224 and Rfree = 0.273 (Table I). The Fo – Fc difference map, which shows the [2Fe-2S] cluster and the p-side portal in the “roof” of the cavity, did not show any additional density on the p-side (Fig. 4A) in addition to that seen in the absence of added inhibitor (Fig. 2A). The p-side plastoquinone binding niche that includes the [2Fe-2S] cluster and the p-side portal in the “roof” of the cavity is shown. On the n-side, the difference map revealed a density consistent with NQNO serving as an axial ligand of heme cn, distal to the water ligand and heme bn (Fig. 4B). No electron density was detected at this position in the native Fo – Fc difference map (Fig. 2B). The binding of NQNO as an apparent ligand to heme cn, together with the ability of TDS to bind similarly, reinforces the inference that the physiological ligand of heme cn is plastoquinone.

Fig. 4. Fo-Fc difference map of (a) p-side and (b) n-side binding site of NQNO in the b6f complex.

(A) As in Fig. 2A, the origin of the electron density under the cd2 loop, presumably lipid and/or detergent, is not known. The p-side plastoquinone binding niche that includes the [2Fe-2S] cluster and the p-side portal in the “roof” of the cavity is shown. (B) The Fo – Fc difference map in the region of heme cn on the n-side of the b6f complex shows the n-side binding site of NQNO. TM helices and surface helices within loops are labeled as in Fig. 2. Fo-Fc maps are contoured at 4σ.

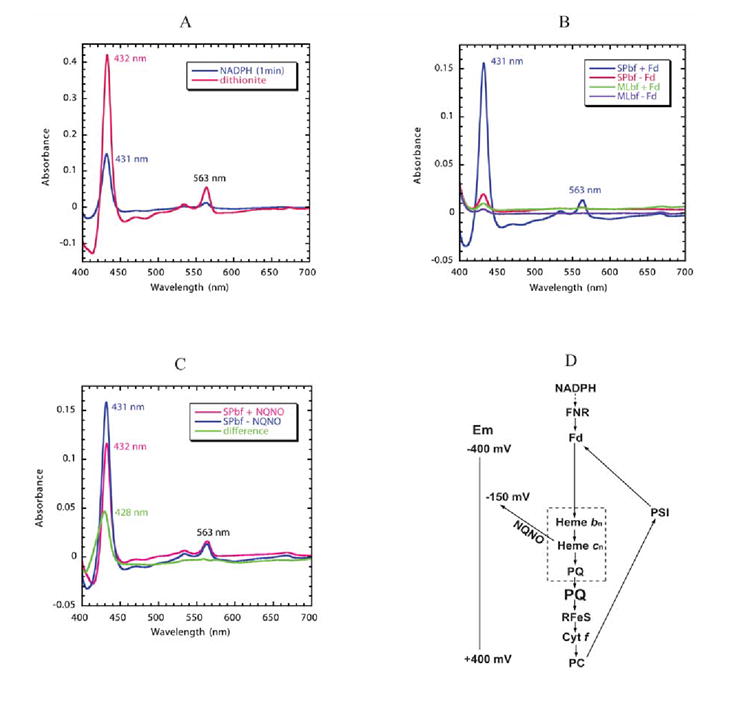

6. Redox consequences of interaction of NQNO with heme cn; spectrophotometric detection of cn reduction by reduced ferredoxin

Detection of heme cn in optical difference spectra of the b6f complex is difficult because its α-band is flat with a small extinction coefficient and the Soret band is masked by the absorbance bands of three hemes, f, bn, and bp, and also chlorophyll a. The presence of FNR in the b6f complex prepared from spinach 14; 52 and the ability of NADPH-reduced ferredoxin to reduce cytochrome b in the complex suggested that the complex might participate in the pathway of cyclic electron transport linked to reduction of ferredoxin by photosystem I 14. However, at the time of the FNR studies, the existence of heme cn was not known, and the possibility that it might also be reduced by ferredoxin was not realized. In the presence of pre-reduced cytochrome f, the amplitude of the Soret band of heme bn, caused by addition of NADPH as reductant, is seen one minute after addition to be somewhat less than half that caused by dithionite (Fig. 5A). This reduction of heme bn requires both FNR, which is present in the spinach but not the M. laminosus complex, and ferredoxin (Fig. 5B). Ferredoxin-dependent reduction of cytochrome b6 53, inferred to be heme bn 54, has previously been observed.

Fig. 5. Reduction of hemes bn/cn by reduced ferredoxin/FNR.

The reaction solution contained 1.5 μM spinach b6f complex with bound FNR and 3 μM spinach ferredoxin. Semi-anaerobic conditions were obtained through the addition of 10 mM glucose and 160 units of glucose oxidase. Decyl-plastoquinol (50 μM) was present to eliminate any contribution of cytochrome f to the difference spectra. Cytochrome b6 /cn reduction was initiated by addition of 0.3 mM NADPH. (A) Comparison of reduction of spinach b6f complex by NADPH/ferredoxin 14 and dithionite. The NADPH/ferredoxin minus decyl-plastoquinol difference spectrum (blue trace) was measured 1 min after addition of NADPH. The spectrum of fully reduced cytochrome b6 (pink) was obtained by addition of dithionite. (B) Dependence of reduction of hemes bn/cn reduction on the presence of FNR and ferredoxin. Reduction of spinach b6f complex following addition of NADPH in the presence (blue) or absence (red) of ferredoxin (3 μM), and of M. laminosus b6f complex, which does not have bound FNR, in the presence (green) or absence (purple) of ferredoxin. All spectra were measured 1 min after addition of NADPH. (C) Double difference spectrum, normalized at 563 nm, showing the Soret band spectrum of heme cn (green), measured as the difference between the spectrum obtained in the presence and absence of NQNO. Difference spectra obtained in the absence (blue) and presence (pink) of NQNO (final concentration, 25 μM). (D) Proposed pathway of reduction of hemes bn and cn by reduced ferredoxin (Fd) in a Q cycle or cyclic pathway in which ferredoxin is reduced physiologically by the photosystem I reaction center and by NADPH in the present experiment. The requirement of FNR and Fd for the pathway of heme bn reduction by NADPH is defined by the data shown in Fig. 5B. The ability of NQNO to block the pathway at the site of heme cn is ascribed to NQNO binding as a ligand of this heme (Fig. 4B) and the NQNO-induced decrease in Em7 of heme cn 55. The inference that hemes bn and cn, together with PQ, are part of a complex in which PQ serves as a ligand of heme cn is based on the proximity of the two hemes 8; 9, their interaction measured by EPR 66, and binding of the quinone analogue inhibitors, TDS (Fig. 3B) and NQNO (Fig. 4B).

In the presence of NQNO, the Soret spectrum is shifted by 1 nm to longer wavelengths. A double difference spectrum, b6f complex in the absence minus the presence of NQNO, shows a difference band for reduced heme with a peak at 428 nm (Fig. 5C), presumably belonging to heme cn 55; 56. A similar result was obtained with butyl-isocyanide (data not shown), previously shown to interact with heme cn 56. It is inferred that the plus/minus NQNO difference spectrum of the Soret band, having a peak at 428 nm diagnostic for heme cn, is a consequence of the interaction of heme cn with NQNO, which results in the large (ca. - 225 mV) decrease in the heme cn midpoint potential55. It should be noted that the ± NQNO difference spectrum in the α-band region is featureless.

The changes caused by NQNO can be understood by assuming an electron transport pathway from reduced ferredoxin, which is the physiological acceptor of reducing equivalents provided by photosystem I (Fig. 5D), via FNR to hemes bn and cn ordered in terms of their midpoint redox potentials, Em7 ≅ -50 mV 54; 57 and + 75 mV 55, respectively. The increase in the amplitude of flash-induced reduction of heme bn in the presence of NQNO 54; 58; 59 is inferred to be a consequence of the NQNO-induced decrease in Em7 to ~ -150 mV of heme cn, and a resulting unfavorable equilibrium and large energy barrier for electron transfer from bn to cn (Fig. 5D). The complex formed by hemes bn, cn, and the inferred bound PQ ligand of heme cn, that would be a donor to the PQ pool (larger font), is shown (Fig. 5D).

Discussion

1. p-side cadmium binding sites

As previously found for the effect of Cu2+ on the electron transfer rate in the b6f complex47, addition of Cu2+ or Cd2+ at a concentration of 10 μM also caused substantial inhibition, although in the present experiments the extent of this inhibition was only about 50 % of the uninhibited rate (data not shown). In the bovine mitochondrial cytochrome bc1 complex, Zn2+ was found to bind more tightly than any other divalent cation, and was proposed to bind to a protonatable group, perhaps a histidine, in the proton channel associated with the p-side quinol oxidation 60. In the Rb. sphaeroides photosynthetic bacterial bc1 complex, Zn2+ inhibited the electrochromic band shift, oxidation of heme bn, re-reduction after an oxidizing light flash of cytochrome c1, and proton release into the chromatophore lumen 61. In the bacterial photosynthetic reaction center, a Cd2+ binding site bridging an Asp and two His residues, a coordination very similar to the major Cd1 binding site of Cd2+ in the b6f complex (Fig. 1), is associated with inhibition of the reduction and protonation of the QB quinone 62. In the case of the two Cd2+ sites on the p-side of the b6f complex, it is not known at present whether the comparatively small ~50 % inhibition of electron transport caused by added Cd2+ could be a consequence of the presence of background divalent ions in the medium. Regarding a possible effect of divalent ions on charge transfer, the smallest distance between a Cd2+ binding site and residues known to be involved in H+ or electron transfer is 12-13 Å between Cd2+ and glutamate-78 or tryptophan-79 of the “PEWY” segment implicated in the transfer pathway of the second H+ to the p-side aqueous phase 63.

2. p-side “ring-in” TDS binding site

The p-side Fo – Fc difference map for the quinone analogue inhibitor TDS shows electron density in the quinone exchange cavity outside the 11 Å × 12 Å portal entry to the iron-sulfur cluster binding niche, similar to the density that has previously been reported and inferred to be associated with a “ring-out” conformation of the TDS 8. The comparison with a native structure having much better resolution (Fig. 1; Table I) indicated that this density is intrinsic to the structure, presumably associated with lipid head-group(s) and/or detergent, in the roof of the exchange cavity. The addition of lipid, which is necessary to stabilize the b6f complex for crystallization 49, prior to addition of TDS, can apparently block the binding of the quinone analogue inhibitors. In the present study, TDS was added before the addition of lipid. This resulted in a prominent electron density that can be associated with the TDS chromone ring close to the His129 imidazole ligand of the [2Fe-2S] cluster (Fig. 3A). A study of the properties of the quinone passage portal indicated that residue 81 is critical for the efficiency of inhibition of TDS or stigmatellin 64. The efficiency of inhibition of the reduction of cytochrome f after oxidation by a light flash in the Synechococcus sp. PCC 7002 was increased by a factor of 10-100 when Leu81 at the entrance to the portal was changed by site-directed mutagenesis to Phe. An explanation alternative to the original inference that the Leu81Phe mutation allowed the more efficient “ring-in” conformation to replace the ‘ring-out’ orientation 64 is that the entrance portal either has a smaller size or smaller degree of flexibility in the cyanobacterial b6f complex, in which inhibition by TDS and stigmatellin is substantially less effective.

3. An n-side TDS binding site

It was unexpected to find that TDS also has a prominent binding site on the n-side of the complex, where it is in a position to be an axial ligand of heme cn (Fig. 3B). The possibility of an n-side binding site near heme bn was indicated in a previous study on both b6f and bc1 complexes 50. The existence of both n- and p-side binding sites for TDS raises the question as whether it should be considered that many of the quinone analogue inhibitors, presently described as n- or p-side in their action, may in fact be able to bind on both sides of the complex, although with different affinities. With the commonly used flash spectroscopic probes of inhibitor action via the rate and amplitude of cytochrome f /c1 turnover, it would be difficult to discern an n-side mode of action of an inhibitor with significant p-side activity.

4. The n-side NQNO binding site

NQNO axial ligation of heme cn, and the resulting large (ca. 225 mV) negative shift in midpoint potential of heme cn 55, as summarized in the pathway shown in Fig. 5D, provide an explanation for the decreased rate of heme bn oxidation and resulting increased amplitude of light-induced reduction of heme bn 54; 59; 65, and the decreased extent of heme cn reduction by reduced ferredoxin which allows detection of the heme cn Soret band in a chemical difference spectrum (Fig. 5C). The low field EPR spectrum of the b6f complex, attributed to spin interaction between the closely spaced hemes cn and bn , is altered by the presence of NQNO 66. The interaction between hemes bn and cn suggests that the two hemes may be able to act as a two electron donor to PQ 66 (Fig. 5D). A two electron reduction of PQ, which would avoid formation of plasto-semiquinone that could reduce O2 to superoxide and thus form reactive oxygen species, could be a crucial protection reaction in an oxygen-rich membrane.

5. PQ as the physiological ligand of heme cn; pathways of linear and cyclic electron transfer

The binding of the two quinone analogue inhibitors, TDS and NQNO, as axial ligands of heme cn implies that plastoquinone positioned at the interface between heme cn and the large inter-monomer quinone exchange cavity is the physiological ligand of heme cn (Fig. 5D). Thus, the n-side pathway to PQ, which serves as the trans-membrane proton and electron carrier would be the same, whether electrons are provided to heme bn by a Q cycle connected to the linear or non-cyclic electron transport chain, or from ferredoxin-FNR as part of a cyclic pathway connected to photosystem I (Fig. 5D).

O2 as a potential ligand of heme cn

By analogy with hemoglobin, myoglobin, cytochrome oxidase, etc., the apparently free axial ligand position on the cavity side of heme cn would seem to be a potential ligand binding site for molecular O2. However, such a molecular O2 cannot be seen and at best could be only weakly bound, because a water or OH- molecule on the other side of heme cn can be seen to connect its Fe atom with a propionate O atom of heme bn.

6. Role of the b6f complex in the photosystem I cyclic pathway

A function of the b6f complex in the PSI cyclic pathway has been discussed extensively. The absence of an effect of antimycin A on the flash-induced reduction of heme bn led to the conclusion that the b6f complex is not involved in the cyclic pathway, but that there is an alternate ferredoxin:quinone oxidoreductase (FQR) 51. However, it has not been possible to isolate this hypothetical oxido-reductase. The overlapping of heme cn with the projection of the antimycin site to the b6f complex from its binding site in the bc1 complex might suggest that antimycin A would not be a good inhibitor of a cyclic pathway that passes through hemes bn- cn. However, inhibition of a ferredoxin-mediated PSI-linked cyclic pathway by antimycin is well documented 51; 67-69. On the basis of the data for TDS (Fig. 3B) and NQNO (Fig. 4B) binding as a ligand to heme cn, the absence of an antimycin-induced increase in amplitude of flash-induced cytochrome b6 reduction 51 could be explained by weaker antimycin binding with marginal inhibitory effects.

Following the description of FNR in the b6f complex 14, and the re-discovery of the unique heme cn in the structures of the b6f complex 8; 9, there have been further studies on the cyclic pathway in higher plants and the role of the b6f complex in re-entry of electrons and protons into the membrane 12; 70; 71. Recent data describe a high efficiency of photosystem I-linked cyclic electron transport that implies a separate domain, i.e., that of the non-appressed thylakoid membranes for the cyclic pathway 70; 71. It had been proposed that the b6f complex responsible for cyclic electron transport is structurally separated in the membrane, and is located in the chloroplast non-appressed membrane domain 70, where it is distinguished by the presence of bound FNR, which would not be present in the appressed membrane fraction of the b6f complex 70. More recently, the mechanism of regulation of cyclic vs. linear flow has been inferred to be regulated by the redox state of FNR in the stromal compartment 12, a model that bears some resemblance to an earlier proposal 67. A role of heme cn in the pathway of PSI-linked cyclic electron transport is an obvious general hypothesis.

7. Side specificity of binding of Q analogue inhibitors; n- to p-side conformational changes

The finding that there is a well-defined binding site of TDS on the n-side of the b6f complex was unexpected. The TDS binding site on the p-side close to a His ligand of the [2Fe-2S] cluster, is documented in both bc120; 25 and b6f 9 complexes. Although NQNO is regarded as an n-side inhibitor, an NQNO binding site on both sides of the bc1 complex has been defined in crystal structures of the bovine bc1 complex22. The existence of a TDS site on both sides of the complex documented above (Figs. 3A, 4A) raises the question of the side specificity of binding of these inhibitors, which is relevant to the question of conformational changes transmitted across the complex by inhibitor binding. In the Rb. capsulatus bacterial bc1 complex, it has been concluded that binding of the n-side inhibitors, HQNO and antimycin A, influences the interactions and environment of the ubiquinol donor to the [2Fe-2S] cluster on the p-side, implying the existence of inhibitor-induced n to p-side conformational changes that span the complex72. n to p-side conformational changes involving antimycin A binding have also been proposed in the yeast bc1 complex 73. The importance of such trans-complex and trans-membrane conformational changes extends beyond the cytochrome bc complexes, as it relates to the mechanism of trans-membrane signal transduction 46.

In the case of the b6f complex, it has been found that NQNO inhibits the rate of cytochrome f reduction at the smallest concentrations that cause an increased amplitude of light-induced heme bn reduction (59; S. Heimann, unpublished data). This implies: (i) NQNO exerts a structure change on the p-side from its binding site on the n-side; or (ii) there is a second NQNO binding site on the p-side that is not detected at the present resolution (3.55 Å) of the b6f structure with NQNO. At the present level of resolution (Table I), the electron density data show no p-side density attributable to NQNO, nor any p-side structure change.

Materials and Methods

Purification of the cytochrome b6f complex

The cytochrome b6f complex from spinach thylakoid membranes and the thermophilic cyanobacterium, Mastigocladus laminosus, was purified as described previously 74.

Crystallization of the cytochrome b6f complex

Crystals of the cytochrome b6f complex were obtained by hanging drop vapor diffusion at 4°C or 20°C. For crystallization, the b6f complex was concentrated to 20 mg/ml in a solution containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.05% β-D-undecyl-maltoside, and 0.01% (w/v) dioleolyl-phosphatidylcholine 49; 74. 2 μl of protein solution was mixed with an equal volume of reservoir solution containing 100 mM Tris-HCl, (pH 8.5), 200 mM MgCl2, 40 mM CdCl2 and 15-18% PEG 550. Crystals were grown for 5-7 days at 4°C or for 2-3 days at 20°C. Co-crystallization with the quinone analogue inhibitors, NQNO and TDS, were carried out, respectively, in the presence of 125 μM NQNO diluted 80-fold from a 10 mM stock solution in ethanol, and 100 μM TDS diluted 200-fold from a 20 mM stock solution in ethanol, with a ratio in each case of inhibitor: protein, mol: mol ≅ 5. Additions of inhibitors were necessarily made before the augmentation with DOPC lipid, as addition of lipid before inhibitor seemed to prevent or decrease binding of inhibitors.

X-ray data collection and structure refinement

Native, NQNO and TDS data sets were collected under cryo conditions (100° K) using beamline SBC 19-ID at the Advanced Photon Source (APS), Argonne, IL. Data reduction and scaling were processed using HKL2000 75. The structure of the native crystal was solved by molecular replacement using MOLREP from the ‘CCP4’ suite 76 and the b6f monomer (pdb accession number, 1VF5) as the starting model. The structure refinements for native, NQNO and TDS crystals were carried out with REFMAC5 from the CCP4 suite. Structure corrections and model building were carried out using the program ‘O’ 77. The data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Table I. The programs ‘O,’ ‘Molscript’ 78, POVScript 79 and raster3D 80 were used for presentation of molecular graphics.

Reduction of cytochrome b6/cn

Chemical and enzymatic reduction of cytochrome b6 were measured on a Cary 4000 UV-VIS spectrophotometer using a half-bandwidth for the measuring light of 1 nm, a scan rate of 150 nm/min, sampling interval, 0.5 nm, and averaging time, 0.2 sec. The measurements were carried out in a 3 ml anaerobic cuvette containing 2.5 ml TNE buffer (30 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.05% UDM), and 1.5 μM spinach b6f complex containing intrinsically bound FNR 14 or M. laminosus complex not containing FNR, together with 10 mM glucose, glucose oxidase (type X-S from A. nidulans, 160 units), 3 μM ferredoxin, 50 μM decyl-plastoquinol, and a quinol analogue inhibitor in some experiments. The mixture was magnetically stirred and argon passed over the sample for 1 h, after which a baseline spectrum was measured. Reduction of cytochrome b6 was initiated by addition of NADPH to a final concentration of 0.3 mM. The difference spectrum of the cytochrome complex reduced by NADPH, relative to that in which cytochrome f alone was reduced by decyl-plastoquinol, was measured as a function of time after addition of NADPH.

Acknowledgments

This study has been supported by U. S. NIH GM-38323 (WAC) and a Grant-in-Aid [B] for Young Scientists from The Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (EY). We thank G. Kurisu and J. L. Smith for their central role in earlier stages of these studies, D. Baniulis and X. Shi for contributions to the experiments, S. Heimann, M. Hendrich, and A. Mulkidjanian for helpful discussions, and P. Rich for a generous gift of tridecyl-stigmatellin. Much of the X-ray structure analysis was carried out at beam line SBC-19ID at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory (supported by U. S. DOE W31-109-ENG-389) where S. Ginell, J. Lazarz, and F. Rotella provided important advice and support.

Abbreviations

- DBMIB

2,5-dibromo-3-methyl-6- isopropyl-p-benzoquinone

- Δμ̃H+

trans-membrane proton electrochemical potential gradient

- Em7

midpoint redox potential at pH 7

- EPR

electron paramagnetic resonance

- FNR

ferredoxin:NADP+ reductase

- FQR

ferredoxin:quinone oxido-reductase

- heme cn

heme covalently bound by one thioether bond that is adjacent to heme bn

- ISP

iron-sulfur protein

- n/p

electro-chemically negative/positive sides of the membrane

- NQNO

2n-nonyl-4-hydroxy-quinoline-N-oxide

- PQ

plastoquinone

- RFeS

Rieske [2Fe-2S] cluster

- TDS

tridecyl-stigmatellin

- TM

trans-membrane

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kallas T. The cytochrome b6f complex. In: Bryant DA, editor. The Molecular Biology of Cyanobacteria. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht: 1994. pp. 259–317. [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Keefe DP. Structure and function of the chloroplast cytochrome bf complex. Photosynth Res. 1988;17:189–216. doi: 10.1007/BF00035448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen JF. Cytochrome b6f: structure for signaling and vectorial metabolism. Trends in Plant Science. 2004;9:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurisu G, Zhang H, Smith JL, Cramer WA. Structure and function of the cytochrome b6f complex of oxygenic photosynthesis. Proteins, Nucleic Acids, and Enzymes. 2004;49:1265–1273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith JL, Zhang H, Yan J, Kurisu G, Cramer WA. Cytochrome bc complexes: a common core of structure and function surrounded by diversity in the outlying provinces. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:432–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cramer WA, Zhang H, Yan J, Kurisu G, Smith JL. Evolution of photosynthesis: time-independent structure of the cytochrome b6f complex. Biochemistry. 2004;43:5921–9. doi: 10.1021/bi049444o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cramer WA, Zhang H, Yan J, Kurisu G, Smith JL. Trans-membrane traffic in the cytochrome b6f complex. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:769–790. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurisu G, Zhang H, Smith JL, Cramer WA. Structure of the cytochrome b6f complex of oxygenic photosynthesis: tuning the cavity. Science. 2003;302:1009–1014. doi: 10.1126/science.1090165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stroebel D, Choquet Y, Popot J-L, Picot D. An atypical heam in the cytochrome b6f complex. Nature. 2003;426:413–418. doi: 10.1038/nature02155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yan J, Kurisu G, Cramer WA. Structure of the cytochrome b6f complex: Binding site and intraprotein transfer of the quinone analogue inhibitor 2,5-dibromo-3-methyl-6-isopropyl-p-benzoquinone. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:67–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504909102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finazzi G, Forti G. Metabolic flexibility of the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii as revealed by the link between state transitions and cyclic electron flow. Photosynth Res. 2004;82:327–338. doi: 10.1007/s11120-004-0359-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joliot P, Joliot A. Cyclic electron flow in C3 plants. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:362–368. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitelegge JP, Zhang H, Taylor R, Cramer WA. Full subunit coverage liquid chromatography electrospray-ionization mass spectrometry (LCMS+) of an oligomeric membrane protein complex: the cytochrome b6f complex from spinach and the cyanobacterium, M. laminosus. Molecular Cellular Proteomics. 2002;1:816–827. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m200045-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang H, Whitelegge JP, Cramer WA. Ferredoxin:NADP+ oxidoreductase is a subunit of the chloroplast cytochrome b6f complex. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38159–38165. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105454200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Widger WR, Cramer WA, Herrmann RG, Trebst A. Sequence homology and structural similarity between the b cytochrome of mitochondrial complex III and the chloroplast b6f complex: position of the cytochrome b hemes in the membrane. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:674–678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.3.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xia D, Yu C-A, Kim H, Xia J-Z, Kachurin AM, Yu L, Deisenhofer J. Crystal structure of the cytochrome bc1 complex from bovine heart mitochondria. Science. 1997;277:60–66. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Z, Huang L, Shulmeister VM, Chi YI, Kim KK, Hung LW, Crofts AR, Berry EA, Kim SH. Electron transfer by domain movement in cytochrome bc1. Nature. 1998;392:677–84. doi: 10.1038/33612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwata S, Lee JW, Okada K, Lee JK, Iwata M, Rasmussen B, Link TA, Ramaswamy S, Jap BK. Complete structure of the 11-subunit mitochondrial cytochrome bc1 complex. Science. 1998;281:64–71. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5373.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim H, Xia D, Yu CA, Xia JZ, Kachurin AM, Zhang L, Yu L, Deisenhofer J. Inhibitor binding changes domain mobility in the iron-sulfur protein of the mitochondrial bc1 complex from bovine heart. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1998;a 95:8026–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunte C, Koepke J, Lange C, Rosmanith T, Michel H. Structure at 2.3 Å resolution of the cytochrome bc1 complex from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae with an antibody Fv fragment. Structure Fold Des. 2000;8:669–84. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00152-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palsdottir H, Lojero CG, Trumpower BL, Hunte C. Structure of the yeast cytochrome bc1 complex with a hydroxyquinone anion Qo site inhibitor bound. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31303–11. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302195200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao X, Wen X, Esser L, Quinn B, Yu L, Yu C, Xia D. Structural basis for the quinone reduction in the bc1 complex: A comparative analysis of crystal structure of mitochondrial cytochrome bc1 with bound substrate and inhibitors at the Qi site. Biochemistry. 2003;42:9067–9080. doi: 10.1021/bi0341814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Esser L, Quinn B, Li YF, Zhang M, Elberry M, Yu L, Yu CA, Xia D. Crystallographic studies of quinol oxidation site inhibitors: a modified classification of inhibitors for the cytochrome bc1 complex. J Mol Biol. 2004;341:281–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berry EA, Huang L-S, Saechao L-K, Pon NG, Valkova-Valchanova M, Daldal F. X-ray structure of Rhodobacter capsulatus cytochrome bc1: comparison with its mitochondrial and chloroplast counterparts. Photosynth Res. 2004;81:251–275. doi: 10.1023/B:PRES.0000036888.18223.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang LS, Cobessi D, Tung EY, Berry EA. Binding of the respiratory chain inhibitor antimycin to the mitochondrial bc1 complex: a new crystal structure reveals an altered intramolecular hydrogen-bonding pattern. J Mol Biol. 2005;351:573–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.05.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Esser L, Gong X, Yang S, Yu L, Yu CA, Xia D. Surface-modulated motion switch: capture and release of iron-sulfur protein in the cytochrome bc1 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13045–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601149103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang D, Everly RM, Cheng RH, Heymann JB, Schägger H, Sled V, Ohnishi T, Baker TS, Cramer WA. Characterization of the chloroplast cytochrome b6f complex as a structural and functional dimer. Biochemistry. 1994;33:4401–4409. doi: 10.1021/bi00180a038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pierre Y, Breyton C, Lemoine Y, Robert B, Vernotte C, Popot J-L. On the presence and role of a molecule of chlorophyll a in the cytochrome b6f complex. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:21901–21908. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.21901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang H, Huang D, Cramer WA. Stoichiometrically bound beta-carotene in the cytochrome b6f complex of oxygenic photosynthesis protects against oxygen damage. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:1581–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joliot P, Joliot A. The low-potential electron-transfer chain in the cytochrome b/f complex. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;933:319–333. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lavergne J. Membrane potential-dependent reduction of cytochrome b-6 in an algal mutant lacking photosystem I centers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1983;725:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crofts AR. The mechanism of the ubiquinol:cytochrome c oxidoreductases of mitochondria and of Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides. In: Martonosi AN, editor. The Enzymes of Biological Membranes. Vol. 4. Plenum Press; New York: 1985. pp. 347–382. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crofts AR. Proton-coupled electron transfer at the Qo-site of the bc1 complex controls the rate of ubihydroquinone oxidation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1655:77–92. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Graan T, Ort DR. Initial events in the regulation of electron transfer in chloroplasts. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:2831–2836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hope AB. The chloroplast cytochrome bf complex: A critical focus on function. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1993;1143:1–22. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(93)90210-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mitchell P. The protonmotive Q cycle: A general formulation. FEBS Letters. 1975;59:137–139. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(75)80359-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joliot P, Joliot A. Mechanism of proton-pumping in the cytochrome b/f complex. Photosynthesis Research. 1985;9:113–124. doi: 10.1007/BF00029737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rich PR. Mechanisms of quinol oxidation in photosynthesis. Photosynthesis Research. 1985;6:335–348. doi: 10.1007/BF00054107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Joliot P, Joliot A. Electron transfer between photosystem II and the cytochrome b/f : mechanistic and structural implications. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1992;1102:53–61. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sacksteder CA, Kanazawa A, Jacoby ME, Kramer DM. The proton to electron stoichiometry of steady-state photosynthesis in living plants: A proton-pumping Q cycle is continuously engaged. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:14283–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jordan P, Fromme P, Witt H, Klukas O, Saenger W, Krauss N. Three-dimensional structure of cyanobacterial photosystem I at 2.5 A resolution. Nature. 2001;411:909–917. doi: 10.1038/35082000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zouni A, Witt H, Kern J, Fromme P, Krauss N, Saenger W, Orth P. Crystal structure of photosystem II from Synechococcus elongatus at 3.8 A resolution. Nature. 2001;409:739–743. doi: 10.1038/35055589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ferreira KN, Iverson TM, Maghlaoui K, Barber J, Iwata S. Architecture of the photosynthetic oxygen-evolving center. Science. 2004;303:1831–1838. doi: 10.1126/science.1093087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kern J, Loll B, Zouni A, Saenger W, Irrgang KD, Biesiadka J. Cyanobacterial Photosystem II at 3.2 A resolution - the plastoquinone binding pockets. Photosynth Res. 2005;84:153–9. doi: 10.1007/s11120-004-7077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yano J, Kern J, Irrgang K-D, Latimer MJ, Bergmann U, Glatzel P, Pushkar Y, Biesiadka J, Loll B, Sauer K, Messinger J, Zouni A, Yachandra VK. X-ray damage to the Mn4Ca complex in single crystals of photosystem II: A case study for metalloprotein crystallography. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:12047–12052. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505207102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bourne HR. How receptors talk to trimeric G proteins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:134–142. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rao S, Tyryshkin AM, Roberts AG, Bowman MK, Kramer DM. Inhibitory Copper Binding Site on the Spinach Cytochrome b6f Complex: Implication for Qo Site Catalysis. Biochemistry. 2000;39:3285–3296. doi: 10.1021/bi991974a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roberts AG, Bowman MK, Kramer DM. Certain metal irons are inhibitors of cytochrome b6f complex ’Rieske’ iron-sulfur protein domain movements. Biochemistry. 2002;41:4070–4079. doi: 10.1021/bi015996k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang H, Kurisu G, Smith JL, Cramer WA. A defined protein-detergent-lipid complex for crystallization of integral membrane proteins: The cytochrome b6f complex of oxygenic photosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5160–5163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931431100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hauska G, Herald E, Huber C, Nitschke W, Sofrova D. Stigmatellin affects both hemes of cytochrome b in cytochrome b6f /bc1 complexes. Z Naturforsch. 1989;44c:462–467. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moss DA, Bendall DS. Cyclic electron transport in chloroplasts. the Q-cycle and the site of action of antimycin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;767:389–395. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clark RD, Hawkesford MJ, Coughlan SJ, Hind G. Association of ferredoxin-NADP+ oxidoreductase with the chloroplast cytochrome b-f complex. FEBS Lett. 1984;174:137–142. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lam E, Malkin R. Ferredoxin-mediated reduction of cytochrome b-563 in a chloroplast cytochrome b-563/f complex. FEBS Lett. 1982;141:98–101. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Furbacher PN, Girvin ME, Cramer WA. On the question of interheme electron transfer in the chloroplast cytochrome b6in situ. Biochemistry. 1989;28:8990–8998. doi: 10.1021/bi00449a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alric J, Pierre Y, Picot D, Lavergne J, Rappaport F. Spectral and redox characterization of the heme ci of the cytochrome b6f complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15860–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508102102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang H, Primak A, Bowman MK, Kramer DM, Cramer WA. Characterization of the high-spin heme x in the cytochrome b6f complex of oxygenic photosynthesis. Biochemistry. 2004;43:16329–36. doi: 10.1021/bi048363p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Girvin ME, Cramer WA. A redox study of the electron transport pathway responsible for generation of the slow electrochromic phase in chloroplasts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;767:29–38. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(84)90076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Selak MA, Whitmarsh J. Kinetics of the electrogenic step and cytochrome b6 and f redox changes in chloroplasts. FEBS Letters. 1982;150:286–292. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jones RW, Whitmarsh J. Inhibition of electron transfer and electrogenic reaction in the cytochrome b/f complex by 2-n-nonyl-4-hydroxyquinoline N-oxide (NQNO) and 2,5-dibromo-3methyl-6-isopropyl-p-benzoquinone (DBMIB) Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;933:258–268. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Link TA, von Jagow G. Zinc ions inhibit the Qp center of bovine heart mitochondria bc1 complex by blocking a protonatable group. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25001–25006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.25001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klishen SS, Mulkijanian AY. Photosynthesis: Fundamental Aspects to Global Perspectives. Vol. 2. Montreal: 2005. pp. 460–462. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Axelrod HL, Abreusch EC, Paddock ML, Okamura MY. Binding of Cd2+ and Zn2+ inhibit the rate of reduction and protonation of QB. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1542–1547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Finazzi G. Redox-coupled proton pumping activity in cytochrome b6f, as evidenced by the pH dependence of electron transfer in whole cells of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Biochemistry. 2002;41:7475–7482. doi: 10.1021/bi025714w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yan J, Cramer WA. Molecular control of a bimodal distribution of quinone-analogue inhibitor binding sites in the cytochrome b6f complex. J Mol Biol. 2004;344:481–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rich PR, Madgwick SA, Moss DA. The interactions of duroquinol, DBMIB, and NQNO with the chloroplast cytochrome bf complex. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1058:312–328. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zatsman AI, Zhang H, Gunderson WA, Cramer WA, Hendrich MP. Heme-heme interactions in the cytochrome b6f complex: EPR spectroscopy and correlation with structure. J Amer Chem Soc. 2006;128:14246–14247. doi: 10.1021/ja065798m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hosler JP, Yocum CF. Evidence for two photophosphorylation reactions concurrent with ferredoxin-catalyzed non-cyclic electron transport. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985;808:21–31. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bendall DS, Manasse RS. Cyclic phosphorylation and electron transport. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1229:23–38. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tagawa K, Tsujimoto HY, Arnon DL. Role of chloroplast ferredoxin in the energy conversion process of photosynthesis. Biochemistry. 1963;49:567–572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.49.4.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Joliot P, Joliot A. Cyclic electron transfer in plant leaf. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:10209–10214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102306999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Joliot P, Joliot A. Quantification of cyclic and linear electron flows in plants. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:4913–4918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501268102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cooley JW, Ohnishi T, Daldal F. Binding Dynamics at the Quinone Reduction (Q(i)) Site Influence the Equilibrium Interactions of the Iron Sulfur Protein and Hydroquinone Oxidation (Q(o)) Site of the Cytochrome bc1 Complex. Biochemistry. 2005;44:10520–32. doi: 10.1021/bi050571+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Covian R, Trumpower BL. Regulatory interactions between ubiquinol oxidation and ubiquinone reduction sites in the dimeric cytochrome bc1 complex. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:30925–30932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604694200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang H, Cramer WA. Purification and crystallization of the cytochrome b6f complex in oxygenic photosynthesis. In: Carpentier R, editor. Photosynthesis Research Protocols. Vol. 274. Humana Press; Totowa, New Jersey: 2004. pp. 67–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods in Enzymology. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.CCP4. The collaborative computional project, number 4: Programs for protein crystallography. Acta Cryst. 1994;D50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard M. Improved methods for the building of protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Cryst. 1991;A47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kraulis PJ. MOLSCRIPT: A program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J Applied Crystallography. 1991;24:946–950. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fenn TD, Ringe D, Petsko GA. POVScript+: A program for model and data visualization using persistence of vision ray-tracing. J Appl Cryst. 2003;36:944–947. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Merritt EA, Bacon DJ. Raster3D: Photorealistic molecular graphics. Methods in Enzymology. 1997;277:505–524. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(97)77028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]