Abstract

CI represses cro; Cro represses cI. This double negative feedback loop is the core of the classical CI–Cro epigenetic switch of bacteriophage λ. Despite the classical status of this switch, the role in λ development of Cro repression of the PRM promoter for CI has remained unclear. To address this, we created binding site mutations that strongly impaired Cro repression of PRM with only minimal effects on CI regulation of PRM. These mutations had little impact on λ development after infection but strongly inhibited the transition from lysogeny to the lytic pathway. We demonstrate that following inactivation of CI by ultraviolet treatment of lysogens, repression of PRM by Cro is needed to prevent synthesis of new CI that would otherwise significantly impede lytic development. Thus a bistable CI–Cro circuit reinforces the commitment to a developmental transition.

Keywords: Bistability, epigenetic, bacteriophage λ, genetic switch, Cro, transcriptional control

Bacteriophage λ, with its ability to choose between lytic and lysogenic modes of development, has provided an important model system for aiding understanding of the gene regulatory mechanisms and strategies that underpin cell differentiation in more complex organisms (Kauffman 1973; Herskowitz and Hagen 1980; Ptashne 2004; Court et al. 2007; Murray and Gann 2007). Since the late 1960s, it has been known that a portion of the λ genome, encoding the CI and Cro repressors and the promoters they regulate (Fig. 1A), comprises a bistable switch—a gene control circuit that is able to exist stably in either of two distinct, self-sustaining regulatory states: “immune” and “anti-immune” (Eisen et al. 1970; Neubauer and Calef 1970; Toman et al. 1985; Svenningsen et al. 2005). In the immune (CI-dominant) state, the CI protein is expressed from the lysogenic promoter PRM and binds cooperatively to two operators, OR1 and OR2, to repress the PR lytic promoter and thus block transcription of the cro gene. CI simultaneously activates transcription of its own gene from PRM. In the anti-immune (Cro-dominant) state, Cro is expressed from PR and prevents CI expression, presumably by virtue of its high affinity for OR3, where it can bind to repress PRM (Johnson et al. 1978; Takeda 1979; Meyer et al. 1980). This CI–Cro double negative feedback loop, augmented by direct CI positive feedback, provides stable and heritable alternative epigenetic states. Understandably, it has been tempting to assume that the lytic mode of λ development is dependent on the anti-immune state of this switch. For example, in Lewin (1999) it is stated that “Cro...prevents synthesis of the repressor (a necessary action if the lytic cycle is to proceed).” However, although the immune state of the switch is necessary for lysogeny, it is not clear what are the roles of the anti-immune state of the switch and the repression of PRM by Cro during λ lytic development.

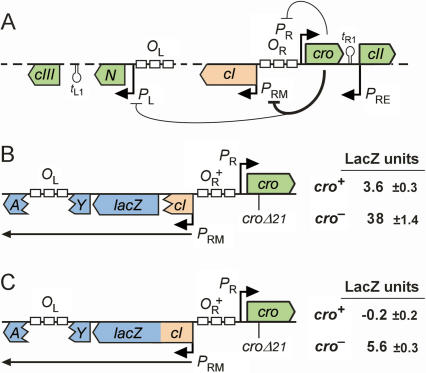

Figure 1.

Cro repression of PRM. (A) Regulation of lytic and lysogenic promoters by Cro. (B) Repression of PRM by single-copy cro in cis. The chromosomally integrated PRM.lacZ transcriptional reporter carries the OR.cro region inserted so that lacZ is transcribed from PRM but is translated from the wild-type lacZ ribosome-binding site (RBS). Wild-type Cro, or a mutant protein carrying a deletion within its HTH DNA-binding motif (croΔ21), is expressed in cis from PR. (C) Repression of CI expression by single-copy cro in cis. The PRM.cI translational reporter is as in B, except that codon 20 of cI is fused to codon 10 of lacZ, such that lacZ is transcribed from PRM and translated from the cI RBS. Errors are 95% confidence intervals.

Cro is essential for λ lytic development, but a large body of indirect evidence indicates that it is Cro’s action in turning down lytic transcription, rather than its repression of PRM, that is critical for lytic development after infection. Cro binds with highest affinity to OR3 but it also binds to OR1 and OR2 at PR and to the operators at PL (Johnson et al. 1978; Takeda 1979; Darling et al. 2000), from where it can exert at least a two- to fourfold turn-down of early lytic transcription (Eisen et al. 1970; Adhya and Gottesman 1982; Svenningsen et al. 2005). Thus, Cro reduces the expression of every lytically expressed gene, including the regulatory genes N, cIII, cII, and Q. λ cI+cro− mutants show a severe defect in lytic development that has been attributed to either an extremely high frequency of lysogenization after infection (Eisen et al. 1970) or a stalling of lytic development without causing increased lysogeny (Folkmanis et al. 1977). In either case, the defect appears not to be due to loss of Cro repression of PRM, but instead results from overexpression of the CII and CIII proteins, as it can be suppressed by cII− and cIII− mutations (Folkmanis et al. 1977). CII, stabilized by CIII, activates an alternative promoter for cI, PRE. CII also activates the PI promoter for the integrase protein that inserts the λ genome as a prophage into the host chromosome, and the PAQ promoter that inhibits the production of the late gene activator Q (Kobiler et al. 2005; Court et al. 2007). Thus high activity of CII in cro− phages should enhance lysogenization and inhibit lytic development. Because of these major pleiotropic effects of cro− mutations, it has not been possible to determine whether Cro repression of PRM is important in the choice between lysis and lysogeny or in the progression of lytic development after infection by cro+ phages.

It seems more likely that Cro repression of PRM is important during prophage induction, the transition from lysogeny to lytic development that is initiated by RecA-stimulated cleavage of CI following DNA damaging treatments such as ultraviolet (UV) irradiation (Bailone et al. 1979; Little 1984). In this situation, CI expression should be more strongly dependent on PRM than CII-activated PRE for two reasons. First, production of CI from PRE appears to be low during prophage induction, in part because CII production is reduced by the SOS-induced OOP antisense RNA (Krinke et al. 1991). In support of this, it has been shown that PRE− mutations do not affect spontaneous phage production from a lysogen (Baek et al. 2003). Second, RecA activity is not always high enough and sustained enough to remove all of the CI present in the lysogen (Bailone et al. 1979), leaving residual CI that should activate PRM and lead to more CI production. It has been proposed that Cro repression of PRM may be needed to prevent recovery of CI levels and re-establishment of repression of the lytic promoters once the RecA signal decays (Johnson et al. 1981).

However, experimental evidence regarding the role of Cro repression of PRM in prophage induction is unclear. Initial experiments showed poor UV induction of a phage bearing mutations in OR3 that reduced Cro repression of PRM (Johnson 1980). But it has since been shown that the poor prophage induction in this mutant was due to a lack of CI binding to OR3, which results in a threefold increase in lysogenic CI levels that is inhibitory to prophage induction (Dodd et al. 2001). Although Svenningsen et al. (2005) found little effect of Cro on PR derepression, interpretation of their experiments is complicated by the use of temperature inactivation of CI and a cro− mutant. Atsumi and Little (2006) created highly modified λ phages in which Cro is substituted by the lac repressor, which was able to repress the lytic promoters but not PRM. It was concluded that Cro repression of PRM is not needed for lytic development and plays only a modulatory role in prophage induction. However, this study is weakened by the lack of a comparison with similarly manipulated phages in which lac repressor is able to repress PRM (see Discussion).

We sought to address these uncertainties in this important model bistable system by clarifying the role of Cro repression of PRM and, by extension, the role of the bistability of the CI–Cro switch in normal λ development. Our approach was to create and characterize operator mutations that specifically inactivated Cro repression of PRM and to measure the effect of these mutations in a wild-type λ background. We found that these mutations had mild effects on the choice between lytic and lysogenic development and on the efficiency of lytic development after infection, but strongly impaired prophage induction by UV, indicating a critical role of Cro repression of PRM in the transition from lysogenic to lytic development. Studies of a cI–cro switch reporter construct confirmed loss of the bistability of the switch due to elimination of the anti-immune state and indicated that Cro repression of PRM is necessary to prevent recovery of CI after UV induction.

Results

Cro repression of PRM

The ability of Cro to strongly repress transcription from PRM (Meyer et al. 1980) was confirmed previously, using a PRM.lacZ reporter with Cro expressed from a multicopy plasmid (Dodd et al. 2001). To gain some appreciation of the extent of repression by Cro that PRM might experience at early times after infection of a cell by a single λ phage or after prophage induction, we compared the activities of chromosomal PRM.lacZ transcriptional reporters that produce either wild-type Cro or a mutant Cro protein in cis from PR (lacZ.PRM.PR.cro+/−) (Fig. 1B). Under steady-state conditions, Cro expression from PR in single copy is sufficient to turn PR down by ∼50% (Svenningsen et al. 2005); A. Palmer, unpubl.). In our reporters, PRM was repressed at least 10-fold by Cro, from 38 to 3.6 LacZ units (Fig. 1B). Our experience with transcriptional fusions is that there is usually a background LacZ level that is partly reporter vector-dependent (∼2.5 U for this vector) and partly insert-dependent. Using a 2.5-U background gives an estimate of Cro repression of PRM of >30-fold (35.5/1.1). We also measured the impact of single-copy Cro on the expression of CI protein from PRM by using a translational fusion, in which the first 20 codons of the cI gene are fused to the lacZ gene (Fig. 1C). LacZ activity in the absence of Cro was 5.6 U and was completely abolished by Cro (Fig. 1C). We conclude that, in the absence of CI, Cro produced from a single-copy cro gene expressed from PR can completely abolish CI expression from PRM in cis. We expect that the weaker repression calculated for the transcriptional fusion is due to the non-PRM contribution to LacZ expression being >2.5 U.

OR mutants defective in Cro repression of PRM

We wished to create mutations that eliminated Cro repression of PRM but had minimal other effects on the intrinsic activities of the PRM and PR promoters and their regulation by CI and Cro. We initially focused on OR3 because previous reporter studies (Meyer et al. 1980) had indicated that Cro represses PRM when bound to OR3 but not when bound to OR2 and OR1 (Fig. 2A). Although CI and Cro recognize the same operators, binding site mutants that differentially affect Cro or CI binding can be obtained as the proteins recognize different bases within the operators. For example, we found previously that the OR3-r1 mutation (Fig. 2A) eliminated CI repression but had no effect on Cro repression of PRM (Dodd et al. 2001). To design the Cro-specific mutants, we were guided by exhaustive studies of the effects of base-pair changes in OR1 on CI and Cro binding (Sarai and Takeda 1989; Takeda et al. 1989).

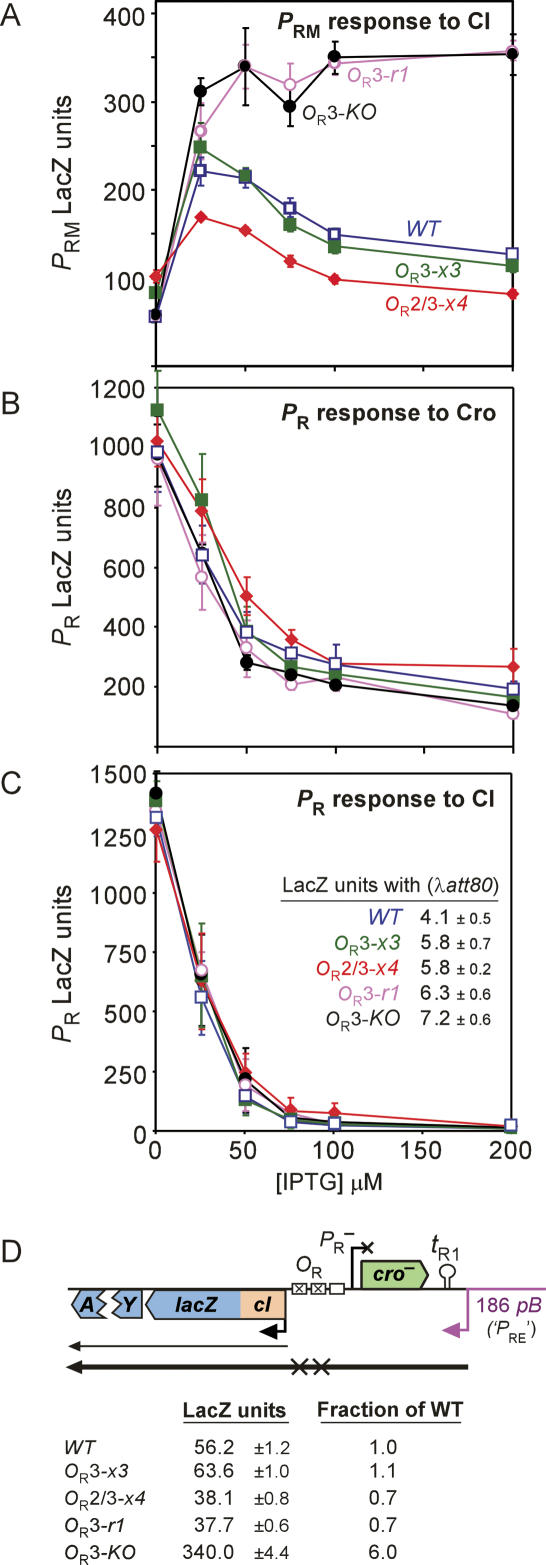

Figure 2.

OR mutations relieving Cro repression of PRM. (A) The PRM-OR-PR region and the mutations used in this study. The c21, r1, r314A, c12, and r204 mutations change the ΔG of Cro binding to OR1 by +1.7, +0.4, +1.7, +1.3, and +1.4 kcal/mol, respectively (Takeda et al. 1989), and the ΔG of CI binding to OR1 by −0.2, +2.9, +1.0, −0.8, and +0.3 kcal/mol, respectively (Sarai and Takeda 1989). (B) Activity of the PRM. lacZ reporter (croΔ21 as in Fig. 1B) carrying KO mutations in OR3 and OR2, in response to Cro supplied from an IPTG-inducible expression plasmid (or an empty vector, dashed curve). LacZ activities have been normalized to aid comparison of repression with the OR2-KO mutation, which decreases PRM intrinsic activity by approximately twofold. (C) Effect of OR mutations on repression of PRM by Cro expressed from a single-copy cro gene in cis. The PRM.lacZ reporters are as in Figure 1B, except that Δcro here indicates truncation of cro at the +43 position of PR. Fold repression is calculated without subtraction of background. (B,C) Errors are 95% confidence intervals.

Removing Cro repression

Many multiple base-pair changes in OR3 were investigated, but no combination completely eliminated Cro repression of PRM when Cro was supplied from a plasmid. To identify the source of this remaining repression of PRM, we endeavored to “knock out” Cro binding to OR3 by changing 9 base pairs (bp) of the 17-bp operator site (Fig. 2A). Surprisingly, this OR3-KO mutant displayed considerable residual repression by plasmid-supplied Cro (Fig. 2B), which we therefore suspected was due to Cro binding to OR2. We confirmed this by making multiple mutations to create an OR2-KO mutant (Fig. 2A). It was only when the OR2-KO and OR3-KO mutations were combined that Cro repression of PRM was eliminated (Fig. 2B). These results show that Cro can repress PRM by binding to either OR3 or OR2 (see Supplemental Material for further discussion).

We were unable to find a combination of OR2 and OR3 mutations that eliminated repression of PRM by Cro expressed from a plasmid, without also strongly affecting intrinsic PRM activity or its activation by CI. However, we reasoned that resistance to a high level of Cro may be an unnecessarily stringent test for the mutations. We therefore measured PRM repression by Cro for the three most promising mutants in the more natural early lytic situation where a single-copy cro gene is expressed by PR in cis to PRM (Fig. 2C). The OR3-x3 mutant combines three mutations at OR3 (Fig. 2A) and, like the OR3-KO mutant, gave only weak repression of PRM by Cro in cis. The addition of the OR2-r204 change to the OR3-x3 mutant, to give the OR2/3-x4 mutant, eliminated PRM repression at this Cro concentration (Fig. 2C). Thus, these mutants seemed to be sufficiently defective in Cro repression of PRM for our purposes.

Additional effects of the mutations

We further examined the above mutations for effects on regulation of PRM and PR. Our initial testing had suggested that the OR3-x3 mutation had small effects on regulation of PRM by CI. Although the OR2/3-x4 mutation appeared to cause a larger alteration in CI regulation, we examined it further because Cro repression of PRM is more defective in this mutant (Fig. 2C). We also tested the OR3-KO mutation further. We expected this mutation to strongly reduce CI repression of PRM and therefore included the OR3-r1 mutant as a control that also eliminates CI repression of PRM but does not affect basal PRM activity or its repression by Cro (Dodd et al. 2001).

Intrinsic PRM activity

Figure 2C shows that in the absence of Cro expression (cro−), the OR3-x3 mutation slightly increased the intrinsic activity of PRM (∼1.3-fold), while the OR2/3-x4 mutation increased it somewhat more (∼1.7-fold). Surprisingly, the OR3-KO mutation did not change basal PRM activity.

Regulation of PRM by CI

Figure 3A shows the response of PRM.lacZ reporters carrying the OR mutations to a range of CI levels supplied by an isopropyl thio-β-D-galactoside (IPTG)-controlled expression plasmid. The wild-type (WT) and OR3-x3 mutant showed quite similar profiles: activation at low CI concentrations due to CI binding at OR2, followed by repression at higher CI concentrations as OR3 becomes occupied. CI repression of PRM in the OR3-x3 mutant was slightly stronger, suggesting that CI may bind slightly better to OR3-x3. Despite its higher basal activity, PRM in the OR2/3-x4 mutant was only ∼75% as active as wild-type PRM over a range of CI concentrations, suggesting that the r204 mutation interferes with CI activation of PRM. The OR3-KO mutation showed the same response of PRM to CI previously described for the OR3-r1 mutant (Dodd et al. 2001).

Figure 3.

Effects of the mutations on other aspects of OR regulation. Response of PRM.lacZ reporters (A) and PR.lacZ reporters (B,C) to CI (A,C), or Cro (B) supplied by IPTG-inducible plasmids. The λ fragment extends from the +62 of PRM to the +43 of PR. The inset in C shows reporter expression with CI supplied from a λatt80 prophage. (D) Translational fusion reporters showing the effect of the OR mutations on cI translation from PRE mRNA. λ PRE is substituted by the constitutive 186 pB promoter. (A–D) Error bars and ranges are 95% confidence limits.

PR activity and its regulation by CI and Cro

Figure 3,B and C, shows the response of PR.lacZ reporters, carrying the OR mutations, to Cro or CI supplied from plasmids or to CI supplied by a λ prophage. Although there are some small reproducible effects of the OR3 and OR2 mutations, the basal activity of PR and its regulation by CI and Cro remained essentially the same. There was evidence for a slight reduction of Cro repression of PR in the OR2/3-x4 mutant (Fig. 3C), consistent with weakening of Cro binding to OR2 (Meyer et al. 1980). Incidentally, this is possibly the first demonstration that Cro binding to OR3 does not affect PR.

Translation of cI from PRE mRNA

The OR mutations lie just upstream of the cI start codon, and we realized that they could well affect ribosome binding for cI translation from the PRE mRNA (Fig. 2A). The cI mRNA produced from PRM begins at the cI start codon and therefore is not affected by the OR mutations. To measure this potential effect, we constructed the translational reporters shown in Figure 3D, in which cI codon 20 was fused to the lacZ reading frame and the λ PRE promoter was substituted by the constitutive pB promoter from bacteriophage 186 (Kalionis et al. 1986). The cro gene and PR promoter were mutationally inactivated. The wild-type construct gave 56 LacZ units, of which up to ∼5.6 LacZ units could be contributed by translation of the PRM transcript (see Fig. 1C). The OR3-x3, OR3-r1, and OR2/3-x4 mutations had relatively small effects on cI translation from the PRE mRNA, but the OR3-KO mutation increased this translation sixfold. Although this drastic effect would seem to render the OR3-KO mutant useless for our comparisons, we show later that this effect does not have a large impact on the development of the phage.

In summary, our testing of a number of OR3 and OR2 mutants provided two pairs of mutants whose comparison was expected to be instructive with regard to the role of Cro repression of PRM. The major difference between OR-WT and OR3-x3 is that the mutant retains only ∼12% of PRM repression by single-copy Cro (1.5/11.9). However, the OR3-x3 mutation increases basal PRM by ∼1.3-fold and slightly increases CI repression of PRM. We included the OR2/3-x4 mutant as an adjunct to this pair because of its greater defect in Cro repression of PRM. However, OR2/3-x4 has a larger effect on basal PRM activity (up 1.7-fold) and reduces CI-stimulated PRM activity by ∼25%.

The other pair of mutants, OR3-r1 and OR3-KO, differ in that OR3-KO retains only 15% of Cro repression of PRM (1.8/11.9), while Cro repression of PRM in OR3-r1 is normal. A caveat to the comparison of this pair is that translation of cI from the PRE mRNA is approximately ninefold more efficient in λ.OR3-KO compared with λ.OR3-r1 (340/38) (Fig. 3D).

The four OR mutants were therefore transferred into the genome of λ.b∷kan, hereafter referred to as λ.WT, which is an otherwise wild-type λ carrying an insertion of the kanamycin resistance gene into the nonessential b region. The resulting phages gave turbid plaques of normal appearance, and single lysogens were obtained without difficulty. We measured the ability of the OR mutant phages to complete lytic development after infection, to enter lysogeny after infection, and to be induced from lysogeny into lytic development.

Effects of the mutations on lytic and lysogenic development after infection

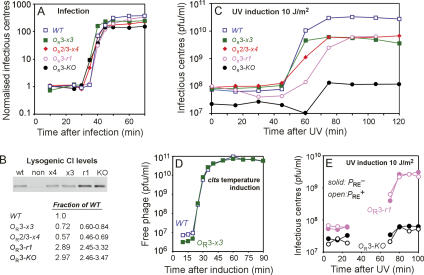

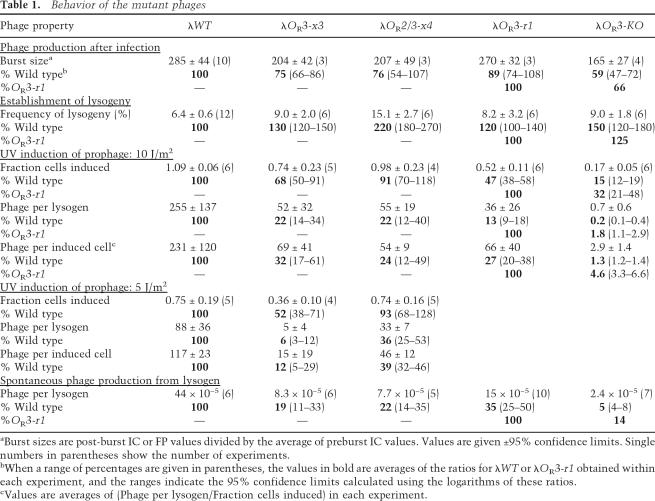

The OR mutations had only small effects on phage production after infection, confirming that Cro repression of PRM is not essential for lytic development. Single step burst curves showed that the timing of phage production was similar for the wild type and the mutants (an example is given in Fig. 4A). However, we found in repeated experiments that the average number of phages produced per infection (burst size) of the OR3-x3 mutant was slightly lower than wild type (75%) (Table 1). Similarly, the OR3-KO mutant burst size was 66% of λ.OR3-r1. The burst deficit did not increase with the further loss of Cro repression of PRM in the OR2/3-x4 mutant.

Figure 4.

Behavior of the OR mutant phages. (A) Phage production after infection. C600 cells were infected at a phage:bacterium ratio <0.01 with λWT or OR mutant phages and assayed for IC (lysing cells + FP) at various times. Values are normalized to preburst averages. (B) CI Western blotting of extracts from C600 nonlysogenic cells (non) or single C600 lysogens of λWT or OR mutant phages. (Note that there is a cross-reacting host band running just below CI). Values are CI levels relative to wild type (with 95% confidence limits) obtained by quantitation of the blots (n = 8 or 9). (C) Phage production after UV irradiation (10 J/m2) of C600 lysogens. (D) Temperature induction of λ.cIts and λ.cIts.OR3-x3 prophages. C600 lysogens were transferred from 30°C to 39°C and samples were assayed for FPs. (E) UV induction (as in C) of λ.OR3-r1 and λ.OR3-KO prophages and their PRE− derivatives. For the OR3-r1 PRE+ and OR3-r1 PRE− phages, respectively, 56% and 50% of lysogens were induced, producing 26 and 32 phage per irradiated lysogen. For the OR3-KO PRE+ and OR3-KO PRE− phages, respectively, 18% and 30% of lysogens were induced, producing on average 0.6 and 0.9 phage per irradiated lysogen.

Table 1.

Behavior of the mutant phages

aBurst sizes are post-burst IC or FP values divided by the average of preburst IC values. Values are given ±95% confidence limits. Single numbers in parentheses show the number of experiments.

bWhen a range of percentages are given in parentheses, the values in bold are averages of the ratios for λWT or λOR3-r1 obtained within each experiment, and the ranges indicate the 95% confidence limits calculated using the logarithms of these ratios.

cValues are averages of (Phage per lysogen/Fraction cells induced) in each experiment.

The proportion of infected cells that formed lysogens was slightly increased in the mutants with defective Cro repression of PRM. The frequency of lysogeny of the OR3-x3 mutant was 30% higher than the wild type and was 25% higher for λ.OR3-KO compared with λ.OR3-r1 (Table 1). A larger increase in lysogenization was seen with λ.OR2/3-x4.

These results are consistent with Cro repression of PRM causing a slight enhancement of lytic development and a slight decrease in lysogenization after infection, but alternative explanations are possible. In particular, for the OR3-KO mutant, these effects could be due to the large increase in the efficiency of CI production from PRE mRNA (Fig. 3D).

We were somewhat surprised that such a large increase in CI production from a transcript that is necessary for efficient lysogenization, did not have a larger impact. Presumably, other factors, such as integrase expression from PI, PAQ inhibition of Q, or cellular factors that determine whether CII is active at all, are limiting for lysogenization under our conditions.

Effects of the mutations on prophage induction

Because CI is expressed only from PRM in the lysogen, altered CI regulation of PRM changes the steady-state lysogenic concentration of CI, which can in turn affect the efficiency of prophage induction (Dodd et al. 2001; Michalowski et al. 2004). Western blotting of extracts of single lysogens (Fig. 4B) showed that the OR3-KO mutation or the OR3-r1 mutation caused a approximately threefold increase in lysogenic CI level, as expected due to lack of CI negative autoregulation. The OR3-x3 and the OR2/3-x4 mutant lysogens contained 72% and 57% of the wild-type CI level, respectively, consistent with their altered regulation of PRM by CI (Fig. 3A). On the basis of these measurements alone, one would expect the OR3-x3 and the OR2/3-x4 mutant lysogens to be somewhat more easily induced than wild type and the OR3-KO mutant lysogen to be induced poorly, like the OR3-r1 mutant (Dodd et al. 2001).

The OR mutants were strongly defective in prophage induction after UV (one experiment is shown in Fig. 4C). Table 1 summarizes the prophage induction behavior of λ.WT or the OR mutants after two different doses of UV and also in the absence of inducing treatments (spontaneous phage production). For the UV experiments, the fraction of lysogens that entered lytic development (that is, produced at least one phage) and the total number of phages produced per lysogenic cell, were measured, allowing calculation of the average number of phage produced per induced lysogen. After a UV dose of 10 J/m2, which was sufficient to induce all of the λ.WT lysogens, the λ.OR3-x3 and λ.OR2/3-x4 lysogens produced only about one-fifth of the number of phage produced by the λ.WT lysogen (Table 1). At the suboptimal dose of 5 J/m2, which induced only 75% of the λ.WT lysogens, the defect for λ.OR3-x3 was even more severe, with ∼16-fold fewer phage produced than wild type. The defect in the λ.OR3-x3 mutant at each dose was in part because a smaller fraction of lysogens was induced but was mainly due to fewer phages being produced in those cells that were induced. The defect in the λ.OR2/3-x4 lysogen was almost entirely due to a lowered burst size.

Cultures of recA+ λ lysogens contain low levels of phage even in the absence of added inducing stimuli, due to rare SOS-dependent transitions to lytic development. The relative numbers of phages per cell in cultures of different lysogenic strains is a measure of the relative rates of phage production (assuming the same rate of phage loss; e.g., by absorption). The OR3-x3 and OR2/3-x4 mutants showed a approximately fivefold lower spontaneous phage production than wild type (Table 1), similar to the 10-J/m2 UV defect.

As expected from its high lysogenic CI concentration, the λ.OR3-r1 lysogen was poorly induced by UV, with only half the cells producing phage at 10 J/m2. The defect in the OR3-KO mutant was much more severe, with phage production reduced 50-fold below that of λ.OR3-r1 (Table 1). As seen for the OR3-x3 and OR2/3-x4 mutants, it was the low number of phages produced per induced cell that was the prime cause of the λ OR3-KO defect. Spontaneous phage production was also reduced, though less severely, for λ.OR3-KO compared with λ.OR3-r1 (sevenfold).

If the prophage induction defect of λ.OR3-x3 relative to λ.WT is due to the loss of Cro repression of PRM and consequent overproduction of CI, then it should be relieved in the absence of CI activity. To test this, we replaced the cI+ gene of λ.WT and λ.OR3-x3 with the temperature-sensitive cI857 allele. Figure 4D shows that after induction of the cIts lysogens by raising the temperature to 39°C, there was very little difference in phage production for the OR3-x3 and wild-type lysogens (wild type and OR3-x3 gave 259 ± 71 and 231 ± 33 phage per induced cell, respectively; ±SD, n = 2). Clearly, the prophage induction defect caused by the OR3-x3 mutation is dependent on the presence of active CI.

We expected that the poor prophage induction of the OR3-KO mutant relative to the OR3-r1 mutant was caused by increased CI production due to lack of Cro repression of PRM in the OR3-KO mutant. However, the increased translation efficiency of cI from the PRE mRNA in the OR3-KO mutant (Fig. 3D) could conceivably increase CI levels after induction and contribute to the defect. Transcription from the PRE promoter does not normally affect phage production from a lysogen (Baek et al. 2003), but it might do so with a sixfold increase in its production of CI. If so, mutational inactivation of PRE should relieve the prophage induction defect of the OR3-KO mutant. We found that introduction of a PRE− mutation into the OR3-r1 and OR3-KO prophages had very little effect on phage production after a 10 J/m2 UV dose, with the OR3-KO PRE− mutant retaining the induction defect relative to OR3-r1 PRE− (Fig. 4E). Thus the defective prophage induction seen for the OR3-KO mutant is not due to increased CI expression from PRE mRNA.

Effects of loss of Cro repression of PRM on the CI–Cro switch

We tested the effect of the OR3-x3 mutation on the isolated CI–Cro bistable switch, first, to confirm the long-held assumption that Cro repression of PRM is necessary for the anti-immune state of the switch and, second, to examine the kinetics of CI activity after UV induction in the absence of other regulatory λ genes. We chose the OR3-x3 mutation as the best comparison with wild-type.

We measured PR transcription using chromosomal cIts.PRM.PR.cro.lacZ reporters that were OR3+cro+ or carried the OR3-x3 and/or cro− mutations (Fig. 5A). The reporters carry OL, which is necessary for proper regulation of PR and PRM (Dodd et al. 2004), and include the rexAB genes, which have no known role in CI–Cro regulation. After growth at 30°C, all four strains formed very pale blue colonies on Xgal plates, indicative of the immune state in which CI is produced and represses PR to give a very low lacZ expression. At 39°C all the strains formed dark blue colonies, due to inactivation of CIts and derepression of PR. When these dark blue colonies were restreaked at 30°C, most of the new colonies from the OR3+cro+ strain were dark blue, displaying a persistent lack of CI repression of PR that is characteristic of the anti-immune state. In contrast, the restreaked colonies from the cro− or OR3-x3 strains were pale blue and had re-established the immune state. These results show that Cro repression of PRM is necessary for the anti-immune state of the CI–Cro switch.

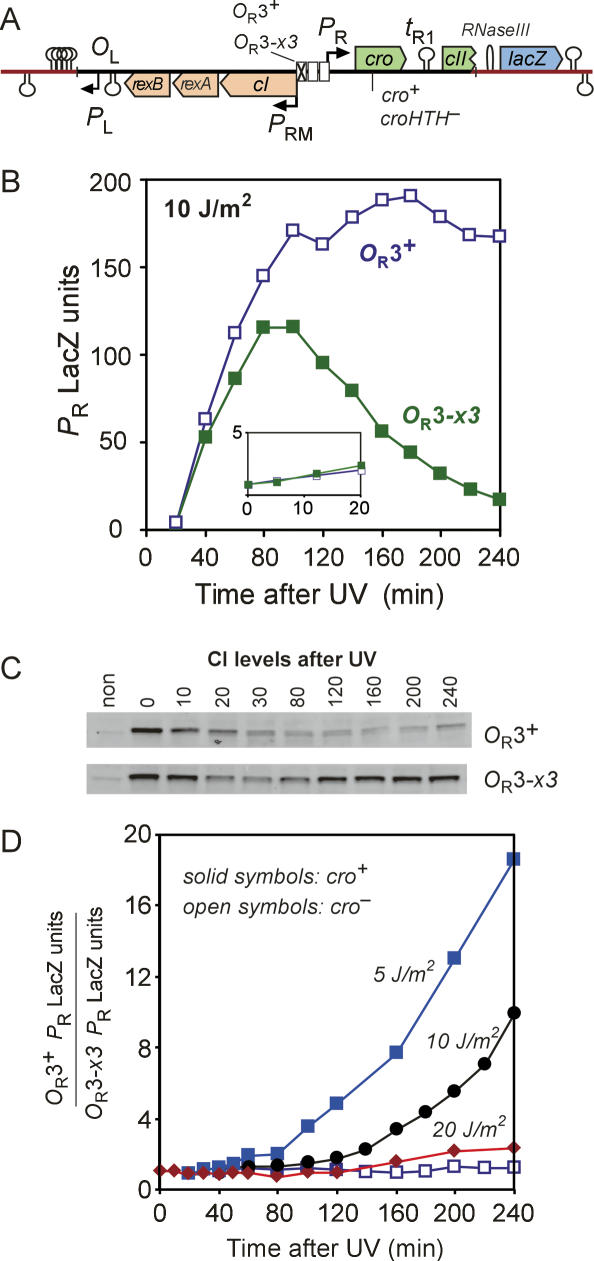

Figure 5.

Effect of the OR3-x3 mutation on UV induction of the CI–Cro switch. (A) Structure of the chromosomally integrated cI.PRM.PR.cro.lacZ reporter constructs. LacZ activity from PR (B), and Western blotting of CI (C) following 10 J/m2 UV treatment of the cro+ reporters. (D) Relative LacZ activities in the OR3+ and OR3-x3 reporters after different UV doses. The strains carrying the croHTH− mutation showed that the OR3-x3 mutation made no difference to PR LacZ activity in the absence of Cro (open symbols, 10 J/m2 UV treatment).

To examine the kinetics of UV induction of the CI–Cro switch, we constructed cI+ versions of the above reporters. Figure 5B shows a time course of LacZ production from PR after a 10 J/m2 UV dose in the OR3+cro+ and OR3-x3 cro+ reporters. Figure 5C shows CI Western blotting from the same experiment. The two strains showed similar behavior in the early phase of induction, with some derepression of PR early after UV treatment (Fig. 5B, inset), before a sharp increase in PR activity after 20 min, in line with the substantial drop in CI levels evident in the Western blots.

In the later stages, the two strains behaved quite differently. In the OR3+cro+ reporter, CI levels remained low for up to 4 h after induction, while LacZ levels continued to increase, though more slowly at later times, until reaching a maximum ∼2 h after induction. The reduction in slope of the OR3+cro+ LacZ curve with time is due in part to the accumulation of Cro, which partially represses PR, but also to the approach of LacZ accumulation to steady state, where the rate of LacZ production from PR is balanced by the rate of LacZ dilution due to cell growth (note that LacZ protein is stable and LacZ units are normalized to cell mass). The maximal activity of this PR reporter is expected to be ∼180–220 U, reduced from the ∼1150 U seen for PR in Figure 3,B and C, both by Cro repression (1.6-fold to twofold repression) (Svenningsen et al. 2005; A. Palmer, unpubl.) and by termination at tR1 (approximately threefold reduction) (Fig. 5A; A. Palmer, unpubl.). Thus, PR remained highly active in most cells of the OR3+cro+ strain for the duration of the experiment. In the OR3-x3 cro+ reporter, the increase in LacZ units slowed in comparison with OR3+cro+ soon after 40 min and LacZ accumulation halted after 80 min, indicating that PR is substantially repressed at this point, consistent with the increased CI levels evident from the Western. After 100 min, LacZ activity slowly reduced, presumably as a result of dilution due to continued cell growth, indicating that PR is now strongly repressed and no new LacZ protein is being made. These results show that in the absence of Cro repression of PRM, CI activity becomes re-established after UV induction, reducing and eventually fully repressing PR activity.

The magnitude of the improvement in PR activity due to Cro repression of PRM depends on the UV dose. Figure 5D shows the relative LacZ levels produced from PR in the presence compared with the absence of Cro repression of PRM at three UV doses. At the high dose of 20 J/m2, Cro repression of PRM has relatively little effect on PR expression over the time of the experiment, presumably because RecA activity persists sufficiently to inactivate any CI made from PRM. At 5 J/m2, the Cro/PRM effect is two- to threefold stronger than that seen at 10 J/m2. We expect that at low doses a larger fraction of CI remains after RecA activity has ended and can more readily restore CI levels by activation of PRM unless the promoter is repressed by Cro.

We expect that Cro repression of PRM is particularly important in prophage induction, in contrast to infection, because there will often be some activation of PRM due to residual CI that has either escaped RecA inactivation or is produced from PRM mRNA after RecA has disappeared. Thus, for Cro to impact on prophage induction, it must be able to repress PRM in the presence of CI. To confirm this expected activity of Cro, we supplied varying levels of CI in trans to the lacZ.PRM.PR.cro reporter of Figure 1B to see whether Cro produced in cis from PR could reduce PRM activity in the presence of CI. Figure 6 shows that in the absence of Cro (the Δcro reporter), increasing IPTG induction of CI expression first activates then represses PRM, as seen previously (Dodd et al. 2001).The substantial reductions in PRM activity seen in the presence of Cro at lower CI concentrations demonstrate that Cro can indeed repress PRM in the presence of CI. The dashed line in Figure 6 shows how the activity of PR, and thus the expression of Cro, is repressed by the increasing CI levels (Dodd et al. 2004). Remarkably, even when the single-copy cro gene is substantially repressed by CI, the Cro protein produced can make a large difference to PRM activity. This result supports that idea that Cro expressed from a partially derepressed prophage can strongly inhibit CI production.

Figure 6.

Repression of PRM by single-copy cro in cis in the presence of CI. The cro+ curve was obtained using the PRM.lacZ transcriptional reporter in Figure 1B. The reporter for the Δcro curve is the same except that the cro gene is truncated at the +43 position of PR. CI was supplied with an IPTG-inducible expression plasmid system, with 150 μM IPTG producing a PRM response equivalent to that at lysogenic CI levels (Dodd et al. 2001). Errors are 95% confidence intervals. The dashed line shows the response of a PR.lacZ (Δcro) reporter to CI (LacZ values divided by 5) (Dodd et al. 2004).

Discussion

The role of Cro repression of PRM after infection

Our results show that defective Cro repression of PRM does not dramatically affect lytic development or the establishment of lysogeny after infection by λ phage. The OR3-x3 mutation caused an ∼25% decrease in burst size and an ∼25% increase in lysogenization after infection, compared with wild type. A similar decrease in burst size (33%) and increase in lysogenization (25%) was seen with the OR3-KO mutation compared with the OR3-r1 mutant. Although these slight increases in lysogenization and slight decreases in phage production are consistent with a lack of Cro repression of PRM altering the balance toward lysogenic development after infection, it is not possible to exclude other causes of these effects. The effect of the OR3-x3 mutation might be due to the slightly increased basal PRM activity in this mutant (30% up compared with wild type), which could increase CI levels early in infection. Although there is no difference in basal PRM activity between the OR3-r1 and OR3-KO mutants, the burst size and lysogenization changes in the λ.OR3-KO mutant may be due to the mutant’s increased CI translation from PRE mRNA, which would be expected to favor lysogeny.

The role of Cro repression of PRM in prophage induction

In contrast, the effects of the OR3-x3 and OR3-KO mutations on the transition from lysogeny to lytic development are substantial and can be directly attributed to the loss of Cro repression of PRM. At a dose (10 J/m2) that induced all λ.WT lysogens, phage production from λ.OR3-x3 lysogens was almost fivefold lower than wild type. Phage production from λ.OR3-x3 lysogens was 16-fold lower than wild type at the lower dose of 5 J/m2, which induced 75% of λ.WT lysogens. At the 10 J/m2 dose, 50% of λ.OR3-r1 lysogens were induced and phage production from the λ.OR3-KO lysogens was 55-fold lower than for λ.OR3-r1. These effects are much stronger than can be explained by the other effects of the mutations. The OR3-x3 mutation had a small effect on CI regulation of PRM, but this should, if anything, assist induction, as it lowers the lysogenic CI concentration. The slight increase in basal PRM activity in OR3-x3 (30%), which would tend to inhibit prophage induction, is likely to be insignificant compared with the eightfold increase in PRM activity due to loss of Cro repression. Apart from Cro repression of PRM, the only difference between λ.OR3-KO and λ.OR3-r1 is the increased cI translation from PRE mRNA in the OR3-KO mutant. However, we showed that this difference is not important in induction because inactivating PRE had no impact on prophage induction in these mutants. Thus, our results strongly support the Johnson-Ptashne conjecture (Johnson et al. 1981) that Cro repression of PRM is critical in prophage induction.

Comparisons with other studies

Our conclusions differ from two recent studies. Svenningsen et al. (2005) observed that the presence of the cro+ gene on chromosomal cI857.PRM.PR.cro.lacZ reporters did not increase PR activity at temperatures that partially released PR from repression by the temperature-sensitive mutant CI857 protein. However, the cro− mutation used to remove Cro repression of PRM also removes Cro repression of PR, which would tend to mask any decreased PR activity caused by higher CI expression in this mutant. We believe that our experiments with Cro operator mutants, and with a transient SOS signal inactivating wild-type CI protein, more truly reflect the role of Cro repression of PRM in λ prophage induction.

Atsumi and Little (2006) concluded that Cro repression of PRM provides only a modulatory role in prophage induction. In their λlacIdim phages, the cro gene was replaced by the gene for a dimeric lac repressor, and lac operators were inserted at PR and PL to mimic Cro’s repression of the lytic promoters. The lac repressor was unable to directly repress PRM as no lac operator was inserted there. A larger UV dose was required to give half-maximal phage production from lysogens of the most wild-type-like of the variants, λAWCF, compared with the parental phage, λJL351. However, we believe that it is not possible to confidently attribute the induction defect in these λlacIdim phages to a lack of repression of PRM by LacI because it is not clear that this is the only regulatory difference between the λlacIdim phages and λJL351. Specifically, the insertion of lac operators just downstream from the PL and PR promoters may alter the basal activities of these promoters, and their control by LacI is likely to differ from normal Cro regulation. Thus, the expression of the λ lytic genes may well be different in the λlacIdim phages and λJL351. In addition, although Atsumi and Little showed that PRM in λAWCF is not directly repressed by lac repressor, their data indicated that the presence of lac repressor interferes with CI activation of PRM. As CI and lac repressors are both present during prophage induction, this effect may partially substitute for Cro repression of PRM. Also, the λlacIdim phages and λJL351 carry a mutation in the cI gene that increases the sensitivity of the prophage to UV induction, probably acting by reducing lysogenic CI levels. This would most likely reduce the impact of the loss of Cro repression of PRM in comparison with wild-type λ. Thus, we believe that our results provide a more valid measurement of the importance of Cro repression of PRM in λ prophage induction.

Cro repression of PRM prevents recovery of CI

Our results indicate that Cro’s action at PRM is necessary primarily to prevent recovery of CI levels rather than affecting the rate at which CI levels fall after UV treatment. Up until ∼20 min after a 10 J/m2 UV treatment, we saw no difference in the induction of PR activity in the OR3+ and OR3-x3 CI–Cro switch reporters (Fig. 5B). Also, direct measurements indicated that CI fell to similar levels in the two strains by 20 min (Fig. 5C). Although there is some PR activity in the early stages of induction, we imagine that this produces insufficient Cro to affect PRM significantly. Even if Cro does begin to repress PRM before 20 min, there will be a delay before this repression impacts on CI production because of the time required for the existing cI mRNA to degrade. However, as Cro accumulates and RecA activity wanes due to repair of the UV damage, Cro’s ability to repress PRM would have a more significant impact on CI levels. Accordingly, the PR activity and CI levels in the OR3+ and OR3-x3 CI–Cro switch reporters diverge 20 min after UV. In the OR3+ strain, a low CI level and a lack of CI repression of PR were maintained in at least the vast majority of cells up until 240 min after UV. In contrast, a gradual increase in repression of PR was apparent after 20 min in the induction of the OR3-x3 CI–Cro switch, with re-establishment of PR repression and lysogenic CI levels complete by 80–120 min. Although the timing of this re-establishment of CI in the switch reporter seems slow in the context of the ∼50 min required for phage production after UV, we expect that CI recovery would occur more quickly after UV induction of a prophage due to replication of the λ genome and consequent increased number of cI genes.

The whole-phage studies also support the idea that the main function of Cro repression of PRM is to prevent recovery of CI levels after prophage induction. The defect in PRM repression by Cro strongly reduced the number of phages produced per induced cell (threefold, eightfold, and 22-fold reductions; λ.WT vs. OR3-x3 at 10 J/m2 UV and at 5 J/m2 UV, and λ.OR3-r1 vs. OR3-KO at 10 J/m2, respectively) (Table 1) but had less of an effect on the fraction of cells induced (1.3-fold, twofold, and threefold reductions for the same comparisons) (Table 1). Thus, Cro repression of PRM does not so much affect the probability of an irreversible commitment to lytic development, but more affects the execution of lytic development subsequent to that commitment. The recovery of CI levels seen in the absence of Cro repression of PRM therefore appears to have a significant inhibitory effect on the efficiency of lytic development. In fact, the reduction in the fraction of induced cells in the OR3-x3 and OR3-KO mutants may in part be due to CI recovery being able to block lytic development completely in some cells.

These results contradict the view that the UV dose and Cro repression of PRM only affect the probability of crossing some decisive induction threshold and do not affect the execution of lytic development after that decision (Atsumi and Little 2006). If this view were correct, then one would expect the UV dose and Cro repression of PRM to have large effects on the fraction of cells induced and small effects on the number of phage produced per induced lysogen, whereas we saw the reverse. Even λ.WT lysogens had a twofold reduced number of phages produced per induced cell at 5 J/m2 compared with 10 J/m2 (Table 1), showing that even when Cro repression of PRM is intact, there can be substantial inhibition of lytic development after induction. Thus, Cro repression of PRM significantly improves the execution of lytic development after prophage induction but does not make it perfect.

Concluding remarks

A stable immune state of the CI–Cro regulatory circuit is necessary for stable lysogeny, but a stable anti-immune state is clearly not necessary for λ lytic development itself. Instead, the function of the bistability that results from Cro’s strong repression of PRM is to improve the transition out of lysogeny into lytic development. We imagine that the selective advantage of more efficient prophage induction would easily be sufficient to drive the evolution of a fully bistable system from a monostable one, in which Cro repression of PRM was weak or absent. Studies of other temperate phages support the idea that λ’s stable anti-immune state is not just an accident of evolution. To our knowledge, all temperate phages, including many unrelated to λ, have some kind of anti-immunity factor, often a small Cro-like DNA-binding protein, and it has been reported in many cases that the immunity/anti-immunity regulatory circuit of these phages is bistable. Thus, it seems that there is selective pressure to make the anti-immunity regulation strong enough to preclude the immune state. We expect that this bistability serves similar functions in these phages as in λ but that the impact on prophage induction and on lytic development after infection may vary, depending on features such as the mechanism of induction, the length of the lytic cycle and the regulation of the immunity factor.

By its repression of the promoters at OR and OL, Cro antagonizes the production of both major anti-lytic regulators, CI and CII. Cro repression of PR (and PL) is needed after infection to prevent CII overexpression during lytic development. As we have shown, during lytic development after prophage induction, Cro repression of PRM is important to prevent CI resurgence. It seems likely that Cro’s anti-CII action is also important after prophage induction, although this has not been tested directly. It would be interesting to see whether the defective prophage induction of λ.OR3-x3 is worsened by a cro− mutation and in a cII-dependent manner.

The results presented here and previously (Dodd et al. 2001, 2004) show that OR3, rather than being the “third wheel” on the OR bicycle, plays dual critical roles in λ’s transition from lysogeny to lytic development. First, OR3 enables CI to repress PRM and thus maintain a lysogenic level of CI that is low enough to be effectively removed by RecA upon induction of the SOS system. Second, OR3 allows Cro to efficiently repress PRM and prevent the recovery of CI levels that would otherwise impede or even halt lytic development. The response of the OR3-KO mutant to a UV dose that induces every λ.WT lysogen (10 J/m2) (Table 1) shows that these activities of OR3 combine to provide a 500-fold improvement in phage production.

Materials and methods

Strains and mutations

E4300 [= NK7049 (ΔlacIZYA)X74 galOP308 StrR Su−] (Simons et al. 1987) was used for reporter assays, and C600 was used for phage experiments. Mutations were introduced by PCR-based methods. The OR2, OR3, and PR− mutations are shown in Figure 2A. The croΔ21 mutation removes positions 38109–38129 = Cro(G24-I30)Δ. The croHTH− mutation changes codons 26–28 TATCAAAGC (YGS) to TACGAACGC (YER). The cI857 change is 37742C → T. The PRE− mutation is a change of the −10 AAGTAT → GCATGC. All lysogens were confirmed as single copy (Powell et al. 1994).

Phage constructions

Mutations in the cI-OR-cro-cII region to be transferred to λ were constructed in pAP831 and crossed onto λ.b∷kan.imm434 by in vivo recombination, as described previously for λ.imm434 (Dodd et al. 2001). λ.b∷kan.imm434 was obtained by crossing the b∷kan insertion from pJWL464 onto λ.imm434 (Supplemental Material; Michalowski et al. 2004). λ b∷kan is referred to as λWT, and all OR mutant phage carry the b∷kan insertion.

Reporter strains and assays

The lacZ reporters strains used in Figures 1, 2, 3 were constructed by cloning λ DNA into pTL61T (Linn and St. Pierre 1990) for transcriptional fusions, or pRS414 (Simons et al. 1987) for translational fusions, recombining these fusions onto λRS45ΔYAOL or λRS45ΔYA and making single-copy lysogens of these phages in E4300, as described previously (Dodd et al. 2001). Details are given in the Supplemental Material.

Cro or CI were expressed in the reporter strains from plac+ on plasmids pZE15cro or pZC320cI (Dodd et al. 2001), controlled by lac repressor from pUHA1 (Lutz and Bujard 1997) and IPTG. Cells were cultured in LB (+antibiotics) and assayed using a kinetic microtiter plate-based LacZ assay (Dodd et al. 2001).

To make the CI–Cro switch reporters, λ sequence extending from the PL leader to within the cII gene was inserted into the plasmid vector pIT-SLlacZY, which was then integrated at λattB in the chromosome of E4300. pIT-SLlacZY is based on the CRIM-integrating plasmid system (see Supplemental Material; Haldimann and Wanner 2001). The cI857, croHTH−, and OR3-x3 alleles were introduced by resection.

Western blotting

Single C600 lysogens were isolated and the level of CI protein in the strains was quantitated by Western blotting as described previously (Dodd et al. 2001), except that cells from ∼1 mL of log phase culture (final volumes were adjusted to give a constant OD600) were disrupted with 40 μL of B-Per reagent (Pierce) containing 0.25 U/μL Benzonase (Novagen) and 0.2 μg/μL lysozyme (Sigma). Detection was with a Cy5-labeled goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (GE Healthcare), and blots were quantitated with a GE Typhoon imager.

Single step burst curves and frequency of lysogeny assays

For infection of C600 hosts, log phase cultures in LBM (LB, 10 mM MgSO4) plus 0.2% maltose were concentrated ∼10-fold by centrifugation at 37°C and infected with prewarmed phage at a multiplicity of addition <0.01 for 10 min at 37°C (adsorption was 95%–99% efficient). The infection was diluted at least ∼100-fold in LBM and incubated with shaking at 37°C.

To follow the phage burst, aliquots were removed at various times and immediately diluted and plated for infectious centers (IC) with C600 indicator bacteria (in LBM) and 3 mL of molten top agar (0.7% agar, 10 mM MgSO4) on TB plates (1% Bacto-tryptone, 0.5% NaCl, 1.5% Bacto-agar [Difco]).

To measure the frequency of lysogeny, an aliquot taken 15 min after initial infection was immediately diluted and plated on C600 indicator for IC or for free phage (FP; treated with chloroform to kill bacteria before being plated with indicator). After 25 min, the infection was plated with 3 mL of molten top agar onto LB plates containing 20 μg/mL kanamycin, to measure the number of lysogens formed. Total phage added was experimentally equated to the sum of the number of IC and lysogens. The total number of infections was the total phage added minus the FP. The frequency of lysogeny was the (number of lysogens divided by the total number of infections) × 100.

UV and temperature induction of prophage

For UV induction, log phase cultures of C600 lysogens in LB (at cell density of ∼1 × 108 colony-forming units [cfu]/mL) were harvested by centrifugation at 4°C, resuspended neat in M9 salts (Miller 1972) and 5 mL (+1 μL of 10% Tween20 for wetting) placed in a sterile 8.5-cm plastic Petri dish. Prior to UV exposure, an aliquot was plated on LB plates to assay cell density. After irradiation with a germicidal UV lamp under yellow lighting at 37°C, the culture was diluted ∼1/5 into LB and incubated at 37°C with shaking. At a number of time points, aliquots were diluted and plated with indicator for IC and/or FP.

Untreated λ lysogens plated with indicator bacteria were found to give plaques (very small in size) at a rate of ∼6%–15%, depending on the mutant. Therefore, prior to UV treatment the culture was diluted and plated with indicator to measure the level of uninduced lysogens giving plaques (plaque-forming lysogens). The number of induced lysogens was the preburst IC minus the number of plaque-forming lysogens.

The fraction of cells induced was the number of induced lysogens as a fraction of the lysogens present. The number of phage produced per lysogen was the FP post-burst divided by the lysogens present. The number of phage per induced cell was the average FP post-burst divided by the number of induced lysogens.

Spontaneous induction was measured by plating dilutions of log phase cultures of C600 lysogens onto TB plates for colony-forming units, and assaying the culture supernatants (following centrifugation at 4°C) for FP.

For the experiments shown in Figure 4D, log-phase cultures of cIts lysogens in LB at 30°C were temperature-induced by diluting 1000-fold into LB prewarmed to 39°C and incubating at 39°C with shaking. At early time points, aliquots were diluted and plated immediately with indicator to measure preburst IC. To follow the burst curve, aliquots taken at different times were treated with chloroform before being diluted and plated with indicator to measure the number of FP present.

UV induction of the λ switch reporter

The λ switch reporter strains were treated with UV as described above. After 1/3–1/5 dilution into LB, cultures were grown at 37°C with shaking and were diluted to maintain cells in log phase growth. Aliquots taken at various times were collected on ice and analyzed by LacZ assay and CI Western blotting.

Acknowledgments

We thank John Little for pJWL464, Adam Palmer for plasmids containing PR− and PRE− mutations, and members of the Shearwin laboratory for discussions and comments on the manuscript. This work was funded by the US National Institutes of Health (GM062976) and initially by the Australian Research Council (A09943087). This paper is dedicated to Dale Kaiser, Frank Harold, and Dave Hogness, whose influence on the post-graduate education of J.B.E. underpinned the pursuit of the research presented.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1584907

References

- Adhya S., Gottesman M., Gottesman M. Promoter occlusion: Transcription through a promoter may inhibit its activity. Cell. 1982;29:939–944. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90456-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atsumi S., Little J.W., Little J.W. Role of the lytic repressor in prophage induction of phage λ as analyzed by a module-replacement approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006;103:4558–4563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511117103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek K., Svenningsen S., Eisen H., Sneppen K., Brown S., Svenningsen S., Eisen H., Sneppen K., Brown S., Eisen H., Sneppen K., Brown S., Sneppen K., Brown S., Brown S. Single-cell analysis of λ immunity regulation. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;334:363–372. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailone A., Levine A., Devoret R., Levine A., Devoret R., Devoret R. Inactivation of prophage λ repressor in vivo. J. Mol. Biol. 1979;131:553–572. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Court D.L., Oppenheim A.B., Adhya S.L., Oppenheim A.B., Adhya S.L., Adhya S.L. A new look at bacteriophage λ genetic networks. J. Bacteriol. 2007;189:298–304. doi: 10.1128/JB.01215-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling P.J., Holt J.M., Ackers G.K., Holt J.M., Ackers G.K., Ackers G.K. Coupled energetics of λ cro repressor self-assembly and site-specific DNA operator binding II: Cooperative interactions of cro dimers. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;302:625–638. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd I.B., Perkins A.J., Tsemitsidis D., Egan J.B., Perkins A.J., Tsemitsidis D., Egan J.B., Tsemitsidis D., Egan J.B., Egan J.B. Octamerization of λ CI repressor is needed for effective repression of PRM and efficient switching from lysogeny. Genes & Dev. 2001;15:3013–3022. doi: 10.1101/gad.937301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd I.B., Shearwin K.E., Perkins A.J., Burr T., Hochschild A., Egan J.B., Shearwin K.E., Perkins A.J., Burr T., Hochschild A., Egan J.B., Perkins A.J., Burr T., Hochschild A., Egan J.B., Burr T., Hochschild A., Egan J.B., Hochschild A., Egan J.B., Egan J.B. Cooperativity in long-range gene regulation by the λ CI repressor. Genes & Dev. 2004;18:344–354. doi: 10.1101/gad.1167904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen H., Brachet P., Pereira da Silva L., Jacob F., Brachet P., Pereira da Silva L., Jacob F., Pereira da Silva L., Jacob F., Jacob F. Regulation of repressor expression in λ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1970;66:855–862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.66.3.855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkmanis A., Maltzman W., Mellon P., Skalka A., Echols H., Maltzman W., Mellon P., Skalka A., Echols H., Mellon P., Skalka A., Echols H., Skalka A., Echols H., Echols H. The essential role of the cro gene in lytic development by bacteriophage λ. Virology. 1977;81:352–362. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(77)90151-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldimann A., Wanner B.L., Wanner B.L. Conditional-replication, integration, excision, and retrieval plasmid-host systems for gene structure-function studies of bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183:6384–6393. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.21.6384-6393.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herskowitz I., Hagen D., Hagen D. The lysis-lysogeny decision of phage λ: Explicit programming and responsiveness. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1980;14:399–445. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.14.120180.002151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A.D. 1980. “Mechanism of action of the λ cro protein”. Ph.D. thesis, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A., Meyer B.J., Ptashne M., Meyer B.J., Ptashne M., Ptashne M. Mechanism of action of the cro protein of bacteriophage λ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1978;75:1783–1787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.4.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A.D., Poteete A.R., Lauer G., Sauer R.T., Ackers G.K., Ptashne M., Poteete A.R., Lauer G., Sauer R.T., Ackers G.K., Ptashne M., Lauer G., Sauer R.T., Ackers G.K., Ptashne M., Sauer R.T., Ackers G.K., Ptashne M., Ackers G.K., Ptashne M., Ptashne M. λ Repressor and cro—Components of an efficient molecular switch. Nature. 1981;294:217–223. doi: 10.1038/294217a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalionis B., Dodd I.B., Egan J.B., Dodd I.B., Egan J.B., Egan J.B. Control of gene expression in the P2-related template coliphages. III. DNA sequence of the major control region of phage 186. J. Mol. Biol. 1986;191:199–209. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90257-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffman S.A. Control circuits for determination and transdetermination. Science. 1973;181:310–318. doi: 10.1126/science.181.4097.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobiler O., Rokney A., Friedman N., Court D.L., Stavans J., Oppenheim A.B., Rokney A., Friedman N., Court D.L., Stavans J., Oppenheim A.B., Friedman N., Court D.L., Stavans J., Oppenheim A.B., Court D.L., Stavans J., Oppenheim A.B., Stavans J., Oppenheim A.B., Oppenheim A.B. Quantitative kinetic analysis of the bacteriophage λ genetic network. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005;102:4470–4475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500670102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krinke L., Mahoney M., Wulff D.L., Mahoney M., Wulff D.L., Wulff D.L. The role of the OOP antisense RNA in coliphage λ development. Mol. Microbiol. 1991;5:1265–1272. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin B. Genes VII. Oxford University Press; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Linn T., St Pierre R., St Pierre R. Improved vector system for constructing transcriptional fusions that ensures independent translation of lacZ. J. Bacteriol. 1990;172:1077–1084. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.1077-1084.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little J.W. Autodigestion of lexA and phage λ repressors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1984;81:1375–1379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.5.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz R., Bujard H., Bujard H. Independent and tight regulation of transcriptional units in Escherichia coli via the LacR/O, the TetR/O and AraC/I1-I2 regulatory elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:1203–1210. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.6.1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer B.J., Maurer R., Ptashne M., Maurer R., Ptashne M., Ptashne M. Gene regulation at the right operator (OR) of bacteriophage λ. II. OR1, OR2, and OR3: Their roles in mediating the effects of repressor and cro. J. Mol. Biol. 1980;139:163–194. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(80)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michalowski C.B., Short M.D., Little J.W., Short M.D., Little J.W., Little J.W. Sequence tolerance of the phage λ PRM promoter: Implications for evolution of gene regulatory circuitry. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186:7988–7999. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.23.7988-7999.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J.H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, New York: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Murray N.E., Gann A., Gann A. What has phage λ ever done for us? Curr. Biol. 2007;17:R305–R312. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer Z., Calef E., Calef E. Immunity phase-shift in defective lysogens: Non-mutational hereditary change of early regulation of λ prophage. J. Mol. Biol. 1970;51:1–13. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(70)90265-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell B.S., Rivas M.P., Court D.L., Nakamura Y., Turnbough C.L., Rivas M.P., Court D.L., Nakamura Y., Turnbough C.L., Court D.L., Nakamura Y., Turnbough C.L., Nakamura Y., Turnbough C.L., Turnbough C.L. Rapid confirmation of single copy λ prophage integration by PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:5765–5766. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.25.5765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptashne M. A genetic wwitch: Phage λ revisited. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sarai A., Takeda Y., Takeda Y. λ repressor recognizes the approximately twofold symmetric half-operator sequences asymmetrically. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1989;86:6513–6517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.17.6513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons R.W., Houman F., Kleckner N., Houman F., Kleckner N., Kleckner N. Improved single and multicopy lac-based cloning vectors for protein and operon fusions. Gene. 1987;53:85–96. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svenningsen S.L., Costantino N., Court D.L., Adhya S., Costantino N., Court D.L., Adhya S., Court D.L., Adhya S., Adhya S. On the role of Cro in λ prophage induction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005;102:4465–4469. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409839102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda Y. Specific repression of in vitro transcription by the Cro repressor of bacteriophage λ. J. Mol. Biol. 1979;127:177–189. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(79)90238-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda Y., Sarai A., Rivera V.M., Sarai A., Rivera V.M., Rivera V.M. Analysis of the sequence-specific interactions between Cro repressor and operator DNA by systematic base substitution experiments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1989;86:439–443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toman Z., Dambly-Chaudiere C., Tenenbaum L., Radman M., Dambly-Chaudiere C., Tenenbaum L., Radman M., Tenenbaum L., Radman M., Radman M. A system for detection of genetic and epigenetic alterations in Escherichia coli induced by DNA-damaging agents. J. Mol. Biol. 1985;186:97–105. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90260-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]