Abstract

Objective

To determine if treatment of BV decrease the incidence of sexually transmitted diseases.

Study Design

Women with asymptomatic BV were studied prospectively to determine the effect of treatment of BV for the prevention of STD. Women were randomized to observation or treatment and prophylaxis with intravaginal metronidazole gel. Women were screened monthly for STDs.

Results

Women randomized to metronidazole gel had a significantly longer time to development of STD compared to women in the observation group (p=0.02). The 6-month STD rate was 1.58/person-year (95% CI 1.29, 1.87) for women in the metronidazole gel group versus 2.29/person-year (95% CI 1.95, 2.63) for women in the observational group. The difference in STD rates was driven by a significant difference in the number of chlamydial infections (0.013).

Conclusion

Treatment and twice-weekly prophylactic use of intravaginal metronidazole gel resulted in significantly fewer cases of chlamydia.

Keywords: Bacterial vaginosis, STD, metronidazole, chlamydia

Introduction

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is the most common form of vaginitis worldwide. It is characterized by a shift in the microbial flora resulting in marked decreases in protective lactobacilli and increases in anaerobes and Gardnerella vaginalis 1 . Bacterial vaginosis has been consistently associated with adverse outcomes including acquisition of HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) in cross-sectional studies and in some prospective studies 2-4. Although multiple factors may be involved, hydrogen-peroxide producing lactobacilli have been shown in-vitro to inhibit the growth of bacteria as well as HIV and their absence in women with BV is likely to be a biological risk factor for STD/HIV acquisition 5, 6. There are two published studies on the treatment of STDs including BV to prevent HIV acquisition 7, 8 , however, there are no published studies examining the effect of BV treatment on acquisition of other STDs. Treatment of symptomatic BV is necessary to alleviate the bothersome symptoms. However, treatment of asymptomatic BV is currently not recommended except in special circumstances 9. Therefore, we were able to conduct a prospective study on the treatment of asymptomatic BV as a means of preventing STDs.

Materials and Methods

Women attending the Jefferson County Department of Health (JCDH) STD Clinic in Birmingham, AL were invited to participate in this prospective study. Approval for the study was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards (IRB) of the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) and the JCDH Department of Health. Written consent was obtained from all participants and human experimentation guidelines of the UAB IRB were followed in the conduct of this clinical research. Women were screened for vaginal infections and STDs as part of their routine clinic visit. Women with asymptomatic BV, defined by Nugent criteria and lack of report of vaginal odor and/or discharge upon direct questioning were invited to participate in the trial. Women with symptomatic BV (vaginal odor and/or discharge) were not eligible to participate since they required therapy to alleviate their symptoms. Women were randomized to receive treatment for BV versus observation alone since an appropriate placebo was not available for use. A computer generated randomization scheme was prepared with random blocks of 2 or 4 which was provided to the study pharmacist. Treatment assignments were maintained by sealed envelopes until randomization. Treatment consisted of intravaginal metronidazole gel at bedtime for 5 days, followed by twice weekly use for 6 months to prevent recurrences10. Women were followed monthly for the first six months, then every three months for a total of one year. No treatment was administered during the final six months unless clinically indicated for symptomatic BV. Screening for STDs, including gonorrhea, chlamydia, trichomonas and herpes simplex virus type 2, was performed at each visit. Pelvic inflammatory disease was based on a clinical diagnosis of complaints of abdominal pain and adnexal tenderness and/or cervical motion tenderness on examination. Incident HSV-2 infection was defined as a conversion from a negative to a positive serological result. Women with an STD at baseline were ineligible for the study with the exception of women who were seropositive for HSV-2. Women who developed an STD or a vaginal yeast infection during the course of the study (with the exception of asymptomatic HSV) were treated appropriately and continued in the study. Women who developed symptomatic BV during the course of the study were re- treated with a 5-day regimen of metronidazole gel and then asked to resume prophylactic twice-weekly therapy.

Microbiological Methods

Vaginal fluid pH, microscopy, and “whiff test were performed as previously described 1 . Vaginal Gram stains were interpreted according to the method of Nugent et al 11. Scores of 0-3 were considered normal, 4-6 as evidence of intermediate flora and 7-10 as BV. Urine specimens were tested for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis using nucleic acid amplification techniques (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL and Gen-Probe, San Diego, CA). The presence of Trichomonas vaginalis was detected using the InPouch TV culture technique (BioMed Diagnostics, Inc, White City, OR). Type specific serology for HSV was performed using at type–specific ELISA using recombinant gG2 for HSV-2 (HerpeSelect, Focus Technologies, Herndon, VA).

Statistical Analysis

Sample Size

Sample size estimates were derived to demonstrate a difference in STD-free survival between the two groups with 80% power, 5% alpha based on a two-sided log rank test. Assumptions included that 60% of women in the observation group would not develop and STD after six months of follow-up compared to 75% in the treatment group and a drop-out rate of 10% per month for the first six months in each group. This resulted in an estimated sample size of 146 total women.

Descriptive

Categorical variables are compared by the X2 test for Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables are compared by the t-test or the Wilcoxon-rank sum test, if appropriate.

Time to First STD and STD Rates

For follow-up analysis, an STD was defined as either gonorrhea, chlamydia, trichomoniasis, HSV or PID. BV was categorized as positive (≥ 7), intermediate (4-6), and negative (<4). Time to first episode of STD was defined as the number of days from baseline to development of first episode of STD. STD rates per person-year were calculated as the sum of all episodes of STD divided by the sum of all the follow-up days for the same group of persons during the same time period, expressed as person-years. Because treatment was only administered for the first six months of the study, we calculated the STD rates for the first six months for comparative purposes. The 95% confidence interval for rates was calcualated assuming the Poisson distribution for incidence. The probability of remaining STD free was modeled using the Kaplan-Meier method.

Results

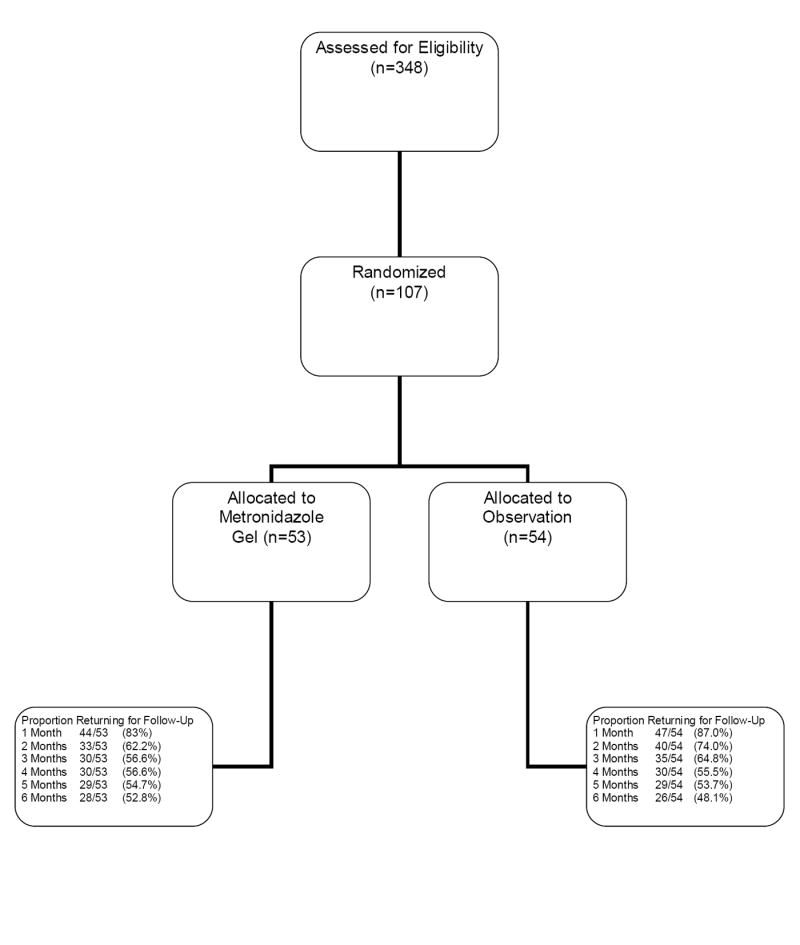

One hundred seven women were enrolled into the study with 54 randomized to observation and 53 to metronidazole gel (Figure I). Table 1 shows the distribution of baseline demographic and behavioral factors for women enrolled into the study. The mean age of the participants was 25.1 years and all were African-American. There were no significant differences in baseline demographic and clinical factors, including the percentage of adolescents enrolled into each arm.

Figure I.

Flow Diagram of Subject Progress

Table I.

Baseline Demographic and Behavioral Factors by Randomization Group

| Factor | Observation

n(%) |

MetronidazoleGel

n (%) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highest grade

completed |

|||

| < 12 | 12 (22.2) | 18 (34.0) | 0.29 |

| 12 | 30 (55.6) | 22 (41.5) | |

| > 12 | 12 (22.2) | 13 (24.5) | |

| Ever smoked | |||

| Yes | 30 (55.6) | 27 (50.9) | 0.43 |

| No | 24 (44.4) | 26 (49.1) | |

| Douching in

last 30 days |

|||

| Yes | 29 (53.7) | 36 (67.9) | 0.13 |

| No | 25 (46.3) | 17 (32.1) | |

| Ever had STD | |||

| Yes | 48 (88.9) | 42 (79.2) | 0.17 |

| No | 6 (11.1) | 11 (20.8) | |

| Used BC | |||

| Yes | 44 (86.3) | 43 (84.3) | 0.78 |

| No | 7 (13.7) | 8 (15.7) | |

| Condom last

sex |

|||

| Yes | 16 (31.4) | 18 (35.3) | 0.67 |

| No | 35 (68.6) | 33 (64.7) | |

| Baseline STD | |||

| Yes | 31 (60.8) | 29 (56.9) | 0.69 |

| No | 20 (39.2) | 22 (43.1) | |

| Mean ± sd | Mean ± sd | ||

| Current age | 24.7 ± 5.9 | 25.5 ± 6.0 | 0.40 |

| Total partners

past 30 days |

1.4 ± 0.8 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 0.40 |

| Total partners

past 3 mo |

1.4 ± 0.8 | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 0.18 |

| Last sex (days) | 7.9 ± 10.1 | 7.8 ± 7.4 | 0.97 |

| Age at first | 15.1 ± 2.0 | 15.5 ± 2.1 | 0.34 |

| Sexual

intercourse |

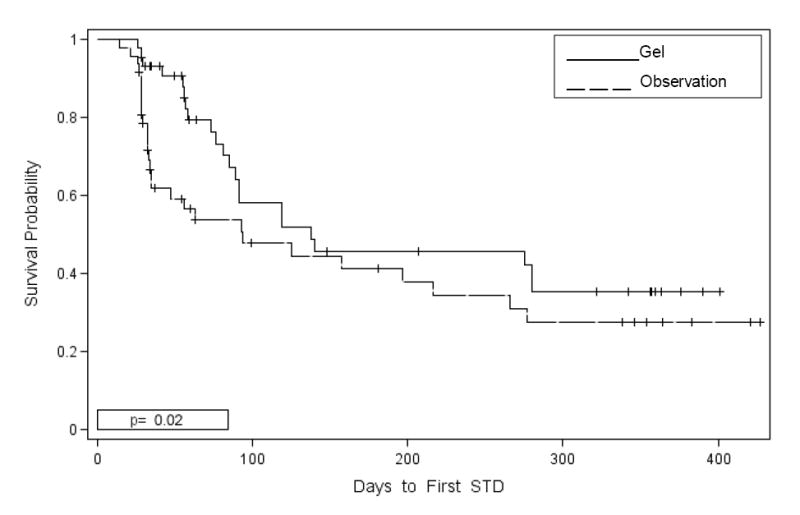

Time to Development of STD and STD Rates

Women randomized to metronidazole gel experienced a significantly longer time to development of STD compared to women randomized to observation (p= 0.02) (Figure II). The median time to develop STD was 94 days in the observational group and 138 days in the metronidazole group. The 6-month rate of STDs was 2.29/person-year (95% CI 1.95, 2.63) in the observational group compared to a 6-month STD rate of 1.58/person-year (95% CI 1.29, 1.87) in the metronidazole group which was significantly lower. A comparison of STD rates for the 6-month period following the end of the intervention (months 7-12) found no significant differences between the groups. The overall STD rates for the entire 12-month period was 1.64 (95 % CI 1.20, 2.08) in the observational group and 1.31 (95% CI 0.90, 1.72) in the treatment group. Follow-up was similar in both cohorts (31.12 person-years in the placebo group and 29.73 person-years in the treatment group). The distribution of STDs in the treatment group over 12 months was as follows: 3 (8.6%) chlamydia, 8 (22.9%) gonorrhea, 16 (45.7%) trichomonas, 3 (8.6%) HSV-2, 3 (8.6%) PID and 2 (5.7%) combined infections. Among the observation group over 12 months there were 13 (27.1%) chlamydia, 4 (8.3%) gonorrhea, 22 (45.8%) trichomonas, 5 (10.4%) HSV-2, 1 (2.1%) PID and 3 (6.3%) combined infections. Thus, the only significant difference between the groups in terms of individual pathogens was chlamydia. The proportion of chlamydia infections in the observation group compared to the treatment group was significantly greater (p= 0.013).

Figure II.

Percentage STD Free by Randomization Group among Women with Asymptomatic BV

Patterns of Vaginal Flora Over the Course of the Study

Table 2 shows the distribution of vaginal flora patterns stratified by Nugent groups over the first six months of the study. As anticipated, rates of BV during the initial six months of the study were generally higher in the women assigned to observation compared to those assigned to treatment. Prevalence of BV was not significantly different between the groups at months 9 and 12 reflecting the cessation of treatment at month 6.

Table II.

BV Scores in Tertiles by Study Group and Visit

| Group | Nugent

score |

1M

n(%) |

2M

n(%) |

3M

n(%) |

4M

n(%) |

5M

n(%) |

6M

n(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observation | <4 | 3 (6.4) | 11 | 2 (6.1) | 5 (17.9) | 5 (17.2) | 3 (11.1) |

| 4-6 | 4 (8.5) | (28.2) | 5 (15.2) | 5 (17.9) | 4 (13.8) | 5 (18.5) | |

| ≥ 7 | 40 (85.1) | 6 (15.4) | 26 | 18 | 20 | 19 | |

| 22 | (78.7) | (64.2) | (69.0) | (70.4) | |||

| (56.4) | |||||||

| Metronidazole | <4 | 13 (31.0) | 9 (29.0) | 8 (28.6) | 7 (24.1) | 6 (21.4) | 9 (33.3) |

| Gel | 4-6 | 5 (11.9) | 3 (9.7) | 7 (25.0) | 12 | 6 (21.4) | 4 (14.8) |

| ≥ 7 | 24 (57.1) | 19 | 13 | (41.4) | 16 | 14 | |

| (61.3) | (46.4) | 10 | (57.2) | (51.9) | |||

| (34.5) | |||||||

| p | 0.005 | 0.836 | 0.017 | 0.065 | 0.646 | 0.164 |

Comment

Bacterial vaginosis is associated with numerous obstetrical and gynecological complications including acquisition and transmission of HIV and other STDs. It is hypothesized that the lack of hydrogen-peroxide producing lactobacilli in the vaginal flora of women with BV is the major biological risk for STD acquisition although other factors such as elevated vaginal pH and local cytokine production which accompany BV may be operative as well 5, 6, 12-14. Cross-sectional studies have documented a significant association between BV and HIV seropositivity 15-17. Prospective studies have shown that HIV seroconversion is significantly associated with alterations in vaginal flora18. In terms of BV as a risk factor for transmission of HIV, Cu-Uvin et al showed that HIV infected women with BV were significantly more likely to have high levels of HIV in the lower genital tract than women without BV19.

BV is frequently present as a co-infection with cervical and vaginal STDs. Women with trichomoniasis are highly likely to be co-infected with BV 20-22. In a prospective study, acquisition of trichomoniasis was associated with abnormal vaginal flora on Gram’s stain (HR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.3-2.4). Infections with Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis have also been significantly associated with abnormal vaginal flora. In a cross-sectional study of women attending an STD clinic, lactobacilli were present in significantly fewer women infected with gonorrhea than uninfected women. In addition, among those women who reported recent sexual contact to men with gonorrhea, 28% of the women with gonorrhea had inhibitory lactobacilli present versus 73% of the women not acquiring the infection (p<0.05)23. In a more recent cross-sectional analysis, female sexual contacts of men with either gonorrhea or chlamydia were three to four times more likely to be infected with the STD if they had BV than if they had normal vaginal flora. Further, vaginal colonization with hydrogen-peroxide producing lactobacilli was negatively associated with infection with either gonorrhea or chlamydia24. A prospective, longitudinal study of female sex workers in Kenya found that absence of vaginal lactobacilli was significantly associated with acquisition of gonorrhea in a multivariate model controlling for other risk factors (HR, 1.7; 95%CI,_1.3-2.4)22. Bacterial vaginosis has also been found to be associated with incident HSV-2 3. There is also a clear association between BV and upper genital tract infection including endometritits and PID 25.

Despite all of the data suggesting that abnormal vaginal flora is a risk factor for STD/HIV, treatment of women with asymptomatic BV is not recommended except in certain circumstances 9. The lack of a recommendation for treatment is largely due to the fact that up until now, no data was available to show that treatment of BV could reduce rates of STD. A study design using a one time treatment regimen would be hampered by the fact that recurrence rates of BV are quite high, particularly in women at highest risk for STD/HIV. Thus, we used a combined approach of treatment followed by prophylactic therapy to attempt to maintain the vaginal flora as normal as possible for as long as possible. Prophylactic therapy has been shown to be beneficial for preventing recurrent BV 10. In our study, women assigned to twice weekly metronidazole gel maintained healthier vaginal flora during the treatment phase than the observational group although rates of BV were still high. This likely reflects inadequacy of current treatment regimens as well as difficulty adhering to twice weekly intravaginal therapy for the asymptomatic patient for six months. Using this approach we were able to demonstrate a significant reduction in the rate of chlamydia infections among women randomized to treatment and prophylaxis of asymptomatic BV versus those randomized to observation alone.

Due to limited resources we were required to halt enrollment prematurely and thus did not reach our targeted sample size. Nevertheless, the difference in chlamydia rates is highly significant. This study thus provides valuable data for use in designing similar intervention studies focused primarily on chlamydia. An additional hypothesis for the difference in chlamydial infection rates between the two groups of women in our study relates to an indole escape mechanism for chlamydia survival. One mechanism for host defense against chlamydia is the depletion of tryptophan. However, organisms associated with BV mayprovide an indole-rich environment which promotes production of tryptophan and thus enhances the ability of chlamydia to survive in the genitourinary tract 26.

In summary, this is the first study to show that treatment and prophylaxis of asymptomatic BV is associated with decreased rates of incident chlamydia infection. Based on this data, consideration should be given to routine treatment of women with asymptomatic BV; however, further studies are warranted to confirm these findings . In addition, studies enrolling more racially and ethnically diverse populations are needed. If our results are due to normalization of the vaginal flora, as we hypothesize, there is an urgent need to develop more effective treatments for BV both in terms of initial efficacy and decrease of recurrence. Development of more effective therapies for BV could add additional benefit to this approach.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: this work was supported by NIH Sexually Transmitted Disease Cooperative Research Centers grant 5U19A1038514-09. 3M domated metronidazole gel for use in this study.

Footnotes

The data has not previously been presented

Condensation Women with BV who were treated and placed on twice weekly metronidazole gel had a significantly longer time to develop chlamydia than women not treated.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Amsel R, Totten PA, Spiegel CA, Chen KCS, Eschenbach D, Holmes KK. Non-specific vaginitis: diagnostic and microbial and epidemiological associations. Am J Med. 1983;74:14–22. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)91112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen MS. Sexually transmitted diseases enhance HIV transmission: no longer a hypothesis. Lancet. 1998;351:5–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)90002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cherpes T, Meyn L, Krohn MA, Lurie J, Hillier SL. Association between acquisition of herpes simplex virus type 2 in women and bacterial vaginosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:319–25. doi: 10.1086/375819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watts D, Fazarri M, Minkoff H, Hillier SL, Sha B, Glesby M, Levine AM, Burk R, Palefsky JM, Moxley M, Ahdieh-Grant L, Strickler HD. Effects of bacterial vaginosis and other genital infections on the natural history of human papillomavirus infection in HIV-1-infected and high-risk HIV-1-uninfected women. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1129–39. doi: 10.1086/427777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hillier S. The vaginal microbial ecosystem and resistance to HIV. AIDS. 1998;14:17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klebanoff SJ, Hillier SL, Eschenbach DA, Waltersdorph AM. Control of the microbial flora of the vagina by H2O2 -generating lactobacilli. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:94–100. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grosskurth H, Mosha F, Todd J, Mwijarubi E, Kiokke A, Senkoro K, Mayaud P, Changalucha J, Nicoll A, ka-Gina G, Newell J, Mugeye K, Mabey D, Hayes R. Impact of improved treatment of sexually transmitted diseases on HIV infection in rural Tanzania: randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 1995;346:530–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91380-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wawer M, Sewankambo N, Serwadda D, Quinn T, Paxton L. Control of sexually transmitted diseases for AIDS prevention in Uganda: a randomized community trial. Rakai Project Study Group. Lancet. 1999;353:525–35. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)06439-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.CDC. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR11):49–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sobel J, Ferris D, Schwebke J, Nyirjesy P, Wiesenfeld H, Peipert J, Soper D, Ohmit S, Hillier S. Suppressive maintenance antibacterial therapy with 0.75% metronidazole vaginal gel to prevent recurrent bacterial vaginosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1283–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nugent RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of Gram stain interpretation. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:297–301. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.2.297-301.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paavonen J. Physiology and ecology of the vagina. Scand J Infect Dis. 1983;S40:31–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Redondo-Lopez V, Cook RL, Sobel JD. Emerging role of lactobacilli in the control and maintenance of the vaginal bacterial microflora. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12:856–872. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.5.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skarin A, Sylwan J. Vaginal lactobacilli inhibiting growth of Gardnerella vaginalis, Mobiluncus and other bacterial species cultured from vaginal content of women with bacterial vaginosis. Acta Path Microbiol Immunol Scand Sect B. 1986;94:399–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1986.tb03074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen CR, Duerr A, Pruithithada N, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and HIV seroprevalence among female commercial sex workers in Chiang Mai, Thailand. AIDS. 1995;9:1093–1097. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199509000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sewankambo N, Gray R, Waiver MJ, et al. HIV-1 infection associated with abnormal vaginal flora morphology and bacterial vaginosis. Lancet. 1997;350:546–550. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)01063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Royce R, Thorp J, Granados J, Savitz D. Bacterial vaginosis associated with HIV infection in pregnant women from North Carolina. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1999;20:382–6. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199904010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taha TE, Hoover DR, Dallabetta GA, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and disturbances of vaginal flora: association with increased acquisition of HIV. AIDS. 1998;12:1699–1706. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199813000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cu-Uvin S, Hogan J, Caliendo A, Harwell J, Mayer K, Carpenter C. Association between bacterial vaginosis and expression of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA in the female genital tract. CID. 2001;33:894–896. doi: 10.1086/322613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomason JL, Gelbart SM, Sobun JF, Schulien MB, Hamilton PR. Comparison of four methods to detect Trichomonas vaginalis. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:1869–1870. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.9.1869-1870.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wølner-Hanssen P, Krieger JN, Stevens CE, et al. Clinical manifestations of vaginal trichomoniasis. JAMA. 1989;261:571–576. doi: 10.1001/jama.1989.03420040109029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martin H, Richardson B, Nyange P, et al. Vaginal lactobacilli, microbial flora, and risk of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and sexually transmitted disease acquisition. JID. 1999;180:1863–8. doi: 10.1086/315127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saigh JH, Sanders CC, Sanders WE. Inhibition of Neisseria gonorrhoeae by aerobic and facultatively anaerobic components of the endocervical flora: evidence for a protective effect against infection. Infect Immun. 1978;19:704–710. doi: 10.1128/iai.19.2.704-710.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wiesenfeld H, Hillier S, Krohn MA, Landers D, Sweet R. Bacterial vaginosis is a strong predictor of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:663–8. doi: 10.1086/367658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haggerty C, Hiller SL, Bass DC, Ness RB. for the PID Evaluation and Clinical Health (PEACH) Study Investigators. Bacterial vaginosis and anaerobic bacteria are associated with endometritis. Clin Inf Dis. 2004;39:990–5. doi: 10.1086/423963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caldwell H, Wood H, Crane D, Bailey R, Jones RB, Mabey D, Maclean I, Mohammed Z, Peeling R, Roshick C, Schachter J, Solomon AW, Stamm WE, Suchland RJ, Taylor L, West SK, Quinn TC, Belland RJ, McClarty G. Polymorphisms in Chlamydia trachomatis tryptophan synthase genes differentiates between genital and ocular isolates. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1757–69. doi: 10.1172/JCI17993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]