Abstract

A computational approach based upon rigid-body docking, ad hoc filtering, and cluster analysis has been carried out to predict likely interfaces in LHR homodimers. Quaternary structure predictions emphasize the role of helices 4, 5 and 6, with prominence to helix 4, in mediating inter-monomer interactions. Intermolecular interactions essentially involve the transmembrane domains rather than the hydrophilic loops and do not implicate disulfide bridges.

Collectively, Molecular Dynamics simulations on the isolated receptor and computational modeling of LHR homodimerization suggest that mutation-induced LHR activation favors H4-H4 contacts involving the highly conserved W491 from both the receptors monomers.

Keywords: GPCR dimerization, rigid-body docking, quaternary structure predictions, comparative modeling, molecular dynamics simulations

INTRODUCTION

Increasing piece of evidence indicate that G protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs) exist as homo- and heterodimer/oligomers in the cell membrane (reviewed in refs. (Agnati et al., 2003; Bouvier, 2001; Bulenger et al., 2005; Franco et al., 2003; George et al., 2002; Kroeger et al., 2003; Maggio et al., 2005; Milligan, 2001; Park et al., 2004; Rios et al., 2001; Terrillon and Bouvier, 2004). A number of studies have shown that dimerization occurs early after biosynthesis, suggesting that it has a primary role in receptor maturation (reviewed in refs. (Bulenger et al., 2005; Terrillon and Bouvier, 2004)). For many proteins, oligomeric assembly has an important function in endoplasmic reticulum (ER) quality control because it masks specific retention signals or hydrophobic patches that would otherwise retain the proteins in ER. (Reddy and Corley, 1998) G protein coupling, downstream signaling and regulatory processes, such as internalization, have also been shown to be influenced by the dimeric nature of the receptors (reviewed in refs. (Maggio et al., 2005; Terrillon and Bouvier, 2004)). The question whether dimerization influences ligand-induced activation/regulation of GPCRs still remains to be answered. In fact, some studies suggest that ligand binding can regulate the dimer by either promoting or inhibiting its formation, whereas many others conclude that homodimerization and heterodimerization are constitutive processes that are not modulated by ligand binding (reviewed in ref. (Terrillon and Bouvier, 2004)). More resolved information on GPCR oligomerization has been inferred by Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) measurements, which showed that rhodopsin and opsin form constitutive dimers in dark-adaptive retinal membrane (Fotiadis et al., 2003; Park et al., 2004). Thus, regulated protein-protein interactions are key features of many aspects of GPCR function and there is now increasing evidence for GPCRs acting as part of multi-component units comprising a variety of signaling and scaffolding molecules (Brady and Limbird, 2002; Pierce et al., 2002).

The glycoprotein hormone receptors are not exceptions to this rule as an increasing number of reports is coming out providing evidence that they form supramolecular assemblies (Horvat et al., 2001; Hunzicker-Dunn et al., 2003; Nakamura et al., 2004; Roess et al., 2000; Roess and Smith, 2003; Tao et al., 2004; Urizar et al., 2005). Whether dimerization of these receptors, in particular, of the lutropin (LH) receptor (LHR) depends on LH or hCG binding is unclear (Horvat et al., 2001; Hunzicker-Dunn et al., 2003; Nakamura et al., 2004; Roess et al., 2000; Roess and Smith, 2003; Tao et al., 2004; Urizar et al., 2005). More clear is the evidence that higher order aggregates of LHR form upon agonist-induced receptor desensitization (Hunzicker-Dunn et al., 2003; Roess and Smith, 2003).

Recently, a homo-dimerization model of the crystal structure of the follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) receptor (FSHR) ectodomain in complex with FSH has been proposed, which is almost incompatible with inter-monomer contacts mediated by the transmembrane (TM) helices (Fan and Hendrickson, 2005). In apparent disagreement with that model, a couple of evidences from in vitro experiments support the hypothesis that the TMs participate in the intra-dimer interface both in the thyrotropin (TSH) and lutropin receptors (Nakamura et al., 2004; Urizar et al., 2005).

So far, predictions of likely interfaces of GPCR dimers essentially relied on sequence-based methods ((Dean et al., 2001); reviewed in (Filizola and Weinstein, 2005)).

We have developed a computational procedure for predicting the supramolecular organization of TM α-helical proteins by rigid-body docking (Casciari et al., 2005). Benchmarks of the approach were done on selected oligomers with known structure. In all the test cases, native-like quaternary structures, i.e. with Root Mean Square Deviation of the α-carbon atoms (Cα-RMSDs) lower than 2.5 Å from the native oligomer were achieved (Casciari et al., 2005). The effectiveness of the prediction protocol makes it suitable for ab initio quaternary structure predictions of other integral membrane proteins, including GPCRs. An attempt in this respect has been already reported, though based on an early and different version of the computational protocol, proving usefulness in aiding the interpretation of biophysical data and the design of novel in vitro experiments (Canals et al., 2003).

In this study, the computational protocol has been challenged in predictions of the LHR portions more likely involved in homodimerization.

METHODS

Computational modeling of the LHR

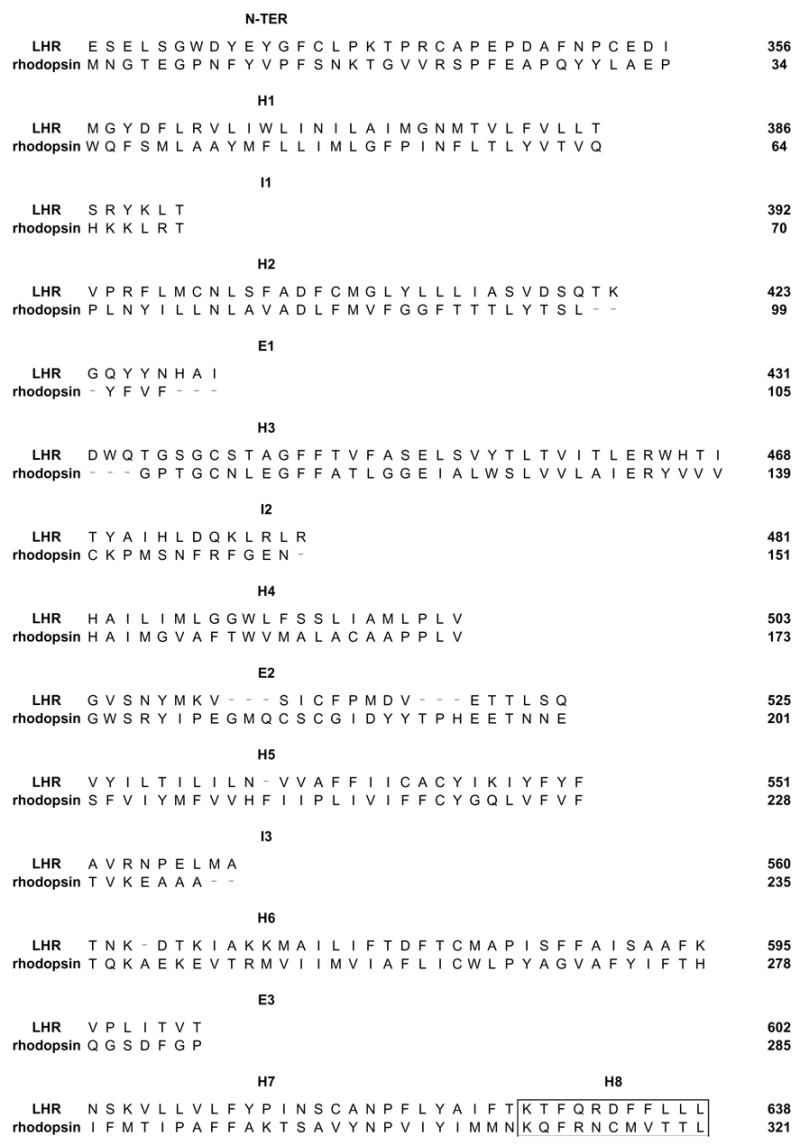

A novel model of the LHR was built by means of the comparative modeling software MODELER (Sali and Blundell, 1993), by using the latest rhodopsin structure as a template (i.e. PDB code: 1U19 (Okada et al., 2004)). The modeled sequence includes the TM helices (abbreviated as H), the three intracellular (i.e. I1, I2 and I3) and three extracellular (i.e. E1, E2 and E3) loops, as well as the 323–358 ectodomain sequence, which can be reasonably modeled based upon the N-terminus of rhodopsin (Fig. 1). A modified rhodopsin template was employed, in which the sequences 100–101 and 106–107 were deleted, which correspond to the H2/E1 junction and the first two amino acids of H3, respectively. The sequence 236–242, corresponding to the C-term of I3, was deleted as well. During comparative modeling, α-helical restraints were imposed on the LHR sequences 420–423 and 432–439. Using the sequence alignment shown in Fig. 1, 200 models were obtained by randomizing the Cartesian coordinates of the model through a random number uniformly distributed in an interval from −4 Å to 4 Å (Sali and Blundell, 1993). Among the 450 models finally obtained, the two were selected, which showed low restraint violations associated with high values of the 3D-Profile score, computed by means of the Protein Health module in the QUANTA 2000 package, and low numbers of main-chain and side-chains in non allowed conformation and close contacts. These models were first completed by the addition of the polar hydrogens and then subjected to automatic and manual rotation of the side chain torsion angles when in non allowed conformations, leading to 73 different input structures for further calculations. These input structures were subjected to energy minimization and Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations by means of the CHARMM program (Brooks et al., 1983), using an implicit membrane-water model (i.e. IMM1) recently implemented in CHARMM (Lazaridis, 2003). This is an extension of the EEF1 implicit water solvation model to heterogeneous membrane-aqueous media (Lazaridis, 2003). In this respect, the adjustable parameter “a” and the non polar core thickness were set equal to 0.85 and 32 Å, respectively. Minimizations were carried out by using 1500 steps of steepest descent followed by a conjugate gradient minimization, until the root mean square gradient was less than 0.001 kcal/mol Å. A disulfide bridge patch was applied to C439 and C514, respectively located in H3 and E2.

Figure 1.

Alignment between bovine rhodopsin (i.e. template) and the human LHR (target) that has been employed for comparative modeling. The amino acid stretches 100–101, 106–107 and 236–242 have been deleted from the 1U19 template. The boxed sequences correspond to H8.

The “united atom approximation” was employed. The lengths of the bonds involving the hydrogen atoms were restrained by the SHAKE algorithm, allowing an integration time step of 0.001 ps. The systems were heated to 300 K with 5 K rise, every 100 steps per 6000 steps, by randomly assigning velocities from the Gaussian distribution. After heating, the system was allowed to equilibrate for 64 ps.

The secondary structure of the helix bundle was preserved, by assigning distance restraints (i.e. minimum and maximum allowed distances of 2.7 Å and 3.0 Å, respectively) between the backbone oxygen atom of residue i and the backbone nitrogen atom of residue i+4, except for prolines. The scaling factor of such restraints was 10 and the force constant at 300 K was 10 kcal/mol Å. The application of these intra-helical distance restraints was instrumental in: (a) reducing the system degrees of freedom, (b) inferring the structural/dynamics role of prolines, and (c) letting the helices move as rigid bodies, consistent with the experimental evidences on rhodopsin activation (Farrens et al., 1996). The receptor amino acids, which were found in non canonical α-helical conformation in the input structure, condition inherited from the rhodopsin template, were not subjected to any intra-backbone distance restraint. Short (100 ps) equilibrated MD runs were carried out, probing different input structures and different combinations of intra-helical distance restraints. The latter tests consisted in applying distance restraints to different amino acid stretches in each helix. Finally, the computation conditions and the input receptor structure were chosen, which, following MD simulation, produced average arrangements characterized by good stereochemical quality, together with structural similarity to rhodopsin. Three different input structures were, therefore, selected for 1ns MD production phases. For each MD run, the structures averaged over the first and last 500 ps, as well as over the entire 1ns trajectory were considered for docking simulations.

Docking simulations of LHR dimerization

Predictions of oligomeric structures were done by means of the rigid-body docking program ZDOCK 2.1, a version of the Fast Fourier Transform-based algorithm, which utilizes the Pairwise Shape Complementarity (PSC) scoring function, neglecting desolvation (Chen and Weng, 2003).

For each protein system, the first docking run consisted of docking two identical copies of the monomer, i.e. one monomer was used as fixed protein (i.e. target) and the other as mobile protein (i.e. probe). Different average minimized structures were employed in docking simulations.

A rotational sampling interval of 6° was employed, i.e. dense sampling, and the best 4000 solutions were retained and ranked according to the ZDOCK score. These solutions were subjected to a filter, i.e. the “membrane topology” filter, which discards all the solutions that violate the membrane topology requirements. In detail, the filter discards all the solutions characterized by a deviation angle from the original z-axis, i.e. tilt angle, and a displacement of the geometrical center along the z-axis, i.e. z-offset, above defined threshold values. For the tilt angle and the z-offset, thresholds of 0.4 radians and 6.0 Å were, respectively, employed. The filtered solutions from each run were merged with the target protein, leading to an equivalent number of oligomers that were subjected to cluster analysis. The Cα-RMSD threshold for each pair of superimposed dimers was set equal to 2.5 Å. All the amino acid residues in the dimer were included in Cα-RMSD calculations.

To identify the cluster of solutions with the best membrane topology, i.e. with the lowest values of both tilt angle and z-offset, the MemTop index was defined according to the following formula: , were 〈tilt 〉 and 〈Zoff 〉 are, respectively, the tilt angle and the z-offset averaged over all the members of a given cluster. In general, MemTop indexes close to 0.0 are indicative of good membrane topology.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In this study, a computational approach based upon rigid-body docking, ad hoc filtering, automatic cluster analysis and visual inspection of the cluster centers (i.e. the structure with the highest number of neighbors in a cluster) has been employed to predict likely interfaces in LHR homodimers. Docking simulations have been done on a novel model of the LHR, which, differently from the previous model (Fanelli et al., 2004), holds the 323–358 ectodomain sequence that forms a β-sheet with E2, feature inherited from rhodopsin structure.

The filtering of the 4000 best ZDOCK solutions from each run reduced by more than 98% the number of reliable solutions, i.e. the solutions that fulfill the membrane-topology requirements, thus improving the effectiveness of the following automatic cluster analysis and visual inspection of the cluster centers. The number of reliable solutions was less than 2% independently of the receptor structure employed and hence too low for giving significance to the cluster population. Therefore, the membrane topology parameter MemTop, rather than the cluster population, was used as major criterion for solution selection, i.e. such index has to be close to 0.0 for an optimal membrane topology.

The receptor configuration, which gave the highest number of reliable solutions (i.e. 67 out of 4000), was an energy minimized average over the 2000 structures collected during one of the different 1 ns MD production phases. Automatic cluster analysis divided the 67 reliable solutions into 15 clusters. Among these clusters, the ones showing a MemTop index lower than 1.0 were essentially characterized by H4-H4 (Fig. 2a, MemTop score equal to 0.69), or H4-H6 (Fig. 2b, MemTop score equal to 0.34), or H5-H6 (MemTop score equal to 0.80) contacts. As for the H4-H4 dimer, also H1 and H3, from one monomer, make contacts with H4 from the other monomer (Fig. 2a). This dimer is characterized by the approaching of the highly conserved W491 from both monomers, providing a possible explanation for the fact that W491, despite its very high conservation, is almost exposed to the lipids in the inactive receptor forms. Interestingly, previous computations highlighted the conserved tryptophan as a marker of the orientation changes of H4 associated with mutation-induced activation of the LHR. In fact, in the structure representative of the ground state, the tryptophan is involved in H-bonding interaction with N400 (in H2), whereas in the structures of the constitutively active mutants it becomes more exposed to the lipids loosing its interaction with N400 (Fanelli et al., 2004). Collectively, MD simulations on the isolated receptor and computational modeling of LHR homodimerization suggest that mutation-induced LHR activation favors H4-H4 contacts involving the highly conserved tryptophan from both the receptors monomers. These inferences agree with in vitro cysteine cross-linking experiments on the D2 dopamine receptor, indicating a dynamic involvement of H4 in forming a symmetrical dimer interface (Guo et al., 2005). As for the H4-H6 dimer, also H5, from one monomer, participates in the interaction with H4, from the other monomer (Fig. 2b). Finally, for the H5-H6 dimer, also H7, from one monomer, participates in the interaction with H5, from the other monomer. Another possible docking solution but extracted from a cluster with a MemTop score higher than 1.0 (i.e. 1.62) is characterized by contacts between H4, from one monomer, and both H5 and H3, from the other monomer.

Figure 2.

Top: Cartoon representation of two different dimeric models of the LHR, seen from the intracellular side in a direction perpendicular to the membrane surface. The extracellular loops are not shown. H1, H2, H3, H4, H5, H6, H7 and H8 are, respectively, colored in blue, orange, green, pink, yellow, cyan, violet and magenta. I1, I2 and I3 are respectively colored in lime, slate and salmon. Only the helices participating in the inter-monomer interfaces are indicated by numbers. Bottom: amino acids that contribute to the inter-monomer interface. Squares are colored according to the amino acid location (see above in the legend). White squares indicate E2. Drawings were done by means of the software PYMOL 0.97 (http://pymol.sourceforge.net/).

Docking simulations on an alternative average LHR structure predict another possible dimer characterized by contacts between H4, from one monomer, and both H6 and H7 from the other monomer.

Consistent with evidence from in vitro experiments (Tao et al., 2004), no disulfide linkages are predicted to participate in inter-monomer interactions. The latter essentially consist in weak van der Waals interactions between hydrophobic amino acids (Fig. 2). In summary, the results of this study emphasize the role of H4, H5 and H6, with prominence to H4, in mediating inter-monomer interactions in LHR homodimers. These results are consistent with the general inferences from sequence-based predictions on different GPCRs ((Dean et al., 2001); reviewed in (Filizola and Weinstein, 2005)). More LHR configurations need to be probed in docking simulations to improve the effectiveness of quaternary structure predictions. Docking simulations on the most likely dimers are expected to provide hints into the architecture of higher-order oligomers. However, unraveling the mechanism of the observed LHR aggregation in multimolecular complexes following hormone-induced desensitization (Hunzicker-Dunn et al., 2003; Roess and Smith, 2003) awaits computational modeling of the hormone-induced active states of the receptor.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a Telethon-Italy grant n. S00068TELA and the DK33973 NIH grant.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agnati LF, Ferre S, Lluis C, Franco R, Fuxe K. Molecular mechanisms and therapeutical implications of intramembrane receptor/receptor interactions among heptahelical receptors with examples from the striatopallidal GABA neurons. Pharmacol Rev. 2003;55:509–550. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.3.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvier M. Oligomerization of G-protein-coupled transmitter receptors. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:274–286. doi: 10.1038/35067575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady AE, Limbird LE. G protein-coupled receptor interacting proteins: emerging roles in localization and signal transduction. Cell Signal. 2002;14:297–309. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00239-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks BR, Bruccoleri RE, Olafson BD, States DJ, Swaminathan S, Karplus M. Charmm: a program for macromolecular energy, minimization and dynamics calculations. J Comput Chem. 1983;4:187–217. [Google Scholar]

- Bulenger S, Marullo S, Bouvier M. Emerging role of homo- and heterodimerization in G-protein-coupled receptor biosynthesis and maturation. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canals M, Marcellino D, Fanelli F, Ciruela F, De Benedetti P, Goldberg SR, Neve K, Fuxe K, Agnati LF, Woods AS, Ferre S, Lluis C, Bouvier M, Franco R. Adenosine A2A-dopamine D2 receptor-receptor heteromerization: qualitative and quantitative assessment by fluorescence and bioluminescence energy transfer. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:46741–46749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306451200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casciari D, Seeber M, Fanelli F. Effective prediction of the supramolecular structure of transmembrane proteins: a computational approach. 2005 submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Chen R, Weng Z. A novel shape complementarity scoring function for protein-protein docking. Proteins. 2003;51:397–408. doi: 10.1002/prot.10334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean MK, Higgs C, Smith RE, Bywater RP, Snell CR, Scott PD, Upton GJ, Howe TJ, Reynolds CA. Dimerization of G-protein-coupled receptors. J Med Chem. 2001;44:4595–4614. doi: 10.1021/jm010290+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan QR, Hendrickson WA. Structure of human follicle-stimulating hormone in complex with its receptor. Nature. 2005;433:269–277. doi: 10.1038/nature03206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanelli F, Verhoef-Post M, Timmerman M, Zeilemaker A, Martens JW, Themmen AP. Insight into mutation-induced activation of the luteinizing hormone receptor: molecular simulations predict the functional behavior of engineered mutants at M398. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:1499–1508. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrens DL, Altenbach C, Yang K, Hubbell WL, Khorana HG. Requirement of rigid-body motion of transmembrane helices for light activation of rhodopsin. Science. 1996;274:768–770. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filizola M, Weinstein H. The study of G-protein coupled receptor oligomerization with computational modeling and bioinformatics. Febs J. 2005;272:2926–2938. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fotiadis D, Liang Y, Filipek S, Saperstein DA, Engel A, Palczewski K. Atomic-force microscopy: Rhodopsin dimers in native disc membranes. Nature. 2003;421:127–128. doi: 10.1038/421127a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco R, Canals M, Marcellino D, Ferre S, Agnati L, Mallol J, Casado V, Ciruela F, Fuxe K, Lluis C, Canela EI. Regulation of heptaspanning-membrane-receptor function by dimerization and clustering. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:238–243. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00065-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George SR, O’Dowd BF, Lee SP. G-protein-coupled receptor oligomerization and its potential for drug discovery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:808–820. doi: 10.1038/nrd913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W, Filizola M, Weinstein H, Javitch JA. Crosstalk in G protein-coupled receptors: Changes at the transmembrane homodimer interface determine activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:17495–17500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508950102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvat RD, Barisas BG, Roess DA. Luteinizing hormone receptors are self-associated in slowly diffusing complexes during receptor desensitization. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:534–542. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.4.0622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunzicker-Dunn M, Barisas G, Song J, Roess DA. Membrane organization of luteinizing hormone receptors differs between actively signaling and desensitized receptors. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:42744–42749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306133200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroeger KM, Pfleger KD, Eidne KA. G-protein coupled receptor oligomerization in neuroendocrine pathways. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2003;24:254–278. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazaridis T. Effective energy function for proteins in lipid membranes. Proteins. 2003;52:176–192. doi: 10.1002/prot.10410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggio R, Novi F, Scarselli M, Corsini GU. The impact of G-protein-coupled receptor hetero-oligomerization on function and pharmacology. Febs J. 2005;272:2939–2946. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan G. Oligomerisation of G-protein-coupled receptors. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:1265–1271. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.7.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K, Yamashita S, Omori Y, Minegishi T. A splice variant of the human luteinizing hormone (LH) receptor modulates the expression of wild-type human LH receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:1461–1470. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada T, Sugihara M, Bondar AN, Elstner M, Entel P, Buss V. The retinal conformation and its environment in rhodopsin in light of a new 2.2 A crystal structure. J Mol Biol. 2004;342:571–583. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park PS, Filipek S, Wells JW, Palczewski K. Oligomerization of G protein-coupled receptors: past, present, and future. Biochemistry. 2004;43:15643–15656. doi: 10.1021/bi047907k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce KL, Premont RT, Lefkowitz RJ. Seven-transmembrane receptors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:639–650. doi: 10.1038/nrm908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy PS, Corley RB. Assembly, sorting, and exit of oligomeric proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum. Bioessays. 1998;20:546–554. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199807)20:7<546::AID-BIES5>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios CD, Jordan BA, Gomes I, Devi LA. G-protein-coupled receptor dimerization: modulation of receptor function. Pharmacol Ther. 2001;92:71–87. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(01)00160-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roess DA, Horvat RD, Munnelly H, Barisas BG. Luteinizing hormone receptors are self-associated in the plasma membrane. Endocrinology. 2000;141:4518–4523. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.12.7802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roess DA, Smith SM. Self-association and raft localization of functional luteinizing hormone receptors. Biol Reprod. 2003;69:1765–1770. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.103.018846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sali A, Blundell TL. Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:779–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao YX, Johnson NB, Segaloff DL. Constitutive and agonist-dependent self-association of the cell surface human lutropin receptor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:5904–5914. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311162200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terrillon S, Bouvier M. Roles of G-protein-coupled receptor dimerization. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:30–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urizar E, Montanelli L, Loy T, Bonomi M, Swillens S, Gales C, Bouvier M, Smits G, Vassart G, Costagliola S. Glycoprotein hormone receptors: link between receptor homodimerization and negative cooperativity. Embo J. 2005;24:1954–1964. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]