Summary

Pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase 1 (PDP1) catalyzes dephosphorylation of pyruvate dehydrogenase (E1) in the mammalian pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC) whose activity is regulated by the phosphorylation-dephosphorylation cycle by the corresponding protein kinases (PDHKs) and phosphatases. The activity of PDP1 is greatly enhanced through Ca2+-dependent binding of the catalytic subunit (PDP1c) to the L2 (inner lipoyl) domain of dihydrolipoyl acetyltransferase (E2), which is also integrated in PDC. Here we report the crystal structure of the rat PDP1c at 1.8Å resolution. The structure reveals that PDP1 belongs to the PPM family of protein serine/threonine phosphatases which, in spite of low sequence identity, share the structural core consisting of the central β-sandwich flanked on both sides by loops and α-helices. Consistent with the previous studies, two well-fixed Mg2+ ions are coordinated by five active site residues and five water molecules in the PDP1c catalytic center. Structural analysis indicates that while the central portion of the PDP1c molecule is highly conserved among the members of the PPM protein family, a number of structural insertions and deletions located at the periphery of PDP1c likely define its functional specificity towards the PDC. One notable feature of PDP1c is a long insertion (residues 98–151) forming a unique hydrophobic pocket on the surface that likely accommodates lipoyl moiety of the E2 domain in a fashion similar to that of PDHKs. The cavity, however, appears more open than in PDHK, suggesting that its closure may be required to achieve tight, specific binding of the lipoic acid. We propose a mechanism in which the closure of the lipoic acid binding site is triggered by the formation of the inter-molecular (PDP1c/L2) Ca2+ binding site in a manner reminiscent of the Ca2+-induced closure of the regulatory domain of troponin C.

Keywords: pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase, catalytic subunit, crystal structure, phosporylation/dephosphorylation cycle, dephosphorylation regulation

Mammalian pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC)1 catalyzes the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA and reduction of NAD+ through a concerted action of the three major components: pyruvate dehydrogenase (E1), dihydrolipoyl acetyltransferase (E2) and dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase (E3). PDC activity couples two major energy-generating pathways: the glycolysis and citric acid cycle. PDC is tightly regulated by a phosphorylation-dephosphorylation cycle that determines the proportion of active E1. The inactivation of PDC by phosphorylation of several serine residues on E1 α chain is catalyzed by pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDHK)2, whereas pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase (PDP) reactivates E1 by removing the phosphates. PDP1, a dominant isoform in Ca2+-sensitive tissues3, consists of two subunits: the 96-kDa subunit that is thought to be regulatory (PDP1r), and the 52.6-kDa catalytic subunit (PDP1c)4. PDP1c catalyzes the dephosphorylation reaction that requires Mg2+ and is stimulated by Ca2+ ions5–7. The calcium-mediated activation is particularly important in the calcium-responsive tissues such as muscle, kidney and brain, where it stimulates the pyruvate dehydrogenase reaction and oxidative phosphorylation to satisfy the increased demand for energy. The activities of PDP1 or PDP1c are greatly increased by Ca2+-dependent binding of the catalytic subunit to the L2 (inner lipoyl) domain of E28 so that dephosphorylation is intramolecular. In the absence of Ca2+, PDP1 does not bind to E2 and dephosphorylation is intermolecular, the rate of reaction is limited by diffusion-collision and decreases to the values comparable to that of dephosphorylation of uncomplexed phosphorylated E19.

PDP1r is a flavoprotein with a bound FAD4 and its regulatory role is poorly understood. Apparently, PDP1r downregulates the PDP1 reaction, since increased Mg2+ concentrations are required for efficient catalysis by the PDP1 heterodimer as compared to that of isolated PDP1c9. PDP1c belongs to the PPM family of serine/threonine phosphatases10 yet it shares only ~21–24% sequence identity with the protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C) from the different organisms (Toxoplasma gondi and human PP2Cs11, human PPM1K and phosphatase 2C domain of PPM1B), whose crystal structures were previously determined12 (see also PDB entries 2I44, 2P8E and 2IQ1). Another crystal structure of the catalytic domain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein phosphatase (PstP) shows similar principal motifs, suggesting the unified catalytic and substrate recognition mechanisms for the PPM family phosphatases13. The protein Ser/Thr phosphatases are metalloenzymes with binuclear metal-binding site that catalyses the dephosphorylation, presumably by a nucleophilic attack of the phosphate by metal-activated water molecule or hydroxide ion.

In order to better understand the dephosphorylation reaction in PDC, as well as the interactions and regulatory issues in PDP1c functional complexes, we have determined the crystal structure of rat PDP1c.

The structure of PDP1c

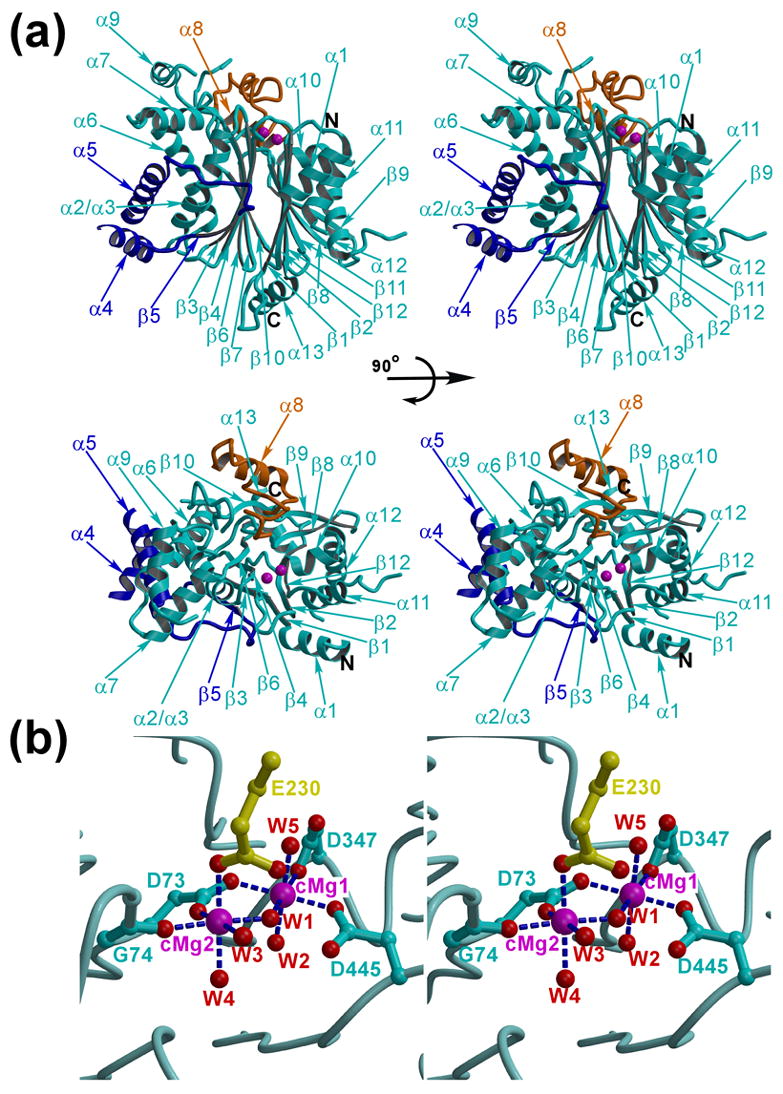

The asymmetric unit of PDP1c crystal structure contains two nearly identical molecules related by the non-crystallographic twofold rotational symmetry. The molecules can be superimposed with a root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 0.022Å for the 382 Cα atoms. The individual molecule of PDP1c is built around the central β-sandwich comprising the two antiparallel β-sheets and flanked on each side by loops and α-helices (Figure 1(a)). One β-sheet includes strands β1, β2, β12, β11, β8 and β9 with flanking antiparallel helices α11 and α12. In addition, the N- and C-terminal helices α1 and α13 protrude from this β-sheet out of the strands β1 and β12, respectively. The second β-sheet includes strands β5, β3, β4, β6, β7 and β10 surrounded by the antiparallel helices α6 and α2/α3 that form a bundle with the other two antiparallel helices α4 and α5. The short helices α7, α8 and α9 with connecting loops are located on the top of the molecule above the β-sandwich. Some of the solvent-exposed parts of the PDP1c molecule are disordered and not included in the model. These are the residues 111–114, 152–157, 304–314, 374–404 and 418–442 that probably form flexible loops in the PDP1c molecule. However, more than 80% of the molecule is well defined, as judged by the Ramachandran plot, RMSD from standard bond lengths and bond angles, and the overall temperature factor (Table 1).

Figure 1. The PDP1c structure.

(a) The two stereo views of the PDP1c structure (cyan) are shown as the ribbon diagrams. The unique structural insertion (residues 98–151) that forms a PDP1c-specific hydrophobic pocket on the enzyme surface and the flap segment are colored in blue and orange, respectively. The catalytic site is marked by the two Mg2+ ions (magenta spheres). (b) The PDP1 catalytic site. The color scheme is the same as in (a). The view corresponds to that of the lower panel in (a). The side chain of the Glu230 residue from the symmetry-related molecule is shown in yellow. The Mg2+ coordination bonds are indicated by the blue dashed lines. W1 – W5 are the five water molecules coordinating the two catalytic metals (cMg1 and cMg2)

Table 1.

Crystallographic statistics

| Data collection | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Space group | P212121 | ||

| Unit cell parameters (Å) | a = 65.32, b = 72.22, c = 96.09, α = β = γ = 90° | ||

| Synchrotron beam line | APS 22ID | ||

| Data set | Native | PIP | HgCl2 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50–1.81 (1.87–1.81)* | 30.0–2.80 (2.9–2.8) | 30–3.0 (3.11 – 3.0) |

| Reflections (Unique) | 37223 | 11582 | 7159 |

| Redundancy | 3.3 (2.6) | 7.6 (26.9) | 3.4 (1.6) |

| I/σ(I) | 15.0 (1.9) | 28.6 (5.5) | 20.7 (4.65) |

| Rmerge (%) | 6.5 (48.0) | 7.6 (26.9) | 8.3 (27.7) |

| Completeness (%) | 88.8 (89.3) | 99.8 (94.6) | 75.6 (30.0) |

| Phasing statistics | |||

| Space group | P212121 | ||

| Resolution (Å) | 30.0 – 3.0 | ||

| Figure of merit | 0.71 | ||

| Refinement | Model quality | ||

| Space group | P21 | RMSD bond length (Å) | 0.012 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50.0 – 1.8 (1.88 – 1.81) | RMSD bond angles (°) | 1.98 |

| Reflections used | 64759 | RMSD improper angles (°) | 1.16 |

| Rfactor (%) | 21.8 (32.3) | ||

| Rfree (%) | 26.8 (28.6) | ||

| Ramachadran plot (Regions) | Number of residues(%) | ||

| Overall B-factor (Å2) | 40.83 | Most favorable | 87.4 |

| Number of protein atoms | 6082 | Allowed | 11.7 |

| Number of water molecules | 394 | Generously allowed | 0.9 |

| Number of Mg2+ ions | 4 | Disallowed | 0.0 |

Rmerge=ΣhklΣj | Ij(hkl) − <I(hkl)> | /ΣhklΣj <I(hkl)>, where Ij(hkl) and <I(hkl)> are the intensity of measurement j and the mean intensity for the reflection with indices hkl, respectively.

Rfactor, free=Σhkl|| Fcalc(hkl) | − |Fobs(hkl) || /Σhkl| Fobs|, where the crystallographic R-factor is calculated including and excluding reflections in the refinement. The free reflections constituted 5% of the total number of reflections.

RMSD – root mean square deviation.

I/σ(I) – ratio of mean intensity to a mean standard deviation of intensity.

The data for the highest resolution shell are shown in parentheses.

Notes to Table 1

The recombinant PDP1c was prepared as described elsewhere (to be published). Crystals were obtained using a sitting drop vapor diffusion method at 295 K by mixing 2 μl of the protein solution containing 10 mg/ml PDP1c in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl and 0.1 mM EDTA with an equal volume of the reservoir solution containing 30% ethylene glycol, 0.1 M MES, pH 6.0. Crystals were flash-frozen in 30% ethylene glycol, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 25 mM KCl, 0.05 mM EDTA, 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. The crystals belong to the space group P21 and possess perfect merohedral twinning with the twinning operator {−h, −k, l}24. There are two molecules in the asymmetric unit related by the non-crystallographic twofold axis closely resembling the crystallographic P212121 symmetry. The unit cell parameters are a=65.32 Å, b=72.22 Å, c=96.09 Å and α=β=γ =90°. The native diffraction data at 1.8Å resolution were collected at the synchrotron at 100 K and were processed using the program HKL200025. The structure was solved by the multiple isomorphous replacement (MIR) method using the platinum and mercury heavy atom derivatives. The positions of the heavy atoms were determined by difference Patterson and difference Fourier methods using the CCP4 program suite26, the MIR phases were calculated with the MLPHARE program26 and improved by the solvent flattening using the DM program26. The model was built manually using the interactive graphics program O27 and refined using the twinning protocol implemented in the CNS program28. The refinement converged to a final R-factor of 21.8% (Rfree=26.8%).

In the crystal, the PDP1c molecules make only a limited number of the polar contacts and the crystal packing does not suggest any stable oligomeric states in solution (see, however, below). Nevertheless, it was shown that PDP1c exists in solution in the dynamic monomer/dimer equilibrium8 and that the formation of the functional complexes with PDP1r and/or L2 domain of E24, 8 shifts this equilibrium towards the monomeric state.

The catalytic site

The binuclear cluster of the magnesium atoms located between the β-sheets forms a core of the catalytic site (Figure 1(b)). Identification of the Mg2+ ions was supported by the electron density maps, crystallographic refinement, and the fact that magnesium chloride was present in the crystallization buffer. The two Mg2+ ions are separated by 3.7Å. Each of the Mg2+ ions is octahedrally coordinated by six oxygen atoms. The first Mg2+ ion (cMg1) interacts with the side chains of the aspartic residues Asp73, Asp347, Asp445 and three water molecules. The second Mg2+ ion (cMg2) interacts also with the side chain of Asp73, carbonyl oxygen of Gly74 and three water molecules. In addition, an exposed loop (residues 228–233) of the symmetry related molecule is trapped in the active site where the side chain of Glu230 coordinates cMg2 (Figure 1(b)). One of the water molecules (W1, Figure 1(b)) bridges cMg1 and cMg2. The distances between magnesium and coordinating oxygen atoms are within the 2.0 – 2.18Å range. The perfect coordination of the catalytic Mg2+ ion achieved through participation of the symmetry related molecule suggests that the crystallographic dimer, though apparently unstable, may correspond to the PDP1c dimeric state observed in solution8.

The fact that the increased concentration of Mg2+ is required for the efficient PDP1c catalysis upon formation of the PDP1c/PDP1r heterodimer led to suggestion that PDP1r may modify or block the PDP1c catalytic site9. The regulation through the remodeling of the active site that, in particular, affects the coordination geometry of the metal ions was also proposed for the other systems utilizing the two-metal mediated catalytic mechanism. For instance, transcription factors employ a long coiled-coil domain protruding through the secondary channel of RNA polymerase to target the catalytic Mg2+ ions with the two or more acidic residues located at the tip of the coiled-coil domains14, 15; RNase H functions efficiently only when the two metal ions are separated by an ideal distance and possess an appropriate coordination geometry16. Altogether, these data and our observation that the symmetry-related molecule is involved in coordination of the catalytic Mg2+ ion support a hypothesis that a similar remodeling of the PDP1c catalytic center may mediate regulation of the PDP1c activity by PDP1r. The presence of a low-affinity Mg2+ binding site in PDP1r would explain the Mg2+-dependent regulatory effect: at low Mg2+ concentrations, this site will remain unoccupied, allowing one of the acidic residues (that would be involved in metal coordination) to coordinate the PDP1c catalytic Mg2+ ion instead, thereby blocking access of the natural substrate to the active site. In contrast, at high Mg2+ concentrations this putative acidic side chain would switch interactions to the internal PDP1r Mg2+ ion, causing the release of PDP1r from the catalytic center and the recovery of the PDP1c active configuration.

Comparison with the PPM phosphatases

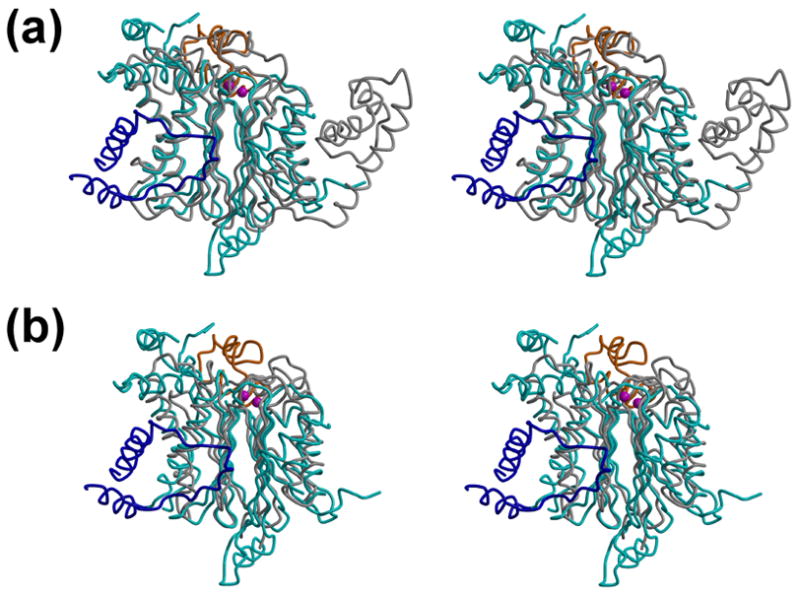

A number of structures for the human PP2C-like phosphatases that exhibit high similarity in the three-dimensional structures are now available in the PDB (see above). We therefore present comparison with one of the human proteins, PP2C12, as well as with another member of the PPM family, bacterial PstP13 that is evolutionary distant from the eukaryotic enzymes. Superposition of the PDP1c on the PP2C and PstP structures shows RMSD values of 2.6Å and 3.4Å for the 234 and 213 Cα atoms, respectively (Figure 2(a) and (b)). As expected for the PPM family members, many elements of the secondary structure, as well as the structural topology, are conserved among PDP1c, PP2C and PstP (Figure 2(a) and (b)) in spite of a quite low sequence similarity (21% and 17% identity for PP2C and PstP, respectively). The conserved structural motif represents the β-sandwich comprising the two antiparallel β-sheets, each of which are flanked by two antiparallel α-helices. There are five strands conserved in each β-sheet. Both PDP1c and PP2C have an additional β-strand (β1) at the edge of one β-sheet. PDP1c has a unique additional β-strand (β5) in the second β-sheet. New elements of the secondary structure in PDP1c, as compared to PP2C and PstP, include the N-terminal helix (α1), the C-terminal helix (α13) and the short helices α7 and α9. The large insertion in PDP1c (residues 98–151) that has no counterpart in either PP2C or PstP (Figure 2(a) and (b)) forms the PDP1-specific additional elements of the secondary structure: the short helix α4, a loop region with the short strand β5, and the long helix α5 aligned along the helix α2/α3 (Figure 1(a)). Remarkably, the molecular surface representation (Figure 3(a)) reveals the large hydrophobic cavity formed by this structural insertion. Other insertions in PDP1c include residues 371–411 and 430–454 which appeared disordered in the crystal structure. Spatially they could be folded in the same area as the remote C-terminal domain of PP2C built of three antiparallel helices (Figure 2(a)).

Figure 2. Comparison of PDP1c with the PP2C and PstP phosphatases.

(a, b) Superposition of the PDP1c with the PP2C (a) and PstP (b) structures. The same color scheme as in the Figure 1(a) is used for the PDP1c structure, whereas the structures of PP2C (a) and PstP (b) are colored in gray. The view corresponds to that of the upper panel of Figure 1(a).

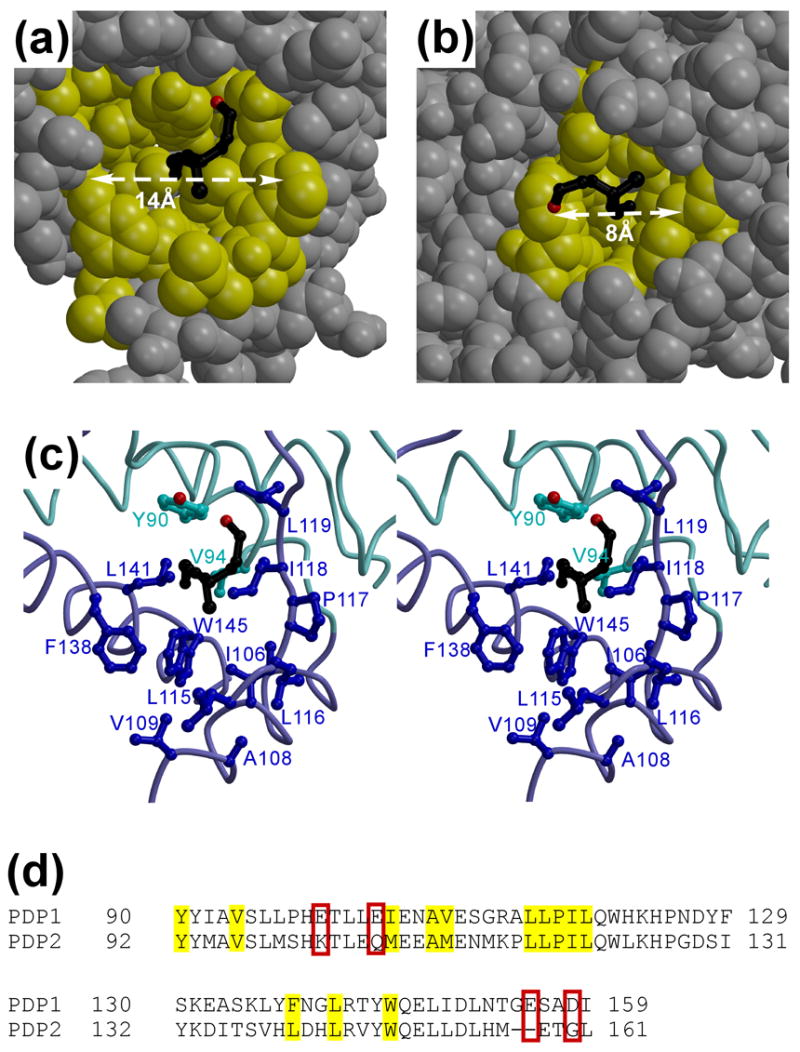

Figure 3. Putative lipoic acid binding site in the PDP1c structure.

(a, b) The van der Waals surface representation of the lipoic acid binding site in PDP1c (putative) (a) and PDHK (experimental21) (b). The hydrophobic residues lining the lipoic acid binding pockets are indicated in yellow, with the remainder of the PDP1c (a) and PDHK (b) structures colored in gray. The L2 modeled (a) and experimental (b) lipoyl moieties are shown as the black balls-and-sticks models. (c) The stereo view showing the details of the PDP1c putative lipoic acid binding cavity with the modeled lipoic acid (black). The PDP1c color scheme is the same as in Figure 1(a). (d) Sequence alignment of the PDP1 and PDP2 proteins in vicinity to the proposed lipoic acid binding site. The hydrophobic residues are marked by yellow color; the acidic residues (not conserved in PDP2) that might constitute the PDP1c portion of the PDP1c/L2 inter-molecular Ca2+ binding site(s) are outlined by the red boxes.

The region of PDP1c comprising the residues 244–279, termed flap, is poorly conserved in all the three phosphatases (Figure 2) and varies in length, secondary structure, and conformation. While the flap is still relatively similar in the crystal structures of PDP1c and PP2C, in the PstP phosphatase it adopts a strikingly different conformation that actually prompted its name (Figure 2(b)). At the same time, a third metal binding site was identified 5.6Å from the catalytic binuclear core in PstP, and two oxygen atoms from one serine residue in the flap were found to contribute to the coordination of the third metal ion. Other coordinating residues (in the PDP1c numbering) include two conserved aspartic residues (Asp220 and Asp347) and two water molecules. Since the third metal is relatively far from the binuclear core and does not change its coordination, the phosphatase is active and the crystals hydrolyze p-nitrophenyl phosphate13. Based on the PstP crystal structure, it was suggested that the flap may undergo similar conformational changes in other PPM phosphatases, and thus can potentially play some general regulatory role13. However, remodeling of the corresponding flap region in PDP1c to achieve the PstP configuration does not suggest any third metal-binding site. The coordinating serine residue in PstP is substituted for leucine in PDP1c, and no other residue(s) that could provide the coordinating bond(s) for the Mg2+ ion is apparent.

The catalytic sites of PDP1c, PP2C and PstP are nearly identical as judged by the superimpositions of their crystal structures. The binuclear core of PDP1c is, however, formed by the two Mg2+ ions, in place of the two Mn2+ ions in PP2C and PstP. The octahedral coordination of each metal ion of the core is established by three conserved aspartic acids, one conserved glycine, and five ordered water molecules, including one water molecule bridging the two metals. The coordination of one of the Mg2+ ion by the side chain of Glu230 from the symmetry related molecule in PDP1 is replaced by the water molecule in both PP2C and PstP. The results of the site-directed mutagenesis indicated that Asp60 and Asp239 are absolutely essential for catalysis in PP2C17. These residues correspond to the structurally conserved residues Asp73 and Asp347 in PDP1c. Moreover, Asp282 in PP2C (Asp445 in PDP1c) is also important for catalysis. Consistently, site-directed mutagenesis preformed in PDP1c18 revealed that Asp347 is absolutely essential whereas Asp445 is important for the catalysis. It was also shown that Asp54 (which does not interact directly with the Mg2+ ions) is catalytically important, probably because it makes stabilizing interactions with Asp73 and the two water molecules directly coordinating the metal ion. Asp54 corresponds to Asp38 in PP2C. Thus both structural and mutational analyses suggest that the dephosphorylation reaction follows the general mechanism proposed previously12; however some other residues in the catalytic site may vary according to specific species and/or target tissues.

Variations in the catalytic site

Both PDP1c and PP2C have a conserved His residue (His 75 in PDP1c) in the catalytic site, whereas PstP does not. The corresponding histidine residue in PP2C (His62) was proposed to act as a general acid that protonates the leaving group (peptide) at the final step of the protein dephosphorylation reaction; indeed, the His62Ala mutation dramatically decreased the PP2C activity17. In contrast to PP2C, PstP and some other phosphatases, PDP1c in vertebrates does not conserve Arg33 that is hydrogen bonded to the phosphate ion in the PP2C crystal structure12. In PDP1c, this arginine is substituted for uncharged asparagine (Asn49) whose side chain (based on the superimposition) is distant from the phosphate ion. Thus the same interaction that was thought to mediate binding of the substrate phosphate group seems unlikely in PDP1c, as there is no other arginine or lysine that could interact with the phosphate without major conformational changes of the protein backbone. Consistently, mutation of Asn49 to alanine did not seriously impair the PDP1c catalytic activity18. We speculate that, since His75 may be positively charged,17 it may bind the substrate phosphate group in PDP1c upon reorientation of the side chain. The role of His75 as a general acid seems questionable, in particular because in the PstP phosphatase it is substituted for methionine and there is no other histidine in the catalytic site13. Although the fine details of the dephosphorylation catalytic mechanism are still the subject of the further studies, the two Mg2+/Mn2+ ions coordinated by conserved aspartic residues and glycine main chain seem indispensable for the catalysis in the PPM phosphatases.

Implications for the PDP1/PDC assembly

The binding of the L2-domain of E2 to PDP1c is Ca2+-dependent and is mediated by the lipoic acid covalently attached to the Lys residue of L28, 19. In the absence of Ca2+, PDP1c cannot form the stable complex with E2, resulting in substantial loss of the PDP1c catalytic activity9. Interestingly, while the PDP1c/L2 complex has high affinity to Ca2+ ions, PDP1c and L2 alone do not bind calcium8. These data suggest that PDP1c likely possesses the two major binding sites: (i) a presumably hydrophobic site that accommodates the lipoyl moiety of E2, and (ii) an acidic patch that would complement the L2 residues to achieve the Ca2+ specificity.

Whereas the location of the inter-molecular Ca2+ binding site in PDP1c is difficult to predict in the absence of the direct structural data on the PDP1c/L2 complex, the intra-molecular lipoic acid binding site in PDP1c could be proposed based on the PDP1c structure alone assuming likely similarity to PDHK, for which the complex structures with the L2-domain are available20, 21. Indeed, the size, shape and hydrophobic nature of the PDHK pocket in which the L2 lipoyl moiety is inserted impose rather strong restraints on the structural properties of the corresponding PDP1c binding site (Figure 3(b)). The inspection of the PDP1c structure revealed only one hydrophobic cavity that is reminiscent of the PDHK lipoic acid binding site (Figure 3(a) and (c)). Importantly, the structures of homologous phosphatases (see above) that lack specificity to PDC and therefore unlikely bind to the L2-domain.

Our modeling of the lipoic acid binding to PDP1c is, however, compromised by the fact that the PDP1c residues forming the hypothetical binding site are highly conserved in PDP2, which does not bind the L2-domain3, 18 (Figure 3(d)). There are two possible explanations for this contradiction. First, in view of the apparent lack of the alternative lipoic acid binding site in the experimentally resolved portion of the PDP1c structure, one may presume that the binding site is formed by flexible structural segments disordered in the crystal. Indeed, the fragment comprising the residues 407–443 (not resolved in the PDP1c structure) seems long enough to form an alternative lipoic acid binding site upon folding. However, this region is as well conserved between the PDP1 and PDP2 as the proposed binding site motif (data not shown). We therefore favor the second possibility, in which structural alterations induced by the relatively subtle sequence differences between PDP1 and PDP2 may determine affinities of these proteins to the L2-domain. Based on the structural, functional and sequence analysis we suggest one plausible hypothesis. Structural comparison shows that, although the PDP1c putative lipoic acid hydrophobic binding site closely resembles that of PDHK in shape and amino acid configuration, it appears substantially more open (~14 × 12Å in PDP1c vs 8 × 8Å in PDHK, Figure 3(a) and (b)). Therefore, a closure of the PDP1c cavity may be required to provide tight binding and specific recognition of the lipoyl moiety; this closure may be achieved through the subtle rotation (~10–15°) of the α4 and/or α5 helices towards the modeled lypoic acid. It is worth noting that these α-helices are likely mobile, as they are located on the surface of the molecule and are connected to the rest of the protein through flexible loops that appear partially disordered in the crystal structure. Given the Ca2+-dependent mode of the L2 recruitment to PDP1c, we speculate that these structural rearrangements may be triggered by the binding of the Ca2+ ion(s) whose affinity to PDP1c would be dramatically increased through formation of the PDP1c/L2 intermolecular Ca2+ binding site(s). This hypothesis suggests, in particular, that PDP2 (that possesses no affinity to calcium) while likely maintaining the lipoic acid binding site in its open configuration (Figure 3(d)) cannot isomerize to the closed state required for the L2 binding because of the absence of the Ca2+ binding residues. The proposed Ca2+-dependent mechanism of the PDP1c/L2 association appears very similar to that of the troponin complex, which regulates muscle contraction in the Ca2+-dependent manner. Indeed, the binding of the Ca2+ ion to the EF-hand of the N-terminal regulatory domain of troponin C occurring only at the high Ca2+ concentrations induces structural rearrangements (involving, in particular, rotation of the α-helices) in this domain, resulting in the closure of the hydrophobic cavity to allow for the specific binding of the regulatory amphipathic α-helix of troponin I22, 23. Subsequently, dissociation of the Ca2+ ion from the troponin C N-terminal domain upon decrease of the Ca2+ concentration triggers opening of the hydrophobic cavity and release of the troponin I α-helix.

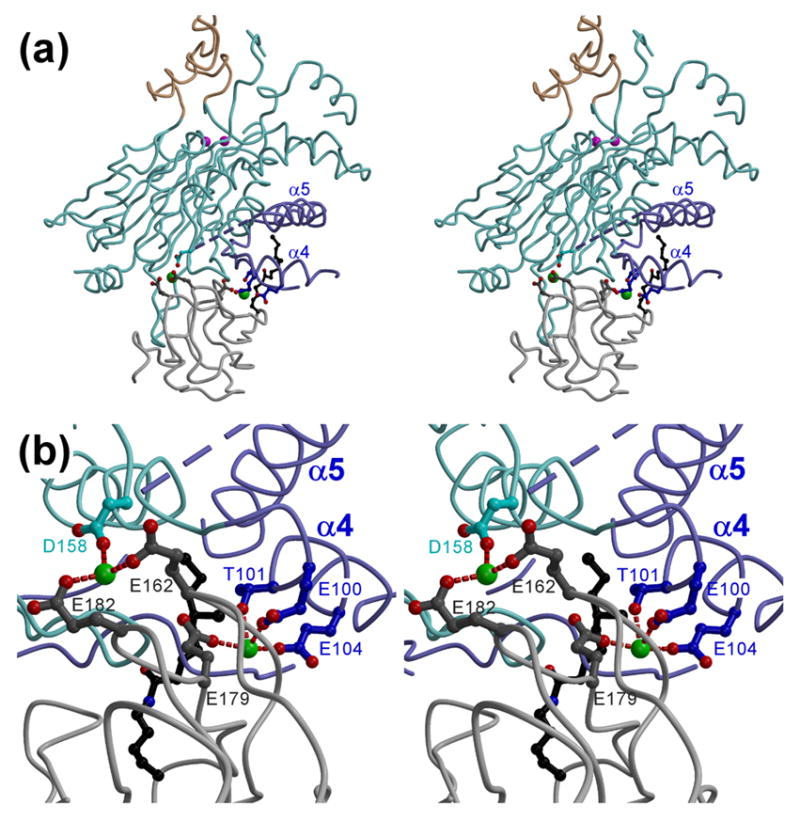

To provide additional insight in the mechanism of the PDP1c/L2 binding and to identify the acidic amino acids that might constitute the PDP1c portion of the Ca2+ binding site(s), we have constructed a rough structural model of the PDP1c/L2 complex (Figure 4) that matches the following criteria. First, the L2 lipoyl moiety is inserted into the proposed hydrophobic pocket on the PDP1c surface. Second, no significant alterations of the PDP1c and L2 structures were made during the modeling. Third, there are no steric clashes between the PDP1c and L2 structures in the model. Finally, assuming the closure of the lipoic acid binding site via the Ca2+-induced movement of the α4 and/or α5 helices the L2 Ca2+ ligands previously proposed based on the results of site-directed mutagenesis (Glu162, Glu179 and Glu182) were positioned in close proximity to these PDP1c structural elements. The final model suggests the two distinct yet spatially adjacent PDP1c regions that, together with the identified L2 acidic residues, may constitute two alternative/complementary Ca2+ regulatory binding sites. First, the N-terminus of α4 helix appears proximal to the L2 Glu 179 side chain and contains the three potential Ca2+ ligands (Glu100, Thr101 and Glu104) (Figure 4(b)), of which two, Glu100 and Glu104 are substituted for Lys and Gln in PDP2, respectively (Figure 3(d)) that would be incapable of the Ca2+ binding. Second, the loop intervening between the α5 and α6 helices that is partially disordered in the PDP1c structure is approaching the Glu 162 and Glu 182 residues of L2 (Figure 4(b)). This segment, which in PDP1c contains the two acidic residues (Glu 155 and Asp 158) and polar Ser 156, is most poorly conserved between PDP1 and PDP2. According to the sequence alignment (Figure 3(d)), in PDP2 this loop has the two-residue deletion and the substitution of Asp158 for Gly, a change that seems incompatible with the formation of the Ca2+ binding site.

Figure 4. Hypothetical model of the PDP1c/L2 complex.

(a) The overall stereo view. The L2 backbone, potential Ca2+ ligands, and lysine-lipoyl moiety are colored in light gray, dark gray, and black, respectively. The color scheme for the PDP1c molecule is the same as in Figure 1(a). The PDP1c acidic side chains that are proximal to those of L2 and may constitute the inter-molecular Ca2+ binding site are shown. The two alternative/complementary Ca2+ ions (green spheres) are shown just for reference to underscore the proximity to the L2 and PDP1c acidic residues; their positions should not be considered to indicate the actual locations of the Ca2+ ions in the PDP1c/L2 complex. (b) Close-up stereo view of the complex interface near the putative Ca2+ binding site(s). Distances between the protein side chains and the putative Ca2+ ions are marked by the red dashed lines.

In conclusion, though in the absence of the supporting biochemical data the model of the PDP1c/L2 complex remains purely hypothetical and by no means can be used for the structural analysis at the atomic level, it generates several important functional predictions that can be tested through the limited set of focused biochemical experiments. This model therefore provides a starting point for the future functional and structural studies of the mechanisms of the PDP1 action and its regulation. The more detailed understanding of these mechanisms awaits the determination of the experimental crystal structure of the ternary PDP1c/L2/Ca2+ complex.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. I. Artsimovitch for the helpful discussions and Dr. A. Perederina for assistance in crystallization, data collection and model building. This work was supported in part by the University of Alabama at Birmingham and by the NIH grants GM74252 and GM74840 to DGV. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Energy Research under contract No. W-31-109-Eng-38.

Abbreviations used

- PDC

pyruvate dehydrogenase complex

- E1

pyruvate dehydrogenase

- E2

dihydrolipoyl acetyltransferase

- E3

dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase

- PDP

pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase

- PDP1r

regulatory subunit of PDP

- PDP1c

catalytic subunit of PDP

- PP2C

protein phosphatase 2C

- PstP

protein serine/threonine phosphatase

- RMSD

root mean square deviation

- PDHK

pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase

Footnotes

Protein Data Bank Accession code

The coordinates and structure factors for the PDP1c crystal structure have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession code XXX.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Patel MS, Roche TE. Molecular biology and biochemistry of pyruvate dehydrogenase complexes. FASEB J. 1990;4:3224–3233. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.4.14.2227213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowker-Kinley MM, Davis WI, Wu P, Harris RA, Popov KM. Evidence for existence of tissue-specific regulation of the mammalian pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. Biochem J. 1998;329 ( Pt 1):191–196. doi: 10.1042/bj3290191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang B, Gudi R, Wu P, Harris RA, Hamilton J, Popov KM. Isoenzymes of pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase. DNA-derived amino acid sequences, expression, and regulation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17680–17688. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teague WM, Pettit FH, Wu TL, Silberman SR, Reed LJ. Purification and properties of pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase from bovine heart and kidney. Biochemistry. 1982;21:5585–5592. doi: 10.1021/bi00265a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linn TC, Pettit FH, Reed LJ. Alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase complexes. X. Regulation of the activity of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex from beef kidney mitochondria by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1969;62:234–241. doi: 10.1073/pnas.62.1.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hucho F, Randall DD, Roche TE, Burgett MW, Pelley JW, Reed LJ. -Keto acid dehydrogenase complexes. XVII Kinetic and regulatory properties of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase and pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase from bovine kidney and heart. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1972;151:328–340. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(72)90504-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Denton RM, Randle PJ, Martin BR. Stimulation by calcium ions of pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphate phosphatase. Biochem J. 1972;128:161–163. doi: 10.1042/bj1280161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turkan A, Hiromasa Y, Roche TE. Formation of a complex of the catalytic subunit of pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase isoform 1 (PDP1c) and the L2 domain forms a Ca2+ binding site and captures PDP1c as a monomer. Biochemistry. 2004;43:15073–15085. doi: 10.1021/bi048901y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan J, Lawson JE, Reed LJ. Role of the regulatory subunit of bovine pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:4953–4956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barford D, Das AK, Egloff MP. The structure and mechanism of protein phosphatases: insights into catalysis and regulation. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1998;27:133–164. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.27.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawson JE, Niu XD, Browning KS, Trong HL, Yan J, Reed LJ. Molecular cloning and expression of the catalytic subunit of bovine pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase and sequence similarity with protein phosphatase 2C. Biochemistry. 1993;32:8987–8993. doi: 10.1021/bi00086a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Das AK, Helps NR, Cohen TW, Barford D. Crystal structure of the protein serine/threonine phosphatase 2C at 2.0 A resolution. EMBO J. 1996;15:6798–6809. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pullen KE, Ng HL, Sung PY, Good MC, Smith SM, Alber T. An alternate conformation and a third metal in PstP/Ppp, the M. tuberculosis PP2C-Family Ser/Thr protein phosphatase. Structure. 2004;12:1947–1954. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Symersky J, Perederina A, Vassylyeva MN, Svetlov V, Artsimovitch I, Vassylyev DG. Regulation through the RNA polymerase secondary channel. Structural and functional variability of the coiled-coil transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1309–1312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500405200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perederina A, Svetlov V, Vassylyeva MN, Tahirov TH, Yokoyama S, Artsimovitch I, Vassylyev DG. Regulation through the secondary channel--structural framework for ppGpp-DksA synergism during transcription. Cell. 2004;118:297–309. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nowotny M, Gaidamakov SA, Crouch RJ, Yang W. Crystal structures of RNase H bound to an RNA/DNA hybrid: substrate specificity and metal-dependent catalysis. Cell. 2005;121:1005–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson MD, Fjeld CC, Denu JM. Probing the function of conserved residues in the serine/threonine phosphatase PP2Calpha. Biochemistry. 2003;42:8513–8521. doi: 10.1021/bi034074+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karpova T, Danchuk S, Huang B, Popov KM. Probing a putative active site of the catalytic subunit of pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase 1 (PDP1c) by site-directed mutagenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1700:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turkan A, Gong X, Peng T, Roche TE. Structural requirements within the lipoyl domain for the Ca2+-dependent binding and activation of pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase isoform 1 or its catalytic subunit. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:14976–14985. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108434200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kato M, Chuang JL, Tso SC, Wynn RM, Chuang DT. Crystal structure of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 3 bound to lipoyl domain 2 of human pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. EMBO J. 2005;24:1763–1774. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devedjiev Y, Steussy CN, Vassylyev DG. Crystal structure of an asymmetric complex of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 3 with lipoyl domain 2 and its biological implications. J Mol Biol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.04.083. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vassylyev DG, Takeda S, Wakatsuki S, Maeda K, Maeda Y. Crystal structure of troponin C in complex with troponin I fragment at 2.3-A resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:4847–4852. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.4847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takeda S, Yamashita A, Maeda K, Maeda Y. Structure of the core domain of human cardiac troponin in the Ca(2+)-saturated form. Nature. 2003;424:35–41. doi: 10.1038/nature01780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yeates TO. Detecting and overcoming crystal twinning. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:344–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collaborative Computational Project Number & 4. The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard M. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr A. 1991;47 ( Pt 2):110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]