Abstract

In humans and laboratory animal models, vulnerability to alcohol abuse is influenced by endogenous factors such as genotype. Using the inbred Fischer and Lewis rat strains, we previously reported stronger conditioned taste aversions (CTA) in male Fischer rats that could not be predicted by genotypic differences in alcohol absorption [34]. The present study made similar assessments in Fischer and Lewis females via four-trial CTA induced by 1 or 1.5 g/kg intraperitoneal (IP) ethanol (n = 10-12/strain/dose) as well as measures of blood alcohol concentrations (BAC) at 15, 60 and 180 min post-injection with 1.5 g/kg IP ethanol or saline (n = 7-8/strain/dose). Dose-dependent CTAs were produced, but the strains did not differ from each other in these measures; however, BACs in the Lewis females were significantly higher than Fischer at all three time points. As with males of the Fischer and Lewis genotypes, a dissociation between BACs and the aversive effects of alcohol was observed. These data are the first assessments of these particular phenotypes in Fischer and Lewis females, and when considered with the historical data, suggest a Genotype × Sex interaction in the centrally-mediated sensitivity to alcohol's aversive effects.

Keywords: Fischer, Lewis, alcohol, female, conditioned taste aversion, blood alcohol, hypothermia, sex differences

Introduction

Alcohol is one of the most widely abused drugs in the world, as well as the most prevalent topic of the substance dependence disorders [19,21]. As with other drugs of abuse, the development of alcohol abuse and dependence are influenced by a number of biological factors, including genetics. Human epidemiological research consistently reveals significant heritability of alcohol abuse and alcoholism [11], and recent advances in molecular biology have enabled the search for molecular genetic risk factors in humans and in non-human primate models [1,2,30]. In addition to these correlational approaches, laboratory researchers also utilize a variety of experimental methodologies to better understand genetic contributions to addiction. A particularly useful tool in this regard is the study of selectively bred lines and inbred strains of rodents [7], and the systematic comparison between the inbred Fischer (F344) and Lewis (LEW) rat strains is emerging as a valid approach for exploring genetic influences on drug abuse vulnerability.

Fischer and Lewis rats sometimes exhibit markedly divergent biobehavioral profiles in response to drugs of abuse, including alcohol [22,32]. At the behavioral level, Suzuki and colleagues [40] reported significantly greater alcohol consumption by body weight in Lewis rats across a range of concentrations within an operant oral self-administration preparation. However, Taylor et al. [42] reported greater intake in Fischer rats during the second week of a 5% ethanol-only diet, but this strain effect was only evident among the males. Taylor et al. also identified a number of differences in withdrawal-induced body temperature regulation and spontaneous locomotor activity, but as with the ethanol consumption, these effects were both strain- and sex-dependent. It is interesting to note that the interactions revealed by Taylor et al. [42] could not be predicted given the virtually exclusive study of male Fischer and Lewis responses to alcohol (also see [4,29,37]). Although their report focused on dependence and withdrawal after forced access (which may account for the discrepancy between their findings and the free operant work of Suzuki et al. [40], also see [41]), their data still underscore the importance of both genotype and biological sex in animal models of alcohol abuse (cf. [5,24]).

In addition to the self-administration work described above, our laboratory recently reported an assessment of several motivational and physiological responses to alcohol in male Fischer and Lewis rats [34]. Although no significant place conditioning effects emerged in either strain (as is common with rats, see [12]), the Fischer animals were more sensitive than Lewis subjects to the aversive effects of 1.25 and 1.5 g/kg IP ethanol within a conditioned taste aversion design (CTA; see [6,14,35]). Despite these effects of genotype on CTA, the strains did not differ in peak blood alcohol concentrations following a 1 or 1.5 g/kg injection, while neither strain exhibited a significant hypothermic response to a 1.5 g/kg ethanol challenge.

The pattern of male Lewis rats showing stronger alcohol-seeking behavior and weaker CTA is consistent with other work showing an inverse relationship between ethanol's aversive and reinforcing effects in various alcohol preferring and non-preferring rodents [32], and implies a centrally-mediated, genetically influenced dissociation between the physiological and aversive effects of alcohol in the Fischer and Lewis rat strains. However, aside from the work of Taylor et al. [42], we are not aware of any direct comparisons of alcohol-induced phenotypes in females of these strains. Given the increasing emphasis on the biological bases of drug abuse in females [20,25,26,27,43], the purpose of the present study was to contribute relevant data on alcohol in Fischer and Lewis rats. Specifically, adult female animals of both strains were tested under the same CTA design at doses previously reported in males [34], where consumption of a novel saccharin solution was immediately followed by IP injection of 1 or 1.5 g/kg ethanol over multiple conditioning trials. Additional females were administered a 1.5 g/kg dose with blood samples taken at multiple points thereafter. Together, these assessments provide novel parametric data on the aversive and pharmacokinetic effects of alcohol within the Fischer-Lewis model.

Method

Subjects and Housing

A total of 76 alcohol-naïve adult female rats served as subjects; 38 were of the Fischer strain (F344/SsNHsd) and 38 were of the Lewis strain (LEW/NH). The strains' respective weights (mean ± SD) at the start of the study were 189 ± 16 g and 217 ± 14 g. All animals were individually housed in hanging wire-mesh cages (24 × 19 × 18 cm) and had ad libitum access to food and water in the home cage; fluid access for animals involved in the CTA experiment is described in detail below. Animal housing rooms operated on a 12-h light/dark schedule (lights on at 0800h) and were maintained at an ambient temperature of 23°C. Estrous cycles were not actively monitored; however, all subjects from each experiment were housed within the same room to promote estrous synchrony through olfactory and pheromonal cues ([28], but see [36]). All procedures were conducted between 1000h and 1600h and were in compliance with the US Animal Welfare Act and National Research Council guidelines as well as standards established by the Animal Care and Use Committee at American University.

Drugs and Solutions

Ethanol stock and sodium saccharin were both obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Ethanol was combined with saline into a 15% solution (v/v) and administered via IP injection at doses of 0, 1 or 1.5 g/kg, depending on the experiment. All non-drug saline injections were also administered IP and were equivolume to the respective ethanol dose. Saccharin was prepared as a 1 g/L (0.1 %) solution in tap water.

Alcohol-Induced CTA

Habituation

Subjects involved in the CTA experiment were given 20-min access to water daily until fluid consumption and weights stabilized. During all CTA-related procedures, fluid was presented in inverted 50 ml graduated Nalgene tubes sealed by rubber stoppers fitted with stainless steel spouts; individual consumption was measured to the nearest 0.5 ml.

Conditioning

On Day 1, subjects were given 20-min access to the saccharin solution instead of water. Immediately after this period, each rat was individually transported to a nearby room and injected with its randomly assigned dose of 1 or 1.5 g/kg IP ethanol (n = 11-12 per combination of strain and dose). On Day 2, the animals were given access to water for the 20-min period, followed immediately by a saline injection equivolume to their respective ethanol dose. This pattern of 20-min saccharin access followed by ethanol injection on Day 1 followed by 20-min water access and saline injection on Day 2 constituted one conditioning cycle. The CTA procedure was carried out for three consecutive cycles over 6 days, with a fourth saccharin exposure on Day 7 as a final test of alcohol-induced CTA.

Previous CTA work from our laboratory with female Fischer and Lewis rats has consistently shown equivalent and stable saccharin consumption across trials in exclusively vehicle-treated control groups [13,15,23]. Therefore, in order to maximize sample size of the alcohol-treated groups, vehicle controls were not included in the present study. The effect of dose was still amenable to between-groups comparisons, but given ethanol's well-documented aversive effects [8], CTA within any given group was defined as the significant decrease in mean saccharin consumption relative to the first saccharin exposure. The high 1.5 g/kg dose was chosen for the present study based on its previously reported ability to differentiate males of these strains in an identical CTA paradigm [34], whereas the low 1 g/kg dose that did not differentiate the males was used to allow a unique sensitivity to the aversive effects of alcohol in female Fischer or Lewis animals to emerge.

Blood Alcohol Assessment

Following the CTA experiment, additional female Fischer and Lewis rats were randomly assigned to receive IP injections of 1.5 g/kg ethanol (n = 8 per strain) or equivolume saline (n = 7 per strain). Tail blood samples were obtained at 15, 60 and 180 min post-injection. Before the 15-min sampling, each rat's tail was soaked in warm water for 60-75 sec and wiped dry with a paper towel. The rat was then held in an oversized restraint tube (Plas-Labs, Lansing, MI) while approximately 1 mm of the tip of the tail was cut with surgical scissors. For subsequent samplings, the tail was re-soaked and dried, but no further incisions were made and the restraint tube was employed on an as-needed basis. For all samplings, approximately 40-90 μl of whole blood were collected in heparinized capillary tubes (Drummond Scientific, Broomall, PA) and the contents immediately transferred to microcentrifuge vials. Each sample was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 20 min; the plasma was then transferred via micropipette to new vials and kept frozen until ready for assay. Undiluted plasma was assayed using the HP 6890 Series headspace gas chromatography/mass spectrometry system (Hewlett-Packard, Palo Alto, CA) based on protocols developed in-house by the Laboratory of Clinical and Translational Studies at the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Data Presentation and Analysis

Data for the CTA experiment were excluded from one Fischer animal in the 1.5 g/kg group that died during the experiment. For the CTA analyses, the groups were composed as follows: Fischer 1 g/kg, n = 12; Fischer 1.5 g/kg, n = 10; Lewis 1 g/kg, n = 12; and Lewis 1.5, n = 11. The CTA data were analyzed and presented as raw milliliters of fluid consumed, and all blood alcohol concentrations (BAC) were expressed in milligrams per deciliter of plasma (mg/dl).

For all procedures, statistical analyses were conducted via analyses of variance (ANOVA), Tukey-corrected post-hoc comparisons and independent and paired-samples t-tests. These and all other analyses are described in detail below. Statistical significance for all analyses was set at α = .05 (two-tailed when applicable).

Results

Alcohol-Induced CTA

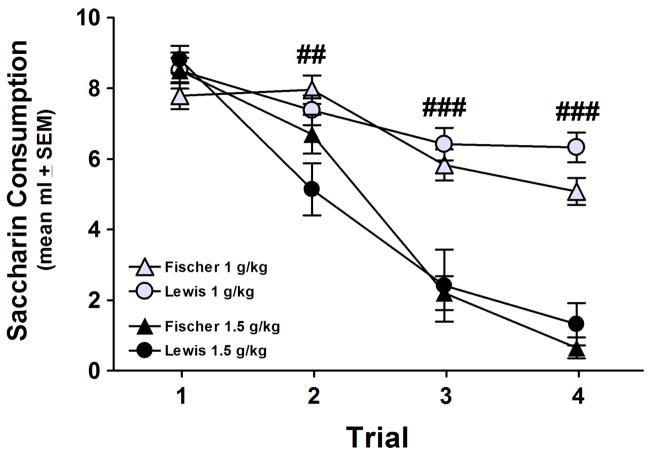

A 4 × 2 × 2 mixed ANOVA with a repeated-measures factor of Trial (1, 2, 3 and 4) and between-groups factors of Strain (Fischer and Lewis) and Dose (1 and 1.5 g/kg) was performed on the raw saccharin consumption data. This analysis yielded significant effects of Trial and Dose and a significant Trial × Dose interaction (Fs > 32.80, ps < .001); the only term involving Strain to achieve significance was an interaction with Trial (F(3,123) > 4.70, p < .01). Collapsing the data across strains, independent samples t-tests at each trial confirmed significantly less saccharin consumption in the 1.5 g/kg group compared to the 1 g/kg group on Trials 2, 3 and 4 (t(43)s > 3.20, ps < .01; trial 1 t(43) < 1.30, p > .20). Paired-samples t-tests revealed that animals conditioned with 1.5 g/kg significantly decreased saccharin consumption after a single pairing with alcohol (t(20) > 5.00, p < .001), whereas the 1 g/kg animals required two pairings before a significant avoidance response emerged (Trial 1 vs. 2 t(23) < 1.40, p > .10; Trial 1 vs. 3 t(23) > 6.30, p < .001). As seen in Figure 1, an orderly dose-dependent response to the aversive effects of alcohol was produced, but there was no effect of genotype at either dose.

Figure 1.

Conditioned taste aversion (CTA) induced by 1 and 1.5 g/kg IP ethanol in female Fischer and Lewis rats (n = 10-12/strain/dose). Dose-dependent reductions in mean saccharin consumption (ml) across trials were observed; however, the magnitude of CTAs did not vary by strain. 1 versus 1.5 g/kg (collapsed across strain): ## p < .01, ### p < .001.

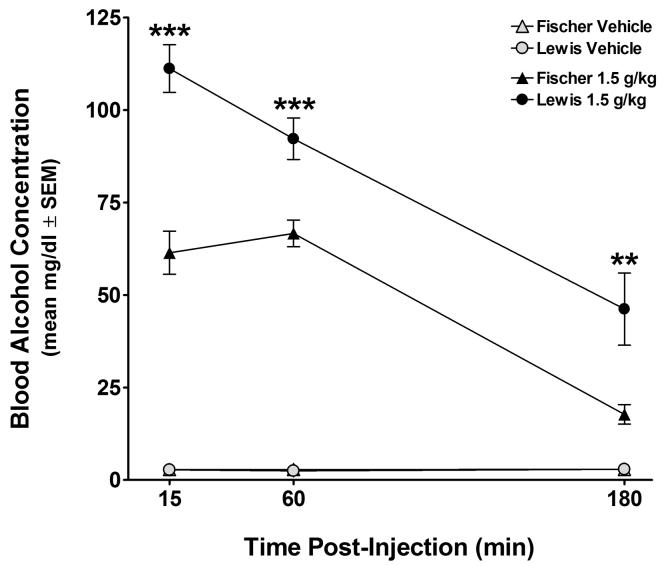

Blood Alcohol Assessment

A 3 × 2 × 2 mixed ANOVA with a repeated-measures factor of Time (15, 60 and 180 min post-injection) and between groups factors of Strain (Fischer and Lewis) and Dose (vehicle and 1.5 g/kg) was performed on the blood alcohol concentration (BAC) values. All terms in this analysis were significant (Fs > 3.40, ps < .05), including the Time × Strain × Dose interaction. Tukey-corrected post-hoc comparisons at each time point confirmed significantly higher BACs in the alcohol-treated groups of both strains compared to their vehicle-treated counterparts at 15 and 60 min post-injection (ps < .001), but unlike the Fischer animals (p > .20), BACs in the alcohol-treated Lewis rats still differed from their controls at 180 min (p < .001). Although BACs among the alcohol-treated Fischer rats did not change from 15 to 60 min (paired-samples t(7) < 1.40, p > .20) and decreased significantly from 60 to 180 min (t(7) > 16.60, p < .001), BACs steadily decreased across adjacent time points in the alcohol-treated Lewis animals (t(7)s > 4.30, ps < .01). As seen in Figure 2, BAC levels in the Lewis strain were significantly higher than those of their Fischer counterparts at all three time points (Tukey-corrected ps < .01).

Figure 2.

Mean ± SEM blood alcohol concentrations (BAC; mg/dl) in female Fischer and Lewis rats at 15, 60 and 180 min following IP injection of 1.5 g/kg ethanol or equivolume saline (n = 7-8/strain/dose). Mean BACs in the alcohol-treated Lewis rats were significantly higher than their alcohol-treated Fischer counterparts at all three time points (**p < .01, ***p < .001).

Discussion

The present study revealed expected dose-dependent responses to alcohol's aversive effects via CTA, with respective saccharin consumption reduced to approximately 70% and 12% of baseline after three pairings with 1 and 1.5 g/kg IP ethanol. However, this effect did not vary by genotype, as both the Fischer and Lewis rats exhibited similar avoidance responses at both doses. In contrast, the blood alcohol measures were strongly affected by genotype, with significantly higher BACs in the Lewis animals up to 3 hours after the initial 1.5 g/kg ethanol injection.

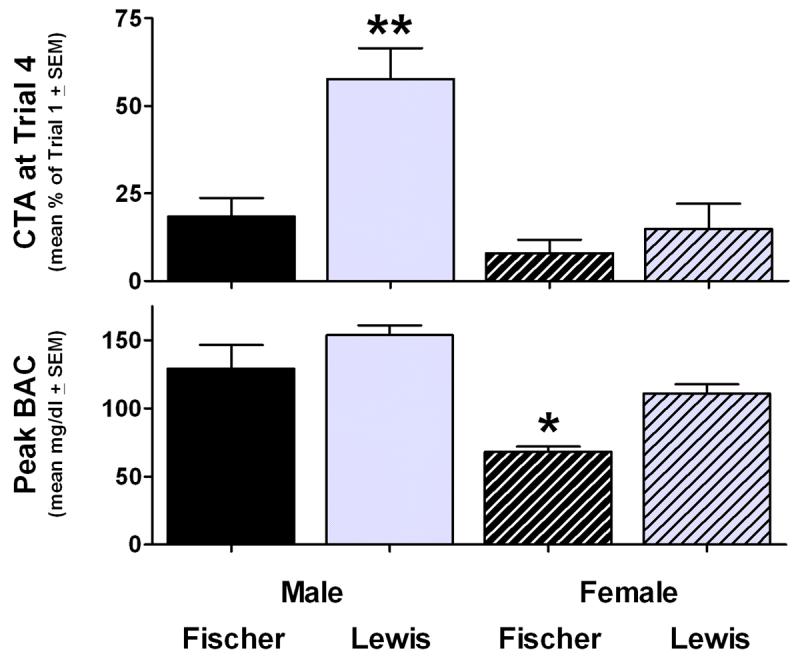

While it has been suggested that high BACs are necessary for the development of ethanol CTA [10], the fact that the Fischer animals exhibited equivalent aversions to their Lewis counterparts despite much lower BACs indicates that the strength of alcohol-induced CTA is not directly correlated with ethanol absorption (as has been suggested with BACs and ethanol-induced sleep in these strains [41]). An apparent dissociation between the physiological and aversive effects of alcohol was also observed in male Fischer and Lewis rats [34], but the nature of these effects differed from that seen in females from the present study. Among the males, the Lewis rats were less sensitive to the aversive effects of 1.5 g/kg IP ethanol, and BACs did not differ between the strains at any time point (although a significant main effect of strain in peak BACs was observed). However, Fischer and Lewis females developed equally significant responses to the aversive effects of the same 1.5 g/kg dose despite the nearly two-fold higher BACs in the Lewis animals at some points. To further illustrate this dissociation and a potential role of sex differences, Figure 3 presents phenotypes produced by 1.5 g/kg IP ethanol assessed under identical conditions by our laboratory in both the present study and in Roma et al. [34]. Given the sex and strain differences in raw baseline consumption, the Trial 4 CTA data were transformed to a percentage of Trial 1 consumption, while the blood alcohol data represent the mean individual peak BACs regardless of time point (15, 60 or 180 min post-injection). Tukey-corrected comparisons confirmed that the weakest CTAs were in the male Lewis animals (ps < .01) and the lowest BACs were in the female Fischer animals (ps < .05). Clearly, BAC does not predict CTA in these strains, and neither genotype nor biological sex alone is sufficient to explain these data. Although the nature of the dissociation between ethanol absorption and CTA in these strains remains unknown, when considered together, the data from our laboratory suggest a Genotype × Sex interaction in alcohol's aversive effects that cannot be accounted for by the peripheral physiological consequences of ethanol administration.

Figure 3.

Genotype × Sex interaction in the aversive and physiological effects of 1.5 g/kg IP ethanol in male and female Fischer and Lewis rats. Top panel: mean ± SEM saccharin consumption at Trial 4 relative to baseline (Trial 1). Bottom panel: mean ± SEM peak blood alcohol concentrations (mg/dl) at either 15, 60 or 180 min post-injection. * p < .05, ** p < .01 versus all three other groups. Data from the males adapted from Roma et al. (2006) [34].

Given the results of the present study, three issues that strike us as particularly worthy of future investigation are 1) identifying the biological substrate(s) mediating the effects of genotype on the aversive properties of alcohol, 2) how such effects may ultimately impact drug self-administration and 3) how environmental influences may interact with biological factors to affect alcohol-induced phenotypes in brain and behavior. In terms of underlying mechanisms, the dissociation between ethanol absorption and ethanol-induced CTA suggests neurobiological mediation at the level of the brain. Unlike morphine and cocaine [18], we are not aware of any published reports of aversion-related brain area activation induced by systemic alcohol administration in Fischer and Lewis rats of either sex, but such an assessment would certainly be of interest in light of the existing data. The relationship between alcohol-induced CTA and self-administration has been extensively explored in a number of selectively bred lines and inbred strains of rodents, and the general relationship observed is one where weaker CTAs correspond to greater propensities to self-administer [3,32]. Although cumulative self-administered doses of alcohol in Fischer and Lewis rats [40] are comparable to those used in CTA, the relatively low unit dose in self-administration is likely less aversive than the large single doses of exogenously administered alcohol in CTA. Nonetheless, the inverse relationship between the phenotypes produced by both assays still holds true in males, but remains to be tested in females of these strains, which have not been assessed in any conventional preparation involving choice between ethanol and non-alcoholic alternatives. Finally, manipulation of the documented differences in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis regulation and stress reactivity [9,31,38,39] as well as differential effects of the Fischer and Lewis maternal environments [16,17,33] may prove valuable for developing tractable animal models of the complexity underlying human alcohol use and abuse.

In conclusion, the present study found no differences between female Fischer and Lewis rats in the acquisition of conditioned taste aversion induced by 1 or 1.5 g/kg IP ethanol; however, the Lewis animals achieved significantly higher blood alcohol levels than their Fischer counterparts after a 1.5 g/kg ethanol challenge. To the best of our knowledge, these data are the first direct comparisons between female Fischer and Lewis rats on these particular alcohol-induced phenotypes and reveal a dissociation between the aversive and pharmacokinetic effects of acute ethanol administration. When considered with identically collected data from male Fischer and Lewis rats, a Genotype × Sex interaction effect on the aversive properties of alcohol in these strains was suggested. Although the critical substrates for these effects remain unknown, the parametric data presented here may inform future investigations and yield further insights on the biobehavioral bases of alcohol use and abuse.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kyle Wibby for his assistance during the conditioning procedures. We are also indebted to Dr. Markus Heilig for generously providing access to the gas chromatography system and to Erick Singley for his expert technical assistance therein. This research was supported by a grant from the Mellon Foundation to A.L.R. and by intramural funds from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism/National Institutes of Health/Public Health Service/US Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Barr CS, Newman TK, Becker ML, Champoux M, Lesch KP, Suomi SJ, Goldman D, Higley JD. Serotonin transporter gene variation is associated with alcohol sensitivity in rhesus macaques exposed to early-life stress. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:812–817. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000067976.62827.ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr CS, Newman TK, Lindell S, Shannon C, Champoux M, Lesch KP, Suomi SJ, Goldman D, Higley JD. Interaction between serotonin transporter gene variation and rearing condition in alcohol preference and consumption in female primates. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:1146–1152. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadbent J, Muccino KJ, Cunningham CL. Ethanol-induced conditioned taste aversion in 15 inbred mouse strains. Behav Neurosci. 2002;116:138–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodie MS, Trifunović RD, Shefner SA. Serotonin potentiates ethanol-induced excitation of ventral tegmental area neurons in brain slices from three different rat strains. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;273:1139–1146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cailhol S, Mormède P. Conditioned taste aversion and alcohol drinking: strain and gender differences. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63:91–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conditioned Taste Aversion: An Annotated Bibliography. http://www.ctalearning.com.

- Crabbe JC. Genetic contributions to addiction. Annu Rev Psychol. 2002;53:435–462. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CL. If you want to understand alcohol abuse, you must also understand taste aversion conditioning. Retrieved March 13, 2007, from American University, Conditioned Taste Aversion: An Annotated Bibliography Web site: http://www.american.edu/academic.depts/cas/psych/Cunningham_Highlight.pdf.

- Dhabhar FS, McEwen BS, Spencer RL. Stress response, adrenal steroid receptor levels and corticosteroid-binding globulin levels−a comparison between Sprague-Dawley, Fischer 344, and Lewis rats. Brain Res. 1993;616:89–98. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90196-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckardt MJ. The role of orosensory stimuli from ethanol and blood-alcohol levels in producing conditioned taste aversion in the rat. Psychopharmacologia. 1975;44:267–271. doi: 10.1007/BF00428905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enoch M-A, Goldman D. The genetics of alcoholism and alcohol abuse. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2001;3:144–151. doi: 10.1007/s11920-001-0012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidler TL, Bakner L, Cunningham CL. Conditioned place aversion induced by intragastric administration of ethanol in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;77:731–743. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foynes MM, Riley AL. Lithium-chloride-induced conditioned taste aversions in the Lewis and Fischer 344 rat strains. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;79:303–308. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia J, Ervin FR. Gustatory-visceral and telereceptor-cutaneous conditioning: Adaptation in internal and external milieus. Commun Behav Biol. 1968;1:389–415. [Google Scholar]

- Glowa JR, Shaw AE, Riley AL. Cocaine-induced conditioned taste aversions: comparisons between effects in LEW/N and F344/N rat strains. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1994;114:229–232. doi: 10.1007/BF02244841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Serrano MA, Sternberg EM, Riley AL. Maternal behavior in F344/N and LEW/N rats: effects on carrageenan-induced inflammatory reactivity and body weight. Physiol Behav. 2002;75:493–505. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(02)00649-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Serrano M, Tonelli L, Listwak S, Sternberg E, Riley AL. Effects of cross fostering on open-field behavior, acoustic startle, lipopolysaccharide-induced corticosterone release, and body weight in Lewis and Fischer rats. Behav Genet. 2001;31:427–436. doi: 10.1023/a:1012742405141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabus SD, Glowa JR, Riley AL. Morphine- and cocaine-induced c-Fos levels in Lewis and Fischer rat strains. Brain Res. 2004;998:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hommer DW. Male and female sensitivity to alcohol-induced brain damage. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27:181–185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, Wittchen HU, Kendler KS. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TA, Ambrosio E. HPA axis function and drug addictive behaviors: insights from studies with Lewis and Fischer 344 inbred rats. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2002;27:35–69. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(01)00035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancellotti D, Bayer BM, Glowa JR, Houghtling RA, Riley AL. Morphine-induced conditioned taste aversions in the LEW/N and F344/N rat strains. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;68:603–610. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00461-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T-K, Lumeng L. Alcohol preference and voluntary alcohol intakes of inbred rat strains and the National Institutes of Health heterogeneous stock of rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1984;8:485–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1984.tb05708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch WJ. Sex differences in vulnerability to drug self-administration. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;14:34–41. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch WJ, Roth ME, Carroll ME. Biological basis of sex differences in drug abuse: Preclinical and clinical studies. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;164:121–137. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1183-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClearn GE. Sex distinctiveness in effective genotype. In: Galanter G, editor. Recent Developments in Alcoholism, vol 12: Women and Alcoholism. Plenum Press; New York: 1995. pp. 217–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClintock MK. Estrous synchrony and its mediation by airborne chemical communication (Rattus norvegicus) Horm Behav. 1978;10:264–276. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(78)90071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mocsary Z, Bradberry CW. Effect of ethanol on extracellular dopamine in nucleus accumbens: comparison between Lewis and Fischer 344 rat strains. Brain Res. 1996;706:194–198. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01200-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oroszi G, Goldman D. Alcoholism: genes and mechanisms. Pharmacogenomics. 2004;5:1037–1048. doi: 10.1517/14622416.5.8.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rex A, Sondern U, Voigt JP, Franck S, Fink H. Strain differences in fear-motivated behavior of rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1996;87:308–312. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)02128-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley AL, Davis CM, Roma PG. Strain differences in taste aversion learning: implications for animal models of drug abuse. In: Reilly S, Schachtman TR, editors. Conditioned Taste Aversion: Behavioral and Neural Processes. Oxford University Press; New York: in press. [Google Scholar]

- Roma PG, Davis CM, Riley AL. Effects of cross-fostering on cocaine-induced conditioned taste aversions in Fischer and Lewis rats. Dev Psychobiol. 2007;49:172–179. doi: 10.1002/dev.20168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roma PG, Flint WW, Higley JD, Riley AL. Assessment of the aversive and rewarding effects of alcohol in Fischer and Lewis rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;189:187–199. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0553-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozin P, Kalat JW. Specific hungers and poison avoidance as adaptive specializations of learning. Psychol Rev. 1971;78:459–486. doi: 10.1037/h0031878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schank JC. Do Norway rats (Rattus norvegicus) synchronize their estrous cycles? Physiol Behav. 2001;72:129–139. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(00)00395-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selim M, Bradberry CW. Effect of ethanol on extracellular 5-HT and glutamate in the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex: comparison between the Lewis and Fischer 344 rat strains. Brain Res. 1999;716:157–164. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01385-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg EM, Glowa JR, Smith MA, Calogero AE, Listwak SJ, Aksentijevich S, Chrousos CP, Wilder RI, Gold PW. Corticotropin releasing hormone related behavioral and neuroendocrine responses to stress in Lewis and Fischer rats. Brain Res. 1992;570:54–60. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90563-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stähr T, Szuran T, Welzl H, Pliska V, Feldon J, Pryce CR. Lewis/Fischer rat strain differences in endocrine and behavioural responses to environmental challenge. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;67:809–819. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, George FR, Meisch RA. Differential establishment and maintenance of oral ethanol reinforced behavior in Lewis and Fischer 344 inbred rat strains. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988;245:164–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Motegi H, Otani K, Koike Y, Misawa M. Susceptibility to, tolerance to, and physical dependence on ethanol and barbital in two inbred strains of rats. Gen Pharmacol. 1992;23:11–17. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(92)90040-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AN, Tio DL, Bando JK, Romeo HE, Prolo P. Differential effects of alcohol consumption and withdrawal on circadian temperature and activity rhythms in Sprague-Dawley, Lewis, and Fischer male and female rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:438–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiren KM, Hashimoto JG, Alele PE, Devaud LL, Price KL, Middaugh LD, Grant KA, Finn DA. Impact of sex: determination of alcohol neuroadaptation and reinforcement. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:233–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]