Abstract

Rationale: Bone marrow–derived cells have been shown to engraft during lung fibrosis. However, it is not known if similar cells engraft consequent to inhalation of asbestos fibers that cause pulmonary fibrosis, or if the cells proliferate and differentiate at sites of injury.

Objectives: We examined whether bone marrow–derived cells participate in the pulmonary fibrosis that is produced by exposure to chrysotile asbestos fibers.

Methods: Adult female rats were lethally irradiated and rescued by bone marrow transplant from male transgenic rats ubiquitously expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP). Three weeks later, the rats were exposed to an asbestos aerosol for 5 hours on three consecutive days. Controls were bone marrow–transplanted but not exposed to asbestos.

Measurements and Main Results: One day and 2.5 weeks after exposure, significant numbers of GFP-labeled male cells had preferentially migrated to the bronchiolar-alveolar duct bifurcations, the specific anatomic site at which asbestos produces the initial fibrogenic lesions. GFP-positive cells were present at the lesions as monocytes and macrophages, fibroblasts, and myofibroblasts or smooth muscle cells. Staining with antibodies to PCNA demonstrated that some of the engrafted cells were proliferating in the lesions and along the bronchioles. Negative results for TUNEL at the lesions confirmed that both PCNA-positive endogenous pulmonary cells and bone marrow–derived cells were proliferating rather than undergoing apoptosis, necrosis, or DNA repair.

Conclusions: Bone marrow–derived cells migrated into developing fibrogenic lesions, differentiated into multiple cell types, and persisted for at least 2.5 weeks after the animals were exposed to aerosolized chrysotile asbestos fibers.

Keywords: bone marrow, progenitor cell, asbestosis, fibrosis

AT A GLANCE COMMENTARY

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Bone marrow cells have been described to be involved in bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis, but their role in asbestos-induced fibrosis is unknown.

What This Study Adds to the Field

Specific migration and engraftment of nonhematopoietic bone marrow progenitors to asbestos lesions occurs in the lung. Some of these cells proliferate and differentiate into multiple cell types.

Interstitial pulmonary fibrosis can be caused by a number of inhaled agents (1). One well-known fibrogenic agent is the mineral asbestos, and we and others have developed a well-characterized model of asbestos-induced lung fibrosis in rats (2) and mice (3, 4). This model system has allowed the identification of a number of growth factors (5) and oxygen radicals (6) that are likely to play roles in the development of the disease. Macrophages are the only inflammatory cells that respond after a brief exposure (7), and both the epithelial and mesenchymal cell populations exhibit significant increases in proliferation (3, 8) and cell numbers (2, 9). In rats, superoxide dismutase administered by osmotic pumps has ameliorated the disease (10), and knocking out the genes that code for the tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α receptors prevents the development of asbestos-induced lung fibrosis in mice (11). Millions of individuals worldwide are afflicted by interstitial pulmonary fibrosis, yet there are no effective therapies (12).

Recently, there has been growing interest in adult bone marrow–derived cells that can act as progenitor cells in replacing and/or repairing injured tissues (13, 14). In the experiments reported here, we transplanted bone marrow from male transgenic rats ubiquitously expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) into female rats before asbestos exposure. We then examined the bronchiolar–alveolar duct bifurcations for evidence of engraftment and differentiation of GFP-positive male cells, since we have established that asbestos exposure causes predictable development of fibrotic lesions at these anatomic sites (2–4). The results demonstrated that significant numbers of bone marrow progenitor cells migrated to developing asbestos-induced fibrogenic lesions at the bronchiolar–alveolar duct regions and that many of these cells differentiated into pulmonary cell types, including interstitial mesenchymal cells. Some of the results of these studies have been previously reported in the form of abstracts (15, 16).

METHODS

Female Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (200–220 g) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Transgenic male SD rats that ubiquitously express enhanced GFP under control of the cytomegalovirus enhancer and the chicken β-actin promoter were kindly provided by M. Okabe, Genome Information Research Center, Osaka University, Osaka, Japan (17). For bone marrow transplantation, female rats were irradiated at lethal levels by a split dose of 11 Gy (4 h between doses) from a 137Cs source (GammaCell 40; MDS Nordion, Ottowa, ON, Canada). After the second dose of radiation, 5 × 106 male GFP-positive mononuclear bone marrow cells in 1 ml phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were infused by tail vein. The male GFP-positive bone marrow cells were freshly isolated from femurs and tibias by capping the bones, placing the shafts into 1,000-μl pipette tips cut to fit into 1.5-ml centrifuge tubes, and centrifuging the samples at 950 × g for 1 minute to pellet the marrow. Mononuclear bone marrow cells from pooled cell pellets were resuspended into 25 ml of Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution (Gibco [Invitrogen], Carlsbad, CA), filtered through a 70-μm cell strainer (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), and purified by density centrifugation at 1,800 × g for 30 minutes without braking (Ficoll-Paque PLUS; Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ).

Asbestos Exposure

Three weeks after the bone marrow transplant, 100 μl of blood was obtained from the tail vein to examine chimerism by epifluorescence microscopy. Chimeric animals were exposed to chrysotile asbestos fibers for 5 hours on three consecutive days (10 mg/m3) as previously described (2–4). Groups of rats were killed at 1 day and at 2.5 weeks after the last asbestos exposure with a ketamine/xylazine overdose and trans-cardiac perfusion with cold PBS. After tying off the heart and the left lobe of the lung, the right lung was inflated by gravity with intratracheally instilled 10% formalin. The lung was then fixed overnight at 4°C in 10% formalin before paraffin embedding. Bone marrow of the chimeric animals was isolated (as above) for DNA extraction and real-time PCR.

Real-Time PCR

Genomic DNA was isolated from bone marrow by extraction with SDS/proteinase K and phenol/chloroform/isoamylalcohol (18). The DNA was then used as the template for assays of the rat Y chromosome by real-time PCR in an automated instrument (model 7700; ABI Perkin Elmer [Applied Biosystems], Foster City, CA) using Taqman PCR master mix (ABI Perkin Elmer). Y chromosome probe (5′-FAM CAACAGAATCCCAGCATGCAGAATTCA 3′-TAMRA) at 250 nM concentration was used with the primers (forward 5′ GGAGAGAGGCACAAGTTGGC 3′, reverse 5′ CCCCAGCTGCTTGCTGATC 3′; Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) at 900 nM concentrations. We used 300 ng of template genomic DNA per reaction. Standard curves of male DNA were generated by combining 250 to 0.005 ng of male DNA with 50 to 299.995 ng of female DNA (six standards in all).

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin sections of 8 μm were prepared from the embedded lungs of chimeric rats. The sections were incubated for 2 hours at 56°C, deparaffinized in xylene, and rehydrated by ethanol series ending with pure H2O (Chemicon [Millipore], Billerica, MA). After a 5-minute incubation in PBS, sections were incubated in 0.05 mg/ml proteinase K in 0.05 M Tris-HCl, 0.01 M EDTA, and 0.01 M NaCl, pH 7.8, for 10 minutes at 37°C. After two washes with PBS, the slides underwent antigen retrieval by microwaving them for 4 to 5 minutes in citrate buffer (2× SSC). They were then blocked for 1 hour at room temperature in 5% goat serum with 0.4% vol/vol triton-X 100 in PBS. Primary antibodies for single or double labeling were resuspended in the same blocking buffer and incubated overnight at 4°C. Primary antibodies used were: monoclonal anti-GFP (1:300; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), polyclonal anti-GFP (1:400; Molecular Probes [Invitrogen], Carlsbad, CA), monoclonal anti-monocyte/macrophages (1:100; Chemicon), polyclonal anti-collagen 1 (1:400; Cosmo Bio Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), polyclonal anti-pro–surfactant protein C (1:1000; Chemicon), monoclonal anti-α smooth muscle actin (1:800; Sigma, St. Louis, MO), polyclonal anti-vimentin (1:50; Spring Bioscience, Fremont, CA), and polyclonal anti-PCNA (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA). The next day, slides were washed three times in PBS, and secondary antibody was applied. For single labeling, Alexa 594 (red, 1:800; Molecular Probes) was used. For double labeling, each secondary antibody was incubated separately for 1 hour at room temperature. Slides were first incubated in secondary antibody against one host (mouse for example) conjugated to Alexa 488 (green, 1: 500–1: 800; Molecular Probes), washed three times in PBS and then the second secondary antibody against the other host (rabbit for example) was incubated (red, 1:800, Alexa 594). After three more washes to remove excess secondary antibody, slides were mounted in Vectashield with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Photographs were taken using ultraviolet microscopy (Nikon Eclipse E800; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) with a CCD camera (SPOT RT). Deconvolution microscopy was done using a Leica DMRXA Leica Microsystems, Bannockburn, IL microscope equipped with an automated x, y, z stage and CCD camera (Sensicam; Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Denver, CO). Images taken at 0.5-μm intervals were deconvoluted using commercial software (Slidebook software; Intelligent Imaging Innovations). As a positive control for PCNA staining, we examined sections of tail skin from a chimeric animal that was undergoing healing of a bite wound from a littermate. For negative staining controls we omitted the primary antibody or incubated in nonspecific IgG (10 μg/ml).

Quantification of Bone Marrow Cell Engraftment at the First Bronchiolar–Alveolar Duct

Images were captured with a ×20 power objective using a fluorescent microscope (Olympus BX-60) and a digital camera with Magnafire 2.1 software (Melville, NY). The first bronchiolar–alveolar ducts were detected using phase microscopy, and images of nuclear staining (DAPI, blue) were taken before images of GFP labeling (Alexa 594, red). Observers were blinded to slide identity. For each slide, images were taken of five randomly selected first bronchiolar–alveolar duct regions and also from five randomly selected regions of outlying lung parenchyma. Image measurements of blue or red staining were done using Image Pro Plus 4.5 (Media Cybernetics, Silver Springs, MD). Results were reported as the percent of GFP cells (red) versus cell nuclei (blue) per area. For lung parenchyma, five regions were quantified for each image captured. For bronchiolar–alveolar duct regions, only the bifurcation was quantified as previously described. Statistical significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni correction.

Fluorescent In Situ Hybridization

Paraffin sections were incubated for 2 hours at 56°C, deparaffinized in xylenes, and rehydrated by ethanol series ending with pure H2O (Millipore). Sections were then incubated in 0.3% H2O2 in PBS for 10 minutes to quench endogenous peroxidase activity, rinsed with PBS, and incubated in 0.2 M HCl for 20 minutes at room temperature. After a brief wash in pure H2O, slides were rinsed in 2× SSC/0.05% Tween 20 for 5 minutes, placed into 2× SSC, and heated to 100°C in a microwave for 5 minutes. After another wash in pure H2O and rinse in 2× SSC/0.05% Tween 20 for 5 minutes, sections were incubated in 0.05 mg/ml proteinase K in 0.05 M Tris-HCl, 0.01 M EDTA, and 0.01 M NaCl, pH 7.8, for 10 minutes at 37°C. After a 5-minute rinse in 2× SSC/0.05% Tween 20, sections were post-fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS for 10 minutes, rinsed in 2× SSC/0.05% Tween 20 for 5 minutes, dehydrated through an ethanol series, and air-dried. DNA probe for the rat Y chromosome was synthesized by nick-translation (DIG nick translation mix; Roche Diagnostics Corporation, Indianapolis, IN) and dissolved in a hybridization cocktail of 50% formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, 5× Denhardt's, 2× SSPE, and 100 μg/ml salmon sperm DNA, applied to sections, coverslipped, and sealed with rubber cement. Probe and target DNA was denatured simultaneously by 10 minutes of incubation at 90°C on a digital hot plate (Mirak; Barnstead/Thermolyne, Dubuque, IA). After rapid cooling on a glass plate on ice, slides were incubated overnight in a humidified chamber at 48°C. The next day, slides underwent several high stringency washes, blocking, and incubation in anti–DIG-POD (1:400; Roche) for 30 minutes at room temperature. After four 5-minute washes in 0.1 M Tris, 0.15 M NaCl, 0.05% vol/vol Tween 20, pH 7.4, hybridization signal was amplified by catalyzed reporter deposition for 10 minutes (TSA Fluorescence Systems; NEN, Perkin Elmer Life and Analytical Services, Inc., Waltham, MA). After another four 5-minute washes, slides were air-dried, mounted with Vectashield (DAPI), and visualized by epifluorescent microscopy with a CCD camera. For double fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) of the Y chromosome and chromosome 4, chromosome 4 probe was labeled with biotin (by nick-translation as above) and included in the same hybridization cocktail, but the hybridization temperature was 42°C. After reporter deposition for the Y probe, the slides were washed 4 × 5 minutes and were incubated in 3.0% vol/vol H2O2 in PBS for 30 minutes to quench the first deposition reaction. After another three 5-minute washes, the sections were incubated in Strepavidin-HRP (1:100 from NEN kit) for 30 minutes at room temperature, washed 3 × 5 minutes, and incubated in FITC-tyramide for 10 minutes at room temperature. Double FISH slides were analyzed by deconvolution microscopy and photographed as above. The DNA probes for the rat Y chromosome and chromosome 4 hybridize to repetitive genomic DNA sequences and function as chromosome painting probes. Both probes were gifts from Dr. Barbara Hoebee, National Institute of Public Health and Environment, The Netherlands.

For combined immunohistochemistry for pro–SP-C and Y chromosome FISH, tissue sections were processed as for FISH but were first incubated in primary and secondary antibodies before the ethanol dehydration step and hybridization of the DNA probe. The secondary antibody was goat–anti-rabbit conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (1:50; Chemicon). Staining was revealed by incubation with substrate according to the manufacturer's protocol (Vector Red; Vector Laboratories).

TUNEL Assays

TUNEL (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine-5′-triphosphate end labeling) was performed using the ApopTag Plus Fluorescein In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit according to the manufacturer's protocol (Chemicon).

Isolation of Pulmonary Cells and Cell Culture

Cells were isolated from the lungs as previously described (19). In brief, rats were killed by a ketamine/xylazine overdose and the lungs were cleared of blood by trans-cardiac perfusion with 300 to 400 ml of PBS. Fifteen milliliters of dispase (50 units/ml; Collaborative Research, Inc. Bedford, MA) was instilled into the lungs through the trachea with a 20-ml syringe attached to a 20-gauge luer stub adapter (Becton-Dickinson, Sparks, MD). The syringe was then removed and 3 ml of 1% low melting agarose (Sigma) in water was gently instilled into the lungs through the luer stub adapter. The agarose was then allowed to polymerize by placing crushed ice over the lungs for 2 minutes. The lungs were removed and placed in a sterile tube containing 5 ml dispase (50 units/ml) and incubated at 37oC for 45 minutes. Lung tissue was separated from the main airways and teased apart in 7 ml Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Sigma) with 0.01% type II DNase I (Sigma). The cell isolate was filtered through a 100-μm filter to remove tissue debris. The resulting cell suspension was centrifuged at 100 × g for 12 minutes at 4°C to collect the cell pellet, which was resuspended in 10 ml of DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), plated on a Petri dish, and incubated in a humidified, 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C for 30 minutes to remove as many as possible of the macrophages, which attach to plastic. The supernatant was then removed to a tissue culture dish and incubated for 3 days. The unattached cells and debris were removed and the attached cells were rinsed twice in PBS and incubated with DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS for 2 weeks.

Statistical Analysis

Values were expressed as means ± SD. Comparisons between two groups were made with the use of Student's t tests (two tailed). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

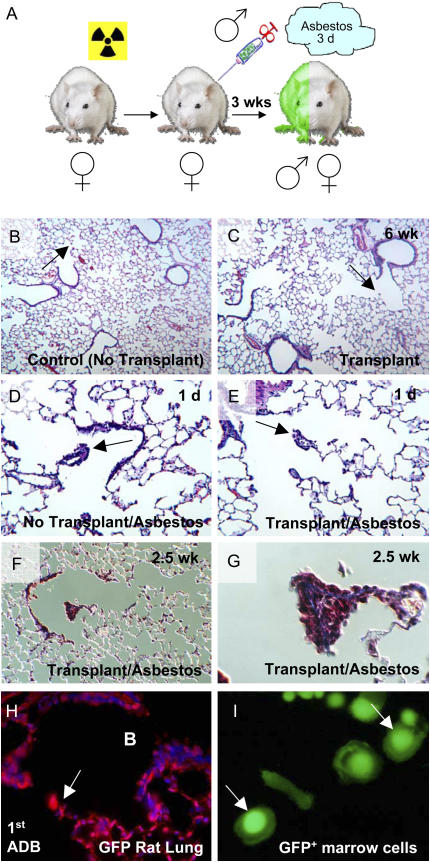

Histologic examination of lungs from control animals that were irradiated and then received a bone marrow transplant showed no apparent signs of pulmonary fibrosis (Figures 1B and 1C). We observed some inflammation in the bronchiolar walls of the transplanted animals, but importantly the first and second bronchiolar–alveolar ducts in these animals were normal (Figure 1C). Real-time PCR assays for the Y chromosome demonstrated that at time of killing (1 d or 2.5 wk after asbestos exposure), bone marrow chimerism was 75 ± 44% and 70 ± 34% for control 1 day and asbestos 1 day, respectively, and 99 ± 1.5% and 89 ± 14% for control 2.5 weeks and asbestos 2.5 weeks, respectively. There was no significant difference in the percent of bone marrow engraftment between control and asbestos-exposed animals at either time point (1 d, P = 0.9; 2.5 wk, P = 0.3). The typical asbestos-induced fibrogenic lesions of exposed transplanted animals were similar to those of asbestos-exposed control animals that did not receive bone marrow transplants, in that focal lesions were present at the first and second bronchiolar–alveolar duct bifurcations (Figures 1D and 1E). Blinded histopathologic examination could not discriminate among the different asbestos-exposed groups with and without bone marrow transplant, (i.e., the sizes and cell constituents of the lesions were apparently the same) (data not shown). The anatomic nature of these lesions has been documented extensively (2–4, 7–9). As expected, microscopic examination of the total number of cells in the first bronchiolar–alveolar duct bifurcations of control animals that were bone marrow transplanted but not exposed to asbestos and those that were bone marrow transplanted and asbestos-exposed revealed a significant increase in total cell number at the first bronchiolar–alveolar duct bifurcations after exposure to asbestos (control, 7.8 ± 1.6; 1 d, 46.8 ± 22.4, P ⩽ 0.0005; 2.5 wk, 55.5 ± 27.8, P ⩽ 0.0001). There was no significant difference between the number of cells localized to the first bronchiolar–alveolar duct bifurcations when 1 d lesions were compared with 2.5 wk lesions (P = 0.6). Gomori Trichrome staining of lung sections demonstrated that fibrosis occurred specifically in the bronchiolar–alveolar duct walls and in the interstitium in the proliferative lesions at the alveolar duct bifurcations (Figures 1F and 1G). We did not observe staining indicative of fibrosis in the surrounding lung parenchyma of control rats or those that were exposed to asbestos (Figure 1F).

Figure 1.

Pulmonary fibrosis model based on bone marrow transplantation and subsequent asbestos exposure. (A) Female Sprague-Dawley rats were irradiated at a lethal level (11 Gy) and immediately rescued by tail vein injection of 5 × 106 bone marrow mononuclear cells from male GFP-transgenic rats. After 3 wk of hematopoietic reconstitution, chimeric rats were exposed to asbestos for three consecutive days (5 h per day). Animals were killed 1 day or 2.5 weeks after the last asbestos exposure. (B) Control rat lung has normal morphology and exhibits normal bronchiolar–alveolar duct bifurcations (arrow). (C) Lung of chimeric rat 6 weeks after bone marrow transplant. There is slight bronchiolar inflammation but in general, lung architecture is normal and bronchiolar–alveolar duct morphology is unaffected (arrow). (D) Control (no bone marrow transplant) rat 1 day after asbestos exposure. (E) Chimeric (transplanted) rat 1 day after the last asbestos exposure. Arrows indicate asbestos lesions. Bone marrow transplantation does not alter the development of focal asbestos lesions at the first bronchiolar–alveolar ducts. (F) Gomori Trichrome stain of lung section from a chimeric asbestos-exposed rat (2.5 wk after exposure, ×10). Parenchymal lung tissue outside of areas exposed to asbestos does not display fibrosis (6 wk after bone marrow transplantation). (G) Asbestos lesion at the alveolar duct bifurcation from F. Note blue staining of the lesion that is indicative of interstitial cell fibrosis (×100). (H) Immunohistochemistry for GFP on lung section from transgenic GFP rat (control). Arrow indicates first alveolar duct bifurcation. B indicates bronchial space. The majority of pulmonary cells are positive for GFP. Note that many cells exhibit perinuclear and nuclear, as well as cytoplasmic staining. (I) Epifluorescent microscopy (FITC channel) of live adherent bone marrow cells from transgenic GFP rat. Bone marrow–derived cells also exhibit perinuclear and nuclear, as well as cytoplasmic staining.

Paraffin sections from transgenic GFP rats (controls) were stained with antibodies against GFP to examine the distribution of positive cells in the lung. The majority of bronchiolar epithelial cells, all cells of the alveolar duct bifurcations, and essentially all cells of the outlying parenchyma were stained by the GFP antibody (Figure 1H). We noted that in many cases GFP staining occurred in the cytoplasm and also strongly in a perinuclear and nuclear pattern (Figure 1H). This pattern of GFP expression was also observed by epifluorescence microscopy of freshly isolated (unstained) adherent bone marrow cells from the transgenic GFP rat (Figure 1I).

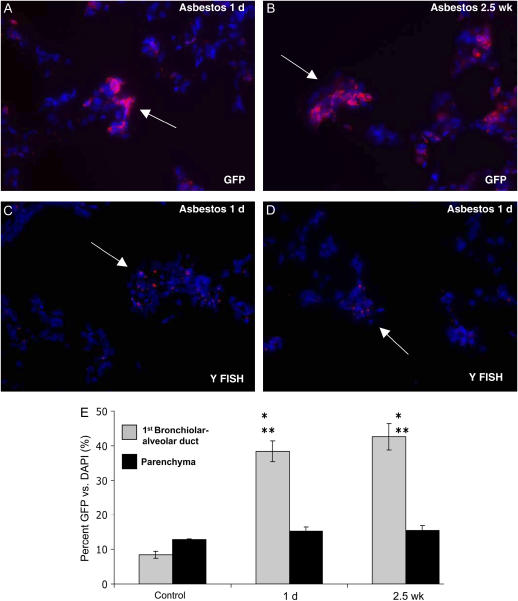

Bone marrow–derived cells were identified by immunohistochemistry for GFP in asbestos lesions at 1 day and 2.5 weeks after asbestos exposure (Figures 2A and 2B). Their presence was confirmed by fluorescent in situ hybridization for the Y chromosome (Figures 2C and 2D). Quantification of individual GFP-positive cells in randomly selected bronchiolar–alveolar duct regions of asbestos-treated animals versus those present in the control animals demonstrated highly significant engraftment in asbestos-exposed lungs at both time points (1 d, n = 3 [5 lesions per rat], P ⩽ 0.001; 2.5 wk, n = 4 [5 lesions per rat], P ⩽ 0.001; Figure 2E). Further, comparison of bone marrow cell engraftment into individual lesions versus engraftment in the surrounding lung parenchyma within the same animals also demonstrated highly significant engraftment, specifically in the developing asbestos-induced lesions (1 d, n = 3 [5 lesions per rat], P ⩽ 0.001; 2.5 wk, n = 4 [5 lesions per rat], P ⩽ 0.001; Figure 2E). For antibody staining controls, we omitted primary antisera or incubated in nonspecific IgG from the host (10 μg/ml, 1:100). By these controls, we did not observe staining that was similar to any of our primary antibody incubations. Leaving out the primary antibody gave no staining (data not shown), and the IgG controls gave low-level diffuse nonspecific staining (see IgG controls in Figures 3E and 5C).

Figure 2.

Bone marrow–derived cells engraft at asbestos lesions. (A) Immunohistochemistry for GFP (Alexa 594, red) demonstrating bone marrow–derived cell engraftment 1 day after asbestos exposure. (B) Bone marrow–derived cell engraftment persists 2.5 weeks after asbestos exposure. (C) Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) for the Y chromosome confirming male bone marrow–derived cell engraftment at first alveolar duct bifurcation 1 day after the last asbestos exposure (arrow). (D) Y chromosome FISH demonstrating bone marrow–derived cell engraftment at the second alveolar duct bifurcation 1 day after the last asbestos exposure. A typical small fibrogenic lesion is identified at a duct junction (arrow). (E) Quantification of bone marrow–derived cell engraftment in the first bronchiolar–alveolar duct in chimeric control animals (no asbestos) and chimeric animals 1 day and 2.5 weeks after asbestos exposure. *P ⩽ 0.001 for comparison of control and asbestos exposed first bronchiolar–alveolar ducts. **P ⩽ 0.001 for comparison of first bronchiolar–alveolar ducts to surrounding lung parenchyma within the same animals (1 day, n = 3 [5 lesions per rat]; 2.5 weeks, n = 4 [5 lesions per rat]).

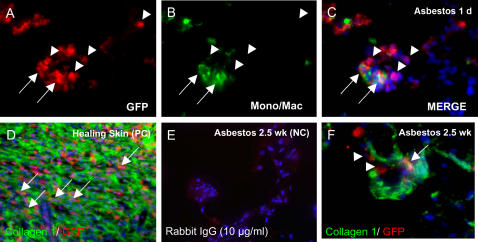

Figure 3.

Double immunohistochemistry for differentiation markers. (A–C) Staining for monocytes/macrophages (green) demonstrates that many of the bone marrow–derived cells (red) in the developing asbestos lesions 1 day after exposure are monocytes or macrophages (arrows). However, many bone marrow–derived cells are identified that are negative for blood cell markers (arrowheads). (D) Positive control (PC) showing bone marrow–derived collagen 1–positive fibrocytes in healing skin wound of chimeric rat. (E) Rabbit nonspecific IgG-negative control for lung 2.5 weeks after asbestos exposure (NC, 10 μg/ml). (F) Deconvolution microscopy of bone marrow–derived collagen 1–positive cell in asbestos lesion 2.5 wk after exposure (arrow). Collagen 1–negative/GFP-positive cells are also present (arrowheads).

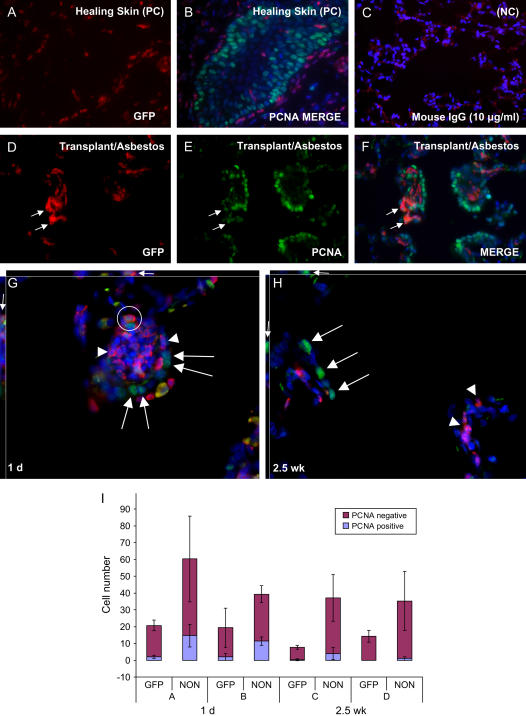

Figure 5.

Double immunohistochemistry for GFP and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) to identify dividing bone marrow–derived cells in the lung. (A, B) Positive control (PC) showing PCNA-positive keratinocytes (green nuclei) in healing skin wound of chimeric rat. (C) Mouse nonspecific IgG negative control (NC, 10 μg/ml). (D–F) Lung of chimeric rat 1 day after the last asbestos exposure. Rare GFP bone marrow–derived cells are positive for PCNA (arrows). The majority of the PCNA-positive cells are resident epithelial cells. (G) Deconvolution microscopy of asbestos-exposed lung 1 day after exposures. Large arrows: PCNA- positive host cells in asbestos lesion. Arrowheads: PCNA-negative bone marrow–derived cells. Circle: PCNA-positive bone marrow–derived cell. Small arrows: PCNA-positive bone marrow–derived cell from the xz and yz planes, showing nuclear localization of PCNA. (H) Deconvolution microscopy of asbestos-exposed lung 2.5 weeks after exposures. Proliferation has resolved in 2.5 week lesion. Large arrows: PCNA-positive host cells in bronchial lining. Arrowheads: PCNA-negative bone marrow–derived cells that remain engrafted in lesion after 2.5 weeks. Small arrows: PCNA-positive bronchial host cell from the xz and yz planes, showing nuclear localization of PCNA. (I) Relative proportions of PCNA-postive GFP and host (Non-GFP) cells in asbestos lesions 1 day and 2.5 weeks after exposures. Cell counts from two different animals are shown for both time points (animals A and B, 1 d; animals C and D, 2.5 wk)

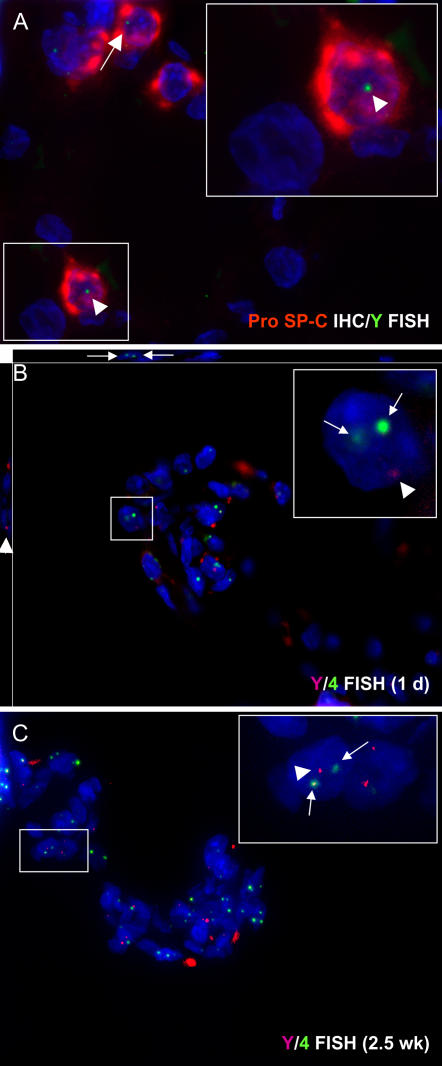

Immunohistochemical staining for GFP and monocyte/macrophage-specific proteins indicated that at the early time point (1 d after asbestos exposures) many of the bone marrow–derived cells in the asbestos lesions were monocytes or macrophages (Figures 3A–3C). By deconvolution microscopy, some of the GFP-positive cells that were present in lesions 2.5 weeks after asbestos exposure stained for collagen 1, indicating that they were participating in fibrosis (Figure 3F). Combining immunohistochemistry for pro–surfactant protein C (pro–SP-C) with FISH for the Y chromosome, we were able to identify rare bone marrow–derived cells with the phenotype of type II pneumocytes (< 0.5% of pro–SP-C+ cells in 2 animals examined, Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Deconvolution microscopy of bone marrow–derived cells in asbestos lesions. (A) Immunostaining for pro–surfactant protein C (pro–SP-C, red) combined with FISH for the Y chromosome (green) identifies bone marrow–derived type II pneumocytes in the asbestos-exposed lung. We did not observe bone marrow–derived type II cells in asbestos lesions. (B, C) Double fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) for the rat Y chromosome (red dots) and chromosome 4 (green dots) in 1 day and 2.5 week asbestos lesions. By FISH analysis of multiple asbestos lesions at the first bronchiolar–alveolar duct junctions, we did not find evidence of cell fusion. If present, cell fusion would be demonstrated by extra chromosome 4 signals (more than two) within a single cell nucleus. Insets show male bone marrow–derived cells (Y chromosome positive) that also stain for two chromosome 4s (indicative of a normal cell). These data do not exclude cell fusion from occurring at low levels, since the process of sectioning may occasionally remove chromosomes from the nucleus.

To examine the possibility of cell fusion as a mechanism for engraftment of bone marrow–derived cells, we assayed sections by double FISH for the rat Y chromosome and chromosome 4 (Figures 4B and 4C). Although we examined many lesions at the first bronchiolar–alveolar duct bifurcations from lung sections of asbestos-exposed animals, we did not find any cells having signals for more than two chromosome 4s. Although we cannot entirely exclude low levels of cell fusion by this technique, our data indicate that cell fusion is not the major mechanism of bone marrow–derived cellular engraftment into asbestos lesions.

To examine whether the engrafted cells in the lung were multiplying, we next stained tissue sections for GFP and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA). Although we observed some PCNA-positive bone marrow–derived cells in asbestos lesions (Figures 5D–5F), the majority of GFP-positive bone marrow–derived cells were PCNA-negative, suggesting that many of the bone marrow–derived cells that we observed were not proliferative at the time points examined. Deconvolution microscopy confirmed the nuclear localization of PCNA staining in some bone marrow–derived cells that had engrafted asbestos lesions (Figure 5G). Endogenous epithelial cells (GFP-negative) at asbestos lesions and along the bronchioles were consistently positive for PCNA, as expected for this model of lung injury (3, 8) (Figures 5C–5F and 5H). Significantly decreased numbers of PCNA-positive GFP and host cells were observed at the 2.5-week time point relative to the 1-day time point (GFP+/PCNA+, P ⩽ 0.05, host/PCNA+, P ⩽ 0.01; Figure 5I), indicating that some resolution of the fibrogenic process had occurred. For many alveolar duct bifurcations, by 2.5 weeks after exposure we observed some remaining PCNA-positive host cells along the bronchiole leading to a bifurcation, but very few to no PCNA-positive cells in the lesion itself (Figures 5H and 5I). Based on TUNEL assays (described below), the PCNA-positive cells in the walls of the airways may have been undergoing apoptosis or necrosis.

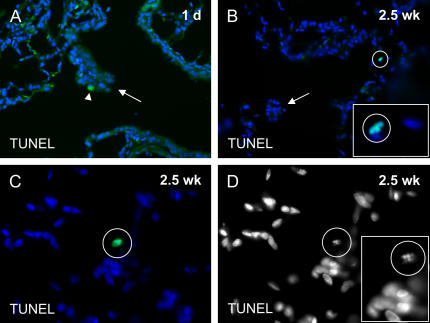

Cells undergoing DNA repair can also stain for PCNA. We performed TUNEL assays to determine whether some of the PCNA-positive cells at the alveolar duct bifurcation asbestos lesions were in fact apoptotic or necrotic rather than proliferating. We did not observe TUNEL-positive cells at the alveolar duct bifurcations of chimeric rats at either 1 day or 2.5 weeks after three consecutive days of 5-hour exposures to airborne asbestos fibers (Figures 6A and 6B). In addition, we did not observe TUNEL-positive cells in the walls of the bronchioles leading to the alveolar duct junction at 1 day after the asbestos exposures (Figure 6A). We did, however, observe rare TUNEL-positive cells associated with the bronchiolar walls 2.5 weeks after the last asbestos exposure (Figure 6B). We observed also that rare parenchymal cells were TUNEL-positive at the 2.5-week time point of our study (Figures 6C and 6D). DNA disorganization could be observed also by DAPI staining in all of the TUNEL-positive cells that we observed (Figure 6D). Because we did not observe TUNEL-positive cells in the alveolar duct bifurcation lesions at either time point in our study, the few PCNA-positive bone marrow–derived cells that we did observe in the alveolar duct bifurcation asbestos lesions were likely to be proliferative rather than apoptotic or necrotic.

Figure 6.

TUNEL to identify apoptotic or necrotic cells following asbestos exposure. (A) One day after three consecutive 5-hour daily exposures to airborne asbestos fibers, there were no TUNEL-positive cell nuclei in cells at the alveolar duct junction lesions (arrow) or in cells that line the walls of the bronchus. A macrophage is stained nonspecifically in the cytoplasm, but not in the nucleus (arrowhead). (B) Rare TUNEL-positive cell nuclei were observed in the bronchial walls 2.5 weeks after the asbestos exposures. However, there were not TUNEL-positive cells in the proliferative lesion at the alveolar duct junction (arrow). Inset magnification: ×100. (C) We also observed rare randomly distributed parenchymal cells that were TUNEL-positive 2.5 weeks after asbestos exposure, perhaps due to irradiation. (D) TUNEL-positive cell from C. DAPI signal without blue pseudocolor. Nuclear disorganization was clearly visible in TUNEL-postitive cells (inset).

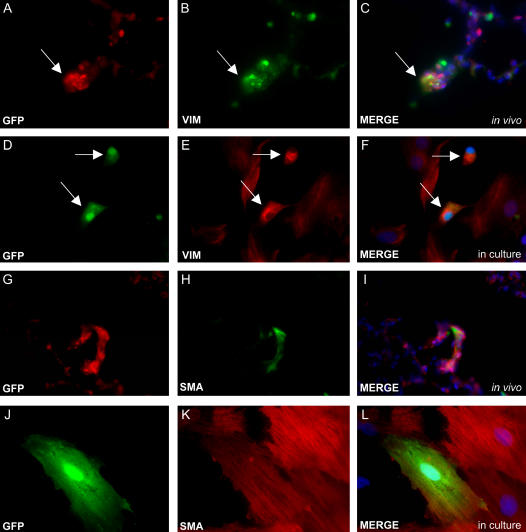

Finally, we examined whether asbestos exposure had influenced bone marrow progenitors to differentiate into mesenchymal cells. Through double immunostaining of lung sections, we identified both bone marrow–derived vimentin-positive fibroblasts (Figures 7A–7C), and bone marrow–derived α smooth muscle actin–positive cells (myofibroblasts or smooth muscle cells, Figures 7G–7I). In addition, cells from asbestos-exposed bone marrow transplanted rats were cultured from dispase-digested lung tissues, and many of these cells also expressed proteins of differentiated mesenchymal cells (Figures 7D–7F and 7J–7L), confirming the presence of these bone marrow–derived cells.

Figure 7.

Double immunostaining demonstrates mesenchymal cell engraftment from bone marrow progenitors after asbestos exposure. (A–C) Vimentin (VIM) staining shows fibroblast engraftment from cells that migrate from the bone marrow (arrow). (D–F) Vimentin staining of GFP-positive cells cultured from dispase-digested lung tissues after asbestos exposure confirms in vivo immunohistochemistry (arrows). (G–I) α smooth muscle actin (SMA) staining demonstrates myofibroblast or smooth muscle cell differentiation from bone marrow progenitors. (J–L) SMA immunocytochemistry of GFP-positive bone marrow–derived cells isolated and cultured from the lungs of asbestos-exposed chimeric rats also confirms in vivo stains.

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated that bone marrow–derived progenitor cells engraft into asbestos-induced fibrogenic lung lesions and differentiate into migrating macrophages and mesenchymal cell types. The GFP-positive cells were identified in the lungs of both control and asbestos-exposed animals. In addition, there were significantly increased numbers of bone marrow–derived cells in the developing asbestos-induced lesions relative to unexposed alveolar duct bifurcations and the surrounding lung parenchyma.

Asbestos injury is characterized by the proliferation of epithelial cells and interstitial mesenchymal cells that synthesize extracellular matrix components during pulmonary fibrogenesis (3, 4, 8, 20). At the time points we examined, PCNA staining showed that most of the proliferative cells in the lesions came from endogenous lung cells and not from cells of bone marrow origin. While a few bone marrow–derived cells stained for PCNA, the majority appeared to seed directly to the lung from the blood stream. Our TUNEL results demonstrate that while rare TUNEL-positive cells can be found in the bronchiolar walls leading to the alveolar duct bifurcations 2.5 weeks after asbestos exposure, we did not observe TUNEL-positive cells in the large proliferative lesions at the alveolar duct bifurcations themselves at 1 day or at 2.5 weeks after asbestos exposure. Therefore, the PCNA-positive bone marrow–derived cells that we observed in the alveolar duct bifurcations at 1 day after the last asbestos exposure were proliferative and not apoptotic, necrotic, or undergoing DNA repair.

Aljandali and coworkers (21) found that a single intratracheal administration of amosite asbestos (5 mg) in saline led to a threefold increase in the number of TUNEL-positive cells in bronchiolar–alveolar duct regions 1 week after asbestos exposure. The model that they used differs in several ways from our model presented here. The animals described here were exposed to aerosolized chrysotile asbestos fibers, while theirs received intratracheal amosite in saline. Amosite asbestos has been noted to contain higher concentrations of iron than chrysotile asbestos, and this is expected to produce higher levels of ROS in exposed cells and thus higher levels of apoptosis (21). We examined our animals at 1 day and 2.5 weeks after three successive days of asbestos inhalation (5 h each day), while their animals received a single exposure and they examined their rats at 1 and 4 weeks after the administration. Finally, our animals were lethally irradiated before bone marrow transplant, while theirs were not irradiated or transplanted. Therefore, our results confirm the apoptosis results that they reported in the bronchiolar walls, but may differ with respect to the alveolar duct bifurcations where we focused our analysis.

It is currently controversial whether epithelial cells in the lung can derive from circulating cells from the bone marrow (22, 23). In the model presented here, we found that bone marrow–derived cells could engraft the lung directly or through cell fusion as epithelial cells at low levels. We identified rare bone marrow–derived cells type II cells (pro–SP-C+) in the lung parenchyma, but not in asbestos lesions. Although we observed that bone marrow–derived cells made up less than 0.5% of the total pro–SP-C+ cells in two animals examined, our observation of bone marrow–derived type II cells in the rat is consistent with that of Krause and colleagues (24), who found that type II pneumocytes in the mouse lung could originate from the bone marrow after transplantation of a single bone marrow–derived stem cell. Loi and coworkers (25) recently found that transplantation of wild-type marrow into CFTR knockout mice resulted in 0.03% chimerism of airway epithelial cells, of which 0.01% expressed the previously deficient CFTR protein. Although the study did not determine whether bone marrow–derived cells engrafted and differentiated directly as lung epithelial cells or rather fused with endogenous cells, Loi and colleagues (25) clearly demonstrated that pulmonary epithelial cell engraftment from bone marrow–derived cells does occur at low levels. Our observations do not establish whether the GFP-positive epithelial cells that we observed were actually derived from bone marrow cells that first engrafted the lung as GFP-positive type II cells or fused with endogenous type II cells.

Harris and coworkers (26) showed in a mouse bone marrow transplant model that the pulmonary epithelial phenotypes generated from bone marrow–derived cells are not primarily the result of cell fusion. In concert with this finding, by deconvolution microscopic analysis of double FISH for the rat Y chromosome and chromosome 4 we did not observe fused bone marrow–derived cells in any of the asbestos lesions that we examined. However, it is possible that cell fusion may occur at a low level and that its identification was missed when extra chromosomes were not included in nuclei that were thin-sectioned.

Hashimoto and colleagues (27) reported a mouse bleomycin model of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) in which more than 80% of the collagen I–expressing cells in the fibrotic lung arose from the bone marrow. In addition, they noted that the fibroblast phenotypes isolated from the lung were telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT)-positive and Col I–positive, but α-smooth muscle actin–negative, even after exposure to transforming growth factor (TGF)-β. We report here the identification in the lung and the isolation and subsequent culture of GFP+/α smooth muscle actin+ cells directly from the lungs of asbestos-treated rats without exposure to exogenous cytokines. Some of these cells may be smooth muscle cells (28), and further work will be necessary to define the specific phenotype of these α smooth muscle actin–expressing fibroblastic cells. Myofibroblast progenitors may or may not migrate from the bone marrow, depending on the model of fibrosis or the organism that is studied (27–29). Phillips and coworkers (30) examined human fibrocyte trafficking in SCID mice using the bleomycin model of IPF. Similar to the results from our asbestos model using chimeric rats, after several weeks they were able to re-isolate human α smooth muscle actin–expressing cells from the lungs of the mice. Also, it is clear from previous work that asbestos-induced lesions in wild-type rats exhibit increased numbers of α smooth muscle actin– and vimentin-positive mesenchymal cells (28). By deconvolution microscopy we found that some of the GFP-positive cells in lesions 2.5 weeks after asbestos exposure expressed collagen 1, indicating contribution to pulmonary fibrosis. Whether or not the newly engrafted bone marrow–derived cells that have differentiated to a mesenchymal phenotype in the bone marrow transplant/asbestos model will persist in the lesions for greater than 2.5 weeks has yet to be determined.

It was interesting to find bone marrow–derived macrophages in and around the developing fibrogenic lesions. In several previous studies we have characterized and quantified the macrophage response to inhaled asbestos in rats and mice (7, 31, 32). It appeared in our earlier studies that the macrophages, both alveolar and interstitial, were derived from local cell populations, and that the cells were attracted to the lesions when the inhaled fibers activated the fifth component of complement found on alveolar surfaces (32). Whether or not the macrophages that we and others have identified as initial responders after lung injury are in fact from local or bone marrow populations or are a mixture thereof now remains an open question. These macrophages, along with the epithelial and mesenchymal cell populations, express a variety of cytokines and growth factors, including platelet-derived growth factor, TGF-α, TGF-β and TNF-α (1, 5, 33). The role that each of the factors might play in the development of fibrogenesis has been considered extensively (1), but at this time, no one can say which of these potent factors is being synthesized and released by the bone marrow–derived stem cells in the developing lesions.

The work presented here and the recent work of others has demonstrated that bone marrow–derived cells engraft the lung in multiple models of pulmonary fibrosis (27, 29, 34, 35). Further study should elucidate whether or not the macrophages or other bone marrow–derived cells we have identified in the developing lesions are producing the potent bioactive peptides that many investigators have postulated will ameliorate or exacerbate the fibrogenic process.

Supported by National Institutes of Health (HL073252 [D.J.P.], HL075161 [D.J.P.], HL 60532 [A.R.B.], ES06766 [A.R.B.]); HCA the Health Care Co.; and the Louisiana Gene Therapy Research Consortium (D.J.P., J.L.S.), and the Louisiana HEF (A.R.B.).

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.200607-1004OC on May 11, 2007

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Morris G, Brody A. Molecular mechanisms of particle induced lung disease. In: Rom WN, editor. Environmental and occupational medicine, 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998. pp. 305–333

- 2.Chang LY, Overby LH, Brody AR, Crapo JD. Progressive lung cell reactions and extracellular matrix production after a brief exposure to asbestos. Am J Pathol 1988;131:156–170. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGavran PD, Moore LM, Brody AR. Inhalation of chrysotile asbestos induces rapid cellular proliferation in small pulmonary vessels of mice and rats. Am J Pathol 1990;136:695–705. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brody AR. Asbestos exposure as a model of inflammation inducing interstitial pulmonary fibrosis. In: Gallin JI, Goldstein IM, Snyderman R, editors. Inflammation: basic principles and clinical correlates, 2nd ed. New York: Raven Press; 1992. pp. 1033–1049

- 5.Lasky JA, Brody AR. Interstitial fibrosis and growth factors. Environ Health Perspect 2000;108:751–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quinlan TR, Marsh JP, Janssen YM, Borm PA, Mossman BT. Oxygen radicals and asbestos-mediated disease. Environ Health Perspect 1994;102:107–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brody AR, Hill LH, Adkins B Jr, O'Connor RW. Chrysotile asbestos inhalation in rats: deposition pattern and reaction of alveolar epithelium and pulmonary macrophages. Am Rev Respir Dis 1981;123:670–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGavran PD, Butterick CJ, Brody AR. Tritiated thymidine incorporation and the development of an interstitial lesion in the bronchiolar-alveolar regions of the lungs of normal and complement-deficient mice after inhalation of chrysotile asbestos. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol 1989;9:377–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinkerton KE, Plopper CG, Merler RR, Brody AR, Crapo JD. Airway branching patterns dictate asbestos fiber location and the extent of tissue injury at the alveolar level. Lab Invest 1986;55:688–695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mossman BT, Marsh JP, Sesko A, Hill S, Shatos MA, Doherty J, Petruska J, Adler KB, Hemenway D, Mickey R, et al. Inhibition of lung injury, inflammation, and interstitial pulmonary fibrosis by polyethylene glycol-conjugated catalase in a rapid inhalation model of asbestosis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990;141:1266–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu J-Y, Brass DM, Hoyle GW, Brody AR. TNF-α receptor knockout mice are protected from the fibroproliferative effects of inhaled asbestos fibers. Am J Pathol 1998;153:1839–1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lasky JA, Ortiz LA. Antifibrotic therapy for the treatment of pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Med Sci 2001;322:213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prockop DJ, Gregory CA, Spees JL. One strategy for cell and gene therapy: harnessing the power of adult stem cells to repair tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003;11917–11923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Herzog EL, Chai L, Krause DS. Plasticity of marrow derived cells. Blood 2003;102:3483–3493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spees JL, Lasky JA, Pociask DA, Sullivan DE, Prockop DJ, Brody AR. Adult rat bone marrow cells migrate to normal and fibrogenic lungs and differentiate in various anatomic compartments [abstract]. 2004;:A212.

- 16.Brody AR, Pociask DA, Sullivan DE, Whitney MJ, Lasky JA, Prockop DJ, Spees JL. Bone marrow-derived cells migrate to the lung and differentiate in asbestos-induced fibroproliferative lesions [abstract]. 2005;:A282.

- 17.Ito T, Suzuki A, Imai E, Okabe M, Hori M. Bone marrow is a reservoir of repopulating mesangial cells during glomerular remodeling. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001;12:2625–2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 1998.

- 19.Warshamana GS, Corti M, Brody AR. TNF-alpha, PDGF, and TGF-beta(1) expression by primary mouse bronchiolar-alveolar epithelial and mesenchymal cells: TNF-alpha induces TGF-beta (1). Exp Mol Pathol 2001;71:13–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brody AR, Overby LH. Incorporation of tritiated thymidine by epithelial and interstitial cells in bronchiolar-alveolar regions of asbestos-exposed rats. Am J Pathol 1989;134:133–144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aljandali A, Pollack H, Yeldandi A, Li Y, Weitzman SA, Kamp DW. Asbestos causes apoptosis in alveolar epithelial cells: role of iron-induced free radicals. J Lab Clin Med 2001;137:330–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kotton DN, Fabian AJ, Mulligan RC. Failure of bone marrow to reconstitute lung epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2005;33:328–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang JC, Summer R, Sun X, Fitzsimmons K, Fine A. Evidence that bone marrow cells do not contribute to the alveolar epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2005;33:335–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krause DS, Theise ND, Collector MI, Henegariu O, Hwang S, Gardner R, Neutzel S, Sharkis SJ. Multi-organ, multi-lineage engraftment by a single bone marrow-derived stem cell. Cell 2001;105:369–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loi R, Beckett T, Goncz KK, Suratt BT, Weiss DJ. Limited restoration of cystic fibrosis lung epithelium in vivo with adult bone marrow–derived cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006;173:171–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harris RG, Herzog EL, Bruscia EM, Grove JE, Van Arnam JS, Krause DS. Lack of fusion requirement for development of bone marrow-derived epithelia. Science 2004;305:90–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hashimoto N, Jin H, Chensue SW, Phan SH. Bone marrow-derived progenitor cells in pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest 2003;113:243–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perdue TD, Brody AR. Distribution of transforming growth factor- beta 1, fibronectin, and smooth muscle actin in asbestos-induced pulmonary fibrosis in rats. J Histochem Cytochem 1994;42:1061–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Epperly MW, Guo H, Gretton JE, Greenberger JS. Bone marrow origin of myofibroblasts in irradiation pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2003;29:213–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phillips RJ, Burdick MD, Hong K, Lutz MA, Murray LA, Xue YY, Belperio JA, Keane MP, Strieter RM. Circulating fibrocytes traffic to the lungs in response to CXCL12 and mediate fibrosis. J Clin Invest 2004;114:438–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGavran PD, Butterick CJ, Brody AR. Tritiated thymidine incorporation and the development of an interstitial lesion in the bronchiolar-alveolar regions of the lungs of normal and complement deficient mice after inhalation of chrysotile asbestos. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol 1989;9:377–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Warheit DB, Hill LH, George G, Brody AR. Time course of chemotactic factor generation and the macrophage response to asbestos inhalation. Am Rev Respir Dis 1986;134:128–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brody AR, Brass DM, Liu J-Y, Morris GF, Hoyle GW. Asbestos-induced peptide growth factors that mediate interstitial pulmonary fibrosis. In: Chiyotani K, Hosoda Y, Aizawa Y, editors. Advances in the prevention of occupational respiratory diseases. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science; 1998. pp. 878–883.

- 34.Direkze NC, Forbes SJ, Brittan M, Hunt T, Jeffery R, Preston SL, Poulsom R, Hodivala-Dilke K, Alison MR, Wright NA. Multiple organ engraftment by bone marrow-derived myofibroblasts and fibroblasts in bone-marrow-transplanted mice. Stem Cells 2003;21:514–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ortiz LA, Gambelli F, McBride C, Gaupp D, Baddoo M, Kaminski N, Phinney DG. Mesenchymal stem cell engraftment in lung is enhanced in response to bleomycin exposure and ameliorates its fibrotic effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003;100:8407–8411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]