Abstract

Background

Self‐management and adequate consultation behaviour are essential for the successful treatment of chronic heart failure (CHF). Patients with a type‐D personality, characterised by high social inhibition and negative affectivity, may delay medical consultation despite increased symptom levels and may be at an increased risk for adverse clinical outcomes.

Aim

To examine whether type‐D personality predicts poor self‐management and failure to consult for evident cardiac symptoms in patients with CHF.

Design/methods/patients

178 outpatients with CHF (aged ⩽80 years) completed the type‐D Personality Scale at baseline, and the Health Complaints Scale (symptoms) and European Heart Failure Self‐care Behaviour Scale (self‐management) at 2 months of follow‐up. Medical information was obtained from the patients' medical records.

Results

At follow‐up, patients with a type‐D personality experienced more cardiac symptoms (OR 6.4; 95% CI 2.5 to 16.3, p<0.001) and more often appraised these symptoms as worrisome (OR 2.9; 95% CI 1.3 to 6.6, p<0.01) compared with patients with a non‐type‐D personality. Paradoxically, patients with a type‐D personality were less likely to report these symptoms to their cardiologist/nurse, as indicated by an increased risk for inadequate consultation behaviour (OR 2.7; 95% CI 1.2 to 6.0, p<0.05), adjusting for demographics, CHF severity/aetiology, time since diagnosis and medication. Accordingly, of 61 patients with CHF who failed to consult for evident cardiac symptoms, 43% had a type‐D personality (n = 26). Of the remaining 108 patients with CHF, only 14% (n = 16) had a type‐D personality.

Conclusion

Patients with CHF with a type‐D personality display inadequate self‐management. Failure to consult for increased symptom levels may partially explain the adverse effect of type‐D personality on cardiac prognosis.

Because of the ageing population and increasing rate of chronic medical diseases, finding the best management for these conditions is an important goal in healthcare.1 Chronic heart failure (CHF) is a serious chronic condition that has been associated with high mortality and hospitalisation rates, limited functional capacity, impaired health status and escalating health costs, despite recent developments in treatment options.2,3,4,5

Poor self‐management, or self‐care, is associated with an increased risk of adverse clinical outcome in CHF.6 Self‐management is the individual's ability to manage the symptoms, treatment and lifestyle changes inherent in living with a chronic condition such as CHF7; it is the process whereby individuals act on their own behalf to promote health.8 One important aspect of self‐management is consultation behaviour—that is, consulting a doctor when experiencing cardiac symptoms.9

Some patients with CHF may delay consulting medical services for relevant symptoms. This patient delay, which refers to the period between the onset of symptoms and the moment of consultation,10 may contribute to adverse clinical outcomes in CHF.

The decision to seek help is influenced by the individual's appraisal of the seriousness of the symptoms.11,12 However, symptom appraisal is a necessary but not sufficient condition for seeking help. Consultation behaviour is also influenced by attitudes to help‐seeking behaviour,13 such as concerns about the consequences of disclosing personal feelings and thoughts. For example, patients with myocardial infarction who did not talk with someone about their symptoms had longer delays in seeking help.14 Hence, patients with CHF who are inhibited in disclosing symptoms to their cardiologist or specialised heart failure nurse may also be more likely to delay medical consultation.

Patients with a type‐D personality tend to inhibit self‐expression in social interactions, as indicated by a high score on social inhibition.15,16 Given their high level of inhibition, patients with a type‐D personality may be at risk for inadequate self‐management in terms of poor consultation behaviour. This failure to consult for cardiac symptoms is paradoxical, because, given their tendency to experience negative feelings and to worry,15,16 patients with a type‐D personality may experience concerns about their health status. Hence, the objective of this predictive study was to examine the role of type‐D personality in poor self‐management and failure to consult for clinically evident symptoms in patients with CHF.

Methods

Study population and procedure

The sample included 178 consecutive outpatients with CHF from the TweeSteden teaching hospital in Tilburg, The Netherlands. Inclusion criteria were: (1) systolic heart failure; (2) left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ⩽40%; and (3) pharmacologically stable 1 month preceding inclusion. Patients (1) aged >80 years; (2) with a history of diastolic heart failure; (3) incapable of understanding and reading Dutch; (4) with cognitive impairments and life‐threatening comorbidities; or (5) diagnosed as having psychiatric disease (except depression and anxiety) were excluded. Patients were treated for CHF by a cardiologist and a specialised heart failure nurse according to the most recent guidelines.3 The hospital's medical ethics committee approved the study protocol, and the study was carried out according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent.

The cardiologist or specialised heart failure nurse selected patients with CHF for inclusion in the study on the basis of the above‐mentioned criteria. Patients were informed about the study and asked to participate by their treating cardiologist. If patients agreed to participate, they were called the same week to make an appointment for completing a set of psychological questionnaires. Participation was voluntary. During the first visit, patients completed the type‐D Personality Scale (DS14).16 During a second visit, 2 months later, the patients filled out the Health Complaints Scale (HCS; symptoms)17 and the European Heart Failure Self‐care Behaviour Scale (EHFScBS; self‐management)18. Patients who did not return the questionnaires within 2 weeks received a reminder telephone call. The response rate in the present study was 94%.

Self‐management and consultation behaviour

The EHFScBS is a disease‐specific measure of the self‐management behaviour of patients with CHF.18 The questionnaire consists of 12 items that are answered on a 5‐point Likert scale ranging from “I completely agree” (1) to “I don't agree at all” (5). A high total score indicates less self‐care behaviour. Cronbach's α for the total scale is 0.81.18

Principal component analysis (PCA) with varimax rotation was used to the determine the structure of the EHFScBS at the 2‐month follow‐up. Factors with an eigenvalue >1 were retained according to the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) criterion. KMO and Bartlett's test of sphericity were used as fit indices. PCA at the 2‐month follow‐up revealed a four‐factor solution (table 1). KMO (0.75) and Bartlett's test of sphericity (χ2 (66, n = 178) = 483.5, p<0.001) indicated that PCA was adequate for this data. Only one specific facet of self‐management was found—that is, consultation behaviour (eg, “If my feet/legs become more swollen than usual, I contact my doctor or nurse”). Cronbach's α for this factor was 0.86, and 0.46, 0.37 and 0.28 for the other three factors, respectively. Therefore, we constructed a four‐item “consultation behaviour” subscale as a specific component of self‐management that should be studied in its own right, in addition to the EHFScBS total scale (table 1, factor 1; items 3, 4, 5, 8). The mean (SD) score of the consultation behaviour subscale was 9.8 (4.9), and the scores were normally distributed. A relative lack of consultation behaviour was defined as a score above the median split of this four‐item subscale.

Table 1 Facets of self‐management at the 2‐month follow‐up.

| Items of the EHFScBS | Rotated factor solution | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | |

| 4. If my feet/legs become more swollen than usual, I contact my doctor or nurse | 0.87 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.04 |

| 3. If my shortness of breath increases, I contact my doctor or nurse | 0.85 | 0.07 | −0.03 | −0.01 |

| 8. If I experience increased fatigue, I contact my doctor or nurse | 0.84 | 0.26 | 0.07 | 0.01 |

| 5. If I gain 2 kg in 1 week, I contact my doctor or nurse | 0.73 | 0.15 | 0.19 | −0.03 |

| 12. I exercise regularly | 0.07 | 0.70 | −0.28 | −0.01 |

| 9. I eat a low salt diet | 0.15 | 0.63 | 0.21 | 0.10 |

| 6. I limit the amount of fluids I drink (not >1.5–2 l/day) | 0.30 | 0.52 | 0.22 | 0.07 |

| 2. If I get short of breath, I take it easy | 0.19 | −0.11 | 0.77 | −0.13 |

| 7. I take rest during the day | 0.01 | 0.28 | 0.64 | 0.18 |

| 10. I take my medication as prescribed | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.30 | 0.66 |

| 11. I get a flu shot every year | −0.05 | 0.27 | −0.09 | 0.65 |

| 1. I weigh myself every day* | 0.05 | 0.42 | 0.23 | −0.56 |

EHFScBS, European Heart Failure Self‐care Behaviour Scale.

Factor loadings are presented in bold.

*Item 1 could not be assigned to any of the factors because of ambiguous factor loadings.

Type‐D personality

The DS14 was used to assess type‐D personality.16 The DS14 consists of two seven‐item subscales—that is, negative affectivity and social inhibition.16 The 14 items are answered on a 5‐point Likert scale ranging from “false” (0) to “true” (4). A standardised cut‐off ⩾10 on both subscales indicates those with a type‐D personality. Both subscales are internally consistent, with a Cronbach's α of 0.88 for the negative affectivity subscale and of 0.86 for the social inhibition subscale, and have a good test–retest with r = 0.72 and 0.82, respectively.16 In the present study, 24% (42/178) of the patients were classified as having a type‐D personality.

Cardiac symptoms

The HCS contains a 12‐item self‐report subscale of cardiac symptoms that are frequently experienced by patients with established heart disease.17 These include cardiopulmonary symptoms (five items; eg, “shortness of breath”), fatigue (four items; eg, “feelings of exhaustion”) and sleep problems (three items; eg, “disturbed sleep”). The HCS also contains a six‐item subscale representing worries about health (eg, “worrying about health”, “the idea that you have a serious illness”). Patients indicate how much they suffer from a particular symptom on a four‐point Likert scale ranging from “not at all” (0) to “extremely” (4).17 All scales have a high internal consistency, with Cronbach's α ⩾0.89 and test–retest reliability r⩾0.69.17

Clinical variables

Clinical variables included LVEF, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class and aetiology of CHF, medication and time since diagnosis of CHF. Information on clinical variables was obtained from the patients' medical records and from the treating cardiologist. Sociodemographic information included sex, age, marital status and educational level.

Statistical analysis

Before statistical analyses, NYHA class, aetiology of heart failure, educational level and marital status were dichotomised according to NYHA class III/IV versus NYHA class I/II, ischaemic versus non‐ischaemic aetiology, low versus high educational level, and partner versus no partner, respectively. The EHFScBS, the Consultation Behaviour subscale, and the HCS were recoded into dichotomous variables using a median split reflecting, respectively, good versus poor self‐management, good versus poor consultation behaviour, and cardiac versus no cardiac complaints. For comparison between two groups, we used the χ2 test for discrete variables and the Student t‐test for independent samples for continuous variables.

Logistic regression analysis was used to determine whether type‐D was an independent predictor of cardiac symptoms, worries about health, self‐management and consultation behaviour adjusting for gender, age, marital status, educational level, LVEF, NYHA class, aetiology of CHF, medication and time since diagnosis.

Results

Demographic statistics

Table 2 presents the patients' characteristics stratified by type‐D personality. There were significant differences between patients with a type‐D personality and patients with a non‐type‐D personality only with respect to medication—that is, diuretics (χ2 (1, n = 178) = 5.8, p<0.05) and calcium antagonists (χ2 (1, n = 178) = 3.2, p<0.01) were more often prescribed to patients with a type‐D personality.

Table 2 Baseline characteristics of patients stratified by type‐D personality.

| Total sample | Type‐D personality (n = 42) | Non‐type‐D personality (n = 136) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) age, years | 66.6 (8.4) | 68.2 (7.8) | 66.1 (8.6) | 0.16 |

| Men, n (%) | 140 (79) | 33 (79) | 107 (79) | 0.98 |

| Lower educational level, n (%) | 154 (87) | 39 (93) | 115 (85) | 0.17 |

| Having no partner, n (%) | 43 (24) | 12 (29) | 31 (23) | 0.45 |

| Mean (SD) LVEF% | 29.9 (6.7) | 28.9 (6.6) | 30.2 (6.7) | 0.32 |

| NYHA class III and IV, n (%) | 96 (54) | 28 (67) | 68 (50) | 0.06 |

| Ischaemic aetiology, n (%) | 101 (56) | 24 (57) | 76 (56) | 0.86 |

| Mean (SD) time since diagnosis | 3.9 (4.1) | 3.4 (4.1) | 4.0 (4.1) | 0.34 |

| ACE‐inhibitor users, n (%) | 142 (80) | 33 (79) | 109 (80) | 0.82 |

| All‐antagonist users, n (%) | 30 (17) | 8 (19) | 22 (16) | 0.66 |

| Diuretic users, n (%) | 142 (80) | 39 (93) | 103 (76) | 0.02* |

| Digitalis users, n (%) | 56 (32) | 15 (36) | 41 (30) | 0.50 |

| β‐Blocker users, n (%) | 116 (65) | 31 (74) | 85 (63) | 0.18 |

| Long‐acting nitrate users, n (%) | 44 (25) | 14 (33) | 30 (22) | 0.14 |

| Short‐acting nitrate users, n (%) | 17 (10) | 7 (17) | 10 (7) | 0.07 |

| Calcium antagonist users, n (%) | 16 (9) | 8 (19) | 8 (6) | 0.01* |

| Anticoagulant users, n (%) | 77 (43) | 17 (41) | 60 (44) | 0.68 |

| Aspirin users, n (%) | 80 (45) | 19 (45) | 61 (45) | 0.97 |

| Statin users, n (%) | 84 (47) | 20 (48) | 64 (47) | 0.95 |

LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

*p<0.05.

Type‐D and cardiac symptoms

At follow‐up, type‐D personality was an independent predictor of cardiac symptoms at 2‐months of follow‐up (odds ratio (OR) 6.4; 95% CI 2.5 to 16.3, p<0.001), adjusting for sociodemographic variables, LVEF, NYHA class, ischaemic aetiology, time since diagnosis, use of diuretics and use of calcium antagonists. Apart from type‐D personality, younger age (OR 0.9; 95% CI 0.9 to 1.0, p<0.01), lower educational level (OR 3.0; 95% CI 1.1 to 8.5, p<0.05) and NYHA class III/IV (OR 2.2; 95% CI 1.1 to 4.5, p<0.05) also independently predicted cardiac symptoms at 2 months.

Patients with a type‐D personality had a mean (SD) score of 17.2 (9.7) on the cardiac symptoms scale of the HCS compared with 9.6 (8.7) for patients with a non‐type‐D personality (p<0.001). Patients with a type‐D personality also scored significantly higher on cardiopulmonary symptoms (p = 0.002), fatigue (p<0.001), sleep problems (p<0.001) and worries about health (p = 0.001) than patients with a non‐type‐D personality. Finally, type‐D personality was an independent predictor of worries about health adjusting for all other variables at follow‐up. Patients with a type‐D personality were at a threefold increased risk to worry about their cardiac symptoms (OR 2.9; 95% CI 1.3 to 6.6, p<0.01) compared with patients with a non‐type‐D personality.

Type‐D, self‐management and consultation behaviour

When the total score of the EHFScBS was used as an outcome measure, demographics, severity of CHF and type‐D personality were not significantly related to overall self‐management at the 2‐month follow‐up. Men (OR 2.0; 95% CI 0.9 to 4.5, p = 0.07) and lower educational level (OR 2.4; 95% CI 0.9 to 6.8, p = 0.07) had a near significant effect. However, type‐D was an independent predictor of displaying little consultation behaviour at follow‐up when adjusting for all other variables including LVEF and NYHA class (OR 2.7; 95% CI 1.2 to 6.0, p<0.05; table 3). In contrast with their high levels of cardiac symptoms and worries about health, patients with a type‐D personality were at a more than twofold increased risk of failing to consult for these symptoms compared with patients with a non‐type‐D personality (table 3). There was also a tendency for patients without a partner to be low in consultation behaviour.

Table 3 Predictors of displaying little consultation behaviour at the 2‐month follow‐up (multivariable analysis).

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Men | 1.34 (0.61 to 2.95) | 0.47 |

| Age | 0.99 (0.95 to 1.03) | 0.60 |

| Having no partner | 2.10 (0.96 to 4.59) | 0.06 |

| Lower educational level | 2.05 (0.81 to 5.20) | 0.13 |

| NYHA class III and IV | 0.74 (0.39 to 1.44) | 0.38 |

| LVEF | 1.00 (0.95 to 1.05) | 0.85 |

| Ischaemic aetiology | 0.91 (0.47 to 1.77) | 0.79 |

| Time since diagnosis | 1.08 (0.99 to 1.17) | 0.07 |

| Diuretics users | 0.80 (0.36 to 1.76) | 0.59 |

| Calcium antagonists users | 0.77 (0.24 to 2.44) | 0.66 |

| Type‐D personality | 2.67 (1.19 to 6.00) | 0.02* |

LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

*p<0.05.

Subgroups at risk for inadequate consulting

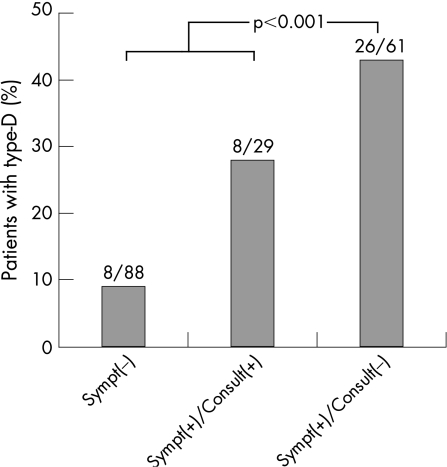

Patients with CHF who experienced clinically evident cardiac symptoms but were less likely to consult for these symptoms were considered to be at risk for inadequate consulting as a clear indicator of poor self‐management. In post hoc analysis, patients who reported cardiac symptoms but displayed poor consultation behaviour were compared with all other patients. Multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed that type‐D personality was an independent predictor of reporting cardiac symptoms while failing to consult (OR 5.1; 95% CI 2.3 to 11.6, p<0.001). Hence, of 61 patients with CHF who failed to consult for evident cardiac symptoms, 43% had a type‐D personality (n = 26). Of the remaining 108 patients with CHF, only 14% (n = 16) had a type‐D personality (fig 1). Additionally, there was a significant effect for lower educational level (OR 4.2; 95% CI 1.1 to 16.0, p<0.05).

Figure 1 Percentage of patients with chronic heart failure (CHF) with a type‐D personality, stratified by cardiac symptoms and consultation behaviour. Sympt(−), percentage of patients with a type‐D personality without relevant cardiac symptoms; Sympt(+)/Consult(+), percentage of patients with a type‐D personality with relevant cardiac symptoms who succeed to consult; Sympt(+)/Consult(−), percentage of patients with a type‐D personality with relevant cardiac symptoms who fail to consult.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first prospective study to investigate the role of personality, and type‐D personality in particular, as a determinant of self‐management behaviour in patients with CHF. The present findings indicated that patients with a type‐D personality experienced more cardiac symptoms at follow‐up than patients with a non‐type‐D personality. Patients with a type‐D personality also reported high levels of worries about health, indicating that they appraise these symptoms as serious. Paradoxically, however, patients with a type‐D personality were less likely to contact their doctor or nurse. Hence, patients with a type‐D personality are at risk for failing to report their increases of CHF symptoms to healthcare professionals, despite the fact that they appraise them as worrisome.

Previous studies have shown the adverse effect of type‐D personality on prognosis in patients surviving myocardial infarction,15,19 in patients with decreased LVEF20 and in patients who were treated with percutaneous coronary intervention.21 Although there is preliminary evidence that immune activation22 or dysfunctional stress reactivity23 may comprise a link between type‐D personality and cardiac events, the underlying mechanisms responsible for the association between type‐D and cardiac prognosis are largely unknown. The results of the current study indicate another possible, behavioural, link between type‐D personality and prognosis—that is, inadequate consultation behaviour.

Patients with a type‐D personality do not have psychopathology as such, but are characterised as being high on both social inhibition and negative affectivity.15,16 Socially inhibited individuals often report to be socially isolated or to lack a close confidant. Social isolation has been associated with adverse outcome in patients with heart disease,24 and this association cannot be explained by factors such as disease severity, demographic variables and distress.25 Social inhibition may result in non‐adherence to treatment. Dickens et al26 found that patients with coronary heart disease without a close confidant were more likely to have further cardiac events, and speculated that these patients may be less likely to seek treatment for heart disease, thereby increasing the risk of adverse clinical outcome. One aspect of social inhibition is feeling insecure and less competent when communicating with others.15,16 Socially inhibited patients may fear rejection or a negative reaction from their doctor, and may, for this reason, not go to see a doctor when it is necessary. Furthermore, as Pereira et al27 stated, there may be a mediating role for passive coping strategies, such as denial, in the relationship between inhibition and poor adherence to treatment. Therefore, patients with a type‐D personality may have a somewhat more passive and avoidant coping style while dealing with upcoming problems.

Apart from inhibition, negative mood states are related to poor prognosis28,29 as well as to unhealthy behaviours.30,31,32 In a recent study by van der Wal et al,32 for instance, it was found that compliance in CHF was negatively related to depressive symptoms. The results of our study indicate that type‐D personality is a risk factor for the delay to consult a doctor or nurse, despite clinically evident symptoms of CHF and associated high levels of worries about health.

This study has a number of limitations. First, there may be a bias in the selection of patients. Cardiologists or heart failure nurses asked patients to participate in the study. So the interaction pattern may influence the selection. Second, the follow‐up period is relatively short. It would be interesting to look at the impact of type‐D personality on long‐term self‐management behaviour and to investigate whether self‐management, and consultation behaviour in particular, comprises a mechanism linking type‐D personality to adverse prognosis. Third, data on self‐management were obtained by means of a self‐report questionnaire, and self‐reports may be prone to socially desirable behaviour. However, as Jaarsma et al18 indicate, the EHFScBS is a valid and reliable scale to measure the self‐management behaviours of patients with CHF. The strength of the current study is that it is the first to examine the role of personality in consultation behaviour, an aspect of self‐management, in patients with CHF, in a prospective design.

In conclusion, the results of the current study show that patients with CHF with a type‐D personality are less likely to seek medical assistance in the case of increased cardiac symptoms in contrast with patients with a non‐type‐D personality. Paradoxically, patients with a type‐D personality do experience more cardiac symptoms and worry more about these symptoms. Because of the still increasing healthcare costs associated with chronic illness,33 it is important to identify determinants of high hospital and mortality rates in several patient groups. Improved self‐management may help reduce hospitalisation among patients with CHF.34 Further research on the role of personality factors in self‐management behaviour, healthcare utilisation and prognosis is warranted. Finally, as Jones35 mentions, self‐management is an essential component of the management of chronic illness and the quality of self‐care is important for the quality of life of patients. This means that it is important to know which patients with CHF need more intensive interventions, such as more education, to improve self‐management abilities. The findings of the present study suggest that patients with a type‐D personality may be in need of such a behavioural intervention programme.

Acknowledgements

AAS thanks H Broers, heart failure nurse, for his assistance in data collection.

Abbreviations

CHF - chronic heart failure

DS14 - Type‐D Personality Scale

EHFScBS - European Heart Failure Self‐care Behaviour Scale

HCS - Health Complaints Scale

KMO - Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin

LVEF - left ventricular ejection fraction

NYHA - New York Heart Association

PCA - principal component analysis

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by grants from Medtronic, St Jude Medical and the Netherlands Heart Foundation (#2003B038).

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Newman S, Steed L, Mulligan K. Self‐management interventions for chronic illness. Lancet 20043641523–1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krumholz H M, Parent E M, Tu N.et al Readmission after hospitalization for CHF among Medicare beneficiaries. Arch Intern Med 199715799–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krum H. The task force for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic heart failure (update 2005). Eur Heart J 2005262472–2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juenger J, Schellberg D, Kraemer S.et al Health related quality of life in patients with congestive heart failure: comparison with other chronic diseases and relation to functional variables. Heart 200287235–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Heart Association Heart disease and stroke statistics—2005 update. Dallas, TX: American Heart Association, 2004

- 6.Krumholz H M, Amatruda J, Smith G L.et al Randomized trial of an education and support intervention to prevent readmission of patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 20023983–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barlow J, Wright C, Sheasby J.et al Self‐management approaches for people with chronic conditions: a review. Patient Educ Couns 200248177–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dean K. Self care components of life styles. The importance of gender, attitudes and the social situation. Soc Sci Med 198929137–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ekman I, Cleland J G F, Andersson B.et al Exploring symptoms in chronic heart failure [editorial]. Eur J Heart Fail 20057699–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Facione N C. Delay versus help seeking for breast cancer symptoms: a critical review of the literature on patients and provider delay. Soc Sci Med 1993361521–1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crosland A, Jones R J. Rectal bleeding: prevalence and consultation behaviour. BMJ 1995311486–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng C. Seeking medical consultation: perceptual and behavioral characteristics distinguishing consulters and non‐consulters with functional dyspepsia. Psychosom Med 200062844–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenfeld A G. Treatment‐seeking delay among women with acute myocardial infarction: decision trajectories and their predictors. Nurs Res 200453225–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perry K, Petrie K J, Ellis C J.et al Symptom expectations and delay in acute myocardial infarction patients. Heart 20018691–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Denollet J, Vaes J, Brutsaert D L. Inadequate response to treatment in coronary heart disease: adverse effects of type‐D personality and younger age on 5‐year prognosis and quality of life. Circulation 2000102630–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denollet J. DS14: standard assessment of negative affectivity, social inhibition, and type‐D personality. Psychosom Med 20056789–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Denollet J. Health complaints and outcome assessment in coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med 199456463–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaarsma T, Strömberg A, Mårtensson J.et al Development and testing of the European Heart Failure Self‐Care Behaviour Scale. Eur J Heart Fail 20035363–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Denollet J, Sys S U, Brutsaert D L. Personality and mortality after myocardial infarction. Psychosom Med 199557582–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Denollet J, Brutsaert D L. Personality, disease severity, and the risk of long‐term cardiac events in patients with decreased ejection fraction after myocardial infarction. Circulation 199897167–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pedersen S S, Lemos P A, van Vooren P R.et al Type‐D personality predicts death or myocardial infarction after bare metal stent or sirolimus‐eluting stent implantation. A Rapamycin‐Eluting Stent Evaluation At Rotterdam Cardiology Hospital (RESEARCH) registry sub‐study. J Am Coll Cardiol 200444997–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denollet J, Conraads V M, Brutsaert D L.et al Cytokines and immune activation in systolic heart failure: the role of type‐D personality. Brain Behav Immun 200317304–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Habra M E, Linden W, Anderson J C.et al Type‐D personality is related to cardiovascular and neuroendocrine reactivity to acute stress. J Psychosom Res 200355235–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King K B. Psychologic and social aspects of cardiovascular disease. Ann Behav Med 199719264–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brummett B H, Barefoot J C, Siegler I C.et al Characteristics of socially isolated patients with coronary artery disease who are at elevated risk for mortality. Psychosom Med 200163267–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dickens C M, McGowan L, Percival C.et al Lack of a close confidant, but not depression, predicts further cardiac events after myocardial infarction. Heart 200490518–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pereira D B, Antoni M H, Danielson A.et al Inhibited interpersonal coping style predicts poorer adherence to scheduled clinic visits in human immunodeficiency virus infected women at risk for cervical cancer. Ann Behav Med 200428195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buerki S, Adler R H. Negative affect states and cardiovascular disorders: a review and the proposal of a unifying biopsychosocial concept. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 200527180–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strik J J M H, Denollet J, Lousberg R.et al Comparing symptoms of depression and anxiety as predictors of cardiac events and increased health care consumption after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003421801–1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newman S. Engaging patients in managing their cardiovascular health. Heart 2004909–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ziegelstein R C, Fauerbach J A, Stevens S S.et al Patients with depression are less likely to follow recommendations to reduce cardiac risk during recovery from a myocardial infarction. Arch Intern Med 20001601818–1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van der Wal M H L, Jaarsma T, Moser D K.et al Compliance in heart failure patients: the importance of knowledge and beliefs. Eur Heart J 200627434–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoffman C, Rice D, Sung H Y. Persons with chronic conditions. Their prevalence and costs. J Am Med Assoc 19962761473–1479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Artinian N T, Magnan M, Sloan M.et al Self‐care behaviours among patients with heart failure. Heart Lung 200231161–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones R. Self care. BMJ 2000320596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]