Abstract

This review examines research findings in patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis in light of the current debate about this chronic multiple‐symptom, multiorgan, multisystem illness and the conflicting views in medicine. These issues cannot be separated from the political opinions and assertions that conflict with science and medicine, and will be part of this review as they have enormous consequences for scientific and medical research, patients, clinicians, carers and policy makers.

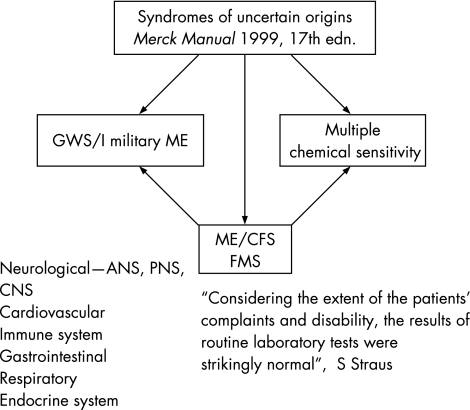

Syndromes of uncertain origin reported in the medical literature include myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), among several others1 (fig 1). These syndromes give rise to constellations of similar symptoms, and affect all the major systems and organs of the body. Gulf War syndrome has been labelled the myalgic encephalomyelitis of the military, and is a frequent diagnosis in the medical records of veterans of the first Gulf War, where it is commonly named as CFS. Despite the acknowledged complaints and disabilities of patients, routine blood tests are surprisingly normal, an indication these syndromes are outside the experience of many modern clinicians and medical administrators.

Figure 1 Inter‐relation of several syndromes of uncertain origin. ANS, autonomic nervous system; CNS, central nervous system; FMS, fibromyalgia syndrome; GWS/I, first Gulf War syndrome; ME, myalgic encephalomyelitis; ME/CFS, myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome; PNS, peripheral nervous system.

The number of these overlapping syndromes continues to increase (table 1)—for example, the recent addition of aerotoxic syndrome.2

Table 1 Symptoms, systems and organs affected by overlapping syndromes of uncertain origin.

| Symptoms | OPs | GWS/I | MCS | FMS | CFIDS | MS | HIV/AIDS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joint pain | + | + | + | Around joint area | + | + | + |

| Fatigue | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Headache | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Memory problems | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Disturbed sleep | + | + | + | + | + | Due to medicines | + |

| Skin problems | + | + | + | + | + | Burning skin | + |

| Concentration problems | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Depression | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Muscle pain | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Dizziness | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| GI–Irr Bow | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Periph parethes/tingling | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Chem/envr sensitivity | + | + | + | + | + | Reported | _ |

| Eye problems | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Anxiety | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Tachycardia or chest pain | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Breathing problems | + | + | + | Reported | + | + | + |

| Light sensitivity | +/− | + | + | Reported | + | + | – |

CFIDS, chronic fatigue immune dysregulation syndrome; FMS, fibromyalgia syndrome; GI‐Irr Bow, gastro‐intestinal –irritable bowel; GWS/I, Gulf War syndrome/illness; MCS, multiple chemical sensitivity; MS, multiple sclerosis; OP, organophosphate poisoning; +, symptom(s) present; –, symptom(s) absent.

The inclusion of MS and HIV/AIDS in this group (table 1) points to a common disturbance of both the immune and nervous systems. An ill‐founded alternative approach offers a common psychiatric explanation for these syndromes.3

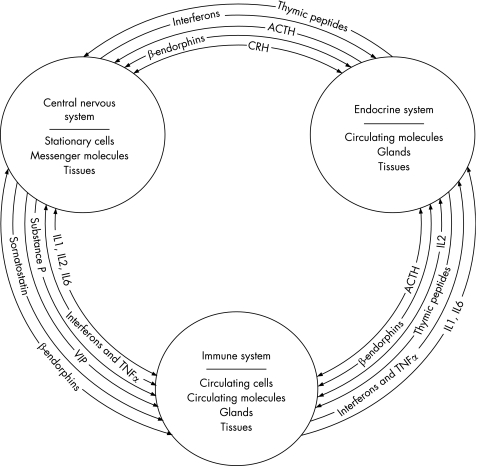

The challenge of these syndromes to modern medicine is in accord with the growing understanding of the neuroendocrine immune paradigm, sometimes referred to as the psychoneuroimmune paradigm. This has emerged as a result of the identification of complex biological messenger molecules that serve to communicate between these neuroendocrine immune systems (fig 2).

Figure 2 The neuroendocrine immune comprehensive integrative defence system.40 ACTH, adrenocortiotrophic hormone; CRH, cortiotrophin‐releasing hormone; IL, interleukin; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; VIP, vasoactive intestinal peptide.

This understanding, supported by extensive human and animal studies, provides an extensive intellectual foundation for the biological approach to investigating these complex and challenging syndromes of uncertain origin. By contrast, the disputed claims of some psychiatrists that all these syndromes are expressions of somatisation3 or are exemplified by the biopsychosocial theory lack an intellectually sound basis, and spell the failure and possible imminent extinction of modern psychiatry.4,5,6

“I see psychiatry under attack from all quarters. Some people see a great future for us. I don't share that view. I believe there is a serious risk that psychiatry, as we know it, will no longer exist in as little as fifteen years. The reason is simply a lack of anything approximating an adequate intellectual framework for our efforts.”4

Per Dalen, a Professor of Psychiatry in Sweden, states “Somatic Medicine abuses Psychiatry and neglects causal research.”

“It must be noted that there is no proof that it is justified to apply the label somatisation to such conditions as chronic fatigue syndrome and several more illnesses that established medicine has so for failed to explain scientifically. ……Don't hesitate to ask questions about scientific evidence behind this talk about somatisation. Be persistent, because a diagnosis of somatisation is definitely not an innocuous label. It will close various doors and lead (to) treatments that usually get nowhere.”7

Nomenclature and definitions

The term “myalgic encephalomyelitis” (muscle pain, “myalgic”, with “encephalomyelitis” inflammation of the brain and spinal cord) was first included by the World Health Organization (WHO) in their International Classification of Diseases in 1969. It is ironic that Donald Acheson, who subsequently became the Chief Medical Officer first coined the name in 1956.8

In 1978 the Royal Society of Medicine accepted ME as a nosological organic entity.9 The current version of the International Classification of Diseases—ICD‐10, lists myalgic encephalomyelitis under G.93.3—neurological conditions. It cannot be emphasised too strongly that this recognition emerged from meticulous clinical observation and examination.

The contrasting view of myalgic encephalomyelitis as mass hysteria originated with the work of Beard and McEvedy in 197010. It is a matter of record, since both authors are now dead, that Byron Hyde visited McEvedy to discuss his thesis and to meet people involved in the Royal Free outbreak. McEvedy stated that he did not examine any patients and undertook only the most cursory examination of medical records. This was a source of great distress to Melvin Ramsay who carried out the first meticulous study of the Royal Free outbreak11. The outcome of McEvedy's work has been described by one of the ME/CFS charities as “the psychiatric fallacy”12.

None of the participants in creating the 1988 CFS case definition and name ever expressed any concern that it might TRIVIALISE the illness. We were insensitive to that possibility and WE WERE WRONG.13

Myalgic encephalomyelitis is still included under G.93.3, with the only alternatively allowed names being CFS and post‐viral fatigue syndrome.

The introduction of the word “fatigue” has provided ample scope for error and confusion. It was only as a result of a challenge launched through a debate in the House of Lords14,15 that the Minister for Health, Lord Warner, conceded that mistakes had been made in the official documents circulated to general practitioners and policy makers. These were to be corrected. To my knowledge, this has not yet been done. Today, many patients with fatigue as a major feature of their illness—for example, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, depression—are being diagnosed with CFS. This has led to confusion, and has left clinicians, patients and carers without recourse to proper clinical and social support. In the case of children and young people, parents have been accused of Munchausen syndrome by proxy and legal proceedings initiated to remove children from parental care. In 1999 the respected paediatrician Nigel Speight, who specialises in ME, described the overdiagnosis of Munchausen syndrome by proxy in these parents as an “epidemic”.16 In 2001 the Countess of Mar wrote, “To accuse parents of abuse, on the evidences of ME, is a misdiagnosis and distressing for families … Is it not time for doctors and social workers to stop using care orders as a back door to enforce medical treatment on children with ME?”17 Several legal cases have been reported in the British Medical Journal, culminating in a policy document from the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health that declares, “We believe that far more children and young people with severe CFS/ME fall into the category of ‘a child in need' than ‘in danger'. A referral [to social services] is likely to be destructive if based on flimsy or ill‐reasoned evidence.”18 A common treatment programme advocated for CFS, whatever its origins, consists of pacing, cognitive‐behavioural therapy (CBT) and graded exercise therapy (GET). The UK government has spent huge sums of money (£8.2 million) on setting up clinics, manned by psychiatrists and located in psychiatric hospitals, to which patients with CFS are commonly referred. Such an approach has been vehemently opposed by patients and carers. Studies among the “25% group”, whose members have severe disabling myalgic encephalomyelitis, which leaves them housebound or bed‐bound, found that more than 90% of its members were dissatisfied with CBT and GET19,20,21 (table 2). Other reports have found little or no effect with CBT, whereas GET is often positively harmful.

Table 2 “25% group” questionnaire responses: random sample (n = 437; 66%) of membership.

| Procedure | Helpful | Unhelpful |

|---|---|---|

| Person‐centred counselling | 54 | 46 |

| Psychotherapy | 10 | 90 |

| CBT | 7 | 93 |

| GET | 5 | 95 |

| Pacing | 70 | 30 |

| Alternative treatments | 60 | 40 |

| Symptomatic care management | 73 | 27 |

| Pain management | 75 | 25 |

CBT, cognitive‐behavioural therapy; GET, graded exercise therapy.

Responses as percentages of the total sample.

Despite rejection of these advocated treatments, their promulgators persist in insisting that they are effective, and sometimes even disparage patients and talk of their having “perfectionist personalities, maladaptive beliefs and laziness”.22 One paper23 speaks of psychological amplification of biological sensitisation and counsels patients, “do not listen to your own body's signals, do not trust your feelings, do not trust your thoughts”. Presumably, the doctor should adopt a similar attitude! How then would it ever be possible to obtain a thorough history?

In a recent Australian editorial,24 it was emphatically asserted that “one can safely conclude from these studies that graded physical exercise should become a cornerstone of the management approach for patients with CFS.” Another paper25 confidently asserted that “Graded exercise appears to be an effective treatment for CFS and it operates in part by reducing the degree to which patients focus on their symptoms.” These claims were later rejected, when it was shown that “[CFS patients] are not deconditioned. Neither their muscle strength nor their exercise capacity is different from … other sedentary members of the community. We remain unaware of any incontrovertible evidence … [that] various ‘exercise training' programs suggested in the previous article improve neither physiological, nor psychological, nor clinical status of people with CFS.”26 A common claim that ME/CFS equates to clinical burnout found in athletes is also unsustainable, as the changes in cortisol levels in burnout cases are the opposite of those found in patients with ME.27

The current most widely used definition of CFS is that formulated by the Centers for Disease Control in 1994. This definition lacks clarity and mentions few clinical signs. It has been challenged by others who call for subtypes28 to be recognised among patients with ME/CFS. One recent clinical study showed marked differences between patients with ME/CFS and Gulf War veterans (GWVs), and organophosphate‐poisoned farmers who share many common symptoms.29

The definition by the Centers for Disease Control 1994 is one of exclusion and delay, with a confusing emphasis on fatigue. A group of Canadian clinicians with extensive experience of ME/CFS, with others from the USA and one from Europe, have jointly written The Canadian Consensus Document for ME/CFS, 2003.30 This authoritative document emerged from extensive clinical engagement with patients with ME/CFS involving thousands of hours of history taking and intensive clinical investigation, and was endorsed by the whole group before release. Two senior consultants in the UK have endorsed the consensus document, and a summary entitled, “A clinical case definition and guidelines for medical practitioners” was circulated with the information for this conference.31 It is no longer possible for any clinician in UK to assert that there are no valid clinical tests for doctors to use when investigating patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis. The consensus document lists clinical signs that deal with the neurological, immunological and endocrinological dysfunction and damage in patients with ME/CFS that are consistent with the many symptoms described by patients with ME/CFS.

Recent biomedical research

Enteroviruses

An important review32 concludes that

“Enteroviruses are well known causes of acute respiratory and gastrointestinal infections, with tropism for the central nervous system, muscle, and heart. Initial reports of chronic enteroviral infections causing debilitating symptoms in patients with CFS were met with skepticism, and largely forgotten for the past decade … Recent evidence not only confirmed the earlier studies but also clarified the pathological role of viral RNA through antiviral treatment.”

The following points confirm the aetiology, viral persistence, symptom fluctuation, multiorgan damage and possible effective treatment reported in earlier studies:11,32

A severe flu‐like illness occurs in most cases of CFS, suggesting that an infection triggers and possibly perpetuates this syndrome.

Common viral infections and unusual causes of CFS could be diagnosed on the basis of the details of the initial flu‐like illness, if present, epidemiological history and early virological testing.

Different laboratories from Europe and, recently, from the USA have found enteroviral RNA in the tissues, including peripheral blood mononuclear cells and muscles, of patients with CFS.

-

Viral persistence through the formation of stable double‐stranded RNA reconciles the two opposing observations of the past two decades:

-

-

the absence of live virions in chronically infected patients and animals and

-

-

the presence of enteroviral RNA in the blood or other tissues.

-

-

Smouldering viral infection of various cells with continuous expression of double‐stranded RNA and viral antigens could result in a chronic inflammatory state in the local tissues, accounting for the diverse symptoms.

Interferon alpha and interferon gamma act synergistically against enteroviruses in vitro, and preliminary studies suggest that this combination may be an effective treatment for patients with chronic enteroviral infection.

In Easter 1990, a major symposium took place in Cambridge, UK, and brought together clinicians and scientists who had worked and continue to work on this perplexing illness; together they represent a unique group of experts in this field.33 Foremost among them was Dr John Richardson. The published proceedings of the conference,33 74 chapters that cover all aspects of ME/CFS, identify it as a multiple‐symptom, multisystem and multiorgan illness. Many clinical studies and diagnostic procedures have been reported (for example, single‐photon emission computed tomography, photon emission computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging scans), and a variety of treatments. John Richardson's major work was published in 2001, one year before he died.34 His work emphasises the extensive role of enteroviruses and their effects on the major systems and organs of the body; reports recorded blood flow in the brain with extensive hypofusion in the brain stem and some parts of the cortex that are markedly different from endogenous depression.

Also reported are reduced blood flow through the insula cortex, which controls visceral functions and integrates autonomic information, and in younger patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis, reduced blood flow in the left temporal lobe, which controls access to language.35 Magnetic resonance spectroscopy identified increased levels of free choline in the brain, which is consistent with a response to an infection resulting in increased breakdown of cell membranes that would cause loss of function.36,37,38 This powerful technique provides a discriminating procedure for the diagnosis of a different pattern chemical damage found in GWVs.

Richardson also recognised that the common symptoms found in patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis occurred in others exposed to chemical toxins, especially organochlorines such as lindane.39 Other scientists have also identified this link. Parkinsonian‐like symptoms consistent with damage to the basal ganglia were identified in one young patient,34 showing a link with the multiple biological and chemical exposures experienced by GWVs. If the knowledge presented in the two major works33,34 had been attended to and the unsound psychiatric theories of ME/CFS countered with the careful clinical and scientific studies described in them, then much pain and suffering may have been avoided.

Cardiovascular effects

A major research group, formed by Richardson, continues to investigate questions surrounding ME/CFS, and contributors to this informal group have shown how enteroviruses affect the heart.41,42 Subsequently, Peckerman et al43 described abnormal effects on the heart in patients with ME/CFS, which led to the formulation of a useful treatment regimen.44

Extensive damage to the cardiovascular system has been identified by the group at Dundee, which showed severe oxidative stress in the endothelium, leading to swelling and stiffening.45,46,48 In one study, this high level of oxidative stress distinguished patients with ME/CFS from pesticide‐poisoned farmers and GWVs.29 The identification of this inflammatory condition is consistent with an encephalitis rather than an encephalopathy, which is an alternative name being used and canvassed by some ME/CFS groups. Isoprostanes derived from fatty‐acid metabolism were key markers used in these studies. Earlier, oxidative stress resulting from dysfunctional xenobiotic metabolism was found to be common among patients with ME/CFS.48 One marker of this inflammatory condition is high‐sensitivity C reactive protein, which correlates with the level of damage in patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis.49 Damage to the endothelium in blood vessels supplying the brain, spinal cord and nerves would result in extensive neurological dysfunction. Recently, a post‐mortem examination of a person who died from myalgic encephalomyelitis found nothing amiss until the spinal cord was examined, where severe inflammation was found.50 Any activities associated with increased free‐radical production should not be recommended to patients with ME/CFS, as this will intensify the damage. GET is severely damaging for many patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis, as exercising muscle is known to generate increased oxidative stress.51

Immunology

Mechanisms that underlie the complex immune responses to both viruses, other microorganisms,52 and various chemicals53 have recently been uncovered with the identification of interferon‐induced RNase enzymes, RNase‐L. A dysfunctional form of this enzyme plays a key role in an aberrant immune response to intracellular microorganisms. This includes all viruses and microbes that have been implicated in myalgic encephalomyelitis, entero‐ and herpes viruses, parvoviruses, mycoplasmas, chlamydiae, rickettsiae and Borrelia spp, which some feel are major causative organisms in ME/CFS. These insights into RNase‐L provide a common mechanism for reactions to a bewildering variety of microorganisms and chemicals, and suggest possible novel treatments, most notably in the development of ampligen. Another major feature of patients with myalgic encephalomyelitis is the low cytotoxicity of circulating natural killer cells, with less effective killing of viruses.54

Genetics

The emerging genetic studies on ME/CFS have affirmed and complemented the earlier studies that characterise the complex and far‐reaching nature of the illness. An extensive monograph has described the early T‐cell activation‐1 gene and its gene product osteopontin paradigm.55 This gene and its product have a vital role in initiating the response to infection by viruses (picornaviruses, herpes and HIV) and other microorganisms (including chlamydiae, coxiellae, rickettsiae and mycobacteria); autoimmune disease; cellular motility and communication; the regulation of phosphate and calcium metabolism, and bone growth and development; and numerous other body systems, including bone, joints and tendons, skin, kidney, heart, blood vessels, gastrointestinal system, lungs, central nervous, reproductive and auditory systems; and neoplasia. The widespread distribution and expression of the early T‐cell activation‐1 gene and its gene product osteopontin complex is consistent with the complex and extensive features of ME/CFS and provides a basis for a greater understanding of this illness.

A more recent and comprehensive genetic study56 that examined 9522 genes showed marked changes in the expression of 16 human genes in patients with ME/CFS. Fifteen genes were upregulated and one was downregulated. These were associated with T‐cell activation, neuronal function, mitochondria, transcription, translation, the cell cycle and apoptosis; some of the genes have, at present, no clearly identified function. An important feature of this study was the use of Taqman technology to perform real‐time polymerase chain reaction, after the preparation of cDNA from the original isolated mRNAs.57

Given all the issues around patient selection and the presence of many genes that are yet to be associated with specific functions, this paper is impressive and provides confirmation of the long‐established, but until recently ignored, pioneering work of Ramsay,58 Richardson34 and Dowsett.59 The upregulated neuropathy target esterase, NTE, gene has an important role in neuronal function56,57 and is significant for Gulf War syndrome. NTE affords protection against poisoning by exposure to cholinesterase inhibitors (sarin, organophosphate pesticides and pyridostigmine bromide) that were a feature of the first Gulf War.60

There can be little doubt now that myalgic encephalomyelitis is correctly described as an encephalitis associated with upregulation of pro‐inflammatory immune responses, with downregulation of suppressor cytokines. This, coupled with the association of NTE gene, validates the WHO nomenclature and classification under neurology that allows the alternative name of post‐viral fatigue syndrome. It is heartening that syndromes of uncertain origin (fig 1) are now seen to have a common basis that provides a much better understanding of these complex illnesses.

Undoubtedly, the perverse use of CFS, to impose a psychiatric definition for ME/CFS by associating it with fatigue syndromes, has delayed research, the discovery of effective treatment(s), and care and support for those with this illness.61

I propose that the use of CFS should now be abandoned and that, following the Minister of Health's assurances, the WHO definition is now accepted and used in all official documentation. The excellent work on the biological aspects of myalgic encephalomyelitis, already performed by several leading research groups, now requires considerable funding that will hasten the day when this complex illness and related syndromes are much better understood.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations

CBT - cognitive‐behavioural therapy

CFS - chronic fatigue syndrome

GET - graded exercise therapy

ME myalgic encephalomyelitis -

ME/CFS - myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome

WHO - World Health Organization

Footnotes

iThis was an initiative of the Norfolk and East Anglia ME Association. Copies are available at cost from Jeff@EastAnglia.ME.uk

iiThis paper builds on the Peckerman paper, and using tests to evaluate ATP synthesis, translocation and utilisation provides a coherent basis for treatment with ribose, l‐carnitine, CoQ 10, niacinamide and magnesium

Competing interests: None.

My thanks to Margaret Williams and Horace Reid for their help with the preparation of this document.

References

- 1.Beers M H. ed. Merck manual. Millennium edition. Merck, Sharpe and Dohme: Rahwey, New Jersey, USA 1999

- 2.Winder C. ed. Proceedings of the BALPA Air Safety and Cabin Air Quality International Aero Industry Conference; 20–21 April 2005, London, Sydney, Australia: BALPA and the School of Safety Science, University of New South Wales 2005

- 3.Wessely S, Nimnuan C, Sharpe M. Functional somatic syndromes: one or many? Lancet 1999354936–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLaren N. The biopsychosocial model and scientific fraud. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 200135724–730.11990882 [Google Scholar]

- 5.McLaren N. The biopsychosocial model in psychiatry. The future of psychiatry: a critical analysis of the scientific status psychiatry. 2005. http://www.futurepsychiatry.com (accessed 10 Aug 2006)

- 6.McLaren N. When does ignorance become fraud? The future of psychiatry: a critical analysis of the scientific status of psychiatry. 2003. http://www.futurepsychiatry.com (accessed 10 Aug 2006)

- 7.Dalen P. Somatic medicine abuses psychiatry and neglects causal research. http:art‐bincom/art/dalen_en.html. (Accessed 4 Jan 2003)

- 8.Anon A new clinical entity [leading article]? Br Med J 195626789–790. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lyle W H, Chamberlain R N. eds. Epidemic neuromyasthenia 1934–1977. Postgrad Med J 197854637, 707–637, 774. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McEvedy C P, Beard A W. Royal Free epidemic of 1955. A reconsideration. Br Med J 197017–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hyde B M. A new and simple definition of myalgic encephalomyelitis and a new and simple definition of chronic fatigue syndrome & a brief history of myalgic encephalomyelitis & an irreverent history of chronic fatigue syndrome. Presentation to the Invest in ME Conference, 12 May, 2006. http://www.investinme.org/Documents/PDFdocuments/Byron%20Hyde%20Little%Red%20Book%20for%2.www.investinme.org.pdf (Accessed 12 April 2007)

- 12.Sykes R, Campion P. Preliminary report: chronic fatigue syndrome/ME: trusting patients' perceptions of a multi‐dimensional physical illness. A collaborative report from Westcare

- 13.Komaroff A. http://www.cfidsreport.com/Articles/NIH/NIH_CFS_4.htm (accessed April 2007) Quoted in “Energising biomedical research in ME/CFS”, a lecture by Dr Vance Spence, Chairman of Mar MERGE. http://www.meresearch.org.uk (accessed 10 Aug 2006)

- 14. Debate on “Does the government accept the WHO definition of myalgic encephalomyelitis?” Countess of 22 March Jan 2004. http://listserv.nodak.edu/scripts/wa.exe?A2 = ind0401d&L = co‐cure&F = &S = &P = 1313 (accessed 10 Aug 2006)

- 15.Hooper M, Members of the ME Community The mental health movement: persecution of patients? http://www.satori‐5.co.uk/word_articles/me_cfs/prof_hooper_3.html (accessed 10 Aug 2006)

- 16.ME Association Perspectives. ME Association: Buckingham, UK 1999

- 17.The Countess of Mar How the law is being abused to force the treatment on children [opinion]. The Daily Telegraph 11 July 2001

- 18.Royal College of Pediatrics and Child Health Evidence‐based guidelines for the management of CFS/ME in children and young people, 2004. Available at http://www.ayme.org.uk/article.php?sid = 10&id = 137 (accessed 12 April 2007)

- 19. 25% Group. March 2004 severe ME analysis report. http://www.25megroup.org/Group%20Leaflets/Group%20Leaflets.htm (accessed 1 April 2007)

- 20.Crowhurst G. 25% Group September 2005 Severly affected and graded excreise http://www.25megroup.org/Group%20Leaflets/Group%20Leaflets.htm (accessed 1 April 2007)

- 21. 25% Group. End the PACE/FINE trials. http://www.25megroup.org/, news

- 22.Wessely S, Butler S, Chalder T.et al In: Cox R, Edwards F, Palmer K, eds. Fitness for work; the medical aspects. 3rd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000

- 23.Wilhelmsen I. Biological sensitization and psychological amplification: gateway to subjective health complaints and somatoform disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology 200530990–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lloyd A R. To exercise or not to exercise in chronic fatigue syndrome? No longer a question. Med J Aust 2004181437–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moss‐Morris R, Sharon C, Tobin R.et al A randomised controlled graded exercise trial for chronic fatigue syndrome: outcomes and mechanisms of change. J Health Psychol 200510245–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scroop G C, Burnett R B. To exercise or not to exercise in chronic fatigue syndrome – a response. Med J Aust 2004181578–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mommersteeg P M C, Heijen C J, Verbraak M J P M.et al Clinical burnout is not reflected in the cortisol awakening response, day‐curve, or response to low‐dose dexamethasone test. Psychoneurendocrinology 200531216–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jason L A, Corradi K, Torres‐Harding S.et al Chronic fatigue syndrome: the need for subtypes. Neuropsychology 20051529–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kennedy G, Abbot N C, Spence V.et al The specificity of the CDC‐1994 criteria for chronic fatigue syndrome: comparison of health status in three groups of patients who fulfill the criteria. Ann Epidemiol 20041495–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carruthers B, Jain A, De Meirleir K.et al Canadian Clinical Working Group: case definition, diagnostic and treatment protocols. J Chronic Fatigue Syndrome 2003117–115. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carruthers B M, van de Sande M I.Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: a clinical case definition and guidelines for medical practitioners (an overview of the Canadian Consensus Document). Carruthers and van de Sande Calgoy: 2005

- 32.Chia J K S. The role of enteroviruses in chronic fatigue syndrome – a review. J Clin Pathol 2005581126–1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hyde B M, Goldstein J, Levine P.The clinical and scientific basis of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Ottawa: Nightingale Research Foundation, 1992

- 34.Richardson J.Enteroviral and toxin mediated myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome and other organ pathologies. Binghampton, New York: Haworth Medical Press, 2001

- 35.Robotham J. Brain link to fatigue syndrome. The Sydney Morning Herald, 4 May 2002. http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2002/05/03/1019441434909.html (accessed 10 Aug 2006)

- 36.Puri B K, Counsell S J, Zaman R.et al Relative increase in choline in the occipital cortex in chronic fatigue syndrome. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2002106224–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chaudhuri A, Condon B R, Gow J W.et al Proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of basal ganglia in chronic fatigue syndrome. Brain Imaging Neuroreport 200314225–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chaudhuri A, Behan P O. In vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy in chronic fatigue syndrome. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fat Acids 200471181–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richardson J. Four cases of pesticide poisoning presenting as “ME”, treated with a choline ascorbic acid mixture. J Chronic Fatigue 2000611–21. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rowat S C. Environ Health Perspect. 1998;106 (Suppl 1):S85–109. doi: 10.1289/ehp.98106s185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reetoo K N, Osman S A, Illavia S J.et al Quantitative analysis of viral RNA kinetics in coxsackievirus B3–induced murine myocarditis: biphasic pattern of clearance following acute infection with persistence of residual viral RNA throughout and beyond the inflammatory phase of disease. J Gen Virol 2000812755–2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lane R J M, Soteriou B A, Zhang H.et al Enterovirus related metabolic myopathy: a postviral fatigue syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003741382–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peckerman A, Lamanca J J, Dahl K A.et al Abnormal impedance cardiography predicts symptom severity in chronic fatigue syndrome of disease. Am J Med Sci 200332655–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Myhill S. What is chronic fatigue syndrome? August 2005. http://www.drmyhill.co.uk

- 45.Spence V A, Stewart J. Standing up for ME. Biologist 20045165–70. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kennedy G, Spence V A, Underwood C.et al Increased neutrophil apoptosis in chronic fatigue syndrome. J Clin Pathol 200457891–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kennedy G, Spence V A, McLaren M.et al Oxidative stress levels are raised in chronic fatigue syndrome and are associated with clinical symptoms. Free Radic Biol Med 200539584–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spence V A, Khan F, Kennedy G.et al Inflammation and arterial stiffness in patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. 8th International IACFS Conference on Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Fibromyalgia and other related illnesses, Fort Lauderdale, Floride, USA, January, 2007

- 49.Spence V A. Advances in the biomedical investigation of ME Research Updates, May 2004. http://investinme.org/Documents/PDFdocuments/Advances%20in%20the%20Biomedical%20Investigation%20of%20ME.pdf

- 50.Sophia, ME The story of Sophia Mirza document provided at the Invest in ME Conference, 12 May 2006, London. DVDs of the presentations on can be obtained from htpp://www.investinme.org

- 51.McArdle F, Pattwell D M, Vasilaki A.et al Intracellular generation of reactive oxygen species by contracting skeletal muscle cells. Free Radic Biol Med 200539651–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chronic fatigue syndrome: a biological approach In: Englebienne P, De Meirleir K, eds. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, 2002

- 53.Vojdani A, Lapp C W. Interferon‐induced proteins are elevated in blood samples of patients with chemically/virally induced chronic fatigue syndrome. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol 199921175–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patarca‐Montero R, Mark T, Fletcher M A.et al In: De Meirleir K, Patarca‐Montero R, eds. Immunology of chronic fatigue syndrome in chronic fatigue syndrome critical reviews and clinical advances. London: Haworth Medical Press, 2000

- 55.Patarca‐Montero R.Chronic fatigue syndrome, genes, and infection: the eta‐1/Op paradigm. New York: Haworth Medical Press, 2003

- 56.Kaushik N, Fear D, Richards S C M.et al Gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with chronic fatigue syndrome. J Clin Pathol 200558826–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kerr J R, Binns J H. Presentation to the Invest in ME Conference, London, 12 May 2006. DVDs of the presentations on can be obtained from http://www.investinme.org

- 58.Ramsay A M.Myalgic Encephalitis and Post Viral Fatigue States. 2nd edn. London: Gower Publishing, 1988

- 59.Dowsett E G, Colby J. Long term sickness due to ME/CFS in UK schools. J Chronic Fatigue Syndrome 1997329–42. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Scientific progress in understanding Gulf War veterans' illnesses: report and recommendations of the Research Advisory Committee on Gulf War Veterans' Illnesses, RACGWI, November 2004. http://www1.va.gov/rac‐gwvi/docs/ReportandRecommendations_2004.pdf

- 61.Walker M J.Skewed: psychiatric hegemony and the manufacture of mental illness. London: Slingshot Publications, 2003

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.