Abstract

Background:

No pharmacotherapies have been shown to increase long-term (≥ 6 month) tobacco abstinence rates among smokeless tobacco (ST) users. Bupropion SR has demonstrated potential efficacy for ST users in pilot studies. We conducted a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trial to assess the efficacy and safety of bupropion SR for tobacco abstinence among ST users.

Methods:

Adult ST users were randomized to bupropion SR titrated to 150 mg twice daily (N = 113) or placebo (N = 112) for 12 weeks plus behavioral intervention. The primary endpoint was the 7-day point-prevalence tobacco abstinence rate at week 12. Secondary outcomes included prolonged and continuous tobacco abstinence rates, craving and nicotine withdrawal, and weight gain.

Results:

The 7-day point-prevalence tobacco abstinence rates did not differ between bupropion SR and placebo at the end treatment (53.1% vs 46.4%; odds ratio (OR) 1.3; p = 0.301). The 7-day point prevalence abstinence did not differ at weeks 24 and 52. The prolonged and continuous tobacco abstinence rates did not differ at weeks 12, 24, and 52. A time-by-treatment interaction was observed in craving over time with greater decreases in the bupropion SR group. At 12 weeks, the mean (±SD) weight change from baseline among abstinent subjects was an increase of 1.7 (±2.9) kg for the bupropion SR group compared to 3.2 (±2.7) kg for placebo (p = 0.005).

Conclusions:

Bupropion SR did not significantly increase tobacco abstinence rates among ST users, but it significantly decreased craving and weight gain over the treatment period.

Keywords: tobacco, smokeless; tobacco use cessation; bupropion

1. Introduction

In the United States, approximately 7.7 million individuals older than 12 years of age report current (past month) use of smokeless tobacco (ST) (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2006). ST use has been associated with oral mucosal lesions (Little et al., 1992; Martin et al., 1999; Tomar et al., 1997), periodontal disease (Ernster et al., 1990), and precancerous oral lesions (Mattson and Winn, 1989). Long-term ST use may increase the risk for oral cancer (Stockwell and Lyman, 1986) and cancer of the kidney (Goodman et al., 1986; Muscat et al., 1995), pancreas (Muscat et al., 1997), and digestive system (Henley et al., 2005). Associations between ST use and cardiovascular events (Teo et al., 2006) and death from coronary artery disease and stroke (Henley et al., 2005) have also been observed.

Given the adverse health consequences of ST use, the fact that 64% of ST users report the desire to quit (Severson, 1992), and the increasing promotion of ST as a potential harm reduction strategy for cigarette smoking (McNeill, 2004; 2006), the need exists to validate and disseminate effective behavioral and pharmacologic therapies for ST users. Behavioral approaches for treating ST users have been shown to be effective (Severson, 2003), but no pharmacotherapies have been shown to increase long-term (≥ 6 month) tobacco abstinence rates in this population of tobacco users (Ebbert et al., 2004). Bupropion sustained-release (SR) has been clearly demonstrated to increase tobacco abstinence among cigarettes smokers (Hughes et al., 2002). To date, two pilot studies have been conducted suggesting potential efficacy of bupropion SR for increasing tobacco abstinence rates among ST users (Dale et al., 2002; Ebbert et al., 2003; Glover et al., 2002).

The current study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy of bupropion SR for increasing tobacco abstinence among healthy ST users in a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. The study was conducted in Minnesota and West Virginia.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study was a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo- and active-treatment-controlled clinical trial with a 12-week treatment phase and blinded follow-up through 52 weeks. The study was conducted at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, and the West Virginia University School of Medicine in Morgantown, WV, in compliance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Enrollment took place between August, 2003, to May, 2005, and the study was completed in May, 2006. The institutional review board at each study site approved the study protocol prior to recruitment and enrollment.

2.2 . Study Population

ST users were recruited through press releases and media advertising. Subjects were eligible for inclusion in the study if they: were 18 years of age or older, used ST daily for at least one year, were in good general health, willing to complete all study procedures, willing to quit ST, and signed the informed consent. Subjects were excluded if they: had current major depression (past 30 days) as assessed by the National Institute for Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule-Revised (NIMH-DIS-R), depression module (Robins et al., 1981) or had a score of ≥ 20 on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) (Hamilton, 1960); had active alcoholism as assessed by the Self-Administered Alcohol Screening Test (SAAST) (Swenson and Morse, 1975); had a recent history of drug abuse as assessed by the Drug Abuse Screening Test 20 (DAST-20) (Skinner, 2001); had a recent history (past year) of active substance dependence on any agent other than nicotine (i.e., marijuana or other drugs); had current (past 30 days) use of antipsychotics, or any antidepressants; were currently (previous 30 days) using any other behavioral or pharmacologic tobacco treatment program; currently used ST tobacco other then loose leaf or moist snuff; used an investigational drug within the last 30 days; had unstable angina or myocardial infarction within the past three months; had another member of their household already participating in this study; had a contraindication to the use of bupropion (i.e., personal or family history of seizures, significant closed head injury, bulimia or anorexia nervosa); had an allergy to bupropion; or had been diagnosed with any cancer (except skin cancers) in the year prior to randomization.

We excluded potential subjects who had previously used bupropion in order to ensure adequate blinding. Potential subjects who were pregnant, lactating, or likely to become pregnant during the medication phase were also excluded because of unknown effects of bupropion on the unborn child.

2.3. Interventions

A computer-generated randomization sequence assigned subjects in a 1:1 ratio to receive active bupropion SR or placebo with a block size of four within four strata defined by the two stratification factors of site (Minnesota or West Virginia) and past history of major depressive disorder (MDD). A past history of MDD was assessed using the NIMH-DIS-R.

Subjects were randomly assigned to receive bupropion SR or matching placebo administered orally for 12 weeks. Bupropion SR 150 mg was titrated one tablet by mouth once per day for days 1 to 3 then one tablet by mouth twice per day for the remainder of the 12 weeks. The target quit date (TQD) was day 8. Participants, investigators, and study staff were blinded to treatment assignment.

All subjects received the first week of medication at the baseline visit (randomization) and instructed to take their first pill the next day. They also received an intervention manual developed specifically for ST users in our previous ST studies (Ebbert et al., In press). During the 12-week medication phase, subjects attended study visits weekly for weeks 1 through 8 and at weeks 10 and 12 to assess vital signs, tobacco use status, medication compliance, adverse events, concomitant medication use, and to receive a behavioral intervention based upon the ST intervention manual. The intervention manual included topics such as the health effects of ST, preparing for quit day, dealing with withdrawal, avoiding relapse, stress and time management, weight management, and wellness and exercise. Subjects received a new supply of medication at each study visit.

Subjects completing the 12-week medication phase continued in non drug follow-up for weeks 13 to 52. Clinic visits occurred at weeks 13, 24, and 52. Telephone follow-up contacts occurred at weeks 16 and 20. Adverse events and concomitant medications were assessed and a behavioral intervention was provided at these times.

2.4. Screening

Screening included a medical history and physical examination by a physician with measurement of vital signs (blood pressure, heart rate, weight, and height). An oral examination was conducted by a periodontist and abnormal oral findings were recorded and discussed with the subjects. Photographs were taken and retained in the subject's study record to compare with oral exam findings at study completion. A tobacco use history was obtained and tobacco dependence measures including the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire-Smokeless Tobacco (Boyle et al., 1995). Alcohol abuse was assessed with the SAAST and DAST-20. Laboratory tests included serum and urine tobacco alkaloid measurements (Moyer et al., 2002).

2.5. Post-randomization

Tobacco abstinence was determined at each weekly visit starting with week two after randomization by subject self-report and biochemically-confirmed using urine cotinine (Benowitz et al., 2002). A physical examination was performed at the end of the medication phase (week 12) or at any visit at which subjects indicated they wanted to discontinue study participation. In order to determine the adequacy of blinding procedures, subjects were asked to state if they thought they were on active medication or placebo.

2.6. Study End Points

The primary endpoint was the biochemically-confirmed point-prevalence tobacco abstinence rate at end-of-treatment (12 weeks), defined as the self-reported tobacco abstinence in that last 7 days confirmed by a urine cotinine of < 50 ng/mL. Prolonged abstinence was also assessed and defined as no tobacco use following a two-week grace period after the TQD. Continuous abstinence was defined as no tobacco use following the TQD. Point-prevalence, prolonged, and continuous abstinence rates were also analyzed at weeks 24 and 52.

Additional endpoints included nicotine withdrawal, craving, and changes in mean body weight. Nicotine withdrawal and craving were determined from the daily diaries and body weight changes were determined for all subjects meeting criteria for prolonged tobacco abstinence at week 12.

2.7. Measures of Withdrawal and Craving

Subjects were asked to keep a daily diary to record symptoms of nicotine withdrawal. Daily diaries were distributed weekly starting at the baseline visit and returned at each weekly study visit through week 12. The daily diary included the Minnesota Nicotine Withdrawal Scale [MNWS] (Hughes, 1998; Hughes and Hatsukami, 1986). The MNWS assesses depression, insomnia, irritability/frustration/anger, anxiety, difficulty concentrating, restlessness, and increased appetite. Tobacco craving was also collected and modified for ST users by replacing “desire to smoke” with “desire to use tobacco.” Symptoms were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not present) to 4 (severe).

2.8. Adverse Events

All observed and self-reported adverse events were documented on case report forms and followed up until resolution or end of study.

2.9. Statistical Analyses

The sample-size for the current study was determined for the primary endpoint of 7-day point-prevalence tobacco abstinence for week 12 (end-of-treatment). From a pilot study, we observed a tobacco abstinence rate of 44% at the end of 12 weeks of medication for ST users receiving bupropion SR compared to 26% for subjects receiving placebo (Dale et al., 2002). Based on these preliminary data, we hypothesized that the 7-day point-prevalence tobacco abstinence rate at the end of the medication phase would be 26% for the placebo group. Using this assumption, we determined that a sample size of 220 subjects (110 placebo, 110 bupropion SR) would provide statistical power of 80% to detect an end-of-treatment abstinence rate of 44% or greater for the bupropion SR group (using a two-sided, α = 0.05 level test).

For tobacco abstinence endpoints, subjects who missed a visit or failed biochemical confirmation of tobacco abstinence were considered to be using tobacco for that visit. Tobacco abstinence endpoints were analyzed using logistic regression. The dependent variable for the primary analysis was the biochemically confirmed 7-day point prevalence tobacco abstinence at end-of-treatment (week 12), and the independent variables were treatment (bupropion SR vs placebo), study site (Minnesota vs West Virginia), and history of MDD (MDD vs no MDD). An initial analysis was performed which included the appropriate interaction terms to verify the assumption that the effect of bupropion SR was not dependent on study site and to test whether the effect of bupropion SR was dependent on a history of MDD. After confirming that there were no significant treatment-by-strata interaction effects, all subsequent analyses were performed with main effect terms for study site and history of MDD included as covariates. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for bupropion SR vs placebo were calculated using the parameter estimates from this logistic regression model. Prolonged and continuous tobacco abstinence endpoints were also analyzed using similar logistic regression models. In addition, a repeated measures analysis was performed which included point prevalence tobacco abstinence outcomes for all post-TQD visits during the medication phase. Repeated abstinence outcomes were analyzed using Generalized Estimating Equations (GEEs) with a logit link function and robust variance estimates based on a first order autoregressive structure used to account for the correlation of repeated outcome assessments within individuals (Liang and Zeger, 1986).

Withdrawal symptoms and craving were assessed daily using the MNWS modified for ST users. Each symptom was scored by the subject as none (0), slight (1), mild (2) moderate (3), and severe (4). For analysis purposes, a composite withdrawal score was computed as the mean of the 7 individual withdrawal symptoms assessed. Craving (“desire to use tobacco”) was analyzed separately. The repeated measures of withdrawal and craving for the first 2 weeks following TQD were analyzed using GEEs. For these models, the explanatory variables were treatment group (bupropion SR vs placebo) and time. The time-by-treatment interaction effect was included to assess whether changes in withdrawal or craving over time differed between treatment groups. To supplement the repeated measures analyses, daily scores were compared between groups using the two-sample t-test.

Weight change from baseline to the end of the medication phase for subjects who met criteria for prolonged abstinence was compared between treatment groups using the rank sum test. Similar analyses were performed for weight change from baseline to one-year following TQD. Adverse events were summarized and compared between groups using Fisher's exact test. In all cases, two-sided tests were performed with p-values ≤ 0.05 used to denote statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Subjects

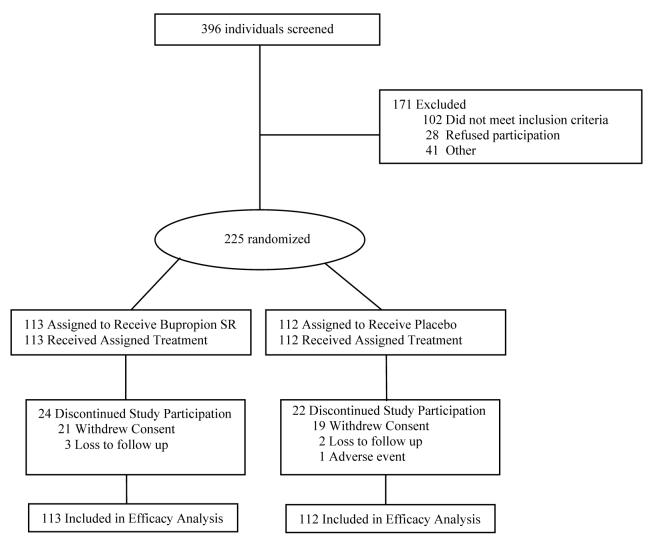

Of 396 individuals screened, 225 were eligible and randomized to receive treatment (113 bupropion SR, 112 placebo) and included in the final analysis (Figure 1). A total of 46 subjects (24 bupropion SR, 22 placebo; p = 0.766) discontinued study participation prior to the end of the medication phase.

Fig. 1.

Study flow diagram.

Baseline characteristics of enrolled subjects were comparable across the treatment groups (Table 1). All subjects were male. The mean age was 38.1 years (range 19 to 72 years), and the mean duration of regular ST use was 19.0 years (range 2 to 60 years). In addition to ST use, 91 subjects (40%) reported “ever” cigarette smoking (> 100 cigarettes in lifetime) with a median duration of cigarette abstinence of 8 years, and 3 subjects reported current cigarette smoking at baseline (2 bupropion SR, 1 placebo).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Subjects in a Randomized Clinical Trial of Bupropion SR for Smokeless Tobacco Use.

| Characteristic | Bupropion SR (N=113) |

Placebo (N=112) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 37.9±9.7 | 38.4±10.0 |

| Caucasian, n (%) | 111 (98) | 110 (98) |

| History of Major Depressive Disorder | 11 (10) | 11 (10) |

| Marital Status, n (%) | ||

| Never | 21 (19) | 15 (13) |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 13 (11) | 9 (8) |

| Married | 78 (69) | 86 (77) |

| Other | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Highest level of education, n (%) | ||

| < High school graduate | 2 (2) | 2 (2) |

| High school graduate | 30 (27) | 28 (25) |

| Some college | 50 (44) | 52 (46) |

| College graduate | 31 (27) | 30 (27) |

| Current type of tobacco use, n (%) | ||

| Snuff only | 101 (89) | 104 (93) |

| Chewing tobacco only | 11 (10) | 5 (4) |

| Both snuff and chewing tobacco | 1 (1) | 3 (3) |

| Average time plug/dip in mouth, minutes* | 104±141 | 70±55 |

| Tobacco use in past 6 months, cans/pouches per week | 4.1±2.8 | 4.0±3.3 |

| Years of regular smokeless tobacco use, years | 18.7±9.9 | 19.4±7.5 |

| Other tobacco users in household, n (%) | 95 (84) | 90 (80) |

| Number of serious stop attempts, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 24 (21) | 24 (21) |

| 1-2 | 47 (42) | 41 (37) |

| 3-4 | 26 (23) | 24 (21) |

| 5+ | 16 (14) | 23 (21) |

| Longest time off tobacco, n (%) | ||

| < 24 hours | 12 (11) | 24 (21) |

| 1-7 days | 27 (24) | 15 (13) |

| 2-8 weeks | 31 (27) | 28 (25) |

| 9 weeks – 6 months | 23 (20) | 27 (24) |

| > 6 months | 20 (18) | 18 (16) |

| Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire - ST† | 13.9±2.5 | 13.7±2.6 |

| Oral exam findingss† | ||

| Any abnormal finding, n (%) | 109 (96) | 108 (97) |

| Any evidence of leukoplakia, n (%) | 101 (89) | 100 (90) |

The distribution is skewed due to some subjects that reported leaving dip/chew in mouth all day. The median (interquartile range) response was 60 (35, 120) minutes for bupropion SR and 60 (30, 90) minutes for placebo.

Data were missing for 1 subject in the placebo group.

3.2. Abstinence rates

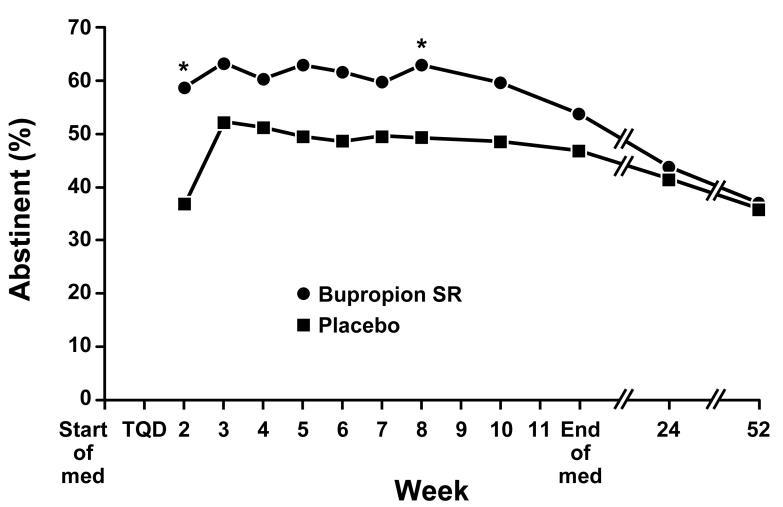

The 7-day point-prevalence tobacco abstinence rates did not differ significantly between bupropion SR and placebo at the end of the medication phase (53.1% vs 46.4%; OR 1.3; p = 0.301) from logistic regression adjusting for study site and history of MDD (Table 2). Similar findings were observed for the week-12 assessment of prolonged and continuous abstinence. When point prevalence tobacco abstinence outcomes from all post-TQD visits during the medication phase were considered using a GEE analysis, we observed a significant treatment effect (p = 0.020) indicating an overall greater likelihood of tobacco abstinence at each study visit in subjects receiving bupropion SR (OR = 1.7; 95% CI, 1.1-2.7) (Figure 2). The 7-day point prevalence, prolonged and continuous tobacco abstinence rates were nearly identical at week 24 in the bupropion SR and placebo groups. Outcomes were also similar for bupropion SR and placebo groups at week 52.

Table 2.

Tobacco Abstinence Outcomes in a Randomized Clinical Trial of Bupropion SR for Smokeless Tobacco Use*

| Bupropion SR (N=113) |

Placebo (N=112) |

Logistic Regression results† |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abstinence Definition* | No. | (%) | No. | (%) | OR | 95% C.I. | p-value |

| Week 12 (end of medication) | |||||||

| 7-day point prevalence | 60 | (53.1) | 52 | (46.4) | 1.3 | 0.8 to 2.2 | 0.301 |

| Prolonged | 49 | (43.4) | 42 | (37.5) | 1.3 | 0.8 to 2.2 | 0.354 |

| Continuous | 37 | (32.7) | 32 | (28.6) | 1.2 | 0.7 to 2.2 | 0.488 |

| Week 24 | |||||||

| 7-day point prevalence | 49 | (43.4) | 46 | (41.1) | 1.1 | 0.6 to 1.9 | 0.706 |

| Prolonged | 36 | (31.9) | 35 | (31.3) | 1.0 | 0.6 to 1.8 | 0.913 |

| Continuous | 25 | (22.1) | 27 | (24.1) | 0.9 | 0.5 to 1.7 | 0.718 |

| Week 52 | |||||||

| 7-day point prevalence | 40 | (35.4) | 41 | (36.6) | 1.0 | 0.5 to 1.7 | 0.861 |

| Prolonged | 31 | (27.4) | 30 | (26.8) | 1.0 | 0.6 to 1.9 | 0.902 |

| Continuous | 21 | (18.6) | 24 | (21.4) | 0.9 | 0.4 to 1.6 | 0.594 |

7-day point prevalence abstinence confirmed by urinary cotinine < 50 ng/mL. Prolonged tobacco abstinence is defined as no tobacco use following a two-week grace period after target quit date (TQD). Continuous abstinence is defined as no tobacco use following TQD. In all cases, subjects that missed a visit were assumed to be using tobacco.

In addition to treatment (bupropion SR vs placebo) the logistic regression analysis included covariates for study site and a history of major depressive disorder. Odds ratios > 1.0 indicate an increased likelihood of abstinence for bupropion SR compared to placebo.

Fig. 2.

Point-prevalence tobacco abstinence rates according to treatment group. At each visit, subjects were classified as abstinent if they self-reported abstinence from all tobacco for the previous 7 days confirmed by urine cotinine < 50 ng/mL. An asterisk (*) indicates a significant (p ≤ 0.05) difference between treatment groups.

All tobacco abstinence outcomes were analyzed with models that adjusted for study site (MN vs WV) and history of MDD. Initial analyses confirmed that there were no significant treatment-by-covariate interactions. In addition, the effect of study site was not statistically significant in any analysis. At the end of the medication phase, point prevalence tobacco abstinence was not found to differ significantly between those with a history of MDD (8/22 overall; 4/11 bupropion SR; 4/11 placebo) compared to those without a history of MDD (104/203 overall; 56/102 bupropion SR. 48/101 placebo; OR 0.5; 95% CI, 0.2-1.3; p = 0.158 from logistic regression assessing the likelihood of abstinence for those with versus without MDD after adjusting for treatment and study site). At week 52, subjects with a history of MDD were less likely to be abstinent from tobacco use (3/22 overall; 1/11 bupropion SR, 2/11 placebo) compared to subjects without a history of MDD (78/203 overall; 39/102 bupropion SR, 39/101 placebo; OR 0.24; 95% CI, 0.07-0.85; p = 0.027).

3.3. Withdrawal and Craving

We observed that while the composite withdrawal score was found to decline significantly with time (parameter estimate = −0.032; SE = .004; p < 0.001), no significant difference was detected between treatment groups (parameter estimate= −0.095; SE = .094; p = 0.309). In analyses performed separately at each time period, no differences were found between treatment groups at any time point (p ≥ . 13 at each time point). From GEE analysis no time-by-treatment interaction effect was observed (parameter estimate = −0.008; SE = 0.007; p = 0.242).

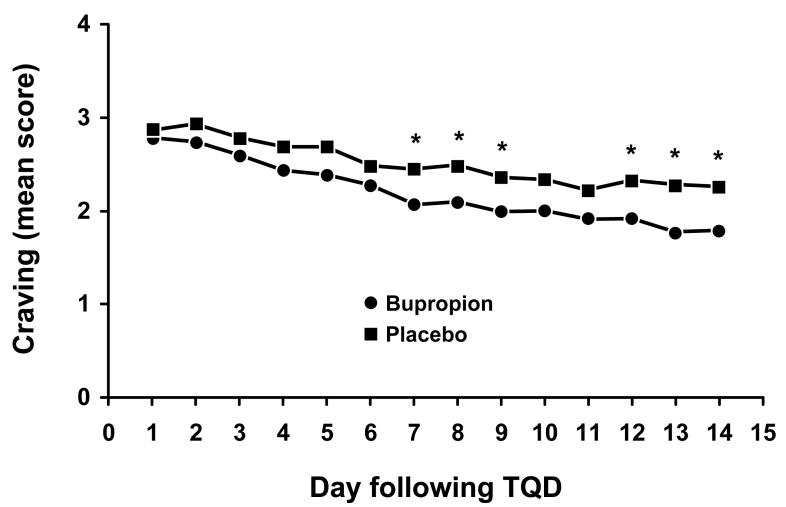

The mean score for the craving (“desire to use tobacco”) daily diary item over the first 14 days following TQD is presented in Figure 3. From GEE analysis, we observed a significant time-by-treatment interaction effect (parameter estimate = −0.028; SE = 0.012; p = 0.024) indicating that the changes in craving over time differed between treatment groups with subjects who received bupropion SR having decreased craving compared to subjects receiving placebo. From analyses performed separately at each time period, the first significant difference between groups was observed on day 7 following TQD (Figure 3).

Fig. 3.

Mean score for the daily diary item craving (“desire to use tobacco”) for the first 14 days following target quit date (TQD) according to treatment group. An asterisk (*) indicates a significant (p ≤ 0.05) difference between treatment groups. The number of subjects with data available ranges from 96 to 104 for bupropion SR and 94 to 107 for placebo.

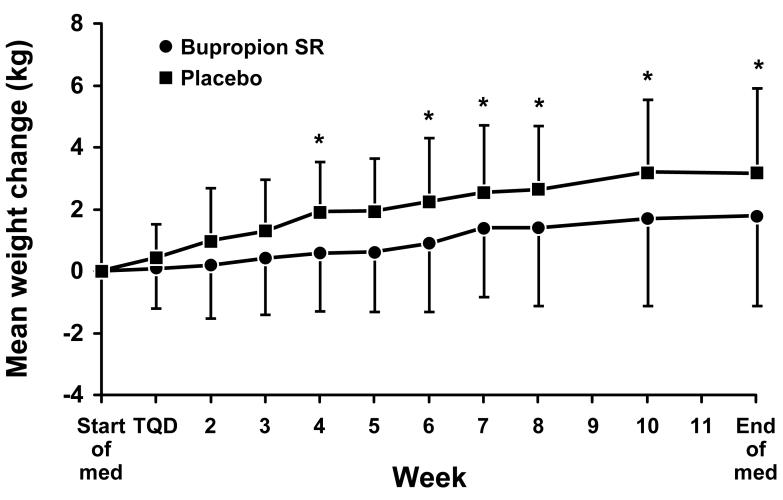

3.4. Weight Change

The mean change in weight from the start of medication (baseline) for the 49 bupropion SR and 42 placebo subjects who met criteria for prolonged abstinence at the end of the medication phase is shown in Figure 4. At the end of medication, the mean ± SD weight change from baseline was an increase of 1.7 ± 2.9 kg for the bupropion SR group compared to an increase of 3.2 ± 2.7 kg for the placebo group (p = 0.005). Of the 31 bupropion SR and 30 placebo subjects who met criteria for prolonged abstinence at week 52, the mean ± SD weight change from baseline was 4.6 ± 4.1 kg in the bupropion SR group compared to 4.1 ± 4.3 kg in the placebo group (p = 0.387).

Fig. 4.

Mean (± SD) weight change (kg) from baseline for subjects that met criteria for prolonged abstinence at the end of the medication phase (49 bupropion SR, 42 placebo). An asterisk (*) indicates a significant (p ≤ 0.05) difference between treatment groups.

3.5. Adverse Events

During the 12-week medication phase, the following adverse events were reported by ≥ 10% of the subjects in either treatment group: respiratory tract infection (35% vs 35% for bupropion SR vs placebo; p = 0.961), sleep disturbance (31% vs 13%; p = 0.002), headache (15% vs 17%; p = 0.694), irritability (15% vs 8%; p = 0.100), dry mouth (12% vs 7%; p = 0.166). The frequency of adverse events occurring in < 10% of study subjects did not differ significantly between treatment groups with the exception of sore throat (2% vs 9%; p = 0.017) and diarrhea (1% vs 8%; p = 0.009) which were reported more frequently in the placebo group. Nine serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported but none were adjudicated to be related to study drug. SAE's included pneumonia, left knee injury, acute appendicitis, hernia, kidney stones, myocardial infarction, aortic stenosis, dehydration due to diverticulitis, and elevated liver enzymes (post-medication period).

3.6. Medication Adherence & Blinding

Medication adherence was similar between groups with a median adherence of 84% [interquartile range (IQR) 38%, 95%] for bupropion SR and 90% (IQR 66%, 95%) for placebo (p = 0.169). During the end of study interview subjects were asked which medication assignment they thought they had received. Of 99 bupropion SR subjects, 42% thought they received bupropion SR, 30% thought they received placebo, and 27% indicated that they did not know. Responses did not differ significantly (p = 0.058) from the 95 placebo subjects among whom 29% thought they received bupropion SR, 46% thought they received placebo, and 24% indicated that they did not know.

4. Discussion

Ours is the first multicenter, randomized controlled clinical trial to report the efficacy of bupropion SR for treating ST users. We observed that bupropion SR did not significantly increase short-term or long-term tobacco abstinence rates among ST users. Several plausible explanations exist for the lack of treatment efficacy of bupropion SR for ST users in the face of extant literature suggesting that bupropion SR is clearly efficacious for cigarette smokers (Hughes et al., 2002) and may be efficacious for ST users (Ebbert et al., 2003). One explanation is that bupropion SR is simply not effective for this group because ST use behavior is fundamentally different from cigarette smoking behavior. Indeed, previous literature has suggested that interventions which have consistently been shown to increase long-term (≥ 6 month) smoking abstinence rates, such as the nicotine gum and patch, have not been shown to increase long-term tobacco abstinence in ST users (Ebbert et al., 2004).

Another possible explanation is that our study may have been underpowered to detect a difference, as may be suggested by the higher, but not statistically different, point prevalence estimate in the bupropion SR group compared to the placebo at 12 weeks (53.1% vs 46.4%). The tobacco abstinence rate in the placebo group at 12 weeks is impressive and almost twice what was observed in two previous pilot studies of bupropion SR for ST users (Dale et al., 2002; Glover et al., 2002). The placebo tobacco abstinence rate is also substantially higher than has been observed in previous bupropion SR studies with cigarette smokers receiving placebo (19% at 7 weeks) (Hurt et al., 1997) and may relate to the behavioral intervention delivered to both groups in the current study. We provided both groups with an oral examination and feedback about the oral examination findings as well as sixteen individual counseling sessions using an intervention manual tailored for ST users. Indeed, previous research has demonstrated that behavioral interventions are effective for ST users (Severson, 2003) especially those which include an oral examination component (Ebbert et al., 2004). The high tobacco abstinence rate in the placebo group at 12 weeks (46.4%) is consistent with other pharmacologic studies with ST users which have also included intensive behavioral counseling in the intervention and control groups (Hatsukami et al., 1996; Hatsukami et al., 2000). The high tobacco abstinence rates in the placebo group may also relate to the fact that very few treatments are available for ST users and the motivated ST users in the current study may have been generally more responsive to intervention. The hypothesis that we were underpowered is also supported by the finding of a treatment effect from the repeated measures analysis which takes into effect all data collected during the treatment phase.

Our finding of decreased craving over time with bupropion SR compared to placebo is consistent with one previous investigation in cigarette smokers assessing the impact of bupropion SR on craving and withdrawal among cigarette smokers during forced, short-term abstinence (Teneggi et al., 2005). In this study, bupropion SR was observed to significantly reduce craving but had no significant impact on overall withdrawal intensity. Our results are consistent with the hypothesis that smoking craving and withdrawal are distinct entities which are controlled by separate and distinct central nervous system pathways. Indeed, available experimental evidence has suggested that craving is associated with dopaminergic pathways while withdrawal is attributed to nondopaminergic pathways (Teneggi et al., 2002). Our study suggests that while bupropion SR may decrease tobacco craving among ST users, this effect is independent of any effects on tobacco abstinence rates.

We observed that bupropion SR attenuated weight gain through the end of treatment, although this effect was not maintained to 52 weeks. This observation is consistent with previous investigations which have observed similar attenuations in weight gain among cigarette smokers during the treatment phase which was also not maintained after the medication was discontinued (Hurt et al., 1997; Jorenby et al., 1999). In the current study, ST users receiving bupropion SR who were continuously abstinent from tobacco use gained an average of only 1.7 kg while those receiving placebo gained 3.2 kg. In cigarette smokers, subjects receiving bupropion SR 150 mg twice per day who were continuously abstinent from tobacco gained an average of 1.5 kg while subjects receiving placebo gained 2.9 kg through end-of-treatment at 7 weeks. The attenuation of weight gain with bupropion SR is also consistent with short-term abstinence studies among cigarette smokers which have demonstrated that bupropion SR reduces appetite (Teneggi et al., 2005). In previous studies, we have observed that weight gain is a significant concern among recently abstinent ST users (Ebbert et al., 2005). Our findings suggest that bupropion SR may have clinical utility among ST users attempting to achieve tobacco abstinence who are concerned about weight gain.

Interestingly, we observed that ST users with a history of MDD were less likely to report tobacco abstinence at 52 weeks. Previous studies in cigarette smokers have suggested that a lifetime history of major depression in not an independent risk factor for failure to achieve tobacco abstinence with smoking cessation treatment (Hayford et al., 1999). However, effects of depression on smoking cessation outcomes vary across studies and may differ by gender and type of treatment (i.e., behavioral or pharmacologic). Little information is available regarding depression and treatment outcomes in ST users. The impact of mood disorders on ST abstinence deserves exploration in future studies.

In summary, the major strengths of this study relate to the randomized design and the adequacy of the blinding procedures. The negative results for tobacco abstinence may have been due, in part, to the higher than anticipated tobacco abstinence rates among subjects in the control group. Bupropion SR may be effective for decreasing craving and attenuating weight gain among ST users attempting to achieve tobacco abstinence.

Acknowledgement

This project and manuscript was supported by the National Cancer Institute grant R01 90884. We would like to thank the excellent support we received from the research staff in the Nicotine Dependence Center and Stephanie Bagniewski for data analysis support. We would like to thank Penny N. Glover, MEd, Connie L. Cerullo, MS, and Carl R. Sullivan, MD, from the West Virginia University School of Medicine. The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Benowitz NL, Ahijevych K, Hall S, Hansson A, Henningfield J, Hurt RD, Jacob PI, Jarvis MJ, LeHouezec J, Lichtenstein E, Tsoh J, Velicer W. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4:149–159. doi: 10.1080/14622200210123581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle RG, Jensen J, Hatsukami DK, Severson HH. Measuring dependence in smokeless tobacco users. Addict Behav. 1995;20:443–450. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale LC, Ebbert JO, Schroeder DR, Croghan IT, Rasmussen DF, Trautman JA, Cox LS, Hurt RD. Bupropion for the treatment of nicotine dependence in spit tobacco users: a pilot study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4:267–274. doi: 10.1080/14622200210153821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebbert JO, Dale LC, Patten CA, Croghan IT, Schroeder DR, Moyer TP, Hurt RD. Effect of high dose nicotine patch therapy on tobacco withdrawal symptoms among smokeless tobacco users. Nicotine Tob Res. doi: 10.1080/14622200601078285. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebbert JO, Klinkhammer MD, Stevens SR, Rowland LC, Offord KP, Ames SC, Dale LC. A survey of characteristics of smokeless tobacco users in a treatment program. Am J Health Behav. 2005;29:25–35. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.29.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebbert JO, Rowland LC, Montori V, Vickers KS, Erwin PC, Dale LC, Stead LF. Interventions for smokeless tobacco use cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004306.pub2. CD004306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebbert JO, Rowland LC, Montori VM, Vickers KS, Erwin PJ, Dale LC. Treatments for spit tobacco use: a quantitative systematic review. Addiction. 2003;98:569–583. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernster VL, Grady DG, Greene JC, Walsh M, Robertson P, Daniels TE, Benowitz N, Siegel D, Gerbert B, Hauck WW. Smokeless tobacco use and health effects among baseball players. JAMA. 1990;264:218–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover E, Glover P, Sullivan C, Cerullo C, Hobbs G. A comparison of sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smokeless tobacco cessation. Am J Health Behav. 2002;26:386–393. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.26.5.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman MT, Morgenstern H, Wynder EL. A case-control study of factors affecting the development of renal cell cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;124:926–941. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatsukami D, Jensen J, Allen S, Grillo M, Bliss R. Effects of behavioral and pharmacological treatment on smokeless tobacco users. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:153–161. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatsukami DK, Grillo M, Boyle R, Allen S, Jensen J, Bliss R, Brown S. Treatment of spit tobacco users with transdermal nicotine system and mint snuff. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:241–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayford KE, Patten CA, Rummans TA, Schroeder DR, Offord KP, Croghan IT, Glover ED, Sachs DP, Hurt RD. Efficacy of bupropion for smoking cessation in smokers with a former history of major depression or alcoholism. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:173–178. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henley SJ, Thun MJ, Connell C, Calle EE. Two large prospective studies of mortality among men who use snuff or chewing tobacco (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2005;16:347–358. doi: 10.1007/s10552-004-5519-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR. Errors in using tobacco withdrawal scale [letter to editor] Tob Control. 1998;7:92–93. doi: 10.1136/tc.7.1.92a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Hatsukami D. Signs and symptoms of tobacco withdrawal. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:289–294. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800030107013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Stead LF, Lancaster T. Antidepressants for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000031. CD000031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt R, Sachs D, Glover E, Offord K, Johnston J, Dale L, Khayrallah M, Schroeder D, Glover P, Sullivan C, Croghan I, Sullivan P. A comparison of sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1195–1202. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710233371703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorenby DE, Leischow SJ, Nides M, Rennard SI, Johnston JA, Hughes AR, Smith SS, Muramoto ML, Daughton DM, Doan K, Fiore MC, Baker TB. A controlled trial of sustained-release bupropion, a nicotine patch, or both for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:685–691. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903043400903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang K, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Little SJ, Stevens VJ, LaChance PA, Severson HH, Bartley MH, Lichtenstein E, Leben JR. Smokeless tobacco habits and oral mucosal lesions in dental patients. J Public Health Dent. 1992;52:269–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1992.tb02288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GC, Brown JP, Eifler CW, Houston GD. Oral leukoplakia status six weeks after cessation of smokeless tobacco use. J Am Dent Assoc. 1999;130:945–954. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1999.0335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson ME, Winn DM. Smokeless tobacco: association with increased cancer risk. NCI Monographs. 1989:13–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeill A. Harm reduction. Br Med J. 2004;328:885–887. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7444.885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer TP, Charlson JR, Enger RJ, Dale LC, Ebbert JO, Schroeder DR, Hurt RD. Simultaneous analysis of nicotine, nicotine metabolites, and tobacco alkaloids in serum or urine by tandem mass spectrometry, with clinically relevant metabolic profiles. Clin Chem. 2002;48:1460–1471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muscat JE, Hoffmann D, Wynder EL. The epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma. A second look. Cancer. 1995;75:2552–2557. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950515)75:10<2552::aid-cncr2820751023>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muscat JE, Stellman SD, Hoffmann D, Wynder EL. Smoking and pancreatic cancer in men and women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997;6:15–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Health National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science conference statement: tobacco use: prevention, cessation, and control. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:839–844. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-11-200612050-00141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff KS. National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38:381–389. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290015001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severson H. Enough snuff: ST Cessation from the behavioral, clinical, and public health perspectives. 1992. (NIH Publication No. 93-3461). [Google Scholar]

- Severson HH. What have we learned from 20 years of research on smokeless tobacco cessation? Am J Med Sci. 2003;326:206–211. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200310000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA. Assessment of substance abuse: Drug abuse screening test (DAST) In: Carson-DeWitt R, editor. Encyclopedia of drugs, alcohol, & addictive behaviors. Macmillan Reference; Durham, NC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Stockwell HG, Lyman GH. Impact of smoking and smokeless tobacco on the risk of cancer of the head and neck. Head Neck Surg. 1986;9:104–110. doi: 10.1002/hed.2890090206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Results from the 2005 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. 2006 http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/NSDUH/2k5NSDUH/tabs/TOC.htm. Accessed: December 1 2006.

- Swenson WM, Morse RM. The use of a self-administered alcoholism screening test (SAAST) in a medical center. Mayo Clin Proc. 1975;50:204–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teneggi V, Tiffany ST, Squassante L, Milleri S, Ziviani L, Bye A. Smokers deprived of cigarettes for 72 h: effect of nicotine patches on craving and withdrawal. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;164:177–187. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1176-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teneggi V, Tiffany ST, Squassante L, Milleri S, Ziviani L, Bye A. Effect of sustained-release (SR) bupropion on craving and withdrawal in smokers deprived of cigarettes for 72 h. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;183:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0145-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo KK, Ounpuu S, Hawken S, Pandey MR, Valentin V, Hunt D, Diaz R, Rashed W, Freeman R, Jiang L, Zhang X, Yusuf S. Tobacco use and risk of myocardial infarction in 52 countries in the INTERHEART study: a case-control study. Lancet. 2006;368:647–658. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69249-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomar SL, Winn DM, Swango PA, Giovino GA, Kleinman DV. Oral mucosal smokeless tobacco lesions among adolescents in the United States. J Dent Res. 1997;76:1277–1286. doi: 10.1177/00220345970760060701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]