Abstract

Background

This study was initiated after observation of some intriguing epithelial growth properties of contact lenses used as a bandage for patients after pterygium surgery.

Aim

To determine the efficacy of culturing human ocular surface epithelial cells on therapeutic contact lenses in autologous serum with a view of using this system to transfer epithelial cells to patients with persistent corneal or limbal defects.

Methods

Excess graft tissue resected from patients undergoing pterygium surgery (n = 3) consisting of limbal epithelium was placed on siloxane–hydrogel contact lenses (lotrafilcon A and balafilcon A). Limbal explants were cultured in media with 10% autologous serum. Morphology, proliferative capacity and cytokeratin profile were determined by phase contrast, light and electron microscopy, and immunohistochemical analysis.

Results

Lotrafilcon A contact lenses sustained proliferation and migration from limbal tissue. Cells became confluent after 10–14 days and consisted of 2–3 layers with a corneal phenotype (CK3+/CK12+/CK19−) and a propensity to proliferate (p63+). Electron microscopy showed microvilli on the apical surface with adhesive projections, indicating that these cells were stable and likely to survive for a long term. Growth was not observed from limbal explants cultured on balafilcon A contact lenses.

Conclusion

A method for culturing human ocular surface epithelium on contact lenses that may facilitate expansion and transfer of autologous limbal epithelial cells while avoiding the risks associated with transplanting allogeneic tissue has been developed. This technique may be potentially useful for the treatment of patients with limbal stem cell deficiency.

The ocular surface is covered by phenotypically and functionally distinct stratified squamous epithelium that resides in the conjunctiva, limbus and cornea. The limbal epithelium is the transition zone between the conjunctiva and the cornea, and is the proposed stem cell niche.1,2 Limbal stem cells (LSCs) are responsible for maintaining corneal integrity by their ability to replace damaged epithelium. LSC deficiency (LSCD) is characterised by persistent corneal defects (ulceration, inflammation, neovascularisation and conjunctivalisation), caused by either LSC depletion or changes to their niche.3,4,5

Ocular surface reconstruction is a method of minimising the complications of LSCD. Techniques include amniotic membrane transplantation6,7 and grafting autologous or allogeneic LSC sheets on to the corneal surface, or propagation on amniotic membrane before transplantation.8,9,10 Stem cells have been expanded in vitro, carried to the ocular surface and an amniotic membrane applied,11 which is an advantageous system because the amniotic membrane acts as a bandage that promotes epithelialisation, and suppresses inflammation, fibrosis and angiogenesis.12,13 Autologous or allogeneic lamellar keratolimbal grafts are also used for LSCD14; however, this also introduces foreign biological matter, whereby immunosuppression is required for graft rejection.

Epithelial culture conditions have been optimised for the restoration of the ocular surface in patients with LSCD. Serum‐containing and serum‐free ocular surface epithelial cultures have been developed, but these systems too are compromised with xenobiotics.15,16,17,18,19 An alternative approach used autologous oral mucosal epithelial sheets to replenish the rabbit ocular surface, but again, amniotic membrane and mouse 3T3 cells were required and neovascularisation was a common complication.20 Autologous oral mucosal epithelial sheets fabricated on temperature‐sensitive surfaces have successfully been used to resolve surgically wounded rabbit corneas,21 but the consequences of this transplantation technique in patients with LSCD is currently unknown. Nakamura et al22 cultivated human oral mucosal epithelial cells from patients with severe ocular surface disease (OSD) with autologous serum, but again amniotic membrane was used as a biological support.

The present investigation was initiated after observation of the adhesion and expansion of epithelial cells on to the therapeutic contact lenses after pterygium surgery. Subsequently, we used the contact lens surface as a scaffold to develop an autologous limbal epithelial culture model. There is an urgent need to improve current methods used to treat patients with LSCD, as most rely on animal products or allogenic tissue. Our future goals are to validate this system in an animal model of LSCD and to determine whether the surface epithelium in patients with OSD can be effectively re‐populated.

Materials and methods

Conjunctival autograft and contact lens wear

Primary pterygia were excised as described previously.23 The conjunctival graft consisting of superior bulbar conjunctiva and superior limbus was excised, transferred to the region of pterygium excision and sutured into place. As the graft bed is often irregularly shaped, graft tissue was trimmed, which provided a source of tissue. A siloxane–hydrogel (Si–Hi) contact lens (Focus Night & Day (lotrafilcon A, CIBA Vision, Duluth, GA, USA) or Purevision (balafilcon A, Bausch and Lomb)) was placed over the eye at the end of the procedure and removed at the 1‐week visit. The use of a contact lens as a therapeutic bandage after surgery considerably reduced the pain associated with this procedure.24

Histological and immunohistochemical assessment of contact lenses

Contact lenses (n = 11) were harvested after 1 week of continuous wear, formalin‐fixed and either processed for paraffin sectioning (n = 4), or flat mounted (n = 7) for histological and immunohistochemical examination. Eight of the 11 contact lenses were lotrafilcon A, whereas three were balafilcon A. Partial radial incisions were made through some contact lenses, and this allowed the whole lens to be flat mounted. Flat‐mounted contact lenses were stained with periodic acid‐Schiff or haematoxylin, or incubated with antibody (table 1). For paraffin sectioning, contact lenses were trimmed, embedded in agarose and then processed as tissue blocks. Blocks were sectioned (4 μm) and analysed by immunohistochemistry as described previously.25,26,27 Some contact lenses were cut into quadrants and free‐floated to determine the expression of multiple antigens from the same specimen.

Table 1 Primary antibodies used for immunohistochemistry.

| Antibody | Source | Catalogue no | Clone | DF | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keratin 3/12 | USB | C9097‐34M | 2Q1040 | 1:50 | Corneal‐type epithelium* |

| 65K keratin† | ICN | 69–143 | AE5 | 1:50 | Corneal‐type epithelium* |

| Keratin 15 | Biocare | CM068B | LHK15 | 1:50 | Basal stratified epithelium‡ |

| Keratin 19 | USB | C9097‐24B | 4A36 | 1:100 | Basal limbal epithelium‡, §, glandular‐type epithelium |

| Pan keratin | Dako | M0821 | MNF116 | 1:50 | Keratins 5, 6, 8, 17, 19 |

| p63 | Santa Cruz | sc‐8431 | 4A4 | 1:50 | Proliferative capacity |

| IgG2a | Dako | X0943 | – | 1:50 | Non‐specific |

| IgG1 | Dako | LS191 | – | 1:50 | Non‐specific |

DF, dilution factor.

USB, United States Biological, Swampscott, Massachusetts, USA; CN Biomedicals, Aurora, Ohio, USA; Biocare Medical, Concord, California, USA; Dako Corporation, Carpinteria, California, USA; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, California, USA.

*Both antibodies are considered markers of corneal differentiation.

†This antibody was originally purchased from ICN,28 now known as MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH.

‡Antibodies used to identify epithelial cells of progenitor cell phenotype.

§Antibodies used to identify epithelial cells of conjunctival type.

Electron microscopy

For scanning electron microscopy (SEM), contact lens quadrants were fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde and 2.5% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2), dehydrated and dried via liquid CO2 in an Emitech K850 critical point dryer. Specimens were mounted, gold coated and examined in a FEI Quanta 200 SEM operated at 10 kV. For transmission electron microscopy (TEM), specimens were fixed (as for SEM) then post‐fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2). Dehydration was followed by infiltration with 1:1 LR white resin and 100% ethanol (1 h). Sections (60 nm) were cut and stained with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate (20 min), followed by Reynold's lead citrate (4 min), then examined in a Hitachi H‐7000 TEM (Hitachi High Technologies Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Limbal epithelial cell culture

Protocols relating the use of human cells were approved by the University of New South Wales Human Ethics Committee and carried out in accordance with the tenets of the World Medical Associations Declaration of Helsinki. Limbal epithelial cells (LECs) from at least two donors were cultured and expanded from remnant limbal graft tissue from patients who had undergone pterygium resection. LEC cultures were established as described previously.27,28,29 LEC (2×104, passage 5–10) were seeded on contact lenses (n = 6; 3× each of lotrafilcon A and balafilcon A). Contact lenses were harvested after 2 weeks, formalin‐fixed, cut into six equal quadrants, stained as free‐floating segments with selective markers (table 1) and flat mounted. Other contact lenses (n = 8; 4× each of lotrafilcon A and balafilcon A) were incubated with limbal explants (∼0.5–1 mm2) from patients who had undergone pterygium excision. Whole blood (20 ml) was obtained from each patient before surgery and serum prepared by standard method. Explants were placed on contact lenses with 10% autologous serum in Eagles' minimal essential medium.

Results

Immunocytochemical analysis of contact lenses

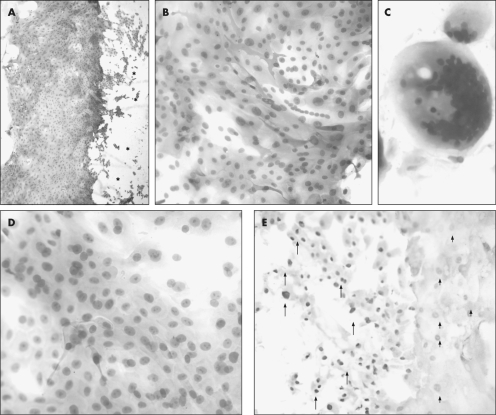

Contact lenses were removed from patients who had undergone surgery for pterygium resection at 1‐week follow‐up, and a migrating front of epithelial cells was noted (fig 1A). Given the intense CK15 expression, we suspected the source of these cells was likely from the donor site. CK15 was expressed by most of these cells, with intense staining at the migrating front (fig 1A, B). Cells at the migrating front also displayed a differential pattern of high (fig 1E, arrows) to moderate (fig 1E, arrowheads) p63 reactivity indicative of proliferative potential. Periodic acid‐Schiff‐positive mucin ball‐like structures (fig 1C) with dense nuclear material were occasionally detected.30 The morphological appearance of the contact lens‐bound cells suggested a homogenous population (fig 1D). Epithelial cells were not detected on balafilcon A (not shown), but were found attached to lotrafilcon A contact lenses (fig 1).

Figure 1 Histological and immunohistochemical assessment of whole‐mounted contact lenses. Contact lenses (lotrafilcon A, A–E) were removed from patients (A and B, patient 1; C, patient 2; D, patient 3; and E, patient 4) who had undergone surgery for pterygium resection. Contact lenses were flat mounted and assessed for keratin 15 expression (A and B), presence of mucin (C, periodic acid‐Schiff), morphological appearance (D, haematoxylin and eosin), and proliferative capacity (E, p63). Immunoreactivity is denoted by the red cytoplasmic (A and B) or nuclear (E) staining. Some contact lenses were counterstained with haematoxylin (A and B) while others were not (E) to avoid masking any nuclear immunoreactivity. The asterisks (*) in panel A indicate the contact lens serial number, which is visible but out of focus. The arrows in panel E point to intensely stained, whereas the arrowheads identify moderately stained p63‐positive cell nuclei. Original magnification ×40 (A), ×200 (B and E), ×400 (C and D).

Limbal explants cultured on contact lenses

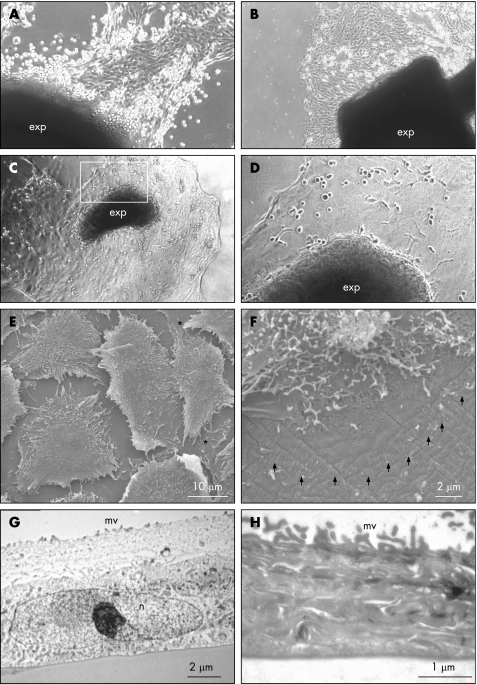

Previously, we reported a method for culturing epithelial cells derived from pterygium,28 conjunctiva27,29 and limbus.27,29 Given the observation that epithelial growth was sustained on contact lenses (fig 1), we focused on determining whether these cells could be propagated on a contact lens surface from limbal explants using autologous serum. Lotrafilcon A (but not balafilcon A) contact lenses provided an ideal substratum for adhesion, migration and rapid expansion of LEC from explants (fig 2C, D). Primary cells were morphologically similar and displayed growth characteristics that resembled autologous epithelium from other regions of the ocular surface grown on plastic (fig 2A, B). These cells were typically uniform, cell‐to‐cell contacts were evident and multiple cell layers developed (fig 2E, asterisks). Other features identified by SEM included extensive microvilli on the apical surface (fig 2E) and cell projections that were suggestive of anchorage points on the contact lens surface (fig 2F, arrowheads). TEM showed flattened, regular cells with prominent nuclei, which were tightly adherent to the contact lens (fig 2G) with prominent microvilli (fig 2H).

Figure 2 Microscopic assessment of limbal‐derived epithelial cells on contact lenses. Primary ocular surface epithelial cells were grown from freshly resected (A, conjunctiva; B, pterygium; C–H, limbal) tissue from patients (A–D, patient 1 and E–H, patient 2) undergoing pterygium surgery, and placed in six‐well tissue culture plates (A and B) or on lotrafilcon A contact lenses (C–H). Phase contrast microscopy showed the presence of and the proliferative capacity of the different ocular surface epithelial cells migrating from tissue explants (A–D, exp) as early as 4 days in culture. The area encompassed by the rectangle in panel C (×40) is magnified in panel D (×100). Cell morphology was also assessed by SEM (E, F) and TEM (G, H). Similar cellular appearance was observed with tissue from at least two other patients (not shown).

Cytokeratin profile of limbal epithelium cultured on contact lenses

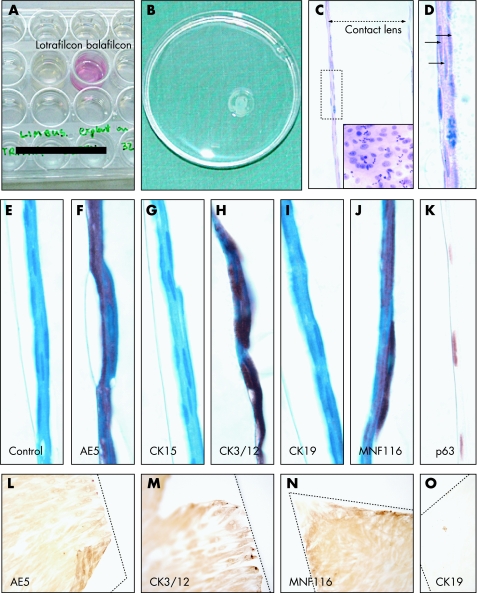

We noted the absence of epithelial growth on some contact lenses harvested from patients at 1‐week follow‐up. It was suspected that this was due to differences in the contact lens composition. To test this hypothesis, remnant limbal graft tissue was cut into two equal portions (∼0.5 mm2), placed on the different contact lenses with autologous serum‐containing medium. Explants did not adhere to balafilcon A (not shown), whereas lotrafilcon A contact lenses promoted adhesion and sustained epithelial growth and migration as reflected by the change in the pH of the medium (fig 3A). After 14 days in culture, lotrafilcon A contact lenses were 80% confluent (fig 3B), and, on sectioning and staining, displayed a multilayered epithelium (fig 3C,D) often with mitotic figures (fig 3C, inset). No morphological signs of terminal differentiation were noted as cells remained flattened and regular (fig 3D–K). Immunoreactivity to AE5, CK3/12, MNF116 and p63 (fig 3F, H, J, K, respectively) was observed, while staining for CK15 and CK19 was absent (fig 3G,I). Next, the compatibility of both contact lenses with passaged LEC was assessed. Balafilcon A did not promote adhesion as cells clumped and no growth was observed (not shown). Cells seeded on to lotrafilcon A were adherent, grew to confluence (fig 3L–O) and displayed similar cytokeratin expression as those derived from limbal explants.

Figure 3 Cytokeratin profile of limbal‐derived epithelial cells on contact lenses. Explants of limbal tissue derived from remnant grafts from one patient (A–K) who had undergone pterygium resection were placed on to the concave surface of either lotrafilcon A (A–K) or balafilcon A (A) contact lens and cultured in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C in 24‐well plates (A). Lotrafilcon A contact lens became confluent (80–90% coverage) after 14 days in culture and were washed in a 60‐mm2 plastic dish in preparation for histological assessment (B). Contact lens were processed for paraffin sectioning (C–K) and stained with haematoxylin and eosin (C, D), a control IgG1 antibody, or with the respective antibodies (see panel labels). Most sections were counterstained with haematoxylin (E–J), except those stained for p63 (K). Additional negative controls included sections incubated without a primary or an IgG2a antibody for which no immunoreactivity was detected (data not shown). The double‐headed arrow in panel C indicates contact lens thickness. The area encompassed by the rectangle in panel C is magnified in panel D, and the three arrows identify a multi‐layered epithelium. Inset C demonstrates several mitotic figures (indicative of proliferative capacity) on a flat‐mounted contact lens. Similar growth pattern and cytokeratin profile was observed in cells grown from at least another two independent limbal explants. Other lotrafilcon A contact lenses were seeded with passaged LEC (L–O). These cells were allowed to reach confluence, the contact lens cut into wedged‐shaped quadrants (contact lens outline marked with a hatched line) and incubated with the antibodies specified on each panel. Original magnification ×400 (C), ×1000 (D–K) and ×200 (L–O).

Discussion

Despite remaining the standard treatment for patients with LSCD and OSD, limbal transplantation is partially effective and long‐term success is dependent on preventing rejection, particularly when allografts are used.31 Animal models have been developed and adapted for patients with OSD where LSCs have been damaged or depleted. A common procedure uses human amniotic membrane, which acts as a supportive structure for cultured ocular epithelial cells. Despite the reported success, there are several disadvantages of this technique. This is a delicate procedure requiring technical skill for the preparation of amniotic membrane with attached corneal epithelial cells, and surgical skills to manipulate the amniotic membrane on to the ocular surface. Amniotic membrane consisting of confluent stem cells is sutured on the corneal surface cell‐side up. This poses a potential time delay, as the transplanted cells must migrate either through or around the amniotic membrane, and degradation of the amniotic membrane may be necessary before stem cell re‐population. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop alternative strategies to overcome these potential problems.

The extended wear lenses used in our current study are first generation Si–Hi‐containing contact lenses, both types with high‐gas‐permeable features compared with conventional hydrogel contact lenses. This feature provides an ideal environment for promoting cell survival, while also acting as a protective shield to facilitate healing and surface reconstruction. We propose that cells cultured on contact lenses will propagate and migrate from their artificial substratum to replenish the damaged ocular surface. Contact lens‐bound cells may also provide secretory factors that promote corneal wound healing, inhibit angiogenesis,32 and rescue or activate any remaining LSCs from their niche. The differences noted in sustaining epithelial cell adhesion and growth on lotrafilcon A compared with balafilcon A contact lenses may be related to variation in chemical composition, surface treatment or surface topography.33 Si–Hi contact lenses cease to move shortly after placement on the ocular surface,34 and this may be another important feature that facilitates cell adhesion and expansion.

If successful, the procedure outlined in this study would not require surgery, apart from harvesting a small biopsy specimen of limbal tissue to establish a primary culture. We acknowledge that one potential complication of our unique transfer system is that several epithelial layers may be lost on contact lens removal and a method to avoid disrupting transfer and healing would be required if sufficient reconstitution has not occurred. Another limitation of our model is that epithelial phenotype may not be preserved on a contact lens surface, although our preliminary data would suggest otherwise. Investigators have noted changes in cytokeratin and p63 expression in cultured limbal explants over a 3‐week period.35 Likewise, connexin‐43 and enhanced proliferative activity were observed in LECs cultured on denuded compared with intact amniotic membrane, suggesting that changes in the immediate microenvironment may regulate epithelial phenotype.36

To our knowledge, reports using a system that resembled the model described herein are scant. In one study, the authors established human LEC from eye bank tissue and seeded these cells on to collagen type I shields for transplantation.37,38 Although encouraging results were recorded, high failure rates were observed that were possibly related to rapid resolution of the shields. Host and donor derived proteases and the cell's inability to form tight adhesive contacts in a short period may have also contributed to these failures. This is a likely explanation, as it was recently shown that limbal cell migration and growth from corneal scleral buttons on amniotic membrane were dependent on the production of MMP‐9.10 Likewise, the use of corneal replacement devices39,40 has resulted in significant melt‐related complications, potentially involving excessive proteolysis. Ang et al41 recently cultivated rabbit conjunctival epithelium in a serum‐free system on membranes made from a bioresorbable polymer. Their results showed the durability and biocompatibility of this polymer towards promoting cell adhesion and proliferation, but this new material has not yet been evaluated on the human eye.

The current study provides valuable preliminary data on the potential use of therapeutic contact lenses as a scaffold for culturing LEC. This system may provide a protective barrier while cells transfer and replenish the ocular surface. Future studies will focus on developing an animal model with a view of using this system to manage LSCD and other severe OSD.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms Jenny Norman, Electron Microscopy Unit, University of New South Wales, for her assistance in performing the electron microscopy studies.

Abbreviations

LEC - limbal epithelial cell

LSC - limbal stem cell

LSCD - limbal stem cell deficiency

OSD - ocular surface disease

SEM - scanning electron microscopy

TEM - transmission electron microscopy

Footnotes

Funding: This work was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (No 350919).

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Cotsarelis G, Cheng S Z, Dong G.et al Existence of slow cycling limbal epithelial basal cells that can be preferentially stimulated to proliferate: implications on epithelial stem cells. Cell 198957201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pellegrini G, Golisano O, Paterna P.et al Location and clonal analysis of stem cells and their differentiated progeny in the human ocular surface. J Cell Biol 1999145769–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holland E, Schwartz G. The evolution of epithelial transplantation for severe ocular surface disease and a proposed classification system. Cornea 199615549–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paangsricharen V, Tseng S C G. Cytologic evidence of corneal diseases with limbal stem cell deficiency. Ophthalmology 19951021476–1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lavker R M, Tseng S C G, Sun T ‐ T. Corneal epithelial stem cells at the limbus: looking at some old problems from a new angle. Exp Eye Res 200478433–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tosi G M, Massaro‐Giordano M, Caporossi A.et al Amniotic membrane transplantation in ocular surface disorders. J Cell Physiol 2005202849–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tosi G M, Traversi C, Schuerfeld K.et al Amniotic membrane graft: histopathological findings in five cases. J Cell Physiol 2005202852–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scuderi N, Alfano C, Paolini G.et al Transplantation of autologous cultivated conjunctival epithelium for the restoration of defects in the ocular surface. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg 200236340–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindberg K, Brown M E, Chaves H V.et al In vitro propagation of human ocular surface epithelial cells for transplantation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1993342672–2679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun C ‐ C, Cheng C ‐ Y, Chien C ‐ S.et al Role of matrix metalloproteinase‐9 in ex vivo expansion of human limbal epithelial cells cultured on human amniotic membrane. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 200546808–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daya S M, Watson A, Sharpe J R.et al Outcomes and DNA analysis of ex vivo expanded stem cell allograft for ocular surface reconstruction. Ophthalmology 2005112470–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hao Y, Ma D H, Hwang D G. Identification of antiangiogenetic and antiinflammatory proteins in human amniotic membrane. Cornea 200019348–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solomon A, Rosenblatt M, Monroy D C.et al Suppression of interleukin‐1α and interleukin‐1β in the human corneal epithelial cells cultured on the amniotic membrane matrix. Br J Ophthalmol 200185444–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reinhard T, Spelsberg H, Henke L.et al Long‐term results of allogeneic penetrating limbo‐keratoplasty in total limbal stem cells deficiency. Ophthalmology 2004111775–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan D T H, Ang L P K, Beuerman R W. Reconstruction of the ocular surface by transplantation of a serum‐free derived cultivated conjunctival epithelial equivalent. Transplantation 2004771729–1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ang L P K, Tan D T H, Beuerman R W.et al Development of a conjunctival epithelial equivalent with improved proliferative properties using a multistep serum‐free culture system. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2004451789–1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ang L P K, Tan D T H, Phan T T.et al The in vitro and in vivo proliferative capacity of serum‐free cultivated human conjunctival epithelial cells. Curr Eye Res 200428307–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ang L P K, Tan D T H, Seah C J Y.et al The use of human serum in supporting the in vitro and in vivo proliferation of human conjunctival epithelial cells. Br J Ophthalmol 200589748–752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pellegrini G, Traverso C E, Franzi A T.et al Long‐term restoration of damaged corneal surfaces with autologous cultivated corneal epithelium. Lancet 1997349990–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakamura T, Inatomi T, Sotozono C.et al Transplantation of cultivated autologous oral mucosal epithelial cells in patients with severe ocular surface disorders. Br J Ophthalmol 2004881280–1284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayashida Y, Nishida K, Yamato M.et al Ocular surface reconstruction using autologous rabbit oral mucosal epithelial sheets fabricated ex vivo on a temperature‐responsive culture surface. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2005461632–1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakamura T, Ang L P K, Rigby H.et al The use of autologous serum in the development of corneal and oral epithelial equivalents in patients with Stevens‐Johnson syndrome. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 200647909–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coroneo M T. Beheading the pterygium. Ophthalmic Surg 199223691–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wishaw K, Billington D, O'Brien D.et al The use of orbital morphine for postoperative analgesia in pterygium surgery. Anaesth Intensive Care 20002843–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Di Girolamo N, McCluskey P J, Lloyd A.et al Expression of MMPs and TIMPs in human pterygia and cultured pterygium epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 200041671–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Girolamo N, Coroneo M T, Wakefield D. UVB‐mediated induction of interleukin‐6 and ‐8 in pterygia and cultured human pterygium epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002: 43;3430–7, [PubMed]

- 27.Di Girolamo N, Coroneo M T, Wakefield D. UVB‐elicited‐induction of MMP‐1 expression in human ocular surface epithelial cells is mediated through the ERK1/2 MAPK‐dependent pathway. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2003444705–4714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di Girolamo N, Tedla N, Kumar R K.et al Culture and characterisation of epithelial cells from human pterygia. Br J Ophthalmol 1999831077–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Di Girolamo N, Chui J, Coroneo M T.et al Pathogenesis of pterygia: role of cytokines, growth factors, and matrix metalloproteinases. Prog Ret Eye Res 200423195–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Millar T J, Papas E B, Ozkan J.et al Clinical appearance and microscopic analysis of mucin balls associated with contact lens wear. Cornea 200322740–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Djalilian A R, Mahesh S P, Koch C A.et al Survival of donor epithelial cells after limbal stem cells transplantation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 200546803–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma H H ‐ K, Tsai R J ‐ F, Chu W ‐ K.et al Inhibition of vascular endothelial cell morphogenesis in cultures by limbal epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1999401822–1828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lopez‐Alemany A, Compan V, Refojo M F. Porous structure of Purevision™ versus Focus® Night&Day™ and conventional hydrogel contact lenses. J Biomed Mater Res 200263319–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nicolson P C, Vogt J. Soft contact lens polymers: an evolution. Biomaterials 2001223273–3283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joseph A, Powell‐Richards A O R, Shanmuganathan V A.et al Epithelial cell characteristics of cultured human limbal explants. Br J Ophthalmol 200488393–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grueterich M, Espana E, Tseng S C G. Connexin 43 expression and proliferation of human limbal epithelium on intact and denuded amniotic membrane. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 20024363–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.He Y ‐ G, McCulley J P. Growing human corneal epithelium on collagen shield and subsequent transfer to denuded cornea in vitro. Curr Eye Res 199110851–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.He Y ‐ G, Alizadeh H, Kinoshita K.et al Experimental transplantation of cultured human limbal and amniotic epithelial cells onto the corneal surface. Cornea 199918570–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hicks C R, Crawford G J, Lou X.et al Corneal replacement using a synthetic hydrogel cornea, AlphaCor™ device, preliminary outcomes and complications. Eye 200317385–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hicks C R, Chirila T V, Werner L.et al Deposits in artificial corneas; risk factors and prevention. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 200432185–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ang L P K, Cheng Z Y, Beuerman R W.et al The development of a serum‐free derived bioengineered conjunctival epithelial equivalent using an ultrathin poly(ε‐caprolactone) membrane substrate. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 200647105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]