Abstract

Background and objectives

Chronic headache is common among patients in neurology clinics. Patients may suffer important economic and social losses because of headaches, which may result in high expectations for treatment outcomes. When their treatment goals are not reached quickly, treatment may be difficult to maintain and patients may consult with numerous health professionals. This retrospective study evaluated the relationship between treatment and the profiles of previous health professionals consulted by patients in a tertiary headache center.

Patients and methods

The records were reviewed of all patients from a headache center who were seen in initial consultation between January 2000 and June 2003. Data related to patient demographic characteristics (sex and age), headache diagnosis, and the profile (quality and quantity) of previous healthcare consultations exclusively related to headache, were collected. The headache diagnoses were confirmed according to the IHS criteria (1988) and to the Silberstein criteria (1994,1996). Although adherence includes taking the prescribed medicines, discontinuing overused symptomatic medications, and changing behavior, among other things, for this study, adherence was defined as when the patient returned at least 2 times within a 3- to 3.5-month period. Patients were separated into groups depending on the number of different healthcare professionals they had consulted, from none to more than 7.

Results

Data from 495 patients were analyzed; 357 were women and 138 were men (ages 6 to 90 years; mean, 41.1 ± 15.05 years). The headache diagnoses included migraine without aura (43.2%), chronic (transformed) migraine (40%), cluster headache (6.5%), episodic tension-type headache (0.8%), and hemicrania continua (0.4%). The 24.2% of patients who sought care from no more than 1 health professional showed a 59.8% adherence rate; 29% of the total had consulted 7 or more health professionals and showed an adherence rate of 74.3% (P = .0004).

Comments

In Brazil, the belief is widespread that patients attending tertiary headache centers tend to be those who have consulted with numerous health professionals and are, therefore, refractory and/or have adherence problems. Despite the limitations imposed by the retrospective design and the fact that we excluded other important markers of real adherence, this study suggested the opposite. The patients who had seen the lowest number of health professionals presented the worse adherence profile. One of the possible reasons is that patients receive more comprehensive care in a specialized center. Further prospective studies to confirm these observations are warranted.

Introduction

Chronic headache is highly prevalent among patients of general practitioners and in specialized centers. Nonetheless, patients frequently are incorrectly diagnosed and often receive suboptimal care, increasing the dissatisfaction among sufferers and compromising the adherence to prescribed treatment.[1,2] Migraine is one of the most widespread and disabling headache disorders encountered in general medical practices, wielding considerable impact on individuals' lives during their most productive years and it is highly costly to the society as well.[1,3]

Despite the ever-expanding therapeutic armamentarium for migraine and other headache types, the determinants of patient satisfaction and degree of adherence with the treatment options are still not fully understood.[4] Recent studies have demonstrated that these patients' first priority is complete and rapid relief of head pain, at least with acute therapies.[5] However, most available medications for migraine and headache attacks are less than ideal in terms of efficacy and/or tolerability.[6] Incomplete headache relief, recurrence, adverse events, and even costs are among the limitations of the current treatment options, even with the formidable advent of the triptans, the first specific agents for migraine. The high expectations of treatment outcomes often frustrate patients and affect adherence. Moreover, some healthcare providers have suggested that those patients with refractory headaches primarily comprise those patients who seek care from numerous health professionals and who have adherence problems.[7]

This goal of this study was to assess the relationship between adherence to consultations and amount of previous consultations with healthcare professionals in patients seen at a tertiary care center.

Patients and Methods

We reviewed the charts of all patients from a private headache center located in the City of Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil, who had been seen for initial consultation between January 2000 and June 2003, collecting data related to demographic characteristics (sex and age), headache diagnosis, and the profile (quality and quantity) of previous consultations with health professionals, exclusively due to headache. The headache diagnoses were made according to the IHS criteria (1988)[8] and the Silberstein and colleagues proposed criteria (1994,1996)[9,10] by the same physician, a neurologist with a full-time headache practice. The profile of previous health professionals consulted for headache was analyzed with specific questions posed during the initial 1-hour consultation, and a detailed questionnaire filled out by all patients, who were asked to choose professionals from a list presented or add the names of professionals consulted who were not included in the list. We (AVK) administered this questionnaire during the initial consultation at the tertiary headache center. We included acupuncture technicians, homeopathy specialists, holistic medicine therapists, and others, as well as health professionals from various other, nonneurologic specialties. Within each of the specialties, we quantified the number of health professionals consulted.

Adherence to a headache strategy treatment involves many aspects: Complying with the prescribed medications and regimen; discontinuing overused symptomatic medications; changing behavior and daily eating, sleeping, and perhaps exercising habits, to name a few. In this study, however, we considered adherence to be when the patient returned for follow-up at least 2 times, which is accomplished, in our center, during a 3- to 3.5-month period (first returning consultation after 5 weeks and returning for follow-up consultation 8 weeks later). The patients were divided according to the number of different healthcare providers they had seen, from none to more than 7. In addition, patients who indicated having consulted providers from another specialty were asked to supply the total number of providers consulted in that particular specialty.

We then compared, among those who have adhered, the profile of professionals consulted. The statistical analysis was performed using contingency tables and qui square tests.

Results

We reviewed the records of 495 patients seen for the first time January 2000 through June 2003. Among these patients, 357 were women and 138 men (ages 6 to 90, mean 41.1 ± 15.05). Headache diagnoses included migraine without aura (214 patients, 43.2%), migraine with aura (11 patients, 2.3%), migraine with and without aura (18 patients, 3.6%), chronic (transformed) migraine (198 patients, 40%), cluster headache (32 patients, 6.5%), chronic (11 patients, 2.3%), and “other,” including episodic (4 patients, 0.8%) tension-type headache, and hemicrania continua (0.4%), among others (Figures 1, 2).

Participants who had been seen by 1 or fewer health professionals accounted for 24.2% of the patients and exhibited a 59.8% adherence rate. Participants who had been seen by 7 or more health professionals accounted for 29% of the whole group, and showed an adherence rate of 74.3% (P = .0004). Patients who had seen 2 to 6 different health professionals had an adherence rate of 72% to 88%. The 495 patients had consulted a total of 2273 health professionals before coming to our center (Figures 3, 4). We were unable to correlate age, gender, socioeconomic status, and headache diagnosis with the analyzed adherence rate. Furthermore, because returning visits were the only endpoint verified among these patients, we did not include the percentage of the patients who followed our treatment strategies.

Discussion

Half of the recurrent headache sufferers fail to adhere properly to treatment.[11] In countries such as Brazil, this problem seems to be even worse because there are few tertiary headache centers with comprehensive approaches and most of these are not covered by insurance companies and health plans. Thus, these kinds of tertiary centers are relatively expensive and out of reach for most people and, therefore, patients seeking help in these facilities are usually considered refractory, with adherence problems, or are “end-of-the-line” patients. Furthermore, by the time patients seek help at a tertiary care center, their primary headaches have been transformed into the daily or near-daily headache commonly associated with overuse of symptomatic medications.[12,13] Consequently, these patients are thought to represent a population that has consulted numerous health professionals and treatment strategies, not always with reliable and scientific background, and will not adhere to the treatment proposed.

Our analysis resulted in a different conclusion, however. First, nearly one fourth of our patients had never consulted with a health professional or had consulted only 1 health professional. In addition, we expected that these relatively treatment-naive patients would exhibit the highest adherence rate, but our analysis revealed a 59.8% adherence rate, significantly lower than the 74.3% rate of those who had seen at least 7 providers.

Second, most of the patients in our cohort did not reflect the profile of frequently seeking medical help that we expected. Those patients who consulted 7 or more health professionals accounted for less than 30% of the subjects in our analysis. Furthermore, patients who had consulted the highest number of health professionals demonstrated the highest adherence rate. We can only speculate that the more comprehensive approach to care that is used in tertiary headache centers may have been responsible for the better adherence rates.

In truth, the usual approach encountered in tertiary headache and pain centers seems to improve adherence among subjects with headache and chronic pain syndromes. Holroyd and colleagues[14] showed, considering acute treatment strategies, that simply adding a brief educational intervention designed to facilitate the effective use of ergotamine resulted in larger reductions in headache activity, compared with headache activity in patients who received the prescription of the same medication without the educational component. The study demonstrated better adherence to the acute treatment scheme and probably to the whole treatment as well.

Despite this improved initial response, the incidence of relapse following successful treatment of recurrent pain is high, ranging from 30% to 60%.[15] Some patients do not understand the biologic nature of a chronic primary headache and the necessity of using these strong drug regimens regularly and for prolonged periods. They may fear potentially harmful side effects with prolonged use. In this study, however, the patients who had consulted more professionals exhibited better adherence rates. We may only speculate that these results may have been related to the impact of education generally provided in tertiary centers, or the better efficacy of the rational polypharmacologic approach used in these facilities.[6]

Another point of interest was the high number of neurologists consulted previously. Although neurologists should be in the best position to help headache patients achieve optimal outcomes,[16] care by these specialists was not sufficient to prevent patients from subsequently seeking help from other professionals. This result may be related to the relatively low interest by clinicians in patients with chronic pain and headache. These patients are usually demanding and time-consuming. In addition, there are clear distinctions between which treatment attributes patients consider important compared with the attributes physicians consider important.[5,17]

We should also consider whether these differences would hold true across different communities and countries. We believe cultural differences play an important role in adherence to treatment related to various chronic disorders. Thus, these differences may not be observed in countries where people have more information about health and have appropriate access to medical care (as in countries such as France, Canada, etc, with socialized medicine.

Although the study methodology was limited and we did not include several important markers of adherence and their relationships with intra-group differences, we observed that most of the patients who sought help at a tertiary headache center may respond well to comprehensive educational approaches along with efficient therapy. This is in contrast to our expectation that these patients would be the most refractory.

Interpretations based on retrospective analysis are always limited by the recall biases both of the patients and physicians. Consulting a higher number of professionals and consulting health professionals other than physicians may be remembered more easily by those who more often engaged in these consultations, which may have introduced bias into our results. Thus, prospective studies would provide more reliable information related to behavioral aspects of headache treatment including adherence, use of symptomatic medication, achievement of expectations, and other factors involved in choosing treatment strategies.

Moreover, the previous consultation of a general practiticioner and even a neurologist do not assure adherence to treatment. Patients who had looked for previous treatments were those with significantly better adherence rates compared with those who consulted a health professional for the first or second time, despite the approach of a tertiary center. Further prospective controlled studies are necessary to confirm these observations.

Figure 1.

Proportions of headache types in 495 patients seen from January 2000 to June 2003.

Figure 2.

Proportions of headache types by gender in 495 patients seen from January 2000 to June 2003.

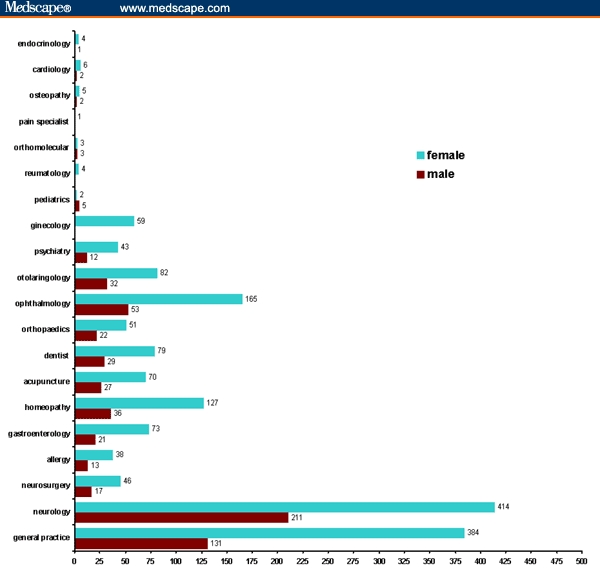

Figure 3.

Types of specialists consulted before the initial consultation at a tertiary headache center.

Figure 4.

Number of health professionals (HP) consulted before the initial consultation at a tertiary care center.

Footnotes

Readers are encouraged to respond to the author at abouchkrym@globo.com or to Paul Blumenthal, MD, Deputy Editor of MedGenMed, for the editor's eyes only or for possible publication via email: pblumen@stanford.edu

Contributor Information

Abouch Valenty Krymchantowski, Outpatient Headache Unit, Instituto de Neurologia Deolindo Couto, Department of Neurology, Hospital Pasteur, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Director, Headache Center of Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Marcus Vinicius Adriano, Headache Center of Rio, Outpatient Headache Unit, Instituto de Neurologia Deolindo Couto, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Renemilda de Góes, Headache Center of Rio, Outpatient Headache Unit, Instituto de Neurologia Deolindo Couto, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Pedro Ferreira Moreira, Department of Neurology, Universidade Federal Fluminense, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Carla da Cunha Jevoux, Department of Neurology, Universidade Federal Fluminense, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Author's email address: abouchkrym@globo.com.

References

- 1.Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Diamond ML, Reed M. Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: data from the American Migraine Study II. Headache. 2001;41:646–657. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2001.041007646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipton RB, Diamond S, Reed M, Diamond ML, Stewart WF. Migraine diagnosis and treatment: results from the American Migraine Study II. Headache. 2001;41:638–645. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2001.041007638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Von Korff M. The burden of migraine. A review of cost to society. Pharmacoeconomics. 1994;6:215–221. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199406030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies GM, Santanello N, Lipton RB. Determinants of patient satisfaction with migraine therapy. Cephalalgia. 2000;20:554–560. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2000.00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lipton RB, Hamelsky SW, Dayno JM. What do patients with migraine want from acute migraine treatment. Headache. 2002;42:S3–S9. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2002.0420s1003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krymchantowski AV. Acute treatment of migraine. Breaking the paradigm of monotherapy. BMC Neurol. 2004;4:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-4-4. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krymchantowski AV. Cefaleias Primarias. Como Diagnosticar e Tratar. 2nd ed. Sao Paulo: Lemos Editorial; 2004. pp. 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain. Cephalalgia. 1988;8:1–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Solomon S, Mathew NT. Classification of daily and near-daily headaches: proposed revisions to the IHS criteria. Headache. 1994;34:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1994.hed3401001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silberstein SD, Lipton RB, Sliwinski M. Classification of daily and near-daily headaches: field trial of revised IHS criteria. Neurology. 1996;47:871–875. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.4.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holroyd KA, Cordingley GE, Pingel JD, Jerome A, Theofanous AG, Jackson DK, Leard L. Enhancing the effectiveness of abortive therapy: a controlled evaluation of self-management training. Headache. 1989;29:148–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1989.hed2903148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krymchantowski AV, Barbosa JSS. Prednisone as initial treatment of drug-induced daily headache. Cephalalgia. 2000;20:107–113. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2000.00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krymchantowski AV, Moreira PF. Out-patient detoxification in chronic migraine: comparison of strategies. Cephalalgia. 2003;23:982–993. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.2003.00648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holroyd KA, Cordingley GE, Pingel JD, Jerome A, Theofanous AG, Jackson DK, Leard L. Enhancing the effectiveness of abortive therapy: a controlled evaluation of self-management training. Headache. 1989;29:148–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.1989.hed2903148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turk DC, Rudy TE. Neglected topics in the treatment of chronic pain patients – relapse, noncompliance, and adherence enhancement. Pain. 1991;44:5–28. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90142-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silberstein S, Lipton R, Goadsby P. Headache in clinical practice. Oxford: Isis Medical Media; 1998. pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lipton RB, Stewart WF. Acute migraine therapy: do doctors understand what patients with migraine want from therapy. Headache. 1999;39:S20–S26. [Google Scholar]