Abstract

Background

Trying to lose weight is a concern for many Americans, but motivation for weight loss is not fully understood. Clinical assessment for obesity treatment is primarily based on measures of body size and physical comorbidities; however, these factors may not be enough to motivate individuals to lose weight. Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) may have a role in an individual's decision to try to lose weight. The objective of this study was to examine the prevalence and association of HRQOL measures as independent moderators of weight loss practices among overweight and obese men and women.

Research Methods and Procedures

Data were from the 2003 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, an annual state-based telephone survey of the civilian noninstitutionalized population of adults 20 years of age or older with BMI ≥ 25.0 kg/m2 (n = 111,456) who responded to 4 standard HRQOL measures that assessed general health status, physical health, mental health, and activity limitation in the past 30 days.

Results

Among men with BMI 25-34.9 kg/m2, the odds of trying to lose weight increased for the moderate vs best category of HRQOL but not for the poorest vs best category, and no associations were noted for men with BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2. Women with BMI 25-34.9 kg/m2 had reduced odds and decreasing associated trends in the prevalence of trying to lose weight with poorer general health, increased physically unhealthy days, and increased activity limitation days. Conversely, women with 1-13 vs 0 mentally unhealthy days had greater odds of trying to lose weight. Among those trying to lose weight, reducing calories was common (52%-69%, men; 56%-69%, women). Among men, with the exception of recent mental health, poorer levels of HRQOL measures were associated with diminished attainment of recommended physical activity levels. Among women, poorer general health status was associated with diminished attainment of recommended physical activity levels.

Discussion

With the exception of recent mental health, HRQOL was differentially associated with trying to lose weight among men and women. Specifically, moderately poor HRQOL among men and better HRQOL among women were associated with trying to lose weight. Consideration of these influences on weight loss may be useful in the treatment and support of obese patients.

Introduction

With the increasing prevalence of obesity and its related morbidities, including numerous chronic diseases, there is a need for overweight and obese individuals to adopt healthy behaviors to prevent further weight gain or to lose weight. An individual's subjective perception of his or her health (ie, low energy level, general health status) and objective medical condition (ie, weight, blood pressure, cholesterol levels) may both be important elements in directing medical treatment and motivating patient behavior change and counseling adherence.

Components of human functioning and well-being or health-related quality of life (HRQOL) have been explored since the 1970s.[1] HRQOL measures have been increasingly used to evaluate the effectiveness of treatment for numerous chronic conditions, and these measures have been used to predict healthcare utilization and adoption of healthier lifestyle behaviors.[2,3] Obesity affects important aspects of HRQOL, including physical health, emotional well-being, and psychosocial functioning.[4–10] Lower HRQOL is associated with higher body mass index (BMI),[4, 6–8, 11–16] and HRQOL has been used to measure the success of obesity treatment.[17–19]

Most studies of HRQOL and trying to lose weight sampled individuals who sought intensive weight loss treatment in a university or hospital setting,[9,12,20,21] with baseline findings of significant differences in psychological distress, coping skills, and eating behaviors both among treatment seekers[9] and when compared with non-treatment-seeking obese adults.[21] Individuals studied were predominantly white women from high socioeconomic groups.[9,12,20,21] Results from these studies, although informative in identifying the lack of homogeneity among obese treatment seekers, are not generalizable to the overall obese population and offer little information about men.

Although trying to lose weight is a concern for many Americans,[22–24] motivation for trying to lose weight is not fully understood. Motivation for weight loss can include perceived appearance, the desire to improve health, or counseling from a physician to lose weight[25–28] and differs by sex.[29] In the early 1980s, Brownell[30] stressed that when dealing with a disorder as complex as obesity, assessment of psychological, social, and medical motivations for trying to lose weight is particularly important. Clinical treatment algorithms for obesity are based primarily on measures of body size and physical comorbidities; however, these objective factors related to physical health may not be enough to motivate individuals to lose weight. Because of the connection between physical and mental health, HRQOL has been suggested as having a role in an individual's decision to try to lose weight.[5,8] Trying to lose weight was found to be associated with increased unhealthy physical days among obese men, suggesting that men may be influenced by traditional clinical assessment tools of weight and comorbidity, but high percentages of women reported trying to lose weight irrespective of weight and HRQOL.[31] Thus, HRQOL may influence or moderate an individual's weight control decisions, and further study of HRQOL measures as independent risk factors associated with weight loss practices is warranted.

The objectives of this study were to examine the prevalence of 4 self-reported HRQOL measures (general health status, recent physical health, recent mental health, and recent activity limitation) and their association with weight loss practices (trying to lose weight, reducing calories, and attaining recommended physical activity) in a large population-based sample of overweight and obese adults stratified by sex and BMI (25.0-29.9 kg/m2, 30.0-34.9 kg/m2, and ≥ 35.0 kg/m2). A specific objective was to evaluate patterns of associations by sex.

Research Methods and Procedures

The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) is a telephone survey conducted by state health departments. Each state, the District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands selected an independent probability sample of noninstitutionalized residents aged 18 years and older. Additionally, data are weighted to the respondents' probability of being selected as well as to the age-, racial/ethnic-, and gender-specific populations for each state, district, or territory. Data from each state and territory are pooled to produce representative estimates. In 2003, a total of 264,684 people responded to the BRFSS survey; descriptions of BRFSS survey methods have been published previously.[32]

Outcomes and Covariates

HRQOL measures

Measures of HRQOL included 4 questions referred to as the Healthy Days measures[33] developed for population surveillance by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 1993 for use in the BRFSS. General health status was assessed with the question, “Would you say that in general your health is excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor?” Recent physical health was then assessed by asking, “Now thinking about your physical health, which includes physical illness and injury, for how many days during the past 30 days was your physical health not good?” Recent mental health was assessed by asking, “Now thinking about your mental health, which includes stress, depression, and problems with emotions, for how many days during the past 30 days was your mental health not good?” Recent activity limitation was assessed with the question, “During the past 30 days, for about how many days did poor physical or mental health keep you from doing your usual activities, such as self-care, work, or recreation?” This question was asked only of those people who reported at least 1 day of poor physical or mental health.

To facilitate clinical interpretation and consistency with previous research that used the Healthy Days measures, each of the 4 HRQOL measurements was categorized into 3 levels. General health status was categorized as excellent/very good, good, and fair/poor. Recent physical health, mental health, and activity limitation were categorized into no (0) days, 1-13 days, and 14-30 days. Respondents who reported no (0) days for both recent physical and mental health were not asked the activity limitation question and therefore were coded as no (0) days for activity limitation. The middle category of each measurement (eg, good, 1-13 days) was considered to be “moderate.”

Weight loss intention and practices

Respondents were asked, “Are you now trying to lose weight?” Those who said yes were defined as trying to lose weight. Survey respondents were asked about what they did to lose weight (eg, reduced calories or attained recommended physical activity), and the practices were defined as previously described.[22, 34–36]

Overweight and obesity

At the end of the interview, respondents were asked to report their current height and weight without shoes. Overweight and obesity were defined with BMI (BMI = weight [kilograms]/height [meters]2) using self-reported height and weight, and were categorized as overweight (25.0-29.9 kg/m2), class I obesity (30.0-34.9 kg/m2), and class II or III obesity (≥ 35.0 kg/m2) in accordance with National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's (NHLBI) guidelines for the identification and treatment of overweight and obesity.[37]

Demographics and comorbidity

Covariates of interest were sex, age in years, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic), educational attainment (less than high school, high school graduate, more than high school), smoking status (current [≥ 100 lifetime cigarettes and currently smoking], former [≥ 100 lifetime cigarettes and not currently smoking], and never) and obesity-related comorbidities (cardiovascular disease risk [CVD] and other). Respondents were classified with CVD if they had been told by a doctor or other health professional that they had hypertension or high blood pressure, high blood cholesterol, or diabetes or sugar diabetes (other than during pregnancy). Respondents were classified with other comorbidity if they had been told by a doctor or other health professional that they had arthritis or that they had and still have asthma.

Analytical Sample

Respondents 20 years of age and older with BMI ≥ 25.0 kg/m2 were eligible for inclusion in the analysis (n = 159,229). Individuals with BMI < 25.0 kg/m2 should not be advised to lose weight, according to the NHLBI clinical guideline's treatment algorithm[37]; therefore, they were excluded from analysis. Respondents with incomplete key variables were excluded, including those without HRQOL or weight control information (n = 19,309), those who were pregnant (n = 1,342), or those with missing race/ethnicity, education, smoking status, or comorbidity variables (n = 27,122). The final analytic sample size was 111,456 (52,513 men; 58,943 women).

Statistical Analysis

Means and frequencies were calculated to describe the population. Logistic regression was used to examine whether HRQOL measures were independently associated with trying to lose weight and with specific weight loss practices. Linear and quadratic trend tests of adjusted prevalence estimates were calculated to determine the presence of a linear relationship between HRQOL measures and the prevalence of trying to lose weight or the prevalence of using a specific weight loss practice (among those who were trying to lose weight). Specifically, trend tests consisted of pairwise comparison of the conditional marginal proportions of the extreme levels of each HRQOL measure followed by a quadratic test for deviation from linear trend in the conditional marginal proportions over the 3 HRQOL levels using polynomial coefficients.[38] All logistic regression models controlled for potential confounders (age, race/ethnicity, education, smoking, CVD risk, other comorbidity) and were stratified by sex and BMI category.

SAS (version 9.1, SAS Institute; Cary, North Carolina) and SAS callable SUDAAN (version 9.0, Research Triangle Institute; Research Triangle Park, North Carolina) were used for the statistical analysis to account for the complex sampling design and to calculate weighted estimates. Data were weighted to the respondent's probability of being selected and the age-, race-, and sex-specific population from the 2003 census. Detailed weighting and analytic methodologies are documented elsewhere.[32] Two-sided hypotheses were assessed and statistical significance was set at P < .05 for all comparisons.

Results

The majority of respondents were white (78.7%), had at least a high school diploma (58.3%), were nonsmokers (30.5% former and 50.6% never), and had substantial CVD risk (60.1%) and moderate prevalence of other comorbidities (39.5%) (data not shown). Characteristics of the weighted sample are described by sex and BMI in the Table . The overall prevalence of trying to lose weight within this overweight and obese population was 55.7% (47.5% men; 66.2% women).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Men and Women 20 Years of Age or Older With BMI ≥ 25.0 kg/m2, 2003 BRFSS

| Men (n = 52,513) | Women (n = 58,943) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI 25.0-29.9 | BMI 30.0-34.9 | BMI ≥ 35.0 | BMI 25.0-29.9 | BMI 30.0-34.9 | BMI ≥ 35.0 | |

| (n = 34,313) | (n = 12,971) | (n = 5,229) | (n = 32,666) | (n = 16,101) | (n = 10,176) | |

(SD) (SD) |

(SD) (SD) |

(SD) (SD) |

(SD) (SD) |

(SD) (SD) |

(SD) (SD) |

|

| Age, y | 51.9 (15.2) | 51.1 (14.0) | 49.6 (13.1) | 54.5 (15.9) | 53.5 (15.1) | 50.2 (13.7) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.2 (1.4) | 32.0 (1.4) | 39.2 (4.5) | 27.2 (1.4) | 32.1 (1.4) | 40.3 (5.2) |

| Race, ethnicity | % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 80.2 (0.5) | 76.6 (0.9) | 74.9 (1.2) | 75.7 (0.5) | 70.4 (0.8) | 65.0 (1.0) |

| Non-Hispanic black | 8.3 (0.3) | 10.9 (0.6) | 12.5 (0.9) | 11.0 (0.3) | 15.5 (0.6) | 21.5 (0.8) |

| Hispanic | 11.5 (0.4) | 12.5 (0.8) | 12.7 (1.1) | 13.3 (0.5) | 14.1 (0.7) | 13.5 (0.9) |

| Trying to lose weight | 37.3 (0.5) | 63.0 (0.8) | 72.5 (1.1) | 59.8 (0.5) | 71.9 (0.7) | 77.2 (0.8) |

| General health status | ||||||

| Excellent/very good | 58.7 (0.5) | 46.4 (0.8) | 32.9 (1.2) | 52.8 (0.5) | 40.5 (0.7) | 29.1 (0.9) |

| Good | 28.6 (0.5) | 33.8 (0.8) | 38.1 (1.2) | 30.7 (0.5) | 35.5 (0.7) | 35.1 (0.9) |

| Fair/poor | 12.7 (0.3) | 19.8 (0.7) | 29.1 (1.1) | 16.6 (0.4) | 24.0 (0.7) | 35.8 (0.9) |

| Recent physical health | ||||||

| 0 days | 70.6 (0.5) | 64.4 (0.8) | 54.6 (1.2) | 61.2 (0.5) | 54.2 (0.7) | 44.3 (1.0) |

| 1-13 days | 20.6 (0.4) | 23.4 (0.7) | 27.7 (1.1) | 26.5 (0.5) | 29.1 (0.7) | 30.8 (0.9) |

| ≥ 14 days | 8.8 (0.3) | 12.3 (0.6) | 17.7 (1.0) | 12.3 (0.3) | 16.7 (0.6) | 25.0 (0.9) |

| Recent mental health | ||||||

| 0 days | 74.6 (0.5) | 72.6 (0.7) | 67.6 (1.2) | 64.4 (0.5) | 61.0 (0.7) | 52.7 (1.0) |

| 1-13 days | 18.5 (0.4) | 18.7 (0.7) | 20.3 (1.0) | 25.2 (0.4) | 25.8 (0.7) | 27.3 (0.8) |

| ≥ 14 days | 6.9 (0.3) | 8.8 (0.5) | 12.1 (0.8) | 10.4 (0.3) | 13.2 (0.5) | 20.0 (0.8) |

| Recent activity limitation | ||||||

| 0 days | 83.5 (0.4) | 79.6 (0.7) | 72.7 (1.1) | 79.0 (0.4) | 74.0 (0.6) | 62.9 (0.9) |

| 1-13 days | 11.4 (0.3) | 12.8 (0.6) | 14.6 (0.9) | 14.5 (0.4) | 16.0 (0.5) | 19.9 (0.7) |

| ≥ 14 days | 5.2 (0.2) | 7.6 (0.4) | 12.7 (0.9) | 6.5 (0.2) | 9.9 (0.4) | 17.2 (0.8) |

| Education | ||||||

| < High school | 8.4 (0.3) | 10.0 (0.5) | 11.6 (0.9) | 11.0 (0.4) | 13.5 (0.6) | 16.4 (0.9) |

| High school | 27.5 (0.5) | 31.4 (0.8) | 32.0 (1.2) | 32.4 (0.5) | 35.7 (0.7) | 34.2 (0.9) |

| > High school | 64.0 (0.5) | 58.7 (0.8) | 56.5 (1.2) | 56.6 (0.5) | 50.8 (0.7) | 49.4 (1.0) |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Current | 20.4 (0.4) | 19.4 (0.7) | 19.2 (1.0) | 17.7 (0.4) | 16.5 (0.5) | 18.0 (0.8) |

| Former | 34.5 (0.5) | 35.7 (0.8) | 33.6 (1.1) | 24.7 (0.4) | 25.6 (0.6) | 26.2 (0.8) |

| Never | 45.1 (0.5) | 44.9 (0.8) | 47.2 (1.2) | 57.6 (0.5) | 57.9 (0.7) | 55.8 (1.0) |

| CVD risk (yes)1 | 54.1 (0.5) | 66.2 (0.8) | 74.1 (1.1) | 55.5 (0.5) | 65.6 (0.7) | 71.6 (0.9) |

| Other comorbidity risk (yes)2 | 29.7 (0.4) | 37.6 (0.8) | 42.9 (1.2) | 42.7 (0.5) | 51.4 (0.7) | 56.9 (1.0) |

CVD risk = presence of diabetes, hypertension, or hypercholesterolemia

Other comorbidity risk = presence of arthritis or asthma

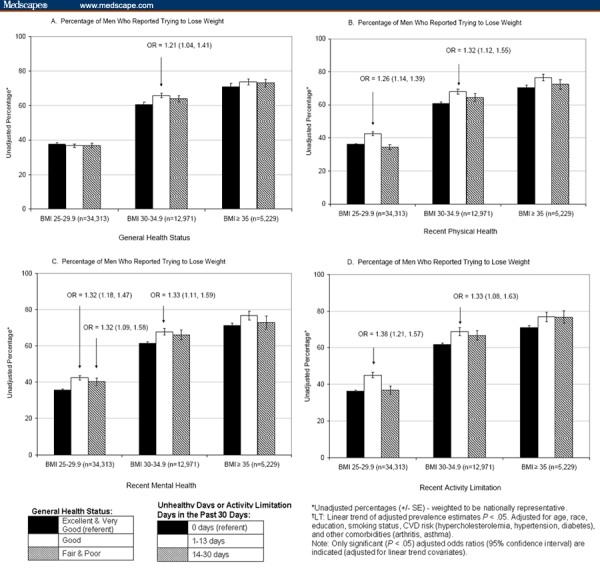

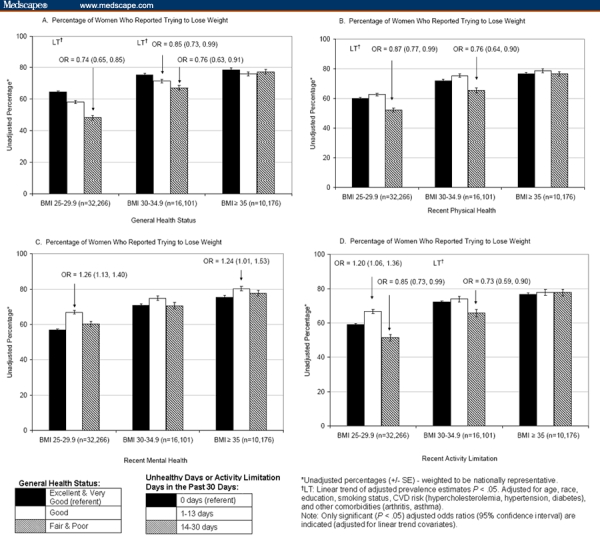

The prevalence of trying to lose weight ranged widely by HRQOL and BMI from about 35% to 77% for men (Figure 1, Panels A-D) and 48% to 80% for women (Figure 2, Panels A-D). No significant linear trends were found between any HRQOL measures and trying to lose weight among men (Figure 1, Panels A-D). Men with BMI 30.0-34.9 kg/m2 and good vs excellent/very good general health (Figure 1, Panel A) and men with BMI 25.0-34.9 kg/m2 and 1-13 vs 0 physically unhealthy days (Figure 1, Panel B), mentally unhealthy days (Figure 1, Panel C), or activity limitation days (Figure 1, Panel D) had greater odds of trying vs not trying to lose weight. HRQOL was not associated with trying to lose among men with BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 (Figure 1, Panels A-D). Women with BMI 25.0-34.9 kg/m2 had significant, decreasing trends in trying to lose weight with poorer general health status (Figure 2, Panel A). Women with BMI 25.0-29.9 kg/m2 had a significant, decreasing trend in trying to lose weight with increased physically unhealthy days (Figure 2, Panel B). Women with BMI 25.0-29.9 kg/m2 and BMI ≥ 35.0 kg/m2 with 1-13 vs. 0 mentally unhealthy days had greater odds of trying vs not trying to lose weight, but no linear trends were present (Figure 2, Panel C). Women with BMI 30.0-34.9 kg/m2 had a significant, decreasing linear trend in trying to lose weight as activity limitation days increased (Figure 2, Panel D). Overweight women with 1-13 vs 0 activity limitation days had higher odds of trying to lose weight, whereas women with ≥ 14 vs 0 activity limitation days had lower odds (Figure 2, Panel D).

Figure 1.

Association of self-reported health-related quality of life with trying to lose weight among men 20 years of age and older, 2003 BRFSS.

Figure 2.

Association of self-reported health-related quality of life with trying to lose weight among women 20 years of age and older, 2003 BRFSS.

Among those trying to lose weight, specific weight loss practices were examined for both men and women (data not shown). The prevalence of using reduced calories was 52%-69% among men and 56%-69% among women and was relatively common regardless of HRQOL measure or level. Overall, the prevalence of attaining recommended weekly physical activity was less prevalent than reducing calories (21%-58% for men; 23%-54% for women). Among men, decreasing linear trends in the prevalence of attaining recommended physical activity were observed for all BMI groups as HRQOL levels declined, with the exception of recent mental health; for women, however, this relationship was only observed for general health status (data not shown). Finally, the prevalence of combining fewer calories with attainment of recommended physical activity was less prevalent and ranged from 15% to 35% for both men and women (data not shown).

Discussion

This study explored HRQOL, trying to lose weight, and weight loss practices in a population-based sample of overweight and obese adults. With the exception of recent mental health, HRQOL was differentially associated with trying to lose weight for men and women. Specifically, moderate HRQOL among men and better HRQOL among women were associated with trying to lose weight. These findings suggest that men may associate poorer HRQOL with their weight and seek to improve health or HRQOL by trying to lose weight. A recent study reported that among obese men, less healthy levels of HRQOL measures were increasingly associated with trying to lose weight; therefore, men may link poor health to greater body weight and try to lose weight on the basis of their subjective evaluation of poor health as measured by HRQOL.[31] Other studies have reported that health-related reasons or medical triggers (eg, “doctor told him to lose weight” or “family member had heart attack”) were often reported as motivation for weight loss among men.[25,39] However, another explanation can be considered, particularly for the greater odds of trying to lose weight found for the mental health measure. The higher prevalence of trying to lose weight with increased mentally unhealthy days might reflect poorer emotional and mental health due to factors associated with currently following a weight loss plan, as suggested by findings of increased depression in men participating in a weight loss program.[40]

The decreasing trends in trying to lose weight found among women with BMI < 35 kg/m2 have not been reported previously; however, a recent study reported that overweight women with good health were half as likely to try to lose weight as women who reported excellent/very good health.[31] This indicates that, among women, better HRQOL was associated with trying to lose weight. An open-ended interview study of reasons given for deciding to lose weight reported that some women said having time and energy to change their lifestyle (eg, altered shopping and eating habits and exercise) contributed to their decision to lose weight.[25] Men did not give this reason; and some men commented that their wives coordinated their dietary changes.[25] The decreasing trends and reduced odds of trying to lose weight among women with poorer HRQOL levels may reflect attitudes that trying to lose weight is time-consuming and requires effort that is not available to women burdened with poor HRQOL. Or, the decreasing trends and reduced odds of trying to lose weight may reflect frustration with failed weight loss attempts and unwillingness to try another weight loss effort; our study design and available data limited determining these associations. In a study of weight cycling, women had significantly poorer general health scores when they reported more than 4 cycles of ≥ 20 pounds of weight loss.[41]

Among women, 1-13 vs 0 mentally unhealthy days were associated with higher odds of trying to lose weight, similar to that seen in men. Burns and coworkers[42] hypothesized from their study of QOL and perceived body weight that overweight women with poorer health are more likely to diet; alternatively, a history of weight loss attempts may lead to lower emotional and mental health QOL scores. These mixed results across HRQOL measures may reflect the complex history that overweight and obese women have in trying to lose weight. Documented influences on women's weight loss efforts include health,[25–28] appearance,[25–28] and body image.[25,43,44] Previous studies show that women try to lose weight at lower BMI than men[22,23] and have unrealistic weight loss expectations for behavioral, pharmacological, and surgical interventions[45]; therefore, our results indicate a need for further qualitative research regarding trying to lose weight and both physical and mental HRQOL for both men and women.

Similar to a recent report,[31] among both men and women who were trying to lose weight, use of reduced calories was fairly prevalent (approximately 60%) and not consistently associated with any of the 4 HRQOL measures. However, for all HRQOL measures except recent mental health, healthier levels were associated with attainment of recommended levels of physical activity among men. Among women, decreasing general health status was associated with decreasing trends in the percent attainment of recommended physical activity. Other researchers have found that individuals with the fewest unhealthy days, regardless of BMI, had the greatest likelihood of engaging in the recommended amount of physical activity.[46–50]

A limitation of the BRFSS survey is the inclusion of only noninstitutionalized adults; therefore, persons in institutions, persons in households without telephones, and the homeless (ie, populations that might have worse HRQOL than others) were excluded.[51,52] Also, the cross-sectional design of BRFSS limits conclusions regarding causal relationships. In addition, all information in BRFSS was self-reported, which may be influenced by “social desirability”[53]; therefore, our estimates of physical activity and dieting may be high. Self-reported estimates of overweight and obesity prevalence may be underestimated because individuals tend to overreport their height and underreport their weight,[53–57] which could lead to misclassification of body weight status. Although evidence exists indicating good measurement properties for the HRQOL measures,[58] reliability might vary by subgroups (eg, age, BMI, and race/ethnicity), by scaling methods used (eg, grouping responses into categories of 0, 1-13, ≥ 14 days), and by response shift (eg, changes in health perceptions after the onset of a chronic illness or injury), affecting judgment and responses to the HRQOL questions.[59] The extensive set of a priori associations among multiple measures of HRQOL and trying to lose weight resulted in the examination of 96 linear trend and logistic regression models (48 for each sex); therefore, 5 significant results would be expected by chance. Our results included 22 significant findings for these tests of trying to lose weight (8 for men and 14 for women), suggesting significant associations beyond those expected by chance alone. Similarly, among those who were trying to lose weight, 288 statistical tests were performed and 14 significant results would be expected by chance. Significant results for the 3 weight control practices totaled 88, and the majority (81) were for the physical activity variables.

A strength of our study is the use of a very large population-based sample rather than a sample of obese patients seeking medical care or weight loss treatment. This large survey sample provided adequate statistical power to stratify all analyses by sex and body weight status, thus allowing for informative public health and clinical inferences for the populations evaluated. The power to stratify all analyses by sex represents another strength of this study, namely the evaluation of a large group of adult men for associations with trying to lose weight. Historically, weight loss research has focused on women, but considering the known differences between the sexes in the prevalence of trying to lose weight,[22–24] the opportunity to study characteristics associated with trying to lose weight in a group of adult men is unique. Another strength is the use of standard HRQOL measures[60] that have been tested for reliability and validity.[2, 61–64] The use of multiple categories for the HRQOL measures is an additional strength and was a methodological recommendation from previous obesity HRQOL research.[8] Finally, HRQOL measures can function as proxies for obesity-related comorbidities such as arthritis; therefore, adjusting for the influence of these comorbidities allowed determination of independent associations between HRQOL measures, trying to lose weight, and weight loss practices.

Conclusion

Numerous factors are associated with the decision to try to lose weight, including appearance and attainment of better health.[25–28] Among men, consistent associations between trying to lose weight and moderate HRQOL were found, and among women, with the exception of recent mental health, better HRQOL was generally associated with trying to lose weight. Generally, at poorer levels of HRQOL, the likelihood of attainment of recommended physical activity levels diminished for both men and women. Thorough assessment of objective physical and medical conditions as well as subjective perceptions of HRQOL may help physicians and weight management professionals develop weight control goals and strategies specific to the individuals who comprise this heterogeneous population.[21]

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the BRFSS coordinators and staff whose cooperation made this survey possible and Cathleen Gillespie for her support in the statistical analysis of data for this project. The authors are also grateful to Dave Moriarty for his willingness to share his time and expertise regarding HRQOL and the specific measures used in this study.

Funding Information

This research was supported in part by an appointment of the first author to the Research Participation Program at CDC, NCCDPHP, Division of Nutrition and Physical Activity, administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the United States Department of Energy and CDC.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of CDC.

Footnotes

Readers are encouraged to respond to the author at aez2@cdc.gov or to Paul Blumenthal, MD, Deputy Editor of MedGenMed, for the editor's eyes only or for possible publication via email: pblumen@stanford.edu

Contributor Information

Connie L. Bish, Nutrition and Health Science Program, Graduate Division of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia; Division of Nutrition and Physical Activity, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Georgia.

Heidi Michels Blanck, Nutrition and Health Science Program, Graduate Division of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia; Division of Nutrition and Physical Activity, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Georgia.

L. Michele Maynard, Division of Nutrition and Physical Activity, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Georgia.

Mary K. Serdula, Nutrition and Health Science Program, Graduate Division of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia; Division of Nutrition and Physical Activity, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Georgia.

Nancy J. Thompson, Nutrition and Health Science Program, Graduate Division of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia; Department of Behavioral Sciences and Health Education, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia..

Laura Kettel Khan, Nutrition and Health Science Program, Graduate Division of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia; Division of Nutrition and Physical Activity, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, Georgia Author's Email: aez2@cdc.gov.

References

- 1.McHorney CA. Health status assessment methods for adults: past accomplishments and future challenges. Annu Rev Public Health. 1999;20:309–335. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.20.1.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav. 1997;38:21–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahlgren SS, Shultz JA, Massey LK, Hicks BC, Wysham C. Development of a preliminary diabetes dietary satisfaction and outcomes measure for patients with type 2 diabetes. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:819–832. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000021694.59992.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doll HA, Petersen SEK, Stewart-Brown SL. Obesity and physical and emotional well-being: Associations between body mass index, chronic illness, and the physical and mental components of the SF-36 questionnaire. Obes Res. 2000;8:160–170. doi: 10.1038/oby.2000.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fontaine KR, Bartlett SJ. Estimating health-related quality of life in obese. Dis Manage Health Outcomes. 1998;3:61–70. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fontaine KR, Barofsky I. Obesity and health-related quality of life. Obes Rev. 2001;2:173–182. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2001.00032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ford ES, Moriarty DG, Zack MM, Mokdad AH, Chapman DP. Self-reported body mass index and health-related quality of life: findings from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Obes Res. 2001;9:21–31. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sullivan M, Karlsson J, Sjostrom Taft C. Why quality of life measures should be used in the treatment of patients with obesity. In: Bjorntorp P, editor. International Textbook of Obesity. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2001. pp. 485–510. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fitzgibbon ML, Kirschenbaum DS. Heterogeneity of clinical presentation among obese individuals seeking treatment. Addict Behav. 1990;15:291–295. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(90)90072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hassan MK, Joshi AV, Madhaven SS, Amonkar MM. Obesity and health-related quality of life: a cross-sectional analysis of the US population. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:1227–1232. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han TS, Tijhuis MA, Lean ME, Seidell JC. Quality of life in relation to overweight and body fat distribution. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1814–1820. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.12.1814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fontaine KR, Cheskin LJ, Barofsky I. Health-related quality of life in obese persons seeking treatment. J Fam Pract. 1996;43:265–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Kosloski KD, Williams GR. Development of a brief measure to assess quality of life in obesity. Obes Res. 2001;9:102–111. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heo M, Allison DB, Faith MS, Zhu SK, Fontaine KR. Obesity and quality of life: Mediating effects of pain and comorbidities. Obes Res. 2003;11:209–216. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goins RT, Spencer SM, Krummel DA. Effect of obesity on health-related quality of life among Appalachian elderly. South Med J. 2003;96:553–557. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000056663.21073.AF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fine JT, Colditz GA, Coakley EH, et al. A prospective study of weight change and health-related quality of life in women. JAMA. 1999;282:2136–2142. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.22.2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fontaine KR, Barofsky I, Andersen RE, et al. Impact of weight loss on health-related quality of life. Qual Life Res. 1999;8:275–277. doi: 10.1023/a:1008835602894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Williams GR, Hartley GG, Nicol S. The relationship between health-related quality of life and weight loss. Obes Res. 2001;9:564–571. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolotkin RL, Crosby RD, Williams GR. Health-related quality of life varies among obese subgroups. Obes Res. 2002;10:748–756. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fontaine KR, Bartlett SJ, Barofsky I. Health-related quality of life among obese persons seeking and not currently seeking treatment. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;27:101–105. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(200001)27:1<101::aid-eat12>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fitzgibbon ML, Stolley MR, Kirschenbaum DS. Obese people who seek treatment have different characteristics than those who do not seek treatment. Health Psychol. 1993;12:342–345. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.12.5.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bish CL, Blanck HM, Serdula MK, Marcus M, Kohl HW, III, Kettel Khan L. Diet and physical activity behaviors among Americans trying to lose weight: 2000 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Obes Res. 2005;13:596–607. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Serdula MK, Mokdad AH, Williamson DF, Galuska DA, Mendlein JM, Heath GW. Prevalence of attempting weight loss and strategies for controlling weight. JAMA. 1999;282:1353–1358. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.14.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kruger J, Galuska DA, Serdula MK, Jones DA. Attempting to lose weight: specific practices among US Adults. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26:402–406. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brink PJ, Ferguson K. The decision to lose weight. West J Nurs Res. 1998;20:84–102. doi: 10.1177/019394599802000106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clarke LH. Older women's perception of ideal body weight: The tensions between health and appearance motivations for weight loss. Ageing Soc. 2002;22:751–773. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Putterman E, Linden W. Appearance versus health: Does the reason for dieting affect dieting behavior? J Behav Med. 2004;27:185–204. doi: 10.1023/b:jobm.0000019851.37389.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Duncan GE, Anton SD, Newton RL, Jr., Perri MG. Comparison of perceived health to physiological measures of health in black and white women. Prev Med. 2003;36:624–628. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dalle Grave R, Calugi S, Magri F, et al. Weight loss expectations in obese patients seeking treatment at medical centers. Obes Res. 2004;12:2005–2012. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brownell K. Obesity: Understanding and treating a serious, prevalent and refractory disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1982;50:820–840. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.6.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bish CL, Blanck HM, Maynard LM, Serdula MK, Thompson NJ, Kettel Khan L. Health-related quality of life and weight loss among overweight and obese U.S. adults, 2001 to 2002. Obesity. 2006;14:2042–2053. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mokdad AH, Stroup DF, Giles WH. Public health surveillance for behavioral risk factors in a changing environment: recommendations from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Team. MMWR. 2003;52:RR–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Methods and Measures. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/methods.htm#measure Accessed June 1, 2006.

- 34.Sapkota S, Bowles HR, Ham SA, Kohl HW., III Adult Participation in Recommended Levels of Physical Activity–United States, 2001 and 2003. MMWR. 2005;54:1208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Physical Activity for Everyone: Recommendations. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/physical/recommendations/index.htm Accessed February 6, 2006.

- 36.Macera CA, Jones DA, Yore MM, et al. Prevalence of Physical Activity, Including Lifestyle Activities Among Adults–United States, 2000-2001. MMWR. 2003;52:764–769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults – The Evidence Report. Bethesda, Md: National Institutes of Health; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN Example Manual, Release 9.0. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2004. pp. 208–220. Chapter 7. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gorin AA, Phelan S, Hill JO, Wing RR. Medical triggers are associated with better short- and long-term weight loss outcomes. Prev Med. 2004;39:612–616. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chaput JP, Drapeau V, Hetherington M, Lemieux S, Provencher V, Tremblay A. Psychobiological impact of a progressive weight loss program in obese men. Physiol Behav. 2005;86:224–232. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Venditti EM, Wing RR, Jakicic JM, Butler BA, Marcus MD. Weight cycling, psychological health, and binge eating in obese women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:400–405. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burns CM, Tijhuis MAR, Seidell JC. The relationship between quality of life and perceived body weight and dieting history in Dutch men and women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:1386–1392. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosen JC, Oroson P, Reiter J. Cognitive behavior therapy for negative body image in obese women. Behav Ther. 1995;26:25–42. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tiggemann M, Rothblum ED. Gender differences in social consequences of perceived overweight in the United States and Australia. Sex Roles. 1988;18:75–86. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Foster GD, Wadden TA, Phelan S, Sarwer DB, Sanderson RS. Obese patients' perceptions of treatment outcomes and the factors that influence them. Arch Int Med. 2001;161:2133–2139. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.17.2133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown DW, Balluz LS, Heath GW, et al. Associations between recommended levels of physical activity and health-related quality of life. Findings from the 2001 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey. Prev Med. 2003;37:520–528. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00179-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown DW, Brown DR, Heath GW, et al. Associations between physical activity dose and health-related quality of life. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:890–896. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000126778.77049.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wendel-Vos GCW, Schuit AJ, Tijhuis MAR, Kromhout D. Leisure time physical activity and health-related quality of life: Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations. Qual Lif Res. 2004;13:667–677. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000021313.51397.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stewart KJ, Turner KL, Bacher AC, et al. Are Fitness, activity, and fatness associated with health-related quality of life and mood in older persons? J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2003;23:115–121. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200303000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kruger J, Bowles HR, Jones DA, Ainsworth BE, Kohl HW., III Health-related quality of life, BMI and physical activity among US adults (>/= 18 years): National Physical Activity and Weight Loss Survey, 2002. Int J Obes. 2007;31:321–327. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dominick KL, Ahern FM, Gold CH, Heller DA. Health-related quality of life among older adults with activity limiting-health conditions. J Ment Health Aging. 2003;9:43–53. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dominick KL, Ahern FM, Gold CH, Heller DA. Health-related quality of life among older adults with arthritis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004;2:5. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fisher RJ. Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect questioning. J Consum Res. 1993;20:303–315. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spencer EA, Appleby PN, Davey GK, Key TJ. Validity of self-reported height and weight in 4808 EPIC-Oxford participants. Pub Health Nutr. 2002;5:561–565. doi: 10.1079/PHN2001322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kuczmarski MF, Kuczmarski RJ, Najjar M. Effects of age on validity of self-reported height, weight, and body mass index: findings from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101:28–34. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nawaz H, Chan W, Abdulrahman M, Larson D, Katz DL. Self-reported weight and height implications for obesity research. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20:294–298. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00293-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Villanueva EV. The validity of self-reported weight in US adults: a population based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2001;1:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-1-11. Available at: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/1/11 Accessed June 19, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Health-Related Quality of Life: Measurement properties: validity, reliability, and responsiveness. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/hrqol/measurement_properties/index.htm Accessed February 22, 2007.

- 59.Norman G. Hi! How are you? Response shift, implicit theories, and differing epistemologies. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:239–249. doi: 10.1023/a:1023211129926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists, Association of State and Territorial Chronic Disease Program Directors. Indicators for chronic disease surveillance. MMWR. 2004;53(No. RR-11) [Google Scholar]

- 61.Andresen EM, Catlin TK, Wyrwich KW, Jackson-Thompson J. Retest reliability of surveillance questions on health related quality of life. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57:339–343. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.5.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jia H, Muenning P, Lubetkin EI, Gold MR. Predicting geographic variations in behavioral risk factors; an analysis of physical and mental health days. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58:150–155. doi: 10.1136/jech.58.2.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Newschaffer CJ. Validation of Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) HRQOL measures in a statewide sample. Atlanta: CDC; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Clark MS, Bond MJ, Prior KN, Cotton AC. Measuring disability with parsimony: evidence for the utility of a single item. Disabil Rehabil. 2004;26:272–279. doi: 10.1080/0963828032000174115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]