Abstract

Binaural detection was examined for a signal presented in a narrow band of noise centered on the on-signal masking band (OSB) or in the presence of flanking noise bands that were random or comodulated with respect to the OSB. The noise had an interaural correlation of 1.0 (No), 0.99 or 0.95. In No noise, random flanking bands worsened Sπ detection and comodulated bands improved Sπ detection for some listeners but had no effect for other listeners. For the 0.99 or 0.95 interaural correlation conditions, random flanking bands were less detrimental to Sπ detection and comodulated flanking bands improved Sπ detection for all listeners. Analyses based on signal detection theory indicated that the improvement in Sπ thresholds obtained with comodulated bands was not compatible with an optimal combination of monaural and binaural cues or to across-frequency analyses of dynamic interaural phase differences. Two accounts consistent with the improvement in Sπ thresholds in comodulated noise were (1) envelope information carried by the flanking bands improves the weighting of binaural cues associated with the signal; (2) the auditory system is sensitive to across-frequency differences in ongoing interaural correlation.

I. INTRODUCTION

The present study concerns binaural hearing and the ability of listeners to use energy at spectral locations removed from the signal frequency to aid signal detection. Before introducing the paradigm used here to investigate this ability, monaural and binaural findings pertinent to the question of across-frequency contributions to hearing performance will be briefly reviewed. Although monaural auditory performance appears to be based upon information in a limited frequency region around the signal in many paradigms (e.g., Fletcher, 1940; Patterson, 1976), other paradigms show that stimulus components well removed from the signal frequency can have important effects on monaural performance. For example, in modulation detection interference (MDI) (Yost and Sheft, 1989; Yost et al., 1989) the presence of amplitude modulation on carriers removed from a target frequency impairs the ability to detect the presence of amplitude modulation at the target frequency. In the phenomenon of comodulation detection differences (CDD), the detection threshold of a narrowband of noise is impeded by the presence of comodulated noise bands at nontarget frequencies (Cohen and Schubert, 1987; McFadden, 1987). Both MDI and CDD results have been attributed, at least in part, to a failure of the auditory system to segregate the information at the target frequency from information present at surrounding frequencies (Cohen and Schubert, 1987; McFadden, 1987; Hall and Grose, 1991; Yost and Sheft, 1994; Oxenham and Dau, 2001; Hall et al., 2006). Energy that is spectrally removed from a target frequency can also improve monaural performance in some paradigms. For example, in profile analysis (Green and Kidd, 1983; Green, 1988) the ability to detect intensity differences in a target tone that is roved in level is improved by the addition of further tones having the same rove as the target. In comodulation masking release (CMR) (Hall et al., 1984) the ability to detect a tone in a narrow band of noise is improved by the addition of further noise bands that have the same temporal envelope as the noise band that is centered on the signal. Performance in these paradigms appears to depend, at least in part, on the ability of the auditory system to compare information across frequency channels. In a similar vein, the phenomenon of monaural envelope correlation perception (Richards, 1987) demonstrates the sensitivity of the ear to across-frequency correlation of temporal envelope. In summary, depending upon the nature of the monaural paradigm, energy removed from the target frequency can have little or no effect, a disadvantageous effect, or an advantageous effect on performance (for a review, see Grose et al., 2005).

As with monaural hearing, there is abundant evidence that energy removed from the signal frequency can have a disadvantageous effect on binaural hearing. “Binaural interference” refers to phenomena wherein the ability to process binaural cues at a target frequency is hindered by the presence of binaural energy at other frequencies and has been demonstrated for interaural time discrimination, interaural level discrimination, binaural lateralization, and the masking-level difference (MLD) (e.g., McFadden and Pasanen, 1976; Dye, 1990; Trahiotis and Bernstein, 1990; Bernstein, 1991; Buell and Hafter, 1991; Woods and Colburn, 1992; Stellmack and Dye, 1993; Bernstein and Trahiotis, 1995). In contrast to monaural hearing, there is sparse evidence that energy in frequency regions removed from a target frequency can have an advantageous effect on the ability to process interaural difference cues that are present at a target frequency. The term “binaural profile analysis” (Woods et al., 1995) has been used to refer to the ability to base binaural performance on the pattern of binaural difference cues across frequency. Woods et al. 1995 examined the ability of listeners to discriminate an interaural time difference (ITD) at a target frequency on the basis of ITD information present across a range of frequencies. In this paradigm, a common ITD for both target and flanking energy was roved from interval to interval, but the target was given an additional ITD in the signal interval. Because of the ITD rove, performance could theoretically be improved by an ability to compare ITDs across frequency. Using a target of 500 Hz and flanking frequencies at harmonics of 100 Hz, Woods et al. 1995 found that the binaural profile information generally degraded performance. In a version of the paradigm that measured sensitivity to changes in interaural correlation, a spectrally continuous noise band was used and the listener was probed for the ability to discriminate a change in the interaural correlation in a 115-Hz-wide portion of the noise. Here, the presence of flanking profile information either had no effect or it degraded performance.

Hall et al. 1988 and Grose et al. 1995 used an MLD paradigm to investigate the possible utility of energy removed from the signal frequency in binaural signal detection. In their paradigm, NoSπ thresholds were measured for an on-signal masking band (OSB), and for the OSB accompanied by comodulated No noise bands. The results from this paradigm have been mixed, with some listeners showing an improvement in Sπ threshold when the comodulated flanking bands were added, and other listeners showing similar OSB and comodulated noise thresholds. In this paper, the term “binaural CMR” will be used to refer to facilitation of binaural signal detection resulting from the addition of co-modulated flanking bands. In similar MLD paradigms employing comodulated flanking bands, Cohen and Schubert (1991) did not find an improvement in binaural thresholds when comodulated flanking bands were added, whereas Schooneveldt and Moore (1989) did find such an improvement. Schooneveldt and Moore showed data averaged over listeners, so individual differences cannot be examined for those data. The data from the listeners who showed an improvement in Sπ thresholds when comodulated bands were added provide at least some indication that energy removed from the signal frequency can aid binaural detection. Hall et al. 1988 proposed a possible account of this masking release in terms of a version of the equalization/cancellation (EC) model (Durlach, 1963). In this account, the EC residuals resulting from cancellation of the time wave forms of comodulated noise bands are likewise comodulated. The residuals are comodulated because the timing errors are assumed to be small with respect to the pseudo periodicity of the envelope of the narrow bands of noise. Given a comodulation of masking noise residuals, a binaural CMR might arise via an across-frequency analysis of the envelopes at the output of an EC mechanism. For example, the envelopes of the residuals of the flanking bands might be used to give high weight to the envelope minima of the residuals of the OSB, as suggested by Buus (1985) for monaural CMR.

In summary, several findings indicate that energy spectrally removed from the signal frequency can be deleterious to binaural performance but evidence that such energy can be advantageous for binaural performance is limited and is not consistent across listeners or studies. The present study explored binaural CMR further, but with an important difference in the characteristics of the masking noise. In the present paradigm, the interaural correlation of the masking noise was either 1.0 (as in previous binaural CMR studies) or was reduced to either 0.99 or to 0.95. Although such slight reductions in masker interaural correlation result in an increase in the Sπ threshold, the MLD for such maskers is still substantial (e.g., Robinson and Jeffress, 1963; McFadden, 1968; van der Heijden and Trahiotis, 1998). It was hypothesized that the masking release for an Sπ signal obtained when comodulated flanking bands are added would be more reliable for maskers having interaural correlation slightly less than 1.0 than for the No maskers investigated in previous experiments. The basis of this hypothesis was related to the relative change in the NoSπ OSB threshold that is obtained when random narrow bands of No flanking noise are added. Cokely and Hall (1991) previously showed that the OSB NoSπ threshold for a narrowband noise is slightly higher (by approximately 3 dB) when random No flanking bands are added. Breebaart et al. 2001b recently proposed an account of this effect in terms of an across-frequency integration of binaural information that arises from the spread of excitation associated with the narrowband OSB masker plus signal (van de Par and Kohlrausch, 1999; Breebaart et al., 2001a). In this spectral integration account, it is assumed that (1) Sπ detection in No noise is limited by internal noise associated with the binaural detection process; (2) the binaural cues associated with the OSB masker plus signal are highly correlated across the different frequency channels to which excitation spreads; and (3) internal noise is uncorrelated across the different frequency channels. Under these assumptions, the detection of an Sπ signal presented in narrowband noise can benefit from an integration of information across the excitation pattern. By this account, Sπ thresholds increase when random No flanking bands are present because the flanking bands mask the spread of excitation associated with the OSB masker plus signal, thereby reducing or eliminating the advantage related to across-frequency integration of binaural information (Breebaart et al., 2001a). This account has important implications for the interpretation of the previous results (Hall et al., 1988; Grose et al., 1995) where some listeners showed similar thresholds between the OSB Sπ condition and the conditions where comodulated flanking bands were added (a result that could easily be interpreted as indicating no binaural CMR). If the hypothesis is correct that flanking bands act to reduce the availability of across-frequency binaural cues arising from the OSB masker plus signal, then the possibility needs to be considered that any positive binaural CMR effects associated with the addition of comodulated flanking bands may be offset by negative effects that the flanking bands have on the availability of spread of excitation cues. In such a case, it would be incorrect to interpret a failure of comodulated flanking bands to improve the Sπ threshold as necessarily indicating a failure to benefit from across-frequency comodulation of masker envelope.

If the above account is correct, then improvements in Sπ thresholds when comodulated flanking bands are added should be more likely to occur in listeners when the masking noise interaural correlation is reduced from 1.0. The hypothesis that across-frequency excitation arising from an OSB masker plus signal can aid binaural detection hinges upon the assumption that the external noise has negligible variability in terms of binaural cues, and that the limits on Sπ signal detection are imposed by internal noise that is independent across the different frequency channels to which the OSB masker-plus-signal excitation spreads (van de Par and Kohlrausch, 1999). Breebaart et al. 2001b proposed that this assumption holds only when the interaural correlation of the masking noise is very close to 1.0. For reduced interaural correlations, the variability in the interaural cues of the masker take on a dominant role in limiting Sπ detection (see also Breebaart and Kohlrausch )2001(, where it was shown that Sπ detection in narrowband noise appears to be limited by internal noise for an No masker and the variability of the binaural cues of the masker when the interaural correlation of the masker is reduced). Because the representation of the external noise variability is expected to be correlated across the excitation pattern of the narrowband masker, a detection benefit based upon across-frequency integration is not expected when the OSB has reduced interaural correlation. Thus, for noise having a reduced interaural correlation, co-modulated noise bands should result in more reliable improvements in Sπ detection because binaural CMR effects will not be offset by the loss of cues associated with the spectral integration. Experiment 1 examined this possibility. Experiment 2 investigated the possibility that a binaural CMR might arise from a combination of monaural and binaural information, and experiment 3 investigated possible binaural mechanisms that might underlie a binaural CMR.

II. EXPERIMENT 1. So AND Sπ DETECTION IN NARROWBAND NOISE MASKERS AS A FUNCTION OF MASKER INTERAURAL CORRELATION

A. Methods

1. Conditions and rationale

Signal thresholds were estimated for two conditions of signal phase (So, Sπ) and three conditions of masker correlation (No, N0.99, N0.95). The masking conditions involved either a single, 25-Hz-wide noise centered on the signal frequency (500 Hz), or the OSB accompanied by comodulated, 25-Hz-wide flanking bands centered at 300, 400, 600, and 700 Hz. Multi-band conditions where the bands within a single ear were comodulated are referred to as COMOD. It was also the case that the interaural correlation was the same across all of the comodulated noise bands (see Stimuli section, below).

Control conditions were run in which the noise band envelopes were random across frequency, but the average interaural correlation for all bands was either 1.0, 0.99, or 0.95. These control conditions were used to help interpret any masking release that occurred for the Sπ conditions for the comodulated noise bands. Specifically, they tested whether a masking release occurred for the N0.99 and N0.95 maskers when the flanking bands simply had the same average interaural correlation as the OSB. Random masker conditions (RAN), where the average interaural correlation was the same across all bands, allowed a test of this possibility. The RAN conditions also allowed examination of the previous finding that random No flanking bands are deleterious to Sπ detection (Cokely and Hall, 1991), and a test of whether this effect also occurs for bands having reduced interaural correlation.

2. Listeners

There were six listeners, four female and two male. Listeners had audiometric thresholds that were better than 20 dB Hearing Level (HL) at octave frequencies from 250 to 8000 Hz. Listener age ranged between 24 and 51 years. All listeners had previous experience in binaural detection tasks.

3. Stimuli

The signal was a 500 Hz pure tone, 200 ms in duration including cosine-squared onset/offset ramps that had a total duration of 51 ms. The tonal signal was generated continuously in RPvds software (TDT) and was gated on and off during the signal interval. Because the tonal signal was free running and because the major factor controlling the timing of signal gating was the response time of the listener, the starting phase of the tonal signal was essentially random. Both level and interaural phase were controlled via multiplication with a scalar adjusted in the inter-stimulus interval.

When only one masker band was present (the OSB condition), it was centered on 500 Hz. When multiple bands were present, they were centered on 300, 400, 500, 600, and 700 Hz. Bands were played continuously at a pressure spectrum level of 50 dB. Maskers were generated in MATLAB prior to each threshold estimation track and were loaded into RPvds for presentation. Bands were generated in the frequency domain by assigning random draws from a normal distribution for the associated real and imaginary components. In the COMOD conditions, a single set of random draws was used to define all five noise bands. In the RAN conditions, different sets of random draws were used to define each band. In conditions where the masker interaural correlation was less than 1.0, two sets of masker bands were generated, set A and set B. Set A was presented to the left ear, and a weighted sum of A and B was presented to the right ear. The relative weights were computed so as to preserve the overall stimulus level and to produce an average interaural correlation of either 0.99 or 0.95. In the COMOD conditions, both A and B were composed of bands that fluctuated coherently across frequency, such that the combination of A and B presented to the right ear likewise fluctuated coherently across frequency. Because the bands centered on each frequency were based upon identical phase and amplitude draws for each ear, the interaural correlations were also identical among bands. In the RAN conditions, both A and B were composed of independent noise samples. Masker arrays were transformed to the time domain using an inverse fast Fourier transform procedure. Each masker array was 216 points, which, when played at 6.103 kHz, resulted in a 10.7 s sample. This masking stimulus was played continuously and repeated seamlessly.

Although the bands within each ear were comodulated in each of the COMOD conditions, the envelopes of the bands were not perfectly correlated across ears for COMOD conditions with interaural correlation of 0.99 or 0.95. The normalized envelope correlation (van de Par and Kohlrausch, 1995; Bernstein and Trahiotis, 1996) has been shown to be approximately the square root of the waveform correlation when the waveform correlation is close to 1.0 (van de Par and Kohlrausch, 1995). Therefore, the normalized interaural correlation of the envelopes of the noise bands was approximately 0.995 for the N0.99 condition and approximately 0.975 for the N0.95 condition.

4. Procedures

All testing was performed using a three-interval, three-alternative forced-choice paradigm. The inter-stimulus interval was 300 ms. Listeners indicated responses via a handheld response box. Listening intervals were indicated with light emitting diodes (LEDs), and feedback regarding the interval containing the signal was provided with a flashing LED following each response.

Using an adaptive threshold estimation procedure, the signal level was adjusted in a three-down, one-up track estimating approximately 79.4% correct (Levitt, 1971). Each track started with a signal level estimated to be approximately 5–10 dB above threshold. Initially the signal level was adjusted in steps of 4 dB. This step was reduced to 2 dB after the second track reversal. Each track continued until eight reversals were obtained, and the threshold estimate for a track was taken as the mean signal level at the last six track reversals. Three such estimates were obtained sequentially in each condition, with a fourth estimate taken in cases where results spanned 3 dB or more (a fourth estimate was obtained in approximately 25% of the conditions). For each listener, the order in which conditions were completed was random.

B. Results and discussion

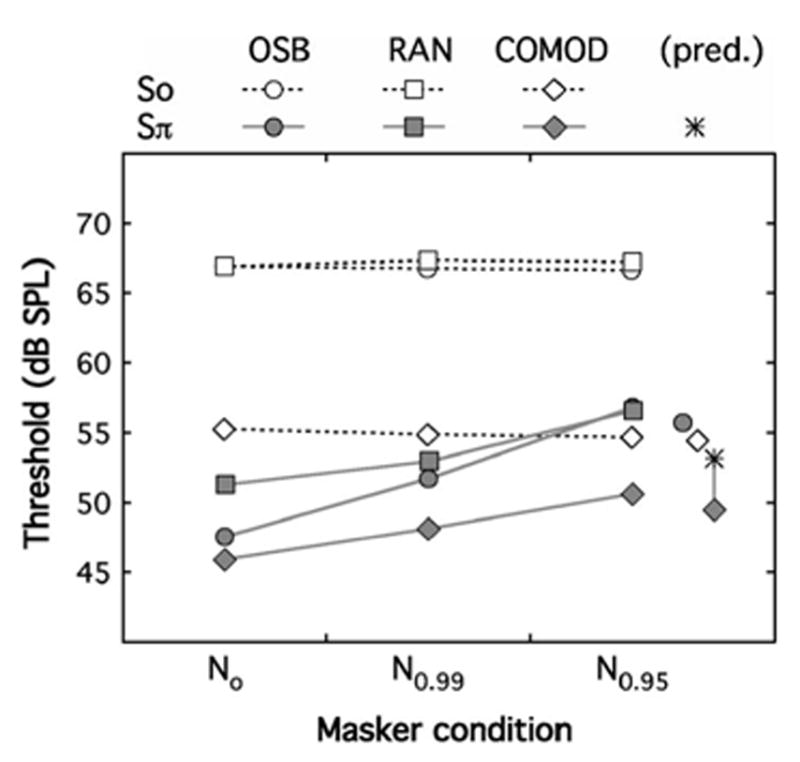

Table I provides numerical values for the individual and the mean masked thresholds, and also shows the derived MLD and CMR values. In order to help portray the overall findings, the mean masked thresholds are also plotted in Fig. 1.

TABLE I.

Individual and mean thresholds (dB SPL) and derived MLDs and CMRs (dB) for experiment 1. Values in parentheses for mean data are inter-listener standard deviations.

| No | N0.99 | N0.95 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OSB | RAN | COMOD | OSB | RAN | COMOD | OSB | RAN | COMOD | |

| L1 So | 65.0 | 65.5 | 51.7 | 66.1 | 65.1 | 52.2 | 64.5 | 66.5 | 50.9 |

| Sπ | 43.3 | 48.2 | 43.6 | 47.4 | 48.2 | 44.7 | 54.5 | 55.5 | 48.9 |

| MLD | 21.7 | 17.3 | 8.1 | 18.7 | 16.9 | 7.5 | 10.0 | 11.0 | 2.0 |

| So CMR | 13.3 | 13.9 | 13.6 | ||||||

| Sπ CMR | −0.3 | 2.7 | 5.6 | ||||||

| L2 So | 66.9 | 67.1 | 54.2 | 65.4 | 67.8 | 51.4 | 65.4 | 67.7 | 55.2 |

| Sπ | 45.8 | 50.4 | 46.3 | 50.6 | 53.7 | 46.4 | 54.1 | 54.1 | 49.6 |

| MLD | 21.1 | 16.7 | 7.9 | 14.8 | 14.1 | 5.0 | 11.3 | 13.6 | 5.6 |

| So CMR | 12.7 | 14.0 | 10.2 | ||||||

| Sπ CMR | −0.5 | 4.2 | 4.5 | ||||||

| L3 So | 66.8 | 66.8 | 55.7 | 66.1 | 67.2 | 57.0 | 66.2 | 67.6 | 56.4 |

| Sπ | 46.4 | 53.4 | 46.1 | 51.2 | 53.1 | 49.1 | 57.2 | 56.8 | 50.8 |

| MLD | 20.4 | 13.4 | 9.6 | 14.9 | 14.1 | 7.9 | 9.0 | 10.8 | 5.6 |

| So CMR | 11.1 | 9.1 | 9.8 | ||||||

| Sπ CMR | 0.3 | 2.1 | 6.4 | ||||||

| L4 So | 68.1 | 67.2 | 54.8 | 67.9 | 65.8 | 56.0 | 67.7 | 66.1 | 53.2 |

| Sπ | 51.2 | 50.2 | 46.4 | 54.8 | 51.3 | 49.1 | 55.9 | 56.4 | 50.8 |

| MLD | 16.9 | 17.0 | 8.4 | 13.1 | 14.5 | 6.9 | 11.8 | 9.7 | 2.4 |

| So CMR | 13.3 | 11.9 | 14.5 | ||||||

| Sπ CMR | 4.8 | 5.7 | 5.1 | ||||||

| L5 So | 68.2 | 66.9 | 59.0 | 67.1 | 69.7 | 56.9 | 68.2 | 66.7 | 57.3 |

| Sπ | 50.0 | 52.6 | 47.7 | 54.7 | 55.7 | 49.4 | 60.3 | 59.3 | 51.4 |

| MLD | 18.2 | 14.3 | 11.3 | 12.4 | 14.0 | 7.5 | 7.9 | 7.4 | 5.9 |

| So CMR | 9.2 | 10.2 | 10.9 | ||||||

| So CMR | 2.3 | 5.3 | 8.9 | ||||||

| L6 So | 66.6 | 68.0 | 56.3 | 67.9 | 68.5 | 56.0 | 67.8 | 68.8 | 55.0 |

| Sπ | 48.7 | 53.1 | 45.5 | 51.7 | 55.7 | 50.2 | 58.8 | 57.7 | 52.3 |

| MLD | 17.9 | 14.9 | 10.8 | 16.2 | 12.8 | 5.8 | 9.0 | 11.1 | 2.7 |

| So CMR | 10.3 | 11.9 | 12.8 | ||||||

| Sπ CMR | 3.2 | 1.5 | 6.5 | ||||||

| X̄So | 66.9 (1.2) | 66.9 (0.8) | 55.3 (2.4) | 66.7 (1.0) | 67.3 (1.7) | 54.9 (2.5) | 66.6 (1.5) | 67.2 (1.0) | 54.7 (2.3) |

| Sπ | 47.6 (2.9) | 51.3 (2.0) | 45.9 (1.4) | 51.7 (2.8) | 53.0 (2.8) | 48.2 (2.1) | 56.8 (2.4) | 56.6 (1.8) | 50.6 (1.2) |

| MLD | 19.3 (1.9) | 15.6 (1.6) | 9.4 (1.4) | 15.0 (2.3) | 14.3 (1.3) | 6.7 (1.1) | 9.8 (1.4) | 10.6 (2.0) | 4.1 (1.8) |

| So CMR | 11.6 (1.7) | 11.8 (2.0) | 11.9 (1.9) | ||||||

| Sπ CMR | 1.7 (2.1) | 3.5 (1.7) | 6.2 (1.5) | ||||||

FIG. 1.

Mean thresholds for experiments 1 (connected symbols on left for No, N0.99 and N0.95) and experiment 2 (symbols on far right). The unfilled symbols show So data and the filled symbols show Sπ data. The circles, squares, and diamonds depict OSB, RAN, and COMOD thresholds, respectively. The asterisk represents the threshold predicted from optimal combination of d′ from the N0.95Sπ OSB condition and the N0.95So COMOD condition (experiment 2).

1. So effects

The So data will first be briefly considered. One clear finding was that the So thresholds for the OSB and the RAN conditions were very similar to each other, both within and across all three noise interaural correlation conditions (see Fig. 1 and details in Table I). The fact that the OSB and RAN So thresholds were similar is consistent with the random flanking bands being outside the monaural critical band centered on the signal (e.g., Fletcher, 1940). The fact that the So thresholds did not change with the interaural correlations examined here is consistent with previous results that have shown a very shallow change in So threshold with small reductions in interaural correlation (e.g., Robinson and Jeffress, 1963). In the present data, it was also the case that the So thresholds in the COMOD conditions were highly similar across all three noise correlation conditions, resulting in So CMRs that were also, on average, highly similar in all three noise correlation conditions (see Table I).

2. Binaural CMR

For each of the three conditions, OSB, RAN, and COMOD, MLDs were derived by subtracting the Sπ threshold from the So threshold. The CMRs were derived by subtracting the COMOD threshold from the OSB threshold (separate CMRs were derived for So and Sπ stimulation). As noted in the introduction, the results of previous studies, where the masking noise was perfectly correlated between ears, showed that improvement in the Sπ threshold due to the presence of comodulated No flanking bands is inconsistent. The present No results are in good agreement with this, with L1–L3 showing nearly the same Sπ threshold for the OSB and the COMOD No condition, and L4–L6 showing a threshold improvement of between 2.3 and 4.8 dB in the COMOD No condition. The main goal of the present experiment was to determine whether such a masking release is more consistent under conditions where the noise masker has an interaural correlation that is less than 1.0. The results are in agreement with this idea. For the N0.99 and N0.95 conditions, all six of the listeners showed better thresholds in the Sπ COMOD condition than the Sπ OSB condition (see trend in Fig. 1 and details in Table I). Across the No, N0.99 and N0.95 conditions, the average improvement in the Sπ threshold when the comodulated flanking bands were added was 1.7, 3.5, and 6.2 dB, respectively. In the NoSπ conditions, it is possible that masking release effects associated with binaural CMR are offset by a loss of spread of excitation cues. For example, although L1–L3 showed about the same Sπ threshold in the No OSB and the No COMOD conditions, this apparent null effect may be a result of offsetting cues: the loss of a spread of excitation cue offsetting the gain of a binaural CMR cue. Note that an unresolved issue is the extent to which the Sπ COMOD threshold may represent a combination of binaural masking release cues associated with the OSB and monaural masking release cues associated with an across frequency analysis (CMR). This will be considered further in the section below and in the following experiment.

Two results related to the addition of random flanking bands are important from the standpoint of binaural CMR. The first pertains to the relative change in the Sπ OSB threshold when the random flanking noise bands were added. In the No condition, the addition of random flanking bands worsened the Sπ threshold by an average of 3.7 dB. This is similar to the effect reported by Cokely and Hall (1991). As noted in the introduction, this kind of effect has recently been accounted for by Breebaart et al. 2001b in terms of reduced availability of spread of excitation cues related to the OSB masker plus signal. Because this account hinges upon Sπ signal detection being limited by internal noise that is independent across the excitation pattern, such an effect is not expected when the variability in the binaural cues of the external noise limits Sπ detection performance (for example, with reduced masker interaural correlation). In agreement with this idea, the deleterious effect of the random flanking bands on Sπ detection was smaller or even absent in the conditions where the interaural correlation of the masking noise was reduced from 1.0. For example, in the N0.95 condition, the average Sπ threshold in the OSB condition was 56.8 dB sound pressure level (SPL) and the average Sπ threshold in the random condition was 56.6 dB SPL.

The second random flanking band result that is of interest from the standpoint of binaural CMR pertains to the conditions where the noise correlation was less than 1.0. It is of interest whether the addition of noise bands that have the same average correlation as the OSB is sufficient to result in a masking release with respect to the OSB Sπ condition. The results indicate that the addition of the random flanking bands did not lower the Sπ threshold obtained in the OSB condition for either the N0.99 or N0.95 conditions. Therefore, the presence of flanking bands having the same average interaural correlation as the OSB was not a sufficient condition to obtain an improvement in relation to the Sπ OSB condition.

3. Possible explanation of binaural CMR based upon the combination of an OSB binaural cue and an across-frequency monaural cue

One interpretation of the binaural CMR is that the co-modulated flanking bands somehow result in an improvement in the processes underlying binaural signal detection. However, an alternative interpretation is that the masking release due to the comodulated flanking bands arises from the combination of a binaural MLD that is associated exclusively with the OSB portion of the stimulus with a monaural CMR that is associated with an across-frequency analysis. For the No condition, such a combination would appear to be unlikely. Here, the average Sπ threshold for the OSB condition was 47.6 dB SPL, but the average So threshold associated with the COMOD condition was a considerably higher 55.3 dB SPL. It is therefore unlikely that the cues associated with monaural CMR would still be useful at the low signal-to-noise ratio associated with the OSB Sπ threshold. However, in the N0.99 and N0.95 conditions, the Sπ OSB thresholds and So COMOD thresholds were of more comparable magnitude, making a potential combination of on-signal binaural information with across-frequency monaural information more feasible. For example, in the N0.95 condition, the average Sπ OSB threshold was 56.8 dB and the average So COMOD threshold was 54.7 dB. As can be seen in Fig. 1, the convergence of the Sπ OSB threshold with the So COMOD threshold for the conditions where the interaural correlation of the noise was slightly less than 1.0 was due entirely to the increase in Sπ threshold that occurs with the decrease in the interaural correlation of the masking noise (Robinson and Jeffress, 1963; van der Heijden and Trahiotis, 1998). Experiment 2, below, was performed to test the idea that the binaural CMR for the maskers having interaural correlation slightly less than 1.0 was simply due to a combination of an OSB binaural masking release with across-frequency monaural masking release.

III. EXPERIMENT 2. A TEST OF WHETHER BINAURAL CMR RESULTS FROM THE COMBINATION OF OSB BINAURAL CUES WITH ACROSS-FREQUENCY MONAURAL CUES

As discussed above, although the improved Sπ detection in the presence of comodulated flanking noise bands is compatible with an interpretation that comodulated flanking bands can enhance the binaural detection process, an alternative possibility is that the improvement simply reflects the combination of cues related to an OSB binaural masking release (MLD) and an across-frequency monaural masking release (CMR). The approach used here to differentiate between these alternatives incorporated fixed-block testing conditions from which psychometric functions were estimated for the Sπ OSB and So COMOD conditions. These psychometric functions allowed the level of performance expected from a combination of OSB binaural and across-frequency monaural cues to be modeled (see details in results section, below). This modeled threshold was then compared to a fixed block threshold obtained for the Sπ COMOD condition. Similar modeled and obtained Sπ COMOD thresholds would be consistent with an interpretation that the obtained Sπ COMOD threshold results from a combination of OSB binaural masking release information with across-frequency monaural masking release information. An obtained Sπ COMOD threshold that is better than the modeled threshold would be consistent with an interpretation that the obtained Sπ COMOD threshold reflects an enhancement of the binaural detection mechanism. The fixed-block conditions used the N0.95 masking noise. The rationale for using the N0.95 masking noise was that experiment 1 indicated that the Sπ OSB threshold and the So COMOD threshold were most similar for this masker. Thus, this masker condition might reasonably be expected to be the one most likely to be associated with a combination of OSB binaural and across-frequency monaural detection cues.

A. Methods

1. Listeners and stimuli

The listeners were the same six individuals who participated in experiment 1. The signal and masker frequencies and the method of stimulus generation were the same as in experiment 1.

2. Procedures

Testing was performed using a fixed-block procedure. The signal level was held constant for each block of 50 trials. The levels chosen for each listener were based on the thresholds for the comparable condition in the adaptive tracks performed in experiment 1. Percent correct was assessed at a minimum of five signal levels, spanning 40%–90%, separated by 2 dB. At least two blocks were run at each signal level, with additional blocks obtained in conditions of high variability (as assessed informally). Percent correct was assessed for three conditions for all listeners: N0.95Sπ/OSB, N0.95So/COMOD and N0.95Sπ /COMOD.

B. Results and discussion

The construction of psychometric functions and subsequent modeling using signal detection theory (Green and Swets, 1966) enabled us to examine the underlying basis of the COMOD Sπ thresholds. Psychometric functions were fitted to percent correct data for each listener separately. A logistic function was used, defined as:

where μ is the threshold parameter and θ is the slope parameter. These two variables were fitted to data in each of the three stimulus conditions using the FMINS function in MATLAB. Resulting fits were used to test the hypothesis that the N0.95Sπ/COMOD condition was based on the combination of OSB binaural cues and across-frequency monaural cues, as independently estimated in the N0.95Sπ/OSB and N0.95So/COMOD conditions, respectively. The functions fitted to the data in these two conditions were used to predict percent correct for a range of signal levels, 35–60 dB in steps of 0.1 dB. These functions were then transformed into d′ and combined optimally using the formula

where and are the d′ values associated with the NoSπ/OSB and NoSo/COMOD conditions, and is the function associated with the optimal combination of independent cues. The assumption of independent cues follows from the assumptions that the NoSo/COMOD threshold reflects the output of a monaural process, whereas the NoSπ/OSB threshold reflects the output of a binaural process. Values of were then converted back into units of percent correct. The signal level most closely approximating 79.4% was identified as the threshold predicted by optimal combination of the binaural and across-frequency cues. If performance in the N0.95Sπ/COMOD condition is based on a combination of these cues, then the threshold estimated in this condition should closely match this prediction.

The data fits to the psychometric functions were quite good, accounting for between 90.6% and 99.9% of the variance in each function. Table II shows the threshold associated with the 79.4% point on the psychometric function for all six listeners. For every listener, the actual performance in the COMOD Sπ condition was better than that predicted on the basis of the combination of binaural and monaural cues. On average, the obtained COMOD Sπ threshold was 3.7 dB better than the threshold predicted on the basis of combined binaural and monaural cues. The four symbols on the far right of Fig. 1 summarize the mean results, with the circles, squares, and diamonds depicting the OSB, RAN, and COMOD thresholds, respectively, and the asterisk showing the threshold predicted from optimal combination of d′ from the N0.95Sπ OSB condition and the N0.95So COMOD condition. A pre-planned paired-samples t test indicated that the difference between the obtained threshold from the N0.95Sπ COMOD condition and the threshold predicted from optimal combination of d′ from the N0.95Sπ OSB condition and the N0.95So COMOD condition was significant (t5 =6.8; p < 0.001). Whereas this outcome is not consistent with a combination of OSB binaural and across-frequency monaural cues, it is consistent with the idea that the obtained binaural CMR reflects an enhancement in binaural detection.

TABLE II.

Individual and mean thresholds (dB SPL) for experiment 2, predicted values of COMOD Sπ thresholds (dB SPL) based upon optimal combination of OSB binaural and across-frequency monaural masking cues, and the Difference (dB) between the predicted and obtained COMOD Sπ thresholds. Values in parentheses show the percent variance accounted for in the fits to the psychometric functions that were used to estimate the obtained thresholds. Values in parentheses for mean data are inter-listener standard deviations.

| Obtained | Predicted | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OSB Sπ | COMOD So | COMOD Sπ | COMOD Sπ | Difference | |

| L1 | 52.4 | 52.4 | 46.9 | 50.4 | 3.5 |

| L2 | 55.6 | 53.2 | 49.9 | 52.5 | 2.6 |

| L3 | 57.4 | 56.9 | 51.2 | 55.5 | 4.3 |

| L4 | 55.7 | 54.8 | 48.1 | 53.5 | 5.4 |

| L5 | 57.4 | 54.4 | 49.3 | 53.3 | 4.0 |

| L6 | 55.9 | 55.2 | 51.7 | 53.9 | 2.2 |

| X̄ | 55.7 (1.8) | 54.5 (1.6) | 49.5 (1.8) | 53.2 (1.7) | 3.7 (1.2) |

IV. EXPERIMENT 3. SPECTRAL PROXIMITY AND THE NATURE OF THE BINAURAL CMR

The final experiment had two aims. The first was to determine the effect of spectrally shifting the flanking bands farther away from the OSB. It is known that monaural CMR effects are larger for relatively close spacing between the OSB and comodulated flanking bands. Whereas this effect may be due to a more potent across-channel effect for relatively proximal bands, it could also reflect a within-channel contribution related to beating between the OSB and flanking bands (Schooneveldt and Moore, 1987). It was of interest to determine whether increasing the spectral separation between the OSB and flanking bands would result in a different pattern of binaural CMR results.

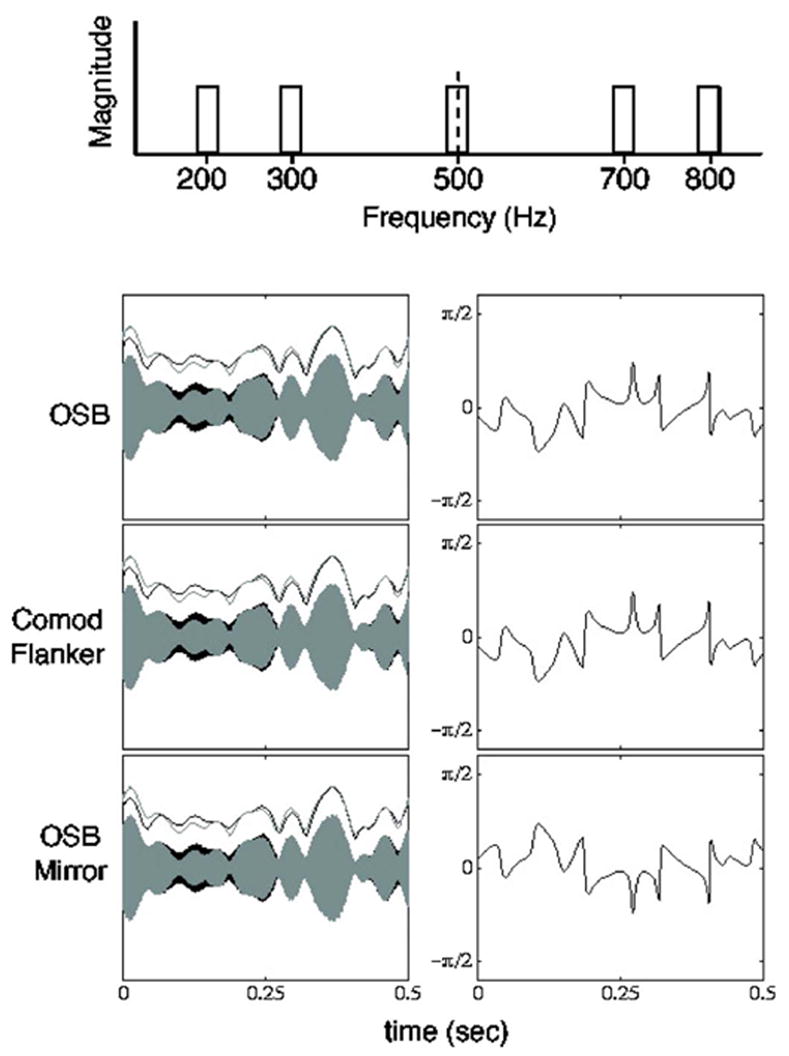

The second aim of the experiment was to explore further the nature of mechanisms underlying the binaural CMR. One goal was to investigate the possible importance of the dynamic binaural difference cues associated with maskers having interaural correlations less than 1.0. One way to conceptualize the deleterious effect of reducing the interaural correlation of the masker on Sπ detection is in terms of the change that the Sπ signal introduces in the ongoing interaural differences of the masking noise. For an No masking noise (interaural correlation of 1.0), there are no interaural differences for the masker alone stimulus, but interaural differences are introduced when the Sπ signal is presented. For a masker with an interaural correlation of less than 1.0, however, ongoing interaural differences exist in the stimulus even for the masker alone. In this case, the listener must be able to differentiate the interaural differences inherent in the noise masker from the interaural differences resulting from the addition of the Sπ signal. The comodulated flanking noise bands used in the present experiments could potentially aid in this differentiation. For example, when flanking noise bands introduce dynamic interaural differences that are identical to those of the noise band centered on the signal, the flanking bands can potentially be used as templates or covariates that could help distinguish the ongoing interaural differences of the noise from the interaural differences introduced by the signal. Provided that the listener is sensitive to the coherence of the dynamic binaural difference cues across frequency, then one possible cue for detection would be a discrepancy in the pattern of interaural cues across frequency. This issue was investigated in the present experiment by comparing performance in two comodulated noise conditions where the interaural correlation of the noise was 0.95, specifically examining the possible role of dynamic interaural phase cues. One condition was like that used in experiments 1 and 2, where the amplitudes and phases of the spectral components constituting each narrowband of noise were exactly the same within each ear. This meant that the dynamic interaural phase differences arising from the reduced interaural correlation were also the same across all bands. The second condition was similar, in that all bands within each ear were comodulated with one another. However, the individual Fourier components composing the OSB (for both ears) were modified: component phase and magnitude were assigned to sequential frequency bins in reverse order and component phase was multiplied by −1. As such, the magnitude spectrum was rotated around the spectral center of the stimulus, forming a “mirror image” of the nonrotated stimulus. Richards (1988) used this technique to examine the possible role of spectral cues in monaural envelope correlation perception. In a CMR experiment, Buss et al. 1998 found that the CMR was approximately the same whether the OSB was generated with the same magnitude spectrum as the comodulated bands or the magnitude spectrum of the OSB was rotated. When considering the effect of this mirror image manipulation on the N0.95 stimulus in terms of its envelope and fine structure, the envelope is not changed but the fine structure is altered. The change in fine structure results in an ongoing pattern of interaural phase differences that is out of phase between the OSB and flanking bands (see Fig. 2). If the binaural CMR depends upon the dynamic interaural phase differences of the masker being the same across frequency, elimination of the binaural CMR would be expected for the “spectral mirror” manipulation. The previous negative “binaural profile analysis” findings of Woods et al. 1995 suggest that the ability to follow dynamic interaural phase differences is likely to be poor, and therefore that the spectral mirror manipulation might have little or no effect on the binaural CMR. However, the stimuli used by Woods et al. were different in several ways from those used here: in their experiment probing sensitivity to across-frequency differences in interaural phase, pure tones having nondynamic interaural phase differences were employed; in their experiment probing sensitivity to across-frequency differences in interaural correlation of noise, spectrally continuous stimuli were used. It is possible that the present approach, involving multiple narrowband noises having coherent, dynamically changing interaural phases changes would result in across-frequency interaural phase cues that were more salient. A finding of little effect on the binaural CMR in the spectral mirror condition would be consistent with an interpretation that the crucial stimulus characteristic underlying binaural CMR is envelope comodulation.

FIG. 2.

The top panel shows a schematic of the noise bands used in conditions of experiment 3. The left-hand lower panels show time domain samples of representative noise stimuli having interaural correlation of 0.95. The left and right ear stimuli are overlaid, with the left ear shown in gray, and the right ear shown in black. The envelopes of the left and right ear stimuli are depicted above the time domain samples. The “OSB” and “Co-mod Flanker” panels can be compared to depict the relation between the OSB and a flanking band for the COMOD condition. The “OSB Mirror” and “Comod Flanker” panels can be compared to depict the relation between the OSB and a flanking band for the COMOD MIRROR condition. The right-hand lower panels show interaural phase as a function of time. The figure shows that although the interaural phase functions are in-phase for the COMOD conditions (compare “OSB” and “Comod Flanker”), they are out of phase for the COMOD MIRROR conditions (compare “OSB Mirror” and “Comod Flanker”).

A. Methods

Five of the listeners from experiments 1 and 2 participated (listener L4 from the previous experiments did not participate). The stimuli were generated in the same way as in experiment 1 and 2, using the same stimulus parameters, with two exceptions. One exception was that psychometric function data for the OSB condition were not retaken, as the OSB data were available from experiment 2. The second exception was that the flanking bands were moved away from the OSB: whereas the center frequency of the OSB remained at 500 Hz, the two lower bands were now centered on 200 and 300 Hz and the two higher bands were now centered on 700 and 800 Hz. Percent correct was measured for a range of levels in the N0.95So/COMOD and N0.95Sπ/COMOD conditions using the same fixed-block testing procedures that were used in experiment 2. In the comodulated noise conditions, thresholds were obtained both for conditions where the noise was comodulated as in experiments 1 and 2 (COMOD) and for conditions where the spectral mirror manipulation was performed on the OSB (COMOD MIRROR).

B. Results and discussion

The data obtained from the psychometric functions were used in the same way as in experiment 2 to model the thresholds expected from optimal combination of binaural OSB and monaural across-frequency signal detection cues. The Sπ thresholds for the COMOD condition were modeled from the psychometric functions that were fitted to the N0.95Sπ OSB data and the N0.95So COMOD data. The Sπ thresholds for the COMOD MIRROR condition were modeled from the psychometric functions that were fitted to the N0.95Sπ OSB data and the N0.95So COMOD MIRROR data. Table III shows results from the data fits for the five listeners. The pattern of results was similar to that obtained in experiment 2. The function fits were again quite good, with the percent of variance accounted for ranging between 90.1% and 99.9%. For every listener, the actual performance in the COMOD and COMOD MIRROR Sπ condition was again better than that predicted on the basis of the optimal combination of binaural and monaural cues. Pre-planned t tests indicated that the differences between predicted and obtained thresholds were significant both for the COMOD (t4 =9.4; p =0.001) and the COMOD MIRROR (t4 =5.9; p =0.004) conditions. These outcomes were again inconsistent with an interpretation that performance in these conditions results from an optimal combination of OSB binaural and across-frequency monaural cues. A finding of note was that the Sπ threshold in the COMOD conditions was significantly better, by an average of 1.6 dB (see Table III), than that in the COMOD MIRROR conditions (t4 =7.4; p =0.002). One possible interpretation of this finding is that dynamic binaural phase differences contribute to binaural CMR and that the change in the across-frequency differences in these cues in the COMOD MIRROR condition reduces the binaural CMR. Even if this interpretation is correct, the finding that a significant binaural CMR occurs in the COMOD MIRROR condition indicates that across-frequency equivalence of dynamic binaural phase differences is not a necessary condition for a binaural CMR. Furthermore, it is not clear that the reduction of the binaural CMR in the COMOD MIRROR condition is binaural in origin, as there was a similar reduction in CMR in the So data. That is, the So threshold in comodulated noise was about 1.5 dB smaller on average in the COMOD MIRROR condition than the COMOD condition (see Table III). The source of this small effect is not clear.

TABLE III.

Individual and mean thresholds (dB SPL) for experiment 3, predicted values of COMOD and COMOD MIRROR Sπ thresholds (dB SPL) based upon optimal combination of OSB binaural and across-frequency monaural masking cues, and the Difference (dB) between the predicted and obtained COMOD Sπ thresholds. Values in parentheses for mean data are inter-listener standard deviations.

| Obtained | Predicted | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| So | Sπ | Sπ | Difference | ||

| L1 | COMOD | 53.5 | 49.1 | 51.2 | 2.1 |

| MIRROR | 54.0 | 50.4 | 51.3 | 0.9 | |

| L2 | COMOD | 55.1 | 49.8 | 53.6 | 3.8 |

| MIRROR | 57.1 | 51.9 | 53.9 | 2.0 | |

| L3 | COMOD | 58.8 | 52.5 | 56.4 | 3.9 |

| MIRROR | 59.0 | 53.6 | 56.3 | 2.7 | |

| L5 | COMOD | 54.8 | 50.4 | 54.0 | 3.6 |

| MIRROR | 56.8 | 52.4 | 55.0 | 2.6 | |

| L6 | COMOD | 56.0 | 51.5 | 54.4 | 2.9 |

| MIRROR | 58.6 | 53.3 | 55.1 | 1.8 | |

| X̄ | COMOD | 55.6 (2.0) | 50.7 (1.3) | 53.9 (1.9) | 3.2 (0.8) |

| MIRROR | 57.1 (2.0) | 52.3 (1.2) | 54.3 (1.9) | 2.0 (0.7) |

Comparison of the present results to those of experiment 2 reveals that moving the flanking bands farther away from the OSB did not have a large effect on the obtained So and Sπ thresholds. For example, in the closer spectral spacing used in experiment 2, the average N0.95So COMOD threshold was 54.5 dB SPL, compared to an average N0.95So COMOD threshold of 55.6 dB SPL in the present experiment. In experiment 2, the average N0.95Sπ COMOD threshold was 49.5 dB SPL, compared to an average N0.95Sπ COMOD threshold of 50.7 dB SPL in the present experiment. These results suggest that within-channel cues probably did not play a large role in the results of the COMOD conditions of experiment 2.

V. GENERAL DISCUSSION

One of the main findings of the present study was that although the masking release for an Sπ signal was increased in only three of six listeners when comodulated No flanking bands were added to an No OSB, an increase in masking release occurred for all six listeners when comodulated flanking bands were added in the N0.99 and N0.95 conditions. One parsimonious interpretation of this consistent increase in masking release would involve the combination of a binaural OSB masking release cue with an across-frequency, monaural masking release cue. However, the analyses of the psychometric functions derived from the fixed block conditions did not support this interpretation.

The spectral mirror conditions were helpful in probing the nature of the processes that are likely to give rise to the binaural CMR. The results of these conditions indicated that a mechanism based upon the across-frequency analysis of dynamic binaural phase differences was not likely to form the basis of binaural CMR. This interpretation is consistent with previous “binaural profile analysis” results which indicated poor sensitivity to across-frequency cues based upon binaural interaural time differences (Woods et al., 1995).

A qualitative account of binaural CMR that is consistent with the present results is suggested by recent studies that have indicated that the Sπ thresholds for tones presented in narrowband noise are determined largely by information coincident with masker envelope minima (Grose and Hall, 1998; Hall et al., 1998; Buss et al., 2003), where the binaural difference cues are the largest (Buss et al., 2003). Because narrow bands of noise have prominent envelope fluctuations, the magnitude of the binaural difference cues associated with a signal will vary considerably as a function of time. Acute binaural signal detection for such stimuli may therefore depend upon a selective weighting of temporal epochs characterized by relatively high signal-to-noise ratios. This is similar to the idea proposed by Buus to account for monaural CMR (Buus, 1985). A factor that will limit the ability of the auditory system to identify such epochs is the presumed internal noise associated with the relevant binaural difference cues. A qualitative account of binaural CMR is that comodulated flanking bands provide information that can reduce the effect of such noise. Specifically, the envelopes of the co-modulated flanking bands may be used to weight the binaural cues at the signal frequency such that relatively high weight is given to the temporal epochs associated with the masker envelope minima, and therefore the largest binaural difference cues. The envelope cues might arise either from the monaural representations of the flanking band temporal envelopes or, as noted in the introduction, from the envelopes available at the outputs of an EC process (Durlach, 1963).

Another qualitative account that is consistent with the binaural CMRs found for noise interaural correlations of 0.99 and 0.95 is that listeners can benefit from across-frequency comparisons of the ongoing interaural correlation. For example, consider a mechanism that monitors the interaural correlation at the outputs of sliding binaural temporal windows associated with different frequency channels. For both the COMOD and COMOD MIRROR cases, the interaural correlations at the outputs of the temporal windows would be the same across the frequency channels, except when the Sπ signal was present. Note that this strategy would not be effective in the 0.99 and 0.95 interaural correlation RAN conditions of experiment 1 due to the fact that the interaural correlations of the noise would not be exactly the same when measured over finite temporal epochs (only the long-term average interaural correlation would be the same). Although this account is consistent with the results from the RAN, COMOD, and COMOD MIRROR 0.99 and 0.95 interaural correlation conditions, it does not appear to be consistent with the data from the No RAN condition. In the No RAN condition, the outputs of binaural temporal windows would be expected to indicate near perfect interaural correlation across frequency, except when the Sπ signal was present. Whereas the across-frequency difference in interaural correlation resulting from signal presentation might be expected to aid detection in this case, the presence of the random No flanking bands actually led to a reduction in sensitivity to the Sπ signal in relation to the OSB base line threshold (see Table I). One possibility is that any positive effect in terms of an across-frequency comparison of interaural correlation is more than offset by a loss of spread of excitation cues related to the OSB (Breebaart et al., 2001b). It is therefore difficult to rule out the possibility that such a mechanism contributed to binaural masking release in conditions where the interaural noise correlation was less than 1.0.

VI. CONCLUSIONS

Previous and present data indicated that the improvement in the threshold of an Sπ signal when comodulated flanking bands are added to an OSB does not occur consistently across listeners when the masking noise has an interaural correlation of 1.0. The results of the present study showed that this masking release effect was consistent, occurring in all six of the listeners tested, when the interaural correlation was slightly less than 1.0. The present findings are consistent with an interpretation that binaural CMR may sometimes appear to be absent in No masking noise because of a separate factor related to the integration of binaural information resulting from spread of excitation associated with the OSB+signal. Whereas the addition of comodulated flanking bands provides information that can contribute to a binaural CMR, the bands may also mask binaural information that arises from spread of excitation associated with the OSB+signal.

When flanking bands with random envelopes were added to an OSB, the Sπ threshold increased when the noise was No, but this effect of random flanking bands was reduced or absent when the interaural correlation of the masking noise was reduced to 0.99 or 0.95.

The results of fixed-block testing and associated psychometric functions were not consistent with an interpretation that the binaural CMR is a result of the combination of OSB binaural and across-frequency monaural masking release cues.

The results of spectral mirror conditions indicated that across-frequency coherence of dynamic interaural phase differences is not a necessary condition for a binaural CMR.

A qualitative account of binaural CMR that is consistent with the results obtained here is that the envelope minima associated with the comodulated flanking bands may be used by the auditory system to give relatively high weight to the temporal epochs associated with the largest binaural difference cues. The binaural masking release obtained in the N0.99 and N0.95 conditions is also consistent with an account based upon an across-frequency analysis of dynamic interaural correlation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH, RO1 DC00397. We thank Madhu B. Dev and Heidi Reklis for assistance in running subjects and technical support. We thank Armin Kohlrausch and three anonymous reviewers for many insightful comments that aided clarity and interpretation.

References

- Bernstein LR. Spectral interference in a binaural detection task. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1991;89:1306–1313. doi: 10.1121/1.400655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein LR, Trahiotis C. Binaural interference effects measured with masking-level difference and with ITD- and IID-discrimination paradigms. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1995;98:155–163. doi: 10.1121/1.414467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein LR, Trahiotis C. On the use of the normalized correlation as an index of interaural envelope correlation. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1996;100:1754–1763. doi: 10.1121/1.416072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breebaart J, Kohlrausch A. The influence of interaural stimulus uncertainty on binaural signal detection. J Acoust” Soc Am. 2001;109:331–345. doi: 10.1121/1.1320472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breebaart J, van de Par S, Kohlrausch A. Binaural processing model based on contralateral inhibition” I Model structure. J Acoust Soc Am. 2001a;110:1074–1088. doi: 10.1121/1.1383297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breebaart J, van de Par S, Kohlrausch A. Binaural processing model based on contralateral inhibition” II Dependence on spectral parameters. J Acoust Soc Am. 2001b;110:1089–1104. doi: 10.1121/1.1383298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buell T, Hafter E. Combination of binaural information across frequency bands. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1991;90:1894–1901. doi: 10.1121/1.401668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss E, Hall JW, Grose JH. Change in envelope beats as a possible cue in comodulation masking release (CMR) J Acoust” Soc Am. 1998;104:1592–1597. doi: 10.1121/1.421304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss E, Hall JW, Grose JH. The masking level difference for signals placed in masker envelope minima and maxima. J Acoust” Soc Am. 2003;114:1557–1564. doi: 10.1121/1.1598199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buus S. Release from masking caused by envelope fluctuations. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1985;78:1958–1965. doi: 10.1121/1.392652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MF, Schubert ED. The effect of cross-spectrum correlation on the detectability of a noise band. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1987;81:721–723. doi: 10.1121/1.394839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MF, Schubert ED. Comodulation masking release and the masking-level difference. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1991;89:3007–3008. doi: 10.1121/1.400739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cokely JA, Hall JW. Frequency resolution for diotic and dichotic listening conditions compared using the bandlimiting measure and a modified bandlimiting measure. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1991;89:1331–1340. doi: 10.1121/1.400537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlach NI. Equalization and cancellation theory of binaural masking-level differences. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1963;35:1206–1218. [Google Scholar]

- Dye R. The combination of interaural information across frequencies: Laterlization on the basis of interaural delay. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1990;88:2159–2170. doi: 10.1121/1.400113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher H. Auditory patterns. Rev” Mod Phys. 1940;12:47–65. [Google Scholar]

- Green DM. Profile Analysis. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Green DM, Kidd G., Jr Further studies of auditory profile analysis. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1983;73:1260–1265. doi: 10.1121/1.389274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DM, Swets JA. Signal Detection Theory and Psychophysics. Wiley; New York: 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Grose JH, Hall JW, Buss E. Across-channel spectral processing. In: Malmierca MS, Irvine DRF, editors. Auditory Spectral Processing. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2005. pp. 88–119. [Google Scholar]

- Grose JH, Hall JW., III Masker fluctuation and the masking-level difference. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1998;103:2590–2594. doi: 10.1121/1.422779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grose JH, Hall JW, Mendoza L. Developmental effects in complex sound processing. In: Manley GA, Klump GM, Koppl C, Fastl H, Oekinghaus H, editors. 10th International Symposium on Hearing. World Scientific; Singapore: 1995. pp. 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Hall JW, Buss E, Grose JH. Comodulation detection differences for fixed-frequency and roved-frequency maskers. J Acoust” Soc Am. 2006;119:1021–1028. doi: 10.1121/1.2151788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JW, Cokely J, Grose JH. Signal detection for combined monaural and binaural masking release. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1988;83:1839–1845. doi: 10.1121/1.396519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JW, Grose JH. Some effects of auditory grouping factors on modulation detection interference (MDI) J Acoust” Soc Am. 1991;90:3028–3036. doi: 10.1121/1.401777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JW, Grose JH, Hartmann WM. The masking-level difference in low-noise noise. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1998;103:2573–2577. doi: 10.1121/1.422778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JW, Haggard MP, Fernandes MA. Detection in noise by spectro-temporal pattern analysis. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1984;76:50–56. doi: 10.1121/1.391005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt H. Transformed up-down methods in psychoacoustics. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1971;49:467–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden D. Masking level differences determined with and without interaural disparities in masker intensity. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1968;44:212–223. doi: 10.1121/1.1911057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden D. Comodulation detection differences using noise-band signals. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1987;81:1519–1527. doi: 10.1121/1.394504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden D, Pasanen EG. Lateralization at high frequencies based on interaural time differences. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1976;59:634–639. doi: 10.1121/1.380913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxenham AJ, Dau T. Modulation detection interference: Effects of concurrent and sequential streaming. J Acoust” Soc Am. 2001;110:402–408. doi: 10.1121/1.1373443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson RD. Auditory filter shapes derived with noise stimuli. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1976;59:640–654. doi: 10.1121/1.380914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards VM. Monaural envelope correlation perception. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1987;82:1621–1630. doi: 10.1121/1.395153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards VM. Components of monaural envelope correlation perception. Hear” Res. 1988;35:47–58. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(88)90039-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson DE, Jeffress LA. Effect of varying the interaural noise correlation on the detectability of tonal signals. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1963;35:1947–1952. [Google Scholar]

- Schooneveldt GP, Moore BCJ. Comodulation masking release (CMR): Effects of signal frequency, flanking band frequency, masker bandwidth, flanking band level, and monotic vs dichotic presentation flanking bands. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1987;82:1944–1956. doi: 10.1121/1.395639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schooneveldt GP, Moore BCJ. Comodulation masking release (CMR) for various monaural and binaural combinations of the signal, on-frequency, and flanking bands. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1989;85:262–272. doi: 10.1121/1.397733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellmack MA, Dye RH. The combination of interaural information across frequencies: The effects of number and spacing of components, onset asynchrony, and harmonicity. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1993;93:2933–2947. doi: 10.1121/1.405813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trahiotis C, Bernstein LR. Detectability of interaural delays over select spectral regions: Effects of flanking noise. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1990;87:810–813. doi: 10.1121/1.398892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Par S, Kohlrausch A. Analytical expressions for the envelope correlation of certain narrow-band stimuli. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1995;98:3157–3169. [Google Scholar]

- van de Par S, Kohlrausch A. Dependence of binaural masking level differences on center frequency, masker bandwidth, and interaural parameters. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1999;106:1940–1947. doi: 10.1121/1.427942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Heijden M, Trahiotis C. Binaural detection as a function of interaural correlation and bandwidth of masking noise: Implications for estimates of spectral resolution. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1998;103:1609–1614. doi: 10.1121/1.421295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods W, Brughera A, Colburn H. Binaural profile analysis: On the comparison of interaural time difference and interaural correlation across frequency. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1995;97:3280. [Google Scholar]

- Woods WS, Colburn HS. Test of a model of auditory object formation using intensity and interaural time difference discrimination. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1992;91:2894–2902. doi: 10.1121/1.402926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yost WA, Sheft S. Across-critical-band processing of amplitude-modulated tones. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1989;85:848–857. doi: 10.1121/1.397556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yost WA, Sheft S. Modulation detection interference: Across-frequency processing and auditory grouping. Hear” Res. 1994;79:48–58. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)90126-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yost WA, Sheft S, Opie J. Modulation interference in detection and discrimination of amplitude modulation. J Acoust” Soc Am. 1989;86:2138–2147. doi: 10.1121/1.398474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]