Summary

Objective

To apply a pendulum technique to detect changes in the coefficient of friction of the articular cartilage of the intact guinea pig tibiofemoral joint after proteolytic disruption.

Design

22 hind limbs were obtained from eleven 3-month old Hartley Guinea pigs. 20 knees were block randomized to one of two treatment groups receiving injections of: 1) α-chymotrypsin (to disrupt the superficial layer of the articular surface) or 2) saline (sham; to control for the effects of the intra-articular injection). The legs were mounted in a pendulum where the knee served as the fulcrum. The decay in pendulum amplitude as a function of oscillation number was first recorded and the coefficient of friction of the joint was determined from these data before injection. 10 μL of either isotonic saline or 1 Unit/μL α-chymotrypsin was then injected into the intra-articular joint space and incubated for two hours. The pendulum test was repeated. Changes in the coefficient of friction between the sham and α-chymotrypsin joints were compared. One additional pair of knees was used for histological study of the effects of the injections.

Results

Treatment with α-chymotrypsin significantly increased the coefficient of friction of the guinea pig knee by 74% while sham treatment decreased it by 8%. Histological sections using Gomori trichrome stain verified that the lamina splendens was damaged following treatment with α-chymotrypsin and not following saline treatment.

Conclusions

Treatment with α-chymotrypsin induces mild cartilage surface damage and increases the coefficient of friction in the Hartley guinea pig knee.

Keywords: Cartilage, friction, tribology, degeneration, biomechanics

Introduction

The lubricating mechanisms of articular cartilage are not well understood. Hydrodynamic lubrication 1-4, boundary lubrication 5-7, elastic deformation 8, and fluid pressurization 9, 10 have all been proposed as mechanisms for decreasing articular surface friction. Since joint velocity and loading conditions vary greatly between the phases in the gait cycle, all of these mechanisms most likely contribute to the low coefficient of friction of articular cartilage.

One challenge in studying joint lubrication is that the sliding surfaces of the articular cartilage are not planar. Cartilage plugs subjected to different loading conditions have enabled investigators to study the surface properties of cartilage, however, these measurements do not consider geometric features or dynamic joint loading of the intact joint. For this reason, pendulum systems have been frequently employed to study dynamic joint friction to understand the mechanisms of joint lubrication 1-4, 11-15.

The changes in the frictional properties of articular cartilage associated with OA are not well understood. The Hartley guinea pig is an animal model in which spontaneous OA progression has been well-documented 16-19. These animals are skeletally mature at three months of age and do not exhibit clinically detectable cartilage degeneration at that time. Based on the natural history of the guinea pig knee, this model could be used to establish the frictional changes that occur with OA progression and provide insight into the role of altered joint lubrication and wear in the development of OA. Of particular interest is the frictional environment of the joint prior to the onset of OA.

Pendulum methods offer a means to assess subtle changes in the coefficient of friction that may occur prior to the development of overt histological abnormalities. It is possible that an acute period of inadequate lubrication may expose the articular cartilage to frictional damage that initiates a cascade of structural or metabolic changes that stimulate cartilage degeneration. Impaired lubricating ability has been observed in synovial fluid samples taken from post-traumatic knee effusions, possibly due to inflammatory destruction of lubricating substances 20. Lubrication deficiency may also be independent of injury, and a source of OA pathogenesis, or a later consequence of cartilage degeneration. A pendulum technique could provide an effective tool for assessing alterations in friction at the articular surface in intact joints that can then be correlated with other established modalities for evaluating joint disease such as histology, biochemical assays, or gross examination 17, 18, 21, 22.

This study examined the effects of brief proteolytic enzyme digestion on the frictional properties of normal articular cartilage in 3 month old Hartley guinea pig knees prior to the onset of OA. Proteolytic disruption was selected to initiate damage to the lamina splendens, a potential precursor to post-traumatic OA 3, 20, 23, 24. Therefore, the objective of this study was to apply a modified Stanton pendulum technique to determine the effects of proteolytic digestion on the coefficient of friction of the tibiofemoral joint articulation of the Hartley guinea pig, ex vivo. The hypotheses were: 1) that the coefficient of friction of the joint will increase when the superficial articular surfaces are degraded with an intra-articular injection of α-chymotrypsin; and 2) that the coefficient of friction will not change with a sham injection of normal saline. The change in the knee flexion amplitude with respect to time (i.e. the decay slope) and the number of oscillations to reach equilibrium were also compared before and after treatment. A histological evaluation of the tibiofemoral articular cartilage in one pair of knees was performed following intra-articular injections of saline or α-chymotrypsin to visualize the damage induced by the two treatments.

Methods

Specimens

After the study received IACUC approval, the hind legs were obtained from eleven 3-month old male Hartley guinea pigs immediately following euthanasia. Each knee was immediately dissected to expose the outer joint capsule and then frozen at −80° C until the day of testing. Ten pairs of limbs were used for the pendulum testing. The additional pair of limbs (not tested in the pendulum) was used for the histological analysis.

Pendulum apparatus

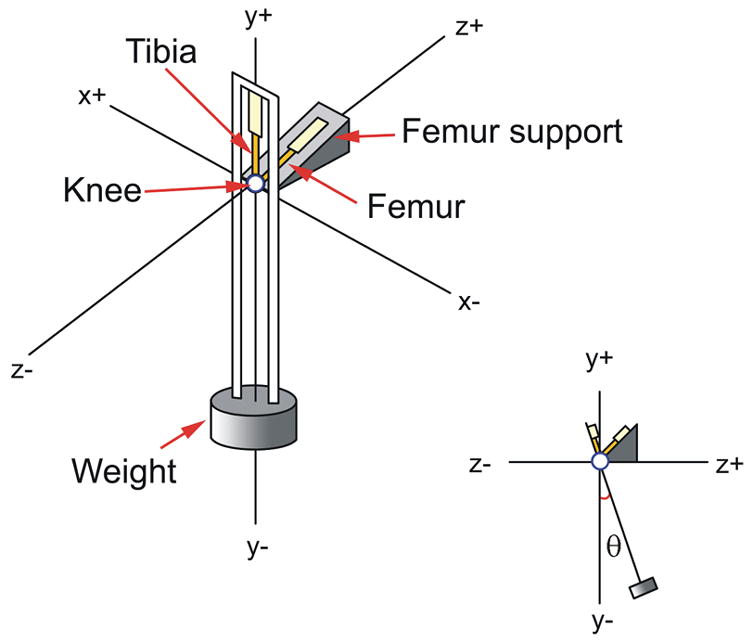

A pendulum was designed to swing the tibia relative to the fixed femur at approximately 1 Hz (actual recorded mean frequency 1.1 Hz) while a compressive load of 300 g (approximately 0.5 times bodyweight) was maintained across the tibiofemoral joint (Figure 1). The motions of the tibiofemoral joint were recorded using the Optotrak System (Northern Digital Inc., Waterloo Ontario). This system measures rigid body motion with 6 degrees of freedom and has an accuracy and resolution of 0.1 mm and 0.1 deg. Three infrared light emitting diodes (LEDs) were rigidly mounted to both the pendulum (tibia) and the base (femur) to document tibiofemoral joint motion. The wire attachments to the LEDs were kept tension-free and out of the sweep of the pendulum by a wire-loop support aligned with the center of rotation of the pendulum (Figure 1). The locations of the LEDs were referenced to an anatomically based coordinate system prior to performing the tests using the Optotrak digitizer 25, 26. Within this coordinate system, the tibia and femur were identified as separate rigid bodies and pendulum motion was described relative to the fixed femur. Pendulum motion was characterized as rotations about the knee: flexion-extension (F-E), internal-external (I-E), and varus-valgus (V-V).

Figure 1.

A schematic of the pendulum apparatus is shown. The guinea pig knee joint served as the fulcrum.

Pendulum Test Protocol

On the day of testing, the legs were thawed at room temperature and the distal tibia and proximal femur were potted in rigid plastic tubes to facilitate mounting in the pendulum. The femur was secured 45° off the horizontal in the fixed femoral support, and the tibia was positioned such that the knee flexion angle was 135° when the pendulum was at rest (equilibrium) (Figure 1). This angle was chosen because it represents the typical weightbearing resting angle of the guinea pig’s knee joint. Motion was initiated by rotating the tibia-pendulum 17° (range 16°-20°) about the FE axis relative to its equilibrium position and releasing it via a gated mechanism.

The coefficient of friction (μ) was calculated using Equation 1:

| (1) |

where Δθpeak was the change in the peak rotation of the pendulum per cycle about the F-E axis (Figure 1), L was the distance between the pendulum center of gravity and the center of the F-E axis (L = 0.22 m), and r was the radius of the femoral condyle (r = 0.002 m; based on measurements from the condyles sectioned for histology testing). This equation for calculating the coefficient of friction has been widely used in studies of articular joints, and it is based upon the assumption that peak rotation amplitude decays linearly with oscillation number 3, 4, 11-13, 27.

The twenty knees were block-randomized (within pairs) to one of two treatment groups: saline injection or α-chymotrypsin injection. Each leg was initially tested in the pendulum (five trials) while data were recorded. Ten μL of either a 1 Unit/μL solution of α-chymotrypsin (Sigma-Aldrich; St Louis, MO; 1 Unit will hydrolyze 1 μmoles of BTEE per minute at ph 7.8 at 25° C) or ten μL of normal saline (sham; to control for the effects of the intra-articular injection) were then injected through the joint capsule into the intra-articular joint space. The knee was incubated at room temperature for two hours. The pendulum test was repeated (5 trials).

Data Analysis

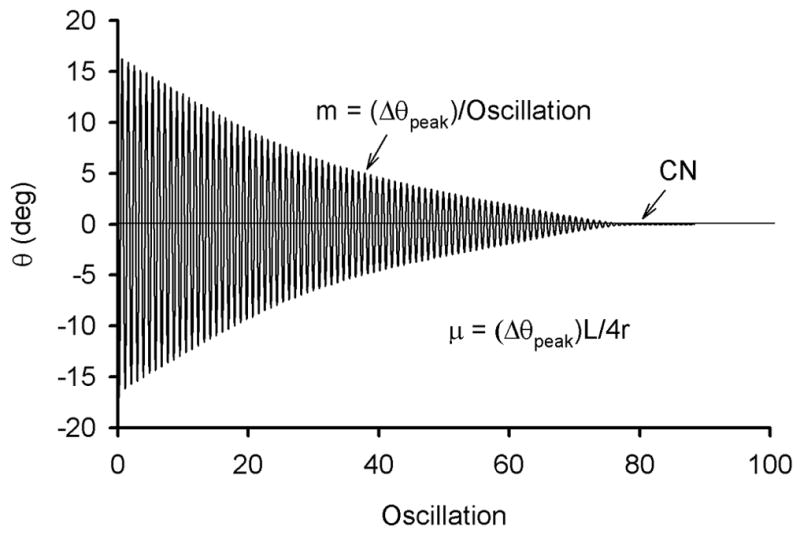

The coefficient of friction, decay slope, and the number of oscillations to reach equilibrium were calculated for each group both pre- and post-treatment. The decay slope (m = Δθpeak/oscillation) was calculated by linear regression on the graph of maximal displacement versus oscillation number for each specimen (Figure 2). The intra-test data (the five trials) were consistent both before and after treatment, so they were averaged within each time point for each specimen. Paired t-tests were used to compare the pre- and post-differences in coefficient of friction, decay slopes, and the number of oscillations to reach equilibrium between the saline- and enzyme-treated knees (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Sample output showing the decay response of the pendulum following the initial 17° rotation about the flexion-extension axis (θpeak) applied to the pendulum.

Histology

One animal was used for histological analysis to evaluate the structural effects of the injections on the articular cartilage. It was euthanized and both hind legs were harvested immediately, dissected to expose the joint capsules and frozen at −80° C. On the day of preparation, the legs were thawed, randomized by coin flip to receive either an intra-articular injection of 10μL of normal saline or 1 Unit/μL α-chymotrypsin, and then incubated for two hours at room temperature. Immediately following incubation, the joints were disarticulated and the soft tissues removed. The distal femur and proximal tibia were amputated and immersed in 10% formalin for a minimum of seventy-two hours.

The specimens were then decalcified in Richman-Gelfand-Hill solution and bisected in the sagittal plane. They were processed in a Tissue-Tek VIP 1000 tissue processor (Model#4617, Miles, Elkhart, IN) and embedded in a single block of Paraplast X-tra (Fisher, Santa Clara, CA) with the bisection surface on the cutting face of the block. Blocks were trimmed to expose tissue using a rotary microtome (Model#2030, Reichart-Jung, Austria). The samples were sectioned 6 microns thick, mounted on slides, and stained with Gomori trichrome 28. Adjacent sections were stained with safranin-O/fast green 29. The slides were viewed and photographed under light microscopy at 60X and 20X, respectively.

The specimens were subjectively compared by two independent examiners for the presence, extent, and depth of surface fragmentations in representative sections of the surfaces of the distal femur and proximal tibia for each treatment condition. The tangential, transitional, and radial layers in articular cartilage and chondrocytes were readily visible in the histological sections 30, 31.

Results

Pendulum analysis

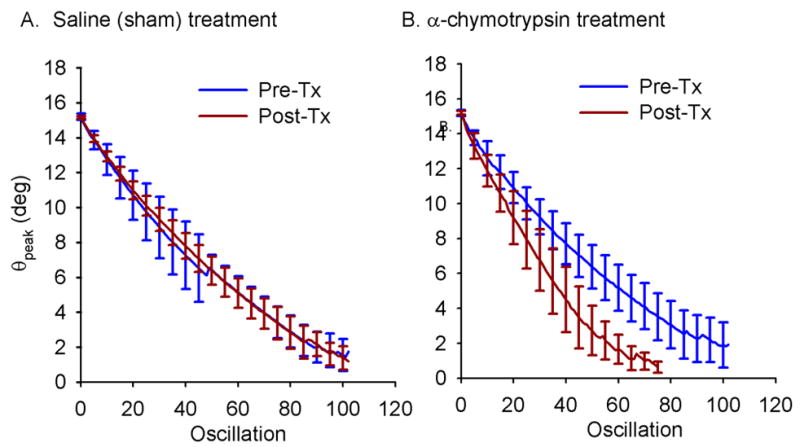

Treatment with α-chymotrypsin significantly increased the μ of the guinea pig knee by 74% while sham treatment decreased it by 8%, on average (p<0.001) (Table 1). The decrease in peak rotation about the F-E axis as a function of oscillation number was nearly linear in both groups before and after treatment (pre-saline mean r2=0.98 (range 0.92-0.99); post-saline mean r2=0.99 (range 0.97-0.99); pre-enzyme mean r2=0.98 (range 0.96-1.0); post-enzyme mean r2=0.98 (range 0.93-1.0)) (Figure 3). The absolute value of the mean decay slope of the maximum angle versus cycle number curve increased (p<0.001), and the number of oscillations to reach equilibrium position, the x-intercept of this curve, decreased with treatment (p<0.001) (Table 1). Although rotations outside the sagittal plane were not intentionally introduced, rotations about the I-E and V-V axes of the tibia were also recorded, though not affected by treatment. In the saline treated limbs, the mean I-E rotations were less than 5° pre-treatment and less than 7° post-treatment, and the mean V-V rotations were less than 5.5° pre-treatment and less than 4° post-treatment. In the enzyme-treated limbs, the mean I-E rotations were less than 10° pre-treatment and less than 9° post-treatment, and the mean V-V rotations were less than 9.5° pre-treatment and less than 5° post-treatment.

Table 1.

The means and standard deviations for the coefficients of friction (μ), the decay slope (m), and the number of oscillations to reach equilibrium (CN) measured before and after treatment with saline or α-chymotrypsin. The mean differences (Pre-Tx minus Post-Tx) between the saline and enzyme treated specimens were significant (p<0.001) for all three parameters. For all groups n=10.

| Parameter | Saline Pre-Tx | Saline Post-Tx | Enzyme Pre-Tx | Enzyme Post-Tx |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| μ × 10−2 | 7.47 (±2.35) | 6.76 (±0.59) | 6.44 (±0.91) | 11.23 (±1.31) |

| m (Δθpeak/oscillation) | 0.16 (±0.05) | 0.14 (±0.01) | 0.13 (±0.02) | 0.23 (±0.03) |

| CN | 95.7 (±19.8) | 100.4 (±8.9) | 103.8 (±17.9) | 61.6 (±9.4) |

Figure 3.

Mean peak F-E rotation angle versus oscillation before and after treatment for the saline (A) and α-chymotrypsin (B) treated knees. The error bars represent ±1 standard deviation.

Light Microscopy

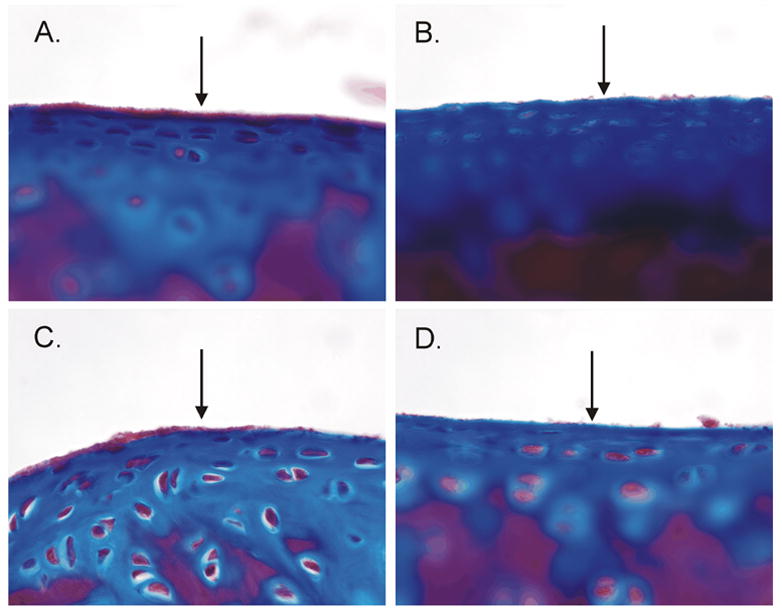

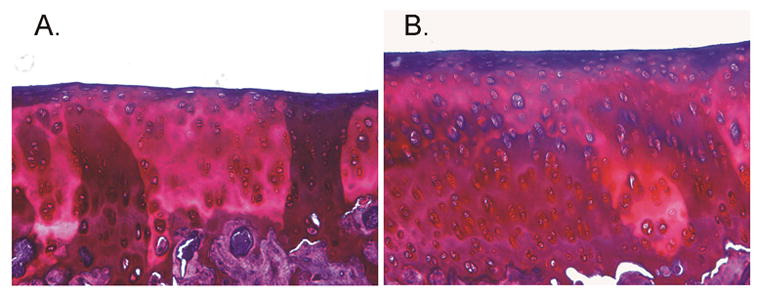

There was no visible damage to the articular cartilage and no evidence of osteoarthritic change in either the saline- or α-chymotrypsin-treated knees. However, thinning and fragmentation of the lamina splendens was observed on Gomori trichrome sections of the distal femur and the proximal tibia of the knee that was injected with α-chymotrypsin (Figures 4b & 4d). No damage to the lamina splendens was observed in the saline control knee (Figures 4a & 4c). Specimens stained with safranin O/fast green showed no differences in proteoglycan content between the two treatment conditions (Figure 5). No damage to the menisci or capsular tissue were noted when the specimens were prepared for histologic evaluation.

Figure 4.

Trichrome staining indicates that the presence of surface damage in the α-chymotrypsin-treated knee but not the saline-treated knee: (A) saline-treated distal femur, (B) enzyme-treated distal femur, (C) saline-treated proximal tibia, (D) enzyme-treated proximal tibia. Note that the lamina splendens is thinner and more fragmented in the sections from the α-chymotrypsin knee.

Figure 5.

Safranin O/Fast Green (tibial cartilage shown here) indicates no difference in proteoglycan content following treatment with either (A) saline or (B) α-chymotrypsin.

Discussion

The results of this study confirm our hypotheses that treatment with α-chymotrypsin increases the coefficient of friction in the Hartley guinea pig knee, while treatment with saline has no significant effect. Treatment with α-chymotrypsin increased the decay slope and decreased the number of oscillations to equilibrium, indicating increased frictional energy loss at the articular surface in the enzyme-treated knee. Saline injection had no statistically significant effects on any of these parameters. The increase in friction in the enzyme-treated knees corresponded to thinning and disruption of sections of the lamina splendens when observed under light microscopy (Gomori trichrome stain). In the saline-treated control knee, the lamina splendens was more continuous and notably thicker. Proteoglycan content was similar in both specimens (safranin O/fast green stain) suggesting no damage to the collagen network entrapping them. This was expected since the intact helical collagen peptides are highly resistant to digestion with α-chymotrypsin because the tertiary structure conceals the enzyme binding site 32, 33. α-chymotrypsin was chosen to digest lubricin and other lamina splendens constituents since this enzyme has been shown to expediently digest lubricating ability in vitro. The mucin domain of lubricin contains no aromatic residues resulting in the digestion of the N- and C-terminii which disable lubricating ability 34. No direct evidence of OA was noted in either specimen. Histologically, there was no loss of proteoglycans, only thinning of the lamina splendens in the treated knee was observed. Nonetheless, damage to the lamina splendens and disruption of its lubricating ability are potential precursors to post-traumatic OA 3, 20, 23, 24.

The observation that increased friction correlated with isolated damage to the lamina splendens is consistent with studies evaluating the lubricating function of this layer and its constituents. Kumar et al found an increase in the coefficient of friction when oscillating osteochondral specimens against glass following digestion of the articular surface with alkaline proteases and confirmed that the digestion had removed the superficial surface layer of the cartilage by atomic force microscopy 7. Lubricin is a mucinous glycoprotein believed to be the boundary lubricant in synovial joints. Lubricin is present in the lamina splendens, within the chondrocytes of the superficial layer, and free in the synovial fluid 23, 24, 35, 36. The friction-reducing function of lubricin is supported by studies showing increased coefficient of friction values for bearings lubricated with synovial fluid following digestions with trypsin 37, 38, chymotrypsin 37, papain 37, and galactosidase 38.

From our data it is not possible to establish the dominant mechanism of joint lubrication when the knee is placed in the pendulum apparatus, however, proteolytic digestion of the boundary lubricant (i.e. lubricin) is a likely candidate 23, 39. The change in swing amplitude as a function of time demonstrated nearly linear decay (Fig. 3), and noted by the near-unity R values. This finding could be consistent with boundary lubrication, in which the frictional energy loss is linear and independent of sliding speed. However, a slight curvilinear component of the curve was also apparent (Fig. 3). The curvilinear component may be due to fluid film lubrication. The relevance of the curvilinear component and how it may change with OA progression remains unknown.

Investigators have utilized the pendulum method to establish the relative contributions of boundary and fluid film lubrication mechanisms by analyzing features of the rotation decay curve under varying conditions of joint load, initial angle, and lubricating substances 1, 2, 15. However, Unsworth concluded that the linear decay does not necessarily imply boundary lubrication, since the exponential term representing the frictional contribution of fluid film mechanics may be small relative to the friction resulting from articular surface contact 14.

Another factor that may explain the curvilinear component in our study is the artifact produced by the intact joint capsule and knee ligaments, which would also cause us to overestimate the coefficient of friction, particularly if a large initial angle of rotation was used. Curvilinear artifact is produced when energy is lost from the system due to the straining of the other capsular structures of the joint 5. We sought to minimize this damping artifact by selecting a range of flexion-extension motion (135 ±17 degrees), which did not approach the terminal limits of flexion or extension. This is particularly important for the knee, since this joint is a roller-slider bearing. In our study, the values for the coefficient of friction (0.064-0.11) were slightly greater than those previously cited by Charnley 5 for cadaver finger, knee, and ankle joints (0.005-0.024), and those found in other recent studies (0.0018-0.016) 3, 4, 11-13, 39. The higher coefficients of friction could be explained by the capsular and ligamentous attachments. Considering that an inverse linear relationship exists between the load supported by the interstitial fluid load and the measured coefficient of friction 9, 10, 40, 41, we felt it was important to retain these structures to help preserve the interaction of the multiple lubrication mechanisms that may be present in the intact joint. While the coefficient of friction values obtained may not represent the absolute values for articular cartilage, the detectable changes that occur following mild proteolytic enzyme treatment are relative to that of the intact joint.

Several methods exist for calculating the coefficient of friction for a bearing at the axis of rotation of a pendulum. We used Stanton’s equation, which is most commonly used in the literature for calculating the coefficient of friction 3, 4, 11-13, 27. Our calculation assumed that aerodynamic drag was negligible relative to the frictional forces; an assumption shared by the previous pendulum studies 3-5, 11-13, 27, 39. The drag caused by the wires attached to the diodes of the Optotrak system for tracking the motion of the pendulum was also assumed to be negligible since steps were taken to relieve any stress on the wires. Aerodynamic drag is another potential source of the slight curvilinear component of the amplitude decay curve. Preliminary testing in our laboratory demonstrated no significant damping effect when the LED technique was compared to a non-contact video method for measuring the swing amplitude, the number of oscillations to reach equilibrium, or the calculated values for the coefficient of friction for the guinea pig knee. We selected the former method since it was the most efficient one for postprocessing.

A 300g load was chosen because this is approximately half the weight of an adult guinea pig and, as such, is within the normal range of load experienced by the joint in vivo. The joint flexion angle of 135° +/− 17 was chosen based on observation of the normal range of motion in live guinea pigs (maximal passive flexion limit was found to be 160°). A potential concern in our system is that the knee joint is constantly compressed by the weight of the pendulum. There is no equivalent to the swing phase of the normal gait when the joint would be unloaded. For this reason, the decay curves observed in this study do not allow us to generalize about changes in the modes of lubrication in the various stages of the gait cycle.

Our assumption that the knee functions as a hinged joint when calculating the coefficient of friction is another simplification. During knee flexion, the femur translates posteriorly and rotates externally relative to the tibial plateau 42, but these movements are small compared to the main flexion-extension arc. The average magnitudes of rotation about the I-E and V-V axes did not change significantly following either treatment condition, which supports the use of the two-dimensional movement of the pendulum in the sagittal plane for our analysis.

We conclude from these data that treatment with α-chymotrypsin disrupts the superficial articular surface and increases the coefficient of friction of the intact Hartley guinea pig tibiofemoral joint ex vivo. Future study will be devoted to understanding the alterations in whole joint coefficient of friction caused by OA progression in vivo.

Acknowledgments

The project was funded by the National Institutes of Health (AR049199; AR047910; AR047910S1; and AR050180) and the RIH Orthopaedic Foundation. The authors acknowledge the assistance of Nigel Gomez in the design of the pendulum, and Gary Badger (University of Vermont) with the statistical analyses.

Footnotes

Supported by: National Institutes of Health (AR049199; AR047910; AR047910S1; and AR050180) and the RIH Orthopaedic Foundation.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jones ES. Joint Lubrication. Lancet. 1934;1:1426–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones ES. Joint Lubrication. Lancet. 1936;1:1043–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawano T, Miura H, Mawatari T, Moro-Oka T, Nakanishi Y, Higaki H, et al. Mechanical effects of the intraarticular administration of high molecular weight hyaluronic acid plus phospholipid on synovial joint lubrication and prevention of articular cartilage degeneration in experimental osteoarthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2003;48:1923–9. doi: 10.1002/art.11172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mori S, Naito M, Moriyama S. Highly viscous sodium hyaluronate and joint lubrication. Int Orthop. 2002;26:116–21. doi: 10.1007/s00264-002-0330-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charnley J. The lubrication of animal joints. Symposium on Biomechanics Institution of Mechanical Engineers. 1959:12–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jay GD, Harris DA, Cha CJ. Boundary lubrication by lubricin is mediated by O-linked beta(1-3)Gal-GalNAc oligosaccharides. Glycoconj J. 2001;18:807–15. doi: 10.1023/a:1021159619373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar P, Oka M, Toguchida J, Kobayashi M, Uchida E, Nakamura T, et al. Role of uppermost superficial surface layer of articular cartilage in the lubrication mechanism of joints. J Anat. 2001;199:241–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2001.19930241.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dowson D, Jin Z-M. Micro-elastohydrodynamic lubrication of synovial joints. Eng Med. 1986;15:63–5. doi: 10.1243/emed_jour_1986_015_019_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krishnan R, Kopacz M, Ateshian GA. Experimental verification of the role of interstitial fluid pressurization in cartilage lubrication. J Orthop Res. 2004;22:565–70. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishnan R, Park S, Eckstein F, Ateshian GA. Inhomogeneous cartilage properties enhance superficial interstitial fluid support and frictional properties, but do not provide a homogeneous state of stress. J Biomech Eng. 2003;125:569–77. doi: 10.1115/1.1610018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanaka E, Kawai N, Tanaka M, Todoh M, van Eijden T, Hanaoka K, et al. The frictional coefficient of the temporomandibular joint and its dependency on the magnitude and duration of joint loading. J Dent Res. 2004;83:404–7. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawai N, Tanaka E, Takata T, Miyauchi M, Tanaka M, Todoh M, et al. Influence of additive hyaluronic acid on the lubricating ability in the temporomandibular joint. J Biomed Mater Res. 2004;70A:149–53. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanaka E, Tatsunori I, Dalla-Bona DA, Kawai N, van Eijden T, Tanaka M, et al. The effect of experimental cartilage damage and impairment and restoration of synovial lubrication on friction in the temporomandibular joint. J Orofac Pain. 2005;19:331–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Unsworth A, Dowson D, Wright V. The Frictional Behavior of Synovial Joints - Part 1: Natural Joints. Journal of Lubrication Technology. 1975:369–76. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Linn FC. Lubrication of Animal Joints II: The Mechanism. J Biomech. 1968;1:193–205. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(68)90004-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bendele AM, Hulman JF. Spontaneous cartilage degeneration in guinea pigs. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:561–5. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bendele AM, White SL, Hulman JF. Osteoarthrosis in guinea pigs: histopathologic and scanning electron microscopic features. Lab Anim Sci. 1989;39:115–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jimenez PA, Glasson SS, Trubetskoy OV, Haimes HB. Spontaneous osteoarthritis in Dunkin Hartley guinea pigs: histologic, radiologic, and biochemical changes. Lab Anim Sci. 1997;47:598–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jimenez PA, Harlan PM, Chavarria AE, Haimes HB. Induction of osteoarthritis in guinea pigs by transection of the anterior cruciate ligament: radiographic and histopathological changes. Inflamm Res. 1995;44:s129–30. doi: 10.1007/BF01778296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jay GD, Elsaid KA, Zack J, Robinson K, Trespalacios F, Cha CJ, et al. Lubricating ability of aspirated synovial fluid from emergency department patients with knee joint synovitis. J Rheumatol. 2004;31:557–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mankin HJ, Johnson ME, Lippiello L. Biochemical and metabolic abnormalities in articular cartilage from osteoarthritic human hips. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1970;63:131–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Sluijs JA, Geesink RGT, van der linden AJ, Bulstra SK, Kuyer R, Drukker J. The reliability of the Mankin score for osteoarthritis. J Orthop Res. 1992;10:59–61. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100100107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rhee DK, Marcelino J, Baker M, Gong Y, Smits P, Lefebvre V, et al. The secreted glycoprotein lubricin protects cartilage surfaces and inhibits synovial cell overgrowth. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:622–31. doi: 10.1172/JCI200522263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidt TA, Schumacher BL, Klein TJ, Voegtline MS, Sah RL. Synthesis of proteoglycan 4 by chondrocyte subpopulations in cartilage explants, monolayer cultures, and resurfaced cartilage cultures. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2004;50:2849–57. doi: 10.1002/art.20480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Churchill DL, Incavo SJ, Johnson CC, Beynnon BD. The transepicondylar axis approximates the optimal flexion axis of the knee. Clin Orthop. 1998;356:111–8. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199811000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grood ES, Suntay WJ. A joint coordinate system for the clinical description of three dimensional motions: Application to the knee. J Biomech Eng. 1983;105:136–44. doi: 10.1115/1.3138397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stanton TE. Boundary Lubrication in Engineering Practice. Engineer. 1923;135:678–80. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheehan DC, Hrapchak BB. Theory and Practice of Histotechnology. Columbus: Batelle Press; 1980. pp. 191–2. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenberg L. Chemical basis for the histological use of safranin O in the study of articular cartilage. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1971;53:69–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamamoto K, Shishido T, Masaoka T, Imakiire A. Morphological studies on the ageing and osteoarthritis of the articular cartilage in C57 black mice. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery. 2005;13:8–18. doi: 10.1177/230949900501300103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eyre DR. Collagens and cartilage matrix homeostasis. Clinical Orthopaedics & Related Research. 2004;427:S118–S22. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000144855.48640.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ryhanen L, Rantala-Ryhanen S, Tan EML, Uitto J. Assay of collagenase activity by a rapid, sensitive, and specific method. Collagen Related Research. 1982;2:117–30. doi: 10.1016/s0174-173x(82)80028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hollander AP, Heathfield TF, Webber C, Iwata Y, Bourne R, Rorabeck C, et al. Increased damage to type II collagen in osteoarthritic articular cartilage detected by a new immunoassay. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:1722–32. doi: 10.1172/JCI117156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jay GD, Tantravahi U, Britt D, Barrach HJ, Cha CJ. Homology of lubricin and superficial zone protein (SZP): Products of megakaryocyte stimulating factor (MSF) gene expression by human synovial fibroblasts and articular chondrocytes localized to chromosome 1q25. J Orthop Res. 2001;19:9–19. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(00)00040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schumacher BL, Block JA, Schmid TM, Aydelotte MB, Kuettner KE. A novel proteoglycan synthesized and secreted by chondrocytes of the superficial zone of articular cartilage. Archives of Biochemistry & Biophysics. 1994;311:142–52. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schumacher BL, Hughes CE, Kuettner KE, Caterson B, Aydelotte MB. Immunodetection and partial cDNA sequence of the proteoglycan, superficial zone protein, synthesized by cells lining synovial joints. J Orthop Res. 1999;17:110–20. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100170117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wilkins J. Proteolytic destruction of synovial boundary lubrication. Nature. 1968;219:1050–1. doi: 10.1038/2191050a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jay GD, Cha CJ. The effect of phospholipase digestion upon the boundary lubricating ability of synovial fluid. J Rheumatol. 1999;26:2454–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jay GD, Carpten JD, Rhee DK, Torres JR, Marcelino J, Warman ML. Analysis of the frictional characteristics of CACP knockout mice joints with the modified stanton pendulum technique. Transactions of the Orthopaedic Research Society. 2003;28:0136. [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCutcheon CW. The frictional properties of animal joints. Wear. 1962;5:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Forster H, Fisher J. The influence of loading time and lubricant on the friction of articular cartilage. Eng Med. 1996;210:109–19. doi: 10.1243/PIME_PROC_1996_210_399_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williams A, Logan M. Understanding tibio-femoral motion. Knee. 2004;11:81–8. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]