Abstract

Lysophosphatidic acids (LPA) exert multiple biological effects through specific G protein-coupled receptors. The LPA-activated receptor subtype LPA2 contains a carboxyl-terminal motif that allows interaction with PDZ domain-containing proteins, such as NHERF2 and PDZ-RhoGEF. To identify additional interacting partners of LPA2, the LPA2 carboxyl-terminus was used to screen a proteomic array of PDZ domains. In addition to the previously identified NHERF2, several additional LPA2-interacting PDZ domains were found. These included MAGI-2, MAGI-3 and neurabin. In the present work, we demonstrate the specific interaction between LPA2 and MAGI-3, and the effects of MAGI-3 in colon cancer cells using SW480 as a cell model. MAGI-3 specifically bound to LPA2, but not to LPA1 and LPA3. This interaction was mediated via the fifth PDZ domain of MAGI-3 interacting with the carboxyl-terminal 4 amino acids of LPA2, and mutational alteration of the carboxyl-terminal sequences of LPA2 severely attenuated its ability to bind MAGI-3. LPA2 also associated with MAGI-3 in cells as determined by co-affinity purification. Overexpression of MAGI-3 in SW480 cells showed no apparent effect on LPA-induced activation of Erk and Akt. In contrast, silencing of MAGI-3 expression by siRNA drastically inhibited LPA-induced Erk activation, suggesting that the lack of an effect by overexpression was due to the high endogenous MAGI-3 level in these cells. Previous studies have shown that the cellular signaling elicited by LPA results in activation of the small GTPase RhoA by Gα12/13 — as well as Gαq-dependent pathways. Overexpression of MAGI-3 stimulated LPA-induced RhoA activation, whereas silencing of MAGI-3 by siRNA resulted in a small but statistically significant decrease in RhoA activation. These results demonstrate that MAGI-3 interacts directly with LPA2 and regulates the ability of LPA2 to activate Erk and RhoA.

Keywords: Lysophosphatidic acids, PDZ, MAGI-3, Receptor

1. Introduction

Lysophosphatidic acids (LPA) exert growth factor-like effects such as proliferation, apoptosis, contraction, migration, and aggregation of platelets [1-4]. Signaling by LPA is primarily mediated through LPA1, LPA2 and LPA3, which are members of a family of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). LPA1, LPA2, and LPA3 are highly homologous with more than 50% identity [5-7]. Recently, an orphan receptor P2Y9/GPR23 has been identified as the fourth LPA receptor [8]. P2Y9/GPR23, despite sharing only 20–24% amino acid identity with the other LPA receptors, mediates adenylate cyclase stimulation and intracellular Ca2+ mobilization in response to LPA. All the LPA receptors can couple to three distinct families of heterotrimeric GTP binding proteins, including Gq/11, Gi/0, and G12/13 [3,9]. The best known pathway triggered by LPA is the activation of phospholipase C (PLC) with subsequent phosphatidylinositol-(4,5)-biphosphate hydrolysis and Ca2+ mobilization. This pathway involves a pertussis toxin (PTX)-insensitive Gq/11-mediated mechanism as well as a PTX-sensitive Gi/o-mediated mechanism depending on cell types. This classical Gαq-PLC-Ca2+ cascade can also mediate mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activation. We have previously shown that LPA-induced activation of extracellular signal regulated kinase 1 and 2 (Erk1/2) in human colon cancer cells was completely blocked by the PLCβ inhibitor, U73122 [10]. In contrast, the activation of the PI3K–Akt pathway was PTX-sensitive, suggesting a Gi-mediated mechanism is involved. It is also evident that LPA receptors couple to G12/13 to activate the small GTPase RhoA that mediates the remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton [11,12]. Recent studies have shown that the activation of RhoA is mediated by RhoGEFs that serve as effectors of activated G12/13 and a molecular bridge between the G-proteins and RhoA [11].

The formation of protein complexes is the basis for efficient propagation in many cellular signaling processes. In this regard, the PDZ domain has emerged as a major mediator of protein sequestration in the plasma membrane. The PDZ domain was identified as a common element present in PSD-95, the Drosophila disc-large tumor suppressor protein DlgA and the tight-junction protein ZO-1. The PDZ domain is made up of ~90 amino acid residues that preferentially bind to distinct peptide sequences located at the carboxyl-terminus (CT) of interacting proteins [13,14]. Class I PDZ domains preferentially bind to the CT motifS/T-x-Φ, where Φ represents a hydrophobic amino acid [15]. Many receptors possess Class I PDZ binding motifs at their carboxyl-termini. These include the β2-adrenergic receptor (β2-AR), P2Y1 receptor, and N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, to name a few [16-18]. PDZ interaction can regulate receptor-mediated signaling, the recycling and trafficking of receptors, and assembly of receptors with other proteins at the plasma membrane.

LPA1 and LPA2 possess Class I carboxyl-terminal motifs that allow interaction with PDZ domain-containing proteins. We and others have reported that LPA2, but not LPA1, binds specifically to the Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor 2 (NHERF2; also known as E3KARP) [10,19]. NHERF2 links LPA2 to PLC-β3 and, hence, affects the activation of downstream targets, such as Erk and cyclooxygenase-2 [19]. In addition, it has been shown that PTX-sensitive activation of Akt is drastically down-regulated by knockdown of NHERF2 expression [10]. In contrast to the LPA2-specific association with NHERF2, both LPA1 and LPA2 bind to PDZ domain-containing RhoGEFs and regulate LPA-induced RhoA activation via G12/13 [11,20]. However, because of the abundance of PDZ domains (~440 PDZ domains in the human genome [15]), it is likely that there are additional PDZ scaffolds that can associate with LPA2 and LPA1, and thus there is a clear physiological need to identify these PDZ scaffolds. In this study, we have used a newly developed PDZ proteomic array to identify additional PDZ proteins that interact with LPA2 [17,21]. We identified several novel interactions, and examined in detail the association between LPA2 and the membrane-associated guanylate kinase-like protein with an inverted domain structure-3 (MAGI-3).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals and plasmid constructs

1-Oleoyl-2-Hydroxy-sn-Glycero-3-Phosphatidic acid was obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids and prepared in PBS containing 0.1% BSA (v/v). The LPA2-selective agonist, fatty alcohol phosphate (FAP-12) [22], was purchased from BIOMOL. Monoclonal anti-V5 was from Covance, and polyclonal anti-MAGI-3 antibody was obtained from BD Biosciences. Anti-LPA2 against the N-terminus was purchased from Exalpha Biologicals, Inc. All other antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling.

The carboxyl-terminal (CT) 56, 44, and 43 amino acids of LPA1, LPA2, and LPA3, respectively, were cloned into pGEX-4T to generate GST fusion proteins. Full-length MAGI-3 in pcDNA3.1/V5–His was kindly provided by Rich Laura (Genetech). The individual PDZ domains of MAGI-3 (PDZ1: 429–579, PDZ2: 597–742, PDZ3: 745–873, PDZ4: 874–1022, PDZ5: 1040–1151) were cloned into pET30A as previously described [17].

2.2. PDZ array and in vitro overlay assay

PDZ domains expressed as His- and S-tagged fusion proteins spotted on gridded nylon membranes were previously described [17,21]. The membranes were blocked in blot buffer (10 mM Hepes, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 2% dry milk, 0.1% Tween 20) for 30 min at room temperature, then overlaid with 100 nM GST-LPA2 fusion proteins in blot buffer for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were washed three times in blot buffer, and incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-GST antibody to detect GST fusion protein overlaid on His-PDZ fusion proteins using the ECL kit (Pierce Biotech).

The carboxyl-terminal (CT) 56, 44, and 43 amino acids of LPA1, LPA2, and LPA3, respectively, were cloned into pGEX-4T to generate GST fusion proteins. His- and S-tagged PDZ domains of MAGI-3 were run on 15% SDS-PAGE gels, blotted and overlaid with 50 nM GST-LPA1, GST-LPA2, GST-LPA3, or GST in blot buffer for overnight at 4 °C. The blots were washed three times in the same buffer and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with anti-GST antibody, followed by horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibody to detect GST fusion protein overlaid on His-PDZ fusion proteins.

The DSTL motif at the CT of GST-LPA2 was sequentially mutated to Ala by PCR. GST fusion proteins were expressed, separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred onto nylon membranes. The membrane was blocked and overlaid with 50 nM His- and S-tagged PDZ5 of MAGI-3 as described earlier. The membranes were washed three times in blot buffer, and incubated with HRP-conjugated S protein (Novagen) to detect the PDZ5 protein overlaid on GST fusion proteins.

2.3. Cell culture, transfection and RNA preparation

SW480 cells obtained from the American Tissue Culture Collection were grown in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 100 U/ml penicillin at 37 °C in 95% air/5% CO2 atmosphere as previously described [23]. Transfection was performed using Lipofectamine2000 as recommended by the manufacturer (Invitrogen). When appropriate, cells were selected with 800 μg/ml G418.

siRNA targeting human MAGI-3 was purchased from Invitrogen. SW480 cells seeded at 50% confluence on 60 mm culture plates were transfected with 20 nM siRNA using Lipofectamine2000. As control, a scrambled 21 nt RNA duplex also purchased from Invitrogen was used. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were serum deprived overnight and next morning treated with LPA or carrier. The efficacy of gene silencing was determined by Western immunoblot using an anti-MAGI-3 antibody.

Total RNA was prepared from cells by using TRIzol (Invitrogen), followed by reverse transcription to generate cDNA using the First Strand Synthesis kit (Invitrogen). The primer pairs specific for LPA1–3 and β-actin, and the conditions for semi-quantitative amplification have been previously described [10].

2.4. Western immunoblot and in vivo interaction

Cells were rinsed three times with ice-cold PBS buffer, and lysed by sonication in lysis buffer composed of 50 mM Tris–Cl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM PMSF, 1 mM Na orthovanadate, 10 mM Na fluoride, 10 mM Na pyrophosphate, 25 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1% Triton X-100, and protease inhibitors (one complete Mini EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail tablet per 10 mL; Roche Applied Science). The lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 14,000 g at 4 °C for 10 min. Protein concentration was determined by the Bicinchoninic Acid assay (Sigma). The equal amount of lysate in 2× Laemmli sample buffer was resolved by 6% SDS-PAGE, and Western immunoblot analysis was performed as previously described [10]. To determine the activation of Erk, serum starved cells were activated with 10 μM LPA and lysates were prepared as described above. The levels of activated Erk were determined using an anti-phospho-Erk antibody (1:1000; Cell Signaling). The filters were stripped and reprobed with an anti-Erk antibody to analyze total protein levels. The levels of phosphor-Erk were normalized to total Erk by densitometric analysis. Activation of Akt was determined by a similar approach.

SW480/MAGI-3 or SW480/pcDNA cells were treated with 10 μM LPA or a carrier for 10 min cells were washed twice in ice-cold PBS and lysed in lysis buffer. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation and one milligram of lysate was incubated with 60 μl Ni-NTA beads (1:1 mix) (Qiagen) for 1 h at 4 °C with constant head-over-tail rotation. The resins were washed three times with lysis buffer and the bound proteins were eluted from the resins by boiling for 5 min in 2× Laemmli sample buffer. Western blot was performed as described above.

Densitometric analyses were performed on the Typhoon phosphoimager (Amersham) using the Image Quant program. Statistical significance was assessed by one-way ANOVA using Origin software. Data are presented as the means±standard deviation (SD).

2.5. RhoA activation assay

Activation of RhoA was determined by a modified method described by Ren and Schwartz [24]. Cells were seeded on 60-mm culture dishes. When gene silencing by siRNA was needed, cells were prepared and transfected as described earlier. After serum starvation for 24 h, cells were activated with LPA and lysed in ice-cold lysis/binding buffer (25 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1% NP-40, 1 mM DTT, 10% glycerol, and protease inhibitors). Three hundred micrograms of lysate was incubated for 1 h with glutathione-sepharose beads (Amersham) coupled with the Rho-binding domain of rhotekin (GST-RBD). The construct to express GST-RBD was kindly provided by Dr. Martin Schwarts (Univ. of Va). Beads were washed three times with lysis/binding buffer, and the bound RhoA proteins were eluted with Laemmli sample buffer and subjected to Western blot using an anti-RhoA antibody.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of PDZ proteins interacting with LPA2

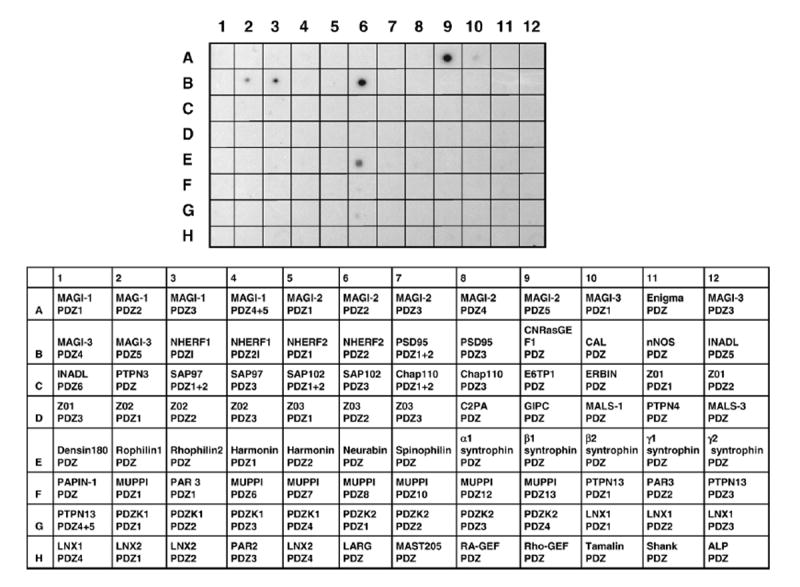

Previous studies have shown that LPA2 interacts with two PDZ proteins, NHERF2 and PDZ-rhoGEF [10,19,20]. To further identify PDZ domains that interact with LPA2, we screened a PDZ domain proteomic array that contains 96 distinct PDZ domains expressed and purified as His-tagged proteins [17]. This blot was overlaid with GST fusion proteins corresponding to LPA2 CT. Fig. 1 shows that GST-LPA2 interacted with several of the PDZ domains on the array. These included MAGI-2/PDZ5, NHERF1/PDZ1, NHERF2/PDZ2, MAGI-3/PDZ5, and neurabin [25,26]. The strongest signals were observed with NHERF2/PDZ2 and MAGI-2/PDZ5. The binding of the CT of LPA2 to NHERF2/PDZ2 has previously been demonstrated [10,19]. As previously been shown [17], GST itself did not bind to the PDZ domains. MAGI-3 is widely expressed in multiple tissues including brain, heart, and colon, whereas MAGI-2 and neurabin are preferentially expressed in the brain [27-29]. Because of our interest in the role of LPA2 in gastrointestinal physiology, we characterized the interaction between LPA2 and MAGI-3 in further detail.

Fig. 1. A proteomic analysis to identify LPA2 binding PDZ domains.

The CT of LPA2 fused to GST was overlaid onto a proteomic array containing 96 distinct Class I PDZ domains. GST-LPA2 showed specific binding to several PDZ domains, including MAGI-2/PDZ5 (A9), MAGI-3/PDZ5 (B2), NHERF1/PDZ1 (B3), NHERF2/PDZ2 (B6), and neurabin (E6). Representative data from 3 separate experiments are shown. The list of the PDZ domains spotted on the membrane is shown on the bottom. A detailed description of the PDZ domains has previously been published [21].

3.2. Specificity of the LPA2 interaction with MAGI-3/PDZ3

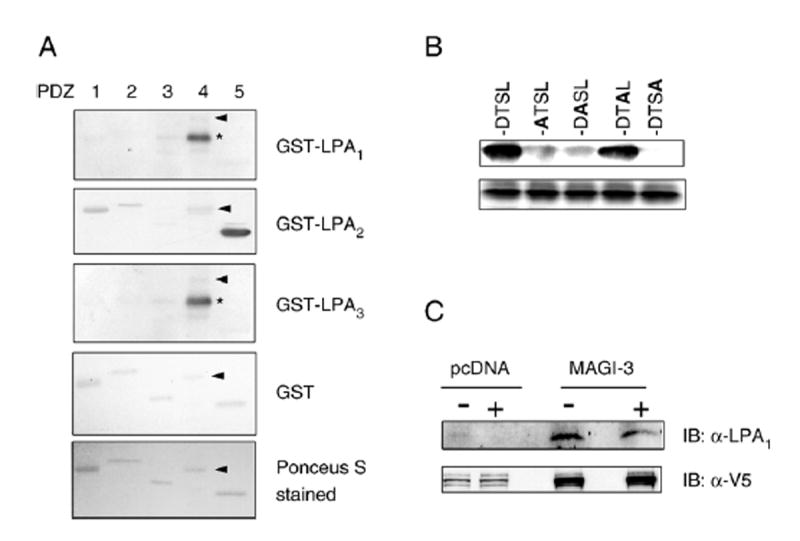

LPA1 and LPA2 have CT motifs of -HSVV and -DSTL, respectively, that are likely to interact with PDZ domains. In contrast, LPA3 has the CT motif -KSTS. To confirm that the specificity of the interaction with MAGI-3, we performed in vitro overlay assays. Individual PDZ domain of MAGI-3 expressed as His- and S-tagged fusion proteins were overlaid with GST-LPA1, GST-LPA2, GST-LPA3, or GST as shown in Fig. 2A. Overlay studies revealed that GST-LPA2 robustly bound to PDZ5 of MAGI-3. In contrast, GST-LPA1, GST-LPA3 or GST showed no interaction with any of the PDZ domains of MAGI-3. Please note that the bands labeled with asterisks on the blots overlaid with LPA1 and LPA3 are not the PDZ4 domain, but a contaminating E. coli protein that was present in the preparation of MAGI-3/PDZ4. For an unknown reason, GST-LPA1 and GST-LPA3, or proteolytic byproducts of the GST fusion proteins repeatedly bound to this product, which migrated as a smaller molecular mass (asterisk) than that of MAGI-3/PDZ4 (arrowhead).

Fig. 2. LPA2 specifically binds to MAGI-3.

A. GST fusion constructs of LPA1–3 CT were overlaid onto membranes containing the individual PDZ domains of MAGI-3. LPA2, but not LPA1 or LPA3, bound to the PDZ5 domain of MAGI-3. The bottom panel shows a representative Ponceau-S stained transfer membrane containing purified PDZ domains. Asterisk (*) indicates a contaminating E. coli protein. Arrow heads point to the location of PDZ4. B. Structural determinants of the LPA2–MAGI-3 interaction. The last four amino acids (DTSL) of LPA2 CT were sequentially mutated to Ala. Substituted Ala residues are highlighted in bold. Wild-type and mutated LPA2 CT were expressed as GST fusion proteins (3 μg), loaded onto SDS-PAGE gels, transferred, and overlaid with His- and S-tagged PDZ5 of MAGI-3. All data are representative of four independent experiments. The bottom panel shows a representative Coomasie-stained gel showing equal loading of the GST fusion proteins. C. Co-affinity purification of MAGI-3 and LPA2 from SW480 cells. SW480 transfected with V5/His-MAGI-3 or pcDNA3.1–V5/His were treated with 10 μM LPA or carrier for 10 min. V5/His-MAGI-3 was affinity purified and the presence of co-purified LPA2 was detected by Western blot. Bottom panel shows Western blot using an anti-V5 antibody indicating the presence of affinity-purified V5/His-MAGI-3 in SW480/MAGI-3 cells. Representative data from four independent experiments are shown.

The above results showed that LPA1, despite having a Class I PDZ-binding motif, is unable to bind to MAGI-3. To further analyze the specificity of the interaction between LPA2 and MAGI-3/PDZ5, the amino acids comprising the DSTL motif of LPA2 were sequentially mutated to Ala. Fig. 2B shows a robust association between MAGI-3/PDZ5 and GST-DSTL, consistent with the data shown in Fig. 1. However, this association between LPA2 and MAGI-3 was completely abolished by the replacement of the terminal Leu, suggesting that the Leu is essential. Mutation of Asp at −3 or Ser at −2 did not completely abolish, but drastically inhibited the binding of MAGI-3/PDZ5, suggesting that these amino acid residues are important, but not obligatory. In contrast, the replacement at the −1 did not affect the binding to MAGI-3/PDZ3.

To corroborate the results of the in vitro studies on LPA2 and MAGI-3, we next tested the association between MAGI-3 and LPA2 in living cells. SW480 cells transfected with V5/His-MAGI-3 or pcDNA3.1/V5–His were treated with 10 μM LPA or carrier for 10 min. Exogenous V5/His-MAGI-3 was affinity-purified using Ni-NTA resins and the presence of co-purified LPA2 was determined by Western blot (Fig. 2C). The results showed that LPA2 co-purified from lysates of SW480 cells transfected with MAGI-3, but not pcDNA. In addition, treatment with LPA did not affect the amount of LPA2 co-purified, suggesting that the LPA2–MAGI-3 association was not regulated by LPA but appeared to occur constitutively.

3.3. MAGI-3 potentiates LPA-induced activation of Erk, but not Akt

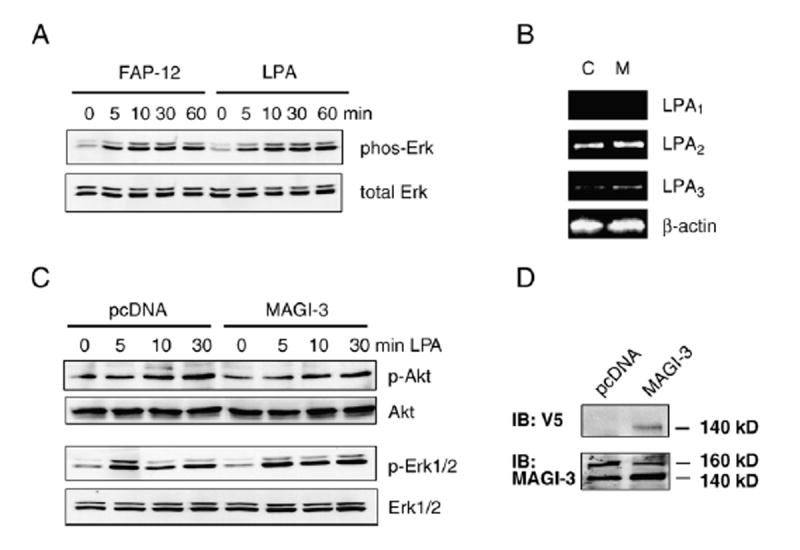

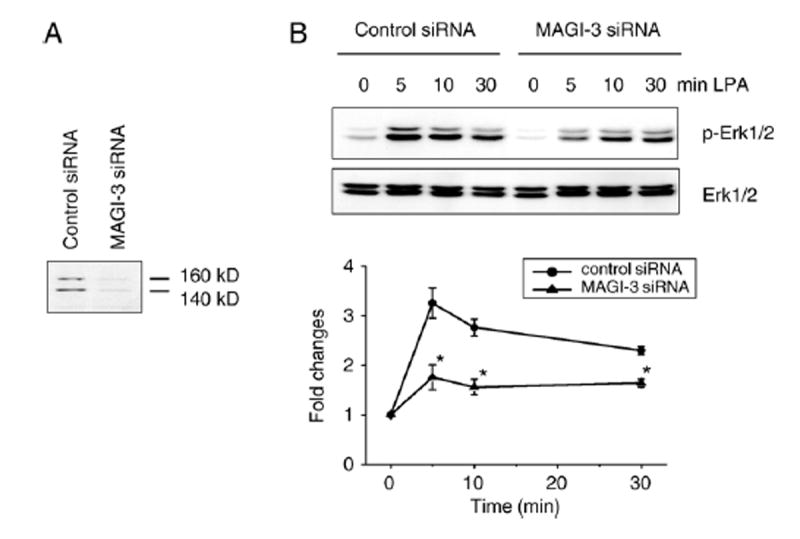

We have previously shown that SW480 and several other human colon cancer cell lines predominantly express LPA2 (Fig. 3B) [10]. To confirm that LPA2 is the major LPA receptor in SW480 cells, we stimulated the cells with LPA or FAP-12. FAP-12 is a specific agonist of LPA2, yet a selective antagonist of LPA3 and LPA1 [22]. As shown in Fig. 3A, the magnitude and time-course of Erk activation by LPA and FAP-12 were identical, suggesting that LPA-induced signaling is primarily elicited by LPA2. To address a potential role of MAGI-3 in LPA- induced signaling in colon cancer cells, we used SW480 cells stably transfected with V5/His-MAGI-3 or pcDNA as control. Overexpression of MAGI-3 did not alter the expression levels of LPA receptors (Fig. 3B). Induction of LPA2 activates several downstream targets, including Erk and Akt. However, over-expression of MAGI-3 did not affect the amplitude or time-course of Akt activation (Fig. 3C). Similarly, LPA-mediated Erk activation was not altered significantly by overexpression of MAGI-3. We contemplated that the lack of effect might be due to a limited increase in the total amount of MAGI-3 protein over the endogenous level. MAGI-3 protein migrates as a 140 kDa band with a minor band at 170 kDa, and V5-tagged MAGI-3 migrated at 140 kDa (Fig. 3D) [30]. A comparison of total MAGI-3 protein in the transfected cells using an anti-MAGI-3 antibody revealed that the heterologous expression of MAGI-3 only modestly increased (~25%) the total amount of MAGI-3 (Fig. 3D). To circumvent this limitation, we employed siRNA to silence MAGI-3 expression in SW480 cells. Transient transfection of SW480 cells with siRNA targeting MAGI-3 resulted in an approximately 80% decrease in the amount MAGI-3 proteins, as determined by Western blot (Fig. 4A). Subsequent determination of Erk activation (Fig. 4B) revealed that knockdown of MAGI-3 significantly decreased LPA-induced activation of Erk. In contrast, knockdown of MAGI-3 had no effect on Akt activation (data not shown).

Fig. 3. LPA-induced activation of Akt and Erk.

A. SW480 cells were activated by 10 μM LPA or 10 μM FAP-12. Activation of Erk was determined by Western blot using an anti-phospho-Erk antibody as described under Materials and methods. B. RT-PCR was performed on RNA prepared from SW480 cells stably transfected with pcDNA3.1/V5–His (C) or V5/His-MAGI-3 (M). C. SW480/pcDNA and SW480/MAGI-3 cells were treated with LPA, and the amounts of activated Akt and Erk were determined using anti-phospho-Akt and anti-phospho-Erk antibodies, respectively. Anti-Akt or anti-Erk antibodies were used to determine total Akt and Erk, respectively. Results are representative of five independent experiments. D. The expression levels of exogenous V5/His-MAGI-3 were determined by Western blot using an anti-V5 antibody. An anti-MAGI-3 antibody was used to compare total MAGI-3 proteins in V5/His-MAGI-3 and control transfected cells.

Fig. 4. Knockdown of MAGI-3 significantly affects LPA-induced activation of Erk.

A. The expression level of MAGI-3 in MAGI-3 siRNA treated cells was decreased to 18±4% of control siRNA treated cells. B. Time-course of LPA-induced activation of Erk in MAGI-3 siRNA and control siRNA treated cells were determined as described under Materials and methods. Representative data from four independent experiments are shown. The amount of phospho-Erk was quantified and was presented as fold-changes over the amount of phospho-Erk in untreated cells. The bars and error bars represent means±SD. *indicates p<0.01 relative to the control transfected cells.

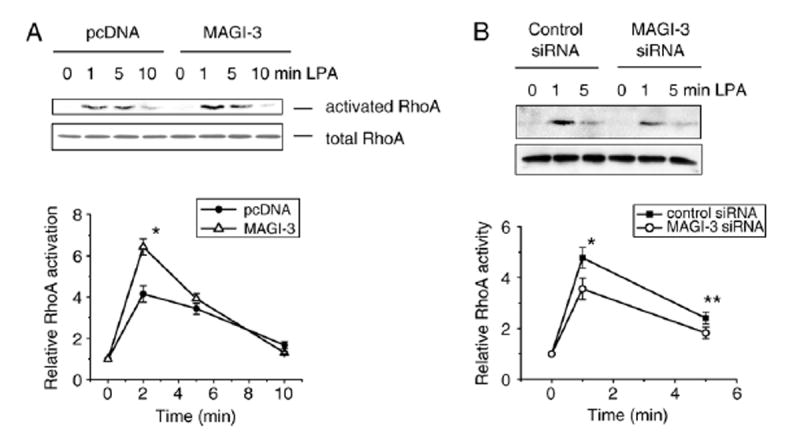

3.4. MAGI-3 facilitates LPA-induced RhoA activation

LPA receptors couple with Gα12/13 to activate the small GTPase RhoA [31]. To examine whether MAGI-3 regulates RhoA activation by LPA, we determined RhoA activation by using the GST-Rho binding domain of Rhotekin (GST-RBD) in SW480/pcDNA and SW480/MAGI-3 cells. LPA rapidly activated RhoA in control transfected cells, reaching maximum activity at 1–2 min. A similar activation of RhoA was observed in MAGI-3 overexpressing cells (Fig. 5A). Quantification showed that the activation of RhoA in SW480/MAGI-3 cells was more robust (31%) compared with control transfected cells. Conversely, knockdown of MAGI-3 decreased LPA-induced activation of RhoA (15%) compared with control siRNA treated cells (Fig. 5B). However, the extent of the reduction in RhoA activation by MAGI-3 knockdown was smaller compared to the effect on Erk activation by overexpression.

Fig. 5. Effects of MAGI-3 on LPA-induced RhoA activation.

A. SW480 cells transfected with V5/His-MAGI-3 or pcDNAwere treated with LPA, and the lysates (300 μg) were incubated with GST-rhotekin RhoA binding domain (GST-RBD). The bound activated RhoAwas resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred, and blotted using an anti-RhoA antibody to determine the extent of RhoA activation. Total RhoAwas determined using lysates. Data are means±SD of four independent experiments. * indicates p<0.01 compared with control siRNA treated cells. B. The activation of RhoA in cells treated with MAGI-3 siRNA or control siRNA was determined. *, ** indicate p<0.01 and p<0.10, respectively, compared with control transfected cells.

4. Discussion

Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) is a mediator of multiple cellular responses. LPA mediates its effects predominantly through the G protein-couple receptors, LPA1, LPA2, and LPA3. Recent studies have shown that scaffold proteins, such as NHERF2 and TRIP6, play a pivotal role in LPA-induced signaling [10,19,32]. LPA2 has a canonical PDZ binding motif, -DSTL, at its carboxyl-terminus. Thus far, three PDZ-containing proteins, NHERF2, PDZ-RhoGEF, and leukemia- associated RhoGEF (LARG), have been shown to bind to the carboxyl-terminus of LPA2 [10,11,19,20]. These proteins have been identified by testing the associations with LPA2 under an assumption that LPA2 may interact with their PDZ domains. To further identify additional PDZ proteins that may interact with LPA2, we employed a proteomic approach. The PDZ proteomic arrays have previously been used by us in the identification of PDZ proteins interacting with GPCRs such as P2Y1 and β-ARs [17,21]. Using the PDZ arrays containing 96 individual PDZ domains, we found that LPA2 binds to several PDZ scaffolds, including NHERF2 and MAGI-3. This is a sensitive in vitro assay as evident by the binding of GST-LPA2 to NHERF1 in the proteomic array, although we and others have previously shown that this association does not occur in vivo [10,19]. On the other hand, we were not able to observe the binding of the GST-LPA2 to the PDZ domains of RhoGEF or LARG under the experimental conditions. Thus, the list of PDZ domains identified here is certainly not exhaustive and there may be additional PDZ proteins that can associate with LPA2.

Our data reported here demonstrated that LPA2 specifically interacted with MAGI-3. LPA2 preferentially bound to the fifth PDZ domain of MAGI-3 as demonstrated by both the proteomic arrays and in vitro overlay assays. We also showed that LPA1, despite having a Class I PDZ domain interacting sequence, -SVV, was not able to bind to MAGI-3. A similar preference for LPA2 over LPA1 has been observed with NHERF2. In contrast, PDZ-RhoGEF and LARG bind to both LPA2 and LPA1 with similar efficacy [20]. Our mutational analysis of LPA2 carboxyl-terminus showed that, in addition to the terminal Leu, there was a strong preference for Asp at the −3 position of LPA2, which is absent in LPA1. Studies have previously shown that the presence of an acidic amino acid at −3 can greatly influence the PDZ binding characteristics, and NMDA receptors, the only other protein known to bind to MAGI-3/PDZ5, also possess an acidic amino acid at the −3 position [16,17,21,27].

Among the PDZ domains identified, we have chosen to study the association between LPA2 and MAGI-3, since MAGI-3 is ubiquitously expressed in all tissues, including the gastrointestinal tract [27,28]. In human colonic epithelial Caco-2 cells, MAGI-3 has been found at the apical membrane and the nucleus as well as at tight junctions [30]. In contrast, the expression of MAGI-2 is largely limited to the brain although localized expression in other types of tissue has been reported [33]. MAGI-3 contains multiple protein interacting domains, including 5 PDZ domains, 2 WW domains, and a guanylate kinase domain [27]. Through these protein-interacting domains, MAGI-3 is able to interact with a number of proteins, including frizzled, PTEN/MMAC, transforming growth factor-α, and receptor tyrosine phosphatase-β [27,30,34,35]. Recently, MAGI-3 has been shown to associate with β1-AR and impair the receptor’s Gi-mediated signaling [21]. In colon cancer cells, we have previously demonstrated that LPA2 activates Akt via a PTX-sensitive pathway [10]. In the current study, overexpression or knockdown of MAGI-3 did not affect the Gi-mediated Akt activation, suggesting that MAGI-3 does not always impact the Gi-mediated pathway and that the effect of MAGI-3 on the Gi-mediated signaling is likely to be receptor dependent. Unlike the previous studies where overexpression or knockdown of PDZ-proteins results in a drastic change in signaling, knockdown of MAGI-3 did not completely abrogated LPA-induced signaling. We reason that the residual signaling must be facilitated via either the remaining MAGI-3 (20% or less) in SW480/MAGI-3 cells or other PDZ proteins expressed in these cells. NHERF2, which also interacts with LPA2, is expressed in SW480 as well as other colon cancer cells. Previous studies have shown that NHERF2 also facilitates the activation of Erk by LPA2, and knockdown of NHERF2 resulted in partial attenuation of Erk activation, a result similar to that by MAGI-3 knockdown.

The present study shows that overexpression of MAGI-3 did not exert any measurable effect on the activation of Erk, whereas there was a clear increase in RhoA activation. Although we do not know the reasons behind these discriminating effects by MAGI-3, one possibility is that MAGI-3 facilitates activation of Erk and RhoA with differential efficiency. The results suggest that LPA-induced Erk activation is efficiently mediated, probably to its full capacity, through the interaction with endogenous MAGI-3 such that exogenously expressed MAGI-3 failed to influence the signal transduction. Therefore, knockdown of MAGI-3, but not overexpression, was able to alter the magnitude of LPA-induced Erk activation. We found that the effect of MAGI-3 on RhoA differed from its effect on Erk. The positive effect on RhoA by overexpression implies that endogenous MAGI-3 has a limited capacity to regulate RhoA in response to LPA. Hence, overexpression of MAGI-3 led to an increase in RhoA activation over the basal activation level. In contrast, the limited RhoA activation via MAGI-3 resulted in a modest effect by knockdown of MAGI-3

It is well established that G proteins of the G12-family, G12 and G13, can couple GPCRs to activate RhoA. It is generally accepted that LPA-induced RhoA activation is mediated by G12/13. Studies have shown a role of Rho-specific exchange factors, PDZ-RhoGEF and LARG, in linking G12/13 and RhoA [11,20,36]. However, an unidentified protein-tyrosine kinase has been implicated in RhoA activation, suggesting that the presence of G12/13 and a RhoGEF is not sufficient for efficient RhoA activation [31]. In addition, it has been shown using G12/13-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts that Gq-mediated signaling can contribute to RhoA activation [12]. A recent study has shown that RhoA activation can occur via distinct pathways involving Gα12/13 or Gαq such that the expression of activated Gαq in HEK293T cells led to a robust activation of RhoA in a Gα13-independent mechanism [37]. Although the mechanism of Gαq-mediated RhoA activation is not clear, it seems that Gαq mediates RhoA activation independent of PLCβ or elevation of intracellular Ca2+ [12]. We speculate that MAGI-3 might be able to interact with Gαq based on a previous report that the constitutively activated Gαq mutant can bind to a PDZ domain [38]. Hence, MAGI-3 may enhance the coupling of Gαq to LPA2, facilitating the Gαq-dependent activation of Erk and RhoA. On the other hand, it is possible that signaling intermediates necessary for Erk or RhoA activation bind at distinct sites within MAGI-3 such that LPA2 activates Erk and RhoA independently. MAGI-3 possesses multiple protein-interacting domains and thus appears capable of mediating concomitant interactions with more than one protein.

This study demonstrates that MAGI-3 is coupled to LPA2 receptor. The interaction with MAGI-3 is specific to LPA2, but not to LPA1 or LPA3. The coupling of MAGI-3 facilitates LPA2-mediated activation of Erk and RhoA. In light of recent studies showing overexpression of LPA2 in several types of cancers and the roles of LPA in activation of oncogenic signal pathways [10,39-41], the current findings suggest that MAGI-3 may potentially enhance cell survival and gene transcription via the activation of Erk and RhoA.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R.A.H. and C.C.Y.), the W.M. Keck Foundation (R.A.H.), the Emory University Research Committee (C.C.Y.), and the Emory Epithelial Pathobiology Research Development Center (C.C.Y.). We would like to thank Dr. Martin Schwarts for GST-RBD and Amenda Castleberry for the technical assistance in PDZ proteomic screen.

References

- 1.Tigyi G, Parrill AL. Prog Lipid Res. 2003;42:498. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(03)00035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ye X, Ishii I, Kingsbury MA, Chun J. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1585:108. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00330-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goetzl EJ, An S. FASEB J. 1998;12:1589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kranenburg O, Moolenaar WH. Oncogene. 2001;20:1540. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.An S, Dickens MA, Bleu T, Hallmark OG, Goetzl EJ. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1997;231:619. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.An S, Bleu T, Hallmark OG, Goetzl EJ. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7906. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.7906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aoki J, Bandoh K, Inoue K. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;905:263. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noguchi K, Ishii S, Shimizu T. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:25600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302648200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moolenaar WH. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253:230. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yun CC, Sun H, Wang D, Rusovici R, Castleberry A, Hall RA, Shim H. Am J Physiol. 2005;289:C2. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00610.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Q, Liu M, Kozasa T, Rothstein JD, Sternweis PC, Neubig RR. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:28831. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400105200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vogt S, Grosse R, Schultz G, Offermanns S. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28743. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304570200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fanning AS, Anderson JM. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:767. doi: 10.1172/JCI6509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Songyang Z, Fanning AS, Fu C, Xu J, Marfatia SM, Chishti AH, Crompton A, Chan AC, Anderson JM, Cantley LC. Science. 1997;275:73. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hung AY, Sheng M. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5699. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100065200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hall RA, Ostedgaard LS, Premont RT, Blitzer JT, Rahman N, Welsh MJ, Lefkowitz RJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:8496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.15.8496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fam SR, Paquet M, Castleberry AM, Oller H, Lee CJ, Traynelis SF, Smith Y, Yun CC, Hall RA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8042. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408818102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung HJ, Huang YH, Lau LF, Huganir RL. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10248. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0546-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oh YS, Jo NW, Choi JW, Kim HS, Seo SW, Kang KO, Hwang JI, Heo K, Kim SH, Kim YH, Kim IH, Kim JH, Banno Y, Ryu SH, Suh PG. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5069. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.11.5069-5079.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamada T, Ohoka Y, Kogo M, Inagaki S. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19358. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414561200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He J, Bellini M, Inuzuka H, Xu J, Xiong Y, Yang X, Castleberry AM, Hall RA. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509503200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Virag T, Elrod DB, Liliom K, Sardar VM, Parrill AL, Yokoyama K, Durgam G, Deng W, Miller DD, Tigyi G. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:1032. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.5.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yun CC, Chen Y, Lang F. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7676. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107768200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ren XD, Schwartz MA. Methods Enzymol. 2000;325:264. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)25448-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu J, Paquet M, Lau AG, Wood JD, Ross CA, Hall RA. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:41310. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107480200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Terry-Lorenzo RT, Carmody LC, Voltz JW, Connor JH, Li S, Smith FD, Milgram SL, Colbran RJ, Shenolikar S. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27716. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203365200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu Y, Dowbenko D, Spencer S, Laura R, Lee J, Gu Q, Lasky LA. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21477. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909741199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wood JD, Yuan J, Margolis RL, Colomer V, Duan K, Kushi J, Kaminsky Z, Kleiderlein JJ, Sharp AH, Ross CA. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1998;11:149. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1998.0677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakanishi H, Obaishi H, Satoh A, Wada M, Mandai K, Satoh K, Nishioka H, Matsuura Y, Mizoguchi A, Takai Y. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:951. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.4.951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adamsky K, Arnold K, Sabanay H, Peles E. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1279. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kranenburg O, Poland M, van Horck FPG, Drechsel D, Hall A, Moolenaar WH. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:1851. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.6.1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu J, Lai Y-J, Lin W-C, Lin F-T. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10459. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311891200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lehtonen S, Ryan JJ, Kudlicka K, Iino N, Zhou H, Farquhar MG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504166102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Franklin JL, Yoshiura K, Dempsey PJ, Bogatcheva1 G, Jeyakumar L, Meise KS, Pearsall RS, Threadgill D, Coffey RJ. Exp Cell Res. 2005;303:457. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yao R, Natsume Y, Noda T. Oncogene. 2004;23:6023. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suzuki N, Nakamura S, Mano H, Kozasa T. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0234057100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chikumi H, Vazquez-Prado J, Servitja J-M, Miyazaki H, Gutkind JS. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:27130. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204715200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rochdi MD, Watier V, La Madeleine C, Nakata H, Kozasa T, Parent JL. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40751. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207910200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shida D, Watanabe T, Aoki J, Hama K, Kitayama J, Sonoda H, Kishi Y, Yamaguchi H, Sasaki S, Sako A, Konishi T, Arai H, Nagawa H. Lab Invest. 2004;84:1352. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fang X, Gaudette D, Furui T, Mao M, Estrella V, Eder A, Pustilnik T, Sasagawa T, Lapushin R, Yu S, Jaffe RB, Wiener JR, Erickson JR, Mills GB. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;905:188. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang MC, Lee HY, Yeh CC, Kong Y, Zaloudek CJ, Goetzl EJ. Oncogene. 2004;23122 doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]