SUMMARY

X-ray crystallography of biologically important RNA molecules has been hampered by technical challenges, including finding a heavy-atom derivative to obtain high-quality experimental phase information. Existing techniques have drawbacks, severely limiting the rate at which important new structures are solved. To address this need, we have developed a reliable means to localize heavy atoms specifically to virtually any RNA. By solving the crystal structures of thirteen variants of the G·U wobble pair cation binding motif we have identified an optimal version that when inserted into an RNA helix introduces a high-occupancy cation binding site suitable for phasing. This “directed soaking” strategy can be integrated fully into existing RNA and crystallography methods, potentially increasing the rate at which important structures are solved and facilitating routine solving of structures using Cu-Kα radiation. The success of this method has been proven in that it has already been used to solve several novel crystal structures.

Keywords: RNA structure, cation binding, G·U pairs, X-ray crystallography, hexammine, phasing

INTRODUCTION

The role of RNA in biology is varied and rich, with RNA playing diverse roles in both healthy and diseased cells. The function of many biologically important RNAs is conferred by their three-dimensional fold, and X-ray crystallography remains the most powerful tool to determine their structure. While protein crystallography has progressed to the point where structural genomics efforts are a reality, RNA crystallography has lagged. This is due in large part to technical difficulties in rapidly purifying large amounts of RNA and solving the phase problem once diffracting crystals are obtained (Doudna, 2000). Protein crystallography was transformed in significant part by affinity purification techniques (Mondal and Gupta, 2006) and selenomethionine labeling (Doublie, 1997; Hendrickson et al., 1990), which provided generally applicable strategies for solving protein structures. Analogous tools for RNA could make RNA crystallography available to a broad range of researchers. Recently developed methods are addressing the issue of high-throughput RNA purification (Cheong et al., 2004; Kieft and Batey, 2004; Kim et al., 2007; Lukavsky and Puglisi, 2004); here we present a general strategy for obtaining phase information to solve the crystal structure of potentially any RNA.

Modern techniques to solve crystal structures require a suitable heavy atom derivative, yet there is no universally applicable method for routinely obtaining this. Strategies to obtain diffracting RNA crystals have been described (Cate and Doudna, 2000; Golden, 2007; Ke and Doudna, 2004; Wedekind and McKay, 2000), but obtaining a derivative remains nontrivial (Golden, 2000; Golden, 2007). As a result considerable time, effort, and resources are often spent trying different methods to obtain phase information. The most traditional means of obtaining an RNA derivative is to soak many different heavy atoms at different concentrations into the crystal in an approach that relies on fortuitous, high-occupancy heavy atom binding in specific sites. This method is successful in many cases but because the presence of suitable sites in an RNA cannot be predicted or assured, it has been called “soak and pray” (Golden, 2000; Golden et al., 1996; Wedekind and McKay, 2000). Other RNA derivatizing techniques use RNA covalently modified with halogens (e.g. 5-bromouracil) (examples in (Baugh et al., 2000; Kieft et al., 2002; Martick and Scott, 2006)), selenium (Brandt et al., 2006; Carrasco et al., 2004; Hobartner and Micura, 2004; Hobartner et al., 2005; Jiang et al., 2007; Salon et al., 2007; Sheng et al., 2007), or other heavy atoms (Correll et al., 1997), and while covalent derivitazation methods have been successful they are not suitable for all RNAs. Another method of obtaining phase information is to introduce a protein binding site into the initial crystallization construct and co-crystallize the RNA with the selenomethionine-labeled protein once crystals have been obtained (Ferre-D’Amare and Doudna, 2000; Ferre’-D’Amare’ et al., 1998; Rupert and Ferre-D’Amare, 2001). All of these methods have utility, but in general each is suitable for a subset of RNAs and thus the process of obtaining a derivative remains a key bottleneck in the process of solving RNA crystal structures.

We set out to develop a general strategy to derivatizate RNA crystals with reagents readily purchased or made and without the additional step of synthesizing and crystallizing modified RNA. We based our strategy on the proven power of trivalent hexammine complex ions to provide phase information through multiple- or single-wavelength anomalous diffraction (MAD or SAD) methods and their inherent affinity for RNA. In the last few years multiple structures have been solved using cobalt (III) hexammine, iridium (III) hexammine, or osmium (III) hexammine ions (examples in (Batey et al., 2004; Cate et al., 1996b; Cochrane et al., 2007; Kazantsev et al., 2005; Montange and Batey, 2006; Pfingsten et al., 2006)), suggesting that if the ions can be positioned rationally and specifically in a crystallized RNA, phases can be obtained. Rationally positioning heavy atoms in this way is analogous to a method developed by protein crystallographers in the late 1980s in which the “soak and pray” technique was improved by using site-directed mutagenesis to specifically introduce cysteines that bind mercury atoms in a “directed soak” approach (Stock et al., 1989; Sun et al., 1987).

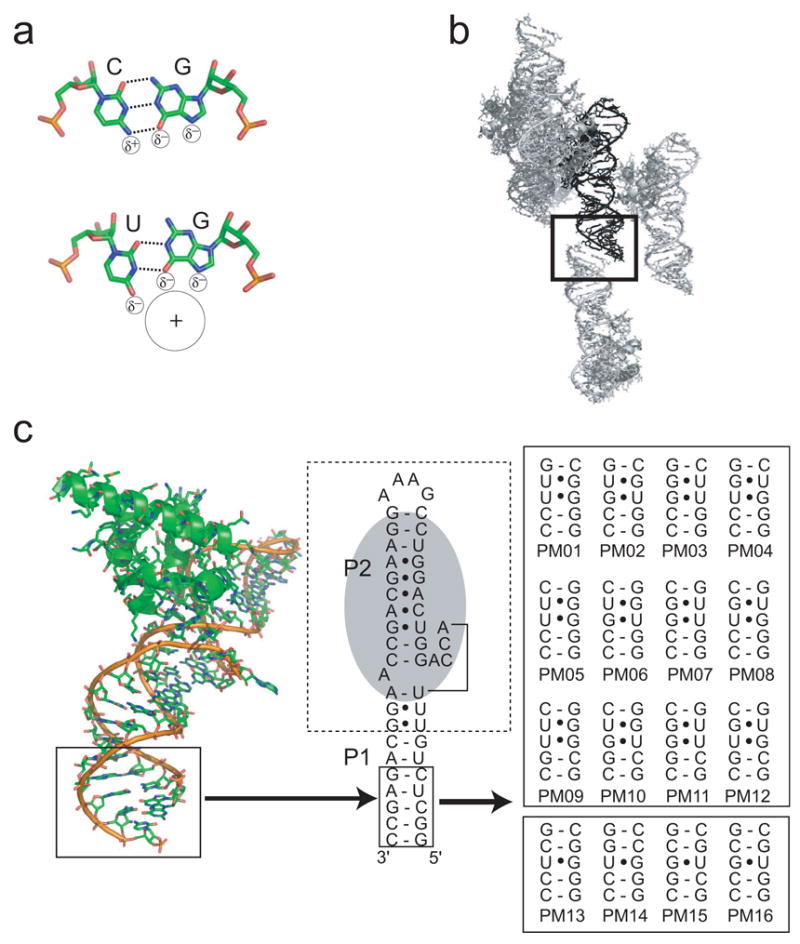

Towards the goal of reliably positioning hexammine ions in RNA we used the G·U wobble pair motif (Masquida and Westhof, 2000; Varani and McClain, 2000), which creates a pocket for cation binding in the major groove that is lined by partially negatively charged RNA functional groups (Figure 1a). Versions of this motif bind hexammine complexes (Cate and Doudna, 1996; Colmenarejo and Tinoco, 1999; Kieft and Tinoco, 1997; Montange and Batey, 2006; Stefan et al., 2006), and thus we reasoned that this inherent affinity could be used to engineer a hexammine binding site into any RNA helix. However, it was clear from a survey of many different RNA structures that not all versions of the G·U pair motif bind cations equally well (Keel & Kieft, data not shown), which is likely why this motif has not been used for routine rational localization of cations. Thus, the practical use of G·U pairs to localize a heavy atom required that we determine the rules of the interactions and identification of the optimal motif version for this purpose.

Figure 1. The use of G·U pairs and the crystallization chassis.

a) Schematic of a canonical RNA G-C base-pair and a G·U wobble pair. The G·U pair places partially negative charges in the major groove, forming a pocket for cation binding. b) Diagram of intermolecular packing in the crystal of the SRP RNA-M domain previously reported by Batey et al (Batey et al., 2000; Batey et al., 2001). The end of RNA helix P1 (black) stacks on P1 from an adjacent molecule (grey) in a fairly loose intermolecular contact (boxed). No other crystal contacts are made by this portion of the RNA. c) The structure of the SRP RNA-M domain complex is shown on the left with the mutated helix. In the middle is a schematic of this complex. The protein binding site is shown in grey and the hashed box denotes the portion involved in the majority of crystal contacts. The solid box is the portion of the P1 helix that is displayed by this crystallization chassis, and which was mutated into the various sequences shown at right.

We performed a detailed crystallographic analysis of hexammine complex binding to the G·U motif using a strategy in which a “crystallization chassis” was employed to solve the structures of thirteen different motif variants. Comparison of these structures allowed us to identify versions that recruit a hexammine ion with high occupancy and order. Combined with the appropriate cations, this results in a phasing strategy that uses readily available reagents, does not require separate crystallization of a derivatized RNA, can be adapted to some RNA crystals grown in very high salt concentrations, is fully integrated with existing RNA crystallography methods, and can be used to obtain phase information from both synchrotron and rotating copper anode (“at-home”) radiation. This strategy has resulted in the determination of three novel RNA structures, proving it to be a robust means of acquiring phase information.

RESULTS

Design and use of a “crystallization chassis”

A heavy atom site that is useful for phasing is one in which the occupancy of the site is high and the B-factor (measurement of the motion of the cation) is low and thus our first goal was to determine the G·U motif features that affect these characteristics. We hypothesized that both the orientation of the G·U pairs (in tandem pairs) and the flanking base pairs are important determinants of high-order, high-occupancy cation binding. To test these ideas, we needed to systematically crystallize different motif variants while maintaining nearly identical crystallization conditions. We therefore developed a “crystallization chassis” that consists of the RNA/M-domain protein complex from the E. coli signal recognition particle (SRP) solved to high resolution by Batey et al. (Batey et al., 2000; Batey et al., 2001). In addition, examination of this complex in the presence of various cations shows it accommodates a variety of metal ions without structural changes (Batey and Doudna, 2002). In this structure most crystal contacts are mediated by the protein and GAAA tetraloop; the P1 helix stacks only loosely on the helix of an adjacent molecule (Figure 1b&c). This suggested we could insert virtually any G·U-containing sequence into this helix (box, Figure 1c) and obtain crystals. This approach is preferable to crystallizing multiple small isolated RNA helices with different versions of the G·U motif because each of those helices represents a unique crystallization target, requiring optimization of different crystallization conditions.

We chose the trivalent cation cobalt (III) hexammine as our probe for several reasons: first, it is readily observed in the electron density and distinguished from other ligands (such as water). Second, the cobalt atom scatters anomalously at the wavelength of Cu-Kα X-rays generated by a rotating copper anode (f′=3.608 e−) and thus we could analyze the anomalous signal without synchrotron radiation. Third, cobalt (III) hexammine has been observed to bind to the same sites as iridium (III), osmium (III), or rhodium (III) hexammine (Cate and Doudna, 1996; Cate et al., 1996a; Ennifar et al., 2003). Fourth, the SRP RNA/M-domain crystallization chassis has been crystallized with cobalt (III) hexammine and this structure provides a starting point for our analysis (Batey and Doudna, 2002). Lastly, the ion is commercially available and inexpensive. The issue of whether or hexammines are good mimics for hexahydrated magnesium is not of importance here.

Figure 1c shows the sixteen sequences we inserted into the crystallization chassis, including tandem and single G·U pairs. Each row of Figure 1c contains variants of the motif in which the orientation of the G·U pairs is changed, and each column contains versions in which the orientation of one or both of the G-C flanking sequences is changed. Using the crystallization chassis, we were able to crystallize thirteen of the sixteen variants in similar conditions. The crystals had the same space group, and similar unit cell dimensions and morphologies.

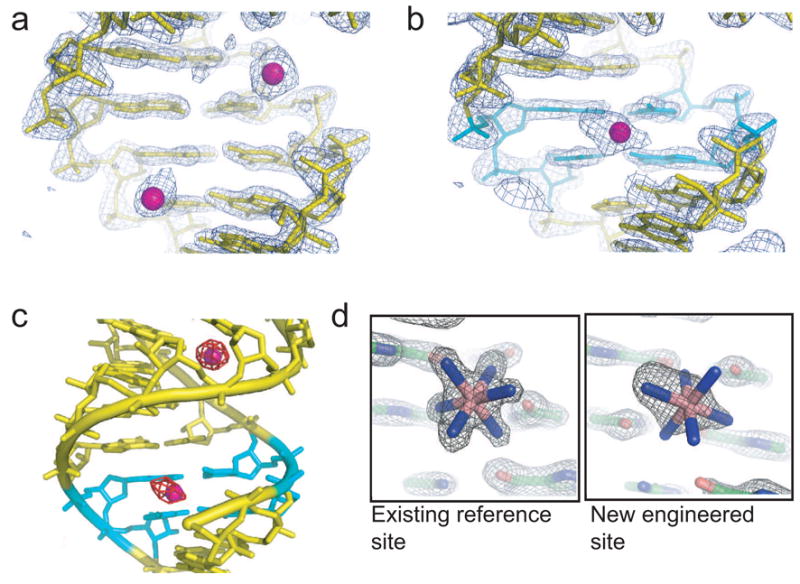

Inserting G·U pairs creates a cation binding site

The first structure we solved was PM04 (Figure 1c), and examination of this structure illustrates the success and utility of the crystallization chassis. In the crystallization chassis containing the unmutated SRP RNA (no engineered G·U sites) that was soaked with cobalt (III) hexammine (Batey and Doudna, 2002), there are two cations localized near the phosphate backbone on opposite sides of the helix (Figure 2a), but none at this location in the major groove. When this helix is mutated to contain two tandem G·U pair (PM04) the two sites are replaced by a single area of electron density in the major groove at the wobble pairs (Figure 2b). The identity of these sites as cobalt (III) hexammine ions was verified using anomalous difference Fourier maps (Figure 2c). Hence, we were able to engineer and display a new major groove cation binding site in the RNA, demonstrating the chassis could be used to examine more motif variants.

Figure 2. Engineered cation binding.

a) Electron density and structure of the wild-type SRP RNA-M domain complex, showing the portion of the helix that was varied. The view is into the major groove. Two cobalt (III) hexammine ions (magenta) are located near the phosphate backbone (upper right site) and two adjacent G-C pairs (lower left). b) Electron density and structure of the variant PM04, with the tandem wobble pairs shown in cyan and the resultant major groove-bound cobalt (III) hexammine in magenta. c) Anomalous difference Fourier map (contoured at 7 σ in red) of PM04 superimposed on the structure. The tandem wobble pairs are shown in cyan. The endogenous reference site is at the top, and the new engineered site at the bottom. d) Comparison of the very well-ordered reference site to the new site in PM04 in a 2Fo-Fc map, at 2 Å resolution, contoured at 2 σ.

Criteria for judging the quality of a binding site

There is an endogenous cobalt (III) hexammine binding site at tandem G·U pairs located away from our site of mutation, containing a high-occupancy well-ordered cation (Figure 2d) that was unchanged by mutagenesis. Comparing the electron density of this endogenous site to the engineered site of PM04 clearly shows differences. Specifically, the endogenous site is so highly ordered that the ammine ligands are well-oriented with respect to the RNA, whereas the engineered site appears elongated without defined ammine density. This endogenous site is a good internal control to standardize the information from each engineered site. To judge each engineered site against this internal control site, we established two criteria. The first is the B-factor of the engineered site divided by the B-factor of the existing reference site (Brel). Since the B-factor reflects the degree of order of the cation, this measure compares localization of the cobalt (III) hexammine in each motif variant. The second criteria is the relative size of the anomalous difference peak associated with the engineered site in an anomalous difference Fourier map (Anomrel), which reflects the both the order and occupancy of the site. Hence, bound cations with lower Brel and higher Anomrel are the most useful for phasing. As an example, the Brel of the engineered site of PM04 (Figure 2b) is 1.54 and Anomrel is 0.74, which is the fifth largest peak in the map (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of statistics for cobalt (III) hexammine binding in the major groove of various G·U pair motifs

| RNA | Sequence | Rwork1 | Rfree1 | Brel2 | Anomrel3 | Rank of anom. diff. peak |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tandem G·U Pairs | ||||||

| PM01 | GGGC/GUUC | 25.1% | 28.3% | 1.84 | 0.65 | 5 |

| PM02 | GUGC/GUGC | 24.5% | 27.2% | 1.36 | 0.48 | 7 |

| PM034 | GUUC/GGGC | 24.5% | 44.4% | - | - | - |

| PM04 | GGUC/GGUC | 23.4% | 27.3% | 1.54 | 0.74 | 5 |

| PM05 | GGGG/CUUC | 26.8% | 31.2% | 1.19 | 0.78 | 2 |

| PM06 | GUGG/CUGC | 27.7% | 31.4% | 1.55 | 0.46 | 11 |

| PM074 | GUUC/CGGC | 31.2% | 35.5% | - | - | - |

| PM08 | GGUG/CGUC | 27.8% | 31.3% | 1.14 | 1.06 | 1 |

| PM09 | CGGG/CUUG | 23.8% | 26.0% | 1.46 | 0.56 | 4 |

| PM105 | CUGG/CUGG | - | - | - | - | |

| PM115 | CUUG/CGGG | - | - | - | - | |

| PM125 | CGUG/CGUG | - | - | - | - | |

| Single G·U Pairs | ||||||

| PM13 | GGG/CUC | 23.2% | 26.9% | 1.16 | 0.94 | 3 |

| PM14 | GGC/GUC | 29.2% | 34.1% | 1.22 | 0.86 | 3 |

| PM156 | CUG/CGG | 22.3% | 24.5% | 1.15 | 0.67 | 3 |

| PM167 | GUG/CGC | 26.3% | 31.4% | - | - | - |

Rwork = Σ|Fo−|Fc||/Σ|Fo|, Rwork from the working set and Rfree from the test set (10% of the data).

Relative B = B-factor of engineered site/B-factor of reference site

Relative anom. signal = height of engineered site peak in anomalous difference Fourier map/height of reference site peak in anomalous difference Fourier map.

These constructs yielded crystals of poorer quality, and thus were not included in our analyses or submitted to the PDB.

These constructs failed to crystallize.

Values given are for the site closest to the binding pocket.

No hexammine was observed in the binding pocket.

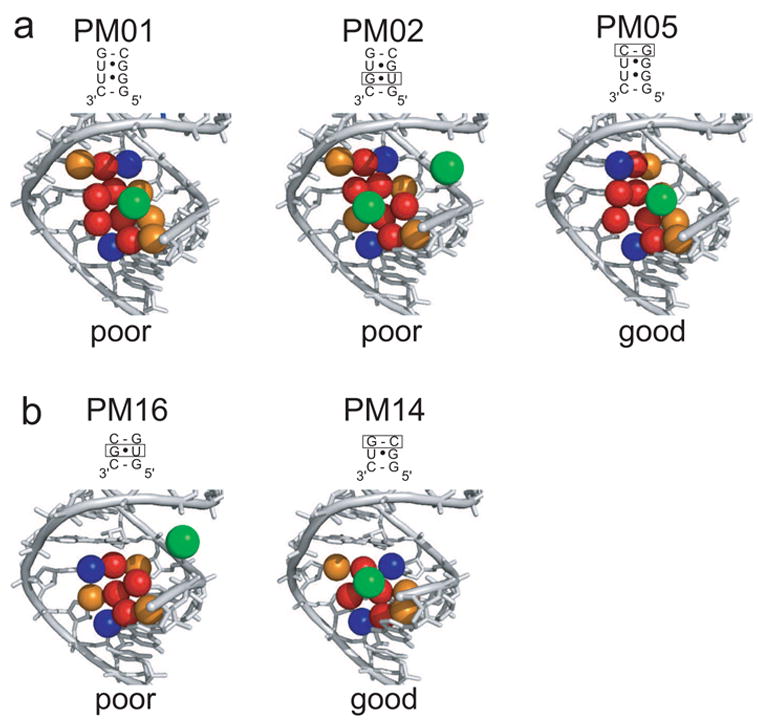

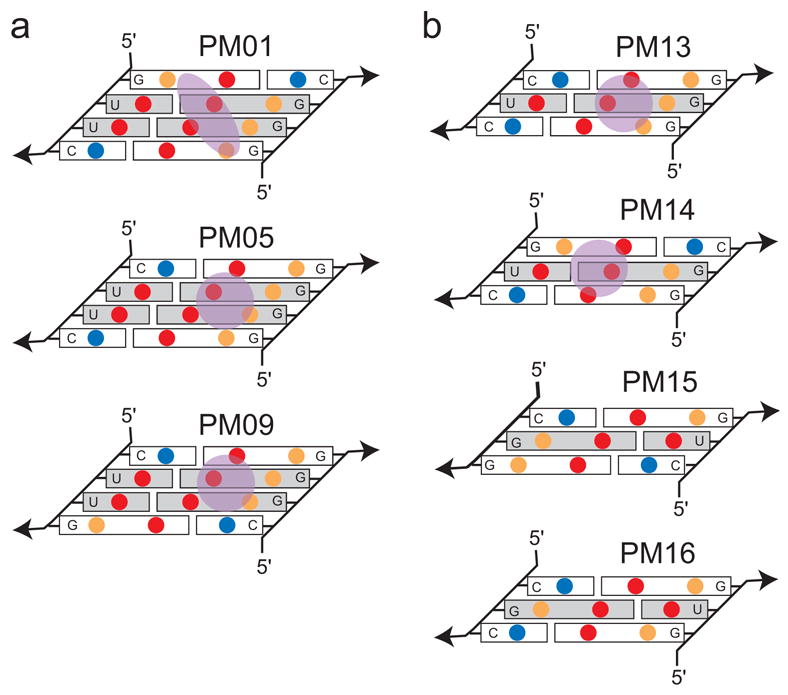

Tandem G·U pairs: position and localization of the cation

We solved the structures of seven versions of the tandem G·U motif (Supplemental Figure S1), revealing the effects of changing the orientation of the tandem pairs as well as the flanking sequences (Figure 3a). Changing the orientation of the tandem G·U pairs changes the location of the cobalt (III) hexammine in the binding pocket and in some cases allows binding of a second cobalt (III) hexammine just next to the pocket. This occurs because the positioning of groups within the pocket changes with the relative orientation of the G·U pairs. In cases where the U-bases were in the 5′ positions (e.g. PM02, PM06), the pocket geometry was such that the hexammine complex is moved substantially relative to its position in other motif variants. However, although the relative orientation of the G·U pairs alters the position of the cation, it does not substantially alter its Brel or Anomrel (Table 1), indicating little change in the site occupancy or order.

Figure 3. Comparison of cation binding in selected variants of the motif.

a) Comparison of cobalt (III) hexammine binding in the major groove of three representative motif variants. Major groove carbonyls of the wobble G·U pairs and the flanking Watson-Crick pairs are shown in red, N7 nitrogens are shown in orange, and cytosine amines are shown in blue. The location of bound hexammine ions is shown in green. The sequence of each variant is shown above the structure with boxes denoting the difference when compared to PM01. PM01 and PM02 differ in the relative orientation of their tandem G·U pairs, which moves the cation in the site. Both are examples of poor sites for localizing a hexammine. PM05 differs from PM01 by the orientation of a flanking pair, and it is an example of a good site with high occupancy and a high degree of cation localization (low Brel and high Anomrel, Table 1). Structures of the other tandem G·U pairs are contained in Supplemental Figure S1. b) Comparison of two representative single G·U pair-containing sequences. The sequence of each variant is shown above the structure with boxes denoting the difference when compared to PM13. PM14 contains a very good site, while PM16 has no hexammine in the pocket. Colors are the same as panel a, this figure. Structures of the other two single G·U pair-containing sequences are in Supplemental Figure S2.

Changing the orientation of a flanking pair is different than changing the orientation of the G·U pairs (Supplemental Figure S1) in that the primary effect is not to move the cation, but to increase the degree of cation order and occupancy as reflected in Brel and Anomrel (Table 1). These observations demonstrate thatthe overall nature of the binding pocket and it usefulness as part of a phasing strategy depends on the orientation of both G·U pairs and flanking pairs and hence the motif comprises four base-pairs.

Cation localization: the affect of caging amines

The observation that the orientation of flanking base pairs affects cation localization is likely due to major groove RNA amine groups. In the variants examined here, this amine group is supplied by a cytosine of the flanking pairs, but could also be supplied by an adenine. In PM01-PM04, the cytosine is in a 3′ position in relation to the cation binding pocket, and thus is withdrawn from the pocket by the turn of the helix. In PM05-PM08, one cytosine is placed 5′ to the tandem pairs, moving an amine group into a prominent position in the major groove. This electropositive amine repels the cation, possibly caging it on one side and limiting its movement in the pocket. This is illustrated by comparing PM01 to PM05 (Figure 3a and 4a). In PM01, the ion is mobile as it attempts to satisfy potential hydrogen bonding partners from not only the tandem G·U pairs, but also from the two flanking pairs (Figure 4a), an effect also evident in the elongated density of the engineered site of PM04 (Figure 2b). In PM05, the motion of the ion is restricted possibly due to the major groove amine placed on one side of the binding site (Figure 4a), reducing its Brel. Based on this reasoning, placing two major groove amines 5′ to the tandem pairs should result a very well-ordered cation, but alternate crystal packing of PM09 and the failure of PM10, 11, and 12 to crystallize prevented us from directly testing this (Supplemental Figure S1).

Figure 4. General rules for cation binding in the major groove of G·U motifs.

a) Schematic of the arrangement of major groove functional groups for PM01, PM05, and PM09. These three variants vary only in the orientation of flanking G-C pairs relative to the tandem G·U pairs. Blue circles are amine, red are carbonyls, and orange are purine N7 groups. In PM01, the two major groove amines (from cytosine) are placed away from the binding site due to the turn of the helix. In PM05 and PM09, the amines are placed in position to limit the mobility of the ion (shown in green). In addition, the location of carbonyls and N7 groups in the flanking sequences and close to the binding site make the ion more mobile as it attempts to satisfy multiple potential hydrogen binding partners. b) Schematic of the arrangement of major groove functional groups in the four single G·U pair containing variants. In single G·U pairs, the amines are best placed in the 3′ positions to withdraw them from the pocket.

Binding to single G·U pairs

To examine the ability of a single G·U wobble pair to bind hexammine compounds, we crystallized variants PM13-PM16 (Figure 1c), examining the effects of both the orientation of the single wobble and flanking pairs (Supplemental Figure S2). Only two effectively bound an ion, but in both cases the site was of high-order and high-occupancy (as judged by Brel and Anomrel, Table 1). Thus, single G·U pairs are more sensitive to flanking sequence and disruptions in the pocket shape than are tandem G·U pairs, likely due to the smaller overall size of the binding pocket. In single G·U pairs the uracil of the wobble pair is best followed by an amine-containing nucleotide (Figure 4b). This withdraws the amines from the major groove and allows sufficient room for cation binding. In the case of PM15, the uracil carbonyl of the G·U extends into the major groove and disrupts the pocket, similar to PM02 and PM06 (Supplementary Figure S1 and S2). Hence, useful binding into single G·U pairs are the reverse of those for tandem pairs: in tandem pairs we hypothesize that 5′ amines cage and localize the cation, while in single pairs these amines exclude the cation (Figures 3b and 4b).

An optimal single G·U pair and hexammines define the method

The detailed analysis of thirteen structures identifies that both PM13 and PM14 are good versions of the motif for use as a hexammine complex binding site. We pursued PM14 for further analyses and experimentation, which is a single G·U pair with the sequence: 5′-GUC-3′/5′-GGC-3′ or 5′-UUA-3′/5′-UGA-3′ (Figure 1c and Figure 3b). Both the Brel and Anomrel, for a hexammine bound in this site are among the best. In addition, a single G·U pair motif has the advantage of being a three base pair motif (compared to four base pairs for tandem pairs), requiring a smaller sequence change to the helix when introduced.

This single wobble pair motif and readily available hexammines are combined to yield a general strategy for obtaining a derivative crystal and thus phase information. First, one or more helices in the RNA are identified that are conserved in terms of formation, but not conserved in terms of sequence. Second, these helices are mutated to introduce the optimal motif, which requires at most a change to three base pairs of the RNA and does not alter formation of the helix. The RNA is co-crystallized with ~5 mM hexammine cations or the cations are soaked into the crystal during cryoprotection, resulting in the high-occupancy, tightly constrained binding of a hexammine ion used to obtain phase information.

Demonstrated successes of the phasing strategy

The true test of this phasing method and its general applicability is if it can be used to solve novel RNA structures. As of this writing, several novel crystal structures have been solved using this phasing strategy, succeeding in one case when multiple other methods failed.

The first example is the SAM-1 riboswitch RNA, the structure of which was solved during the development of our phasing method (Batey et al., 2001; Gilbert et al., 2006). A single optimal motif (5′-UUA-3′/5′-UGA-3′) was inserted into one helix and another single G·U pair that does not conform to the rules was inserted into another helix. Crystals of this RNA were grown in the presence of iridium (III) hexammine to yield the derivative used to solve the structure using MAD phasing with synchrotron radiation. Examination of the location of the hexammine complexes in the structure shows that a cation bound strongly to the optimal site but none was observed in the non-optimal site, matching our predictions. This same preferential binding of iridium (III) hexammine in an optimal site, but not another site, was observed in a recent structure of the GlmS riboswitch/ribozyme (J. Cochrane and S. Strobel, Yale University, personal communication). Furthermore, the anomalous signal provided from the “directed soak” of this hexammine ion into an engineered site on the SAM-1 riboswitch was critical for solving the structure, as illustrated by an examination of anomalous difference Patterson maps (Supplemental Figure S3).

Another example involved a situation where this phasing method might be predicted to fail. In this case, the crystals grew in and required very high salt conditions (e.g. >2 M Li2SO4), a condition in which the high [Li+] is expected to compete trivalent ions out of all binding sites. We also observed low solubility of the hexammine complexes in the high sulfate (data not shown) suggesting covalently modified RNAs were needed to obtain a derivative. To solve the phase problem, we tried traditional soaking methods, uniform and partial bromouracil incorporation, molecular replacement using model A-form RNA helices (Robertson and Scott, 2007), and SAD phasing using the phosphorus anomalous signal from a chromium rotating anode source (Dauter, 2002; Dauter and Adamiak, 2001), but we were unable to obtain phase information from any of these methods.

To solve this structure, we inserted the optimal motif into an RNA helix and took advantage of the high solubility of the acetate salts of iridium (III) hexammine and cobalt (III) hexammine (Lindholm, 1978). We exchanged the solution in steps from 2 M Li2SO4 to 3 M LiAcetate + 0.1 M hexammine acetate (both cobalt and iridium complexes were used). The high concentration of hexammine complex allowed it to compete for the binding site, and the high salt preserved and cryo-protected the crystal. We were then able to solve the structure, first using cobalt (III) hexammine and then independently using iridium (III) hexammine, both of which revealed a very well-ordered hexammine ion located in the engineered site. This structure will be presented in another manuscript (Costantino et al., submitted).

Using the phasing strategy to solve structures “at-home”

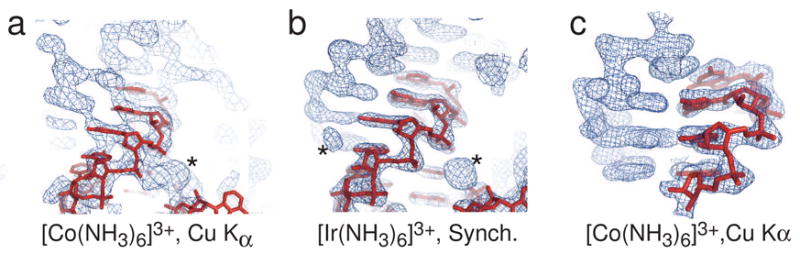

Phasing methods that use anomalous signal (MAD, SAD) almost always require synchrotron radiation. However, the ability to use cobalt atoms with anomalous scattering (1.61 Å) near the Kα energy of typical “at-home” rotating copper anode X-ray sources (1.54 Å) was demonstrated for RNA (Batey et al., 2004) and recently demonstrated for proteins (Guncar et al., 2007). To test if this method might be more generally applied and integrated with our phasing strategy, we used the RNA crystals grown in high salt described above and collected a dataset using Cu-Kα radiation. Using the program PHENIX to conduct automated SAD phasing and density modification, we located three cobalt (III) hexammine sites and obtained a preliminary interpretable electron density map (Figure 5a). This map was then improved using iridium (III) hexammine-soaked crystals and synchrotron radiation (Figure 5b). The same high-order, high-occupancy heavy-atom sites were found in both iridium and cobalt complexes.

Figure 5. Experimental electron density of RNAs phased using “at-home” and synchrotron radiation.

a) Experimental electron density of the “high salt” crystal described in the text, obtained using diffraction data collected with an “at-home” X-ray source and SAD phasing from a cobalt (III) hexammine derivative. In red is an RNA model placed in the density. The asterisk denotes density of a cobalt (III) hexammine. This density is not ideal, but is clearly RNA. b) Experimental electron density of exactly the same RNA in panel a, but phased at a synchrotron using MAD data and iridium (III) hexammine. Again, the red shows placed RNA and the asterisks denote two bound iridium (III) hexammines. When compared to panel a, the density is greatly improved. c) Experimental electron density of the SRP RNA/M-domain complex using diffraction data collected with an “at-home” X-ray source and SAD phasing from a cobalt (III) hexammine derivative. In red is RNA placed in the density. Although this electron density was obtained using only SAD data from a rotating anode and cobalt (III) hexammine, the density rivals that obtained from synchrotron radiation and MAD phasing.

As a second test, we used the dataset from PM15 (soaked with cobalt (III) hexammine) collected with Cu-Kα radiation and calculated phases using SAD and density modification. The resultant experimental electron density map rivals or exceeds the quality of maps obtained from synchrotron radiation and MAD phasing (Figure 5c). Hence, our phasing method may allow routine phasing of RNA crystals using typical “at-home” X-ray sources.

The use of different heavy atom cations

The optimal single G·U motif can also bind some, but not all, other heavy atoms. Recently, the motif was used with cesium atoms to solve the structure of a novel RNA using an “at-home” Cu-Kα X-ray source and SIRAS phasing (Supplementary Figure S4), demonstrating the utility of this commercially available cation (Gilbert et al., in preparation). In addition, the locations of the cesiums allowed unambiguous placement of multiple copies of the RNA into the asymmetric unit. In contrast, divalent barium ions did not bind in the engineered G·U motif of the SAM-1 riboswitch RNA (Montange & Batey, data not shown), demonstrating that not all cations are suitable for this phasing strategy. We have not conducted a comprehensive survey of cations binding to this site, but our results show that both commercially available cobalt (III) hexammine (trivalent) and cesium (monovalent) can be used, as can synthesized iridium (III) hexammine.

DISCUSSION

Obtaining experimental phase information is a critical step in solving macromolecular structures by X-ray crystallography, generally requiring specifically bound heavy atoms. For protein crystallography, uniform incorporation of selenomethionine residues during bacterial expression makes protein crystallography available to a broad range of users (Doublie, 1997; Hendrickson et al., 1990). For RNA, no analogous method has been available, for although RNA can be covalently modified with heavy atoms, there are limitations to this and to soaking heavy atom cations into the crystals (Golden, 2000; Golden, 2007). To address this gap, we have identified a simple and reliable means to localize one or more heavy atoms suitable for phasing to virtually any RNA target. This “directed soak” approach, based on a single G·U pair motif combined with various heavy atom cations, facilitates routine phasing of RNA crystal data using both rotating anode and synchrotron radiation.

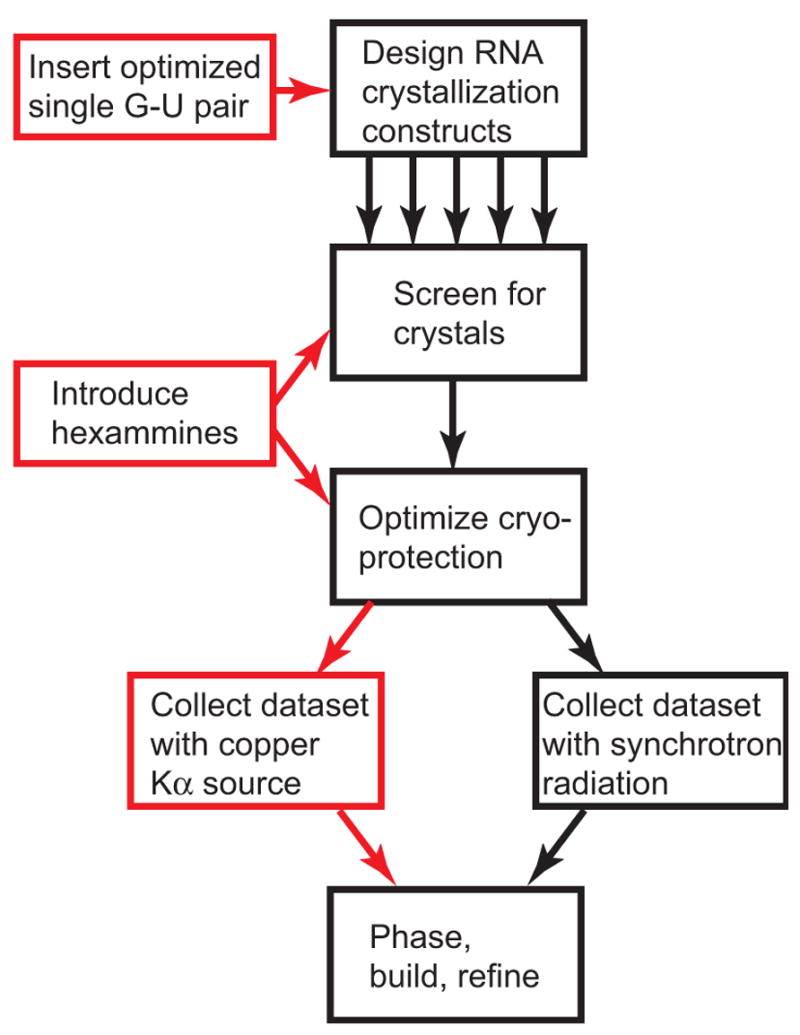

The phasing method we present here is essentially constructed from two pieces of knowledge: G·U pairs can bind cations in the major groove (Cate and Doudna, 1996; Colmenarejo and Tinoco, 1999; Kieft and Tinoco, 1997; Masquida and Westhof, 2000; Montange and Batey, 2006; Stefan et al., 2006; Varani and McClain, 2000) and hexammine complexes provide good heavy atom derivatives of RNA crystals for phasing (Batey et al., 2004; Cate et al., 1996b; Cochrane et al., 2007; Kazantsev et al., 2005; Montange and Batey, 2006; Pfingsten et al., 2006). However, before this knowledge could be used, the detailed rules that govern binding in different versions of the motif had to be explored and the optimal sequence discovered. Now, the phasing strategy presented here can be integrated fully into existing RNA crystallography methodology (Figure 6). Because current RNA crystallization strategies employ systematic variation of the RNA construct guided by biochemical and functional studies to yield a library of RNA to be screened for crystals (Cate and Doudna, 2000; Golden, 2007; Golden and Kundrot, 2003; Ke and Doudna, 2004; Wedekind and McKay, 2000), the most useful way to use this method is to anticipate the need for a derivative at the initial stages of RNA construct design and insert the optimal G·U motif into one or more helices of all RNAs made. When crystals are obtained, the heavy atom derivative is prepared by adding ~5 mM of hexammine ion to the crystal during cryo-protection, or co-crystallizing the RNA and hexammine. The commercial availability and low cost of cobalt (III) hexammine chloride allows it to be a standard reagent in crystallization trials. For high salt conditions, the method of moving the crystals to an acetate salt and 100–150 mM hexammine acetate can be attempted. Hence, in this integrated approach there is no separate step of synthesizing or purifying derivatized RNA, of mutating or altering the RNA, or of soaking in a variety of different heavy atoms, and only minor re-optimization of crystallization conditions may be necessary.

Figure 6. Flowchart of the phasing strategy integrated into existing RNA crystallography methods.

Black boxes represent a standard methodology for producing diffracting RNA crystals and solving their structures, starting with design and purification of many different variants for use in crystallization screens. Our method integrates into this pathway (red boxes) without adding additional steps.

The integrated strategy can be extended to obtain phase information “at-home” using crystals that contain the single G·U motif and either cobalt (III) hexammine or cesium. If a usable map is obtained, building of the structure can begin. Even if a usable map is not obtained, the presence of specifically bound heavy atoms can be detected from the anomalous signal, the location of the sites may be obtained, and the likelihood of success using iridium (III) hexammine and synchrotron radiation can be assessed.

The size of a given RNA and the availability of appropriate helices will place constraints on the number of sites that can be introduced into the RNA. However, the potential usefulness of introducing even a small number of high-occupancy heavy atom sites is illustrated by the SAM-1 riboswitch structure (Montange and Batey, 2006). In this 30.5 kD RNA, one strong engineered iridium (III) hexammine site and three weak fortuitous sites were sufficient to yield an interpretable map. Similar results were observed with the structure of the ribosome binding domain of an IRES RNA (Pfingsten et al., 2006). These observations lead us to hypothesize that a strong, highly occupied site can provide the “anchor” for finding other weaker naturally-occurring sites. In all of the structures we have solved using this method, fortuitous lower-occupancy sites in the RNA helped phase, but in many cases these sites are weak enough (occupancy <0.4) that they may not work on their own. Support for this idea comes from examining the experimental and predicted Patterson maps of the SAM-1 riboswitch iridium (III) hexammine derivatives (Supplemental Figure S3). In the absence of a strong site, peaks from a collection of weaker sites (occupancy = 0.4) recede into the noise, but when a strong site is present (occupancy = 1) all peaks become usable. The number of sites needed to solve a given RNA structure is likely to depend on the RNA size, the heavy atom used, the X-ray source (Cu-Kα/synchrotron), and the experimental method (SAD/MAD/SIRAS).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Crystallization chassis RNA preparation

All sixteen PM constructs were cloned from a plasmid containing the sequence for the wildtype E. coli SRP RNA that was crystallized previously (Batey et al., 2000; Batey et al., 2001). Sequences were inserted into a pUC19 vector with a hepatitis δ ribozyme at the 3′ end and a hammerhead ribozyme at the 5′ end to ensure homogeneity (Ferre-D’Amare and Doudna, 1996). DNA templates for transcription were generated by PCR from these plasmids and used in transcription reactions using T7 RNA polymerase. The conditions were: 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.1), 1 mM spermidine, 5 mM dithiothreitol, 0.01% Triton X-100, 60 mM MgCl2, 8 mM each ribonucleotide triphosphate (pH adjusted to 8.0) and 0.04 mg/ml T7 RNA polymerase. The reactions incubated at 37 °C overnight, then were placed at 65 °C for 5 min to ensure complete cleavage of the ribozymes. The reaction was then precipitated by adding 4 volumes of ice cold 100% ethanol. The resulting pellet was resuspended in 4.5 M urea loading buffer. The RNA was purified by gel electrophoresis on a 10% denaturing polyacrylamide gel in 1X TBE buffer. The band containing the RNA was visualized by UV-shadowing, excised from the gel, crushed, and allowed to elute into RNase-freeH2O overnight, with shaking at 4°C. The gel pieces were filtered out of the solution using a 0.22 μm filter(Nalgene). The RNA then was concentrated using a centrifugal filter with a 10,000 molecular weight cutoff (Amicon).

Crystallization of the “crystallization chassis”

E. coli M-domain protein was prepared as described (Batey et al., 2000; Batey et al., 2001). For each RNA construct, the exact amount of M-domain protein needed for crystallization was determined using a native gel electrophoresis assay as described (Batey et al., 2001). Briefly, RNA at 30–40 μM was titrated with varying dilutions of protein in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 100 mM KCl, 1mM dithiotreitol, and 50 mM NaCl. The reaction was allowed to incubate for 20 minutes, and then electrophoresed through 8% native polyacrylamide gels with 0.5X TBE and 2 mM MgCl2. The gels were run at 7 W for 1 hour and stained with ethidium bromide to visualize the free RNA and RNA protein complex. From the native gels, amount of protein needed to achieve 1:1 stoichiometry was determined. A molar ratio of 0.98:1 protein:RNA was then combined to form the RNA-protein complexes for crystallography. The complex was denatured with 1 mL of 8 M urea, then dialyzed against 10 mM K-HEPES (pH 7.5) overnight at 4°C. The complex was concentrated in a 10,000 MWCO microconcentrator (Amicon) to approximately 700 μM. Crystals were grown by vapor diffusion with sitting drops at 20°C using 2 μL of the renatured protein-RNA complex and 2 μL of the reservoir solution which contained 8–13% isopropanol, 50 mM Na-MES (pH 5.6), 200 mM KCl, and 3–6 mM cobalt (III) hexammine. Crystals grew in 1–3 days and were cryoprotected by gradually moving the crystals into crystallization solution + 30% (v/v) MPD, then cryo-cooled in liquid nitrogen.

Crystallization chassis data collection, processing

Diffraction data for all constructs were collected using a rotating anode copper X-ray source and Raxis IV++ detector (Rigaku-MSC) under cryo-conditions. We collected a full 360° of data in 30° wedges using an inverse beam strategy with an oscillation width of 1° per frame. Exposure times were from 10–20 minutes per frame. Data were indexed, integrated, and scaled using d*trek (Pflugrath, 1999) and converted to files suitable for use in CNS (Brunger et al., 1998).

Crystallization chassis molecular replacement and structure refinement

Model phases were obtained for each dataset using the wild-type SRP/M-domain complex (PDB #1DUL) (Batey et al., 2000) with all cations removed as a search model for molecular replacement with the program CNS (Brunger et al., 1998). For each complex, an unambiguous solution was found and the resultant electron density maps contained clear density for the cobalt (III) hexammines, and these were added manually to the model. The identity and location of the cobalt (III) hexammines were confirmed using anomalous difference Fourier maps calculated in CNS (Brunger et al., 1998) as shown in figure 2. The model then was changed to introduce the correct G·U pair sequence and the RNA/protein/hexammine model was refined in CNS using iterative rounds of simulated annealing, energy minimization, and B-factor refinement (Brunger et al., 1998).

Phasing of SRP RNA/M-domain complex using Cu Kα radiation

Experimental phases were obtained by integrating and scaling the data from crystal PM15 in HKL2000 (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997). Scaling was done with the “no merge original index” macro enabled. The raw data were used with the AUTOSOL SAD function of the program PHENIX (Adams et al., 2004; Adams et al., 2002), with thorough density modification (solvent content set at 0.5) and the data flagged as “weak.” This procedure located 12 heavy-atom sites (overall FOM = 0.21).

Preparation of iridium (III) hexammine chloride

The iridium hexammine was prepared according to methods outlined in the literature (Cruse et al., 2001; Galsbøl and Simonsen, 1990). Two grams iridium chloride (IrCl3) (Aldrich) and 35 mL ammonium hydroxide were added to a heavy-walled ACE pressure tube (Aldrich) (Cruse et al., 2001). The tube was then sealed and incubated in a 150°C silicone oil bath for four days (Cruse et al., 2001; Galsbøl and Simonsen, 1990). The reaction then was allowed to completely cool and incubated on slushy ice. The clear, light brown solution then was filtered and evaporated to dryness under vacuum. While evaporating, the solution was heated to 50°C using a water bath (Galsbøl and Simonsen, 1990). The resulting solid then was resuspended in 5 mL of water and transferred to a 50 mL conical tube. Two mL of concentrated HCl then was added to the solution. Precipitate was spun down in a centrifuge and the light yellow supernatant was discarded. Pellet was washed three times with 10 mL of a 2:1 (v/v) water:conc. HCl solution by vigorous vortexing followed by centrifugation. Supernatant was discarded after each wash. The pellet was then washed three times in absolute ethanol, air-dried and resuspended in ~ 3 mL ddH2O (Cruse et al., 2001). Solution was centrifuged one more time to remove insoluble material. The resulting supernatant should show a clear absorbance maxima at 251 nm and concentration can be calculated using the extinction coefficient 92 M−1cm−1 at 251 nm (Galsbøl and Simonsen, 1990). Typical yield is 50%. Supernatant then was aliquoted into fresh Eppendorf tubes and stored at −20°C.

Preparation of hexammine acetates from chloride salts

Cobalt (III) hexammine acetate was prepared from cobalt (III) hexammine chloride (Sigma) using a simple precipitation procedure. 0.6675 g of the hexammine chloride was dissolved in 25 mL water (100 mM) in a 50 mL conical tube and to this was added 1.42 g lead acetate (Sigma) dissolved in 5 mL water. The lead chloride immediately precipitated, and the solution was allowed to sit for 30 minutes to ensure complete precipitation. The precipitated material was spun down and the supernatant (containing dissolved hexammine acetate) was removed and concentration/crystallized by passive evaporation. The hexammine acetate was harvested by dissolving the crystals in 5mL of water, yielding a stock solution of 500 mM cobalt (III) hexammine acetate.

Iridium (III) hexammine was prepared by adding 0.0535 grams of lead acetate to 0.5 mL of 188 mM iridium (III) hexammine chloride and mixing well. The resultant solution was allowed to sit on the bench for 30 minutes, after which time the precipitated lead chloride was spun down in a microcentrifuge and the hexammine acetate salt solution was removed. The solution then was concentrated by passive evaporation in a crystallization tray and the dry crystals were collected and stored at −20°C until use.

Transfer of crystals into high salt/high hexammine conditions

The “high salt” RNA crystals described in the text grew in 1.4 M Li2SO4, 40 mM MgAcetate, 50 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5, 0.5 mM spermidine-HCl via vapor diffusion/hanging drop (Costantino et al., in preparation). To transfer these crystals into the acetate salt, the crystals first were stabilized by replacing the well solution with 2.0 M Li2SO4, 40 mM MgAcetate, 50 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5, 0.5 mM spermidine-HCl. The well was resealed and the crystallization drop allowed to equilibrate overnight. The crystals were then transferred to a soaking tray containing 50 microliters of 2.0 M Li2SO4, 40 mM MgAcetate, 50 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5, 0.5 mM spermidine-HCl (well solution). The crystals were allowed to sit undisturbed for 10 minutes, at which time 50 microliters of solution “10%” was added to the soak. Solution “10%” contained 90 microliters of well solution + 10 microliters of 3.0 M lithium acetate, 40 mM MgAcetate, 50 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5, 0.5 mM spermidine-HCl, 100 mM iridium hexammine acetate (derivative solution). The crystals soaked for 10 minutes, at which time 50 microliters of the soaking solution were removed and 50 microliters of solution “20%” was added (“20%” = 80 microliters well solution +20 microliters derivative solution) and the crystal was allowed to soak for 10 minutes. This process was repeated as the concentration of derivative solution was stepped up in 10 % increments, until the crystals had been moved into 100% derivative solution. The crystals were washed several times with this solution before soaking for 1 additional hour, then were cryo-cooled directly in liquid nitrogen.

High-salt crystal data collection, processing, and phasing

The details of this structure and its determination will be presented in another manuscript (Costantino et al. in preparation).

Cesium-derivatized crystal data collection, processing, and phasing

The details of this structure and its determination will be presented in another manuscript (Gilbert et al. in preparation).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank members of their labs for useful discussions. We would like to thank D. Costantino, J. Pfingsten, S. Gilbert, A. Edwards and C. Stoddard for critical reading of this manuscript, and C. Hackbarth for initiating this project during his rotation in the Kieft Lab. We would also like to acknowledge J. Hammond and D. Costantino for cloning assistance. This project was funded by National Institutes of Health Grants AI072187 and GM072560 (J.S.K) and a Scientist Development Grant from the American Heart Association (R.T.B.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams PD, Gopal K, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Hung LW, Ioerger TR, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Pai RK, Read RJ, Romo TD, et al. Recent developments in the PHENIX software for automated crystallographic structure determination. J Synchrotron Radiat. 2004;11:53–55. doi: 10.1107/s0909049503024130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams PD, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Hung LW, Ioerger TR, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Read RJ, Sacchettini JC, Sauter NK, Terwilliger TC. PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58:1948–1954. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batey RT, Doudna JA. Structural and energetic analysis of metal ions essential to SRP signal recognition domain assembly. Biochemistry. 2002;41:11703–11710. doi: 10.1021/bi026163c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batey RT, Gilbert SD, Montange RK. Structure of a natural guanine-responsive riboswitch complexed with the metabolite hypoxanthine. Nature. 2004;432:411–415. doi: 10.1038/nature03037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batey RT, Rambo RP, Lucast L, Rha B, Doudna JA. Crystal structure of the ribonucleoprotein core of the signal recognition particle. Science. 2000;287:1232–1239. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5456.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batey RT, Sagar MB, Doudna JA. Structural and energetic analysis of RNA recognition by a universally conserved protein from the signal recognition particle. J Mol Biol. 2001;307:229–246. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baugh C, Grate D, Wilson C. 2.8 A crystal structure of the malachite green aptamer. J Mol Biol. 2000;301:117–128. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt G, Carrasco N, Huang Z. Efficient substrate cleavage catalyzed by hammerhead ribozymes derivatized with selenium for X-ray crystallography. Biochemistry. 2006;45:8972–8977. doi: 10.1021/bi060455m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco N, Buzin Y, Tyson E, Halpert E, Huang Z. Selenium derivatization and crystallization of DNA and RNA oligonucleotides for X-ray crystallography using multiple anomalous dispersion. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1638–1646. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cate JH, Doudna JA. Metal-Binding Sites in the Major Groove of a Large Ribozyme Domain. Structure. 1996;4:1221–1229. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00129-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cate JH, Doudna JA. Solving large RNA structures by X-ray crystallography. Methods Enzymol. 2000;317:169–180. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)17014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cate JH, Gooding AR, Podell E, Zhou K, Golden BL, Kundrot CE, Cech TR, Doudna JA. Crystal structure of a group I ribozyme domain: principles of RNA packing. Science. 1996a;273:1678–1685. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5282.1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong HK, Hwang E, Lee C, Choi BS, Cheong C. Rapid preparation of RNA samples for NMR spectroscopy and X-ray crystallography. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e84. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane JC, Lipchock SV, Strobel SA. Structural investigation of the GlmS ribozyme bound to Its catalytic cofactor. Chem Biol. 2007;14:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colmenarejo G, Tinoco I., Jr Structure and thermodynamics of metal binding in the P5 helix of a group I intron ribozyme. J Mol Biol. 1999;290:119–135. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correll CC, Freeborn B, Moore PB, Steitz TA. Use of chemically modified nucleotides to determine a 62-nucleotide RNA crystal structure: a survey of phosphorothioates, Br, Pt and Hg. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 1997;25:165–172. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1997.10508183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruse W, Saludjian P, Neuman A, Prange T. Destabilizing effect of a fluorouracil extra base in a hybrid RNA duplex compared with bromo and chloro analogues. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2001;57:1609–1613. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901012318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauter Z. New approaches to high-throughput phasing. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2002;12:674–678. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(02)00372-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dauter Z, Adamiak DA. Anomalous signal of phosphorus used for phasing DNA oligomer: importance of data redundancy. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2001;57:990–995. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901006382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doublie S. Preparation of selenomethionyl proteins for phase determination. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:523–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doudna JA. Structural genomics of RNA. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7(Suppl):954–956. doi: 10.1038/80729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennifar E, Walter P, Dumas P. A crystallographic study of the binding of 13 metal ions to two related RNA duplexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2671–2682. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferre-D’Amare AR, Doudna JA. Use of Cis- and Trans-Ribozymes to Remove 5′ and 3′ Heterogeneities From Milligrams of in Vitro Transcribed Rna. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:977–978. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.5.977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferre-D’Amare AR, Doudna JA. Crystallization and structure determination of a hepatitis delta virus ribozyme: use of the RNA-binding protein U1A as a crystallization module. J Mol Biol. 2000;295:541–556. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferre’-D’Amare’ AR, Zhou K, Doudna JA. Crystal Structure of a Hepatitis Delta Virus Ribozyme. Nature. 1998;395:567–574. doi: 10.1038/26912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galsbøl FH, Simonsen K. The Preparation, Separation and Characterization of some Ammine Complexes or Iridium(III) Acta Chem Scand. 1990;44:796–801. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert SD, Montange RK, Stoddard CD, Batey RT. Structural Studies of the Purine and SAM Binding Riboswitches. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2006;71:259–268. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2006.71.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden BL. Heavy atom derivatives of RNA. Methods Enzymol. 2000;317:124–132. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)17010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden BL. Preparation and crystallization of RNA. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;363:239–257. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-209-0_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden BL, Gooding AR, Podell ER, Cech TR. X-ray crystallography of large RNAs: heavy-atom derivatives by RNA engineering. RNA. 1996;2:1295–1305. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden BL, Kundrot CE. RNA crystallization. J Struct Biol. 2003;142:98–107. doi: 10.1016/s1047-8477(03)00042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guncar G, Wang CI, Forwood JK, Teh T, Catanzariti AM, Ellis JG, Dodds PN, Kobe B. The use of Co2+ for crystallization and structure determination, using a conventional monochromatic X-ray source, of flax rust avirulence protein. Acta Crystallograph Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2007;63:209–213. doi: 10.1107/S1744309107004599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson WA, Horton JR, LeMaster DM. Selenomethionyl proteins produced for analysis by multiwavelength anomalous diffraction (MAD): a vehicle for direct determination of three-dimensional structure. EMBO J. 1990;9:1665–1672. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08287.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobartner C, Micura R. Chemical synthesis of selenium-modified oligoribonucleotides and their enzymatic ligation leading to an U6 SnRNA stem-loop segment. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:1141–1149. doi: 10.1021/ja038481k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobartner C, Rieder R, Kreutz C, Puffer B, Lang K, Polonskaia A, Serganov A, Micura R. Syntheses of RNAs with up to 100 nucleotides containing site-specific 2′-methylseleno labels for use in X-ray crystallography. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:12035–12045. doi: 10.1021/ja051694k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Sheng J, Carrasco N, Huang Z. Selenium derivatization of nucleic acids for crystallography. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:477–485. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazantsev AV, Krivenko AA, Harrington DJ, Holbrook SR, Adams PD, Pace NR. Crystal structure of a bacterial ribonuclease P RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:13392–13397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506662102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke A, Doudna JA. Crystallization of RNA and RNA-protein complexes. Methods. 2004;34:408–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2004.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieft JS, Batey RT. A general method for rapid and nondenaturing purification of RNAs. RNA. 2004;10:988–995. doi: 10.1261/rna.7040604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieft JS, Tinoco I., Jr Solution structure of a metal-binding site in the major groove of RNA complexed with cobalt (III) hexammine. Structure. 1997;5:713–721. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(97)00225-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieft JS, Zhou K, Grech A, Jubin R, Doudna JA. Crystal structure of an RNA tertiary domain essential to HCV IRES-mediated translation initiation. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:370–374. doi: 10.1038/nsb781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim I, McKenna SA, Viani Puglisi E, Puglisi JD. Rapid purification of RNAs using fast performance liquid chromatography (FPLC) RNA. 2007;13:289–294. doi: 10.1261/rna.342607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindholm RD. Hexamminecobalt(III) Salts. Inorganic Syntheses. 1978;18:67–69. [Google Scholar]

- Lukavsky PJ, Puglisi JD. Large-scale preparation and purification of polyacrylamide-free RNA oligonucleotides. RNA. 2004;10:889–893. doi: 10.1261/rna.5264804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martick M, Scott WG. Tertiary contacts distant from the active site prime a ribozyme for catalysis. Cell. 2006;126:309–320. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masquida B, Westhof E. On the wobble GoU and related pairs. RNA. 2000;6:9–15. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200992082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal K, Gupta MN. The affinity concept in bioseparation: evolving paradigms and expanding range of applications. Biomol Eng. 2006;23:59–76. doi: 10.1016/j.bioeng.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montange RK, Batey RT. Structure of the S-adenosylmethionine riboswitch regulatory mRNA element. Nature. 2006;441:1172–1175. doi: 10.1038/nature04819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-Ray Diffraction Data Collected in Oscillation Mode. Methods in Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfingsten JS, Costantino DA, Kieft JS. Structural basis for ribosome recruitment and manipulation by a viral IRES RNA. Science. 2006;314:1450–1454. doi: 10.1126/science.1133281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pflugrath JW. The finer things in X-ray diffraction data collection. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1999;55:1718–1725. doi: 10.1107/s090744499900935x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson MP, Scott WG. The structural basis of ribozyme-catalyzed RNA assembly. Science. 2007;315:1549–1553. doi: 10.1126/science.1136231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupert PB, Ferre-D’Amare AR. Crystal structure of a hairpin ribozyme-inhibitor complex with implications for catalysis. Nature. 2001;410:780–786. doi: 10.1038/35071009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salon J, Sheng J, Jiang J, Chen G, Caton-Williams J, Huang Z. Oxygen replacement with selenium at the thymidine 4-position for the se base pairing and crystal structure studies. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:4862–4863. doi: 10.1021/ja0680919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng J, Jiang J, Salon J, Huang Z. Synthesis of a 2′-Se-thymidine phosphoramidite and its incorporation into oligonucleotides for crystal structure study. Org Lett. 2007;9:749–752. doi: 10.1021/ol062937w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefan LR, Zhang R, Levitan AG, Hendrix DK, Brenner SE, Holbrook SR. MeRNA: a database of metal ion binding sites in RNA structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D131–134. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock AM, Mottonen JM, Stock JB, Schutt CE. Three-dimensional structure of CheY, the response regulator of bacterial chemotaxis. Nature. 1989;337:745–749. doi: 10.1038/337745a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun DP, Alber T, Bell JA, Weaver LH, Matthews BW. Use of site-directed mutagenesis to obtain isomorphous heavy-atom derivatives for protein crystallography: cysteine-containing mutants of phage T4 lysozyme. Protein Eng. 1987;1:115–123. doi: 10.1093/protein/1.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varani G, McClain WH. The G x U wobble base pair. A fundamental building block of RNA structure crucial to RNA function in diverse biological systems. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:18–23. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedekind JE, McKay DB. Purification, crystallization, and X-ray diffraction analysis of small ribozymes. Methods Enzymol. 2000;317:149–168. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)17013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.