Abstract

Background/Aims

Although the antiviral and histological benefits of peginterferon/ribavirin therapy are well established, the effects on health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and sexual health are less certain. This study assessed HRQOL and sexual health in patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis in the HALT-C Trial.

Methods

Subjects completed SF-36 and sexual health questionnaires prior to and after 24 weeks of peginterferon/ribavirin therapy (n = 1144). Three hundred and seventy-three (33%) subjects were HCV RNA negative at week 20 and continued therapy through week 48; 258 were seen at week 72. One hundred and eighty achieved sustained virological responses (SVR) and 78 relapsed.

Results

At baseline, patients had poorer scores for all eight SF-36 domains compared to healthy controls. Patients with cirrhosis had lower HRQOL scores than those with bridging fibrosis, as did patients with higher depression scores. SVR patients had significant improvements in seven domains, whereas relapsers had significant worsening in one domain. Sexual scores improved in SVR patients and decreased in relapsers (p = 0.03). In multivariate analyses, improvements in HRQOL and sexual scores were significantly associated with SVR but were less striking in patients with lower depression scores.

Conclusions

Achievement of SVR after peginterferon/ribavirin therapy improves HRQOL and sexual health in chronic hepatitis C patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis.

Keywords: Cirrhosis, Fibrosis, Health-related quality of life, Hepatitis, Viral type C, Sexual functioning, Sustained virological response

1. Introduction

Chronic hepatitis C affects at least 3.2 million Americans and is the major cause of chronic liver disease, cirrhosis and liver cancer in the United States [1,2]. Chronic viral hepatitis is typically silent; symptoms and signs are present only in those with severe or advanced disease. Importantly, symptoms and poor health-related quality of life (HRQOL) are not reliable in separating patients with mild from those with moderate or advanced disease [3]. In some patients, symptoms do not develop until the onset of advanced cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma. Other patients have marked fatigue and weakness, despite having histologically mild or early disease.

Chronic hepatitis C therapies are available and effective in approximately half of selected patients [4]. Because of its expense and many side effects, therapy is usually reserved for patients who have evidence of progressive disease [5,6]. The poor correlation of symptoms, signs, and liver test abnormalities with severity and stage of disease has led to the use of liver biopsy and staging of fibrosis as the major criterion for therapy. Furthermore, eradication of hepatitis C virus (HCV) and prevention of disease progression, rather than amelioration of symptoms or improvement in HRQOL, have been used as the major determinants of successful therapy. Indeed, in most trials of therapy of hepatitis C, symptoms and HRQOL are not mentioned as even secondary endpoints [7–10]. Nevertheless, a few prospective studies have shown that a sustained virological response (SVR) to therapy of chronic hepatitis C can be associated with significant improvements in HRQOL [11–15]. The role of contemporary therapy of chronic hepatitis C in ameliorating symptoms and improving HRQOL, especially in advanced liver disease, is not well defined [16–18].

We evaluated HRQOL and sexual health prospectively in a cohort of patients with advanced chronic hepatitis C who had failed to respond to a previous course of interferon-α (with or without ribavirin) enrolled in the lead-in phase of the Hepatitis C Antiviral Long-term Treatment against Cirrhosis (HALT-C) Trial. Patients were re-treated with a 24-week “lead-in” course of peginterferon α-2a and ribavirin [19,20]. Patients who responded continued treatment for a full 48 weeks and were followed for another 24 weeks to assess whether they achieved SVR [19,20]. The aim of the current analysis was to identify correlates of impaired HRQOL at enrollment. Secondary aims included evaluation of changes in HRQOL and sexual health in the subset of patients who achieved an SVR and those who had a transient response (relapsers).

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Patients

HALT-C trial patients had chronic hepatitis C with detectable HCV RNA in serum and, within 12 months of enrollment, had undergone liver biopsy that demonstrated bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis (Ishak fibrosis scores of 3–6) [21]. Reasons for exclusion included evidence of hepatic decompensation, other co-existent liver disorder, serious medical disorders that would preclude treatment with interferon, interferon intolerance, active use of illicit drugs, active alcohol abuse, a suicide attempt or hospitalization for depression within the past 5 years, and history of a severe or uncontrolled psychiatric condition within the past 6 months.

After a thorough baseline evaluation, patients were re-treated with peginterferon α-2a (180 μg per week: Pegasys™: Roche Pharmaceuticals) and ribavirin (1000–1200 mg per day: Copegus™: Roche). Patients who failed to clear serum HCV RNA by week 20 met the criterion for non-response and were randomized at week 24 to receive lower dose peginterferon α-2a (90 mcg weekly) or no therapy for 3½ years. Patients who were HCV RNA negative at week 20 continued higher dose peginterferon and ribavirin therapy for 48 weeks and then were followed for 24 weeks to assess whether an SVR occurred. This study was approved by all relevant local Institutional Review Boards and an external Data Safety Monitoring Board appointed by the National Institutes of Health. All patients gave written, informed consent.

Standard demographic, clinical, medication, laboratory, and radiological data were obtained at ten clinical centers. Self-administered HRQOL forms and the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI) [22,23] were completed. Data were entered into a central database maintained by the Data Coordinating Center (New England Research Institutes, Watertown, MA). Although the HALT-C Trial is not a blinded study, study design rules preclude analysis of group data on patients in the randomized phase of the study until the randomization phase is completed.

2.2. Health questionnaires

HRQOL was assessed with the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) [24], a 36-item self-administered questionnaire encompassing eight physical and mental health domains and two physical and mental summary scales [25]. The SF-36 has demonstrated consistently high reliability and validity in a variety of patient populations [24,26–29]. SF-36 scales have been used to evaluate change in health-status over time in several studies [30–33], including therapeutic trials of chronic hepatitis C [7,12,13,15,17,18,34–39].

Three additional questions (see Appendix A) that addressed self-reported sexual functioning, desire, and satisfaction were hypothesized to measure sexual effects of chronic hepatitis C and its treatment. Correlation of this Sexual Summary Scale score with the Beck Depression Inventory II item “Loss of Interest in Sex” was high (Pearson correlation coefficient = −0.603, p < 0.0001) [22,23].

A semi-quantitative estimate of lifetime alcohol consumption was obtained using an adaptation of the Skinner survey [40–42]. Three neuropsychiatrists reviewed the composition of all concomitant prescription medications used by study patients and, from the drugs used, inferred indications for their use.

2.3. Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS (Statistical Analysis Software, version 8.2, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). When data were missing on an SF-36 item, a patient-specific mean scale score was substituted if at least 50% of the items in the scale were completed [24]. The Sexual Summary Scale was calculated as the mean of all completed items in the scale. Change in HRQOL was calculated by subtracting the patient’s baseline score for each scale from the week 72 score. The results of HALT-C SF-36 scores were compared to a general population sample of 750 healthy controls [43]. This Well-Norm group was selected by excluding those who reported such chronic diseases as congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, recent myocardial infarction, angina, cancer, chronic allergies, arthritis, chronic back problems, and chronic lung disease. The average age (±SD) of the Well-Norm group was 40.2 ± 15.3 years; 53.5% were female [11].

Univariate t-tests were used to identify variables that were significantly different between the groups. Paired t-tests were used to compare changes in HRQOL scores from baseline to week 72. Linear multivariate regression models were constructed to identify factors that independently and significantly predicted summary physical, mental, and sexual scores at baseline and improvements in these scores following therapy.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics of cohort

As shown in Fig. 1, among the 1145 patients enrolled in the lead-in phase of the HALT-C Trial, 1144 completed the baseline HRQOL questionnaire. Selected demographic and clinical features of the patients are provided in Table 1. Average age was 50 years, 28% were women, approximately three-quarters were non-Hispanic whites, and 15% were blacks. According to self-reports, 17% of patients had diabetes mellitus, 14% had heart disease, and 8% had depression. One-third of patients (31%) were taking antidepressant or anxiolytic medications at baseline. Although most patients had previously used alcohol (84%), the majority (81%) reported no longer drinking at baseline.

Fig. 1.

Overview of HALT-C Trial: HRQOL assessments at baseline and week 72.

Table 1.

Selected demographic and historical features of patients studied

| All patients (n = 1144) | Patients with baseline physical summary score

|

|||

| >50 points (n = 490) | ≤50 points (n = 654) | p valuea | ||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (y), mean (±SD) | 49.9 (±7.30) | 49.4 (±7.07) | 50.3 (±7.46) | 0.06 |

| Gender (% female) | 28% | 17% | 36% | <0.0001 |

| Marital status (% married or living as married) | 71% | 78% | 65% | <0.0001 |

| Education level (% college graduate) | 26% | 34% | 21% | <0.0001 |

| Race and ethnicity (%) | ||||

| White | 74% | 78% | 71% | 0.01 |

| Black | 15% | 11% | 18% | 0.0009 |

| Hispanic | 8% | 8% | 9% | 0.65 |

| Other race/ethnicity | 3% | 3% | 2% | 0.24 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), mean (±SD) | 29.7 (±5.42) | 28.4 (±4.36) | 30.7 (±5.91) | <0.0001 |

| Medical disorders (self-reported) | ||||

| History of diabetes mellitus (% yes) | 17% | 12% | 20% | 0.0001 |

| History of serious or other heart disease (% yes) | 14% | 11% | 16% | 0.008 |

| History of cholesterol medication use (% yes) | 3% | 2% | 4% | 0.30 |

| History of major depression (% yes) | 8% | 3% | 11% | <0.0001 |

| Anxiolytic/antidepressant use at baseline (% yes) | 31% | 16% | 42% | <0.0001 |

| Beck Depression Inventory score (range 0–63) | 7.43 (±7.43) | 3.61 (±4.20) | 10.28 (±8.02) | <0.0001 |

| Hepatitis factors | ||||

| HCV genotype 1 (%) | 89% | 90% | 88% | 0.48 |

| Ever received a transfusion (% yes) | 39% | 36% | 42% | 0.08 |

| Ever experienced a needle stick (% yes) | 19% | 18% | 19% | 0.68 |

| Ever used needles to inject recreational drugs (% yes) | 47% | 46% | 47% | 0.73 |

| Ever exposed to blood at work (% yes) | 24% | 21% | 25% | 0.11 |

| No exposures reported (%) | 14% | 17% | 13% | 0.04 |

| Platelet count (×10−3/mm3), mean (±SD) | 169 (±64.8) | 171 (±60.4) | 168 (±68.0) | 0.39 |

| Palpable spleen on baseline exam (% yes) | 11% | 10% | 12% | 0.26 |

| Baseline biopsy Ishak fibrosis score, mean (±SD) | 4.0 (±1.3) | 3.8 (±1.2) | 4.2 (±1.3) | <0.0001 |

| Cirrhosis on biopsy [Ishak score 5 or 6] (%) | 38% | 31% | 43% | <0.0001 |

| HCV RNA level at baseline (loge of IU/ml), mean (±SD) | 6.42 (±0.53) | 6.43 (±0.54) | 6.41 (±0.52) | 0.62 |

| ALT level at baseline (U/L), mean (±SD) | 115 (±82.2) | 125 (±86.8) | 108 (±78.0) | 0.0007 |

| Smoking and alcohol use | ||||

| Ever drank alcohol regularly? (% yes) | 84% | 87% | 82% | 0.04 |

| Number of alcoholic drinks over lifetime (±SD) | 18,390 (±30,721) | 15,281(±26,109) | 20,721(±33,601) | 0.003 |

| Regular alcohol use at baseline (% yes) | 19% | 22% | 16% | 0.006 |

| Ever smoked cigarettes? (% yes) | 76% | 75% | 78% | 0.26 |

| Current smoking at baseline (% yes) | 30% | 24% | 34% | 0.0002 |

| Patients with baseline mental summary score

|

||||

| >50 points (n = 718) | ≤50 points (n = 426) | p valuea | ||

|

| ||||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (y), mean (±SD) | 50.0 (±7.56) | 49.7 (±6.85) | 0.52 | |

| Gender (% female) | 25% | 31% | 0.03 | |

| Marital status (% married or living as married) | 75% | 64% | <0.0001 | |

| Education level (% college graduate) | 30% | 19% | <0.0001 | |

| Race and ethnicity (%) | ||||

| White | 74% | 73% | 0.79 | |

| Black | 16% | 14% | 0.22 | |

| Hispanic | 7% | 11% | 0.02 | |

| Hispanic | 3% | 2% | 0.65 | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2), mean (±SD) | 29.6 (±5.28) | 29.9 (±5.65) | 0.49 | |

| Medical disorders (self-reported) | ||||

| History of diabetes mellitus (% yes) | 15% | 19% | 0.11 | |

| History of serious or other heart disease (% yes) | 14% | 13% | 0.65 | |

| History of cholesterol medication use (% yes) | 3% | 3% | 0.73 | |

| History of major depression (% yes) | 5% | 13% | <0.0001 | |

| Anxiolytic/antidepressant use at baseline (% yes) | 23% | 45% | <0.0001 | |

| Beck Depression Inventory score (range 0–63) | 4.22 (±4.09) | 12.82 (±8.59) | <0.0001 | |

| Hepatitis factors | ||||

| HCV genotype 1 (%) | 90% | 87% | 0.14 | |

| Ever received a transfusion (% yes) | 40% | 39% | 0.72 | |

| Ever experienced a needle stick (% yes) | 19% | 18% | 0.51 | |

| Ever used needles to inject recreational drugs (% yes) | 44% | 52% | 0.01 | |

| Ever exposed to blood at work (% yes) | 23% | 24% | 0.64 | |

| No exposures reported (%) | 16% | 12% | 0.03 | |

| Platelet count (×10−3/mm3), mean (±SD) | 172 (±65.6) | 165 (±63.3) | 0.07 | |

| Palpable spleen on baseline exam (% yes) | 10% | 13% | 0.16 | |

| Baseline biopsy Ishak fibrosis score, mean (±SD) | 3.9 (±1.3) | 4.2 (±1.3) | 0.002 | |

| Cirrhosis on biopsy [Ishak score 5 or 6] (%) | 35% | 42% | 0.02 | |

| HCV RNA level at baseline (loge of IU/ml), mean (±SD) | 6.44 (±0.54) | 6.39 (±0.52) | 0.17 | |

| ALT level at baseline (U/L), mean (±SD) | 115 (±80.4) | 115 (±85.3) | 0.99 | |

| Smoking and alcohol use | ||||

| Ever drank alcohol regularly? (% yes) | 83% | 86% | 0.23 | |

| Number of alcoholic drinks over lifetime (±SD) | 15,892 (±29,630) | 22,619 (±32,081) | 0.0003 | |

Table 1 presents comparison of patients with baseline physical and mental summary scores above and below the 50 point mark, which represents the average summary score in the US population [25]. A majority of the cohort (57%) had baseline physical summary scores ≤50. These patients were significantly more likely to be women, unmarried, non-college graduates, black, current smokers, and current abstainers from alcohol; to have a history of diabetes, heart disease, and/or depression; and to have cirrhosis and lower ALT levels than those with baseline physical summary scores >50 points. One-third of the cohort (37%) had baseline mental summary scores ≤50. These patients were significantly more likely to be women, unmarried, non-college graduates, Hispanic, current smokers, and current abstainers from alcohol; to have a history of depression and injection drug use; and to have cirrhosis than those with baseline mental summary scores >50 points.

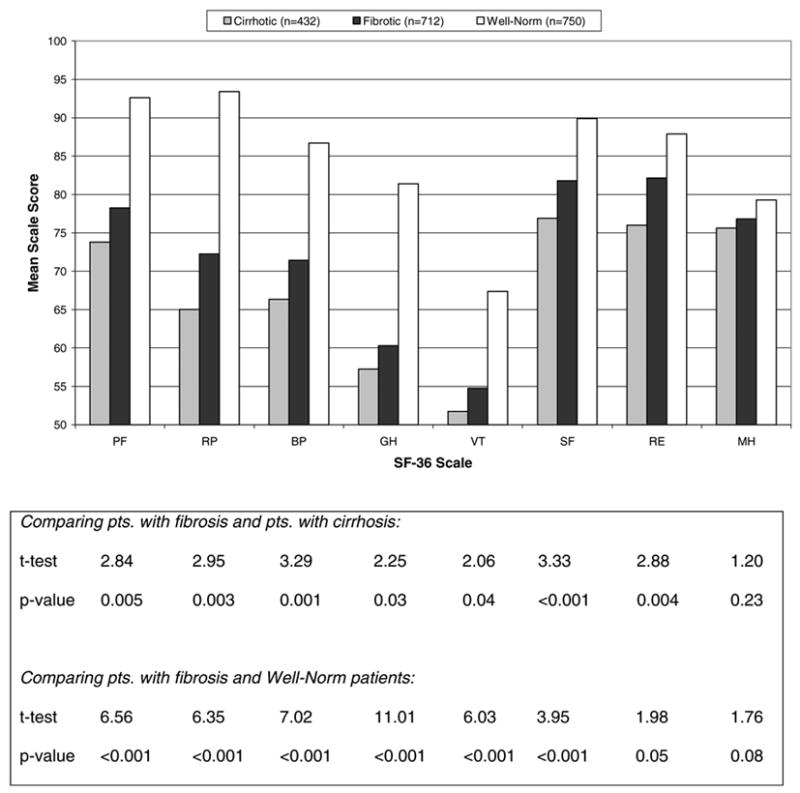

Comparison of HRQOL scores for the eight SF-36 domains among patients with cirrhosis (n = 432) and those with bridging fibrosis (n = 712) is shown in Fig. 2. Patients with cirrhosis had statistically significantly lower scores for seven of eight HRQOL domains. Mean scores for all eight HRQOL domains were consistently lower in HALT-C patients than in the Well-Norm cohort, although strict comparability between these cohorts could not be assured. HALT-C patients also had significantly lower mean scores on four of eight HRQOL domains (physical functioning, role physical, general health, and vitality) when compared to age-matched general US population norms (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

HRQOL scores at baseline of the eight scales of the SF-36 Health Survey (n = 1144). Higher scores indicate better HRQOL. Abbreviations: BP, bodily pain; GH, general health; MH, mental health; PF, physical functioning; pts., patients; RE, role emotional; RP, role physical; SF, social functioning; VT, vitality.

Factors that correlated with lower baseline HRQOL in the cohort of patients with hepatitis C enrolled in the lead-in phase of the HALT-C trial were evaluated using univariate and multivariate linear regression analysis of the three HRQOL summary scores: physical, mental, and sexual. We analyzed models that included and excluded BDI scores. We present the model that includes BDI, which assesses the effect of the other variables on mental summary, holding depression constant. Results of models excluding BDI were similar (data not shown).

As shown in Table 2, baseline factors associated with lower physical summary scores in a multivariate model were female gender, greater body mass index (BMI = weight in kilograms/height in meters squared), older age, current cigarette smoking, a higher BDI score, and use of antidepressant or anxiolytic medications at baseline. Factors that were less strongly but still significantly associated with lower physical summary scores included evidence of cirrhosis (palpable spleen), being not married or living as married, and abstinence from alcohol during the preceding six months. Notably, race or ethnicity, presence of diabetes or heart disease, serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, viral genotypes, or HCV RNA levels were not significant predictors.

Table 2.

Factors associated with HRQOL summary scores at baseline

| Baseline factors | Physical summary score(n = 1093)

|

Mental summary score(n = 1093)

|

Sexual summary score (n = 1085)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | Standard error | p value | b | Standard error | p value | b | Standard error | p value | |

| BDI score (+1 unit) | −0.69 | 0.04 | <0.0001 | −0.76 | 0.029 | <0.0001 | −1.95 | 0.11 | <0.0001 |

| Taking anxiolytic/antidepressant | −3.81 | 0.65 | <0.0001 | −1.86 | 0.46 | <0.0001 | −6.39 | 1.81 | 0.0004 |

| Body mass index (+1 unit) | −0.33 | 0.051 | <0.0001 | +0.085 | 0.036 | 0.02 | |||

| Age (+10 yr.) | −1.33 | 0.39 | 0.001 | −5.1 | 1.1 | <0.0001 | |||

| Male gender | 2.20 | 0.65 | 0.0007 | 5.07 | 1.77 | 0.004 | |||

| Alcohol use in past 6 months | 1.65 | 0.72 | 0.02 | 4.31 | 1.99 | 0.03 | |||

| No palpable spleen on physical exam | 2.12 | 0.89 | 0.02 | ||||||

| Married or living as married | 1.35 | 0.63 | 0.03 | ||||||

| No current cigarette smoking | 1.94 | 0.63 | 0.002 | ||||||

| Number of alcoholic drinks over lifetime(+1000 drinks) | 0.017 | 0.0065 | 0.008 | ||||||

| No history of cholesterol medication use | 18.83 | 4.47 | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Ishak fibrosis score (+1 unit) | −1.48 | 0.61 | 0.02 | ||||||

All of the variables listed in Table 1 were tested in models using backwards multivariate linear regression (SAS 8.2). All variables remaining in each model are significant at the 0.05 level or less (b = change in HRQOL score per unit of baseline factor, holding all other variables in the model constant). The R2 values for these best-fit models are as follows: physical summary score, R2 = 0.38; mental summary score, R2 = 0.46; sexual summary score, R2 = 0.32.

Factors associated with lower baseline mental summary scores in a multivariate model included three elements also associated with lower physical summary scores: use of antidepressant or anxiolytic medications at baseline, higher BDI score, lower BMI, and in addition, lifetime number of alcoholic drinks. Age, current smoking, gender, marital status, and recent alcohol abstinence were not significant predictors.

Factors associated with lower baseline sexual summary scores in a multivariate model were similar to the factors that were associated with lower physical summary scores. Factors that were also significantly associated with lower sexual summary scores were higher Ishak fibrosis score and history of cholesterol medication use. A history of diabetes or heart disease and higher ALT and HCV RNA levels (among several other variables from Table 1) were not significant predictors of sexual summary score.

3.2. Changes in HRQOL in patients with sustained virological response

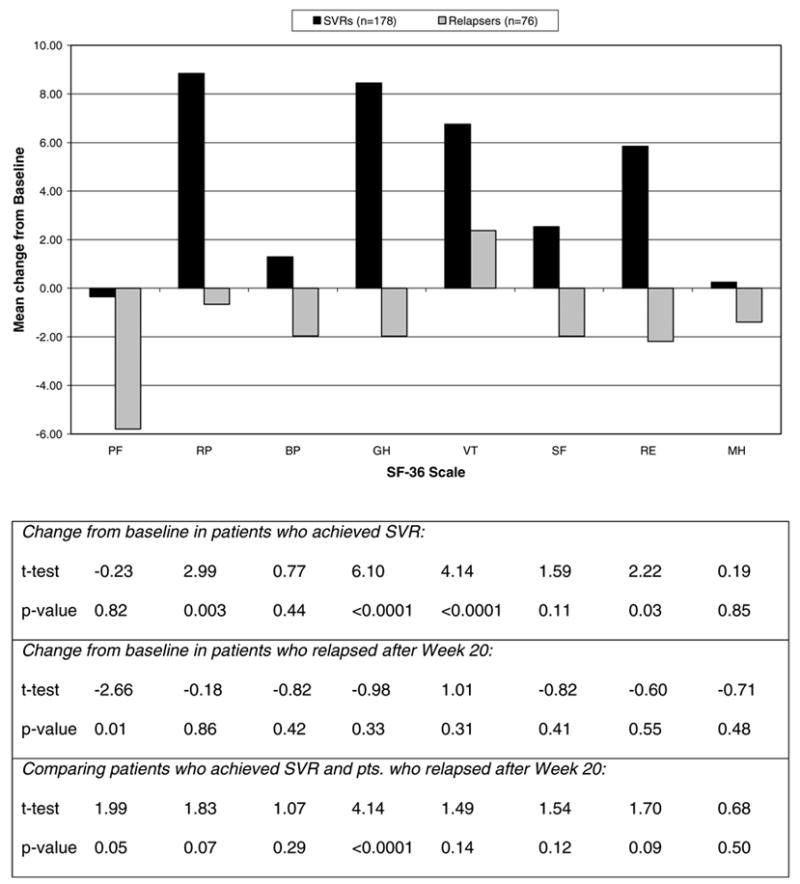

Three hundred and seventy-three (32.6%) subjects were HCV RNA negative at week 20 and continued therapy through week 48 (Fig. 1). At week 72, 258 patients were seen and were aware of their week 60 HCV RNA status when completing the HRQOL questionnaires. Changes from baseline in 178 patients who achieved SVR compared to 76 patients who tested HCV RNA positive prior to week 72 (relapsers) are shown in Fig. 3. Among patients with SVR, HRQOL scores were statistically significantly improved in four of eight HRQOL domains: role physical, general health, vitality, and role emotional. In contrast, relapser patients had significant worsening only on the physical functioning domain.

Fig. 3.

Change from baseline to week 72 in SF-36 scores by virologic response status (n = 254). Positive values indicate improvements; negative values indicate worsening. Abbreviations are as in the legend to Fig. 2. (SVRs, sustained virological responders.)

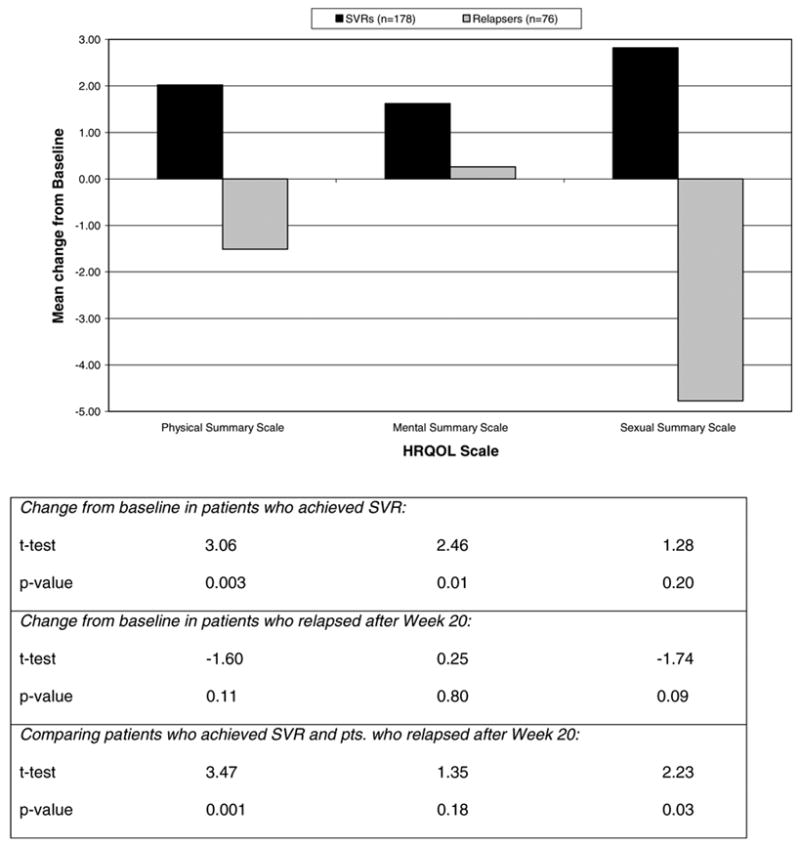

The changes in the physical, mental and sexual summary scales between the SVR and relapser patients are shown in Fig. 4. Patients with SVR had statistically significant improvements in physical and mental scores compared to baseline. In comparison to patients who responded and then relapsed, patients with SVR had statistically significant improvements in physical and sexual scores. These improvements occurred in men and women and patients with cirrhosis and with fibrosis only (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Change from baseline to week 72 in HRQOL summary scales by virologic response status (n = 254). Positive values indicate improvements; negative values indicate worsening. (SVRs, sustained virological responders.)

3.3. Factors associated with changes in quality of life scores

Multivariate linear regression analyses were performed to assess factors associated with changes in summary scores, controlling for baseline summary score (Table 3). The major predictor of improvement in physical summary scores was achievement of SVR (p = 0.0003). Patients without diabetes mellitus were more likely to have improvements in physical summary scores (p = 0.0007). A lack of improvement in physical summary scores was weakly associated with lower baseline BDI score and BMI, male gender, and persons who never drank alcohol (p values 0.02–0.05). Importantly, age, presence of cirrhosis, fibrosis scores, race and ethnicity, and baseline ALT and HCV RNA levels were not associated with changes in physical summary scores.

Table 3.

Factors associated with improvements in HRQOL summary scores from baseline to week 72

| Baseline factors | Physical summary score(n = 245)

|

Mental summary score (n = 245)

|

Sexual summary score (n = 246)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | Standard error | p value | b | Standard error | p value | b | Standard error | p value | |

| BDI score (+1 unit) | −0.17 | 0.074 | 0.02 | −0.18 | 0.087 | 0.04 | −0.61 | 0.22 | 0.007 |

| Body mass index (+1 unit) | −0.14 | 0.10 | 0.15 | −0.29 | 0.096 | 0.003 | |||

| No history of diabetes mellitus | 5.18 | 1.50 | 0.0007 | ||||||

| Ever drank alcohol regularly in past | 3.17 | 1.46 | 0.03 | ||||||

| Male gender | 2.45 | 1.23 | 0.05 | ||||||

| Not taking anxiolytic/antidepressant | 3.59 | 1.18 | 0.003 | ||||||

| No history of heart disease | 4.10 | 1.48 | 0.006 | ||||||

| Serum ALT (+1 unit) | −0.012 | 0.0053 | 0.02 | ||||||

| Achieved sustained virological response | 4.00 | 1.09 | 0.0003 | 7.49 | 3.37 | 0.03 | |||

The “achieved sustained virological response” variable and all of the variables listed in Table 1 were tested in models using backwards multivariate linear regression (SAS 8.2). All variables remaining in each model are significant at the 0.05 level or less, after adjustment by baseline summary score (b = change in HRQOL score per unit of baseline factor, holding all other variables in the model constant). The R2 values for these best-fit models are as follows: physical summary score, R2 = 0.26; mental summary score, R2 = 0.33; sexual summary score, R2 = 0.25.

Baseline factors associated in a multivariate model with lack of improvement in mental summary scores were a history of heart disease, lower baseline ALT, lower baseline BDI score and BMI, and use of antidepressant or anxiolytic medications. Overall, however, mental summary scores tended to be lower at week 72.

Improvements in sexual summary score were associated with SVR (p = 0.03) and lower baseline BDI score (p = 0.007) in a multivariate model. There was no additional influence of presence of cirrhosis, Ishak fibrosis score, alcohol use, or history of diabetes or heart disease at baseline.

Two patients who were complete virological responders during lead-in therapy and who relapsed late in the post-treatment follow-up phase are of special interest. At the time that they completed the HRQOL questionnaires at week 72, they believed that they were sustained responders. However, their week 72 (and confirmatory) HCV RNA levels were positive (6.18 log10 and 6.90 log10 IU/mL) and their serum ALT levels were elevated at week 72 (69 and 221 U/L). Their HRQOL and sexual functioning scores were low, similar to those of early relapsers, rather than of patients with SVR.

4. Discussion

Despite the availability and efficacy of peginterferon and ribavirin, therapy of chronic hepatitis C remains problematic. Shortcomings of current therapy include the protracted and complicated nature of treatment and unpleasant side effects. In addition, SVR rates are only 50–60% in published clinical trials and are appreciably lower in community practice [44,45]. Therapy is usually recommended only for patients with evidence of fibrosis or substantial necroinflammatory disease on liver biopsy [5,6]. Because the majority of treated patients are asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic, improvements in symptoms or HRQOL have not been considered reasons for recommending therapy.

As in many chronic diseases, HRQOL in chronic hepatitis C is of substantial importance to patients. Fearing a reduction in HRQOL associated with the adverse effects of treatment, some patients decline antiviral therapy [37,46]. Others request therapy in hopes that their physical, mental, and sexual functioning will improve. Previous studies in patients with less advanced hepatitis C have shown that HRQOL is measurably reduced and that successful therapy can lead to clinically meaningful improvements in several HRQOL domains [7,12,34,37].

The current analyses from the HALT-C Trial confirm the reduction in HRQOL among patients with chronic hepatitis C. In addition, they indicate that HRQOL scores are lower in patients with cirrhosis than in those with advanced fibrosis. ALT levels, viral titers, or other features of hepatic histology did not correlate with lower HRQOL or sexual scores, suggesting that disease stage is the major determinant of the effect of chronic hepatitis on HRQOL. Not surprisingly, other important determinants of lower HRQOL scores included the use of anti-depressant or anxiolytic medications, cigarette smoking, and higher BDI scores. Thus, the common co-morbidities found in patients with chronic hepatitis C, such as depression, diabetes, heart disease and obesity, are likely to contribute to the overall poor quality of life.

Of perhaps the greatest importance were the findings that (1) successful antiviral therapy led to improvement in many physical and sexual health scores and (2) that these effects occurred even in patients with advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis. In contrast, mental health scores showed less improvement. These observations suggest that HCV infection per se has a minimal effect on emotional states. Although many patients with chronic hepatitis C describe difficulty in thinking, concentrating, and memory, such symptoms may result from underlying conditions, such as anxiety, depression, or use of psychotropic medications, rather than from HCV infection [16]. Separate analyses of a subset of patients in the HALT-C Trial have led to similar conclusions regarding impairments in cognitive function in chronic hepatitis [18].

For most people, a satisfying personal sexual life is an important dimension of good quality of life [47]. In this study, three sexual health questions focused on desire, performance, and satisfaction domains. The current analysis suggests that sexual health is diminished among patients with chronic hepatitis C and that a component of the reduction in sexual functioning and satisfaction is associated with the degree of hepatic fibrosis or cirrhosis. Lower sexual summary scores were highly associated as well with female gender, older age, higher BDI score, history of cholesterol medication use, and concomitant use of antidepressant or anxiolytic medications. Overall, our findings suggest that diminished sexual health in patients with chronic hepatitis C can be improved, at least in part, by successful antiviral therapy. Patients who achieve an SVR may feel less stigmatized and concerned about potential transmission of HCV to their sexual partners, which has been a factor associated with lower HRQOL [48–50].

A potential confounder in most longitudinal studies of HRQOL in chronic hepatitis C, including this one, is that patients have known whether they responded to treatment or not when they completed post-treatment HRQOL instruments. Perhaps their emotional, physical, and sexual well-being are affected by knowledge of response status. Because of the design of this Study (and those of most previous studies in this field), this confounder cannot be avoided. Our Study was designed nearly a decade ago; in retrospect, it would have been preferable for the post-treatment HRQOL assessment to have been performed before patients learned their post-treatment HCV RNA status. However, because this assessment was performed at 72 weeks by design, results of post-treatment serum ALT or HCV RNA tests could not be withheld from patients. Although it is possible that a temporary reduction in viral load brings about an improvement in quality of life, it should be noted that the reductions in HRQOL among responders who relapsed were statistically significant in only one domain. It is also worth keeping in mind that these patients were followed for at least 1½ years. In people of mean age 50 years, the passage of time itself is associated with decrements in health-related quality of life.

In summary, our analyses indicate that HRQOL is decreased significantly in patients with chronic hepatitis C who have advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis. It is well known that side effects of current therapy result in further decrements in HRQOL and are major impediments to initiation and successful completion of therapy. Successful antiviral therapy is associated with clinically meaningful, significant improvements in HRQOL. Thus, the rationale for antiviral therapy of chronic hepatitis C should include a reduction in liver disease progression and hepatocellular carcinoma development and an improvement in health-related and sexual quality of life.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes & Digestive & Kidney Diseases (contract numbers are listed below). Additional support was provided by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), the National Cancer Institute, the National Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities and by General Clinical Research Center grants from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health (grant numbers are listed below). Additional funding to conduct this study was supplied by Hoffmann-La Roche, Inc., through a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement (CRA-DA) with the National Institutes of Health. In addition to the authors of this manuscript, the following individuals were instrumental in the planning, conduct and/or care of patients enrolled in this study at each of the participating institutions as follows:

University of Massachusetts Medical Center, Worcester, MA: (Contract N01-DK-9-2326) Savant Mehta, MD, Dawn Bombard, RN, Maureen Cormier, RN, Donna Giansiracusa, RN.

University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, CT: (Grant M01RR-06192) Michelle Kelley, RN, ANP.

Saint Louis University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO: (Contract N01-DK-9-2324) Bruce Bacon, MD, Debra King, RN, Judy Thompson, RN.

Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA: (Contract N01-DK-9-2319, Grant M01RR-01066) Raymond T. Chung, MD, Andrea E. Reid, MD, Wallis Molchen, Loriana Di Giammarino.

University of Colorado School of Medicine, Denver, CO: (Contract N01-DK-9-2327, Grant M01RR-00051) Gregory T. Everson, MD, Jennifer DeSanto, RN, Carol McKinley, RN, Brenda Easley, RN.

University of California – Irvine, Irvine, CA: (Contract N01-DK-9-2320, Grant M01RR-00827) John Hoefs, MD, Muhammad Sheikh, MD, Choon Park, RN.

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX: (Contract N01-DK-9-2321, Grant M01RR-00633) William M. Lee, MD, Nicole Crowder, LVN, Rivka Elbein, RN, BSN.

University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA: (Contract N01-DK-9-2325, Grant M01RR-00043) Karen L. Lindsay, MD, Carol B. Jones, RN, Susan L. Milstein, RN.

University of Michigan Medical Center, Ann Arbor, MI: (Contract N01-DK-9-2323, Grant M01RR-00042) Anna S.F. Lok, MD, Pamela A. Richtmyer, LPN, CCRC.

Virginia Commonwealth University Health System, Richmond, VA: (Contract N01-DK-9-2322, Grant M01RR-00065) Mitchell L. Shiffman, MD, Charlotte Hofmann, RN, Paula Smith, RN.

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Liver Diseases Branch, Bethesda, MD: T. Jake Liang, MD, Yoon Park, RN, Elenita Rivera, RN, Vanessa Haynes-Williams, RN.

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Division of Digestive Diseases and Nutrition, Bethesda, MD: James E. Everhart, MD, Leonard B. Seeff, MD, Patricia R. Robuck, PhD.

University of Washington, Seattle, WA: (Contract N01-DK-9-2318) Chihiro Morishima, MD, Minjun Chung, BS, ASCP.

New England Research Institutes, Watertown, MA: (Contract N01-DK-9-2328) Elizabeth C. Wright, PhD, Margaret C. Bell, RN, MS, MPH, CS, Marina Mihova, MHA.

Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Division of Hepatic Pathology and the Veterans Administration Special Reference Laboratory for Pathology, Washington, DC: Zachary D. Goodman, MD.

Abbreviations

- HRQOL

health-related quality of life

- HALT-C

Hepatitis C Antiviral Long-term Treatment against Cirrhosis Trial

- SF-36

Short-Form-36 Health Survey

- SVR

sustained virological response

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- BDI

Beck Depression Inventory II

- PF

physical functioning

- RP

role physical

- BP

bodily pain

- VT

vitality

- GH

general health

- SF

social functioning

- RE

role emotional

- MH

mental health

- BMI

body mass index

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

Appendix A. Sexual Summary Scale Items

Mean score on the following three questions if answered 1–5 (transformed to a 0–100 scale): How much of the time during the last four weeks, have you …

Felt your health interfered with your enjoyment of sex?

Lacked interest in sex?

Felt your health interfered with your sexual performance?

Answer possibilities

| Not at all | A little bit | Moderately | Quite a bit | Extremely | Does not apply |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | −1 |

Footnotes

This is publication number 14 from the HALT-C Trial Group.

Financial support: Financial relationships of the authors with Hoffmann-La Roche, Inc., are as follows: H.L. Bonkovsky is a consultant, is on the speakers’ bureau, and receives research support; P.F. Malet receives research support; R.K. Sterling is a consultant, on the speakers’ bureau, and receives research support; R.J. Fontana is a consultant and on the speakers’ bureau; A.M. Di Bisceglie is a consultant, on the speakers’ bureau, and receives research support; and T.R. Morgan is on the speaker’s bureau and receives research support. Other financial relationships related to this project are: H.L. Bonkovsky receives research support from Bayer Diagnostics; P.F. Malet receives research support from Bayer Diagnostics; R.K. Sterling is a consultant and receives research support from Wako Diagnostics; T.R. Morgan receives research support from Metabolic Solutions; and D.R. Gretch receives research support from Bayer Diagnostics. Authors with no financial relationships related to this project are K.K. Snow, C. Back-Madruga, C.C Kulig, J.L. Dienstag, and M.G. Ghany.

References

- 1.Liang TJ, Rehermann B, Seeff LB, Hoofnagle JH. Pathogenesis, natural history, treatment, and prevention of hepatitis C. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:296–305. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-4-200002150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong GL, Wasley A, Simard EP, McQuillan GM, Kuhnert WL, Alter MJ. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1999 through 2002. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:705–714. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoofnagle JH. Hepatitis C: the clinical spectrum of disease. Hepatology. 1997;26 (3 Suppl 1):15S–20S. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Bisceglie AM, Hoofnagle JH. Optimal therapy of hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2002;36 (5 Suppl 1):S121–S127. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement. Management of hepatitis C: 2002–June 10–12, 2002. Hepatology. 2002;36(5 Suppl 1):S3–20. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.37117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strader DB, Wright T, Thomas DL, Seeff LB. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2004;39:1147–1171. doi: 10.1002/hep.20119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carithers RL, Jr, Sugano D, Bayliss M. Health assessment for chronic HCV infection: results of quality of life. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41 (12 Suppl):75S–80S. doi: 10.1007/BF02087879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manns M. Autoimmune hepatitis. In: Schiff ER, Sorrell MF, Maddrey WC, editors. Schiff’s diseases of the liver. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003. pp. 1001–1018. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fried MW, Shiffman ML, Reddy KR, Smith C, Marinos G, Goncales FL, Jr, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:975–982. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hadziyannis SJ, Sette H, Jr, Morgan TR, Balan V, Diago M, Marcellin P, et al. Peginterferon-alpha2a and ribavirin combination therapy in chronic hepatitis C: a randomized study of treatment duration and ribavirin dose. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:346–355. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-5-200403020-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonkovsky HL, Woolley JM. Reduction of health-related quality of life in chronic hepatitis C and improvement with interferon therapy. The Consensus Interferon Study Group Hepatology. 1999;29:264–270. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McHutchison JG, Ware JE, Jr, Bayliss MS, Pianko S, Albrecht JK, Cort S, et al. The effects of interferon alpha-2b in combination with ribavirin on health related quality of life and work productivity. J Hepatol. 2001;34:140–147. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)00026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neary MP, Cort S, Bayliss MS, Ware JE., Jr Sustained virologic response is associated with improved health-related quality of life in relapsed chronic hepatitis C patients. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19 (Suppl 1):77–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rasenack J, Zeuzem S, Feinman SV, Heathcote EJ, Manns M, Yoshida EM, et al. Peginterferon alpha-2a (40 kDa) [Pegasys] improves HR-QOL outcomes compared with unmodified interferon alpha-2a [Roferon-A]: in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Pharmacoeconomics. 2003;21:341–349. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200321050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis GL, Balart LA, Schiff ER, Lindsay K, Bodenheimer HC, Jr, Perrillo RP, et al. Assessing health-related quality of life in chronic hepatitis C using the Sickness Impact Profile. Clin Ther. 1994;16:334–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chou R, Clark EC, Helfand M. Screening for hepatitis C virus infection: a review of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:465–479. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-6-200403160-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hussain KB, Fontana RJ, Moyer CA, Su GL, Sneed-Pee N, Lok AS. Comorbid illness is an important determinant of health-related quality of life in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2737–2744. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.04133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fontana RJ, Moyer CA, Sonnad S, Lok ASF, Sneed-Pee N, Walsh J, et al. Comorbidities and quality of life in patients with interferon-refractory chronic hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:170–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee WM, Dienstag JL, Lindsay KL, Lok AS, Bonkovsky HL, Shiffman ML, et al. Evolution of the HALT-C Trial: pegylated interferon as maintenance therapy for chronic hepatitis C in previous interferon nonresponders. Control Clin Trials. 2004;25:472–492. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shiffman ML, Di Bisceglie AM, Lindsay KL, Morishima C, Wright EC, Everson GT, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C who have failed prior treatment. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1015–1023. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, Callea F, De GJ, Gudat F, et al. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1995;22:696–699. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80226-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beck AT. Beck Depression Inventory. San Antonio, TX: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. The Psychological Corporation. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Brace and Company; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, MA: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-36 Physical and Mental Summary Scales: A User’s Manual. Boston, MA: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE., Jr The MOS short-form general health survey. Reliability and validity in a patient population. Med Care. 1988;26:724–735. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198807000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Lu JF, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care. 1994;32:40–66. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31:247–263. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jenkinson C, Lawrence K, McWhinnie D, Gordon J. Sensitivity to change of health status measures in a randomized controlled trial: comparison of the COOP charts and the SF-36. Qual Life Res. 1995;4:47–52. doi: 10.1007/BF00434383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stucki G, Daltroy L, Katz JN, Johannesson M, Liang MH. Interpretation of change scores in ordinal clinical scales and health status measures: the whole may not equal the sum of the parts. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:711–717. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(96)00016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolinsky FD, Wan GJ, Tierney WM. Changes in the SF-36 in 12 months in a clinical sample of disadvantaged older adults. Med Care. 1998;36:1589–1598. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199811000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coakley EH, Kawachi I, Manson JE, Speizer FE, Willet WC, Colditz GA. Lower levels of physical functioning are associated with higher body weight among middle-aged and older women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998;22:958–965. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hunt CM, Dominitz JA, Bute BP, Waters B, Blasi U, Williams DM. Effect of interferon-alpha treatment of chronic hepatitis C on health-related quality of life. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:2482–2486. doi: 10.1023/a:1018852309885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Foster GR, Goldin RD, Thomas HC. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection causes a significant reduction in quality of life in the absence of cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1998;27:209–212. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fontana RJ, Hussain KB, Schwartz SM, Moyer CA, Su GL, Lok AS. Emotional distress in chronic hepatitis C patients not receiving antiviral therapy. J Hepatol. 2002;36:401–407. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00280-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perrillo R, Rothstein KD, Rubin R, Alam I, Imperial J, Harb G, et al. Comparison of quality of life, work productivity and medical resource utilization of peginterferon alpha 2a vs the combination of interferon alpha 2b plus ribavirin as initial treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis C. J Viral Hepat. 2004;11:157–165. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2003.00482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wessely S, Pariante C. Fatigue, depression and chronic hepatitis C infection. Psychol Med. 2002;32:1–10. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hauser W, Zimmer C, Schiedermaier P, Grandt D. Biopsycho-social predictors of health-related quality of life in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:954–958. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000145824.82125.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skinner HA, Sheu WJ. Reliability of alcohol use indices. The Lifetime Drinking History and the MAST. J Stud Alcohol. 1982;43:1157–1170. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1982.43.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ostapowicz G, Watson KJ, Locarnini SA, Desmond PV. Role of alcohol in the progression of liver disease caused by hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 1998;27:1730–1735. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dufour MC. What is moderate drinking? Defining “drinks” and drinking levels. Alcohol Res Health. 1999;23:5–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thalji L, Haggerty CC, Rubin R, Berckmans TR, Pardee FL. 1990 National Survey of Functional Health Status: Final Report. Chicago, IL: National Opinion Research Center; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Falck-Ytter Y, Kale H, Mullen KD, Sarbah SA, Sorescu L, McCullough AJ. Surprisingly small effect of antiviral treatment in patients with hepatitis C. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:288–292. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-4-200202190-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strader DB. Understudied populations with hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2002;36(5 Suppl 1):S226–S236. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Afdhal NH, Dieterich DT, Pockros PJ, Schiff ER, Shiffman ML, Sulkowski MS, et al. Epoetin alfa maintains ribavirin dose in HCV-infected patients: a prospective, double-blind, randomized controlled study. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1302–1311. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rosen RC. Measurement of male and female sexual dysfunction. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2001;3:182–187. doi: 10.1007/s11920-001-0050-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zickmund S, Hillis SL, Barnett MJ, Ippolito L, LaBrecque DR. Hepatitis C virus-infected patients report communication problems with physicians. Hepatology. 2004;39:999–1007. doi: 10.1002/hep.20132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zickmund S, Ho EY, Masuda M, Ippolito L, LaBrecque DR. “They treated me like a leper” Stigmatization and the quality of life of patients with hepatitis C. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:835–844. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20826.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Danoff A, Khan O, Wan DW, Hurst L, Cohen D, Tenner CT, et al. Sexual dysfunction is highly prevalent among men with chronic hepatitis C virus infection and negatively impacts quality of life. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1235–1243. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]