Abstract

Illumination of Drosophila photoreceptor cells induces multi-facet responses, which include generation of the photoreceptor potential, screening pigment migration and translocation of signaling proteins which is the focus of recent extensive research. Translocation of three signaling molecules is covered in this review: (1) Light-dependent translocation of arrestin from the cytosol to the signaling membrane, the rhabdomere, determines the lifetime of activated rhodopsin. Arrestin translocates in PIP3 and NINAC myosin III dependent manner, and specific mutations which disrupt the interaction between arrestin and PIP3 or NINAC also impair the light-dependant translocation of arrestin and the termination of the response to light. (2) Activation of Drosophila visual G protein, DGq, causes a massive and reversible, translocation of the α subunit from the signaling membrane to the cytosol, accompanied by activity-dependent architectural changes. Analysis of the translocation and the recovery kinetics of DGqα in wild-type flies and specific visual mutants indicated that DGqα is necessary but not sufficient for the architectural changes. (3) The TRP-like (TRPL) but not TRP channels translocate in a light-dependent manner between the rhabdomere and the cell body. As a physiological consequence of this light-dependent modulation of the TRP/TRPL ratio, the photoreceptors of dark-adapted flies operate at a wider dynamic range, which allows the photoreceptors enriched with TRPL to function better in darkness and dim background illumination. Altogether, signal-dependent movement of signaling proteins plays a major role in the maintenance and function of photoreceptor cells.

Keywords: Photoreceptors, Translocation, TRPL, Gqα, Arrestin, Adaptation

1. Introduction

Vertebrate and invertebrate photoreceptors are highly polarized cells comprised of the cell body and the signaling compartment (Hardie and Raghu, 2001). The signaling compartment is designated rhabdorere in invertebrates, and outer segment in vertebrates. The major proteins that are essential for phototransduction reside in the signaling compartment. Absorption of photons by the photopigment rhodopsin in fly photoreceptors activates Gqα protein (Scott et al., 1995), which in turn activates phospholipase Cβ (PLCβ) (Devary et al., 1987) and lead, in a still unclear way, to activation of the light sensitive channels TRP (Hardie and Minke, 1992) and TRPL (Phillips et al., 1992). Inactivation of the photopigment is achieved by the binding of arrestin2 (Byk et al., 1993) to metarhodopsin, which prevents further association between metarhodopsin and the Gq-protein.

Photoreceptor cells adjust their sensitivity to light (Fain et al., 2001; Minke and Hardie, 2000) to fit the changing ambient illumination and thus maintain their working range within a physiologically relevant range of light intensities, by a mechanism known as light adaptation. Short-term adaptation rapidly reduces the amplitude of the electrical response to light. Ca2+ is a key regulator of this process, in which the amplitude of the response to light recovers within less than a minute. Long-term adaptation of invertebrate photoreceptors, which takes place in a time-scale of many minutes to hours, is governed mainly by translocations of signaling proteins into and out of the signaling membrane.

In this review we cover a striking phenomenon found in Drosophila photoreceptors and in mammalian signaling pathways. This phenomenon is manifested in a light-regulated translocation of several critical signaling proteins from the rhabdomere, to the cell body, and vice versa. These signal-regulated translocations play critical roles in the physiology of Drosophila photoreceptor cells and mammalian cells and tissues.

2. Light adaptation through phosphoinositide and NINAC myosin III dependant translocation of arrestin

Absorption of photons converts rhodopsin to its dark stable and physiologically active photoproduct, metarhodopsin. Binding of arrestin2 (Arr2) to the phosphorylated metarhodopsin prevents the activation of Gqα by metarhodopsin and thus determines the lifetime of functional metarhodopsin. The dissociation of Arr2 from rhodopsin requires photoconversion of metarhodopsin back to rhodopsin, followed by dephosphorylation of rhodospsin by the Ca2+ dependent protein phosphatase RDGC (retinat degeneration C) (Byk et al., 1993; Dolph et al., 1993; Steele et al., 1992; Yamada et al., 1990). Arr2 is phosphorylated by calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II (CamKII) (Matsumoto et al., 1994; Yamada et al., 1990), which is activated by Ca2+ influx through the light activated TRP and TRPL channels (Alloway and Dolph, 1999; Byk et al., 1993; Kiselev et al., 2000; Peretz et al., 1994). Mutations which cause stable association between Arr2 and metarhodopsin result in clathrin-dependent endocytosis of the metarhodopsin–Arr2 complexes into the cell body that eventually lead to degeneration of the photoreceptor cell (Alloway and Dolph, 1999; Alloway et al., 2000; Kiselev et al., 2000; Orem and Dolph, 2002).

Recent immunolocalization studies by Lee et al. (2003) have shown that light-dependant translocation of Arr2 to and from the rhabdomere is impaired in cds (Wu et al., 1995) and rdgB (Vihtelic et al., 1993, 1991) mutants, in which PI biogenesis and trafficking are disrupted, respectively. They, furthermore, showed that in PTEN; dAkt and PTEN overexpression (Huang et al., 1999; Stocker et al., 2002) mutants, in which metabolism of PIP3 is defective, Arr2 translocation was also impaired. Using a nitro-cellulose phospholipids binding assay they have shown that the Arr2 C-terminal, but not N-terminal, binds directly to several PIs in a pattern similar to CRAC proteins that bind preferentially PIP3. Since the amino acid residues that contribute to the binding of PI in β-arrestin (Gaidarov et al., 1999) are not conserved in Arr2, a structural homology modeling was used to identify candidate residues participating in the interaction between Arr2 and PIP3. The arrestin/PIP3 binding model suggests that Lysine 228, 231 and 257 create a basic amino acid pocket and form hydrogen bonds with the three phosphates in PIP3.

To determine the physiological role of PI binding, Montell and colleagues have generated transgenic flies that express the full length Arr2 with substitutions of all three lysine residues with glutamine (3K/Q), and with arginine (3K/R) as a control. Both mutants showed no defect in association or dissociation of Arr2 from metarhodopsin, but in the arr23K/Q alone both the light-dependent movement of Arr2 to the rhabdomere, and the clathrin-dependant endocytosis were delayed. Moreover, blocking phototransduction by the PLC mutant norpA in the norpA;arr23K/Q double mutant suppressed light-dependent retinal degeneration typical for norpA mutants (Alloway and Dolph, 1999; Alloway et al., 2000; Ostroy, 1978).

To investigate the molecular basis of the PI-dependent translocation of Arr2 into the rhabdomere, Montell and colleagues used the ninaC (neither inactivation nor after-potential C) mutants (Lee and Montell, 2004). The NINAC protein consists of a myosin III head domain linked at the N-terminal to a protein kinase catalytic domain. The ninaC gene (Montell and Rubin, 1988) encodes two isoforms: p132 which is a shorter protein localized to the cell body and a larger protein, p174, which is localized to the rhabdomere. The null mutant ninaCP235 lacks both proteins. Although the precise role of NINAC is not entirely clear absence of NINAC results in abnormal cytoskeleton in the signaling compartment. The light-induced translocation of Arr2 was impaired in ninaCP132 and in the null mutant ninaCP235, but not in the ninaCP174. Although Arr2 did not coimmunoprecipitate with NINAC, Arr2 did bind to calmodulin-agarose beads in wild type and in the two NINAC mutants ninaCP132 and ninaCP174 but not in ninaCP235 null mutant, indicating that Arr2 interacts with both isoforms of NINAC. In contrast, the binding of Arr2 to the calmodulin-agarose beads in the arr23K/R mutant was dramatically decreased. Binding assays have shown that both NINAC isoforms bind to PIP2 and PIP3 beads. This interaction was not dependent on Arr2, as NINAC was also bound to PIP3 and PIP2 beads in arr25 null mutant.

Electroretinogram (ERG) recordings, is a measure of the extracellular response to light of the entire eye in vivo. ERG measured from dark and light adapted wild-type flies revealed that illumination with white light, similar to that used to induce light-dependent translocation of Arr2 into the rhabdomere, increased significantly the speed of ERG responses termination. This phenomenon was interpreted as long-term adaptation arising from Arr2 translocation, since the binding of Arr2 to metarhodopsin is a rate limiting step in the termination of the photoresponse (Dolph et al., 1993; Ranganathan and Stevens, 1995) to intense white or blue lights and a severe reduction in the concentration of Arr2 throughout the cell result in slow response termination. In support of this view, the termination rate of the ERG in arr25 null mutant was hardly affected by prior illumination. In order to examine the relationship between the adaptation phenomenon and the translocation of Arr2, the time required for maximal adaptation to light, as measured by the rate of response termination, was examined in mutant flies. Indeed, in the arr23K/Q mutants slower ERG response termination was observed even after 10 min illumination that was sufficient for almost maximal adaptation in wild type and arr23K/R. Similar results were obtained in the PTEN overexpression mutants in which slow trafficking of Arr2 into the rhabdomere was found, thus supporting the conclusion that Arr2 interaction with PI is essential for this long-term adaptation. Adaptation was also defective in ninaCP132 and even more severely affected in the ninaCP235 null mutant but not in the ninaCP174 mutant.

Altogether the authors suggest that both Arr2 and NINACP132 binds to PI-containing vesicles independently, and that myosin motor activity facilitates the movement of the vesicle together with Arr2 towards the rhabdomere, while a rise in the Arr2 concentration in the rhabdomere mediates the acceleration of ERG response termination and hence shorten long-term adaptation.

3. Light regulation of Gqα translocation and morphological changes in Drosophila photoreceptors

Many signal transduction cascades use the heterotrimeric G-proteins as a molecular transducers. One of the two major determinants of the localization of G-proteins to the membrane is the lipid modification of G-proteins. All α subunits of heterotrimeric G-proteins (with the exception of transducin) are reversibly modified by palmitoylation, i.e., the attachment of palmitate to a cysteine residue near the N-terminus (reviewed in Chen and Manning (2001), Mumby (1997), Smotrys and Linder (2004), Wedegaertner (1998)). The second major determinant of G-protein localization is the anchoring of the Gβγ subunits to the membrane (Evanko et al., 2001, 2000).

Although heterotrimeric G-proteins are subject of intensive research little is known about the regulation of Gα subunit localization within the natural endogenous environment of a specialized signaling cells. Recent studies by Kosloff et al. (2003) using live Drosophila flies, have indicated that light causes massive and reversible translocation of the visual Gqα to the cytosol. In these studies the Drosophila eye-specific Gqα (DGqα) translocates to the cytosol during illumination and subsequently returns to the membrane as an inactive Gqα-GDP form, via binding to the βγ dimmer. The role of the β-subunit in DGqα movement was studied in Drosophila photoreceptors by using the mutant (Dolph et al., 1994), which expresses highly reduced amounts of the eye-specific DGqβ. Analysis of the heterozygot revealed that the kinetics of the light-dependent translocation of DGqα, and in particular the subsequent recovery were markedly slowed down.

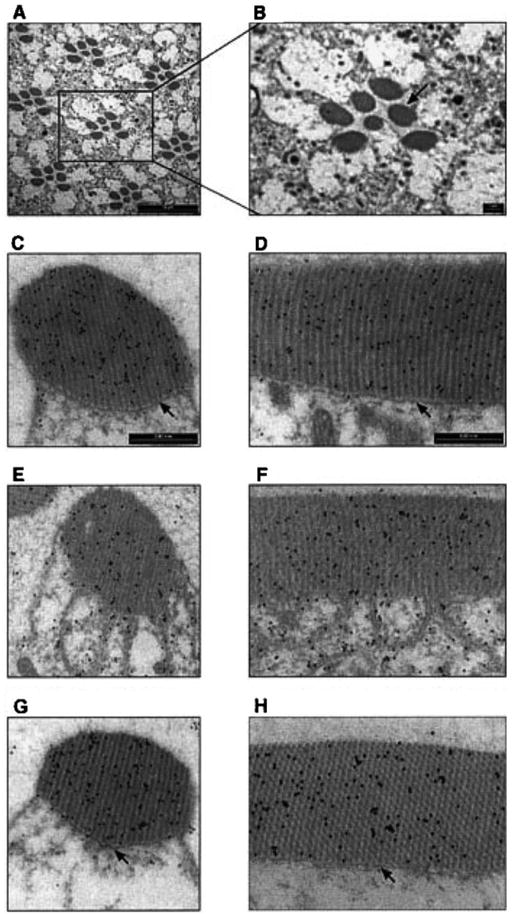

The movement of Gqα was associated with marked architectural changes in the signaling compartment, the rhabdomere (Fig. 1). Genetic dissection together with detailed kinetic analysis, were used to characterize the translocation cycle and to unravel how signaling molecules that interact with Gqα affect these processes. Epistatic analysis showed that Gqα is necessary but not sufficient to bring about the morphological changes in the signaling organelle. Furthermore, mutant analysis indicated that Gqβ is essential for targeting of Gqα to the membrane and suggested that Gqβ is also needed for efficient activation of Gqα by rhodopsin. These results support the ‘two signal model’ hypothesis (Resh, 1999; Wedegaertner, 1998) for membrane targeting in a living organism, which suggests that both binding to Gβγ and lipid modification are required or Gα binding to the membrane. These studies, furthermore, characterize the regulation of both the activity-dependent Gqα localization and the cellular architectural changes in Drosophila photoreceptors.

Fig. 1.

Light-dependent translocation of DGqα and rhabdomeral architectural changes shown by immunogold labeling. Panels A and B show a low magnification cross-section of the Drosophila’s compound eye for orientation. The seven dark oval structures of each visual unit (ommatidium) are the rhabdomeres, the signaling compartment of the photoreceptor cell composed of tightly packed microvilli. Panels C, E, G show cross-sections of a single rhabdomere while panels D, F, H show a longitudinal section along the axis of the rhabdomere. In these panels, DGqα is localized by immunogold labeling, seen as dark dots. Panels C and D are from dark-adapted flies. Panels E and F are from flies illuminated for 60 min with blue light. Panels G and H are from flies that had been illuminated for 60 min and subsequently kept for 2 h in the dark. Illumination (panels E and F) caused remarkable architectural changes in the cell. The boundary between the rhabdomere and the rest of the cell disappears due to disruption of the cytoskeletal Rhabdomeral Terminal Web (RTW—marked with arrows in panels C and D). As a result, the rhabdomere collapses and membrane tendrils resembling a house painter’s brush are seen intruding into the cytosol. These architectural changes are completely reversible, as after 2 h in the dark (panels G and H) the rhabdomeres are indistinguishable from those of dark-adapted flies (panels C and D). Similar observations were found in six different flies. (From Kosloff et al., 2003.)

4. Light-regulated translocation of the TRPL channel

To achieve a very high gain, characteristic of the electrical response to light, the photoreceptor cell maximizes the current produced by a single photon using both the TRP channel and a relatively high level of TRPL channels. To prevent saturation of the light response upon an increase in ambient light, the Ca2+ flow via the Ca2+-selective TRP channel attenuates the non-selective cation channel, TRPL (Reuss et al., 1997), and also induces its translocation out of the signaling membranes (Bähner et al., 2002). This novel mechanism to fine-tune visual responses is also used by other cellular signaling mechanisms such as fine tuning of growth cone path finding due to the action of a growth factor on TRPC5 activation (Bezzerides et al., 2004).

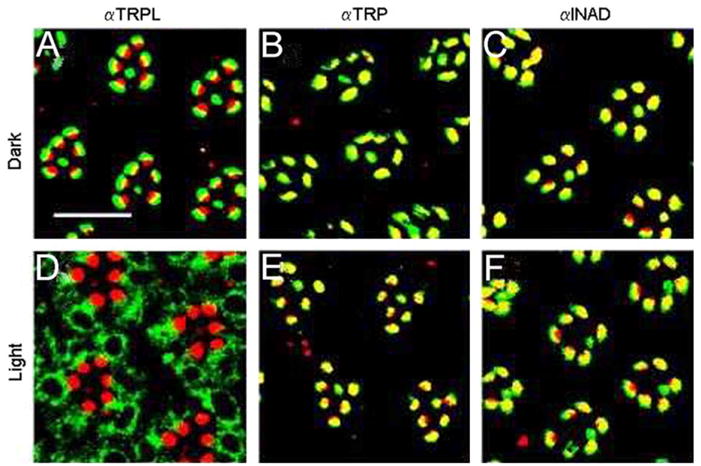

The relatively high level of TRPL, observed in photoreceptor membranes of dark-raised flies, is decreased when the flies are transferred to light (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the amount of rhabdomeral TRPL of flies that were kept in light for 16 h was close to the detection limit of the Western blot analysis but increased to a high level within 1 h after transferring of the flies to darkness. The amount of rhabdomeral TRP and also that of other components of the INAD signaling complex (Shieh and Niemeyer, 1995; Tsunoda et al., 1997; Tsunoda and Zuker, 1999) PLCβ, ePKC, and INAD, was unaffected by light. This finding indicates that the changes in the rhabdomeral TRPL level are specific to this ion channel subunit.

Fig. 2.

Light-dependent translocation of TRPL molecules in the photoreceptor cells of Drosophila compound eyes. Cross-sections through wild-type Drosophila (A–F) eyes of light- and dark-raised flies were double labeled with rhodamin-coupled wheat germ agglutinin, which specifically labels rhabdomeral photoreceptor membranes (red fluorescence), and antibodies against TRPL, TRP, and INAD, as indicated. The overlay of both markers appears yellow. Scale bars in (A), 10 μm. (Modified from Bähner et al., 2002.)

Direct visualization of intracellular movements of TRPL in photoreceptors upon illumination was obtained by immunolabeling of cross-sections through Drosophila eyes. This study revealed that unlike TRPL, TRP and INAD are confined to the rhabdomeres, independent of whether the flies are kept in darkness or in light prior to sectioning. Antibodies directed against TRPL specifically labeled the rhabdomere area of cross-sectioned eyes obtained from dark-raised flies (Fig. 2). In the eye-sections of light-raised flies the TRPL-specific immunofluorescence was distributed over the cell body of the photoreceptor cell and was not detected in the rhabdomeres (Fig. 2) in line with the Western blot analysis.

Since the translocation of TRPL depends on illumination, the question arises whether or not the response to light through activation of the TRP and TRPL channels is the trigger for TRPL movement to the cell body. Using immunocytochemistry, TRPL translocation from the rhabdomere to the cell body was tested in the nearly null PLC mutant, norpAP24 (Bloomquist et al., 1988), the null mutant of TRP, trpP343 (Scott et al., 1997) and the null INAD mutant, inaD1. Young inaD1 flies contain rhabdomeral TRP, which is most likely detached from the signaling complex and therefore degrades with age and is largely missing in older inaD1 flies (Tsunoda et al., 1997). Light-induced translocation of TRPL to the cell body was observed in young inaD1 flies, but did not occur in the trp null mutant and in old inaD1 flies. In norpAP24 mutants, translocation of TRPL tagged with Green Fluorescent Protein (TRPL-eGFP) was blocked (Bähner et al., 2002 note added in proofs). These findings reveal that when TRP is missing, as in the trp mutant and in old inaD1 flies, TRPL internalization is not observed (Bähner et al., 2002). Therefore, the presence of TRP seems to be required for TRPL internalization. If the lack of PLC blocks TRPL translocation as found in TRPL-eGFP fusion experiments, then the block of TRPL translocation (Hardie and Minke, 1992; Peretz et al., 1994), by the absence of either TRP or PLC, suggests that light-induced Ca2+ influx is the trigger for TRPL translocation.

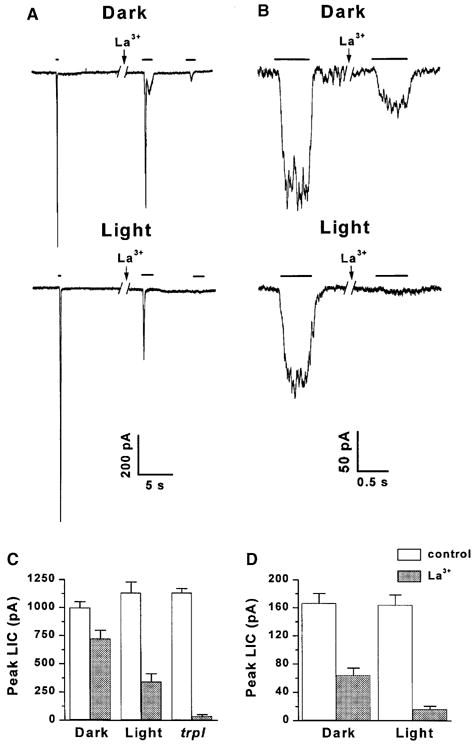

The light-induced current (LIC) of wild-type flies is composed of two independent components arising from activation of the TRP and TRPL channels (Reuss et al., 1997). Patch clamp whole cell recordings in isolated ommatidia of Drosophila were used to examine two properties of the LIC which discriminate between the contribution of the TRP and TRPL channels to the LIC: the block by La3+ and the reversal potential (Reuss et al., 1997).

Application of La3+ in micromolar concentration is known to specifically block the TRP but not the TRPL channels (Hardie and Minke, 1992; Hochstrate, 1989; Suss Toby et al., 1991). In wild-type Drosophila application of La3+ specifically blocks the TRP channels leaving a residual response, which is mediated by the TRPL channels and is indistinguishable from the response measured in trp mutant photoreceptors. In light-raised wild-type flies, application of La3+ largely reduced the peak amplitude of the LIC in response to intense light and modified the waveform of the response to prolonged light displaying the typical trp phenotype. In dark-raised wild-type flies application of La3+ under identical experimental conditions, had a much smaller effect on the peak amplitude of the LIC in response to similar light intensity. The weak trp phenotype in dark-raised flies indicates a reduced effect for La3+ (Fig. 3). Quantitative analysis at dim lights shows that La3+ suppressed the LIC suggesting a relative contribution of TRPL to the LIC of ~9% and 38%, in light- and dark-raised flies, respectively. Roughly similar conclusions were derived from measurements of the change in the reversal potential of light and dark-raised flies, together suggesting that a significantly larger amount of functional TRPL channels is present in dark-raised flies relative to light-raised flies (Bähner et al., 2002).

Fig. 3.

Differential block of the LIC by La3+ in light- and dark-raised wild-type flies and in the trpl mutant. (A) Responses to relatively intense lights of wild-type Drosophila cells of flies raised in light or darkness (as indicated) during whole cell recordings at a holding potential of −60 mV. Cells were stimulated by constant white light, of durations indicated by bars, attenuated by 3.6 or 2.5 log units for dark- and light-raised flies, respectively. The left LIC are control responses. Application of La3+ (10 μM) to the bath (as indicated by arrow) led to a reduction in peak amplitude and suppression of the response to a second light pulse, typical for the trp mutant. The break in the traces indicates a time of 2 min. (B) Responses to relatively dim lights (orange lights, attenuated by 2.8–3.3 log units) in a paradigm similar to that of Fig. 3A, except that 0.5 mM external Ca2+ was used and the La3+ concentration was 20 μM. The effective intensity of the orange light was ~100 fold dimmer than the white light used in A. (C) Histogram plotting the peak amplitudes of the LIC of Fig. 3A, in response to the constant light before (control) and after application of La3+ in dark- and light-raised wild-type flies and in the trpl mutant (as indicated). The error bars are SEM calculated from 6–8 cells for each group. (D) Histogram plotting the peak amplitudes of the LIC of Fig. 3B in response to the dim test light before (control) and after application of La3+ in dark- and light-raised flies. The error bars are SEM calculated from 5 cells for each group. (From Bähner et al., 2002.)

Measurements of the sensitivity to light of dark- and light-raised flies in vivo revealed that wild-type flies kept in darkness are very sensitive to dim background lights and respond within a relatively wide dynamic range having relatively low sensitivity to small changes in stimulus intensity. Wild-type light-raised flies are less sensitive to dim background lights, have a smaller dynamic range, but their photoreceptors are more sensitive to small changes in light intensity within their dynamic range. The fact that trpl mutants, when kept in either light or darkness, behave similar to light-raised wild-type flies, strongly suggests that translocation of TRPL underlies the fine tuning of long-term adaptation (Bähner et al., 2002).

Translocation of TRP channels of both Drosophila and mammalian cells (Bähner et al., 2002; Bezzerides et al., 2004; Boels et al., 2001; Kanzaki et al., 1999) emerges as a novel and important regulatory mechanism with wide implications to a variety of signaling mechanisms.

5. Concluding remarks

Signal-dependent movement of proteins has recently emerged as an important mechanisms to fine tune the function of several processes including neuronal path finding and long-term adaptation of both vertebrate and invertebrate photoreceptors. While the molecular mechanism underlying translocation of soluble proteins such as DGq, transducin and arrestin has been partially elucidated, the molecular mechanism underlying translocation of channel proteins is largely unknown and imposes a challenge for future studies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ben Katz for critical reading of the manuscript. The experimental parts of this review were supported by grants of the National Eye Institute grant EY 03549, a United States–Israel Binational Science Foundation (BSF), German–Israel foundation (GIF) and the Israel Science Foundation (ISF).

References

- Alloway PG, Dolph PJ. A role for the light-dependent phosphorylation of visual arrestin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6072–6077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alloway PG, Howard L, Dolph PJ. The formation of stable rhodopsin-arrestin complexes induces apoptosis and photoreceptor cell degeneration. Neuron. 2000;28:129–138. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00091-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bähner M, Frechter S, Da Silva N, Minke B, Paulsen R, Huber A. Light-regulated subcellular translocation of Drosophila TRPL channels induces long-term adaptation and modifies the light-induced current. Neuron. 2002;34:83–93. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00630-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezzerides VJ, Ramsey IS, Kotecha S, Greka A, Clapham DE. Rapid vesicular translocation and insertion of TRP channels. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:709–720. doi: 10.1038/ncb1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomquist BT, Shortridge RD, Schneuwly S, Perdew M, Montell C, Steller H, Rubin G, Pak WL. Isolation of a putative phospholipase C gene of Drosophila, norpA, and its role in photo-transduction. Cell. 1988;54:723–733. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)80017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boels K, Glassmeier G, Herrmann D, Riedel IB, Hampe W, Kojima I, Schwarz JR, Schaller HC. The neuropeptide head activator induces activation and translocation of the growth-factor-regulated Ca(2+)-permeable channel GRC. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:3599–3606. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.20.3599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byk T, Bar Yaacov M, Doza YN, Minke B, Selinger Z. Regulatory arrestin cycle secures the fidelity and maintenance of the fly photoreceptor cell. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:1907–1911. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CA, Manning DR. Regulation of G proteins by covalent modification. Oncogene. 2001;20:1643–1652. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devary O, Heichal O, Blumenfeld A, Cassel D, Suss E, Barash S, Rubinstein CT, Minke B, Selinger Z. Coupling of photo-excited rhodopsin to inositol phospholipid hydrolysis in fly photoreceptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:6939–6943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.19.6939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolph PJ, Ranganathan R, Colley NJ, Hardy RW, Socolich M, Zuker CS. Arrestin function in inactivation of G protein-coupled receptor rhodopsin in vivo. Science. 1993;260:1910–1916. doi: 10.1126/science.8316831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolph PJ, Man Son Hing H, Yarfitz S, Colley NJ, Deer JR, Spencer M, Hurley JB, Zuker CS. An eye-specific Gb subunit essential for termination of the phototransduction cascade. Nature. 1994;370:59–61. doi: 10.1038/370059a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evanko DS, Thiyagarajan MM, Wedegaertner PB. Interaction with Gbeta gamma is required for membrane targeting and palmitoylation of Gα (s) and Gα (q) J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1327–1336. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evanko DS, Thiyagarajan MM, Siderovski DP, Wedegaertner PB. Gbeta gamma isoforms selectively rescue plasma membrane localization and palmitoylation of mutant Galphas and Galphaq. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:23945–23953. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101154200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fain GL, Matthews HR, Cornwall MC, Koutalos Y. Adaptation in vertebrate photoreceptors. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:117–151. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaidarov I, Krupnick JG, Falck JR, Benovic JL, Keen JH. Arrestin function in G protein-coupled receptor endocytosis requires phosphoinositide binding. EMBO J. 1999;18:871–881. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.4.871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie RC, Minke B. The trp gene is essential for a light-activated Ca2+ channel in Drosophila photoreceptors. Neuron. 1992;8:643–651. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90086-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie RC, Raghu P. Visual transduction in Drosophila. Nature. 2001;413:186–193. doi: 10.1038/35093002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochstrate P. Lanthanum mimicks the trp photoreceptor mutant of Drosophila in the blowfly Calliphora. J Comp Physiol A. 1989;166:179–187. doi: 10.1007/BF00193462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Potter CJ, Tao W, Li DM, Brogiolo W, Hafen E, Sun H, Xu T. PTEN affects cell size, cell proliferation and apoptosis during Drosophila eye development. Development. 1999;126:5365–5372. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.23.5365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanzaki M, Zhang YQ, Mashima H, Li L, Shibata H, Kojima I. Translocation of a calcium-permeable cation channel induced by insulin-like growth factor-I. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:165–170. doi: 10.1038/11086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiselev A, Socolich M, Vinos J, Hardy RW, Zuker CS, Ranganathan R. A molecular pathway for light-dependent photoreceptor apoptosis in Drosophila. Neuron. 2000;28:139–152. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosloff M, Elia N, Joel-Almagor T, Timberg R, Zars TD, Hyde DR, Minke B, Selinger Z. Regulation of light-dependent Gqa translocation and morphological changes in fly photoreceptors. EMBO J. 2003;22:459–468. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Montell C. Light-dependent translocation of visual arrestin regulated by the NINAC myosin III. Neuron. 2004;43:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SJ, Xu H, Kang LW, Amzel LM, Montell C. Light adaptation through phosphoinositide-regulated translocation of Drosophila visual arrestin. Neuron. 2003;39:121–132. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00390-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto H, Kurien BT, Takagi Y, Kahn ES, Kinumi T, Komori N, Yamada T, Hayashi F, Isono K, Pak WL, et al. Phosrestin I undergoes the earliest light-induced phosphorylation by a calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase in Drosophila photoreceptors. Neuron. 1994;12:997–1010. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90309-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minke B, Hardie RC. Genetic dissection of Drosophila photo-transduction. In: Stavenga DG, van der Hope DJN, Pugh E, editors. Molecular Mechanisms in Visual Transduction. Elsevier; North Holland: 2000. pp. 449–525. [Google Scholar]

- Montell C, Rubin GM. The Drosophila ninaC locus encodes two photoreceptor cell specific proteins with domains homologous to protein kinases and the myosin heavy chain head. Cell. 1988;52:722–757. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90413-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumby SM. Reversible palmitoylation of signaling proteins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:148–154. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orem NR, Dolph PJ. Loss of the phospholipase C gene product induces massive endocytosis of rhodopsin and arrestin in Drosophila photoreceptors. Vision Res. 2002;42:497–505. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(01)00229-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostroy SE. Characteristics of Drosophila rhodopsin in wild-type and norpA vision transduction mutants. J Gen Physiol. 1978;72:717–732. doi: 10.1085/jgp.72.5.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peretz A, Suss-Toby E, Rom-Glas A, Arnon A, Payne R, Minke B. The light response of Drosophila photoreceptors is accompanied by an increase in cellular calcium: effects of specific mutations. Neuron. 1994;12:1257–1267. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90442-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips AM, Bull A, Kelly LE. Identification of a Drosophila gene encoding a calmodulin-binding protein with homology to the trp phototransduction gene. Neuron. 1992;8:631–642. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90085-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan R, Stevens CF. Arrestin binding determines the rate of inactivation of the G protein-coupled receptor rhodopsin in vivo. Cell. 1995;81:841–848. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resh MD. Fatty acylation of proteins: new insights into membrane targeting of myristoylated and palmitoylated proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1451:1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(99)00075-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuss H, Mojet MH, Chyb S, Hardie RC. In vivo analysis of the Drosophila light-sensitive channels, TRP and TRPL. Neuron. 1997;19:1249–1259. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80416-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott K, Becker A, Sun Y, Hardy R, Zuker C. Gqa protein function in vivo: genetic dissection of its role in photoreceptor cell physiology. Neuron. 1995;15:919–927. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott K, Sun Y, Beckingham K, Zuker CS. Calmodulin regulation of Drosophila light-activated channels and receptor function mediates termination of the light response in vivo. Cell. 1997;91:375–383. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80421-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shieh BH, Niemeyer B. A novel protein encoded by the InaD gene regulates recovery of visual transduction in Drosophila. Neuron. 1995;14:201–210. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90255-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smotrys JE, Linder ME. Palmitoylation of intracellular signaling proteins: regulation and function. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:559–587. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele FR, Washburn T, Rieger R, O’Tousa JE. Drosophila retinal degeneration C (rdgC) encodes a novel serine/threonine protein phosphatase. Cell. 1992;69:669–676. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90230-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker H, Andjelkovic M, Oldham S, Laffargue M, Wymann MP, Hemmings BA, Hafen E. Living with lethal PIP3 levels: viability of flies lacking PTEN restored by a PH domain mutation in Akt/PKB. Science. 2002;295:2088–2091. doi: 10.1126/science.1068094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suss Toby E, Selinger Z, Minke B. Lanthanum reduces the excitation efficiency in fly photoreceptors. J Gen Physiol. 1991;98:849–868. doi: 10.1085/jgp.98.4.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunoda S, Zuker CS. The organization of INAD-signaling complexes by a multivalent PDZ domain protein in Drosophila photoreceptor cells ensures sensitivity and speed of signaling. Cell Calcium. 1999;26:165–171. doi: 10.1054/ceca.1999.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsunoda S, Sierralta J, Sun Y, Bodner R, Suzuki E, Becker A, Socolich M, Zuker CS. A multivalent PDZ-domain protein assembles signalling complexes in a G-protein-coupled cascade. Nature. 1997;388:243–249. doi: 10.1038/40805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vihtelic TS, Hyde DR, O’Tousa JE. Isolation and characterization of the Drosophila retinal degeneration B (rdgB) gene. Genetics. 1991;127:761–768. doi: 10.1093/genetics/127.4.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vihtelic TS, Goebl M, Milligan S, O’Tousa JE, Hyde DR. Localization of Drosophila retinal degeneration B, a membrane-associated phosphatidylinositoltransfer transfer protein. J Cell Biol. 1993;122:1013–1022. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.5.1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedegaertner PB. Lipid modifications and membrane targeting of G a. Biol Signal Recept. 1998;7:125–135. doi: 10.1159/000014538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Niemeyer B, Colley N, Socolich M, Zuker CS. Regulation of PLC-mediated signalling in vivo by CDP-diacylglycerol synthase. Nature. 1995;373:216–222. doi: 10.1038/373216a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T, Takeuchi Y, Komori N, Kobayashi H, Sakai Y, Hotta Y, Matsumoto H. A 49-kilodalton phosphoprotein in the Drosophila photoreceptor is an arrestin homolog. Science. 1990;248:483–486. doi: 10.1126/science.2158671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]