Introduction

Anisotropy is the property of being directionally dependent. Such property can be ubiquitously found in nature: phenomena as diverse as light polarization, seismic wave propagation, crystallization or magnetization are known to exhibit anisotropy.

In the heart, the term anisotropy is commonly used to refer to the directional variations of certain properties of propagation, most commonly, conduction velocity (CV).(Weidmann, 1970) However, anisotropy of repolarization has also been described.(Gotoh et al., 1997; Kanai and Salama, 1995; Taccardi et al., 2005) Anisotropy of CV in heart tissue was first described as recently as 1959.(Sano et al., 1959) The relevance of anisotropic conduction properties extends beyond normal propagation. Over the last decades anisotropy has been increasingly recognized as a potential substrate for abnormal rhythms and reentry, both in normal as well as pathological conditions.

The following review describes the mechanisms of anisotropy, its structural and functional determinants, and its roles in normal and abnormal propagation.

Mechanisms of Anisotropy

It has been long known that the myocardial fiber architecture is anisotropic, as fiber orientation is visible even macroscopically. The demonstration in 1954 that cardiac tissue is not a histological syncitium, but is rather comprised of individual myocytes completely bounded by membrane,(Sjostrand and Andersson, 1954) was followed by a description of the gap junctions and their distribution as mediators of intercellular communication.(Sjostrand et al., 1958) It was shown that the cellular architecture of the myocardium is anisotropic: myocardial cells are markedly elongated and form layers of tissue with sharply demarcated fiber orientation. Sano was the first to show that such fiber orientation impacts CV,(Sano et al., 1959) when isolated sheets or bundles of myocardium were paced, and a clear discrepancy between transverse (CVT) and longitudinal CV (CVL) was found. This was rapidly confirmed by other authors.(Clerc, 1976; Draper and Mya-Tu, 1959)

There is large variability in both the CV and the anisotropy ratio (AR = CVL/CVT) in different regions of the heart. Accordingly, the fastest CVL is found in Purkinje fibers (∼2 m/s)(Cranefield et al., 1971; Draper and Mya-Tu, 1959) and the slowest in the ventricular muscle (∼0.5 m/s).(Clerc, 1976; Roberts et al., 1979; Schalij et al., 1992) The highest AR is found in the crista terminalis of the right atrium (∼10), and the lowest in the ventricles (∼2).(Kleber and Rudy, 2004; Saffitz et al., 1994) These differences seem to be consistent with functionality: The crista terminalis delivers propagation rapidly from the sinus node superiorly towards the inferior right atrium and septum in the absence of a specialized atrial conduction system. In the ventricle, fiber orientation may serve predominantly a hemodynamic purpose, that is, to ensure that fiber contraction occurs in certain axis, since during normal propagation, most impulse conduction is delivered by the Purkinje fiber network, with ventricular muscle-to-muscle conduction (particularly in the transverse direction)(Schalij et al., 1992) playing a lesser role.

Continuous versus discontinuous propagation

In an isolated cell, changes in membrane voltage (Vm) are related to transmembrane ionic currents, and the charge these currents carry is solely used to discharge the membrane capacitance. If one couples multiple cells in a chain, it follows that Vm changes in one cell instantaneously impact the neighboring cells. More importantly, the coupling of neighboring cells affects how, in an individual cell, transmembrane ion currents alter the cell's own Vm.(Kleber and Rudy, 2004) When coupled to neighboring cells, the charge generated by transmembrane ion flow is divided between discharging the local membrane capacitance and depolarizing the membrane of downstream cells via the electrotonic axial current. Important parameters of this spatial coupling are the fiber radius, and the axial resistivity. Of note, in the bidomain representation of cardiac tissue, the extracellular medium is anisotropic as well, and extracellular resistivity plays a role as well as axial resistivity.

These continuous medium concepts successfully explain some experimental results,(Kleber and Rudy, 2004) such as macroscopic passive electrical properties of cardiac tissue,(Kleber and Riegger, 1987; Weidmann, 1970) and macroscopic gross proportionality of upstroke velocity with conduction velocity.(Buchanan et al., 1985) However, the mere non-syncitial cellular architecture of the myocardium creates two media to be trespassed by the electrical impulse: the cytoplasm (low resistivity) and the intercellular junctions (high resistivity). The continuous medium conceptualization, where both are lumped together, initially succeeded at explaining macroscopic phenomena. However, anisotropic conduction presented problems with this paradigm.

After the initial demonstration of anisotropy (Sano et al., 1959), several mechanistic hypotheses were proposed. Clerc used classic continuous cable theory to explain the directional CV differences based on different longitudinal and transverse axial resistances.(Clerc, 1976) Although axial resistances were indeed different, in Clerc's model, intracellular and intercellular resistances grouped as one. Cable theory would predict that faster (longitudinal) CVs would be accompanied by steeper action potential upstrokes (dV/dt), and slower CVs (transverse) would go along with slower upstrokes. However, Spach et al showed opposite experimental results: slower dV/dt during fast longitudinal propagation and faster dV/dT during slow transverse propagation (Spach et al., 1981). Such findings called for a reinterpretation of the data since they could only be explained if propagation was discontinuous at a microscopic level due to the presence of recurrent discontinuities of resistance created by myocyte-to-myocyte connections. It is obvious that transverse propagation of the action potential has to go trough more myocyte-to-myocyte connections per unit space than longitudinal conduction. Thus, during transverse conduction, a slower CV is accompanied by faster dV/dt upstrokes because the cells at the wavefront face less charge drain downstream the propagation direction, since there are more high-resistivity intercellular junctions to go through. Conversely, during longitudinal conduction, coupling leads to charge drain downstream the propagation: transmembrane ion fluxes at a given cell lead to less Vm change in that cell and slower AP upstroke because the charge they carry is used also to depolarize downstream cells.

Under this paradigm, the relationship between magnitude of Na current, action potential upstroke velocity, and CV become complex.(Kleber and Rudy, 2004) For example, if propagation approaches a boundary (no excitable cells downstream), the electrotonic current that drains current from the wavefront is reflected back to it, enhancing wavefront depolarization to an increase in upstroke velocity and CV. Interestingly, Vm feeds back ion channels and the peak INa is reduced.(Spach and Kootsey, 1985) In simulations, this has been shown to be due to reduced electrochemical driving force of Na ions.(Wang and Rudy, 2000) Thus, an inverse relationship between INa and upstroke velocity is created. In a conceptually opposite scenario, such as in an abrupt tissue expansion, the wavefront is exposed to an augmented current drain when approaches the expansion. This leads to an electrotonically decreased upstroke velocity and decreased CV.(Fast and Kleber, 1995; Wang and Rudy, 2000) There is an increase in peak INa, due to the reduced Vm and increased electrochemical driving force, despite the fact that prolonged partial depolarization inactivates Na channels and leads to a decreased Na conductance.(Wang et al., 2000)

Spach's seminal contribution marked a departure from classic cable theory, and stressed the impact of cellular architecture in propagation. More recently, experiments in synthetic, single-cell wide strands of cardiac cells using optical recordings of voltage propagation at a microscopic level have confirmed the discontinuous, “saltatory” nature of conduction,(Fast and Kleber, 1993; Rohr, 1992) whereby propagation is fast within a given cell (low intracellular resistance) but exhibits delays at intercellular junctions (high resistance). In these single cell strands (1-dimensional cable), 51% of the conduction time corresponded to junctional conduction. See Figure 1.

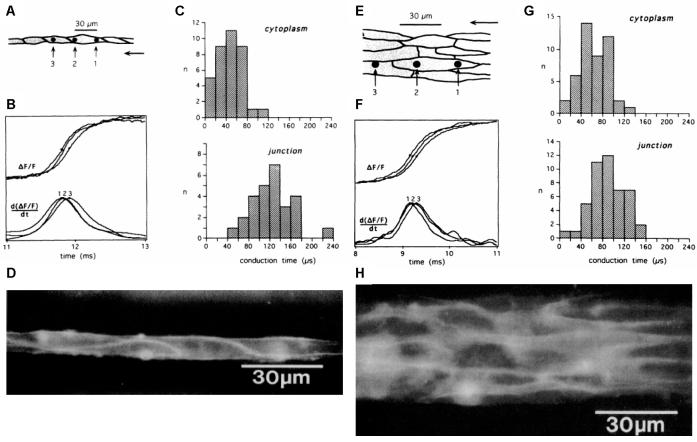

Figure 1.

Impulse propagation in one-dimensional cell chain (A through D) and 2-dimensional sheets (E through H). A, Schematic of the cell chain and the recording sites. Sites 1 and 2 are in the same cell. Site 3 is in the adjacent cell. Arrow indicates direction of propagation. B, top shows the upstroke of the actiion potential (optically measured) and bottom shows the first derivative. Sites 1 and 2 activate closer in time (simultaneous peak derivative, cytoplasmic conduction time of 30 μs). Site 3 activates after a delay (junctinal conduction time of 110 μs). C, Histograms of cytoplasmic (top) and junctional (bottom) conduction times. D, Fluorescent image of the cell chain. EH, Similar set of schematic (E), tracings (F), histograms (G) and fluorescent image for 2-D sheet. In 2-D, differences between cytoplasmic and junctional conduction times are less pronounced. (Fast and Kleber, 1993)

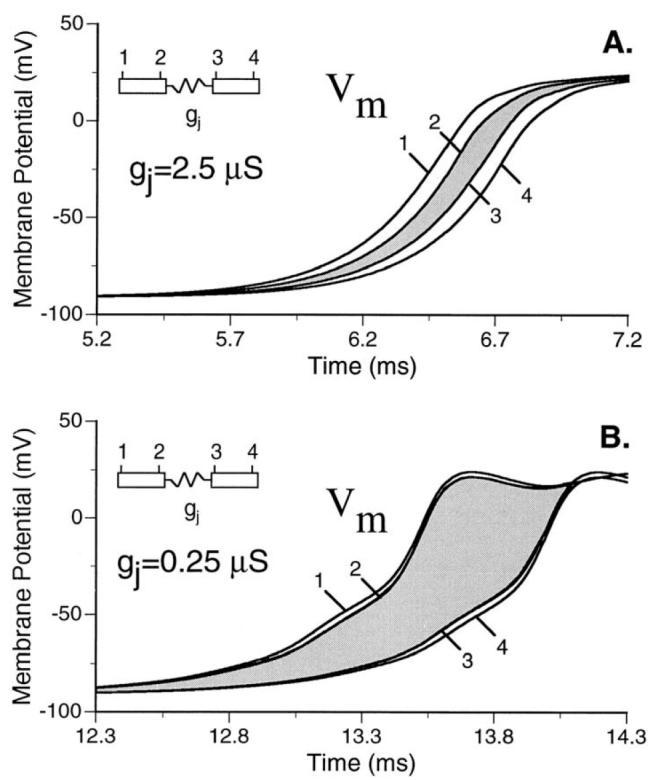

We have discussed how electrical phenomena at a single cell is affected by coupling it to others on either side. One step further then would be to consider two dimensional anisotropic sheets. In these, a given cell is coupled to several cells in the transverse as well as in the longitudinal direction. Fast and Kleber analyzed microscopic conduction patterns(Fast and Kleber, 1993) and showed that the junctional delay dropped to 22% of the total conduction time, suggesting that lateral cell-to-cell connections decrease the discontinuities innate to cell-to-cell propagation (the so-called “lateral averaging). (Figure 1) In their mathematical model they showed that this effect was due to lateral divergence of local excitatory current immediately before the junctions (so that intracytoplasmic conduction would be slowed), and lateral convergence of the current past the junctions (effectively “speeding up” junctional conduction). Further computer simulations by Shaw and Rudy(Shaw and Rudy, 1997) have confirmed that cellular coupling can modulate intracytoplasmic conduction times. (Figure 2). An additional parameter that arises when considering propagation in a 2-dimensional sheet is that of wavefront curvature (Cabo et al., 1994; Fast and Kleber, 1997). Intuitively put, if a wavefront is convex, the cells at of the wavefront face more non-activated cells than in a linear wavefront. In consequence, the charges carried by depolarizing currents are also used to depolarize those neighboring cells, leading to decreased slope of the action potential upstroke and decreased CV. The opposite would be true for a concave curvature.(Kleber and Rudy, 2004)

Figure 2.

Increase in intercellular conduction delay with decrease in gap junction conductance. Action potential upstrokes from the edge elements (see inset) of two adjoining cells for intercellular conductance of 2.5 μs (A) and intercellular conductance of 0.25 μs (B). For control coupling (A), intercellular conduction delay is approximately equal to intracellular conduction time. A 10-fold decrease in intercellular conductance (B) increases intercellular conduction time and decreases intracellular conduction time dramatically, resulting in gap junction dominance of overall conduction velocity. (Shaw and Rudy, 1997)

Finally, the three-dimensional architecture of myocardial tissue has to be considered. It has been shown (LeGrice et al., 1995) that the heart wall has a laminar structure, whereby anisotropic layers of 4-5 cells thick are wrapped around each other, with occasional bridging myocytes and extracellular clefts. The implications of such structure in anisotropic propagation are unclear, although the sheet laminar structure and the clefts would enhance discontinuous propagation, supporting the concept that transmural conduction is not isotropic (Hooks et al., 2002).

Structural Determinants of Anisotropy

The structural determinants of anisotropic conduction are cell geometry, cell size, and directional distribution of gap junctions and membrane ion channels.

Cell geometry

Adult cardiac myocytes have a rectangular shape with minor irregularities. Of note, even though the cell size is quite variable among different regions of the adult heart, the length-to-width ratio is relatively constant.(Kleber, 2002) Simply stated, if propagation is composed to cytoplasmic conduction (fast, low resistivity) and junctional conduction (slow, high resistivity), it follows that cell geometry (elongation) determines the number of junctions per unit space that propagation has to go through in different directions. In longitudinal propagation, along the long axis of the cell, the impulse travels through less junctions per unit space than in transverse propagation, hence the former experiences less delays than the latter.

Cell size

However, there are also differences in conduction properties depending on the cell size and distribution of gap junctions. Joyner in 1982 showed the interactions between cell length and intercellular resistivity in determining propagation success or failure and action potential characteristics.(Joyner, 1982) However, the roles of cell size in propagation was delineated later by Spach.(Spach et al., 2000) As a preamble, Fast and Kléber had found no differences in upstroke velocity in transverse vs longitudinal conduction in anisotropic neonatal rat myocyte cultures (Fast and Kleber, 1994), challenging the earlier findings of Spach et al.(Spach et al., 1981) This was initially attributed to the diffuse distribution of gap junctions in neonatal tissue, in contrast with the polarized, end-to-end distribution of adult tissue (Figure 3A). Adult and neonatal tissue were found to be equally anisotropic, i.e. had identical anisotropy ratios,(Spach et al., 2000) a finding that seemed to minimize the role of gap junction distribution in the generation of anisotropy, however, the cell-to-cell delays and upstroke velocities were greater for transverse propagation in adult tissues compared to longitudinal propagation in the adult, or to both longitudinal and transverse propagation in the neonate (Figure 3B) . In simulations using an adult, polarized gap junction configuration, cell-to-cell delays were greater in transverse than in longitudinal conduction, and in simulations of a neonatal (diffuse) gap junction distribution, the cell-to-cell delays were identical in either propagation direction. However, cell size was found to be more relevant to cell-to-cell delay and upstroke velocity than gap junction distribution, as shown by simulations in Figure 4, where larger cell size (with either diffuse or polarized gap junction distribution), was associated with high upstroke velocities and long intercellular conduction times during transverse propagation, and smaller cell size (with either diffuse or polarized gap junctions) had those parameters unchanged regardless of propagation direction. Therefore, during normal growth, “as the degree of coupling between cells (number of connexons per unit area of sarcolemma) decreases in relation to the size of cells, conduction becomes more discontinuous”.(Spach et al., 2000) Of note, similar anisotropic ratios were present in all gap junction configurations, suggesting that cell geometry (length-to width ratios) is a major determinant of anisotropy, and the cell size and gap junction distribution determine whether propagation is continuous or discontinuous.

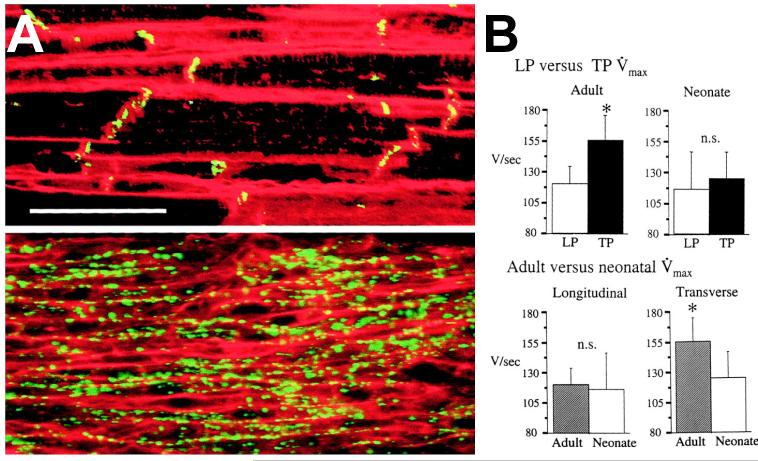

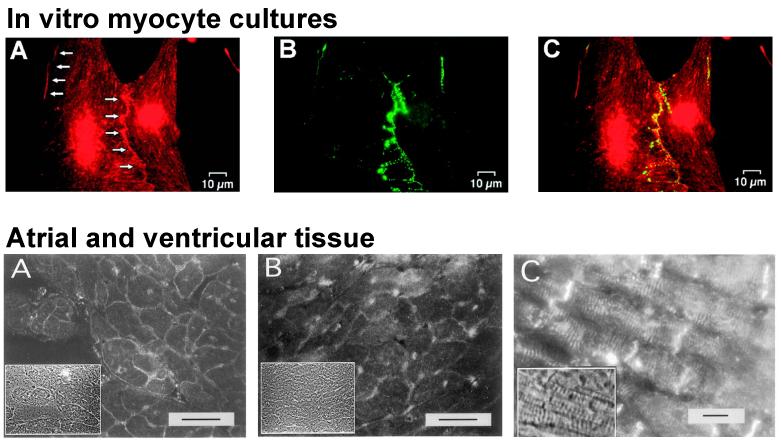

Figure 3.

A, Connexin43 distribution in relation to the cardiac myocyte surface in normal adult (top) and neonatal (bottom) canine left ventricular muscle. Gap junctions (green or yellow) were labeled with antibodies to connexin43. The sarcolemma (red), was labeled with wheat germ agglutinin. Bar=50 μm.. B, Action potential upstroke velocities (Vmax) in logitudinal vs transverse propagation in neonate vs adult preparations. Transverse Vmax increases with age. No directional dependence is seen in neonates.(Spach et al., 2000)

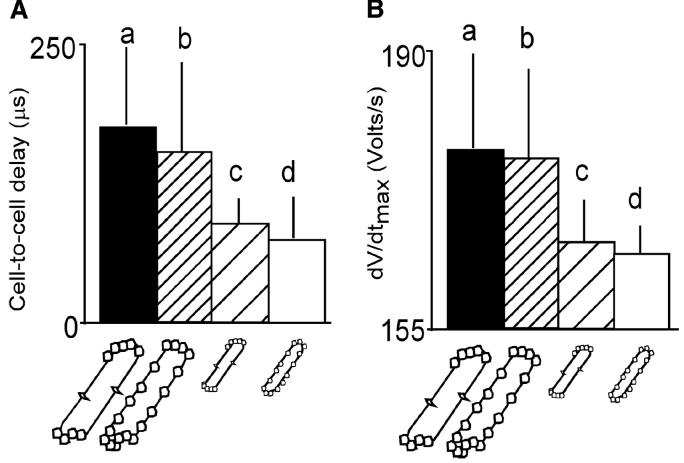

Figure 4.

Relation of cell-to-cell delays (A) and peak upstroke velocities (dV/dtmax in B) with respect to cell size and the distribution of the gap junctions. All data is from transverse conduction. Below each graph, the drawings of single cells represent each cellular network: a and d indicate adult and neonatal cellular networks, respectively; b, hypothetical network with adult cell size scaling but with neonatal gap junction distribution; and c, hypothetical network with neonatal cell size scaling but with adult gap junction distribution. Irrespective of gap junctional distribution, large cells have long intercellular delays and steep upstrokes compared to small cells. (Spach et al., 2000) as adapted in (Kleber and Rudy, 2004)

Gap junction and ion channel distribution

Gap junctions have an important influence in CV. Connexin (Cx) proteins form gap junctions and exist in several isoforms in the heart. Cx43 is the most abundant isoform, present ubiquitously but primarily in the ventricular muscle. Cx40 occurs in the atria and in the conduction system. Cx45 seems to be expressed uniformly during development but its expression in the adult seems restricted to the atrioventrcular node, the sinoatrial node, and in the conduction system. Interestingly, Cx45 expression is upregulated in heart failure.(Kalahasti et al., 2003) Gap junctions group themselves in plaques in the intercalated disks, containing variable amounts of individual channels,(Jongsma and Wilders, 2000) which are permeable to substances with a molecular weight of < 1 kDa. Intercellular coupling depends on single channel permeability (which varies with connexin type and charge of the permeating molecule), and the size of gap junction plaques (bigger plaques contain more channels). The concentration of gap junctions in the ends of the cells (Figure 3A) has a significant influence in coupling. Gap junctional conductance (gj) determines the intercellular resistivity, which modulates CV. Interestingly, for a given gj, intercellular resistivity is greater in the transverse direction than in the longitudinal direction(Jongsma and Wilders, 2000) (see below and Figure 7C), a phenomenon related to gap junction plaque size and connexin density. Figure 2 shows the effect of changing gap junctional conductance in intercellular conduction times and thus CV.(Shaw and Rudy, 1997)

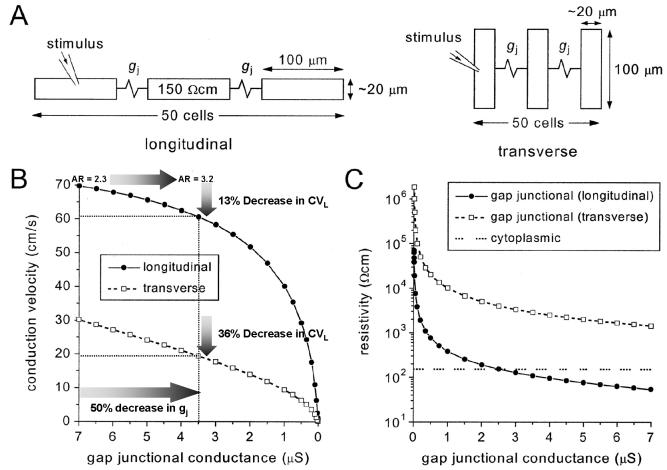

Figure 7.

Simulations of the effect of gap junctional conductance (gj) on conduction velocity. A, arrangement of the simulated longitudinal (left) and transverse (right) cable of cells. B, directional changes in CV as a function of gj. A 50% decrease in gj leads to a greater decrease in CVT than CVL, and to an increase in anisotropy ratio (AR). C, effective resistivity as a function of gj in both directions.(Jongsma and Wilders, 2000)

Similar to the aforementioned polarized distribution of gap junctions in the adult myocyte, sodium channels responsible for the action potential propagation localize at the ends of the cells(Cohen, 1996; Kucera et al., 2002; Maier et al., 2002) (Figure 5). In a simulation study,(Kucera et al., 2002) such distribution was shown to modulate the dependence of conduction on coupling through gap junctions. In the absence of gap junctional conductance, conduction could still be possible via local effects on the cleft potential caused by concentration of sodium channels at the junctions. The physiological relevance of this mechanism remains to be determined.

Figure 5.

Na channel colocalization with connexin at the sites of intercellular junctions. Top, cultured myocytes: A shows Na channels, B shows connexin 43, and C is a merged image. (Kucera et al., 2002) Bottom, immunolabeling of Na channel in transverse sections of atrial tissue (A), ventricular tissue (B) and longitudinal section of ventricular tissue. Insets are corresponding phase contrast images. Bar = 10 μm. (Cohen, 1996)

Functional Determinants of Anisotropy

As discussed, if the predominant parameters determining anisotropy are cell geometry, cell size and gap junction distribution, one would assume that given the fixed nature of these parameters, anisotropy would be a static property of myocardial conduction.

Steady-state vs transient anisotropy modulation

Indeed, when Spach et al measured CVs in different directions during premature impulses, he saw comparable decreases in CVL and CVT, so that there were no changes in AR (Spach et al., 1982a) (Figure 6). This was consistent with a solely ionic-channel mechanism underlying decreases in CVs upon premature stimulation. That is, premature stimulation would encroach upon the preceding action potential so that there would be less available Na channels and a slower upstroke of the action potential, leading to decreases in CV that would be equal in either direction. Indeed, this was consistent with Weidmann's report of unaltered intracytoplasmic and junctional resistivities after premature stimulations.(Weidmann, 1970)

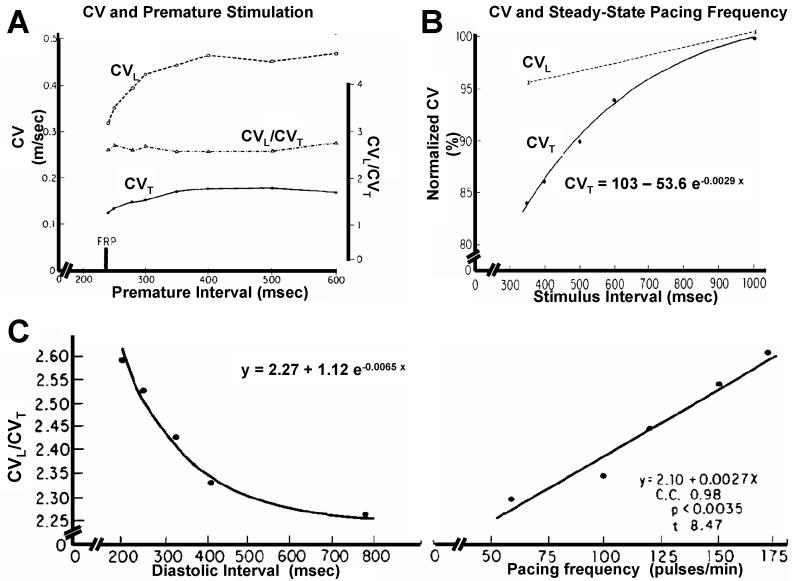

Figure 6.

Functional modulation of anisotropy. A, response of CV to premature stimulation. CVL and CVT decrease proportionally so that the is not significant change in anisotropy ratio (CVL/CVT). B, response to increasing steady-state pacing frequency. Small changes of CVL in the presence of an exponential decay of CVT. C, steady state increases in CVL/CVT as a function diastolic interval (left) or pacing frequency (right).(Spach et al., 1982a)

However Spach et al went on to measure CVs at different steady-state pacing frequencies.(Spach et al., 1982a) The results were quite divergent: it was shown that as steady-state pacing frequency was increased, CVT decreased to a greater extent (both in absolute as well as relative terms) than CVL, leading to rate-dependent increases in AR. In fact, CVT decreased exponentially (Figure 6B) whereas the decrease in CVL was too small to delineate a functional dependence. The AR was shown to increase exponentially when expressed as a function of decreasing diastolic intervals, or linearly when expressed as a function of pacing frequency (Figure 6C). Of note, Spach et al showed that the selective decrease in CVT could not be accounted for any changes in the action potential (the upstroke takeoff, and maximal upstroke velocities did not change with slowing of CV), and it was fully reversible upon decreases of pacing frequency. If the action potential was unchanged, then intercellular coupling must be susceptible to modulation by rate. Previously, decreased intercellular coupling had been shown to occur after intercellular injection of calcium,(De Mello, 1975) after increases in cytosolic sodium induced by digitalis,(Ando et al., 1981; De Mello, 1976; Weingart, 1977) and after prolonged rapid pacing.(Bredikis et al., 1981) Spach et al showed that the addition of ouabain itself lead to an AR increase and enhanced the AR's rate-dependent accentuation.(Spach et al., 1982a) Rate-dependent increases in AR have been confirmed subsequently.(Kadish et al., 1986; Koura et al., 2002)

Dynamic regulation of gap junctional conductance

Therefore, it is clear that anisotropy can be dynamically modulated, and that the mediator of this modulation is not related to the action potential, but to intercellular coupling. Gap junction channels behave as gated ion channels. Such gating can be both voltage- and chemically-mediated. Gap junctional conductance is modulated by transjunctional voltage,(Bukauskas and Verselis, 2004; Lin et al., 2005) by [H+]i(Francis et al., 1999) and [Ca2+]i,(White et al., 1990) by the phosphorylation state of the connexins,(Lampe and Lau, 2000; Moreno et al., 1994) and by extracellular fatty acid composition.(Burt et al., 1991) But how do changes in gap junctional conductance --which are expected to affect equally all intercellular couplings regardless of directionality-- lead to a selective decrease of transverse propagation velocity?

Simulations by Jongsma(Jongsma and Wilders, 2000) have shed some light into this phenomenon (Figure 7). First, as described above, for a given gj, intercellular resistivity is greater in the transverse direction, due to the polarized gap junction distribution (Figure 7C). Second, for a given change in gj, the impact on CV is greater in CVT than in CVL (Figure 7B). A 50% decrease in gj leads to a 13% decrease in CVL, and a 36% decrease in CVT, with an attendant increase in AR from 2.3 to 3.2. The fact that for a broad range of gj, longitudinal intercellular resistivity remains below intracytoplasmic resistivity underlies the insensitivity of longitudinal propagation to decreases in coupling, as shown experimentally.(Spach et al., 1982a)

Anisotropy and propagation of action potentials

Anisotropy and safety factor

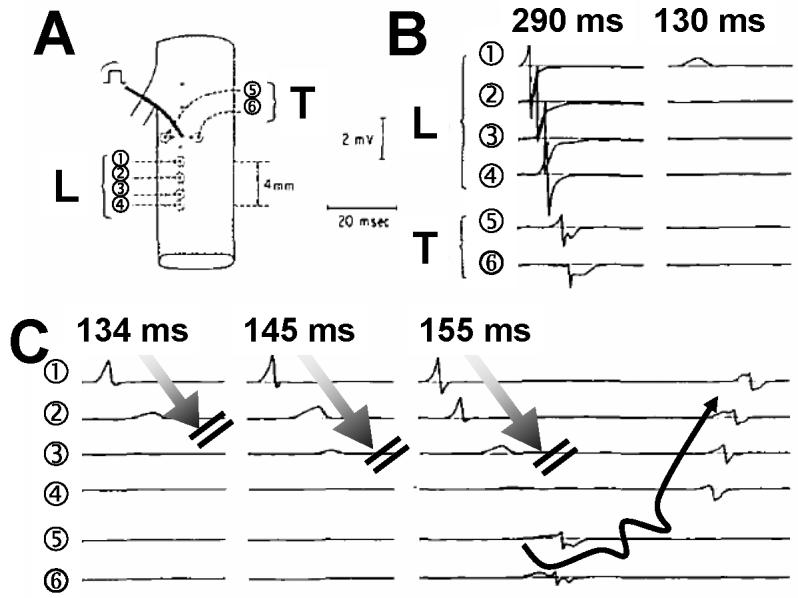

The concept of a parameter relating the amount of charge generated by a depolarized membrane to the amount of charge required to depolarized a neighboring segment cell was used by Schmitt and Schmitt in 1940(Schmitt, 1940) applied to continuous propagation in the giant squid axon, and has been refined quantitatively more recently.(Shaw and Rudy, 1997) In the setting of axonal conduction, a high safety factor is associated with fast CV and reliable conduction, and there is a direct correlation between the magnitude of Na current, the action potential upstroke velocity, CV, and safety factor. In discontinuous conduction, these relationships are more complex, as described above. In principle, the amount of current available to depolarize a cell depends on the action potential properties of the depolarizing source cell and on the impedance of the surrounding tissue. However, the latter feeds back on the former, and for a given tissue (whose cellular action potential properties are unchanged), changing propagation direction will change the effective impedance experienced by the propagating wavefront (higher on transverse direction) and hence the safety factor. Spach et al demonstrated lower action potential upstroke velocity in the longitudinal direction (Spach et al., 1981). To test the impact on safety factor, they performed premature stimulation (reducing the Na current) in a highly anisotropic preparation (the crista terminalis), and showed decremental longitudinal conduction and conduction block with preserved transverse conduction.(Spach et al., 1981) (Figure 8) Furthermore, it was shown that such unidirectional block could lead to reentry in the absence of heterogeneities in refractory periods. (Figure 8, see discussion below).(Spach et al., 1988; Spach et al., 1981)

Figure 8.

Induction of anisotropic reentry in an atrial pectinate muscle. A, schematic of the tissue with pacing site and recording electrode arrangement. Electrodes 1-4 record longitudinal (L) propagation, and 5-6 transverse(T) propagation. B, propagation during premature stimulation. At a long (290 ms) coupling interval, both longitudinal and transverse propagation succeed. At the refractory period (130 ms), both fail. C, propagation is decremental with block in the longitudinal direction (shaded arrows) at short coupling intervals (134, 145 ms) and fails in the transverse direction. At 155 ms coupling interval, decremental conduction and block occur in the longitudinal direction with preserved transverse conduction and reentry (curved arrow) (Spach et al., 1981).

The concept of greater safety factor in the transverse direction is controversial. Other studies have found diverging results (that is, earlier block in the transverse direction) in sheep epicardial slabs,(Delgado et al., 1990) aged atria,(Koura et al., 2002) or perfused rabbit epicardial tissue.(Schalij et al., 1992) Described below are potential explanations, related to anisotropic differences in excitability. Koura et al found an age-dependent change in the direction of preferential conduction block, whereby young atria experienced preferential block in the longitudinal direction, and aged atria in the transverse direction. Whereas all age groups were anisotropic, the AR increased with age. The authors correlated the change in location of block with the changes in connexin distribution and the extent of fatty and fibrous tissue interposed in between muscle fibers (Figure 9).(Koura et al., 2002) Thus, it seems that not all anisotropies are created equal, and that neonatal or young tissues can have anisotropy in the presence of continuous conduction, without directional changes in action potential upstroke,(Fast and Kleber, 1994) and with increased susceptibility to block in the longitudinal direction,(Koura et al., 2002; Spach et al., 1988; Spach et al., 1981) whereas anisotropy in adult or aged tissue has increased action potential upstroke velocity,(Spach et al., 1988) enhanced discontinuity of conduction,(Spach et al., 2000) and susceptibility to block increased in the transverse direction.(Koura et al., 2002) Increased cell size, transverse fibrous and fatty tissue, and connexin redistribution are the histological correlates of these changes.

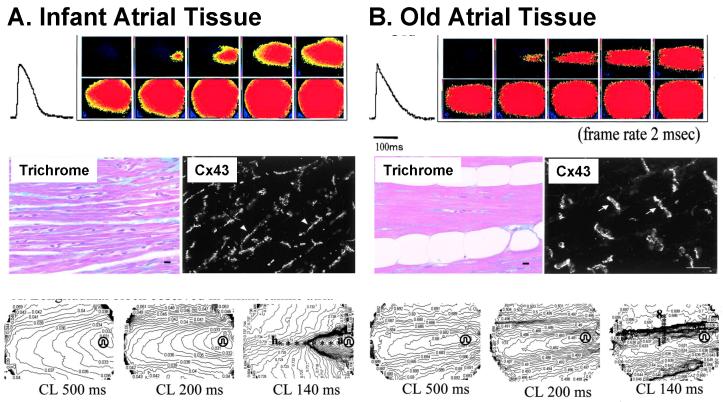

Figure 9.

Age-dependent changes in safety factor. A. Infant atrial tissue. Sequential propagation maps and action potential shape (top) show elliptical anisotropic propagation pattern. Homogenous fiber architecture (trichrome stain) and and diffuse connexin 43 (Cx43) expression are seen microscopically. (Middle panels). Isochronal propagation maps (1 ms isochrones) at different steady-state pacing cycle lengths (CL) shows longitudinal conduction block. B. Old atrial tissue shows a rectangular propagation pattern with enhanced anisotropy. Interposed fatty tissue between muscle fibers, polarized Cx43 distribution, and conduction block in the transverse direction. (Koura et al., 2002)

Changes in cellular uncoupling have been shown to have more pronounced effects in transverse conduction (see simulations described above and Figure 7). Experimentally, Delmar et al showed that transverse conduction had increased susceptibility to block upon administration of heptanol, a gap junction blocker.(Delmar et al., 1987) The interpretation of the literature is difficult when it comes to assess directional susceptibility to block, since the safety of conduction is hard to quantify experimentally, and methods to test it (via premature (Spach et al., 1988; Spach et al., 1981) or incremental(Koura et al., 2002) stimulation, or high K-induced reductions in excitability(Delgado et al., 1990)) are not directly comparable. It is of interest that incremental stimulation leads to increases of anisotropy ratio,(Spach et al., 1982a), and to transverse block,(Koura et al., 2002) findings also known to be generated by decreasing intercellular coupling.(Delmar et al., 1987; Jongsma and Wilders, 2000)

Anisotropy and excitability

Delgado et al(Delgado et al., 1990) compared current thresholds in an L-shaped preparation in which transverse and longitudinal conduction could be studied simultaneously in the respective arms of the L (Delgado et al., 1990). They also devised a similar arrangement in a computer simulation. They found theoretical and experimental evidence supporting a lower stimulation threshold in the transverse direction (Figure 10). Interestingly, they also found that, contrary to Spach's earlier observations,(Spach et al., 1988; Spach et al., 1981) the safety factor for propagation was lower in the transverse direction. In order to conciliate these apparently discrepant results, the authors suggested that there is a range of stimulus parameters (coupling interval and current output) at which the pulse delivered is below threshold in the longitudinal direction, but above threshold in the transverse direction, giving the appearance of longitudinal block with transverse conduction, despite the lower safety factor of the latter. There are important methodological differences that may have influenced the results as well. Instead of using premature stimulation to test safety of conduction they superfused the tissue with high potassium concentrations. Nevertheless, anisotropic modulation of excitability is a plausible explanation of the divergent experimental results.

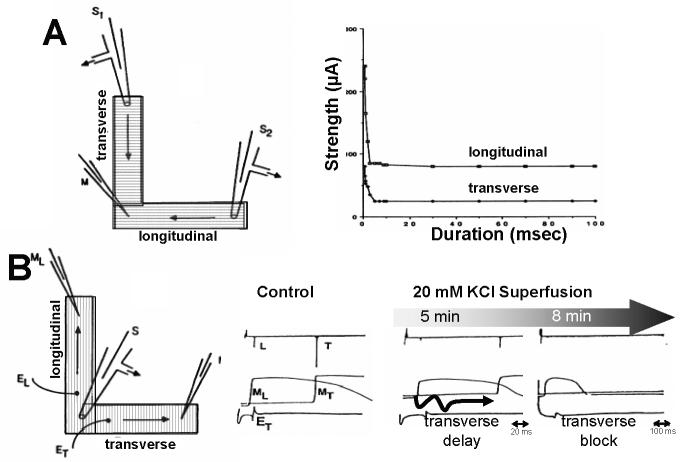

Figure 10.

Anisotropy, excitability and safety factor. A, using an L-shaped preparation, pacing was performed on either limb (one with transverse conduction, S1, and the other with longitudinal conduction, S2). Succesful conduction was verified by recording propagated potentials at the junction of both limbs (M). Current thresholds (right) in the strength-duration curve were consistently higher for longitudinal propagation. B, To test safety factor, the junction of both L-limbs was paced and membrane potentials were measured at the end of the transverse (MT) or the longitudinal (ML) limb. Control showed the expected time delay in MT, upon superfusion with 20 mM KCl, transverse delay occurred (5 min), followed by transverse block (8 min). (Delgado et al., 1990).

Anisotropy and repolarization: influence on action potential duration and repolarization sequence

We have described how cellular depolarization is primarily determined by ion channel kinetics and secondarily modulated by electrotonic voltage coupling to neighboring cells. Electrotonic coupling directly affects plasma membrane voltage, which has profound effects on ion channel gating and current kinetics. It is logical to assume that the same principles apply to repolarization.(Toyoshima and Burgess, 1978) Although repolarization is not an actively conducted phenomenon, it is governed by K channels that are subject voltage-mediated regulation. Thus, it follows that the repolarization kinetics of a given cell are affected by neighboring cells.

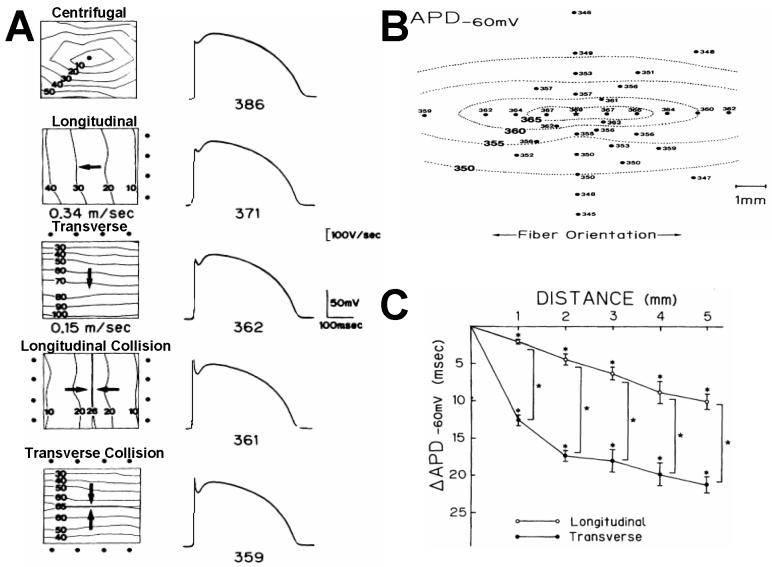

Consistent with the plausibility of the aforementioned, directional variations of repolarization have been reported.(Gotoh et al., 1997; Osaka et al., 1987) Cranefield and Hoffman showed that repolarization had features of a propagated process.(Cranefield and Hoffman, 1958) Osaka et al performed action potential recordings in the center of an anisotropic epicardial slab and paced from different sites to generate different propagation directions(Osaka et al., 1987) (Figure 11). During planar propagation, they found that the action potential duration was longest in a centrifugal (diagonal) direction, followed by longitudinal direction, and it was shortest during transverse propagation (Figure 11A). A spatial gradient of APDs was generated around the site of point stimulation, whereby APD decreased centrifugally from the site of stimulation, but the gradient was much steeper in the transverse direction. (Figure 11B). Interestingly, at sites of wave collision (dual stimulation at opposite sides), the APD was even shorter. A framework for understanding these phenomena is as follows: during any propagation, cells in the repolarizing phase of the action potential are located at the tail of the propagating wavelength, at the interface between fully repolarized tissue upstream and fully depolarized tissue downstream. During longitudinal propagation, the faster conduction velocity generates a longer wavelength, hence more cells are depolarized downstream, supplying greater electrotonical charge that tends to maintain the cells in the waveback depolarized and prolong the action potential. The opposite occurs during transverse propagation. This framework also explains the findings of shortest action potentials at sites of wavefront collision: at these sites, the wavefronts annihilate each other, so that at the time of repolarization, there are no depolarized cells downstream to supply electrotonic charge and the cells at this site are fully surrounded by repolarized cells, bringing the Vm to baseline at earlier times.

Figure 11.

Directional changes in action potential duration (APD). A, APD measurement in different propagation directions. Centrifugal (ellipsoid propagation generates the longest APD, followed by longitudinal, and transverse. APDs at collision sites are shortest. B, Spatial gradients of APD around point stimulation site. Gradient aligns with fiber orientation. C, APD gradients in the transverse and longitudinal direction. Transverse gradient are steeper.(Osaka et al., 1987).

It should be noted, however, that the aforementioned directional variations in APD occurred most pronouncedly at 30C, and that not all investigators have found similar results. Gotoh et al, at physiological temperatures, found decreases in APD as propagation proceeded from the pacing site in the transverse direction, but not in the longitudinal direction.(Gotoh et al., 1997) No directional impact on APD was found in an L-shaped preparation,(Delgado et al., 1990) epicardial guinea pig tissue (Girouard et al., 1996) or in swine left ventricles (Bertran et al., 2002).

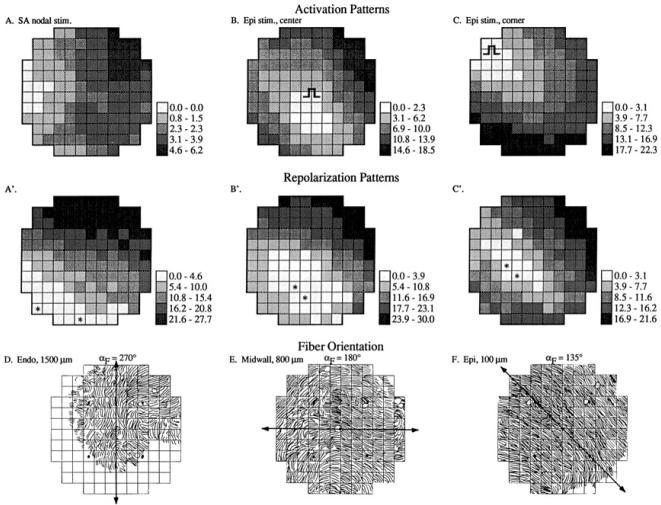

Intuitively, the spatial sequence of repolarization, as a non-actively propagated phenomenon, should depend on the activation sequence, and on the individual action potential duration characteristics. As discussed above, it is also expected that electronic influences could modulate repolarization sequence as well.(Joyner, 1986; Lesh et al., 1989; Rudy, 2005) Abildskov showed that the excitation sequence indeed determines the recovery of excitability in the dog.(Abildskov, 1976) However, in the guinea pig heart, Kanai and Salama showed divergent results (Kanai and Salama, 1995). They analyzed the impact of both depolarization sequence and fiber orientation on the repolarization sequence, using optical mapping techniques in perfused and showed that the epicardial repolarization consistently spread anisotropically along epicardial fiber orientation, irrespective of the depolarization sequence. Pacing from different sites (the atrium, and 2 sites in the epicardium) had profound impact on the depolarization sequence, but repolarization consistently started toward the apex and spread anistropically (Figure 12).(Kanai and Salama, 1995) The site of initiation of epicardial repolarization (towards the apex) corresponded to sites with shortest APD. From there, repolarization spread along fiber orientation. These findings support the concept of repolarization as a propagated phenomenon. In larger hearts, however, repolarization has been shown to mimic the depolarization sequence(Taccardi et al., 2005) and this underlies the observed phenomenon of T wave morphology changes upon pacing from different sies.

Figure 12.

Anisotropic repolarization sequence in guinea pig hearts. Top row, depolarization sequences during right atrial pacing (A), or in the center (B) or corner (C) of the epicardial surface. A clear change in activation sequence is seen. Middle row. Repolarization sequence corresponding to the different pacing sites. Lower row, fiber orientations in the endocardium (D), midwall (E), and epicardium (F). Repolarization sequences are remarkably similar to each other and have an elliptical shape, elongated along the orientation of epicardial fibers (lower row, right).(Kanai and Salama, 1995)

Anisotropy and reentry

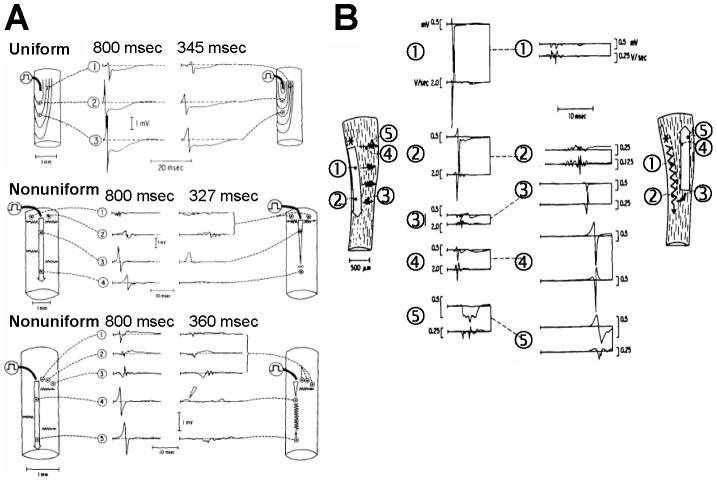

Uniform versus non-uniform anisotropy and vulnerability to reentry

The directional differences in propagation safely factor create a substrate for unidirectional block and reentry (Spach et al., 1981) (Figure 8). Aside from these intrinsic directional variations in normal tissue, aging is associated with enhancement of microstructural discontinuities due to increased tissue fibrosis and collagenous septa that particularly affect transverse conduction.(Koura et al., 2002; Spach and Dolber, 1986) The resulting substrate for conduction has been termed nonuniform anisotropy,(Spach and Dolber, 1986; Spach et al., 1988; Spach et al., 1982b) which leads to very slow, dissociated conduction with a characteristic zigzag propagation pattern, typically in the transverse direction, but also possible in the longitudinal direction (Spach et al., 1988) (Figure 13). Age, however, need not be involved in generating discontinuities, since normal myocardial fibers are organized in layers with interposed connective tissue. Such laminar structure(Legrice et al., 1997; LeGrice et al., 1995) has important implications to propagation and defibrillation.(Hooks et al., 2002) Enhanced microscopic discontinuities present in nonuniform anisotropy greatly increase the susceptibility to anisotropic reentry.(Spach et al., 1988) Very slow zigzag conduction has been reported in infarcted human tissue(de Bakker et al., 1993), and recently mapped with optical techniques in aged atrial tissue.(Koura et al., 2002)

Figure 13.

Nonuniform anisotropy and anisotropic reentry. A, normal and premature stimulation propagation patterns with or without nonuniform anisotropy. Numbers in msec are coupling intervals. In uniform anisotropy, premature stimulation does not alter propagation sequence. In nonuniform anisotropy, premature stimulation can lead to decremental longitudinal conduction and block, with zigzag transverse conduction (middle panel), or to zigzag conduction in both directions (lower panel). B, in nonuniform anisotropy with baseline propagation characterized by zigzag transverse conduction (left schematic and tracings), reentry can be induced by premature stimulation, in this case associated with transverse block, longitudinal zigzag conduction and retrograde activation, opposite to the case of uniform anisotropy shown in Figure 8. (Spach et al., 1988)

Anisotropic reentry as a paradigm of functional reentry

When originally described,(Spach et al., 1988; Spach et al., 1981) anisotropic reentry was a new form of functional reentry, which had been previously described experimentally by Allessie et al in the leading circle paradigm.(Allessie et al., 1977) First, the leading circle paradigm required the unidirectional conduction block and initial reentrant wave at the regions of longer refractory periods.(Allessie et al., 1976) Spach demonstrated that the regions sustaining anisotropic reentry had shorter action potential durations.(Spach et al., 1988) Anisotropic reentry is based on directionally-dependent parameters of conduction, rather than refractoriness and therefore constituted a new paradigm in itself. Second, the size of the reentrant circuit in anisotropic reentry (only 1-2 mm) is much smaller that that predicted by the leading circle paradigm. Third, the shape of the reentrant circuit in anisotropic reentry is naturally elongated along the fiber direction (as opposed to the leading “circle”).

Further work has provided additional characterization of anisotropic reentry. Schalij et al(Schalij et al., 2000; Schalij et al., 1992) created a model of anisotropic reentry using perfused rabbit hearts subjected to cryodestruction of four fifths of the myocardial wall so that only the anisotropic epicardial layer survived. They showed that anisotropic reentry traveled around a functional line of block (Z-shaped) parallel to the fiber orientation, and had marked conduction velocity heterogeneity depending on whether the wavefront was propagating in the longitudinal or transverse direction. Along the line of block, there were double potentials due to electrotonic influences during propagation on either side. Pronounced curvature at the pivot points of the circuit lead to further conduction slowing and the creation of an excitable gap and the short arms of the Z-shaped core.(Fast and Kleber, 1997; Schalij et al., 2000)

All forms of functional reentry are currently considered variations of spiral waves,(Kleber and Rudy, 2004) a generic form of self-sustained propagation present in many natural phenomena such as hurricanes, certain chemical reactions, or black holes. Spiral wave properties such as core shape and stability and the excitable gap length depend on certain parameters, the most important ones being wavelength (CV × APD) and radius of the curvature.(Fast, 1990; Kleber and Rudy, 2004) Depending on these, spiral waves can have circular or Z-shaped tip trajectories, which can be stable or unstable. Of note, the wavelength of a spiral wave is not stable throughout the reentrant pathway(Girouard et al., 1996) and factors such as curvature and underlying fiber orientation determine its variations.(Girouard et al., 1996; Valderrabano, 2004)

One particular form of reentry in which anisotropy plays a crucial role is that created by strong unipolar pacing, where the shape of virtual electrodes is modulated by intracellular and extracellular anisotropies and may lead to quatrefoil reentry.(Lin et al., 1999)

Unidirectional versus bidirectional anisotropy: impact of fiber orientation transitions in propagation and reentry

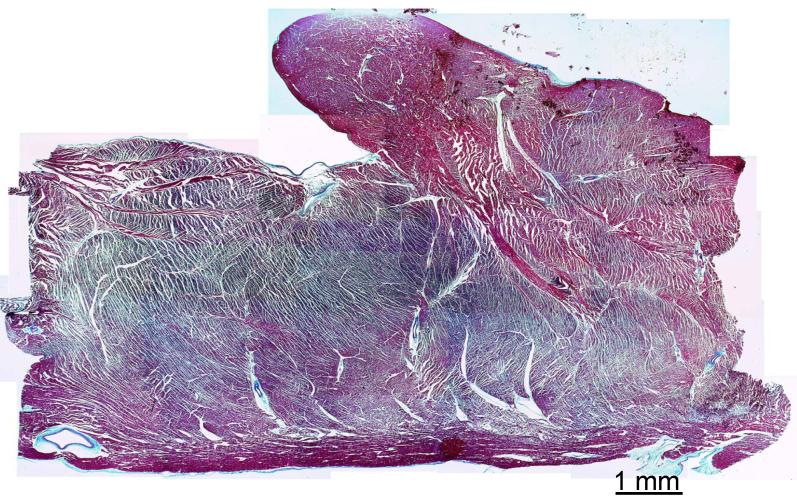

The heart is anatomically complex with different fiber directions in different regions, sometimes in direct apposition (Figure 14). Thus, the electrical impulse may abruptly switch from longitudinal to transverse conduction. Such transitions can from substrates for reentry upon premature stimulation.(Spach et al., 1982b) During premature stimulation, antegrade unidirectional conduction block can arise at the transition between longitudinal and transverse fibers(Spach et al., 1982b) (Figure 15). The transition itself can then be available for retrograde conduction, thereby completing the reentrant circuit. Spach et al showed in computer simulations that the abrupt delays and conduction block at the transition of different fiber orientations could only be accounted for by an abrupt change in effective axial resistivity in the direction of propagation.(Spach et al., 1982b)

Figure 14.

Trichrome stain of a swine left ventricular wall at the insertion of the papillary muscle. Note different fiber orientations, the vessels, and clefts in between fibers. From the author's file.

Figure 15.

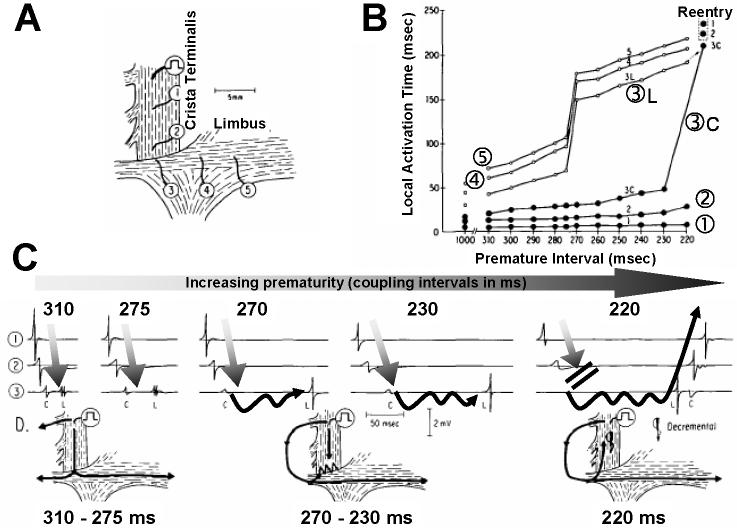

Fiber orientation transitions and reentry. A, schematic of the preparation and electrode position. The crista terminalis (longitudinal conduction) was apposed to the limbus (transverse conduction). B, local activation times with increasing prematurity. With decreasing coupling interval, delays in conduction toward the limbus (sites 3L, 4 and 5) occur, with a jump (at 270 ms) and induction of reentry. C, Propagation patterns across the transition. Site 3 detects both activations from the crista (3C) and the limbus (3L). Progressive delays between the two components is seen. At 220 ms coupling interval, there is unidirectional longitudinal block at site 3C and retrograde conduction with reentry.(Spach et al., 1982b)

Bursac et al developed an in vitro model of fiber orientation transitions using patterned neonatal myocyte cultures (Figure 16).(Bursac et al., 2002) Using that model, we found that spontaneous spiral wave generation was significantly more common than in isotropic cultures (82% vs 28% of cultures, p<0.005), and that spiral waves in this substrate were spatiotemporally stable and typically (78%) anchored near the transition of fiber orientations (Figure 16).(Valderrabano, 2004)

Figure 16.

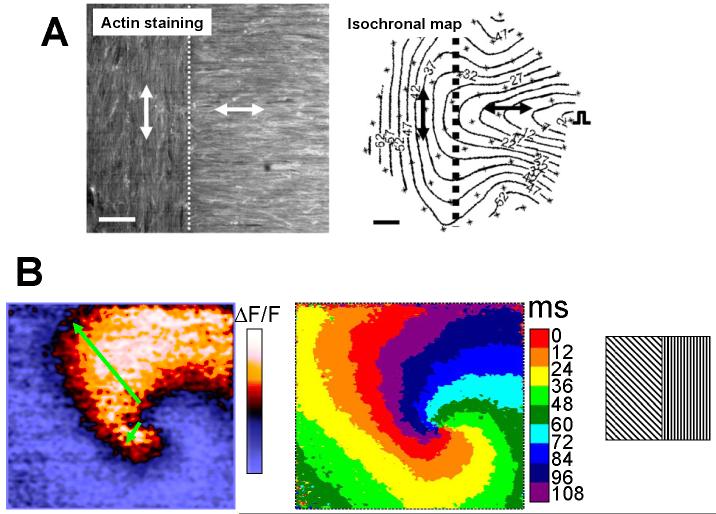

Anisotropic cultured myocyte model. A, Patterned cultures can generate different fiber orientations in different portions of the culture, as shown with actin staining, which have anistropic conduction (Bursac et al., 2002). B, Stable spiral wave anchored at the transition of fiber orientations (schematic in the right). Note the different wavelength of the spiral in the different directions (green arrows), and the different local conduction velocities in the isochronal map.

Anisotropy during fibrillation

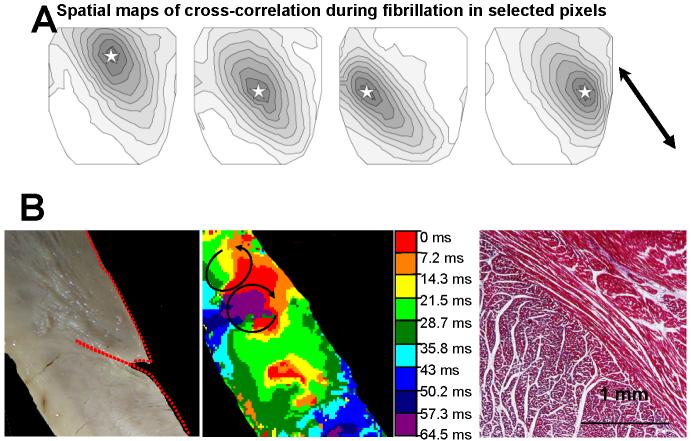

Fibrillation is characterized by multiple meandering activation wavelets. Although the global mechanisms of fibrillation remain under debate, the impact of the underlying cardiac anatomy and its anisotropy on the propagation patterns is beyond question (de Bakker et al., 2005). Fiber orientation and rotation have important influences in spiral wave (or scroll wave, its three-dimensional counterpart) dynamics and spatiotemporal stability.(Fenton and Karma, 1998; Qu et al., 2000) Analysis of fibrillation is limited by the restricted access to electrical events. Mapping studies have focused on endocardial or epicardial events, or transmural events using plunge-needle electrodes that necessarily introduce tissue damage. Choi et alperformed optical mapping in fibrillating rabbit hearts and performed cross-correlation and mutual information analysis of locations in the mapped field relative to neighboring locations (Choi et al., 2003). As expected from the fact that fibrillation is caused by wavelets that activate portions of tissue at once, they found that activations at individual sites during ventricular fibrillation correlate with activations in nearby locations. Interestingly, spatial maps of the correlation (by either mutual information or cross-correlation) showed that the agreement of given sites with their neighbor sites did not decrease radially in all directions, but rather ellipitically. The long axis of these elliptical correlations aligned with fiber orientation (Figure 17).(Choi et al., 2003)

Figure 17.

Anisotropy during fibrillation. A, maps of cross-correlation of activations in 4 different sites (stars). A gradient (from high to low) is seen that is elongated along fiber orientation (arrow). (Choi et al., 2003) B, transient transmural reentry during fibrillation anchored to a transition of fiber orientation. (Valderrabano et al., 2001)

We used ventricular wedge preparations with exposed cut transmural surfaces to gain insights into the transmural events during ventricular fibrillation.(Valderrabano et al., 2003; Valderrabano et al., 2001; Valderrabano et al., 2002) We found that episodes of intramural reentry localized in areas of abrupt fiber orientation change (Figure 17), supporting Spach's previous descriptions. These fiber orientation changes, prominently found in the papillary muscle root, are thought to underlie the tendency for the papillary muscle to anchor reentry in different experimental models of fibrillation.(Kim et al., 1999; Samie et al., 2001; Wu et al., 2004)

During fibrillation, wavelets are perpetuated by continuous wavebreak. Sites of wavebreak are surrounded by cells encompassing the full spectrum of activation states, from fully depolarized to fully repolarized, are hence called phase singularities, and are thought to be drivers of fibrillation.(Gray et al., 1998) While the mechanisms of wavebreak are debated, a correlation between locations of anatomical complexities, including apposition of fibers of different orientation (bidirectional anisotropy) during ventricular fibrillation was found.(Valderrabano et al., 2003) Recently, Chou et al stressed the relevance of complex anisotropy in the junction of the pulmonary veins with the left atrium in the mechanisms of atrial fibrillation.(Chou et al., 2005)

Anisotropy in pathological states: ischemia, post-myocardial infarction and heart failure

The roles of myocardial architecture in arrhythmogenesis in pathological states have been recently reviewed.(Peters and Wit, 1998) We will specifically focus on alterations of anisotropy.

Ischemia

Acute ischemia has profound effects on the action potential. Cellular coupling is also affected so that very slow conduction (otherwise not possible) ensues.(Quan and Rudy, 1990) Decreases in gap junctional conductance within minutes of ischemia (Hoyt et al., 1990) mediate this phenomenon, likely to be caused by connexin 43 dephosphorylation,(Beardslee et al., 2000) internalization, and lateralization (Figure 18). Chronic ischemia in the absence of infarction is associated with down-regulation of connexin 43 expression and decreased gap junction size.(Kaprielian et al., 1998; Peters et al., 1993)

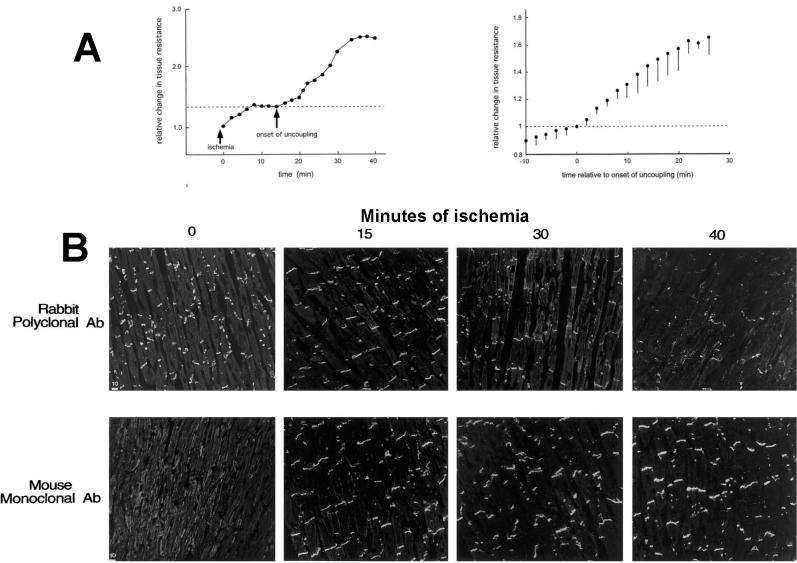

Figure 18.

Effects of ischemia in tissue coupling and their correlation with gap junction changes. A, time course of tissue uncoupling during ischemia. B, changes in total Cx43 (rabbit polyclonal) and dephosphorylated Cx43 (mouse monoclonal). With progressive ischemia, total Cx43 appears to decrease, whereas dephosphorylated Cx43 increases. Total Cx43 does not actually decrease, but rather is internalized.(Beardslee et al., 2000)

Post-myocardial infarction

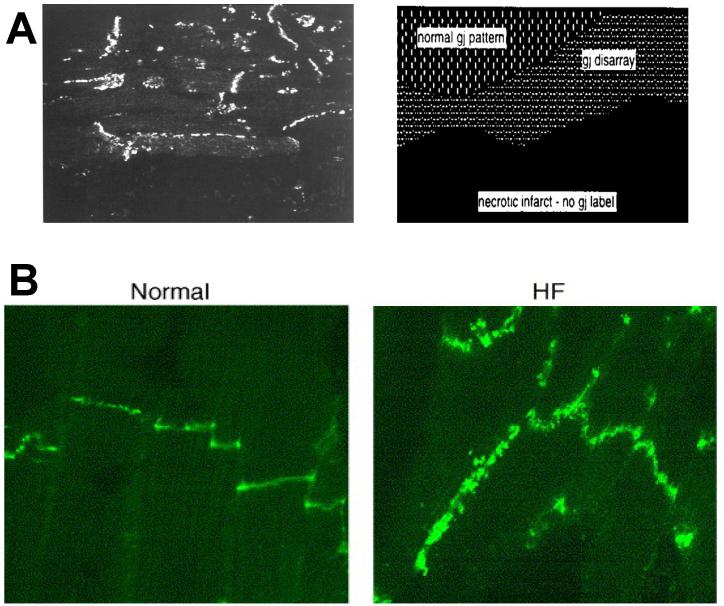

After a myocardial infarction, the surviving rim of epicardial tissue overlying the scar undergoes significant remodeling. Although these myocytes are structurally normal, they have redistribution (lateralization) of connexin molecules so that the polarization is lost.(Figure 19).(Smith et al., 1991) This adverse remodeling has been correlated with the presence of slowing of CV (particularly transverse to fiber orientation, with enhanced anisotropy(Dillon et al.)) and inducible tachycardia circuits(Dillon et al., 1988; Peters et al., 1997) and wavebreak during ventricular fibrillation.(Ohara et al., 2001) In the chronic phase of myocardial infarction, fibrous tissue is interposed between surviving myocardial fibers,(Ursell et al., 1985) further increasing structural discontinuities.(Spach et al., 1988) It should be noted that fibroblasts are capable of electrotonic transmission of the electrical impulse.(Gaudesius et al., 2003)

Figure 19.

Connexin distribution changes heart disease. A. Cx43 disarray in the periinfacrt border zone. Near the necrotic infarct there is lateralization of Cx43 as shown in fluorescent imaging, in contrast with normal polarized distribution of normal tissue (upper portion). (Peters et al., 1997) B. Cx43 lateralization in nonischemic, pacing-induced heart failure (HF), is a diffuse process. (Akar et al., 2004)

Nonischemic heart failure

The conduction abnormalities of nonischemic heart failure have been recently reviewed.(Akar and Tomaselli, 2005) CV has been reported to increase(Anderson et al., 1993; Cooklin et al., 1998; Toyoshima et al., 1982; Wiegerinck et al., 2006) and decrease(Akar et al., 2004; Hall et al., 2000; Laurita et al., 2003) with heart failure, which likely reflects heterogeneity of the disease and the experimental models. Akar et al studied CV properties in a model of pacing-induced heart failure and found uniformly decreased CV without changes in anisotropy ratio. The overall CV slowing was correlated with lateral redistribution and decreases of connexin 43 expression,(Poelzing and Rosenbaum, 2004) and increases in the dephosphorylated form of connexin 43 in ventricular muscle.(Akar et al., 2004) There were no changes in myocyte size. The findings seem to be model-specific, since most recently, using a heart failure model caused by pressure and volume overload, it was shown that CV (both in transverse and longitudinal direction increased due to increases in cell size.(Wiegerinck et al., 2006)

Conclusions

Anisotropy is an important property of normal impulse propagation but can participate in the genesis of abnormal rhythms as well. Disease processes can profoundly modulate tissue anisotropy and enhance its contribution arrhythmogenesis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abildskov JA. Effects of activation sequence on the local recovery of ventricular excitability in the dog. Circ Res. 1976;38:240–3. doi: 10.1161/01.res.38.4.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akar FG, Spragg DD, Tunin RS, Kass DA, Tomaselli GF. Mechanisms underlying conduction slowing and arrhythmogenesis in nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2004;95:717–25. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000144125.61927.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akar FG, Tomaselli GF. Conduction abnormalities in nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy: basic mechanisms and arrhythmic consequences. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2005;15:259–64. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allessie MA, Bonke FI, Schopman FJ. Circus movement in rabbit atrial muscle as a mechanism of tachycardia. II. The role of nonuniform recovery of excitability in the occurrence of unidirectional block, as studied with multiple microelectrodes. Circ Res. 1976;39:168–77. doi: 10.1161/01.res.39.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allessie MA, Bonke FI, Schopman FJ. Circus movement in rabbit atrial muscle as a mechanism of tachycardia. III. The “leading circle” concept: a new model of circus movement in cardiac tissue without the involvement of an anatomical obstacle. Circ Res. 1977;41:9–18. doi: 10.1161/01.res.41.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson KP, Walker R, Urie P, Ershler PR, Lux RL, Karwandee SV. Myocardial electrical propagation in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:122–40. doi: 10.1172/JCI116540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando S, Kodama I, Ikeda N, Toyama J, Yamada K. Effect of ouabain on electrical coupling of rabbit atrial muscle fibers. Jpn Circ J. 1981;45:1050–5. doi: 10.1253/jcj.45.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardslee MA, Lerner DL, Tadros PN, Laing JG, Beyer EC, Yamada KA, Kleber AG, Schuessler RB, Saffitz JE. Dephosphorylation and intracellular redistribution of ventricular connexin43 during electrical uncoupling induced by ischemia. Circ Res. 2000;87:656–62. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.8.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertran G, Biagetti MO, Valverde E, Arini PD, Quinteiro RA. Lack of effect of conduction direction on action potential durations in anisotropic ventricular strips of pig heart. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2002;13:380–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2002.00380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredikis J, Bukauskas F, Veteikis R. Decreased intercellular coupling after prolonged rapid stimulation in rabbit atrial muscle. Circ Res. 1981;49:815–20. doi: 10.1161/01.res.49.3.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan JW, Jr., Saito T, Gettes LS. The effects of antiarrhythmic drugs, stimulation frequency, and potassium-induced resting membrane potential changes on conduction velocity and dV/dtmax in guinea pig myocardium. Circ Res. 1985;56:696–703. doi: 10.1161/01.res.56.5.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukauskas FF, Verselis VK. Gap junction channel gating. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1662:42–60. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bursac N, Parker KK, Iravanian S, Tung L. Cardiomyocyte cultures with controlled macroscopic anisotropy: a model for functional electrophysiological studies of cardiac muscle. Circ Res. 2002;91:e45–54. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000047530.88338.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt JM, Massey KD, Minnich BN. Uncoupling of cardiac cells by fatty acids: structure-activity relationships. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:C439–48. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1991.260.3.C439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabo C, Pertsov AM, Baxter WT, Davidenko JM, Gray RA, Jalife J. Wave-front curvature as a cause of slow conduction and block in isolated cardiac muscle. Circ Res. 1994;75:1014–28. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.6.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi BR, Liu T, Lavasani M, Salama G. Fiber orientation and cell-cell coupling influence ventricular fibrillation dynamics. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2003;14:851–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2003.02522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou CC, Nihei M, Zhou S, Tan A, Kawase A, Macias ES, Fishbein MC, Lin SF, Chen PS. Intracellular calcium dynamics and anisotropic reentry in isolated canine pulmonary veins and left atrium. Circulation. 2005;111:2889–97. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.498758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clerc L. Directional differences of impulse spread in trabecular muscle from mammalian heart. J Physiol. 1976;255:335–46. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SA. Immunocytochemical localization of rH1 sodium channel in adult rat heart atria and ventricle. Presence in terminal intercalated disks. Circulation. 1996;94:3083–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.12.3083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooklin M, Wallis WR, Sheridan DJ, Fry CH. Conduction velocity and gap junction resistance in hypertrophied, hypoxic guinea-pig left ventricular myocardium. Exp Physiol. 1998;83:763–70. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1998.sp004157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranefield PF, Hoffman BF. Propagated repolarization in heart muscle. J Gen Physiol. 1958;41:633–49. doi: 10.1085/jgp.41.4.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cranefield PF, Klein HO, Hoffman BF. Conduction of the cardiac impulse. 1. Delay, block, and one-way block in depressed Purkinje fibers. Circ Res. 1971;28:199–219. doi: 10.1161/01.res.28.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bakker JM, Stein M, van Rijen HV. Three-dimensional anatomic structure as substrate for ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2:777–9. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bakker JM, van Capelle FJ, Janse MJ, Tasseron S, Vermeulen JT, de Jonge N, Lahpor JR. Slow conduction in the infarcted human heart. ‘Zigzag’ course of activation. Circulation. 1993;88:915–26. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.3.915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Mello WC. Effect of intracellular injection of calcium and strontium on cell communication in heart. J Physiol. 1975;250:231–45. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp011051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Mello WC. Influence of the sodium pump on intercellular communication in heart fibres: effect of intracellular injection of sodium ion on electrical coupling. J Physiol. 1976;263:171–97. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado C, Steinhaus B, Delmar M, Chialvo DR, Jalife J. Directional differences in excitability and margin of safety for propagation in sheep ventricular epicardial muscle. Circ Res. 1990;67:97–110. doi: 10.1161/01.res.67.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmar M, Michaels DC, Johnson T, Jalife J. Effects of increasing intercellular resistance on transverse and longitudinal propagation in sheep epicardial muscle. Circ Res. 1987;60:780–5. doi: 10.1161/01.res.60.5.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon SM, Allessie MA, Ursell PC, Wit AL. Influences of anisotropic tissue structure on reentrant circuits in the epicardial border zone of subacute canine infarcts. Circ Res. 1988;63:182–206. doi: 10.1161/01.res.63.1.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper MH, Mya-Tu M. A comparison of the conduction velocity in cardiac tissues of various mammals. Q J Exp Physiol Cogn Med Sci. 1959;44:91–109. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1959.sp001379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fast VE,IR, Krinsky VI. Transition from circular tolinear rotation of a vortex in an excitable cellular medium. Phys Lett A. 1990;151:157–161. [Google Scholar]

- Fast VG, Kleber AG. Microscopic conduction in cultured strands of neonatal rat heart cells measured with voltage-sensitive dyes. Circ Res. 1993;73:914–25. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.5.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fast VG, Kleber AG. Anisotropic conduction in monolayers of neonatal rat heart cells cultured on collagen substrate. Circ Res. 1994;75:591–5. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.3.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fast VG, Kleber AG. Block of impulse propagation at an abrupt tissue expansion: evaluation of the critical strand diameter in 2- and 3-dimensional computer models. Cardiovasc Res. 1995;30:449–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fast VG, Kleber AG. Role of wavefront curvature in propagation of cardiac impulse. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;33:258–71. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(96)00216-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton F, Karma A. Vortex dynamics in three-dimensional continuous myocardium with fiber rotation: Filament instability and fibrillation. Chaos. 1998;8:20–47. doi: 10.1063/1.166311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis D, Stergiopoulos K, Ek-Vitorin JF, Cao FL, Taffet SM, Delmar M. Connexin diversity and gap junction regulation by pHi. Dev Genet. 1999;24:123–36. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1999)24:1/2<123::AID-DVG12>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudesius G, Miragoli M, Thomas SP, Rohr S. Coupling of cardiac electrical activity over extended distances by fibroblasts of cardiac origin. Circ Res. 2003;93:421–8. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000089258.40661.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girouard SD, Pastore JM, Laurita KR, Gregory KW, Rosenbaum DS. Optical mapping in a new guinea pig model of ventricular tachycardia reveals mechanisms for multiple wavelengths in a single reentrant circuit. Circulation. 1996;93:603–13. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.3.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh M, Uchida T, Fan W, Fishbein MC, Karagueuzian HS, Chen PS. Anisotropic repolarization in ventricular tissue. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:H107–13. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.1.H107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray RA, Pertsov AM, Jalife J. Spatial and temporal organization during cardiac fibrillation. Nature. 1998;392:75–8. doi: 10.1038/32164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall DG, Morley GE, Vaidya D, Ard M, Kimball TR, Witt SA, Colbert MC. Early onset heart failure in transgenic mice with dilated cardiomyopathy. Pediatr Res. 2000;48:36–42. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200007000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooks DA, Tomlinson KA, Marsden SG, LeGrice IJ, Smaill BH, Pullan AJ, Hunter PJ. Cardiac microstructure: implications for electrical propagation and defibrillation in the heart. Circ Res. 2002;91:331–8. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000031957.70034.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt RH, Cohen ML, Corr PB, Saffitz JE. Alterations of intercellular junctions induced by hypoxia in canine myocardium. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:H1439–48. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.258.5.H1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongsma HJ, Wilders R. Gap junctions in cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 2000;86:1193–7. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.12.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyner RW. Effects of the discrete pattern of electrical coupling on propagation through an electrical syncytium. Circ Res. 1982;50:192–200. doi: 10.1161/01.res.50.2.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joyner RW. Modulation of repolarization by electrotonic interactions. Jpn Heart J. 1986;27(Suppl 1):167–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadish AH, Spear JF, Levine JH, Moore EN. The effects of procainamide on conduction in anisotropic canine ventricular myocardium. Circulation. 1986;74:616–25. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.74.3.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalahasti V, Nambi V, Martin DO, Lam CT, Yamada D, Wilkoff BL, Niebauer MJ, Jaeger FJ, Tchou PJ, Chung MK. QRS duration and prediction of mortality in patients undergoing risk stratification for ventricular arrhythmias. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:798–803. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00886-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai A, Salama G. Optical mapping reveals that repolarization spreads anisotropically and is guided by fiber orientation in guinea pig hearts. Circ Res. 1995;77:784–802. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.4.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaprielian RR, Gunning M, Dupont E, Sheppard MN, Rothery SM, Underwood R, Pennell DJ, Fox K, Pepper J, Poole-Wilson PA, Severs NJ. Downregulation of immunodetectable connexin43 and decreased gap junction size in the pathogenesis of chronic hibernation in the human left ventricle. Circulation. 1998;97:651–60. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.7.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YH, Xie F, Yashima M, Wu TJ, Valderrabano M, Lee MH, Ohara T, Voroshilovsky O, Doshi RN, Fishbein MC, Qu Z, Garfinkel A, Weiss JN, Karagueuzian HS, Chen PS. Role of papillary muscle in the generation and maintenance of reentry during ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation in isolated swine right ventricle. Circulation. 1999;100:1450–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.13.1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleber AG, Riegger CB. Electrical constants of arterially perfused rabbit papillary muscle. J Physiol. 1987;385:307–24. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleber AG, Rudy Y. Basic mechanisms of cardiac impulse propagation and associated arrhythmias. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:431–88. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00025.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleber AJ,MJ, Fast VG. The handbook of Physiology. The cardiovascular system. The Heart. Vol. 1. Am Pysiol Soc; Bethesda, MD: 2002. Normal and abnormal conduction in the heart; pp. 455–30. sect.2. [Google Scholar]

- Koura T, Hara M, Takeuchi S, Ota K, Okada Y, Miyoshi S, Watanabe A, Shiraiwa K, Mitamura H, Kodama I, Ogawa S. Anisotropic conduction properties in canine atria analyzed by high-resolution optical mapping: preferential direction of conduction block changes from longitudinal to transverse with increasing age. Circulation. 2002;105:2092–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000015506.36371.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucera JP, Rohr S, Rudy Y. Localization of sodium channels in intercalated disks modulates cardiac conduction. Circ Res. 2002;91:1176–82. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000046237.54156.0a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampe PD, Lau AF. Regulation of gap junctions by phosphorylation of connexins. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;384:205–15. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurita KR, Chuck ET, Yang T, Dong WQ, Kuryshev YA, Brittenham GM, Rosenbaum DS, Brown AM. Optical mapping reveals conduction slowing and impulse block in iron-overload cardiomyopathy. J Lab Clin Med. 2003;142:83–9. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2143(03)00060-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legrice IJ, Hunter PJ, Smaill BH. Laminar structure of the heart: a mathematical model. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:H2466–76. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.5.H2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeGrice IJ, Smaill BH, Chai LZ, Edgar SG, Gavin JB, Hunter PJ. Laminar structure of the heart: ventricular myocyte arrangement and connective tissue architecture in the dog. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:H571–82. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.2.H571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesh MD, Pring M, Spear JF. Cellular uncoupling can unmask dispersion of action potential duration in ventricular myocardium. A computer modeling study. Circ Res. 1989;65:1426–40. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.5.1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SF, Roth BJ, Wikswo JP., Jr. Quatrefoil reentry in myocardium: an optical imaging study of the induction mechanism. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 1999;10:574–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.1999.tb00715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Gemel J, Beyer EC, Veenstra RD. Dynamic model for ventricular junctional conductance during the cardiac action potential. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H1113–23. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00882.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier SK, Westenbroek RE, Schenkman KA, Feigl EO, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. An unexpected role for brain-type sodium channels in coupling of cell surface depolarization to contraction in the heart. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:4073–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261705699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno AP, Saez JC, Fishman GI, Spray DC. Human connexin43 gap junction channels. Regulation of unitary conductances by phosphorylation. Circ Res. 1994;74:1050–7. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.6.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohara T, Ohara K, Cao JM, Lee MH, Fishbein MC, Mandel WJ, Chen PS, Karagueuzian HS. Increased wave break during ventricular fibrillation in the epicardial border zone of hearts with healed myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2001;103:1465–72. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.10.1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osaka T, Kodama I, Tsuboi N, Toyama J, Yamada K. Effects of activation sequence and anisotropic cellular geometry on the repolarization phase of action potential of dog ventricular muscles. Circulation. 1987;76:226–36. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.76.1.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters NS, Coromilas J, Severs NJ, Wit AL. Disturbed connexin43 gap junction distribution correlates with the location of reentrant circuits in the epicardial border zone of healing canine infarcts that cause ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 1997;95:988–96. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.4.988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters NS, Green CR, Poole-Wilson PA, Severs NJ. Reduced content of connexin43 gap junctions in ventricular myocardium from hypertrophied and ischemic human hearts. Circulation. 1993;88:864–75. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.3.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters NS, Wit AL. Myocardial architecture and ventricular arrhythmogenesis. Circulation. 1998;97:1746–54. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.17.1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poelzing S, Rosenbaum DS. Altered connexin43 expression produces arrhythmia substrate in heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H1762–70. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00346.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Z, Kil J, Xie F, Garfinkel A, Weiss JN. Scroll wave dynamics in a three-dimensional cardiac tissue model: roles of restitution, thickness, and fiber rotation. Biophys J. 2000;78:2761–75. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76821-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan W, Rudy Y. Unidirectional block and reentry of cardiac excitation: a model study. Circ Res. 1990;66:367–82. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.2.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DE, Hersh LT, Scher AM. Influence of cardiac fiber orientation on wavefront voltage, conduction velocity, and tissue resistivity in the dog. Circ Res. 1979;44:701–12. doi: 10.1161/01.res.44.5.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohr SS,BM. Discontinuities in action potential propagation along chains of single ventricular myocytes in culture: Multiple site optical recording of transmembrane voltage (MSORTV) suggests propagation delays at the junctional sites between cells. Biol Bull. 1992;183:342–343. doi: 10.1086/BBLv183n2p342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudy Y. Electrotonic cell-cell interactions in cardiac tissue: effects on action potential propagation and repolarization. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1047:308–13. doi: 10.1196/annals.1341.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saffitz JE, Kanter HL, Green KG, Tolley TK, Beyer EC. Tissue-specific determinants of anisotropic conduction velocity in canine atrial and ventricular myocardium. Circ Res. 1994;74:1065–70. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.6.1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samie FH, Berenfeld O, Anumonwo J, Mironov SF, Udassi S, Beaumont J, Taffet S, Pertsov AM, Jalife J. Rectification of the background potassium current: a determinant of rotor dynamics in ventricular fibrillation. Circ Res. 2001;89:1216–23. doi: 10.1161/hh2401.100818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano T, Takayama N, Shimamoto T. Directional difference of conduction velocity in the cardiac ventricular syncytium studied by microelectrodes. Circ Res. 1959;7:262–7. doi: 10.1161/01.res.7.2.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schalij MJ, Boersma L, Huijberts M, Allessie MA. Anisotropic reentry in a perfused 2-dimensional layer of rabbit ventricular myocardium. Circulation. 2000;102:2650–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.21.2650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schalij MJ, Lammers WJ, Rensma PL, Allessie MA. Anisotropic conduction and reentry in perfused epicardium of rabbit left ventricle. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:H1466–78. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.5.H1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt FOS,OH. Partial excitation and variable conduction in the squid giant axon. J Physiol. 1940;98:26–46. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1940.sp003832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw RM, Rudy Y. Ionic mechanisms of propagation in cardiac tissue. Roles of the sodium and L-type calcium currents during reduced excitability and decreased gap junction coupling. Circ Res. 1997;81:727–41. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.5.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjostrand FS, Andersson-Cedergren E, Dewey MM. The ultrastructure of the intercalated discs of frog, mouse and guinea pig cardiac muscle. J Ultrastruct Res. 1958;1:271–87. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(58)80008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjostrand FS, Andersson E. Electron microscopy of the intercalated discs of cardiac muscle tissue. Experientia. 1954;10:369–70. doi: 10.1007/BF02160542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JH, Green CR, Peters NS, Rothery S, Severs NJ. Altered patterns of gap junction distribution in ischemic heart disease. An immunohistochemical study of human myocardium using laser scanning confocal microscopy. Am J Pathol. 1991;139:801–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spach MS, Dolber PC. Relating extracellular potentials and their derivatives to anisotropic propagation at a microscopic level in human cardiac muscle. Evidence for electrical uncoupling of side-to-side fiber connections with increasing age. Circ Res. 1986;58:356–71. doi: 10.1161/01.res.58.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spach MS, Dolber PC, Heidlage JF. Influence of the passive anisotropic properties on directional differences in propagation following modification of the sodium conductance in human atrial muscle. A model of reentry based on anisotropic discontinuous propagation. Circ Res. 1988;62:811–32. doi: 10.1161/01.res.62.4.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spach MS, Heidlage JF, Dolber PC, Barr RC. Electrophysiological effects of remodeling cardiac gap junctions and cell size: experimental and model studies of normal cardiac growth. Circ Res. 2000;86:302–11. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.3.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spach MS, Kootsey JM. Relating the sodium current and conductance to the shape of transmembrane and extracellular potentials by simulation: effects of propagation boundaries. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1985;32:743–55. doi: 10.1109/TBME.1985.325489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spach MS, Kootsey JM, Sloan JD. Active modulation of electrical coupling between cardiac cells of the dog. A mechanism for transient and steady state variations in conduction velocity. Circ Res. 1982a;51:347–62. doi: 10.1161/01.res.51.3.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]