Abstract

Objective

Sleep-disordered breathing describes a spectrum of upper airway obstruction in sleep from simple primary snoring, estimated to affect 10% of preschool children, to the syndrome of obstructive sleep apnea. Emerging evidence has challenged previous assumptions that primary snoring is benign. A recent report identified reduced attention and higher levels of social problems and anxiety/depressive symptoms in snoring children compared with controls. Uncertainty persists regarding clinical thresholds for medical or surgical intervention in sleep-disordered breathing, underlining the need to better understand the pathophysiology of this condition. Adults with sleep-disordered breathing have an increased risk of cerebrovascular disease independent of atherosclerotic risk factors. There has been little focus on cerebrovascular function in children with sleep-disordered breathing, although this would seem an important line of investigation, because studies have identified abnormalities of the systemic vasculature. Raised cerebral blood flow velocities on transcranial Doppler, compatible with raised blood flow and/or vascular narrowing, are associated with neuropsychological deficits in children with sickle cell disease, a condition in which sleep-disordered breathing is common. We hypothesized that there would be cerebral blood flow velocity differences in sleep-disordered breathing children without sickle cell disease that might contribute to the association with neuropsychological deficits.

Design

Thirty-one snoring children aged 3 to 7 years were recruited from adenotonsillectomy waiting lists, and 17 control children were identified through a local Sunday school or as siblings of cases. Children with craniofacial abnormalities, neuromuscular disorders, moderate or severe learning disabilities, chronic respiratory/cardiac conditions, or allergic rhinitis were excluded. Severity of sleep-disordered breathing in snoring children was categorized by attended polysomnography. Weight, height, and head circumference were measured in all of the children. BMI and occipitofrontal circumference z scores were computed. Resting systolic and diastolic blood pressure were obtained. Both sleep-disordered breathing children and the age- and BMI-similar controls were assessed using the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF), Neuropsychological Test Battery for Children (NEPSY) visual attention and visuomotor integration, and IQ assessment (Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence Version III). Transcranial Doppler was performed using a TL2-64b 2-MHz pulsed Doppler device between 2 PM and 7 PM in all of the patients and the majority of controls while awake. Time-averaged mean of the maximal cerebral blood flow velocities was measured in the left and right middle cerebral artery and the higher used for analysis.

Results

Twenty-one snoring children had an apnea/hypopnea index <5, consistent with mild sleep-disordered breathing below the conventional threshold for surgical intervention. Compared with 17 nonsnoring controls, these children had significantly raised middle cerebral artery blood flow velocities. There was no correlation between cerebral blood flow velocities and BMI or systolic or diastolic blood pressure indices. Exploratory analyses did not reveal any significant associations with apnea/hypopnea index, apnea index, hypopnea index, mean pulse oxygen saturation, lowest pulse oxygen saturation, accumulated time at pulse oxygen saturation <90%, or respiratory arousals when examined in separate bivariate correlations or in aggregate when entered simultaneously. Similarly, there was no significant association between cerebral blood flow velocities and parental estimation of child’s exposure to sleep-disordered breathing. However, it is important to note that whereas the sleep-disordered breathing group did not exhibit significant hypoxia at the time of study, it was unclear to what extent this may have been a feature of their sleep-disordered breathing in the past. IQ measures were in the average range and comparable between groups. Measures of processing speed and visual attention were significantly lower in sleep-disordered breathing children compared with controls, although within the average range. There were similar group differences in parental-reported executive function behavior. Although there were no direct correlations, adjusting for cerebral blood flow velocities eliminated significant group differences between processing speed and visual attention and decreased the significance of differences in Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function scores, suggesting that cerebral hemodynamic factors contribute to the relationship between mild sleep-disordered breathing and these outcome measures.

Conclusions

Cerebral blood flow velocities measured by noninvasive transcranial Doppler provide evidence for increased cerebral blood flow and/or vascular narrowing in childhood sleep-disordered breathing; the relationship with neuropsychological deficits requires further exploration. A number of physiologic changes might alter cerebral blood flow and/or vessel diameter and, therefore, affect cerebral blood flow velocities. We were able to explore potential confounding influences of obesity and hypertension, neither of which explained our findings. Second, although cerebral blood flow velocities increase with increasing partial pressure of carbon dioxide and hypoxia, it is unlikely that the observed differences could be accounted for by arterial blood gas tensions, because all of the children in the study were healthy, with no cardiorespiratory disease, other than sleep-disordered breathing in the snoring group. Although arterial partial pressure of oxygen and partial pressure of carbon dioxide were not monitored during cerebral blood flow velocity measurement, assessment was undertaken during the afternoon/early evening when the child was awake, and all of the sleep-disordered breathing children had normal resting oxyhemoglobin saturation at the outset of their subsequent sleep studies that day. Finally, there is an inverse linear relationship between cerebral blood flow and hematocrit in adults, and it is known that iron-deficient erythropoiesis is associated with chronic infection, such as recurrent tonsillitis, a clinical feature of many of the snoring children in the study. Preoperative full blood counts were not performed routinely in these children, and, therefore, it was not possible to exclude anemia as a cause of increased cerebral blood flow velocity in the sleep-disordered breathing group. However, hemoglobin levels were obtained in 4 children, 2 of whom had borderline low levels (10.9 and 10.2 g/dL). Although there was no apparent relationship with cerebral blood flow velocity in these children (cerebral blood flow velocity values of 131 and 130 cm/second compared with 130 and 137 cm/second in the 2 children with normal hemoglobin levels), this requires verification. It is of particular interest that our data suggest a relationship among snoring, increased cerebral blood flow velocities and indices of cognition (processing speed and visual attention) and perhaps behavioral (Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function) function. This finding is preliminary: a causal relationship is not established, and the physiologic mechanisms underlying such a relationship are not clear. Prospective studies that quantify cumulative exposure to the physiologic consequences of sleep-disordered breathing, such as hypoxia, would be informative.

Keywords: sleep disordered breathing, cerebral blood flow, transcranial Doppler, executive function, neuropsychological function

SLEEP-DISORDERED BREATHING (SDB) encompasses a spectrum of upper airway obstruction in sleep from simple primary snoring, through the upper airways resistance syndrome, to obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Primary snoring is estimated to affect on average 10% of preschool children1-3 at a time when adenotonsillar size is maximal relative to the airway.4 Emerging evidence has challenged previous assumptions that primary snoring is benign. A recent report identified reduced attention and higher levels of social problems and anxiety/depressive symptoms in snoring children compared with controls.5 Furthermore, a population-based survey identified that habitual snoring was associated with hyperactive and inattentive behavior independent of measures of nocturnal hypoxia.6 Uncertainty persists regarding clinical thresholds for medical or surgical intervention in SDB,7 underlining the need to better understand the pathophysiology of this condition.

The causative pathway from SDB to neurocognitive dysfunction in children is poorly understood. Beebe and Gozal8 proposed a model of prefrontal cortical dysfunction resulting from the intermittent hypoxia and sleep fragmentation characteristic of OSA and recommended study of executive function domains in future pediatric research. There is emerging evidence for an executive function deficit in children with SDB.9,10 Systematic review11 and a recent population study12 have supported the hypothesis that intermittent hypoxia may be an important mediator of neurocognitive deficits. The lack of consistent strong correlations between polysomnographic variables and measurable neurocognitive outcomes in studies of childhood SDB9,13 suggests a complex relationship between clinically measurable pathophysiological processes and behavioral abnormality. One possibility is that there are structural and functional adaptations in the brain and its vasculature that obscure any direct effect of exposure to hypoxia or arousals but eventually have deleterious effects.

The association between OSA and stroke risk14 in adults has prompted researchers to look for evidence of cerebrovascular disease. Ultrasonography has revealed increased carotid intima-media thickness in adults with OSA.15 Transcranial Doppler (TCD) cerebral blood flow velocity (CBFV)16 measurement in the intracranial arteries17 has demonstrated significant sleep apnea-related fluctuations in CBFV in adult OSA,18 as well as reduced daytime cerebrovascular reactivity to hypercapnia.19

There has been little focus on cerebrovascular function in children with SDB, partly reflecting the need for sedation in neuroimaging of young children and the ethical constraints on using these techniques in research. However, this would seem an important line of investigation, because studies have identified abnormalities of the systemic vasculature.20-22 Amin et al23 demonstrated that increased mean blood pressure variability in children correlated with polysomnographic indices of SDB severity. Increased systemic blood pressure variability in adult populations is associated with cerebrovascular disease and brain atrophy in adults.24 There are advantages to studying cardiovascular morbidity in children who lack the comorbid atherogenic disease that complicates adult clinical research.25 Furthermore, increased CBFV has been associated with deficits on measures of intelligence26,27 and attention28 in children with sickle cell disease, a condition associated with chronic hypoxemia in childhood, suggesting that it is a marker for vulnerable brain tissue with reduced function.

We aimed to determine whether CBFV differed between children with mild SDB, below the conventional threshold for surgical intervention, and age and socioeconomically similar controls. Secondary aims were twofold: (1) to explore a possible relationship between polysomnographic indices of SDB (eg, apnea/hypopnea index and pulse oxygen saturation [Spo2]) and CBFV and (2) to explore the extent to which CBFV is associated with SDB and neuropsychological/behavioral scores.

METHODS

Ethical approval was obtained from the Southampton and South West Hampshire Research Ethics Committee. Written parental consent and child assent was obtained for all of the participants.

Participants

A total of 34 children, aged 3 to 7 years, with a history of snoring were recruited from adenotonsillectomy waiting lists. Two families subsequently declined the invitation to participate. One child was excluded after initial interview because of a significant history of asthma. Polysomnography was tolerated in 30 of 31 of the remaining snoring children, and 21 (9 boys) were defined as “mild” SDB based on an apnea-hypopnea index of ≤5 per hour of total sleep time.29 Seventeen control children (9 boys) were identified through a local Sunday school or as siblings of cases, selected for inclusion because of similarity in age. These children lived in the mixed urban and rural districts of Southampton and Portsmouth, United Kingdom, and all of the parents had completed secondary school education. Children with craniofacial abnormalities, neuromuscular disorders, moderate or severe learning disabilities, chronic respiratory/cardiac conditions, or allergic rhinitis were excluded. The characteristics of these study groups are described in Table 1. All of the children were participating in a prospective study investigating neurocognitive function in SDB.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the Study Groups: Age, Blood Pressure, and Anthropometric Indices

| Variable | Controls (N = 17) | SDB (N = 21) | Group Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 5.1 (1.3) | 5.5 (1.4) | NS |

| Systolic blood pressure index in wake | -12.8 (6.9) | -10.0 (6.7) | NS |

| Diastolic blood pressure index in wake | -13.1 (10.9) | -14.1 (7.6) | NS |

| Head circumference; z score | -0.4 (0.7) | -0.7 (1.3) | NS |

| Height, cm; centile | 60.8 (26.2) | 60.9 (27.0) | NS |

| BMI, kg/m2; z score | 0.1 (1.4) | -0.3 (1.0) | NS |

Values are mean (SD). NS indicates not significant.

Classification of SDB

All of the snoring children underwent 1 night of attended polysomnography. Because of limited resources, it was not possible to undertake polysomnography in control children; however, parents of both snoring children and nonsnoring controls completed the Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire (PSQ), a 22-item screening questionnaire, which documents the presence or absence of symptoms, such as loud snoring at night, observed apnea, and morning headache. The PSQ has been reported to have a sensitivity of between 0.81 and 0.85 in detecting SDB compared with a polysomnographic diagnosis.30 Polysomnography was conducted in a purpose-built sleep laboratory using computerised systems (Embla system/Somnologica studio software, Medcare Flaga, Reykjavik, Iceland) according to American Thoracic Society standards.31 A standard montage was recorded including electroencephalogram (C3/A2, O1/A2, C4/A1, and O2/A1), right and left electro-oculogram, bipolar submental electromyogram, diaphragmatic electromyogram, thoracic and abdominal excursions detected by respiratory inductance plethysmography (Xact-trace, Medcare Flaga), nasal airflow (Protech, Mukilteo, WA), finger pulse oximetry (Nonin, Plymouth, MN), electrocardiogram, and synchronous video recording. Sleep staging was scored using standard criteria.32 Respiratory arousals were defined as changes in electroencephalogram frequency of ≥1 second after an apnea or hypopnea.33 Obstructive apnea was defined as the presence of chest/abdominal wall movement in the absence or decrease of airflow by >80% of the preceding breath for ≥2 breaths. Hypopneas were classified as for apneas but where the reduction in flow was 50%-80% of the previous breath. Oxygen desaturation was classified by a 3% or more decrease in Spo2 from the baseline. The apnea/hypopnea index was defined as the number of obstructive apneas, hypopneas, and mixed apneas per hour of total sleep time. Central apneas could be confidently identified from the respiratory inductance plethysmography bands and were separately scored. There is currently no consensus for respiratory scoring criteria in children.34 These criteria were selected to discriminate obstructive respiratory events in sleep. Studies were independently scored by an experienced sleep technician (S.C.) and a pediatrician (C.M.H).

In addition to polysomnography, which is a single time point measure of SDB severity, the duration of exposure to SDB was estimated based on parental report, recorded as the number of years that the child had snored multiplied by the mean days per week of snoring during the previous year. Parents were asked 2 questions: (1) “How many years has your child snored?” and (2) “During the past year, on average how many days per week has your child snored?” There are no validated measures of snoring exposure in children, although previous studies have addressed this issue indirectly by asking how often the child snores35 or if the child snored between the ages of 2 and 6 years.36

Blood Pressure and Anthropometric Measures

Children were weighed, and height and occipitofrontal circumference were measured. BMI and occipitofrontal circumference z scores were computed. Resting systolic and diastolic blood pressure were obtained using Dinamp technology (Dash 3000 GE Health care). To control for influence of age and height on blood pressure,37 a blood pressure index was computed as described by Amin et al.23

where BP is blood pressure. Blood pressure centiles were derived from standard published values.37

TCD

TCD was performed using a TL2-64b 2-MHz pulsed Doppler device between 2 PM and 7 PM in all of the patients and in the majority of controls. The operator (N.O.) was blinded to the neuropsychological, behavioral, and SDB status of the child but was aware of their patient/control status. The child remained awake but was encouraged to lie quietly. Time-averaged mean of the maximal CBFV of the left and right middle cerebral artery (henceforth simply referred to as CBFV) was measured through the temporal ultrasound “acoustic window” above the zygomatic arch and anterior to the ear. All of the studies started at a depth of 45 mm, and identification of the maximum velocity envelope in the terminal internal cerebral artery/middle cerebral artery was confirmed by following the vessel to a shallow depth of 35 to 40 mm and a deeper depth of 50 to 55 mm, the middle cerebral artery/anterior cerebral artery bifurcation. CBFV was recorded bilaterally for the middle cerebral artery,38 responsible for ≥80% of cerebral blood flow. Attempts to additionally insonate the anterior cerebral artery and basilar arteries were rarely tolerated by these young children. For 5 cases (2 controls), similar CBFV recordings were obtained by one of the principal investigators (A.M.H.) immediately after the first recording (r = 0.996; P < .001).

Neuropsychology

Children were assessed using the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (WPPSI-III), yielding measures of verbal IQ (VIQ), performance IQ (PIQ), and full-scale IQ (FSIQ), each with a mean in the general population of 100 and a SD of 15. A processing speed quotient was obtained only in children aged ≥4 years (17 mild SDB, 14 controls) in line with the WPPSI-III protocol. Two subtests from the Neuropsychological Test Battery for Children (NEPSY) were also administered: visual attention (mean score: 10; range: 1-19) and design copying (raw scores are reported: maximum score: 72).

Parental Ratings of Executive Function Behavior

All of the parents completed the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) for children aged 6-7 years or BRIEF-Preschool for children aged 3-5 years.39 For each behavioral domain, parents rated their child’s behavior on a 3-point scale (never, sometimes, and often). This provided an indication of the child’s behavior across various domains of executive function: “inhibition,” “working memory,” “emotional control,” “shift,” and “plan/organize” and an overall score, the global executive composite, with clinically significant T scores being in excess of 65.

Statistical Analysis

A complete data set was obtained in the majority of mild SDB children (16 of 21) and in all 17 controls. The oximetry probe was not tolerated by 2 children during their sleep study, and blood pressure was not recorded in 5 SDB children. Failure to obtain a complete data set was also because of failure to obtain bilateral TCD readings (3 SDB cases). One SDB child was reluctant to complete the NEPSY tasks. In addition, the BRIEF was not returned by the parents of 1 SDB child who asked to complete this questionnaire at home.

Demographic, anthropometric, polysomnographic, and CBFV group differences were examined using independent sample t tests or the nonparametric equivalent (Mann-Whitney) if data were not normally distributed. Neuropsychological and behavioral indices were similarly examined. Using bivariate correlations and regression analysis, we explored the association between CBFV and polysomnographic variables. In a preliminary attempt to explore the extent to which CBFV, as an index of cerebral hemodynamics, contributes to the relationship between SDB and neuropsychological and behavioral indices, we also performed analysis of covariance. If the significance of any group difference is reduced with the addition of CBFV as a covariate, we may conclude that CBFV may contribute to the relationship between SDB and cognitive/behavioral performance.

RESULTS

As indicated in Table 1, mean age, head circumference, height, and BMI did not significantly differ between groups: the children did not represent an obese population. Presence of snoring history was confirmed by scores obtained from the PSQ, which showed that the mild SDB group had a mean score of 0.5 (SD: 0.1), where >0.33 is considered to be abnormal (R. D. Chervin, MD, MS, written communication, 2005). None of the controls scored within the abnormal range (group mean: 0.1; SD: 0.1; t36 = 10.4; P < .001), further validating their allocation to a nonsnoring group.

Polysomnography

Polysomnography in the snoring children demonstrated that all of the children had some episodes of upper airway obstruction during sleep. The majority of these episodes were hypopneas. Mean oxygen levels were in the reference range for all of the children, although some children experienced episodic desaturations associated with obstructive events (Table 2). The duration of parental estimated exposure of snoring for those with SDB was 18.8 (SD: 8.0).

TABLE 2.

Polysomnography Variables for Children With Mild SDB

| Variable | Median | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Mean O2 saturation | 96.7 | 94.0-98.1 |

| Time O2 <90%, min | 0 | 0.0-1.4 |

| Apnea/hypopnea index | 2.0 | 0.4-4.8 |

| Respiratory arousal index | 0.6 | 0.0-6.8 |

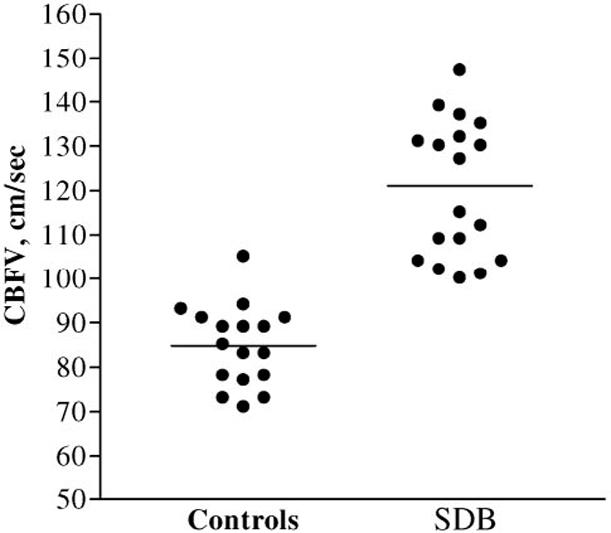

Time-Averaged Mean of the Maximum Blood Flow Velocities in the Middle Cerebral Artery

TCD recordings from ≥1 side were obtained in 18 of 21 and 17 of 17 of the mild SDB and control groups, respectively. As illustrated in Fig 1, CBFV was significantly increased in the mild SDB group compared with controls (t27.7 = 8.3; P < .001). Posthoc analyses addressed the possibility that systemic hypertension might account for the group differences in CBFV. However, the majority of children were normotensive according to age-, gender-, and height-adjusted values: systolic blood pressure index was raised in 1 SDB child (7.8) and diastolic in 1 control child (1.4). There was no significant correlation between blood pressure indices and CBFV, and the inclusion of this covariate did not alter the significant CBFV group difference (P < .001).

FIGURE 1.

Individual time-averaged mean maximum CBFV scores for controls and children with sleep-disordered breathing. The horizontal bar represents the mean score.

We were interested to know whether the variance in CBFV might be explained by specific polysomnographic variables. Exploratory analyses did not reveal any significant associations with apnea/hypopnea index, apnea index, hypopnea index, mean Spo2, lowest Spo2, accumulated time at Spo2 <90%, or respiratory arousals when examined in separate bivariate correlations or in aggregate when entered simultaneously (linear regression: R2 = 0.401; F7,15 = .8; P = .632). Similarly, there was no significant association between CBFV and parental estimation of their child’s exposure to SDB.

Neuropsychology

As shown in Table 3, the level of general intellectual function did not significantly differ between groups; the majority of children obtained scores that were in the high average range. Similarly, design copying was compatible across groups. The processing speed quotient was significantly reduced in the mild SDB group. Visual attention scores obtained using NEPSY were also lower in mild SDB children compared with controls. Although there were no direct correlations between either of these measures and CBFV when the mild SDB group was examined separately (both P > .1), the significant group differences did not remain when CBFV was entered as a covariate (analysis of covariance). This indicates that a proportion of the variance in processing speed and visual attention scores may be explained by factors associated with increased CBFV.

TABLE 3.

Neuropsychology: Mean IQ and Processing Speed Index (WPPSI-III), Visual Attention and Design Copying (NEPSY) Scores

| Variable | Controls, Mean (SD) | SDB, Mean (SD) | Group Difference (P) | P Adjusted for CBFV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VIQ | 112.5 (10.8) | 110.2 (13.7) | NS | |

| PIQ | 104.4 (9.8) | 105.1 (13.2) | NS | |

| FSIQ | 110.3 (8.0) | 108.3 (13.0) | NS | |

| Processing speed quotient | 106.1 (11.7) | 95.8 (14.9) | t29 = -2.1 (.044) | .265 |

| Visual attention (scaled score) | 12.5 (3.2) | 10.5 (2.4) | t35 = -2.1 (.037) | .304 |

| Design copying (raw score) | 33.7 (16.6) | 32.0 (13.3) | NS |

Significant group differences for measures of visual attention and processing speed were reduced with the inclusion of CBFV as a covariate, indicating that factors associated with this variable may contribute to the relationship between SDB and cognitive deficit. NS indicates not significant.

Parental Ratings of Executive Function Behavior

All of the executive function behaviors assessed by the BRIEF were significantly worse in mild SDB children compared with controls (see Table 4). As before, there were no direct correlations between BRIEF subscales or total score and CBFV in the mild SDB group (P > .1). For the majority of indices, analysis of covariance tests revealed a residual difference between groups when controlling for CBFV, although the significance of this difference slightly decreased suggesting that there may be some partial association between CBFV and parental report of executive function behaviors.

TABLE 4.

Executive Function Behavior: Mean Executive Function Behavior t Scores

| Variable | Controls, Mean (SD) | SDB, Mean (SD) | Group Difference (P) | P Adjusted for CBFV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibit | 47.8 (9.1) | 58.3 (10.8) | t35 = 3.1 (.003) | .015 |

| Shift | 46.5 (7.4) | 53.6 (11.6) | t32.6 = 2.2 (.032) | .089 |

| Emotional control | 44.2 (6.9) | 58.7 (11.8) | t31.3 = 4.6 (.001) | .005 |

| Working memory | 47.2 (11.0) | 62.4 (14.8) | t35 = 3.5 (.001) | .007 |

| Plan/organize | 46.1 (9.1) | 61.4 (13.5) | t35 = 3.9 (.001) | .002 |

| Global executive composite | 45.4 (8.2) | 61.4 (13.2) | t35 = 4.3 (.001) | .001 |

Clinical significance on this measure >65. Significant group differences were found for all indices, the majority of which remained significant when CBFV was added as a covariate. This suggests that this variable only minimally influenced the relationship between SDB and cognitive deficit; although see “Shift,” which no longer showed a statistically significant group difference.

DISCUSSION

The finding of significant differences between otherwise healthy children with mild SDB and controls on neuropsychological and behavioral measures of executive function replicates the findings of previous studies.9,10 We also provide novel preliminary evidence of abnormal cerebral hemodynamics in a nonobese population of young children with mild SDB of a severity below the conventional treatment threshold. The fact that adjusting for CBFV reduces group differences in neuropsychological measures suggests that factors associated with cerebral hemodynamics may contribute to the relationship between SDB and neuropsychological impairment.

Children with a history of snoring obtained a mean value for CBFV (120 cm/second) that was intermediate between that obtained from healthy controls (84 cm/second) and the threshold for moderate stroke risk in children with sickle cell disease (>170 cm/second).40 Even African children, with a high prevalence of anemia secondary to iron deficiency and sickle trait, have mean CBFV values of 92 cm/second (+2 SDs = 142 cm/second)41; in comparison, 1 of the SDB children in the current series had a CBFV of 147 cm/second. The CBFV values for control children are very similar to those published previously in healthy children of similar age42 and before sleep in 5 children aged 5 to 13 years.43 There were no previous studies of CBFV in SDB children on which to base a power calculation, but in this sample of 21 with mild SDB, in 18 of whom we managed to obtain a TCD study, and 17 controls, the effect of snoring was large (d = 2.79). Raised CBFV is likely to be attributable either to increased cerebral blood flow or narrowing of the cerebral vessels or a combination of these factors. A number of physiologic changes might alter cerebral blood flow and/or vessel diameter and, therefore, affect CBFV. We were able to study several potential confounding influences on CBF. First, there were no differences in systolic and diastolic blood pressure indices between SDB children and controls. Second, although CBFV increases with increasing partial pressure of carbon dioxide44,45 and hypoxia,46 it is unlikely that observed differences could be accounted for by arterial blood gas tensions, because all of the children in the study were healthy with no cardiorespiratory disease, other than SDB in the snoring group. Although arterial partial pressure of oxygen and partial pressure of carbon dioxide were not monitored during CBFV measurement, assessment was undertaken during the afternoon/early evening when the child was awake, and all of the SDB children had normal resting oxyhemoglobin saturation at the outset of their subsequent sleep studies that day.

Finally, there is an inverse linear relationship between CBF and hematocrit in adults,47 and it is known that iron-deficient erythropoiesis is associated with chronic infection, such as recurrent tonsillitis, a clinical feature of many of the snoring children in the study.48 Increased CBFV might reflect increased CBF as an adaptation to anemia and reduced arterial oxygen content. Blood tests were not routinely performed on these children. However, a hemoglobin measure was obtained from 4 children immediately preoperatively and within 6 months of the TCD study after advice to the otolaryngologist that the child’s CBFV was raised. Normal hemoglobin levels (lower reference limits: 11.1g/dL at <5 years and 11.5 g/dL at 5-8 years) were found in 2 children with CBFV measures of 130 and 137 cm/second, respectively. Borderline low hemoglobin levels in 2 children (case 1 [3 years]: 10.9 g/dL; and case 2 [6 years]: 10.2 g/dL) were associated with CBFV values, respectively, of 131 and 130 cm/second.

Thus, there was no apparent relation between hemoglobin concentration and CBFV within the ethical constraints limiting blood tests to only a proportion of symptomatic children undergoing adenotonsillectomy. It will be important to explore the association between iron-deficient erythropoiesis and CBFV in future studies, because chronic anemia could, in part, explain both the observed neurocognitive deficits49-51 and increased CBFV in children with SDB.

Our data suggest a relationship between snoring, increased CBFV, and indices of cognitive (visual attention and processing speed), and perhaps behavioral (BRIEF) function, but this finding is preliminary and requires replication; a causal relationship is not established, and the physiologic mechanisms underlying such a relationship are not clear. However, evidence obtained from young children with sickle cell disease suggests that increased CBFV may represent generalized increased CBF, as an adaptation to chronic-intermittent hypoxemia, or cerebrovascular disease.52 It is important to note that whereas the SDB group did not exhibit significant hypoxia at the time of study, it was unclear to what extent this may have been a feature of their SDB in the past.

Despite the specific cognitive and behavioral deficits observed, there was no apparent impact on more general intellectual function (VIQ, PIQ, and FSIQ) or visuomotor integration, perhaps because of the young age of these children in whom intellectual function is still emerging. This finding is consistent with previous studies showing that intellectual deficit may not be expected in children with SDB53,54; however, it is possible that intellectual and cognitive deficit may become increasingly apparent with age and academic progression.36 The results of repeat measures in these children after adenotonsillectomy and longitudinal studies extending into adolescence will be of interest.

In this study, we found that as-yet unconfirmed factors associated with cerebral hemodynamic derangement may explain a proportion of the variance in visual attention and processing speed functions, both skills that are already known to be vulnerable to chronic-intermittent hypoxia associated with SDB in adults55 and with chronic hypoxia associated with cardiac abnormalities in children.56 Prospective studies that quantify cumulative exposure to the physiologic consequences of SDB, such as hypoxia, would be informative.

CONCLUSIONS

Noninvasive transcranial Doppler measurement of CBFV may provide an important marker of brain vulnerability in children with SDB. The relevance of these findings to clinical practice requires additional study. It will be important to establish whether increased CBFV is a transient adaptive response to SDB or is indicative of a permanent alteration of cerebral hemodynamics with implications for future health. Additional studies in larger samples may clarify whether correlations can be demonstrated with measurable alternations in the systemic vasculature, as well as with polysomnographic indices of hypoxia and sleep arousals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by grants to Dr Hogan (HOPE Innovation Award), Dr Hill (Research Management Committee, Southampton University School of Medicine), and Drs Kirkham and Datta (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health [5-R01-HL079937] and the Stroke Association [PROG4]).

Polysomnography studies were conducted at the Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility, Southampton University Hospital Trust, and we gratefully acknowledge the assistance of management and nursing staff and, additionally, Dr Tony Birch (Medical Physics) for his advice with regard to the transcranial Doppler studies. We extend our gratitude to Prof Jim Stevenson, who advised on both the development of the study and the statistical analysis. Patients were recruited from Portsmouth hospitals and Southampton University Hospital National Health Service Trust, which receive a proportion of their funding from the National Health Service Executive. We are indebted to Drs Simon Dennis and Kate Heathcote for their assistance in recruitment.

Abbreviations

- SDB

sleep-disordered breathing

- OSA

obstructive sleep apnea

- TCD

transcranial Doppler

- CBFV

cerebral blood flow velocity

- PSQ

pediatric sleep questionnaire

- WPPSI-111

Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence Version III

- VIQ

visual IQ

- PIQ

performance IQ

- FSIQ

full-scale IQ

- NEPSY

Neuropsychological Test Battery for Children

- BRIEF

Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function

- Spo2

pulse oxygen saturation

Footnotes

Drs Hill and Hogan contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kaditis AG, Finder J, Alexopoulos EI, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing in 3,680 Greek children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2004;37:499–509. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sogut A, Altin R, Uzun L, et al. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and associated symptoms in 3-11-year-old Turkish children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005;39:251–256. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castronovo V, Zucconi M, Nosetti L, et al. Prevalence of habitual snoring and sleep-disordered breathing in pre-school aged children in an Italian community. J Pediatr. 2003;142:364–365. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2003.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marcus CL. Sleep-disordered breathing in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:16–30. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.1.2008171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Brien LM, Mervis CB, Holbrook CR, et al. Neurobehavioral implications of habitual snoring in children. Pediatrics. 2004;114:44–49. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Urschitz MS, Eitner S, Guenther A, et al. Habitual snoring, intermittent hypoxia, and impaired behavior in primary school children. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1041–1048. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-1145-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Thoracic Society Cardiorespiratory sleep studies in children: establishment of normative data and polysomnographic predictors of morbidity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:1381–1387. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.4.16041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beebe DW, Gozal D. Obstructive sleep apnea and the prefrontal cortex: towards a comprehensive model linking nocturnal upper airways obstruction to daytime cognitive and behavioral deficits. J Sleep Res. 2002;11:1–16. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2002.00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beebe DW, Wells CT, Jeffries J, et al. Neuropsychological effects of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;10:962–975. doi: 10.1017/s135561770410708x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gottlieb DJ, Chase C, Vezina RM, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing symptoms are associated with poorer cognitive function in 5-year-old children. J Pediatr. 2004;145:458–464. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bass JL, Corwin M, Gozal D, et al. The effect of chronic or intermittent hypoxia on cognition in childhood: a review of the evidence. Pediatrics. 2004;114:805–816. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Urschitz MS, Wolff J, Sokollik C, et al. Nocturnal arterial oxygen saturation and academic performance in a community sample of children. Pediatrics. 2005;115(2) doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1256. Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/115/2/e204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaemingk KL, Pasvogel AE, Goodwin JL, et al. Learning in children and sleep disordered breathing: findings of the Tucson Children’s Assessment of Sleep Apnea (tuCASA) prospective cohort study. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2003;9:1016–1026. doi: 10.1017/S1355617703970056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yaggi H, Mohsenin V. Obstructive sleep apnea and stroke. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:333–342. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(04)00766-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Minoguchi K, Yokoe T, Tazaki T, et al. Increased carotid intima-media thickness and serum inflammatory markers in obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:625–630. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200412-1652OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nichols FT, Jones AM, Adams RJ. Stroke prevention in sickle cell disease (STOP) study guidelines for transcranial Doppler testing. J Neuroimaging. 2001;11:354–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6569.2001.tb00063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aaslid R, Markwalder TM, Nornes H. Noninvasive transcranial Doppler ultrasound recording of flow velocity in basal cerebral arteries. J Neurosurg. 1982;57:769–774. doi: 10.3171/jns.1982.57.6.0769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hajak G, Klingelhofer J, Schulz-Varszegi M, Sander D, Ruther E. Sleep apnea syndrome and cerebral hemodynamics. Chest. 1996;110:670–679. doi: 10.1378/chest.110.3.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Placidi F, Diomedi M, Cupini LM, Bernardi G, Silvestrini M. Impairment of daytime cerebrovascular reactivity in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. J Sleep Res. 1998;7:288–292. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1998.00120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kwok KL, Ng DK, Cheung YF. BP and arterial distensibility in children with primary snoring. Chest. 2003;123:1561–1566. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.5.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kohyama J, Ohinata JS, Hasegawa T. Blood pressure in sleep disordered breathing. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:139–142. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.2.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marcus CL, Greene MG, Carroll JL. Blood pressure in children with obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1098–1103. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.4.9704080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amin RS, Carroll JL, Jeffries JL, et al. Twenty-four-hour ambulatory blood pressure in children with sleep-disordered breathing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:950–956. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200309-1305OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Havlik RJ, Foley DJ, Sayer B, Masaki K, White L, Launer LJ. Variability in midlife systolic blood pressure is related to latelife brain white matter lesions: the Honolulu-Asia Aging study. Stroke. 2002;33:26–30. doi: 10.1161/hs0102.101890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quan SF, Gersh BJ. National Center on Sleep Disorders Research; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Cardiovascular consequences of sleep-disordered breathing: past, present and future: report of a workshop from the National Center on Sleep Disorders Research and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Circulation. 2004;109:951–957. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000118216.84358.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bernaudin F, Verlac S, Fréard F, et al. Multicenter prospective study of children with sickle cell disease: radiographic and psychometric correlation. J Child Neurol. 2000;15:333–343. doi: 10.1177/088307380001500510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kral MC, Brown RT, Nietert PJ, Abboud MR, Jackson SM, Hynd GW. Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography and neurocognitive functioning in children with sickle cell disease. Pediatrics. 2003;112:324–321. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kral MC, Brown RT. Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography and executive dysfunction in children with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Psychol. 2004;29:185–195. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsh020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marcus CL, Omlin KJ, Basinki DJ, et al. Normal polysomno-graphic values for children and adolescents. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146:1235–1239. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.5_Pt_1.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chervin RD, Hedger K, Dillon JE, Pituch KJ. Pediatric Sleep Questionnaire (PSQ): validity and reliability of scales for sleep disordered breathing, snoring, sleepiness and behavioral problems. Sleep Medicine (Baltimore) 2000;1:21–32. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(99)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.American Thoracic Society Standards and indications for cardiopulmonary sleep studies in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;153:866–878. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.2.8564147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rechtschaffen A, Kales A. A Manual of Standardized Terminology: Techniques and Scoring System for Sleep Stages of Human Subjects. UCLA Brain Information Service, Brain Research Institute; Los Angeles, CA: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mograss MA, Ducharme FM, Brouillette RT. Movement/arousals. Description, classification, and relationship to sleep apnea in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:1690–1696. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.6.7952634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang JPL, Rosen CL, Larkin MHS, et al. Identification of sleep-disordered breathing in children: variation with event definition. Sleep. 2002;25:72–79. doi: 10.1093/sleep/25.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gozal D. Sleep-disordered breathing and school performance in children. Pediatrics. 1998;102:616–620. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.3.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gozal D, Pope DW., Jr. Snoring during early childhood and academic performance at ages thirteen to fourteen years. Pediatrics. 2001;107:1394–1399. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosner B, Prineas RJ, Loggie JM, Daniels SR. Blood pressure nomograms for children and adolescents, by height, sex, and age, in the United States. J Pediatr. 1993;123:871–886. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80382-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bode H, Wais U. Age dependence of flow velocities in basal cerebral arteries. Arch Dis Child. 1988;63:606–611. doi: 10.1136/adc.63.6.606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gioia GA, Isquith PK, Guy SC, Kenworthy L. BRIEF: Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sloan MA, Alexandrov AV, Tegeler CH, et al. Assessment: transcranial Doppler ultrasonography report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2004;62:1468–1481. doi: 10.1212/wnl.62.9.1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Newton CR, Marsh K, Peshu N, Kirkham FJ. Perturbations of cerebral hemodynamics in Kenyans with cerebral malaria. Pediatr Neurol. 1996;15:41–49. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(96)00115-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brouwers PJ, Vriens EM, Musbach M, Wieneke GH, van Huffelen AC. Transcranial pulsed Doppler measurements of blood flow velocity in the middle cerebral artery: reference values at rest and during hyperventilation in healthy children and adolescents in relation to age and sex. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1990;16:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(90)90079-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fischer AQ, Taormina MA, Akhtar B, Chaudhary BA. The effect of sleep on intracranial hemodynamics: a transcranial Doppler study. J Child Neurol. 1991;6:155–158. doi: 10.1177/088307389100600212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kirkham FJ, Padayachee TS, Parsons S, Seargeant LS, House FR, Gosling RG. Transcranial measurement of blood velocities in the basal cerebral arteries using pulsed Doppler ultrasound: velocity as an index of flow. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1986;12:15–21. doi: 10.1016/0301-5629(86)90139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peters P, Datta AK. Middle cerebral artery blood flow velocity studied during quiet breathing, reflex hypercapnic breathing and volitionally copied eucapnic breathing in man. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;393:293–296. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1933-1_55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lassen NA, Christensen MS. Physiology of cerebral blood flow. Br J Anaesth. 1976;48:719–734. doi: 10.1093/bja/48.8.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jones MD, Jr, Hudak ML, Traystman RJ. Cerebral blood flow and haematocrit. Lancet. 1985;1(8444):1511. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)92290-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elverland HH, Aasand G, Miljeteig H, Ulvik RJ. Effects of tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy on hemoglobin and iron metabolism. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2004;68:419–423. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2003.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pollitt E, Read MS. Bridges between nutrition, neuroscience and behavior. Am J Clin Nutr. 1985;42:348–351. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/42.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pollitt E. Iron deficiency and cognitive function. Ann Rev Nutr. 1993;13:521–537. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.13.070193.002513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Otero GA, Aguirre DM, Porcayo R, Fernandez T. Psychological and electroencephalographic study in school children with iron deficiency. Int J Neurosci. 1999;99:113–121. doi: 10.3109/00207459908994318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hogan AM, Kirkham FJ, Prengler M, et al. An exploratory study of physiological correlates of neurodevelopmental delay in infants with sickle cell anaemia. Br J Haematol. 2005;132:99–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rhodes SK, Shimoda KC, Waid LR, et al. Neurocognitive deficits in morbidly obese children with obstructive sleep apnea. J Pediatr. 1995;127:741–744. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(95)70164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kennedy JD, Blunden S, Hirte C, et al. Reduced neurocognition in children who snore. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2004;37:330–337. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Naismith S, Winter V, Gotsopoulos H, Hickie I, Cistulli P. Neurobehavioral functioning in obstructive sleep apnoea: differential effects of sleep quality, hypoxemia and subjective sleepiness. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2004;26:43–54. doi: 10.1076/jcen.26.1.43.23929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.O’Dougherty M, Wright FS, Loewenson RB, Torres F. Cerebral dysfunction after chronic hypoxia in children. Neurology. 1985;35:42–46. doi: 10.1212/wnl.35.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]