Abstract

Mechanical forces have been shown to be important stimuli for the determination and maintenance of cellular phenotype and function. Many cells are constantly exposed in vivo to cyclic pressure, shear stress, and/or strain. Therefore, the ability to study the effects of these stimuli in vitro is important for understanding how they contribute to both normal and pathologic states. While there exist commercial as well as custom-built devices for the extended application of cyclic strain and shear stress, very few cyclic pressure systems have been reported to apply stimulation longer than 48 h. However, pertinent responses of cells to mechanical stimulation may occur later than this. To address this limitation, we have designed a new cyclic hydrostatic pressure system based upon the following design variables: minimal size, stability of pressure and humidity, maximal accessibility, and versatility. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) was utilized to predict the pressure and potential shear stress within the chamber during the first half of a 1.0 Hz duty cycle. To biologically validate our system, we tested the response of bone marrow progenitor cells (BMPCs) from Sprague Dawley rats to a cyclic pressure stimulation of 120/80 mm Hg, 1.0 Hz for 7 days. Cellular morphology was measured using Scion Image, and cellular proliferation was measured by counting nuclei in ten fields of view. CFD results showed a constant pressure across the length of the chamber and no shear stress developed at the base of the chamber where the cells are cultured. BMPCs from Sprague Dawley rats demonstrated a significant change in morphology versus controls by reducing their size and adopting a more rounded morphology. Furthermore, these cells increased their proliferation under cyclic hydrostatic pressure. We have demonstrated that our system imparts a single mechanical stimulus of cyclic hydrostatic pressure and is capable of at least 7 days of continuous operation without affecting cellular viability. Furthermore, we have shown for the first time that BMPCs respond to cyclic hydrostatic pressure by alterations in morphology and increased proliferation.

Keywords: mechanobiology, progenitor cells, mechanical stimulation, bioreactor, cell behavior

Introduction

Within the normal cellular microenvironment, it has been shown that cells both receive and respond to biochemical and biomechanical signals. The role of mechanical signaling has become increasingly important for understanding cellular function in both normal and pathologic states [1,2]. The effects of mechanical stimulation—such as stretch, fluid shear, and hydrostatic pressure—have been extensively studied in many cell types [3–9].

Maintaining cell viability under defined mechanical conditions is important for studies in cellular mechanobiology. While the application of stretching and shear forces can be adequately provided for extended periods of time in vitro with commercially available and custom-designed devices [10–14], the extended application of hydrostatic pressure has proven problematic. Cyclic hydrostatic pressure is thought to be important in the function and/or dysfunction of many different cell types [8,9,15–18]. The hurdle in conducting long-term (>2 days) in vitro experimentation using applied hydrostatic pressure in cell culture has been maintaining proper humidification, and this is especially a concern for the cyclic application of pressure. Because cyclic pressure generally requires constant movement of air through the culture chamber, water can evaporate from the culture media, upsetting the osmotic balance and disrupting cellular function, eventually leading to cell death.

To our knowledge, two devices have been published that reported the application of long-term cyclic pressure [18,19], while several devices have been reported for shorter experiments (<2 days) [8,9,17]. The previously reported devices required expensive, complicated computer control algorithms and/or utilized inadequate humidification systems. Our goal was to utilize the best features of the previous designs to develop a space- and cost-efficient system for the long-term application of fully humidified, cyclic pressure of multiple magnitudes and frequencies. To biologically validate the system, we demonstrate its use to stimulate bone marrow progenitor cells (BMPCs) for up to 7 days.

Methods

System Design

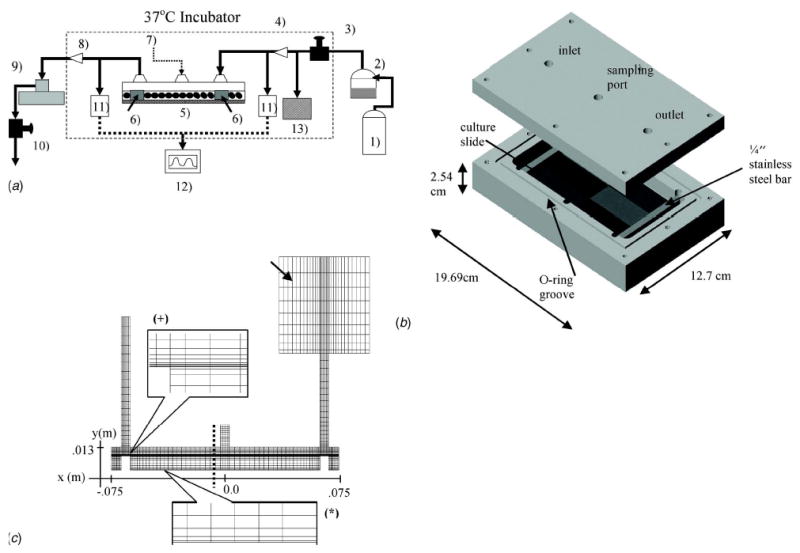

The development of our cyclic pressure system (Fig. 1(a)) was centered on four key design goals: minimal size, stability of pressure and humidity, maximal accessibility, and versatility. First, we designed the system to occupy only ~1400 cm3 within an incubator (inner dimensions 15×7.8×1.3 cm3) by minimizing the number of necessary components within the controlled environment and keeping the rest of the system outside. The pressurized culture chamber consists of a single continuous vessel into which microscope slides, scaffolds, or other materials may be placed (Fig. 1(b)). Initial observations of liquid ripples being generated by the impinging inlet air led to the placement of two stainless steel bars placed directly below the inlet and outlet ports to prevent the jet impingement from causing a visible liquid disturbance, which could potentially be converted into cyclic shear stresses applied to the cells. The stainless steel bars also function to constrain the slides, or other materials being stimulated, to the bottom of the chamber.

Fig. 1.

Schematic and CFD model of the cyclic hydrostatic pressure system. (a) A constant pressure source (1) provides the bulk airflow that powers the cyclic pressure system. The pressure source consists of an in-house air pump and pure CO2 blended together (5% CO2, 20% O2, 75% N2). A heated passover circuit (2) humidifies the air to ~100% before it passes through a resistor that controls the mean pressure (3). The air then passes through a sterile filter (4) before it enters) the culture chamber (5) and builds a static pressure in the dead space above the culture media. Two stainless steel bars (6 deflect the incoming air and provide weight to stabilize the culture surface. An injection port (7) provides access for) media sampling or chemical injection. The air then passes through a second sterile filter (8) on its way to a solenoid valve (9 . When the valve is closed, pressure builds inside the system. When the valve is open, the pressure is released through a second resistor (10) that controls the diastolic pressure. Two pressure transducers (11) and their associated monitor (12) display the pressure inside the cyclic pressure chamber. A check valve (13), which has a cracking pressure of 250 mm Hg, allows the system to release built-up pressure in the event the one of the filters becomes obstructed. The dashed box represents the interior of the incubator. (b) A three-dimensional model of the cyclic hydrostatic pressure chamber depicting the lid with the inlet, outlet, sampling ports, culture slides, o-ring groove, and stainless steel bars. (c) A 2-D CFD model of the pressure chamber using linear quadratic elements. Two boundary layers were created, one at the air/liquid interface (+), and the other at the base of the chamber where the cells would be located (*). A sealed box (arrow) with an equivalent 2-D volume to the volume of the circuit between the chamber and the solenoid was used at the outlet. The x and y axes depict positional information (in meters) relevant to the velocity, pressure, and shear stress plots in subsequent figures.

In order to achieve extended application of cyclic hydrostatic pressure, the dry air used to drive the system was properly humidified. It has been documented that cellular dysfunction increases with time and deviation from optimal humidity (45 g/m3) [20]. To address this, we attempted several different options for humidifying the air, including those used by Hasel et al. [18] and Watase et al. [16], before finding that a heated passover humidifier (MR730, Fisher&Paykel, Auckland, New Zealand) was the most efficient and reproducible method for humidifying the air. This device employs a self-feeding heated water reservoir and a heated conduit, which maintains the humidity near 100% as the air enters the culture chamber, and has been used previously in the cyclic pressure system described by Pugin et al. [9]. Our pressure source was the internal house air system (blended with a small amount of pure carbon dioxide), which does not significantly fluctuate. Therefore, after setting the resistors that control the mean and pulse pressure to reach the desired pressure waveform, the system operated within accepted limits without the assistance of computer control.

The design requirement of maximal accessibility (i.e., the capability of media sampling, chemical addition, and/or addition or removal of biological samples in a sterile manner) was accomplished by using a single continuous culture chamber, a central injection port for sampling media and adding culture supplements, and sterile 0.2 μm filters (Acro50, Pall, East Hills, NY) at both the inlet and outlet of the chamber to allow its removal from the incubator as necessary.

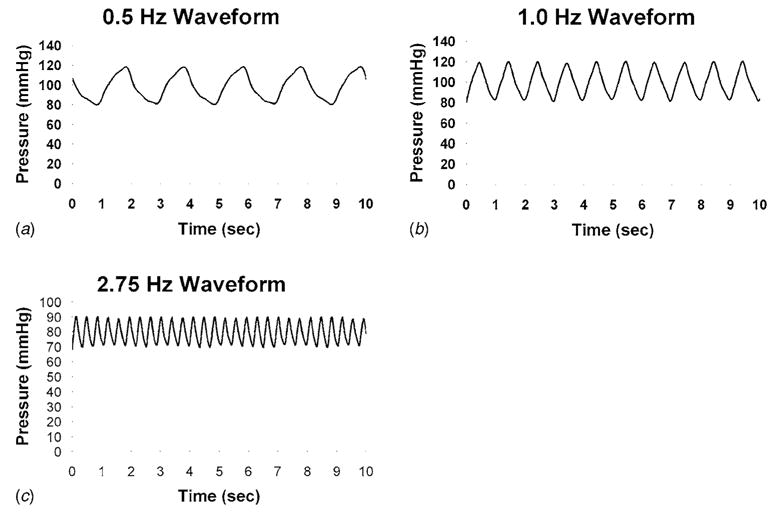

The final design requirement of versatility (i.e., the ability to apply several different physiologically relevant magnitudes and frequencies of cyclic pressure) was achieved by using three NE555 timers (Fairchild, McLean, VA) built into a single circuit to apply 0.5, 1.0, or 2.75 Hz frequency signals on a downstream solenoid (Cole Parmer, Vernon Hills, IL), and pre- and post-solenoid passive resistors (Cole Parmer) to control the pressure magnitude. Waveforms generated by the system were captured using a clinical pressure monitor (Spacelabs, Issaquah, WA) connected to a data acquisition board interfaced with LabView® (National Instruments, Austin, TX) data acquisition software (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Pressure wave forms collected with the solenoid valve frequency set to (a) 0.5 Hz, (b) 1.0 Hz, and (c) 2.75 Hz

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD)

Because a time-varying jet of air impacts the culture medium over the cells throughout the operational cycle, we wanted to ensure that the resulting hydrostatic pressure wave was evenly distributed along the length of the chamber, and no significant shear stress was applied to the cells. To that end, computational modeling of the cyclic pressure chamber was performed using CFD-ACE (Version 2002.2.16, CFDRC, Huntsville, AL).

Because of the significant computational costs associated with a three dimensional analysis in the required model, a 2-D representation of the pressure chamber with approximately 3500 structured linear quadratic elements was generated by the plane passing through the centerlines of the inlet and outlet ports of the chamber (Fig. 1(c)). A boundary layer was created at the air/liquid interface as well as the bottom of the chamber, the region of interest vis-à-vis shear forces. An inlet flow extension with a length-to-diameter ratio of 12.5 was used to establish a fully developed flow for the air entering the chamber. The 2-D volume between the end of the chamber and the downstream solenoid was estimated by multiplying the tubing length by its diameter and modeled as a closed compliance volume attached to the outlet of the model.

The computational model included the volume of fluid (VOF) multiphase formulation [21], which was solved in conjunction with the standard mass, and momentum conservation equations to solve the fluid dynamics field and the air/liquid boundary geometry at each time step using an unsteady solver with implicit first-order Euler time integration [21]. The air/liquid interface was reconstructed using a second order piecewise linear interface calculation (PLIC). Each time step was calculated via the Courant-Friedrichs-Levy (CFL) parameter (set to 0.2), which restricts the size of the time step to ensure the free surface does not cross an entire element within that time step. The air was modeled as a compressible gas (MW=29 g, ν=1.589×10−5 m2-s−1), while the culture media was modeled as water at 37°C (ρ=1000 kg-m−3; μ=6.82×10−4 kg-m−1-s−1).

The inlet boundary condition was a time-varying pressure obtained with a first-order linear regression of the first half of a duty cycle (80 to 120 mm Hg) from the 1 Hz data depicted in Fig. 2(b). Since the normal operation of the system occurs as an oscillation between 80 and 120 mm Hg, modeling only the first half of the cycle was sufficient to determine if any shear stresses developed on the base of the chamber. The outlet boundary condition was modeled as a closed compliance chamber to simulate the air volume held between the chamber and the closed solenoid valve (removed during post-processing for scaling). Wall shear stress (τ) was calculated from the velocity vector along the long axis of the chamber [22]. Post-processing line probes were used to extract the pressure, velocity, and τ from horizontal and vertical planes at various time points.

Demonstrative Application of Cyclic Pressure to Cell Culture

In order to biologically validate and demonstrate the effect of cyclic pressure on progenitor cell morphology and proliferation, bone marrow progenitor cells (BMPCs) were harvested from Sprague Dawley rats using previously described methods [6] and expanded with Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Media (DMEM, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 10% calf serum. Cells less than passage 4 were utilized. At the start of each experiment, 7000 cells/cm2 were plated on collagen-coated slides (Flexcell International, Hillsborough, NC). Following a 48 h incubation period, the slides were placed into the cyclic pressure system and exposed to 120/80 mm Hg, 1.0 Hz cyclic hydrostatic pressure for 7 days. Controls were kept in static incubator conditions.

Pressure, Flow, Dissolved Gas, and Humidity Measurements

Media samples were obtained every 24 h to measure pH, pCO2, and pO2 using a dissolved gas analyzer (ABL5; Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark). Concurrent with the media samples, the system pressure and air flow rates were measured using a SpaceLabs pressure monitor and gas rotameters, respectively. The calculated HCO3− output from the ABL5 was used as a measure of proper humidification. Assuming that BMPCs cells do not produce their own bicarbonate through carbonic anhydrase [23], increases or decreases in HCO3− can indicate a change in the concentration of media components due to water evaporation or condensation, respectively.

The relative percent humidity was calculated for the system after each experiment according to:

| (1) |

The total volume of air used during an experiment (Vair) was calculated from flow rates recorded every 24 h. The total volume of water used (VH20) was determined by subtracting the total water left in the humidifier system from the starting volume. The maximum vapor density (MVD) was estimated by a fourth order polynomial extrapolation of tabular data for temperature versus maximum vapor pressure [24]. The average inlet air temperature was measured by a temperature probe at the end of the humidification tube.

Cellular Analysis

At the termination of each experiment, the BMPCs were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 5 min. Proliferation was quantified by staining nuclei with Hoechst (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and averaging the cells counted in ten random fields of view taken at 20×. Each experiment was normalized to its respective control. To perform morphologic analysis, cells were stained with Coomassie Blue (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) to enhance contrast. Five random fields of view were taken at 10×, and cellular area was measured for each cell in the field of view using Scion Image (Scion Corp, Frederick, MD) [6,25,26]. Artificial borders were drawn as necessary to separate the cells for the edge-detection function in Scion Image. The shape index (SI) was also calculated for each cell in the field of view and is defined as:

| (2) |

where P and A are the measured perimeter and area of the cell, respectively [27]. SI is 1 for cells that are perfect circles and approaches 0 for cells that are spindle shaped.

Statistics

All data are presented as mean±standard error of the mean. Because the average cell counts were normalized to the control, a one-sample t-test was performed with μ=1 and α =0.05. For morphologic analyses, a paired Student’s t-test was used to make statistical comparisons. P-values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

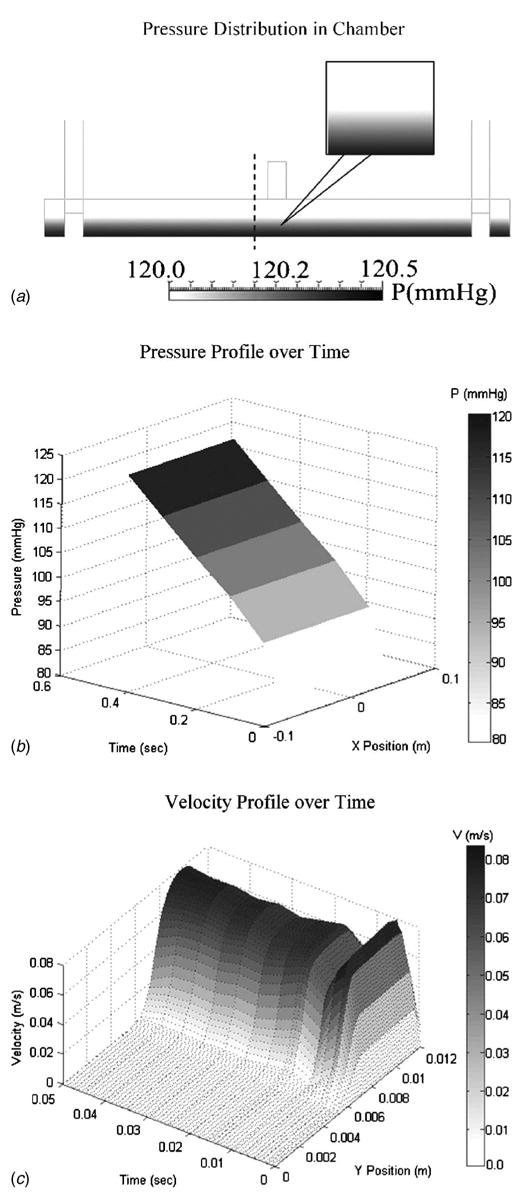

The CFD analysis of the cyclic pressure chamber revealed a uniform pressure field established along the length of the chamber and rose steadily over time (Figs. 3(a) and 3(b)). The pressure field did show a minor increase above the applied gas pressure due to the pressure head developed from the 6.3 mm of media above the cells, but this was less than 1% and was considered negligible (Fig. 3(a)). The maximum calculated wall shear stress was ~1.2×10−4 Pa, which is insignificant compared to the pressure that the cells experienced, and confirmed our assumption that our system is truly hydrostatic. A three-dimensional velocity profile (Fig. 3(c)) over time shows plug flow developing into the characteristic parabolic flow within the chamber as time advances. At t =0.01 s, a dip in the velocity occurs, which we believe may indicate the initiation of compression and a resultant reflection of the air wave. Following this drop, the velocity profile oscillates slightly while progressing into the characteristic parabolic profile associated with laminar flow by 0.05 s, and remains parabolic for the rest of the simulated time (not shown). We have calculated the Reynolds number (Re) to be <50, thus confirming the establishment of a laminar flow in our viscous model. The stainless steel bars, which were used as diffusers to deflect the downward impingement force of the inlet air, prevented significant disturbances in the liquid layer. However, we did detect some liquid velocity (0.02 m-s−1 maximum) during the development of the air flow that was transferred ~0.8 mm into the liquid layer. Our shear stress calculations suggest that although liquid movement was generated, no significant wall shear stress resulted.

Fig. 3.

(a) Results for CFD analysis revealing a uniform pressure distribution across the length of the chamber. The dashed line indicates the position from which the velocity profile (c) was extracted. (b) Results for the pressure versus time versus position across the bottom of the cyclic pressure chamber indicate a smooth, continuous increase in pressure over the course of the simulation and along the length of the chamber. (c) A three-dimensional spatial velocity profile over time shows the development of parabolic flow in the air space, and that the velocity is zero in the liquid space (air-liquid interface located at y=6.3 mm).

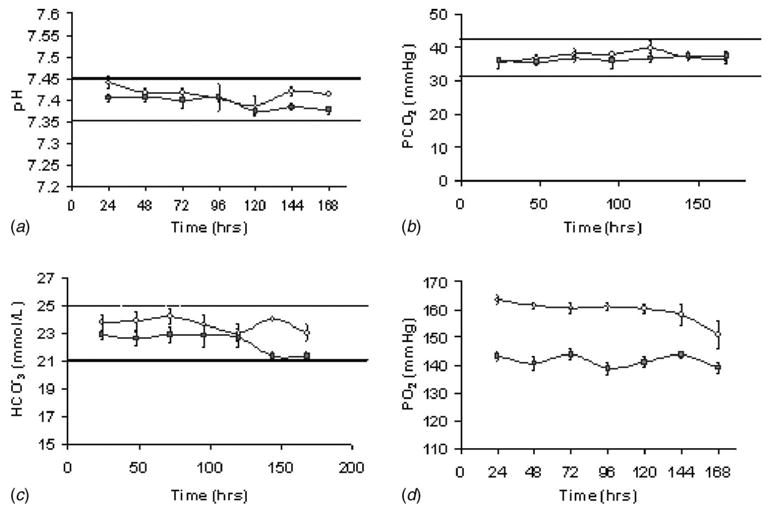

The cyclic pressure system operated at 120.3±0.3 mm Hg and 83.1±1.7 mm Hg systolic and diastolic pressures, respectively, at 1 Hz for the 7 day demonstrative cell culture experiments. The average flow rate through the system was measured at 1.80±0.41 L/min. Dissolved gas measurements taken over the course of the experiments showed that the pH, pCO2, and HCO3− values remained similar between pressure and control groups and were within acceptable limits indicated by the dashed lines (Fig. 4). The values for pO2 were elevated in the cyclic pressure group because of the increase in ambient pressure. However, the ratio of the partial pressure of dissolved oxygen to the total pressure (FiO2) was nearly equivalent for the control and cyclic pressure groups (18.6±0.1% versus 18.1±0.2%, respectively). Furthermore, other research using cyclic pressure has shown that this slight increase does not have an effect on cellular proliferation [16]. The average relative humidity at 37°C was calculated to be 99% ±4% (absolute humidity 49.3±3.4 g/m3). These values resulted from the operation of the humidifier at 38–39°C to ensure full saturation at 37°C when the air crossed into the incubator section of tubing.

Fig. 4.

Automated blood lab readings demonstrate similar values between the cyclic pressure (○) and control experiments (▪) for (a) pH, (b) pCO2, and (c) HCO3−. (n=8). Dashed lines indicate the upper and lower limits for acceptable values for each measured variable. The stability in the HCO3− values indicates sufficient humidification. (d) pO2 values for pressure were elevated over controls throughout the experiments due to the increase in ambient pressure. These values, although statistically different (p<0.05), had similar FiO2 values when adjusted for ambient pressure and are not considered biologically significant.

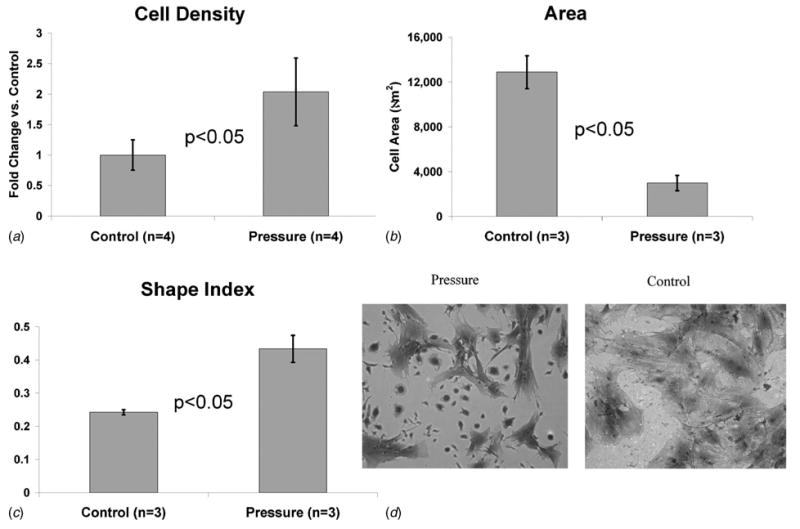

BMPCs exposed to cyclic pressure showed twofold increase in proliferation (Fig. 5(a)). They also showed a significant decrease in area (Fig. 5(b)) and significant increase in shape index (Fig. 5(c)), which indicates a more rounded morphology.

Fig. 5.

(a) Quantification of BMPC proliferation via cell counts revealed a 1.8-fold increase in cells exposed to cyclic pressure for 7 days compared to controls. (b) BMPCs exposed to cyclic pressure demonstrated a significant reduction in their total area. (c) Shape index measurements indicated a more rounded morphology for BMPCs under cyclic pressure. (d) Coomassie blue stained images of pressure (left) and control (right) reflect the measured differences in morphology and proliferation that occurred upon stimulation with cyclic pressure. Images taken at 10× magnification.

Discussion

We have demonstrated here a new experimental system capable of extended application of cyclic hydrostatic pressure to cell culture. We utilized a simplified 2-D computational model that represented the position of highest air velocity and potential for liquid perturbation to demonstrate negligible wall shear stresses at the base of the chamber (cell culture position). While the 2-D computational model does not fully describe the entire flow field in the chamber, it provided insights about the most critical region for air-liquid interaction. Furthermore, although we believe that there are no appreciable changes to mass transport due to the minimal liquid perturbation from the airflow/liquid interaction at the surface, we cannot say for certain that this does not lead to slight changes in nutrient concentration at the level of the microenvironment of the cell.

The current design established a stable system at various frequencies of operation without requiring the use of a computer-control algorithm, which would have added unnecessary cost and complexity. The maximum measured pulse pressure possible at the 2.75 Hz waveform (Fig. 2(c)) was 20 mm Hg due to inertial effects of the air. However, this is consistent with neonatal blood pressure and frequency and could therefore be useful in testing the effects of such a stimulus [28]. Furthermore, our system is much smaller (at least one-third of the foot-print required within the incubator) than those previously described. Our design allows us to incorporate the use of commercially available matrix-coated surfaces that are utilized in the Flexcell Streamer™ shear stress system. Thus, comparison between cell responses using that device and our device will be readily available for future studies.

The use of a heated passover humidifier, although not novel, provides sufficient vapor saturation to ensure minimal to no media loss in the culture chamber. This was evident in the stability of our HCO3− measurements (Fig. 4(c)). Such results were not achieved with other humidifier designs assessed, including a room temperature passover system [18] and the passage of air through a large volume of water at 37°C (bubble humidifier).

The ability of the BMPCs to respond to cyclic stretching was recently reported by our laboratory [6]. Though preliminary in nature, we have shown here that cyclic pressure alters the cellular morphology and proliferative rates in BMPCs over a 7 day period (Fig. 5). BMPCs are responsive to cyclic pressure alone, i.e., without other stimulation such as D3 [8] or chondrogenic medium [29]. Our finding that cyclic pressure enhances the proliferation of progenitor cells is consistent with that of Rubin et al. [30], who reported a trend towards increased proliferation when D3-stimulated BMPCs were exposed to an increase in static pressure. These findings are in contrast to our previous findings that BMPC proliferation is inhibited when subjected to cyclic stretch [6]. A means to stimulate BMPC proliferation without the addition of biochemicals may prove to be useful for the ex vivo expansion of these cells for use in cell therapy. That is, the use of cyclic pressure could potentially decrease the expansion time required for adequate numbers of cells for use in these therapies, while other forces, such as cyclic strain, could halt proliferation and guide differentiation of the BMPCs [6].

In conclusion, the cyclic pressure system we have developed is versatile, compact, and does not require complex control algorithms to operate in its current configuration. We have demonstrated its ability to culture BMPCs under cyclic hydrostatic pressure for up to 7 days and have shown morphologic and proliferative changes in these cells as a result of cyclic pressure stimulation.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by R01 HL069368, T32 EB001026, the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (awarded to Mr. Maul), and an American Heart Association post-doctoral fellowship (awarded to Dr. Nieponice).

Footnotes

Contributed by the Bioengineering Division of ASME for publication in the Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. Manuscript received September 27, 2005; final manuscript received June 23, 2006. Review conducted by Cheng Dong.

References

- 1.Benjamin M, Hillen B. Mechanical Influences on Cells, Tissues and Organs—‘Mechanical Morphogenesis’. Eur J Morphol. 2003;41(1):3–7. doi: 10.1076/ejom.41.1.3.28102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vorp DA, Maul TM, Nieponice A. Molecular Aspects of Vascular Tissue Engineering. Front Biosci. 2005;10:768–789. doi: 10.2741/1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leung DY, Glagov S, Mathews MB. Cyclic Stretching Stimulates Synthesis of Matrix Components by Arterial Smooth Muscle Cells in Vitro. Science. 1976;191(4226):475–477. doi: 10.1126/science.128820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tatsumi R, Sheehan SM, Iwasaki H, Hattori A, Allen RE. Mechanical Stretch Induces Activation of Skeletal Muscle Satellite Cells in Vitro. Exp Cell Res. 2001;267(1):107–114. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banes AJ, Lee G, Graff R, Otey C, Archambault J, Tsuzaki M, Elfervig M, Qi J. Mechanical Forces and Signaling in Connective Tissue Cells: Cellular Mechanisms of Detection, Transduction, and Responses to Mechanical Deformation. Curr Opin Orthop. 2001;12(5):389–396. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamilton DW, Maul TM, Vorp DA. Characterization of the Response of Bone Marrow Derived Progenitor Cells to Cyclic Strain: Implications for Vascular Tissue Engineering Applications. Tissue Eng. 2004;10(34):361–370. doi: 10.1089/107632704323061726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshikawa T, Peel SA, Gladstone JR, Davies JE. Biochemical Analysis of the Response in Rat Bone Marrow Cell Cultures to Mechanical Stimulation. Biomed Mater Eng. 1997;7(6):369–377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagatomi J, Arulanandam BP, Metzger DW, Meunier A, Bizios R. Effects of Cyclic Pressure on Bone Marrow Cell Cultures. ASME J Biomech Eng. 2002;124(3):308–314. doi: 10.1115/1.1468867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pugin J, Dunn I, Jolliet P, Tassaux D, Magnenat JL, Nicod LP, Chevrolet JC. Activation of Human Macrophages by Mechanical Ventilation in Vitro. Am J Physiol. 1998;275(6 Pt 1):L1040–1050. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.6.L1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banes AJ, Link GW, Gilbert JW, Tran Son Tay R, Monbureau O. Culturing Cells in a Mechanically Active Environment. Am Biotechnol Lab. 1990;8(7):12–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blackman BR, Barbee KA, Thibault LE. In Vitro Cell Shearing Device to Investigate the Dynamic Response of Cells in a Controlled Hydrodynamic Environment. Ann Biomed Eng. 2000;28(4):363–372. doi: 10.1114/1.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frangos JA, Eskin SG, Mcintire LV, Ives CL. Flow Effects on Prostacyclin Production by Cultured Human Endothelial Cells. Science. 1985;227(4693):1477–1479. doi: 10.1126/science.3883488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiu J-J, Chen L-J, Chen C-N, Lee P-L, Lee C-I. A Model for Studying the Effect of Shear Stress on Interactions between Vascular Endothelial Cells and Smooth Muscle Cells. J Biomech. 2004;37(4):531–539. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Archambault JM, Elfervig-Wall MK, Tsuzaki M, Herzog W, Banes AJ. Rabbit Tendon Cells Produce Mmp-3 in Response to Fluid Flow without Significant Calcium Transients. J Biomech. 2002;35(3):303–309. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dobrin PB. Mechanical Factors Associated with the Development of Intimal Hyperplasia with Respect to Vascular Grafts. In: Dobrin PB, editor. Intimal Hyperplasia. Landes; Georgetown: 1994. pp. 85–104. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watase M, Awolesi MA, Ricotta J, Sumpio BE. Effect of Pressure on Cultured Smooth Muscle Cells. Life Sci. 1997;61(10):987–996. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(97)00603-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parkkinen JJ, Lammi MJ, Inkinen R, Jortikka M, Tammi M, Virtanen I, Helminen HJ. Influence of Short-Term Hydrostatic Pressure on Organization of Stress Fibers in Cultured Chondrocytes. J Orthop Res. 1995;13(4):495–502. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100130404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hasel C, Durr S, Bruderlein S, Melzner I, Moller P. A Cell-Culture System for Long-Term Maintenance of Elevated Hydrostatic Pressure with the Option of Additional Tension. J Biomech. 2002;35(5):579–584. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00237-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sumpio BE, Widmann MD, Ricotta J, Awolesi MA, Watase M. Increased Ambient Pressure Stimulates Proliferation and Morphologic Changes in Cultured Endothelial Cells. J Cell Physiol. 1994;158(1):133–139. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041580117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams R, Rankin N, Smith T, Galler D, Seakins P. Relationship between the Humidity and Temperature of Inspired Gas and the Function of the Airway Mucosa. Crit Care Med. 1996;24(11):1920–1929. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199611000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.CFDRC Research Corporation. CFD-ACE(U) Modules. Vol. 25 Huntsville, AL: 2002. pp. 15–1. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kute SM, Vorp DA. The Effect of Proximal Artery Flow on the Hemodynamics at the Distal Anastomosis of a Vascular Bypass Graft: Computational Study. ASME J Biomech Eng. 2001;123(3):277–283. doi: 10.1115/1.1374203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Billecocq A, Emanuel JR, Levenson R, Baron R. 1 Alpha,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Regulates the Expression of Carbonic Anhydrase II in Nonerythroid Avian Bone Marrow Cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87(16):6470–6474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nave CR, Nave BC. Physics for the Health Sciences. Saunders; Philadelphia: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamilton DW, Riehle MO, Rappuoli R, Monaghan W, Barbucci R, Curtis AS. The Response of Primary Articular Chondrocytes to Micrometric Surface Topography and Sulphated Hyaluronic Acid-Based Matrices. Cell Biol Int. 2005;29(8):605–615. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamilton DW, Riehle MO, Monaghan W, Curtis AS. Articular Chondrocyte Passage Number: Influence on Adhesion, Migration, Cytoskeletal Organisation and Phenotype in Response to Nano- and Micro-Metric Topography. Cell Biol Int. 2005;29(6):408–421. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kataoka N, Ujita S, Sato M. Effect of Flow Direction on the Morphological Responses of Cultured Bovine Aortic Endothelial Cells. Med Biol Eng Comput. 1998;36(1):122–128. doi: 10.1007/BF02522869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whaley L, Wong D. Nursing Care of Infants and Children. Mosby; St. Louis: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Angele P, Yoo JU, Smith C, Mansour J, Jepsen KJ, Nerlich M, Johnstone B. Cyclic Hydrostatic Pressure Enhances the Chondrogenic Phenotype of Human Mesenchymal Progenitor Cells Differentiated in Vitro. J Orthop Res. 2003;21(3):451–457. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(02)00230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rubin J, Biskobing D, Fan X, Rubin C, Mcleod K, Taylor WR. Pressure Regulates Osteoclast Formation and Mcsf Expression in Marrow Culture. J Cell Physiol. 1997;170(1):81–87. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199701)170:1<81::AID-JCP9>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]