Abstract

The aim of the present work was to depict the metabolic pathways involved in extra-cellular production of lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) by adipocytes. LPA was followed by quantifying the accumulation of LPA in the incubation medium (conditioned medium: CM) of 3T3F442A adipocytes, or human adipose tissue explants, using a radioenzymatic assay. Surprisingly, after separation from the cells, the amount of LPA present in CM could significantly be increased by further incubation at 37°C. This suggested the presence of a LPA-synthesizing activity (LPA-SA) in CM. LPA-SA appeared as a soluble activity which was inhibited by divalent ion chelators: EDTA and phenanthrolin. The effect of EDTA was preferentially reverted by CoCl2, as described for a lysophospholipase D- (lyso-PLD) activity previously identified in rat plasma. LPA concentration could also be increased by treatment with a bacterial PLD, demonstrating the presence of PLD-sensitive LPA-precursors (mainly lysophosphatidylcholine) in adipocyte CM. LPA-SA could be increased by addition of exogenous lysophosphatidylcholine, lysophosphatidylglycerol, or lyso-platelet activating factor, demonstrating that LPA-SA resulted from the action of a lyso-PLD. LPA-SA was not inhibited, but rather activated, by primary alcohol (ethanol and 1-butanol), suggesting that adipocyte lyso-PLD was not a classical PLD. Finally, LPA-SA was found to be weaker in CM of undifferentiated adipocyte (preadipocytes) as compared to CM of differentiated adipocytes. In conclusion, our results reveal the existence of a secreted lyso-PLD activity regulated during adipocyte-differentiation and involved in extra-cellular production of synthesis of LPA by adipocytes.

Keywords: Adipocytes; secretion; Animals; Cells, Cultured; Culture Media, Conditioned; metabolism; Edetic Acid; metabolism; Female; Heat; Humans; Lysophosphatidylcholines; metabolism; Lysophospholipids; biosynthesis; Phenanthrolines; metabolism; Phosphoric Diester Hydrolases; secretion

Introduction

Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) is a bioactive phospholipid known to be involved in the control of numerous cell functions via its interaction with specific G-protein coupled receptors belonging to the Endothelium Differentiation Gene family (EDG-2, EDG-4 and EDG-7) (1,2). Therefore, the availability of LPA at the extra-cellular face of plasma membrane conditions the intensity LPA responsiveness.

Two major pathways of LPA synthesis have been described: (i) phospholipase A2-dependent deacylation of phosphatidic acid (3–5); (ii) lysophospholipase D-dependent hydrolysis of other lysophospholipids such as lysophosphatidylcholine (6–8). The precise contribution of these pathways in cellular production of LPA is still a matter of debate.

LPA is found in abundance in serum (bound to albumin) (9–12), resulting from platelet aggregation (10,13). However, LPA is also found in other biological fluids such as plasma of patients with ovarian cancer (14), ascites (15), aqueous humor (16), follicular fluids (8), extracellular fluid of adipose tissue (17). This suggests the involvement of other cell types in LPA production. LPA can indeed be produced by cancer cells (18) and adipocytes (17).

The initial aim of the present study was to depict the metabolic pathways involved in extracellular production of LPA by adipocytes. We found that, in parallel to LPA, adipocyte secrete a soluble lyso-phospholipase D catalyzing hydrolysis of lysophosphatidylcholine into LPA.

Methods

Culture

3T3F442A preadipocytes were seeded at a density of 1200 cells/cm2 and grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% calf serum. At confluence, differentiation of preadipocytes into adipocytes was achieved by growing cells in DMEM supplemented with 10% foetal calf serum plus 50 nM insuline as reported previously (17,19). Before utilization 3T3F442A adipocytes or preadipocytes were washed twice with sterile PBS containing 1% (w/v) fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (BSA) in order to remove all the LPA of serum,

Human adipose tissue was obtained from healthy, drug free women, undergoing abdominal dermolipectomy for plastic surgery according to the regulation of the Ethical Committee of Faculty Hospital. Adipose tissue was carefully dissected out from blood vessels and cut in small pieces (average weight 20 mg) as previously described (20). Before utilization adipose tissue explants were washed twice in sterile PBS.

In order to study extra-cellular production of LPA, 3T3F442A adipocytes (3 cm diameter plate) or human adipose tissue explants (0.7 g) were incubated in 1 ml of sterile Hepes-buffer (HB) (118 mM NaCl, 6 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 12.4 mM Hepes, 6 mM glucose, pH 7.4) supplemented with 1% fatty acid-free BSA (HB-BSA). Incubations were performed at 37°C in an humidified atmosphere containing 7% CO2. At different time point (0 to 48 h), incubation medium was collected, centrifuged for 15 min at 800 g to eliminate detached cells and cell debris, and frozen at −20°C before LPA quantification. The collected incubation media were called: condtioned media (CM). LPA quantification was performed either directly after defrosting (initial) or after further incubation of the defrosted sample at 37°C for various period of time in sterile condition.

Quantification of LPA

Quantification of LPA was performed using a radioenzymatic assay as previously described (21). Phospholipids were extracted from CM with 1 volume of 1-butanol followed by evaporation of the solvent under nitrogen. Dry phospholipids were resuspended in 200 μl of reaction medium (1 μl [14C]oleoyl CoA (RAS 55 mCi/mmole, NEN), 20 μl Tris (pH 7.5) 200 mM, 10 μl of semi-purified lysophosphatidic acid acyl transferase (LPAAT), 8 μl of sodium orthovanadate 500 μM, and 161 μl H2O (containing 1mg/ml Tween 20), and incubated for 120 min at 20°C. The mixture was vortexed every 15 min. The reaction was stopped by addition of 400 μl of CHCl3/MeOH/HCl 12N (1/1/0.26) followed by a vigorous shaking and by 10 min centrifugation at 3000 g. The lower CHCl3 phase was evaporated under nitrogen, resuspended in 20 μl of CHCl3/MeOH (1/1), spotted on a silica gel 60 TLC glass plate (Merck), and separated using CHCl3/MeOH/NH4OH/H2O (65/25/0.9/3) as a solvent. The plate was autoradiographied overnight to localize the [14C]phosphatidic acid spots which were then scrapped and counted with 3 ml of scintillation cocktail.

Phospholipids

Palmitoyl-, stearoyl-, oleoyl-lysophosphatidylcholine palmitoyl-lyso-platelet activating factor, and dioleoyl-phosphatidic acid, were from Sigma. Oleoyl-lysophosphatidylglycerol was from Avanti Polar Lipids. Linoleoyl-lysophosphatidylcholine was obtained by treatment of dilinoleoyl-phosphatidylcholine (Aventi Polar Lipids) with pancreatic phospholipase A2 (Sigma) followed by separation and extraction on TLC. Arachidonoyl-lysophosphatidylcholine was obtained by treatment of palmitoyl-arachidonoyl-phosphatidylcholine (Sigma) with type XI lipase from Rhizopus arrhizus (Sigma) followed by separation and extraction on TLC. All phospholipids were solubilized in methanol, evaporated under nitrogen, and resuspended in HB-BSA. The final concentration was verified by using phosphorus measurement (22).

Results

1/ Presence of a LPA-synthesizing activity (LPA-SA) in adipocyte conditioned medium

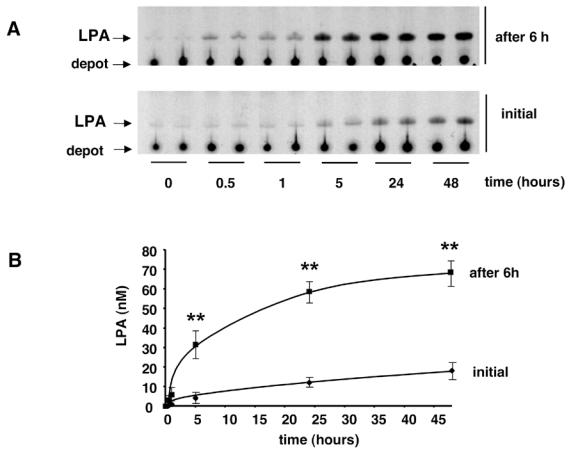

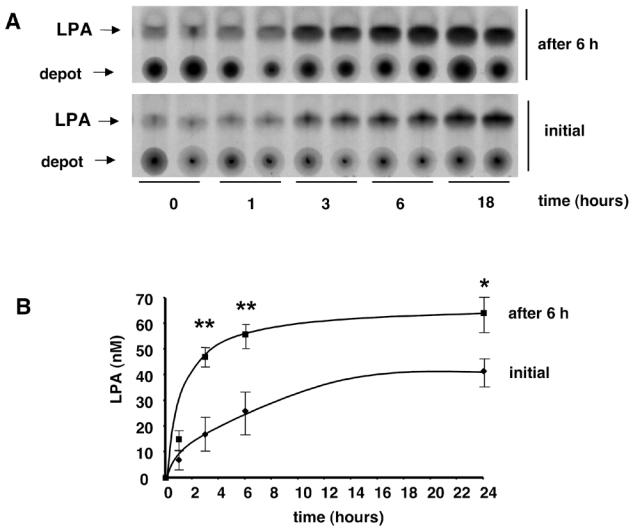

As previously described (17) adipocytes produce LPA in their extracellular medium. This was demonstrated using qualitative assays (bioassay and [32P] labeling). In the mean time we developed a high sensitive radioenzymatic assay for LPA quantification (21). This new method was used to determine the concentration of LPA present in conditioned medium (CM) obtained after incubation of 3T3F442A adipocytes, or human adipose tissue explants, in HB-BSA (see Material and Methods) for various period of time. As shown in Figure 1 (“initial” curves) the amount of LPA present in CM increased with time of incubation with 3T3F442A adipocyte (Figure 1) or human adipose tissue explants (Figure 2). This corresponds to the basal extra-cellular production of LPA by adipocytes.

Figure 1. Presence of a LPA-synthesizing activity in 3T3F442A adipocyte conditioned medium.

3T3F442A adipocytes were incubated in HB-BSA. At different time point, the conditioned medium was collected and frozen. LPA was quantified either immediatly after defrosting (Initial) or 6h after (after 6h) further incubation at 37°C of defrosted conditioned medium. (A) autoradiography of representative experiment; (B) mean ± SE of 3 separate experiments. ** corresponds to P<0.01 when comparing with initial value (Student’s t test).

Figure 2. Presence of a LPA-synthesizing activity in human adipocyte conditioned medium.

Human adipose tissue explants were incubated in HB-BSA. At different time point the conditioned medium was collected and frozen. LPA was quantified either immediatly after defrosting (Initial) or 6h after (after 6h) further incubation at 37°C of defrosted conditioned medium. (A) autoradiography of representative experiment; (B) mean ± SE of 3 separate experiments. ** corresponds to P<0.01, and * corresponds to P<0.05, when comparing with initial value (Student’s t test).

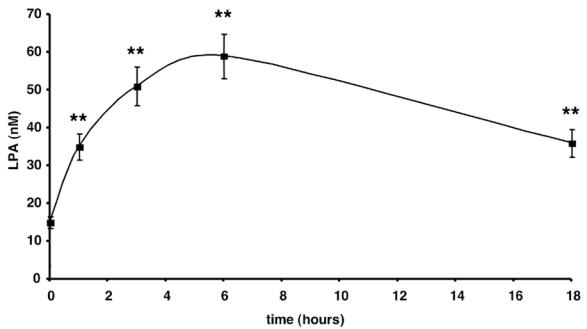

Surprisingly, when CM (which were centrifuged in order to eliminate detached cells and cell debris) was further incubated for 6 h at 37°C, a significant increase in their LPA concentration was observed (figure 1 and 2: “after 6h” curves). This increase was observed with CM obtained from both 3T3F44A adipocytes (Figure 1) and human adipose tissue explants (Figure 2). Six hours incubation corresponded to the maximal increase (4 fold) (Figure 3). Above observations suggested that adipocytes were able to secreted or release a LPA-synthesizing activity (LPA-SA) in their incubation medium.

Figure 3. Kinetic of LPA-synthesizing activity.

Conditioned medium was collected and frozen after 24 h incubation with 3T3F442A adipocytes. LPA was quantified after 0 to 18h additional incubation at 37°C of defrosted conditioned medium. Data represent the mean ± SE of 3 separate experiments. ** corresponds to P<0.01 when comparing to time 0 (Student’s t test).

LPA-SA was completely inhibited by previous heating of CM at 90°C for 5 min (not shown). This suggested that LPA-SA likely resulted from a enzymatic- rather than from a chemically-catalyzed reaction. No LPA-SA was detected when HB-BSA (the buffer used to incubate adipocytes) alone was incubated in the same condition. This showed that LPA-SA was not brought by albumin. In addition, bacterial contamination had never been detected even after 48h incubation of CM at 37°C (not shown). These observations showed that LPA-SA could only be produced by adipocytes.

In order to determine whether LPA-SA was soluble or associated with cell particules (membranes, vesicules), CM were subjected to ultra-centrifugation (100.000 g, 60 min, 4°C). The totality of LPA-SA remained in a supernatant after ultracentrifugation (not shown), strongly suggesting that LPA-SA was a soluble enzyme-activity. Above results suggested that LPA-SA was resulting from a soluble enzyme-activity secreted or released by adipocytes.

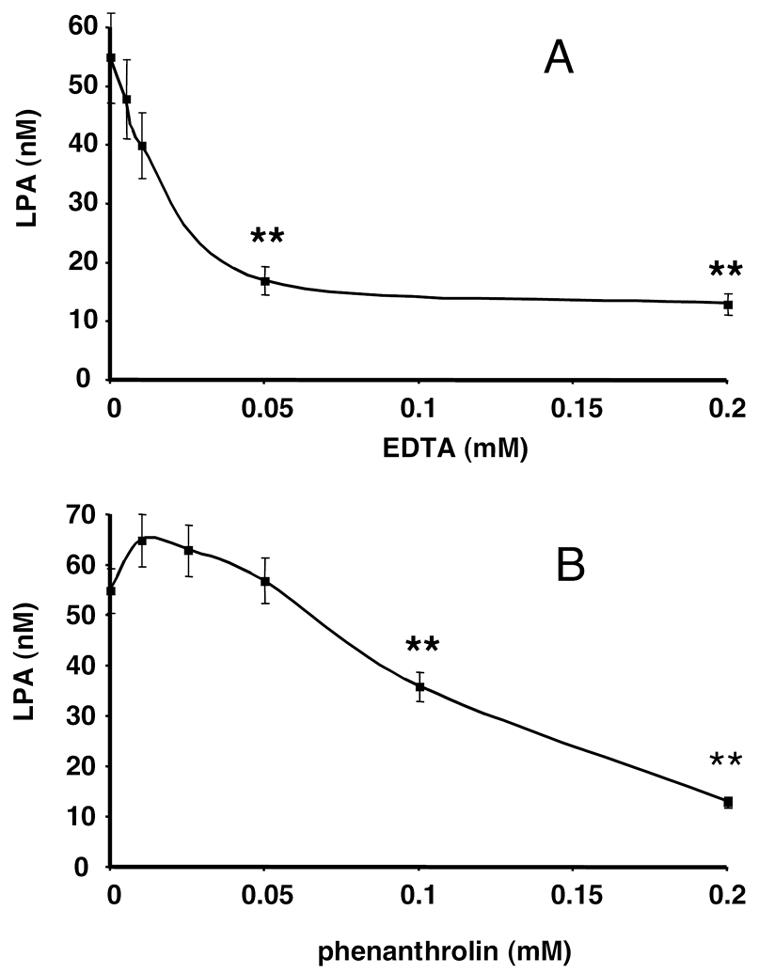

2/ LPA-SA requires divalent cations

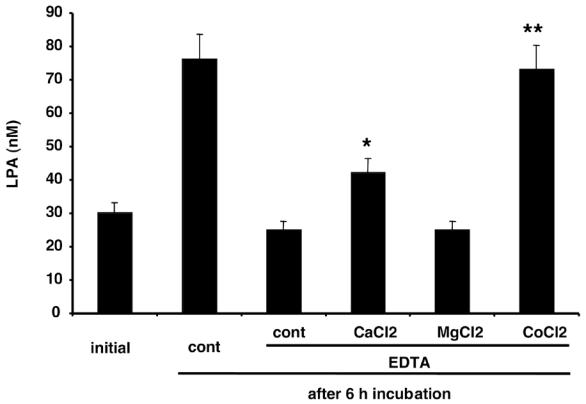

In order to better characterize LPA-SA, the influence of ion chelators and divalent-ions was tested. EDTA and phenanthroline both inhibited LPA-SA present in 3T3F442A adipocyte incubation medium, with IC50 of 0,02 and 0,09 mM respectively (Figure 4A and 4B). The inhibitory effect of 0,05 mM EDTA was completely reversed by 5 mM CoCl2, partially reverted by 5 mM CaCl2, and not affected by 5 mM MgCl2 (Figure 5). These results showed that LPA-SA required divalent-ions, with a preference for Co++ ions. Similar metal ion preference was described for a lyso-phospholipase D (lyso-PLD) catalyzing hydrolysis of lysophospholipids into LPA in rat plasma (6,23). This resemblance suggested that LPA-SA could correspond to a lysophospholipase D (lysoPLD).

Figure 4. Dose-dependent inhibition of LPA-SA by EDTA and phenanthrolin.

Conditioned medium was collected and frozen after 24 h incubation with 3T3F442A adipocytes. LPA was quantified after 6 h additional incubation at 37°C of defrosted conditioned medium in the presence of increasing concentrations of EDTA (A) or phenanthrolin (B). Data represent the mean ± SE of 3 separate experiments. ** corresponds to P<0.01 (Student’s t test) when comparing to control values without EDTA (A) or without phenanthrolin (B).

Figure 5. Reversion of EDTA effect on LPA-SA by CaCl2 and CoCl2.

Conditioned medium was collected and frozen after 24 h incubation with 3T3F442A adipocytes. LPA was quantified either immediatly after defrosting (Initial) or 6h after (after 6h) furtherincubation at 37°C in the absence (cont, EDTA) or in the presence of 0.2 mM EDTA ± 5 mM of calcium chloride (CaCl2), magnesium chloride (MgCl2), or cobalt chloride (CoCl2). Data represent the mean ± SE of 3 separate experiments. * corresponds to P<0.05 and ** corresponds to P<0.001 when comparing to cont EDTA (Student’s t test).

3/ Presence of lysophosphatidylcholine in adipocyte CM

If LPA-SA was a lyso-PLD, the presence of PLD-sensitive LPA precursors (other lysophospholipids) in adipocyte CM was required. To examine that point, adipocyte CM was treated with a bacterial PLD (from Streptomyces chromofuscus, Sigma) for 45 min and LPA was quantified. The initial concentration of LPA (26 ± 3 nM, n=3) was increased to 299 ± 25 nM (n=3) by treatment with bacterial PLD. This indicated the presence of PLD-sensitive LPA precursors in adipocyte CM. Conversely, treatment with pancreatic phospholipase A2 (potentially able to lead to the formation of LPA by deacylation of phosphatidic acid), did not modify LPA concentration (26 ± 3 nM vs 27 ± 3 nM).

Among lysophospholipids, lysophosphatidylcholine is usually the most abundant. Phospholipids co-migrating with LPC were purified from 1 ml adipocyte CM by preparative thin layer chromatography, solubilized in 1ml HB-BSA, and treated with bacterial PLD before quantification of LPA. This led to a concentration of LPA of 323 ± 12 nM LPA (n=3). This concentration was very close to what was obtained after treatment of whole CM with bacterial PLD: 299 ± 25 nM.

Above results showed that, in addition to LPA, adipocyte CM also contained other lysophospholipids (mainly lysophosphatidylcholine) constituting potential substrates for a lyso-PLD. Results also showed that adipocyte CM did not contain detectable PLA2-sensitive LPA precursors, therefore excluding that LPA-SA could be a PLA2.

4/ LPA-SA behaves like a lysophospholipase D

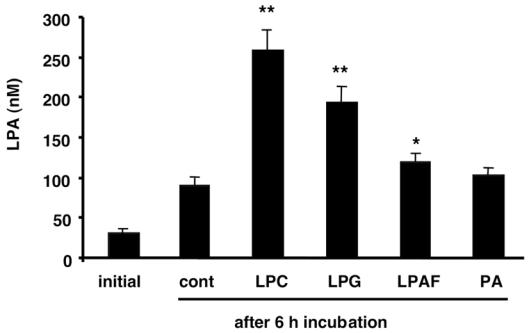

If LPA-SA was a lyso-PLD, addition of exogenous lysophospholipids in adipocyte CM should increase LPA concentration in CM. As shown in Figure 6, addition of exogenous (2 μM final concentration) oleoyl-LPC, oleoyl-LPG, or palmitoyl-LPAF, significantly increased the amount of LPA generated by 6 h incubation at 37°C of adipocyte CM. Conversely, no increase was observed by addition of exogenous dioleoyl-PA (Figure 6). In parallel, no LPA was detected when LPC, LPG, or LPAF were incubated for 6 h at 37°C in HB-BSA alone (not shown). Above results showed that adipocyte CM contained a lyso-PLD, and did not contain detectable PLA2 activity.

Figure 6. Presence of a lysophospholipase D activity in adipocyte conditioned medium.

Conditioned medium was collected and frozen after 24 h incubation with 3T3F442A adipocytes. LPA was quantified either immediately after defrosting (Initial) or 6h after (after 6h) further incubation at 37°C in the absence (cont) or the presence of 2 μM oleoyl-lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), or 2 μM oleoyllysophosphatidylglycerol (LPG), or 2 μM palmitoyl-lyso-platelet activating factor (LPAF), or 2 μM dioleoyl-phosphatidic acid (PA). Data represent the mean ± SE of 3 separate experiments. * corresponds to P<0.05 and ** corresponds to P<0.001 when compared to cont (Student’s t test).

As shown in Figure 6, the order of potency of conversion of the different lysophospholipids into LPA was: LPC > LPG > LPAF, showing that LPC was the best substrate for adipocyte lyso-PLD activity.

In order to determine the substrate specificity of adipocyte lyso-PLD, different LPC species were added in adipocyte CM (2 μM final concentration) and the amount of LPA generated after 6 h incubation was determined. The rate of conversion of palmitoyl-LPC, stearoyl-LPC, oleoyl-LPC, linoleoyl-LPC, and arachidonoyl-LPC into LPA were 6.3±0.7 %, 2.9±0.2 %, 4.9±0.5 %, 5.2±0.3 %, and 4.0±0.7 % (n=3) respectively. These date revealed that, except stearoyl-LPC which exhibited a slightly lower conversion, the other LPC substrates exhibited equivalent conversion into LPA, suggesting that adipocyte lyso-PLD did not exhibit substantial substrate specificity.

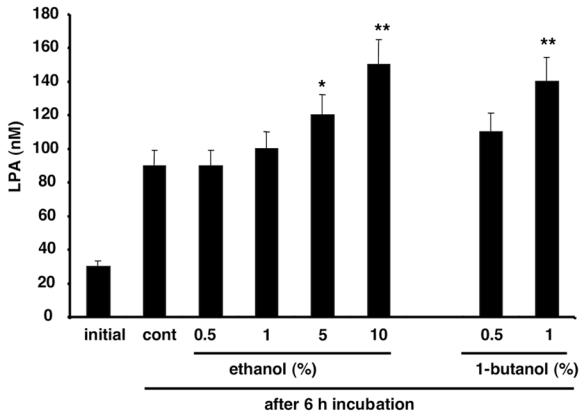

5/ Adipocyte lyso-PLD-activity does not result from a classical PLD

Some phospholipase D such as the PLD1 and PLD2 are characterized by their ability to catalyze, in the presence of primary alcohol, a transphosphatidylation reaction producing phosphatidylacohol instead of phosphatidic acid (24). If adipocyte lyso-PLD activity was due to the action of PLD1 or PLD2, it should be blocked by primary alcohols. As shown in Figure 7, ethanol (from 0.5 to 10%) did not inhibit, but rather increase (at 5 and 10%) adipocyte LPA-SA. Similar increase was observed with 0.5 and 1 % 1-butanol (Figure 7). Above results showed that PLD1 or PLD2 could not be responsible for adipocyte LPA-SA.

Figure 7. Influence of primary alcohols on adipocyte LPA-SA.

Conditioned medium was collected and frozen after 24 h incubation with 3T3F442A adipocytes. LPA was quantified either immediatly after defrosting (Initial) or 6h after (after 6h) further incubation at 37°C in the absence (cont) or in the presence of 0.5 to 10 % ethanol, or in the presence of 0.5 and 1% 1-butanol. Data represent the mean ± SE of 3 separate experiments. * corresponds to P<0.05 and ** corresponds to P<0.001 when compared to cont (Student’s t test).

6/ Differentiation-dependent regulation of lyso-PLD activity

Our laboratory has previously reported that extra-cellular production of LPA by adipocytes was increased after stimulation of α2-adrenergic receptors (17). We found that α2-adrenergic receptor stimulation did not influence lyso-PLD secretion nor production of lyso-PC by adipocytes (not shown), showing that α2-adrenergic-dependent regulation of extra-cellular production of LPA is likely mediated by another pathway which remains to be clarified.

In order to determine the existence of possible regulations of adipocyte lyso-PLD, its activity was measured during the course of adipocyte differentiation. For that purpose, confluent 3T3F442A undifferentiated preadipocytes were grown in a standardized differentiating medium (see Methods). Based upon analysis of specific markers (expression of the adipocyte-lipid binding protein mRNA, accumulation of triglycerides), adipocyte differentiation occurs between 2 and 5 days after confluence (25). Confluent preadipocytes and adipocytes (day 7 after confluence) were incubated in HB-BSA for 7 hours. LPA present in the conditioned medium was quantified either directly (this corresponded to the basal extra-cellular production of LPA by the cells), or after 6 hours further incubation at 37°C (this corresponds to the secretion of lyso-PLD), or after 45 min further incubation at 37°C in the presence of bacterial PLD (this corresponded to the production of LPC). Preadipocytes produced significantly less LPA (3.6 fold) and les lyso-PLD activity (6 fold) than adipocytes (Table 1). In parallel, no major alteration in lyso-PC production was observed between preadipocytes and adipocytes (Table 1). These results suggested the existence of a differentiation-dependent regulation of lyso-PLD activity which could account for a differentiation-dependent regulation of extracellular production of LPA.

Table 1.

Influence of adipocyte differentiation of production of LPA, LPA-SA and lyso-PC.

|

LPA (pmoles/mg of cell protein) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 3T3F442A cells | initial | after 6h | + PLD |

| preadipocytes | 6 ± 2 | 21 ± 3 | 814 ± 150 |

| adipocytes | 22 ± 3** | 126 ± 12** | 1129 ± 122 |

Confluent 3T3F442A preadipocytes were grown for 7 days in a standardized differentiating medium (see Methods) in order to obtain adipocytes. Conditioned media were collected and frozen after 7 h incubation of preadipocytes or adipocytes in HB-BSA. LPA was quantified either immediately after defrosting (Initial), or 6h after (after 6h) further incubation à 37°C, or after 45 min additional incubation at 37°C in the presence of 1U/ml bacterial PLD (+ PLD). Data represent the mean ± SE of 3 separate experiments.

corresponds to P<0.01 when comparing preadipocytes and adipocytes (Student’s t test).

Discussion

We previously demonstrated that adipocytes are able to produce LPA in their culture medium (17), however the metabolic origin of this extra-cellular production was not clarified.

In the present study, we demonstrate that, in parallel to LPA, adipocyte is also able to secrete a LPA-synthesizing activity (LPA-SA). Biochemical analysis strongly suggests that LPA-SA corresponds to a soluble lyso-phospholipase D (lyso-PLD) catalyzing transformation of LPC into LPA.

The hypothesis that LPA-SA could indeed correspond to a lyso-PLD is supported by several observations. First, LPA-SA exhibits similar sensitivity to the the ion-chelators (EDTA and phenanthrolin) and similar sensitivity to cobalt ion, than a lyso-PLD activity previously described in rat plasma (23). Second, adipocyte CM is able to transform exogenously added lysophospholipids into LPA, a reaction which can only be achieved by a lyso-PLD. Based on our results it appeared that the main substrat of adipocyte lyso-PLD is LPC since it is the main PLD-transformable LPA-precursors (mainly PLC) present in adipocyte CM. By using various exogenous lysophospholipids, we also found that LPC appears as the best substrate of adipocyte lyso-PLD as compared to LPG and LPAF. In addition, by using various LPC species we found that adipocyte lyso-PC does not exhibit substantial substrate specificity regarding the nature of the fatty acid composing its substrate. In that respect, adipocyte lyso-PLD appears to be different from the lyso-PLD previously described in rat plasma and which was demonstrated to hydrolyze polyinsaturated-LPC preferentially to the saturated-LPCs (6,26).

In platelets and ovarian cancer cells LPA synthesis has been proposed to result from deacylation of phosphatidic acid by a phospholipase A2-activity (3,5,18). In adipocyte CM, we could not detect any transformation of phosphatidic acid into LPA, showing that phospholipase A2-activity could not account for LPA-SA. In addition, treatment of adipocyte CM with pancreatic phospholipase A2 did not increase LPA concentration, suggesting that PA was undetectable in adipocyte CM. Therefore, the direct involvement of phospholipase A2 in LPA-SA could reasonably be excluded. Nevertheless, phospholipase A2 very likely plays an indirect role by providing the substrate of the lyso-PLD, lysophosphatidylcholine resulting from hydrolysis of phosphatidylcholine.

Because of its relatively high polarity, it is unlikely that LPA could easily diffuse through phospholipid membranes. Therefore, when present extra-cellularly, LPA would result from secreted or ectopic enzyme(s), rather than from intracellular enzyme(s). This hypothesis is in agreement with previous report showing that exogenous bacterial PLD exhibiting lyso-PLD activity can produce LPA in the outer membrane leaflet of intact cells (7). The fact that adipocyte lyso-PLD was found in CM after separation from the cells suggests that this enzyme could be secreted or released from adipocytes. This hypothesis is reinforced by the fact that adipocyte lyso-PLD activity was found to be soluble and not associated with a particulate fraction.

Although the precise the mechanisms of its secretion/release remain to be established, adipocyte lyso-PLD is, to our knowledge, the first extracellular lyso-PLD of known cellular origin in mammals. Tokomura et al. have reported the existence of a lyso-PLD activity in rat plasma (6) as well as in human follicular fluids (8). Whereas the involvement of this lyso-PLD activity in LPA production has been demonstrated, the structure of the enzyme, as well as its cellular origin, remains completely unknown. Therefore, the discovery of an adipocyte lyso-PLD activity gives a unique opportunity to purify and clone the enzyme. Interestingly, our data show that lyso-PLD activity is up-regulated during adipocyte differentiation. It is therefore likely that adipocyte lyso-PLD gene belong to a set of gene positively regulated during adipocyte differentiation, and this could help for its identification.

As we previously showed, LPA produced by adipocytes is able to activate the growth of the adipocyte precursors (preadipocytes) (17), one of the key events of adipose tissue development: adipogenesis. Preadipocytes being located in the close vicinity of adipocytes in the adipose tissue, adipocyte production of LPA could play an important role in paracrine control of adipose tissue development. In order to control this paracrine function of LPA, it is required either to target LPA-receptors (EDG-2 receptors) present in preadipocytes (25), or to act on adipocyte-LPA synthesis. Consequently, adipocyte lyso-PLD could represent an interesting target to control adipose tissue development.

Abbreviations

- LPA

lysophosphatidic acid

- CM

conditioned medium

- LPA-SA

lysophosphatidic acid-synthesizing activity

- PLD

phospholipase D

- PLA2

phospholipase A2

- PC

phosphatidylcholine

- LPC

lysophosphatidylcholine

- PA

phosphatidic acid

- LPG

lysophosphatidylglycerol

- LPAF

lyso-platelet activated factor

- LPAAT

lysophosphatidic acid acyltransferase

- MeOH

methanol

- CHCl3

chloroform

Footnotes

Contributors: This work was supported by grants from the Institut Nationale de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, the Institut de Recherche Servier, the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (#5381) and the Laboratoires Clarins.

References

- 1.Goetzl E, An S. Diversity of cellular receptors and functions for the lysophospholipid growth factors lysophosphatidic acid and sphingosin 1-phosphate. FASEB J. 1998;12:1589–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chun J, Contos JJ, Munroe D. A growing family of receptor genes for lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) and other lysophospholipids (LPs) Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1999;30:213–242. doi: 10.1007/BF02738068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCrea J, Robinson P, Gerrard J. Mepacrine (quinacrine) inhibition of thrombin-induced platelet responses can be overcome by lysophosphatidic acid. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985;842:189–194. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(85)90202-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerrard JM, Robinson P. Identification of the molecular species of lysophosphatidic acid produced when platelets are stimulated by thrombin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;1001:282–285. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(89)90112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fourcade O, Simon MF, Viodé C, Rugani N, Leballe F, Ragab A, Fournié B, Sarda L, Chap H. Secretory phospholipase A2 generates the novel lipid mediator lysophosphatidic acid in membrane microvesicles shed from activated cells. Cell. 1995;80:919–927. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90295-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tokumura A, Harada K, Fukuzawa K, Tsukatani H. Involvement of lysophospholipase D in the production of lysophosphatidic acid in rat plasma. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;875:31–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Dijk M, Postma F, Hilkmann H, Jalink K, Blitterswijk Wv, Moolenaar W. Exogenous phospholipase D generates lysophosphatidic acid and activates Ras, Rho and Ca2+ signaling pathways. Curr Biol. 1998;8:386–392. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70157-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tokomura A, Miyake M, Nishioka Y, Yamano S, Aono T, Fukuzawa K. Production of lysophosphatidic acids by lysophospholipase D in human follicular fluids of in vitro fertilization patients. Biol Reprod. 1999;61:195–199. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod61.1.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tigyi G, Miledi R. Lysophosphatidates bound to serum albumin activate membrane currents in Xenopus oocytes and neurite retraction in PC12 pheochomocytoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:21360–21367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eichholtz T, Jalink K, Fahrenfort I, Moolenaar WH. The bioactive phospholipid lysophosphatidic acid is released from activated platelets. Biochem J. 1993;291:677–680. doi: 10.1042/bj2910677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tokumura A, Iimori M, Nishioka Y, Kitahara M, Sakashita M, Tanaka S. Lysophosphatidic acids induce proliferation of cultured vascular smooth muscles cells from rat aorta. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:C204–C210. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.1.C204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sasagawa T, Suzuki K, Shiota T, Kondo T, Okita M. The significance of plasma lysophospholipids in patients with renal failure on hemodialysis. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol. 1998;44:809–18. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.44.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaits F, Fourcade O, Gueguen LBFG, Gaigé B, Gassama-Diagne A, Fauvel J, Salles J-P, Mauco G, Simon M-F, Chap H. Lysophosphatidic acid as a phospholipid mediator: pathways of synthesis. FEBS Lett. 1997;410:54–58. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00411-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu Y, Gaudette D, Boynton J, Frankel A, Fang X, Sharma A, Hurteau J, Casey G, Goodbody A, Mellors A, Holub B, Mills G. Characterization of an ovarian cancer activating factor in ascites from ovarian cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 1995;1:1223–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Westermann A, Havik E, Postma F, Beijnen J, Dalesio O, Moolenar M, Rodenhuis S. Malignant effusions contain lysophosphatidic acid (LPA)-like activity. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:437–442. doi: 10.1023/a:1008217129273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liliom K, Guan Z, Tseng JL, Desiderio DM, Tigyi G, Watsky MA. Growth factor-like phospholipids generated after corneal injury. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:C1065–C1074. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.4.C1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valet P, Pages C, Jeanneton O, Daviaud D, Barbe P, Record M, Saulnier-Blache JS, Lafontan M. Alpha2-adrenergic receptor-mediated release of lysophosphatidic acid by adipocytes. A paracrine signal for preadipocyte growth. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1431–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen Z, Belinson J, Morton R, Yan X. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate stimulates lysophosphatidic acid secretion from ovarian and cervical cancer cells but not from breast or leukemia cells. Gynecol Oncol. 1998;71:364–368. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1998.5193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bétuing S, Valet P, Lapalu S, Peyroulan D, Hickson G, Daviaud D, Lafontan M, Saulnier-Blache JS. Functional consequences of constitutively active α2A-adrenergic receptor expression in 3T3F442A preadipocytes and adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Com. 1997;235:765–773. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Viguerie-Bacands N, Saulnier-Blache J, Dandine M, Dauzats M, Daviaud D, Langin D. Increase in Uncoupling Protein-2 mRNA expression by BRL49653 and bromopalmitate in human adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Com. 1999;256:138–141. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saulnier-Blache JS, Girard A, Simon MF, Lafontan M, Valet P. A simple and highly sensitive radioenzymatic assay for lysophosphatidic acid quantification. J Lipid Res. 2000;41:1947–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Böttcher C, Gent CV, Priest C. A rapid and sensitive sub microphosphorus determination. An Chim Acta. 1961;24:203–204. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tokumura A, Miyabe M, Yoshimoto O, Shimizu M, Fukuzawa K. Metal-ion stimulation and inhibition of lysophospholipase D which generates bioactive lysophosphatidic acid in rat plasma. Lipids. 1998;33:1009–1015. doi: 10.1007/s11745-998-0299-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liskovitch M, Czarny M, Fiucci G, Tang X. Phospholipase D: molecular and cell biology of a novel gene family. Biochem J. 2000;345:401–415. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pagès C, Daviaud D, An S, Krief S, Lafontan M, Valet P, Saulnier-Blache J. Endothelial Differentiation Gene-2 receptor is involved in lysophosphatidic acid-dependent control of 3T3F442A preadipocyte proliferation and spreading. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:11599–11605. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010111200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tokumura A, Fujimoto H, Yoshimoto O, Nishioka Y, Miyake M, Fukuzawa K. Production of lysophosphatidic acid by lysophospholipase D in incubated plasma of spontaneously hypertensive rats and Wistar Kyoto rats. Life Sci. 1999;65:245–53. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00243-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]