Abstract

Recent research has shown the essential role of reduced blood flow and free radical formation in the cochlea in noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL). The amount, distribution, and time course of free radical formation have been defined, including a clinically significant late formation 7–10 days following noise exposure, and one mechanism underlying noise-induced reduction in cochlear blood flow has finally been identified. These new insights have led to the formulation of new hypotheses regarding the molecular mechanisms of NIHL; and, from these, we have identified interventions that prevent NIHL, even with treatment onset delayed up to 3 days post-noise. It is essential to now assess the additive effects of agents intervening at different points in the cell death pathway to optimize treatment efficacy. Finding safe and effective interventions that attenuate NIHL will provide a compelling scientific rationale to justify human trials to eliminate this single major cause of acquired hearing loss.

Keywords: Noise, Hearing Loss, Antioxidant, Cochlea, Cell Death

Introduction

The significant clinical issue presented by noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL) has driven an effort to understand the underlying molecular and biochemical mechanisms of cell death in the cochlea, and to develop interventions to reduce or prevent NIHL. One major advance came with the knowledge that intense metabolic activity alters cellular redox state and drives the formation of free radicals (for reviews, see Halliwell and Gutteridge, 1998; Evans and Halliwell, 1999). Free radicals, which contain one or more unpaired electrons (see Halliwell and Gutteridge, 1998), include reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS). As a group, ROS/RNS are short-lived, unstable, highly reactive clusters of atoms. They are essential for cellular life processes; however, in excess they damage cellular lipids, proteins, and DNA, and upregulate apoptotic pathways (for a helpful summary of oxidative mechanisms, see Campbell, 2003). Better understanding of these key molecules have helped define interventions that significantly reduce NIHL and other environmentally-mediated hearing impairments (such as aminoglycoside antibiotics and chemotherapeutics). In this review, we describe mechanisms of NIHL and interventions that reduce this sensory deficit. Together, these observations dictate new strategies of translational research and provide promise for direct therapeutic treatment of the inner ear.

Noise-Induced ROS

Until a decade ago, the prevailing view of NIHL was that it was caused by mechanical destruction of the delicate membranes of the hair cells and supporting structures of the organ of Corti (Spoendlin, 1971; Hunter-Duvar and Elliott, 1972, 1973; Hamernik and Henderson, 1974; Hamernik et al., 1974; Hunter-Duvar and Bredberg, 1974; Hawkins et al., 1976; Mulroy et al., 1998), with perhaps some effect of intense noise on blood flow to the inner ear (Perlman and Kimura, 1962; Hawkins, 1971; Hawkins et al., 1972; Lipscomb and Roettger, 1973; Santi and Duvall, 1978; Axelsson and Vertes, 1981; Axelsson and Dengerink, 1987; Duvall and Robinson, 1987; Scheibe et al., 1993; Miller et al., 1996). We now know another significant factor is intense metabolic activity, which increases mitochondrial free radical formation. That intense metabolic activity may contribute to noise-induced inner ear pathology was initially proposed by Lim and Melnick (1971). This hypothesis gained credibility with demonstration of noise-induced free radical formation in the inner ear tissues by Yamane et al. (1995), and subsequent corroboration of this finding by Ohlemiller, McFadden, and their colleagues (Ohlemiller et al., 1999a; 1999b; 2000; McFadden et al., 2001).

Henderson et al. (2006) recently reviewed evidence that noise exposure drives mitochondrial activity and free radical production, reduces cochlear blood flow, causes excitotoxic neural swelling, and induces both necrotic and apoptotic cell death in the organ of Corti. Here, we review data on free radical formation in the inner ear during noise exposure, and describe attenuation of NIHL via pretreatment with agents that up-regulate endogenous antioxidants or exogenous antioxidants. In general, protection is limited to reduction of permanent threshold shift (PTS), with little or no reduction in temporary threshold shift (TTS). We then describe recent evidence for delayed free radical formation, peaking 7–10 days following noise exposure, and the finding that free radical scavengers administered as long as 3 days post-noise attenuate free radical formation, reduce sensory cell death, and reduce NIHL.

Noise-induced free radical formation in the cochlea

Ohlemiller et al. (1999b) adapted to the cochlea a technique for probing hydroxyl (OH) radicals and reported a nearly 4-fold increase in OH within 1–2 hours of noise exposure. DNA is particularly susceptible to damage via OH radicals (see Halliwell and Gutteridge, 1998 for review). Yamane et al. (1995) localized this noise-induced increase in free radicals to stria vascularis (marginal cells); ROS formation is also significant in outer hair cells (Nicotera et al., 1999; Henderson et al., 2006).

Lipids are one of the major constituents of biological membranes; lipid peroxidation involves oxidative lipid deterioration and damages proteins embedded in cell membranes. Lipid peroxidation is readily initiated by OH radicals, and a single initiating reaction can generate multiple peroxide radicals via a chain reaction. To measure endogenous lipid peroxidation products in the cochlea after noise, Ohinata et al. (2000a) evaluated F2 isoprostanes [prostaglandin-like compounds generated by free-radical catalyzed peroxidation of arachidonic acid, and reliably produced during oxidant stress (Morrow et al., 1990; Longmire et al., 1994; Roberts and Morrow, 1994)]. Post-noise immunolabeling for 8-isoprostane was heaviest in stria vascularis (lateral wall), greater in outer hair cells than in inner hair cells, and evident in spiral ganglion and supporting cells (Ohinata et al., 2000a). Labeling was turn dependant, with the most immunolabeling observed in the regions of the cochlea most damaged by the noise. The increase in the stria well supported the previous finding by Yamane et al. (1995); hair cell labeling was also consistent with that described previously (Nicotera et al., 1999; Henderson et al., 2006). Labeling of spiral ganglion neurons was consistent with neuronal death triggered by oxidative stress in other neural systems (for review, see Mattson, 2000). Taken together, these data dramatically demonstrate the potentially powerful role of oxidative free radicals in NIHL.

Endogenous antioxidant defense against NIHL

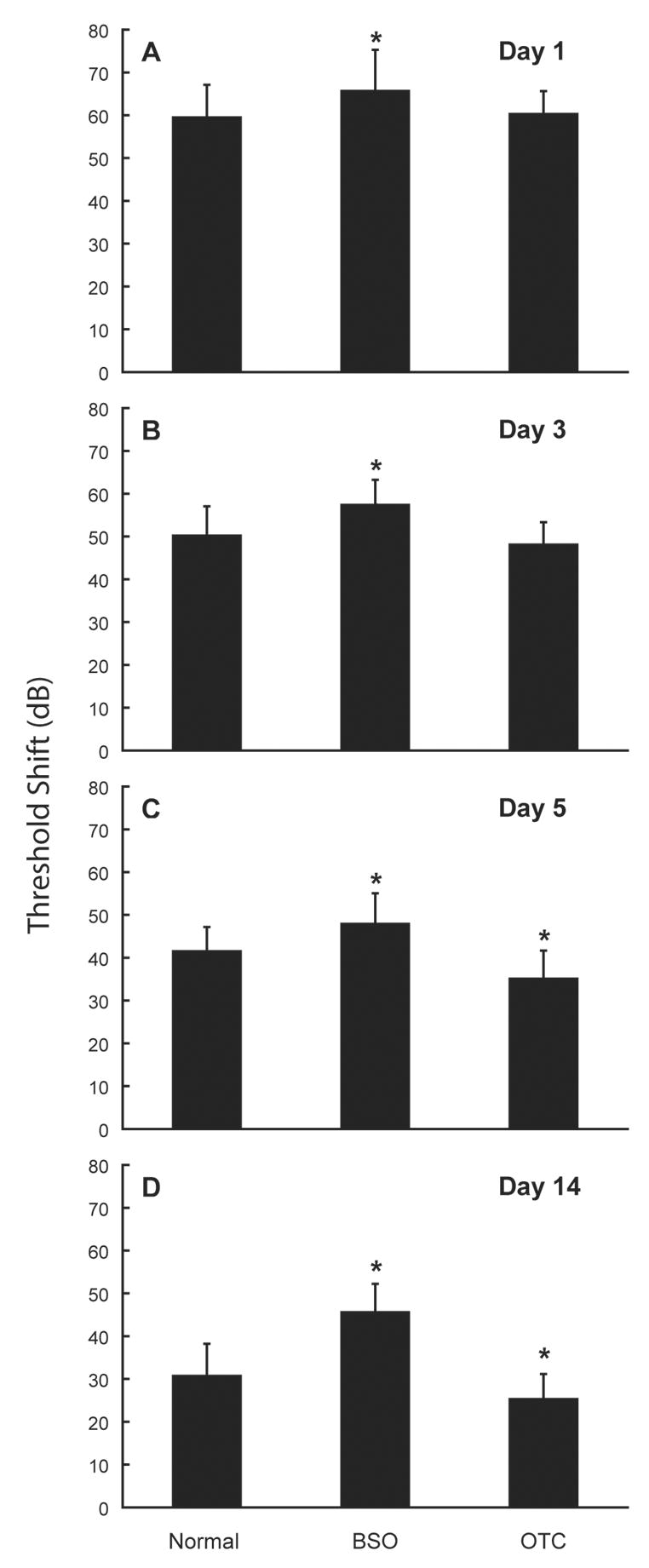

Early reports of noise-induced free radical formation in the cochlea led to the hypothesis that endogenous antioxidant agents could modulate susceptibility to NIHL. Endogenous defense could be mediated by glutathione (GSH), the primary cellular antioxidant system of the body preferentially, but not exclusively, distributed in the stria vascularis, spiral ligament, and vestibular endorgans (Usami et al., 1996). If ROS are involved in NIHL, then animals with reduced GSH production should be more susceptible to NIHL and inner ear pathology, and upregulation of GSH should reduce noise trauma. To test that hypothesis, guinea pigs were treated with L-buthionine-[S, R]-sulfoximine (BSO), which inhibits endogenous GSH synthesis. This treatment rendered them more susceptible to noise-induced sensory cell death and NIHL (Yamasoba et al., 1998). In contrast, animals treated with 2-oxothiazolidine-4-carboxylate (OTC), a pro-cysteine drug which promotes rapid restoration of GSH, were less susceptible to noise-induced trauma (Yamasoba et al., 1998). Protective effects of OTC were evident as reductions in PTS, with no change in earlier hearing loss, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Status of the endogenous antioxidant glutathione (GSH) influences noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL). Treatment with L-buthionine-[S,R]-sulfoximine (BSO), which inhibits endogenous GSH synthesis, increases NIHL whereas 2-oxothiazolidine-4-carboxylate (OTC), a pro-cysteine drug which promotes rapid restoration of GSH, reduces NIHL. Threshold deficits are illustrated 1 day (A), 3 days (B), 5 days (C), and 14 days (D) following noise (average hearing loss at 12 kHz, mean ± SE); effects of OTC were time-dependant in that permanent threshold shift was reduced whereas initial temporary threshold deficits were unchanged (i.e., days 1–3). Noise exposure was a broadband noise presented at a level of 102-dB SPL for 3 hours per day for 5 consecutive days. Asterisks indicate statistically reliable differences relative to saline-treated control. Adapted from Yamasoba et al. (1998).

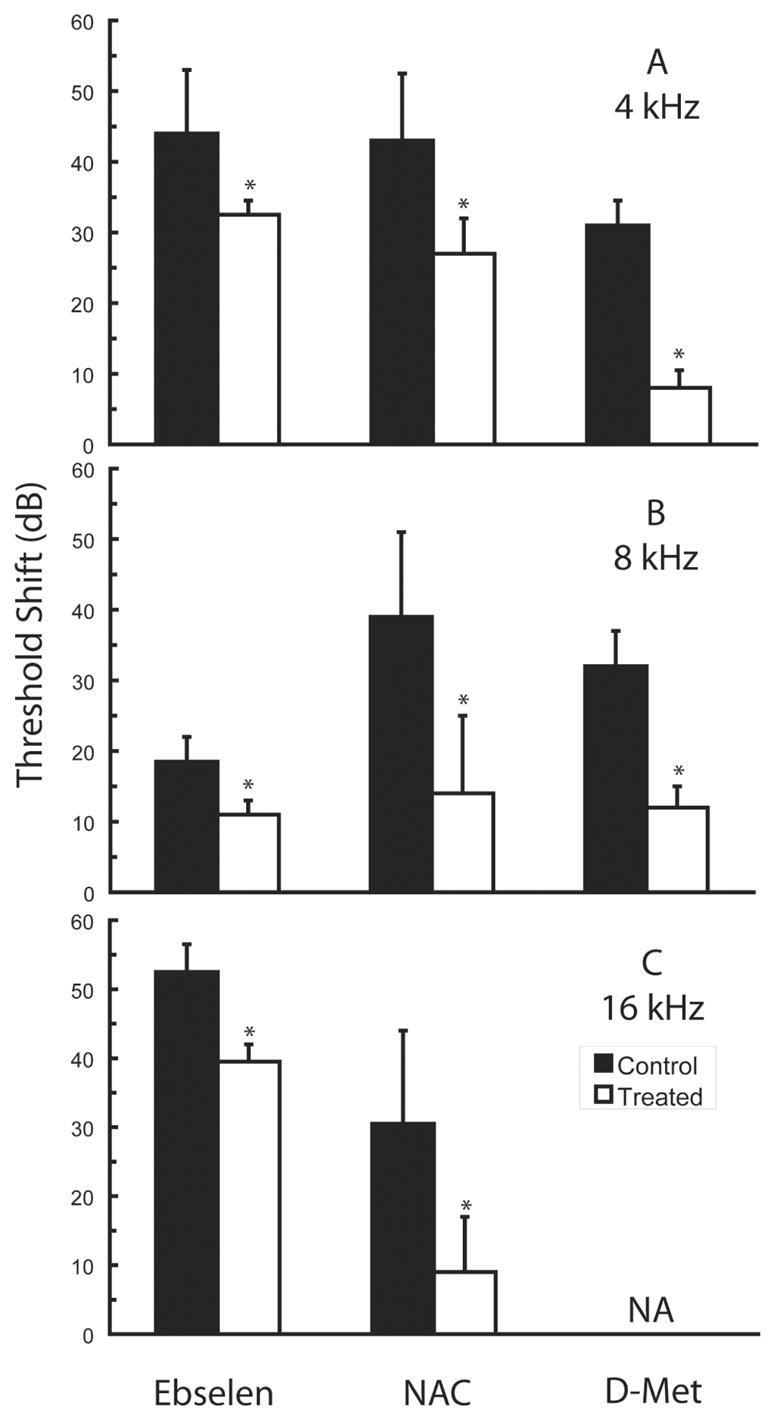

Multiple groups have pursued GSH-based therapeutic strategies in recent years. N-acetylcysteine (NAC), a glutathione precursor and ROS scavenger, has been effective in reducing PTS in noise-exposed guinea pigs (Ohinata et al., 2003; Duan et al., 2004) and chinchillas (delivered in combination with salicylate, see Kopke et al., 2000), with no effect on TTS in man (Kramer et al., 2006) or rodents (Kopke et al., 2000; Duan et al., 2004). Given that a major determinant of GSH level is bioavailable cysteine, and that cysteine can be derived from methionine, an alternative strategy has been pre-treatment with D-methionine. D-methionine reduces PTS but not TTS (Kopke et al., 2002). In contrast to NAC and D-methionine, pretreatment with ebselen [a glutathione-mimetic which reduces hydroperoxide formation (Noguchi et al., 1992)] reduces both TTS and PTS (Pourbakht and Yamasoba, 2003; Lynch et al., 2004; Lynch and Kil, 2005; Yamasoba et al., 2005). Although the utility of comparisons across investigations is compromised by variation in dose schedule and duration, species, and noise exposure, agents that increase endogenous GSH clearly yield incomplete protection, as shown in Figure 2. Incomplete protection may be related to observations that many hydroxyl scavengers are only partially effective in inhibiting lipid peroxidation as they compete for OH in ‘free solution’ but do not cross the lipid membrane barriers to scavenge OH within the cells (for additional detail, see Halliwell and Gutteridge, 1998). Manipulation of endogenous GSH with the above agents also affects cisplatin-induced injury (Campbell et al., 1996; 1999; Hu et al., 1999; Rybak et al., 2000; Campbell et al., 2003), and aminoglycoside ototoxicity (Hoffman et al., 1988; Garetz et al., 1994a; 1994b; Lautermann and Schacht, 1996).

Figure 2.

Partial protection against permanent noise-induced threshold deficits can be achieved using glutathione (GSH) based strategies. The GSH peroxidase mimic 2-phenyl-1,2-benzisoselenazol-3(2H)-one (Ebselen) (adapted from Lynch et al., 2004), the GSH precursor N-acetylcysteine (NAC, adapted from Ohinata et al., 2003), and the cysteine precursor D-methionine (D-Met, adapted from Kopke et al., 2002) all provide partial protection. Data are either mean ± SD (NAC) or mean ± SE (D-Met), as plotted in the original publications. Permanent threshold deficits at 4 kHz (A), 8 kHz (B), and 16 kHz (C) were measured either 10 days (NAC) or 3 weeks (Ebselen, D-Met) post-noise. In the investigation performed by Lynch et al. (2004), rats (N=4 animals/group) were exposed to 113 dB SPL noise (4 kHz to 16 kHz) for 4 hours; rats were treated with 4 mg/kg ebselen p.o. BID one day pre- and one day post-noise, as well as one hour pre- and one hour post-noise on the day of exposure. In the investigation performed by Ohinata et al. (2003), guinea pigs (N=16 control animals, N=7 treated animals) were exposed to 115 dB SPL noise (octave band centered at 4 kHz) for 5 hours; guinea pigs were treated with a single dose of 500 mg/kg NAC i.p. 30 minutes pre-noise. In the investigation performed by Kopke et al. (2002), chinchillas (N=6 animals/group) were exposed to 105 dB SPL noise (octave band centered at 4 kHz) for 6 hours; chinchillas were treated with 200 mg/kg D-methionine i.p. BID beginning two days pre-noise and continuing two days post-noise, as well as one hour pre- and one hour post-noise on the day of exposure. Although the utility of comparisons across agents and investigations is compromised by variation in dose schedule and duration, species, and noise exposure, the data clearly illustrate that protection via glutathione-based strategies is typically incomplete. Asterisks indicate statistically reliable differences relative to saline-treated control animals tested in each investigation.

Subsequent corroboration of the importance of endogenous antioxidants has come from genetically manipulated mice in which endogenous antioxidant protection was reduced via deletion of copper-zinc super oxide dismutase (Sod1) (Ohlemiller et al., 1999a; McFadden et al., 2001) or glutathione peroxidase (Gpx1) (Ohlemiller et al., 2000). Overexpression of antioxidant enzymes, locally in the inner ear (Kawamoto et al., 2004) or systemically (Sha et al., 2001), reduces aminoglycoside-induced hearing loss; it is reasonable to predict that these manipulations would similarly reduce sensitivity to noise-induced deficits.

Enhancing antioxidant defense attenuates NIHL

Given that endogenous GSH importantly influences susceptibility to auditory trauma, administration of exogenous antioxidants has been widely proposed as a potential therapeutic intervention. That antioxidant agents effectively reduce sensory cell death and NIHL has now been well demonstrated in animal studies using a variety of antioxidant agents, such as GSH/glutathione monoethyl ester (GSHE) (Ohinata et al., 2000b; Kopke et al., 2002; Hight et al., 2003; Miller et al., 2003a), resveratrol (Seidman et al., 2003), allopurinol (Seidman et al., 1993; Cassandro et al., 2003), superoxide dismutase-polyethylene glycol (Seidman et al., 1993), U74389F (a lazaroid drug which inhibits lipid peroxidation and scavenges free radicals) (Quirk et al., 1994), and R-phenylisopropyladenosine (R-PIA) (Hu et al., 1997; Hight et al., 2003). Small protective effects of individual (or combined) dietary antioxidant nutrients are also well described for insults to the inner ear including noise, drugs, and age (Chole and Quick, 1976; Lohle, 1980, 1985; Romeo, 1985; Biesalski et al., 1990; Lopez-Gonzalez et al., 2000; Seidman, 2000; Bertolaso et al., 2001; Pasqualetti and Rijli, 2001; Teranishi et al., 2001; Rabinowitz et al., 2002; Hou et al., 2003; Derekoy et al., 2004; Kalkanis et al., 2004; Weijl et al., 2004; Ahn et al., 2005; McFadden et al., 2005; Yamashita et al., 2005a).

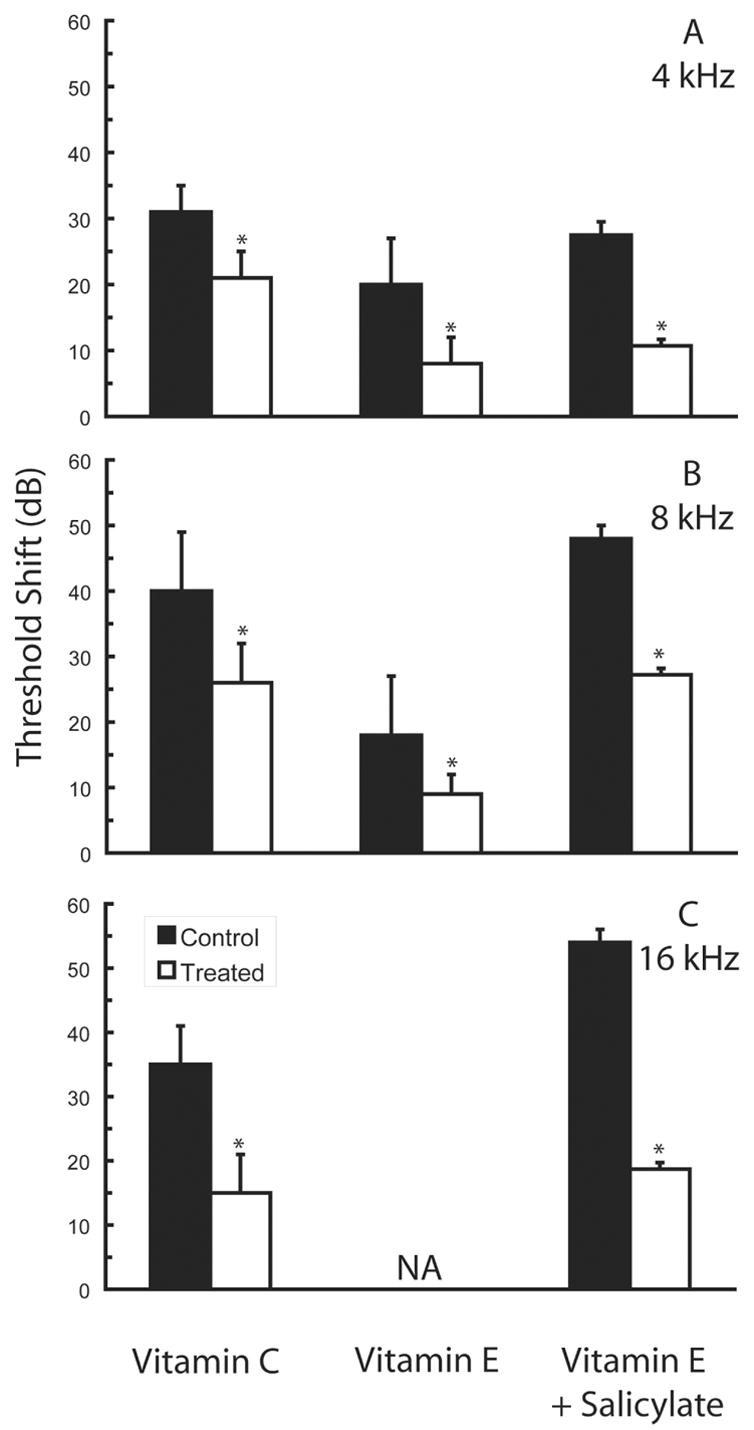

The finding that dietary supplements reduce NIHL is of particular interest given their easy over-the-counter accessibility; however, therapy with any single micronutrient may need to be initiated days to weeks in advance of noise exposure to obtain clinically meaningful results. Whereas a 35-day pre-treatment protocol significantly reduced NIHL (see Figure 3) and sensory cell death (see McFadden et al., 2005), vitamin C treatment initiated 48 hours prior to noise exposure failed to prevent noise-induced cell death (500 mg/kg ascorbic acid, i.p., 48 h, 24 h, and 5 min prior to noise exposure, Branis and Burda, 1988). Pre-treatment requirements may vary across micronutrients, as vitamin E reduced NIHL with treatment initiated 3 days pre-noise (Hou et al., 2003) (see Figure 3), and vitamin A reduced NIHL with treatment initiated two days pre-noise (Ahn et al., 2005). As with GSH-based strategies (i.e., figure 2), reduction of NIHL with dietary antioxidants has been incomplete (see Figure 3). While dietary treatments may need to be provided for some longer period of time pre-noise to be maximally effective, high-dose vitamin C did not completely prevent NIHL even with 35 days pre-treatment, and stable plasma and tissue levels of vitamin C are obtained (in humans) approximately 3 weeks after beginning dietary treatment (Levine et al., 1996). Taken together, these data suggest that dietary antioxidants may be more useful in combination than as single-agent therapeutics.

Figure 3.

Partial protection against permanent noise-induced threshold deficits can be achieved using dietary antioxidants. Agents evaluated to date include vitamin A (see Ahn et al., 2005 for click thresholds), vitamin C (adapted from McFadden et al., 2005), vitamin E (adapted from Hou et al., 2003), vitamin E plus salicylate (adapted from Yamashita et al., 2005a), and resveratrol (see Seidman et al., 2003 for data at 3, 6, 9, 12, and 18 kHz), which occurs naturally in red wine and grape skin. Data are either mean ± SD (vitamins A, E) or mean ± SE (vitamin C, vitamin E + salicylate), as plotted in the original publications. Permanent threshold deficits at 4 kHz (A), 8 kHz (B), and 16 kHz (C) shown here were measured either 8 days (vitamin E), 10 days (vitamin E plus salicylate), or 21 days (vitamin C) post-noise. In the investigation performed by McFadden et al. (2005), guinea pigs (N=8 animals/group) were exposed to 115 dB SPL noise (octave band centered at 4 kHz) for 6 hours; beginning 35 days pre-noise exposure, guinea pigs were fed a diet containing 500 mg per kg chow L--2-pascorbylolyphosphate (control diet) or 5,000 mg per kg chow L--2-pascorbylolyphosphate (vitamin C supplement). In the investigation performed by Hou et al. (2003), guinea pigs (N=8 animals/group) were exposed to 100 dB SPL noise (octave band centered at 4 kHz) for 8 hours per day for 3 days; guinea pigs were treated with 10 (not shown) or 50 mg/kg vitamin E (α-tocopherol) i.p. beginning three days pre-noise and continuing three days post-noise, as well as on the three days of exposure. In the investigation performed by Yamashita et al. (2005), guinea pigs (N=6 animals/group) were exposed to 120 dB SPL noise (octave band centered at 4 kHz) for 5 hours; guinea pigs were treated with 50 mg/kg vitamin E (trolox) i.p. and 75 mg/kg salicylate s.c. BID. Here we show data from animals in which treatment began 3 days prior to noise exposure and continued ten days post-noise. Although the utility of comparisons across agents and investigations is reduced by variation in dose schedule and duration, species, and noise exposure, the data clearly illustrate that protection via dietary antioxidants has been incomplete with all combinations tested to date. Asterisks indicate statistically reliable differences relative to saline-treated control animals tested in each investigation.

Free radical formation continues long after noise exposure

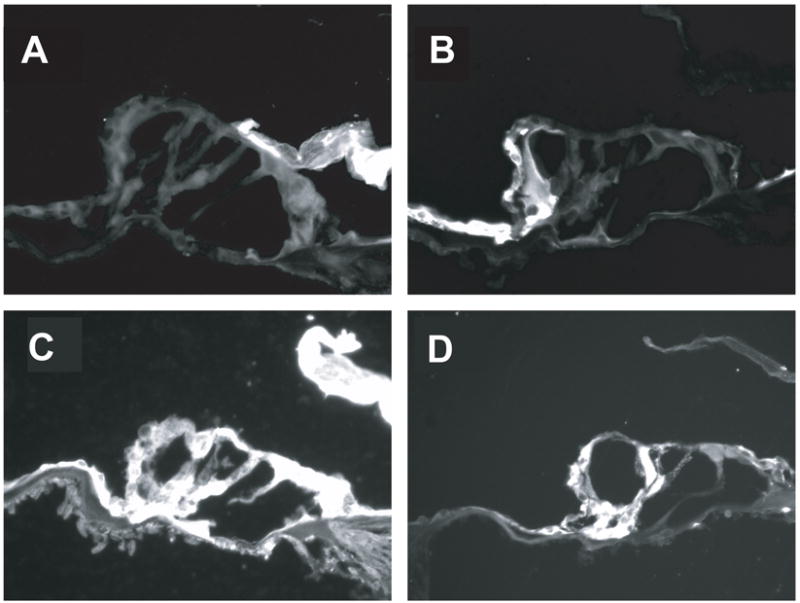

Ohlemiller et al. (1999b) were among the first to suggest noise-induced oxidative stress begins early and becomes substantial over time. Free radical insult that builds over time would potentially explain observations of hair cell death that accelerates with time after exposure for a period of up to 14 days (Bohne et al., 1999; Yamashita et al., 2004). Using 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) to mark ROS byproducts and nitryotyrosine (NT) to mark RNS byproducts, Yamashita et al. (2004) demonstrated peak ROS and RNS production occurs in cells in the organ of Corti 7–10 days following noise insult (see Figure 4). The progression of immunolabeling from the lateral wall and Claudius cells (on days 1–2) to the Deiter’s cells (day 3) and then the outer hair cell bodies (days 7–10, with some labeling in inner hair cells as well) suggests that permanent hearing loss and the final extent of hair cell loss may reflect termination of cell death pathways initiated by late-forming free radicals in the inner ear. These results suggest the possibility that delayed interventions may have clinical utility.

Figure 4.

Immunolabeling of byproducts of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) varies with time post time. Byproducts of 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE, panels A and C), used to mark ROS byproducts, and nitrotyrosine (NT, panels B and D), used to mark RNS byproducts is shown. Little or no labeling was evident in control animals not exposed to noise (panels A and B). Peak ROS and RNS production was observed in cells in the organ of Corti 7–10 days post-noise. Noise exposure was an octave band noise centered at 4 kHz and presented at a level of 120-dB SPL for 5 hours. Significant 4-HNE and NT expression was observed in the outer hair cell bodies, with some labeling in inner hair cells as well (panels C and D). Adapted from Yamashita et al. (2004); see also Miller et al. (2006b).

Efficacy of delayed treatment with antioxidant agents

Initial studies assessing the effectiveness of post-exposure antioxidant treatment had mostly disappointing results. For example, Kopke et al. (2000) examined the effect of NAC and salicylate administered immediately following noise exposure and reported a small but significant reduction in NIHL, but no reduction in the sensory cell loss. More recent investigations have provided exciting new evidence for efficacy of post-noise treatment however. We evaluated the effects of salicylate and vitamin E (ROS and RNS scavengers, respectively) on NIHL when administered beginning prior to exposure, or beginning on days 1, 3 or 5 post-noise (Yamashita et al., 2005a). While pre-treatment was the most effective in preventing NIHL and sensory cell death, efficacy of treatment initiated 24 hours following exposure was not statistically different from that of pre-treatment. Clearly of clinical benefit, treatment initiated 3 days post-exposure also reduced NIHL and sensory cell death relative to untreated controls. Treatment delayed 5 days relative to noise insult was not effective, suggesting the therapeutic “window of opportunity” for successful antioxidant-based intervention against NIHL occurs within the first three days post-noise (see Figure 5). Post-treatment with free-radical scavengers initiated at days 1 or 3 post-noise also attenuated the late formation of ROS and RNS byproducts, confirming a key role of late-forming free radicals in the development of permanent noise-induced deficits (Yamashita et al., 2005a). Although post-treatment with vitamin E and salicylate was more effective than treatment with NAC and salicylate, conclusions about the relative efficacy of these agents are compromised by variation in dose schedule and duration, species of the subjects, and duration and level of the noise exposure.

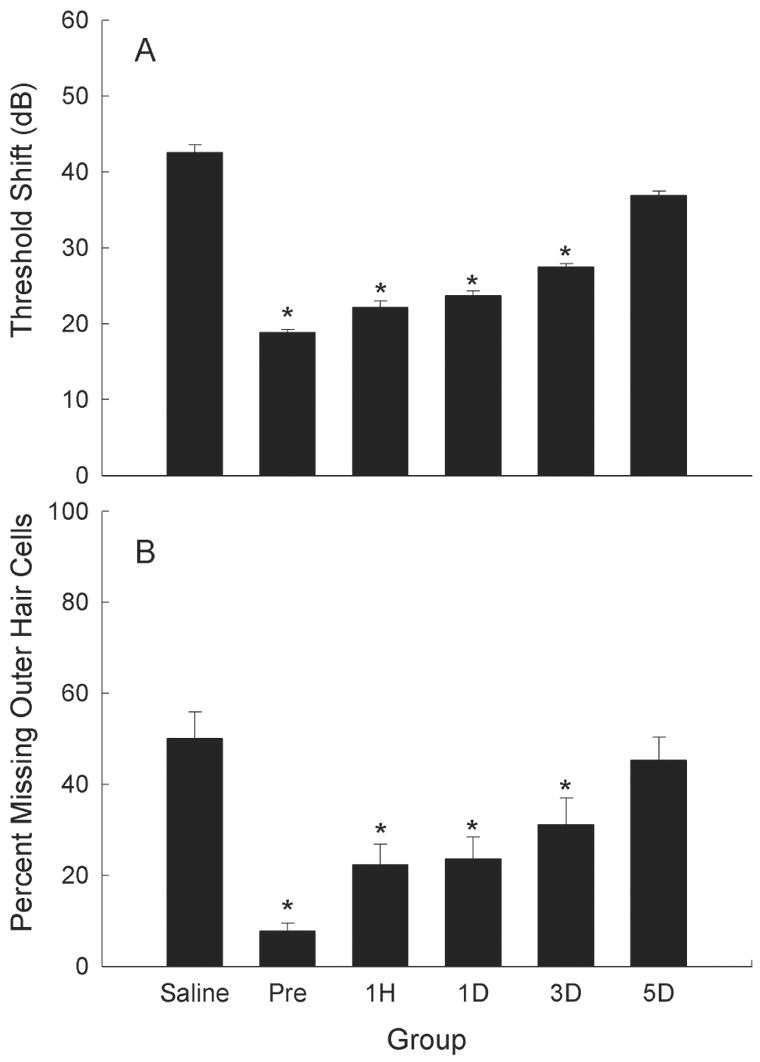

Figure 5.

Antioxidant treatment reduces noise-induced hearing loss even when treatment is delayed relative to the noise insult. Treatment with Trolox (a synthetic analogue of Vitamin E) and salicylate reduced threshold deficits (A, average hearing loss at 4, 8, and 16 kHz, mean ± SE) and hair cell loss (B, 10–16 mm from the apex) 10 days post-noise (adapted from Yamashita et al., 2005a) when treatment was initiated 3 days pre-noise, or up to 3 days post-noise (1 hour, 1 day, or 3 days post-noise). Noise exposure was an octave band noise centered at 4 kHz and presented at a level of 120-dB SPL for 5 hours. Data are mean ± SE, and asterisks indicate statistically reliable differences relative to saline-treated controls. Adapted from Yamashita et al. (2005a); see also Miller et al. (2006b).

Summary

Taken together, there is compelling evidence for a role of free radicals in NIHL and noise-induced sensory cell death. The ability of a variety of antioxidant agents to attenuate noise-induced hearing deficits and sensory cell loss is clear. Preclinical translational studies have confirmed the safety of multiple antioxidant agents, and many have been used in humans for years with few adverse effects reported. Thus, it is time to invest in human clinical trials to evaluate antioxidant prevention of NIHL in man. Recent human trials have already shown prevention of aminoglycoside-induced hearing loss via salicylate therapy (Sha et al., 2006). Together, these trials will demonstrate the practicality of antioxidant treatment of the inner ear to prevent hearing loss from a variety of environmental stresses.

Additional Interventions

It is likely that additional factors, intervening at different points in the cell death pathway, may enhance protection against NIHL when delivered in combination with antioxidant agents. Many of these factors could be readily applied to human populations based on demonstrated safety in man; others are further from human application. In the following sections of this review, evidence supporting the utility of other potential interventions is described. Data are drawn from the auditory system where possible. In some cases, the therapeutic potential of the proposed interventions has been clearly demonstrated in other cellular or neural systems but the application of these therapies to the auditory system has not been directly explored. Evidence drawn from other systems is clearly identified as such, and is used to highlight the potential for new therapeutic interventions that may one day be used reduce NIHL.

Vasodilation and NIHL

In most tissues, increased metabolism is associated with increased blood flow, which provides additional oxygen to stressed cells. However, in the cochlea, high levels of noise decrease blood flow (Perlman and Kimura, 1962; Lipscomb and Roettger, 1973; Thorne and Nuttall, 1987; Miller et al., 1996; 2006b). Decreased blood flow in the cochlea is a direct consequence of noise-induced reductions in blood vessel diameter and red blood cell velocity (Quirk et al., 1992; Quirk and Seidman, 1995). Reduced cochlear blood flow has significant implications for metabolic homeostasis in the cochlea, as cellular metabolism clearly depends on adequate O2 and nutrients as well as elimination of waste products (e.g., Miller et al., 1996).

Noise-induced free radical formation is a significant factor in decreased cochlear blood flow. Ohinata et al. (2000a) were the first to clearly establish a causal link between ROS production and reduced cochlear blood flow. In their studies, an enzymatic immunoassay (ELISA) for 8-isoprostane-F2α (8-iso-PGF2α) (a potent vasoconstrictor, see Morrow and Roberts, 1996; Morrow and Roberts, 1997; Roberts and Morrow, 1997) revealed a robust (>30 fold) increase in free radical formation following noise (Ohinata et al., 2000a) (see Figure 6). Infusion of 8-iso-PGF2α into the local blood supply to the cochlea [via the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA)] decreased cochlear blood flow; systemic (intra-venous) 8-iso-PGF2α produced physiological changes consistent with constriction of the cochlear vasculature (Miller et al., 2003a). The selective antagonist SQ29548 blocked the effects of 8-iso-PGF2α, and both SQ29548 and GSHE eliminated the noise-induced reduction in blood flow (Miller et al., 2003a). Taken together, these data support the following: 1) high-level noise induces ROS formation, particularly in tissues associated with the cochlear vasculature (lateral wall); 2) ROS in the cochlear vasculature, and to a lesser extent the organ of Corti, peroxidize lipids which results in formation of 8-iso-PGF2α; 3) 8-iso-PGF2α induces vasoconstriction; and 4) reduction of NIHL by antioxidants is potentially mediated at least in part by reducing vasoconstriction that occurs with ROS production. Noise-induced ROS and the consequent depression of cochlear blood flow may promote ischemia, leading to further ROS production and decreased blood flow, so that a positive feedback loop is established in the absence of an effective antioxidant therapeutic.

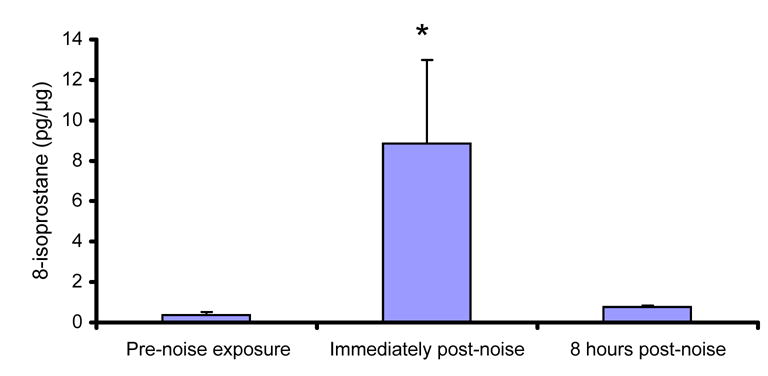

Figure 6.

Byproducts of free radical formation can be measured in the cochlea post-noise. Enzymatic (ELISA) immunoassay for 8-isoprostane-F2α in the cochlea revealed a robust (approximately 30-fold) increase in free radical formation immediately following 5 hours of noise (adapted from Ohinata et al., 2000a). Noise exposure was an octave band noise centered at 4 kHz and presented at a level of 115-dB SPL. Levels of 8-isoprostane-F2α increased almost linearly during the duration of the exposure (based on samples collected immediately following 1, 3, and 5 hour exposure durations; not shown), and decreased rapidly after the termination of noise (8 hours post-noise illustrated, mean ± SE). Reprinted from Miller et al. (2006b).

Consistent with the hypothesis that agents that reduce vasoconstriction and/or have vasodilating effects may reduce NIHL, various post-noise electrophysiological measures were improved with betahistine [which has long been used clinically in the treatment of Meniere’s disease (Perez et al., 1997; Claes and Van de Heyning, 2000; James and Burton, 2001)], or hydroxyethyl starch (HES) 70 or HES 200 (Lamm and Arnold, 2000). HES may be one of the most effective blood flow promoting drugs, particularly in combination with the steroid prednisolone (Lamm and Arnold, 1999). Another agent that may reduce NIHL via protection against noise-induced decreases in cochlear blood flow and oxygenation is magnesium (Altura et al., 1992; Haupt and Scheibe, 2002). As a consequence of its effects on blood flow, other biochemical mechanisms (described below), or some combination of effects, magnesium supplements protect against NIHL in humans (Joachims et al., 1993; Attias et al., 1994; 2004), guinea pigs (Scheibe et al., 2000; Haupt and Scheibe, 2002; Scheibe et al., 2002; Attias et al., 2003; Haupt et al., 2003), and rats (Joachims et al., 1983). In contrast, magnesium deficient diets increase susceptibility to NIHL in rats (Joachims et al., 1983) and guinea pigs (Ising et al., 1982; Scheibe et al., 2000). In addition to the well characterized effects on vasodilation, biochemical effects of magnesium include modulation of calcium channel permeability, influx of calcium into cochlear hair cells, and glutamate release (Gunther et al., 1989; Cevette et al., 2003). Regardless of the specific mechanism, magnesium clearly attenuates NIHL, and it is safe for use in humans.

Growth factors

Neurotrophic factors (NTF) scavenge free radicals, interrupt cell death pathways, and modulate calcium homeostasis, any of which may attenuate NIHL. Withdrawal of NTF leads to ROS formation and initiates a cascade of events that lead to cell death (for review, see Kirkland and Franklin, 2003). These mechanisms are thought to play major roles in neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease (de la Monte et al., 2000; Gilgun-Sherki et al., 2003; Chong et al., 2004; Summers, 2004), Parkinson’s disease (Le and Frim, 2002; Tenenbaum et al., 2002; Thomas and Le, 2004), and traumatic brain injury (Lewen et al., 2000). NTF-mediated protection against excitotoxic apoptosis in cultured neurons may involve calcium homeostasis and free radical metabolism (Glazner and Mattson, 2000). A variety of evidence supports this conclusion. First, oxidative stress driven by intermittent hypoxia or exogenous ROS stimulates brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) release (Wang et al., 2006). Second, basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF, or FGF2) regulates intracellular calcium and mitochondrial energy metabolism (El Idrissi and Trenkner, 1999). Third, BDNF and neurotrophin-3 (NT3) likely modulate calcium homeostasis (Nakao et al., 1995), and, finally, the use of NTF to restore calcium homeostasis has been proposed for Alzheimer’s disease (Holscher, 2005) and diabetes (Huang et al., 2002). Taken together, evidence drawn from multiple biological systems suggests NTF will prevent noise-induced damage in the cochlea, with protective effects mediated by attenuation of ROS as well as effects on calcium homeostasis.

Delivery of exogenous NTF into the cochlea can prevent noise-induced hair cell death. For example, FGF2 prevents noise-induced hair cell death and NIHL in vivo in guinea pigs (Zhai et al., 2004). Acidic fibroblast growth factor (aFGF, or FGF1) was similarly effective; delivered via osmotic mini-pump, it reduced PTS in guinea pigs (although TTS deficits were not reduced, an effect similar to that of antioxidant agents) (Sugahara et al., 2001). While the protective effects of FGF1/FGF2 were not found in all studies (see Yamasoba et al., 2001; David et al., 2002), the effects of other NTF have generally been protective, with glial cell line derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) (Ylikoski et al., 1998; Yamasoba et al., 1999) and NT3 (Shoji et al., 2000) shown to prevent noise-induced deficits in guinea pigs when infused chronically using osmotic mini-pumps. That BDNF (Shoji et al., 2000), and in some studies FGF1 and FGF2 (Yamasoba et al., 2001), did not reduce noise-induced injury may suggest the effect is growth factor specific, which could be a consequence of different NTF receptors on the hair cells (Ylikoski et al., 1993; Pirvola et al., 1997).

In addition to preserving hair cell survival post-noise, NTF have been shown to be extremely effective at preserving neural survival in the absence of surviving hair cells. In the auditory system, auditory nerve degeneration may be a consequence of NTF deprivation that occurs when sensory cells in the organ of Corti are damaged. In the presence of intact hair cells, damaged auditory nerve peripheral processes will regrow and restore auditory sensation (Puel et al., 1991; 1995; Le Prell et al., 2004). However, with loss of hair cell targets, auditory nerve regrowth is minimal (Bohne and Harding, 1992; Strominger et al., 1995; Lawner et al., 1997; McFadden et al., 2004). Indeed, much of the basic research defining protection via NTF in the auditory system has been in the context neural preservation following aminoglycoside-induced cell death and deafness. Combinations of agents, which can include non-growth factor substances, have been found to enhance efficacy over single agents both in vivo and in vitro (Lefebvre et al., 1991; 1992; Hartnick et al., 1996; Gabaizadeh et al., 1997; Marzella et al., 1997; Mou et al., 1997; Duan et al., 2000; Kawamoto et al., 2003). Importantly, a single NTF or combinations of NTF can be highly efficacious in promoting auditory nerve survival even with temporal delay in onset of treatment relative to deafening. Nerve growth factor (NGF) delivered alone (Shah et al., 1995), or a combination of BDNF, NT3, and neurotrophin-4/5 (Gillespie et al., 2004), enhanced neural survival when administration was delayed by 2 weeks. The combination of BDNF and ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) enhanced auditory nerve survival even at delays of up to 6 weeks post-deafening (Yamagata et al., 2004). Consistent with an important role for FGF1 in neurite outgrowth in the immature auditory system (Dazert et al., 1998; Hossain and Morest, 2000), we recently demonstrated the efficacy of BDNF plus FGF1 in promoting systematic regrowth of the peripheral process of the auditory nerve even after a 6-week period of deafening (Miller et al., 2003b; 2006a). Together, these results suggest post-noise treatment with NTF may prevent neural degeneration that occurs consequent to noise-induced sensory cell death.

Steroids

Glucocorticoid receptors are expressed in almost every type of cell, although there is variation in receptor density across cells (Barnes and Adcock, 1993). Glucocorticoid-mediated protection of cells may result from rapid modulation of calcium channels and calcium mobilization. Based on tissue and cell type, glucocorticoids can inhibit (He et al., 2003) or enhance (Zhou et al., 2000; Takahashi et al., 2002) intracellular calcium. Yukawaw et al. (2005) recently reviewed the divergent effects of glucocorticoids on calcium channels and intracellular calcium mobilization. Among the other molecular mechanisms of action of glucocorticoids (reviewed by Barnes and Adcock, 1993) are steroid-regulated transcription of target genes, interactions with other transcription factors including potent inhibition of gene transcription induced by tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) and phorbol esters, which activate transcription factor activator protein-1 (AP-1), inhibition of cytokines that produce their effects on gene transcription via activation of AP-1, direct inhibition of cytokine genes, and potent inhibition of nitric oxide synthase (NOS).

In the cochlea, glucocorticoid receptors are associated with stria vascularis, spiral ligament, spiral limbus and spiral ganglion, and to a lesser extent, the organ of Corti (ten Cate et al., 1993; Pitovski et al., 1994; Zuo et al., 1995; Rarey and Curtis, 1996). Intra-cochlear infusion of dexamethasone, a member of the glucocorticoid family of steroids, protects hair cell survival and auditory function from toxic effects of noise (Lamm and Arnold, 1998; Takemura et al., 2004), and other insults (Himeno et al., 2002; Tabuchi et al., 2003). Consistent with the notion of endogenous steroid-based protection in the inner ear, noise elevates glucocorticoid plasma concentration (Rarey et al., 1995), and down-regulates glucocorticoid receptors in the cochlea (Terunuma et al., 2001). In addition, circulating corticosteroid levels are enhanced during and after mild restraint stress (Curtis and Rarey, 1995; Wang and Liberman, 2002); during these periods of corticosteroid elevation, animals are less susceptible to NIHL (Wang and Liberman, 2002). Finally, blocking glucocorticoid receptors enhances NIHL (Mori et al., 2004).

The protective effects of dexamethasone may be a consequence of blood-flow promoting properties of dexamethasone in the inner ear (Shirwany et al., 1998). Alternatively, glucocorticoid-based protection may result from rapid modulation of calcium channels and calcium mobilization as described in other biological systems. For example, corticosteroids may inhibit calcium entry in auditory cells, thus reducing excitotoxic injury, and reducing NIHL. Consistent with this suggestion, Lamm and Arnold (1998) speculated that prednisolone may reduce NIHL in part via actions at mineralocorticoid receptors, activation of the enzyme Na,K-ATPase, and restoration of disturbed cellular osmolarity. As described above, steroids also regulate interactions with the transcription factors TNFα and AP-1, and inhibit NOS. TNFα (Satoh et al., 2002; Aminpour et al., 2005; Zou et al., 2005), AP-1 (Ogita et al., 2000; Shizuki et al., 2002; Matsunobu et al., 2004; Nagashima et al., 2005), and NOS (Hess et al., 1999; Ohinata et al., 2003; Shi et al., 2003; Shi and Nuttall, 2003; Yamane et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2005) have all been implicated in the cochlear response to stress. Thus, the specific mechanism(s) of action of dexamethasone in prevention of NIHL remain to be precisely identified.

Glutamate excitotoxicity

The application of glutamate (Janssen et al., 1991) or glutamate agonists (Puel et al., 1991; 1994; Le Prell et al., 2004) results in functional deficits and swelling of auditory neurons equivalent to those observed after noise exposure (Robertson, 1983; Puel et al., 1998; Yamasoba et al., 2005). Large concentrations of glutamate are released in response to loud noise, and toxic concentrations of this excitatory amino acid lead to large sodium and potassium ion flux across the post-synaptic membranes and passive entry of chlorine; this osmotic imbalance results in entry of fluid into cells which in turn produces swelling, and ultimately, rupturing of cell membranes and degeneration (for review, see Le Prell et al., 2001).

In addition to the classic ‘excitotoxic’ pathway, a second glutamate-driven oxidative cell death pathway has now been well characterized with evidence drawn from neuronal cells across biological systems. Death of neuronal cells via this oxidative pathway is attributed to increased calcium influx that drives NOS production, and ultimately RNS formation (Dykens et al., 1987; Dawson et al., 1991; Coyle and Puttfarcken, 1993; Lafon-Cazal et al., 1993a; 1993b; Lipton et al., 1993; Puttfarcken et al., 1993; Schinder et al., 1996; White and Reynolds, 1996; Ha and Park, 2006). Deficits in calcium homeostasis are clearly implicated in excitotoxin-induced cell death in the auditory system (Harada et al., 1994; Puel et al., 1994), and production of NOS is part of the cochlear response to stress (Hess et al., 1999; Hanson et al., 2003; Ohinata et al., 2003; Shi et al., 2003; Shi and Nuttall, 2003; Yamane et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2005). Fessenden and Schacht (1998) have proposed a model in which calcium entry activates neuronal NOS in auditory neurons, thereby driving NO production, which reacts with superoxide to form the highly toxic peroxynitrite radical, and ultimately results in neural degeneration. Thus, RNS scavengers might act not only to preserve hair cells, but also to preserve auditory neurons. Consistent with this, ebselen, which is an efficient scavenger of peroxynitrite as well as a gluthione peroxidase mimic, prevented noise-induced swelling of the auditory nerve dendrites (Yamasoba et al., 2005). Antioxidants also reduce glutamate-induced toxicity in other neural systems (Matteucci et al., 2005; Tastekin et al., 2005; Ibarretxe et al., 2006).

Calcium homeostasis

Overview

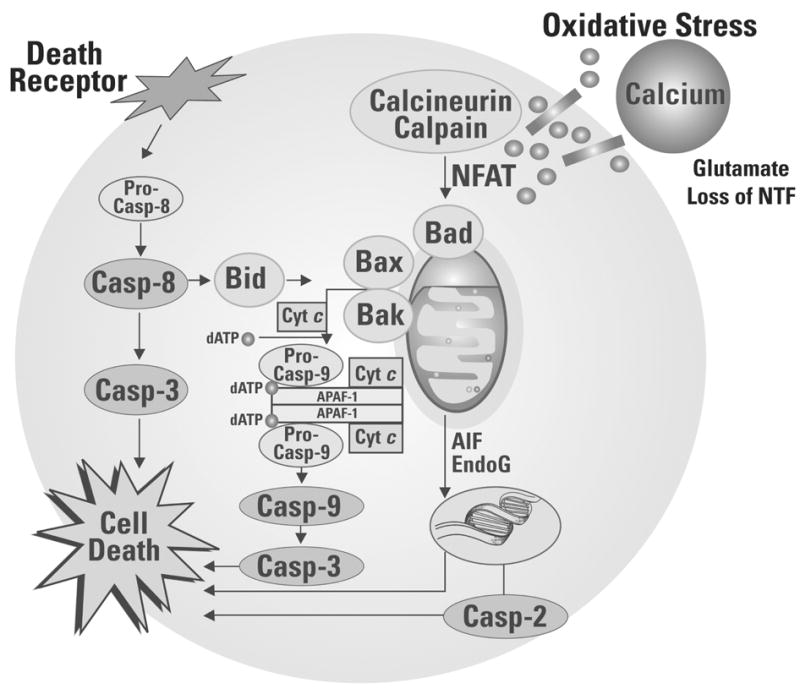

All of the substances described above modulate calcium channel permeability and/or calcium homeostasis in at least some biological systems. Noise exposure increases calcium concentration not only in afferent dendrites, but also in hair cells (Fridberger and Ulfendahl, 1996; Fridberger et al., 1998). These elevations in intracellular calcium have been implicated in hair cell damage and hearing loss post-noise, as deficits induced by noise, chemotherapeutics, or H2O2, can be blocked by calcium channel blockers (Heinrich et al., 1999; Dehne et al., 2000; Heinrich et al., 2005; So et al., 2005). One mechanism through which changes in calcium concentration may lead to cell death is phospholipase A2 (PLA2) activation. Upregulation of PLA2 occurs with oxidative stress, and the calcium-dependant isoforms have been widely implicated in neurodegenerative disease (for review, see Sun et al., 2005). PLA2 activation and cell death appear to be causally linked, with both PLA2 activation and cytotoxity shown to be calcium dependant (Caro and Cederbaum, 2003). Changes in calcium concentration may also lead to cell death via calpain-dependent cleavage of calcineurin (Kim et al., 2002). Lasting elevations in intracellular calcium concentration activate the calcium-dependant phosphatase calcineurin, which activates the transcription factor NFAT (nuclear factor of activated T-lymphocytes) and initiates apoptosis (see Morioka et al., 1999; Huang et al., 2001; Li et al., 2002; Sommer et al., 2002; Feske et al., 2003; Christians et al., 2004; Gooch et al., 2004; Kalivendi et al., 2005; Rivera and Maxwell, 2005). Additional detail on calpain- and calcineurin- mediated mechanisms of cell death in the inner ear are provided first; we then review the role of Bcl-2 anti-apoptotic proteins, caspase inhibitors, and stress-activated kinases in the inner ear. Caspase-mediated cell death can be driven by an extrinsic (receptor-activated) pathway, or an intrinsic (mitochondria-mediated) pathway. Whereas receptor-mediated cell death is caspase-dependent, mitochondrial pathways can lead to cell death via either caspase activation or translocation of apoptosome inducing factor (AIF) and endonuclease G (EndoG) (for review, see Orrenius et al., 2003). In contrast to these pathways, the JNK pathway is activated by a complex termed apoptotic signaling kinase 1 (ASK-1). ASK-1, formed in the endoplasmic reticulum, includes tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-receptor-associated-factor-2 (TRAF-2) and a transmembrane serine/threonine (Ser/Thr) kinase, Ire1α (for review, see Orrenius et al., 2003). Extrinsic, intrinsic, and an additional caspase-2 dependant apoptotic pathway are illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Oxidative stress initiates a cascade of reactions leading to cell death via one or more sequences of molecular events. First, calcium-dependant calcineurin/calpain activation can initiate downstream events including dephosphorylation of NFAT and activation of BAD, release of cytochrome c, activation of caspases 9 and 3, and cell death. Second, a caspase-2 dependant pathway to cell death can be triggered by DNA damage. Third, caspase-independent pathways to cell death include release of AIF and EndoG from the mitochondria. Translocation to the cell nucleus results in chromatin condensation and high-molecular mass-chromatin fragments. Fourth, receptor-mediated cell death begins with ligation of death receptors, death inducible signaling complex is formed, which activates pro-caspase-8. Caspase-8 can activate caspase-3, leading to cell death, or cleave Bid, which results in translocation and insertion of Bax and/or Bak into the mitrochondrial membrane and release of cytochrome c, activation of caspases 9 and 3, and cell death. The caspase-2 dependent pathway differs from the caspase-8 and caspase-9 dependent pathways in that pro-caspase-2 is activated by DNA damage. Different cell types vary in the extent to which apoptotic cell death depends on the activation of caspase-2 (Lassus et al., 2002; Robertson et al., 2002), and a specific role for caspase-2 in apoptotic cell death in the inner ear has not been described to date.

Calpain-mediated cell death

Calpains are a family of calcium-dependent cysteine proteases found ubiquitously in mammalian cells and activated at either micromolar (10–20 μM, calpain-I, μ-calpain) or millimolar (250–750 μM, calpain-II, m-calpain) calcium concentrations (for review, see Stracher, 1999). Activation of calpain typically results in limited proteolysis, however, this limited protein degradation can trigger more extensive protein destruction processes (for review, see Stracher, 1999). Calpain activation clearly accompanies noise-induced damage to the cochlea. Calpain immunoreactivity is minimal in normal ears, whereas in noise-exposed ears, intense immunoexpression is observed in the OHC nuclei, the presumably efferent neuropil at the bases of the OHCs, and in the nerve fibers projecting to the organ of Corti (Wang et al., 1999b). Leupeptin is a potent calpain inihibitor; pre-treatment with leupeptin (delivered to the inner ear via osmotic mini-pump) significantly reduces noise-induced sensory death (Wang et al., 1999b). Calpains appear to play a similar role in aminoglycoside-induced trauma. After amikacin, immunolabeling for byproducts of calpain-cleavage reveals an accumulation in hair cells (Ladrech et al., 2004; see also Jiang et al., 2006, who report punctuate distribution of calpain I in outer hair cells after kanamycin treatment), and leupeptin prevents in vitro gentamicin-induced sensory cell death (Ding et al., 2002a). The pattern of calpain expression observed after carboplatin includes intense labeling of nerve fibers and their myelin sheaths and no labeling of hair cells in the organ of Corti (Ding et al., 2002b). Corresponding to differences in calpain expression, calpain inhibitors do not prevent hair cell death induced by carboplatin (Ding et al., 2002b) or cisplatin (Cheng et al., 1999).

When the long-term safety of leupeptin (1 mg/ml in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution, administered to the round window membrane) was evaluated in an 8-week study, there were no deficits in cochlear blood flow, threshold sensitivity, or hair cell death, leading to the proposal for clinical trials to evaluate leupeptin for prevention of NIHL (Tang et al., 2001). While intra-cochlear application of leupeptin appears relatively safe and effective for preventing noise and aminoglycoside-induced damage, the potential risks of prolonged oral dosing require additional evaluation. If the calpain inhibitor leupeptin must be delivered via intra-cochlear administration, this limits the utility of this agent as a preventative for periodic exposure to noise. However, one could envision this agent being used to prevent hearing loss associated with high-dose aminoglycoside antibiotics, perhaps in combination with antioxidant agents as described recently by Sha et al. (2006).

Calcineurin-mediated cell death

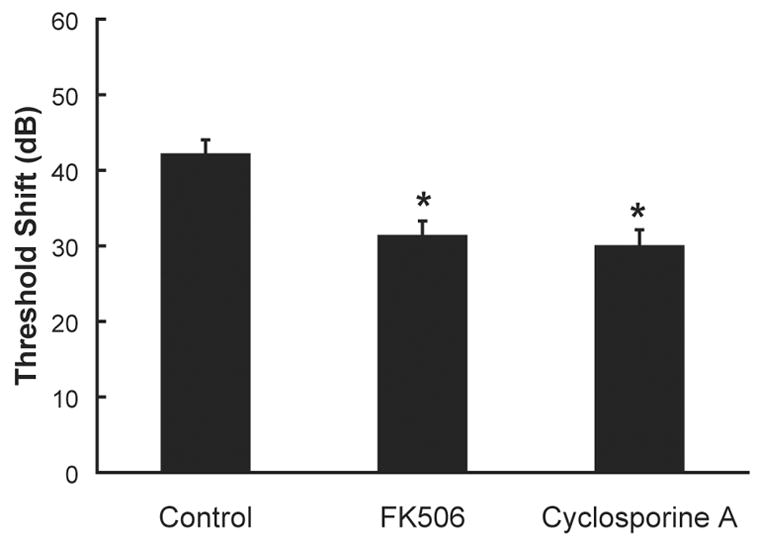

One consequence of calcium-dependant calpain activation is calpain-dependent cleavage of calcineurin. Noise trauma induces not only calpain activation, as described above, but also calcineurin activation, as shown by calcineurin immunostaining in outer hair cells. Maximum labeling was evident immediately post-noise, labeling decreased from 1 to 3 days post-noise, and little or no labeling remained 7 days post-noise (Minami et al., 2004). These results indicate that prevention of calcineurin activation may reduce noise-induced trauma; and the calcineurin inhibitors cyclosporin A and FK506, delivered directly to the cochlear perilymph via osmotic mini-pump for 14 days (4 days pre-noise, 10 days post-noise), reduced NIHL and noise-induced outer hair cell death in guinea pigs (Minami et al., 2004) (see figure 8). Protection against NIHL and sensory cell death has since been demonstrated in guinea pigs and mice treated with a single intra-peritoneal injection of cyclosporin A or FK506 immediately prior to noise exposure (Uemaetomari et al., 2005), an observation that has significant clinical utility as systemic application may be more feasible than intra-cochlear application at least in the near term. Both immediate and longer-lasting hearing loss were evaluated by Uemaetomari et al. (2005); while short term NIHL was not affected, permanent threshold deficits were significantly reduced.

Figure 8.

Pre-noise treatment with calcineurin inhibitors reduces noise-induced threshold deficits. Treatment with the calcineurin inhibitors FK506 (10 μg/ml) or cyclosporine A (10 μg/ml), delivered directly into the cochlear perilymph, reduced noise-induced threshold deficits (average hearing loss at 4, 8, and 16 kHz; mean ± SE). Noise exposure was an octave band noise centered at 4 kHz and presented at a level of 120-dB SPL for 5 hours. Asterisks indicate statistically reliable differences relative to subjects treated with artificial perilymph (control). Adapted from Minami et al. (2004).

Bcl-2 anti-apoptotic proteins

Work in other neural systems has demonstrated that calcineurin activation initiates downstream events including dephosphorylation and activation of BAD (a Bcl-2 family protein which activates apoptotic cell death pathways), release of cytochrome c, activation of caspases 9 and 3, and cell death (Springer et al., 2000; Nottingham et al., 2002; Agostinho and Oliveira, 2003; Almeida et al., 2004; Shou et al., 2004; Watabe and Nakaki, 2004; Cardoso and Oliveira, 2005; Grosskreutz et al., 2005; Jayanthi et al., 2005). Inhibiting calcineurin activation reduces BAD dephosphorylation and improves cell survival (Wang et al., 1999a; Springer et al., 2000; Uchino et al., 2002; Berthier et al., 2004; Mano et al., 2004; Shou et al., 2004; Watabe and Nakaki, 2004; Yang et al., 2004a; Biswas et al., 2005; Cardoso and Oliveira, 2005; Huang et al., 2005). Reducing calcineurin activation also reduces the downstream caspase activity (Springer et al., 2000; Nottingham et al., 2002; Agostinho and Oliveira, 2003; Cardoso and Oliveira, 2005; Grosskreutz et al., 2005). Interventions that maintain calcium homeostasis and thus provide an upstream prevention of calcineurin activation are one approach to reducing calcineurin-mediated cell death (see for example, Springer et al., 2000, who report that NMDA receptor antagonists block BAD dephosphorylation and abolish caspase 3 activation). Prevention of cell death can also be accomplished via treatment with Bcl-2 family members. The anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 binds and/or sequesters calcineurin, thus preventing NFAT dephosphorylation and translocation (Shibasaki and McKeon, 1995; Shibasaki et al., 1997; Srivastava et al., 1999; Simizu et al., 2000; Biswas et al., 2001; Erin et al., 2003a; Erin et al., 2003b).

That these results are relevant to the auditory system was demonstrated recently. Noise exposure that resulted in TTS up-regulated expression of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member, Bcl-xL, in the outer hair cell region. In contrast, more intense exposures that lead to PTS and hair cell loss up-regulated the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family member, Bak, in the outer hair cell region (Yamashita et al., 2005b). These observations are consistent with other reports that acoustic trauma decreases Bcl-2 expression in the cochlea (Niu et al., 2003). Decreases in Bcl-2 have been reported in the cochlea of aged or cisplatin-treated gerbils (Alam et al., 2000; 2001), and over-expression of Bcl-2 in transgenic mice increases hair cell survival following neomycin exposure in organotypic cultures of the adult mouse utricle (Cunningham et al., 2004). These observations suggest a significant role of Bcl-2 genes in NIHL as well as recovery from other auditory trauma.

Caspase-dependent cell death: Extrinsic (receptor-mediated) mechanisms

The extrinsic or “receptor-mediated” pathway has been well characterized in many cell types. As reviewed by Orrenius et al. (2003, see their Box 1), death inducing signaling complex recruits pro-caspase-8 molecules (which, like all caspases, are constitutively present in normal, healthy cells). This recruitment of pre-caspase-8 molecules results in an induced proximity of multiple pro-caspase-8 molecules. This induced proximity, combined with low levels of proteolytic activity in the caspase-8 proenzyme, results in either auto-cleavage of the pro-domain and activation of the mature enzyme, or dimerization and activation without cleavage (Muzio et al., 1998; Shi, 2004). Caspase activation results in proteolytic cleavage of many protein substrates; indeed, hundreds have been reported (Fischer et al., 2003). One specific consequence of caspase activation is to cleave Bid, which induces translocation of Bax and/or Bak into the mitochondrial membrane. This induces release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria, which, in the presence of dATP, forms a complex with apoptosis activating factor-1 (Apaf-1) and pro-caspase-9. This cytochrome c complex (often called an ‘apoptosome’) activates caspase-9, which results in activation of caspase-3, formation of cell death substrates, and cell death. Caspase-dependent apoptotic cell death has been well characterized across biological systems [see for example, reviews by Mattson (2000, see his Figure 1) and Orrenius et al. (2003, see their Box 1)].

The number of caspases known to play a role in cell death in the inner ear is small relative to the number of caspases identified to date. There are at least 14 known caspases, broadly grouped as apoptotic initiators (caspases -2, -8, -9, and -10) and apoptotic effectors (caspases -3, -5, -6, and -7) (Eldadah and Faden, 2000; Nicotera et al., 2003; Eshraghi and Van De Water, 2006). Evidence that caspase -5, -6, -7 and -10 are involved in apoptosis in the inner ear is emerging (Eshraghi and Van De Water, 2006), and it is clear that other caspase-dependent pathways to cell death are relevant (for reviews, see Cheng et al., 2005; Eshraghi and Van De Water, 2006). Caspase-1 (Zhang et al., 2003), caspase-3 (Hu et al., 2002; Nicotera et al., 2003; Watanabe et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2003; Ladrech et al., 2004; Mangiardi et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2004b; Labbe et al., 2005; Lang et al., 2005; Wei et al., 2005; Hu et al., 2006), caspase-8 (Devarajan et al., 2002; Nicotera et al., 2003), and caspase-9 (Devarajan et al., 2002; Nicotera et al., 2003), are activated in the inner ear after noise exposure or other stressors. This expression has been observed in hair cells (Nicotera et al., 2003; Ladrech et al., 2004; Mangiardi et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2004b; Hu et al., 2006), spiral ganglion cells (Ladrech et al., 2004; Labbe et al., 2005; Lang et al., 2005), stria vascularis and spiral ligament (Watanabe et al., 2003), and lateral wall (Labbe et al., 2005). Confirming an important role for caspase activation in the pathway to cell death, caspase inhibitors have been shown to prevent cell death in the inner ear after aminoglycoside treatment, chemotherapeutics, hypoxia, or NTF withdrawal (Cheng et al., 1999; Nakagawa et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2003; Corbacella et al., 2004; Okuda et al., 2005; Wei et al., 2005).

The hierarchy of caspase activation is perhaps best described for hair cells from the mouse utricle following aminoglycoside exposure (Cunningham et al., 2002). Both caspase-8 and caspase-9 are activated by neomycin exposure; inhibiting caspase-9-like activity prevented activation of downstream caspase-3 and provided significant protection of hair cells whereas inhibiting caspase-8-like activity did not prevent caspase-3 activation or hair cell death (Cunningham et al., 2002). Caspase inhibitors similarly prevent aminoglycoside-induced death of cultured vestibular hair cells from the chick utricle (Matsui et al., 2002). Chicks treated with systemic aminoglycosides in vivo did not develop aminoglycoside-induced vestibular deficits when a pan-caspase inhibitor was infused into the inner ear (Matsui et al., 2003). Taken together, caspase inhibitors have the potential to play a key role in protection of both auditory and vestibular hair cells.

Intrinsic (mitochondria-mediated) mechanism of cell death

Apoptotic signals that directly affect the mitochondria can activate caspases that lead to cell death via ‘apoptosome’ formation as described above, and mitochondria-mediated cell death can thus be caspase-dependant [i.e., Mattson (2000, see his Figure 1) and Orrenius et al. (2003, see their Box 1)]. Alternatively, a second intrinsic mitochondria-mediated pathway to cell death involves translocation of apoptosome inducing factor (AIF) and endonuclease G (EndoG) from the mitochondria to the nucleus, which results in cell death via caspase-independent mechanisms (for review see Orrenius et al., 2003). Cell death accompanied by EndoG translocation in the absence of markers for cytochrome c, caspase-3, caspase-9, and JNK was recently shown in the mouse cochlea after treatment with kanamycin (Jiang et al., 2006). Thus, it appears that both caspase-dependent and caspase-independent mechanisms can result in cell death in the cochlea.

Stress-activated kinase activity

The c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) group of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases phosphorylate the transcription factor c-Jun (Kyriakis et al., 1994). As described in the highly readable summary by Eshraghi and Van de Water (2006, see their Figure 2), a typical MAP kinase (MAPK) pathway is initiated by receptor-driven activation of small G-proteins and GTPases, the subsequent protein kinase cascades are composed of up to 4 tiers of kinase molecules, and kinase activity culminates in activation of a specific JNK-MAPK molecule (JNK-1, JNK-2, or JNK-3, which are protein products of three different genes).

The first evidence that activation of the JNK pathway leads to cell death in the inner ear was provided with immunocytochemical labeling for phospho-JNK and phospho-c-Jun in neomycin-stressed hair cells in vitro (Pirvola et al., 2000), and gentamicin-stressed hair cells in vivo (Ylikoski et al., 2002). Incubating hair cells with the JNK-inhibitor CEP-1347 prevented neomycin-induced cell death in vitro (Pirvola et al., 2000); in vivo treatment reduced noise-induced cell death and NIHL (Pirvola et al., 2000) as well as gentamicin-induced cell death and hearing loss (Ylikoski et al., 2002). Similar results were obtained with D-JNKI-1; this cell permeable peptide which blocks the MAPK-JNK signal pathway reduced in vitro neomycin ototoxicity and in vivo neomycin and noise-induced toxicities (Wang et al., 2003). Other more preliminary results suggest D-JNKI-1 may be effective even when treatment is delayed several hours relative to noise insult (Guitton et al., 2004). The JNK pathway appears to be similarly involved in aminoglycoside-induced death of vestibular hair cells. In cultured vestibular hair cells, neomycin treatment results in an increase in phospho-c-Jun labeling, followed by an increase in cytoplasmic cytochrome c and activation of caspase-3 (Matsui et al., 2004). Hair cell survival was promoted in vitro by treatment with the JNK inhibitor CEP-11004 (Matsui et al., 2004).

Interventions that inhibit the JNK pathway may have broad clinical utility (for review, see Zine and Van De Water, 2004). Pretreatment with an antisense oligonucleotide that blocks amplification of c-jun transcription factor, or agents that intervene in the JNK/c-Jun pathway (including curcumin and PD-098059), reduce apoptotic cell death associated with various in vitro insults, including neurotrophin-withdrawal, cisplatin, and exposure to HNE (Scarpidis et al., 2003). Of particular clinical relevance, direct delivery of D-JNKI-1 into the scala tympani eliminated progressive hearing loss in cochleae in which electrodes were inserted to model trauma associated with insertion of a cochlear prosthesis (Van De Water et al., 2005; Eshraghi and Van De Water, 2006).

Additivity and/or synergy among factors

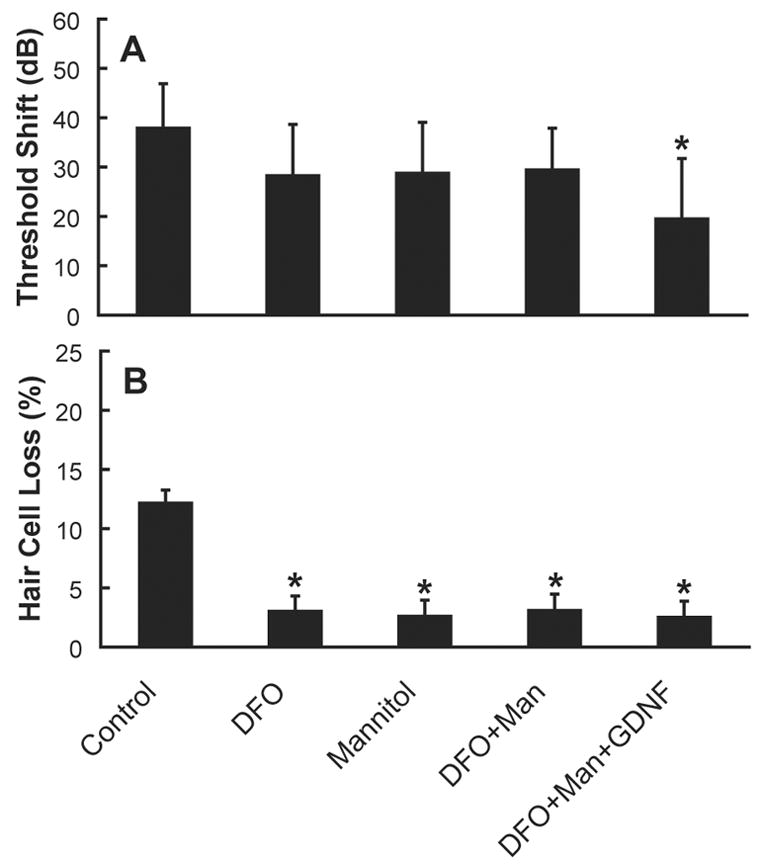

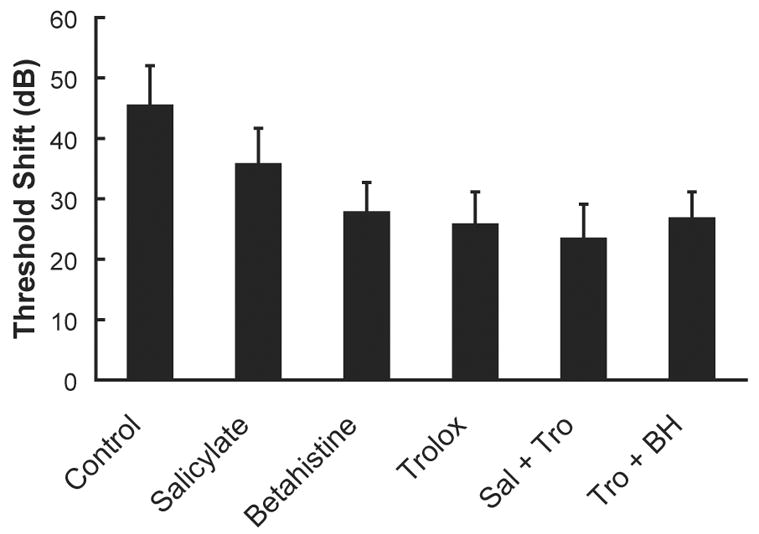

Given that none of the interventions tested to date completely prevent NIHL and noise-induced sensory cell death, it would seem reasonable to seek an additive effect with a combination of factors that intervene at multiple sites in the biochemical cell death cascade. Yamasoba et al. (1999) therefore evaluated a combination of an antioxidant (mannitol, a hydroxyl scavenger), a neurotrophic factor (GDNF), and an iron chelator (deferoxamine mesylate, DFO), each of which individually attenuate NIHL. However, they found little evidence for additive effects; i.e., treatment with a combination of agents yielded no greater protection than the most effective agent delivered alone (see Figure 9). We recently evaluated the potential for additive effects in a small number of animals treated with various combinations of antioxidants and vasodilators, including betahistine, vitamin E, and a combination of these agents, and salicylate, vitamin E, and a combination of these agents (see also Miller et al., 2006b). However, we found no evidence for additive effects (see Figure 10).

Figure 9.

A. Treatment with an iron chelator (deferoxamine mesylate, DFO), an antioxidant (mannitol, a hydroxyl scavenger), or a combination of these agents (with or without the neurotrophic factor GDNF) reduced NIHL (average hearing loss at 4, 8, and 16 kHz, mean ± SE, adapted from Yamasoba et al., 1999). Protection via DFO was statistically reliable at 16 kHz but not 4 or 8 kHz. Protection via mannitol was statistically reliable at 4 kHz but not 8 or 16 kHz. The combination of DFO + mannitol did not result in statistically reliable reduction of NIHL at 4, 8, or 16 kHz. The combination of DFO + mannitol + GDNF resulted in statistically reliable protection against NIHL at all of the test frequencies (see asterisk). Panel A reprinted from Miller et al. (2006b). Figure 9B. Although the reliability of threshold protection varied across agents, reductions in outer hair cell loss between 7.6 and 19.0 mm from the apex of the cochlea were statistically reliable for each of the individual agents as well as the combinations of agents (see asterisks). Average outer hair cell loss in rows 1–3 (mean ± SE) is illustrated. Panel B adapted from Yamasoba et al. (1999).

Figure 10.

Syergistic interactions among agents, while likely, have been challenging to identify. Treatment with antioxidants (salicylate: N=6 ears from 6 animals; Trolox, a synthetic analogue of vitamin E: N=10 ears from 5 animals), a vasodilator (betahistine: N=8 ears from 4 animals), or combinations of these agents (N=8 ears from 4 animals for each combination) reduced NIHL relative to controls (N=28 ears from 18 animals), with no additive effects observed with combinations of these agents. Given the small numbers of animals in some groups, statistical reliability of observed differences in NIHL was not evaluated. Average hearing loss at 4, 8, and 16 kHz (mean ± SE) is illustrated, reprinted from Miller et al. (2006b).

An alternative group of agents that has not yet been evaluated in sufficient detail includes agents that enhance cellular energy stores. For example, creatine kinase is a key enzyme involved in regulating energy metabolism in cells with intermittently high and fluctuating energy requirements (Dolder et al., 2001; Weiss et al., 2005), including the inner ear (Spicer and Schulte, 1992). If energy impairment plays a critical role in NIHL, then compounds that increase cochlear energy reserves would be expected to be protective. Dietary creatine (3% of total diet) did in fact reduce NIHL in a recent study (Minami et al., 2005; 2006). This protective effect was presumably mediated through the effects of creatine on adenosine tri-phosphate (ATP), as ATP infusion also reduces NIHL (Sugahara et al., 2004). When the individual and combined effects of the cellular energy enhancer creatine plus the free radical scavenger tempol were compared to the single agents delivered alone, additive effects were observed at 16 kHz, but not 4 or 8 kHz (Minami et al., 2005; 2006).

The identification of specific combinations of agents that act in additive and/or synergistic (i.e., multiplicative) ways is a compelling goal for future research activities. Because activation of calcineurin depends on ROS production and ROS-induced deficits in calcium homeostasis (Huang et al., 2001; Gooch et al., 2004; Kalivendi et al., 2005; Rivera and Maxwell, 2005), one might predict that blocking early ROS production would reduce activation of the calcineurin-initiated apoptotic pathway. If so, pre-treatment with antioxidant agents that are highly efficient OH scavengers, in combination with FK506 to directly intervene in the calcineurin pathway, might more effectively reduce NIHL and noise-induced cell death. This hypothesis has not been directly tested; and identification of the most effective combinations remains a challenge for future research efforts.

Summary

NIHL is a significant clinical issue; reducing the number of individuals afflicted would have broad economic and humanitarian benefit. We now know many of the pathways to cell death initiated by noise, and other environmentally mediated trauma, such as aminoglycoside antibiotics, and chemotherapeutics, as well as the process of aging. Interventions can be directed at preventing initial ROS formation, maintaining cochlear blood flow, restoring calcium balance in cells and in neurons, preventing calcineurin activation and/or caspase formation, or preventing the late forming ROS and RNS species that appear 7 to 10 days post noise. Interventions, including antioxidant agents, vasodilators, NTFs, steroids, calcineurin inhibitors, caspase inhibitors, JNK inhibitors, and Src protein tyrosine kinase (Src-PTK) inhibitors (Harris et al., 2005) have all been shown at least partially effective in prevention of auditory deficits, including hearing loss and hair cell death. Given the various points of intervention along the cell death pathways, there are an abundance of potential therapeutic targets. The most effective strategy may include targeting initiating events and early molecular processes, thus maintaining a cell in a relatively ‘normal’ physiological state. Although additional pre-clinical investigation is essential to the task of defining the most effective combination of agents, we can no longer delay the initiation of systematic human clinical trials to demonstrate the potential for treatment of the inner ear in man via agents currently known to be safe for human use.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by the National Institutes of Health (NIH-NIDCD R01 DC004058 and P30 DC005188), the General Motors Corporation/United Automotive Workers Union, and the Ruth and Lynn Townsend Professor of Communication Disorders. We thank Dr. Kevin Ohlemiller for helpful suggestions on an earlier version of this manuscript, and Drs. Richard Altschuler, Jochen Schacht, Yoshi Ohinata, and Fumi Shoji, as well as Alice Mitchell and Diane Prieskorn, for their contributions to these studies.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Literature Cited

- Adelman SF, Howett MK, Rapp F. Protease inhibitors suppress fibrinolytic activity of herpesvirus-transformed cells. J Gen Virol. 1982;60:15–24. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-60-1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agostinho P, Oliveira CR. Involvement of calcineurin in the neurotoxic effects induced by amyloid-beta and prion peptides. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:1189–1196. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn JH, Kang HH, Kim YJ, Chung JW. Anti-apoptotic role of retinoic acid in the inner ear of noise-exposed mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;335:485–490. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.07.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam SA, Ikeda K, Oshima T, Suzuki M, Kawase T, Kikuchi T, Takasaka T. Cisplatin-induced apoptotic cell death in Mongolian gerbil cochlea. Hear Res. 2000;141:28–38. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam SA, Oshima T, Suzuki M, Kawase T, Takasaka T, Ikeda K. The expression of apoptosis-related proteins in the aged cochlea of Mongolian gerbils. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:528–534. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200103000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida S, Domingues A, Rodrigues L, Oliveira CR, Rego AC. FK506 prevents mitochondrial-dependent apoptotic cell death induced by 3-nitropropionic acid in rat primary cortical cultures. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;17:435–444. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altura BM, Altura BT, Gebrewold A, Ising H, Gunther T. Noise-induced hypertension and magnesium in rats: relationship to microcirculation and calcium. J Appl Physiol. 1992;72:194–202. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1992.72.1.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aminpour S, Tinling SP, Brodie HA. Role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in sensorineural hearing loss after bacterial meningitis. Otol Neurotol. 2005;26:602–609. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000178121.28365.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attias J, Weisz G, Almog S, Shahar A, Wiener M, Joachims Z, Netzer A, Ising H, Rebentisch E, Guenther T. Oral magnesium intake reduces permanent hearing loss induced by noise exposure. Am J Otolaryngol. 1994;15:26–32. doi: 10.1016/0196-0709(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attias J, Bresloff I, Haupt H, Scheibe F, Ising H. Preventing noise induced otoacoustic emission loss by increasing magnesium (Mg2+) intake in guinea-pigs. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol. 2003;14:119–136. doi: 10.1515/jbcpp.2003.14.2.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attias J, Sapir S, Bresloff I, Reshef-Haran I, Ising H. Reduction in noise-induced temporary threshold shift in humans following oral magnesium intake. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Health Sci. 2004;29:635–641. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.2004.00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelsson A, Vertes D. Histological findings in cochlear vessels after noise. In: Hamernik R, Anderson D, Salvi R, editors. New Perspectives in Noise-Induced Hearing Loss. Raven; New York: 1981. pp. 49–68. [Google Scholar]

- Axelsson A, Dengerink H. The effects of noise on histological measures of the cochlear vasculature and red blood cells: a review. Hear Res. 1987;31:183–191. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(87)90125-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badalamente MA, Hurst LC, Stracher A. Localization and inhibition of calcium-activated neutral protease (CANP) in primate skeletal muscle and peripheral nerve. Exp Neurol. 1987;98:357–369. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(87)90248-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badalamente MA, Hurst LC, Stracher A. Neuromuscular recovery using calcium protease inhibition after median nerve repair in primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5983–5987. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badalamente MA, Hurst LC, Stracher A. Recovery after delayed nerve repair: influence of a pharmacologic adjunct in a primate model. J Reconstr Microsurg. 1992;8:391–397. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1006724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badalamente MA, Hurst LC, Stracher A. Neuromuscular recovery after peripheral nerve repair: effects of an orally-administered peptide in a primate model. J Reconstr Microsurg. 1995;11:429–437. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1006557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PJ, Adcock I. Anti-inflammatory actions of steroids: molecular mechanisms. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1993;14:436–441. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(93)90184-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthier A, Lemaire-Ewing S, Prunet C, Monier S, Athias A, Bessede G, Pais de Barros JP, Laubriet A, Gambert P, Lizard G, Neel D. Involvement of a calcium-dependent dephosphorylation of BAD associated with the localization of Trpc-1 within lipid rafts in 7-ketocholesterol-induced THP-1 cell apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:897–905. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolaso L, Martini A, Bindini D, Lanzoni I, Parmeggiani A, Vitali C, Kalinec G, Kalinec F, Capitani S, Previati M. Apoptosis in the OC-k3 immortalized cell line treated with different agents. Audiology. 2001;40:327–335. doi: 10.3109/00206090109073130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biesalski HK, Wellner U, Weiser H. Vitamin A deficiency increases noise susceptibility in guinea pigs. J Nutr. 1990;120:726–737. doi: 10.1093/jn/120.7.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas G, Guha M, Avadhani NG. Mitochondria-to-nucleus stress signaling in mammalian cells: nature of nuclear gene targets, transcription regulation, and induced resistance to apoptosis. Gene. 2005;354:132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas RS, Cha HJ, Hardwick JM, Srivastava RK. Inhibition of drug-induced Fas ligand transcription and apoptosis by Bcl-XL. Mol Cell Biochem. 2001;225:7–20. doi: 10.1023/a:1012203110027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohne BA, Harding GW. Neural regeneration in the noise-damaged chinchilla cochlea. Laryngoscope. 1992;102:693–703. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199206000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohne BA, Harding GW, Nordmann AS, Tseng CJ, Liang GE, Bahadori RS. Survival-fixation of the cochlea: a technique for following time-dependent degeneration and repair in noise-exposed chinchillas. Hear Res. 1999;134:163–178. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branis M, Burda H. Effect of ascorbic acid on the numerical hair cell loss in noise exposed guinea pigs. Hear Res. 1988;33:137–140. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(88)90026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KC, Rybak LP, Meech RP, Hughes L. D-methionine provides excellent protection from cisplatin ototoxicity in the rat. Hear Res. 1996;102:90–98. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(96)00152-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KC, Meech RP, Rybak LP, Hughes LF. D-Methionine protects against cisplatin damage to the stria vascularis. Hear Res. 1999;138:13–28. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(99)00142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KC. Ototoxicity: Understanding oxidative mechansims. J Am Acad Audiol. 2003;14:121–123. doi: 10.3766/jaaa.14.3.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell KC, Meech RP, Rybak LP, Hughes LF. The effect of D-methionine on cochlear oxidative state with and without cisplatin administration: mechanisms of otoprotection. J Am Acad Audiol. 2003;14:144–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso SM, Oliveira CR. The role of calcineurin in amyloid-beta-peptides-mediated cell death. Brain Res. 2005:19. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.04.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caro AA, Cederbaum AI. Role of phospholipase A2 activation and calcium in CYP2E1-dependent toxicity in HepG2 cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:33866–33877. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300408200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassandro E, Sequino L, Mondola P, Attanasio G, Barbara M, Filipo R. Effect of superoxide dismutase and allopurinol on impulse noise-exposed guinea pigs--electrophysiological and biochemical study. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh) 2003;123:802–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cevette MJ, Vormann J, Franz K. Magnesium and hearing. J Am Acad Audiol. 2003;14:202–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YS, Tseng FY, Liu TC, Lin-Shiau SY, Hsu CJ. Involvement of nitric oxide generation in noise-induced temporary threshold shift in guinea pigs. Hear Res. 2005;203:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng AG, Huang T, Stracher A, Kim A, Liu W, Malgrange B, Lefebvre PP, Schulman A, Van De Water TR. Calpain inhibitors protect auditory sensory cells from hypoxia and neurotrophin-withdrawal induced apoptosis. Brain Res. 1999;850:234–243. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01983-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng AG, Cunningham LL, Rubel EW. Mechanisms of hair cell death and protection. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;13:343–348. doi: 10.1097/01.moo.0000186799.45377.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chole RA, Quick CA. Temporal bone histopathology in experimental hypovitaminosis A. Laryngoscope. 1976;86:445–453. doi: 10.1288/00005537-197603000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong ZZ, Kang JQ, Maiese K. Essential cellular regulatory elements of oxidative stress in early and late phases of apoptosis in the central nervous system. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2004;6:277–287. doi: 10.1089/152308604322899341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christians U, Gottschalk S, Miljus J, Hainz C, Benet LZ, Leibfritz D, Serkova N. Alterations in glucose metabolism by cyclosporine in rat brain slices link to oxidative stress: interactions with mTOR inhibitors. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;143:388–396. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claes J, Van de Heyning PH. A review of medical treatment for Meniere’s disease. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl (Stockh) 2000;544:34–39. doi: 10.1080/000164800750044461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbacella E, Lanzoni I, Ding D, Previati M, Salvi R. Minocycline attenuates gentamicin induced hair cell loss in neonatal cochlear cultures. Hear Res. 2004;197:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle JT, Puttfarcken P. Oxidative stress, glutamate, and neurodegenerative disorders. Science. 1993;262:689–695. doi: 10.1126/science.7901908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham LL, Cheng AG, Rubel EW. Caspase activation in hair cells of the mouse utricle exposed to neomycin. J Neurosci. 2002;22:8532–8540. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-19-08532.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]