Abstract

The molecular identity of platelet Ca2+ entry pathways is controversial. Furthermore, the extent to which Ca2+-permeable ion channels are functional in these tiny, anucleate cells is difficult to assess by direct electrophysiological measurements. Recent work has highlighted how the primary megakaryocyte represents a bona fide surrogate for studies of platelet signalling, including patch clamp recordings of ionic conductances. We have now screened for all known members of the transient receptor potential (TRP) family of non-selective cation channels in murine megakaryocytes following individual selection of these rare marrow cells using glass micropipettes. RT-PCR detected messages for TRPC6 and TRPC1, which have been reported in platelets and megakaryocytic cell lines, and TRPM1, TRPM2 and TRPM7, which to date have not been demonstrated in cells of megakaryocytic/platelet lineage. Electrophysiological recordings demonstrated the presence of functional TRPM7, a constitutively active cation channel sensitive to intracellular Mg2+, and TRPM2, an ADP-ribose-dependent cation channel activated by oxidative stress. In addition, the electrophysiological and pharmacological properties of the non-selective cation channels stimulated by the physiological agonist ADP are consistent with a major role for TRPC6 in this G-protein-coupled receptor-dependent Ca2+ influx pathway. This study defines for the first time the principal TRP channels within the primary megakaryocyte, which represent candidates for Ca2+ influx pathways activated by a diverse range of stimuli in the platelet and megakaryocyte.

Ion channels play fundamental roles in all cell types, from regulation of cellular homeostasis to signal transduction, and thus represent key targets for therapeutic intervention. The ion channel phenotype of the mammalian platelet has proven difficult to study using direct electrophysiological techniques due to its small and fragile nature (Mahaut-Smith, 2004; Mahaut-Smith et al. 2004). Although RT-PCR of messages for platelet ion channels has been reported, this approach is complicated by the low levels of mRNA compared to other blood cell types and the possibility that platelet mRNA may be partially degraded. An alternative strategy to identifying platelet proteins is proteomics; however, current technology focuses on proteins of high density and ion channels may only be required in small numbers to serve their specific function. Other protein detection techniques such as Western blotting and immunohistochemistry are crucially dependent upon the specificity of the antibody, which is frequently questioned. An additional issue is that proteomics and antibody-dependent techniques only detect the presence of a protein and not the extent to which it is functional.

Several groups have recognized that mature, primary megakaryocytes (MKs) express most, if not all, platelet proteins and that these MK proteins are able to participate in major platelet functional responses such as agonist-dependent activation of high affinity fibrinogen binding sites on the αIIbβ3 integrin (Bobe et al. 2001; Eto et al. 2002; Tolhurst et al. 2005). In contrast to the platelet, direct electrophysiological studies of primary megakaryocytes have been reported by multiple laboratories (reviewed in (Mahaut-Smith, 2004; Mahaut-Smith et al. 2004). Indeed, patch clamp studies of MKs were crucial in the identification of P2X1 as the sole ionotropic receptor underlying ATP-evoked Ca2+ influx in the platelet (Mahaut-Smith et al. 2004). Mammalian homologues of the Drosophila transient receptor potential (TRP) ion channel constitute a major family of cation channels that has received considerable attention in recent years. The original role considered for these cation channels was in agonist-evoked Ca2+ influx; however, they are now recognized to be controlled by multiple modalities, including for example membrane lipids and mechanical forces, and to play non-redundant roles in cell viability (Montell, 2005). In addition, some members of the TRPM family possess both enzymatic and ion conducting properties (Fleig & Penner, 2004; Harteneck, 2005). TRP channels are arranged into six loosely related protein groups, TRPC, TRPV, TRPM, TRPP, TRPA and TRPML. To date, a number of TRPC messages have been described in platelets and immortalized cell lines of megakaryocyte origin (Berg et al. 1997; den Dekker et al. 2001; Hassock et al. 2002; Brownlow & Sage, 2005); however, their level of expression, subcellular membrane location and contribution to agonist-evoked Ca2+ signalling are highly controversial issues (Sage et al. 2002). In addition, immortalized megakaryocytic cell lines display significantly altered ion channel phenotypes and greatly reduced levels of functional platelet responses compared to the primary MK (Kapural et al. 1995; Mahaut-Smith, 2004; Kashiwagi et al. 2004). No study has characterized TRP channels in the primary megakaryocyte; however, their isolation represents a significant challenge since they constitute < 1% of all marrow cells. In the present work, we have assessed the TRP channel complement of the murine megakaryocyte using a combination of patch clamp and RT-PCR from cells collected individually from the marrow. Messages for five Ca2+-permeable members of this channel superfamily were detected, with the strongest signals for TRPC6 and TRPM7 mRNA, and the largest conductance in electrophysiological recordings observed for TRPM2.

Methods

Reagents and solutions

Standard Hepes-buffered saline (HBS) contained (mm): 145 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 10 Hepes, 10 glucose, pH 7.35 (NaOH). Salines for patch clamp recordings were designed to eliminate K+ currents; the external medium consisted of HBS in which KCl was replaced by an equal concentration of NaCl and the internal saline contained (mm): 150 CsCl, 2 MgCl2 10 Hepes, 10 glucose, 0.05 Na2GTP, 0.05 K5fura-2, 0.1 EGTA pH 7.2 (CsOH). The Mg2+ content of the internal saline was modified by addition or removal of MgCl2 without substitution. A mixture of 1 mm EGTA and 0.88 mm CaCl2 was used in the pipette saline to clamp the intracellular Ca2+ concentration at 1 μm. Solutions used for megakaryocyte enrichment have been described in detail elsewhere (Leven, 2004). Briefly, 10× calcium- and magnesium-free Hank's salt solution (CMFH) contained (mm): 53.7 KCl, 4.4 KH2PO4, 1370 NaCl, 41.7 NaHCO3, 3.38 Na2HPO4 and 55.6 glucose, pH 7.4 (NaOH); CATCH buffer was 1× CMFH with 12.9 mm sodium citrate, 1.4 mm adenosine, 2.7 mm theophylline, pH 7.4 with NaOH. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) stock solution was made by combining 200 ml water, 15.5 ml 10× CMFH, 58 g BSA, 97.2 mg adenosine and 128.4 mg theophyilline, pH 7.4 with NaOH, and was diluted in CATCH buffer for unit velocity gradients. All solutions were sterilized by filtration. Qiagen Ltd (Crawley, UK) supplied all molecular biology reagents and kits, unless otherwise stated. Anti-CD41-FITC antibody was from Pharmingen International (NJ, USA). All other reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich (Poole, UK).

Preparation of tissue samples

Male C57/Bl6 mice aged between 14 and 16 weeks old were killed by CO2 asphyxiation and cervical dislocation in accordance with UK legislation. Marrow was gently flushed from the lumen of the femoral and tibial bones using one of the following solutions: sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (Cambrex, Wokingham, UK) with 0.32 U ml−1 type VII apyrase for RT-PCR from manually extracted megakaryocytes, HBS with 0.32 U ml−1 type VII apyrase for electrophysiological experiments or CATCH with 3.5% BSA, 0.32 U ml−1 apyrase VII and 1 μg ml−1 PGE1 for megakaryocyte purification by unit velocity gradient and flow cytometry. Control tissues (brain, eye and kidney) were individually removed, washed in PBS, flash frozen in liquid N2, ground using a mortar and pestle and added to lysis buffer. All samples were homogenized and passed through a 21-g hypodermic needle.

Isolation of individual megakaryocytes

Individual MKs were manually extracted for RT-PCR by adapting the approach used for electrophysiological recordings from these rare marrow cells (Mahaut-Smith, 2004). Thin-walled filamented borosilicate glass capillaries (Harvard Apparatus, Edenbridge, UK) were sterilized, pulled on a DMZ Universal puller (Zeitz Instruments GmbH Ltd, Munich, Germany) and fire-polished to a final internal tip diameter in the range 10–25 μm. Pipettes were mounted in a patch pipette holder with side-port (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA) to allow control of intrapipette pressure and were manipulated using a motorized micromanipulator (Luigs & Neumann, Ratingen, Germany) under 400× magnification. An aliquot of marrow cell suspension was placed in an electrophysiological-style chamber containing PBS, allowed to settle and perfused with PBS for several minutes. Positive pressure applied to the pipette prior to approaching the marrow cells ensured that only selected cells entered the pipette tip. Individual MKs with diameters greater than 15 μm and free from attached or emperipolesed smaller cells were ‘clamped’ in the end of a micropipette tip, selected to have an internal tip diameter ∼5–15 μm smaller than the cell, using gentle suction. Control experiments showed that with an appropriate level of suction, the tip of the glass pipette could repeatedly cross the air–saline interface without dislodging the attached MK, thereby allowing individual MKs to be transferred to an Eppendorf tube containing lysis buffer with 0.05 ng ml−1 poly-A carrier RNA (Qiagen) for RT-PCR. Multiple smaller marrow cells were extracted by suction into individual micropipettes whilst avoiding MKs.

Sorting of CD41+ cells by flow cytometry

Following extraction, marrow was gently triturated and filtered through 100 μm pore nylon mesh (Cadisch Precision Meshes Ltd, London, UK). The resulting cell suspension was centrifuged at 1000 r.p.m. for 5 min, re-suspended in 1 ml CATCH, and MKs enriched by passing through two successive BSA unit velocity (1 g) gradients. The BSA gradients were prepared as previously described (Leven, 2004); briefly they consisted of 3.6 ml stock BSA overlaid with 1.8 ml of 2: 1 (v/v) stock BSA:CATCH followed by 1.8 ml of 1: 2 (v/v) stock BSA:CATCH and the 1 ml marrow suspension layered on top. After 30 min at room temperature, the top 4 ml of the gradient was discarded. The remainder was centrifuged at 1000 r.p.m. for 5 min and re-suspended in 1 ml CATCH after the first gradient, and CATCH containing 2 mm EGTA, 0.32 U ml−1 apyrase VII and 1 μg ml−1 PGE1 after the second gradient. FITC-conjugated CD41 (1: 250 dilution) was added for 1 h at room temperature. After passing through a 75 μm pore filter, the sample was analysed on a Dako MoFlo™ MLS flow cytometer (Dako UK Ltd, Ely, UK) using a pressure setting of 10 p.s.i. and a 200 μm nozzle. A sample of gated cells was collected to check the validity of the sort. Once confirmed, the high purify sort mode was used to separate cells into a 96 well plate for imaging, or a sterile Eppendorf tube containing lysis buffer with 0.05 ng ml−1 poly-A carrier RNA for RT-PCR.

Imaging of megakaryocyte enrichment

Samples collected in 96 well plates were imaged using a Zeiss LSM 510 (Carl Zeiss Ltd, Welwyn Garden City, UK) with plan-neofluar 10× (0.30 NA) and 20× (0.50 NA) objectives. Confocal fluorescence imaging of CD41+ cells used excitation and emission wavelengths of 488 and > 505 nm, respectively.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was collected from MKs using the RNeasy micro kit (Qiagen) with on-column DNase digestion, according to the manufacturer's instructions. Whole tissue control RNA was isolated using an RNeasy mini kit and further treated with DNAse I (Ambion (Europe) Ltd, Huntingdon, UK) to reduce contaminating genomic DNA. First strand cDNA was synthesized from total RNA by reverse transcription with oligo-(dT) primer (Promega, Southampton, UK) using Omniscript (whole tissues) or Sensiscript (mo-flo/single cell) reverse transcriptase according to the manufacturer's protocol. The reaction contained: 20% RNA sample, 1 × buffer, 0.5 mm dNTPs, 0.5 U μl−1 RNasin ribonuclease inhibitor (Promega, Southampton, UK), 1 μm oligo(dT) primer and 0.2 U μl−1 reverse transcriptase. The mixture was incubated for 1 h at 37°C. PCR primer sequences were based on GenBank entries using Primo Pro (http://www.changbioscience.com/primo/primo.html) and were designed to generate PCR products of different amplicon sizes that overlapped introns to eliminate contribution from residual genomic DNA. The standard PCR reaction contained 10% RT product, 1× buffer containing 1.5 mm MgCl2, 0.2 mm dNTPs, 0.5 μm forward and reverse primer (Sigma-Genosys, UK) and 0.06 U μl−1Taq DNA polymerase. Amplification was carried out on a Mastercycler gradient (Eppendorf, Germany) using an initial step of 95°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles (CD41+ cells or whole tissue samples) or 45 cycles (individually collected cells) of 95°C, 30 s denaturation, 30 s annealing and 72°C extension followed by a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min. To further assess the presence of weaker TRPC messages in CD41+ cells (Fig. 2), a further 25 identical PCR cycles were conducted with one-tenth PCR product. Specific primer sequences, annealing temperatures and extension times are described in online Supplemental material. PCR products were visualized in a 2% agarose gel prestained with 0.5 μg ml−1 ethidium bromide using a 1000 bp ladder (Bioline, London, UK) to assess amplicon sizes. The identity of PCR products was confirmed by dideoxy sequencing (Department of Genetics, University of Cambridge).

Figure 2. Purified populations of CD41+ primary megakaryocytes show messages for TRPC1 and TRPC6, but not other TRPC channels.

A, megakaryocytes in murine marrow (initial) were enriched using two unit velocity gradients (gradients 1 and 2), then labelled with a FITC-conjugated CD41 antibody (before sorting, CD41+), and separated by flow cytometry (after sorting, CD41+). R1 in the scatter plot shows the gate used to collect cells with high forward scatter and high fluorescence. Scale bars 50 μm. B, screen of TRPC transcripts in purified CD41+ samples detected only TRPC6 and TRPC1. PCR products are shown for each TRPC primer pair from brain (B, 35 cycles) or CD41+ cells (M, 2 rounds of PCR of 35 and 25 cycles). Of the transcripts obtained for TRPC1, the strongest signal was at 213 bp, as expected for the full length sequence and previously reported variants; a weaker signal was observed at 192 bp. A third product, slightly longer than the full length sequence, was also observed; however, sequencing failed to distinguish this from the other amplicons.

Electrophysiology

Conventional whole-cell patch clamp recordings were carried out using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA) in voltage clamp mode as described in detail elsewhere (Mahaut-Smith, 2004; Tolhurst et al. 2005). Voltage ramps of 300 ms duration ranging from −80 to +80 mV were applied from a holding potential of −70 mV at a frequency of 0.2 Hz for TRPM7 studies or under manual timing in other experiments. Membrane currents were filtered at 1 kHz and acquired to computer at a rate of 5 kHz using a Digidata 1200 series A/D converter. All experiments were carried out at room temperature. Data were analysed using Clampfit v9.0 (Axon Instruments) and exported for presentation in Microcal Origin (OriginLabCorp., Northampton, MA, USA).

Results

RT-PCR from individually collected megakaryocytes

RT-PCR from individual marrow MKs represents a potentially important approach to screen for proteins with a proposed role in megakaryocytopoiesis or platelet function since contamination from other cell types can be eliminated. To assess this method for the detection of Ca2+-permeable ion channels, we used sequence-specific primers for TRPC6, which has been reported in human platelets and TRPM7, which has been suggested to be ubiquitously expressed but to date not demonstrated in cells of platelet/MK lineage. A weak signal for TRPM7 could be detected after 45 rounds of PCR using material from a single MK and a strong signal for both TRPC6 and TRPM7 was obtained when four MKs were combined (Fig. 1A). The absence of PCR product when a sample of bath saline or ∼50 non-megakaryocytic cells were transferred to lysis buffer confirmed that the TRPM7 and TRPC6 messages detected for the MK were not the result of contamination by mRNA released into the extracellular environment or from other marrow cells. The high ploidy and thus amplified mRNA production of the MK (Raslova et al. 2003) most likely accounts for the ability to detect ubiquitously expressed TRPM7 in small numbers of MKs under conditions where the signal for this channel is below the limit of resolution in a sample of ∼50 small marrow cells. It was also interesting to note that no signal was observed in MKs which displayed a ‘transparent’ state (see cell labelled ‘T’ in Fig. 1B and also Mahaut-Smith, 2004). The precise status of these cells is unknown; however, one can more clearly see the polyploidic nucleus and organellar membranes and they stain more rapidly with the double stranded DNA stain Hoescht (not shown) compared to normal, intact MKs (labelled ‘I’ in Fig. 1B). This suggests that the plasma membrane integrity of these transparent MKs has been compromised and that they represent damaged cells rather than MKs undergoing thrombopoiesis. Therefore, only normal, intact megakaryocytes were manually extracted for RT-PCR experiments.

Figure 1. RT-PCR detection of transient receptor potential ion channels from individually collected primary megakaryocytes.

mRNA from individually collected megakaryocytes or small non-megakaryocytic cells, whole brain or whole marrow was reverse transcribed and screened for specific TRP channel amplicons by PCR: 35 rounds for brain and marrow and 45 rounds for all other samples. A, gel electrophoresis analysis of PCR products with-gene specific primers for either TRPM7 or TRPC6. TRPM7 was just detectable after 45 PCR cycles in material from a single intact megakaryocyte, whereas a strong signal was detected for both TRPC6 and TRPM7 when 4 intact megakaryocytes were combined. No signal was detected for ∼50 non-megakaryocytic cells, 2 ‘transparent’ megakaryocytes or the bath saline control. In other experiments no PCR signal was detected for B-actin in samples of up to 10 transparent MKs (Richard Carter, unpublished observations). B, image of marrow cells showing a normal intact megakaryocyte (I) and a transparent megakaryocyte (T). Scale bar 20 μm. C, RT-PCR screen (45 cycles) detected transcripts for TRPM1, TRPM2, TRPM7, TRPC6 and TRPC1 or a splice variant of TRPC1. TRPC1 (213 bp) and the TRPC1 splice variant (192 bp) were detected in different MK samples. Samples are representative of results from 13 to 15 MKs (TRPM1, M2, M7 and C6) or 30 MKs (TRPC1).

TRP channel screening

To screen for TRP channel transcripts, we combined material from up to 30 intact MKs to allow detection of weaker signals compared to TRPM7 and TRPC6. Of all 28 known mammalian TRP channels within six families (see Supplementary material with details of primers and control tissues), we consistently detected messages for five different isoforms in the MK; TRPC1 (including a splice variant, see below), TRPC6, TRPM1, TRPM2 and TRPM7 (Fig. 1C). TRPC6 and TRPM7 always gave the strongest signals, and full length TRPC1 or its splice variant the weakest. The TRPC1 primers were designed so that they would detect both the full length transcript and the three splice variants previously reported (Sakura & Ashcroft, 1997), one of which has been detected in platelets and megakaryocytic cell lines (den Dekker et al. 2001). In addition to the amplicon (213 bp) expected for this primer pair, primary MKs showed a further TRPC1 splice variant (192 bp), which lacked 21 base pairs in exon 5. This variant has been described in the eye (BI735532) by the National Institutes of Health, Mammalian Gene Collection (MGC) http://mgc.nci.nih.gov/. Figure 1C shows a sample in which only this new variant was detected; however, in other samples only the TRPC1 amplicon expected for the full length product or previously reported variants (213 bp amplicon) was detected (not shown, but see results below for CD41+ cells).

Other studies have suggested that human platelets express additional TRPC channels on the basis of RT-PCR (TRPC4) (den Dekker et al. 2001) or Western blotting (TRPC3, 4 and 5) (Brownlow & Sage, 2005), and thus we considered that these may have been below the level of detection in our samples of up to 30 MKs. Therefore, we also conducted RT-PCR on a larger collection of primary MKs. MKs were initially enriched by two successive BSA unit velocity gradients and then purified by flow cytometric sorting of CD41+ cells (Fig. 2A). Cells displaying both high fluorescence and high forward scatter (gate R1 in the scatter plot of Fig. 2A) provided samples with > 98% large diameter CD41+ cells with intact plasma membranes. Cells with high fluorescence and low forward scatter, that is to the left of gate R1 Fig. 2A, consisted mainly of MKs in a ‘transparent’ state (see above and Fig. 1B), thus were avoided. In the large diameter CD41+ cells from gate R1, we again detected messages for the 5 full length TRP channels (TRPC1, TRPC6, TRPM1, TRPM2, TRPM7), and the TRPC1192 bp variant, that were observed at the single cell level. However, of the TRPC family members, only TRPC1 and TRPC6 were detected in purified CD41+ cells, even after an additional 25 rounds of PCR (n = 3; sample size 1000–2000 cells; Fig. 2B).

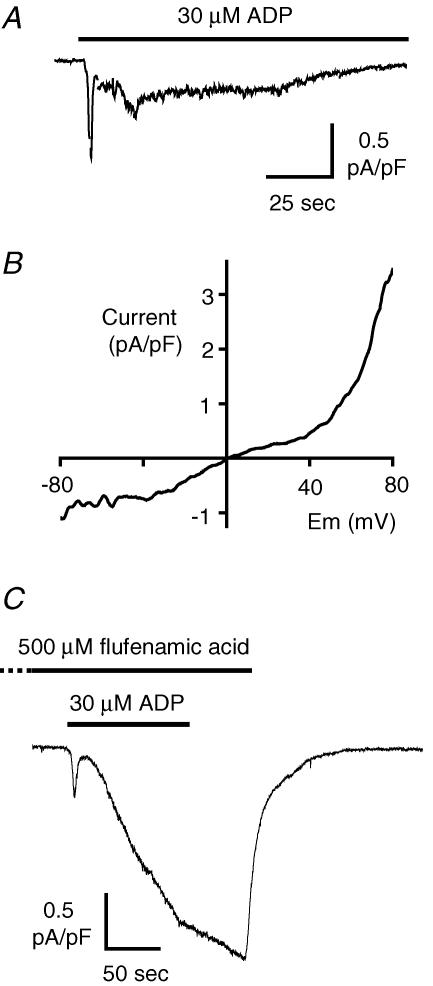

A major role for TRPC6 in the ADP-evoked inward cation currents

In whole-cell patch clamp recordings from murine megakaryocytes, ADP rapidly activates a non-selective cation channel (Fig. 3A), which we have recently shown to conduct both Na+ and Ca2+ into the cell at normal membrane potentials (Tolhurst et al. 2005). Phospholipase-Cβ-coupled P2Y1 receptors are required for activation of this conductance by ADP, with an amplifying role for PI-3 kinase-coupled P2Y12 receptors (Tolhurst et al. 2005). The molecular identity of the P2Y1/P2Y12-dependent conductance in the primary megakaryocyte is unknown; however, it would be expected to be either TRPC1 or TRPC6 based on the results of the above molecular screening and the known ability of this ‘canonical’ family of non-selective cation channels to be gated by phospholipase-C-coupled receptors (Montell, 2005). Under divalent cation levels similar to those used in our study, TRPC1 displays a linear current–voltage (I–V) relationship (Zitt et al. 1996; Sinkins et al. 1998). In contrast, the I–V relationship for TRPC6 shows strong outward rectification at potentials positive to ∼30 mV, weaker inward rectification at potentials slightly negative to the reversal potential and in some studies a region of reduced slope at potentials more negative than −40 mV (Hofmann et al. 1999; Inoue et al. 2001; Jung et al. 2002). In voltage ramp protocols the MK ADP-evoked conductance displayed an I–V relationship typical of TRPC6, which has been described as ‘S-shaped with outward rectification’ (Inoue et al. 2001) (Fig. 3B, n = 6). Flufenamic acid is a general inhibitor of non-selective cation channels, including preparations where TRPC1 is predicted to be dominant (Popp et al. 1993); however, unusually it potentiates TRPC6 at 100–500 μm (Inoue et al. 2001; Jung et al. 2002). Application of flufenamic acid (100–500 μm) caused a 5.5-fold, reversible potentiation of the ADP-evoked current in MKs (peak values of 0.23 ± 0.09 and 1.26 ± 0.6 pA pF−1 for the sustained phase in control and flufenamic acid-treated, respectively, n = 4, Fig. 3C). Together with the results from the RT-PCR screen, these biophysical and pharmacological properties suggest a major role for TRPC6 in the cation influx conductance coupled to P2Y receptor activation.

Figure 3. Biophysical and pharmacological properties of the ADP-evoked non-selective cation conductance.

A, whole cell recording of the inward cation current activated at −70 mV by 30 μm ADP in salines designed to eliminate contaminating K+-selective currents (see Methods). Brief gaps in the recording correspond to application of a 300 ms duration voltage ramp from −80 to +80 mV, used to assess the current–voltage relationship. B, typical current–voltage relationship for the ADP-evoked conductance obtained by subtracting the background current in the absence of agonist from the ADP-evoked current. C, typical recording showing the potentiation of the ADP-evoked current by 500 μm flufenamic acid (applied for 2 min prior to ADP).

ADP-ribose-activated currents of large amplitude and complex kinetics indicate a role for TRPM2 as a cation influx pathway in the megakaryocyte

We next used patch clamp recordings to examine the extent to which TRPM channels detected by RT-PCR are functional in the MK. This is difficult for TRPM1 channels as their electrophysiological properties have not been described (Fleig & Penner, 2004; Harteneck, 2005). However, a hallmark of TRPM2 is its activation by the second messenger ADP-ribose, with a critical dependence upon elevated cytosolic Ca2+ (Perraud et al. 2001; Sano et al. 2001; McHugh et al. 2003). Inclusion of 1 mm ADP-ribose in the patch pipette with Ca2+ clamped at 1 μm activated a large inward membrane current at −70 mV (Fig. 4A), which was absent in control recordings with the same intrapipette Ca2+ level but without ADP-ribose (Fig. 4B). The I–V relationship of the ADP-ribose-induced current was linear, and reversed close to 0 mV, typical of TRPM2 in expression systems (Sano et al. 2001; Perraud et al. 2001) (Fig. 4C). The ADP ribose-activated current was also sensitive to clotrimazole (Fig. 4A), a known blocker of TRPM2 channels (Hill et al. 2004). The lack of complete block of the inward current by clotrimazole may result from a steady increase in background (‘leak’) current which tended to develop at high [Ca2+]i even in the absence of ADP-ribose (see Fig. 4B). Interestingly, the inward currents activated by ADP-ribose in these experiments were considerably larger than the P2Y receptor-activated non-selective conductance (see Fig. 3 and also previous studies; Tolhurst et al. 2005) or the Mg2+-inhibitable TRPM7 (see below). A further unexpected observation was the complex kinetics of the ADP-ribose-dependent current, as shown by the expanded sections of the trace (Fig. 4Ai and ii). In many cells, the ADP ribose-induced inward current displayed transient periods of activation of variable duration (range 0.26–19.3 s, n = 4, see Fig. 4Ai). In addition, as the blockade by clotrimazole developed, regular brief transient inward currents were detected (see expanded trace, Fig. 4Aii). The basis of these complex temporal patterns is unknown and requires further investigation; however, they were not the result of repetitive autocrine activation of P2X1 receptors (Tolhurst et al. 2005) as these experiments were conducted in the presence of the P2X1-selective inhibitor NF 449 (1 μm) (Horner et al. 2005; Tolhurst et al. 2005).

Figure 4. Characteristics of ADP ribose-evoked inward currents in whole-cell recordings.

Whole-cell patch clamp recordings at −70 mV (A and B) using conditions designed to block K+ currents (K+-free external and CsCl-based internal salines; see Methods) and P2X1 currents (1 μm NF 449; Horner et al. 2005). The [Ca2+]i was set to 1 μm using an EGTA:Ca2+ mixture. A, addition of 1 mm ADP-ribose to the patch pipette resulted in inward currents displaying large fluctuations of variable duration (see enlarged sections, i and ii) that were inhibited by 30 μm clotrimazole. B, only a small, slowly increasing background current was observed with high [Ca2+]i in the absence of ADP-ribose. C, 300 ms duration voltage ramps from −80 to 80 mV show the linear current–voltage relationship of the ADP-ribose induced current (reversal potential of ∼3 mV).

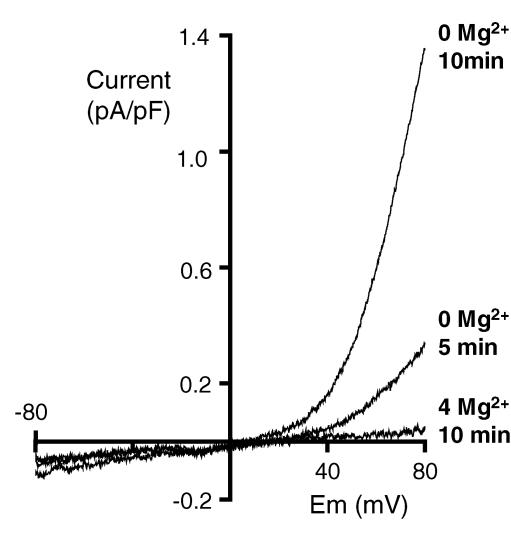

Mg2+-dependent TRPM7 membrane currents

We also looked for TRPM7 currents in whole cell recordings from MKs using the recognized dependence of this cation channel on intracellular Mg2+ (Nadler et al. 2001). In order to examine the development of non-selective cation currents during the early stages of dialysis, voltage-dependent K+ currents were abolished with 4-aminopyridine (2 mm in the external saline; J. Martinez-Pinna and M. P. Mahaut-Smith, unpublished observations). When the pipette contained 4 mm MgCl2, a concentration known to completely block TRPM7 (Nadler et al. 2001), the I–V relationship remained linear during whole-cell patch clamp recordings from unstimulated MKs (Fig. 5). However, when Mg2+ was omitted from the pipette, a current with pronounced outward rectification appeared in a time-dependent manner (n = 5, Fig. 5), as previously reported for TRPM7 in other cell types (Fleig & Penner, 2004). Thus, the megakaryocyte possesses constitutively active TRPM7 channels, a non-selective cation channel with roles in Mg2+ homeostasis and entry of trace metal ions (Fleig & Penner, 2004).

Figure 5. Intracellular Mg2+-dependent outwardly rectifying nonselective cation currents typical of TRPM7.

Conventional whole cell patch clamp recordings from unstimulated MKs dialysed with pipette salines designed to eliminate K+-selective currents and containing either 4 mm MgCl2 or no added MgCl2; 2 mm 4-amino pyridine was also included in the external saline to block voltage-gated K+ currents. Voltage ramps of 300 ms duration from −80 to +80 mV were applied every 5 s after obtaining the whole-cell mode. At other times the cell was held at −70 mV. Sample traces obtained after 5 and 10 min in the absence of internal Mg2+ show the development of an outwardly rectifying current that was not observed when 4 mm MgCl2 was included in the patch pipette (sample trace shown after 10 min).

Discussion

Mammalian homologues of the Drosophila TRP channel represent a major family of non-selective cation channels with diverse roles ranging from Mg2+ homeostasis, mechanotransduction, osmoregulation, motility, vasoconstriction, thermoregulation and pain detection (Montell, 2005). The relative expression of different TRP channels in the platelet has been the focus of only a few studies and remains highly controversial; furthermore it has proven difficult to confirm the activity of channels detected by RT-PCR or Western blot due to the technical constraints and signal limitations of electrophysiological recordings in the fragile and tiny mammalian platelet. The megakaryocyte has been used to clarify the properties of a number of ion channels known to exist in the platelet, such as P2X1, voltage- and calcium-gated potassium channels (Mahaut-Smith, 2004; Mahaut-Smith et al. 2004). We now show that an adaptation of the approach used to isolate MKs from bone marrow for patch clamp recordings provides a means to extract these rare cells for screening of ion channel messages. RT-PCR is widely used to detect transcripts at the single cell level and in theory should be more successful in the MK compared to other cells due to the uniquely high ploidy of the platelet precursor (Raslova et al. 2003). However, we opted to combine a number of cells (range 13–30) in our screen of TRP transcripts due to the intercellular heterogeneity of agonist-evoked currents observed in primary MKs (Tolhurst et al. 2005; Hussain & Mahaut-Smith, 1998). We detected transcripts for five different TRP channel isoforms (C1, C6, M1, M2, M7) at the level of the single MK, which were confirmed in samples from highly purified CD41+ cells. This larger selection of MKs also confirmed the absence of significant messages for other full length TRPC channels.

Although the RT-PCR results in our study are only semiquantitative, the considerably stronger signal for TRPC6 compared to TRPC1 is in agreement with the study by Hassock et al. (2002) in human platelets based on Western blotting. An RT-PCR study of human platelets (den Dekker et al. 2001) also agrees with our findings for TRPC channels, with the exception that a very weak TRPC4 transcript was also reported. The reason for the difference between these three independent reports for human or mouse platelets/MKs (den Dekker et al. 2001; Hassock et al. 2002; and the present study) and a recent study purporting the robust presence of TRPC3, 4 and 5 channels in human platelets using Western blotting, remains to be clarified (Brownlow & Sage, 2005). Nevertheless, when combined with the current–voltage relationship of the ADP-evoked current and its enhancement by flufenamic acid, our RT-PCR results are consistent with a major role for TRPC6 in the non-selective cation conductance activated by ADP in the platelet/MK. Activation of the ADP-evoked conductance in the MK requires Gq-coupled P2Y1 receptors, with a potentiating role for Gi-coupled P2Y12 receptors (Tolhurst et al. 2005), and therefore the same channel may contribute to cation influx following activation by other platelet agonists, many of which also signal through Gq- and/or Gi-linked receptors (Woulfe et al. 2004). The precise signal that activates agonist-evoked Ca2+ entry in the platelet and megakaryocyte is unclear, and has been proposed to include phosphinositide 4,5-bisphosphate depletion, an increase in PIP3 levels, Btk activation, cytoskeletal modulation and feedback by PLC products diacylglycerol and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (Somasundaram & Mahaut-Smith, 1994; Hussain & Mahaut-Smith, 1998; Pasquet et al. 2000; Hassock et al. 2002; Rosado & Sage 2000; Tseng et al. 2004; Tolhurst et al. 2005). Further studies are required to investigate the relative contribution of these signals in the activation of TRP channels and thus Ca2+ entry in the platelet; the MK represents a useful model system for such work, especially given that they can now be grown successfully in culture (Eto et al. 2002). The role of TRPC1 and its splice variants also requires clarification. In heterologous expression systems, TRPC channels form heterotetrameric complexes with members of their own subfamily (that is C1/4/5 and C3/6/7), with functional TRPC1 channels requiring coexpression with TRPC4 or C5 (Hofmann et al. 2002). This would argue against a role for TRPC1 in agonist-evoked currents in the MK where only TRPC1 and TRPC6 were found. However, physical interactions between members of the two different TRPC subfamilies have recently been demonstrated in native tissues, including between TRPC1 and TRPC6 (Sours et al. 2006; Strubing et al. 2003). Therefore, although our data strongly argue for a major role of TRPC6 in the ADP-evoked inward cation current in the MK, we cannot at present rule out an underlying involvement of TRPC1.

In the platelet, TRPC1 has been proposed to contribute to store-dependent Ca2+ influx based primarily upon the blocking action of an antibody targeted at the pore-forming region of the channel (Rosado et al. 2002). However, the importance of TRPC channels in store-dependent Ca2+ influx in the MK/platelet remains unclear. Store depletion with the endomembrane Ca2+-ATPase inhibitor thapsigargin does not activate a visible current under conditions of pseudophysiological intracellular Ca2+ buffering, yet ADP-evoked non-selective cation currents can clearly be detected (Somasundaram & Mahaut-Smith, 1994; Somasundaram & Mahaut-Smith, 1995; Tolhurst et al. 2005). Under high cytosolic Ca2+ buffering conditions, store depletion clearly stimulates a current identical to the CRAC (calcium release activated calcium) current first reported in mast cells (Hoth & Penner, 1992; Somasundaram & Mahaut-Smith, 1994; Somasundaram & Mahaut-Smith, 1995). This conductance is highly selective for Ca2+ over other cations and has a single channel conductance in the femtosiemens, properties that do not resemble any TRP channel reported to date (Parekh & Putney, 2005). Furthermore, several groups have recently identified a transmembrane protein (Orai1/CRACM1/olf186-F) which appears to be responsible for the CRAC conductance (Feske et al. 2006; Zhang et al. 2006; Vig et al. 2006). Thus, in the megakaryocyte/platelet, it seems likely that Orai/CRACM1/olf186-F is the main candidate pathway for store-dependent Ca2+ entry, although at present one cannot rule out a supporting role for TRPC1.

ADP-ribose, which is considered to be a selective activator of TRPM2 (Perraud et al. 2001; reviewed in Harteneck, 2005; Perraud et al. 2001) stimulated a whole-cell current considerably larger than that observed in response to P2Y receptor stimulation or in Mg2+-free pipette salines. This may be due to the large single channel conductance (60–85 pS) and long open times (up to tens of seconds) reported for ADP-ribose-activated TRPM2 (Perraud et al. 2001). A further explanation could be that the conditions used here (1 mm ADP-ribose and 1 μm Ca2+) activate a greater proportion of TRPM2 channels compared to stimulation of TRPC6 and TRPM7 channels by P2Y receptor-stimulation and low Mg2+, respectively. One millimolar ADP-ribose should maximally activate TRPM2 (Perraud et al. 2001), although due to the large diameter and complex morphology of the MK (Mahaut-Smith et al. 2003), the precise subplasma membrane concentration of this mediator may be less than that added to the pipette in our experiments. TRPM2 is a Ca2+-permeable ion channel known to be activated by reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as hydrogen peroxide or reactive nitrogen species, all of which have recently been suggested to act via generation of cytosolic ADP-ribose, which then binds to the channel via its C-terminal NUDT-9 domain (Hara et al. 2002; Wehage et al. 2002; Perraud et al. 2005; Kraft & Harteneck, 2005). Platelets are exposed to a variety of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in vivo and can themselves generate superoxide (Marcus et al. 1977) via NADPH oxidase and possibly other sources (Krotz et al. 2004). TRPM2 therefore provides a pathway in the megakaryocyte/platelet for autocrine and paracrine activation of Ca2+ influx. The NADPH oxidase activity of platelets is < 1% of that in specialized superoxide-producing cells such as neutrophils and therefore platelets can also be exposed to far greater quantities of ROS during inflammatory conditions (Kraft & Harteneck, 2005). A role for NADPH oxidase in platelet activation has been described in the recruitment of platelets to a growing thrombus (Krotz et al. 2002) and in vitro in response to collagen (Chlopicki et al. 2004); however, the mechanism of action of the generated ROS has not been defined and could therefore include Ca2+ influx via TRPM2. A particularly intriguing effect of ADP-ribose-induced activity was the large fluctuating nature of the inward currents (Fig. 4). Although the underlying basis of this effect is unknown, it is interesting to note that large oscillatory inward currents with an apparent dependence upon an increase in intracellular Ca2+ were observed following intrapipette dialysis with IP3 in primary rat megakaryocytes (Hussain & Mahaut-Smith, 1998). A link between receptor activation and ADP-ribosemediated TRPM2 activation has been proposed in lymphocytes (Gasser et al. 2006) and is therefore worthy of further investigation in the platelet.

TRPM7 channels provide a route for divalent cation entry dependent upon both external and internal Mg2+ and therefore may influence platelet activation when cytosolic ATP levels fall. Recently, TRPM7 has been shown to be regulated via protein kinase-A-dependent phosphorylation (Takezawa et al. 2004), and thus this Ca2+-permeable channel may also be affected by the activation status of platelets, which is physiologically regulated by Gs/Gi-coupled receptors that modulate adenylate cyclase activity. A further interesting effect recently reported for TRPM7 is their translocation to the cell surface in response to fluid flow (Oancea et al. 2006); thus they could play roles in mechanosensitive Ca2+ fluxes in the platelet. TRPM1 channels have been less well characterized compared to other TRPM channels. In one study overexpression of the channel led to increased resting Ca2+ levels commensurate with a role for Ca2+ influx for this channel (Xu et al. 2001). TRPM1 is proposed to be a tumour-suppressor based upon an inverse correlation of its expression with the severity of melanoma metastasis (Duncan et al. 1998). It would therefore be of great interest to compare the levels of TRPM1 in normal and megakaryoblastic proliferative diseases such as acute megakaryoblastic leukaemia (Cripe & Hromas, 1998).

Overall therefore the present study provides the first evidence for the molecular basis of major Ca2+ entry pathways in freshly isolated MKs, a cell type now well established as a model for platelet signalling. Direct electrophysiological recordings provide evidence for a major role of TRPC6 in ADP-dependent cation influx and for Ca2+ entry pathways modulated by oxidant stress (TRPM2) and divalent cation levels (TRPM7). These Ca2+-permeable channels may represent targets for therapeutic modulation of megakaryocytic and platelet activation.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the British Heart Foundation (FS/02/057/14377 and PG/06/028/20552), Royal Society and Wellcome Trust.

Supplemental material

The online version of this paper can be accessed at:

DOI: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.113886

http://jp.physoc.org/cgi/content/full/jphysiol.2006.113886/DC1 and contains supplemental material consisting of a table listing primer pairs and PCR conditions.

This material can also be found as part of the full-text HTML version available from http://www.blackwell-synergy.com

References

- Berg LP, Shamsher MK, El Daher SS, Kakkar VV, Authi KS. Expression of human TRPC genes in the megakaryocytic cell lines MEG01, DAMI and HEL. FEBS Lett. 1997;403:83–86. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobe R, Wilde JI, Maschberger P, Venkateswarlu K, Cullen PJ, Siess W, Watson SP. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent translocation of phospholipase Cγ2 in mouse megakaryocytes is independent of Bruton tyrosine kinase translocation. Blood. 2001;97:678–684. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.3.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlow SL, Sage SO. Transient receptor potential protein subunit assembly and membrane distribution in human platelets. Thromb Haemost. 2005;94:839–845. doi: 10.1160/TH05-06-0391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chlopicki S, Olszanecki R, Janiszewski M, Laurindo FR, Panz T, Miedzobrodzki J. Functional role of NADPH oxidase in activation of platelets. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2004;6:691–698. doi: 10.1089/1523086041361640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cripe LD, Hromas R. Malignant disorders of megakaryocytes. Semin Hematol. 1998;35:200–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- den Dekker E, Molin DG, Breikers G, van Oerle R, Akkerman JW, van Eys GJ, Heemskerk JW. Expression of transient receptor potential mRNA isoforms and Ca2+ influx in differentiating human stem cells and platelets. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1539:243–255. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(01)00112-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan LM, Deeds J, Hunter J, Shao J, Holmgren LM, Woolf EA, Tepper RI, Shyjan AW. Down-regulation of the novel gene melastatin correlates with potential for melanoma metastasis. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1515–1520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eto K, Murphy R, Kerrigan SW, Bertoni A, Stuhlmann H, Nakano T, Leavitt AD, Shattil SJ. Megakaryocytes derived from embryonic stem cells implicate CalDAG-GEFI in integrin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12819–12824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202380099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feske S, Gwack Y, Prakriya M, Srikanth S, Puppel SH, Tanasa B, Hogan PG, Lewis RS, Daly M, Rao A. A mutation in Orai1 causes immune deficiency by abrogating CRAC channel function. Nature. 2006;441:179–185. doi: 10.1038/nature04702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleig A, Penner R. The TRPM ion channel subfamily: molecular, biophysical and functional features. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:633–639. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser A, Glassmeier G, Fliegert R, Langhorst MF, Meinke S, Hein D, Kruger S, Weber K, Heiner I, Oppenheimer N, Schwarz JR, Guse AH. Activation of T cell calcium influx by the second messenger ADP-ribose. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2489–2496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506525200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara Y, Wakamori M, Ishii M, Maeno E, Nishida M, Yoshida T, Yamada H, Shimizu S, Mori E, Kudoh J, Shimizu N, Kurose H, Okada Y, Imoto K, Mori Y. LTRPC2 Ca2+-permeable channel activated by changes in redox status confers susceptibility to cell death. Mol Cell. 2002;9:163–173. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00438-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harteneck C. Function and pharmacology of TRPM cation channels. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2005;371:307–314. doi: 10.1007/s00210-005-1034-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassock SR, Zhu MX, Trost C, Flockerzi V, Authi KS. Expression and role of TRPC proteins in human platelets: evidence that TRPC6 forms the store-independent calcium entry channel. Blood. 2002;100:2801–2811. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill K, McNulty S, Randall AD. Inhibition of TRPM2 channels by the antifungal agents clotrimazole and econazole. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2004;370:227–237. doi: 10.1007/s00210-004-0981-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann T, Obukhov AG, Schaefer M, Harteneck C, Gudermann T, Schultz G. Direct activation of human TRPC6 and TRPC3 channels by diacylglycerol. Nature. 1999;397:259–263. doi: 10.1038/16711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann T, Schaefer M, Schultz G, Gudermann T. Subunit composition of mammalian transient receptor potential channels in living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:7461–7466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102596199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner S, Menke K, Hildebrandt C, Kassack MU, Nickel P, Ullmann H, Mahaut-Smith MP, Lambrecht G. The novel suramin analogue NF864 selectively blocks P2X1 receptors in human platelets with potency in the low nanomolar range. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2005;372:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s00210-005-1085-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoth M, Penner R. Depletion of intracellular calcium stores activates a calcium current in mast cells. Nature. 1992;355:353–356. doi: 10.1038/355353a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain JF, Mahaut-Smith MP. ADP and inositol trisphosphate evoke oscillations of a monovalent cation conductance in rat megakaryocytes. J Physiol. 1998;511:791–801. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.791bg.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue R, Okada T, Onoue H, Hara Y, Shimizu S, Naitoh S, Ito Y, Mori Y. The transient receptor potential protein homologue TRP6 is the essential component of vascular α1-adrenoceptor-activated Ca2+-permeable cation channel. Circ Res. 2001;88:325–332. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.3.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung S, Strotmann R, Schultz G, Plant TD. TRPC6 is a candidate channel involved in receptor-stimulated cation currents in A7r5 smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;282:C347–C359. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00283.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapural L, Feinstein MB, O'Rourke F, Fein A. Suppression of the delayed rectifier type of voltage gated K+ outward current in megakaryocytes from patients with myelogenous leukemias. Blood. 1995;86:1043–1055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashiwagi H, Shiraga M, Honda S, Kosugi S, Kamae T, Kato H, Kurata Y, Tomiyama Y. Activation of integrin α IIb β 3 in the glycoprotein Ib-high population of a megakaryocytic cell line, CMK, by inside-out signaling. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2:177–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2003.00529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft R, Harteneck C. The mammalian melastatin-related transient receptor potential cation channels: an overview. Pflugers Arch. 2005;451:204–211. doi: 10.1007/s00424-005-1428-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krotz F, Sohn HY, Gloe T, Zahler S, Riexinger T, Schiele TM, Becker BF, Theisen K, Klauss V, Pohl U. NAD(P)H oxidase-dependent platelet superoxide anion release increases platelet recruitment. Blood. 2002;100:917–924. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.3.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krotz F, Sohn HY, Pohl U. Reactive oxygen species: players in the platelet game. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1988–1996. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000145574.90840.7d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leven RM. Isolation of primary megakaryocytes and studies of proplatelet formation. Meth Mol Biol. 2004;272:281–292. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-782-3:281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahaut-Smith MP. Patch clamp recordings of electrophysiological events in the platelet and megakaryocyte. In: Gibbins JM, Mahaut-Smith MP, editors. Platelets and Megakaryocytes, Perspectives and Techniques. Vol. 2. Totawa, NJ: Humana Press Inc; 2004. pp. 277–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahaut-Smith MP, Thomas D, Higham AB, Usher-Smith JA, Hussain JF, Martinez-Pinna J, Skepper JN, Mason MJ. Properties of the demarcation membrane system in living rat megakaryocytes. Biophys J. 2003;84:2646–2654. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)75070-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahaut-Smith MP, Tolhurst G, Evans RJ. Emerging roles for P2X1 receptors in platelet activation. Platelets. 2004;15:131–144. doi: 10.1080/09537100410001682788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus AJ, Silk ST, Safier LB, Ullman HL. Superoxide production and reducing activity in human platelets. J Clin Invest. 1977;59:149–158. doi: 10.1172/JCI108613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh D, Flemming R, Xu SZ, Perraud AL, Beech DJ. Critical intracellular Ca2+ dependence of transient receptor potential melastatin 2 (TRPM2) cation channel activation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11002–11006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210810200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montell C. The TRP superfamily of cation channels. Sci STKE 2005. 2005:re3. doi: 10.1126/stke.2722005re3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadler MJ, Hermosura MC, Inabe K, Perraud AL, Zhu Q, Stokes AJ, Kurosaki T, Kinet JP, Penner R, Scharenberg AM, Fleig A. LTRPC7 is a Mg.ATP-regulated divalent cation channel required for cell viability. Nature. 2001;411:590–595. doi: 10.1038/35079092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oancea E, Wolfe JT, Clapham DE. Functional TRPM7 channels accumulate at the plasma membrane in response to fluid flow. Circ Res. 2006;98:245–253. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000200179.29375.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parekh AB, Putney JW., Jr Store-operated calcium channels. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:757–810. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00057.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquet JM, Quek L, Stevens C, Bobe R, Huber M, Duronio V, Krystal G, Watson SP. Phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate regulates Ca2+ entry via btk in platelets and megakaryocytes without increasing phospholipase C activity. EMBO J. 2000;19:2793–2802. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.12.2793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perraud AL, Fleig A, Dunn CA, Bagley LA, Launay P, Schmitz C, Stokes AJ, Zhu Q, Bessman MJ, Penner R, Kinet JP, Scharenberg AM. ADP-ribose gating of the calcium-permeable LTRPC2 channel revealed by Nudix motif homology. Nature. 2001;411:595–599. doi: 10.1038/35079100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perraud AL, Takanishi CL, Shen B, Kang S, Smith MK, Schmitz C, Knowles HM, Ferraris D, Li W, Zhang J, Stoddard BL, Scharenberg AM. Accumulation of free ADP-ribose from mitochondria mediates oxidative stress-induced gating of TRPM2 cation channels. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:6138–6148. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411446200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popp R, Englert HC, Lang HJ, Gogelein H. Inhibitors of nonselective cation channels in cells of the blood–brain barrier. EXS. 1993;66:213–218. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-7327-7_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raslova H, Roy L, Vourc'h C, Le Couedic JP, Brison O, Metivier D, Feunteun J, Kroemer G, Debili N, Vainchenker W. Megakaryocyte polyploidization is associated with a functional gene amplification. Blood. 2003;101:541–544. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosado JA, Brownlow SL, Sage SO. Endogenously expressed Trp1 is involved in store-mediated Ca2+ entry by conformational coupling in human platelets. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:42157–42163. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207320200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosado JA, Sage SO. The actin cytoskeleton in store-mediated calcium entry. J Physiol. 2000;526:221–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-2-00221.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sage SO, Brownlow SL, Rosado JA. TRP channels and calcium entry in human platelets. Blood. 2002;100:4245–4246. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakura H, Ashcroft FM. Identification of four trp1 gene variants murine pancreatic β-cells. Diabetologia. 1997;40:528–532. doi: 10.1007/s001250050711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sano Y, Inamura K, Miyake A, Mochizuki S, Yokoi H, Matsushime H, Furuichi K. Immunocyte Ca2+ influx system mediated by LTRPC2. Science. 2001;293:1327–1330. doi: 10.1126/science.1062473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinkins WG, Estacion M, Schilling WP. Functional expression of TrpC1: a human homologue of the Drosophila Trp channel. Biochem J. 1998;331:331–339. doi: 10.1042/bj3310331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somasundaram B, Mahaut-Smith MP. Three cation influx currents activated by purinergic receptor stimulation in rat megakaryocytes. J Physiol. 1994;480:225–231. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somasundaram B, Mahaut-Smith MP. A novel monovalent cation channel activated by inositol trisphosphate in the plasma membrane of rat megakaryocytes. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16638–16644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.28.16638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sours S, Du J, Chu S, Ding M, Zhou XY, Ma R. Expression of canonical transient receptor potential (TRPC) proteins in human glow nerular mesargial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290:F1507–F1515. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00268.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strubing C, Krapivinsky G, Krapivinsky L, Clapham DE. Formation of novel TRPC channels by complex subunit interactions in embryonic brain. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:39014–39019. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306705200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takezawa R, Schmitz C, Demeuse P, Scharenberg AM, Penner R, Fleig A. Receptor-mediated regulation of the TRPM7 channel through its endogenous protein kinase domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6009–6014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307565101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolhurst G, Vial C, Leon C, Gachet C, Evans RJ, Mahaut-Smith MP. Interplay between P2Y1, P2Y12, and P2X1 receptors in the activation of megakaryocyte cation influx currents by ADP: evidence that the primary megakaryocyte represents a fully functional model of platelet P2 receptor signaling. Blood. 2005;106:1644–1651. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng PH, Lin HP, Hu H, Wang C, Zhu MX, Chen CS. The canonical transient receptor potential 6 channel as a putative phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate-sensitive calcium entry system. Biochemistry. 2004;43:11701–11708. doi: 10.1021/bi049349f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vig M, Peinelt C, Beck A, Koomoa DL, Rabah D, Koblan-Huberson M, Kraft S, Turner H, Fleig A, Penner R, Kinet JP. CRACM1 is a plasma membrane protein essential for store-operated Ca2+ entry. Science. 2006;312:1220–1223. doi: 10.1126/science.1127883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehage E, Eisfeld J, Heiner I, Jungling E, Zitt C, Luckhoff A. Activation of the cation channel long transient receptor potential channel 2 (LTRPC2) by hydrogen peroxide. A splice variant reveals a mode of activation independent of ADP-ribose. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23150–23156. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112096200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woulfe D, Yang J, Prevost N, O'Brien PO, Fortna R, Tognolini M, Jiang H, Wu J, Brass LF. Signaling receptors on platelets and megakaryocytes. In: Gibbins JM, Mahaut-Smith MP, editors. Platelets and Megakaryocytes, Methods and Protocols. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press Inc; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu XZ, Moebius F, Gill DL, Montell C. Regulation of melastatin, a TRP-related protein, through interaction with a cytoplasmic isoform. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10692–10697. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191360198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang SL, Yeromin AV, Zhang XH, Yu Y, Safrina O, Penna A, Roos J, Stauderman KA, Cahalan MD. Genome-wide RNAi screen of Ca2+ influx identifies genes that regulate Ca2+ release-activated Ca2+ channel activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9357–9362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603161103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zitt C, Zobel A, Obukhov AG, Harteneck C, Kalkbrenner F, Luckhoff A, Schultz G. Cloning and functional expression of a human Ca2+-permeable cation channel activated by calcium store depletion. Neuron. 1996;16:1189–1196. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80145-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.