Abstract

Naturally expressed nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR) containing α4 subunits (α4*-nAChR) in combination with β2 subunits (α4β2-nAChR) are among the most abundant, high-affinity nicotine binding sites in the mammalian brain. β4 subunits are also richly expressed and colocalize with α4 subunits in several brain regions implicated in behavioural responses to nicotine and nicotine dependence. Thus, α4β4-nAChR also may exist and play important functional roles. In this study, properties were determined of human α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR heterologously expressed de novo in human SH-EP1 epithelial cells. Whole-cell currents mediated via human α4β4-nAChR have ∼4-fold higher amplitude than those mediated via human α4β2-nAChR and exhibit much slower acute desensitization and functional rundown. Nicotinic agonists induce peak whole-cell current responses typically with higher functional potency at α4β4-nAChR than at α4β2-nAChR. Cytisine and lobeline serve as full agonists at α4β4-nAChR but are only partial agonists at α4β2-nAChR. However, nicotinic antagonists, except hexamethonium, have comparable affinities for functional α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR. Whole-cell current responses show stronger inward rectification for α4β2-nAChR than for α4β4-nAChR at a positive holding potential. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that human nAChR β2 or β4 subunits can combine with α4 subunits to generate two forms of α4*-nAChR with distinctive physiological and pharmacological features. Diversity in α4*-nAChR is of potential relevance to nervous system function, disease, and nicotine dependence.

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR) in mammals exist as a diverse family of molecules composed of different combinations of subunits derived from at least 16 genes (see reviews by Lukas et al. 1999; Jensen et al. 2005). nAChR are prototypical members of the ligand-gated ion channel superfamily of neurotransmitter receptors and models used to establish concepts pertaining to mechanisms of drug action, synaptic transmission, and structure and function of transmembrane signalling molecules. The most abundant form of heteromeric nAChR in the brain contains α4 and β2 subunits (α4β2-nAChR; Whiting & Lindstrom, 1987; Flores et al. 1992; Gopalakrishnan et al. 1996; Lindstrom, 1996) although additional subunits may integrate into these complexes. α4β2-nAChR bind nicotine with high affinity, and respond to levels of nicotine found in the plasma of smokers (Benowitz et al. 1989; Hsu et al. 1995; Lindstrom, 1996; Fenster et al. 1997; Lukas et al. 1999; Jensen et al. 2005; Lukas, 2006). They have been implicated in nicotine self-administration, reward, and dependence, and in diseases such as Alzheimer's disease and epilepsy (Picciotto et al. 1995; Cordero-Erausquin et al. 2000; Jensen et al. 2005).

nAChR β4 subunit mRNA colocalizes in different species with α4 subunit mRNA in numerous brain regions (Winzer-Serhan & Leslie, 1997; Quik et al. 2000) implicated in complex behaviours, including nicotine dependence. Knock-out studies suggest that nAChR containing β2 or β4 subunits in mouse brain play different roles. For example, in nAChR β2(−/−) animals, nicotine fails to elicit striatal dopamine release, fails to increase (at concentrations similar to those found in the arterial blood of human smokers) discharge frequency of midbrain dopaminergic neurons, and fails to elicit self-administration, suggesting roles for nAChR-containing β2 subunits in nicotine reinforcement (Picciotto et al. 1998). Although β2 subunit substitution in β4(−/−) animals can prevent the perinatally lethal effects of autonomic failure seen in β2(−/−)/β4(−/−) mice, β4(−/−) mice still exhibit autonomic dysfunction (Wang et al. 2003), have heightened resistance to nicotine-induced seizures (Kedmi et al. 2004), and have decreased nicotine withdrawal symptoms (Salas et al. 2004). Heterologous expression in Xenopus oocytes of rat nAChR α2, α3 or α4 subunits in pairwise combination with either β2 or β4 subunits produces nAChR having differing nicotinic agonist binding affinities attributable to the β subunit assembly partner (Parker et al. 1998). As part of a literature demonstrating functional heterologous expression of functional nAChR-containing β4 subunits, rat nAChR β2 or β4 subunits influence kinetics of whole-cell current decay phase (Fenster et al. 1997) and sensitivity to competitive nicotinic antagonists and Zn2+ modulation (Harvey & Luetje, 1996). Moreover, heterologously expressed, rat α2β4- or α3β4-nAChR show an unusual functional potentiation in the presence of d-tubocurarine at lower concentrations (1–10 μm) than those needed to inhibit nicotinic responses (Cachelin & Rust, 1994).

To establish a foundation for studies of the possible roles of human α4β4-nAChR in addition to α4β2-nAChR in mediation of classic cholinergic excitatory neurotransmission, in modulation of neurotransmitter release, and/or in neuropsychiatric diseases, and to enhance understanding of roles played by β subunits in nAChR structure and function, patch-clamp recording of whole-cell currents was used to undertake a systematic comparison of functional properties of human α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR heterologously expressed in the SH-EP1 human epithelial cell line. Our results show clear distinctions between these nAChR in desensitization kinetics, affinities and efficacies of nicotinic ligands, and current–voltage relationships, demonstrating important influences of β subunits on α4*-nAChR function.

Methods

Expression of human neuronal α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR in SH-EP1 human epithelial cells

Human α4 and β2 or β4 subunits (kindly provided by Dr Ortrud Steinlein or Jon Lindstrom) were subcloned into pcDNA3.1-zeocin and pcDNA3.1-hygromycin vectors, respectively, and transfected using established techniques (Puchacz et al. 1994; Peng et al. 1999, 2005) into native nAChR-null SH-EP1 cells (Lukas et al. 1993) following the approach taken to create the SH-EP1-hα4β2 cell line (Eaton et al. 2003) in order to generate the SH-EP1-hα4β4 cell-line (Eaton et al. 2000). Briefly, three million SH-EP1 cells in 0.5 ml of 20 mm Hepes, 87 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 0.7 mm NaH2PO4, 6 mm dextrose, pH 7.05, in an electroporation cuvette, were mixed with 100 μg of vector DNA containing the β4 subunit insert. Samples were subjected to electroporation (Bio-Rad Gene Pulsar model 1652076, Richmond, CA, USA) at 960 μF and 200 V. After electroporation, cells were suspended to 5 ml in complete medium (Bencherif & Lukas, 1993), and 1 ml aliquots were added to 12 ml aliquots of medium in each of five 100 mm dishes. Forty-eight hours later, positive selection was initiated in medium supplemented with 0.4 mg ml−1 hygromycin (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA). The polyclonal pool of surviving cells was harvested and subjected to a second round of transfection via electroporation with vector DNA containing the α4 subunit insert and selected for zeocin (0.5 mg ml−1; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) resistance beginning 48 h later. Colonies of surviving cells were picked, subcloned by limiting dilution, and expanded before being screened for radioligand binding and functional evidence for α4β4-nAChR expression, which led to selection of the clone designated as the SH-EP1-hα4β4 cell line. Cells were maintained as low passage number (1–26 from our frozen stocks) cultures, to ensure stable expression of phenotype, maintained in medium augmented with 0.5 mg ml−1 zeocin and 0.4 mg ml−1 hygromycin, and passaged once weekly by splitting just-confluent cultures 1/10 to maintain cells in proliferative growth.

RNA preparation and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from the cells growing at approximately 80% confluence in a 100 mm culture dish using 2 ml of Trizol reagent (Bethesda Research Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Prior to RT-PCR, RNA preparations were treated with amplification-grade, RNase-free DNase (Bethesda Research Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) in order to remove residual genomic DNA contamination. Typically, 1 μg of RNA was incubated with 1 unit of DNaseI in a 10 μl reaction at room temperature for 15 min, and then the DNase was inactivated by addition of 1 μl of 25 mm EDTA and incubated at 65°C for 10 min. RT was carried out using 0.8 μg of DNA-free total RNA, oligo d(T)12–18 primer, and the Superscript II Preamplification system (Bethesda Research Laboratories, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) in a 20 μl reaction. At the end of the RT reaction, reverse transcriptase was deactivated by incubation at 75°C for 10 min, and RNAs were removed by adding 1 unit of RNaseH followed by incubation at 37°C for 30 min. A typical PCR was performed using 2 μl of cDNA preparation, 1 μl of 10 μm each of 5′- and 3′-gene-specific primers, 1 μl of 10 mm dNTP, and 2.5 units of RedTaq (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) in a 50 μl reaction. The primers used in the amplification stage were designed and synthesized based on published gene sequences (GenBank accession number: α4 NM000744, β2 NM009602, β4 NM000750; GAPDH BC026907). The primer sequences and their predicted product sizes are: α4 sense 5′-GAATGTCACCTCCATCCGCATC-3′, α4 antisense 5′-CCGGCA(A/G)TTGTC(C/T)TTGACCAC-3′ (product size 790 bp); β2 sense 5′-CGGCTCCCTTCCAAACACA-3′, β2 antisense 5′-GCAATGATGGCGTGGCTGCTGCA-3′ (product size 754 bp); β4 sense 5′-TCTGGTTGCCTGACATCGTG-3′, β4 antisense 5′-GGGTTCACAAAGTACATGGA-3′ (product size 847 bp); GAPDH sense 5′-CGTATTGGGCGCCTGGTCACCAG-3′, GAPDH antisense 5′-GTCCTTGCCCACAGCCTTGGCAGC-3′ (product size 624 bp). Amplification reactions were carried out in a RoboCycler (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) for 35 amplification cycles at 95°C for 1 min, 55°C for 90 s, and 72°C for 90 s, followed by an additional 4-min extension at 72°C. One-tenth of each RT-PCR product was then resolved on a 1% agarose gel, and sizes of products were determined based on migration relative to mass markers loaded adjacently.

Immunolabelling of nAChR α4 subunit in SH-EP1 cells

nAChR subunits on the surface of SH-EP1- hα4β2 and non-transfected SH-EP1 controls were immunolabelled with a rat monoclonal antibody against the nAChR α4 subunit (clone 299; Covance, Berkeley, CA, USA). Live, unfixed, non-permeabilized cells were exposed (4°C, 1 h) to primary antibody diluted in PBS containing 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO, USA), followed by fluorescent, antirat secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) for 1 h. Cells were then fixed (2% formaldehyde in PBS, 4°C, 30 min), dehydrated (methanol, −30°C, 5 min), air-dried, and mounted in ProLong antifade medium (Molecular Probes/Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Samples were examined with a Zeiss Axiovert microscope using a 100×, high-NA objective for fluorescence, and digital images were collected with a Photometrics cooled CCD camera. Images were processed with Photoshop (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA, USA) using the same settings for different samples.

Patch-clamp recordings

Conventional patch-clamp whole-cell current recordings coupled with techniques for fast application and removal of drugs (U-tube) were applied in this study as previously described (Wu et al. 1996, 2002, 2004a and b; Zhao et al. 2003). Briefly, cells plated on polylysine-coated 35-mm culture dishes were placed on the stage of an inverted microscope (Olympus IX7, Lake Success, NY, USA) and continuously superfused with standard external solution (2 ml min−1). Glass microelectrodes (1.5 × 100 mm, Narishige, East Meadow, NY, USA) were made in two steps using a vertical electrode puller (P-830, Narishige, East Meadow, NY, USA). Electrodes with a resistance of 3–5 MΩ between the pipette and external solutions were used to form tight seals (>1 GΩ) on the cell surface, until suction was applied in order to convert to conventional whole-cell recording. Thereafter, the recorded cell was lifted and then voltage clamped at a holding potential (VH) of −60 mV (unless specifically mentioned), and ionic currents in response to application of nicotinic ligands were measured (Axopatch 200B amplifier, Axon Instruments, Union City, CA, USA). Whole-cell access resistance was less than 20 MΩ before series resistance compensation. Both pipette and whole-cell current capacitances were minimized, and series resistance was routinely compensated to 80%. Typically, data were acquired at 10 kHz, filtered at 2 kHz, displayed and digitized online (Digidata 1322 series A/D board, Axon Instruments), and stored to hard drive. Data acquisition and analyses of whole-cell currents were done using Clampex9.2 (Axon Instruments), and results were plotted using Origin 5.0 (OriginLab Corp., North Hampton, MA, USA) or Prism 3.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Concentration–response curves were fitted to the Hill equation. nAChR acute desensitization was analysed for decay time constant (τ), peak current (Ip), and steady-state current (Is) using fits to the expression

or to its bi-exponential variant as appropriate, using data from 90% to 10% of the period between the peak amplitude of the inward current and the termination of the typical 4 s period of agonist exposure. Replicate determinations of τ (a measure of the rate of acute desensitization) and Is/Ip (a measure of the extent of acute desensitization) are presented as means ± standard errors (s.e.m.), and comparisons of τ and Is/Ip values across different conditions were analysed for statistical significance using the Student's t test (paired or independent). All experiments were performed at room temperature (22 ± 1°C).

Solutions and drug application

The standard external solution contained (mm): 120 NaCl, 3 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 25 d-glucose, 10 Hepes, pH adjusted to 7.4 with Tris-base. In some experiments using ACh as an agonist, 1 μm atropine sulphate was added to the standard solution to exclude any possible influences of muscarinic receptors, but the results were the same as those obtained in the absence of atropine (data not shown). Three types of pipette solutions were used for conventional whole-cell recording. Electrodes containing (mm): 140 KCl, 4 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 0.5 EGTA, 4 Na-ATP, 10 Hepes, pH adjusted to 7.2 with KOH (K+ electrodes) were used to examine current–voltage relationships. Electrodes containing (mm): 120 CsCl, 30 NaCl, 4 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 0.5 EGTA, 4 Na-ATP, 10 Hepes, pH adjusted to 7.2 with KOH (Cs+ electrodes) were used in some cases to further compare inward rectification between α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR. This pipette solution was used for two reasons: (a) replacing K+ with Cs+ increased recording stability at more positive VH values, and (b) increasing the Na+ concentration (from 4 to 34 mm) showed more clear outward currents at positive VH values. Electrodes containing (mm): 110 Tris phosphate dibasic, 28 Tris base, 11 EGTA, 2 MgCl2, 0.1 CaCl2, 4 Na-ATP, pH 7.3 (Tris+ electrodes; Huguenard & Prince, 1992) were used for other experiments, since this pipette solution was reported to prevent receptor functional rundown (Zhao et al. 2003).

To initiate whole-cell current responses, under constant superfusion of the recording chamber, nicotinic drugs were rapidly delivered to the recorded cell using a computer-controlled ‘U-tube’ application system. Using this device, the rising time (10–90%) for junction potential effects induced by applied diluted external solution (50% distilled water) was 8.3 ms, and rising times for 1 mm ACh-induced whole-cell currents (VH = −60 mV, lifted whole-cell recording) were 10.9 ± 1.1 ms (n = 15) and 39.2 ± 2.1 ms (n = 8) for α4β2-nAChR and α4β4-nAChR, respectively. In some experiments, a fast-step drug application system (SF-77B, Warner Ins. Co., Hamden, USA) was used. With minimal movement of it (100 μm), the rising time for junction potential effects was 3.0 ms, and the rising times for 1 mm ACh-induced whole-cell currents (VH = −60 mV, lifted whole-cell recording) were 10.8 ± 1.2 ms (n = 9) and 33.9 ± 3.2 ms (n = 9) for α4β2-nAChR and α4β4-nAChR, respectively. Intervals between drug applications (3 min) were adjusted specifically to ensure stability of nAChR responsiveness (absence of functional rundown), and the selection of pipette solutions used in most of the studies described here was made with the same objective. Drugs used in the present study were (−)nicotine, ACh, epibatidine, cytisine, lobeline, dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE), mecamylamine (MEC), hexamethonium (HEXA), d-tubocurarine (dTC), and methyllycaconitine (MLA) (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA).

Results

Evidence for expression of nAChR subunits in transfected SH-EP1 cells

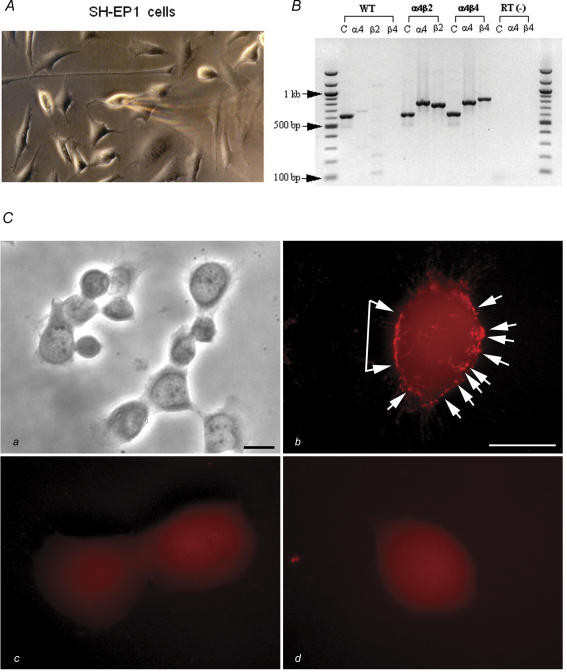

SH-EP1 cells exhibit a range of morphologies before (not shown) or after (Fig. 1A) transfection with nAChR subunits. Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analyses showed expression of human nAChR α4 and β2 subunit messages in SH-EP1-hα4β2 cells, and expression of human α4 and β4 subunit messages in SH-EP1-hα4β4 cells (Fig. 1B). By contrast, there was no such expression in the absence of the reverse transcription step or in the untransfected cell host, despite successful amplification of GAPDH message in all of the cells (Fig. 1B). Immunocytochemical staining using a monoclonal anti-nAChR α4 subunit antibody showed bright, punctate, specific labelling on the surfaces of transfected SH-EP1-hα4β2 cells (Fig. 1Cb; see phase contrast image at lower power in Fig. 1Ca) but no specific labelling on untransfected cells (Fig. 1Cc) or SH-EP1-hα4β2 cells exposed only to secondary antibody (Fig. 1Cd). These results indicated appropriate expression of nAChR subunits from cDNAs as messages and as cell surface protein in stably transfected SH-EP1 cells.

Figure 1. Morphology and transgene expression in SH-EP1 cells.

A, phase-contrast photomicrograph of transfected SH-EP1 cells during patch-clamp recording. B, RT-PCR analysis of α4, β2 or β4 nAChR subunit transcripts or GAPDH internal controls (C) from wild-type (WT) SH-EP1 cells or from cells cotransfected with α4 plus either β2 (α4β2) or β4 (α4β4) subunits. Lanes labelled ‘RT(−)’ are for samples from SH-EP1-hα4β4 cells processed after omission of the RT step. Sizes of RT-PCR products resolved on a 1% agarose gel are calibrated using a 100-bp DNA ladder (New England BioLabs Inc., Beverly, MA, USA). C, immunolabelling of nAChR α4 subunits on SH-EP1-hα4β2 cells. Ca, low-magnification, phase-contrast view of SH-EP1-hα4β2 cells. Cb, high-magnification, fluorescence view of a SH-EP1-hα4β2 cell labelled with rat monoclonal antibody 299 against the nAChR α4 subunit. Cc, non-transfected SH-EP1 cells labelled with the same antibody as in B. Cd, a SH-EP1-hα4β2 cell labelled with secondary antibody only. Note the bright, punctate, specific labelling (arrows in panel Cb) on the surface of SH-EP1-hα4β2 cells and the absence of specific labelling on non-transfected cells and SH-EP1-hα4β2 cells exposed only to secondary antibody. Bars in Ca and Cb represent 5 μm; bar in Cb applies to panels Cb–Cd.

Distinctive properties of functional α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR

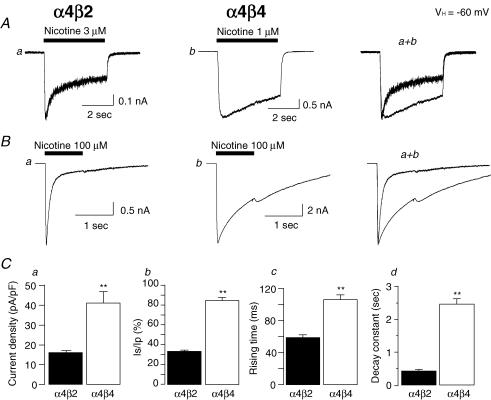

Whole-cell current recording using Tris+ electrodes revealed the expression of functional α4β2- or α4β4-nAChR in transfected SH-EP1-hα4β2 or SH-EP1-hα4β4 cells responding to nicotine (Fig. 2). One obvious difference in whole-cell response profiles depending on the nAChR β subunit assembly partner was the kinetics and extent of whole-cell current decay from peak to steady-state levels during a single exposure to nicotine. We operationally define this process as nAChR acute desensitization. The rate of acute desensitization was much slower for α4β4-nAChR than for α4β2-nAChR, and the extent of whole-cell current decline was smaller for α4β4-nAChR than for α4β2-nAChR (Fig. 2A and B). Another obvious difference was the higher amplitude of α4β4-nAChR responses (peak and steady-state) to low (around EC50; see below) or high (100 μm) concentrations of nicotine (Fig. 2A and B). Results obtained from studies of SH-EP1 cells each expressing either α4β2- (n = 31) or α4β4-nAChR (n = 31) confirm the higher amplitude responses mediated by α4β4-nAChR after normalizing inward current to cell capacitance (16.3 ± 1.6 pA pF−1 current density for α4β2-nAChR; 41.3 ± 5.7 pA pF−1 for α4β4-nAChR; Fig. 2Ca). Across those cells, in the presence of EC50 concentrations of nicotine, the average ratio of steady-state/peak currents was 34 ± 1% for α4β2-nAChR and 85 ± 2% for α4β4-nAChR (Fig. 2Cb), and the average time required for an e-fold rise inward current was 59 ± 3 ms for α4β2-nAChR and 107 ± 6 ms for α4β4-nAChR, reflecting faster opening of α4β2-nAChR channels (Fig. 2Cc). The average time constants for e-fold decline in nicotine-induced whole-cell current from peak values were 440 ± 50 ms for α4β2-nAChR (nicotine 3 μm, n = 20) and 2480 ± 160 ms for α4β4-nAChR (nicotine 1 μm, n = 18, Fig. 2Cd), reflecting the faster and more extensive acute desensitization of α4β2- compared to α4β4-nAChR. These effects were not artifacts of the rate of drug delivery, and the lower amplitude of the peak current response mediated by α4β2-nAChR was not a consequence of the faster desensitization of those receptors. Whole-cell current densities induced in the presence of a lower concentration of nicotine (100 nm) that produced no clear desensitization of either receptor were 1.99 ± 0.36 pA pF−1 (n = 7) for α4β2-nAChR and 4.72 ± 0.66 pA pF−1 (n = 7, P < 0.01) for α4β4-nAChR, preserving the >2-fold higher response of α4β4-nAChR compared to α4β2-nAChR.

Figure 2. Electrophysiological properties of α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR.

Low (3 or 1 μm, A) or high (100 μm, B) concentrations of nicotine were applied to induce whole-cell inward currents in transfected SH-EP1 cells stably expressing human α4β2- (Aa and Ba) or α4β4- (Ab and Bb) nAChR. Superimposed traces from each row are shown in the right column. C, bar graphs summarizing results of replicate studies (31 cells each) illustrating differences between α4β2- (filled bars) and α4β4- (open bars) nAChR responses in net current density (a), the ratio of steady-state to peak components (b), the rising time to peak whole-cell current (c) and whole-cell current decay constant (d). Data were averaged from 31 cells tested for Fig. 2 Ca-c, and 18 cells tested for α4β4-nAChR and 20 cells tested for α4β2-nAChR in Fig. 2Cd, and vertical bars represent s.e.m. **P < 0.01 for difference between α4*-nAChR subtypes. All data presented in Fig. 2C were obtained from whole-cell currents induced by equipotent concentrations of 3 μm nicotine (α4β2-nAChR) or 1 μm nicotine (α4β4-nAChR).

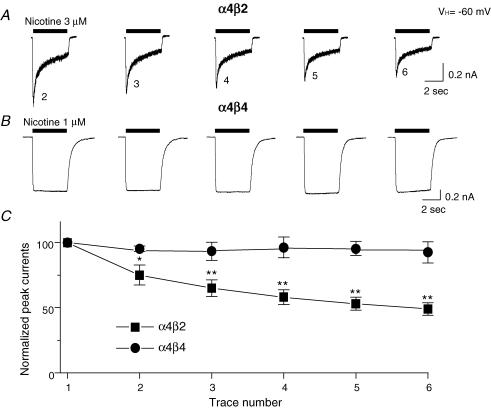

During recording using a K+ electrode, repeated exposures of a SH-EP1 cell expressing α4β2-nAChR to nicotine at its EC50 concentration (see below) for 4 s at 1 min intervals caused a gradual reduction in peak current amplitudes, which we operationally define as functional rundown (Fig. 3A and C). By contrast, the same protocol for repeated challenge with nicotine did not produce functional rundown of α4β4-nAChR-mediated currents (Fig. 3B and C). These results indicate that nAChR β2 or β4 subunits play important roles in determining functional rundown of α4*-nAChR.

Figure 3. Functional rundown of α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR.

Using K+ electrodes at a VH of −60 mV, 3 or 1 μm nicotine was repetitively applied for 4 s at 1-min intervals to SH-EP1 cells expressing either α4β2- (A) or α4β4- (B) nAChR, respectively. Peak current components from whole-cell current traces are plotted against trace number in (C) for α4β2- (▪) or α4β4- (•) nAChR. Each symbol represents the average from six cells tested, and vertical bars represent s.e.m. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Nicotinic agonist actions at α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR

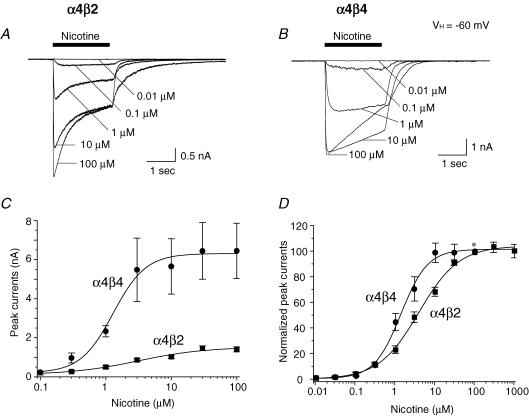

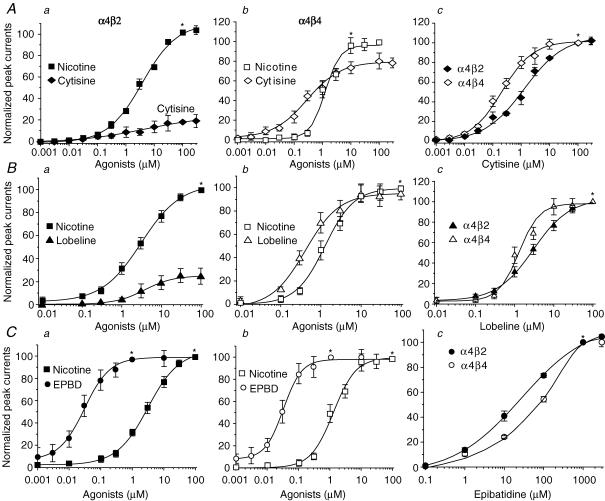

α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR-mediated whole-cell currents induced by different concentrations of nicotine were recorded using Tris+ electrodes at a VH of −60 mV (Fig. 4A and B). Absolute (Fig. 4C) or normalized (to the response to 100 μm nicotine; Fig. 4D) peak whole-cell current responses to nicotine when plotted as a function of nicotine concentration were sigmoidal and well-fitted by a single-site model of the logistic equation (with no improvement in fit using a two-site model). Fits to the data yielded EC50 values and Hill coefficients of 3.1 μm (2.0–4.7 μm; 95% confidence interval) and 0.78 ± 0.09 (s.e.m.), respectively, for α4β2-nAChR (n = 10 cells), and 1.3 μm (0.72–2.20 μm) and 1.18 ± 0.27, respectively, for α4β4-nAChR (n = 7 cells; Fig. 4D). Moreover, peak current amplitude was about 5-fold higher for α4β4- than for α4β2-nAChR (Fig. 4C). These findings demonstrated both higher efficacy (Fig. 4C) and affinity (Fig. 4D) for nicotine acting at human α4β4-nAChR compared to α4β2-nAChR (Table 1). Whole-cell peak current response profiles for other nicotinic agonists, including cytisine (Fig. 5A), lobeline (Fig. 5B) and epibatidine (EPBD) (Fig. 5C), were obtained and normalized to the maximal response to nicotine (at 100 μm; Fig. 5A–C, columns a and b). These profiles indicate partial (∼20%) efficacy of cytisine and lobeline (compared to maximal effects of nicotine or ACh) at α4β2-nAChR, but nearly full or full efficacy at α4β4-nAChR, whereas epibatidine acts as a full agonist at both α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR. When responses to individual agonists were normalized to their own maximal effect at a given α4*-nAChR subtype (Fig. 5A–C, column c), it was evident that EC50 values for cytisine were about 6-fold lower and EC50 values for nicotine, ACh, lobeline or epibatidine were about 2.4- to 3.4-fold lower for actions at α4β4-nAChR compared to actions at α4β2-nAChR (Table 1). Rank-order agonist potency (EC50 values and 95% confidence intervals provided in parentheses) is epibatidine (0.100 μm; 0.03–0.36) >> cytisine (1.3 μm; 0.79–2.20) ≥ nicotine (3.1 μm; 2.0–4.7) = lobeline (3.1 μm; 2.5–3.9) ≥ ACh (4.1 μm; 3.2–5.0) for α4β2-nAChR, and epibatidine (0.029 μm; 0.020–0.043) > cytisine (0.21 μm; 0.14–0.33) > nicotine (1.3 μm; 0.72–2.20) = lobeline (1.3 μm; 0.73–2.30) ≥ ACh (1.7 μm; 1.2–2.4) for α4β4-nAChR. These results indicate that cytisine or lobeline act on α4β2-nAChR as partial agonists, but act on α4β4-nAChR as full agonists, providing a means for distinguishing between α4*-nAChR subtypes in addition to generally higher agonist potency at α4β4-nAChR (Table 1).

Figure 4. Nicotine concentration–response relationships for α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR.

Five superimposed whole-cell current traces elicited in response to nicotine exposure (0.01–100 μm) are shown for cells expressing either α4β2- (A) or α4β4- (B) nAChR. C, nicotine alone (*) concentration–response curves plotted for absolute peak current values for α4β2- (▪) or α4β4- (•) nAChR show differences in current amplitudes. D, nicotine concentration–response curves plotted for peak currents normalized to those evoked in response to 100 μm nicotine alone (*) show differences at α4β2- (▪) or α4β4- (•) nAChR in agonist potency. In C and D, each symbol represents the average from 6–8 cells, and vertical bars represent s.e.m.

Table 1.

Profiles for agonist interactions with α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR

| α4β2 | α4β4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| log EC50 | Hill coefficient | n | log EC50 | Hill coefficient | n | |

| Nicotine | −5.51 ± 0.07 | 0.78 ± 0.09 | 10 | −5.90 ± 0.10 | 1.18 ± 0.27 | 7 |

| ACh | −5.39 ± 0.04 | 0.87 ± 0.07 | 7 | −5.77 ± 0.06 | 1.91 ± 0.42 | 6 |

| Epibatidine | −6.98 ± 0.26 | 0.59 ± 0.13 | 6 | −7.54 ± 0.08 | 0.58 ± 0.05 | 6 |

| Cytisine | −5.88 ± 0.10 | 0.62 ± 0.09 | 6 | −6.67 ± 0.08 | 0.80 ± 0.08 | 7 |

| Lobeline | −5.51 ± 0.04 | 0.85 ± 0.05 | 5 | −5.89 ± 0.10 | 1.19 ± 0.28 | 6 |

Whole-cell current recording was done as described in Methods and in the legends to Figs 4 and 5 as a function of agonist concentration. Peak whole-cell currents elicited were plotted against log molar agonist concentration, and the results were fitted to the logistic equation to determine log EC50 values and Hill coefficients (±s.e.m.) as indicated for either α4β2- or α4β4-nAChR. Also shown are the numbers of cells from which data were analysed.

Figure 5. Concentration–response curves for cytisine, lobeline and epibatidine acting at α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR.

Peak current responses of α4β2- (left column) or α4β4- (middle column) nAChR evoked by cytisine (A; ♦ or ⋄), lobeline (B; ▴ or ▵), or epibatidine (EPBD) (C; • or ○) are plotted after being normalized to the response evoked by 100 μm nicotine (▪ or □; indicated by *) or (right column) responses of both α4*-nAChR subtypes to those drugs normalized to the maximal response to a given drug are plotted. Each symbol represents the average from 5 to 6 cells tested, and vertical bars represent standard errors.

Nicotinic antagonist actions at α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR

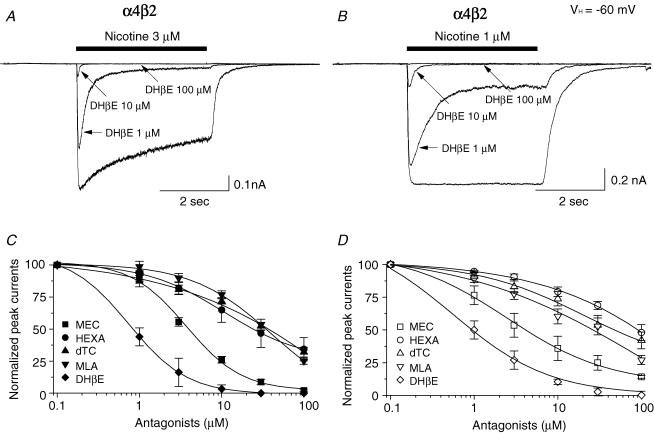

The effects of selected nicotinic antagonists on function of α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR elicited by EC50 concentrations of nicotine were assessed using Tris+ electrode recording. DHβE coapplied with nicotine reduced both peak and steady-state current responses of both α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 6A and B). Similar studies evaluated concentration-dependent effects of other antagonists on function of α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR (Fig. 6C and D, Table 2). As DHβE does, mecamylamine, d-tubocurarine and methyllycaconitine block nicotine-induced peak currents mediated through α4β2- or α4β4-nAChR, with largely similar inhibitory potencies (Table 2). Hexamethonium more potently blocks α4β2- than α4β4-nAChR function (Table 2). Rank-order inhibition potency (IC50 values and 95% confidence intervals provided in parentheses) is DHβE (0.89 μm; 0.72–1.10) > > mecamylamine (4.2 μm; 3.5–5.1) >> hexamethonium (30 μm; 21–42) ∼ methyllycaconitine (35 μm; 31–38) = d-tubocurarine (35 μm; 26–46) for α4β2-nAChR and DHβE (1.2 μm; 0.93–1.50) >> mecamylamine (4.9 μm; 3.2–7.4) > > methyllycaconitine (26 μm; 17–39) ≥ d-tubocurarine (50 μm; 37–68) > hexamethonium (91 μm; 74–110) for α4β4-nAChR.

Figure 6. Antagonism of α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR function.

3 μm (A) or 1 μm (B) nicotine (∼EC50 concentration)-induced whole-cell currents obtained from exposure to SH-EP1-hα4β2 (left) or -hα4β4 (right) cells alone or in the presence of different concentrations of DHβE are superimposed. C and D, effects of coexposure to DHβE (♦, ⋄), mecamylamine (MEC; ▪, □), hexamethonium (HEXA; •, ○), d-tubocurarine (d-TC; ▴, ▵) or methyllycaconitine (MLA; ▾, ▿) on nicotine-evoked whole-cell peak current responses of α4β2- (3 μm nicotine, C) or α4β4-nAChR (1 μm nicotine, D) are plotted as concentration–response curves. Each symbol represents the average from 5–6 cells, and vertical bars represent s.e.m.

Table 2.

Comparison of antagonist properties of α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR

| α4β2 | α4β4 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| log IC50 | Hill coefficient | log IC50 | Hill coefficient | |

| DHβE | −6.05 ± 0.03 | −1.45 ± 0.15 | −5.92 ± 0.04 | −1.16 ± 0.12 |

| Mecamylamine | −5.38 ± 0.03 | −1.29 ± 0.10 | −5.31 ± 0.07 | −0.69 ± 0.07 |

| Hexamethonium | −4.53 ± 0.05 | −0.67 ± 0.06 | − 4.04 ± 0.03 | −0.65 ± 0.04 |

| d-TC | −4.46 ± 0.04 | −0.64 ± 0.05 | −4.30 ± 0.05 | −0.59 ± 0.04 |

| Methyllycaconitine | −4.46 ± 0.02 | −0.99 ± 0.04 | −4.59 ± 0.07 | −0.62 ± 0.07 |

Whole-cell current recording was done as described in Methods and in the legend to Fig. 6 as a function of antagonist concentration. Peak whole-cell currents elicited were plotted against log molar antagonist concentration, and the results were fitted to the logistic equation to determine log IC50 values and Hill coefficients (±s.e.m.) as indicated for either α4β2- or α4β4-nAChR. Data are averages for values determined from 5–7 cells.

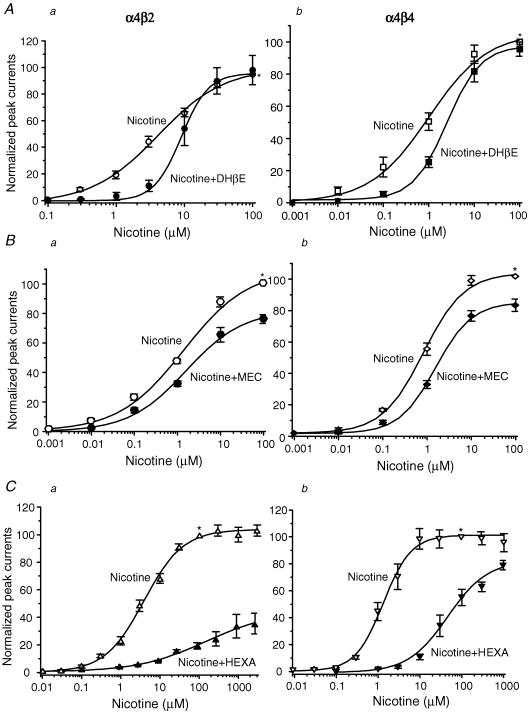

Nicotine dose–response profiles were obtained alone or in the presence of 0.3 μm DHβE, 1 μm mecamylamine, or 0.5 μm hexamethonium (Fig. 7). In the presence of DHβE, nicotine concentration–response curves were predominantly shifted to the right without effects on the maximal response for both α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR, consistent with a competitive mechanism of functional block (Fig. 7Aa and b). Mecamylamine reduced the maximal current response without changing nicotine EC50 values, suggesting a non-competitive block (Fig. 7Ba and b). Interestingly, hexamethonium exhibited non-competitive block of α4β2-nAChR but displayed features of competitive block of α4β4-nAChR (Fig. 7Ca and b). These results suggest that classic competitive (DHβE) or non-competitive (mecamylamine) nicotinic antagonists have expected effects on both α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR, whereas the mechanism of hexamethonium block is probably different for α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR.

Figure 7. Comparison of antagonist action at α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR.

Nicotine concentration–response curves alone or in the presence of 0.3 μm DHβE (Aa, α4β2-nAChR; Ab, α4β4-nAChR), 1 μm MEC (Ba, α4β2-nAChR; Bb, α4β4-nAChR) or 0.5 μm HEXA (Ca, α4β2-nAChR; Cb, α4β4-nAChR) are superimposed. All nicotinic responses were normalized to the current induced by 100 μm nicotine alone (*). Each symbol represents the average from 5–8 cells, and vertical bars represent s.e.m.

Current–voltage relationships for α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR

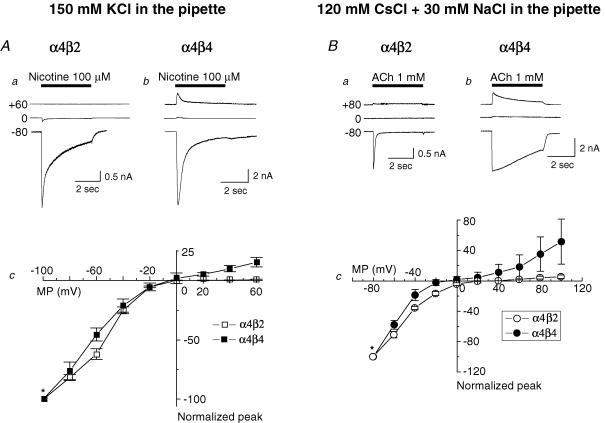

Whole-cell current traces recorded using K+ electrodes and obtained for 100 μm nicotine-induced activation of α4β2-nAChR after stepwise changes in VH prior to agonist application show full inward rectification at positive VH (Fig. 8Aa), but when using the same protocol for α4β4-nAChR responses, inward rectification at positive VH was substantial but incomplete (Fig. 8Ab). Results compiled from studies using six cells confirm that α4β4-nAChR-mediated whole-cell currents exhibit less inward rectification than α4β2-nAChR-mediated currents, suggesting roles for β subunits in the phenomenon (Fig. 8Ac). In additional studies using pipette solutions containing 30 mm NaCl to enhance outward currents, responses to 1 mm ACh at VH values between −80 and +100 mV were recorded for α4β2- (Fig. 8Ba) and α4β4-nAChR (Fig. 8Bb). Figure 8Bc summarizes the current–voltage relationship curves (from −80 to +100 mV) for α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR from six cells tested, and confirms weaker inward rectification for α4β4-nAChR- than for α4β2-nAChR-mediated whole-cell currents.

Figure 8. Current-voltage (I–V) relationships for α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR.

A, whole-cell peak currents evoked by 100 μm nicotine (indicated by black horizontal bar) at different VH values (−80, 0, +60 mV) are shown above current–voltage response curves normalized to the response to nicotine at −100 mV (*) for α4β2- (Aa; □ in Ac) or α4β4- (Ab; ▪ in Ac) nAChR. Each symbol represents the average from six cells, and vertical bars (in c) represent s.e.m. B, sample traces for I–V curve analyses for α4β2- (a) and α4β4- (b) nAChR whole-cell current responses assessed using a higher (30 mm) concentration of Na+ in the pipette solution evoked by 1 mm ACh (indicated by black horizontal bar) at different VH values (−80, 0, +80 mV) are shown above current–voltage response curves normalized to the response to nicotine at −80 mV (*) for α4β2- (Ba; ○ in (Bc) or α4β4- (Bb; • in Bc) nAChR.

Discussion

The present study reveals differences between heterologously expressed, human α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR in agonist potencies and efficacies, in sensitivity to selected antagonists, in kinetics and amplitudes of whole-cell current responses, and in sensitivity to functional rundown and inward rectification. That is, when compared to α4β2-nAChR, α4β4-nAChR mediate responses that have higher whole-cell current density, exhibit a slower decay rate, are characterized by a smaller extent of acute desensitization, are subject to less functional rundown, and exhibit reduced inward rectification. Based on effects on peak whole-cell currents, nicotine, acetylcholine, cytisine, lobeline and epibatidine have higher functional potency at α4β4-nAChR than at α4β2-nAChR, but nicotinic antagonists have comparable functional inhibitory potency at both α4*-nAChR subtypes except for hexamethonium, which is a weaker antagonist of α4β4-nAChR function. Hexamethonium has features more like a competitive antagonist at α4β4-nAChR, but like a non-competitive blocker of α4β2-nAChR function. Competitive or non-competitive mechanisms of block across α4*-nAChR subtypes are conserved for DHβE or mecamylamine, respectively. These results indicate that nAChR β2 or β4 subunits influence a number of properties, but not all features, of α4*-nAChR function.

β subunits influence sensitivity of α4*-nAChR to functional inactivation

Given that nAChR appear to undergo more than one phase of functional inactivation, we propose the use of at least two terms to describe these processes and refined approaches to tease them apart. ‘Acute desensitization’ is defined in the present study as it was by Ochoa et al. (1990): the loss in nAChR response during a single stimulus or exposure to agonist, reflecting decay of inward currents typically recorded from a cholinoceptive cell from a peak to a lower, steady-state level. Levels of acute desensitization can be quantified in terms of time or rate constants of the decay in response and by the ratio between steady-state and peak inward current responses. Provided that the duration of agonist exposure is limited, and that the time between agonist challenges is adequately long, full recovery should occur from acute desensitization within seconds to minutes. ‘Functional rundown’ is defined as the reduction in peak responses to agonist due to repetitive agonist exposures. Ochoa et al. (1990) provided an illustration (see their Fig. 3B), but not a specific definition, of functional rundown. By our definition, functional rundown can be quantified in terms of peak current amplitude either as a function of cumulative time of repetitive agonist exposures or of numbers of agonist exposures.

The current study addresses the roles of β subunits in α4*-nAChR acute desensitization and functional rundown. They show dramatically lower acute desensitization and functional rundown of α4β4-nAChR compared to α4β2-nAChR. The high conservation of amino acids across human β2 and β4 subunits in putative transmembrane domains, including the M2 domain thought to line the channel itself, suggests that alternative sites may be involved in differences in functional inactivation. One candidate is the second major cytoplasmic loop, changes in which influence nAChR acute desensitization (Kuo et al. 2005). The finding that there is slower desensitization of α4β4-nAChR than of α4β2-nAChR may have physiological and pathophysiological significance. For example, given their comparable sensitivity to nicotine, α4β4-nAChR would be more resistant to functional inactivation by nicotine than α4β2-nAChR (see Gentry et al. 2003), meaning they could play an important role in maintaining cholinergic network activity after chronic exposure to smoking-relevant nicotinic concentrations (100–500 nm), under conditions where other nAChR are either deeply desensitized (Pidoplichko et al. 1997) or not activated (Zhao et al. 2003). Consistent with such a perspective, β4-subunit knockout mice have altered nicotine withdrawal symptoms (Salas et al. 2004). Diversity in nAChR dependent on whether they contain β2 or β4 subunits (perhaps in combination with additional subunits from the family) thus could allow for different physiological outcomes relevant to nicotine reinforcement, dependence and withdrawal.

β subunits influence α4*-nAChR pharmacology

Many studies have indicated that mammalian brain α4β2-nAChR are the nAChR subtype with the highest binding affinity for nicotine (Benowitz et al. 1989; Hsu et al. 1995; Fenster et al. 1997; Lukas et al. 1999; Jensen et al. 2005; Lukas, 2006). In studies using nAChR heterologously expressed in the oocyte system, the binding affinity of ACh for rat α4β2-nAChR was 2-fold higher than for rat α4β4-nAChR (Parker et al. 1998). However, patch-clamp whole-cell recording using the same expression system showed a 2-fold higher functional agonist potency for ACh acting at α4β4-nAChR compared to α4β2-nAChR (Francis et al. 2000). Our results show that nicotine, epibatidine and ACh have ∼2.4–3.4-fold higher functional potency when acting at α4β4-nAChR than at α4β2-nAChR. Moreover, α4β4-nAChR have higher affinity than α4β2-nAChR for cytisine and lobeline, both of which are fully efficacious at α4β4-nAChR but are only partial agonists at α4β2-nAChR. Interestingly, radioligand binding studies indicate that human α4β2-nAChR have higher agonist-binding affinities than human α4β4-nAChR (Eaton et al. 2000), but this simply suggests that functional and binding assays may assess ligand interactions with different states (resting, desensitized) of the receptor. Thus, α4β2-nAChR remain as the highest affinity binding sites for nicotinic agonists when assessed using radioligand binding, but α4β4-nAChR have higher agonist affinities when surveyed using whole-cell (or ion flux; Eaton et al. 2000) assays.

Antagonist sensitivities of the two α4*-nAChR subtypes studied are similar for the agents tested except for hexamethonium, which engages in non-competitive block of α4β2-nAChR, but has a competitive and weaker inhibitor profile when acting at α4β4-nAChR. A caveat is that these experiments assessed the effects on whole-cell peak currents, which may or may not be the most important indicator of physiological or pharmacological status of nAChR in vivo. Nevertheless, from a potential therapeutic perspective, these studies suggest that nicotinic agonists selectively targeting α4β4-nAChR could be designed that would be much less efficacious and potent when acting at α4β2-nAChR, and perhaps diseases affecting nicotinic signalling and elements of nicotine dependence could be treated with better outcome by targeting α4β4-nAChR.

β subunits influence α4*-nAChR inward rectification

Inward rectification is an important functional feature of several ligand- and voltage-gated ion channels, including α4*-nAChR (Haghighi & Cooper, 1998), but the mechanisms involved remain unclear. It has been suggested that polyamine interactions with a subsite in the channel-lining domain of nAChR blocks the channel pore in a voltage-dependent manner, leading to receptor inward rectification (Haghighi & Cooper, 1998, 2000). Apparent inverse relationships between inward rectification and Ca2+ permeability have been suggested in other studies (Lewis, 1979; Adams et al. 1980; Hume et al. 1991; Verdoorn et al. 1991; Dingledine et al. 1999). Other models consider relationships between roles for intracellular K+ in destabilization of polyamines with nAChR during depolarization and/or in outward ion flow (Washburn et al. 1997; Haghighi & Cooper, 1998). We have found that heterologously expressed, human α4β4-nAChR show less inward rectification than α4β2-nAChR, even when the intracellular Na+ concentration is high. There is a previous report of lower Ca2+ permeability in β4-containing than in β2-containing nAChR (Haghighi & Cooper, 1998). However, further studies comparing α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR have promise with respect to elucidation of mechanisms engaged in inward rectification.

Potential physiological relevance of β4-containing nAChR in the brain

nAChR β4 subunits play clear roles as assembly partners with α3 subunits in α3β4*-nAChR that mediate trans-ganglionic signalling (Duvoisin et al. 1989; Rust et al. 1994; Xu et al. 1999). β4 subunits also are expressed in the central nervous system as both mRNA and protein (Dineley-Miller & Patrick, 1992; Tarroni et al. 1992; Poth et al. 1997; Quick et al. 1999; Quik et al. 2000; Klink et al. 2001; Gahring et al. 2004). In several brain regions, including the basal ganglia, cerebellum, hippocampus and cortex, the β4 subunit is a candidate assembly partner for the α4 subunit because α3 subunits are either absent or expressed at low levels (Dineley-Miller & Patrick, 1992). β4 subunits are prominently expressed in thalamic somatosensory relay nuclei and in somatosensory cortex (Gahring et al. 2004), suggesting involvement in sensory processing. β4-null mice have altered responses in anxiety-related tests (Salas et al. 2003) and upon nicotine withdrawal (Salas et al. 2004), and have higher resistance to nicotine-induced seizures (Kedmi et al. 2004). Dopamine neurons freshly dissociated from the rat ventral tegmental area express functional nAChR with properties suggestive of the presence of β4 subunits that are expressed as mRNA in the same region (Wu et al. 2005). These putative β4*-nAChR mediate whole-cell current responses to ACh that are of higher amplitude (400–1000 pA) and desensitize more slowly than α4β2-nAChR-mediated responses. These β4*-nAChR are sensitive to the nicotinic agonist cytisine, but insensitive to the α4β2-nAChR-selective agonist RJR-2403 (Papke et al. 2000). In addition, these β4*-nAChR are highly sensitive to the nicotinic receptor antagonist mecamylamine, but show low sensitivity to the α4β2-nAChR-selective antagonist DHβE. While the possibility is that these nAChR have a subunit composition more complicated than α4 plus β4, the similarities between their properties and those of α4β4-nAChR defined in the current study are striking, and involvement of β4 subunits seems clear. Functional β4*-nAChR in midbrain dopamine neurons may contribute to nicotine-induced modulation of midbrain dopamine neuronal function.

In summary, human α4β2- and α4β4-nAChR heterologously expressed in human SH-EP1 cells exhibit distinctive physiological and pharmacological properties. Heterologous expression of these entities and identification of ways to distinguish them provide insights into roles of these two α4*-nAChR subtypes in health and disease and as therapeutic targets.

Acknowledgments

Work toward this project, part of which was conducted in the Charlotte and Harold Simensky Neurochemistry of Alzheimer's Disease Laboratory, was supported by endowment and/or capitalization funds from the Men's and Women's Boards of the Barrow Neurological Foundation, the Robert and Gloria Wallace Foundation, and Epi-Hab Phoenix, Inc., and by grants from the National Institutes of Health (DA015389), the Arizona Disease Control (Biomedical) Research Commission (9615 and 9930), the Council for Tobacco Research (4366), the Marjorie Newsome and Sandra Solheim Aiken funds, and an Arizona Alzheimer's Disease Center pilot grant (P30 AG19610). The contents of this report are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the aforementioned awarding agencies.

References

- Adams DJ, Smith SJ, Thompson SH. Ionic currents in molluscan soma. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1980;3:141–167. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.03.030180.001041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bencherif M, Lukas RJ. Cytochalasin modulation of nicotinic cholinergic receptor expression and muscarinic receptor function in human TE671/RD cells: a possible functional role of the cytoskeleton. J Neurochem. 1993;61:852–864. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb03596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz NL, Porchet H, Jacob P., III Nicotine dependence and tolerance in man: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic investigations. Prog Brain Res. 1989;79:279–287. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)62487-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cachelin AB, Rust G. Unusual pharmacology of (+)-tubocurarine with rat neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors containing beta 4 subunits. Mol Pharmacol. 1994;6:1168–1174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero-Erausquin M, Marubio LM, Klink R, Changeux J-P. Nicotinic receptor function: perspectives from knockout mice. Trends Pharm Sci. 2000;21:211–217. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(00)01489-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dineley-Miller K, Patrick J. Gene transcripts for the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit, beta4, are distributed in multiple areas of the rat central nervous system. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1992;16:339–344. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(92)90244-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingledine R, Borges K, Bowie D, Traynelis SF. The glutamate receptor ion channels. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;1:7–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvoisin RM, Deneris ES, Patrick J, Heinemann S. The functional diversity of the neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors is increased by a novel subunit: beta 4. Neuron. 1989;3:487–496. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(89)90207-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton JB, Kuo Y-P, Fuh LP-T, Krishnan C, Steinlein O, Lindstrom JM, Lukas RJ. Properties of stably and heterologously-expressed human α4β4-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChR) Soc Neurosci Abstract. 2000;26:371. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton JB, Peng J-H, Schroeder KM, George AA, Fryer JD, Krishnan C, Buhlman L, Kuo Y-P, Steinlein O, Lukas RJ. Characterization of human α4β2-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors stably and heterologously expressed in native nicotinic receptor-null SH-EP1 human epithelial cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64:1283–1294. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.6.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenster CP, Rains MF, Noerager B, Quick MW, Lester RAJ. Influence of subunit compositions on desensitization of neuronal acetylcholine receptors at low concentrations of nicotine. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5747–5759. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05747.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores CM, Rogers SW, Pabreza LA, Wolfe BB, Kellar KJ. A subtype of nicotinic cholinergic receptor in rat brain is composed of α4 and β2 subunits and is up-regulated by chronic nicotine treatment. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;41:31–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis MM, Vazquez RW, Papke RL, Oswald RE. Subtype-selective inhibition of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors by cocaine is determined by the alpha4 and beta4 subunits. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:109–119. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gahring LC, Persiyanov K, Rogers SW. Neuronal and astrocyte expression of nicotinic receptor subunit beta4 in the adult mouse brain. J Comp Neurol. 2004;468:322–333. doi: 10.1002/cne.10942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentry CL, Wilkins LH, Jr, Lukas RJ. Effects of prolonged nicotinic ligand exposure on function of heterologously expressed, human α4β2- and α4β4-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Pharmacol Exper Ther. 2003;304:206–216. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.041756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gopalakrishnan M, Monteggia LM, Anderson DJ, Molinari EJ, Lattoni-Kaplan M, Donnelly-Roberts D, Arneric SP, Sullivan JP. Stable expression, pharmacologic properties and regulation of the human neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine α4β2 receptor. J Pharmacol Exper Ther. 1996;276:289–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haghighi AP, Cooper E. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are blocked by intracellular spermine in a voltage-dependent manner. J Neurosci. 1998;18:4050–4062. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-11-04050.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haghighi AP, Cooper E. A molecular link between inward rectification and calcium permeability of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine alpha3beta4 and alpha4beta2 receptors. J Neurosci. 2000;20:529–541. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-02-00529.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey SC, Luetje CW. Determinants of competitive antagonist sensitivity on neuronal nicotinic receptor beta subunits. J Neurosci. 1996;16:3798–3806. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-12-03798.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu Y-N, Amin J, Weiss DS, Wecker L. Sustained nicotine exposure differentially affects α3β2 and α4β2 neuronal nicotine receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Neurochem. 1995;66:667–675. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66020667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huguenard JG, Prince DA. A novel T-type current underlies prolonged Ca2+-dependent burst firing in GABAergic neurons of rat thalamic reticular nucleus. J Neurosci. 1992;12:3804–3817. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-10-03804.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hume RI, Dingledine R, Heinemann SF. Identification of a site in glutamate receptor subunits that controls calcium permeability. Science. 1991;253:1028–1031. doi: 10.1126/science.1653450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen AA, Frolund B, Liljefors T, Krogsgaard-Larsen P. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: Structural revelations, target identifications, and therapeutic inspirations. J Med Chem. 2005;48:4705–4745. doi: 10.1021/jm040219e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedmi M, Beaudet AL, Orr-Urtreger A. Mice lacking neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor beta4-subunit and mice lacking both alpha5- and beta4-subunits are highly resistant to nicotine-induced seizures. Physiol Genomics. 2004;17:221–229. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00202.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klink R, de Kerchove d'Exaerde A, Zoli M, Changeux JP. Molecular and physiological diversity of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the midbrain dopaminergic nuclei. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1452–1463. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01452.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo Y-P, Xu L, Eaton JB, Zhao L, Wu J, Lukas RJ. Roles for nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit large cytoplasmic loop sequences in receptor expression and function. J Pharmacol Exper Ther. 2005;314:455–466. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.084954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis CA. Ion-concentration dependence of the reversal potential and the single channel conductance of ion channels at the frog neuromuscular junction. J Physiol. 1979;286:417–445. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1979.sp012629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom J. Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. In: Narahashi T, editor. Ion Channels. Vol. 4. New York: Plenum Press; 1996. pp. 377–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukas RJ. Pharmacological effects of nicotine and nicotinic receptor subtype pharmacological profiles. In: George TP, editor. Medication Treatments for Nicotine Dependence. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2006. pp. 3–23. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Lukas RJ, Changeux J-P, Novère N, Le Albuquerque EX, Balfour DJK, Berg DK, Bertrand D, Chiappinelli VA, Clarke PBS, Collins AC, Dani JA, Grady SR, Kellar KJ, Lindstrom JM, Marks MJ, Quik M, Taylor PW, Wonnacott S. International Union of Pharmacology. XX. Current status of the nomenclature for nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and their subunits. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51:397–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukas RJ, Norman SA, Lucero L. Characterization of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors expressed by cells of the SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma clonal line. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1993;4:1–12. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1993.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa ELM, Li L, McNamee MG. Desensitization of central cholinergic mechanisms and neuroadaptation to nicotine. Mol Neurobiol. 1990;4:251–287. doi: 10.1007/BF02780343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papke RL, Webster JC, Lippiello PM, Bencherif M, Francis MM. The activation and inhibition of human nicotinic acetylcholine receptor by RJR-2403 indicate a selectivity for the alpha4beta2 receptor subtype. J Neurochem. 2000;75:204–216. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker MJ, Beck A, Luetje CW. Neuronal nicotinic receptor beta2 and beta4 subunits confer large differences in agonist binding affinity. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;54:1132–1139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J-H, Fryer JD, Hurst RS, Schroeder KM, George AA, Morrissy S, Groppi V, Leonard SS, Lukas RJ. High-affinity epibatidine binding of functional, human α7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors stably and heterologously expressed de novo in human SH-EP1 cells. J Pharmacol Exper Ther. 2005;313:24–35. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.079004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J-H, Lucero L, Fryer J, Herl J, Leonard SS, Lukas RJ. Inducible, heterologous expression of human α7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in a native nicotinic receptor-null human clonal line. Brain Res. 1999;825:172–179. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR, Zoli M, Lena C, Bessis A, Lallemand Y, Novere N, Le Vincent P, Pich EM, Brulet P, Changeux J-P. Abnormal avoidance learning in mice lacking functional high-affinity nicotine receptor in the brain. Nature. 1995;374:65–67. doi: 10.1038/374065a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR, Zoli M, Rimondini R, Lena C, Marubio LM, Pich EM, Fuxe K, Changeux JP. Acetylcholine receptors containing the beta2 subunit are involved in the reinforcing properties of nicotine. Nature. 1998;391:173–177. doi: 10.1038/34413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pidoplichko VI, DeBiasi M, Williams JT, Dani JA. Nicotine activates and desensitizes midbrain dopamine neurons. Nature. 1997;390:401–404. doi: 10.1038/37120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poth K, Nutter TJ, Cuevas J, Parker MJ, Adams DJ, Luetje CW. Heterogeneity of nicotinic receptor class and subunit mRNA expression among individual parasympathetic neurons from rat intracardiac ganglia. J Neurosci. 1997;17:586–596. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-02-00586.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puchacz E, Buisson B, Bertrand D, Lukas RJ. Functional expression of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors containing rat α7 subunits in human neuroblastoma cells. FEBS Lett. 1994;354:155–159. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)01108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quick MW, Ceballos RM, Kasten M, McIntosh JM, Lester RA. Alpha3beta4 subunit-containing nicotinic receptors dominate function in rat medial habenula neurons. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:769–783. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00024-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quik M, Polonskaya Y, Gillespie A, Jakowec M, Lloyd GK, Langston JW. Localization of nicotinic receptor subunit mRNAs in monkey brain by in situ hybridization. J Comp Neurol. 2000;425:58–69. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20000911)425:1<58::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rust G, Burgunder JM, Lauterburg TE, Cachelin AB. Expression of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit genes in the rat autonomic nervous system. Eur J Neurosci. 1994;6:478–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas R, Pieri F, De Biasi M. Decreased signs of nicotine withdrawal in mice null for the beta4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10035–10039. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1939-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas R, Pieri F, Fung B, Dani JA, De Biasi M. Altered anxiety-related responses in mutant mice lacking the beta4 subunit of the nicotinic receptor. J Neurosci. 2003;16:6255–6263. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-15-06255.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarroni P, Rubboli F, Chini B, Zwart R, Oortgiesen M, Sher E, Clementi F. Neuronal-type nicotinic receptors in human neuroblastoma and small-cell lung carcinoma cell lines. FEBS Lett. 1992;312:66–70. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)81411-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdoorn TA, Burnashev N, Monyer H, Seeburg PH, Sakmann B. Structural determinants of ion flow through recombinant glutamate receptor channels. Science. 1991;252:1715–1718. doi: 10.1126/science.1710829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N, Orr-Urtreger A, Chapman J, Rabinowitz R, Korczyn AD. Deficiency of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor beta 4 subunit causes autonomic cardiac and intestinal dysfunction. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:574–580. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.3.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washburn MS, Numberger M, Zhang S, Dingledine R. Differential dependence on GluR2 expression of three characteristic features of AMPA receptors. J Neurosci. 1997;17:9393–9406. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-24-09393.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiting PJ, Lindstrom J. Purification and characterization of a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor from rat brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:595–599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.2.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winzer-Serhan UH, Leslie FM. Co-distribution of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit α3 and β4 mRNAs during rat brain development. J Comp Neurol. 1997;386:540–554. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19971006)386:4<540::aid-cne2>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, George AA, Schroeder KM, Xu L, Marxer-Miller S, Lucero L, Lukas RJ. Electrophysiological, pharmacological and molecular evidence for α7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat midbrain dopamine neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004b;311:80–91. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.070417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Harata N, Akaike N. Potentiation by sevoflurane of the GABAA-induced Cl- current in acutely dissociated CA1 pyramidal neurons from rat hippocampus. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;119:1013–1021. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15772.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Hu J, Marxer-Miller S, Lucero L, Lukas RJ. Diversity of functional nicotinic receptor subtypes in VTA dopamine neurons. Soc Neurosci Abstract. 2005;723:15. [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Kuo YP, George AA, Xu L, Hu J, Lukas RJ. β-amyloid directly inhibits human α4β2-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors heterologously expressed in human SH-EP1 cells. J Biol Chem. 2004a;279:37842–37851. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400335200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Zhao L, Eaton JB, Lukas RJ. Intracellular K+ effluxes through activated nicotinic acetylcholine receptor/channels contributing to acute desensitization in human neuronal α4β2-nAChR heterologously expressed in the SH-EP1 human epithelial cells. Soc Neurosci Abstract. 2002;617:8. [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Orr-Urtreger A, Nigro F, Gelber S, Sutcliffe CB, Armstrong D, Patrick JW, Role LW, Beaudet AL, De Biasi M. Multiorgan autonomic dysfunction in mice lacking the beta2 and the beta4 subunits of neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Neurosci. 1999;19:9298–9305. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-21-09298.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Kuo YP, George AA, Peng JH, Purandare MS, Schroeder KM, Lukas RJ, Wu J. Functional properties of homomeric, human α7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors heterologously expressed in the SH-EP1 human epithelial cell line. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305:1132–1141. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.048777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]