Abstract

M-current (IM) plays a key role in regulating neuronal excitability. Mutations in Kv7/KCNQ subunits, the molecular correlates of IM, are associated with a familial human epilepsy syndrome. Kv7/KCNQ subunits are widely expressed, and IM has been recorded in somata of several types of neurons, but the subcellular distribution of M-channels remains elusive. By combining field-potential, whole-cell and intracellular recordings from area CA1 in rat hippocampal slices, and computational modelling, we provide evidence for functional M-channels in unmyelinated axons in the brain. Our data indicate that presynaptic M-channels can regulate axonal excitability and synaptic transmission, provided the axons are depolarized into the IM activation range (beyond ∼−65 mV). Here, such depolarization was achieved by increasing the extracellular K+ concentration ([K+]o). Extracellular recordings in the presence of moderately elevated [K+]o (7–11 mm), showed that the specific M-channel blocker XE991 reduced the amplitude of the presynaptic fibre volley and the field EPSP in a [K+]o-dependent manner, both in stratum radiatum and in stratum lacknosum moleculare. The M-channel opener, retigabine, had opposite effects. The higher the [K+]o, the greater the effects of XE991 and retigabine. Similar pharmacological modulation of EPSPs recorded intracellularly from CA1 pyramidal neurons, while blocking postsynaptic K+ channels with intracellular Cs+, confirmed that active M-channels are located presynaptically. Computational analysis with an axon model showed that presynaptic IM can control Na+ channel inactivation and thereby affect the presynaptic action potential amplitude and Ca2+ influx, provided the axonal membrane potential is sufficiently depolarized. Finally, we compared the effects of blocking IM on the spike after-depolarization and bursting in CA3 pyramidal neuron somata versus their axons. In standard [K+]o (2.5 mm), XE991 increased the ADP and promoted burst firing at the soma, but not in the axons. However, IM contributed to the refractory period in the axons when spikes were broadened by a low dose 4-aminopyridine (200 μm). Our results indicate that functional Kv7/KCNQ/M-channels are present in unmyelinated axons in the brain, and that these channels may have contrasting effects on excitability depending on their subcellular localization.

M-channels are voltage-gated K+ channels that underlie the non-inactivating M-current (IM) in neurons (Brown & Adams, 1980). These slowly activating and deactivating channels are particularly interesting because they activate at subthreshold membrane potentials at which few other ion channels are active. Therefore, they may be important determinants of neuronal excitability and response patterns (Brown & Adams, 1980; Halliwell & Adams, 1982; Peters et al. 2005; Madison & Nicoll, 1984; Storm, 1989; Yuc & Yaari, 2004; Gu et al. 2005). This idea is supported by the discovery that mutations in the human Kv7.2/KCNQ2 and Kv7.3/KCNQ3 genes, which probably encode the main M-channel subunits, cause a dominantly inherited form of human generalized epilepsy called benign familial neonatal convulsions (BFNC) (Charlier et al. 1998; Singh et al. 1998). In addition to the BFNC phenotype, a family carrying a KCNQ2 mutation also has myokymia, suggesting that KCNQ2 may be involved in motoneuron or motor axon function (Dedek et al. 2001). Moreover, a recent study showed that suppression of IM by a KCNQ2 subunit with a dominant negative pore mutation in transgenic mice caused spontaneous seizures, behavioural hyperexcitability and morphological changes in the hippocampus (Peters et al. 2005).

At the cellular level, M-channel activity controls neuronal excitability, bursting and early spike-frequency adaptation, and to generate afterhyperpolarizations of medium duration (mAHPs) during and after repetitive neuronal discharge (Storm, 1989; Yue & Yaari, 2004; Gu et al. 2005; Peters et al. 2005). In a previous study we also found that IM generates resonance at theta frequencies in CA1 pyramidal neurons, suggesting a role for M-channels in facilitating theta network oscillations (Hu et al. 2002).

In CA1 pyramidal neurons, native M-channels seem to be composed largely of KCNQ2/KCNQ3 subunits (Shah et al. 2002; Peters et al. 2005). Immunohistochemical studies show overlapping KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 protein expression patterns on both somatic and dendric levels the hippocampus and neocortex (Cooper et al. 2001). KCNQ2 immunoreactivity is also found at nodes of myelinated axons in the central and peripheral nervous systems, sometimes colocalized with KCNQ3 subunits (Devaux et al. 2004). The initial segment of several neurons in hippocampus, neocortex, brainstem and striatum also show KCNQ2 expression, often colocalized with KCNQ3 (Devaux et al. 2004). Interestingly, the mossy fibres in the hippocampus show a remarkably dense expression for KCNQ2 (Cooper et al. 2001; Devaux et al. 2004).

Despite the abundance of immunohistochemistry data, there are few electrophysiological studies of the subcellular distribution of M-channels [Devaux et al. 2004; Chen & Johnston, 2004; Hu H et al. FENS Forum abstr. 2006 (A189.8)]. Although M-channels are well-known regulators of neuronal excitability, nearly all that is known about the functions of these channels is based on somatic recordings. It is increasingly clear that the impact of K+ channels on neuronal functions is not only determined by their kinetic properties, but also depends on their highly diverse subcellular distributions (Hoffman et al. 1997; Hu et al. 2001; Dodson & Forsythe, 2004). In this study, we address the following questions: (1) do Kv7/KCNQ subunits form functional M-channels in unmyelinated axons in the brain, and (2) if so, how do they influence axonal excitability and synaptic transmission?

We chose to study the glutamatergic Schaffer collateral axons in area CA1 of the hippocampus because its stratified structure facilitates recording of pre- and postsynaptic responses, and because the stratum radiatum synapses are rather typical and extensively studied cortical excitatory synapses.

We demonstrate that functional M-channels exist in Schaffer collaterals and that they can regulate excitability and transmitter release. Our data suggest that the prerequisite for IM to affect synaptic transmission is that the axon should be sufficiently depolarized to activate M-channels. In this study, this was demonstrated by rising the extracellular K+ concentration, [K+]o. The higher the [K+]o, the stronger the effect of M-channel modulation on synaptic transmission. Numerical simulations with a model axon revealed that, in elevated [K+]o, IM can indirectly regulate INa inactivation, spike amplitude and spike-evoked Ca2+ influx, by influencing the membrane potential.

Furthermore, we compared the effect of blocking IM on the afterdepolarization (ADP) following the action potential in CA3 pyramidal neuron somata versus Schaffer collaterals. In standard [K+]o (2.5 mm), blockade of M-channels increased the ADP and promoted burst firing at the soma but not in the axons. However, IM contributed to the refractory period in the axons when spikes were broadened by application of a low dose 4-aminopyridine (4-AP; 200 μm).

Our results indicate that functional Kv7/KCNQ/M-channels are present in unmyelinated axons in the brain, and that these channels can have contrasting roles depending on their subcellular localization. Some preliminary results have been published previously [Agdestein C. et al. Soc Neurosci. abstr. 2004, (501.20)].

Methods

The experimental procedures were approved by the responsible veterinarian of the institute, in accordance with the statute regulating animal experimentation, given by the Norwegian ministry of agriculture.

Slices for whole-cell recording

Male Wistar rats (4–10 weeks old) were deeply anaesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of Equithesin (3 ml (kg body weight)−1), before being perfused transcardially with an ice-cold solution containing (mm): 230 sucrose, 25 NaHCO3, 1.25 KCl, 1.25 KH2PO4, 7 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 25 glucose, and saturated with 95% O2–5% CO2. After decapitation, horizontal hippocampal slices (300–400 μm) were prepared with a HR2 vibratome (Sigmann Elektronik GmbH, Germany) and stored at room temperature in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) containing (mm): 125 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 1.25 KCl, 1.25 KH2PO4, 1.0–1.5 MgCl2, 1.0 CaCl2 and 25 glucose. To preserve the slice surface for whole-cell patch recording under visual control, the slices were stored submerged in aCSF.

Slices for field potential and intracellular recording

These slices were prepared as described for whole-cell recording, except that Suprane was used for anaesthesia, transcardial perfusion was not used, and the slices were cut with a Vibroslicer (Campden Instruments) and stored in an interface chamber with aCSF.

Chemicals and drugs

The M-channel blockers XE991 (10,10-bis (4-pyridinylmethyl)-9(10H)-antracenone) and linopirdine(1-phenyl-3,3-bis(4-pyridinylmethyl)-2-indoli-none) were obtained from DuPont pharmaceutical company and NeuroSearch A/S, Ballerup, Denmark, respectively. DNQX (6,7-dinitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione), dl-APV (2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid) and 4-AP were purchased from Tocris Cookson Ltd (UK). Retigabine (N-(2-amino-4-(4-fluorobenzyl-amino)-phenyl) carbamic acid ethyl ester) was generously provided by Drs J. B. Jensen and W. D. Brown, NeuroSearch A/S. The remaining chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich. Substances were applied by adding them to the perfusion medium.

Extracellular field-potential recording

Extracellular field potentials were recorded in submerged slices maintained at 31 ± 0.5°C, with low resistance glass micropipettes filled with aCSF (as described above, except that the CaCl2 concentration was 2 mm) and coupled to an Axoclamp 2B amplifier (Molecular Devices Corporation). Additionally, the signal was amplified 50× by a custom-build amplifier. A tungsten stimulation electrode and the recording electrode were both placed (∼200–400 μm apart) in the middle of either the stratum radiatum (to record from Schaffer collaterals) or the stratum lacunosum moleculare. The stimuli, consisting of a brief current pulse (100 μs duration, repeated at 0.050 or 0.033 Hz), elicited compound action potentials, followed by field EPSPs (fEPSPs). In experiments designed for measuring only the compound action potential (fibre volley, FV), 50 μm DNQX, 50 μmdl-APV and 5 μm bicuculline free base were added to the aCSF to eliminate fEPSPs and IPSPs, thus avoiding contamination of the FV. The FV amplitude was measured from the initial positive to the most negative peak. The fEPSP initial slope was measured within the first millisecond of the response immediately after the negative peak of the fibre volley. The fEPSP initial slope was used because this parameter is more linearly related to the synaptic conductance than, e.g. the area or peak amplitude of the fEPSP (Johnston & Wu, 1995). Only experiments with stable fEPSPs and FV responses, i.e. with less than 15% deviation during the last 10 min before drug application or other manipulations (increasing [K+]o), were included in the analysis. The input–output relations for stimulus intensity (0–300 μA) versus FV and/or fEPSP amplitude were determined, and the stimulation intensity that evoked 20–30% of the maximal response was selected for testing (except when stated otherwise, cf. below).

Whole-cell recording

Slices were transferred to a recording chamber, maintained submerged at 31 ± 0.5°C and perfused with aCSF containing 2.0 mm CaCl2. Whole-cell recordings were obtained from CA1 pyramidal neurons under visual guidance in an upright microscope equipped with IR-DIC (BX50; Olympus). Patch pipettes were filled with a solution containing (mm): 140 caesium gluconate, 10 Hepes, 2 ATP, 0.4 GTP, 2 MgCl2 and 10 phosphocreatine, giving a pipette resistance of 2–5 MΩ. Signals were recorded with a Dagan BVC 700A amplifier (Minneapolis, USA) in current-clamp mode. The series resistance was 15–60 MΩ, and all potentials were corrected for the junction potential (−8 to −10 mV). Some whole-cell experiments were performed using the ‘blind’ method (n = 2 in Fig. 3Aa, and the ‘data not shown’, below, n = 5). For the series of ‘blind patch’ experiments, slices were incubated in an interface chamber until use. We observed no indication that the use of different incubation chambers (submerged or interface) or recording optics (visual or blind patch methods) affected the results. For the experiments of Fig. S3 (see online Supplemental material figures S1–S3), the intracellular solution contained 140 mm KMeSO4 instead of 140 mm caesium gluconate.

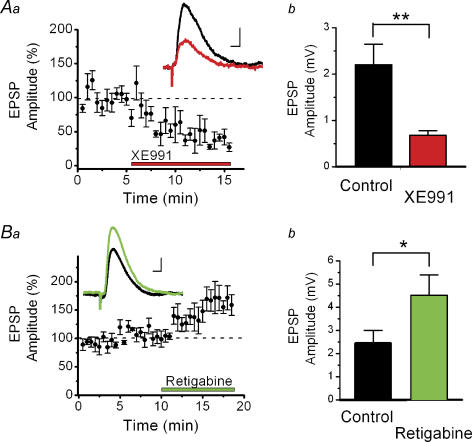

Figure 3. XE991 reduced and retigabine increased EPSPs recorded from CA1 pyramidal neurons in elevated [K+]o (11.5 mM).

Whole-cell recordings of EPSPs in CA1 pyramidal cells, in response to stimulation in stratum radiatum. In the patch pipette, all K+ ions were replaced by 140 mm Cs+ to block postsynaptic K+ channels. Aa, summary time course (mean ± s.e.m.) of the effect of 10 μm XE991 on the EPSP amplitude in the presence of 50 μmdl-APV and 5 μm bicuculline (n = 5). The membrane potential was maintained at −78 mV during each experiment. Inset shows averages of five consecutive traces before (black) and after (red) application of XE991. Ab, XE991 reduced the EPSP amplitude from 2.2 ± 0.4 to 0.68 ± 0.10 mV (n = 4, P = 0.002). Ba and b, in similar conditions as in Aa and b, 20 μm retigabine increased the EPSP amplitude from 2.4 ± 0.6 to 4.5 ± 0.9 mV (n = 6, P = 0.045). Scale bars for insets in Aa and Bb: 5 ms, 1 mV.

Intracellular recording

Slices were transferred to a recording chamber, maintained submerged at 31 ± 0.5°C, and perfused with aCSF containing 2.0 mm CaCl2. Intracellular recordings were obtained from CA3 pyramidal neuron somata with sharp electrodes filled with 4.0 m potassium acetate (resistance 80–140 MΩ, pH 7.35). Current-clamp recordings were performed using an Axoclamp 2A amplifier (Molecular Devices) in bridge mode. The area of the ADP in Fig. 7 was measured during a window of 50 ms starting from the end of the current pulse.

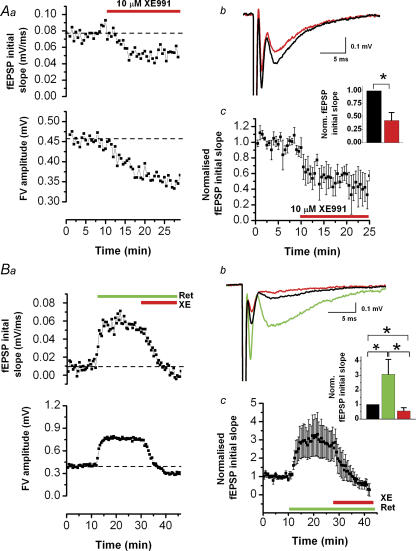

Figure 7. Blocking IM increased the ADP and promoted burst firing in CA3 pyramidal neuron somata in standard [K+]o (2.5 mM).

CA3 pyramidal neurons were recorded with sharp electrodes in the presence of DNQX (50 μm), dl-APV (50 μm) and bicuculline (5 μm). The prestimulus membrane potential was maintained at −60 mV by steady current injection. A brief current pulse (10 ms, 0.5 nA) was injected every 10 s to evoke a single action potential (Aa). A single spike is followed by an after-depolarization (ADP), and medium and slow after-hyperpolarizations (mAHP and sAHP). Inset, the spike and AHPs on a compressed time scale. Ab–d, application of 10 μm XE991 increased the ADP and promoted burst firing followed by a prominent sAHP. B, time course of the XE991-induced changes in ADP amplitude and firing (same experiment as in Aa–d). When the cell fired only a single spike, the area of the ADP is indicated by ○. Bursts are indicated by |, in different rows for bursts consisting of 2, 3 or 4 spikes. Note that the number of spikes during a burst progressively increased. C, summary plot of the effect of XE991 on the ADP area, for all cells tested (n = 7; control, 254 ± 38 mV ms−1; XE991, 433 ± 87 mV ms−1; P = 0.036).

Data acquisition and analysis

The data were acquired using pCLAMP 9.0 (Molecular Devices) filtered at 5 kHz (field potential recording), digitally sampled at 20 kHz, and analysed and plotted with pCLAMP 9.0 and Origin 7.0 (Microcal). Pooled data are expressed as means ± s.e.m., and statistical differences were evaluated by a two-tailed paired Student's t test (significance level, 0.05).

Computational methods

Computer simulations were performed with the Surf-hippo simulator, version 3.5a (http://www.neurophys.biomedicale.univ-paris5.fr/~graham/surf-hippo.html). For simulations of M-channel effects in the axon, we made a model consisting of an axonal cable with 10 compartments of equal length (total length 1 mm, and diameter 0.2 μm) connected to a soma (diameter 15 μm). For simulations of M-channel effects at the soma (Fig. S3), we used our standard model for studying somatic responses (Gu et al. 2005; Vervaeke et al. 2006), which consists of a soma (diameter 15 μm) connected to a dendritic cable consisting of four segments of equal length (total length 800 μm and diameter 5 μm). The soma, dendrite and axonal segments had a membrane resistance of 40 kΩcm2, membrane capacitance of 1.0 μF cm−2, and uniform intracellular resistance of 100 Ωcm. The extracellular resistance was 200 Ωcm. The voltage-gated ion channels included a Hodgkin-Huxley type transient sodium current (INa), delayed rectifier type potassium channel (IK), M-current (IM) and a high-threshold voltage-activated calcium current (ICa). All channels were uniformly distributed in soma and axon. The dendritic cable contained uniformly distributed IK and INa, but no IM

The currents and current kinetics used in the model were based on data from previous studies. Immunohistochemical and pharmacological data provide good evidence that Kv1-type K+ channels repolarize the action potential in the Schaffer collaterals. These axons show a high density of immunoreactivity for Kv1.1, Kv1.4 and Kvβ1 subunits (Sheng et al. 1993; Rhodes et al. 1997; Cooper et al. 1998; Monaghan et al. 2001). The Kv1 channel blockers dendrotoxin and low (<100 μm) doses of 4-AP caused profound broadening of the FV and increased transmitter release, suggesting that Kv1 channels mediate the major repolarizing K+ current in these axons (Hu et al. 2001). Since the main K+ channels underlying IK of the squid giant axon also belongs to Kv1 (Rosenthal et al. 1996), we used a K+ channel model based on the standard IK model for squid axon (Hodgkin & Huxley, 1952), which also provides a relatively accurate description of the voltage dependence of activation of IK in mossy fibre axons and boutons (Geiger & Jonas, 2000; Engel & Jonas, 2005). K+ channel inactivation was implemented multiplicatively; the gating parameters were based on published inactivation properties of recombinant Kv1.4 channels (Wissmann et al. 2003; Engel & Jonas, 2005). Transmitter release at the Schaffer collateral boutons is triggered by Ca2+ influx mainly through high-threshold N- and P/Q-type Ca2+ channels (Takahashi & Momiyama, 1993; Wheeler et al. 1994; Dunlap et al. 1995). Therefore, the Ca2+ current kinetics were chosen to match the kinetics of high-threshold Ca2+ channels in CA1 pyramidal neurons as described by Magee & Johnston (1995). Finally, IM kinetics were inferred from our previous studies on IM in CA1 pyramidal neurons (Hu et al. 2002; Gu et al. 2005).

The kinetics of the currents are described in the supplemental material. Nerve terminals were represented as lumped together with the axon shaft. This seems a reasonable simplification because Schaffer collaterals form en-passant boutons, which are merely local ‘swellings’ of the axon, at ∼3.7 μm intervals (Shepherd et al. 2002). Since the calculated length constant of these axons is several hundred micrometres (see our computational model and also Alle & Geiger, 2006), the en-passant boutons probably do not form separate electrical compartments, but are virtually isopotential with the axon shaft. The resting potential was set by the reversal potential of the leak current, calculated according to the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz voltage equation as:

|

with K+ permeability (PK) = 9 × 10−6(cm/s), Na+ permeability (PNa) = 0.38 × 10−6(cm/s), Cl− permeability (PCl) = 10−6(cm/s), [K+]i = 145−6(mm), [Na+]o = 150 (mm), [Na+]i = 12 (mm), [Cl−]i = 4 (mm), [Cl−]o = 128 (mm). The reversal potential of IM and IK are determined by the Nernst equation as RT/F ln([K+]o/145). The temperature in the simulations was set to 30°C. The extracellular field potential was calculated 0.5 μm from the axon. The rate of decay of the action potential (Fig. 5G) was measured as the slope between the spike peak (at time tp) and at the time when the baseline level (defined as the potential at tp + 1 ms) was reached.

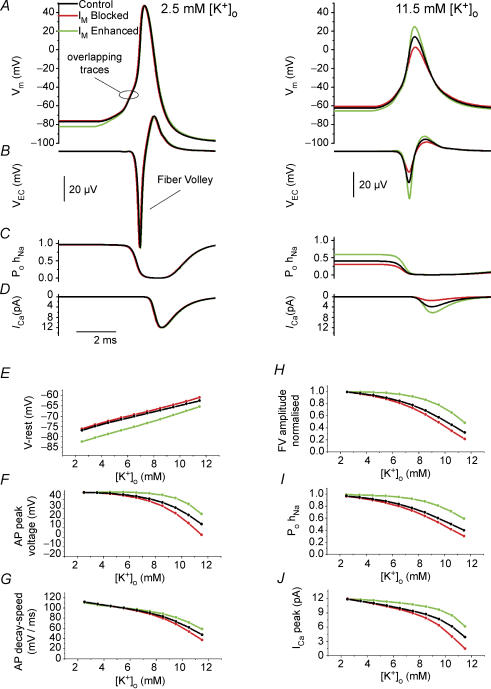

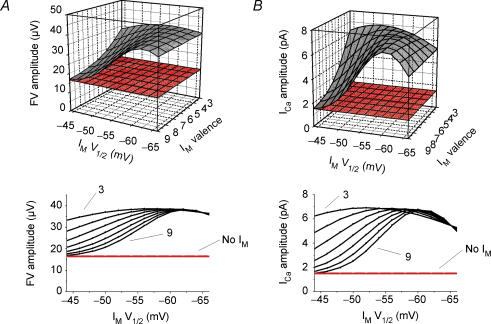

Figure 5. Computational modelling of the presynaptic intracellular response to IM modulation, based on extracellular data.

In the axon model, an action potential was evoked by an intracellular short current pulse (1 ms duration), 600 μm from the soma, and recorded 200 μm orthodromically from the initiation site. A–D, various responses in either 2.5 mm (left panels) or 11.5 mm[K+]o (right panels) in control conditions (black) and when IM was either removed (red) or enhanced by a negative shift in its activation curve (green). From top to bottom: A, intracellular potential (Vm); B, extracellular potential (VEC); C, open probability of INa inactivation particle (PohNa); and D, the Ca2+ current during the action potential (ICa). E–J, same simulation as in A–D, but repeated for various [K+]o values, ranging from 2.5 to 11.5 mm.E, resting membrane potential V-rest. F, action potential peak voltage. G, rate of action potential repolarization (decay speed). H, normalized FV amplitude. I, open probability of the INa inactivation particle (PohNa). J, peak Ca2+ current, ICa, in response to the action potential.

Results

Effect of M-channel blocker XE991 on presynaptic compound action potentials in stratum radiatum is [K+]o dependent

We recorded extracellular field potentials in stratum radiatum of the CA1 area. This technique has the advantage that it allows recording of both the presynaptic compound action potential or FV and the fEPSP (Andersen et al. 1978; Laerum & Storm, 1994). Figure 1Aa shows the FV (inset) recorded in standard extracellular K+ concentration, [K+]o (2.5 mm). Fast synaptic transmission was blocked by bath application of glutamate- and GABAA-receptor antagonists (100 μm DNQX, 100 μmdl-APV and 10 μm bicuculline free base). Application of 10 μm XE991, a selective blocker of M-channels (Wang et al. 1998), did not affect the amplitude of the FV, as illustrated by the average time course of the normalized FV amplitude (Fig. 1Aa, n = 5). This result is not unexpected since M-currents activate and deactivate slowly and their conductance density in CA1 pyramidal somata is too small to affect the action potential (Storm, 1989; Yue & Yaari, 2004; Gu et al. 2005). This is also likely to be the case in axons. In addition, since M-channels only start to activate from >−65 mV, and there are indications that the in vitro axonal membrane potential is quite hyperpolarized (∼−80 mV) (Engel & Jonas, 2005), it is likely that M-channels do not contribute to the axonal resting membrane potential. However, if the membrane is depolarized, e.g. as would occur during an activity-induced increase of [K+]o, the M-channels could be tonically activated. Somatic recordings indicate that increasing [K+]o from 3.5 to ∼11 mm depolarizes the resting membrane potential in hippocampal CA3 pyramidal cells by ∼15 mV, to ∼−60 mV (Fig. S3A). At this potential, M-channels are likely to be activated.

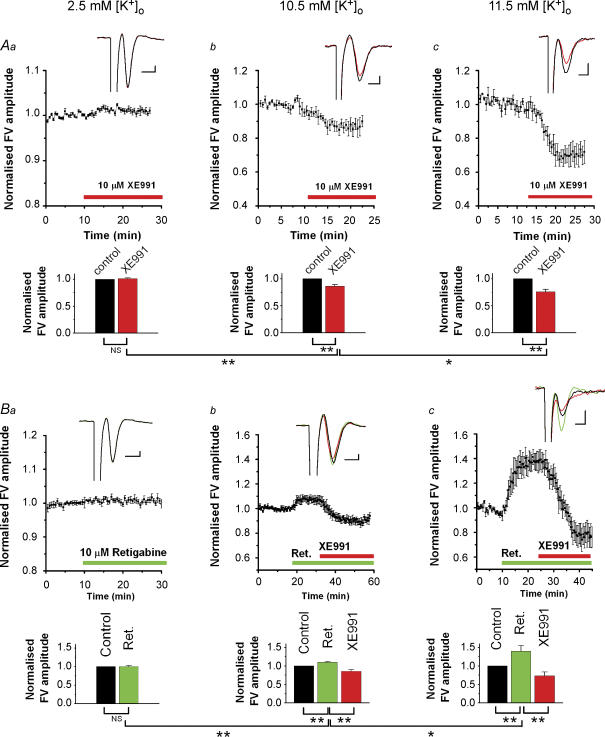

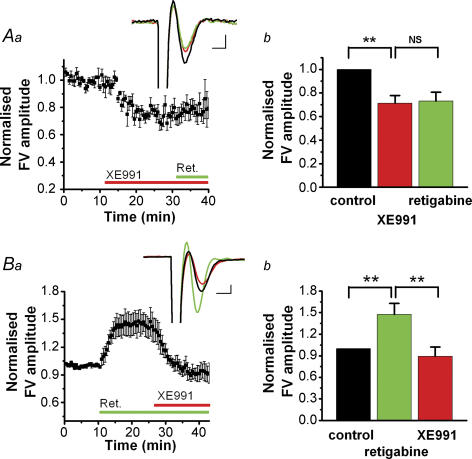

Figure 1. In stratum radiatum, XE991 reduced, and retigabine increased, the presynaptic compound action potential (FV) in an [K+]o-dependent manner.

Aa–c, summary time course of the effect of the M-channel blocker XE991 on the FV amplitude (mean ± s.e.m.) recorded in stratum radiatum in response to stimulation of presynaptic fibres in stratum radiatum. The effects of XE991 at three different [K+]o levels are shown: 2.5 mm (a, n = 5), 10.5 mm (b, n = 5) and 11.5 mm (c, n = 5). Insets show the average of 5 consecutive sweeps of the FV before (black) and after (red) application of 10 μm XE991. Bars show the summary of the XE991 effects on the FV amplitude (mean ± s.e.m.) as shown in Aa–c, respectively. Ba–c, similar to Aa–c, but the M-channel opener retigabine was added before XE991 (a, n = 5; b, n = 5; c, n = 5). NS, P > 0.05; *0.01 < P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Scale bars for insets in Aa–c and Ba–c: 1 ms, 0.1 mV. All experiments were performed in the presence of blockers of synaptic transmission: 50 μm DNQX, 50 μmdl-APV and 5 μm bicuculline free base.

Raising [K+]o reduced the FV peak, probably because of depolarization-induced inactivation of presynaptic Na+ channels and a reduced driving force for Na+ ions (Hablitz & Lundervold, 1981; Poolos et al. 1987; Meeks & Mennerick, 2004). Furthermore, when [K+]o was ∼10 mm, application of XE991 caused a clear reduction of the FV amplitude (Fig. 1Ab, [K+]o = 10.5 mm, n = 5), and the effect of XE991 was markedly larger when [K+]o was raised slightly more, to 11.5 mm [K+]o (Fig. 1Ac, n = 5). Clear effects of XE991 on the FV were observed for [K+]o levels ≥7 mm, but no effects were seen for [K+]o ≤5 mm (data not shown).

One might naively expect that blocking voltage-gated K+ channels would increase the compound spike by depolarizing axons towards the spike threshold. On the other hand, one might also expect that IM, when active at the resting membrane potential in elevated [K+]o, controls the steady-state level of Na+ channel inactivation. Blocking IM would then result in a depolarization that would inactivate more Na+ channels, thus reducing the Na+ spike current and the FV amplitude. These ideas were tested theoretically by numerical modelling (see below; Fig. 5).

Effect of M-channel opener retigabine on presynaptic compound action potentials in stratum radiatum is [K+]o dependent

Although XE991 is considered to be a highly selective M-channel blocker, we used also a second Kv7/KCNQ/M-channel-selective compound to ensure that the observed effects were not due to other ion channels. Thus, we repeated the experimental protocol of Fig. 1Aa–c with retigabine, a drug that opens M-channels by shifting their steady-state activation curve towards more negative potentials (Tatulian et al. 2001). In 2.5 mm [K+]o, retigabine (10 μm) had no effect on the FV amplitude, as illustrated by the average time course of the normalized FV amplitude (Fig. 1Ba, n = 5). In 10.5 mm [K+]o, however, retigabine clearly increased the FV amplitude, and subsequent coapplication of 10 μm XE991 decreased the FV amplitude to below the baseline at the start of the experiment (Fig. 1Bb, n = 5). Again, the effect of retigabine on the FV amplitude was strongly correlated with [K+]o, as indicated by the considerably larger effect in 11.5 mm [K+]o (Fig. 1Bc, n = 5) than in 10.5 mm [K+]o (Fig. 1Bb).

Some reports have suggested that higher concentrations of retigabine (∼100 μm) have side-effects, such as reducing Na+, Ca2+ and kainate currents and potentiating GABA-induced currents (Rundfeldt & Netzer, 2000; Otto et al. 2002). However, it is unlikely that retigabine exerted side-effects in our experimental conditions since we used only 10 μm retigabine, and it was always applied in the presence of glutamatergic and GABAergic receptor antagonists. Nevertheless, to further test for possible side-effects, we added retigabine after applying XE991, in 11.5 mm [K+]o (n = 5, data not shown). XE991 reduced the FV amplitude but subsequent application of retigabine had no apparent effect on the FV, thus indicating that the observed retigabine effect is likely to be mediated only by M-channels. We also obtained similar results when applying retigabine in the presence of 20 μm linopirdine, another M-channel blocker (n = 2, data not shown).

Effect of M-channel blocker XE991 on synaptic transmission in standard [K+]o

Having established the existence of axonal IM, we tested whether this current controls transmitter release by recording fEPSPs in stratum radiatum of CA1. Extracellular fEPSP recording has the advantage over somatic EPSP recordings, that the fEPSPs are recorded close to their site of origin (i.e. the dendritic synapses in stratum radiatum) and should therefore be less distorted by ionic conductances that attenuate and modify the EPSPs on their way from the dendrites to the soma (Andreasen & Lambert, 1995; Hoffman et al. 1997).

We stimulated the axons in stratum radiatum with a train of brief (100 μs) current pulses at 50 Hz over 400 ms (online Supplemental material, Fig. S1), in the presence of GABAA and NMDA receptor blockers (5 μm bicuculline and 50 μmdl-APV) (see Methods). The stimulation intensity was adjusted just below the level where population spikes started to appear on top of the fEPSPs. Figure S1Aa, upper panel, shows the entire response, while the lower panels show details of the FV and fEPSP following the first and last stimulus in the train. Application of 10 μm XE991 did not affect the FVs or the fEPSPs. Similar results were obtained in all five experiments performed in this way. Figure S1Ba and b shows the average time course of the parameters of the first (left) and last (right) FV and fEPSP in the train, respectively. The same outcome was obtained without bath application of dl-APV (n = 4, data not shown). Also, field stimulation at 100 Hz for 50 ms, without bicuculline (n = 2, data not shown), gave similar results. These data indicate that IM has little or no effect on glutamatergic transmission in stratum radiatum of CA1 under basal conditions. In contrast, when there were clear population spikes on top of the fEPSPs (data not shown), application of XE991 clearly increased the population spike amplitude, indicating that the postsynaptic excitability, but not the fEPSPs, was increased.

Effect of XE991 and retigabine on synaptic transmission in elevated [K+]o

Next, we tested whether M-channels can regulate synaptic transmission in elevated K+ concentrations, by repeating experiments like those shown in Fig. 1, in 11.5 mm [K+]o, in the absence of DNQX to leave the fEPSPs intact. Under these conditions, application of 10 μm XE991 reduced both the fEPSP initial slope and the FV amplitude (Fig. 2Aa). Furthermore, the effect of XE991 showed a similar drug time course on both parameters (Fig. 2Aa). Averages of 10 consecutive field potential traces before and after XE991 application are shown in Fig. 2Ab. Similar results were obtained in all five experiments performed in this way (Fig. 2Ac; normalized fEPSP initial slope).

Figure 2. In stratum radiatum, XE991 reduced and retigabine increased the field postsynaptic responses in elevated [K+]o (11.5 mM).

All responses were evoked by stimulation of presynaptic fibres in stratum radiatum and were recorded in stratum radiatum in the presence of 11.5 mm[K+]o, 50 μm dl-APV and 5 μm bicuculline. Aa, effect of 10 μm XE991 on fEPSP initial slope (upper panel) and fibre volley (FV) amplitude (lower panel). Ab, average of 5 consecutive traces before (black) and after (red) application of XE991 (same experiment as in Aa). Ac, summary time course (mean ± s.e.m.) of experiments performed as in Aa–c (n = 5). XE991 reduced the fEPSP initial slope by a factor 0.43 ± 0.15. Ba, effect of 10 μm retigabine and subsequent application of 10 μm XE991 on fEPSP initial slope and FV amplitude. Bb, average of 5 consecutive traces before (black) and after application of retigabine (green), and XE991 (red) (same experiment as in Ba). Bc, summary time course (mean ± s.e.m.) of experiments obtained as in Ba and b (n = 5). Retigabine increased the fEPSP initial slope by a factor 3.1 ± 1.0 and subsequent application of XE991 reduced the fEPSP initial slope by a factor 0.56 ± 0.22 compared with the control (*0.01 < P < 0.05).

Next, we applied retigabine followed by XE991 (Fig. 2Ba–c). Retigabine strongly increased the fEPSP initial slope and FV amplitude (Fig. 2Ba), whereas subsequent application of XE991 reduced the fEPSP initial slope to below the baseline values. Averaged traces of the responses obtained before drug application (black), after retigabine application (green) and after XE991 application (red) are shown in Fig. 2Bb (same experiment as Fig. 2Ba). This particular experiment showed the strongest drug effect of all five experiments of this kind. The summary data for all experiments are shown in Fig. 2Bc (n = 5).

To further test whether the effects of retigabine and XE991 on the fEPSP were due to pre- or postsynaptic IM, we performed whole-cell recordings from CA1 pyramidal neurons (Fig. 3). We eliminated the postsynaptic IM by replacing all K+ in the patch pipette with Cs+ ions (140 mm), to which M-channels are largely impermeable (Tallent & Siggins, 1997; Lancaster et al. 2001). EPSPs were evoked by stimulation of the presynaptic fibres in stratum radiatum, in the presence of dl-APV and bicuculline, while the membrane potential of the target cell was maintained at −78 mV by DC injection. In 11.5 mm [K+]o, application of XE991 clearly reduced the EPSP amplitude (n = 5, Fig. 3Aa and b) whereas retigabine increased the EPSP in all cells tested (n = 5, Fig. 3Ba and b). However in recordings with standard (2.5 mm) [K+]o and Cs+ (but no retigabine), 10 μm XE991 had no apparent effect on the EPSP amplitude (n = 5, P > 0.05, data not shown). These results are similar to the results obtained by field potential recording (Figs 1 and 2), confirming the presynaptic nature of XE991 and retigabine effects on synaptic transmission. In addition, we also measured the paired pulse facilitation (PPF), but found that application of 10 μm retigabine produced no significant difference (n = 5; control, PPF = 127 ± 5%; retigabine, PPF = 117 ± 8%; P > 0.05).

Effect of XE991 and retigabine on presynaptic compound action potentials in stratum lacunosum moleculare

We next asked: are other glutamatergic fibres in the hippocampus also equipped with functional M-channels? The distal dendrites of the CA1 pyramidal neurons, which are located in stratum lacunosum moleculare (str. L-M), receive excitatory synapses from entorhinal cortex (EC) layer III neurons, as well as from subcortical sources (Witter et al. 1988; Yeckel & Berger, 1990). Although this pathway has received far less attention than the Schaffer collaterals, recent evidence indicates that the EC-layer-III–CA1 pathway conveys spatial information from the neocortex, thus bypassing the dentate gyrus and area CA3. Thus (Brun et al. 2002) found that CA1 pyramidal cells that were isolated from area CA3 showed stable place fields with a theta-modulated discharge.

To test whether this population of unmyelinated axons also contains functional M-channels, we stimulated presynaptic fibres in the str. L-M and recorded the FVs orthodromically (∼300 μm) in the same layer (similar protocol as in Fig. 1, with 11.5 mm [K+]o). Since Schaffer collaterals do not enter the str. L-M to any appreciable extent (Amaral & Witter, 1989), the FV probably represents to a large extent action potentials in axons from layer III entorhinal neurons.

Application of 10 μm XE991 reduced the FV amplitude as illustrated in Fig. 4Aa and b (n = 5). Subsequent application of 10 μm retigabine did not further affect the FV, indicating that retigabine did not have any appreciable non-specific M-channel-independent effects on the FV (Fig. 4Aa and b). Applying retigabine first increased the FV amplitude and subsequent application of XE991 decreased the FV to values below baseline (Fig. 4Ba and b). The results from str. L-M were qualitatively and quantitatively very similar to the results obtained in stratum radiatum (Fig. 1). We also performed field potential recordings in which the fEPSPs were studied in parallel with the FVs (similar protocol as in Fig. 2; retigabine followed by application of XE991 in 11.5 mm [K+]o). These results were also very similar to those from stratum radiatum (n = 2; data not shown).

Figure 4. In stratum lacunosum moleculare, XE991 reduced and retigabine increased the presynaptic compound action potentials (FV) in elevated [K+]o (11.5 mM).

Aa, summary time course (mean ± s.e.m.) of the FV amplitude recorded in the stratum lacunosum moleculare in response to stimulation of presynaptic fibres in stratum lacunosum moleculare. Inset shows average of 5 consecutive traces of the FV in control conditions (black), after application of 10 μm XE991 (red) and followed by application of 10 μm retigabine (green). Ab, XE991 decreased the FV amplitude by a factor 0.71 ± 0.03. Subsequent application of retigabine did not further affect the FV (0.73 ± 0.02). Ba, as in Aa, but retigabine was applied before XE991. Bb, retigabine increased the FV by a factor 1.47 ± 0.16 while subsequent application of XE991 decreased the FV by a factor 0.89 ± 0.13 compared with the control (**P < 0.01; NS, not significant). DNQX (50 μm), dl-APV (50 μm) and bicuculline (5 μm) were added more than10 min before the onset of each recordings. Scale bars for insets in Aa and Ba: 1 ms, 0.05 mV.

Computational model of the effect of M-channel blockers and openers on axonal excitability

The unmyelinated Schaffer collateral axons and the fibres in the str. L-M, being among the thinnest in the central nervous system, are inaccessible to intracellular recording. Therefore we used the more indirect methods of field and postsynaptic whole-cell recording to test for the existence of axonal M-channels, and explored their functions in synaptic transmission. To try to correlate our indirect observations with axonal intracellular electrical activity, and to explore how M-channels may modulate axonal excitability and Ca2+ influx, we performed numerical simulations with a model of an axon.

The XE991 and retigabine effects were simulated by removing IM and enhancing IM by shifting its steady-state activation curve towards more negative potentials, respectively (Tatulian et al. 2001; see Supplemental material). We stimulated the model axon by a brief (1 ms) intracellular current pulse applied 600 μm from the soma. We studied the action potential, FV, INa kinetics and changes in spike-evoked Ca2+ current (ICa) 200 μm orthodromically from the stimulation site.

First we simulated the effects of retigabine and XE991 with either 2.5 or 11.5 mm [K+]o. As shown in Fig. 5A–D, we studied the effects of removal (red trace) or enhancement of IM (green trace) on the membrane potential (Vm, Fig. 5A), the extracellular voltage response (VEC, Fig. 5B), the open probability of the INa inactivation particle (PohNa, Fig. 5C), and the ICa (Fig. 5D). As in our experiments with XE991 and retigabine, removal or enhancement of IM in the model had no effect on the FV and ICa in 2.5 mm [K+]o (traces overlap), whereas in 11.5 mm [K+]o, both manipulations exerted similar effects on the FV as observed in the slice experiments (Fig. 5B, right panel, cf. Fig. 1).

We propose the following mechanisms to explain our observations. Initially, raising [K+]o causes a membrane depolarization (Fig. 5E) that reduces the spike amplitude (Fig. 5F) and repolarisation rate (Fig. 5G). The two latter effects are reflected extracellularly as smaller amplitudes of the negative (Fig. 5H) and positive (‘overshoot’, compare FVs in Fig. 5B) phases of the FVs, respectively. The negative peak of the FV reflects the rate of depolarization during the action potential upstroke, whereas the FV ‘overshoot’ reflects the rate of spike repolarization (Henze et al. 2000). The main reason for the reduced spike amplitude with increasing [K+]o (Fig. 5F) is increased steady state inactivation of INa (PohNa in Fig. 5I and C) due to depolarization of the resting potential. The accompanying spike broadening results from multiple factors, mainly: (1) inactivation of IK at the resting potential, and (2) reduced driving force for K+. The net result of increasing [K+]o is a reduction of the spike-evoked ICa (Fig. 5J). However, the changes in ICa in the model, probably provides only a qualitative prediction of the experimental changes in the fEPSP. After our simulations were performed, a recent paper showed very similar effects of raising [K+]o on the spike parameters in mossy fibre boutons (see supplement Fig. 3C in Alle & Geiger, 2006).

IM starts to activate from ∼−65 mV and is considered too small and activates too slowly to contribute appreciably to spike repolarization (Storm, 1987, 1989). In standard [K+]o, the resting Vm is too hyperpolarized for IM to activate, but once the membrane is sufficiently depolarized, for example by an increase in [K+]o, IM will become an increasingly important contributor to the resting potential (Fig. 5E). Since the activation curve of IM spans approximately the same Vm range as the inactivation curve of INa, modulation of IM can have a particularly strong influence on axonal excitability. Note that the membrane resting potential is dominated by the leak reversal potential (Erev). The leak in the model predominantly conducts K+ and only little Na+ and Cl− ions (see Methods), while the M-channels are solely K+ permeable. Therefore, the reversal potential of IM is always more negative than that of the leak conductance, in the range of [K+]o that we explored. This is the reason why modulation of IM could affect the resting membrane potential.

Thus, at depolarized potentials, XE991 will depolarize and retigabine will hyperpolarize the axon membrane (Fig. 5E) leading to substantial changes in the proportion of available (de-inactivated) Na+ channels (Fig. 5I, PohNa). Thereby, IM can modulate the spike amplitude (Fig. 5F) and, hence, the Ca2+ influx (Fig. 5J). Since high-threshold Ca2+ channels (P/Q- and N-type) start to activate at ∼−10 mV and are fully opened ∼+30 mV (Magee & Johnston, 1995; Bischofberger et al. 2002), it is not surprising that the Ca2+ influx is highly sensitive to the spike amplitude.

The IM kinetics described in the experimental literature are quite diverse and depend on the subunit composition of the M-channels and the physical recording conditions. Furthermore, the kinetics of M-channels are susceptible to neuromodulation. Therefore we explored whether the results we obtained in elevated [K+]o (Fig. 5) hold for a wide range of values for the parameters that determine the IM activation curve, i.e. V1/2 and valence (steepness) (Fig. 6). The simulations were run to measure the FV (Fig. 6A) and the spike evoked ICa (Fig. 6B) for a combination of V1/2 and valence values that span a wide range of experimentally reported values. In all cases, the FV and ICa amplitudes were smaller when IM was blocked (red) compared with the control situation (grey). This shows that our results are qualitatively robust.

Figure 6. In the model, the effects of IM on the presynaptic compound action potential (FV) and spike-evoked ICa in elevated [K+]o (11.5 mM) is robust for a wide range of IM parameter values.

An action potential was evoked by an intracellular short current pulse (1 ms duration) in the axon model, 600 μm from the soma, and recorded 200 μm from the initiation site (in the orthodromic direction). FV amplitude (A) and spike-evoked ICa peak amplitude (B) are shown as functions of the IM steady state activation curve parameters V1/2 and valence (steepness). Grey, control; red, no IM

Similarly, we also explored the effects of changing the INa inactivation curve, which is another critical factor (Fig. S2A1 and 2). We tested a range of inactivation curve parameter values, including those obtained experimentally from hippocampal pyramidal neurons, e.g. from Magee & Johnston (1995) and Gasparini & Magee (2002). The differences (Δ) in FV and ICa amplitudes with and without IM are plotted. ΔFV and ΔICa were positive for all values (although sometimes very small), meaning that in all cases the FV and ICa was reduced after blocking IM

A similar approach was used to explore how the V1/2 of IM activation in relation to the V1/2 of INa inactivation affects the outcome of our results (see Supplemental material, Fig. S2B1 and 2). We also explored whether changes in V1/2 of ICa and its time constant of activation could make any qualitative changes in our conclusion (Fig. S2C1). In all cases ΔFV and ΔICa were positive, although sometimes small. Thus overall, our simulations indicate that our results are robust, i.e. that presynaptic M-channels enhance presynaptic action potentials, Ca2+-influx and transmitter release under a variety of conditions.

Effect of blocking or enhancing IM on the somatic resting membrane potential in 11.5 mm [K+]o

We also tested experimentally whether retigabine and XE991 could modulate the resting membrane potential recorded in CA3 pyramidal cell somata under similar conditions, i.e. in 11.5 mm [K+]o. Previous tests in standard 2.5 mm [K+]o have shown that, in cells depolarized beyond −65 mV by current injection, retigabine can cause a negative shift in the somatic membrane potential up to ∼−9 mV (Tatulian et al. 2001), whereas XE991 produced depolarization (Gu et al. 2005).

However, we found no effect of either retigabine or XE991 on the resting membrane potential or spike parameters in 11.5 mm [K+]o (Fig. S3A and B). Interestingly, also the model showed only miniscule effects of blocking or enhancing IM at the soma, in clear contrast to the pronounced effects in the axon (Fig. S3C and D). The main reason for this difference in the model is that the input resistance in the axon (2.1 GΩ) is much higher than at the soma (73 MΩ), because the latter has a large dendritic load. Therefore, small subthreshold currents like IM have much stronger impact on the membrane potential in the axon than in the soma. This suggests that IM plays different functional roles in these subcellular compartments.

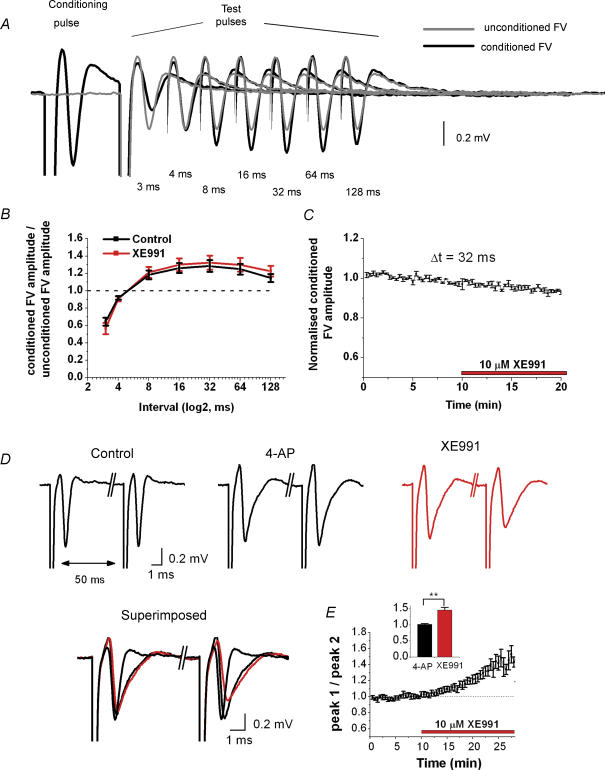

IM and activity-dependent excitability in soma and axon

In CA1 pyramidal cell somata, single spikes are followed by an afterdepolarization (ADP) and medium and slow afterhyperpolarization (mAHP and sAHP, respectively) (Storm, 1989). The mAHP is due to activation of IM (Gu et al. 2005), and IM also limits the ADP and prevents burst generation in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons (Yue & Yaari, 2004; Gu et al. 2005). Thus, M-channel blockade enhances the ADP, sometimes causing it to trigger a burst of spikes (Yue & Yaari, 2004). In CA3 pyramidal somata, an action potential is followed by an even more prominent ADP (Wong & Prince, 1981). Furthermore, field potential recordings suggest that action potentials in Schaffer collateral axons may as well be followed by an ADP that could affect spike propagation and synaptic release (Wigstrom & Gustafsson, 1981). The occurrence of an ADP both in the soma and axon of the same neuron was nicely illustrated in granule cells and their mossy fibres by Geiger & Jonas (2000). Thus, this phenomenon may be widespread.

First we tested whether IM affects the ADP at CA3 pyramidal neuron somata. Although IM is known to affect somatic excitability in these neurons (Charpak et al. 1990), the particular effect of IM on the ADP has been unclear because the lack of specific blockers. We used sharp-electrode recording to prevent rundown of IM, which can be a problem in whole-cell recordings (Gu et al. 2005). The cells had resting potentials near −63 mV (−63.1 ± 2.2 mV, n = 7) and an average input resistance of 66 ± 9.3 MΩ. A typical example (Fig. 7Aa) shows how a single action potential evoked by a brief (10 ms) current pulse is followed by a prominent ADP, mAHP and sAHP (see arrows). Application of 10 μm XE991 increased the ADP and the cell converted from single action potential firing to burst firing. Figure 7B shows the time course of the effect: blockade of IM enhanced the ADP, eventually causing bursts of 2–4 spikes. The ADP area increased from 254 ± 38 mV ms−1 to 433 ± 87 mV ms−1 (n = 6, P = 0.03).

To test whether IM in Schaffer collaterals can affect putative axonal ADPs or AHPs, we used a previously described stimulation protocol (Wigstrom & Gustafsson, 1981; Soleng et al. 2004) (Fig. 8). FVs were evoked by a (80 μs) ‘test’ stimulas from a stimulation electrode in stratum radiatum, in the presence of synaptic blockers (DNQX, dl-APV and bicuculline) (Fig. 8A). This stimulus was repeated every 20 s, every being preceded by a ‘conditioning’ stimulus of longer duration (120 μs). The interval between the two stimuli was varied (Fig. 8A and B). We compared the FV with and without a conditioning pulse. When a test pulse followed shortly (3–4 ms) after a conditioning pulse, it evoked smaller FVs than those not preceded by a conditioning pulse. In contrast, FVs evoked after longer intervals (8–128 ms) were larger than FVs evoked without a conditioning pulse (Fig. 8A and B, black). The ‘subnormal’ response for short intervals is thought to reflect a reduction of axonal excitability due to refractoriness, whereas the ‘super-normal’ response may reflect an increased excitability due to an ADP (Wigstrom & Gustafsson, 1981; Soleng et al. 2004). Application of XE991 affected neither the subnormal nor the supernormal FV in any of the five slices tested, for any of the intervals (Fig. 8B). This is also illustrated in Fig. 8C, which shows the time course of the conditioned FV amplitude for an interval of 32 ms (n = 5).

Figure 8. The M-channel blocker XE991 affects paired-pulse modulation of the presynaptic compound action potential (FV) in stratum radiatum after spike broadening (2.5 mM [K+]o).

A, fibre volleys (FVs) recorded under control conditions in response to test pulses (80 μs duration), preceded by a stronger conditioning pulse (120 μs duration) at various time intervals (black traces). The FV was facilitated maximally for a pulse interval of ∼32 ms, compared with unconditioned FVs (grey traces). For clarity, the stimulus artifacts are deleted for stimulation intervals 4–128 ms. DNQX (50 μm), dl-APV (50 μm) and bicuculline (5 μm) were present in the bath throughout the experiment. B, the ratio between conditioned and unconditioned FV amplitude is plotted against interstimulus interval (logarithmic axis). The values obtained under control conditions (black, n = 5) or in the presence of 10 μm XE991 (red, n = 5) were not statistically different for any of the tested intervals. C, summary time course of the conditioned FV amplitude measurements during application of 10 μm XE991, for an interstimulus interval of 32 ms (mean ± s.e.m., n = 5). D, fibre volleys evoked by paired-pulse stimulation in stratum radiatum (interval, 50 ms). Bath application of 200 μm 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) broadened the FV, and subsequent application of 10 μm XE991 caused depression of the second FV (red). E, average time course of the FV1/FV2 amplitude ratio. This ratio increased from 1.00 ± 0.03 to 1.50 ± 0.10 (n = 6, P = 0.0008).

Thus, we found no effect of XE991 on the refractory period in Schaffer collaterals. This may seem surprising, since M-channel blockade increases the ADP in CA3 pyramidal somata. This difference may be explained if the action potentials are narrower and/or the resting membrane potential is more negative in the axons than in the soma, so that the axonal IM is not substantially activated during the spike or ADP. Possibly, the use of invasive techniques such as patch- and sharp-electrode recording, might contribute to a more depolarized resting potential in the soma, thus promoting effects of IM that were not detected in the axons by our non-invasive field recordings. Alternatively, IM may be less activated in the axons than in somata, because IM kinetics may differ. Interestingly Geiger & Jonas (2000) showed that the action potential duration in the mossy fibre axons is only half the duration seen in the granule cell somata, due to the high density of Kv1 channels in the axons. There is probably a similar difference in the action potential duration between the CA3 pyramidal somata and their Schaffer collateral axons (Hu et al. 2001). This is indicated by the finding that BK-type K+ channels, which activate late during the somatic action potential and contribute strongly to its final repolarization (Storm, 1987; Shao et al. 1999), normally have no detectable effect on the action potentials in Schaffer axons, presumably because the axonal spike is too brief to allow the BK channels to open (Hu et al. 2001). Furthermore, like the mossy fibres, Schaffer collaterals have a high density of Kv1 channels (Sheng et al. 1993).

In many axons, spike repolarization is mainly caused by Kv1 channels. These channels can be modulated by an inactivation process that is strongly voltage dependent in the subthreshold range. Therefore, subthreshold depolarization and repetitive firing can cause the action potentials to broaden considerably due to Kv1 channel inactivation (see, e.g. Fig. 3 in Shu et al. 2006; and Fig. 3 in Geiger & Jonas, 2000). Furthermore, Shu et al. (2006) showed that during epileptiform activity, action potentials are dramatically broadened and propagate along unmeylinated cortical axons. Thus the duration of the presynaptic spike is not fixed but is subject to short-term regulation.

To test whether spike broadening can lead to activation of IM, and whether IM then contributes to the refractory period in the Schaffer collaterals, we broadened the axonal action potentials by applying a low dose of 4-AP (200 μm), which partly blocks Kv1 channels. In the presence of 4-AP, and also DNQX, APV and bicuculline for blocking synaptic responses, we stimulated presynaptic fibres with paired pulses (50 ms interval) while recording field potentials in stratum radiatum of CA1. According to our observations in CA1 somata (Gu et al. 2005) the second stimulus in each pair would be expected to coincide with the peak M-conductance following the action potential evoked by the first stimulus. Figure 8D shows that 4-AP approximately doubled the half-width of the FV. When XE991 was subsequently added, it caused a clear depression of the second FV amplitude, but had no detectable effect on the amplitude or the half-width of the first FV (both: P > 0.05, n = 6), although it increased the half-width of the second FV. These observations suggest that IM was activated by the axonal action potential that had been broadened by 4-AP, thus contributing to spike repolarization and/or an IM-dependent after-hyperpolarization (mAHP) in the axon. Thus, IM would limit the refractoriness due to Na+ channel inactivation following the first action potential. Blockade of IM therefore caused a reduction of the second FV.

Discussion

This study provides evidence that functional Kv7/KCNQ/M-channels exist in unmyelinated axons in the brain. These results are in accordance with immunocytochemical data indicating the presence of Kv7/KCNQ/M-channel proteins in both myelinated and unmyelinated axons in the brain (Devaux et al. 2004), but to our knowledge physiological evidence for their function has not been obtained previously. However, functional data from peripheral myelinated axons have appeared (Devaux et al. 2004).

We found that substances that block or open M-channels caused changes in axonal action potentials (measured as the FV), as well as in transmitter release, when tested in the presence of elevated [K+]o. Perhaps surprisingly, however, our results indicate that the presynaptic M-channels enhance the axonal action potential (FV) and transmitter release under these conditions, although a presynaptic K+ current is normally expected to reduce excitability and release (see, e.g. Martire et al. 2004). Similar effects were found at two different glutamatergic pathways in the CA1 hippocampal area: (1) axons in stratum radiatum (containing Schaffer collaterals) and (2) axons in str. L-M (containing the direct entorhinal–CA1 pathway). Computational analysis with an axon model revealed that presynaptic (axonal) IM, when activated during axonal depolarization (for example during an activity-induced rise in [K+]o), can reduce the inactivation of Na+ channels. Thereby, it can affect action potential amplitude and, hence, spike-induced Ca2+ influx and transmitter release.

Finally, we showed that selectively blocking IM increases the ADP in CA3 pyramidal neuron somata, leading to a transition from single spike firing to bursting. In contrast, we found no contribution of IM to the refractory period in Schaffer collaterals unless the axonal spikes were broadened.

Presynaptic M-channels in the hippocampus

Several lines of evidence support our conclusion that there are functional M-channels in CA1 unmyelinated glutamatergic axons. (1) We found that M-channel blockers (XE991, linopirdine) reduced the FV amplitude and fEPSP, in elevated [K+]o, while the M-channel opener retigabine had opposite effects. (2) XE991 reduced, and retigabine increased the EPSPs also when postsynaptic K+ currents were eliminated by intracellular Cs+, during whole-cell recording from CA1 pyramidal neurons in elevated [K+]o. In addition, voltage-clamp recordings have shown that the activation range of IM resembles the steady-state inactivation range of the spike-generating Na+ current, INa (Sah et al. 1988; Hu et al. 2002), and our model showed that IM is therefore well suited for modulating spike amplitude, Ca2+ influx and, hence, synaptic transmission.

However, our model does not exclude other contributing factors. (1) Blockade or enhancement of M-channels might possibly affect spike propagation reliability (Allen & Stevens, 1994; Cox et al. 2000; Debanne, 2004), which was not examined by our model. However, others have found that spike propagation in cortical axonal arbors is reliable for single stimuli at similarly high [K+]o levels as in our study, although the reliability is reduced during high-frequency stimulation (Meeks & Mennerick, 2004). Furthermore, in our experiments, the distance between the stimulation and recording electrodes was rather short (∼300 μm, probably spanning only few branch points) thus favouring a high probability for spikes to reach the recording site. Also, spike propagation from soma to axon terminals in hippocampal neurons is reliable even when INa is attenuated by 20 nm TTX or by reducing [Na+]o from 150 to ∼60 mm, which strongly reduced the spike amplitude (Mackenzie & Murphy, 1998). (2) Our model is limited to one axon, while the field potentials reflect stimulation of hundreds of axons (Raastad & Shepherd, 2003). XE991 will probably increase the number of fibres stimulated by reducing the current necessary to reach firing threshold, whereas retigabine may do the opposite. Therefore, our experiments probably tend to underestimate the XE991 and retigabine effects on the intracellular spikes and EPSPs.

Are M-channels located in presynaptic boutons or extra-synaptically, i.e. in the axon shaft? The techniques used in this study do not provide an answer to this question. Recent immunohistochemistry data (Devaux et al. 2004) indicate that KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 subunits exist predominantly in axon initial segments (IS) of CA1 and CA3 pyramidal neurons. Earlier electron microscope data [Fieles WE et al. Soc Neuroscience Abstr. 2001 (812.32), 2002 (438.8)]) suggested that presynaptic KCNQ2 but not KCNQ3 are associated with fibre pathways in the macaque monkey brain. In particular, KCNQ2 was found in nerve terminals of the cerebral cortex and hippocampus. Interestingly, Martire et al. (2004) showed that release of tritiated norepinephrine, aspartate and GABA from isolated hippocampal synaptosomes stimulated by adding 9 mm [K+]o could be modulated by retigabine and XE991. These effects were precluded by KCNQ2 but not by KCNQ3 antibodies. Thus, it appears that in the hippocampus, KCNQ2 is targeted to presynaptic terminals and is also coexpressed with KCNQ3 at axon initial segments. It is not yet clear whether these subunits are also exist in axon shafts. However, it seems unlikely that the exact distribution of channels between boutons and axon shafts would make much functional difference. Schaffer collateral axons form en-passant boutons interspaced at ∼3.7 μm intervals which are merely local swellings of the axon (Shepherd et al. 2002). These varicosities are likely to be equipotential with the axon, and M-channels may exert their function, as we have demonstrated here, regardless of whether they are located, for example, uniformly in the axon or only in the boutons.

Are there dendritic M-channels in CA1 pyramidal neurons?

XE991 had no apparent effect on a train of fEPSPs recorded in the dendritic layers under normal experimental conditions (Fig. S1). Even when [K+]o was moderately elevated, beyond the reported normal level of [K+]o in the brain (3.0–4.0 mm; Somjen, 2002) XE991 had no apparent effect on the fEPSPs. This may seem surprising in view of previous work indicating that M-channels may contribute to subthreshold synaptic integration (Hu et al. 2002). However, the finding that XE991 enhanced population spikes (data not shown) suggests an increased excitability at the IS/soma (Gu et al. 2005), provided that spikes are initiated there and propagate back into the dendrites (Stuart & Sakmann, 1994; Spruston et al. 1995). There are at least two possible explanations for our observations (Fig. S1). (1) Although our stimulation intensity was adjusted to keep the EPSPs just below threshold, the dendritic depolarization may not have been sufficiently large or long-lasting to substantially activate IM (however, see Magee, 1999). (2) The density of M-channels in the apical dendrites may be very low.

Several studies support the latter possibility. Immunocytochemical data indicate that KCNQ2/3 subunits in the hippocampus are predominantly associated with axon initial segments of pyramidal neurons (Devaux et al. 2004). Although earlier observations appeared to indicate targeting of these subunits primarily to somato-dendritic compartments rather than axons (Cooper et al. 2001), this staining pattern was later found to depend on aldehyde fixation of the tissue (Devaux et al. 2004). Similarly, in aldehyde-fixed tissue, KCNQ5 appears to be located in the soma and dendrites of hippocampal pyramidal cells (Yus-Najera et al. 2003). Although KCNQ5 can coassemble with KCNQ3 (but not with KCNQ2; Schroeder et al. 2000), a recent study showed that IM in CA1 pyramidal neurons was suppressed by ∼80% in mice expressing dominant negative KCNQ2 subunits (Peters et al. 2005). This indicates that KCNQ5 is likely to contribute only a minor component of the somatic IM in these cells. Also, a recent electron microscopy study detected KCNQ2 predominantly presynaptically and little postsynaptically in the hippocampus [Fieles et al. Soc Neuroscience Abstr. 2001 (812.32), 2002 (438.8)].

Furthermore, in CA1 pyramidal neurons, recordings of distal dendritic action potentials rarely show substantial AHPs (Poolos & Johnston, 1999; Stuart et al. 1999), in contrast to somatic action potentials that are followed by an IM-dependent mAHP (Storm, 1989; Gu et al. 2005). Besides, any AHPs observed in the dendrites are usually sensitive to Ih blockers (Stuart et al. 1999). In addition, our recordings from CA1 pyramidal cell dendrites have so far shown no evidence for a dendritic IM [Hu et al. FENS Forum Abstr. 2006 (A189.8)].

Thus, except for recordings of putative single M-channels with an atypical voltage-dependence in cell-attached dendritic patches (Chen & Johnston, 2004), there is so far little evidence for IM in dendrites of hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Further studies will be needed to clarify this issue.

Functional consequences of IM in unmyelinated axons in the brain

Our results indicate that presynaptic M-channels can enhance the axonal action potential (FV) and transmitter release, provided that the axons and terminals are sufficiently depolarized. In contrast, Martire et al. (2004) recently reported a seemingly opposite results. They used hippocampal synaptosomes as a model system to study how presynaptic M-channels regulate neurotransmitter release. By adding 9 mm [K+]o, they evoked depolarization-induced release of tritiated norepineprine, aspartate and GABA from the synaptosomes. Under these conditions, retigabine was found to reduce the release of each of these neurotransmitters, in sharp contrast to the increase in EPSPs that we saw (Fig. 2). Why did they find a seemingly opposite result compared with ours? We think the crucial difference is that K+-induced transmitter release from synaptosomes is not strictly dependent on action potentials, since it still occurs in the presence of TTX (Nicholls & Attwell, 1990), whereas transmitter release in slices (as well as in the intact brain) is entirely spike dependent. Thus, by opening more M-channels in the synaptosomes, retigabine will presumably reduce the [K+]o-induced depolarization, thus reducing the voltage-gated Ca2+ entry underlying the slow transmitter release. In contrast, opening M-channels in intact axons/terminals in slices will boost the spike-dependent release by reducing INa inactivation (Fig. 5). This is probably the mechanism that also operates under physiological conditions, in the intact brain, where glutamate release is normally spike-dependent. This interpretation is supported by the observation by Martire et al. (2004) that retigabine inhibited transmitter release even in 15 and 30 mm [K+]o, when the membrane is so depolarized that action potentials are abolished by INa inactivation.

We showed that a prerequisite for IM to contribute to transmitter release is sufficient presynaptic depolarization. Under which conditions does this happen in vivo? We suggest three mechanisms that probably can contribute individually or in synergy. (1) Estimates of resting [K+]o in rat brain tissue range from 2.5 to 4 mm (Somjen, 2002), but [K+]o in the nervous system is dynamically dependent on the amount of neuronal activity in different physiological and pathophysiological conditions. In anaesthetized rats, 2–5 Hz stimulation of the fimbria or entorhinal cortex leads to an increase of [K+]o in the CA1 area that reaches a ceiling of 9–12 mm (Krnjevic et al. 1980, 1982). Also, in hippocampal slices, a 10 Hz train of stimuli delivered to the Schaffer collaterals during ∼10 s causes the [K+]o to reach a plateau of ∼15 mm in area CA1 (Amiry-Moghaddam et al. 2003). In the hippocampus, it remains to be determined how [K+]o changes during various behavioural states of the animal, e.g. during theta oscillations or sharp wave activity when large populations of cells fire in synchrony. In pathophysiological conditions such as epileptic seizures, hypoxia and ischaemia, [K+]o levels can readily reach tens of millimoles (Somjen, 2001). During such peak levels of [K+]o, action potentials are probably abolished by severe depolarization-induced INa inactivation. (2) In addition to changes in [K+]o, activation of presynaptic ionotropic receptors influence the axonal resting potential (MacDermott et al. 1999). There has been a particular strong interest in how activation of presynaptic kainite, GABA and glycine receptors affect transmitter release through presynaptic depolarization (Schmitz et al. 2001; Ruiz et al. 2003; Kullmann et al. 2005; Awatramani et al. 2005). The Cl− reversal potential seems to be more depolarized (∼−40 mV) in axons than in peri-somatic regions, due to a lack of the KCl cotransporter 2 in the axon (Szabadics et al. 2006). Therefore, presynaptic inhibition through activation of GABAa receptors is thought to arise from shunting of the presynaptic action potential or depolarization-induced inactivation of Na+ and Ca2+ channels (Graham & Redman, 1994; Cattaert & El, 1999; Ruiz et al. 2003). Preliminary simulations with our model show that during activation of presynaptic GABAA receptors in standard 2.5 mm [K+]o, IM raises the firing threshold, but also increases the action potential amplitude (unpublished data). Because the driving force for IM is not reduced, these effects of IM are quite strong compared with its effect in elevated [K+]o. These results predict an experimentally unexplored role for IM in controlling the subthreshold membrane potential and thereby modulating presynaptic Na+ and Ca2+ currents. (3) Recently, while this paper was under revision, Alle & Geiger (2006) showed that subthreshold synaptic potentials from the granule cell dendrities can propagate hundreds of micrometres along the mossy fibre axons to their terminals. Such so-called EPreSPs can probably cause sufficient presynaptic subthreshold depolarization that presynaptic M-channels are activated and, thus, in turn contribute to shaping the EPreSPs. A similar phenomenon was recently shown in ferret prefrontal cortex layer 5 neurons (Shu et al. 2006).

Can IM play a role in frequency-dependent spike broadening? Geiger & Jonas (2000) showed that repetitive stimulation of mossy fibre axons caused a dramatic broadening of the action potential due to inactivation of Kv1 channels, thus producing increased Ca2+ influx and transmitter release (see Fig. 3 in Geiger & Jonas, 2000). Here we found that broadening the action potential with a low dose of 4-AP could activate IM following a single spike. Thus, it seems possible that presynaptic IM could act as a negative-feedback mechanism during repetitive firing in the axons, by increasing the relative refractoriness, or even by contributing to spike repolarization. Interestingly, the mossy fibres show dense immunostaining for KCNQ2 subunits (Cooper et al. 2001).

The function of IM in neuronal excitability control has prompted pharmaceutical interest in drugs that modulate M-channels (Gribkoff, 2003). The so-called ‘cognitive enhancers’ linopirdine and XE991 (Lamas et al. 1997; Zaczek et al. 1998) have been shown to block IM, whereas the anticonvulsant drug retigabine, now in clinical phase III trials, has been found to increase IM (Wickenden et al. 2000; Main et al. 2000). In animal models of epilepsy, retigabine showed a broad spectrum of anticonvulsant activity (Dailey et al. 1995; Tober et al. 1996; Rostock et al. 1996).

Interestingly, we found that retigabine increased synaptic transmission by increasing recovery from Na+ inactivation during elevated [K+]o. So why is retigabine an anticonvulsant, although it enhances synaptic transmission under conditions resembling seizure-like rises in [K+]o? (1) One possibility is that the net anticonvulsant effect of retigabine is due to its reduction of somatic excitability (see Fig. 7; and Yue & Yaari 2004; Gu et al. 2005). (2) Another interesting possibility is that activation of axonal IM by retigabine probably raises the threshold for action potentials generation at ectopic sites along the axon (Pinault, 1995). That retigabine may thus elevate the axonal spike threshold, is also supported by the analgesic effect of retigabine, which presumably is mediated via its effect on M-channel-containing nociceptive pathways (Passmore et al. 2003). (3) It is possible that retigabine, which has been suggested to have several sites and mechanisms of action, reduces convulsions by an M-channel-independent mechanism. Besides activating M-channels, higher concentrations of retigabine have been shown to potentiate GABAergic synaptic transmission and to block Na+ and Ca2+ channels (Rundfeldt & Netzer, 2000). (4) Finally, IM has also been found in inhibitory interneurons of the hippocampus [Storm JF et al. Soc. Neurosci Abstr 2003 (258.7)]. Therefore, it is difficult to predict the net effect of IM modulation at the circuit level.

IM is the target of numerous modulatory pathways. Reciprocal regulation of M-channels by activators such as somatostatin (Moore et al. 1988), and by M-channel suppressors such as metabotropic glutamate (Charpak et al. 1990), muscarinic (Brown & Adams, 1980) and opoid (Moore et al. 1994) receptors, could exert a powerful modulation of somatic and presynaptic excitability. Presynaptic actions of all these receptor types have been described in the hippocampus, but future studies are needed to determine which subtypes are located in axons, and which of these are coupled to presynaptic M-channels.

Contrasting effects of somatic versus axonal M-channels in CA3 pyramidal neurons

Although somatic and axonal/presynaptic K+ currents are often assumed to play similar functional roles (Byrne & Kandel, 1996), we observed apparent differences in the functions of M-current between the soma and axons (Schaffer collaterals) of CA3 pyramidal cells. While IM blockers and openers had no measurable effect on axonal responses or refractoriness under basal conditions, IM blockade clearly enhanced the somatic ADPs and bursting. Although ADPs and bursting may have been enhanced by holding the soma depolarized at −60 mV before testing (Fig. 7), similar effects of IM blockers have also been observed at more negative potentials (∼−70 mV) in CA1 hippocampal pyramidal cells (Yue & Yaari, 2004). Thus, it seems that the axonal/presynaptic M-current has less impact than its somatic counterpart, under basal conditions. Only under depolarizing conditions, e.g. in high [K+]o, or when the action potential is broadened by blocking other Kv channels, did the presynaptic M-channels show an appreciable effect. This difference resembles the difference seen in the somatic versus presynaptic functions of BK channels in hippocampal pyramidal cells (Hu et al. 2001). Also, the presynaptic BK channels appeared to be functionally silent under basal conditions, but were brought into action when the action potential was broadened. Thus, in both cases may the difference between axonal versus somatic functions of these channels be explained if the action potentials are narrower in the axons than in the soma, so that neither M- nor BK-channels are substantially activated by the normal axonal spike. As discussed above, several lines of evidence suggest that the spike is in fact briefer in axons than in the somata of these cells. Our results indicate that steady depolarization provides an additional way of engaging the presynaptic M-channels.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Lyle Graham for the ongoing development of the Surf-Hippo simulator, and modelling support. Thanks to Johan Hake for helpful discussions concerning field potential modelling. We also thank the anonymous reviewers for their useful comments on previous versions of this manuscript. This study was supported by the Norwegian Research council (NFR) via the FUGE, STORFORSK and Norwegian Centre of Excellence programs, and by the University of Oslo. Author contributions: J.F.S. and K.V. designed the experiments; K.V. performed and analysed the experiments and performed the numerical simulations for Figs 1, 2, 4–8, and S1–S3; H.H. and N.G. performed and analysed the experiments for Fig. 3; N.G. performed and analysed whole-cell recordings of EPSPs in Cs+-loaded neurons in standard [K+]o (see above, data not shown), and experiments in Fig. S3A, and assisted in experiments of Fig. 7; C.A. performed and analysed some of the experiments of Fig. 1 and performed and analysed pilot experiments. The manuscript was written by K.V. and J.F.S.

Supplemental material

The online version of this paper can be accessed at:

DOI: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.111336

http://jp.physoc.org/cgi/content/full/jphysiol.2006.111336/DC1 and contains supplemental material consisting of two files; one listing the model parameters and another containing three figures as follows:

XE991 did not affect field post-synaptic responses in stratum radiatum in standard [K+]o (2.5 mm)

In the model, the effects of IM on the FV and spike-evoked ICa in elevated [K+]o (11.5 mm) are robust for a wide range of IM, INa and ICa model parameter values

Modulation of IM during somatic recordings in CA3 pyramidal neurons did not affect the membrane potential and spike parameters in 11.5 mm [K+]o: Comparison between experiments and modelling.

This material can also be found as part of the full-text HTML version available from http://www.blackwell-synergy.com

References

- Alle H, Geiger JR. Combined analog and action potential coding in hippocampal mossy fibers. Science. 2006;311:1290–1293. doi: 10.1126/science.1119055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen C, Stevens CF. An evaluation of causes for unreliability of synaptic transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:10380–10383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.22.10380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral DG, Witter MP. The three-dimensional organization of the hippocampal formation: a review of anatomical data. Neuroscience. 1989;31:571–591. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(89)90424-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amiry-Moghaddam M, Williamson A, Palomba M, Eid T, de Lanerolle NC, Nagelhus EA, Adams ME, Froehner SC, Agre P, Ottersen OP. Delayed K+ clearance associated with aquaporin-4 mislocalization: phenotypic defects in brains of alpha-syntrophin-null mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13615–13620. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336064100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen P, Silfvenius H, Sundberg SH, Sveen O, Wigstrom H. Functional characteristics of unmyelinated fibres in the hippocampal cortex. Brain Res. 1978;144:11–18. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90431-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen M, Lambert JD. Regenerative properties of pyramidal cell dendrites in area CA1 of the rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 1995;483:421–441. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awatramani GB, Price GD, Trussell LO. Modulation of transmitter release by presynaptic resting potential and background calcium levels. Neuron. 2005;48:109–121. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischofberger J, Geiger JR, Jonas P. Timing and efficacy of Ca2+ channel activation in hippocampal mossy fiber boutons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10593–10602. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10593.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DA, Adams PR. Muscarinic suppression of a novel voltage-sensitive K+ current in a vertebrate neurone. Nature. 1980;283:673–676. doi: 10.1038/283673a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun VH, Otnass MK, Molden S, Steffenach HA, Witter MP, Moser MB, Moser EI. Place cells and place recognition maintained by direct entorhinal–hippocampal circuitry. Science. 2002;296:2243–2246. doi: 10.1126/science.1071089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne JH, Kandel ER. Presynaptic facilitation revisited: state and time dependence. J Neurosci. 1996;16:425–435. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-00425.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattaert D, El MA. Shunting versus inactivation: analysis of presynaptic inhibitory mechanisms in primary afferents of the crayfish. J Neurosci. 1999;19:6079–6089. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-06079.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlier C, Singh NA, Ryan SG, Lewis TB, Reus BE, Leach RJ, Leppert M. A pore mutation in a novel KQT-like potassium channel gene in an idiopathic epilepsy family. Nat Genet. 1998;18:53–55. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charpak S, Gahwiler BH, Do KQ, Knopfel T. Potassium conductances in hippocampal neurons blocked by excitatory amino-acid transmitters. Nature. 1990;347:765–767. doi: 10.1038/347765a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Johnston D. Properties of single voltage-dependent K+ channels in dendrites of CA1 pyramidal neurones of rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 2004;559:187–203. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.068114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]