Abstract

N-type CaV2.2 calcium channels localize to presynaptic nerve terminals of nociceptors where they control neurotransmitter release. Nociceptive neurons express a unique set of ion channels and receptors important for optimizing their role in transmission of noxious stimuli. Included among these is a structurally and functionally distinct N-type calcium channel splice isoform, CaV2.2e[37a], expressed in a subset of nociceptors and with limited expression in other parts of the nervous system. CaV2.2[e37a] arises from the mutually exclusive replacement of e37a for e37b in the C-terminus of CaV2.2 mRNA. N-type current densities in nociceptors that express a combination of CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b] mRNAs are significantly larger compared to cells that express only CaV2.2e[37b]. Here we show that e37a supports increased expression of functional N-type channels and an increase in channel open time as compared to CaV2.2 channels that contain e37b. To understand how e37a affects N-type currents we compared macroscopic and single-channel ionic currents as well as gating currents in tsA201 cells expressing CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b]. When activated, CaV2.2e[37a] channels remain open for longer and are expressed at higher density than CaV2.2e[37b] channels. These unique features of the CaV2.2e[37a] isoform combine to augment substantially the amount of calcium that enters cells in response to action potentials. Our studies of the e37a/e37b splice site reveal a multifunctional domain in the C-terminus of CaV2.2 that regulates the overall activity of N-type calcium channels in nociceptors.

N-type calcium channels are essential for the transmission of nociceptive information. These channels localize to presynaptic nerve terminals of small diameter myelinated and unmyelinated nociceptors that synapse in laminae I and II of the dorsal horn where they control neurotransmitter release (Holz et al. 1988; Maggi et al. 1990). Deletion of CaV2.2, the main subunit of the N-type channel complex, in mice causes higher pain thresholds than in wild-type mice (Hatakeyama et al. 2001; Kim et al. 2001; Saegusa et al. 2001; Saegusa et al. 2002) and selective inhibitors of N-type calcium channels, notably ziconotide, exhibit potent analgesic effects when administered spinally (Chaplan et al. 1994; Bowersox et al. 1996; Brose et al. 1997; Cox, 2000; Miljanich, 2004). N-type calcium channels are thus important drug targets in the treatment of chronic pain (Miljanich & Ramachandran, 1995; Vanegas & Schaible, 2000; Ino et al. 2001; Altier & Zamponi, 2004; Miljanich, 2004; Lipscombe & Raingo, 2006).

Recently, we reported that sensory neurons express a functionally distinct N-type calcium channel isoform not identified previously (Bell et al. 2004). This isoform, CaV2.2e[37a], contains a unique sequence in its C-terminus that originates from cell-specific inclusion of e37a, which is one of a pair of mutually exclusive exons, e37a and e37b (Fig. 1A–C). Our analyses showed that all neurons express CaV2.2e[37b] but that a subset of nociceptive neurons also express CaV2.2e[37a]. Using RT-PCR, we found little or no amplification of CaV2.2e[37a] in other parts of the nervous system (Bell et al. 2004).

Figure 1. CaV2.2 contains mutually exclusive exons 37a and 37b.

A, exons 37a and 37b are located adjacent to IVS6 at the proximal end of the CaV2.2 C-terminus. B, CaV2.2 mRNA contains either e37a or e37b. C, exons 37a and e37b differ by 14 amino acids. D, CaV2.2e[37a] mRNA is expressed in adult dorsal root ganglia (DRG) and adult brain. In DRG, CaV2.2e[37a] transcripts represent 5.9 ± 0.2% (DRG from eight animals) of all CaV2.2 mRNA, and in brain, CaV2.2e[37a] transcripts represent 1.8 ± 0.2% (brains from three animals) of all CaV2.2 mRNA. The mean percentages of e37a represent data from three individual hybridizations. The means are significantly different (P < 0.05).

The mammalian nervous system utilizes alternative splicing extensively to modify the activity of neuronal proteins for optimal function in specific cell types (Dredge et al. 2001; Lipscombe, 2005). Alternative splicing in the C-terminus of CaV channels controls the activity and targeting of voltage-gated calcium channels (Soldatov et al. 1997; Maximov et al. 1999; Krovetz et al. 2000; Soong et al. 2002; Chaudhuri et al. 2004; Kanumilli et al. 2006). We demonstrated that cell-specific splicing of CaV2.2 e37a and e37b modulates N-type current amplitude. N-type currents in sensory neurons expressing CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b] isoforms are significantly larger when compared to neurons that only express CaV2.2e[37b] (Bell et al. 2004). Larger currents in cells expressing both CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b] are not explained by differences in total mRNA, but attributed to sequences encoded by e37a.

In this report, we analyse whole-cell, single-channel and gating currents in mammalian tsA201 cells expressing either isoform to determine which differences between Ca2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b] channels regulate current density. Our previous analyses showed that CaV2.2e[37a] currents are significantly larger and that they also activate at voltages slightly more hyperpolarized than CaV2.2e[37b] currents when expressed in Xenopus oocytes. These data pointed to differences in gating as well as overall channel density between isoforms (Bell et al. 2004). We now show that CaV2.2e[37a] channels remain open for longer on average, and that the density of functional channels is significantly higher, as compared to CaV2.2e[37b] channels. We also show that these functional differences between isoforms significantly affect calcium entry evoked by action potentials recorded from nociceptors. Alternative splicing events under such cell-specific control probably evolved to contribute functional advantage to the cells in which they occur (Lipscombe, 2005). Our analyses of e37a/e37b splicing uncover new cellular mechanisms that regulate CaV2.2 channel activity in nociceptors.

Methods

Clones and transfection methods

All clones used in this study were constructed in our laboratory: CaV2.2e[37a] (AY211500) (Bell et al. 2004), CaV2.2e[37b] (AF055477) (Lin et al. 1997), CaVβ3 (sequence identical to M88751) and CaVα2δ1 (AF286488) (Lin et al. 2004). CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b] contain exons 37a and 37b, respectively, and encode proteins that differ by only 14 amino acids (Fig. 1A–C). We utilized Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) to transfect tsA201 cells (large T-antigen transformed HEK 293 cells) with a DNA mixture containing CaV2.2, CaVβ3 and CaVα2δ1 in a 1: 1: 1 molar ratio together with 10% enhanced green fluorescent protein (w/w). tsA201 cells were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2 in 90% Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). We carefully minimized variation in expression by selecting cells at 70% confluence for transfection, controlling cDNA concentrations, and harvesting all cells on the day of recording (24 h after transfection) and maintaining them in DMEM at 4°C until needed.

RNase protection assay and analysis

We utilized the RPA III protocol (Ambion) and the Bright Star Biodetect procedure (Ambion) essentially as described in the product manuals. The e37a probe was generated by RT-PCR from dorsal root ganglia (DRG) mRNA and cloned into vector pCRII (Invitrogen) for in vitro transcription using the Maxiscript kit (Ambion). PCR primers were: r1B37aup, 5′TTGCCGGATTCATTATAAGGATATGT; and r1B41dw, 5′TTGTCGAAGGAAAACCCGAGCT. Following RNase digestion, the probe generated fully protected and partially protected bands of 520 bp and 429 bp, respectively. Control hybridizations using increasing amounts of template RNA ensured all probes were present in excess with respect to target mRNAs in DRG and brain. To resolve fully protected e37a signal, 7 μg total RNA was required. We measured e37a RNA as a percentage of total CaV2.2 RNA. First, a series of timed exposures to Hyperfilm (Amersham) were collected. Next, films were scanned as 8-bit, minimum 96-dpi, TIFF images, and band volumes quantified with ImageQuant software (Amersham). Background was determined for each lane: the volume of a box located above the signal of interest was subtracted from the volume of an identical sized box around the signal of interest. We extrapolated partially protected probe volume at the same time point used to measure fully protected probe volume.

Whole-cell recording and analysis

Whole-cell, voltage-clamp recordings were performed using an Axopatch 200A amplifier and pCLAMP 8 software (Molecular Devices). All whole-cell recording protocols were carried out in identical ionic conditions. The internal solution contained (mm): CsCl 126, MgCl2 4, MgATP 4, Hepes 10, EDTA 1 and EGTA 10; pH was adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH. The bath solution contained (mm): choline chloride 135, MgCl2 4, Hepes 10 and CaCl2 1; pH was adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH. Fire polished electrodes had resistances of 2–3 MΩ when filled with internal solution. Low extracellular calcium was used to minimize current amplitude and thus optimize voltage control (see also Thaler et al. 2004). We also found no correlation between current amplitude and mid-point values of activation curves (V½) values of activation curves, indicating adequate voltage control. Electrodes were Sylgard-coated (Dow Corning). Series resistances were less than 6 MΩ and compensated 70–80%, with 10 μs lag time. Cells were held at −100 mV and stepped to various test potentials with currents sampled at 20 kHz. Tail currents were measured at −60 mV and sampled at 100 kHz. Gating currents were resolved by stepping the membrane potential to the ionic reversal potential, which was determined for each cell at the start of recording (Lin et al. 2004). All whole-cell data were low-pass filtered on-line at 10 kHz and leak subtracted online.

Action potential waveforms

Dr Bruce P. Bean, Nathaniel Blair, Jorg Mitterdorfer, and Michelino Puoplo kindly provided all action potential recordings used as command voltages. Four command voltages used in Fig. 9 were recorded from four different small diameter, nociceptive neurons of DRG (Blair & Bean, 2003). These action potentials have prominent plateaux characteristic of nociceptors. We used three single action potentials recorded from three different neurons with slightly different resting membrane potentials (Fig. 9A–C) and a train of action potentials (Fig. 9D) induced by exposure to 500 nm capsaicin (same voltage trace shown in Figure 1 of Blair & Bean, 2003). In addition, two representative action potential recordings were obtained from central neurons (Fig. 10A–B): spontaneous action potentials recorded from a dopaminergic neuron of the substantia nigra, and an action potential from a CA1 hippocampal neuron induced by a brief current pulse.

Figure 9. CaV2.2e[37a] channels carry more current when activated by action potentials recorded from nociceptors.

Whole-cell calcium currents recorded from tsA201 cells activated by action potential waveforms as command voltages. A–C, upper panels, individual current traces obtained from six different tsA201 cells expressing CaV2.2e[37a] (e37a) or CaV2.2e[37b] (e37b) using action potentials triggered by brief current pulses recorded from three different neurons. The resting potential of each neuron used to record each action potential is indicated. D, left panel, individual current traces from cells expressing CaV2.2e[37a] (e37a) and CaV2.2e[37b] (e37b). Traces are offset on the x-axis so that they can be distinguished. The command voltage shown above current traces is a train of action potentials recorded from a nociceptor induced by exposure to 500 nm capsaicin. A–C, lower panels and D, right panel, comparison of average total charge transferred for each isoform, normalized by cell capacitance, for each data set. n values are indicated in parentheses. Mean values are significantly different (*P < 0.05).

Figure 10. CaV2.2e[37a] channels carry more current when activated by action potentials recorded from central neurons.

Whole-cell calcium currents recorded from tsA201 cells activated by action potential waveforms as command voltages. A and B, upper panels, individual current traces recorded from four different tsA201 cells expressing CaV2.2e[37a] (e37a) or CaV2.2e[37b] (e37b). Command voltages shown above current traces. A, a train of two spontaneous action potentials (1, 2) recorded from a dopaminergic substantia nigra neuron. Current traces are offset slightly on the x-axis so that they can be distinguished. B, a single action potential recorded from a CA1 hippocampal neuron induced by a brief current pulse. A and B, lower panels, average total charge transferred for each isoform, normalized by cell capacitance, are compared for each data set; n values are indicated in parentheses. Mean values are significantly different (*P < 0.05).

Single-channel recording and analysis

Cell-attached, patch-clamp recordings were performed at room temperature (approximately 21°C) using an Axopatch 200A amplifier and pCLAMP 8 software. The pipette solution contained 110 mm BaCl2 and 10 mm Hepes; pH was adjusted to 7.4. The bath contained (mm): potassium aspartate 140, glucose 10, Hepes 5 and EGTA 10; pH was adjusted to 7.4. Electrodes had resistances of 6–12 MΩ when filled with pipette solution and were Sylgard-coated. Currents were sampled at 10 kHz and low-pass filtered on-line at 2 kHz. Leak subtraction was performed off-line using averaged null sweeps (30%–50% of all sweeps) taken at the same voltage. We used pCLAMP 9 software to classify and analyse single-channel events. To calculate single-channel conductance, we manually measured single-channel current amplitudes from 3 to 10 openings of durations sufficiently long to reach full amplitude (at least 0.6 μs). To calculate open dwell times we used a 50% threshold crossing to detect open and closed transitions. Events longer than 0.2 μs were included in the analysis. We set this as our minimum time resolution based on the signal to noise ratio. We set the ratio of the threshold crossing amplitude to the background root mean square noise at > 5 to reduce the probability of false event detection (Colquhoun & Sigworth, 1983). The maximum likelihood method was used to fit one or the sum of multiple exponential functions. Although our primary interest was in comparing single-channel current amplitudes and channel mean open times of the CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b] splice isoforms, we nonetheless restricted our kinetic analyses to patches without (or with a very low percentage of) simultaneous overlapping openings and only analysed sweeps that completely lacked simultaneous openings. These criteria eliminated from kinetic analysis < 10% of the total number of sweeps in any given patch. This was important to avoid underestimating the mean open time as simultaneous openings are more likely to occur during longer open times. All patches included in our analyses contained between 3 500 and 12 000 openings.

Statistical treatment of data

All data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. Student's paired t tests were used to determine statistical significance at the P < 0.05 level.

Results

Exon 37a is expressed in brain

We previously showed (Bell et al. 2004) that DRG express CaV2.2e[37a] mRNAs. Based on these analyses, we found little evidence for expression of this isoform in other parts of the nervous system (Bell et al. 2004). However, our experiments used non-quantitative RT-PCR amplification to assess the relative abundance of this isoform. Here we utilized ribonuclease protection to quantify CaV2.2e[37a] mRNA levels in adult DRG and adult brain. Our representative images show fully protected and partially protected e37a-containing probes hybridized to RNA from both tissue sources (Fig. 1D). CaV2.2e[37a] mRNAs are present in brain at measurable levels; however, we found that CaV2.2e[37a] levels are ∼3-fold higher in DRG than in brain. In DRG, CaV2.2e[37a] transcripts represent ∼6% of all CaV2.2 RNA, compared to ∼2% in brain. Based on our previous analyses, ∼35% of neurons in DRG express e37a and of these ∼75% are small diameter nociceptors (Bell et al. 2004).

Different size currents in tsA201 cells

We compared calcium currents recorded from tsA201 cells transiently expressing CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b] along with CaVβ3 and CaVα2δ1 subunits. Average current densities (pA pF−1) were consistently and significantly larger in cells expressing CaV2.2e[37a] than in cells expressing CaV2.2e[37b] (Fig. 2A and B). These data confirm and extend our previous analyses using the Xenopus oocyte expression system. Peak inward CaV2.2e[37a] current densities were 2.8- to 1.3-fold greater than those of CaV2.2e[37b], depending on test potential (Fig. 2C). Our data strongly implicate sequences encoded by e37a and e37b in regulating macroscopic N-type current amplitude. Further, our collective results show that the presence of e37a is necessary and sufficient to support larger whole cell N-type currents in three different cell types: neurons (Bell et al. 2004), Xenopus oocytes (Bell et al. 2004) and mammalian tsA201 cells (Fig. 2) This suggests that alternative splicing influences a mechanism common to three different cell types.

Figure 2. Exon 37a increases CaV2.2 current density.

A, CaV2.2e[37a] whole-cell currents evoked by steps from −40 to +110 mV from a holding potential of −100 mV (left). Representative inward currents at +10 mV (centre) and outward currents at +100 mV (right) of CaV2.2e[37a] (•) and CaV2.2e[37b] (○). B, Whole-cell current–voltage relationships of CaV2.2e[37a] (•, n = 20) and CaV2.2e[37b] (○, n = 21). Peak inward current densities are −217.1 ± 26.5 pA pF−1 at +10 mV for CaV2.2e[37a] and −129.1 ± 13.3 pA pF−1 at +15 mV for CaV2.2e[37b]. Significant differences (P < 0.05) exist between the current density values of each isoform from −20 to +50 mV and from +90 to +110 mV. Curves between −60 and +60 mV are fitted with a Boltzmann–Goldman–Hodgkin–Katz function. Curves between +60 and +110 mV are fitted with a single exponential. The estimated activation mid-point values (V½) for each isoform are significantly different (P < 0.05). The estimated slope factor (k) values and reversal potentials for each isoform are not significantly different. V½ values are 0.2 ± 0.4 mV and 4.1 ± 0.5 mV, k values are 4.9 ± 0.1 mV and 5.3 ± 0.2 mV, and reversal potentials are 59.9 ± 0.6 mV and 59.5 ± 1.0 mV for CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b], respectively. C, ratio of mean e37a and e37b peak current densities from B plotting a ratio value for all test potentials with a difference between mean current densities. The dotted line indicates a ratio of one.

We compared CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b] current densities over a wide range of test potentials in the tsA201 expression system. We also measured tail currents. Average peak inward and outward currents were significantly larger in cells expressing CaV2.2e[37a] than in those expressing CaV2.2e[37b] at all voltages where significant current was resolved. However, the difference in current densities between isoforms was greatest at more negative voltages: 2.5-fold at 0 mV compared to 1.3-fold at +100 mV (Fig. 2C). Our previous data suggested that two factors contributed to the larger current density in cells expressing CaV2.2e[37a] channels than in those expressing CaV2.2e[37b] channels: greater channel density and channel activation at slightly more hyperpolarized voltages (Bell et al. 2004).

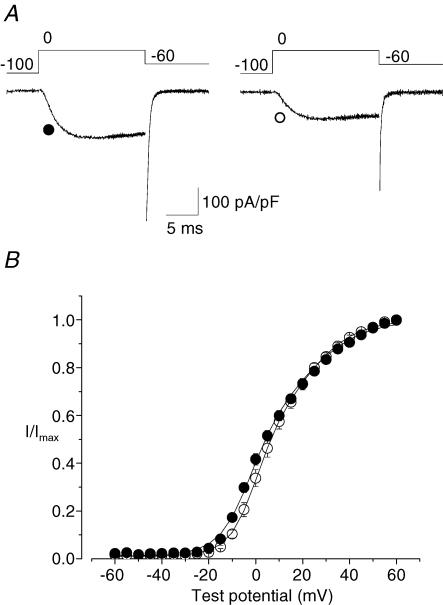

We analysed activation curves generated from tail currents and confirmed that CaV2.2e[37a] channels activated at voltages that were slightly but significantly more hyperpolarized as compared to CaV2.2e[37b] channels (Fig. 3). CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b] activation curves deviated significantly at test voltages that corresponded to the largest difference in current densities (cf. Figs 2C and 3). This shift in activation suggests that CaV2.2e[37a] channels have a greater channel open probability at negative voltages. At positive voltages where the difference in current density between isoforms is the smallest, channel open probabilities converge and approach maximum (Fig. 3). For the N-type channel, maximum channel open probability is close to 0.9 (Lee & Elmslie, 1999).

Figure 3. CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b] channels activate at similar voltages.

A, representative whole-cell currents from a cell expressing CaV2.2e[37a] channels and a cell expressing CaV2.2e[37b] channels. Tail currents were measured at −60 mV following a depolarizing test pulse to 0 mV. B, activation curves required the sum of two Boltzmann functions that had V½ values of ∼0 and ∼20 mV (Lin et al. 2004). An insufficient number of data points, however, define the second Boltzmann function making it difficult to obtain accurate estimates of the first Boltzmann in an unconstrained fit of the data. Fits shown were therefore obtained by constraining parameters of the second Boltzmann function for each individual data set. Parameters of the second Boltzmann function represented the overall average amplitude of 0.5, with V½ = 20 mV and k = 12 mV. Average values for parameters of the first Boltzmann obtained from the best fit to the data were for CaV2.2e[37a] (•, n = 13), V½ = – 3.3 ± 1.0 mV and k = 5.6 ± 0.5 mV, and for CaV2.2e[37b] (○, n = 10), V½ = 1.3± 1.7 mV and k = 5.5 ± 0.6 mV. V½ values are significantly different (P < 0.05), k values are not significantly different (P > 0.05).

Average open times differ between CaV2.2 isoforms

Our analyses suggest that CaV2.2e[37a] channels might remain open for longer than CaV2.2e[37b] channels (Fig. 3). We tested this hypothesis by two independent measures. First, we compared deactivation kinetics of whole-cell tail currents from CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b] channels. If assessed at voltages subthreshold for channel activation, the deactivation time constant is a measure of average single-channel activation duration. We compared deactivation kinetics of CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b] currents at −60 mV and found that CaV2.2e[37a] currents deactivated ∼1.5-fold more slowly than CaV2.2e[37b] currents (P < 0.05; Fig. 4A), suggesting that CaV2.2e[37a] channels remain open for longer on average than CaV2.2e[37b] channels.

Figure 4. CaV2.2e[37a] channels take longer to deactivate and are slower to inactivate.

A, left panel, tail currents from the cells shown in Fig. 3A normalized to peak tail current, and overlaid starting from the time of peak tail current. Tail current decays are fitted best with a single exponential. Right panel, time constants of deactivation (τdeact) are significantly different (P < 0.05) and are 0.40 ± 0.03 ms for CaV2.2e[37a] channels (•, n = 13) and 0.26 ± 0.05 ms for CaV2.2e[37b] channels (○, n = 9). Individual τdeact values are shown along with the mean value (larger circle). B, left panel, representative currents each normalized to peak current. Currents were generated by a square pulse depolarization to 0 mV from a holding potential of −100 mV. Inactivating currents are best fitted with a single exponential. Right panel, mean time constants of inactivation (τinact) values are significantly different (P < 0.05) and are 76.4 ± 11.0 ms for CaV2.2e[37a]-expressing cells (•, n = 5) and 41.2 ± 6 ms for CaV2.2e[37b]-expressing cells (○, n = 8). Individual τinact values are shown along with the mean value (larger circle).

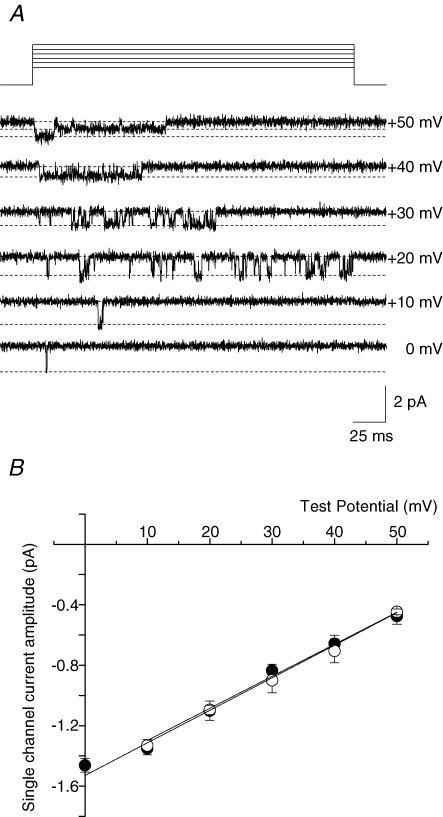

To confirm that CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b] channels have different open times, we analysed the activity of single-channel currents in cell-attached patches from cells expressing CaV2.2e[37a] and cells expressing CaV2.2e[37b] using 110 mm barium as the charge carrier. We first showed that single-channel currents had properties very similar to native N-type currents recorded previously in neurons (Elmslie, 1997) and CaV2.2 channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes with CaVβ1b and CaVα2δ subunits (Wakamori et al. 1999). Single-channel conductances of CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b] isoforms were indistinguishable (∼21 pS, Fig. 5). This is consistent with fact that the isoforms differ only in their C-termini and that their pore sequences are identical (CaV2.2e[37a], AY211500; CaV2.2e[37b], AF055477).

Figure 5. CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b] channels do not differ in their single-channel conductance.

A, representative single-channel openings from a patch containing CaV2.2e[37a] channels. Channels were activated by steps to 0, +10, +20, +30, +40 and +50 mV from a holding potential of −80 mV. B, average single-channel current–voltage relationships. Single-channel conductance values were determined per patch by linear regression and are 21.6 ± 0.2 pS (•, n = 4) for CaV2.2e[37a] channels and 21.2 ± 1.6 pS (○, n = 3) for CaV2.2e[37b] channels.

We next analysed single-channel open-time distributions. A series of single N-type channel current traces are shown in Fig. 6. Currents were activated by step depolarizations to +20 mV. This test potential is equivalent to a voltage of approximately −20 mV in whole-cell recordings obtained with solutions containing 20-fold lower concentration of extracellular divalent cations (Elmslie et al. 1994; Xu & Lipscombe, 2001). The use of 110 mm barium increases single-channel current amplitudes facilitating their detection; however, there is an accompanying shift in the voltage-dependence of calcium channel activation to significantly more depolarized voltages caused by the greater surface charge screening effects of high levels of divalent cations (Frankenhaeuser & Hodgkin, 1957; Elmslie et al. 1994; Xu & Lipscombe, 2001). Channel open-time distributions were fitted well by single exponentials with time constants of 1.51 ± 0.09 ms for CaV2.2e[37a] channels (n = 7) and 1.12 ± 0.05 ms for CaV2.2e[37b] channels (n = 7) (Fig. 6). Time constants fitted to CaV2.2e[37a] channel open-time distributions and overall average CaV2.2e[37a] channel open times were ∼1.4-fold longer (P < 0.05) as compared to CaV2.2e[37b] channels. This is consistent with our analyses of whole-cell current deactivation kinetics.

Figure 6. CaV2.2e[37a] channels open for longer durations.

A, representative single-channel openings (10 contiguous sweeps) from a patch containing CaV2.2e[37a] channels. Channels were activated by a step to +20 mV from a holding potential of −100 mV. The lower panel shows the open-time distribution (1-ms bin) of all sweeps from the same individual patch as the representative openings. B, same as A but for an individual patch containing CaV2.2e[37b] channels. Open-time distributions are best fitted with one exponential. The time constants of open-time distribution (τopen) and the mean open times are significantly different (P < 0.05) between isoforms. τopen values are 1.51 ± 0.09 ms for CaV2.2e[37a] channels (•, n = 7) and 1.12 ± 0.05 ms for CaV2.2e[37b] channels (○, n = 7). Mean open times are 1.79 ± 0.12 ms for CaV2.2e[37a] channels and 1.26 ± 0.05 ms for CaV2.2e[37b] channels. Insets show histograms using the same X-axis (0–15 ms) but a different y-axis that only extends to 1000 events per 1-ms bin to illustrate the different open-time distributions between isoforms.

Difference in overall gating kinetics between isoforms was also evident by comparing inactivation time courses. We found that CaV2.2e[37a] channels inactivate with a significantly slower time course than CaV2.2e[37b] channels during relatively long depolarizing test pulses (Fig. 4B). Although not apparent with short test depolarizations (Fig. 3; see also Bell et al. 2004), the slower inactivation characteristic of macroscopic CaV2.2e[37a] currents seen with long depolarizations is consistent with this isoform remaining open for longer durations. At the macroscopic level, inactivation of the N-type current will be influenced by microscopic time constants of activation, deactivation and inactivation.

CaV2.2e[37a] channels express at higher density

The difference in gating kinetics between CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b] channels contributes to setting overall current density particularly at more hyperpolarized voltages, but this alone is insufficient to account for the larger current densities of CaV2.2e[37a] currents (Bell et al. 2004). We therefore compared gating currents between isoforms to test the hypothesis that CaV2.2e[37a]-expressing cells have more functional channels on their surface than those cells expressing CaV2.2e[37b]. Gating currents originate from the displacement of gating charges within the protein and total charge moved during the gating current therefore reflects the total number of functional channels on the cell surface (Bezanilla, 2000). Gating currents precede pore opening and, consequently, initiation of the ionic current. However, gating and ionic currents are not perfectly separated in time. To resolve gating current in the absence of ionic current, we measured currents generated by the isoforms at the ionic reversal potential where the net flow of ions through the pore is zero (Lin et al. 2004). We determined the ionic reversal potential for each cell and evoked gating current by a test pulse to the ionic reversal potential (Fig. 7A).This method allowed us to calculate the total gating charge transferred for each cell expressing CaV2.2 isoforms with recording solutions identical to those used to measure ionic currents (Fig. 2). We first showed that kinetics and voltage-dependence of gating currents measured from both isoforms were not significantly different (Fig. 7; P > 0.4). Gating current decay time constants were 0.502 ± 0.009 ms (n = 18) and 0.527 ± 0.011 ms (n = 16) and Boltzmann slope factors were 8.81 ± 0.80 mV (n = 18) and 8.47 ± 0.37 mV (n = 16) for CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b], respectively (Fig. 7). By contrast, alternative splicing in a different domain of CaV2.2, (ISVS3-IVS4) close to the domain IV voltage sensor, significantly modifies N-type channel gating current kinetics (Lin et al. 2004). Although the basic properties of gating currents did not differ between isoforms, the average gating charge in cells expressing CaV2.2e[37a] was significantly greater (22.5 ± 2.6 fC pF−1; n = 18) than that in cells expressing CaV2.2e[37b] (15.4 ± 1.5 fC pF−1; n = 16, Fig. 7B; P < 0.05). Notably, this ∼1.5-fold difference in the size of the gating charge between isoforms parallels the difference in N-type current densities measured at a similar voltage, close to the reversal potential (∼1.3-fold; Fig. 2C).

Figure 7. Cells expressing CaV2.2e[37a] channels displace more gating charge.

A, whole-cell currents from a cell expressing CaV2.2e[37a] showing the change in the ON gating currents at the reversal potential (+62.0 mV in this cell) following steps to various potentials (−100, −60, −10, +10 and +100 mV shown) from a holding potential of −100 mV. B, expanded ON gating currents at the reversal potential after a preceding step to −100 mV for a cell expressing CaV2.2e[37a] (•) and a cell expressing CaV2.2e[37b] (○). The decay of the gating current fitted with a single exponential and the time constant is the same for both isoforms (CaV2.2e[37a], 0.50 ± 0.01 ms, n = 18; CaV2.2e[37b], 0.53 ± 0.01 ms, n = 18). C, average total charge movement during ON gating current as a function of the preceding potential step for CaV2.2e[37a] (•, n = 18) and CaV2.2e[37b] (○, n = 18). The average charge moved is significantly different (P < 0.05) between the two isoforms from −100 to −60 mV. The curves are fitted with a Boltzmann function and the asymptotes at the hyperpolarized potentials are significantly different (P < 0.05): CaV2.2e[37a], 22.7 ± 1.0 fC pF−1; CaV2.2e[37b], 15.5 ± 0.6 fC pF−1. The other parameters from the individual fits are not significantly different. The asymptotes at depolarized potentials are 0.03 ± 0.09 fC pF−1 and −0.15 ± 0.08 fC pF−1, V½ values are −12.3 ± 2.4 mV and −7.4 ± 2.0 mV, and k values are 10.3 ± 1.3 mV and 8.0 ± 1.2 mV for CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b], respectively.

We measured the voltage dependence of gating currents by applying a series of step depolarizations preceding the test pulse to the ionic reversal (Fig. 7A). As the size of the preceding depolarization was increased, more channels open before the test pulse, moving more gating charge before the test pulse, and decreasing the size of the gating current measured at the ionic reversal potential (Fig. 7A). The fraction of gating charge remaining follows a Boltzmann function and can be used to estimate the voltage dependence of the gating current. Although the magnitude of the gating current differs significantly between isoforms, their voltage dependencies are indistinguishable (Fig. 7C). Our data are consistent with the hypothesis that alternative inclusion of e37a and e37b regulates the number of functional CaV2.2 channels expressed on the cell surface.

Maximal channel open probabilities are indistinguishable

We also compared maximal gating charge displaced (Qmax) with the whole-cell conductance (Gmax) for each cell, as described by Agler et al. (2005). This allowed us to compare channel open probabilities of isoforms at positive voltages where single-channel currents are difficult to resolve. Based on our comparison of isoform activation curves and studies of native N-type currents by others (Lee & Elmslie, 1999), we expected little difference in channel open probabilities between isoforms at strongly positive voltages because activation approached maximum (Fig. 3B). Gmax was determined from each cell as the slope of the peak current-voltage relationship (between +20 and +60 mV, Fig 2B). Gmax is related to single channel open probability at maximal depolarization by the following equation:

where POmax is the single-channel open probability at maximal depolarization, n is the number of channels and γ is the single-channel conductance. Qmax can be determined according to the following equation:

where qmax is the maximum gating charge moved per single channel. Plotting Gmax as a function of Qmax defines a linear relationship with a slope Gmax/Qmax = POmax (γ/qmax) (Fig. 8). We have shown that splicing of e37a and e37b does not alter single-channel conductance (Fig. 5). We can also assume that the number of elementary charges moved by CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b] channels are the same because the kinetics and voltage dependencies of their gating currents are indistinguishable (Fig. 7B and C), as expected for channels whose core sequences are identical. In this case, Gmax/Qmax is proportional to POmax.

Figure 8. The relationship between whole-cell conductance and gating charge moved is identical.

Gmaxversus Qmax relationship for CaV2.2e[37a] (•, n = 17) and CaV2.2e[37b] (○, n = 16). The data from each isoform were fitted by linear regression. The slopes and the y-axis intercepts are not significantly different between the two isoforms. The slopes (Gmax/Qmax) are 0.20 ± 0.02 nS fC−1 and 0.20 ± 0.03 nS fC−1, the y-axis intercepts are 6.37 ± 4.23 nS and 5.17 ± 5.50 nS, and r2 values are 0.89 and 0.80 for CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b], respectively.

The scatter plot of Gmax against Qmax calculated from individual cells expressing CaV2.2e[37a] or CaV2.2e[37b] shows that POmax is indistinguishable between splice isoforms at these positive voltages (Fig. 8). Even though the whole-cell conductance in cells expressing CaV2.2e[37a] is higher on average than in cells expressing CaV2.2e[37b], their gating currents are also proportionately larger.

Greater calcium entry induced by action potential waveforms in cells expressing CaV2.2e[37a]

Our data support the hypothesis that e37a increases the number of functional N-type calcium channels expressed on the cell surface as compared to e37b, and that e37a also influences channel open probability particularly at test potentials during the initial and steep phases of the activation curve. An important prediction from our studies is that CaV2.2e[37a] channels will support more calcium entry in response to physiologically relevant stimuli, including action potentials. We do not have tools such as isoform-specific toxins to test this hypothesis directly in neurons; however, we can measure the relative efficacy of CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b] channels to support calcium entry in response to action potential waveforms using the tsA201 expression system (Scroggs & Fox, 1992; Park & Dunlap, 1998; Blair & Bean, 2003; Thaler et al. 2004). Of particular relevance are action potentials recorded from nociceptors that express a combination of CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b] isoforms. Single DRG action potentials evoked by brief current injections and a train of action potential evoked by exposure to 500 nm capsaicin were provided by Bruce P. Bean and colleagues (Blair & Bean, 2003) and used as command voltages to induce currents in cells expressing the two isoforms. These action potentials had characteristic plateaux or shoulders typical of small diameter nociceptors (Scroggs & Fox, 1992; Park & Dunlap, 1998). We integrated total current evoked by individual action potentials (Figs 9A–C and 10A and B) as well as a train of action potentials induced by exposure to 500 nm capsaicin (Fig. 9D). In all cases, the averaged total integrated calcium current was significantly larger in cells expressing CaV2.2e[37a] channels than in cells expressing CaV2.2e[37b] channels. In Fig. 9, we show examples of current traces and averaged data from experiments using action potential recordings obtained from four different nociceptors of DRG (Fig. 9A–D). In Fig. 10 we show similar recordings using spontaneous action potentials obtained from a dopaminergic neuron of the substantia nigra (Fig. 10A) and an evoked action potential from a CA1 hippocampal neuron (Fig. 10B). Collectively, these experiments support the hypothesis that CaV2.2e[37a] channels are more efficient than CaV2.2e[37b] channels in coupling action potential depolarization to calcium entry.

Discussion

We showed previously that the presence of CaV2.2e[37a] mRNAs in neurons correlates with larger N-type current densities, compared to current densities of neurons expressing exclusively CaV2.2e[37b]. Here we provide evidence that two mechanisms underlie the larger current phenotype of the CaV2.2e[37a] splice isoform. We found that CaV2.2e[37a] channels remain open for longer on average than CaV2.2e[37b] channels and that functional CaV2.2e[37a] channels are expressed at higher density on the cell surface than CaV2.2e[37b] channels. In the present study, we compared CaV2.2 isoforms expressed in mammalian tsA201 cells, but our collective data include heterologous expression studies in Xenopus oocytes and analysis of native N-type calcium currents in nociceptive neurons. In all cell types, CaV2.2e[37a] currents were larger than CaV2.2e[37b] currents implicating ubiquitous cellular mechanisms in e37a-dependent regulation of N-type channel current density. We also conclude that sequences unique to and encoded by e37a are sufficient to up-regulate N-type calcium channel activity.

Functional significance

We have shown that CaV2.2e[37a] represents only 6% of total CaV2.2 mRNA in whole DRG; however, the relative abundance of CaV2.2e[37a] must be substantially higher in individual nociceptive neurons. Two observations suggest that CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b] mRNAs are, on average, present at approximately equal abundance in nociceptors that express both. First, CaV2.2e[37a] was found in ∼35% of DRG neurons. Of these neurons, ∼75% were small diameter nociceptors that should contribute significantly less RNA to the total pool than large diameter neurons. Thus, CaV2.2e[37a] levels are at least ∼20% of total CaV2.2 RNA in individual neurons. This is probably closer to ∼40%, as large diameter neurons probably contribute ∼2-fold more RNA than nociceptors (based on a 1.5-fold difference in cell capacitance between these two populations; Bell et al. 2004). Second, we showed previously that peak N-type currents in nociceptors expressing both e37a and e37b isoforms were ∼1.5-fold larger than currents in nociceptors expressing CaV2.2e[37b] alone (Bell et al. 2004). When expressed separately as pure populations of channels, CaV2.2e[37a] supports N-type currents that are ∼2.5-fold larger at their peak (Fig. 2B). Considering differences between peak currents, we predict that CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b] mRNAs are equally abundant in nociceptive neurons. Our ribonuclease protection analyses also allowed us to measure CaV2.2e[37a] mRNA levels accurately in brain. Although present at low levels, CaV2.2e[37a] mRNA was detected in brain, implying that CaV2.2e[37a] isoforms might be restricted to specific subsets of neurons in the central nervous system. Additional tools, such as isoform-specific antibodies, would enable us to determine the expression pattern of these CaV2.2 isoforms.

The impact on N-type current density mediated by alternative splicing at the e37a/e37b locus is substantial, ranging from ∼2.5-fold larger currents in tsA201 cells expressing CaV2.2e[37a] compared to CaV2.2e[37b] at voltages between −10 and 0 mV to ∼1.3-fold larger currents at strongly positive voltages (Fig. 2C). Our studies of cloned channels are generally consistent with our previous analyses of native N-type currents in nociceptors that revealed a strong correlation between the expression of CaV2.2e[37a] mRNA and larger N-type current densities. However, by comparing the properties of CaV2.2 splice variants isolated from other calcium currents, we also find that CaV2.2e[37a] channels activate at voltages more hyperpolarized and remain open for longer than CaV2.2e[37b] channels. The following observations support this conclusion: (i) activation thresholds for CaV2.2e[37a] channels are more hyperpolarized in tsA201 cells (Fig. 3) and in Xenopus oocytes (Bell et al. 2004); (ii) CaV2.2e[37a] channels deactivate more slowly at −60 mV, consistent with longer open times (Fig. 4A); (iii) single CaV2.2e[37a] channels remain open for longer, on average, than CaV2.2e[37b] channels (Fig. 6); and (iv) macroscopic CaV2.2e[37a] currents inactivate more slowly in response to long duration test pulses (Fig. 4B). We did not observe differences in N-type channel gating between neurons expressing CaV2.2e[37b] alone and those expressing both isoforms (Bell et al. 2004). However, as discussed previously (Bell et al. 2004), small differences in activation thresholds of whole-cell currents in neurons may be masked by a combination of the toxin-subtraction method needed to isolate the N-type currents and the influence of other splice isoforms of CaV2.2 with their own distinct properties (see Lipscombe & Castiglioni, 2004). We also note the relatively high error associated with N-type current densities measured from nociceptors at more positive voltages (Figure 7 of Bell et al. 2004). These factors complicate quantitative comparisons between native currents and heterologously expressed cloned channels particularly at test voltages either side of peak current.

Nonetheless, all our analyses demonstrate that e37a increases N-type current density. N-type channels are targets of numerous signalling pathways, the vast majority of which inhibit N-type channel activity via G-protein activation (Ikeda & Dunlap, 1999); G-protein-dependent mechanisms attenuate N-type currents by at most ∼50% (Ikeda & Dunlap, 1999; Elmslie, 2003). Here, we describe a post-transcriptional mechanism for effecting long-term enhancement of overall N-type current activity and potentially enhancing transmitter release in select cells. Utilizing action potentials recorded from nociceptors, a central dopaminergic neuron and a CA1 hippocampal neuron as the stimulus, we confirm that significantly more calcium enters cells expressing CaV2.2e[37a] than those expressing CaV2.2e[37b]. The use of action potentials recorded from nociceptors with characteristic wide repolarization shoulders is especially relevant because CaV2.2e[37a] channels are enriched in nociceptors. High voltage-activated calcium currents, in turn, are a major component of the repolarization shoulder in action potentials of nociceptors (Blair & Bean, 2002). It would therefore be interesting to determine whether CaV2.2e[37a] isoforms also influence action potential width in nociceptors.

It will also be important to determine whether CaV2.2e[37a] channels are targeted to the nerve terminal. Our previous analyses of N-type currents in nociceptors were restricted to currents measured in cell bodies. The availability of CaV2.2 isoform-specific antibodies would greatly facilitate efforts to determine the subcellular distribution of CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b] channels.

Alternative splicing influences CaV2.2 channel density

Our data support the hypothesis that e37a facilitates surface expression of functional CaV2.2 channels to a greater extent than e37b. We demonstrated this by comparing gating currents in cells expressing CaV2.2e[37a] and CaV2.2e[37b] (Lin et al. 2004). We used identical recording solutions to measure both ionic currents and gating currents in the same cells (Lin et al. 2004; Agler et al. 2005; McDonough et al. 2005). This allowed direct comparisons between gating and ionic currents, though it is important to emphasize here that gating currents only provide information about functional channels and do not measure channel surface density directly. Whereas ours is the first report to demonstrate that alternative splicing controls expression levels of voltage-gated calcium channels, others have shown that this process regulates expression of postsynaptic receptors. A specific splice variant of synapse-associated protein-97 (SAP-97) targets AMPA receptors to cortical spines (Rumbaugh et al. 2003). In spinal cord, expression of a specific splice isoform of gephyrin, a glycine receptor–tubulin-bridging molecule, sets the level of glycine receptors at inhibitory synapses (Meier & Grantyn, 2004). Alternative splicing of the NMDA receptor modifies synaptic strength with changes in neuronal activity (Mu et al. 2003). Here, alternative splicing of the C2/C2′ domain of the NMDA receptor retains the receptor in the endoplasmic reticulum during periods of increased neuronal activity (C2 variants) and promotes its export from the endoplasmic reticulum (C2′ variants) when activity is inhibited. It would be interesting to know whether changes in neuronal activity in nociceptive neurons during either normal or disease states regulates splicing of e37a/e37b and subsequent expression of N-type channels. For example, there is evidence that N-type channel activity is up-regulated following peripheral nerve injury in animal models of chronic pain (Matthews & Dickenson, 2001).

The C-terminus of CaV2.2 modulates channel properties

Numerous physiologically important factors are known to influence calcium channel gating kinetics. These include protein binding, phosphorylation and alternative splicing and they involve several different regions of the CaVα1 subunit including the I–II and II–III loops, C-terminus and S3–S4 extracellular linkers (Lin et al. 1999; Lee & Elmslie, 2000; Colecraft et al. 2001; Lipscombe, 2004; Thaler et al. 2004). An analogous e37a/e37b splice site is present in the CaV2.1 gene suggesting that this region is an important control site for regulating voltage-gated calcium channel activity. It is interesting that the sequences encoded by these exons, their effects on channel function, and their expression patterns are distinct from CaV2.2 (Soong et al. 2002; Chaudhuri et al. 2004, 2005).

The biosynthetic pathways that direct ion channel targeting to and removal from the plasma membrane are also under tight cellular control (Ma & Jan, 2002). Specific amino acids in the C-terminus of CaV2.2 unique to e37a must regulate channel density either by increasing plasma membrane targeting efficiency or inhibiting channel internalization. Studies of CaV2.2 and other CaV channels implicate the II–III loop and C-terminus in channel targeting (Sakurai et al. 1996; Maximov & Bezprozvanny, 2002; Timmermann et al. 2002). Trafficking of CaVα1 to the plasma membrane is stimulated by CaVβ subunits that bind to the I–II intracellular loop and displace CaVα1 from the endoplasmic reticulum (Bichet et al. 2000). By contrast, the C-terminus has been implicated recently in G-protein-coupled receptor-dependent internalization of CaV2.2 channels in sensory neurons of DRG (Altier et al. 2006). Opioid receptor-like agonists as well as GABAB receptor agonists stimulate CaV2.2 channel removal from the cell surface via distinct mechanisms that both depend on G-protein activation (Altier et al. 2006; Tombler et al. 2006; Lipscombe & Raingo, 2006). These recent studies show that CaV2.2 channel internalization is tightly regulated in sensory neurons, raising the possibility that sequences in the C-terminus encoded by e37a might inhibit this process. Whatever cellular factors target this splice site in the C-terminus, they are likely to be part of the general cellular mechanism for controlling surface expression of CaV2.2 channels as e37a-containing channels generate larger N-type currents in three very different types of cells.

Conclusion

Cell-specific inclusion of e37a in the C-terminus of CaV2.2 channels represents a mechanism for long-term control of N-type calcium channel activity. The region of the C-terminus encoded by e37a/e37b is multifunctional, with synergistic effects on CaV2.2 gating kinetics and surface expression levels that combine to regulate the coupling between action potential stimuli and calcium entry. Although alternative splicing is a common feature of important neural genes, few studies have identified the functional consequences of this process in identified neuronal populations. Our studies emphasize the presence of e37a-containing CaV2.2 mRNA in a subpopulation of sensory neurons; however, we also see significant levels of CaV2.2e[37a] mRNA in brain. This raises the possibility that alternative splicing of e37a/e37b may regulate CaV2.2 channel activity similarly in other localized regions of the nervous system.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bruce P. Bean, Nathaniel Blair, Jorg Mitterclorer, and Michelilo Puoplo for sharing action potential recordings for our studies. This work was done in partial fulfilment of the requirement for a PhD degree from Brown University (A.J.C.). This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants NS29967 (D.L.) and GM07601 (A.J.C.).

References

- Agler HL, Evans J, Tay LH, Anderson MJ, Colecraft HM, Yue DT. G protein-gated inhibitory module of N-type (ca(v)2.2) ca2+ channels. Neuron. 2005;46:891–904. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altier C, Khosravani H, Evans RM, Hameed S, Peloquin JB, Vartian BA, et al. ORL1 receptor-mediated internalization of N-type calcium channels. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:31–40. doi: 10.1038/nn1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altier C, Zamponi GW. Targeting Ca2+ channels to treat pain: T-type versus N-type. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:465–470. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell TJ, Thaler C, Castiglioni AJ, Helton TD, Lipscombe D. Cell-specific alternative splicing increases calcium channel current density in the pain pathway. Neuron. 2004;41:127–138. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00801-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezanilla F. The voltage sensor in voltage-dependent ion channels. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:555–592. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.2.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bichet D, Cornet V, Geib S, Carlier E, Volsen S, Hoshi T, Mori Y, De Waard M. The I–II loop of the Ca2+ channel alpha1 subunit contains an endoplasmic reticulum retention signal antagonized by the beta subunit. Neuron. 2000;25:177–190. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80881-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair NT, Bean BP. Roles of tetrodotoxin (TTX)-sensitive Na+ current, TTX-resistant Na+ current, and Ca2+ current in the action potentials of nociceptive sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10277–10290. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10277.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair NT, Bean BP. Role of tetrodotoxin-resistant Na+ current slow inactivation in adaptation of action potential firing in small-diameter dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10338–10350. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-32-10338.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowersox SS, Gadbois T, Singh T, Pettus M, Wang YX, Luther RR. Selective N-type neuronal voltage-sensitive calcium channel blocker, SNX-111, produces spinal antinociception in rat models of acute, persistent and neuropathic pain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;279:1243–1249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brose WG, Gutlove DP, Luther RR, Bowersox SS, McGuire D. Use of intrathecal SNX-111, a novel, N-type, voltage-sensitive, calcium channel blocker, in the management of intractable brachial plexus avulsion pain. Clin J Pain. 1997;13:256–259. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199709000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplan SR, Pogrel JW, Yaksh TL. Role of voltage-dependent calcium channel subtypes in experimental tactile allodynia. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;269:1117–1123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri D, Alseikhan BA, Chang SY, Soong TW, Yue DT. Developmental activation of calmodulin-dependent facilitation of cerebellar P-type Ca2+ current. J Neurosci. 2005;25:8282–8294. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2253-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri D, Chang SY, DeMaria CD, Alvania RS, Soong TW, Yue DT. Alternative splicing as a molecular switch for Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent facilitation of P/Q-type Ca2+ channels. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6334–6342. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1712-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colecraft HM, Brody DL, Yue DT. G-protein inhibition of N- and P/Q-type calcium channels: distinctive elementary mechanisms and their functional impact. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1137–1147. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-04-01137.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun D, Sigworth F. Fitting and statistical analysis of single-channel records. In: Sakmann B, Neher E, editors. Single-Channel Recording. New York: Plenum Press; 1983. p. 191. chap 11. [Google Scholar]

- Cox B. Calcium channel blockers and pain therapy. Curr Rev Pain. 2000;4:488–498. doi: 10.1007/s11916-000-0073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dredge BK, Polydorides AD, Darnell RB. The splice of life: alternative splicing and neurological disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:43–50. doi: 10.1038/35049061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmslie KS. Identification of the single channels that underlie the N-type and L-type calcium currents in bullfrog sympathetic neurons. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2658–2668. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-08-02658.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmslie KS. Neurotransmitter modulation of neuronal calcium channels. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2003;35:477–489. doi: 10.1023/b:jobb.0000008021.55853.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmslie KS, Kammermeier PJ, Jones SW. Reevaluation of Ca2+ channel types and their modulation in bullfrog sympathetic neurons. Neuron. 1994;13:217–228. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90471-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankenhaeuser B, Hodgkin AL. The action of calcium on the electrical properties of squid axons. J Physiol. 1957;137:218–244. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1957.sp005808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatakeyama S, Wakamori M, Ino M, Miyamoto N, Takahashi E, Yoshinaga T, et al. Differential nociceptive responses in mice lacking the alpha1B subunit of N-type Ca2+ channels. Neuroreport. 2001;12:2423–2427. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200108080-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holz GGT, Dunlap K, Kream RM. Characterization of the electrically evoked release of substance P from dorsal root ganglion neurons: methods and dihydropyridine sensitivity. J Neurosci. 1988;8:463–471. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-02-00463.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda SR, Dunlap K. Voltage-dependent modulation of N-type calcium channels: role of G protein subunits. Adv Second Messenger Phosphoprotein Res. 1999;33:131–151. doi: 10.1016/s1040-7952(99)80008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ino M, Yoshinaga T, Wakamori M, Miyamoto N, Takahashi E, Sonoda J, et al. Functional disorders of the sympathetic nervous system in mice lacking the alpha 1B subunit (Cav 2.2) of N-type calcium channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:5323–5328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081089398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanumilli S, Tringham EW, Payne CE, Dupere JR, Venkateswarlu K, Usowicz MM. Alternative splicing generates a smaller assortment of CaV2.1 transcripts in cerebellar Purkinje cells than in the cerebellum. Physiol Genomics. 2006;24:86–96. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00149.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C, Jun K, Lee T, Kim SS, McEnery MW, Chin H, Kim HL, Park JM, Kim DK, Jung SJ, Kim J, Shin HS. Altered nociceptive response in mice deficient in the alpha(1B) subunit of the voltage-dependent calcium channel. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2001;18:235–245. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2001.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krovetz HS, Helton TD, Crews AL, Horne WA. C-terminal alternative splicing changes the gating properties of a human spinal cord calcium channel alpha 1A subunit. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7564–7570. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-20-07564.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HK, Elmslie KS. Gating of single N-type calcium channels recorded from bullfrog sympathetic neurons. J Gen Physiol. 1999;113:111–124. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HK, Elmslie KS. Reluctant gating of single N-type calcium channels during neurotransmitter-induced inhibition in bullfrog sympathetic neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3115–3128. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-09-03115.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, McDonough SI, Lipscombe D. Alternative splicing in the voltage-sensing region of N-type CaV2.2 channels modulates channel kinetics. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:2820–2830. doi: 10.1152/jn.00048.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z, Haus S, Edgerton J, Lipscombe D. Identification of functionally distinct isoforms of the N-type Ca2+ channel in rat sympathetic ganglia and brain. Neuron. 1997;18:153–166. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80054-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z, Lin Y, Schorge S, Pan JQ, Beierlein M, Lipscombe D. Alternative splicing of a short cassette exon in alpha1B generates functionally distinct N-type calcium channels in central and peripheral neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5322–5331. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-13-05322.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscombe D. Neuronal proteins custom designed by alternative splicing. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:358–363. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscombe D, Castiglioni AJ. Alternative splicing in voltage-gated calcium channels. In: McDonough SI, editor. Calcium Channel Pharmacology. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum, New York; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lipscombe D, Raingo J. Internalizing channels: a mechanism to control pain? Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:8–10. doi: 10.1038/nn0106-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D, Jan LY. ER transport signals and trafficking of potassium channels and receptors. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2002;12:287–292. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00319-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonough SI, Mori Y, Bean BP. FPL 64176 modification of Ca(V)1.2, L-type calcium channels: dissociation of effects on ionic current and gating current. Biophys J. 2005;88:211–223. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.051714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggi CA, Tramontana M, Cecconi R, Santicioli P. Neurochemical evidence for the involvement of N-type calcium channels in transmitter secretion from peripheral endings of sensory nerves in guinea pigs. Neurosci Lett. 1990;114:203–206. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90072-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews EA, Dickenson AH. Effects of spinally delivered N- and P-type voltage-dependent calcium channel antagonists on dorsal horn neuronal responses in a rat model of neuropathy. Pain. 2001;92:235–246. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(01)00255-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maximov A, Bezprozvanny I. Synaptic targeting of N-type calcium channels in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:6939–6952. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-16-06939.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maximov A, Sudhof TC, Bezprozvanny I. Association of neuronal calcium channels with modular adaptor proteins. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:24453–24456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.35.24453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier J, Grantyn R. A gephyrin-related mechanism restraining glycine receptor anchoring at GABAergic synapses. J Neurosci. 2004;24:1398–1405. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4260-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miljanich GP. Ziconotide: neuronal calcium channel blocker for treating severe chronic pain. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11:3029–3040. doi: 10.2174/0929867043363884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miljanich GP, Ramachandran J. Antagonists of neuronal calcium channels: structure, function, and therapeutic implications. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1995;35:707–734. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.35.040195.003423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu Y, Otsuka T, Horton AC, Scott DB, Ehlers MD. Activity-dependent mRNA splicing controls ER export and synaptic delivery of NMDA receptors. Neuron. 2003;40:581–594. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00676-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park D, Dunlap K. Dynamic regulation of calcium influx by G-proteins, action potential waveform, and neuronal firing frequency. J Neurosci. 1998;18:6757–6766. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-17-06757.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaugh G, Sia GM, Garner CC, Huganir RL. Synapse-associated protein-97 isoform-specific regulation of surface AMPA receptors and synaptic function in cultured neurons. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4567–4576. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-11-04567.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saegusa H, Kurihara T, Zong S, Kazuno A, Matsuda Y, Nonaka T, Han W, Toriyama H, Tanabe T. Suppression of inflammatory and neuropathic pain symptoms in mice lacking the N-type Ca2+ channel. EMBO J. 2001;20:2349–2356. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.10.2349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saegusa H, Matsuda Y, Tanabe T. Effects of ablation of N- and R-type Ca2+ channels on pain transmission. Neurosci Res. 2002;43:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(02)00017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Westenbroek RE, Rettig J, Hell J, Catterall WA. Biochemical properties and subcellular distribution of the BI and rbA isoforms of alpha 1A subunits of brain calcium channels. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:511–528. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.2.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scroggs RS, Fox AP. Multiple Ca2+ currents elicited by action potential waveforms in acutely isolated adult rat dorsal root ganglion neurons. J Neurosci. 1992;12:1789–1801. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-05-01789.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldatov NM, Zuhlke RD, Bouron A, Reuter H. Molecular structures involved in L-type calcium channel inactivation. Role of the carboxyl-terminal region encoded by exons 40–42 in alpha1C subunit in the kinetics and Ca2+ dependence of inactivation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3560–3566. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soong TW, DeMaria CD, Alvania RS, Zweifel LS, Liang MC, Mittman S, Agnew WS, Yue DT. Systematic identification of splice variants in human P/Q-type channel alpha1(2.1) subunits: implications for current density and Ca2+-dependent inactivation. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10142–10152. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10142.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaler C, Gray AC, Lipscombe D. Cumulative inactivation of N-type CaV2.2 calcium channels modified by alternative splicing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:5675–5679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0303402101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmermann DB, Westenbroek RE, Schousboe A, Catterall WA. Distribution of high-voltage-activated calcium channels in cultured gamma-aminobutyric acidergic neurons from mouse cerebral cortex. J Neurosci Res. 2002;67:48–61. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tombler E, Cabanilla NJ, Carman P, Permaul N, Hall JJ, Richman RW, Lee J, Rodriguez J, Felsenfeld DP, Hennigan RF, Diverse-Pierluissi MA. G protein-induced trafficking of voltage-dependent calcium channels. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1827–1839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508829200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanegas H, Schaible H. Effects of antagonists to high-threshold calcium channels upon spinal mechanisms of pain, hyperalgesia and allodynia. Pain. 2000;85:9–18. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00241-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakamori M, Mikala G, Mori Y. Auxiliary subunits operate as a molecular switch in determining gating behaviour of the unitary N-type Ca2+ channel current in Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol. 1999;517:659–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0659s.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu W, Lipscombe D. Neuronal Ca(V)1.3alpha1 L-type channels activate at relatively hyperpolarized membrane potentials and are incompletely inhibited by dihydropyridines. J Neurosci. 2001;21:5944–5951. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-05944.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]