Abstract

The photoreceptors lie between the inner retina and the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). The release of glutamate by the phototoreceptors can signal changes in light levels to inner retinal neurons, but the role of glutamate in communicating with the RPE is unknown. Since RPE cells are known to release ATP, we asked whether glutamate could trigger ATP release from RPE cells and whether this altered cell signalling. Stimulation of the apical face of fresh bovine RPE eyecups with 100 μm NMDA increased ATP levels more than threefold, indicating that both receptors for NMDA and release of ATP occurred across the apical membrane of fresh RPE cells. NMDA increased ATP levels bathing cultured human ARPE-19 cells more than twofold, with NMDA receptor inhibitors MK-801 and d-AP5 preventing this release. Blocking the glycine site of the NMDA receptor with 5,7-dichlorokynurenic acid prevented ATP release from ARPE-19 cells. Release was also blocked by channel blocker NPPB and Ca2+ chelator BAPTA, but not by cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) blocker glibenclamide or vesicular release inhibitor brefeldin A. Glutamate produced a dose-dependent release of ATP from ARPE-19 cells that was substantially inhibited by MK-801. NMDA triggered a rise in cell Ca2+ that was blocked by MK-801, by the ATPase apyrase, by the P2Y1 receptor antagonist MRS2179 and by depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores with thapsigargin. These results suggest that glutamate stimulates NMDA receptors on the apical membrane of RPE cells to release ATP. This secondary release can amplify the glutaminergic signal by increasing Ca2+ inside RPE cells, and might activate Ca2+-dependent conductances. The interplay between glutaminergic and purinergic systems may thus be important for light-dependent interactions between photoreceptors and the RPE.

Interaction between neuronal and non-neuronal cells contributes to the development and function of the nervous system. Multiple mechanisms underlie this two-way communication, including the control over excitability through extracellular ion concentrations, the maintenance of an extracellular matrix and the release of neurotransmitters. While the ability of neurons to stimulate non-neuronal cells has been recognized for many decades, recent evidence demonstrates that non-neuronal cells can release transmitters using complex mechanisms and modulate neuronal behaviour (Araque et al. 2001).

The photoreceptors are located between the inner retina and the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). The RPE monolayer performs many functions to support the photoreceptors, such as controlling the ion and fluid levels in the small subretinal space which separates the two cell types (Miller & Steinberg, 1977a,b; Miller et al. 1982; Hughes et al. 1984; Edelman & Miller, 1991) and supplying the neural retina with nutrients, growth factors and recycled visual pigments (Young & Bok, 1969; Chader et al. 1998). The transmitters dopamine (Gallemore & Steinberg, 1990; Versaux-Botteri et al. 1997) serotonin (Nash & Osborne, 1997; Nash et al. 1999) and adrenaline (Edelman & Miller, 1991; Joseph & Miller, 1992; Quinn et al. 2001) may influence retinal–RPE communication by stimulating receptors on RPE cells. While these transmitters all contribute to visual signalling in the retina, glutamate is the primary transmitter released by photoreceptors, with release rates inversely proportional to light levels (Witkovsky et al. 1997). Although glutamate is well known to act on bipolar cells to initiate visual signalling (Bloomfield & Dowling, 1985; Copenhagen, 1991), glutamate released from photoreceptors might also diffuse in the opposite direction towards the apical tips of the RPE.

Considerable evidence suggests that glutamate signalling is important for RPE function. Glutamate transporters EAAT4 and EAAT1 are present on the RPE and are expected to restrict extracellular levels of glutamate in the subretinal space (Maenpaa et al. 2002, 2003, 2004). Ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptors have been identified in chick and human RPE cells (Lopez-Colome et al. 1993; Lopez-Colome & Fragoso, 1995), while activation of NMDA receptors (NMDARs) in RPE cells increases proliferation (Uchida et al. 1998) and inositol triphosphate (IP3) levels (Fragoso & Lopez-Colome, 1999). In glial cells, propagation of the initial signal can occur when elevated IP3 levels lead to the release of ATP, which in turn stimulates purinergic P2 receptors on neighbouring cells (Sauer et al. 2000; Schwiebert, 2000). Such paracrine activation by released ATP is widely used to amplify signals, and interactions between purinergic and glutaminergic systems are involved in the bidirectional communication between neurons and astrocytes in the brain (Mazzanti et al. 2001).

Although it is not yet known whether released ATP amplifies the glutamate signal in RPE cells, many of the necessary components are present. In addition to the glutamate receptors described above, multiple receptor types for ATP are present on the RPE (Sullivan et al. 1997; Ryan et al. 1999; Reigada et al. 2005). Retinal pigment epithelium cells are also known to release ATP, which can in turn autostimulate the cells (Mitchell, 2001; Reigada & Mitchell, 2005a). We therefore asked whether glutamate acting on NMDARs could trigger ATP release from RPE cells, and whether this stimulation could modify intracellular signalling.

Portions of this work have been presented previously in abstract form (Reigada & Mitchell, 2005b; Reigada et al. 2006a).

Methods

Materials and solutions

All chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich, Inc. (St Louis, MO, USA) unless otherwise noted. The isotonic solution was composed of (mm): 105 NaCl, 5 KCl, 6 Hepes acid, 4 HepesNa2, 5 NaHCO3, 60 mannitol, 5 glucose, 0.5 MgCl2 and 1.3 CaCl2, pH 7.4. dl-2-Amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (d-AP5), 5,7-dichlorokynurenic acid (DCKA) and 5-nitro-2-(3-phenylpropyl-amino)-benzoate (NPPB) were dissolved in a dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) stock solution. N-Methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA), l-glutamic acid (glutamate), pyridoxal-phosphate-6-azophenyl-2′,4′-disulphonate (PPADS), 18α-glycyrrhetinic acid (18αGA), apyrase, oleamide, thapsigargin, N6-methyl-2′-deoxyadenosine-3′,5′-bis-phosphate (MRS2179) and (+)-5-methyl-10,11-dihydro [a,d]cyclohepten-5,10-imine hydrogen maleate (MK-801) were prepared as aqueous stock solutions and diluted to the working concentration in isotonic solution. To control for non-specific effects that frequently complicate analysis of ATP release, all chemicals were tested for their effect on the luciferin–luciferase assay, as shown in Fig. 1.

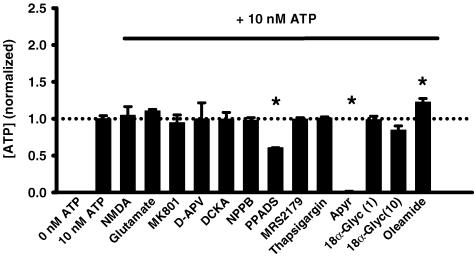

Figure 1. Effect of drugs on luciferin–luciferase reaction.

Since the luciferin–luciferase assay is modulated by many compounds, all drugs used in this study were examined for their non-specific effect on detection of 10 nm ATP in a cell-free preparation. None of NMDA (300 μm), glutamate (300 μm, n = 8), MK-801 (30 μm, n = 8), d-AP5 (100 μm, n = 8), DCKA (30 μm, n = 8), NPPB (30 μm, n = 10), MRS2179 (100 μm, n = 6), thapsigargin (1 μm, n = 6) or 18α-glycyrrhetinic acid (1 and 10 μm, n = 5) produced a significant shift in the luminescence compared with control levels (n = 28). PPADS produced a decrease in the luciferase activity and the ecto-ATPase apyrase (1 U ml−1, n = 6) produced the expected reduction in the luminescence levels by hydrolysing the ATP content of the sample, while oleamide (300 μm, n = 5) enhanced the signal. Bars show means +s.e.m. for values normalized to the corresponding control level. *P < 0.05 versus control value.

Measurements of ATP from bovine eyes

Release of ATP was determined with the luciferin–luciferase reporting system. Previous experience with this system has shown that the increased levels of extracellular ATP represent physiological release (Mitchell et al. 1998; Mitchell, 2001; Reigada et al. 2005), although the concentrations detected are likely to be orders of magnitude below that found at the membrane surface (Joseph et al. 2003; Okada et al. 2006). The luciferase solution was prepared in a stock solution from one vial of the luciferin–luciferase assay kit (Sigma-Aldrich Inc.) diluted in 450 μl of the isotonic solution and 50 μl distilled water. This stock solution was stored at −20°C.

Bovine eyes were obtained from the abattoir and transported on ice to the laboratory, with the approval of the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Eyes were bisected at the ora serrata, with the retina removed and detached from the optic nerve. In this configuration, the apical membrane of the RPE faces the interior of the eyecup and, in the presence of intact tight junctions, polarity is likely to be maintained (Reigada & Mitchell, 2005a). After washing the RPE eyecup three times with isotonic solution, 500 μl of test solution was added to the eyecup. After 10 min at room temperature (21–25°C), a 400 μl sample was removed, rapidly frozen and stored at −20°C until analysis. To determine the ATP content of the solution from each eyecup, a luciferase working solution was prepared by diluting 40 μl of the stock solution described above in 1 ml isotonic buffer. The eyecup sample was defrosted, with 90 μl of sample placed in a single well of a 96-well plate, which was in turn put into the microplate luminometer (Luminoskan Ascent, Labsystems; Franklin, MA, USA), and 10 μl of the luciferase working solution was injected into each well. Measurements were taken at room temperature every 30 s for 10 min with an integration time of 100 ms per measurement. A standard curve showed the relationship between luminescence and ATP concentration to be linear over the range tested and was used to convert luminescence units into ATP concentration.

Cell culture

The ARPE-19 cell line (Dunn et al. 1998) was obtained from American type culture collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA, USA) and grown to confluence in 25 cm2 Primaria culture flasks (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) in a 1:1 mixture of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) and Ham's F12 medium with 3 mml-glutamine, 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin and 2.5 mg ml−1 Fungizone and/or 50 μg ml−1 gentamicin (all Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, UT, USA). Cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 (with the remainder being air) and subcultured weekly with 0.05% trypsin and 0.02% EDTA.

ARPE-19 cells used for ATP release experiments were plated in 96-well white plates with clear bottoms (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) and grown to confluence using the medium described above. Peripheral wells were typically left blank to avoid gradients of gas exchange across the plate. Solution change can trigger a release of ATP (Grygorczyk & Hanrahan, 1997), and our trials indicated that both 10% FBS and the phenol contained in the regular DMEM interfered with the luciferase assay. To avoid these artifacts, the growth medium bathing ARPE-19 cells used for most ATP release experiments was replaced after 4–7 days with 100 μl of a 1:1 mixture of DMEM without phenol (Invitrogen Corp.) and Ham's F12 plus 1% FBS with 3 mml-glutamine, 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin and 2.5 mg ml−1 Fungizone and/or 50 μg ml−1 gentamicin, defined as ‘differentiation medium’. Cells were subsequently grown for an additional week. This differentiation medium did not affect the luciferase activity and could be used as working solution in on-line experiments.

Measurements of ATP from ARPE-19 cells

ATP release from ARPE-19 cells was detected using the luciferin–luciferase reaction as described above. In most cases, 80 μl of the total 100 μl differentiation medium were replaced with 20 μl differentiation medium containing a concentrated level of agonist shortly before the experiment began, to avoid full solution change. The 96-well plate was inserted into the luminometer, 10 μl of the luciferase working solution in light medium was injected and the plate gently mixed for 10 s. This gentle mix had negligible effects on ATP release and was present in both control and experimental wells. Measurements were typically taken every 20 s for 30 min with an integration time of 100 ms per measurement.

To study the initial kinetics of ATP release, 60 μl of differentiation medium were replaced with 5 μl of the luciferin–luciferase working solution, for a total volume of 45 μl. The 96-well plate was placed in the luminometer, baseline levels were recorded for 1 min, and then 5 μl concentrated NMDA was injected into each well to produce a final concentration of 300 μm. Differentiation medium without NMDA was injected into control wells. Measurements were taken every 1 s for 5 min with an integration time of 100 ms per measurement.

For experiments involving blockers, all differentiation medium was replaced with 100 μl differentiation medium containing blockers at working strength and incubated for 30 min at 37°C (120 min for brefeldin A). Shortly before the experiment, 80 μl were removed and replaced with 20 μl blocker solution plus agonist. Since the 10 μl added luciferase solution did not contain blocker, the blocker level during experiments was only 80% of that used during incubation. In the glutamate dose–response experiments, the traditional growth medium was removed from the cells and replaced by 100 μl of isotonic solution immediately before the experiment. After 1 h in the incubator, 50 μl of the isotonic solution was replaced by 50 μl of a solution containing twice the working glutamate concentration and recordings made as detailed above. While ATP release from cells using this protocol was not generally as high, the proportional increase in ATP was similar.

Immunohistochemistry

ARPE-19 cells were plated at low density on round glass coverslips for 2 days in differentiation medium. The cells were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (in mm 2.6 KCl, 1.5 KH2PO4, 134 NaCl, 8 Na2HPO4, 0.9 CaCl2, 0.5 MgCl2) and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 30 min at 4°C. After washing with PBS, the sample was incubated in blocking buffer composed of 10% Superblock (Pierce Biotechnology Inc., Rockford, IL, USA) diluted in PBS with 0.1% Tween 20. After being washed with PBS and 0.1% Tween 20 (washing buffer) the cells were incubated overnight at 4°C with a mouse anti-NMDAR1 monoclonal antibody against the extracellular loop of the NR1 subunit (clone 54.1, MAB363; Chemicon International, Inc., Temecula, CA, USA) diluted 1:200 in blocking buffer. The negative controls were incubated with the same solution but without the primary NMDAR1 antibody. Cells were then washed three times with washing buffer and incubated with donkey antimouse antibody conjugated with biotin (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., West Grove, PA, USA) at 1:300 dilution in blocking buffer for 30 min at room temperature. Samples were washed three times in washing buffer and incubated with Cy2-conjugated Streptavidin diluted 1:300 in blocking buffer for 30 min at room temperature (Jackson ImmunoResearch). After three final washes, coverslips were mounted with a fluorescent mounting medium containing 4′, 6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) to visualize the nuclei (H-1200, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Pictures were taken on a Nikon Eclipse 600 microscope equipped for epifluorescence (Nikon USA, Melville, NY, USA) with a 3-CCD digital camera (Toshiba America, Irvine, CA, USA) and analysed on-line using Image Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA). DAPI was imaged with 360 nm excitation and > 515 nm emission, while Cy2 was excited at 480 nm with emission > 535 nm.

To confirm staining, a second antibody raised against the C-terminal of the NR1 subunit was used (1:200 in blocking buffer, AB1516, polyclonal; Chemicon International, Inc.). In parallel preparations, the primary antibody was preabsorbed with the C-terminal peptide (both 1:200, AG344; Chemicon International, Inc.) at room temperature for 2 h as a control. Both preparations were added to ARPE-19 cells overnight at 4°C and processed as above using a biotinylated goat antirabbit secondary antibody (1:300; DAKO Corp., Carpinteria, CA, USA).

Intracellular calcium measurements

ARPE-19 cells were plated in 96-well black plates with clear bottoms (Corning Inc. Corning, NY, USA) and grown to confluence for 4–7 days in the growth medium described above, then maintained in differentiation medium for an additional week. After washing the wells with isotonic solution plus 250 μm glycine, cells were loaded with 10 μm fura-2 AM and 0.2% Pluronic F127 (both Invitrogen Corp.) in isotonic solution plus glycine and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The antagonists and blockers used in the different experiments were added to the fura-2 AM loading solution. After two washes, 90 μl of isotonic solution plus glycine was added to each well. The basal intracellular Ca2+ levels were measured by alternatively exciting at 340 and 380 nm and measuring the fluorescence emitted at 510 nm in a microplate fluorometer (Fluoroskan Ascent; Labsystems, Franklin, MA, USA). After a 5 min baseline reading, 10 μl isotonic solution plus glycine with or without NMDA and/or blocker (all 10 times working strength) were injected into each well using the fluorometer injector system. Conversion to Ca2+ concentration was performed as previously described (Mitchell, 2001) with the following adaptations for the 96-well plate system. Calibration was performed simultaneously in a subset of wells on the plate, with ‘maximum’ solution composed of 5 μm ionomycin in isotonic solution, and ‘minimum’ solution made of 5 μm ionomycin and 20 mm EGTA in isotonic solution, both pH 8.0. Background levels from a subset of wells not loaded with dye were subtracted.

Data analysis

Levels of ATP were determined by integrating the area under the curve for each record. Baseline levels of ATP varied considerably with experimental day for both fresh and cultured experiments. To allow comparison of experiments, ATP concentrations were normalized to the mean control ATP level for each day. All of the data were expressed as means ± s.e.m.; n is the number of independent trials or wells, with data typically representing results from two to six separate plates. Significant differences were tested using Student's paired t test when only two conditions were present and a one-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test when more than two conditions were present. Analysis was performed with SigmaStat Software (Systat Software Inc., Point Richmond, CA, USA) with P < 0.05 defined as significantly different.

Results

Release of ATP from bovine RPE eyecup

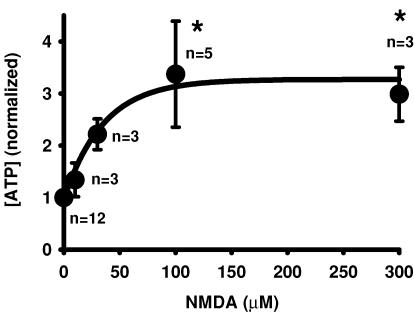

The effect of NMDA on ATP release was initially examined using the fresh bovine RPE eyecup. In this preparation, tight junctions were generally well maintained and the apical membrane faced the interior of the eyecup, so receptors and release could be functionally localized to the apical membrane. The glutamate receptor agonist NMDA triggered a clear, consistent and concentration-dependent release of ATP from the bovine RPE eyecup. Levels of bath ATP increased from 1.8 ± 0.1 nm (n = 10) in control conditions to 6.0 ± 1.8 nm (n = 5) in 100 μm NMDA when measured 10 min after addition of the agonist. While these levels are low, this is the concentration of released ATP after it diffuses into 500 μl solution, and concentrations in the subretinal space are expected to be several orders of magnitude higher, as demonstrated by comparison with measurements using a cell-surface luciferase (Joseph et al. 2003; Okada et al. 2006). To facilitate comparison, levels were normalized to the mean control for each day's experiments. In five experiments, mean ATP levels in the eyecup were 3.4 ± 1.0-fold greater than control values after 10 min in the presence of 100 μm NMDA, with an EC50 of 32 μm (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. NMDA triggers release of ATP from bovine RPE eyecup.

When added to the apical face of a bovine RPE eyecup preparation, NMDA triggered a concentration-dependent increase in bath levels of ATP. Both 100 and 300 μm NMDA elevated ATP levels more than threefold, giving an EC50 of 32 μm. Symbols represent the means ± s.e.m. from the number of eyes indicated, with concentrations normalized to the mean control levels for each experimental set. *P < 0.05 versus control value. The line is a fit of the exponential rise y = y0 + a(1 − e−bx) with y0 = 0.97, a = 2.3 and b = 0.028.

Release of ATP from ARPE-19 cells

While experiments with the bovine eyecup suggested that NMDA triggered a release of ATP across the apical membrane of fresh RPE cells, more detailed pharmacological analysis was performed using cultured human ARPE-19 cells. These cells enabled the release of ATP to be measured on-line using a high-throughput screening system while also providing information from human cells.

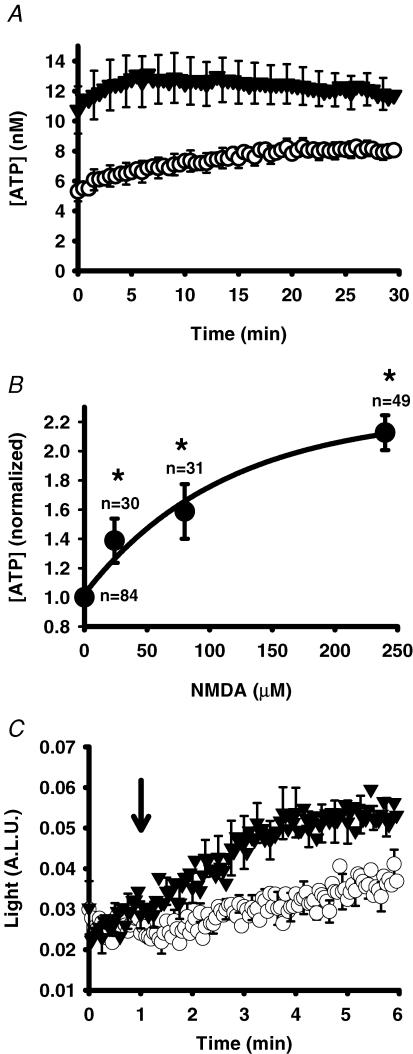

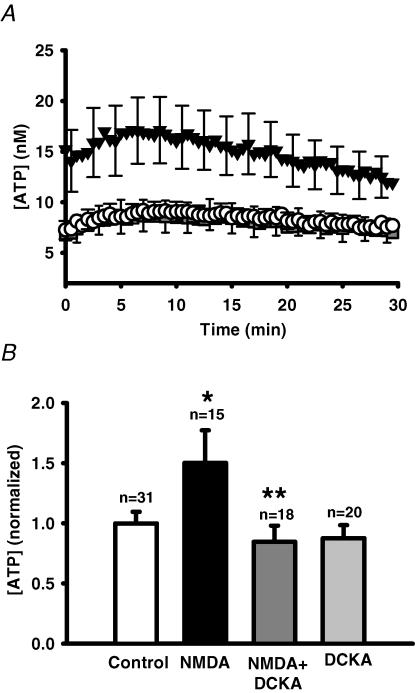

NMDA triggered release of ATP from ARPE-19 cells (Fig. 3A). The concentration of ATP in the bath rose for the first 5–10 min after recording began, with levels typically peaking at ∼7 min before reaching a plateau or declining slightly. This time course suggested that measurements made from the fresh bovine RPE eyecup after 10 min were appropriate. In ARPE-19 cells, as in the bovine RPE eyecup, the magnitude of this increase was dependent upon the concentration of NMDA. A significant increase in bath ATP over control values was detected with only 24 μm NMDA, and levels of ATP doubled in the presence of 240 μm (EC50 of 63 μm; Fig. 3B). In these experiments, agonist was added to the cells 3–4 min before recording began, and initial recordings began with NMDA levels considerably higher than control values. To obtain a better understanding of response kinetics, we modified the protocol so that recordings were obtained at higher frequency and so that levels could be monitored shortly before and after injection of NMDA. Levels of ATP were initially the same but increased rapidly after injection of NMDA (Fig. 3C). The concentration of ATP increased by 1.7 ± 0.2-fold after 3 min in 300 μm NMDA, analogous to the increase observed at the initial points of the experiments in Fig. 3A and B.

Figure 3. NMDA triggers release of ATP from ARPE-19 cells.

A, mean traces from representative experiments showing the time-dependent changes in ATP levels surrounding ARPE-19 cells following addition of NMDA (240 μm, ▾) versus control cells (○). Recording began 3–5 min after addition of drugs to cells. Symbols represent the means ± s.e.m. (n = 49). B, increasing concentrations of NMDA produced increasing levels of ATP bathing ARPE-19 cells. Levels of ATP were determined from the area under the curve for the 30 min duration of experiments like those illustrated in A and normalized to the mean control level for each day. The symbols represent the means ± s.e.m.*P < 0.05 versus control value. The line is a fit of the single exponential rise y = y0+a(1 − e−bx) with y0 = 1.02, b = 0.009 and a = 1.24. C, ATP was rapidly detected by injecting either control medium (○) or NMDA (working strength 300 μm, ▾) into each well as indicated by the arrow, and recording at 1 Hz. Increased levels of ATP were first detected within 30 s of the NMDA injection (n = 8). A.L.U., arbitrary light units.

Pharmacological analysis of NMDA response

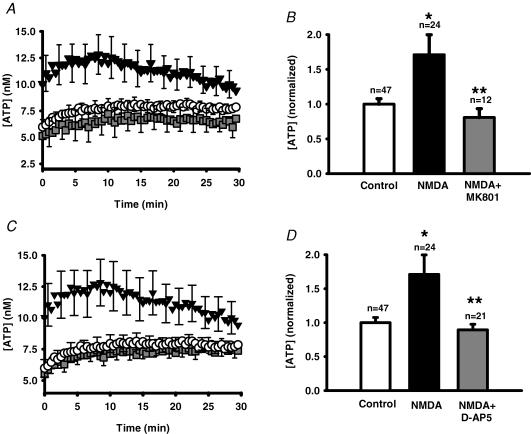

Additional experiments were undertaken to confirm that release of ATP was mediated by stimulation of the NMDA receptor. The NMDA receptor antagonists MK-801 (24 μm; Fig. 4A and B) and d-AP5 (80 μm; Fig. 4C and D) prevented the ability of NMDA to trigger a release of ATP from ARPE-19 cells. In both cases, NMDA alone triggered a robust response similar to that described above, with ATP levels ∼1.7-fold greater than control at the peak.

Figure 4. NMDA receptor antagonists block the NMDA-stimulated ATP release.

A, mean traces from representative experiments showing the ATP release from ARPE-19 cultured cells stimulated by 240 μm NMDA (▾) versus control cells (○). Inclusion of the NMDA receptor blocker MK-801 (24 μm,  ) blocked NMDA-stimulated ATP release. Cells were pre-incubated with 30 μm MK-801 for 30 min before recording began. Symbols represent the means ± s.e.m., n = 16. B, quantification of the total amount of ATP in the bath over the 30 min record indicated that MK-801 (24 μm, grey bar) significantly inhibited the NMDA-stimulated ATP release (240 μm NMDA, filled bar, NMDA alone). *P < 0.05 versus control (open bar); **P < 0.05 versus NMDA alone; MK-801 + NMDA not significantly different from control value. Bars indicate means +s.e.m.C, mean traces from representative experiments showing the effect of a second NMDA receptor antagonist, d-AP5 (80 μm,

) blocked NMDA-stimulated ATP release. Cells were pre-incubated with 30 μm MK-801 for 30 min before recording began. Symbols represent the means ± s.e.m., n = 16. B, quantification of the total amount of ATP in the bath over the 30 min record indicated that MK-801 (24 μm, grey bar) significantly inhibited the NMDA-stimulated ATP release (240 μm NMDA, filled bar, NMDA alone). *P < 0.05 versus control (open bar); **P < 0.05 versus NMDA alone; MK-801 + NMDA not significantly different from control value. Bars indicate means +s.e.m.C, mean traces from representative experiments showing the effect of a second NMDA receptor antagonist, d-AP5 (80 μm,  ), on the ATP release triggered by 240 μm NMDA (▾). Cells in control solution are indicated by ○; n = 16. Cells were pre-incubated in 100 μmd-AP5 for 30 min before recording began. D, quantification of the ATP released over 30 min indicates that while 240 μm NMDA (filled bar) significantly increased ATP release over control levels (open bar), co-incubation with 80 μmd-AP5 (grey bar) blocked this release. *P < 0.05 versus control (open bar); **P < 0.05 versus NMDA alone; d-AP5 + NMDA not significantly different from control value.

), on the ATP release triggered by 240 μm NMDA (▾). Cells in control solution are indicated by ○; n = 16. Cells were pre-incubated in 100 μmd-AP5 for 30 min before recording began. D, quantification of the ATP released over 30 min indicates that while 240 μm NMDA (filled bar) significantly increased ATP release over control levels (open bar), co-incubation with 80 μmd-AP5 (grey bar) blocked this release. *P < 0.05 versus control (open bar); **P < 0.05 versus NMDA alone; d-AP5 + NMDA not significantly different from control value.

Activation of the NMDA receptor requires binding to both the glutamate/NMDA site and to a glycineB site (Johnson & Ascher, 1987; Danysz et al. 1998). The growth medium used for these experiments already contained 250 μm glycine, and further addition of glycine did not enhance extracellular levels of ATP (not shown). As discussed in the Methods, the sensitivity of ATP detection was enhanced by not changing medium beforehand, making it difficult to remove glycine. The contribution of this glycine could however, be determined with 5,7-dichlorokynurenic acid (DCKA), an antagonist at the glycineB binding site of the NMDA receptor. Although it had no effect in the absence of NMDA, 24 μm DKCA completely inhibited the response to NMDA (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Block of NMDAR glycineB sites with DCKA prevents NMDA-stimulated ATP release.

A, mean traces from representative experiments showing changes in ATP release from ARPE-19 cultured cells stimulated by 300 μm NMDA (▾) versus control cells (○). The glycineB site antagonist DCKA (24 μm) blocked NMDA-stimulated ATP release ( ). Data points show the means ± s.e.m. In all cases, growth medium contained 250 μm glycine. Cells were pre-incubated with 30 μm DCKA for 30 min before recording began. B, quantification of the total ATP released over 30 min indicates DCKA (24–30 μm, dark grey bar) produced a significant inhibition of the NMDA-stimulated ATP release (filled bar). The addition of DCKA alone (30 μm, light grey bar) did not significantly change ATP levels. *P < 0.05 versus control value (white bar); **P < 0.05 versus NMDA alone.

). Data points show the means ± s.e.m. In all cases, growth medium contained 250 μm glycine. Cells were pre-incubated with 30 μm DCKA for 30 min before recording began. B, quantification of the total ATP released over 30 min indicates DCKA (24–30 μm, dark grey bar) produced a significant inhibition of the NMDA-stimulated ATP release (filled bar). The addition of DCKA alone (30 μm, light grey bar) did not significantly change ATP levels. *P < 0.05 versus control value (white bar); **P < 0.05 versus NMDA alone.

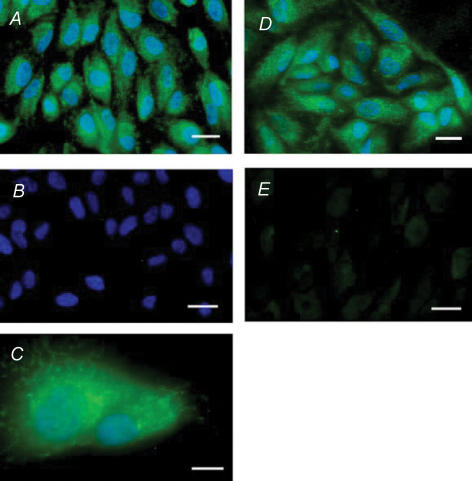

Identification of NMDAR1 receptor

The pharmacological identification of the NMDA receptor was supported by immunohistochemical identification of the NMDAR1 (NR1) subunit in ARPE-19 cells. Dense staining was detected across the cell (Fig. 6). Staining was punctate, although permeablization of the cell membrane with the paraformaldehyde used for fixation precludes identification of these punctate clusters as either intracellular or extracellular. Staining was verified with two different antibodies against NR1 and was greatly reduced by competition with the relevant peptide.

Figure 6. The NMDAR1 subunit of the NMDA glutaminergic receptor is present in ARPE-19 cells.

A, a monoclonal antibody against the extracellular loop of NMDAR1 (NR1; MAB363) produced clear and abundant staining (green). DAPI localized to cell nuclei (blue). Scale bar represents 20 μm. B, no staining was observed in the absence of the primary antibody (MAB363), while blue DAPI staining testified to the presence of cells. Scale bar represents 20 μm. C, higher magnification image shows diffuse staining for NMDAR1 with antibody MAB363 across the cell (green). Punctate green staining was also detected and was frequently around the nucleus, stained blue with DAPI. Scale bar represents 10 μm. D, similar staining was observed using a polyclonal antibody raised against the C-terminal of the NR1 subunit (AB1516; green). DAPI localizes cell nuclei (blue). Scale bar represents 20 μm. E, no staining was observed when the primary antibody, AB1516, was pre-absorbed with its specific peptide (AG344). Scale bar represents 20 μm.

Glutamate acts at NMDAR to trigger release

The actions of NMDA, the ability of MK-801 and d-AP5 to completely block the response to NMDA, and the immunological identification of NMDAR1 subunit on ARPE-19 cells strongly suggested that activation of the NMDA receptor could trigger ATP release. However, the endogenous agonist is expected to be glutamate, and both ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptors are present on RPE cells (Lopez-Colome et al. 1993; Lopez-Colome & Fragoso, 1995). Experiments were performed to determine whether glutamate itself could trigger ATP release and what proportion of this response was mediated by the NMDA receptor. Addition of glutamate triggered release of ATP from cells with a similar magnitude to NMDA (Fig. 7A). Peak levels were observed 5–10 min after recording began, although levels did decline more than with NMDA over the course of 30 min, which is consistent with the presence of glutamate transporters. The ATP levels increased in a concentration-dependent manner, with an EC50 of 24 μm (Fig. 7B). MK-801 produced a nearly complete block of ATP release triggered by 240 μm glutamate (Fig. 7C and D), suggesting that most of the release resulted from activation of the NMDA receptors.

Figure 7. Glutamate-stimulated ATP release from ARPE-19 cells.

A, mean values from representative traces demonstrating the ATP release from ARPE-19 cells triggered by 240 μm glutamate (▾) versus control cells (○). Of note, the decay rate was faster than that observed with NMDA. Symbols represent the means ± s.e.m., n = 8. B, the increase in ATP triggered by glutamate was dependent upon concentration. Data were normalized to the mean control of the experimental set for each day. Symbols represent the mean ± s.e.m. of each data point. *P < 0.05 versus control value (0 μm). The line is a fit of the exponential rise y = y0+ a(1 − e−bx) with y0 = 1.01, b = 0.003 and a = 0.87. C, mean values from traces in a representative experiment showing the inhibition of the time-dependent glutamate-induced ATP release from ARPE-19 cells (240 μm, ▾) by the NMDA blocker MK-801 (24 μm,  ), returning to control levels (○). Symbols represent the means ± s.e.m., n = 8. Cells were pre-incubated with 30 μm MK-801 for 30 min before recording began. D, quantification of the integrated amount of ATP over 30 min from experiments such as those illustrated in C indicates that while 240 μm glutamate (filled bar) significantly increased ATP release above control levels (white bar), co-incubation with 24 μm MK-801 blocked this release. *P < 0.05 versus control value (white bar); **P < 0.05 versus glutamate; MK-801 + NMDA not significantly different from control value.

), returning to control levels (○). Symbols represent the means ± s.e.m., n = 8. Cells were pre-incubated with 30 μm MK-801 for 30 min before recording began. D, quantification of the integrated amount of ATP over 30 min from experiments such as those illustrated in C indicates that while 240 μm glutamate (filled bar) significantly increased ATP release above control levels (white bar), co-incubation with 24 μm MK-801 blocked this release. *P < 0.05 versus control value (white bar); **P < 0.05 versus glutamate; MK-801 + NMDA not significantly different from control value.

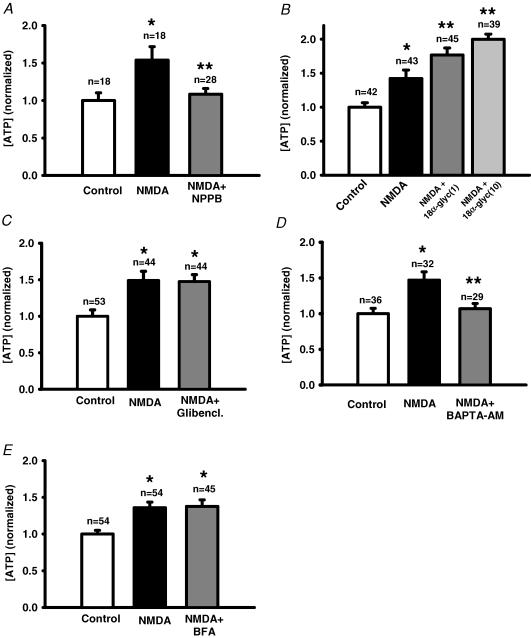

Mechanisms of NMDA-induced ATP release

The conduit for ATP release following stimulation of the NMDA receptor was probed. The channel blocker NPPB completely blocked the response (Fig. 8A). Although the gap-junction blocker 18αGA can inhibit ATP release from embryonic chick RPE cells (Pearson et al. 2005), it increased ATP levels in ARPE-19 cells (Fig. 8B), while the gap-junction blocker oleamide had a non-specific effect on the luciferase reaction (Fig. 1). The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) blocker glibenclamide had no effect on ATP release (Fig. 8C). Since NMDA can elevate cellular Ca2+, we asked whether Ca2+ played a role in this ATP release. Chelation of intracellular Ca2+ levels with BAPTA AM reduced the NMDA-induced ATP release by 85% (Fig. 8D). Since increased intracellular Ca2+ can trigger a vesicular release of transmitter from both neuronal and non-neuronal cells, and since brefeldin A (BFA) can impede vesicular release of ATP from other epithelial cells (Knight et al. 2002), the effect of BFA on release was examined. However, BFA had no effect on the ability of NMDA to trigger release of ATP from ARPE-19 cells (Fig. 8E).

Figure 8. Mechanisms for ATP release.

A, the channel blocker NPPB (30 μm, grey bar) inhibited the NMDA-stimulated ATP release (240 μm; filled bar). Here and throughout the figure, *P < 0.05 versus control value; **P < 0.05 versus NMDA, and control value is indicated by an open bar. In A, NPPB + NMDA were not significantly different from control value. B, the gap/hemichannel blocker 18αGA (1 and 10 μm; grey bars) increased ATP levels compared with NMDA alone (240 mm; filled bar). This response did not result from a non-specific interaction with the luciferase assay (Fig. 1). C, the CFTR blocker glibenclamide (80 μm, Glibencl.; grey bar) did not inhibit the NMDA-stimulated ATP release (240 μm; filled bar). D, clamping intracellular Ca2+ with the chelator BAPTA AM (16 μm, grey bar) completely blocked the NMDA-stimulated ATP release (filled bar). E, ATP release triggered by 240 μm NMDA (filled bar) was not significantly altered by treatment with BFA (8 μg ml−1, grey bar).

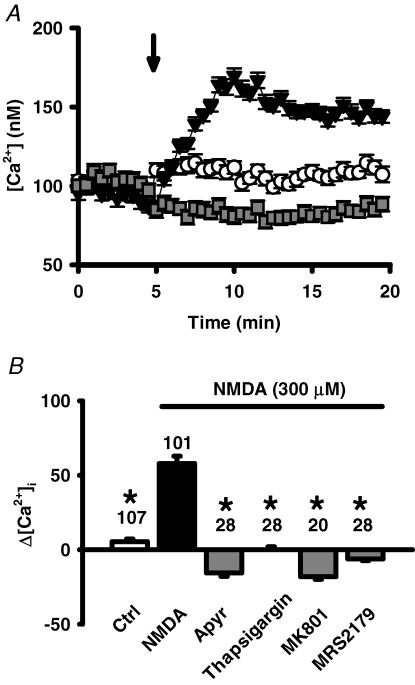

Effect of release on intracellular Ca2+

Exogenously added ATP can activate both ionotropic P2X and metabolic P2Y receptors and effectively raise the intracellular Ca2+ levels of RPE cells (Sullivan et al. 1997; Ryan et al. 1999; Reigada et al. 2005a). We wanted to know whether ATP released following NMDA receptor stimulation could likewise elevate Ca2+. In cells loaded with the ratiometric Ca2+-sensitive dye fura-2, addition of NMDA led to an increase in Ca2+ levels (Fig. 9A). This icrease in Ca2+ peaked 5 min after addition of NMDA, similar to the time course found for ATP release, and was prevented by the ATP chelator apyrase. This peak Ca2+ response was also blocked by the NMDAR blocker MK-801, by the P2Y1 receptor antagonist MRS2179, and by depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores with thapsigargin (Fig. 9B). Surprisingly, a rise in Ca2+ levels shortly after application of the NMDA was not detected. Attempts to block a secondary influx of Ca2+ with the Ca2+ channel blocker nifedipine were complicated by the dose-dependent increase in ATP release triggered by nifedipine in the presence of glutamate and NMDA (both 240 μm), but not in control conditions.

Figure 9. NMDA-triggered release of ATP raises Ca2+.

A, the co-application (▾) of NMDA (300 μm) and glycine (250 μm, arrow), increased intracellular Ca2+ from baseline levels when compared to addition of control solution (○). This increase was prevented by the ecto-ATPase apyrase (1 U ml−1,  ). Symbols represent the means ± s.e.m., n = 20–28. Cells were pre-incubated with 1 U ml−1 apyrase for 30 min before recording began. B, quantification of the increase in Ca2+ peak levels, expressed as percentage increase over pre-addition levels. Calcium levels 5 min after addition of control solution or NMDA or NMDA + drug were compared to mean basal levels before application, using the protocol illustrated in A. While NMDA + glycine (filled bar) significantly increased Ca2+ levels over control levels (open bar), the presence of with 1 U ml−1 apyrase, 1 μm thapsigargin, 30 μm MK-801 and 100 μm MRS2179 (grey bars) all blocked this increase. *P < 0.05 versus NMDA alone.

). Symbols represent the means ± s.e.m., n = 20–28. Cells were pre-incubated with 1 U ml−1 apyrase for 30 min before recording began. B, quantification of the increase in Ca2+ peak levels, expressed as percentage increase over pre-addition levels. Calcium levels 5 min after addition of control solution or NMDA or NMDA + drug were compared to mean basal levels before application, using the protocol illustrated in A. While NMDA + glycine (filled bar) significantly increased Ca2+ levels over control levels (open bar), the presence of with 1 U ml−1 apyrase, 1 μm thapsigargin, 30 μm MK-801 and 100 μm MRS2179 (grey bars) all blocked this increase. *P < 0.05 versus NMDA alone.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that the stimulation of NMDA receptors can trigger the release of ATP from RPE cells.

Evidence for the involvement of NMDA receptors is compelling. First, NMDA itself triggered a release of ATP from both fresh bovine and cultured human RPE cells over the range 25–300 μm, with an EC50 similar to that reported for cloned NMDA receptors (Moriyoshi et al. 1991; Kurko et al. 2005). Second, this NMDA-induced ATP release from ARPE-19 cells was blocked by two different NMDA-specific inhibitors, the non-competitive antagonist MK-801 acting in the permeation pathway and the competitive antagonist d-AP5 acting at the agonist binding site (Morris et al. 1986; Davis et al. 1992). Third, block by DCKA in the presence of glycine implies a requirement for the costimulation of the glycineB binding site on the NMDA receptor (Baron et al. 1990). Fourth, the NMDAR1 subunit was detected in these cells using two different antibodies. Finally, glutamate triggered a response at a lower concentration than NMDA, and this response was largely blocked by MK-801 (Wong et al. 1986). This suggests that most of the response to glutamate was mediated by the NMDA receptor, consistent with previous reports that stimulation of the NMDA receptor was more effective at raising IP3 in the RPE than other glutaminergic receptors (Fragoso & Lopez-Colome, 1999).

The ability of NMDA to trigger ATP release from both fresh bovine and cultured human ARPE-19 cells strengthens the potential relevance of this glutaminergic–purinergic interaction. The release from the interior of the bovine RPE eyecup implies that NMDA receptors are on the apical membrane and that ATP release occurs across the apical membrane into the subretinal space. While ARPE-19 cells typically lack polarity, previous work has found many similarities in the mechanisms of ATP release from ARPE-19 and fresh bovine RPE cells (Reigada & Mitchell, 2005a; Reigada et al. 2005). The release from bovine cells was proportionally larger and required lower concentrations of NMDA, suggesting that the system in fresh cells may be more sensitive. Although we do not yet now whether this reflects a difference in receptor number, receptor sensitivity or whether the cells are more ready to release ATP, it does suggest that data from ARPE-19 cells are likely to underestimate the effect on fresh RPE cells.

Mechanism of ATP release

The release of ATP triggered by NMDA was blocked by the broad-acting channel blocker NPPB and the cell-permeable form of the Ca2+ chelator BAPTA AM. This is consistent with the involvement of ion channels and requirement for some Ca2+ in the release of ATP from RPE cells. This release was not affected by glibenclamide or BFA, suggesting that neither CFTR and/or vesicular release pathways were utilized. This contrasts with the ATP release activated by hypotonic challenge in these cells, which was blocked by glibenclamide, BFA and the inhibitor of CFTR gating CFTR-172 (Reigada & Mitchell, 2005a). The activation of distinct ATP release pathways by different stimuli has been described in other cells, including astrocytes (Joseph et al. 2003). While NPPB is widely recognized to inhibit Cl− channels (Cabantchik & Greger, 1992), it can also block conductance through hemichannels. The concentration of NPPB used here was ineffective at hemichannels expressed in neuroblastoma cells (Srinivas & Spray, 2003), although it did inhibit hemichannels expressed in oocytes (Eskandari et al. 2002), and embryonic chick RPE cells can release ATP through hemichannels (Pearson et al. 2005). In our preparation, the blocker oleamide interfered with the luciferase assay, while 18αGA led to a dose-dependent increase in ATP levels. Further trials are necessary to determine whether hemichannels or more traditional anion channels account for the non-CFTR release from RPE cells.

Amplification of NMDA Ca2+ signal by ATP

NMDA led to large increases in Ca2+ that were reduced in the presence of MK-801, apyrase, thapsigargin and MRS2179. This combination is consistent with a sequence whereby activation of the NMDAR leads to ATP release, which autostimulates P2Y1 receptors, leading to release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores. Since BAPTA AM prevented the release of ATP, it is tempting to speculate that NMDA itself triggers a small rise in Ca2+ that primes ATP release, although the detection of an increase in Ca2+ shortly after presentation of NMDA would strengthen this theory. In preliminary trials performed at higher sampling frequency, small, rapid increases in Ca2+ remained in the presence of apyrase (not shown), although the presence of this priming Ca2+ remains to be confirmed.

Implications for RPE–photoreceptor interactions

The ability of NMDA receptors to trigger ATP release and autostimulation of P2 receptors may play a key role in light-dependent communication between the RPE and photoreceptors. Glutamate is the predominant neurotransmitter released by the photoreceptors, with release decreased by light (Bloomfield & Dowling, 1985; Schmitz & Witkovsky, 1996). Diffusion of glutamate to the RPE could stimulate NMDA receptors, trigger autocrine activation of P2Y1 receptors by released ATP and elevate cell Ca2+. While glutamate uptake transporters on the RPE would limit the effective spread of this glutamate (Maenpaa et al. 2002, 2003, 2004), the amplification produced by ATP release and autostimulation would enable the signal to spread. This purinergic release/autostimulation could thus amplify the response to NMDA throughout the RPE monolayer, much as it conveys Ca2+ waves throughout Müller cells in the inner retina (Reifel Saltzberg et al. 2003).

The increased levels of glutamate during the dark could lead to enhanced ATP signalling and increased intracellular Ca2+ levels. Since increased Ca2+ activates basolateral Cl− conductances of the RPE and consequently the movement of fluid from the subretinal space to the choroid (Edelman & Miller, 1991; Joseph & Miller, 1992), these glutaminergic–purinergic interactions could contribute to the relative dehydration of the subretinal space during the dark (Huang & Karwoski, 1992). This release of ATP by glutamate is at odds with the hypothesis that ATP is the light peak substance. While the physiological changes to the RPE produced by ATP are similar to those triggered by light (Gallemore et al. 1988, 1993; Gallemore & Steinberg, 1993; Peterson et al. 1997), the autocrine stimulation of RPE cells by locally released ATP is activated by multiple compounds (Mitchell, 2001; Reigada et al. 2005) including glutamate. This suggests that ATP functions more as an extracellular second messenger to amplify the signal of many transmitters, possibly including the light peak substance. Whether the enhancement of outer segment phagocytosis by glutamate (Greenberger & Besharse, 1985) is related to the formation of adenosine following ATP release remains to be seen (Reigada et al. 2006b).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Richard Stone, Alan Laties and Mortimer Civan for useful discussions. This work was supported by NIH NEI grants EY013434 and EY015537 to C.H.M., and a Core Vision Grant EY001583 to the University of Pennsylvania.

References

- Araque A, Carmignoto G, Haydon PG. Dynamic signaling between astrocytes and neurons. Ann Rev Physiol. 2001;63:795–813. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron BM, Harrison BL, Miller FP, McDonald IA, Salituro FG, Schmidt CJ, Sorensen SM, White HS, Palfreyman MG. Activity of 5,7-dichlorokynurenic acid, a potent antagonist at the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor-associated glycine binding site. Mol Pharmacol. 1990;38:554–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield SA, Dowling JE. Roles of aspartate and glutamate in synaptic transmission in rabbit retina. I. Outer plexiform layer. J Neurophysiol. 1985;53:699–713. doi: 10.1152/jn.1985.53.3.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabantchik ZI, Greger R. Chemical probes for anion transporters of mammalian cell membranes. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:C803–C827. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.262.4.C803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chader GJ, Pepperberg DR, Crouch R, Wiggert B. Retinoids and the retinal pigment epithelium. In: Marmor M, Wolfensberger T, editors. The Retinal Pigment Epithelium: Function and Disease. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. pp. 135–151. [Google Scholar]

- Copenhagen DR. Synaptic transmission in the retina. Curr Op Neurobiol. 1991;1:258–262. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(91)90087-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danysz W, Parsons CG, Karcz-Kubicha M, Schwaier A, Popik P, Wedzony K, Lazarewicz J, Quack G. GlycineB antagonists as potential therapeutic agents. Previous hopes and present reality. Amino Acids. 1998;14:235–239. doi: 10.1007/BF01345268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis S, Butcher SP, Morris RG. The NMDA receptor antagonist d-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoate (d-AP5) impairs spatial learning and LTP in vivo at intracerebral concentrations comparable to those that block LTP in vitro. J Neurosci. 1992;12:21–34. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-01-00021.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn K, Marmorstein A, Bonilha V, Rodriguez-Boulan E, Giordano F, Hjelmeland L. Use of the ARPE-19 cell line as a model of RPE polarity: basolateral secretion of FGF5. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:2744–2749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelman JL, Miller SS. Epinephrine stimulates fluid absorption across bovine retinal pigment epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991;32:3033–3040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskandari S, Zampighi GA, Leung DW, Wright EM, Loo DD. Inhibition of gap junction hemichannels by chloride channel blockers. J Membr Biol. 2002;185:93–102. doi: 10.1007/s00232-001-0115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fragoso G, Lopez-Colome AM. Excitatory amino acid-induced inositol phosphate formation in cultured retinal pigment epithelium. Vis Neurosci. 1999;16:263–269. doi: 10.1017/s0952523899162072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallemore RP, Griff ER, Steinberg RH. Evidence in support of a photoreceptoral origin for the ‘light-peak substance’. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1988;29:566–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallemore RP, Hernandez E, Tayyanipour R, Fujii S, Steinberg RH. Basolateral membrane Cl− and K+ conductances of the dark-adapted chick retinal pigment epithelium. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:1656–1668. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.4.1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallemore RP, Steinberg RH. Effects of dopamine on the chick retinal pigment epithelium. Membrane potentials and light-evoked responses. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990;31:67–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallemore RP, Steinberg RH. Light-evoked modulation of basolateral membrane Cl− conductance in chick retinal pigment epithelium: the light peak and fast oscillation. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:1669–1680. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.4.1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberger LM, Besharse JC. Stimulation of photoreceptor disc shedding and pigment epithelial phagocytosis by glutamate, aspartate, and other amino acids. J Comp Neurol. 1985;239:361–372. doi: 10.1002/cne.902390402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grygorczyk R, Hanrahan JW. CFTR-independent ATP release from epithelial cells triggered by mechanical stimuli. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:C1058–C1066. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.3.C1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang B, Karwoski CJ. Light-evoked expansion of subretinal space volume in the retina of the frog. J Neurosci. 1992;12:4243–4252. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-11-04243.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes BA, Miller SS, Machen TE. Effects of cyclic AMP on fluid absorption and ion transport across frog retinal pigment epithelium. Measurements in the open-circuit state. J Gen Physiol. 1984;83:875–899. doi: 10.1085/jgp.83.6.875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JW, Ascher P. Glycine potentiates the NMDA response in cultured mouse brain neurons. Nature. 1987;325:529–531. doi: 10.1038/325529a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph SM, Buchakjian MR, Dubyak GR. Colocalization of ATP release sites and ecto-ATPase activity at the extracellular surface of human astrocytes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:23331–23342. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302680200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph DP, Miller SS. Alpha-1-adrenergic modulation of K and Cl transport in bovine retinal pigment epithelium. J Gen Physiol. 1992;99:263–290. doi: 10.1085/jgp.99.2.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GE, Bodin P, De Groat WC, Burnstock G. ATP is released from guinea pig ureter epithelium on distension. Am J Physiol. 2002;282:F281–F288. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00293.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurko D, Dezso P, Boros A, Kolok S, Fodor L, Nagy J, Szombathelyi Z. Inducible expression and pharmacological characterization of recombinant rat NR1a/NR2A NMDA receptors. Neurochem Int. 2005;46:369–379. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Colome AM, Fragoso G. Glycine stimulation of glutamate binding to chick retinal pigment epithelium. Neurochem Res. 1995;20:887–894. doi: 10.1007/BF00970733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Colome AM, Salceda R, Fragoso G. Specific interaction of glutamate with membranes from cultured retinal pigment epithelium. J Neurosci Res. 1993;34:454–461. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490340410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maenpaa H, Gegelashvili G, Tahti H. Expression of glutamate transporter subtypes in cultured retinal pigment epithelial and retinoblastoma cells. Curr Eye Res. 2004;28:159–165. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.28.3.159.26244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maenpaa H, Mannerstrom M, Toimela T, Salminen L, Saransaari P, Tahti H. Glutamate uptake is inhibited by tamoxifen and toremifene in cultured retinal pigment epithelial cells. Pharmacol Toxicol. 2002;91:116–122. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2002.910305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maenpaa H, Saransaari P, Tahti H. Kinetics of inhibition of glutamate uptake by antioestrogens. Pharmacol Toxicol. 2003;93:174–179. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2003.930404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzanti M, Sul JY, Haydon PG. Glutamate on demand: astrocytes as a ready source. Neuroscientist. 2001;7:5. doi: 10.1177/107385840100700509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SS, Hughes BA, Machen TE. Fluid transport across retinal pigment epithelium is inhibited by cyclic AMP. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:2111–2115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.6.2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SS, Steinberg RH. Active transport of ions across frog retinal pigment epithelium. Exp Eye Res. 1977a;25:235–248. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(77)90090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SS, Steinberg RH. Passive ionic properties of frog retinal pigment epithelium. J Membr Biol. 1977b;36:337–372. doi: 10.1007/BF01868158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell CH. Release of ATP by a human retinal pigment epithelial cell line: potential for autocrine stimulation through subretinal space. J Physiol. 2001;534:93–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00193.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell CH, Carre DA, McGlinn AM, Stone RA, Civan MM. A release mechanism for stored ATP in ocular ciliary epithelial cells. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7174–7178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriyoshi K, Masu M, Ishii T, Shigemoto R, Mizuno N, Nakanishi S. Molecular cloning and characterization of the rat NMDA receptor. Nature. 1991;354:31–37. doi: 10.1038/354031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris RG, Anderson E, Lynch GS, Baudry M. Selective impairment of learning and blockade of long-term potentiation by an N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antagonist, AP5. Nature. 1986;319:774–776. doi: 10.1038/319774a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash MS, Flanigan T, Leslie R, Osborne NN. Serotonin-2A receptor mRNA expression in rat retinal pigment epithelial cells. Ophthal Res. 1999;31:1–4. doi: 10.1159/000055506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash MS, Osborne NN. Pharmacologic evidence for 5-HT1A receptors associated with human retinal pigment epithelial cells in culture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:510–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada SF, Nichols RA, Kreda SM, Lazarowski ER, Boucher RC. Physiological regulation of ATP release at the apical surface of human airway epithelia. J Biol Chem. 2006 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603019200. doi 10.1074/jbc.M603019200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson RA, Dale N, Llaudet E, Mobbs P. ATP released via gap junction hemichannels from the pigment epithelium regulates neural retinal progenitor proliferation. Neuron. 2005;46:731–744. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson WM, Meggyesy C, Yu K, Miller SS. Extracellular ATP activates calcium signaling, ion, and fluid transport in retinal pigment epithelium. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2324–2337. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-07-02324.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn RH, Quong JN, Miller SS. Adrenergic receptor activated ion transport in human fetal retinal pigment epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:255–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reifel Saltzberg JM, Garvey KA, Keirstead SA. Pharmacological characterization of P2Y receptor subtypes on isolated tiger salamander Müller cells. Glia. 2003;42:149–159. doi: 10.1002/glia.10198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reigada D, Lu W, Mitchell CH. Glutamate acts at NMDA receptors to trigger ATP release from the RPE. Inves Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006a;47:883. [Google Scholar]

- Reigada D, Lu W, Zhang X, Friedman C, Pendrak K, McGlinn A, Stone RA, Laties AM, Mitchell CH. Degradation of extracellular ATP by the retinal pigment epithelium. Am J Physiol. 2005;289:C617–C624. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00542.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reigada D, Mitchell C. Release of ATP from retinal pigment epithelial cells involves both CFTR and vesicular transport. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005a;288:C132–C140. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00201.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reigada D, Mitchell CH. Stimulation of ATP release from the retinal pigment epithelium by glutamate. FASEB J. 2005b;19:A1206. [Google Scholar]

- Reigada D, Zhang X, Crespo A, Nguyen J, Liu J, Pendrak K, Stone RA, Laties AM, Mitchell CH. Stimulation of an a1-adrenergic receptor downregulates ecto-5′ nucleotidase on the apical membrane of RPE cells. Purinergic Signal. 2006b doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-3980-7. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan JS, Baldridge WH, Kelly ME. Purinergic regulation of cation conductances and intracellular Ca2+ in cultured rat retinal pigment epithelial cells. J Physiol. 1999;520:745–759. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00745.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer H, Hescheler J, Wartenberg M. Mechanical strain-induced Ca2+ waves are propagated via ATP release and purinergic receptor activation. Am J Physiol. 2000;279:C295–C307. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.2.C295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz Y, Witkovsky P. Glutamate release by the intact light-responsive photoreceptor layer of the Xenopus retina. J Neurosci Meth. 1996;68:55–60. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(96)00070-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwiebert EM. Extracellular ATP-mediated propagation of Ca2+ waves. Focus on “mechanical strain-induced Ca2+ waves are propagated via ATP release and purinergic receptor activation”. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279:C281–C283. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.2.C281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivas M, Spray DC. Closure of gap junction channels by arylaminobenzoates. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:1389–1397. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.6.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan DM, Erb L, Anglade E, Weisman GA, Turner JT, Csaky KG. Identification and characterization of P2Y2 nucleotide receptors in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. J Neurosci Res. 1997;49:43–52. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4547(19970701)49:1<43::aid-jnr5>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida N, Kiuchi Y, Miyamoto K, Uchida J, Tobe T, Tomita M, Shioda S, Nakai Y, Koide R, Oguchi K. Glutamate-stimulated proliferation of rat retinal pigment epithelial cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;343:265–273. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01526-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versaux-Botteri C, Gibert JM, Nguyen-Legros J, Vernier P. Molecular identification of a dopamine D1b receptor in bovine retinal pigment epithelium. Neurosci Letts. 1997;237:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00783-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkovsky P, Schmitz Y, Akopian A, Krizaj D, Tranchina D. Gain of rod to horizontal cell synaptic transfer: relation to glutamate release and a dihydropyridine-sensitive calcium current. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7297–7306. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-19-07297.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong EH, Kemp JA, Priestley T, Knight AR, Woodruff GN, Iversen LL. The anticonvulsant MK-801 is a potent N-methyl-d-aspartate antagonist. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:7104–7108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.18.7104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young RW, Bok D. Participation of the retinal pigment epithelium in the rod outer segment renewal process. J Cell Biol. 1969;42:392–403. doi: 10.1083/jcb.42.2.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]