Abstract

The nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS) is the first site of integration for primary baroreceptor afferents, which release glutamate to excite second-order neurones through ionotropic receptors. In vitro studies indicate that glutamate may also activate metabotropic receptors (mGluRs) to modulate the excitability of NTS neurones at pre- and postsynaptic loci. We examined the functional role of metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) in modulating the baroreceptor reflex in the rat NTS. Using the working heart–brainstem preparation, the baroreflex was activated using brief pressor stimuli and the consequent cardiac (heart rate change) and non-cardiac sympathetic (T8–10 chain) baroreflex gains were obtained. Microinjections of glutamate antagonists were made bilaterally into the NTS at the site of termination of baroreceptor afferents. NTS microinjection of kynurenate (ionotropic antagonist) inhibited both the cardiac and sympathetic baroreflex gains (16 ± 5% and 59 ± 11% of control, respectively). The non-selective mGluR antagonist MCPG produced a dose-dependent inhibition of the cardiac gain (30 ± 3% of control) but not the sympathetic gain. Selective inhibitions of the cardiac gain were also seen with LY341495 and EGLU suggesting the response was mediated by group II mGluRs. This effect on cardiac gain involves attenuation of the parasympathetic baroreflex as it persists in the presence of atenolol. Prior NTS microinjection of bicuculline (GABAA antagonist) prevented the mGluR-mediated attenuation of the cardiac gain. These results are consistent with the reported presynaptic inhibition of GABAergic transmission by group II mGluRs in the NTS and constitute a plausible mechanism allowing selective feed-forward disinhibition to increase the gain of the cardiac limb of the baroreflex without changing the sympathoinhibitory component.

The arterial baroreceptor reflex is of key importance in the regulation of cardiovascular function. The first synapse of the primary baroreceptor afferents in the central nervous system is within the nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS) (Palkovits & Zaborszky, 1977; reviewed in Blessing, 1997). Several lines of evidence suggest that glutamate is the neurotransmitter released from primary baroreceptor afferents (Talman et al. 1980; Perrone, 1981), which acts through ionotropic receptors to excite the second-order baroreflex NTS neurones (Leone & Gordon, 1989; Zhang & Mifflin, 1995; Frigero et al. 2000; Seagard et al. 2000). The excitatory baroreceptor afferent information is integrated and shaped by the neurones of the NTS before relaying downstream to influence the activity of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems thereby altering heart rate and vascular resistance to buffer changes in blood pressure (Loewy, 1990; Mifflin, 2001).

A possible role for metabotropic (mGluR) rather than ionotropic glutamate receptors in integration of the baroreflex was suggested by the finding that baroreflex-like cardiovascular responses evoked by microinjection of glutamate into the NTS were not completely blocked by kynurenate (Leone & Gordon, 1989; Talman, 1989) but could be abolished when both ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate antagonists were coapplied (Foley et al. 1998). Similarly, in conscious rats, the sympathetic limb of the baroreflex was not completely blocked by the microinjection of ionotropic antagonists to the NTS (Machado, 2001).

The mGluRs are classified into three groups based on sequence homology, intracellular signalling pathways and pharmacology (reviewed in Conn & Pin, 1997; Ozawa et al. 1998; Schoepp et al. 1999). Group I receptors (mGluR1 and 5) are primarily found on cell somata and increase the excitatory response to ionotropic receptor activation via phospholipase C and intracellular calcium signalling. Groups II and III (mGluR2 and 3; and mGluR4 and 6–8, respectively) are often located presynaptically and are negatively coupled to adenylyl cyclase and thus act to inhibit transmitter release.

Microinjection of either selective or non-selective mGluR agonists into the NTS of awake and anaesthetized rats have been shown to elicit responses imitating baroreflex activation, namely decreases in heart rate, blood pressure and sympathetic nerve activity (Pawloski-Dahm & Gordon, 1992; Machado & Bonagamba, 1998; Foley et al. 1999; Viard & Sapru, 2002). However, NTS microinjections of mGluR antagonists have produced conflicting results on baseline cardiovascular variables: no effect (Foley et al. 1998, 1999; Antunes & Machado, 2003), biphasic effects (Matsumura et al. 1999; Viard & Sapru, 2002) or decreases in blood pressure, heart rate and sympathetic nerve activity (Jones et al. 1999; Viard & Sapru, 2002, 2004).

Multiple roles have been suggested for mGluRs within the NTS. Activation of type I mGluRs on unidentified NTS neurones in vitro was shown to reciprocally increase excitatory ionotropic glutamatergic transmission and decrease inhibitory GABAergic transmission at a postsynaptic locus (Glaum & Miller, 1993; Glaum et al. 1993). There is also evidence for a role of presynaptic mGluR on vagal afferents (including baroreceptors) within the NTS from both in vitro and in vivo studies where signal transmission to second-order NTS neurones was depressed in a frequency-dependent manner by endogenous glutamate acting on group II and III mGluRs (Hay & Hasser, 1998; Liu et al. 1998; Pamidimukkala & Hay, 2001; Chen et al. 2002). A different mGluR effect has been reported by Chen & Bonham (2005) from an in vitro study that showed type II mGluRs, located presynaptically on NTS GABAergic interneurones, can decrease GABA release onto second-order baroreflex neurones when activated by glutamate spill-over from the primary afferents. A fourth effect of mGluR activation (group I) in the NTS in vitro is a postsynaptic, excitatory effect, direct on second order baroreflex neurones, mediated by activation of a Na+–Ca2+ exchanger (Sekizawa & Bonham, 2006).

Given the potent cardiovascular responses seen following mGluR agonist microinjections to the NTS, and the specific actions at a cellular level seen in baroreflex circuits in vitro, it has been curious that attempts to examine the sensitivity of baroreflex evoked responses to mGluR antagonists in vivo have failed to demonstrate an effect on either heart rate (Antunes & Machado, 2003) or depressor (Viard & Sapru, 2004) components. There is therefore a degree of uncertainty over the functional role of mGluRs in the baroreflex neural circuitry within the NTS.

In this study, we have examined the effect of selective mGluR antagonists on both the sympathetic and parasympathetic components of the baroreflex in the rat working heart–brainstem preparation. We show a marked and selective inhibition of the cardiac baroreflex (as opposed to the non-cardiac sympathetic component) consequent on blockade of type II mGluRs in the NTS. This effect is mediated through alteration of GABAergic function within the NTS and provides a mechanism for feed-forward disinhibition that selectively increases the gain of the cardiac baroreflex but not non-cardiac sympathetic baroreflex. Some of these data have been presented in abstract form (Simms et al. 2005).

Methods

Working heart–brainstem preparation (WHBP)

All procedures conformed to the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 and were approved by our institutional ethical review committee. For the WHBP (see Paton, 1996), Wistar rats (65–85 g) were anaesthetized deeply until loss of paw withdrawal reflex. Animals were bisected below the diaphragm, exsanguinated, cooled in Ringer solution at 4°C, decerebrated precollicularly, and cerebellectomised to expose the floor of the fourth ventricle. Retrograde perfusion of the thorax and head was achieved via a double-lumen catheter inserted into the descending aorta. The perfusate was a modified Ringer solution (see below) containing Ficoll (1.25%) warmed to 31°C and gassed with carbogen. The second lumen of the cannula was connected to a transducer to monitor perfusion pressure in the aorta.

Recordings of phrenic nerve activity were made using a suction electrode. The flow rate through the preparation was increased until a perfusion pressure of between 60 and 90 mmHg was reached and an augmenting (i.e. eupnoeic) pattern of phrenic motor activity was obtained. Neuromuscular blockade was established using vecuronium bromide added to the perfusate (2–4 μg ml−1, Organon Teknica, Cambridge, UK). The sympathetic chain was identified between T8 and T10, a section was cut and the proximal end recorded using a bipolar suction electrode, then band-pass filtered (60–2000 Hz). The electrocardiogram (ECG) was recorded simultaneously through the phrenic nerve suction electrode. Instantaneous heart rate was calculated using a window discriminator to trigger from the R-wave of the ECG. Data were acquired using an A-D converter (CED micro1401) to a computer, displayed and analysed using custom-written scripts in Spike2 (CED, Cambridge, UK).

Cardiorespiratory reflex measurements

Baroreceptor reflex

The flow rate of the peristaltic pump (505U, Watson Marlow Bredel, Falmouth, UK) was computer controlled from a custom written Spike2 script. This allowed considerable flexibility in generating flow changes in the preparation and enabled consistency in repetitive changes in perfusion pressure of precise duration and amplitude. The baroreflex function curve was examined using sequential flow pulses of 1 s duration to produce changes in pressure of between 10 and 50 mmHg. Subsequent pulses within the linear part of the baroreflex function curve were used to examine the effect of microinjections into the NTS (Paton & Kasparov, 1999; Boscan et al. 2002; Pickering et al. 2003). The cardiac and non-cardiac sympathetic components of the baroreflex were quantified thus: cardiac gain as Δ heart rate/Δ pressure (bpm mmHg−1) and the sympathetic gain as percentage inhibition/Δ pressure (% mmHg−1). Sympathoinhibition was determined by ratioing the average integrated sympathetic nerve activity (time constant of 200 ms) during the pressure pulse against the averaged activity from two preceding time periods, at equivalent stages of the respiratory cycle, using a custom written Spike2 script (see Pickering et al. 2003 for details). This approach takes account of the ongoing respiratory fluctuation in the sympathetic nerve activity.

Chemoreceptor reflex

Peripheral chemoreceptors were stimulated using sodium cyanide (CN; 0.01% solution; 100 μl) bolus into the aorta. This dose produced a submaximal bradycardia (Paton & Kasparov, 1999). The peripheral chemoreceptor reflex consisted of an increase in central respiratory drive accompanied by a bradycardia and an increase in sympathetic nerve activity. The chemoreflex was quantified in three ways: peak bradycardia – the lowest heart rate during the response; phrenic nerve frequency – the cycle period of consecutive phrenic bursts; and the increase in sympathetic nerve activity during the peak of the chemoreflex response as compared to two equivalent control periods.

NTS microinjection studies

In the WHBP the surface landmarks of the dorsal medulla are seen clearly as the preparation is cerebellectomised. Calamus scriptorius was used as a landmark to direct micropipettes into sites known to contain baroreceptive neurones in the rat (Chan et al. 2000; Deuchars et al. 2000). A three-barrelled micropipette (external tip diameter between 10 and 30 μm) was placed into the NTS using a micromanipulator. The microinjection volume (60 nl) was determined by viewing the movement of the meniscus through a binocular microscope fitted with a calibrated eyepiece graticule. Drugs were microinjected bilaterally into the NTS at 400–600 μm deep from the dorsal medullary surface and 100 μm rostral to calamus scriptorius, 300–400 μm lateral to the midline. All injections were made within a period of 60 s and the baroreflex was tested 30 s after the last injection and then examined repeatedly every 3 min for at least 15 min. For the MCPG dose–response study each preparation typically received three doses of MCPG bilaterally (in increasing order) with recovery of the baroreflex being obtained before the subsequent dose of antagonist. Control microinjection experiments with NaCl (0.9%; 60 nl) in the same NTS sites did not alter baseline heart rate, perfusion pressure, phrenic nerve activity or either of the reflexes tested.

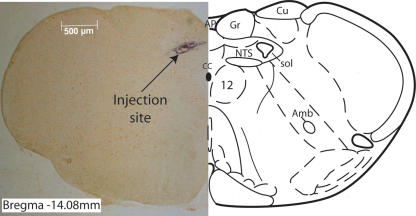

Functional identification of microinjection site

Initial microinjection studies were carried out with the GABAA agonist isoguvacine to map the area of the NTS from which both baroreflex sympathoinhibition and bradycardia could be reversibly inhibited (Boscan & Paton, 2001; Pickering et al. 2003) without significant effect on the chemoreflex. At approximately 300 μm lateral and 100 μm rostral to calamus scriptorius and 500–600 μm deep to the dorsal surface (see Fig. 1), bilateral injection of isoguvacine (60 nl of 1 mm, 60 pmol) significantly inhibited both the baroreflex cardiac and sympathetic gains to 30 ± 9% and 47 ± 6% of control, respectively (n = 4, P < 0.05). The chemoreceptor reflex was not significantly affected by isoguvacine microinjection at this same site (phrenic nerve frequency was 89 ± 18%, peak bradycardia 83 ± 12%, and sympathetic activity 106 ± 6% of control, n = 4, NS). Thus, this site within the NTS was identified as giving access to circuits mediating both the sympathetic and parasympathetic outflows specific to the baroreflex. Microinjections were made bilaterally at this site in all subsequent experiments. The location of the injection site was marked with pontamine sky blue (1 μl at the end of the experiment. The brainstem was fixed in 4% formaldehyde and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose overnight, and the medulla was sliced, on a freezing microtome, into 40 μm sections that were mounted in series for microscope examination.

Figure 1. Injection site in the NTS.

Photomicrograph of a histological section from a representative experiment in which bilateral NTS microinjection (100 μm rostral to calamus scriptorius, 300 μm lateral to the midline and 550 μm deep to the dorsal surface) of isoguvacine (60 pmol) inhibited both baroreflex sympathoinhibition and bradycardia without significant effect on the chemoreflex. Subsequent unilateral injection of pontamine sky blue (1 μl) was used to mark the injection site as being within the dorsomedial NTS. The overlaid line drawing (right) shows the nuclear boundaries at this level of the medulla (bregma −14.08 mm; from Paxinos & Watson, 1986). Abbreviations: CC, central canal; NTS, nucleus tractus solitarii; sol, solitary tract; Cu and Gr, cuneate and gracile nuclei; amb, nucleus ambiguus; 12, hypoglossal nucleus; AP, area postrema.

Analysis

All data are expressed as means ± s.e.m. unless otherwise stated. Statistical significance was tested using Student's t test (paired or unpaired as appropriate) with a threshold of P < 0.05.

Materials

The Ringer solution used contained the following (mm): 125 NaCl, 24 NaHCO3, 5 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.25 MgSO4 and 1.25 KH2PO4, 10 dextrose, pH 7.3 after carbogenation. Ficoll 70 (1.25%) was added to the perfusion solution. The following drug concentrations were used in microinjection experiments: isoguvacine (1 mm), bicuculline (5–25 μμ), kynurenic acid (10 mm), α-methyl-4-carboxyphenylglycine (MCPG, 0.5–50 mm), (2S)-2-amino-2-[(1S,2S)-2-carboxycycloprop-1-yl]-3-(xanth-9-yl)propanoic acid (LY341495, 10–500 μμ), α-ethylglutamic acid (EGLU, 0.2–1 mm), 1-amino-indan-1,5-dicarboxylic acid (AIDA, 20 mm), and pontamine sky blue to mark the site of injection. The doses of bicuculline (10 μμ), LY341495 (100 μμ) and EGLU (1 mm) used in the results section were established after preliminary dose finding experiments. The dose of AIDA was based on the data from a previous NTS microinjection study (Matsumura et al. 1999). Methylatropine and atenolol were added to the perfusate to block cardiac muscarinic and β-adrenoceptors, respectively. All drugs were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Gillingham, UK) except MCPG, LY341495, EGLU and AIDA, which were obtained from Tocris (Bristol, UK).

Results

All experiments were performed using the working heart–brainstem preparation (WHBP; n = 34).

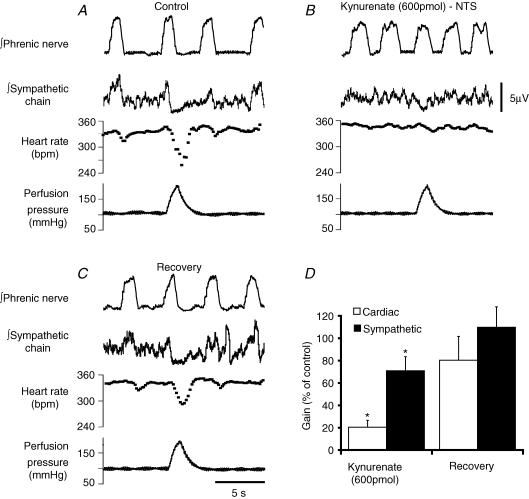

Role of NTS ionotropic glutamate receptors in the baroreflex

Ionotropic glutamate antagonists have previously been shown to attenuate both the sympathetic and cardiac baroreflex limbs when injected into the NTS (Guyenet et al. 1987; Talman, 1989; Machado, 2001). Therefore, to validate the location of our NTS injection site we undertook bilateral microinjection studies with the non-selective, ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonist kynurenate (600 pmol, Fig. 2). These injections produced a significant, reversible inhibition of both the baroreflex bradycardia (cardiac gain to 16 ± 5% of control, P < 0.05) and sympathoinhibition (59 ± 10% of control, P < 0.05). The microinjection of kynurenate did not change baseline perfusion pressure, 86 ± 2 mmHg to 90 ± 3 mmHg (n = 6, P > 0.05), but the heart rate was slightly increased from 342 ± 7 to 352 ± 4 bpm (n = 6, P < 0.05) and there was an increase in respiratory frequency (98% ± 34, P < 0.05, n = 4) but no change in phrenic burst amplitude.

Figure 2. Blockade of ionotropic glutamate transmission in the NTS inhibits baroreflex-mediated sympathoinhibition and bradycardia.

A, control baroreflex response with bradycardia and sympathoinhibition evoked by the increase in perfusion pressure. B, bilateral microinjection of kynurenate (600 pmol) into the NTS inhibits both the baroreflex bradycardia (to 19% of control) and sympathoinhibition (to 52% of control). C, the baroreflex responses recover after 15 min. D, group data showing that both the cardiac baroreflex gain and the sympathetic baroreflex gain (both normalized to control) were significantly attenuated by kynurenate (Student's t test, *P < 0.05, n = 6).

Because of the finding that this region of the NTS has a role in both the bradycardic and sympathoinhibitory components of the baroreflex, all subsequent microinjection experiments using mGluR antagonists were aimed at this same region and histologically confirmed subsequently.

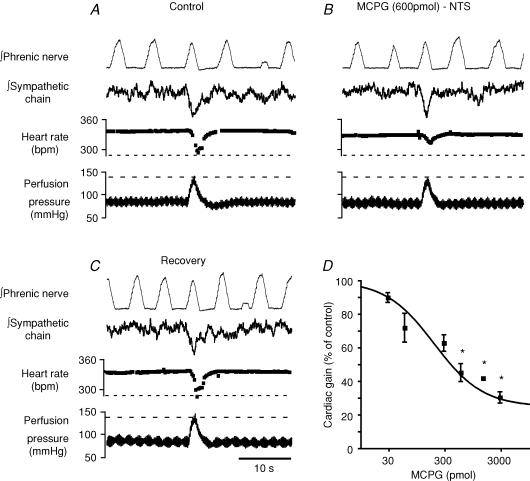

Role of NTS mGluRs in the baro- and peripheral chemoreceptor reflexes

To investigate a role of mGluRs in the baroreflex arc within the NTS, we initiated our enquiry by using a non-selective antagonist – MCPG. Bilateral microinjection of MCPG into the NTS attenuated the cardiac baroreflex (Fig. 3B), an action that reversed over 20–40 min (Fig. 3C). Dose–response studies were undertaken to examine this effect of MCPG (30 pmol to 3 nmol, Fig. 3D). From this range the 600 pmol dose was chosen for more detailed studies of effect as it was close to the IC50 and this inhibition was reversed within 20 min. MCPG at this dose inhibited the cardiac baroreflex to 48 ± 6% of control, from −1.15 ± 0.2 to −0.58 ± 0.1 bpm mmHg−1 (n = 5, P < 0.01). The sympathetic gain after MCPG (600 pmol) showed little change from −1.05 ± 0.1 to −0.86 ± 0.2% mmHg−1 (Figs 3 and 4A, n = 5, NS). The chemoreceptor reflex was not significantly affected by MCPG microinjection (600 pmol), and peak bradycardia was 98 ± 26%, phrenic nerve frequency 83 ± 17% and sympathetic activity 78 ± 16% of control, respectively (n = 4, NS). Baseline perfusion pressure and heart rate were not altered by MCPG (600 pmol); values were 84 ± 2 mmHg and 85 ± 2 mmHg; 345 ± 6 bpm and 354 ± 7 bpm before and after, respectively (n = 5, NS). MCPG caused a modest increase in respiratory frequency (33 ± 6%, P < 0.01, n = 4) without a significant change in phrenic burst amplitude.

Figure 3. The baroreflex bradycardia is selectively inhibited by mGluR antagonist.

A, control baroreflex bradycardia and sympathoinhibition evoked by an increase in perfusion pressure. B, bilateral NTS microinjection of the non-selective mGluR antagonist MCPG (600 pmol) inhibits the baroreflex bradycardia but not the baroreflex sympathoinhibition. C, the effect is reversible after 20 min. D, log dose–response relationship for MCPG (30 pmol to 3 nmol) inhibition of the baroreflex bradycardia (*P < 0.01 compared to control, Student's paired t test, n = 7).

Figure 4. Broad-spectrum and group II selective mGluR antagonists inhibit the cardiac baroreflex.

Pooled data showing the inhibitory effect of MCPG (non-selective mGluR antagonist, 600 pmol, n = 5) (A) and LY341495 (Group II selective mGluR antagonist, 6 pmol, n = 7) (B) on the cardiac baroreflex gain but not the sympathetic baroreflex gain (normalized to control, *P < 0.05, Student's t test).

mGluR antagonism affects the cardiac vagal baroreflex

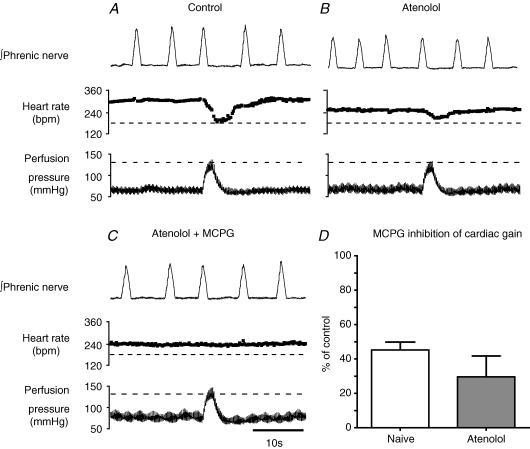

We observed a selective inhibition of the cardiac over the sympathetic non-cardiac limb of the baroreflex by the non-selective mGluR antagonist. The cardiac baroreflex is composed of both parasympathetic and sympathetic components. Therefore, to determine whether mGluRs are selectively influencing the cardiac parasympathetic limb of the baroreflex we added a β-blocker (atenolol, 5–10 μg ml−1) to the perfusate to attenuate the sympathetic drive to the heart. This caused the baseline heart rate to fall by 80 ± 8 bpm and reduced the baroreflex cardiac gain to 40 ± 8% of control (this fall in gain appeared secondary to the fall in baseline heart rate, as the absolute degree of heart rate slowing on baroreflex activation was largely unchanged by atenolol). The injection of MCPG (600 pmol) to the NTS further inhibited the cardiac gain to 30 ± 12% of that seen with atenolol alone (n = 3, P < 0.01, Fig. 5).

Figure 5. MCPG in the NTS attenuates the cardiac baroreflex by an action on the parasympathetic outflow.

The sympathetic contribution to the cardiac baroreflex was blocked by the addition of a β-adrenoceptor antagonist to the perfusate (atenolol, 5 μg ml−1). A, control baroreflex bradycardia. B, 10 min after the addition of atenolol when a stable, slower heart rate was achieved, activation of the baroreflex produced a smaller bradycardia (largely because of the fall in baseline heart rate). This bradycardia is mediated through the parasympathetic limb of the cardiac baroreflex. C, NTS microinjection of MCPG (600 pmol) abolished this vagal baroreflex bradycardia indicating an effect on the parasympathetic limb of the reflex. D, pooled data from naive WHBP (n = 7) and preparations β-blocked with atenolol (n = 3) showing the reduction in cardiac baroreflex gain after the NTS microinjection of MCPG (600 pmol, data expressed as percentage of control). There was no significant difference in the effect of MCPG on the baroreflex gain between the naive and atenolol-treated groups.

In a second set of experiments a muscarinic antagonist (methylatropine, 25–50 ng ml−1) was added to the perfusate to block the parasympathetic influence on the heart (assayed against the peripheral chemoreflex bradycardia). The addition of methylatropine produced an increase in heart rate from 341 ± 31 to 401 ± 22 bpm (n = 4, P < 0.05) and completely blocked the peripheral chemoreflex bradycardia. The baroreflex bradycardia was also abolished in the presence of methylatropine (n = 3) suggesting that in the WHBP the heart rate response to our perfusion pressure ramps is mediated predominantly by the vagus nerve (as has been reported for the baroreflex bradycardia elicited in conscious rats in response to the pressor effect of phenylephrine; Stornetta et al. 1987). Therefore, the attenuation of the cardiac baroreflex by MCPG appears to be largely due to an inhibition of the parasympathetic component.

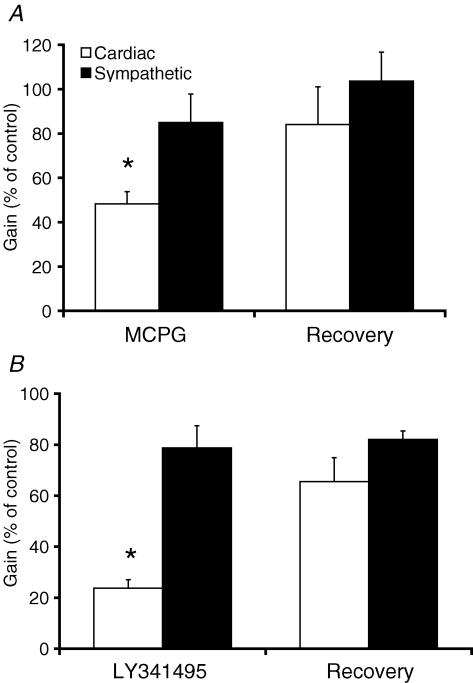

Identity of the NTS mGluR subtype responsible for attenuating the cardiac baroreflex

Bilateral NTS microinjection of the group II selective mGluR antagonist LY341495 (6 pmol) produced a significant reversible inhibition of the cardiac baroreflex gain to 24 ± 3% of control (n = 7, P < 0.05) but did not significantly change the sympathetic gain (79 ± 9% of control after LY341495; Fig. 4B, n = 7, NS). Although LY341495 has some antagonist activity at group III mGluRs, it is between 100 and 1000 times more potent at mGlu2 and 3 (group II) (Kingston et al. 1998). The selective group II mGluR antagonist EGLU (60 pmol) produced similar results; cardiac gain was inhibited to 33 ± 7% (n = 4, P < 0.05) and the sympathetic gain was unchanged at 96 ± 4% (n = 5, NS). In contrast, the selective group I mGluR antagonist AIDA (1.2 nmol) produced no significant changes in the cardiac baroreflex gain (89 ± 6% of control, P > 0.05, n = 4) or baseline cardiovascular variables. None of these selective mGluR antagonists had any significant effect on the response to activation of the peripheral chemoreflex (data not shown). Thus, it appears that a group II mGluR is involved in selective facilitation of the cardiac baroreflex within the NTS.

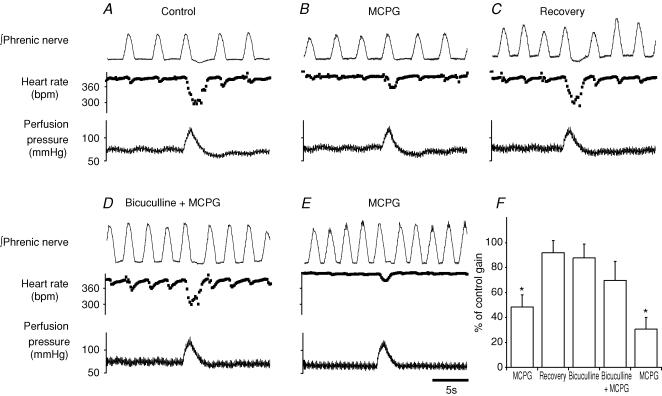

Mechanism of action of the mGluR

The type II mGluR receptors are characteristically inhibitory often at a presynaptic site (Conn & Pin, 1997). With this in mind, our data cannot be explained by this inhibitory mGluR being located either presynaptically on baroreflex primary afferent terminals or postsynaptically on second order neurones. Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that these receptors may be located on an inhibitory GABAergic local circuit interneurone, as has been suggested previously (Chen & Bonham, 2005). In order to test this possibility, NTS microinjection studies were carried out using a relatively low dose of the GABAA antagonist bicuculline (10 μm, 60 nl, 0.6 pmol) in combination with an mGluR II antagonist. We have previously shown that NTS microinjection of this concentration of bicuculline does not alter baseline heart rate, perfusion pressure, respiratory rate or the cardiac baroreflex gain but can block the inhibitory effect of substance P applied locally to baroreceptive neurones in NTS (Boscan et al. 2002). This was confirmed in our preliminary dose finding studies where NTS microinjection of bicuculline (0.6 pmol, n = 3) was without significant effect on perfusion pressure (68 ± 3 vs. 69 ± 5 mmHg), heart rate (309 ± 18 vs. 305 ± 18 bpm), respiratory frequency (12 ± 2 vs. 12.3 ± 1.8Hz) or cardiac baroreflex gain (1.73 vs. 1.65 bpm mmHg−1, 91 ± 7% of control).

The test protocol involved the sequential microinjection and recovery from an mGluR antagonist, bicuculline (0.6 pmol) followed by mGluR antagonist, then mGluR antagonist alone. After each microinjection (including bicuculline) the cardiac baroreflex gain was measured. These studies used either MCPG (600 pmol, n = 3) or LY341495 (6 pmol, n = 3) as the mGluR antagonist to cause a reversible inhibition of the cardiac baroreflex gain (Fig. 6A–C). After the cardiac gain returned to control, low dose bicuculline (0.6 pmol) was microinjected (without effect on the baroreflex gain) followed (120 s later) by the mGluR antagonist (Fig. 6D). The cardiac gain was inhibited to 39 ± 9% (n = 6, P < 0.01) of control by the mGluR antagonist injected alone compared to 84 ± 13% (NS) when injected after bicuculline. Following washout of bicuculline (10–20 min), the mGluR antagonist was once again able to significantly inhibit the cardiac gain to 32 ± 8% of control (n = 6, P < 0.01, Fig. 6E and F). By contrast a similar volume control protocol where 0.9% NaCl was substituted for bicuculline did not alter the baroreflex gain (101 ± 10% of control, P > 0.05, n = 4, see supplemental Fig. 1) and did not affect the degree of attenuation of the baroreflex gain by MCPG (35 ± 7% of control, P < 0.05, n = 4).

Figure 6. Inhibitory action of MCPG on the cardiac baroreflex requires GABAA receptors in the NTS.

A, control baroreflex bradycardia. B, microinjection of MCPG (600 pmol) to the NTS inhibits the baroreflex bradycardia. C, recovery to control (20 min). D, subsequent microinjection of the GABAA antagonist bicuculline (0.6 pmol) followed by MCPG (600 pmol) prevented the attenuation of the cardiac baroreflex. E, after washout of bicuculline (20 min) a repeat application of MCPG again attenuates the baroreflex bradycardia. F, group data showing the initial significant reversible inhibition of the baroreflex by MCPG. There is no significant attenuation of the cardiac gain by bicuculline nor by the subsequent injection of MCPG. After washout of bicuculline, MCPG once again attenuates the bradycardia (n = 3, *P < 0.01, Student's t test).

Discussion

We describe in this study a new and selective functional role for group II mGluRs at the level of the NTS in the modulation of the cardiac vagal baroreflex. The microinjection of both non-selective (MCPG) and group II selective (EGLU and LY341495) mGluR antagonists into the NTS reduced the gain of the cardiac (but not the non-cardiac sympathetic) baroreflex, and the effect persisted in the presence of cardiac β-adrenoceptor blockade indicating an action on the cardiac parasympathetic limb. The effect of mGluR antagonists on the cardiac baroreflex was prevented by the prior microinjection of a GABAA antagonist (bicuculline) indicating that the effect was mediated through GABAA receptors.

Our observations are consistent with a mechanism proposed from the in vitro observations of Chen & Bonham (2005) who showed an inhibitory effect of group II mGluRs on GABAergic synaptic currents in second order baroreflex neurones. It has been proposed that these GABAergic interneurones are located at a key strategic location close to the first afferent synapse of the baroreflex (Maqbool et al. 1991; Chen & Bonham, 2005). GABAergic NTS interneurones have been shown to play an important role in cardiovascular reflexes including the baroreceptor reflex (Mifflin & Felder, 1988; Sved, 1994; Paton et al. 2001). The mGluR-mediated reduction in GABAergic inhibition, possibly due to ‘spillover’ of glutamate from primary afferents (as inferred by Chen & Bonham, 2005), will cause disinhibition of the second order baroreflex neurones to facilitate the onward transmission of the afferent signal. This would be expected to increase the gain of the baroreflex, as we show for the cardiac baroreflex in this study.

There is evidence that the NTS contains all of the known subtypes of mGluR (Hay et al. 1999; Hoang & Hay, 2001) with some differences in the subnuclear regional distributions. Based on the antagonist sensitivity of our response (sensitive to LY341495 and EGLU but not AIDA), we can eliminate group I mGluRs as candidates for mediating the response. Although LY341495 has some antagonist activity at group III mGluRs, it is between 100 and 1000 times more potent at group II (Kingston et al. 1998). The relatively low dose of LY341495 required for full effect and the equivalence of EGLU (selective for group II) suggest that this is a group II mGluR mediated response.

Several different mGluR responses have been observed at a cellular level in putative baroreflex circuits from in vitro studies of the NTS. (1) Group I – a direct postsynaptic excitatory effect on second order baroreflex neurones mediated by activation of a Na+–Ca2+ exchanger (Sekizawa & Bonham, 2006) and also a postsynaptic inhibition of GABAergic currents in functionally unidentified NTS neurones (Glaum & Miller, 1993; Glaum et al. 1993). (2) Group II – presynaptic inhibition of GABA release from NTS interneurones (Chen & Bonham, 2005). (3) Group II/III – presynaptic inhibition of glutamate release and vesicle turnover from primary afferents (Hay & Hasser, 1998; Pamidimukkala & Hay, 2001; Chen et al. 2002).

Of these different proposed mGluR effects, we could only find evidence for the presynaptic inhibition of GABA release (Chen & Bonham, 2005) that affected the baroreflex in our functionally intact in situ preparation. Using AIDA, a group I selective antagonist, at a dose that has been reported to affect blood pressure in vivo when microinjected to the NTS (Matsumura et al. 1999), we found no evidence of a decrease baroreflex gain that would be predicted from a blockade of a postsynaptic group I excitatory response (Glaum & Miller, 1993; Glaum et al. 1993; Sekizawa & Bonham, 2006). We also saw no evidence for an increase in baroreflex gain from blockade of group III (along with group I/II) mGluRs with MCPG nor with the group II selective antagonists as would be predicted for a block of presynaptic inhibition of glutamate release (Hay & Hasser, 1998; Pamidimukkala & Hay, 2001; Chen et al. 2002).

Our findings are apparently different from two previous in vivo studies that have failed to show an effect of mGluR antagonists on baroreflex-evoked responses (Antunes & Machado, 2003; Viard & Sapru, 2004). Our data are actually consistent with those of Viard & Sapru (2004) who showed no effect on carotid baroreflex depressor responses (heart rate responses were not examined), as such responses are mediated largely by baroreflex sympathoinhibition, which we show here to be unaffected by mGluR antagonism. However, our effects on the cardiac component of the baroreflex contrast with those of Antunes & Machado (2003) who were unable to show any effect of MCPG on phenylephrine-induced heart rate changes in conscious rats. This may relate to the type of stimulus used to trigger the baroreflex response and the consequent intensity of baroreceptor afferent activation. With the injection of phenylephrine the pressure change is relatively more gradual compared to our rapid perfusion pressure ramps and hence may be expected to produce less baroafferent activation. If the mGluR activation is dependent upon glutamate spillover then it may require strong baroreceptor afferent drive to be activated. The generation of this strong baroafferent drive may have been facilitated by the use of the WHBP; this allows flexible control of perfusion pressure through the computer-controlled pump (see Pickering & Paton, 2006) in an un-anaesthetized preparation with good access to the NTS for drug administration and washout.

The mGluR has been shown to be involved in feed-forward inhibition of GABA release in other brain regions such as the cerebellum (Mitchell & Silver, 2000) and the hippocampus (Semyanov & Kullmann, 2000) as well as in second order NTS neurones (either unidentified (Jin et al. 2004) or putative barosensitive (Chen & Bonham, 2005)). In the cerebellum, the activation of mGluRs by glutamate spillover follows high frequency afferent barrage (50% effect at 100 Hz). A similar effect is seen in the NTS second order neurones with burst stimulation at 50 Hz that decreases the frequency of spontaneous GABAergic events (Jin et al. 2004). This frequency of afferent discharge may be attained by myelinated baroafferents during a strong pressor response (Thoren & Jones, 1977; Thoren et al. 1999).

The observed selective modulation of the cardiac component of the baroreflex appears to be mediated by an effect on the parasympathetic limb within the NTS. This conclusion is based on the observation that the component remaining after β-adrenoceptor blockade is sensitive to the same degree to mGluR antagonism. Although this action would appear sufficient to account for our response, we cannot exclude an effect of the mGluR antagonist on the cardiac sympathetic as the baroreflex bradycardia was completely blocked in the presence of a muscarinic antagonist, preventing the assessment of the effect of the mGluR antagonists on the sympathetic supply to the heart. We have previously described a differential effect on the sympathetic versus parasympathetic limb of the baroreflex with substance P (Pickering et al. 2003) that acted to decrease the cardiac baroreflex gain by activation of a population of GABAergic interneurones that selectively influence the parasympathetic limb of the baroreflex. It is possible that the activation of the group II mGluR inhibits just such a population of GABAergic interneurones, hence causing the selective facilitation of the cardiac baroreflex gain.

We have found no evidence for tonic activation of the group II mGluR as antagonism failed to change any of the baseline cardiovascular variables in the WHBP, suggesting that it may not play a role in determining either the blood pressure or heart rate set-points. This is broadly in keeping with the findings of other in vivo studies where non-selective and group II selective mGluR antagonists have produced inconsistent responses (Foley et al. 1998, 1999; Matsumura et al. 1999; Antunes & Machado, 2003). We would therefore propose that the functional role of this system may be to provide a means to increase the cardiac gain in response to strong baroafferent stimulation; this would provide a stimulus-intensity-dependent mechanism to amplify the bradycardia to reduce cardiac output and thus compensate for any large, abrupt rise in blood pressure. The apparent restriction of this effect to the vagal side of the baroreflex makes sense since it can act quickly to compensate for abrupt pressure transients, unlike the effect of sympathetic withdrawal. As such, we believe that this describes a novel endogenous, positive feed-forward mechanism by which the cardiac baroreflex gain can be increased at the level of the NTS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

A.E.S. is in receipt of the British Heart Foundation W E Parkes Fellowship. A.E.P. is a Wellcome Trust Advanced Fellow. JFRP holds a Royal Society Wolfson Merit Research Award. We are grateful to Ana Paula Abdala, Vagner Antunes and Pedro Boscan for their technical advice and assistance.

References

- Antunes VR, Machado BH. Antagonism of glutamatergic metabotropic receptors in the NTS of awake rats does not affect the gain of the baroreflex. Auton Neurosci. 2003;103:65–71. doi: 10.1016/s1566-0702(02)00234-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blessing W. The Lower Brainstem and Bodily Homeostasis. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Boscan P, Kasparov S, Paton JF. Somatic nociception activates NK1 receptors in the nucleus tractus solitarii to attenuate the baroreceptor cardiac reflex. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:907–920. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boscan P, Paton JF. Role of the solitary tract nucleus in mediating nociceptive evoked cardiorespiratory responses. Auton Neurosci. 2001;86:170–182. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0702(00)00255-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan R, Peto C, Sawchenko P. Fine structure and plasticity of barosensitive neurons in the nucleus of solitary tract. J Comp Neurol. 2000;422:338–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C-Y, Bonham AC. Glutamate suppresses GABA release via presynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors at baroreceptor neurones in rats. J Physiol. 2005;562:535–551. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.076885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C-Y, Ling E-H, Horowitz JM, Bonham AC. Synaptic transmission in nucleus tractus solitarius is depressed by Group II and III but not Group I presynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors in rats. J Physiol. 2002;538:773–786. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.012948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn PJ, Pin JP. Pharmacology and functions of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1997;37:205–237. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuchars J, Li YW, Kasparov S, Paton JFR. Morphological and electrophysiological properties of neurones in the dorsal vagal complex of the rat activated by arterial baroreceptors. J Comparative Neurol. 2000;417:233–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley CM, Moffitt JA, Hay M, Hasser EM. Glutamate in the nucleus of the solitary tract activates both ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptors. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1998;275:R1858–R1866. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.6.R1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley CM, Vogl HW, Mueller PJ, Hay M, Hasser EM. Cardiovascular response to group I metabotropic glutamate receptor activation in NTS. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1999;276:R1469–R1478. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.5.R1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frigero M, Bonagamba LG, Machado BH. The gain of the baroreflex bradycardia is reduced by microinjection of NMDA receptor antagonists into the nucleus tractus solitarii of awake rats. J Auton Nerv Syst. 2000;79:28–33. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1838(99)00089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaum SR, Miller RJ. Activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors produces reciprocal regulation of ionotropic glutamate and GABA responses in the nucleus of the tractus solitarius of the rat. J Neurosci. 1993;13:1636–1641. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-04-01636.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaum SR, Sunter DC, Udvarhelyi PM, Watkins JC, Miller RJ. The actions of phenylglycine derived metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonists on multiple (1S,3R)-ACPD responses in the rat nucleus of the tractus solitarius. Neuropharmacology. 1993;32:1419–1425. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(93)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyenet PG, Filtz TM, Donaldson SR. Role of excitatory amino acids in rat vagal and sympathetic baroreflexes. Brain Res. 1987;407:272–284. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91105-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay M, Hasser EM. Measurement of synaptic vesicle exocytosis in aortic baroreceptor neurons. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:H710–H716. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.2.H710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay M, McKenzie H, Lindsley K, Dietz N, Bradley SR, Conn PJ, Hasser EM. Heterogeneity of metabotropic glutamate receptors in autonomic cell groups of the medulla oblongata of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1999;403:486–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang CJ, Hay M. Expression of metabotropic glutamate receptors in nodose ganglia and the nucleus of the solitary tract. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H457–H462. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.1.H457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin YH, Bailey TW, Andresen MC. Cranial afferent glutamate heterosynaptically modulates GABA release onto second-order neurons via distinctly segregated metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9332–9340. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1991-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones NM, Beart PM, Monn JA, Widdop RE. Type I and II metabotropic glutamate receptors mediate depressor and bradycardic actions in the nucleus of the solitary tract of anaesthetized rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;380:129–135. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00518-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingston AE, Ornstein PL, Wright RA, Johnson BG, Mayne NG, Burnett JP, Belagaje R, Wu S, Schoepp DD. LY341495 is a nanomolar potent and selective antagonist of group II metabotropic glutamate receptors. Neuropharmacology. 1998;37:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00191-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone C, Gordon F. Is l-glutamate a neurotransmitter of baroreceptor information in the nucleus of the tractus solitarius? J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1989;250:953–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Chen CY, Bonham AC. Metabotropic glutamate receptors depress vagal and aortic baroreceptor signal transmission in the NTS. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1998;275:H1682–H1694. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.5.H1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewy AD. Central Autonomic Pathways. In: Loewy AD, Spyer KM, editors. Central Regulation of Autonomic Functions. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990. pp. 88–103. [Google Scholar]

- Machado BH. Neurotransmission of the cardiovascular reflexes in the nucleus tractus solitarii of awake rats. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;940:179–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado BH, Bonagamba LG. Cardiovascular responses to microinjection of trans-(±)-ACPD into the NTS were similar in conscious and chloralose-anesthetized rats. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1998;31:573–579. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x1998000400016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maqbool A, Batten TF, McWilliam PN. Ultrastructural relationships between GABAergic terminals and cardiac vagal preganglionic motoneurons and vagal afferents in the cat: a combined HRP tracing and immunogold labelling study. Eur J Neurosci. 1991;3:501–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1991.tb00837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura K, Tsuchihashi T, Kagiyama S, Abe I, Fujishima M. Subtypes of metabotropic glutamate receptors in the nucleus of the solitary tract of rats. Brain Res. 1999;842:461–468. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01889-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mifflin SW. What does the brain know about blood pressure? News Physiol Sci. 2001;16:266–271. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.2001.16.6.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mifflin SW, Felder RB. An intracellular study of time-dependent cardiovascular afferent interactions in nucleus tractus solitarius. J Neurophysiol. 1988;59:1798–1813. doi: 10.1152/jn.1988.59.6.1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SJ, Silver RA. Glutamate spillover suppresses inhibition by activating presynaptic mGluRs. Nature. 2000;404:498–502. doi: 10.1038/35006649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa S, Kamiya H, Tsuzuki K. Glutamate receptors in the mammalian central nervous system. Prog Neurobiol. 1998;54:581–618. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(97)00085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palkovits M, Zaborszky L. Neuroanatomy of central cardiovascular control. Nucleus tractus solitarii: afferent and efferent neuronal connections in relation to the baroreceptor reflex arc. Prog Brain Res. 1977;47:9–34. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)62709-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamidimukkala J, Hay M. Frequency dependence of endocytosis in aortic baroreceptor neurons and role of group III mGluRs. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H387–H395. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.1.H387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paton JF. A working heart-brainstem preparation of the mouse. J Neurosci Meth. 1996;65:63–68. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(95)00147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paton JF, Boscan P, Murphy D, Kasparov S. Unravelling mechanisms of action of angiotensin II on cardiorespiratory function using in vivo gene transfer. Acta Physiol Scand. 2001;173:127–137. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2001.00898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paton JF, Kasparov S. Differential effects of angiotensin II on cardiorespiratory reflexes mediated by nucleus tractus solitarii – a microinjection study in the rat. J Physiol. 1999;521:213–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00213.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawloski-Dahm C, Gordon FJ. Evidence for a kynurenate-insensitive glutamate receptor in nucleus tractus solitarii. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:H1611–H1615. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.5.H1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. New York: Academic; 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrone MH. Biochemical evidence that L-glutamate is a neurotransmitter of primary vagal afferent nerve fibers. Brain Res. 1981;230:283–293. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90407-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering AE, Boscan P, Paton JFR. Nociception attenuates parasympathetic but not sympathetic baroreflex via NK1 receptors in the rat nucleus tractus solitarii. J Physiol. 2003;551:589–599. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.046615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering AE, Paton JFR. A decerebrate, artificially-perfused in situ preparation of rat: Utility for the study of autonomic and nociceptive processing. J Neurosci Methods. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.01.011. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoepp DD, Jane DE, Monn JA. Pharmacological agents acting at subtypes of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:1431–1476. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seagard JL, Dean C, Hopp FA. Neurochemical transmission of baroreceptor input in the nucleus tractus solitarius. Brain Res Bull. 2000;51:111–118. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(99)00235-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekizawa SI, Bonham AC. Group I metabotropic glutamate receptors on second-order baroreceptor neurons are tonically activated and induce a Na+-Ca2+ exchange current. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:882–892. doi: 10.1152/jn.00772.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semyanov A, Kullmann DM. Modulation of GABAergic signaling among interneurons by metabotropic glutamate receptors. Neuron. 2000;25:663–672. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simms AE, Paton JFR, Pickering AE. Characterization of the role of metabotropic glutamate receptors in the baroreceptor reflex arc at the level of the nucleus tractus solitarii in the rat. J Physiol. 2005;567:PC40. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Stornetta RL, Guyenet PG, McCarty RC. Autonomic nervous system control of heart rate during baroreceptor activation in conscious and anesthetized rats. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1987;20:121–127. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(87)90109-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sved A. GABA-mediated neural transmission in mechanisms of cardiovascular control by the NTS. In: Barraco I, editor. Nucleus of the Solitary Tract. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1994. pp. 245–253. [Google Scholar]

- Talman WT. Kynurenic acid microinjected into the nucleus tractus solitarius of rat blocks the arterial baroreflex but not responses to glutamate. Neurosci Lett. 1989;102:247–252. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talman WT, Perrone MH, Reis DJ. Evidence for L-glutamate as the neurotransmitter of baroreceptor afferent nerve fibers. Science. 1980;209:813–815. doi: 10.1126/science.6105709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoren P, Jones JV. Characteristics of aortic baroreceptor C-fibres in the rabbit. Acta Physiol Scand. 1977;99:448–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1977.tb10397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoren P, Munch PA, Brown AM. Mechanisms for activation of aortic baroreceptor C-fibres in rabbits and rats. Acta Physiol Scand. 1999;166:167–174. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201x.1999.00556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viard E, Sapru HN. Cardiovascular responses to activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors in the nTS of the rat. Brain Res. 2002;952:308–321. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03260-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viard E, Sapru HN. Carotid baroreflex in the rat: Role of glutamate receptors in the medial subnucleus of the solitary tract. Neuroscience. 2004;126:785–794. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Mifflin SW. Excitatory amino-acid receptors contribute to carotid sinus and vagus nerve evoked excitation of neurons in the nucleus of the tractus solitarius. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1995;55:50–56. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(95)00027-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.