A man in his 30s presented with an 18‐month history of a painless 3×4 cm mass in his left temporalis muscle which had grown rapidly in the previous month. There were no neurological or ocular symptoms. Past medical history was unremarkable. The mass was excised and showed a metastatic pigmented malignant melanoma. Immunocytochemistry using antibodies HMB45 and MelanA were both positive. Postoperatively, the patient underwent adjuvant radiotherapy.

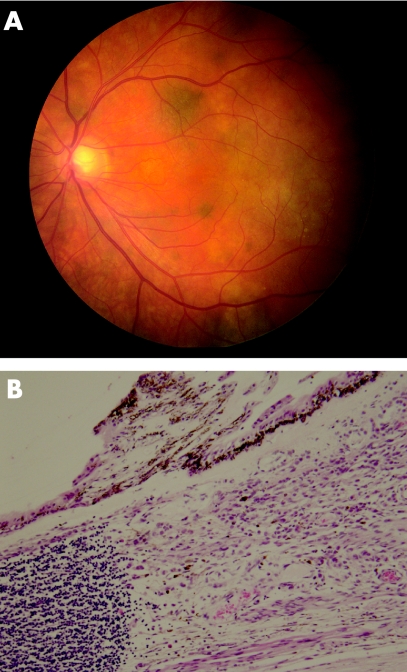

In search for a primary source an in situ superficial spreading pigmented malignant melanoma of the left leg was removed but was not regarded as the primary lesion. Ophthalmological examination detected a pigmented mass in the inferotemporal quadrant of the left iris/ciliary body with pigmented cells seeding the vitreous. Intraocular pressure of the left eye was markedly raised, and the iris architecture was distorted. Fundoscopy showed multiple hyperpigmented choroidal foci involving the posterior pole of the left eye (fig 1A). CT scans of the neck, thorax, abdomen and pelvis were all normal.

Figure 1 (A) Fundoscopy: note depigmented and pigmented nodules. (B) Ciliary body with underlying melanoma and lymphoid aggregate on left side (H&E ×200).

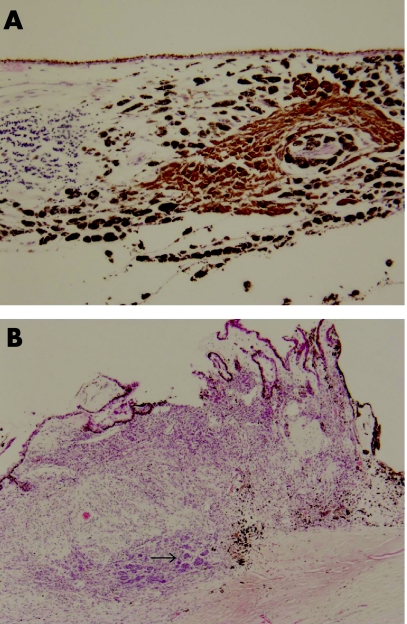

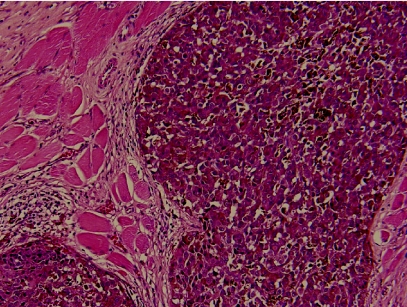

The enucleated left globe confirmed a primary pigmented malignant melanoma of the ciliary body, with maximum thickness of 2 mm (fig 1B). It focally involved the full thickness of the ciliary body, spread into the lateral aspect of the iris and invaded the trabecular meshwork. Multi‐focal satellite‐type nodules were found in the choroid, each surrounded by a dense lymphocytic response, predominantly made up of CD8‐positive T‐cells with a smaller number of CD20‐positive B‐cells (fig 2A). Within the ciliary body there were two distinct patterns of melanocytes. One spindle and round population, which appeared benign, had a low cell proliferation index using MIB1 labelling using Ki 67 and was in keeping with melanocytoma. The other population, arranged in clusters and more epithelioid, had a higher MIB1 labelling using Ki 67 cell proliferation index and showed malignant features (fig 2B). These cells were similar to those present in the metastatic lesion of the left temporalis muscle (fig 3). Several nerve branches within the choroid showed perineural invasion by melanoma. At the angle deep to the ciliary body, a focus of vascular intrascleral invasion was also present. The optic disc and nerve as well as the meninges around the optic nerve were free of invasion.

Figure 2 (A) Microscopy of the choroid showing pigmented satellite nodule with adjacent lymphoid aggregate (H&E ×100). (B) Full thickness of ciliary body showing partly pigmented malignant melanoma with epithelioid portion arrowed.

Figure 3 Epithelioid malignant melanoma (metastatic) in the temporalis muscle (H&E ×100).

Discussion

This case illustrates an interesting histological presentation of a primary malignant melanoma of the ciliary body. Ciliary body melanomas comprise approximately 10% of uveal melanomas; they usually present with ocular symptoms and are amenable to local surgery. Of intraocular melanomas, iris melanomas have the best and ciliary body melanomas have the worst prognosis.1 The median age at diagnosis ranges from 55 to 62 years.1

In ocular melanoma, metastasis is usually haematogenous and in 95% of cases the initial site is the liver.2,3 Liver metastasis is especially frequent with ciliary body melanomas.4 In contrast to cutaneous melanomas, uveal melanomas do not have direct access to the lymphatics and thus cannot initially spread to regional lymph nodes.5 In the present case, several nerve branches within the choroid showed perineural invasion by the tumour, and extraocular metastasis to the left temporalis muscle was found. This might have resulted from perineural invasion of the zygomaticotemporal branch of the maxillary nerve which exits the orbit through the zygomaticotemporal fossa and ends in the infratemporal fossa, the location of the metastasis.6 Perineural spread of ocular melanoma has been well documented previously.7,8 Vascular spread might also account for metastasis in this case.

Histologically, the multi‐focal satellite spread in the choroid and the pronounced lymphocytic immune response around the tumour were highly unusual. Satellite metastasis and central regression is more frequently found in cutaneous melanomas.9,10 A literature search has failed to identify previous reports of this type of “satellite” spread in ciliary body melanoma.

Malignant transformation of choroidal melanocytomas to malignant melanomas has been reported several times.11,12,13 In all of these, the presenting features were due to the primary tumour, characterised by ocular symptoms and neurological deficits. In this case the metastatic lesion in the left temporalis muscle was the only clinical sign at presentation.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Singh A D, Topham A. Incidence of uveal melanoma in the United States: 1973–1997. Ophthalmology 2003110956–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toivonen P, Mäkitie T, Kujala E.et al Microcirculation and tumor‐infiltrating macrophages in choroidal and ciliary body melanoma and corresponding metastases. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 200445(1)1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yanoff M, Fine B. Ocular melanocytic tumours. In: Ocular pathology, 5th edn. St Louis, USA: Mosby Inc, 2002672–689.

- 4.Frau E, Lautier‐Frau M, Labetoulle M.et al Circumstances of choroid and ciliary body melanoma detection. J Fr Ophtalmol 200326905–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lucas D R, Greer C H. Tumours of the uveal tract. In: Chicago: Greer's ocular pathology, 4th edn. Blackwell Scientific Publications 1989113–130.

- 6.Yanoff M, Duker J S. Chapter 2: Orbital anatomy and imaging: clinical anatomy of the orbit. In: Dutton J, ed. Ophthalmology. St Louis, USA: Mosby International, 19992.1–2.7.

- 7.Löffler K, Tecklenborg H. Melanocytoma‐like growth of a juxtapapillary malignant melanoma. Retina 19921229–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolter J R. Orbital extension of choroidal melanoma: within a long posterior ciliary nerve. Tr Am Ophth Soc 19838147–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leiter U, Meier F, Schittek B.et al The natural course of cutaneous melanoma. J Surg Oncol 200486172–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meier F, Will S, Ellwanger U.et al Metastatic pathways and time courses in the orderly progression of cutaneous melanoma. Br J Dermatol 200214762–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barker‐Griffith A E, McDonald P R, Green W R. Malignant melanoma arising in a choroidal magnacellular nevus (melanocytoma). Can J Ophthalmol 197611140–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leidenix M, Mamalis N, Goodart R.et al Malignant transformation of a necrotic melanocytoma of the choroid in an amblyopic eye. Ann Ophthalmol 199426(2)42–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shetlar D J, Folberg R, Gass J D. Choroidal malignant melanoma associated with a melanocytoma. Retina 199919346–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]