Metanephric adenoma (MA) is a benign kidney tumour, accounting for about 0.2% of adult renal epithelial neoplasms.1 Development of MA from tubules of the fetal kidney and relationship with Wilm's tumour (WT) were postulated despite lack of chromosome alterations typically found in WT.2,3 MA has been linked to papillary renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and the differentiation can be challenging in routine pathology. It has been suggested that MA is a distinct tumour entity with specific genetic alterations.4 Many cases do not seem clinically symptomatic.

Clinical presentation

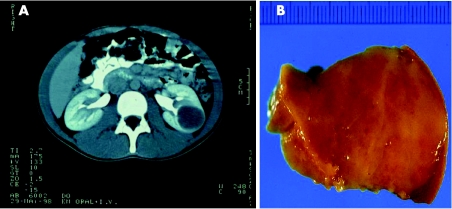

A white teenage boy presented with polycythaemia (haemoglobin 25 g%) and an erythropoietin (EPO) level of 105 mU/ml (8.0‐34.0 mU/ml) in a routine medical check-up. Bone-marrow biopsy ruled out haematological disorders. A CT scan demonstrated a contrastenhancing mass 4 cm in diameter in the lateral middle section of the left kidney. An encapsulated, homogeneous, light-brown coloured tumour was removed and sent in for frozen section. The further course was uneventful.

A woman in her 40s, otherwise healthy, presented with subjective weakness. CT showed a mass 3 cm in diameter with contrast enhancement of the right kidney. The patient underwent a transperitoneal resection of the tumour; the further course was uneventful. No signs for disease progression are found after 5 years in either case.

Macroscopic and histological presentation

Macroscopically, both tumours appeared well circumscribed, round and homogeneous, measuring 3.5 and 3 cm, respectively, in diameter. Both tumours had a light brown cutting surface without cystic lesions, haemorrhage or necrotic areas (fig 1).

Figure 1 Metanephric adenoma of patient 1. (A) CT image of the well‐defined tumour in the left kidney. (B) Macroscopic appearance of the tumour.

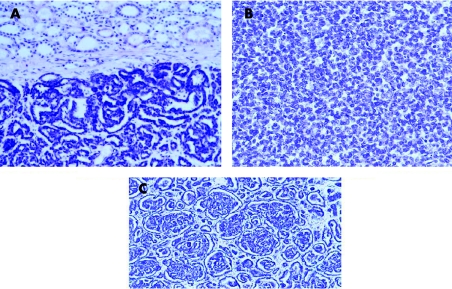

Histologically, both cases showed a well‐circumscribed tumour without any capsule, with tightly packed uniform small epithelial cells forming small acini, tubules and focally glomeruloid structures (fig 2). The cells had a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, with homogeneous chromatin distribution and no cellular atypia. The uniform and round nuclei showed no mitoses.

Figure 2 Histological features of patient 1. (A) Well‐circumscribed tumour without capsule infiltration in adjacent renal parenchyma (H&E, magnification ×100). (B, C) The tumour is composed of small uniform epithelial cells forming small acini and glomeruloid structures (H&E, magnification ×200).

Immunohistochemistry

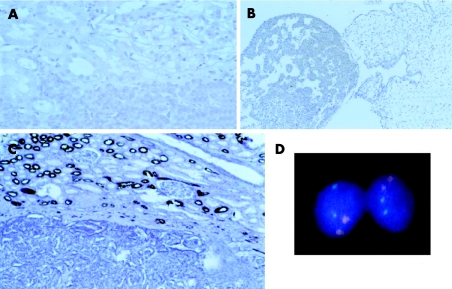

An avidin–biotin peroxidase method with diaminobenzidine was used after microwave antigen retrieval of formalin‐fixed paraffin wax‐embedded material in an NEXUS immunostainer (Ventana, Tucson, Arizona, USA). Both tumours stained positive for pan‐cytoceratin, CK7 and vimentin, and negative for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), CK19 and p53. Case 2 stained negative for EPO (fig 3).

Figure 3 Immunohistochemical and molecular features of patient 1. (A, B) Negativity of the tumour of patient 1 with raised erythropoietin (EPO) serum levels for EPO and fetal liver as positive control. (C) Negativity of the tumour for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA; magnification ×100). (D) Fluorescence in situ hybridisation analysis for centromeres 7 (red) and 17 (green). For both centromeres two signals can be seen.

Molecular methods and results

Fluorescence in situ hybridisation was performed for tumour cells microdissected from frozen sections as described previously.5 Centromeric probes for enumerations of chromosomes 1, 7, 9, 17, X and Y were used (Vysis, Des Plains, Illinois, USA). At least 200 cells were counted for every chromosome. Both tumours had two signals for every investigated centromere in >90% of cells. Comparative genome hybridisation (CGH) was performed as described previously.6 Both tumours showed a normal CGH profile without any losses or gains of chromosomal material (fig 3).

Discussion

Macroscopically, MA appears well circumscribed, round, solid and soft, with a light brown surface. Histologically, it features small uniform epithelial cells of an acinar, tubular, glomeruloid or papillary growth pattern with a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio. The nuclei are oval, with inconspicuous chromatin distribution and display little mitoses.1,7 The two cases presented here display the macroscopic and histological features typical of MA.

Despite no consistent immunohistochemistry staining patterns, there is frequent focal positivity of CK7 and CD57 and positivity for vimentin, but negativity for EMA and S‐100.7,8 This marker profile can be used in differential diagnosis of papillary RCC and WT, as papillary RCC is positive for EMA and CK7.9 Both tumours in our study showed the typical behaviour of MA and could be discriminated from WT and RCC.

Most reports show normal karyotypes for MA.7,8 Our two cases showed no numerical anomalies in chromosomes 1, 7, 9, 17, X and Y, and a normal CGH profile.

MA has been related to the proximal tubule of the fetal kidney owing to morphological, ultrastructural and immunohistochemical similarities.2,8 Some authors state MA to be the benign counterpart of WT despite no deletion of the chromosome 11p13 region, an alteration typically found in WT.3,10 MA has been linked to papillary RCC owing to certain overlaps of histological features and common molecular alterations, as gain of chromosomes 7 and 17 and loss of sex chromosomes have been reported.4 However, MA shows no duplication of chromosomes 7 and 17q21.32, a consistent molecular feature of papillary RCC.3 Thus, it is suggested that MA is a distinct entity. Fluorescence in situ hybridisation analysis could be used in addition to immunohistochemistry for distinguishing this benign tumour from its malignant counterpart.

About 50% of MA do not appear clinically symptomatic, while flank pain, haematuria and polycythaemia have been described.7,10 The cause for the latter condition remains unclear. In our case, no expression of EPO could be demonstrated. Possibly, a mechanical irritation compromised renal blood supply, triggering EPO production.

Most authors describe MA as benign, and only one case of metastatic disease based on a supposed MA diagnosis has been reported.1,11 The two cases presented here did not show any disease progression at 5 years. Thus, MA showing the typical features can safely be regarded as a benign tumour and treatment should consist of local resection.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the University of Regensburg Ethics Committee.

Informed written consent was obtained from both patients in this study.

References

- 1.Amin M B, Tamboli P, Javidan J.et al Prognostic impact of histologic subtyping of adult renal epithelial neoplasms. Am J Surg Pathol 200226281–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muir T E, Cheville J C, Lager D. Metanephric adenoma, nephrogenic rest and Wilm's tumor. Am J Surg Pathol 2001251290–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pesti T, Süksöd F, Jones E.et al Mapping a tumor suppressor gene to chromosome 2p13 in metanephric adenoma by microsatellite allelotyping. Hum Pathol 200132101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown J A, Anderl K L, Borell T J.et al Simultaneous chromosome 7 and 17 gain and sex chromosome loss provide evidence that renal metanephric adenoma is related to papillary renal cell carcinoma. J Urol 1997158370–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Obermann E C, Junker K, Stoehr R.et al Frequent genetic alterations in flat urothelial hyperplasias and concomitant papillary bladder cancer as detected by CGH, LOH, and FISH analyses. J Pathol 200319950–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hartmann A, Rosner U, Schlake G.et al Clonality and genetic divergence in multifocal low‐grade superficial urothelial carcinoma as determined by chromosome 9 and p53 deletion analysis. Lab Invest 20005709–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arroyo M R, Green D M, Perlman E J.et al The spectrum of metanephric adenofibroma and related lesions: clinicopathological study of 25 cases from the National Wilms Tumor Study Group Pathology Center. Am J Surg Pathol 200125433–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gatalica Z, Grujic S, Kovatich A.et al Metanephric adenoma: histology, immunophenotype, cytogenetics, ultrastructure. Mod Pathol 19969329–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsuji M, Murakami Y, Kanayama H.et al A case of renal metanephric adenoma: histologic, immunohistochemical and cytogenetic analyses. Int J Urol 19996203–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grignon D J, Eble J N. Papillary and metaephric adenomas of the kidney. Semin Diagn Pathol 19981541–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Renshaw A A, Freyer D R, Hammers Y A. Metastatic metanephric adenoma in a child. Am J Surg Pathol 200024570–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]