SYNOPSIS

Objective.

The Institute for Public Health and Faith Collaborations sought to cultivate boundary leadership to strengthen collaboration across religious and health sectors to address health disparities. This article presents findings from an evaluation of the Institute and its impact on participating teams of faith and public health leaders.

Methods.

Self-administered surveys were completed by participating team members (n=243) immediately post-Institute. Semistructured telephone interviews were conducted with at least one health and one faith leader per team six to eight months after the Institute.

Results.

Significant self-reported improvement occurred for all short-term outcomes assessed, with the largest increases in describing organizational frames and why they are important for community change, and understanding the role of boundary leaders in community systems change. Six months after the Institute, participants spoke of inspiration, team building, and understanding their own leadership strengths as important outcomes. Leadership growth centered on functioning in groups, making a change in their work, a renewed faith in self, and a renewed focus on applying themselves to faith/health work. Top team accomplishments included planning or implementing a program or event, or solidifying or sustaining a collaborative structure. The majority felt they were moving in the right direction to reduce health disparities, but had not yet made an impact.

Conclusions.

Results suggest the Institute played a role in helping to align faith and health assets in many of the participating teams.

The faith community is an enduring and vital institutional structure within most U.S. communities.1 Because leaders from faith and public health share the goal of ameliorating suffering to advance community health and wholeness, the faith community is a critical partner in shifting social, behavioral, political, and economic determinants of health. Collaboration across these two sectors and alignment of their strengths can make important contributions to efforts aimed at improving community health. As Zahner and Corrado explain, “Local faith-based organizations have historically played a key role in communities by providing social support through community outreach programs, moral structure around life-style choices, and spiritual support through ideologies of hope and faith practices.”2, p. 259

The literature on faith and health tends to highlight parish nursing programs, interventions in chronic disease prevention, and associations between religious beliefs and practices and health outcomes.3–12 Less has been written about harnessing the potential of faith/health collaborations in tackling broader, systemic determinants of health. Gunderson describes religious assets that can be brought to bear on public health problems: congregations; connectional systems such as denominations; interfaith and ecumenical systems; structures owned directly or indirectly by religious organizations; and structures influenced by religious values.13

One approach to aligning these assets with those of public health is to cultivate boundary leaders. Boundary leaders are individuals who operate at the periphery of an organization, moving freely across boundaries to create linkages with the external environment.14,15 Gunderson argues that a critical mass of boundary leaders who can negotiate the space between social structures is key for successful community collaboration.13 Boundary leaders within the disciplines of faith and health have the potential to create new strategies to address health disparities and promote community health through pooling of diverse perspectives and resources. It is the boundary leaders' “hope for the whole system, not just his or her own sphere” that gives them such power, first in recognizing the strengths and weaknesses of the disciplines in which they work, and second in bringing leaders of those disciplines together to address the underlying causes and results of health disparities.16, p. 13

In public health, these same boundary leader characteristics are often referred to as collaborative leadership and transorganizational competencies.17–20 Collaborative leadership, particularly the skills to create linkages across diverse sectors, was identified by the Turning Point Initiative as a critical public health competency for the 21st century.17 Wilson defines a collaborative leader as “one who inspires commitment and action, leads as a peer problem solver, builds broad-based involvement, and sustains hope and participation.”17, p. 22 In a review of the literature on collaborative leadership, Larson and colleagues discuss the importance of building vision, managing change processes, and political competencies.19 Exhibiting leadership skills through horizontal power sharing rather than through vertical hierarchies is another critical component of collaborative leadership that is central to boundary leadership. These collaborative and transorganizational skills are necessitated by the complexity of public health problems—such as elimination of health disparities—that often require solutions beyond a single organization, sector, or discipline.20

Leadership development is a promising strategy for strengthening faith/health collaboration. Within public health, leadership development has grown over the last decade in response to several national reports calling for improved workforce development, in combination with acknowledgment that solutions to complex public health problems require collaboration across sectors and levels.17,20–22 Given this strong interest in leadership development as a strategy for strengthening the public health workforce, it is important to understand whether these programs are effective and what kind of outcomes they produce.

In an evaluation of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)-funded National Public Health Institute, Woltring et al. conducted a retrospective assessment of the first eight cohorts through mailed surveys and follow-up interviews with a subset of participants.23 Respondents reported improved leadership skills such as taking risks to accomplish objectives, organizational improvements such as designing more effective management teams, and improved community leadership skills including coalition development for policy action. Umble et al. evaluated the Institute more recently after it shifted to a team-based model, using follow-up telephone interviews with one member per team. They reported individual, network, and team outcomes, suggesting the Institute improved collaborative leadership skills, expanded networks for problem solving, and led to team projects such as needs assessments and new programs, services, or resources.18

THE INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC HEALTH AND FAITH COLLABORATION

In 2001, with financial support from CDC, the Interfaith Health Program (IHP) at Emory University's Rollins School of Public Health launched the Institute for Public Health and Faith Collaborations to address health disparities. The Institute's mission is to cultivate boundary leadership needed to assure effective collaboration across religious and health sectors. The Institute trains teams of health and religious leaders to address community-scale, underlying systemic conditions associated with health disparities.

All of the learning in the Institute takes place within community teams of at least two faith and two health leaders per community. The Institute progresses over four days, moving from personal engagement to team engagement to community engagement. Curriculum content covers the nature of health disparities, self- and leadership awareness, the role of tension in leadership relationships and community transformation, organizational reframing skills, systems thinking, boundary leadership, and creating a vision, covenant, and concrete plan for collaborative action. Learning strategies include presentations by experts, self-reflective activities including a personality profile, and team exercises such as developing a vision and action plan for reducing health disparities. The expectation is that participating teams will move the vision and plan forward after returning to their communities. Although the Institute does not formally engage participating teams through follow-up sessions, IHP does provide ongoing learning and communication opportunities through Institute-wide conference calls every other month and an e-mail discussion group.

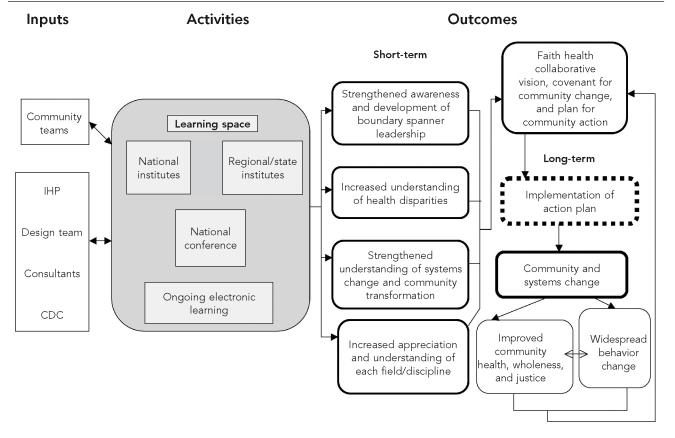

The logic underlying the Institute curriculum is depicted visually in the Figure. The logic model shows that for individuals, participation in the Institute should result in: strengthened awareness and development of boundary leadership, increased understanding of health disparities, increased appreciation and understanding of each field/discipline, and strengthened understanding of systems, systems change, and community transformation. These short-term outcomes should inform a team's vision and covenant for community change and a plan for community action that, if well implemented, could result in community and systems change.24,25 Fawcett and colleagues operationalize these systems changes as new or modified programs, policies, or practices, and view them as initial markers of progress in the pathway to more distal health outcomes.24,26,27 These systems changes, in turn, should contribute to improved community health, wholeness, and justice, as well as widespread behavior change. The specific pathways to community transformation vary depending on community context, nature of the health disparities selected for action, and strategies undertaken.

Figure.

Logic model for the Institute for Public Health and Faith Collaborations

IHP = Interfaith Health Program

CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

This article presents selected evaluation findings from the Institute for Public Health and Faith Collaborations and its impact on the participating teams of faith and health leaders. Specifically, we report on short-term, individual-level outcomes in the logic model such as awareness and development of boundary leaders and strengthened understanding of systems change. To learn how boundary leadership may have been strengthened, we also assessed individual leadership growth and how participation affected teams. We also documented top team accomplishments to learn about implementation of their action plans and spin-off activities. Last, we asked about perceived impact on health disparities, as this was a major focus of the Institute and a critical indicator of community health, wholeness, and justice.

METHODS

Study participants

Three national and three regional Institutes were held during the time frame of the evaluation. Eligible study participants included all team members who attended any of these six Institutes held between September 2002 and July 2004. This consisted of 53 teams and 243 individuals, with a mean of 4.6 members per team. Three Institutes were recruited nationally (28 teams) and three were recruited regionally from Los Angeles (nine teams), Pennsylvania (six teams), and Wisconsin (10 teams). The content and format of the Institute remained fairly constant over time.

Teams applied to participate in the Institute and were selected competitively by IHP staff for the national institutes and with local cosponsors for the regional institutes, using the following criteria: (1) at least two religious leaders and two health leaders with no more than five members total on the team, (2) a demonstrated history of collaboration among leaders on the team, and (3) a demonstrated commitment to collaborative work and to the elimination of health disparities. In addition, selected teams represented the race, religion, and ethnicity needed to achieve the desired health disparity outcomes; and team members were formal and informal leaders who had positions and roles in the community necessary for boundary leadership and community-scale change. Health representatives included state and local public health officials, as well as leaders from health systems, health centers, and other health-related organizations.

Data collection

On the final day of each Institute, participants were asked to complete a four-page written survey. The instrument was adapted from a tool developed by Umble and colleagues for the National Public Health Leadership Institute.18 The survey included two major sections: views about the Institute and short-term outcomes. The second section consisted of a retrospective pretest on short-term outcomes through an assessment of the participants' confidence to perform a selected skill when they arrived for the Institute relative to their confidence to perform the skill on the last day of the Institute. The retrospective pretest methodology is useful when administration of a pretest would be intrusive, when self-assessment of personal growth or skill acquisition is an adequate outcome, and when response-shift bias is a concern.28 The latter occurs when program participants change their metrics or standards for judging their knowledge or skill over the course of an intervention. We chose not to administer a traditional pretest because it would have been inconsistent with the design of the curriculum, which emphasized community-building and the value of internal team resources.

For each of 15 skills, participants were asked, “Please rate your confidence that you could have performed that skill on the day that you arrived for the Institute. Then, rate your confidence that you could perform the same skill today, the last day of the Institute.” Response options ranged from 1 = not at all confident to 5 = completely confident. Following are examples of the skills assessed: identify the potential contribution of the faith community in eliminating health disparities, understand the role of boundary leaders in systems change, understand the four organizational frames, and create and implement a shared vision for a healthy community. These short-term outcomes closely matched the Institute's learning objectives. Surveys were completed by 220 participants, with a response rate of 90.5%.

Semistructured telephone interviews were completed with participants six to eight months post-Institute; efforts were made to interview at least one health and one faith leader per team. Team members who attended one of four selected Institutes were contacted by e-mail or telephone to determine their willingness to participate and to schedule a convenient time for the interview. The team liaisons were typically contacted first. At the end of their interview, they suggested a second participant from their team. In situations where either the team liaison or the recommended team member could not be contacted, additional members were invited to participate. Up to eight attempts were made to contact each potential participant. Approximately 99 individuals were contacted, with 62 completing an interview (response rate of 62.6%).

Thirty-two health leaders, 21 faith leaders, and eight people representing the social service/education sectors were interviewed. A mean of 1.8 interviews was conducted per team. The majority of nonrespondents did not refuse to be interviewed, but rather could not be reached after multiple attempts. Verbal informed consent was obtained from those interviewed and the interviews typically took about 45 minutes to complete. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board.

The interview guide consisted of 16 questions that encompassed what participants learned, whether and how participation affected their leadership, how participation affected their teams, and what their team had accomplished since the Institute. They were also asked to discuss their team visions and how they had evolved, whether faith/health collaborations had improved as a result of the Institute, and their progress in addressing health disparities. The final questions asked about networking and suggestions for improving the Institute.

Data analysis

Quantitative survey data were entered into SPSS and analyzed descriptively.29 Paired t-tests were used to assess changes in the short-term outcomes from the retrospective pre- to post-measures. Analyses were conducted for all participants combined, and also by discipline. The latter was of interest as health and faith were the two disciplinary boundaries to be crossed. In addition, to assess whether the Institute had a differential impact on faith and health leaders, sums of change scores were created for each individual and compared by discipline using an independent sample t-test.

The qualitative interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. A code book was developed to reflect the major topics covered in the interviews. Each transcript was coded independently by two members of the evaluation team, with discrepancies resolved through discussion. The qualitative analysis software QSR-N6 was used for storing, retrieving, and analyzing interview data.30 A series of data matrices were then prepared to help identify themes and patterns for the cross-team analyses.31,32 The unit of analysis varied depending on the nature of the topic, but for the most part analysis centered on the team. Brief case studies were also developed to provide more in-depth examination of each team.

RESULTS

Description of Institute participants

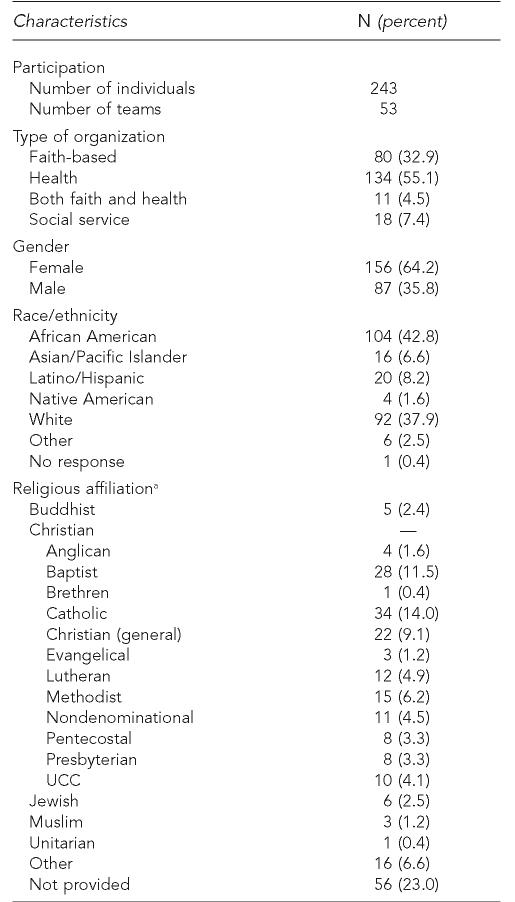

Table 1 presents demographic characteristics of the participants. African Americans were best represented (43%), followed by white participants (38%). More women (64%) participated than men (36%), and approximately 33% of the participants represented a faith-based organization. Of those reporting their religious affiliation, the majority were Christian, with Catholics and Baptists as the largest groups.

Table 1.

Background information on Institute participants

Only faith leaders were asked to designate a religious affiliation.

UCC = United Church of Christ

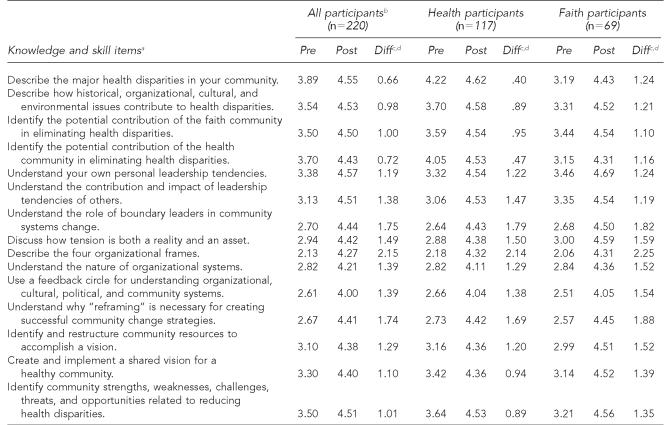

Table 2 shows results from the retrospective pretest and posttest comparisons by discipline. All changes were statistically significant. Among participants from the health field, the largest increases were observed for describing the four organizational frames, understanding the role of boundary leaders in community systems change, and understanding why reframing is necessary in creating successful community change strategies. Likewise, participants from the faith community reported substantive gains in these areas. Health representatives reported the least change for describing major health disparities in their communities and for identifying the potential contributions of the health community in eliminating health disparities. In contrast, faith representatives reported learning a great deal about health disparities. We also compared total change scores by discipline (not shown). The mean total change score was 18.2 (standard deviation [SD]=9.71) for health leaders and 22.8 (SD=11.5) for faith leaders. This difference was statistically significant (t=2.666, degree of freedom 108, p=0.009), with faith participants reporting more overall change than those from the health sector.

Table 2.

Pre/post assessments of knowledge and skills gained through participation in the Institute

Participants rated their confidence in their ability to perform each skill prior to the Institute and then again on the last day of the Institute using response options ranging from 1 = not at all confident to 5 = completely confident.

All participants includes 31 other disciplines and three missing disciplines.

Paired t-tests were used for pre/post comparisons and all were statistically significant at p<0.0001.

Differences may not exactly equal the differences between post- and pre-scores due to rounding.

Diff = difference

What participants learned at the Institute

In the follow-up telephone interviews, team members were asked to name the top one or two things they learned at the Institute. One group of participants commented that learning about other collaborative efforts and faith/health programs around the country was inspiring. Others were pleased to learn the issues they were struggling with were not unique and that a national faith/health collaboration movement existed.

Another strong theme was related to relationships among team members. Members from several teams discussed how they grew to know their team members at a much deeper and personal level as a result of the Institute. Leadership strengths also emerged as a significant theme, with many participants stating that they learned about their own leadership style and described how this was useful to them. For example, one health leader commented, “The ability to identify where exactly my strengths lie, it allows me to focus my resources and my time to move those endeavors along.”

Others expressed appreciation for the notion of boundary leadership and had applied it to their work. One faith leader commented, “[I] really liked the idea of the boundary leader concept and have been thinking about that in my work with congregations in terms of how that might look.” Others explained that they learned more about how faith and public health can work together, for example, “how to develop the relationships needed within the faith community. How to recognize those leaders that you can partner with so […] that a two-way communication can develop.”

For some, the Institute energized them to focus their work on health disparities. As one faith leader explained, “It really kind of got me recommitted, reenergized around dealing with health disparity issues and really trying to find ways to apply churches around that.” Finally, a few participants, mainly from the first Institute, reported they did not learn much, in part because they were already well versed in the issues covered.

Leadership growth

Participants were asked whether and how participation in the Institute changed their leadership. One set of respondents gave examples of how their functioning in groups and other collaborative settings had changed. For example, they described how they now see conflict differently, that they routinely reflect on where people are coming from, or that they try to be better listeners. One health leader explained, “I thought that was a very strong message of the leadership content, that everyone has their strengths as leaders, and it's so important to try to learn and understand those strengths, to understand how to best communicate with a particular individual and work together.”

Another group of respondents described how participation had contributed to a very specific change in their work, such as improved connections with a select faith group within their community, or more focus on programs for underserved populations. Similarly, a few of the respondents described how they were now more intentional about applying their leadership skills to faith/health collaborative work. Others described how the Institute gave them renewed faith in themselves and their own leadership skills. As one participant noted, “it kind of renewed my own faith in myself—and what I can do and how much more I can do.”

Lastly, a few participants stated they had gained some insights or had certain concepts reinforced, but had not changed anything major in terms of their leadership. Others commented that they had been through numerous leadership institutes before this one and reported they had not changed anything in their leadership as a result of this particular institute.

Impact on teams

A small number of teams reported that the Institute had no or only a minimal effect on them. They were likely to describe current relationships among team members as limited to sharing of information or some increase in communication. There were a few negative reports, but the majority were positive. Some, though, described personality differences that could not be surmounted during or after the Institute. For example, one faith leader whose team is no longer meeting noted, “[team members had] an excessive, extreme difference in knowledge, experience, and openness to what is faith and health.”

A second level of impact was best described as “getting to know each other better” but with no cohesive bond. On a number of these teams, leaders reported individual development and growth but not team development. They describe the effect as improved relationships or “friendships.” For a few, two or three members of the team may still have a close collaborative relationship.

The largest number of teams reported they “coalesced as a team.” Words like “bond,” “kinship,” “solidarity,” and “able to gel” were used to describe what happened during the Institute. One health leader explained, “We came together on a united front to look at the problems in our community and to understand what each could bring to the table.” These teams described their relationships now as providing a new level of support to one another—both personal and organizational. Quite a number in this category described experiencing tension or struggling with frustration during the Institute and most were able to make it through this barrier. As one faith leader recalled her team dynamics, she explained, “It really helped to create a good kind of tension that's needed for the two entities to come together.”

A fourth set of teams experienced tension within the team but were then able to see it as an asset and describe how this had transferred to the work back in their communities. They were willing to take risks together, deriving confidence from this experience along with the recognition of their strengths and differences. Trust-building was something they spoke of as having happened within the team and as paramount in their community work. As one health leader explained, “Some barriers were broken down in terms of talking about things that, kind of the elephants in the living room [referring to racism], that stuff that was there that we hadn't talked about in the past, building of trust between us.”

Team accomplishments

Team members were asked to name what they considered their major accomplishments since returning home from the Institute. The strongest theme was planning for or implementing a specific program. Some of these were done by part of a team rather than the whole team, and in some cases, these programs were underway prior to the Institute. Examples of these programs include a heart health campaign for African American women and a health institute to train clergy in emergency response techniques. Another theme was the pulling together of a community event such as a health fair or a breakfast with clergy to promote faith and health collaboration.

Still others explained that their major accomplishment was bringing people together and expanding the number and diversity of partners involved in the faith/health conversation. One faith leader, for example, described her team's top accomplishment as, “the increase in both the number and extent of involvement of diverse partners in what I'll call the conversation about health and faith collaboration.” A related accomplishment was the simple fact the teams had solidified and sustained a group that was working on these issues. A few others commented that they were continuing, that they were still in the connecting phase, or were “getting the ball rolling.” As one health leader noted, “There is a core, there is an identifiable place that if you're talking about faith and health, there are certain people that can be contacted to make all the connections, and so I think our success is solidifying some connections.”

Progress in reducing health disparities

The majority of respondents thought they were moving in the right direction in terms of reducing health disparities, but acknowledged that it was a momentous undertaking and would take considerable time and effort to have a significant and measurable impact. One faith leader commented, “I think it takes years to be able to really see what impact you have been able to make, and I doubt very seriously if we've affected any of the disparities issues, other than, perhaps, changing how people think about it.”

Respondents from a few of the teams were more direct in stating that their teams had not made any progress in reducing health disparities, and a couple of respondents acknowledged that although their teams had not contributed in a major way, they had helped to create some synergy in their communities around the need to address health disparities.

Finally, respondents from a few other teams believed they had made a contribution to reducing health disparities, typically through a very specific program or initiative. For example, one health leader commented, “Yeah, by making the clinic more accessible to people and providing language accessibilities … before they were afraid to go … because of the language barrier.”

DISCUSSION

This evaluation examined outcomes associated with participation in the Institute for Public Health and Faith Collaborations. The Institute model includes leaders from the faith community and public health in team-based leadership development with the goal of contributing to an infrastructure in communities capable of addressing social and public health problems, especially health disparities. Findings suggest the Institute contributed to a range of individual-level outcomes. Participants reported statistically significant changes in all of the knowledge and skill areas assessed through the retrospective pretest/posttest. Topics with the largest change in scores focused on organizational frames and the role of boundary leaders in community systems change. These were among the topics with the lowest pretest scores, which suggests participants were less familiar with them prior to the Institute. Faith leaders reported greater increases than health leaders in the short-term outcomes, likely because the health-related content was newer for them.

When asked to qualitatively reflect on what they had learned at the Institute six to eight months post-Institute, participants spoke of inspiration, team-building, and understanding their own leadership strengths. Participants also mentioned the boundary leader concept and a focus on disparities. When asked to comment on their leadership growth, the themes centered on functioning in groups, a specific change in their work, a renewed faith in self, and a renewed focus on applying themselves to faith/health work.

The individual-level outcomes found in our study are consistent with the types of results outlined in a newly developed framework for evaluating leadership development programs that identifies results as episodic, developmental, and transformative.33 Episodic refers to time-bound and predictable results tied to the content of the program. Understanding organizational frames and the boundary leader concept are examples from our evaluation. Developmental changes occur over time and as a series of steps. Examples from our findings include changing how one functions in groups. Transformative changes are “fundamental shifts in individuals, organizational or community values, and perspectives that seed the emergence of fundamental shifts in behavior or performance.”33, p. 7 A commitment to focus one's work on faith/health collaboration may be considered a transformative change.

Eliminating health disparities and changing systemic issues underlying complex public health problems requires more than individual-level change; it also requires collaboration across diverse sectors and engagement by leaders with collaborative leadership competencies.20 Because a majority of the teams attending the Institute reported getting to know their team members at a much deeper level and being able to provide a new level of support to one another—both personal and organizational—this curriculum shows promise as a model for changing how leaders in multisectoral teams function in collaborative relationships. In 2005, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation funded a scan of health leadership development programs that found: “… the quality and density of the connections among leaders from different sectors correlates with their ability to understand, trust, and respect one another; and to work collaboratively on planning, projects, and collective action.”34, p. 17

Participants were also asked to describe their team's primary accomplishment. These accomplishments were clustered into two general areas: planning or implementing a specific program or event and solidifying and/or sustaining a collaborative structure focused on faith and health and/or health disparities. Our findings on team accomplishments are similar to those found by Umble and colleagues in their evaluation of the 12-month National Public Health Leadership Institute.18 They also reported formation of a workgroup or advocacy group as a relatively common team accomplishment.

This evaluation has multiple strengths worth noting. It used mixed methods (e.g., quantitative surveys on-site and qualitative follow-up interviews), participants were followed for six to eight months post-Institute, and interviews were conducted with two members of each team, which allowed for triangulation of responses and strengthened reliability of findings.

Limitations

This evaluation also has some limitations. First, almost all of the data are self-reported, leading to the possibility that a social desirability bias led participants to report team activity in a positive light and to attribute at least some of their progress to the Institute. In particular, the retrospective pretest, despite several advantages, is vulnerable to recall, social desirability, and effort justification biases, which can contribute to inflated change scores.28

Second, participants from only four of the six Institutes were interviewed. Given the consistency of responses across these four Institutes, however, it appears that sufficient interviews were conducted to detect the full range of responses and perspectives.

Third, we interviewed the team liaison and a second person they recommended as knowledgeable about the team's activities. This approach may have resulted in a selection bias favoring those with more positive views of the Institute and their own faith/health collaborative work.

Fourth, as in many studies that attempt to document organizational and community change, it is difficult to attribute outcomes to a single program. In this evaluation, teams were selected to participate based on a certain level of readiness to effect community change or to address health disparities. This readiness may very well be the major force driving team accomplishments, making it difficult to separate out the contributions of the Institute per se. The short-term outcomes assessed through the survey on the final day of the Institute and the telephone interview questions about what they learned at the Institute are the strongest indicators of what participants themselves felt they gained directly from the Institute.

CONCLUSION

One of the observations made in recent reviews of leadership development is that evaluations often focus on short-term outcomes in individuals, and even though programs seek to create change in organizations, communities, and systems, the links between individual change and changes outside the individual are not well articulated.35 Most commonly, evaluations assess new knowledge and skills and changes in attitudes or perceptions, usually during the course of the program.

Our evaluation was guided by a logic model and a general theory of change; however, the model has some very large leaps of faith. Most notably, we assume that implementation of action plans will lead to community changes that ultimately reduce health disparities. This logic will only work, of course, if the action plans detail activities that will truly impact health disparities. Articulating the types of actions and types of systems changes needed to make a difference in health disparities is an important next step in understanding how alignment of faith and public health assets can contribute to the shared goal of community health and wholeness.

Acknowledgments

Many people contributed to this evaluation. The authors offer special thanks to the Interfaith Health Program staff, especially Gary Gunderson for his vision of boundary leadership and Debbie Jones for her support throughout the evaluation. The authors also thank the Design Team for their conceptual work on the Institute, and Brad Gray and his team for developing the curriculum for the Institute. In addition, the authors thank members of the Evaluation Design Work Group and Evaluation Review participants who played important roles in helping design the evaluation methodology and interpret its results. Lastly, the authors thank the team members for their commitment to faith and health collaborative work and their willingness to participate in this evaluation.

Footnotes

This evaluation was partially supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention through Association of Schools of Public Health Cooperative Agreement 51929-21/23.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ammerman N. Congregations and community. New Brunswick (NJ): Rutgers University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zahner SJ, Corrado SM. Local health department partnerships with faith-based organizations. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2004;10:258–65. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200405000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson CM. The delivery of health care in faith-based organizations: parish nurses as promoters of health. Health Communication. 2004;16:117–28. doi: 10.1207/S15327027HC1601_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buijs R, Olson J. Parish nurses influencing determinants of health. J Community Health Nurs. 2001;18:13–23. doi: 10.1207/S15327655JCHN1801_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Voorhees CC, Stillman FA, Swank RT, Heagerty PJ, Levine DM, Becker DM. Heart, body, and soul: impact of church-based smoking cessation interventions on readiness to quit. Prev Med. 1996;25:277–85. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Resnicow K, Jackson A, Braithwaite R, DiIorio C, Blisset D, Rahotep S, et al. Healthy Body/Healthy Spirit: a church-based nutrition and physical activity intervention. Health Educ Res. 2002;17:562–73. doi: 10.1093/her/17.5.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Resnicow K, Campbell MK, Carr C, McCarty F, Wang T, Periasamy S, et al. Body and soul. A dietary intervention conducted through African-American churches. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yanek LR, Becker DM, Moy TF, Gittelsohn J, Koffman DM. Project Joy: faith based cardiovascular health promotion for African American women. Public Health Rep. 2001;116(Suppl 1):68–81. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.S1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell MK, Demark-Wahnefried W, Symons M, Kalsbeek WD, Dodds J, Cowan A, et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and prevention of cancer: the Black Churches United for Better Health project. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1390–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koenig HG, George LK, Cohen HJ, Hays JC, Larson DB, Blazer DG. The relationship between religious activities and cigarette smoking in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1998;53:M426–34. doi: 10.1093/gerona/53a.6.m426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chatters LM. Religion and health: public health research and practice. Annu Rev Public Health. 2000;21:335–67. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeHaven MJ, Hunter IB, Wilder L, Walton JW, Berry J. Health programs in faith-based organizations: are they effective? Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1030–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.6.1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gunderson GR. Backing onto sacred ground. Public Health Rep. 2000;115:257–61. doi: 10.1093/phr/115.2.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams P. The competent boundary spanner. Public Administration. 2002;80:103–24. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leifer R, Delbecq A. Organizational/environmental interchange: a model of boundary spanning activity. Acad Manage Rev. 1978;3:40–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gunderson GR. Boundary leaders: leadership skills for people of faith. Minneapolis: Fortress; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson JL. Leadership development: working together to enhance collaboration. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2002;8:21–6. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200201000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Umble K, Steffen D, Porter J, Miller D, Hummer-McLaughlin K, Lowman A, et al. The National Public Health Leadership Institute: evaluation of a team-based approach to developing collaborative public health leaders. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:641–4. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.047993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larson C, Sweeney C, Christian A, Olson L. Collaborative leadership and health: a review of the literature. Seattle: Leadership Development National Excellence Collaborative, Turning Point Initiative; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wright K, Rowitz L, Merkle A, Reid WM, Robinson G, Herzog B, et al. Competency development in public health leadership. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:1202–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.8.1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Institute of Medicine. The future of the public's health in the 21st century. Washington: National Academy Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Umble K, Orton S, Rosen B, Ottoson J. Evaluating the impact of the management academy for public health: developing entrepreneurial managers and organizations. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2006;12:436–45. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200609000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woltring C, Constantine W, Schwarte L. Does leadership training make a difference? The CDC/UC Public Health Leadership Institute: 1991–1999. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2003;9:103–22. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200303000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fawcett SB, Lewis RK, Paine-Andrews A, Francisco VT, Richter KP, Williams EL, et al. Evaluating community coalitions for prevention of substance abuse: the case of Project Freedom. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24:812–28. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kegler MC, Twiss JM, Look V. Assessing community change at multiple levels: the genesis of an evaluation framework for the California Healthy Cities Project. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27:760–79. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paine-Andrews A, Fisher JL, Berkely PJ, Fawcett SB, Williams EL, Lewis RK, et al. Analyzing the contribution of community change to population health outcomes in an adolescent pregnancy prevention initiative. Health Educ Behav. 2002;29:183–93. doi: 10.1177/109019810202900204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Francisco VT, Paine AL, Fawcett SB. A methodology for monitoring and evaluating community health coalitions. Health Educ Res. 1993;8:403–16. doi: 10.1093/her/8.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hill L, Betz D. Revisiting the retrospective pretest. Am J Evaluation. 2005;26:501–17. [Google Scholar]

- 29.SPSS Inc. SPSS: Release 13.0.1. Chicago: SPSS Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richards L. Using N6 in qualitative research. Melbourne (Australia): QSR International Pty. Ltd; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miles M, Huberman A. Qualitative data analysis: a sourcebook of new methods. Beverly Hills (CA): Sage Publishing; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patton M. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grove J, Kibel B, Haas T. EVALULEAD: a guide for shaping and evaluating leadership development programs. Oakland (CA): The Public Health Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leadership Learning Community. A scan of health leadership development programs. Battle Creek (MI): The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Development Guild/DDI Inc. Evaluating outcomes and impacts: a scan of 55 leadership development programs. Battle Creek (MI): W.K. Kellogg Foundation; 2002. [Google Scholar]