Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

— George Santayana

Spanish Influenza of 1918–1919 killed more than 50 million people worldwide over the course of two years.1 The true origin of the 1918 influenza pandemic is unknown. During World War I, propaganda in war-engaged countries only permitted encouraging news, so as a neutral party, Spain was the first country to publicly report on the health crisis.1 Thus, Spanish Influenza became a popular term. However, historical research has shown that Spain was an unlikely candidate as the initial source and some suggest that it originated in Kansas in the spring of 1918.

Influenza pandemics have occurred regularly every 30 to 40 years since the 16th century. Today, influenza experts consider the possibility of another influenza pandemic, not in terms of if but when. Due to the high likelihood of an influenza pandemic, planning is underway in many U.S. states and other countries. We reviewed the responses of two neighboring Minnesota cities during the 1918–1919 pandemic to gain insight that might inform planning efforts today.

Many of the components of current pandemic influenza plans were utilized to some degree in Minneapolis and St. Paul during 1918–1919. Coordination between different levels and branches of government, improved communications regarding the spread of influenza, hospital surge capacity, mass dispensing of vaccines, guidelines for infection control, containment measures including case isolation and closures of public places, and disease surveillance were all employed with varying degrees of success. We focus on medical resources, community disease containment measures, public response to community containment, infection control and vaccination, and communications.

PANDEMIC BEGINNINGS IN MINNESOTA

Minnesota's first Spanish Influenza cases were identified in the last week of September 1918. As in the rest of the country, Minnesota's first cases “were directly traceable to soldiers, sailors, or [their] friends.”2 Every military base and military hospital in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area was severely affected. Case isolation was slowly implemented at both Fort Snelling and the Dunwoody Naval Detachment (military installations in Minneapolis). On September 30, the first day of isolation, cases numbered in the hundreds.3

Influenza cases were not limited to enlisted men for long. In Minneapolis, the number of civilian cases outstripped the number of military cases for the first time on October 9, less than two weeks after the first case was identified in the state (700 civilian cases; 675 cases at Fort Snelling).4 Influenza had become a reportable condition in Minnesota on October 8 in response to the growing epidemic.5

MEDICAL RESOURCES

Two major issues contributed to the gravity of the pandemic: the war effort and limited scientific knowledge. World War I was not only costly, it required much of the medical community to be stationed overseas. In 1918, little was known about influenza. While this lack of knowledge did not negatively impact infection control actions, effective treatment and prevention methods were not fully utilized.

When influenza first appeared in Minnesota on September 27, the state was ill equipped for a health crisis.2 Although World War I was coming to an end, more than four million Americans were mobilized and the nation's resources were directed to supporting the war effort. An editorial in the Minneapolis Tribune daily newspaper described the lack of physicians and nurses: “The medical fraternity is severely taxed already. So many physicians and surgeons have gone to Europe or to training that those at home have more than they can attend to comfortably and to good advantage.”6

The number of influenza patients that needed the attention of physicians and nurses overwhelmed St. Paul and Minneapolis clinicians. The war's considerable drain on the medical profession was compounded by other factors that hindered nurse and physician mobilization. Methods to keep them healthy while caring for influenza patients were ineffective. Many health-care providers fell ill, and some died. At one point, Minneapolis's City Hospital reported that “nearly half of the nursing staff has been ill with influenza in the last three weeks.”7 This bleak situation discouraged some clinicians from providing their services. Dr. H.M. Bracken, Secretary of the Minnesota State Board of Health, reported to Dr. Rupert Blue, U.S. Surgeon General, on his campaign to recruit physicians for the influenza effort: “A number who we have called for have made excuses and have not come at all.”8 Other physicians who were recruited by Dr. Bracken simply did not show up.9

Dr. Bracken attempted to secure senior medical students for influenza work. Dr. Bracken worked not only with the U.S. Surgeon General but also with the Surgeon General of the Army, the Committee on Education and Special Training, and the Dean of the University of Minnesota Medical School for three weeks and still was unable to obtain senior medical students for assistance, because each party insisted that someone else had to authorize it. In the end, Bracken failed to receive any medical students.10

Not surprisingly, Minneapolis and St. Paul hospitals proved to be inadequate to handle the large number of patients. Minneapolis's City Hospital and St. Paul's St. John's Hospital were solely devoted to treating influenza patients. Non-influenza patients were transferred to other area hospitals. This inadequacy was not entirely due to the lack of beds and supplies; there simply were not enough healthy nurses. At City Hospital, Superintendent Dr. Harry Britton reported that the “hospital was caring for about 150 cases, and had about 70 on the waiting list. It had beds available for that waiting number, but not nurses.”11

In St. Paul, a system was set up between St. John's Hospital and other hospitals to insure an adequate number of nurses to care for influenza patients, but unfortunately this system failed. Dr. F.C. Plondke, St. John's Hospital's Medical Director, complained that the other hospitals were abandoning their promises to assign help from their nursing staff. “The other hospitals had refused to furnish a single nurse to aid the fifteen who are caring for ninety patients at St. John's from their individual nursing staffs.”12

In 1918, medical science maintained that influenza was bacterial in origin. Physicians at Fort Snelling claimed that the “bacillus influenza of Pfeiffer,” which is today known as Haemophilus influenzae, was the cause of Spanish Influenza.1,13 Nevertheless, despite this lack of understanding about viruses, advice to curb infection was relatively accurate. The Minnesota State Board of Health recommended the use of handkerchiefs to cover sneezes and coughs, plenty of fresh air, avoidance of the sick and of crowds, and to contact a physician if ill.14

COMMUNITY DISEASE CONTAINMENT

As influenza was beginning to take hold in the civilian population, there was disagreement between the Minneapolis and St. Paul health commissioners, Dr. Guilford and Dr. Simon, respectively. Their approaches varied; Dr. Guilford tended to be broadly proactive to prevent cases, whereas Dr. Simon tended toward initiating activities in response to individual cases. Dr. Guilford believed that closing public places was the best course of action and that isolation of individual cases was useless.15 Dr. Simon asserted that isolation of influenza cases would be more effective in preventing the spread of disease.14

The St. Paul Health Department and the Minnesota State Board of Health met Dr. Guilford's strong advocacy with opposition. Dr. Bracken, siding with St. Paul, questioned, “If you begin to close, where are you going to stop? When are you going to reopen, and what do you accomplish by opening”?11

Debate between the two cities on the merits of closing schools caused further strain. Dr. Simon held that St. Paul's school nurses were the best defense against the spread of the disease, and that closing schools would allow cases to go undetected as the children would not be under any medical supervision. Dr. Guilford disagreed, pointing out that 30 school nurses would not be able to adequately care for the 50,000 pupils in the Minneapolis public school system during a pandemic.16 Minneapolis closed the schools on two separate occasions (October 12 to November 17, and December 10 to December 29, 1918).

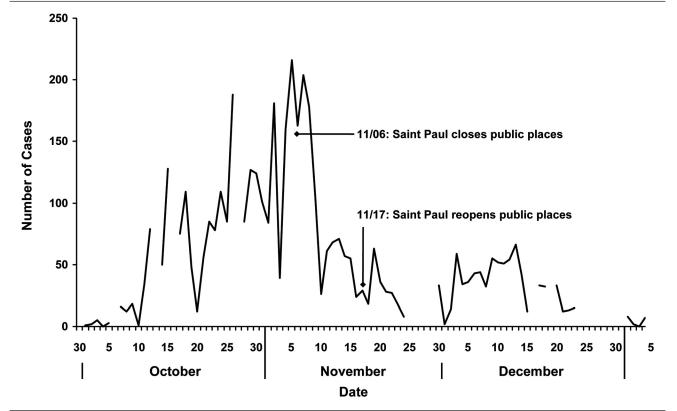

Despite Dr. Simon's conviction that the closing of public places would be ineffective, on November 6 St. Paul government officials overruled him and enacted a closing order for the whole city, including schools, theaters, churches, and dance halls. The St. Paul Citizens' Committee—consisting of 15 physicians, church leaders, and community members who were appointed by Dr. Simon—which was concerned by the record of 218 new cases on November 5, as well as 36 deaths between November 4 and November 5, 1918, recommended this policy change (Figure 1).17 The number of new cases began to decline 10 days later, with only 24 new cases, and the next day, Dr. Simon reopened St. Paul businesses and churches.

Figure 1.

Influenza cases in St. Paul as recorded by the St. Paul Health Department in the St. Paul Daily News, 1918–1919

a Cases were not uniformly reported on Sundays, so Monday's data may be inflated.

Minneapolis and St. Paul both attempted to combat influenza by limiting crowding in places with restricted access to fresh air. Both cities enacted streetcar regulations aimed to keep the air in the streetcars fresh by mandating open windows and limiting the number of passengers to 84 (streetcars had a seating capacity of 46).5,17,18 Because the measure limiting the number of car passengers, implemented on October 26 in St. Paul, was deemed successful, Minneapolis enacted a similar regulation on October 30.17 As an experiment, Dr. Bracken also proposed that St. Paul regulate the business hours of stores and theaters to keep streetcar congestion to a minimum. Once again, Minneapolis followed St. Paul's example on October 16, 1918, by regulating the hours of retail stores, office buildings, and wholesale stores.19

There were several complaints that the mandate in Minneapolis to keep three streetcar windows open at all times caused people to get sick due to winter colds. A compromise was reached by Dr. Guilford allowing streetcars with heating and ventilation systems to close their windows once the temperature dropped to 32 degrees Fahrenheit.20

St. Paul also targeted elevators as places where influenza could easily be transmitted due to the tight quarters and limited fresh air. Buildings with fewer than six stories were no longer permitted to use their elevators.21

Public response to community containment disease

The measures used to contain influenza greatly affected the day-to-day lives of citizens. While some accepted the changes imposed on them, others protested regulations that they considered unfair. Some called for more stringent methods, while others blatantly broke the new rules that were intended to protect them.

The closing of public places in Minneapolis was announced in advance, so people rushed to complete those activities that would soon be banned, resulting in the very same crowded conditions the ban sought to prevent. “Downtown theaters were packed last night with patrons who took advantage of their last chance to see a performance until the ban is lifted.”22 While some St. Paul citizens were relieved that Dr. Simon initially pledged to keep public places open, others felt this was wrong. “Fear of influenza contagion in crowded places has reduced the patronage of St. Paul motion picture theaters by nearly half, according to reports to Dr. H.M. Bracken.”23

Many sporting organizations responded negatively to closing orders. For example, in November 1918, the bowlers of St. Paul drew up a petition that requested permission to begin bowling again.24 Minneapolis football teams chose to ignore the ban and attempted to play against each other in front of large crowds. Police were called in to disperse the crowds and halt the games.25 Minneapolis teams found a way to play despite the closing order. Because Minneapolis high school football games were banned, practice games were scheduled with St. Paul teams.26 Several establishments serving alcohol and food deliberately broke the closing order to continue their regular business. “One saloon was discovered with the back door route open.”27

The elevator regulations in St. Paul were particularly unpopular. “Some of the downtown hotels objected to stopping their elevators, saying that they would lose guests. This caused a change in the ruling to permit hotel elevators and those in apartment houses to operate.”28 Many insisted it was unhealthy for the sick to be forced to climb stairs in their impaired state, while others felt concerned that people would be shut off from fresh air if they were not allowed to use their elevators. Consequently, the city compromised and all elevators were back in use starting November 9, 1918, although only one person per 5 square feet was permitted.29

The Hennepin County School Board (where Minneapolis is located) was exceptionally defiant to the closing order. The school board was concerned for the health of the students as well as the “12,000 dollars a day” that the closing orders cost because teachers continued to be paid, and extra school days would have to be added to the school year.30 Against the explicit orders of Dr. Guilford, and the pleading of several Parent-Teacher Association officers, the school board reopened schools on October 21, only to be shut down on the same day under threat of police action.31

In St. Paul, all influenza cases were supposed to be reported to a physician, who in turn was required to isolate the case in his or her own home and notify the health department. Several problems sprung up with these requirements that hampered surveillance, the care of patients, and protecting people from getting sick. For one, both physicians and patients were often hesitant to bring attention to cases. “Physicians are not reporting their cases to prevent homes from being quarantined.”21 (Note: At the time of the 1918 influenza pandemic, the separation of the ill from the general population, what is now referred to as isolation, was termed “quarantine.”) The ill also sought to evade isolation in their homes by not seeking medical attention, or only seeking medical attention when they became gravely ill. “Hundreds of persons in the city do not call for medical assistance until the second, third, or fourth day and in many cases pneumonia already has developed when medical attention is first given.”29 Staffing shortages made isolation even less desirable. Because there were a limited number of inspectors to release houses from isolation, houses were not released promptly from isolation.32

Starting on November 15, St. Paul telephone operators went on strike. According to the Pioneer Press daily newspaper, “Less than one third the new cases [are] being reported to the health department,” as a result of the telephone strike.33 This strike not only affected the reporting of cases, but also isolation, as well as their release from such a measure.

After all of the difficulties involved in establishing isolation for each case, some flagrantly disobeyed the isolation orders altogether. “Disregard of the city quarantine yesterday caused the arrest of one man who insisted on taking his child from the city hospital before the patient was ready to be discharged. The mother and father and the child later were found mingling with other persons in the neighborhood.”29

INFECTION CONTROL AND VACCINATION

In addition to closing public places and isolating cases in their homes, both Minneapolis and St. Paul health departments took other steps to keep people from getting infected. The use of gauze masks, more stringent sanitation laws, and vaccination campaigns were deployed in this effort.

Directions for wearing the masks were issued to the public. “The outside of a face mask is marked with a black thread woven into it. Always wear this side away from the face. Wear the mask to cover the nose and the mouth, tying two tapes around the head above the ears. Tie the other tapes rather tightly around the neck. Never wear the mask of another person. When the mask is removed … it should be carefully folded with the inside folded in, immediately boiled and disinfected. When the mask is removed by one seeking to protect himself from the influenza it should be folded with the inside folded out and boiled ten minutes. Persons considerably exposed to the disease should boil their masks at least once a day.”21 However, there was inconsistent advice on the use of gauze masks. Dr. Bracken, of the State Board of Health, advocated the wearing of masks, though he did not wear one himself, saying, “I personally prefer to take my chances.”34

Medical students working in clinics in each district of St. Paul distributed gauze masks.12 But the Citizens' Committee rejected an ordinance requiring the wearing of masks at all times, even though, “All physicians were united in the opinion that the gauze covering should be worn in hospitals or in the presence of doubtful cases.”35 Despite the lack of official orders requiring the wearing of masks and Dr. Bracken's unclear message, many people sought out masks for themselves. The Northern Division of the American Red Cross manufactured tens of thousands of masks. Minneapolis ordered 15,000 masks from the Red Cross on October 1, 1918.36 These masks were used by nurses in schools and hospitals, doctors, hospital visitors, and those suspected of being infected with influenza.37

As the number of cases increased in St. Paul, employers sought ways to keep their workers healthy and productive. Several companies requested masks to distribute to their workers. Despite the thousands of masks provided by the Red Cross, still more were needed to fulfill the demand. The Citizens' Committee suggested that companies ask their female employees to fabricate masks for all their employees.21 St. Paul introduced new sanitation laws that called for the sterilization of dishes and cups in restaurants and bars, and the banning of roller towels and common drinking cups in public restrooms.38

At least two different vaccines were administered in Minneapolis-St. Paul, neither of them effective as neither actually contained influenza virus. One made by bacteriologists at the University of Minnesota was purported to prevent pneumonia.39 The Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, made another vaccine that was intended to prevent both pneumonia and influenza.40 This latter vaccination was composed of Streptococcus pneumoniae types I, II, and III, S. pneumoniae group IV, hemolytic streptococci, Staphylococcus aureus, and “influenza bacillus.”41

Military personnel as well as civilians were inoculated beginning as early as October 4, 1918.37 Both city health departments purchased vaccine and distributed it to physicians at no charge to encourage widespread use. In Minneapolis, people desiring the vaccine “thronged” the offices of doctors hoping to be vaccinated, and in St. Paul it was reported that “thousands of persons have been inoculated.”39,42 Some physicians took advantage of their access to vaccine and the public's fear of influenza. According to St. Paul's Citizens' Committee, it was discovered that “a few physicians were charging a fat fee for inoculations.”29 This was particularly disturbing as the vaccinations were supplied to the physicians for free.

COMMUNICATIONS

Postal workers, Boy Scouts, and teachers were enlisted to provide educational materials to the public and to teach health precautions. Mail carriers distributed educational materials on their routes. Boy Scouts distributed posters to stores, offices, and factories in downtown Minneapolis.22 Minneapolis teachers who were put out of work by the closing of schools were asked to volunteer for a health education campaign. The main goals of the campaign were to get rid of shared drinking cups, which were the precursor of the water fountain, as well as the roller towels, which were used to dry hands after washing.43 St. Paul teachers were sent “to ascertain the plight of families worst affected by the epidemic.”28 This was accomplished through a canvas of homes where the teachers learned if anyone was sick, needed to see a physician, or needed food.27 St. Paul set up a public kitchen, a children's home, and an emergency hospital for these cases.21

Limitations

Although the two cities chose different methods of disease containment, determining which method was more successful is challenging. Information on cases in both cities depended on ill individuals seeking the attention of physicians, who were in short supply. The physicians were then required to report the number of new cases each day to their city health department. The city then reported the total number of cases to the newspapers, which published the number of new cases and deaths each day. This chain of information left much room for error and possible falsification.

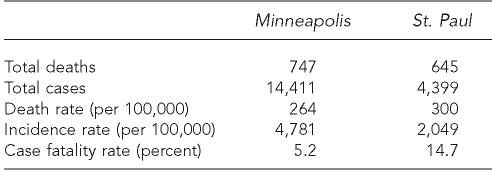

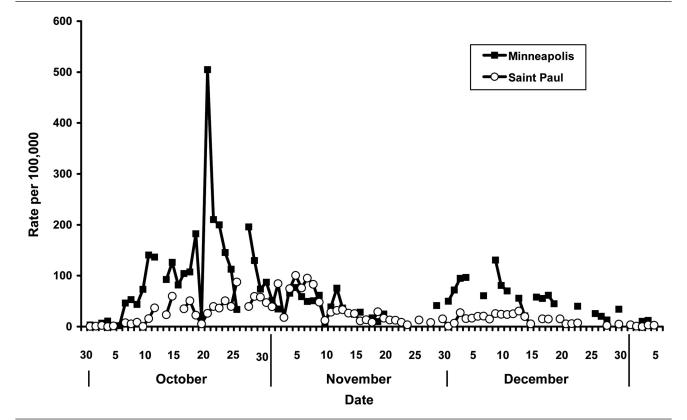

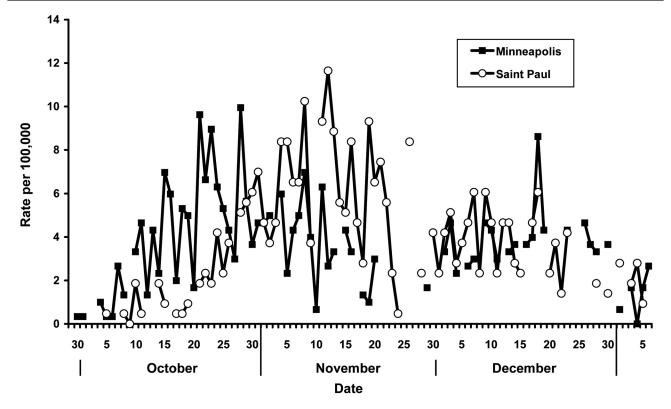

Because St. Paul chose to utilize isolation and Minneapolis did not, case reporting varied greatly between the two cities. Individuals with influenza who had their status reported in St. Paul had to endure isolation until they were released with a physician's approval. This may have discouraged people from seeking the attention of physicians, and thus being reported—an undesired consequence of enforced isolation (Table). Because those with influenza were not isolated in Minneapolis, more people might have felt comfortable seeking medical attention. This could explain why St. Paul had such a high case fatality rate compared with Minneapolis (Table, Figures 2 and 3).

Table.

Minneapolis and St. Paul influenza cases and deaths, September 30, 1918, to January 6, 1919

Figure 2.

Influenza case rates per 100,000, Minneapolis and St. Paul, 1918–1919

a Cases were not uniformly reported on Sundays, so Monday's data may be inflated.

Figure 3.

Daily death rates per 100,000, Minneapolis and St. Paul, 1918–1919

a Cases were not uniformly reported on Sundays, so Monday's data may be inflated.

CONCLUSION

Several factors impede direct comparisons of the two cities' approaches. The cities border each other and residents travel back and forth. Although the containment philosophies differed greatly, in reality St. Paul government officials overruled public health, and schools and public gathering places were closed in both cities for varying lengths of time. Although the effects of isolation vs. closure of public places cannot be specifically determined, other lessons can be learned from what happened in 1918. Many steps could have been taken to prevent illness and save lives. Prior planning, clear orders, as well as consistent and transparent advice and information to the public may have made a significant difference in the number of cases and deaths due to influenza in 1918.

There was a paucity of planning for a health emergency when influenza first appeared. While the actions that the two city health departments took to stem the spread of influenza align closely with current pandemic plans, health officials had the disadvantage of trying to conceive and realize plans during a health crisis. Many current recommendations were implemented, including the use of masks, the use of vaccines (albeit ineffective ones), increasing the stringency of sanitation measures, limiting crowding in public places, and trying to coordinate hospitals, nurses, physicians, and medical students to maximize resources. As part of maximizing human resources during an influenza pandemic, it is imperative that the safety of health-care workers is insured. The number of nurses and physicians who fell ill and even died as a result of assisting in the fight against the pandemic scared other nurses and physicians away.

Had these ideas been generated prior to such a large emergency, several problems could have been averted. The debates and disagreements between different public officials and health agencies, as with the Hennepin County School Board and the Minneapolis Health Department or between the Minneapolis Health Department and the St. Paul Health Department, could have been discussed in advance. Supplies could have been stockpiled, business leaders and community members could have provided input on controversial disease containment policies, and medical students could have been put to work in hospitals and communities that lacked physicians. Unfortunately, these disputes arose and continued throughout the pandemic.

Clear authority and management by public health officials were generally lacking at the federal and state levels. It was almost as if the fear of using their authority led Surgeon General Blue and Dr. Bracken to fail to take decisive action. Surgeon General Blue suggested to Dr. Bracken, and all other state health officials, “the advisability [of] discontinuing all public meetings, closing all schools and places of public amusement on appearance of local outbreaks.”44 Because this was merely a suggestion, and local outbreaks were not defined objectively, Blue's urgent telegram had no effect.

On the state level, Dr. Bracken acknowledged that the St. Paul Health Department “followed his advice” to not close public places, and went on to say that St. Paul, “has the power to do the opposite any time it wants to.”11 This statement forced local health departments to define their own rules while attempting to decipher conflicting messages from the state and federal level.

Because clear orders were not being given to public health officials, the public in turn was not receiving transparent and consistent advice and information. Should the public wear masks? Why was it allowable to be next to someone in a streetcar and not in an elevator? Why were church services closed while Red Cross workers gathered in crowded conditions in those very same churches? Was influenza a life-threatening condition, or was panic the most dangerous element of the influenza pandemic? In Minneapolis and St. Paul. there was no single message on any of these issues. In many cases, the public had to decide for itself. In which case, the effect of the messages that were communicated only served to contradict each other.

In reviewing this history, some lessons stand out. Recent analyses of nonpharmaceutical interventions during 1918 indicate cities in which multiple interventions were implemented early in the pandemic fared better.45 Of primary importance is developing a plan ahead of time that incorporates all levels of government health infrastructure and describes clear lines of responsibilities and roles. Plans for surge capacity and community containment must be discussed with stakeholders and consensus must be achieved.

Further, general approaches should be put forth for public comment and approval. The public health benefit of isolation should be weighed against the possibility that some people would be discouraged from seeking care. Clear explanations of the reason for isolation, generous employer support, and providing food, medicine, and social service to those in isolation may mitigate fears and increase cooperation. The public must also be educated about the reasoning behind other health measures (i.e., closures), should those methods be implemented.

Approaches and plans should be based on scientific data whenever possible, and include input from ethicists. Unlike in 1918, a pandemic influenza vaccine will likely be available today, albeit four to six months after the pandemic starts. But similar to 1918, the challenge will be designing an orderly and ethical distribution of a scarce commodity. Further, experts in risk communication should assist in developing messages that are scientifically accurate, understandable, clear, and useful. Finally, we need to take careful note of local and national lessons from the past so we do not repeat them.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barry JM. The great influenza: the epic story of the deadliest plague in history. New York: Penguin; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.State Board of Health and Vital Statistics of Minnesota. Eighth biennial report 1918–1919. Minneapolis: State Board of Health and Vital Statistics of the State of Minnesota; 1920. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Spanish Influenza gains headway here. Minneapolis Tribune 1918 Oct 1; 8.

- 4. Influenza gains slowly in city. Minneapolis Tribune 1918 Oct 10; 1,8.

- 5. Influenza gains among civilians. Minneapolis Tribune 1918 Oct 9; 1,7.

- 6. Editorial. Minneapolis Tribune 1918 Oct 3; 16.

- 7. Sailors may attend influenza patients. Minneapolis Tribune 1918 Nov 3; 4.

- 8. Henry Bracken to Rupert Blue, 1918 Nov 13, Minnesota Department of Health Correspondence and Miscellaneous Records, 1895–1954, Minnesota Historical Society.

- 9. Henry Bracken to Rupert Blue, 1918 Nov 2, Minnesota Department of Health Correspondence and Miscellaneous Records, 1895–1954, Minnesota Historical Society.

- 10. Henry Bracken to Dr. Merritte W. Ireland, 1918 Nov 16, Minnesota Department of Health Correspondence and Miscellaneous Records, 1895–1954, Minnesota Historical Society.

- 11. Business hours may be changed to curb epidemic. Minneapolis Tribune 1918 Oct 15; 1,10.

- 12. Lid on tomorrow includes schools. St. Paul Pioneer Press 1918 Nov 5; 6.

- 13. 150 cases of influenza in Minneapolis. Minneapolis Tribune 1918 Sep 30; 1.

- 14. Mill City closed. St. Paul Pioneer Press 1918 Oct 12; 1,6.

- 15. Doctors propose drastic lid be clamped on city. Minneapolis Tribune 1918 Oct 11; 1,2.

- 16. Clash over school order due Monday. Minneapolis Tribune 1918 Oct 20; 1.

- 17. Push grip fight. St. Paul Pioneer Press 1918 Oct 30; 1.

- 18. Epidemic controlled in city's army camps car crowds, 558 pupils stricken. Minneapolis Tribune 1918 Oct 29; 10.

- 19. Trade hours set to stem Spanish Influenza here. Minneapolis Tribune 1918 Oct 16; 1,2.

- 20. Ban on until deaths decrease to 7 a day. Minneapolis Tribune 1918 Nov 10; 14.

- 21. Sweeping order against influenza in effect here today. St. Paul Pioneer Press 1918 Nov 6; 1,7.

- 22. Influenza lid clamped tight all over city. Minneapolis Tribune 1918 Oct 13; 1,10.

- 23. See less influenza. St. Paul Pioneer Press 1918 Oct 15; 8.

- 24. Pins will fall. St. Paul Pioneer Press 1918 Nov 17; 7.

- 25. “Flu” order stops park grid games. Minneapolis Tribune 1918 Oct 14; 18,12.

- 26. High school games neither on nor off. Minneapolis Tribune 1918 Oct 15; 18,12.

- 27. Fail to report grip. St. Paul Pioneer Press 1918 Nov 8; 10.

- 28. Plan survey of influenza cases. St. Paul Pioneer Press 1918 Nov 7; 1.

- 29. All lifts to run. St. Paul Pioneer Press 1918 Nov 9; 1,7.

- 30. School chiefs face arrest or injunction, city officials to use law as directors defy influenza ban. Minneapolis Tribune 1918 Oct 21; 1,2.

- 31. Guilford wins fight to keep schools shut. Minneapolis Tribune 1918 Oct 22; 1.

- 32. Shows open today. St. Paul Pioneer Press 1918 Nov 15; 1.

- 33. Influenza relief work disrupted as a result of telephone strike. St. Paul Pioneer Press 1918 Nov 16 1.

- 34. Influenza lid to go on city today. St. Paul Pioneer Press 1918 Nov 4; 1,3.

- 35. Speed grip fight. St. Paul Pioneer Press 1918 Nov 2; 1.

- 36. Influenza spread held slight here. Minneapolis Tribune 1918 Oct 2; 1,4.

- 37. Influenza halts “U” opening to all but S.A.T.C. Minneapolis Tribune 1918 Oct 5; 1,22.

- 38. Cafes and bars hit by grip ban. St. Paul Pioneer Press 1918 Dec 14; 1.

- 39. Serum to be issued. St. Paul Pioneer Press 1918 Oct 19; 6.

- 40. Epidemic statistics show decline in city. Minneapolis Tribune 1918 Oct 25; 15.

- 41.Rosenow EC. Prophylactic inoculation against respiratory infections during the present pandemic of influenza. Preliminary report. JAMA. 1919;72:31–4. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Epidemic brings mercy problems. St. Paul Pioneer Press 1918 Nov 17; 1.

- 43. Teachers released for school closing period. Minneapolis Tribune 1918 Oct 15; 11.

- 44. Telegram from Rupert Blue to Dr. Henry Bracken, 1918 Oct 6, 6:49 pm, Minnesota Department of Health Correspondence and Miscellaneous Records, 1895–1954, Minnesota Historical Society.

- 45.Hatchett RJ, Mercher CE, Lipsitch M. Public health interventions and epidemic intensity during the 1918 influenza pandemic. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2007;104:7582–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610941104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]