INTRODUCTION

Pregnancy and infections are no longer inevitable consequences of having sex. Infections are covered in other articles in this series; this article deals with unwanted pregnancy and its prevention. Currently, only 2,290 conceptions arise from around 2 million daily sexual acts (Box 1).

Few women now breastfeed for long in Western society; women experience around 450 menstrual cycles in their reproductive careers compared to about 160 formerly with repeated births and prolonged lactational amenorrhoea.1 With small family sizes the use of contraception dominates women's and men's reproductive lives.

Technology has come a long way since Fallopio recommended the use of a linen sheath in 1564. The vulcanization of rubber in 1839 provided the technology for the development of latex condoms. However, modern contraceptive methods are not perfect and individuals often choose a method as the ‘least worst’ option.2

CONTRACEPTION

Contraception has been free on the NHS since 1974. Uptake of contraception in Britain is high—74% of women of reproductive age use some form of contraception, and most of those not using contraception have reasons (e.g. not in a heterosexual relationship, trying to conceive, already pregnant, abstinence from sex or thought to be infertile).3 The crucial question is how consistently people use contraception. The terms ‘typical use’ and ‘perfect use’ have been coined and efficacy figures are now expressed for both; there is a big difference between the two for condoms, for instance, but no difference for a method such as a subdermal implant where there is no reliance on daily actions such as pill taking or action to be taken at the time of intercourse.4 Also of great importance is whether couples make appropriate use of condoms in addition to their chosen method (dual protection) when they are in new relationships or have more than one partner in this age of increasing sexually transmitted infection/HIV prevalence. It needs to be emphasized to those consulting us that many methods of contraception give little or no protection against infection. Paradoxically, conflict between partners about use of condoms as a second method can exacerbate mistrust about fidelity.5

Box 1.

Daily events in England and Wales

| Number of daily events (England & Wales) | |

|---|---|

| Acts of heterosexual coitus in women* | 2 million |

| Conceptions26 | 2,290 |

| Abortions | 510 |

| Births | 1,780 |

Based on a mean coital frequency for women aged 16-44 of five times in four weeks34 and a mid-2005 female population aged 16-44 of 11 million

Latex condoms have been supplemented by condoms made from polyurethane. The latter unfortunately do not have such a good track record with respect to breakage rates as the former6 but have the advantages of being easier to don, are odourless, non-allergenic, allow more sensation, transmit heat and are not affected by oil-based lubricants.

The long-used spermicide nonoxinol-9 is now being phased out for two reasons. First, there is no evidence to show it aids efficacy with condoms.7 Second, we now know that its surfactant effect can damage lower genital tract epithelial surfaces and thereby increase the risk of acquisition of infections, including HIV.8 An urgent search is on for non-surfactant spermicides with microbicidal activity and also for pure microbicides to protect those wanting to achieve pregnancy.9

It is now more than four decades since the pill was launched. It has been one of the most revolutionary medicines in terms of its social effects and perhaps the most intensively researched drug in history,10 not to mention being the most popular method of contraception since records began. Over the years there have been new pills brought onto the market, often with few clinical differences to existing formulations. A recent change in pill-taking regimen has been that women now often run several or all packets together to reduce bleeding days and menstrual cycle-related symptoms: this is termed extended use of the pill.11

We have had other hormonal products introduced, particularly using progestogens alone, and although nothing has changed people's lives to the same extent as the pill, these products have greatly improved compliance (concordance). Special mention should be made of subdermal implants: the currently available product is an etonogestrel implant with a lifespan of three years.12 An ethinylestradiol/etonogestrel vaginal ring is available in many countries, but will probably not become available in the UK until 2008.13 Another novel product has been an ethinylestradiol/norelgestromin transdermal patch which delivers the hormones over a period of one week and is used cyclically three weeks out of four (like the combined pill).14 The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system has enjoyed massive popularity, with figures for annual units prescribed by general practitioners in England alone as high as 76,000.15

Despite widespread availability of contraception through different outlets, including pharmacies, it is estimated that almost half of all pregnancies in England are unintended.16 Access to services can be improved: on-the-spot pregnancy testing, same day emergency contraception and access to contraceptive services within two working days are now recommended.16 The full range of contraceptive methods, including long-acting methods such as injections, implants and intrauterine devices, must be available in every area. It needs to be understood, particularly by commissioners of services, that long-acting reversible methods are more cost-effective than the combined oral contraceptive pill or condoms.17 Subdermal implants and the copper intrauterine device are the most cost-effective long acting reversible methods.

STERILIZATION

It is staggering to recall that the legality of vasectomy was only clarified when Philip Whitehead's 1972 Private Members' Bill was enacted. Sterilization is popular in older age groups: 21% of women and 29% of men aged 45-49 have been sterilized.3 General practitioners and private clinics play a significant part in service delivery; it is estimated that one third of vasectomies are performed outside NHS hospital and community clinic settings.18 The popularity of female sterilization has been on the decline since 1996 and it is no coincidence that the launch of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system immediately preceded this trend. It is now known, and is surprising to many, that long acting reversible methods can be more effective than female sterilization.4 In addition, vasectomy is 10 times more effective, 20 times less likely to be associated with major complications and one third of the price compared to female sterilization.19 Nowadays, most gynaecologists are declining to put women on waiting lists for female sterilization unless they have first tried long-acting reversible methods.

EMERGENCY CONTRACEPTION

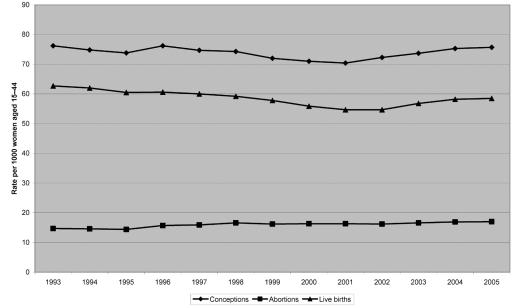

In the 1970s the concept of using hormones after sex was introduced, now called emergency contraception. These work prior to implantation of the fertilized egg. The products used have been refined over the years; progestogen-only methods are now widespread, avoiding the nausea and vomiting induced by oestrogens. In the UK, emergency hormonal contraception became available over-the-counter in addition to by prescription in 2001; since then, provision by pharmacies has increased from 20% to 45%.3 The concept of advance provision of emergency contraception has been introduced so that women do not have to go searching for it at the time of need. Some moralists have been concerned that easy availability of emergency contraception will lead to abandonment of regular contraception. US studies show that direct access to emergency contraception through pharmacies and advance provision resulted in no compromised contraceptive use or sexual behaviour compared to those receiving conventional services through clinics.20 No reduction in use of regular contraception was seen in the UK following the introduction of over-the-counter emergency contraception.21 However, despite theoretical predictions that widespread use of emergency contraception would lead to a decrease in the abortion rate,22 this has not occurred since a licensed product became available in 1984 (Figure 1), nor has it been shown in any study to date.23 Only 5% of women of childbearing age employ emergency hormonal contraception in the UK in any year; many more women would need to use this method and repeat it more times to impact on unintended pregnancy rates.24

Figure 1.

Conception, abortion and general fertility rates in England & Wales

FUTURE METHODS

One of the principal remaining research areas is male contraception. The most promising technique is the use of progestogens to suppress follicle stimulating and luteinising hormones with testosterone supplementation.25 Progress is painfully slow, however, despite huge efforts on the part of a small number of researchers.

CONCEPTIONS

Following an increase immediately after the 1995 ‘pill scare’ and then a slow decline, the conception rate has been on the increase in the UK, with live births following this temporal trend quite closely (Figure 1). In 2005 there were an estimated 837,000 conceptions in England and Wales, 22% of which ended in induced abortion.26 Daily figures are shown in Box 1. In the under-16 age group there were 7,917 conceptions in 2005, of which 57% ended in abortion.26 Despite lurid media headlines alleging irresponsible behaviour of young people, the conception rate in under-16s declined from 9.0 per 1000 in 1998 to 7.8 in 2005. During the last 15 years there has been a trend to relatively more conceptions in the 30-39 age group, which tallies with the tendency for women to defer childbearing.27

ABORTION

Recourse to induced abortion is a feature of all societies and is as old as humanity.28 It is never likely that abortion will be avoided by higher uptake of and compliance with contraception. Women in modern societies use abortion as an adjunct to contraception: when they do not use contraception with a new or pre-existing partner (being reunited or use of alcohol are classic contexts for passions taking over from the intellect) or when the method fails. Since the 1967 Abortion Act came into effect, the abortion rate has gradually risen from 5 to 18 per 1000 women aged 15-44 and is now plateauing (Figure 1); this is because service provision is now able to meet demand. Sepsis and death from illegal abortion are no longer seen. Induced abortion is now experienced by 35-40% of women by the time they reach the age of 45 and is the most common gynaecological procedure carried out on fit young women.

The proportion of women having subsequent abortions tends to increase after legalization of abortion and to reach a steady state within about 30 years.29 Currently 32% of women having abortions have had an abortion in the past.30 Post-abortion contraception should have proper care pathways mapped out; this is particularly important given the number of abortions now being performed in independent sector clinics considerable distances from women's homes.

Surgical abortion became much easier to perform when vacuum aspiration was introduced in Britain in the 1960s.31 The biggest revolution in abortion, however, was the development of antiprogestogens by Baulieu in France in the 1980s.32 Although medical abortion can be achieved using prostaglandins alone, in practice side effects limit their use. Use of mifepristone (formerly known as RU486) followed by lower dose prostaglandin has proved very effective and safe in inducing abortion. Since mifepristone was licensed in Britain in 1991, the proportion of abortions performed medically has risen to 30%.30 Abortion is free to residents, providing that a woman's Primary Care Trust has commissioned an adequate service, and the proportion of abortions funded by the NHS has now risen to 87%.30 This has only been possible by creating increased capacity in the independent sector: 55% of NHS-funded abortions are now carried out by charitable organizations.

The earlier in pregnancy an abortion is performed, the lower the risk of complications and death.16 Women should be able to access an abortion within two weeks, and within a maximum of three weeks of initial contact with health care providers.16 The Department of Health has developed sexual health performance indicators in order that PCTs may monitor access to abortion services; progress has been made but there is still room for improvement in more than a third of PCTs.33

CONCLUSION

Having concentrated efforts on technology, we now need to further develop service networking, care pathways and easier access to allow women and men to control their fertility as they wish. Human behaviour being what it is, however, there will always be non-use of contraception, mishaps when using contraception, and requests for abortion. A non-judgmental approach to women and men in such predicaments by all health care professionals is essential.

This article is the fourth in a series of articles on sexuality and sexual health.

Competing interests The author has attended conferences with funding provided by various pharmaceutical companies. He was previously Clinical Director of bpas, one of two large charitable organizations providing abortion services in the UK.

References

- 1.Eaton SB, Pike MC, Short RV, et al. Women's reproductive cancers in evolutionary context. Q Rev Biol 1994;69: 353-67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh J, Lythgoe H, Peckham S. Contraceptive Choices—Supporting Effective Use of Methods. London: Family Planning Association, 1996

- 3.Taylor T, Keyse L, Bryant A. Contraception and Sexual Health, 2005/06. London: Office for National Statistics, 2006

- 4.Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception 2004;70: 89-96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woodsong C, Koo HP. Two good reasons: women's and men's perspectives on dual contraceptive use. Soc Sci Med 1999;49: 567-80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gallo MF, Grimes DA, Lopez LM, Schulz KF. Non-latex versus latex male condoms for contraception. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006: CD003550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.WHO/CONRAD Technical Consultation on Nonoxynol-9. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Hillier SL, Moench T, Shattock R, Black R, Reichelderfer P, Veronese F. In vitro and in vivo: the story of nonoxynol 9. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2005;39: 1-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta G. Microbicidal spermicide or spermicidal microbicide? Eur J Contracep Reprod Health Care 2005;10: 212-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marks LV. Sexual Chemistry—A History of the Contraceptive Pill. Yale: Yale University Press, 2001

- 11.Archer DF. Menstrual-cycle-related symptoms: a review of the rationale for continuous use of oral contraceptives. Contraception 2006;74: 359-66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards JE, Moore A. Implanon: a review of clinical studies. Br J Fam Planning 1999;24(Suppl): 3-16 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oddsson K, Leifels-Fischer B, de Melo NR, et al. Efficacy and safety of a contraceptive vaginal ring (NuvaRing) compared with a combined oral contraceptive: a 1-year randomized trial. Contraception 2005;71: 176-82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burkman RT. The transdermal contraceptive system. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;190: S49-S53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NHS Contraceptive Services England 2005-06. Leeds: The Information Centre, 2006

- 16.Medical Foundation for AIDS & Sexual Health. Recommended Standards for Sexual Health Services. London: MedFASH, 2005

- 17.National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health. Long-Acting Reversible Contraception (NICE Guideline). London: RCOG, 2005

- 18.Rowlands S, Hannaford P. The incidence of sterilization in the UK. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2003;110: 819-24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brechin S, Bigrigg A. Male and female sterilization. Curr Obstet Gynaecol 2006;16: 39-46 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raine TR, Harper CC, Rocca CH, et al. Direct access to emergency contraception through pharmacies and effect on unintended pregnancy and STIs: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005;293: 54-62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Impact on contraceptive practice of making emergency hormonal contraception available over the counter in Great Britain: repeated cross sectional surveys. BMJ 2005;331: 271-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trussell J, Stewart F, Guest F, Hatcher RA. Emergency contraceptive pills: a simple proposal to reduce unintended pregnancies. Fam Plan Perspect 1992;24: 269-73 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raymond EG, Trussell J, Polis CB. Population effect of increased access to emergency contraceptive pills: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol 2007;109: 181-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abuabara K, Becker D, Ellertson C, Blanchard K, Schiavon R, Garcia SG. As often as needed: appropriate use of emergency contraceptive pills. Contraception 2004;69: 339-42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wenk M, Nieschlag E. Male contraception: a realistic option? Eur J Contracep Reproduct Health Care 2006;11: 69-80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Conceptions in England and Wales, 2005. Health Stat Q 2007;33: 64-8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Botting B, Dunnell K. Trends in fertility and contraception in the last quarter of the 20th century. Pop Trends 2000;100: 32-9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.David HP. Abortion policies. In: Hodgson JE, ed. Abortion and Sterilization: Medical and Social Aspects. London: Academic Press, 1981: 1-40

- 29.Rowlands S. More than one abortion. J Fam Plan Reprod Health Care 2007:33: 155-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abortion statistics, England and Wales: 2006. London: Department of Health; 2007

- 31.Kerslake D, Casey D. Abortion induced by means of the uterine aspirator. Obstet Gynecol 1967;30: 35-45 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baulieu EE. The Albert Lasker Medical Awards. RU-486 as an antiprogesterone steroid. From receptor to contragestion and beyond. JAMA 1989;262: 1804-14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Performance ratings, England, 2004/2005. London: Healthcare Commission, 2005

- 34.Johnson A, Wadsworth J, Wellings K, Field J. Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles. London: Blackwell Scientific, 1994