Abstract

Objective

Loss to follow-up threatens internal and external validity yet little research has examined ways to limit participant attrition. We conducted a systematic review of studies with a primary focus on strategies to retain participants in health care research.

Study Design

We completed searches of PubMed, CINAHL, CENTRAL, Cochrane Methodology Register, and EMBASE (August 2005). We also examined reference lists of eligible articles and relevant reviews. A data-driven thematic analysis of the retention strategies identified common themes.

Results

We retrieved 3,068 citations, 21 studies were eligible for inclusion. We abstracted 368 strategies and from these identified 12 themes. The studies reported a median of 17 strategies across a median of six themes. The most commonly reported strategies were systematic methods of participant contact and scheduling. Studies with retention rates lower than the mean rate (86%) reported fewer strategies. There was no difference in the number of themes used.

Conclusion

Available evidence suggests that investigators should consider using a number of retention strategies across several themes to maximize the retention of participants. Further research, including explicit evaluation of the effectiveness of different strategies, is needed.

Keywords: patient participation, patient dropouts, in-person follow-up, follow-up studies, cohort studies, systematic review

Loss to follow-up of research participants threatens the internal and external validity of a study[1;2]. The study results may be biased by differential dropout between comparison groups or by differences between those participants who drop out and those that continue to participate. Loss to follow-up also may threaten the generalizability of a study, as well as its statistical power. Despite these threats, little attention has been paid to the optimal methods of maintaining participants in a study.

Much of the existing literature on strategies to retain participants in research studies is limited to descriptions of ‘lessons learned’. For example, based on their experiences in studies of people over 65 years old, Cassidy et al (2001) suggested that personalized attention, empathy and support from study staff resulted in higher participant completion[3]. Shumaker et al (2000) similarly drew on their own experiences to outline approaches to promote retention including screening out those likely to not remain in the study and early identification and tracking of study participants who are poor or non-adherers[4].

Coday et al (2005) collected lessons learned from 14 NIH-funded behavioral change trials [5]. They elicited perceived barriers to participant retention and 61 retention strategies from the project staff and investigators from these trials. The retention strategies were categorized into eight themes which study personnel then ranked based on perceived effectiveness. The strategy category of flexibility followed by incentives, benefits and persistence were rated as most effective by the study personnel.

Davis et al (2002) completed a review of trials between 1990 and 1999 identifying 21 studies that included a description of retention strategies and retention rates[6]. The authors provided a table listing the trials rank-ordered based on the retention rate (specifics not provided) and suggested that those studies with higher retention were those using a combination of strategies. The paper combined discussion about retention and recruitment strategies as well as about studies with mail or telephone follow-up versus those with in-person visits.

In the existing literature, we could not identify any explicit evaluation of the effectiveness of retention strategies, such as a comparison of follow-up rates using different strategies. To help comprehensively synthesize strategies for participant retention in research studies and to evaluate areas for future methodological research in this field, we conducted a systematic review of studies which described strategies for maximizing retention for in-person follow-up.

METHODS

Searching and Study Selection

We sought English-language publications reporting research that described retention strategies for in-person follow-up and included actual retention rates. We reviewed only those published reports with a primary focus on retention strategies. We included studies that provided data on retention rates, described data from a primary study, and provided information regarding strategies used to retain participants. We searched PubMed (August 11, 2005), Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (August 8, 2005), the Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (CENTRAL) and the Cochrane Methodology Register (Issue 3, 2005), and EMBASE (August 11, 2005). The search strategies combined text words and controlled vocabulary words for concepts of ‘attrition’, ‘retention’, ‘patient dropouts’ and ‘loss to follow-up’. The specific search strategies are provided in Appendix I. We also examined the reference lists of eligible articles and relevant reviews [3;7–31].

All retrieved citations were screened independently by two authors to determine eligibility. Results of the search and screening processes were maintained in a citations database (ProCite, ISI, Berkley, CA).

Data Abstraction and Synthesis

Two reviewers abstracted information about the study, including design, location and target population and health condition. We also abstracted all retention strategies and retention rates at all follow-up time points. Abstracted data were entered into a relational database (Microsoft Access, Redmond, WA).

We completed a data-driven thematic analysis of the retention strategies[32]. Using an iterative, multi-step process, we reviewed all abstracted retention strategies to identify themes and to classify each strategy within these themes. Initially, two authors independently reviewed the strategies and identified themes. Second, a third author reviewed these independent results, reconciled differences and proposed a list of common themes. Third, this list of themes and categorization of strategies was discussed at a team meeting and we developed consensus on a final list of themes. Fourth, two authors independently re-reviewed the strategies and assigned each strategy to one of the themes from the final list. Finally, a third author adjudicated all assigned themes. Any remaining disagreements were discussed and resolved at a team meeting.

RESULTS

Review process

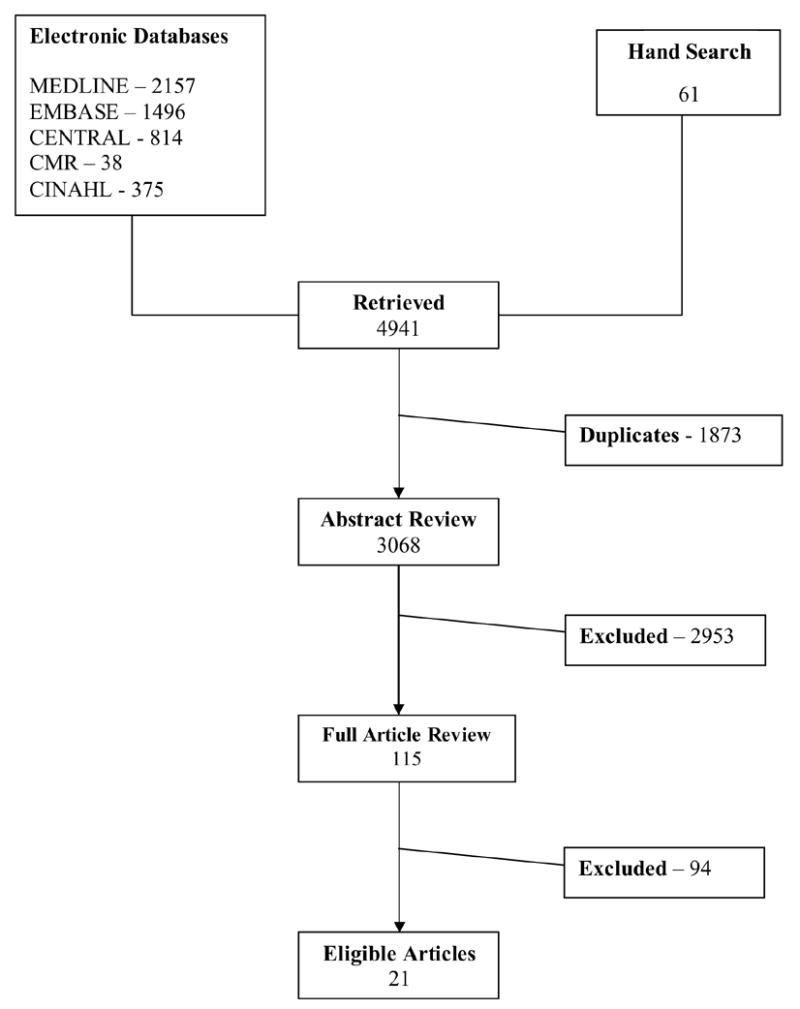

Our search identified 3,068 potentially relevant citations of which 115 were considered further at the full-text level. Of these 115, we excluded an additional 94 primarily because the article did not describe a primary study (e.g., article was a review or commentary) or because the article did not describe specific retention strategies. There were 21 articles that met our eligibility criteria. Figure 1 summarizes the results of our search and selection processes.

Figure 1.

Summary of Search and Screening Results

Study Characteristics

The 21 studies in this review included 18,782 participants (mean=894) (Table 1) [33–53]. Only one study was conducted entirely outside of the United States. Thirteen of the studies were randomized controlled trials and the remaining eight were prospective cohort studies. Of the trials, seven included behavioral interventions, four were of a drug intervention, two combined behavioral and drug interventions, and one involved a surgical intervention. Six of the studies examined substance abuse, with four of these including a behavioral or drug intervention. Other populations or health conditions included mothers and individuals with cancer, heart disease, and AIDS.

Table 1.

Summary of study characteristics

| Study | Study_type | Sample Size | Condition/Population | Demographics | Intervention | Number of Follow-up Visits* | Total length of Follow-up (months) | Retention Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Katz, 2001 | randomized controlled trial | 286 | new mothers | Mothers >=18 years old with no psychiatric diagnoses who had <5 prenatal visits during pregnancy or had prenatal care initiated in third trimester; predominantly unmarried; mostly African-American | behavioral program | 1 | 12 | 59 |

| Catlett, 1993 | prospective cohort | 145 | mothers | Mothers who gave birth to infants who weighed less than 1,500 grams | no intervention | 2 | 24 | 62 |

| Pappas, 1998 | randomized controlled trial | 211 | substance abuse/young urban people | Sixth-grade students at two inter-city schools | behavioral program | 2 | 12 | 70 |

| Parra-Medina, 2004 | randomized controlled trial | 189 | diabetes | Overweight adults >=45 years old living in rural, medically underserved communities; 80% African American; 47% had less than high school education | behavioral program | 3 | 12 | 82 |

| Hessol, 2001 | prospective cohort | 2628 | AIDS/women | HIV-positive women | no intervention | 1 | 60 | 82 |

| Motzer, 1997 | randomized controlled trial | 217 | cancer | Families of female breast-cancer patients | behavioral program | 1 | 10 | 83 |

| Desland, 1991 | prospective cohort | 92 | substance abuse | Heroine users; included self-referred heroine users and those identified by court | drug intervention | 5 | 12 | 84 |

| Mazzuca, 2004 | randomized controlled trial | 431 | arthritis/women | Obese women 45 – 64 years old who had unilateral knee osteoarthritis | drug intervention | 1 | 30 | 85 |

| Dilworth-Anderson, 2004 | prospective cohort | 202 | caregivers/African-American | African-Americans >65 years old living | no intervention | 1 | 60 | 87 |

| BootsMiller, 1998 | randomized controlled trial | 485 | substance abuse and psychiatric illness | Patients newly admitted to hospital for mental illness; 74% male, 77% African-American, mean age of 33 years old; 30% homeless, 47% had prior convictions | drug intervention | 5 | 24 | 88 |

| Miller, 1999 | randomized controlled trial | 187 | depression/elderly | Depressed elderly patients | drug and behavioral intervention | 1 | 88 | |

| Dennis, 2000 | prospective cohort | 25 | no specific disease/ethnic/racial minorities | Elderly African-Americans living in urban areas | drug and behavioral intervention | 1 | 3 | 88 |

| Dudley, 1995 | prospective cohort | 4954 | AIDS/gay and bisexual men | Homosexual and bisexual men18 – 70 years old in four urban areas | no intervention | 1 | 114 | 89 |

| Meyers, 2003 | prospective cohort | 195 | substance abuse/young people | Youth (mean age = 16 years old) in alcohol and drug treatment programs; 66% Caucasian, 66% male, 65% urban, 32% referred by court | no intervention | 2 | 6 | 92 |

| Bell, 1985 | randomized controlled trial | 3837 | heart disease | People who had at least one myocardial infarction | drug intervention | 3 | 36 | 92 |

| Froelicher, 2003 | randomized controlled trial | 2481 | heart disease | Patients who experienced depression and/or low social support following myocardial infarction; 66% male, 66% white, 53% high school education or less | behavioral program | 1 | 54 | 93 |

| Sprague, 2003 | randomized controlled trial | 440 | fractures | Patients at 24 centers worldwide who had fractures of the tibial shaft | surgery | 1 | 12 | 94 |

| Robles, 1994 | prospective cohort | 829 | substance abuse and pregnancy | Women >= 18 years old at fourth gestational month; included a group who had more than 3 drinks per week during the first trimester and a group who smoked two or more joints per month during first trimester; 53% non-Caucasian; average 12 years education; 73% earned less than $500/month | no intervention | 3 | 36 | 95 |

| Goldberg, 2005 | randomized controlled trial | 162 | weight loss | Overweight and obese adults 25–80 years old living in major metropolitan area | behavioral program | 3 | 18 | 96 |

| Bailey, 2004 | randomized controlled trial | 176 | cancer | Healthy women >=14 years old with cervical lesions | drug intervention | 1 | 48 | 99 |

| Desmond, 1995 | randomized controlled trial | 610 | substance abuse | Illegal opioid users treated in a methadone clinic | behavioral program | 1 | 12 | 99 |

number of follow-up visits with retention rate reported

No study explicitly compared the effectiveness of different retention strategies. The average follow-up time of the studies was approximately 30 months with a range from 3 months to 9.5 years. Nine of the studies included a total follow-up time of one year or less. Twelve studies reported retention rates for only one follow-up point at the end of the study; though the range among the studies was 1 to 5 visits (mean=2). The mean retention rate at the last, or only, follow-up time was 86% (range of 59% to 99%).

Synthesis of Retention Strategies

We abstracted 368 retention strategies from which we identified 12 themes. Table 2 lists the themes based on the order that the strategies would most likely be implemented. For instance, the theme ‘Community involvement’ is listed first as getting the community involved in the study, including in design issues such as retention strategies, could be initiated prior to the start of the study. ‘Study Identity’ follows ‘Community Involvement’ and includes strategies such as the creation and use of a study logo on t-shirts, calendars and all correspondence to create for the study participants a sense of identification with or belonging to a study. Although, many of the strategies could be classified across multiple themes we classified each strategy as belonging in one theme only. We maintained the data-driven themes rather than collapse categories. For instance, ‘Reminders’ were kept as a separate specific theme and not combined under ‘Contact and Scheduling Methods’, a category including systematic methods for maintaining patient contact.

Table 2.

Retention strategy themes

| Theme | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Community Involvement | Involve community in study design, recruitment and retention | Present pilot project idea to church leadership and congregation

Create community advisor panel and consult with panel for recommendations regarding protocol and participation |

| Study Identity | Create study identity for participants | Create a project identity by using similar colors and fonts on all study materials

Give participants a t-shirt printed with study logo |

| Study Personnel | Characteristics, training and management of study personnel | Assign one primary clinician to each participant

Encourage study personnel to show empathy towards subject’s personal situation in scheduling appointments/cancellations |

| Study Description | Explain study requirements and details, including potential benefits and risks, to participants | Inform subjects that they will be followed over time and specify the timetable and the methods that will be used to locate them

Offer a copy of a newspaper article or study brochure to each participant |

| Contact and Scheduling Methods | Use systematic method for patient contact, appointment scheduling and cohort retention monitoring | Mail a newsletter to participants that includes a message from PI, photos of project staff, and preliminary findings

Obtain multiple contacts for each participant, including 2contacts not residing with the participant |

| Reminders | Provide reminders about appointments and study participation | Mail reminder postcards to participants one week before appointment

Visit in-patients before discharge to remind them of out- patient follow-up plan |

| Visit Characteristics | Minimize participant burden through characteristics and procedures of follow-up study clinic | Offer flexible clinic appointments (early morning, evenings, and weekends)

Provide background music for restful atmosphere in clinic |

| Benefits of Study | Provide benefits to participants, and families, that are directly related to the nature of study | Provide free annual physical examination

Form educational and support groups for families and patients |

| Financial Incentives | Provide financial incentives or payment | Provide payment to families in control group ($20/visit/4visits)

Provide pharmacy gift certificate to participant at first follow-up visit ($25) |

| Reimbursement | Provide reimbursement for research-related expenses or tangible support to facilitate participation | Provide taxi fare or have staff member pick up study participants

Provide child care during visit |

| Non-Financial Incentives | Provide non-financial incentives or tokens of appreciation | Provide an inexpensive token of appreciation (e.g., coffee mug, pen, refrigerator magnet) to participant at each visit

Host holiday parties for study participants |

| Special Tracking Methods | Methods of tracking or dealing with hard-to-find or difficult participants | Conduct clinic and street outreach for lost to follow-up participants

Identify and address obstacles hindering participation for problem patients |

The largest number of strategies (n=123) was classified within the theme of ‘Contact and Scheduling Methods’. Eighty-six percent of studies reported using strategies from this theme which included systematic methods for patient contact, scheduling of appointments and monitoring of cohort retention. Specific strategies included obtaining updated contact information every two months [50] and making multiple attempts to contact subjects for complete data by phone and mail [43]. The theme ‘Visit Characteristics’ included the next highest number of strategies (n=57) and was also considered in 86% of the studies. This theme comprised strategies related to minimizing participant burden through the characteristics and procedures of the follow-up visit, such as offering to conduct the interview on the front porch or outside the home [40] and providing refreshments in the follow-up clinic [34].

Financial incentives were provided by eight studies. Eleven strategies involved payments for follow-up visits or interviews, including the provision of gift certificates. A specific dollar amount was provided for ten of these strategies with a range of $10USD to $50USD (median=$20USD). Two studies provided payments of $10USD or $20USD to family or friends for assistance in finding difficult to find study participants [35;39] and one reported a supplemental payment of $5 for resistant participants [52]. Finally, one study paid $5 for each urine sample provided [39]. The retention rate for those studies that reported using financial incentives was higher than for studies not reporting using financial incentives (mean 88% versus 85%, p=0.9).

There was a range of 3 to 42 strategies (median=17) and a range of 3 to 10 themes (median=6) per study (Table 3). No study reported strategies in all themes. Eight studies reported less than the mean retention rate of 86%. These studies had a mean retention rate of 76% with an average follow-up length of 22 months. The other 13 studies, with a mean retention rate of 92%, had a mean follow-up length of 35 months. The studies with retention rates below the mean reported using fewer strategies than those studies with a higher than mean retention rate (12 versus 21, p=0.05). These two groups of studies did not differ in the number of different themes (mean=6 for both). The small number of studies and the heterogeneity of their characteristics limits our ability to further examine relationships between retention strategies or themes and retention rates.

Table 3.

Number of strategies by theme

| Study | Community Involvement | Study Identity | Study Personnel | Study Description | Contact and Scheduling | Reminders | Visit Characteristics | Benefits of Study | Financial Incentives | Reimbursement | Non-Financial Incentives | Special Tracking Methods | Total Number of Strategies Per Study | Total Number of Themes Per Study | Retention Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Katz, 2001 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 6 | 59 | ||||||

| Catlett, 1993 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 62 | |||||||||

| Pappas, 1998 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 70 | ||||||||

| Hessol, 2001 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 29 | 10 | 82 | ||

| Parra-Medina, 2004 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 18 | 8 | 82 | ||||

| Motzer, 1997 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 17 | 6 | 83 | ||||||

| Desland, 1991 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 84 | |||||||||

| Mazzuca, 2004 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 5 | 85 | |||||||

| Dilworth-Anderson, 2004 | 1 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 35 | 7 | 87 | |||||

| BootsMiller, 1998 | 3 | 13 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 25 | 6 | 88 | ||||||

| Dennis, 2000 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 9 | 4 | 88 | ||||||||

| Miller, 1999 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 88 | ||||||||

| Dudley, 1995 | 1 | 13 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 25 | 7 | 89 | |||||

| Bell, 1985 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 29 | 6 | 92 | ||||||

| Meyers, 2003 | 13 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 23 | 7 | 92 | |||||

| Froelicher, 2003 | 7 | 3 | 13 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 42 | 9 | 93 | |||

| Sprague, 2003 | 3 | 8 | 5 | 2 | 18 | 4 | 94 | ||||||||

| Robles, 1994 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 16 | 8 | 95 | ||||

| Goldberg, 2005 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 5 | 96 | |||||||

| Bailey, 2004 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 13 | 8 | 99 | ||||

| Desmond, 1995 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 17 | 5 | 99 | |||||||

| Number (%) of Studies with Theme | 3 (14%) | 4 (19%) | 13 (62%) | 10 (48%) | 18 (86%) | 10 (48%) | 18 (86%) | 10 (48%) | 9 (43%) | 10 (48%) | 13 (62%) | 7 (33%) | |||

| Total Number of Strategies Per Theme | 6 | 5 | 38 | 22 | 123 | 19 | 57 | 24 | 19 | 20 | 23 | 12 | 368 | ||

DISCUSSION

Failure to retain study participants in a research study is an important methodological concern. Given the expense of conducing health care research, the limited financial resources to support such studies and the risks patients potentially incur from participation, efforts to reduce bias from loss to follow-up are an important research priority. Large overall loss to follow-up or differential loss to follow-up threatens the internal and external validity of studies and limits the ability to draw inferences. However, there is sparse evidence concerning strategies aimed at maximizing retention of study participants. We identified only 21 studies across all health domains and no study that explicitly evaluated retention strategies. We identified 368 strategies that were classified within 12 themes. The studies used a median of 17 strategies across a median of 6 themes. The most commonly reported strategies dealt with themes related to systematic methods of patient contact and scheduling procedures, and minimizing patient burden through modification of characteristics of the study visit or clinic.

Studies with lower retention rates (less than the mean rate of 86%) reported the use of fewer strategies than those studies with higher retention rates despite having a lower mean overall follow-up duration. The relatively small number of studies and their heterogeneity of the literature limited our ability to further quantitatively synthesize the results. Consequently, our best advice to investigators who are designing cohort retention protocols for studies with in-person follow-up is to use multiple strategies across multiple themes. A list of strategies abstracted from the 21 studies is available <insert hotlink>.

We are not the first to develop a list of strategies and themes. Davis et al (2002), in review of 21 community-based trials, identified 9 themes and noted that those studies with the highest retention rate appeared to use a combination of strategies[11]. Hunt and White (1998) chose to review four longitudinal studies to develop a list of general strategies to maximize retention [16]. Their four categories included some but not all of the same themes we identified: enrolment, consent and baseline activities; bonding; frequency of contact; staff characteristics; and incentives. Coday et al (2005) used principles of Social Cognitive Theory to identify 8 retention categories from the 61 strategies elicited from study staff[5]. Some of the retention themes are very similar to those identified in our review. However, we identified additional different sorts of themes, such as “Community involvement”, and also had narrower themes in some cases For instance, our theme of “Visit Characteristics” is very similar to the category “Be flexible” as well as the category “Give instrumental or tangible support” identified in the Coday study as both categories included offering more convenient visits, such as home visits. As another example, the data guided us to separate the strategies encompassing reimbursement, financial incentives, non-financial incentives which were combined by Coday et al. We identified similar strategies but we built on the findings of these earlier studies by systematically reviewing the literature across all health domains, incorporating all relevant study designs, to identify a larger and more comprehensive list of strategies and themes.

More research is needed in this field including explicit evaluation of the effectiveness of different cohort retention strategies. Given the need for all studies to retain participants, it may be more feasible and appropriate to focus on testing those retention strategies with higher costs, in terms of expense and research staff time. This research could include a comparison of the costs and benefits of different strategies. Finally, more papers on actual experiences with retention of participants in research studies should be published and study investigators should be encouraged to more explicitly report their retention strategies and retention rates. Adoption of standards for reporting retention strategies and rates would be helpful to improve the disclosure and consistency of these data.

Methods of recruiting participants also may be relevant for retaining participants. Consequently, research on recruitment strategies may be consulted. For instance, a recent Cochrane review of 15 controlled trials of strategies to improve the recruitment of study participants, categorized recruitment strategies into five types: (1) provision of information prior to invitation to join the study (pre-warning), (2) provision of extra information about study benefits and risks, (3) changes to the study design to account for patient preference, including not having a placebo study arm, (4) changes to the consent process and (5) incentives[54]. The authors noted that the results of a few studies suggest that financial incentives and provision of extra information are of some benefit. Similar to our review, the authors noted that the heterogeneity of the studies limited their ability to quantitatively synthesize the effect of specific strategies.

We acknowledge that our study has limitations. First, our efforts to classify retention strategies may have mis-classified some strategies. Second, given the significant heterogeneity of the studies we were not able to provide detailed quantitative analyses. This includes an inability to identify associations between the types of strategies, retention rate and the type of study population. Finally, we were able to abstract only the retention strategies as described in the reports of the studies and were unable to determine, for instance, the frequency or intensity of application of the strategies. Because of these limitations, we are unable to provide specific guidance on what works for whom or under what circumstances. Nevertheless, we have identified important relationships between the number of strategies used and retention rates.

Our study has some notable strengths. We built on earlier anecdotal examinations of retention strategies by systematically seeking and synthesizing studies addressing retention strategies. In addition, by classifying retention efforts into strategies and themes, and in identifying an association between number of strategies and retention rates, we can provide researchers with a guideline to plan cohort retention efforts in health care research studies.

Loss of study participants may threaten the power of a study and lead to bias. This common and important threat to validity has received very limited attention in the research literature. Use of a greater number of retention strategies from a wide variety of themes may improve study participant retention. However, further research is needed, including the explicit evaluation of the effectiveness of different strategies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rameswari Radhakrishnan for development of the relational database and data entry.

This research is supported by National Institutes of Health (Acute Lung Injury SCCOR Grant # P050 HL 73994-01). Dr. Needham is supported by a Clinician-Scientist Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Dennison is supported by the Mentored Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Award from the National Institutes of Health (K23 NR009193). The funding bodies had no role in the study design, manuscript writing or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Appendix 1 - Search Strategies

PubMed

((attrition[tiab] OR retention[tiab] OR patient dropouts[mh] OR “loss to follow-up”[tiab]) AND (minimize[tiab] OR strateg*[tiab] OR procedure*[tiab] OR technique*[tiab] OR method[tiab]) AND (longitudinal[tiab] OR follow-up[tiab] OR cohort studies[mh] or trial*[tiab]) AND eng[la] NOT review[pt] NOT (animals[mh] NOT humans[mh]))

CINAHL

[(AB ( attrition OR retention OR “loss to follow-up” ) Or TI ( attrition OR retention OR “loss to follow-up” ) OR MH patient dropouts) AND (TI ( strateg* OR minimize OR procedure* OR technique* OR method ) Or AB ( strateg* OR minimize OR procedure* OR technique* OR method )) AND (TI ( longitudinal OR follow-up OR trial* ) Or AB ( longitudinal OR follow-up OR trial* ) OR MH prospective studies)]

The Cochrane Library (CENTRAL, Cochrane Methodology Database)

#1 attrition OR retention OR “loss to follow-up” in Record Title or attrition OR retention OR “loss to follow-up” in Abstract or patient dropouts in Keywords in CENTRAL and CMR

#2 minimize OR strateg* OR procedure* OR technique* OR method in Record Title or minimize OR strateg* OR procedure* OR technique* OR method in Abstract in CENTRAL and CMR

#3 longitudinal OR follow-up OR trial* in Record Title or longitudinal OR follow-up OR trial* in Abstract or cohort studies in Keywords in CENTRAL and CMR

#4 #1 AND #2 AND #3

EMBASE

#1 attrition:ti,ab OR retention:ti,ab AND [english]/lim AND [humans]/lim

#2 (minimize:ti,ab OR strateg*:ti,ab OR procedure*:ti,ab OR technique*:ti,ab OR method:ti,ab) AND [english]/lim AND [humans]/lim

#3 (longitudinal:ti,ab OR ‘follow-up’:ti,ab OR ‘cohort analysis’/exp OR trial*:ti,ab) AND [english]/lim AND [humans]/lim

#4 #1 AND #2 AND #3

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Szklo M, Nieto FJ. Epidemiology - Beyond the basics. Boston, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman LM, Furberg CD, DeMets DL. Fundamentals of Clinical Trials. St Louis: Mosby; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cassidy EL, Baird E, Sheikh JI. Recruitment and retention of elderly patients in clinical trials: issues and strategies. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001 Spring;9(2):136–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shumaker SA, Dugan E, Bowen DJ. Enhancing adherence in randomized controlled clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 2000 Oct;21(5 Suppl):226S–32S. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(00)00083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coday M, Boutin-Foster C, Goldman Sher T, Tennant J, Greaney ML, Saunders SD, Somes GW. Strategies for Retaining Study Participants in Behavioral Intervention Trials: Retention Experiences of the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Ann Behav Med. 2005;29(2 Suppl):55–65. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2902s_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis LL, Broome ME, Cox RP. Maximizing retention in community-based clinical trials. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2002;34(1):47–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2002.00047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson RT, Ory M, Cohen S, McBride JS. Issues of aging and adherence to health interventions. Control Clin Trials. 2000 Oct;21(5 Suppl):171S–83S. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(00)00075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andreasson S, Parmander M, Allebeck P. A trial that failed, and the reasons why: comparing the Minnesota model with outpatient treatment and non-treatment for alcohol disorders. Scand J Soc Med. 1990 Sep;18(3):221–4. doi: 10.1177/140349489001800311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown DR, Fouad MN, Basen-Engquist K, Tortolero-Luna G. Recruitment and retention of minority women in cancer screening, prevention, and treatment trials. Ann Epidemiol. 2000 Nov;10(8 Suppl):S13–21. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00197-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colby SM, Lee CS, Lewis-Esquerre J, Esposito-Smythers C, Monti PM. Adolescent alcohol misuse: methodological issues for enhancing treatment research. Addiction. 2004 Nov;99(Suppl 2):47–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davis LL, Broome ME, Cox RP. Maximizing retention in community-based clinical trials. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2002;34(1):4–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2002.00047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farrington DP. Longitudinal research strategies: advantages, problems, and prospects. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1991 May;30(3):369–74. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199105000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Good M, Schuler L. Subject retention in a controlled clinical trial. J Adv Nurs. 1997 Aug;26(2):351–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997026351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hough RL, Tarke H, Renker V, Shields P, Glatstein J. Recruitment and retention of homeless mentally ill participants in research. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996 Oct;64(5):881–91. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hudson P, Aranda S, McMurray N. Randomized controlled trials in palliative care: overcoming the obstacles. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2001 Sep;7(9):427–34. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2001.7.9.9301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunt JR, White E. Retaining and tracking cohort study members. Epidemiol Rev. 1998;20(1):57–70. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ickovics JR, Meisler AW. Adherence in AIDS clinical trials: a framework for clinical research and clinical care. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997 Apr;50(4):385–91. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(97)00041-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leach MJ. Barriers to conducting randomised controlled trials: lessons learnt from the Horsechestnut & Venous Leg Ulcer Trial (HAVLUT) Contemp Nurse. 2003 Aug;15(1–2):37–47. doi: 10.5172/conu.15.1-2.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lilley K. Motivating patients to participate in clinical trials. Good Clin Pract J. 1999;6(5):21–5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marcellus L. Are we missing anything? Pursuing research on attrition. Can J Nurs Res. 2004 Sep;36(3):82–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKenzie M, Tulsky JP, Long HL, Chesney M, Moss A. Tracking and follow-up of marginalized populations: a review. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1999 Nov;10(4):409–29. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonfill X, Marzo M, Pladevall M, Marti J, Emparanza JI. Strategies for increasing women participation in community breast cancer screening. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(1):CD002943. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prinz RJ, Smith EP, Dumas JE, Laughlin JE, White DW, Barron R. Recruitment and retention of participants in prevention trials involving family-based interventions. Am J Prev Med. 2001 Jan;20(1 Suppl):31–7. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00271-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pruitt RH, Privette AB. Planning strategies for the avoidance of pitfalls in intervention research. J Adv Nurs. 2001 Aug;35(4):514–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sand EA. Longitudinal studies: social and psychological factors. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 1989;37(5–6):485–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shih WJ, Quan H. Testing for treatment differences with dropouts present in clinical trials--a composite approach. Stat Med. 1997 Jun 15;16(11):1225–39. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19970615)16:11<1225::aid-sim548>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shumaker SA, Dugan E, Bowen DJ. Enhancing adherence in randomized controlled clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 2000 Oct;21(5 Suppl):226S–32S. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(00)00083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trottier D, Kochar MS. Overcoming obstacles to recruitment and retention of subjects in clinical studies. J Clin Res Dreug Dev. 1994;8(1):49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Mechelen W, Mellenbergh GJ. Problems and solutions in longitudinal research: from theory to practice. Int J Sports Med. 1997 Jul;18( Suppl 3):S238–45. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-972721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson K, Rose K. Patient recruitment and retention strategies in randomised controlled trials. Nurse Researcher. 1998 Autumn;6( 1):35–46. doi: 10.7748/nr.6.1.35.s4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woolard RH, Carty K, Wirtz P, Longabaugh R, Nirenberg TD, Minugh PA, Becker B, Clifford PR. Research fundamentals: follow-up of subjects in clinical trials: addressing subject attrition. Acad Emerg Med. 2004 Aug;11(8):859–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2004.tb00769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dixon-Woods M, Agarwal S, Jones D, Young B, Sutton A. Synthesising qualitative and quantitative evidence: a review of possible methods. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005 Jan;10(1):45–53. doi: 10.1177/135581960501000110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bailey JM, Bieniasz ME, Kmak D, Brenner DE, Ruffin MT. Recruitment and retention of economically underserved women to a cervical cancer prevention trial. Appl Nurs Res. 2004 Feb;17(1):55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bell RL, Curb JD, Friedman LM, McIntyre KM, Payton-Ross C. Enhancement of visit adherence in the national beta-blocker heart attack trial. Control Clin Trials. 1985;6:89–101. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(85)90114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.BootsMiller BJ, Ribisl KM, Mowbray CT, Davidson WS, Walton MA, Herman SE. Methods of ensuring high follow-up rates: lessons from a longitudinal study of dual diagnosed participants. Subst Use Misuse. 1998 Nov;33(13):2665–85. doi: 10.3109/10826089809059344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Catlett AT, Thompson RJ, Jr, Johndrow DA, Boshkoff MR. Risk status for dropping out of developmental followup for very low birth weight infants. Public Health Rep. 1993 Sep-1993 Oct 31;108(5):589–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dennis BP, Neese JB. Recruitment and retention of African American elders into community-based research: lessons learned. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2000 Feb;14( 1):3–11. doi: 10.1016/s0883-9417(00)80003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Desland M, Batey R. High retention rates within a prospective study of heroin users. Br J Addict. 1991 Jul;86(7):859–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Desmond DP, Maddux JF, Johnson TH, Confer BA. Obtaining follow-up interviews for treatment evaluation. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1995 Mar-1995 Apr 30;12(2):95–102. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(94)00076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dilworth-Anderson P, Williams SW. Recruitment and retention strategies for longitudinal African American caregiving research: the Family Caregiving Project. J Aging Health. 2004 Nov;16(5 Suppl):137S–56S. doi: 10.1177/0898264304269725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dudley J, Jin S, Hoover D, Metz S, Thackeray R, Chmiel J. The Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study: retention after 9 1/2 years. Am J Epidemiol. 1995 Aug 1;142(3):323–30. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Froelicher ES, Miller NH, Buzaitis A, Pfenninger P, Misuraco A, Jordan S, Ginter S, Robinson E, Sherwood J, Wadley V. The Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Trial (ENRICHD): strategies and techniques for enhancing retention of patients with acute myocardial infarction and depression or social isolation. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2003 Jul-2003 Aug 31;23(4):269–80. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200307000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goldberg JH, Kiernan M. Innovative techniques to address retention in a behavioral weight-loss trial. Health Educ Res. 2005 Aug;20(4):439–47. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hessol NA, Schneider M, Greenblatt RM, Bacon M, Barranday Y, Holman S, Robison E, Williams C, Cohen M, Weber K. Retention of women enrolled in a prospective study of human immunodeficiency virus infection: impact of race, unstable housing, and use of human immunodeficiency virus therapy. Am J Epidemiol. 2001 Sep 15;154(6):563–73. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.6.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Katz KS, El-Mohandes PA, Johnson DM, Jarrett PM, Rose A, Cober M. Retention of low income mothers in a parenting intervention study. J Community Health. 2001 Jun;26(3):203–18. doi: 10.1023/a:1010373113060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mazzuca SA, Brandt KD, Katz BP, Lane KA, Bradley JD, Heck LW, Hugenberg ST, Manzi S, Moreland LW, Oddis CV, Schnitzer TJ, Sharma L, Wolfe F, Yocum DE. Subject retention and adherence in a randomized placebo-controlled trial of a disease-modifying osteoarthritis drug. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:933–40. doi: 10.1002/art.20831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meyers K, Webb A, Frantz J, Randall M. What does it take to retain substance-abusing adolescents in research protocols? Delineation of effort required, strategies undertaken, costs incurred, and 6-month post-treatment differences by retention difficulty. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003 Jan 24;69(1):73–85. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00252-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller MD, Frank E, Reynolds CF. The art of clinical management in pharmacologic trials with depressed elderly patients: lessons from the Pittsburgh Study of Maintenance Therapies in Late-Life Depression. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry : Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. 1999;7:228–34. doi: 10.1097/00019442-199908000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Motzer SA, Moseley JR, Lewis FM. Recruitment and retention of families in clinical trials with longitudinal designs. West J Nurs Res. 1997 Jun;19(3):314–33. doi: 10.1177/019394599701900304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pappas DM, Werch CE, Carlson JM. Recruitment and retention in an alcohol prevention program at two inner-city middle schools. J Sch Health. 1998 Aug;68(6):231–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1998.tb06344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Parra-Medina D, D’antonio A, Smith SM, Levin S, Kirkner G, Mayer-Davis E. Successful recruitment and retention strategies for a randomized weight management trial for people with diabetes living in rural, medically underserved counties of South Carolina: the POWER study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004 Jan;104(1):70–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Robles N, Flaherty DG, Day NL. Retention of resistant subjects in longitudinal studies: description and procedures. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 1994;20(1):87–100. doi: 10.3109/00952999409084059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sprague S, Leece P, Bhandari M, Tornetta P, 3rd, Schemitsch E, Swiontkowski MF. Limiting loss to follow-up in a multicenter randomized trial in orthopedic surgery. Control Clin Trials. 2003 Dec;24(6):719–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mapstone J, Elbourne D, Roberts I. The Cochrane Database of Methodology Reviews: Reviews. 3. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; Chichester, UK: 2002. Strategies to improve recruitment to research studies. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]