Abstract

Three isoforms (α1, α2, and α3) of the catalytic (α) subunit of the plasma membrane (PM) Na+ pump have been identified in the tissues of birds and mammals. These isoforms differ in their affinities for ions and for the Na+ pump inhibitor, ouabain. In the rat, α1 has an unusually low affinity for ouabain. The PM of most rat cells contains both low (α1) and high (α2 or α3) ouabain affinity isoforms, but precise localization of specific isoforms, and their functional significance, are unknown. We employed high resolution immunocytochemical techniques to localize α subunit isoforms in primary cultured rat astrocytes, neurons, and arterial myocytes. Isoform α1 was ubiquitously distributed over the surfaces of these cells. In contrast, high ouabain affinity isoforms (α2 in astrocytes, α3 in neurons and myocytes) were confined to a reticular distribution within the PM that paralleled underlying endoplasmic or sarcoplasmic reticulum. This distribution is identical to that of the PM Na/Ca exchanger. This raises the possibility that α1 may regulate bulk cytosolic Na+, whereas α2 and α3 may regulate Na+ and, indirectly, Ca2+ in a restricted cytosolic space between the PM and reticulum. The high ouabain affinity Na+ pumps may thereby modulate reticulum Ca2+ content and Ca2+ signaling.

The Na+ pump is a plasma membrane (PM) transport ATPase that maintains low cytosolic Na+ and high K+ concentrations in almost all animal cells. This pump is composed of heterodimers of two types of subunits, α and β, both of which occur in multiple isoforms, at least in birds and mammals (1–4). Glycosylated β may help to assemble and transport the α subunit to the PM (5). The catalytic α subunit of this transport protein contains the binding site for the selective Na+ pump inhibitor, ouabain (1, 2). Isoforms of the α subunit with high affinity (α2 and α3) and low affinity (α1) for ouabain have been characterized; indeed, the ouabain affinities differ greatly in a few species, including the rat (1, 2), where the IC50 is >10,000 nM for α1, and only 10–500 nM for α2 and α3 (1, 6). These isoforms also exhibit kinetic (ion affinity) differences (1, 2, 7).

Both high and low ouabain affinity α subunits are up- and down-regulated independently (3, 8, 9). The isoform-specific differences in the ouabain-binding region, especially in α2 and α3, are highly conserved in widely divergent species, but the physiological significance of these isoforms is not understood (4, 10).

Recent immunocytochemical studies have addressed the issue of Na+ pump localization and have reached conflicting conclusions regarding possible functional significance. Polyclonal antibodies (pAbs) raised against purified toad kidney Na+ pump α were used to locate α subunits in smooth muscle of the toad stomach (11). Labeling with this antiserum was confined to PM overlying junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR), where it colocalized with the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (11). This fit the view that the Na+ pump plays an important role in regulating intracellular Ca2+ stores (12), but the apparent paucity of Na+ pump molecules in other (extensive) PM regions is puzzling. In contrast, α1 and α2 appeared to be uniformly distributed in the PM of guinea pig and rat cardiac myocytes, respectively, suggesting that there is not “a physiologically significant colocalization of Na+ pump isoforms with Na+/Ca2+ exchangers in heart” (13). We employed antibodies specific for the three α isoforms to examine this issue in rat astrocytes, neurons, and arterial myocytes, and have obtained a different result that provides a new perspective on the possible function of the different isoforms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Primary Culture of Arterial Smooth Muscle Cells, Astrocytes, and Hippocampal Neurons.

Myocytes were dissociated and cultured from adult rat mesenteric artery (MA) (14). Virtually all cultured MA cells crossreacted with antibodies raised against smooth muscle α-actin. Astrocytes were cultured from the brains of day-old rats (15); purity was verified by crossreactivity with antibodies raised against glial fibrillary acidic protein. Hippocampal neurons were cultured from 17- to 18-day-old rat embryos (16). All cells were grown on 12-mm glass coverslips. MA cells and astrocytes were studied after 7–10 days in culture; neurons were cultured for 14–21 days before use.

Isolation of MA Myocytes.

Rat MA was dissected in Ca2+-free medium to prevent contraction. After removing adipose tissue and adventitia, the arteries were incubated in culture medium containing collagenase (2.5 mg/ml) and washed in physiological salt solution (PSS). Individual myocytes were dispersed, by agitation, on coverslips coated with Cell-Tak (Collaborative Biomedical Products, Bedford, MA). Following adhesion (≈45 min), the cells were fixed and immunolabeled. The PSS contained: 140 mM NaCl, 5.9 mM KCl, 5 mM NaHCO3, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM CaCl2, 0.05 mM EGTA, 11.1 mM glucose, and 10 mM Hepes titrated to pH 7.4 with NaOH.

Immunoblotting.

Membranes were prepared from cultured myocytes, astrocytes and neurons, and fresh rat soleus muscle, as described (14). Membrane proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE and immunolabeled with antibodies raised against specific α subunit isoforms (17).

Immunofluorescence Microscopy.

Cells on coverslips were fixed (45 min, 22°C) with 0.45% (wt/vol) formaldehyde in: 75 mM cyclohexylamine (free base), 75 mM NaCl, 10 mM EGTA, 10 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM piperazine-N,-N′bis (2-ethane sulfonic acid) adjusted to pH 6.8 with HCl. The cells were then immunolabeled (14). Nonspecific crossreactivity was blocked (4 hr, 22°C) with normal donkey or goat serum diluted 1:6 with “antibody buffer” (500 mM NaCl/10 mM MgCl2/20 mM NaN3/20 Tris·HCl, pH 7.4). pAbs, diluted in antibody buffer, were applied to coverslips (4–17 hr, 22°C). The coverslips were then washed, probed (4 hr, 22°C) with diluted (1:500 in antibody buffer), affinity-purified secondary antibodies labeled with the appropriate fluorochrome (Jackson ImmunoResearch), and washed again in antibody buffer. When monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) were used, cells were fixed for 45 min with periodate-lysine-paraformaldehyde [50 mM, 100 mM, 1% (wt/vol)] fixative (18). Coverslips were mounted in 90% glycerol/10% 1 M Tris·HCl (pH 8.5), containing 1 mg/ml p-phenylenediamine.

Cells were imaged in a Nikon Diaphot microscope and images were acquired with a CELLscan system (Scanalytics, Billerica, MA) equipped with a STAR-1 cooled CCD camera. Out-of-focus fluorescence in freshly isolated myocytes and in high magnification images was “restored” by mathematically reassigning out-of-focus fluorescence to the in-focus plane (19) with CELLscan. Background “haze” was removed from low magnification images with a CELLscan “nearest neighbor” deblurring algorithm.

DiOC Labeling.

Cells were exposed (2 min) to PSS containing 0.5 μg/ml DiOC (3,3′-dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide; 0.5 mg/ml stock solution in ethanol). DiOC is a fluorochrome that stains mitochondria (brightly) and SR or endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (20).

Antibodies.

α1 subunits were labeled with pAbs [either “NASE” (10) or one here denoted “PcSynA1” (21)] or mAbs [McK1 (22) or C464–6B (21)]. mAbs [McB2 (22)] or pAbs [“HERED” (10)] were used to label α2 subunits. pAbs were used to label α3 subunits [either “TED” (10) or one here denoted “PcSynA3” (21, 22)]. Antibodies were generously provided by R. W. Mercer (Washington University, St. Louis) and M. J. Caplan (Yale University, New Haven) (PcSynA1, C464–6B, and PcSynA3), T. A. Pressley (Texas Tech University, Lubbock) (NASE, HERED, TED), K. J. Sweadner (Harvard Medical School) (McK1, McB2), and F. Wuytack (Katholieke University, Leuven, Belgium) (SERCA-2b pAbs raised against the SR/ER Ca2+ pump).

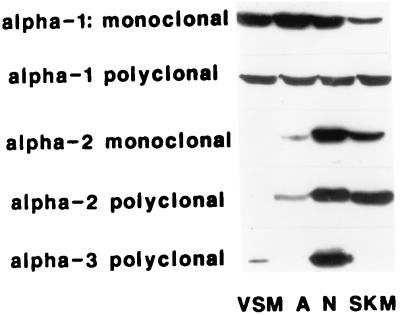

All antibodies used in this study have been well characterized (10, 17, 21–23). Sample Western blots (Fig. 1) confirm the antibody specificity: MA myocytes express α1 (primarily) and α3 (17); astrocytes and skeletal muscle express α1 and α2, and neurons express all three isoforms. The figure legends indicate which antibody was used for each experiment illustrated. Rabbit preimmune serum was used as a control for primary rabbit pAbs; MOPC-21 (Sigma) was used as a control for the primary mouse mAbs.

Figure 1.

Western blot of representative mAbs and pAbs used in this study. The gels were probed with (from top to bottom): monoclonal (C464–6B) and polyclonal (NASE) anti-α1 antibodies, monoclonal (McB2) and polyclonal (HERED) anti-α2 antibodies, and polyclonal anti-α3 antibodies (TED). PcSynA1 and PcSynA3 data are published in ref. 17. The four lanes in each gel each contained 10 μg of membrane protein per lane (100 μg for the VSM lane probed for α3). VSM, vascular smooth muscle; A, astrocytes; N, neurons; SKM, skeletal muscle.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Immunolabeling of α Subunit Isoforms in Freshly Isolated MA Myocytes.

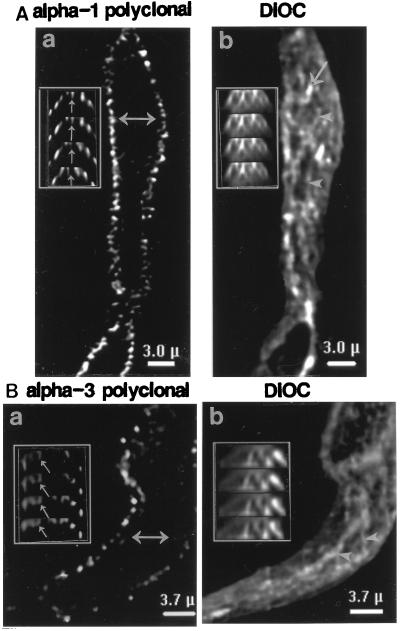

Fig. 2 A and B shows single focal plane restored (19) immunofluorescent images of two freshly isolated, fixed MA myocytes. One cell was labeled with antibodies raised against the α1 isoform of the Na+ pump (Fig. 2A); the second was probed with antibodies raised against α3 (Fig. 2B). The labeling in both cases is punctate, and probably corresponds to clusters of Na+ pump molecules. The antibodies apparently labeled only the cell surfaces (Fig. 2 Aa and Ba), suggesting that most of the epitopes are located in the PM and not in intracellular organelles (3, 4). In cross sections (Fig. 2 Aa and Ba Insets), however, the distribution of label seems more complex because the cell surfaces are invaginated with folds and caveolae (24, 25). Much of the label is observed in the folds (or rows of caveolae), and can be followed through several cross sections (arrows in Fig. 2 Aa and Ba Insets). Moreover, although α3 labeling in myocytes seems much more sparse than α1, differences in distribution are difficult to discern. The same cells were later stained with DiOC to identify intracellular organelles (SR and mitochondria: Fig. 2 Ab and Bb and Insets). Most of the SR is devoid of immunoreactive Na+ pump molecules, but we cannot exclude the possibility that some epitopes are located in the SR immediately subjacent to the PM.

Figure 2.

Distribution of Na+ pump α subunit isoforms in freshly isolated, fixed MA myocytes. (A) Cell was labeled with PcSynA1 directed against α1. (B) Cell was labeled with PcSynA3 raised against α3. The “single focal plane” images were restored with CELLscan. (A and B Insets) Cell cross sections, perpendicular to the plane of the coverslip, at the positions indicated by the double arrows in Aa and Ba. The four consecutive cross sections are 0.25 μm apart. After these images were captured, the cells were treated with DiOC (Ab and Bb) to stain the SR (arrowheads) and mitochondria (arrows).

Localization of α Subunit Isoforms in Cultured MA Myocytes.

Problems with interpretation, due to surface invaginations and other irregularities, can be minimized by using cultured cells that are flat and have relatively smooth surfaces. For example, Fig. 3 illustrates the distribution of Na+ pump α subunit isoforms in primary cultured MA myocytes. The low magnification images show that these cells express both the α1 (Fig. 3Aa) and α3 (Fig. 3Ba) isoforms. The two labels appear to be distributed differently: α1 labeling is diffuse, whereas α3 exhibits an organized reticular pattern.

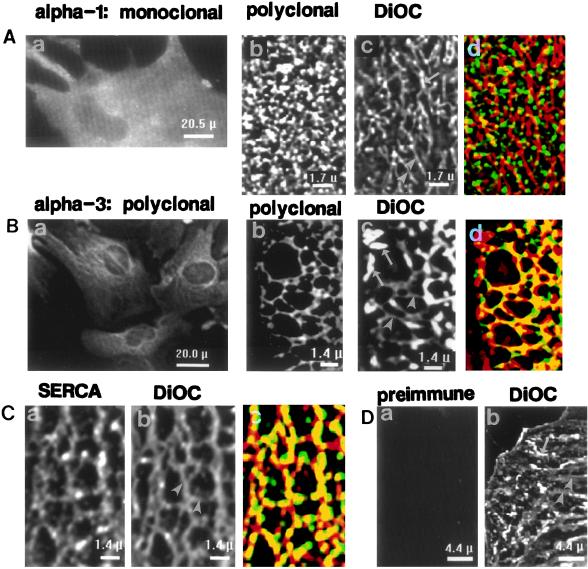

Figure 3.

Localization of Na+ pump α1 and α3 isoforms in primary cultured MA myocytes. (Aa and Ba) Low magnification images of cells crossreacted with mAbs (C464–6B) specific for α1 (Aa) or polyclonal TED antibodies specific for α3 (Ba). The original fluorescent images were filtered by “nearest neighbor” deblurring using CELLscan. (Ab–d and Bb–d) Restored high magnification images of portions of two myocytes. One cell (Ab–d) was crossreacted with polyclonal anti-α1 NASE, and the other (Bb–d), with anti-α3 PcSynA3; both were later treated with DiOC to stain the SR (arrowheads) and mitochondria (arrows) (Ac and Bc). DiOC image Bc was colored red and overlaid on the PcSynA3-labeled image (Bb, green) in Bd; yellow, areas of overlap (note the reticular pattern). Using a 2×2 contingency table (26), we calculated that 5% of the pixels in the image should overlap by chance, whereas we observed 11% overlap. The kappa statistic (where κ = −1.0 to +1.0) can be derived from the contingency table (27); κ > 0 indicates that the overlap is greater than chance. For the data in Bb–d, κ = +0.33. Comparable statistics for Ab–d are: 27% overlap of pixels expected, but only 20% observed, and κ = −0.27. (C) Colocalization of SR Ca2+ pump and DiOC staining. The myocyte was labeled with anti-SERCA-2b antibodies (Ca) and then stained with DiOC (Cb); arrowheads in Cb point to SR. (Cc) Overlay of images Ca and Cb; the dense yellow reticular pattern indicates the extensive overlap (19% overlap of SERCA-2b-labeled pixels with DiOC-labeled pixels expected, 39% observed; κ = +0.79). (D) Control cells incubated with preimmune rabbit serum (Da) and then stained with DiOC (Db).

Restored high magnification images of portions of two other MA myocytes in Fig. 3 Ab–d and Bb–d reveal details of the arrangement of these two α isoforms. The α1 isoform is distributed ubiquitously over the surface of the myocyte (Fig. 3Ab). This is distinctly different from the reticular staining pattern observed with DiOC (Fig. 3Ac), which stains the SR (Fig. 3C) as well as mitochondria, most of which lie on the SR (Fig. 3Bc). The antibodies are specific (Fig. 1); also, rabbit preimmune serum does not label the cells (Fig. 3D), nor does MOPC-21, a control for the mAbs (not shown). The extensive colocalization of DiOC and antibodies raised against the SR Ca2+ pump in another myocyte (Fig. 3Ca–c) indicates that DiOC labels the SR.

In contrast to α1, the α3 label is distributed in a distinct reticular pattern (Fig. 3Bb), which parallels the organization of the underlying DiOC-stained SR (Fig. 3Bc). Indeed, when image Bc is overlaid on image Bb, extensive overlap of the labels is observed (Fig. 3Bd), as indicated by the large amount of yellow in the reticular network.

Distribution of α Subunit Isoforms in Astrocytes.

This striking difference in isoform distribution is not limited to smooth muscle cells. Comparable results are obtained in primary cultured rat astroglia (Fig. 4), except that these cells express α2 and not α3 (Fig. 1; ref. 22). Low power images reveal that α1 is ubiquitously expressed (Fig. 4Aa), as in the myocytes, whereas α2 labeling is organized in a reticular pattern (Fig. 4Ba).

Figure 4.

Localization of Na+ pump α1 and α2 isoforms in primary cultured astrocytes. (Aa and Ba) Low magnification images of cells incubated with McK1 mAbs specific for α1 (Aa) or McB2 mAbs specific for α2 (Ba). The original fluorescent images were filtered by “nearest neighbor” deblurring. (Ab–d and Bb–d) Restored high magnification images comparing portions of two astrocytes labeled with pAbs. One cell (Ab–d) was crossreacted with anti-α1 antibodies (PcSynA1), and the other (Bb–d) with anti-α2 antibodies (HERED). Both cells were later treated with DiOC (Ac and Bc) to stain ER (arrowheads) and mitochondria (arrows). When the respective antibody-labeled images (green) and DiOC-stained images (red) were superimposed (Ad and Bd), a yellow (overlapping) reticular pattern was observed with anti-α2 antibodies (Bd). (Ae–g and Be–g). Restored high magnification images comparing portions of two astrocytes labeled with mAbs. One cell (Ae–g) was crossreacted with anti-α1 antibodies (McK1), and the other (Be–g), with anti-α2 antibodies (McB2). Both cells were also (double) labeled with anti-SERCA-2b antibodies (Af and Bf) to identify the ER. When the respective α subunit-labeled images (green) and SERCA-2b-labeled images (red) were superimposed (Ag and Bg), a yellow (overlapping) reticular pattern was observed with anti-α2 antibodies (Bg). The κ values (see Fig. 3 legend) for the data in Bd and Bg were both +0.50, indicating good correlation (overlap) between α2 and the ER (7.5% of pixels from the two images were overlapping, whereas only 2% overlap was predicted for Bd; 9% overlap was observed versus 3% predicted for Bg). The κ values for Ad and Ag were −0.34 and −0.86, respectively, which indicates that overlap of ER and α1 labels was due to chance.

Similar ubiquitous distribution of α1 is observed in astrocytes labeled with pAbs (Fig. 4Ab) and in those labeled with mAbs (Fig. 4Ae). The α1 distribution is clearly different from the reticular pattern of DiOC staining (Fig. 4Ac) or SERCA-2b labeling (Fig. 4Af) of the ER. Thus, α1 does not colocalize with the ER (Fig. 4 Ad and Ag). In contrast, both polyclonal (Fig. 4Bb) and monoclonal (Fig. 4Be) α2 antibodies distribute in reticular patterns that overlap extensively with underlying ER (as indicated by the yellow reticular patterns in Fig. 4 Bd and Bg). Therefore, at least in rat astrocytes as well as arterial myocytes, this pattern seems to be specific for the high ouabain affinity isoforms. Furthermore, antibodies raised against the SERCA-2b Ca2+ pump (Fig. 4Bf) and against the Na+ pump α2 isoform (Fig. 4 Bb and Be) both label the cells in reticular distribution patterns comparable to that of the ER stained with DiOC (Fig. 4Bc).

The apparent absence of Na+ pump α2 and/or α3 isoforms from extensive areas of PM in these cells raises the question of whether these subunits are retained within the SR/ER, rather than being transported to the PM (3, 4). Functional evidence, however, indicates that substantial numbers of these subunits are, in fact, present in the PM. Nanomolar ouabain increases Ca2+ stores in rat arterial myocytes (28), presumably as a consequence of primary elevation of intracellular Na+ and a secondary, Na+/Ca2+ exchanger mediated, rise in Ca2+ (12). In cultured rat astrocytes, 0.1–1.0 μM of ouabain inhibits the Na+ pump (29) and increases stored Ca2+ (V. Golovina and M.P.B., unpublished work). These ouabain concentrations are at least 100-fold below the IC50 for inhibition of rat α1 (1, 6, 29, 30). Thus, we infer that the PM must contain functional α2 (astrocytes) or α3 (myocytes) subunits.

Localization of α Subunit Isoforms in Neurons.

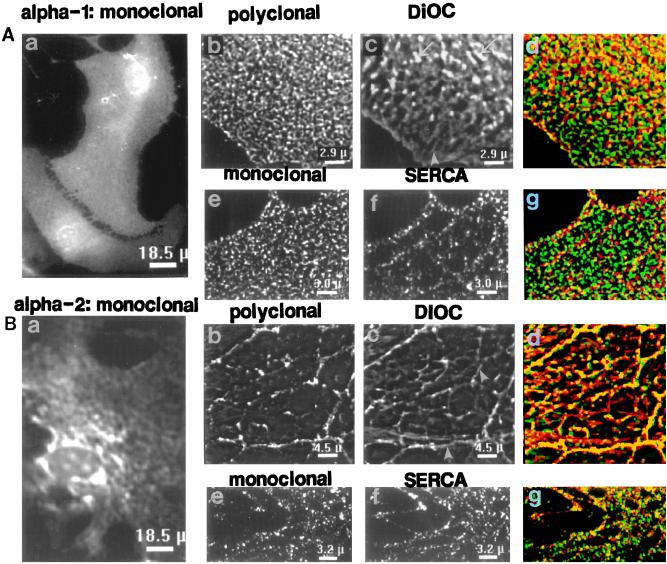

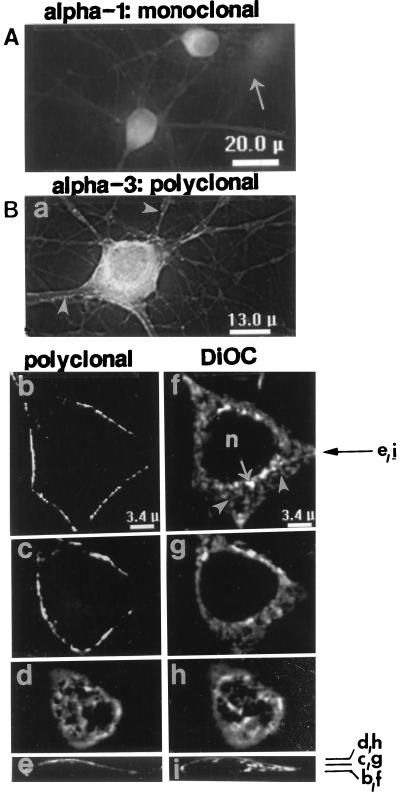

Neurons express all three Na+ pump α isoforms, of which α3 (Fig. 1) is the most abundant (1, 23). Low power images of cultured hippocampal neurons reveal the distribution of the α1 (Fig. 5A) and α3 (Fig. 5B) isoforms. The intense labeling, with α3 antibodies, of both cell bodies and processes contrasts with the absence of label in underlying astrocytes (Fig. 5Ba), which express α2 but not α3 (Fig. 1; ref. 22) (astrocytes were later identified by staining for glial fibrillary acidic protein in some preparations). Both astrocytes (arrow) and neurons, however, possess α1 (Fig. 5A). The α1 labeling appears relatively uniform in cell bodies and processes, whereas α3 antibodies label focal “hot spots” (arrowheads) in axons and dendrites and are nonuniformly distributed on the soma (Fig. 5Ba).

Figure 5.

Localization of Na+ pump α1 and α3 isoforms in primary cultured hippocampal neurons. Low magnification images of cells crossreacted with PcSynA1 anti-α1 antibodies (A) or PcSynA3 anti-α3 antibodies (Ba). The original fluorescent images were filtered by “nearest neighbor” deblurring. The anti-α1 antibodies labeled astrocytes (arrow in A), whereas anti-α3 antibodies did not (astrocytes were detected by glial fibrillary acidic protein labeling in some preparations). Arrowheads in Ba point to “hot spots” of α3 label at the surfaces of neuronal processes. (Bb–i) Restored high magnification images of portions of a neuron crossreacted with PcSynA3 antibodies (Bb–e) and later stained with 50 μg/ml DiOC (Bf–i). Tangential sections through the cell soma are shown: Bb and f, at a plane close to the coverslip; Bc and g, about half-way through the cell; Bd and h, close to the convex cell surface. The plane positions are indicated in cross sections Be and Bi (perpendicular to the coverslip); cross section positions are indicated by the arrow to the right of Bf. ER (arrowheads), brightly stained mitochondria (arrows) and the nucleus (n) are indicated in the DiOC-stained images.

At higher magnification, restored single focal plane images (Fig. 5 Bb–i) show that the α3 antibodies are present in neuronal PM and not in interior organelles. This is best illustrated in optical “sections” through the cell body, parallel to the coverslip (Figs. 5 Bb and c vs. DiOC staining in 5 Bf and g). The α3 label appears punctate, and is distributed in a distinct reticular pattern that is seen at the convex surface of the cell body (Fig. 5Bd). It is difficult to correlate, precisely, the surface α3 labeling directly with underlying cell organelles when the structures are distant from the coverslip (Fig. 5 Be and i), but the subsurface pattern of DiOC staining (Fig. 5Bh) clearly resembles the surface α3 distribution pattern (Fig. 5Bd).

Physiological Significance of α Subunit Localization.

The difference between the ubiquitous distribution of the α1 isoform and the specific localization of α2 and α3 in PM that overlies subplasmalemmal (junctional) SR or ER in these three cell types is remarkable. This raises the possibility that the low and high ouabain affinity isoforms have different functions. The location of the high affinity isoforms appears to provide a clue because the SR and ER sequester Ca2+, and the Ca2+ released from these organelles controls numerous cell activities. A critical link between the Na+ pump and cell Ca2+ is the PM Na+/Ca2+ exchanger, which is also localized to PM regions that overlie junctional SR and ER (11, 14, 15, 31). The energy required to control cytosolic Ca2+ via the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger is derived from the Na+ electrochemical gradient generated by the Na+ pump (12). Thus, the high ouabain affinity isoforms may play an indirect role in regulating [Ca2+]cyt in a restricted space ([Ca2+]cyt/r) between the PM and the junctional SR/ER; in this way, these Na+ pumps may help to control the Ca2+ content of the SR/ER and thereby influence numerous cell processes that depend upon mobilization of stored Ca2+. Moreover, intracellular Ca2+ inhibits the Na+ pump, and α2 and α3 have higher affinities for Ca2+ (IC50s on the order of 10−6 M) than does α1 (32, 33). A small rise in [Ca2+]cyt/r may therefore have a positive feedback effect on [Ca2+]cyt/r, as well as on stored Ca2+ and the cell responses that are activated by mobilization of this Ca2+ (12).

Additionally, it seems relevant that the low and high ouabain affinity isoforms are differently regulated during cell development and as a result of hormone action (3, 8, 9). Indeed, expression of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and the α2 (but not α1) Na+ pump isoform are reciprocally regulated in rat cardiac muscle (9), in which α2 is the predominant high affinity isoform in adults [α3 predominates in neonates (8)]. The α1 may simply be a “housekeeping” form that is required to maintain a low “bulk” cytosolic Na+ concentration.

Our findings suggest a functional basis for the presence and different regulation of both low and high ouabain affinity isoforms of the Na+ pump α subunit in the same cell. These results are circumstantial evidence that there may be restricted cytosolic “microdomains” between the PM and the junctional SR or ER in which the Na+ and Ca2+ concentrations may differ from those in the bulk cytosol; indeed, there is evidence for sub-PM Na+ (34, 35) as well as Ca2+ (35, 36) gradients. This could be the rationale for colocalization of high ouabain affinity Na+ pumps and Na+/Ca2+ exchangers in these PM areas. This might reveal how an endogenous ouabain isomer (12, 37–39), which circulates at nanomolar concentrations (40) and is present in the brain (38, 39), could, by modulating the activity of these high ouabain affinity Na+ pumps (28, 37), play a role in many physiological, and even pathophysiological, processes (12). Finally, this may also explain why the isoform-specific features of the ouabain binding regions of α2 and α3 have been so well conserved during the evolution of higher animals (4, 10). Even Hydra have Na+ pumps with high and low affinity for ouabain (41). Thus, it seems reasonable to speculate that these concepts may also apply to many other species, including man.

Acknowledgments

We thank E. M. Santiago for myocyte isolation and cultures, T. Y. Chaney and R. J. Bloch for neuronal cultures, P. Langenberg for help with statistical analyses, G. Blanco and V. Golovina for sharing unpublished data, and R. J. Bloch, M. L. Borin, V. Golovina, G. R. Monteith, and J. B. Wade for comments on the draft manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants NS-16106 and HL-32276, by the American Heart Association (Maryland Affiliate), and by the University of Maryland at Baltimore School of Medicine and Graduate School.

ABBREVIATIONS

- PM

plasma membrane

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- MA

mesenteric artery

- DiOC

3,3′-dihexyloxacarbocyanine iodide

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

References

- 1.Sweadner K J. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;988:185–220. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(89)90019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jewell E A, Shamraj O I, Lingrel J B. Acta Physiol Scand. 1992;146:161–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ewart H S, Klip A. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:C295–C311. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.269.2.C295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fambrough D M, Lemas M V, Hamrick M, Emerick M, Renaud K J, Inman E M, Hwang B, Takeyasu K. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:C579–C589. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.3.C579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanco G, Berberian G, Beauge L. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1027:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(90)90039-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Therien A G, Nestor N B, Ball W J, Blostein R. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7104–7112. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.7104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lucchesi P A, Sweadner K J. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:9327–9331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Magyar C E, Wang J, Azuma K K, McDonough A A. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:C675–C682. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.269.3.C675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takeyasu K, Lemas V, Fambrough D M. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:C619–C630. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.259.4.C619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pressley T A. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:C743–C751. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.262.3.C743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moore E D W, Etter E F, Philipson K D, Carrington W A, Fogarty K E, Lifshitz L M, Fay F S. Nature (London) 1993;365:657–660. doi: 10.1038/365657a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blaustein M P. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:C1367–C1387. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.6.C1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDonough A A, Zhang Y, Shin V, Frank J S. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:C1221–C1227. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.270.4.C1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Juhaszova M, Ambesi A, Lindenmayer G E, Bloch R J, Blaustein M P. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:C234–C242. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.1.C234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldman W F, Yarowsky P J, Juhaszova M, Krueger B K, Blaustein M P. J Neurosci. 1994;14:5834–5843. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-10-05834.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banker G A, Cowan W M. Brain Res. 1977;126:397–342. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90594-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juhaszova M, Mercer R W, Weiss D N, Podberesky D J, Heidrich J, Blaustein M P. In: The Sodium Pump. Bamberg E, Schöner W, editors. Darmstadt: Steinkopff; 1994. pp. 852–855. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLean I W, Nakane P K. J Histochem Cytochem. 1974;22:1077–1083. doi: 10.1177/22.12.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carrington W A, Fogarty K E, Fay F S. In: Noninvasive Techniques in Cell Biology. Foster K, Grinstein S, editors. New York: Wiley/Liss; 1990. pp. 53–72. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Terasaki M. Methods Cell Biol. 1989;29:125–135. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blanco G, Koster J C, Mercer R W. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8542–8546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGrail K M, Phillips J M, Sweadner K J. J Neurosci. 1991;11:381–391. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-02-00381.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pietrini G, Matteoli M, Banker G, Caplan M J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8414–8418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fay F, Fogarty K, Fujiwara K. In: Smooth Muscle Contraction. Stephens N L, editor. New York: Dekker; 1984. pp. 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Somlyo A P, Somlyo A V. In: The Heart and Cardiovascular System. 2nd Ed. Fozzard H A, Haber E, Jennings R B, Katz A M, Morgan H E, editors. New York: Raven; 1992. pp. 1295–1324. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taneja K L, Lifshitz L M, Fay F S, Singer R H. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:1245–1260. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.5.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fleiss J L. In: Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. 2nd Ed. Bradley R A, Hunter J S, Kendall D G, Watson G S, editors. New York: Wiley; 1981. pp. 212–236. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weiss D N, Podberesky D J, Heidrich J, Blaustein M P. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:C1443–C1448. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.265.5.C1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsuda T, Murata Y, Kawamura N, Hayashi M, Tamada K, Maeda S, Baba A. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;307:175–182. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adams R J, Schwartz A, Grupp G, Grupp I, Lee S W, Wallick E T, Powell T, Twist V W, Gathiram P. Nature (London) 1992;296:167–169. doi: 10.1038/296167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Juhaszova M, Shimizu H, Borin M L, Yip R K, Santiago E M, Lindenmayer G E, Blaustein M P. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1996;779:318–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb44804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGeoch J E. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;173:99–105. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turi A, Somogyi J, Mullner N. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;174:969–974. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91513-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lederer W J, Niggli E, Hadley R W. Science. 1990;248:372–376. doi: 10.1126/science.2326638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wendt-Gallitelli M F, Voight T, Isenberg G. J Physiol (London) 1993;472:33–44. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Janiak R, Lewartowski B, Langer G A. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1996;28:253–264. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hamlyn J M, Blaustein M P, Bova S, DuCharme D W, Harris D W, Mandel F, Mathews W R, Ludens J H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:6259–6263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.14.6259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao N, Lo L C, Berova N, Nakanishi K, Tymiak A A, Ludens J H, Haupert G T., Jr Biochemistry. 1995;34:9893–9896. doi: 10.1021/bi00031a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamada K, Goto A, Omata M. FEBS Lett. 1995;360:67–69. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00078-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rossi G P, Manunta P, Hamlyn J M, Pavan E, DeToni R, Semplicini A, Pessina A C. J Hypertens. 1995;13:1181–1191. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199510000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Canfield V A, Xu K-Y, D’Aquila T, Shyjan A W, Levenson R. New Biol. 1992;4:339–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]