Abstract

Background and aims

Several antibodies have been associated with Crohn's disease and are associated with distinct clinical phenotypes. The aim of this study was to determine whether a panel of new antibodies against bacterial peptides and glycans could help in differentiating inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and whether they were associated with particular clinical manifestations.

Methods

Antibodies against a mannan epitope of Saccharomyces cerevisiae (gASCA), laminaribioside (ALCA), chitobioside (ACCA), mannobioside (AMCA), outer membrane porins (Omp) and the atypical perinuclear antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody (pANCA) were tested in serum samples of 1225 IBD patients, 200 healthy controls and 113 patients with non‐IBD gastrointestinal inflammation. Antibody responses were correlated with the type of disease and clinical characteristics.

Results

76% of Crohn's disease patients had at least one of the tested antibodies. For differentiation between Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, the combination of gASCA and pANCA was most accurate. For differentiation between IBD, healthy controls and non‐IBD gastrointestinal inflammation, the combination of gASCA, pANCA and ALCA had the best accuracy. Increasing amounts and levels of antibody responses against gASCA, ALCA, ACCA, AMCA and Omp were associated with more complicated disease behaviour (44.7% versus 53.6% versus 71.1% versus 82.0%, p < 0.001), and a higher frequency of Crohn's disease‐related abdominal surgery (38.5% versus 48.8% versus 60.7% versus 75.4%, p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Using this new panel of serological markers, the number and magnitude of immune responses to different microbial antigens were shown to be associated with the severity of the disease. With regard to the predictive role of serological markers, further prospective longitudinal studies are necessary.

Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis are two distinct clinical subtypes of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and are characterized by chronic, recurrent and tissue‐damaging inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract. Although the exact aetiology is still not known, current knowledge about their pathophysiology suggests that the intestinal flora triggers and drives an aberrant immune response in a susceptible host, resulting in chronic inflammation of the gut.1 This idea is supported by the importance of faecal stream in the development and progression of the disease,2,3 by the occurrence of antibodies directed at several microbial antigens,4,5,6,7,8,9 and by the identification of pathogen recognition receptors, caspase recruitment domain 15 (CARD15) and Toll‐like receptor 4 (TLR4), as susceptibility genes to IBD.10,11

Already in 1959 investigators reported antibodies to colon extract in patients with ulcerative colitis.12 Since then, several antibodies have been described in IBD. The most thoroughly studied are auto‐antibodies against an unidentified nuclear lamina protein present in neutrophils (pANCA)4 and antibodies against mannose epitopes from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (ASCA).5,6 More recently, antibodies to the outer‐membrane porin C of Escherichia coli (OmpC)7 against a Pseudomonas fluorescens‐associated sequence I2 (anti‐I2)8 and against the flagellin CBir1 (anti‐CBir1)9 were reported in Crohn's disease patients.

All of these serological markers alone have only a modest accuracy in detecting IBD. The combination, however, might be helpful in differentiating ulcerative colitis from Crohn's disease. pANCA and ASCA, for example, carry a very high specificity ranging from 95% to 99% when used in combination. This particular combination has been suggested to help in those patients in whom the distinction between Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis is not clear despite the classic diagnostic tools.13,14 However, the sensitivity of this combination is only approximately 30–60%, however, and the clinical usefulness in better classifying indeterminate colitis remains controversial.15 Therefore, there still is a considerable unmet need for serological markers in IBD.

Serological markers may, however, contribute to disease stratification. In Crohn's disease patients, a more aggressive disease course, defined by fibrostenotic or internal perforating disease and the need for small‐bowel surgery was associated with higher serological levels of ASCA.16 In accordance with this finding, Mow et al.17 described both a qualitative and a quantitative correlation between the presence and amount of antibody production (anti‐I2, OmpC and ASCA) and a complicated disease course. More recently, anti‐CBir1 has also been associated independently with an internal perforating disease and the need for small‐bowel surgery.9

Based on the existence of Crohn's disease‐specific antibodies against sugars, such as ASCA, the presence of other glycan antibodies in IBD was recently evaluated.18,19 Glycans (polysaccharides) are predominant surface components, which can be found on micro‐organisms, immune cells, erythrocytes, tissue matrices. Antibodies against glycans can be assessed using a GlycoChip (Glycominds Ltd., Lod, Israel) and appropriate ELISAs. In addition to antibodies against mannan (IgG anti‐covalently attached anti‐Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies or gASCA; and anti‐mannobioside (Man(α1,3)Man(α)) carbohydrate IgG antibody or AMCA), this technique revealed antibodies to laminaribioside (anti‐laminaribioside (Glc(β1,3)Glc(β)) carbohydrate IgG antibodies or ALCA) and chitobioside (anti‐chitobioside (GlcNAc(β1,4)GlcNAc(β)) carbohydrate IgA antibodies or ACCA), suggesting a high discriminative capability between Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis.19 Laminaribioside is the building block of laminarin and may be found in the cell walls of saprophytic and pathogenic fungi and yeast, as well as in food (oats) and algae. Chitobioside is a component of chitin, a major element of the insect cuticle and cell walls of infectious pathogens such as bacteria and yeast.19

The aim of this study was to assess the clinical utility of this new set of serological markers in a large cohort of IBD patients, combined with a more universal IgA antibody to outer membrane porins from several pathogens and an indirect immunofluorescent pANCA assay (Omp Plus ELISA and pANCA indirect immunofluorescence; INOVA Diagnostics Inc., San Diego, California, USA).

Materials and methods

Patient population

A cohort of 1538 individuals was studied, including 1225 IBD patients, of whom 913 patients had Crohn's disease (75%), 272 patients had ulcerative colitis (22%) and 40 patients had indeterminate colitis (3%). Patient characteristics are listed in table 1. All patients were followed at the IBD unit of the University Hospital in Leuven, Belgium. Diagnosis was based on clinical, radiological and endoscopic examination and histological findings.20 All patients with IBD followed at our clinic between 1998 and 2006 were asked to participate in this study. There were no exclusion criteria.

Table 1 Patient characteristics.

| IBD patients (n = 1225) | Crohn's disease patients (n = 913) | Ulcerative colitis patients (n = 272) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women/men (%) | 686/539 (56/44) | 533/380 (58/42) | 134/138 (49/51) | |||

| Median age at diagnosis, years (IQR) | 24.0 (19.0–31.0) | 22.0 (18.0–30.0) | 27.0 (21.0–36.0) | |||

| Median age, years (IQR) | 36.0 (26.0–46.0) | 35.0 (26.0–46.0) | 35.0 (26.0–45.0) | |||

| Duration of disease, years (IQR) | 8.0 (3.0–14.0) | 8.5 (3.0–15.0) | 7.0 (2.0–13.0) | |||

| Familial (%) | 384/1220 (31) | 308/911 (34) | 68/269 (25) | |||

| IBD surgery (%) | 466/997 (47) | 422/755 (56) | 41/220 (19) | |||

| Smoking (%) | 366/891 (41) | 307/686 (45) | 57/189 (30) | |||

| Location | ||||||

| Ileal involvement (%) | 623/757 (82) | |||||

| Colonic involvement (%) | 558/757 (74) | |||||

| Upper involvement (%) | 74/757 (10) | |||||

| Anal involvement (%) | 287/751 (38) | |||||

| Proctitis (%) | 47/217 (22) | |||||

| Left‐sided colitis (%) | 81/217 (37) | |||||

| Pancolitis (%) | 89/217 (41) | |||||

| Behaviour* | ||||||

| Non‐stricturing non‐penetrating (%) | 274/738 (37) | |||||

| Stricturing (%) | 120/738 (16) | |||||

| Penetrating (%) | 344/738 (47) | |||||

IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IQR, interquartile range.

*See Gasche et al.21

The control group consisted of 200 ethnically matched healthy controls (HC, F/M 119/81, median (IQR) age 33.0 (27.2–40.4) years) and 113 patients with non‐IBD gastrointestinal inflammation (non‐IBD G1, F/M 53/60, Median (IQR) age 63.2 (45.5–77.9) years), including patients with diverticulitis, infectious colitis, ischaemic colitis and pseudo‐membranous colitis.

All individuals gave informed consent, and the study was approved by the ethics committee of the Catholic University of Leuven.

Serological analysis

All blood samples were taken at the time of consent and enrolment. Sera were analysed for the expression of gASCA IgG, ALCA IgG, ACCA IgA, AMCA IgG and Omp IgA antibodies in a blinded fashion, by two experienced laboratory technicians. All assays were performed in our own laboratory by using ELISA, as described by the manufacturers, Glycominds Ltd. and INOVA Diagnostics Inc. Briefly, 50 μl (Glycominds) or 100 μl (INOVA Diagnostics) of diluted serum samples (dilution 1 : 101), calibrator, and prediluted negative and positive controls reacted for 30 minutes with specific antigens immobilized in microtitre wells. After washing away unbound serum components, antibodies that specifically bound to the antigen of interest were detected using 100 μl enzyme labelled anti‐human IgG or IgA antibodies. After 30 minutes of incubation, unbound conjugate was removed by washing, and 100 μl chromogenic substrate (tetramethylbenzidine) was added and incubated for 30 minutes in the dark (15 minutes for gASCA and ALCA). Subsequently, 100 μl stop solution was added to terminate the enzymatic reaction, and thereafter absorbance of the calibrator, controls and samples was evaluated spectrophotometrically at 450 nm. The optical density is directly proportional to the amount of bound antibody. Finally, results were expressed as ELISA units (EU), which are relative to a Glycominds laboratory (gASCA, ALCA, ACCA and AMCA) or an INOVA (Omp) laboratory calibrator that is derived from a pool of patient sera with well‐characterized disease found to have reactivity to this antigen.

pANCA was determined by indirect immunofluorescence using ethanol‐fixed neutrophil slides (INOVA Diagnostics). Sera were incubated at a 1/40 dilution for 30 minutes at room temperature, washed and incubated with fluorescein isothiocyanate‐labeled rabbit antihuman IgG immunoglobulin (INOVA Diagnostics). Slides were then examined under ultraviolet using a Leitz Wetzler Orthoplan microscope (Germany). Sera that exhibited fluorescence on indirect immunofluorescence were titred to endpoint. Interference by antinuclear antibodies, which may mimic the pANCA pattern, was ruled out by using formalin‐fixed cells. The cut‐off value for positivity was set at 1/40.

Accuracy analysis and cut‐off values

For each serological marker studied, receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves were generated by plotting sensitivity versus 1‐specificity. As we used a semi‐quantitative pANCA assay, these ROC curves were constructed for pANCA‐positive and pANCA‐negative individuals separately. Based on clinical needs we evaluated the use of the different markers for three distinct settings. First, patients with abdominal complaints and inflammation in the blood in whom we want to rule out IBD (IBD versus non‐IBD gastrointestinal inflammation). Second, patients with abdominal complaints but no inflammation in the blood, in whom we also want to rule out IBD (IBD versus healthy controls). And finally, patients with known IBD, in whom subtyping into Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis remains problematical (Crohn's disease versus ulcerative colitis).

Based on these ROC curves and the manufacturer's guidelines, cut‐off values for positivity were defined at 50 EU for gASCA, 70 EU for ALCA, 90 EU for both ACCA and AMCA, and 25 EU for Omp. All results below these cut‐off values were regarded as being negative.

To evaluate the association between Crohn's disease phenotype characteristics and the level of immune response toward gASCA, ALCA, ACCA, AMCA and Omp, quartile scores for each serological marker were calculated, as described previously.7 For each antigen, patients whose antibody levels were in the first, second, third, and fourth quartile of the distribution were assigned a quartile score of 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. For each patient, a quartile sum score (range QS5–QS20) representing the cumulative quantitative immune response toward all five antigens was obtained by adding individual quartile scores for each microbial antigen. The linear‐by‐linear association was used to test whether there was a linear trend in the proportion of patients with a specific disease phenotype characteristic, as the level of antibody responses increased by quartiles.

Phenotypical characteristics of IBD patients

In Crohn's disease patients we looked for involvement of the ileum, colon, anus and upper gastrointestinal tract (i.e. proximal from the distal third of the ileum). Crohn's disease patients were also assigned behavioural phenotypes based on the Vienna classification.21 As in the Vienna classification, we did not distinguish internal from perianal penetrating disease. In this study, complicated disease behaviour in Crohn's disease patients was defined as the presence of strictures or fistula during follow‐up. Ulcerative colitis‐like behaviour in Crohn's disease patients was defined as inflammation restricted to the colon, with the absence of strictures and fistula. The latter definition is different from the original reported definition.22

Following the Montreal classification, ulcerative colitis patients were defined by the extent of the colorectal inflammation at the endoscopic level (ulcerative proctitis, left‐sided colitis and pancolitis).23

In all IBD patients we assessed their smoking status at diagnosis and the familial occurrence of IBD. Patients were determined as smokers if they were actively smoking more than seven cigarettes a week, for at least 6 months.24 Furthermore, we looked for the need for abdominal surgery (defined as intestinal resections) for IBD complications.

For most of the patients, phenotypic data were assessed at the moment of informed consent and enrolment. However, data were constantly updated as it is known that the phenotypical behaviour of IBD patients changes over time.25,26 Therefore, phenotypes are given at the last follow‐up.

Statistical analysis

All statistical tests were performed using the SPSS 15.0 statistical software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). After testing for normality of the different EU with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (at p > 0.05), associations between antibody responses against microbial antigens and disease phenotype characteristics were performed using a Mann–Whitney U‐test or a Kruskal‐Wallis test.

To define whether the combination of serological markers improved the accuracy in each of the three “clinical situations” we performed a backward linear regression with all five markers, for pANCA‐positive and pANCA‐negative individuals separately. This regression analysis provided us with the relative contribution of each individual marker. Based on the proposed equation (y = a + b*marker x + c*marker y) a new ROC curve was reconstructed and we compared the area under the curve (AUC; with 95% confidence interval) of this reconstructed ROC curve with those of the individual markers.

Multivariate analyses were performed using binary logistic regression to define independent predictors of seropositivity to each individual marker and disease outcome.

Results

Diagnostic accuracy of each individual serological marker

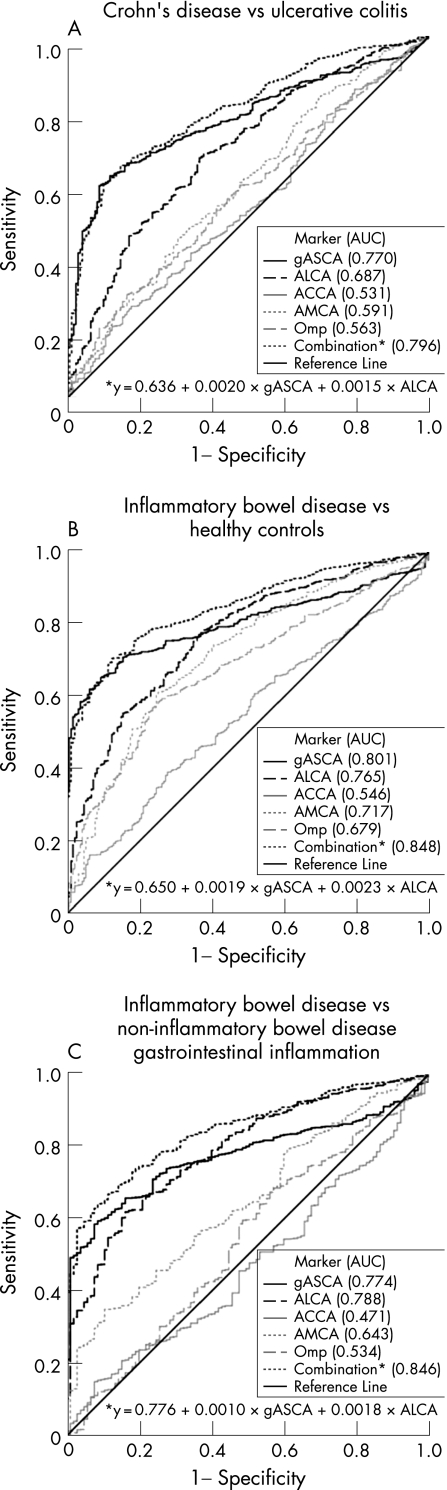

The ROC curves for each individual marker in the three “clinical situations” are shown in figure 1. gASCA was clearly the most accurate marker for differentiating patients with Crohn's disease from patients with ulcerative colitis (AUC 0.769). For differentiation between patients with IBD and healthy controls or patients with non‐IBD gastrointestinal inflammation both gASCA and ALCA had a good diagnostic accuracy (gASCA AUC 0.777 and 0.753, respectively; ALCA AUC 0.747 and 0.778, respectively).

Figure 1 (A) Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of different serological markers for differentiation between Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in perinuclear anti‐neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody (pANCA)‐negative patients. (B) ROC curves of different serological markers for differentiation between inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and healthy controls (HC) in pANCA‐negative individuals. (C) ROC curves of different serological markers for differentiation between IBD and patients with non‐IBD gastrointestinal inflammation (non‐IBD GI) in pANCA‐negative individuals. AUC, Area under the curve.

Based on the proposed cut‐off values, the sensitivity and specificity of the different markers were calculated. Table 2 shows the predictive power of each individual marker in distinguishing patients with Crohn's disease from ulcerative colitis, IBD from healthy controls and IBD from non‐IBD gastrointestinal inflammation. pANCA was found in 37.3% of ulcerative colitis patients and 10.0% of Crohn's disease patients. Whereas all anti‐glycan and anti‐OmpC antibodies were specific for Crohn's disease (80.5–93.0%), the sensitivity of gASCA, ALCA, ACCA, AMCA and Omp was, respectively, 56.4%, 17.7%, 20.7%, 28.1% and 29.1%.

Table 2 Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive value of all studied markers in three “clinical situations”.

| Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Positive predictive value (%) | Negative predictive value (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crohn's disease (n = 913) vs. ulcerative colitis (n = 272) | ||||

| gASCA (⩾50 EU) | 56.4 | 90.4 | 95.2 | 38.2 |

| ALCA (⩾70 EU) | 17.7 | 93.0 | 89.5 | 25.2 |

| ACCA (⩾90 EU) | 20.7 | 84.9 | 82.2 | 24.2 |

| AMCA (⩾90 EU) | 28.1 | 82.4 | 84.3 | 25.5 |

| Omp (⩾25 EU) | 29.1 | 80.5 | 83.4 | 25.3 |

| pANCA* | 37.3 | 90.0 | 52.6 | 82.8 |

| IBD (n = 1225) vs healthy controls (n = 200) | ||||

| gASCA (⩾50 EU) | 44.8 | 99.0 | 99.6 | 22.7 |

| ALCA (⩾70 EU) | 14.9 | 98.5 | 98.4 | 15.9 |

| ACCA (⩾90 EU) | 19.3 | 85.5 | 89.1 | 14.7 |

| AMCA (⩾90 EU) | 25.9 | 92.0 | 95.2 | 16.8 |

| Omp (⩾25 EU) | 27.0 | 93.5 | 96.2 | 17.3 |

| pANCA | 17.2 | 97.5 | 97.7 | 16.2 |

| IBD (n = 1225) vs non‐IBD GI (n = 113) | ||||

| gASCA (⩾50 EU) | 44.8 | 98.2 | 99.6 | 14.1 |

| ALCA (⩾70 EU) | 14.9 | 99.1 | 99.5 | 9.7 |

| ACCA (⩾90 EU) | 19.3 | 84.1 | 92.9 | 8.8 |

| AMCA (⩾90 EU) | 25.9 | 92.9 | 97.5 | 10.4 |

| Omp (⩾25 EU) | 27.0 | 75.2 | 92.2 | 8.7 |

| pANCA | 17.2 | 93.8 | 96.8 | 9.4 |

ACCA, Anti‐chitobioside carbohydrate antibody; ALCA, anti‐laminaribioside carbohydrate antibody; AMCA, anti‐mannobioside carbohydrate antibody; EU, ELISA units; gASCA, anti‐Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody; GI, gastrointestinal inflammation; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; Omp, outer membrane porin; pANCA, perinuclear anti‐neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody.

*pANCA accuracy to detect ulcerative colitis.

Combination of different serological markers

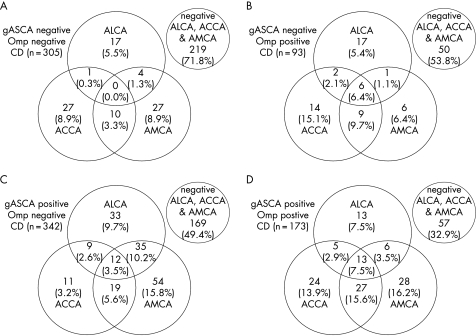

As shown in figure 2A, among the 305 gASCA‐negative Omp‐negative Crohn's disease patients, 7% were ALCA positive, 12% were ACCA positive and 13% were AMCA positive. A total of 219 Crohn's disease patients (24%) were negative for all of the tested Crohn's disease‐associated antibodies. Half of the 435 Crohn's disease patients who were either gASCA negative Omp positive (n = 93) or gASCA positive Omp negative (n = 342), were positive for any of the other anti‐glycan antibodies (fig 2B,C). Sixty‐seven per cent of the 173 gASCA‐positive Omp‐positive Crohn's disease patients also had antibodies against other anti‐glycan antibodies (fig 2D). Only 13 out of 913 Crohn's disease patients (1.4%) were positive for all Crohn's disease‐associated markers.

Figure 2 The presence of glycan antibodies against laminaribioside (ALCA), chitobioside (ACCA) and mannobioside (AMCA) in 305 anti‐Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody (gASCA)‐negative outer membrane porin (Omp)‐negative Crohn's disease patients (A), 93 gASCA‐negative Omp‐positive Crohn's disease patients (B), 342 gASCA‐positive Omp‐negative Crohn's disease patients (C), and 173 gASCA‐positive Omp‐positive Crohn's disease patients (D).

Linear regression analysis was performed for pANCA‐positive and pANCA‐negative individuals separately. In pANCA‐positive individuals, the level of gASCA antibody response was the only independent variable for diagnosing Crohn's disease or IBD. In contrast, in pANCA‐negative patients, the level of both gASCA and ALCA antibody response came out as independent variables for diagnosing Crohn's disease or IBD. For these pANCA‐negative individuals, new ROC curves were constructed based on regression constant value and coefficients (Crohn's disease versus ulcerative colitis y = 0.636 + 0.0020x gASCA + 0.0015x ALCA; IBD versus healthy controls y = 0.650 + 0.0019x gASCA + 0.0023x ALCA; IBD versus non‐IBD gastrointestinal inflammation y = 0.776 + 0.0010x gASCA + 0.0018x ALCA).

As shown in figure 1, the combination of gASCA, pANCA and ALCA only brought a minor improvement in the differentiation between Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, compared with the classic combination of gASCA and pANCA (in pANCA‐negative patients: AUC 0.796 (95% CI 0.763–0.829) for combination of gASCA and ALCA versus 0.770 (95% CI 0.738–0.802) for gASCA alone). In contrast, the combination of gASCA, ALCA and pANCA clearly had a greater diagnostic accuracy for differentiating IBD from healthy controls and non‐IBD gastrointestinal inflammation, than each of the markers alone or the classic combination of gASCA and pANCA. In pANCA‐negative individuals, for differentiating IBD from healthy controls, the AUC (95% CI) was 0.848 (0.824–0.871) for the combination of gASCA and ALCA, 0.801 (0.777–0.826) for gASCA alone, and 0.765 (0.731–0.800) for ALCA alone. For differentiating IBD from non‐IBD gastrointestinal inflammation, again in pANCA‐negative individuals, the AUC (95% CI) was 0.846 (0.816–0.875) for the combination of gASCA and ALCA, 0.774 (0.743–0.806) for gASCA alone, and 0.788 (0.748–0.829) for ALCA alone.

Antibodies against gASCA, ALCA, ACCA, AMCA and Omp are associated with a more severe Crohn's disease behaviour

Out of 913 Crohn's disease patients, complete information regarding disease localization, behaviour and the need for Crohn's disease‐related surgery was available in 738 patients (80%). Only those 738 Crohn's disease patients (445 women/293 men, median age 36 years (27–46)) were used for further analysis. The characteristics of the 738 patients were no different from those of the whole Crohn's disease cohort.

Table 3 shows the proportion of Crohn's disease patients with ileal involvement, complicated behaviour, a need for surgery, and ulcerative colitis‐like behaviour, segregated by response to each serological marker. In a univariate analysis, gASCA, ALCA, ACCA and Omp were significantly associated with ileal involvement. All studied markers were significantly associated with complicated behaviour (strictures or fistula) and the need for abdominal surgery. gASCA, ACCA, AMCA and Omp were negatively associated with ulcerative colitis‐like disease behaviour. In contrast, pANCA was associated with ulcerative colitis‐like disease behaviour and negatively associated with ileal involvement, complicated behaviour and the need for abdominal surgery.

Table 3 Univariate analysis in 738 Crohn's disease patients.

| Ileal involvement | Complicated behaviour | Need for abdominal surgery | Ulcerative colitis‐like behaviour | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | p | % | p | % | p | % | p | ||

| gASCA | Present | 86.4 | 0.001 | 71.4 | <0.001 | 63.8 | <0.001 | 6.3 | 0.001 |

| Absent | 76.6 | 51.3 | 44.9 | 13.8 | |||||

| ALCA | Present | 91.1 | 0.003 | 71.1 | 0.028 | 65.2 | 0.015 | 6.7 | NS |

| Absent | 80.3 | 61.0 | 53.7 | 10.1 | |||||

| ACCA | Present | 89.9 | 0.004 | 80.5 | <0.001 | 70.4 | <0.001 | 4.4 | 0.014 |

| Absent | 80.1 | 58.0 | 51.8 | 10.9 | |||||

| AMCA | Present | 83.9 | NS | 76.3 | <0.001 | 67.4 | <0.001 | 5.8 | 0.024 |

| Absent | 81.5 | 57.0 | 50.8 | 11.1 | |||||

| Omp | Present | 88.5 | 0.003 | 74.4 | <0.001 | 72.7 | <0.001 | 3.5 | <0.001 |

| Absent | 79.5 | 57.7 | 48.3 | 12.1 | |||||

| pANCA | Present | 73.2 | 0.034 | 47.9 | 0.006 | 43.7 | 0.029 | 21.1 | <0.001 |

| Absent | 83.3 | 64.4 | 57.2 | 8.3 | |||||

| Ileal involvement | Present | 39.7 | <0.001 | 26.7 | <0.001 | 53.4 | <0.001 | ||

| Absent | 67.9 | 62.1 | 0.0 | ||||||

ACCA, Anti‐chitobioside carbohydrate antibody; ALCA, anti‐laminaribioside carbohydrate antibody; AMCA, anti‐mannobioside carbohydrate antibody; gASCA, anti‐Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody; Omp, outer membrane porin; pANCA, perinuclear anti‐neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody.

In a multivariate analysis (table 4), we found that gASCA, ALCA, ACCA and Omp were independently associated with ileal involvement. Furthermore, gASCA, ACCA, AMCA, Omp and ileal involvement were independently associated with non‐inflammatory behaviour, whereas gASCA, AMCA, Omp and ileal involvement were also independently associated with the need for abdominal surgery. pANCA and Omp were, respectively, positively and negatively associated with ulcerative colitis‐like disease behaviour.

Table 4 Clinical features in 738 Crohn's disease patients: backward Wald binary logistics.

| Ileal involvement | Complicated behaviour | Need for abdominal surgery | Ulcerative colitis‐like behaviour | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| gASCA | 0.010 | <0.001 | 0.001 | NS |

| ALCA | 0.033 | NS | NS | NS |

| ACCA | 0.044 | 0.003 | NS | NS |

| AMCA | NS | 0.005 | 0.005 | NS |

| Omp | 0.044 | 0.015 | <0.001 | 0.012* |

| pANCA | 0.090* | 0.062* | NS | 0.023 |

| Ileal involvement | <0.001 | <0.001 | NS |

ACCA, Anti‐chitobioside carbohydrate antibody; ALCA, anti‐laminaribioside carbohydrate antibody; AMCA, anti‐mannobioside carbohydrate antibody; gASCA, anti‐Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody; Omp, outer membrane porin; pANCA, perinuclear anti‐neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody.

P values are indicated.

*Negative association.

Table 5 shows the relationship between serum reactivity toward 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5 of the studied antigens (gASCA, ALCA, ACCA, AMCA and Omp) and the disease characteristics. Patients who had antibody responses against a higher number of the Crohn's disease‐associated tested antigens (gASCA, ALCA, ACCA, AMCA, Omp) had more ileal involvement, complicated behaviour and the need for Crohn's disease‐related abdominal surgery, and were less likely to have an ulcerative colitis‐like disease behaviour.

Table 5 Clinical characteristics of Crohn's disease patients in function of the amount of positive antibodies against gASCA, ALCA, ACCA, AMCA and Omp.

| No. of antibodies against tested microbial antigens | p trend | OR (95% CI) of O vs 4/5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (n = 164) (%) | 1 (n = 236) (%) | 2 (n = 156) (%) | 3 (n = 118) (%) | 4 (n = 51) (%) | 5 (n = 13) (%) | |||

| Ileal involvement (%) | 69.5 | 82.6 | 86.5 | 89.8 | 88.2 | 92.3 | <0.001 | 3.57 (1.52 to 8.38) |

| Complicated behaviour (%) | 40.9 | 58.5 | 71.2 | 81.4 | 78.4 | 92.3 | <0.001 | 6.27 (3.11 to 12.64) |

| Need for abdominal surgery (%) | 37.8 | 49.2 | 59.6 | 74.6 | 84.3 | 76.9 | <0.001 | 7.93 (3.85 to 16.32) |

| Ulcerative colitis‐like behaviour (%) | 18.9 | 9.7 | 5.8 | 4.2 | 3.9 | 0 | <0.001 | 0.14 (0.03 to 0.60) |

ACCA, Anti‐chitobioside carbohydrate antibody; ALCA, anti‐laminaribioside carbohydrate antibody; AMCA, anti‐mannobioside carbohydrate antibody; gASCA, anti‐Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody; Omp, outer membrane porin.

P trend based on linear‐by‐linear association. OR and 95% CI are based on comparison between 164 Crohn's disease patients with the absence of antibody response and 64 Crohn's disease patients with antibodies to four or all five tested antigens.

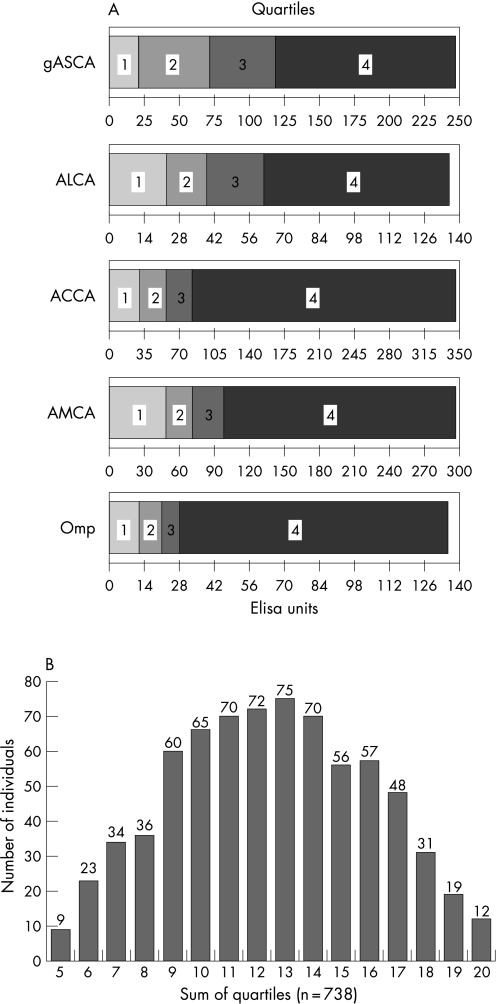

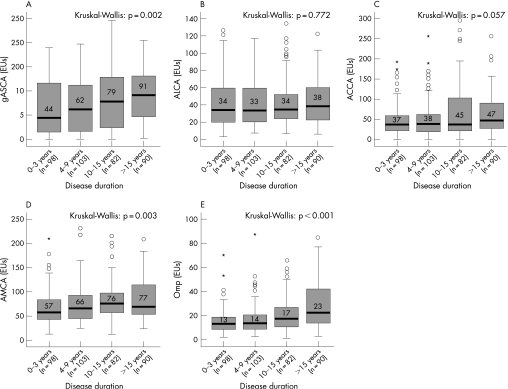

We also looked at whether we could find an association between the level of antibody response divided by quartiles against gASCA, ALCA, ACCA, AMCA and Omp, and the frequency of various Crohn's disease phenotypes, as proposed by Landers et al.7 The quartiles to each of the individual markers consisted, respectively, of 184, 185, 185 and 184 Crohn's disease patients. Figure 3A shows the patients for each serological response broken down by quartiles and assigned a score of 1 to 4 on the basis of their designated quartile. As we used a semi‐quantitative pANCA assay, we were not able to perform a quartile analysis for these data.

Figure 3 (A) Quartile analysis of the Crohn's disease cohort for the five tested serological markers (anti‐Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody, gASCA; anti‐laminaribioside carbohydrate antibody, ALCA; anti‐chitobioside carbohydrate antibody, ACCA; anti‐mannobioside carbohydrate antibody, AMCA; and outer membrane porin, Omp). For each of the different markers the population was subdivided into four equal quartiles (n = 184, 185, 185 and 184) based on the antibody response (ELISA units). (B) Quartile sums were calculated by adding individual quartile scores for each microbial antigen (gASCA, ALCA, ACCA, AMCA and Omp), ranging from 5 to 20. The distribution of quartile sums is shown.

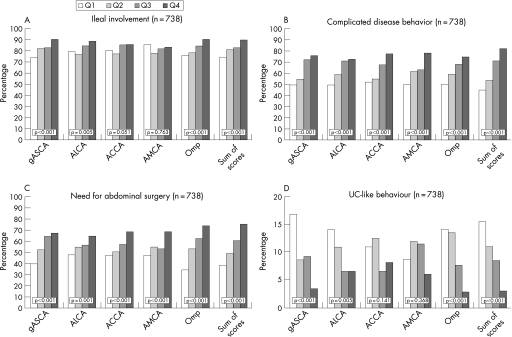

As shown in figure 4, we found an increasing percentage of complicated behaviour and a need for abdominal surgery as the level of response against any of the microbial antigens increased. Furthermore, we found an increasing percentage of Crohn's disease patients with ileal involvement and a decreased percentage of ulcerative colitis patients with an ulcerative colitis‐like behaviour as the level of the antibody response toward gASCA, ALCA and Omp increased.

Figure 4 (A) The percentage of ileal involvement in the function of level of antibody response. For the individual markers Q1, Q2, Q3 and Q4 consisted of respectively 184, 185, 185 and 184 Crohn's disease patients. For the sum of scores Q1, Q2, Q3 and Q4 consisted of respectively 161, 209, 201 and 167 Crohn's disease patients. (B) Percentage of complicated disease behaviour in function of level of antibody response. For the individual markers Q1, Q2, Q3 and Q4 consisted of respectively 184, 185, 185 and 184 Crohn's disease patients. For the sum of scores Q1, Q2, Q3 and Q4 consisted of respectively 161, 209, 201 and 167 Crohn's disease patients. (C) Percentage of need for abdominal surgery in function of level of antibody response. For the individual markers Q1, Q2, Q3 and Q4 consisted of respectively 184, 185, 185 and 184 Crohn's disease patients. For the sum of scores Q1, Q2, Q3 and Q4 consisted of respectively 161, 209, 201 and 167 Crohn's disease patients. (D) Percentage of ulcerative colitis‐like behaviour in function of level of antibody response. For the individual markers Q1, Q2, Q3 and Q4 consisted of respectively 184, 185, 185 and 184 Crohn's disease patients. For the sum of scores Q1, Q2, Q3 and Q4 consisted of respectively 161, 209, 201 and 167 Crohn's disease patients.

We studied the association between disease phenotypes and the level of antibody responses toward all five microbial antigens simultaneously. By adding individual quartile scores for each microbial antibody a quartile sum analysis was performed. Figure 3B shows the number of patients within each individual cumulative quartile sum (ranging from QS5 to QS20). We found an increasing likelihood of ileal disease (56% for QS5 to 92% for QS20), complicated behaviour (11–92%) and the need for abdominal surgery (22–75%), as well as a decreasing likelihood of an ulcerative colitis‐like behaviour (44–0%) in patients with increasing quartile sum scores (linear‐by‐linear association, all p < 0.001). As the relative small patient size of each possible quartile sum (n = 9–75), we also divided our patients into four relatively equal groups based on their quartile sum (quartile sum of scores: 161, 209, 201 and 167 Crohn's disease patients, respectively). As shown in figure 4, patients with an increased quartile sum of scores had significantly more ileal involvement (74.5% versus 81.3% versus 83.1% versus 89.8%, linear‐by‐linear association p < 0.001), complicated behaviour (44.7% versus 53.6% versus 71.1% versus 82.0%, p < 0.001) and the need for abdominal surgery (38.5% versus 48.8% versus 60.7% versus 74.5%, p < 0.001), and less ulcerative colitis‐like behaviour (15.5% versus 11.0% versus 8.5% versus 3.0%, p < 0.001).

The impact of disease duration on antibody response

In 373 Crohn's disease patients we had information regarding disease duration between the diagnosis of disease and serum sampling. Previous reports did not find a relationship between the duration of disease and serological responses against ASCA, pANCA, OmpC, I2 and CBir1.7,9,27 In this study cohort, however, patients who were positive for gASCA, ACCA, AMCA and Omp had significantly longer disease duration compared with patients who were negative for these serological markers. To study whether there was a correlation between the disease duration and the level of antibody response, we divided our 373 Crohn's disease patients into four relatively equal groups based on their disease duration. From these 373 Crohn's disease patients, 98, 103, 82 and 90 patients had a disease duration of, respectively, 3 years or less (Q1), 4–9 years (Q2), 10–15 years (Q3) and 16 years or longer (Q4). We found significant higher antibody responses against gASCA, AMCA and Omp with increasing disease duration (fig 5). We also found a trend for ACCA. The antibody response against ALCA was not influenced by disease duration.

Figure 5 Level of antibody response against (A) anti‐Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody (gASCA); (B) anti‐laminaribioside carbohydrate antibody (ALCA); (C) anti‐chitobioside carbohydrate antibody (ACCA); (D) anti‐mannobioside carbohydrate antibody (AMCA); and (E) outer membrane porin (Omp) in function of disease duration. Disease duration was divided into 0–3 years (Q1), 4–9 years (Q2), 10–15 years (Q3) and 16 years or longer (Q4).

Discussion

IBD, and especially Crohn's disease, is characterized by an aberrant recognition of luminal microbial antigens. An important mechanism underlying Crohn's disease pathogenesis is a so‐called loss of tolerance. In this study, we tested whether a new set of antibodies directed against anti‐glycans (gASCA, ALCA, ACCA and AMCA) and a more universal antibody against membrane porins (Omp) could help us in disease differentiation and stratification.

Differentiation between Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis

Several markers have been suggested to help in this differentiation, but up to now, only the combination of ASCA and pANCA seems to be accurate.5,13,28,29 The Crohn's disease‐associated pattern is ASCA+/pANCA−, whereas the ulcerative colitis‐associated pattern is ASCA−/pANCA+. The increased specificity of this combination (81 and 97%), however, is associated with a decreased sensitivity (30–64%). Moreover, in most of these patients the distinction between Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis can be made without the use of serological markers, based on the patient's history and physical examination, endoscopy, histology and radiology.

In 10% of patients with strictly colonic disease, however, histological features cannot be firmly assigned to Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis. These patients are than classified as indeterminate colitis or IBD type unclassified,23,30 which is frequently a temporary diagnosis. An early approximation of how the disease will progress could have important clinical implications (medical therapy, surgery, surgery outcome).

The new set of antibodies, tested in this study cohort, could not improve the differentiation between Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. gASCA, which has a good correlation with the more widely used ASCA (INOVA Diagnostics) as previously shown by Dotan et al.19 was the only accurate marker, with a sensitivity of 56.4%, a specificity of 90.4%, and a positive predictive value of 95.2%. Previous studies have shown that all commercially available ASCA performed well.31

The other markers (ALCA, ACCA, AMCA and Omp) were specific for Crohn's disease, but their sensitivity was poor (17.7–29.1%). The combination of gASCA, ALCA and pANCA only slightly improved the accuracy compared with the classic combination of gASCA and pANCA (AUC from 0.795 to 0.809 for the triple combination). Further prospective longitudinal studies in IBD patients with an initial diagnosis of IBD type unclassified are necessary to draw conclusions on the predictive role of these serological markers.

Differentiation between IBD and non‐IBD

We further tested whether this panel of serological markers could help in differentiating patients with IBD from patients with gastrointestinal inflammation and healthy controls. Again, in both situations gASCA had the best accuracy (AUC for IBD versus non‐IBD gastrointestinal inflammation 0.747; and AUC for IBD versus healthy controls 0.777). The classic combination of gASCA and pANCA improved the accuracy (AUC 0.785 and 0.813, respectively); however, the best accuracy was reached by a combination of gASCA, ALCA and pANCA (AUC 0.848 and 0.849, respectively). So, for the differentiation between IBD and other diseases with gastrointestinal complaints with or without inflammation, the combination of gASCA, ALCA and pANCA may help in the differentiation. Up to now, however, endoscopy with biopsies for histological examination remains the gold standard.

Disease stratification in Crohn's disease patients

After the initial observations with ASCA,16 several other markers (OmpC, anti‐I2 and anti‐CBir1) have been linked with a more severe disease behaviour in Crohn's disease patients, including the presence of fistula or strictures and the need for abdominal surgery.9,17,32,33 In the same way, we found a significant independent association between the presence of antibodies against gASCA, ACCA, AMCA and Omp and a complicated disease course (the presence of strictures or fistula) and the need for abdominal surgery. Furthermore, gASCA, ALCA and Omp were associated with ileal involvement. pANCA and Omp were, respectively, positively and negatively associated with an ulcerative colitis‐like disease behaviour. Previous papers had reported similar findings concerning the association with ileal involvement and an ulcerative colitis‐like disease behaviour.9,17,33

Patients with a higher number of antibodies and greater levels of antibody response had a greater frequency of ileal involvement, complicated behaviour and the need for abdominal surgery, and had a lower frequency of an ulcerative colitis‐like behaviour. Similar findings have been reported with other panels of serological markers, including ASCA, anti‐OmpC and anti‐I2 in one study17 and, gASCA, ALCA and ACCA in a second study.19

The observation that the level of antibody responses is associated with a more aggressive disease behaviour may have important clinical repercussions, because these patients will derive optimal benefit from a more aggressive therapy. To conclude on the predictive value of these markers, however, a condition sine qua non is that the antibody responses are stable over time, because it has clearly been demonstrated that a longer disease follow‐up will result in changes in the phenotypes of Crohn's disease patients.25,26

Up to now, nearly all studies reported stable antibody responses over time and after treatment with infliximab or surgery,7,9,27 and the serial measurement of pANCA and ASCA have been reported not to be useful.34 Recently, Israeli et al.35 showed that ASCA antibodies appear before the diagnosis of Crohn's disease and may predict the development of IBD. In a sub‐cohort of Crohn's disease patients, however, we found an increasing antibody response against gASCA, AMCA and Omp in patients with a longer disease duration (fig 5), which might explain the higher antibody responses in patients with complicated disease behaviour and the need for abdominal surgery. Similar findings, have previously been reported by Arnott et al.32 for both ASCA and Omp.

These observations highlight the importance of prospective longitudinal studies with serological markers. Up to now, only one small paediatric longitudinal study has reported a relationship between the presence and amount of antibodies at a time at which no fistula or strictures were clinically apparent and the development of a complicated disease behaviour during a median follow up of 18 months.33 The authors rightly noted that it remains unknown what proportion of the asymptomatic patients had already developed strictures or fistula before immune response testing, but went undetected in the absence of symptom‐driven diagnostic evaluation. We have initiated a prospective longitudinal study in our department to investigate this.

Conclusion

gASCA was the only accurate serological marker that allowed differentiation between Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis, with a significant improvement by combining responses against gASCA and pANCA. For differentiation between IBD, healthy controls and patients with non‐IBD gastrointestinal inflammation, gASCA was the most accurate marker, but the accuracy improved by combining responses against gASCA, ALCA and pANCA. In Crohn's disease patients, all of the serological markers studied (gASCA, ALCA, ACCA, AMCA and Omp) were associated with a more severe disease outcome (the presence of strictures or fistula and the need for abdominal surgery). Furthermore, Crohn's disease patients with a greater number of antibodies and higher levels of antibody responses had a greater frequency of ileal involvement, complicated behaviour and the need for abdominal surgery, and had a lower frequency of an ulcerative colitis‐like behaviour. To draw conclusions on the predictive role of these and other serological markers, prospective longitudinal studies are certainly necessary.

Competing interests: Declared (the declaration can be viewed on the Gut website at http://www.gutjnl.com/supplemental).

Copyright © 2007 BMJ Publishing Group & British Society of Gastroenterology

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Karolien Claes, Nele Van Schuerbeek, Tamara Coopmans and Els Houben for their enormous work in the laboratory. Marc Ferrante and Liesbet Henckaerts received a grant from the Flemisch Gastroenterology Association (VVGE). Séverine Vermeire, Gert Van Assche, Marie Pierik and Liesbet Henckaerts are supported by the Funds for Scientific Research (FWO), Belgium.

Abbreviations

ACCA - Anti‐chitobioside carbohydrate antibody

ALCA - anti‐laminaribioside carbohydrate antibody

AMCA - anti‐mannobioside carbohydrate antibody

AUC - area under the curve

gASCA - anti‐Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody

IBD - inflammatory bowel disease

Omp - outer membrane porin

pANCA - perinuclear anti‐neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody

ROC - receiver operating characteristic

Footnotes

Competing interests: Declared (the declaration can be viewed on the Gut website at http://www.gutjnl.com/supplemental).

References

- 1.Vermeire S, Rutgeerts P. Antibody responses in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 2004126601–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D'Haens G R, Geboes K, Peeters M.et al Early lesions of recurrent Crohn's disease caused by infusion of intestinal contents in excluded ileum. Gastroenterology 1998114262–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rutgeerts P, Goboes K, Peeters M.et al Effect of faecal stream diversion on recurrence of Crohn's disease in the neoterminal ileum. Lancet 1991338771–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seibold F, Weber P, Klein R.et al Clinical significance of antibodies against neutrophils in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gut 199233657–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quinton J F, Sendid B, Reumaux D.et al Anti‐Saccharomyces cerevisiae mannan antibodies combined with antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies in inflammatory bowel disease: prevalence and diagnostic role. Gut 199842788–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sendid B, Colombel J F, Jacquinot P M.et al Specific antibody response to oligomannosidic epitopes in Crohn's disease. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 19963219–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landers C J, Cohavy O, Misra R.et al Selected loss of tolerance evidenced by Crohn's disease‐associated immune responses to auto‐ and microbial antigens. Gastroenterology 2002123689–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sutton C L, Kim J, Yamane A.et al Identification of a novel bacterial sequence associated with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 200011923–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Targan S R, Landers C J, Yang H.et al Antibodies to CBir1 flagellin define a unique response that is associated independently with complicated Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 20051282020–2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hugot J P, Chamaillard M, Zouali H.et al Association of NOD2 leucine‐rich repeat variants with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature 2001411599–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franchimont D, Vermeire S, El Housni H.et al Deficient host‐bacteria interactions in inflammatory bowel disease? The toll‐like receptor (TLR)‐4 Asp299gly polymorphism is associated with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Gut 200453987–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Broberger O, Perlmann P. Autoantibodies in human ulcerative colitis. J Exp Med 1959110657–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peeters M, Joossens S, Vermeire S.et al Diagnostic value of anti‐Saccharomyces cerevisiae and antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies in inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 200196730–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruemmele F M, Targan S R, Levy G.et al Diagnostic accuracy of serological assays in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 1998115822–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joossens S, Reinisch W, Vermeire S.et al The value of serologic markers in indeterminate colitis: a prospective follow‐up study. Gastroenterology 20021221242–1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vasiliauskas E A, Kam L Y, Karp L C.et al Marker antibody expression stratifies Crohn's disease into immunologically homogeneous subgroups with distinct clinical characteristics. Gut 200047487–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mow W S, Vasiliauskas E A, Lin Y C.et al Association of antibody responses to microbial antigens and complications of small bowel Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 2004126414–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Altstock R T, Shtevi A, Karban A.et al Improved IBD diagnosis via ELISA detecting novel antibodies: anti‐chitobisoside carbohydrate antibodies (ACCA), anti‐laminaribioside carbohydrate antibodies (ALCA) and anti‐mannobioside carbohydrate antibodies (AMCA). Gastroenterology 2005128A303 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dotan I, Fishman S, Dgani Y.et al Antibodies against laminaribioside and chitobioside are novel serological markers in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 2006131366–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lennard‐Jones J E. Classification of inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl 19891702–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gasche C, Scholmerich J, Brynskov J.et al A simple classification of Crohn's disease: Report of the Working Party for the world congresses of gastroenterology, Vienna 1998. Inflamm Bowel Dis 200068–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vasiliauskas E A, Plevy S E, Landers C J.et al Perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in patients with Crohn's disease define a clinical subgroup. Gastroenterology 19961101810–1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silverberg M S, Satsangi J, Ahmad T.et al Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol 200519(Suppl A)5–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beaugerie L, Massot N, Carbonnel F.et al Impact of cessation of smoking on the course of ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2001962113–2116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cosnes J, Cattan S, Blain A.et al Long‐term evolution of disease behavior of Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 20028244–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Louis E, Collard A, Oger A F.et al Behaviour of Crohn's disease according to the Vienna classification: changing pattern over the course of the disease. Gut 200149777–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vermeire S, Peeters M, Vlietinck R.et al Anti‐Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA), phenotypes of IBD, and intestinal permeability: a study in IBD families. Inflamm Bowel Dis 200178–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koutroubakis I E, Petinaki E, Mouzas I A.et al Anti‐Saccharomyces cerevisiae mannan antibodies and antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies in Greek patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 200196449–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sandborn W J, Loftus E V, Jr, Colombel J F.et al Evaluation of serologic disease markers in a population‐based cohort of patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 20017192–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Price A B. Overlap in the spectrum of non‐specific inflammatory bowel disease – ‘colitis indeterminate'. J Clin Pathol 197831567–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vermeire S, Joossens S, Peeters M.et al Comparative study of ASCA (anti‐Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibody) assays in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2001120827–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arnott I D, Landers C J, Nimmo E J.et al Sero‐reactivity to microbial components in Crohn's disease is associated with disease severity and progression, but not NOD2/CARD15 genotype. Am J Gastroenterol 2004992376–2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dubinsky M C, Lin Y C, Dutridge D.et al Serum immune responses predict rapid disease progression among children with Crohn's disease: immune responses predict disease progression. Am J Gastroenterol 2006101360–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bossuyt X. Serologic markers in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Chem 200652171–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Israeli E, Grotto I, Gilburd B.et al Anti‐Saccharomyces cerevisiae and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies as predictors of inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2005541232–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]